Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a highly pathogenic facultative anaerobe that in some instances resides as an intracellular bacterium within macrophages and cancer cells. This pathogen can establish secondary infection foci, resulting in recurrent systemic infections that are difficult to treat using systemic antibiotics. Here, we use reconstructed apoptotic bodies (ReApoBds) derived from cancer cells as “nano decoys” to deliver vancomycin intracellularly to kill S. aureus by targeting inherent “eat me” signaling of ApoBds. We prepared ReApoBds from different cancer cells (SKBR3, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, and LN229) and used them for vancomycin delivery. Physicochemical characterization showed ReApoBds size ranges from 80 to 150 nm and vancomycin encapsulation efficiency of 60 ± 2.56%. We demonstrate that the loaded vancomycin was able to kill intracellular S. aureus efficiently in an in vitro model of S. aureus infected RAW-264.7 macrophage cells, and U87-MG (p53-wt) and LN229 (p53-mt) cancer cells, compared to free-vancomycin treatment (P < 0.001). The vancomycin loaded ReApoBds treatment in S. aureus infected macrophages showed a two-log-order higher CFU reduction than the free-vancomycin treatment group. In vivo studies revealed that ReApoBds can specifically target macrophages and cancer cells. Vancomycin loaded ReApoBds have the potential to kill intracellular S. aureus infection in vivo in macrophages and cancer cells.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, apoptotic bodies, vancomycin, bacterial therapy, antibiotics, macrophages, cancer cells

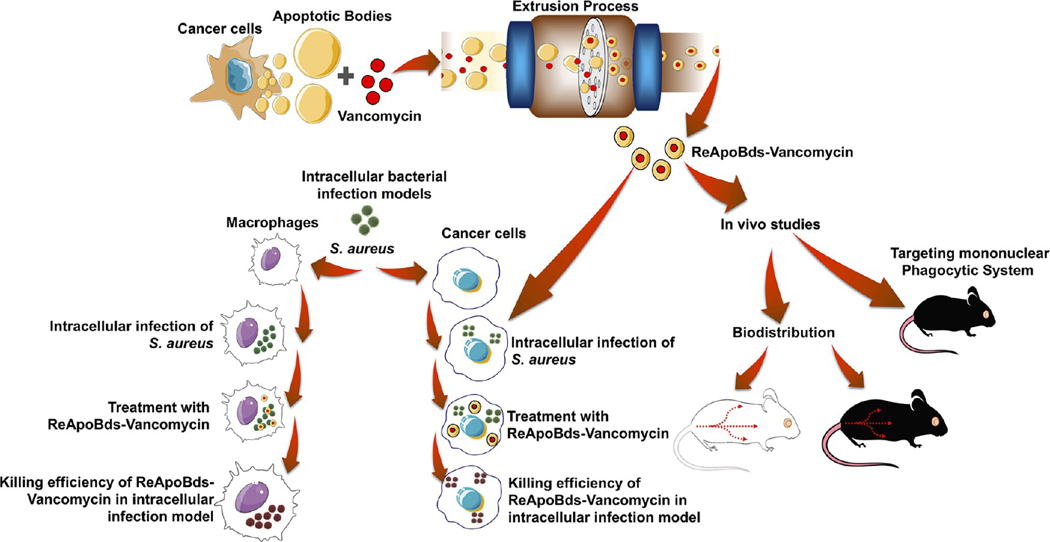

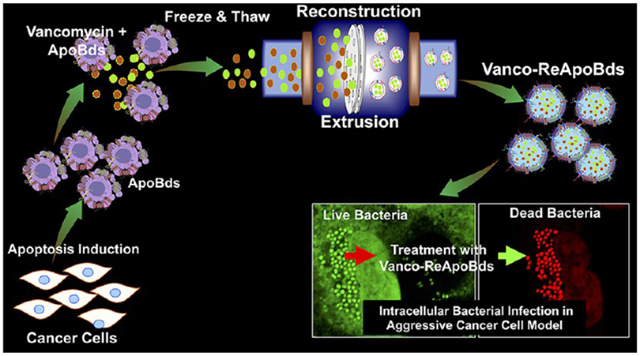

Graphical Abstract

As a facultative anaerobe, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is capable of creating an intracellular infection reservoir in several types of host cells, such as mast cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, epithelial cells, osteoblasts, and within aggressive cancer cells.1–4 These deposits of bacteria can then act as “Trojan horses” to establish secondary infection foci, resulting in recurrent systemic infections.5 S. aureus is also one of the major pathogens in community and hospital-acquired bloodstream infections that can survive and proliferate for several days after invading host cells.6 S. aureus infections can be severe and life-threatening, leading to abscesses, endocarditis, pneumonia, toxic shock syndrome, and sepsis.7 Infected macrophages and cancer cells play an important role in the initial stages of S. aureus infections and continue to do so throughout the course of infection in healthy individuals and cancer patients.8 In different host cells, S. aureus resorts to alternative strategies to survive phagocytosis and the antimicrobial mechanisms of host cells. In nonprofessional phagocytes, bacteria escape the endosome and follow this by cytoplasmic replication, or they replicate within autophagosomes.9 Professional phagocytes possess a limited capacity to kill S. aureus, and hence, the bacteria (that are well equipped with immune evasive mechanisms) replicate within the cells and eventually lyse the cells. Thus, a continuous cycle of phagocytosis, host cell death, and bacterial release is perpetuated.9

The distribution of macrophages within tissues defines the anatomical reservoirs of S. aureus, especially for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Infected macrophages first colonize the primary lymphoid organs, such as the liver and thymus, and then the secondary organs of the lymphatic system, such as the spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes, gut-and mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues, in addition to other major organs, such as the brain, lungs, and kidney.10 Surgical site MRSA infections significantly affect the management of patients with malignancy, and the percentage of S. aureus isolates among cancer patients broadly appear to be on the rise.11,12 Patients with aggressive cancers such as glioblastoma, triple negative breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma often undergo surgical procedures, blood transfusions, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and have indwelling catheters and drainage tubes, and are thus at greater risks of S. aureus infections.13 Post-operative antibiotic therapy is often problematic owing to intracellular bacterial invasion and/or antibiotic-resistance of bacterial strains.14 Taken together, macrophages and cancer cells are not only primary targets of MRSA infections in healthy individuals and cancer patients but also are an important source of bacterial persistence.15 Vancomycin is the preferable choice for treatment of MRSA and multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. However, vancomycin can have serious adverse effects including thrombophlebitis, kidney damage, epidermal necrolysis, and red man syndrome; possibly resulting in toxic symptoms that are worse than the infection.16 A promising approach to improve the efficacy of vancomycin treatment is to encapsulate it within nanocarriers to reduce systemic toxicity and promote longer activity. Targeting of vancomycin to individual infected cells would also allow the drug to reach intracellular bacteria, which otherwise would be sheltered from the antibiotic and could become a source for rekindlings of the infection. The combination of nanocarrier delivery and targeting to the site of infection provides a particularly powerful means of improving drug delivery.17

In recent years, biomimetic and bioengineering strategies have been employed to solve diverse biomedical challenges.18 Natural cell-derived vesicles (CDVs), such as extracellular vesicles, exosomes, and apoptotic bodies, have proven to be particularly effective for site-specific drug delivery while escaping from the immune system. Compared to synthetic liposomes, CDVs have major advantages that include their natural cell–cell communication, cell-specific recognition, tropism, response to biological signals, and immune evasion. Previously we demonstrated that tumor cell-derived extracellular vesicles (TEVs), and TEV-coated gold iron oxide nanoparticles (GIONs), act as natural tumor targeting nanocarriers for delivery of drugs and small RNAs.19 Here we investigate apoptotic bodies (ApoBds) as useful CDV-based nanocarriers for intracellular antibiotics delivery. ApoBds have a natural ability to access macrophages through natural immune recognition.20 Similarly, invasive cancer cells possess homotypic affinity toward TEVs when compared to conventional nanocarriers. ApoBds display distinctive “find me” and “eat me” signals, and cell membrane-associated adhesive protein signals in the form of “proteo-lipid vesicles”.21 Similarly, CDVs display cancer cell-specific adhesive proteins that play a crucial role in tumor microenvironment communications in vivo.18

It has been shown recently that CDVs derived from aggressive cancer cells can be used for targeted delivery of miRNA therapeutics and nanocontrast agents for imaging and therapy.18,19 Therefore, in this study, we use a “nano decoy” approach using reconstructed ApoBds (ReApoBds) loaded with vancomycin to facilitate access to macrophages and cancer cells infected with S. aureus. Our reconstruction process significantly reduces the size of ApoBds and enhances the encapsulation efficiency of vancomycin. In vitro cell culture studies show that vancomycin loaded ReApoBds efficiently kill intracellular bacteria in an in vitro model of S. aureus infected RAW 264.7 macrophages, as well as U87-MG and LN229 glioblastoma cells, compared to free, untargeted vancomycin treated cells. Additionally, our in vivo imaging and ex vivo analysis of indocyanine green (ICG) labeled and artificial miRNA-21 loaded ReApoBds biodistribution reveal time-dependent uptake of ReApoBds by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). Evaluation of splenic and abdominal macrophages shows efficient uptake of injected ReApoBds by these cells. Therefore, our reconstructed nanocarriers greatly increase targeting of macrophages in the liver and spleen as well as cancer cells infected with S. aureus, and this strategy can be adopted for treating cancer patients undergoing anticancer therapy to eliminate treatment-associated MRSA infection.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Production of Apoptotic Vesicles from Different Cancer Cells.

A schematic outline of the production of ReAPoBds and the overall experimental scheme are shown in Figure 1 and Figure S1. We cultured diverse cancer cells (human breast cancer cells: SKBR3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231; human glioblastoma cells: U87-MG and LN229; human hepatocellular carcinoma cells: HepG2; and the mouse breast cancer cells: 4T1) and then induced cellular apoptosis by simple serum starvation to produce cancer cell-specific apoptotic bodies. To verify the induction of cellular apoptosis by starvation, we initially stained the cells with Hoechst 33342 nuclear stain. Figure 2A shows Hoechst 33342 stained nuclei from U87-MG cells, with and without starvation. The nuclei of healthy cells were mostly spherical and evenly stained owing to the uniform distribution of DNA. By contrast, apoptotic nuclei were fragmented and stained intensely owing to the condensation and easy permeability of cell membranes to the DNA staining dye (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration outlines the experimental design. Cancer cells were cultured and induced to undergo the apoptosis process. The apoptotic vesicles were collected and used to produce antibiotic-loaded reconstructed apoptotic bodies, and the resultant ReApoBds were tested for efficacy in an in vitro model of intracellular S. aureus infection within macrophages and cancer cells. Finally, we investigated the biodistribution and organ-specific accumulation in healthy mouse models.

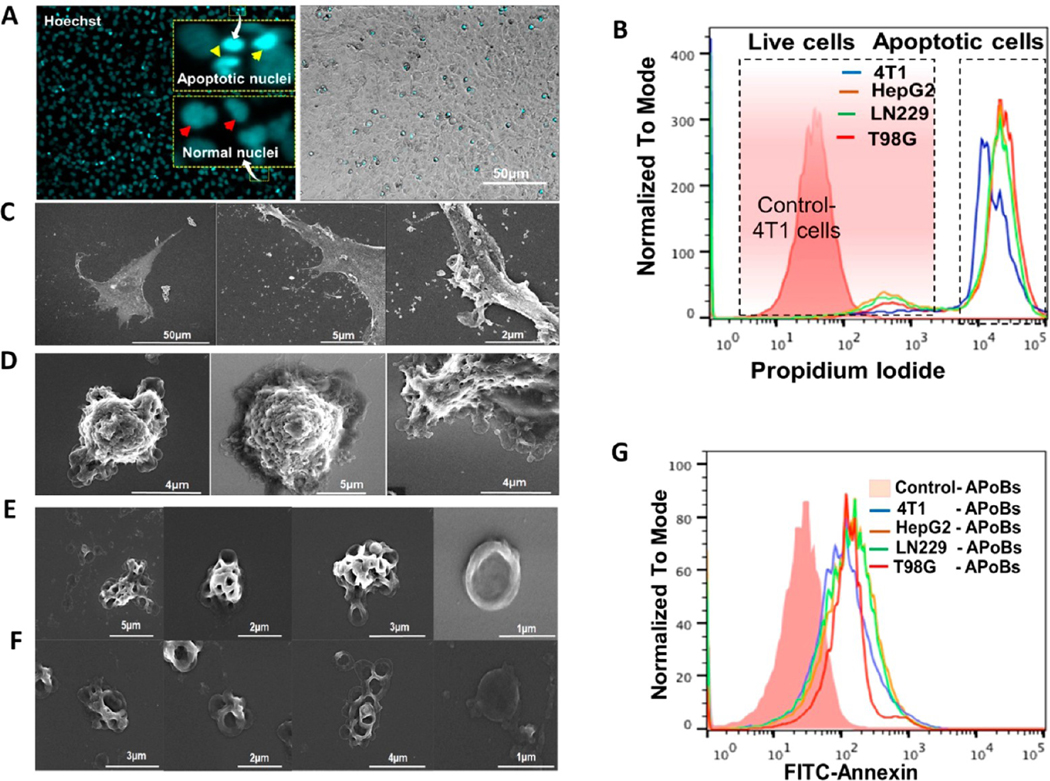

Figure 2.

Production of apoptotic vesicles from different cancer cells. (A) Production of apoptotic bodies. U87-MG cancer cells were induced to undergo apoptosis and then stained with Hoechst 33342 to visualize the DNA condensation and fragmentation. The nuclei of control cells were mostly spherical and evenly stained owing to the uniform distribution of DNA (arrows point to the uniform distribution of DNA). In apoptotic cells, the nuclei were fragmented and intensely stained (white arrows point to the condensation of the DNA). (B) Flow cytometry analysis of cancer cell apoptosis owing to starvation. Flow cytometric evaluation for the quantification of apoptotic cancer cell population in tested cancer cells (serum deprived cells: 4T1, HEPG2, LN229, and T98G) compared with the serum supplemented cells. (C, D) The human glioblastoma cells (U87-MG) with serum (control) and without serum (apoptotic cells) were imaged under a scanning electron microscope. Control cell images show the firmly adherent and the biogenesis of microvesicles (MVs) and exosomes (Exo). Apoptotic cells show significant morphological changes such as cell shrinkage, aggregation, and abundant formation of plasma membrane blebbing. (E, F) Scanning electron microscopy images of apoptotic bodies isolated from human glioblastoma cells (U87-MG). (G) Flow cytometry analysis of cancer cell-derived ApoBds shows that the vesicles collected from serum deprived cells show higher amounts of PtdSer display, compared to the vesicles collected from the serum supplemented cells. Apoptotic bodies stained for PS detection: The cells were labeled with FITC-annexin V (2.5 pg/mL).

To verify this further, we performed propidium iodide (PI) dye-based flow cytometric analysis of cancer cells (4T1, HepG2, LN229, and T98G) to confirm apoptotic induction after serum starvation. This revealed an increase in the apoptotic cancer cell population in the tested serum deprived cancer cells when compared to serum supplemented cells (Figure 2B). The process of apoptosis and the generation of ApoBds were further visualized using U87-MG cells and field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEMs from ZEISS SIGMA). Normal U87-MG cells released diverse membrane-bound vesicles (microvesicles, exosomes, and apoptotic bodies), as shown in Figure 2C, where the cells are firmly adherent. Furthermore, Figure 2C shows the abundant micron-sized microvesicles attached to the plasma membrane and nanosized exosome-like vesicles (secreted) by the U87-MG cells under normal growth conditions. This indicated that these vesicles originated by an outward budding as the plasma membrane vesicles (MVs) or within the endosomal system as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) and were then secreted during the fusion of multivesicular endosomes (MVEs) with the cell surface (to form exosomes).

By contrast, induction of starvation resulted in a series of morphological changes that included cell shrinkage, plasma membrane blebbing owing to the cytoskeleton (actomyosin) contraction, and subsequent separation of plasma membrane blebs to generate different sizes of U87-MG-derived ApoBds, as shown in Figures 2C–F, S3, and S4. Furthermore, SEM images of Figure 2C–F and Figures S3–S5 also show the morphological changes of apoptotic cell disassembly and ApoBds formation, which can be defined as the sequential morphological changes in the apoptotic cells. The initial step was formation of balloon-like structures called apoptotic membrane blebs, followed by the formation of microtubule spikes and apoptopodia (Figure S3). At later stages of cell death, the apoptotic cell membrane protrusions underwent fragmentation to generate ApoBds in U87-MG cells (Figures S4 and S5).

Interestingly, compared to the vesicles generated from normal cells (Figure 2C), apoptotic U87-MG cells produced diverse populations of vesicles ranging in size from 0.5 μm to larger than 10 μm (Figures 2D–F and S3–S5). Additionally, the loss of phospholipid symmetry in the plasma membranes of dying cells and the translocation of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) from the inner membrane to the outer leaflet of the lipid bilayer is a distinctive marker for the identification of vesicles generated from dying cells. Therefore, we investigated the PtdSer display on the ApoBds collected from the representative cancer cells (4T1, HepG2, LN229, TG98) using flow cytometry and Annexin-V staining. Figure 2G shows these results of ApoBds isolated from serum starved cells. We observed high quantities of PtdSer displayed by the vesicles collected from serum starved cells compared to the control cells. These findings concur with other reports, since the formation of ApoBds is a late process during the progression of apoptosis and occurs at a stage in which PtdSer is already exposed on the dying cells via the activation of scramblase Xkr8 and inhibition of flippases ATP11A and ATP11C.20,22

Preparation of Cancer Cell-Derived Reconstructed ApoBds (ReApoBds) Loaded with Vancomycin.

The fragmented ApoBds from different cancer cells (SKBR3, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, and LN229) were collected and purified as shown in Figure S6. Then, we used the purified ApoBds for the reconstruction and vancomycin-loading process, as shown in the flow diagram in Figure S7. Initially, the collected ApoBds were sonicated into small pieces in the presence of vancomycin, followed by a freeze and thaw process. The apoptotic proteolipid vesicles suspension was then passed sequentially through polycarbonate filters of decreasing pore sizes (0.4 to 0.2 μm). As expected, the reconstruction process significantly reduced the size of apoptotic proteolipid vesicles from the initial size of 1–10 μm down to 100–150 nm and also reassembled them as nanovesicles (NVs) (Figure 3A). In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of ReApoBds prepared from representative cancer cells (SKBR3, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, and LN229) showed that the produced NVs were in the nanometer size range (100–150 nm) with well-defined spherical shapes (Figure 3B). Furthermore, our reconstruction process yielded well size-controlled and relatively homogeneous vesicle formation (Figure 3B) when compared to natural vesicles released by apoptotic cells (Figure 2E).

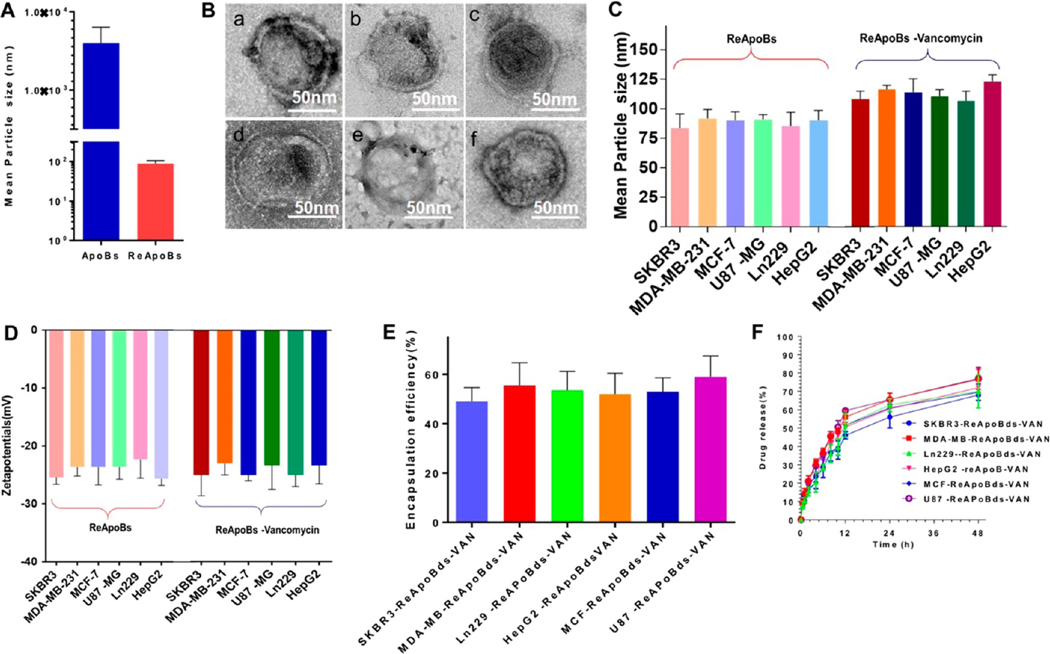

Figure 3.

Reconstruction and characterization of ApoBds. (A). DLS analysis of apoptotic bodies and Reconstructed ApoBds measured for size. (B) Transmission electron micrograph shows the ReApoBds. The fragmented ApoBds were collected from different cancer cells (human breast cancer cells (SKBR3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231), the human glioblastoma cells (U87-MG and LN229), and the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HepG2) culture media and used for the reconstruction process to generate ReApoBds. Negative-stain electron microscopy was performed to visualize the ReApoBds. Scale bars, 50 nm. (C and D) DLS analysis was performed to determine the size and surface charge of ReApoBds loaded with or without vancomycin. Quantification of (E) encapsulation efficiency and (F) release profile of vancomycin from ReApoBds. The vancomycin from ReApoBds was determined by a RP-HPLC method using an UltiMate 3000 HPLC system with variable wavelength detector.

We analyzed these using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and nanoparticle tracking analysis. Figure 3C and Table S1 show the size, charge, PDI, and concentration of ReApoBds produced from different cancer cells. Overall, the reconstructed NVs characterization indicated that the ReApoBds exhibited narrow size distributions, with a size range of 80–150 nm (Figure S8) and an average negative ζ potential of −20 to −28 mV (Figure 3D). Earlier investigations had shown that the entrapment of water-soluble drugs into the hydrophilic lipid core was low, as is the case for antibiotics.23 Interestingly, our method yielded the highest amount of vancomycin encapsulation (40% to 60% overall) when compared to other methods, and this high amount of encapsulation only slightly impacted the physiochemical characteristics of ReApoBds (Figure 3C–E). Previously, it had been shown that RBC-derived cellular vesicles exhibit enhanced vancomycin loading when the membrane was combined with cholesterol.24 Since cancer cell membranes possess a very high cholesterol content compared to normal cells,25 we speculate that the enhanced loading efficiency we observed in this study using the cancer cell-derived ApoBds could be due to the benefit of cholesterol molecules present on the membranes, although this requires further verification. After the preparation of optimal vancomycin loaded ReApoBds, we tested them for vancomycin release profiles and found that an initial burst release occurred within the first 2 h, and then a sustained vancomycin release profile was observed thereafter for more than 48 h (Figure 3F). Overall, our reconstruction method and the results we obtained demonstrated that ReApoBds permit a flexible allowance for variations in size, charge, and loading of high amounts of vancomycin. In addition, our approach was able to promote the production of nanosized apoptotic cell-like vesicles that mimic the apoptotic signaling of proteolipids.

Proteomic Profiling of ReApoBds.

We performed proteomic analysis of ApoBds to identify proteins that play important roles in the biofunctions of these vesicles in activating “eat me” signaling to deliver the loaded vancomycin to macrophages and cancer cells. We identified 1783 and 1911 distinctive proteins from ApoBds derived from SKBR3 and 4T1 cells, respectively. The absolute intensity of extracellular particle proteins spanned 6 orders of magnitude (Figure 4A). Among the identified proteins, 56 were found to be in the COSMIC Cancer Gene Census, with pivotal roles in cancer. 78% of the identified proteins were present in Vesiclepedia (http://microvesicles.org), and some of them were proteins that are commonly annotated as exosome markers, including, in order of absolute abundance: ACTG1, ENO1, GAPDH, HSPA8, YWHAE, ALDOA, LDHA, YWHAZ, CFL1, HSP90AA1, PGK1, ANXA5, EEF2, EEF1A1, HSP90AB1, ANXA2, MSN, SDCBP, and PDCD6IP, corresponding to 19 out of 25 exosome markers. Full proteomic identification data are provided in Table S2. All proteins identified in SKBR3-ApoBds and 4T1-EVs were subjected to gene enrichment analysis against the whole human and mouse proteome database, respectively, and enriched categories were identified by GO cellular component, GO biological process, GO molecular function, and protein domain. Figure 4B shows enriched categories containing more than four proteins, and adjusted p-value (Bonferroni correction) <0.01 (data represent the annotation of the functional enrichment of specific proteins, and the data are presented as the −log10 (adj. p-value) with a higher value representing greater functional enrichment of a category).

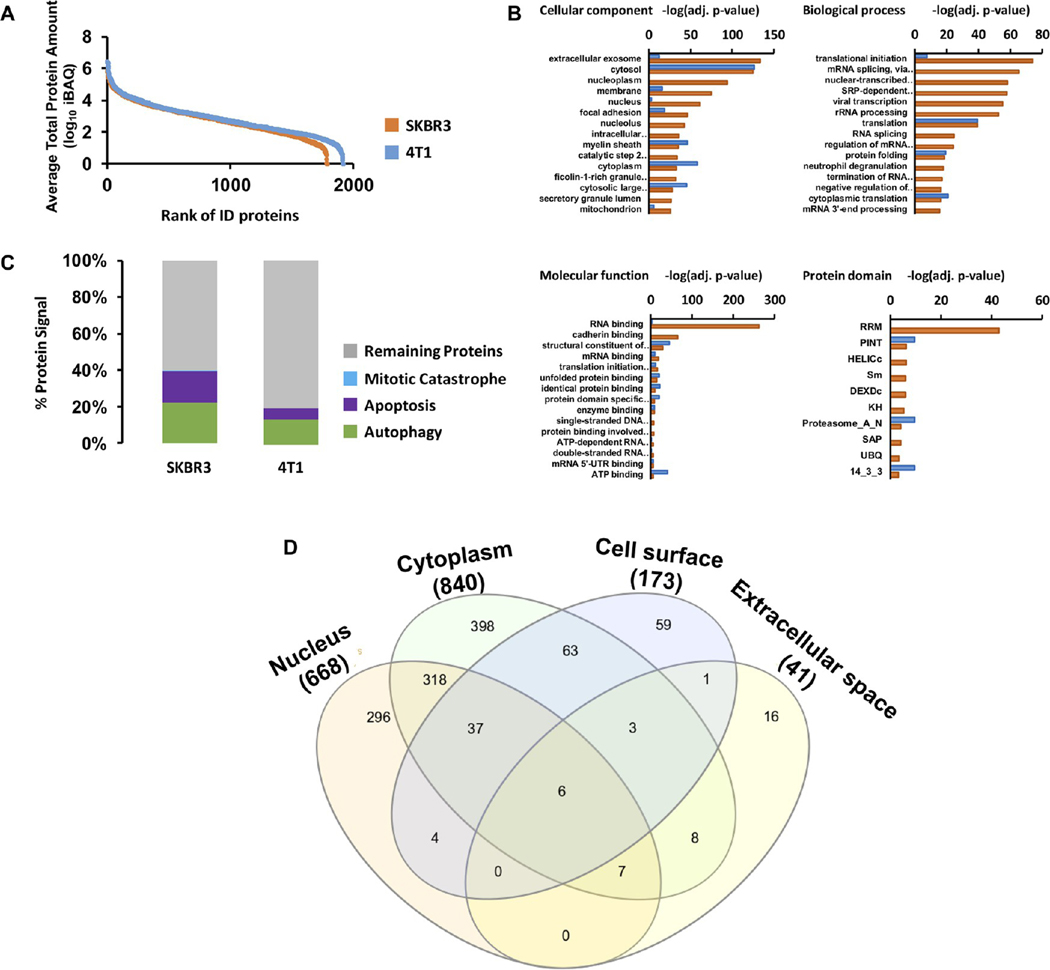

Figure 4.

Proteomic analysis of ApoBds. Proteomic analysis of apoptotic vesicles and macrovesicles derived from SKBR3-ApoBds. (A) Dynamic range of LC-MS/MS analysis of proteins identified in SKBR3-ApoBds (orange) and 4T1-EVs (blue). Ranking of proteins according to the average of their absolute amounts. Quantification was based on added peptides intensities extracted from the MS1 of the identified proteins. (B) Identified proteins from each sample were subjected to gene enrichment in by GO cellular component, GO biological process, molecular function, and protein domain. Protein enrichment is represented as −log10 of p-value after Bonferroni correction. (C) Percentage of absolute protein amount measured as the sum of iBAQ intensities of proteins related with apoptotic process according to Cancer Proteomics Database. (D) Venn diagram showing the cellular location of identified proteins.

Clear differences were observed between proteins identified in SKBR3-ApoBds versus 4T1-EVs. In the cellular component analysis, SKBR3-ApoBds proteins demonstrated strong enrichment in those proteins described as extracellular exosome proteins identified in SKBR3-ApoBds as well as proteins annotated to be in the nucleus, nucleoplasm, or nucleolus, and proteins related with focal adhesion, while proteins identified in 4T1-EVs were more enriched in the cytosolic (cytosol and cytoplasm) category. By molecular function, several categories were enriched in both sample types, however, RNA binding and cadherin binding proteins were more significantly enriched in SKBR3-ApoBds. Related differences were also observed in biological processes and protein domains in SKBR3-ApoBds, and where biological differences were mainly concentrated in RNA binding, splicing and processing, and proteins relevant to ApoBds and their target cells (i.e., cadherin binding and focal adhesion). Finally, we performed an additional analysis to understand the biological differences between SKBR3-ApoBds and 4T1-EVs regarding the apoptosis process. The percentage of total signal in the proteomics experiments from apoptosis, autophagy, and mitotic catastrophe-related proteins according to the Cancer Proteomics Database in SKBR3-ApoBds was twice as intense as the signal for the same types of proteins in 4T1-EVs (Figure 4C,D). From both sample types, some important apoptosis effector proteins were identified including CYCS, ANP32A, DIABLO, CSE1L, FADD, CASP3, and TNFRSF10B (Table S2).

In vitro Cell Uptake Studies of ReApoBds in 2D and 3D Culture Models.

We investigated the in vitro cell uptake efficiency of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds labeled with ICG in two-dimensional (2D) in Raw-264.7 macrophages and U87-MG and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines (as model 2D cell lines). The fluorescence microscope images of Raw-264.7 cell uptake efficiency of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG are shown in Figure S9. After incubation with ReApoBds-ICG, we observed a strong intracellular ICG fluorescence signal in the phagosome of the cells. Furthermore, IVIS fluorescence imaging analysis further confirmed the time and concentration-dependent ICG fluorescence signal increasing over time (Figure S9). A similar pattern of ReApoBds-ICG uptake was observed with MDA-MB-231 (Figure S10) and U87-MG (Figure S11) cells, indicating that ReApoBds mimic the source of cell-derived ApoBds. We also performed a similar uptake study in three-dimensional (3D) cancer cell culture models, such as cancer spheroids (CSs), considered as promising in vitro models that replicate the main features of human tumors.26 We investigated the in vitro cell uptake efficiency of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG in 3D CSs in SKBR3, 4T1, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, GL26, and patient-derived glioma CSs (GBM2, GBM39). The Celigo cell cytometer images showed the uptake efficiency of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG in 3D CSs of SKBR3, 4T1, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, GL26, and patient-derived glioma CSs (GBM2, GBM39) after 48 h of treatment with SKBR3-ReApoBds-ICG (Figures S12 and S13). We found a strong ICG fluorescence signal in the entire CSs. Recently a study by our research group, and others, has demonstrated that cancer cell-derived EVs and apoEVs can efficiently recognize the same and other cancer cells owing to cancer cell adhesion molecules. The present experimental results further confirm the cancer cell-specific recognition and rapid uptake of ReApoBds as they mimic the surface proteomics of cancer cell-derived apoptotic vesicles.19,27,28

Intracellular Antibacterial Activity.

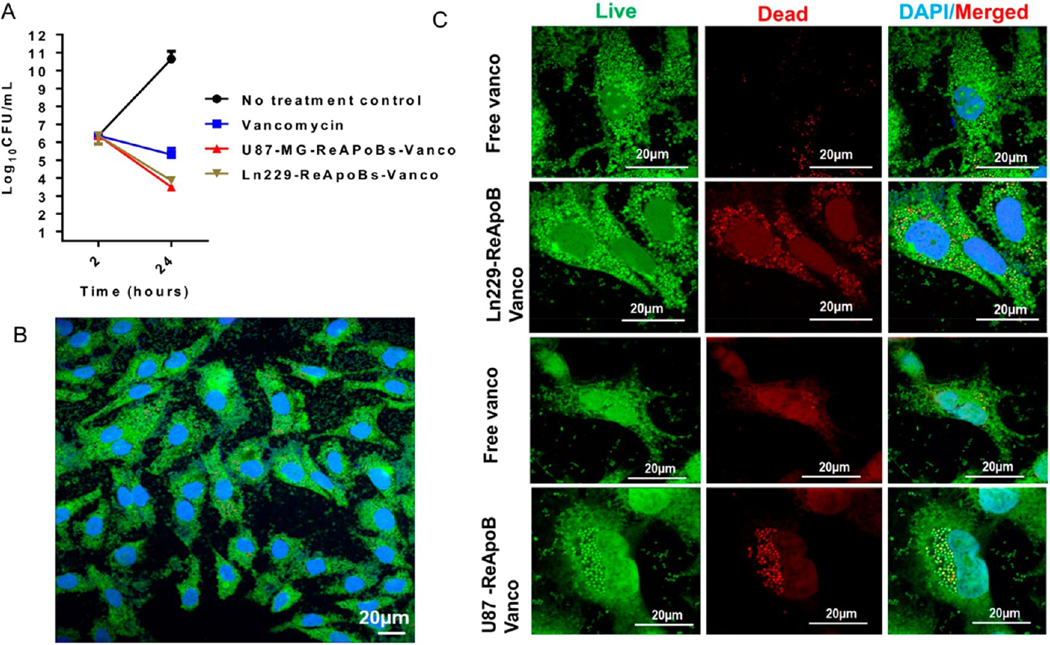

We further tested the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of free vancomycin and ReApoBd-vancomycin against the MRSA strain. We found the MIC of free vancomycin was 1–2 μg/mL against the MRSA-MW2 strain (Figure S14). However, the poor penetration of free vancomycin into mammalian cells renders the antibiotic less efficient in clearing intracellular S. aureus.29 Hence, we hypothesized that ReApoBds, with their natural propensity for increased cellular uptake especially by macrophages and cancer cells, might be efficient NVs to deliver vancomycin inside bacterial infected mammalian cells. To test this hypothesis and to assess the efficiency of vancomycin loaded ReApoBds, we administered different doses of up to 8-fold the MIC to RAW 264.7 mouse macrophages infected with MRSA-MW2 (Figures S14 and S15). Therapeutic efficiency of ReApoBds was evaluated initially by the broth microdilution method. The MIC was determined as 1–2 μg/mL. S. aureus is a facultative anaerobe and can invade and survive inside mammalian macrophages, and free vancomycin is known to have poor intracellular entry.29 We observed that ReApoBds delivered vancomycin efficiently into the macrophages and cleared the intracellular bacteria. The vancomycin delivered using ReApoBds killed 2 − log10 CFU of intracellular MRSA-MW2 efficiently (p < 0.001) from an initial inoculum, compared to free vancomycin that killed 1 − log10 CFU of intracellular MRSA-MW2 (Figure 5A). Untreated cells infected with MRSA-MW2 escaped from the phagocytosis-mediated killing and survived inside the macrophages. The survival was measured as a 4 − log10 CFU increase from an initial inoculum (Figure 5A). We found that ReApoBds-vancomycin cleared the intracellular MRSA-MW2 more effectively than the free-vancomycin treatment.

Figure 5.

Intracellular bacterial killing assays in macrophages. (A) Quantitative graph showing the efficiency of intracellular S. aureus killing efficiency by ReApoBd-vancomycin from different cancer cells compared to free vancomycin in RAW264.7 macrophage cells. (B) Confocal microscopic images of mouse macrophage cell lines (RAW 264.7 cells) were infected with MRSA-MW2 and allowed the S. aureus bacterium to replicate intracellularly and stained with live/dead cell staining kit. (C) Similarly, to visualize the intracellular killing efficiency, ReApoBds-vancomycin live/dead cell staining experiments were carried out using a kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in intact cells by confocal microscopic imaging.

We previously reported that EVs derived from cancer cells homotypically and efficiently target cancers of the same type.19 Hence, we hypothesized that ReApoBd-vancomycin derived from cancer cells could appropriately target cancer cells infected with MRSA. We tested ReApoBd-vancomycin in cancer cell lines (U87-MG and LN229) to evaluate the efficacy of ReApoBd-vancomycin in killing the S. aureus bacteria inside the cancer cells, during an infection process. To test this hypothesis, we administrated ReApoBd-vancomycin at different concentrations (up to a maximum of 8-fold the MIC) to the glioblastoma cell lines U87-MG and LN229 that were previously infected with MRSA-MW2 bacterial strain. After 24 h of an infection (2 h infection, plus 2 h gentamicin treatment, plus 20 h ReApoBd-vancomycin administration), intracellular bacterial killing efficacy of ReApoBd-vancomycin was evaluated. We observed that ReApoBd-vancomycin administration reduced a 2 − log10 CFU from an initial inoculum, and the reduction was statistically highly significant (p > 0.001) when compared to the free vancomycin and negative controls. On the other hand, the free vancomycin exhibited poor intracellular entry and cleared the 1 − log10 CFU of invaded MRSA-MW2. To verify this observation, live/dead bacterial staining was performed. The assay demonstrated that the live bacterial cells inside the mammalian cells were stained green (live bacterial cell) or red (dead bacterial cell). After treatment, as demonstrated in the previous assay, we fixed the cells on a coverslip and viewed them under a confocal microscopy. MRSA-MW2 bacterial cells invaded aggressive glioblastoma cells (U87-MG and LN229) (Figures S16 and S17). The untreated infection group contained ingested (Figure 5) and invaded bacterial cells (Figure 6) that stained positive with live cell green dye and the vancomycin treated infection group stained with partially red and green, demonstrating the presence of a mixture of live and dead bacterial cells inside the macrophages (Figure 5) and cancer cells (Figures 6, S18, and S19). However, the ReApoBds-vancomycin treatment group showed that most of the ingested bacterial cells in macrophages (Figure 5) or invaded cells in cancer cells (Figure 6) were stained red, confirming that the ReApoBds-vancomycin treatment group killed the MRSA-MW2 bacterial cells more efficiently than free vancomycin (Video S1 and S2).

Figure 6.

Intracellular bacterial killing assays in aggressive glioblastoma cancer cell lines. (A and B) Quantitative graph showing the relative MIC evaluated in U87-MG and LN229 cells with free vancomycin or ReApoBds loaded vancomycin. Aggressive GBM cell lines (U87-MG and LN229) were infected with MRSA-MW2, and the S. aureus bacterium allowed to replicate intracellularly. Thereafter, the infected macrophages were treated with either free vancomycin or ReApoBds-vancomycin prepared from different cancer cells. To assess the intracellular killing efficiency, the infected GBM cells were lysed to release intracellular bacteria, the cell lysates were diluted serially, and CFUs were enumerated by plating on TSA plates (A) and in intact cells by fluorescence microscopic imaging (B). (C) Similarly, to visualize the intracellular killing efficiency ReApoBds-vancomycin live/dead cell staining experiments were carried out using a kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in intact cells by confocal microscopic imaging.

Super-resolution fluorescence microscopy combines the ability to observe biological processes beyond the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy (200 nm) with all the advantages of the fluorescence readout, such as labeling specificity and non-invasive live-cell imaging.30 We aimed to visualize the intracellular killing efficiency of ReApoBds-vancomycin treatment using the SP8 Lightening super-resolution microscopy. This feature allowed us to obtain fast acquisition with simultaneous multicolor imaging in super-resolution down to 200 nm. The representative Z-stack images (Figure S20 and Video S1 and S2) clearly showed the MRSA-MW2 internalized into the phagosome compartment of macrophages, and treatment with ReApoBds-vancomycin killed most of intracellular MRSA-MW2 (S. aureus) within the macrophages (stained red). We also pursued another approach using ultra-resolution confocal image analysis with custom MATLAB software (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA), for the visualization of early subcellular localization of bacteria. The analysis of representative high-resolution images showed that the location of S. aureus was confined to the phagosomal compartment and bacteria replicated in the acidic compartment of the free vancomycin treated cell group (Figure S21 and Video S1 and S2). Interestingly, ReApoBds-vancomycin treatment efficiently kills (red) most of the S. aureus in the phagosomal compartment.

In Vivo Biodistribution in Immunodeficient and Immunocompetent Mouse Models.

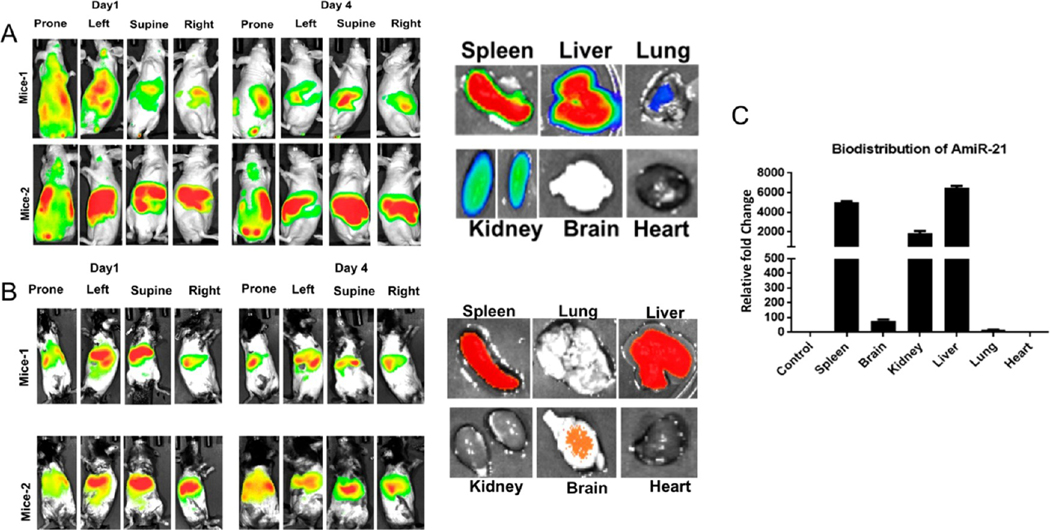

To test the in vivo biodistribution and to assess the organ-specific accumulation of ReApoBds, we used healthy immunodeficient nude (nu/nu) and immunocompetent C57BL/6 mouse models. We used ICG labeled ReApoBds (Figure S22) for the biodistribution study since it can be used for in vivo fluorescence (FLI) and photoacoustic (PAI) imaging. We administered 150 μg protein equivalent of ICG labeled ReApoBds intravenously to mice. Sensitive NIR fluorescence imaging was used to access the biodistribution and organ-specific accumulation of ReApoBds-ICG at different time points after initial injection. Figure S23 shows the BioD of free ICG solution in immunocompetent mice. As expected, the free ICG showed a strong intense ICG fluorescence signal distribution in the entire animal at 1 h post-injection. After 24 h of injection, the free ICG fluorescence signal intensity was significantly reduced owing to the rapid clearance of ICG from the circulation system. In contrast, the ReApoBds-ICG showed a different biodistribution pattern with RES-specific accumulation in both nude and immunocompetent mice models. The signal from the single dose can be present in the animals for more than 4 days, with a high accumulation in the liver and spleen (Figure 7). This observation was further confirmed with photoacoustic imaging. As shown in Figure S24, the biodistribution data indicated that the ReApoBds-ICG were mainly distributed in the spleen and liver. This is because the apoptotic vesicles mimicking properties of ReApoBds-ICG are mostly taken by the mononuclear phagocytic system. Furthermore, ex vivo fluorescent imaging confirmed the ReApoBds-ICG were significantly distributed to the liver and spleen (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Biodistribution of ReApoBds in nude and immunogenic mice. Nude mice (nu/nu) and C57BL/6J healthy mice were used to investigate the biodistribution of ReApoBds. The ReAPoBs were labeled with ICG using a conjugation process. Each mouse was injected with 150 μL of ReApoBds ICG (5 × 1011 particles) on day 0 and imaged on days 1 and 4, using a Lago (Spectral Imaging system) for fluorescence. (A) The ReApoBds-ICG injected nude animals were sacrificed on day 5, and the organs (liver, spleen, kidney, heart, lungs, and brain) were collected for ex vivo analysis. (B) The C57BL/6J healthy mice were injected with 150 μL of ReApoBds-ICG (5 × 1011 particles) on day 0 and imaged on days 1 and 4, using a Lago (Spectral Imaging system) for fluorescence. The ReApoBds-ICG C57BL/6J animals were sacrificed on day 5, and the organs (liver, spleen, kidney, heart, lungs, and brain) were collected for ex vivo analysis. (C) The biodistribution of Antisense-miR-21 in ReApoBds-Antisense-miR-21 injected C57BL/6J mice organs. The Taqman real-time qRT-PCR was used for the organ-specific biodistribution based on the quantification of Antisense miR-21.

Biodistribution of Model Therapeutic miRNAs Loaded ReApoBds for Absolute Quantification by qRT-PCR.

We, and others, have previously reported on the method of therapeutic miRNA loading and delivery via tumor cell-derived vesicles and demonstrated that the loaded miRNA can be used to monitor the biodistribution of TEVs in animal models. Interestingly, ApoBds, as oncogenic miRNA carriers, may be involved in cancer cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis.27,31 Therefore, we aimed to show that therapeutic miRNAs can be loaded into ApoBds and can be used to monitor the biodistribution in animal models. To validate the efficiency of packaging of Cy5-AntimiRNA-21 into SKBR3 cancer cell-derived ReApoBds, we performed fluorescence microscopy analysis. Figure S25 shows that transient transfection of Cy5-AntimiRNA-21 into donor SKBR3 cells led to the endogenous packing of Cy5-AntimiRNA-21 into the releasing ApoBds. To investigate the cellular uptake and release of intracellular Cy5-AntimiRNA-21, we treated recipient SKBR3 cells with donor cells-derived ReApoBds-Cy5-AntimiRNA-21. Shortly after incubation with ReApoBds-Cy5-AntimiRNA-21, we observed a punctuated pattern of intracellular fluorescence as shown in Figure S25. To investigate the biodistribution in mouse models, the ICG labeled ReApoBds-AntimiRNA-21 were injected into the mice via tail vein. Figure 7 shows the qRT-PCR results for the biodistribution of model therapeutic AmiRNA-21 loaded SKBR3-ReApoBds-ICG in healthy mice. The results matched those obtained using our IVIS-based fluorescence imaging, as the miRNA mainly accumulated in liver, spleen, and kidney. These observations clearly indicate that ReApoBds were mostly taken up by the immune cells and macrophages in the RES.

Toxicity Evaluation by Histological Analysis.

We also examined the toxicity associated with ReApoBds treatment in C57BL/6 immunocompetent mouse models. Microscopic examination of the lung, liver, spleen, and kidney tissue sections in the control group showed normal histological structures, while mice administered with three consecutive doses of SKBR3-ReApoBds revealed a moderate pathological alteration (Figure S26). However, we did not observe any significant weight loss or adverse physical signs or morphological changes in the animals receiving ReApoBds. Future development of CDVs as therapeutics delivery systems will require in depth understanding of their general safety and toxicity profiles, particularly if CDVs are derived from allogeneic or even xenogeneic sources. Our in vivo data are also consistent with previous reports, indicating moderate toxicity of ReApoBds following in vivo administration.32

Targeting Splenic and Peritoneal Macrophages Using ReApoBds.

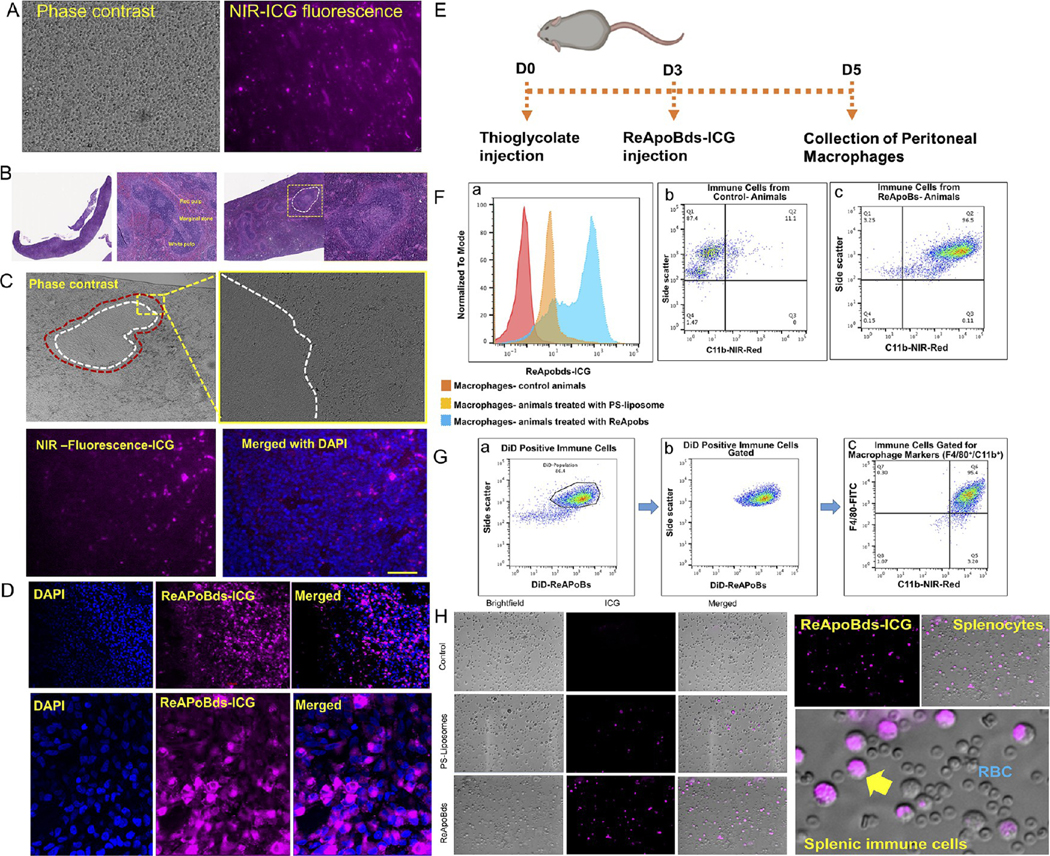

S. aureus bacteria that gain access to the circulation are removed from the bloodstream by the intravascular macrophages of the liver (the Kupffer cells). After the liver, the spleen is the major filter for blood-borne pathogens, antigens, and apoptotic bodies. Additionally, recent findings have highlighted that splenic macrophages serve as a reservoir for septicemia caused by intracellular S. pneumoniae,33 and targeting of splenic macrophages could provide opportunities for development of different treatments. Therefore, we performed an additional investigation on spleen-specific accumulation of ReApoBds. Initially, we performed fluorescence microscopy analysis of splenocytes extracted from ReApoBds-ICG injected mice. Figure 8A shows the fluorescence microscopy images of whole splenocytes extracted from ReApoBds-ICG injected animals. We observed strong ICG fluorescence signals from the extracted splenocytes, which indicated that ReApoBds strongly accumulated in the mice spleens. In addition, we performed histology analysis of spleens collected from ReApoBds-ICG injected mice. The spleen combines the innate and adaptive immune system in an exceptionally organized way. The structure of the spleen shows the compartmental regions (white pulp, red pulp, and marginal zone), which enables them to entrap and remove older cellular debris from the circulation (Figure 8B). In particular, the marginal zone is a specialized splenic environment that serves as a transitional site from circulation to peripheral lymphoid structures. Likewise, Figure 8C&D shows the fluorescence and confocal microscopy images of splenic marginal zones stained with DAPI. The high intensity of magenta color in the immunofluorescence analysis indicated the higher accumulation of ReApoBds-ICG in the marginal zone of spleen, predominantly in the macrophages. Taken together, the results of this study indicate that i.v. delivered ReApoBds-ICG rapidly trafficked to the spleen, distributed predominantly to the marginal zones of the spleen, and were internalized most likely into splenic macrophage cells. Next, we examined the in vivo peritoneal macrophage uptake efficiency in C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the intraperitoneal injection of ReApoBds-ICG was taken up by mouse peritoneal macrophages that express high levels of F4/80, CD11b (Figure 8E–H). These results were further confirmed using fluorescence microscopy observation, as mouse peritoneal macrophages showed intense ICG fluorescence when compared to control groups.

Figure 8.

Targeting macrophages with ReApoBds. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images of whole splenocytes isolated from ReApoBds-ICG injected mice. (B) H&E analysis of ReApoBds-ICG injected mice spleen section. The ICG fluorescence signals from the splenic marginal zone are highlighted in the figure. (C and D) Fluorescence and confocal microscopy images of splenic marginal zone stained with DAPI. The high intensity of ICG fluorescence (magenta) in the immunofluorescence analysis indicates the robust accumulation of ReApoBds-ICG in the marginal zone of mice spleen, predominantly in the macrophages. In vivo peritoneal macrophage uptake efficiency in C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice model. (E) Schematic outline shows the timeline of treatment conditions used for macrophage activation in vivo. (F and G) Flow cytometer analysis shows that the intraperitoneal injection of ReApoBds-ICG was taken up by the mouse peritoneal macrophages that express high levels of F4/80, CD11b. (H) Fluorescence microscopy observation as mouse peritoneal macrophages shows intense ICG fluorescence when compared to control groups.

S. aureus is a facultative anaerobe causing multiple pathologies, from cutaneous lesions to life-threatening sepsis, with mortality rates reaching 30%. Antibiotic resistance is a particular concern in S. aureus infection.28 S. aureus can invade and survive intracellularly in numerous mammalian cell types including phagocytic macrophages and nonphagocytic cancerous cells.1 The infected macrophages and cancer cells may act as “Trojan horses” to establish secondary infection foci, resulting in recurrent systemic infections.5 Additionally, S. aureus is the predominant pathogen in surgical site infections in cancer patients.3,34 The incidence of S. aureus infection with cancer patient populations has been increasing due to surgery, long-term intravenous catheterization, and repeated radiotherapy and chemotherapy and cancer patients suffer from bone marrow dysfunction, neutropenia, and mucosal barrier damage.35 Furthermore, accumulating evidence indicates that solid tumors such as glioblastoma of brain, adenocarcinomas of the breast, and hepatocellular carcinoma of the liver are considered the most aggressive hypoxic tumors that are prone for infection by obligatory or facultative anaerobic bacteria. It has been reported that bacteria can accumulate and actively proliferate within tumors, resulting in 1000 times or even a higher increase in bacterial numbers compared to normal tissues.15

The lack of a staphylococcal vaccine36 and the emergence of the MRSA strains make vancomycin one of the few remaining useful antibiotics for treatment against S. aureus infection, but it is limited by its nephrotoxicity. The toxicity also limits the dose that can be used for treatment. In addition, intracellular persistence of S. aureus may concomitantly serve to circumvent vancomycin treatment, and the repeated treatment regimens also increase the risk of developing resistance to this critical antibiotic.2 Hence, targeted intracellular delivery of vancomycin selectively to the S. aureus infected macrophages and cancer cells can address this problem by using a low dose of vancomycin and limiting nonspecific toxicity.

Inspired by their natural function and cargo delivery capabilities, in this study, we exploited tumor cell-derived ApoBds for their potential role in macrophage recognition and oncogenic niche formation as a vehicle for vancomycin delivery. We fabricated vancomycin loaded ReApoBds from different types of cancer cells (SKBR3, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, and LN229) using a mechanical extrusion process and characterized them for their physicochemical properties using DLS, NTA, and TEM microscopy (Figures 2 and 3). Our reconstruction process significantly reduced the size of ApoBds from their original size of 5–8 μm range to around 80–150 nm, and this process enhanced the encapsulation efficiency of vancomycin to 60 ± 2.56%. An in vitro release study of ReApoBds-vancomycin showed a sustained release with biphasic release profile (Figure 3F). Overall, our reconstruction method showed that we can finely tune the size of ReApoBds to load higher concentrations of vancomycin. In addition, our approach can promote the production of nanosized apoptotic cell-like vesicles that mimic the proteolipid signaling molecule of naturally released apoptotic bodies.

Cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles possess a natural ability to recognize cancer cells of the same type or cells with the expression of similar cell membrane proteins. This property is termed homotypic recognition. We have previously shown this property in vivo by delivering cancer-derived vesicles loaded with small therapeutic microRNAs.19 Similarly, macrophages can recognize cell debris and other apoptotic bodies from the systemic circulation and tissues through a “eat me” signaling property. Hence, to assess the expression profile of proteins from cancer cell-derived ApoBds, we performed mass spectrometric analysis of proteins from SKBR3-derived ApoBds and 4T1-cancer cell-derived EVs for comparison. The results showed proteins predominantly related to apoptotic and autophagy signaling pathways, which clearly support the recognition of these bodies by macrophages upon in vivo delivery (Figure 4). We also performed in vitro cell culture uptake assays in macrophage cells (RAW-264.7) and cancer cells (SKBR3, MDA-MB-231, U87-MG, and LN229) in monolayer 2D cultures and 3D spheroids. The results of various microscopic assays clearly monitored the specific recognition and intracellular delivery of these ReApoBds in macrophages and various cancer cells (Figures 5 and 6).

Antibiotics are constantly evolving to overcome resistance mechanisms developed by bacterial pathogens. Even though next-generation antibiotics are successful in controlling bacterial pathogens when they come in contact with bacteria directly, the bacteria that hide inside mammalian cells where these antibiotics cannot enter have been a major hurdle in treating bacterial infections. To overcome this barrier, a few studies have attempted to load antibiotics within nanoparticles to deliver directly into infected mammalian cells.37,38 In line with these investigations, in this study, we studied the intracellular bacterial killing efficacy of ReApoBds-vancomycin in S. aureus infected macrophages (RAW 264.7) and cancer cell lines (U87-MG and LN229 cells). We demonstrated that the ReApoBds loaded with vancomycin killed the intracellular bacteria efficiently compared to free vancomycin treated cells (Figures 5 and 6). The ReApoBds-vancomycin treated RAW264.7 cells show a 2 − log10CFU reduction compared to the free vancomycin treatment group. Overall, the ReApoBds loaded with vancomycin show an enhanced therapeutic potential for inhibiting intracellular S. aureus in macrophages and aggressive cancer cells. They are therefore promising for in vivo antibacterial treatment applications.

We previously showed that cancer CDVs can deliver therapeutic microRNAs to target tumors and achieve anticancer therapy.19 Since there are no previous accounts of the fate of ReApoBds in vivo, we investigated the biodistribution and organ-specific accumulation of ReApoBds labeled with ICG and coloaded with AntimiRNA-21 in healthy immunodeficient (nude mice) and immunocompetent (Balb/c) mice. Our fluorescence imaging study shows the time-dependent uptake of ReApoBds by the RES system, primarily by the liver and spleen. Further quantitative evaluations of AntimiRNA-21 biodistribution using qRT-PCR revealed that its distribution matches our fluorescence imaging results (Figure 7).

The apoptotic cell response in the splenic marginal zone has been proven to be a very dynamic process that requires a coordinated activity from B cells, NKT cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and regulatory T (Treg) cell populations working in parallel and sequentially to execute their functions.39 The marginal zone (MZ) of the spleen is a transitional site where the vasculature merges into a venous sinusoidal system.39 The MZ is populated by several innate-like lymphocytes and phagocytic cells (MZ B cells, MARCO+ and CD169+ macrophages) that are specialized to screen the blood for signs of infection and to serve a scavenging function for removal of particulate material, including apoptotic bodies, from the circulation. The coordinated activity of various immune cells ultimately leads to adaptive immunity including immunoglobulin responses against apoptotic cell antigens and antigen-specific FoxP3+ Tregs driving clearance and long-term tolerance. Nevertheless, in recent times, reports have highlighted the importance of the marginal zone for initiation of immune tolerance to apoptotic cells, driving a coordinated response involving multiple phagocyte and lymphocyte subsets. Hence, we assessed the splenic accumulation of macrophages in animals treated with ReApoBds. Our experimental results revealed that a significant number of the ReApoBds were colocalized within the splenic immune cells, predominantly to the marginal zones of spleens (Figure 8).

Macrophages of the murine peritoneal cavity are among the best studied tissue macrophage compartments.40 These peritoneal macrophages play critical roles in clearing apoptotic cells and coordinating inflammatory responses.41 A recent study indicated that macrophages within the peritoneal cavity are a channel of dissemination for intravenous S. aureus, and systemic administration of antibiotic does not prevent dissemination from this source further into the peritoneum or to the kidneys.42

CONCLUSION

We successfully developed ReApoBds nanocarriers that can deliver vancomycin specifically to an in vitro model of S. aureus infected macrophages and cancer cells. This model will enable further study of specific S. aureus interactions with host cells and will provide opportunities to develop different molecular therapies, such as targeted nanocarriers for antibiotic delivery, to treat intracellular bacterial infections. Our molecular imaging methods allow analysis of precise subcellular localization of S. aureus within macrophages and cancer cells. These techniques could provide better solutions to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of nanocarriers in numerous intracellular microbial infection models. Overall, we believe that our ReApoBds nanocarriers have the potential to greatly expand the utility of biomimetic NVs in targeted theranostic delivery and imaging, as would be pertinent to cancer immunotherapy and the nanotheranostics field. Importantly, in the context of problematic S. aureus infections, such as those caused by MRSA, our in vivo studies show that ReApoBds can specifically target macrophages and cancer cells. Vancomycin loaded ReApoBds have the potential to kill intracellular S. aureus infections in vivo within these macrophages and cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA) and used as received. Cell culture plates, FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, sodium bicarbonate, cell culture medium, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Frederick, MD). Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent and the Vibrant Multicolor Cell-Labeling Kit containing DiOC18 (3) (3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate) (DiO), 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine, and 4-chlorobenzenesulfonate salt (DiD) solutions, protein gels, and buffers for gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cy5-labeled AntimiR-21 RNA-oligo was synthesized from Protein and Nucleic acid facility at Stanford (PAN, Stanford).19

Methods.

Cell Culture and Bacterial Strains.

Human breast cancer cells (SKBR3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231), human glioblastoma cells (U87MG, GL26, T98G, and LN229), human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), the mouse breast cancer cells (4T1), and macrophage cells (RAW 264. 7) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured in accordance with the supplier’s instructions. S. aureus (methicillin-resistant strain of MW2 (MRSA-MW2) cells were used from the Mylonakis lab collection.

Preparation of Reconstructed ApoBds and Vancomycin Loaded Reconstructed ApoBds.

The different cancer cell-derived ApoBds were produced by serum starvation, as described previously.43 Briefly, the different cancer cells (human breast cancer cells (SKBR3, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231), human glioblastoma cells (U87-MG and LN229), human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), and mouse 4T1 breast cancer cells were plated to 80% confluence (4 × 106 cells/10 cm plate) for 24 h. They were then washed three times with PBS. We added 8 mL of serum-free DMEM with Pen/Strep for 72 h, and the cell apoptosis process was assessed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry using Hoechst 33342 and FITC-annexin V staining. The cell free culture medium was collected for the isolation of tumor cell-derived ApoBds (ApoBds), as shown in Figure S1 and as mentioned earlier.19 Briefly, the cell-free medium was collected and centrifuged at 300g for 5 min to remove cells and large debris. The supernatant was further centrifuged again at 2000g for 30 min to collect the apoptotic bodies, and the pellet was carefully resuspended in 300 μL of PBS. The isolated ApoBds from different cancer cells were mildly sonicated to break them into small proteolipid vesicles and then reconstructed with or without vancomycin (freeze and thaw) by a physical extrusion process using an Avanti mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.), as mentioned earlier.19

Characterization of Reconstructed ApoBds and Vancomycin Loaded Reconstructed ApoBds.

The mean particle diameter (z-average), size distribution (polydispersity index (PDI)), and the surface charge (the ζ potential) of reconstructed ApoBds and vancomycin loaded reconstructed ApoBds were determined using Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). For DLS measurements, we followed the optimized protocol reported previously by us.19 In brief, the samples were diluted in 18.2 MΩ water, and the data from at least three measurements were averaged. The ζ potential was measured at pH 7.4. For NTA analysis, reconstructed ApoBds and vancomycin loaded reconstructed ApoBds were further diluted 100- to 1000-fold in the media for the measurement of particle size and concentration. All NTA measurements were carried out using the Nano sight NS300 (Malvern Instruments). For each sample, three videos of 30–60 s with more than 200 detected tracks per video, and in at least one dilution, were taken and analyzed using the NTA 3.1 software at default settings.

Scanning Electron Microscopy.

Scanning electron microscopy was performed as previously described19,43 with some modifications. Cells grown on coverslips and ApoBds added on coverslips pretreated with poly-L-lysine were fixed using 4% PFA. The samples were then washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, fixed again with 1% osmium tetroxide (Agar Scientific, UK), and placed in a modified histology cassette for automated gradient ethanol dehydration (25%–100% alcohol, Lynx II Automated tissue processor, Electron Microscopy Sciences) before they were critical-point dried (Bal-tec850 Critical Point Dryer, Electron Microscopy Sciences). After drying the samples in a precise and controlled way, cells were mounted to aluminum stubs with carbon conductive tabs (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA). Finally, the specimens were gold-coated in a sputter coater (Cressington 108auto Sputter Coater, UK), prior to viewing under a scanning electron microscope. Micrographs were collected with the Sigma HDVP electron microscope (Zeiss) via secondary electron detector.

Field Emission Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Field emission TEM images of the ReApoBds were obtained using FEI-Tecnai G2 F20 X-TWIN that was operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Images were obtained using an ORIUS CCD camera through Digital Micrograph, and energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) were recorded through FEI-TIA interface. For sample preparation, 10 μL of ReApoBds suspension were drop casted on glow discharged copper grids with pure carbon support film, incubated for 10–15 min, and then washed with ultrapure water. Finally, the sample grids were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate solution, and excess solution was wicked away with absorbent paper before imaging.

Determination of Encapsulation Efficiency and Vancomycin Release from ReApoBds.

The drug encapsulation efficiency of ReApoBds-vancomycin was determined by HPLC method using an Agilent G1310A pump and an Agilent G1314A variable-wavelength detector set at 230 nm. Vancomycin was monitored at a wavelength of 230 nm with the column, InertSustain-C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm) (Shimazu-GL, JAPAN). The mobile phase composed of 0.05 mol/L potassium phosphate monobasic monopotassium phosphate solution (pH 3.2) and methanol (spectroscopic grade) (80:20, ml/ml) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. For the encapsulated vancomycin, the sample was extracted with a dichloromethane (DCM)/water system (50:50), and then the extracted vancomycin (0.1 mL) was injected into the HPLC system. The calibration graph was created by plotting vancomycin concentrations versus the corresponding peak heights. Linearity was observed in terms of coefficient of determination (r2). The concentration of vancomycin in each calibration standard was back-calculated using a calibration curve, and the percentage of encapsulated drug was determined. The cumulative vancomycin release from the ReApoBds was evaluated using a previously reported method.44 The release of vancomycin from the ReApoBds formulations was measured using Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis cups (Thermo Scientific) with a molecular weight cutoff of 10 kDa. The released vancomycin was quantified using HPLC, as described above.

Proteomic Analysis.

The isolated apoptotic bodies (SKBR3) or extracellular vesicles (4T1) were lysed with 100 μL of 2% SDS and 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) and homogenized using a Branson probe sonicator (Fisher Scientific) with an amplitude of 30%, 15 s on, followed by 30 s off in cold water. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 50 μg of protein per sample was used for subsequent LC/MS analysis. Proteins were reduced in 10 mM TCEP (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. Iodoacetamide (Acros Organics) was added to each sample for alkylation of proteins in 1.5-fold molar excess of TCEP, followed by incubation for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Each protein sample was digested overnight in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C with 2 μg of trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The resulting tryptic peptides were vacuum-dried and reconstituted in 100 μL of 0.1% formic acid (Fisher Scientific). Approximately 2 μg (4 μL samples) of tryptic peptides were analyzed using a Dionex Ultimate Rapid Separation Liquid Chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a LTQ-Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tryptic peptides were separated using C18-based reverse-phase chromatography. We used a C18 trap column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a 25 cm long C18 analytical column (New Objective) packed in house with Magic C18 AQ resin (Michrom Bioresources) in an acetonitrile gradient up to 35% B over 100 min, followed by an increase to 85% B over 7 min, with a 5 min hold (Phase A = 0.1% formic acid in water; B = 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.6 μL/min. The analytical column was re-equilibrated prior to the next sample injection, and each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Briefly, the MS spectra were acquired in a data-dependent fashion in which the top 10 most abundant ions per MS1 scan were selected for higher energy collision induced dissociation (35 eV). MS1 resolution was set at 60,000, FT AGC target was set at 1 × 106, and the m/z scan range was set from m/z = 400–1800. MS2 AGC target at 3 × 104, and dynamic exclusion was enabled for 30 s.

The resulting data were searched against the Swiss-Prot database containing the reference mouse proteome (2017; 17,191 entries) (4T1) or human proteome (2017; 20,484 entries) (SKBR3) using Byonic 2.11.0 (Protein Metrics), including the following search parameters: precursor mass tolerance <0.5 Da, fragment mass tolerance <10 ppm, and ≤2 missed cleavages. Cysteine carbamidomethylation (+57.021) was set as a fix modification, and methionine oxidation (+15.994) and asparagine deamidation (+0.984) were set as a variable modification. Peptide identifications were filtered for a false discovery rate of <1%. Protein abundances were calculated as the logarithm of the number peptide spectrum matches after normalization divided by the number of theoretically identifiable peptides (calculated as the number of fully tryptic peptides by in silico digestion within m/z range between 400 and 1800 Th using dbtoolkit)45 according to the iBAQ algorithm.46 Data were analyzed to determine the biological functions of identified proteins, and the proteins were categorized by gene ontology (GO) biological process, GO cellular component, GO molecular function, and biological pathway according to Uniprot database downloaded on February 22, 2019 and analyzed using FunRich 3.1.3.47 Finally, to determine the total number of proteins belonging to different apoptotic processes, the total signal of all proteins classified according to the cancer proteomics database was summed.48

Labeling of ApoBds Using ICG and DiD.

The ReApoBs were labeled with ICG by a conjugation process and with lipophilic dye (DiD) (3 μL of 1 mM concentration), as we published in our previous study.19 Briefly, the NH2-reactive ICG (125 μg) was mixed with 875 μg of protein equivalent of ReApoBds (1:7 dye to protein ratio) in 1 mL of 100 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.5) and kept in a shaker for 1 h with a constant mixing with DiD. After 1 h, the ICG conjugated ReApoBds were washed three times to remove unconjugated ICG before we extruded using a mechanical extrusion process.

Evaluation of Cellular uptake of ReApoBds in 2D and 3D Culture Models.

We investigated the macrophage and cancer cells uptake efficiency of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG in Raw and U87-MG and MDA-MB-231 cell lines (as model 2D cell lines) and 3D tumor spheroids of SKBR3, 4T1, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, GL26, and patient-derived glioma tumor spheroids (GBM2, GBM39). For 2D cell lines, cells were maintained as adherent cell cultures and passaged three times, after which a new frozen aliquot was used. Cell treatments were performed in adherent conditions. RAW 264.7, MDA-MB-231, and U87MG at a density of 5 × 103 in 96-well plates were treated with ReApoBds-ICG at 6 × 109 ReApoBds/ml. We also examined the time and concentration-dependent cell uptake of ReApoBds. For concentration-dependent uptake, the cells were treated with different concentrations (5, 10, and 20 μL, equivalent to 3 × 107, 6 × 107, 1.2 × 108 ReApoBds, respectively) of SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG in 100 μL of medium. For time-dependent uptake, the cells were treated with 10 μL of ReApoBds-ICG. After 24 and 48 h, the ICG fluorescence images were acquired using a florescence microscope (Olympus), IVIS Spectrum in Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer), as mentioned above.49

For 3D culture models, the tumor spheroids were produced with GFP expressing SKBR3, 4T1, MDA-MB-231, HepG2, U87-MG, GL26 and two patient-derived GBM lines (GBM2, GBM39) (Bioengineered by Prof. Ramasamy Paulmurugan and Dr. Edwin Chang at Stanford University). GBM2 originated from the Stanford University Medical Hospital and was obtained for research purposes after approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board. We gratefully acknowledge GBM39 as a gift from Dr. Paul Mischel (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, University of California at San Diego). The cells were cultured with matrigel and then treated with SKBR3-derived ReApoBds-ICG. After 48 h of ReApoBd treatment, bright-field and fluorescent images were acquired using a Celigo Imaging Cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, LLC, MA), as mentioned above.50

Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration.

Antibacterial susceptibility analysis was carried out according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Müller-Hinton broth (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to measure the MIC at a total assay volume of 100 μL. Two-fold serial dilutions were prepared between the concentration range 0.01 μg/mL and 64 μg/mL. An initial bacterial inoculum was adjusted to OD600 = 0.06 and incubated with test compounds at 37 °C for 18–20 h. After incubation, the plates were read at OD600, and the lowest concentration of compound that inhibited bacterial growth was reported as the MIC.

Intracellular Bacterial Killing Assay in Macrophages.

RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cells were used to investigate the intracellular infection of MRSA-MW2 and intracellular killing efficiency of vancomycin loaded ReApoBds. The MRSA-MW2 infection assays were carried out in triplicate. Briefly, macrophages were cultured and maintained as described above. Cells (50,000) were seeded in 24-well plates 24 h prior to infection. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) 25 (i.e., 25 bacterial cells per macrophage) of MRSA-MW2 were added to macrophages for 2 h to allow phagocytosis. Planktonic bacteria were removed, and DMEM with 200 μg/mL gentamicin was added to cells for 2 h to inhibit/kill remaining extracellular bacteria. Antibiotic and serum-free DMEM with or without formulations were added, and the cells were incubated under 5% CO2 for 20 h. Intracellular S. aureus bacterium is able to replicate in and release from macrophages. To assess the intracellular and released bacterial cells, SDS was added to a final concentration of 0.02% (i.e., lyses only macrophages and not ingested bacteria). To assess the intracellular killing alone, the supernatant was removed and washed with PBS twice, and DMEM with 0.02% SDS was added to lyse macrophage to release intracellular bacteria. Cell lysates were diluted serially, and CFUs were enumerated by plating on TSA plates (total viable count). Free vancomycin (8 μg/mL) was used as a positive control and DMSO at a final concentration of <0.1% as the negative control.

Intracellular Bacterial Killing Assay in Aggressive Glioblastoma Cell Lines.

Aggressive brain cancer (glioblastoma) cell lines were used to evaluate the infection efficiency of MRSA-MW2 in the presence of various formulations (8× MIC). Assays were carried out in triplicate as described previously5 with minor modifications. Briefly, cell lines were cultured and maintained, as described previously. Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) was coated to the 24-well plates 1 h prior to seeding the cells to promote the improved adherence and to prevent the wash off of cells during the cell washing procedure with PBS and various treatment conditions. Cells (50,000) were seeded in 24-well plates 24 h prior to infection. The MOI 25 (i.e., 25 bacterial cells per macrophage) of MRSA-MW2 was added to macrophages for 2 h. Planktonic bacteria were removed, and DMEM with 200 μg/mL gentamicin was added to cells for 2 h to inhibit/kill the remaining extracellular bacteria. Antibiotic and serum-free DMEM with or without formulations was added, and the cells were incubated under 5% CO2 for 20 h. Invaded S. aureus bacteria present in the cell lines were targeted to kill using the formulations. To assess the invaded bacterial cells inside the cancer cell lines, SDS was added to a final concentration of 0.02% (i.e., lyses only cancer cells and not ingested bacteria). Cell lysates were diluted serially, and CFUs were enumerated by plating on TSA plates (total viable count). Vancomycin (8 μg/mL) was used as a positive control and DMSO at a final concentration of <0.1% as the negative control.

Live/Dead Cell Staining Assay.

Mouse macrophages (RAW 264.7 cells) and cancer cell lines (U87-MG, LN229) were used in this assay. The macrophages were seeded in the round coverslip. Matrigel was coated in the coverslip prior to seeding the cancer cells. The coverslip was placed in the 6-well cell culture dish, and the infection assay was carried out as described previously and stained as described.51 After incubation, the cells were washed by 0.1 M 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7.2, containing 1 mM MgCl2 (MOPS/MgCl2). Live/dead cell staining experiments were carried out using a kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The macrophages were stained by 0.5 mL of live/dead staining solution (5 μM SYTO 9, 30 μM PI with 0.1% saponin in MOPS/MgCl2). The cells were then stained with SYTO 9 and PI for 30 min and visualized using confocal and super resolution microcopy techniques (TCS SP8; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

In Vivo Biodistribution Studies.

All animal studies were performed according to an approved protocol by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at our University. Nude (nu/nu) and C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) purchased from Charles River were used to investigate the biodistribution of ReApoBds. For biodistribution analysis, nude or C57BL/6 animals were systemically administered with 150 μL of ReApoBds-ICG (5 × 1011 ApoBds particles) on day 0 and imaged at days 1 and 4, using a Lago Spectral Imaging system for fluorescence. In parallel, free ICG was administered in a separate group of healthy immunogenic mice and imaged in a similar way as a control for biodistribution.

To determine the biodistribution of ReApoBds loaded with biomolecules, we used AntimiR-21 RNA as a model biomolecule for accurate quantification using real-time PCR. First, we produced AntimiR-21 RNA loaded SKBR3 ReApoBds as mentioned earlier. Briefly, the SKBR3 cells were plated to reach 80% confluence (4 × 106 cells/10 cm plate) 24 h before transfection. After 24 h, the cells were washed once with PBS, and 8 mL of fresh medium was added. For transfection, 5 nmol of Cy5-antimiR-21 was complexed with 25 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent in 1 mL of serum free optiMEM, as per manufacturer’s instruction. After 45 min of incubation at room temperature in the dark, the complex was mixed well and added to the plates. After 16 h of transfection, the plates were washed twice with PBS, and 8 mL of serum free DMEM with Pen/Strep was added for 72 h. The medium was collected and used for the production AntimiR-21 RNA loaded ReApoBds. Finally, all the animals were sacrificed, and the organs (liver, spleen, kidney, heart, lungs, and brain) were collected and used for ex vivo FLI, histology, and RNA isolation. For antimiR-21 biodistribution in different organs, we used Taqman real-time qRT-PCR following the protocol mentioned earlier.19 We used mouse sno234 miRNA as a housekeeping miRNA for normalization.

Histopathology and Morphometric Studies.

To investigate the acute toxicity of ReApoBds using histopathology, C57BL/6 animals were systemically administered with either 150 μL of ReApoBds ICG (5 × 1011 ApoBds particles) derived from SKBR3 or PBS for three consecutive doses, each one 3 days apart. The mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last injection, and the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys were collected and processed for histological analysis. The tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (pH 7.0) and processed by conventional methods to obtain paraffin sections. The embedded paraffin sections were cut into 5 μm thickness and then stained with H&E for subsequent microscopic grading and analysis.

Photoacoustic imaging.

Hemispherical photoacoustic (PA) imaging system (Nexus 128 scanner, Endra Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) was applied to monitor the ReApoBds accumulation in the liver and spleen of mice.52 The laser wavelength was tunable from 680/745 to 980/830 nm for PA signal excitation. A planoconcave lens was used for laser beam expansion. The incident energy density on the mouse brain surface was about 0.86 mJ cm−2, which is well below the American National Standard Institute safety threshold of 20 mJ cm−2. The mouse was held by a custom-built plastic tray. A water circulation system was used to maintain the temperature of the water at 37 °C to avoid hypothermia in mice. Ultrasound detection was achieved through a hemispherical ultrasonic device that consists of 128 ultrasonic transducers. Then, the PA signals were transferred to a computer for data reconstruction. A complete circular scan usually takes ≈1.7 min. The spatial resolution of this imaging system is about 200 μm.

Uptake of ReApoBds by Peritoneal Macrophages in Vivo.

The C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice were injected intraperitoneally with sterile Brewer-thioglycolate medium (2 ml, 4% w/v) to recruit macrophages to the peritoneal cavity. On day 4 post-thioglycolate injection, ReApoBds-ICG in PBS 150 μL of ReApoBds ICG (5 × 1011 particles) were injected intraperitoneally. After 24 h post-injection of the NPs, the mice were sacrificed for macrophage collection from the peritoneal cavity using ice-cold PBS. The cell pellets obtained after centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 min were suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics and used a fraction for microscopy and FACS analysis, while the rest were cultured in a Lab-Tek II chamber slide and a 6-well plate for 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, followed by washing three times with PBS to remove non-adherent cells. Peritoneal macrophages were then blocked with BSA (3%) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by staining with FITC-conjugated antimouse F4/80 antibody (specific marker for mouse macrophages) and C11b NIR-Red-antimouse at room temperature for 1 h and then analyzed by flow cytometer.

Uptake of ReApoBds by Splenic Marginal Zone Cells.

We investigated the accumulation of ReApoBds in splenic MZ macrophages in mice. Nude or C57BL/6 animals were systemically administered with 150 μL of ReApoBds ICG (5 × 1011 ApoBds particles). Then the mice were sacrificed on day 4 and the spleen collected and processed for histological and immunohistochemical analysis.

Statistical Analyses.

Student’s t-test was performed for all statistical analyses. P-values are indicated. Differences were statistically significant when the p-value was <0.05.

Supplementary Material

Video S1: The movie showing Z-stack confocal microscopic images of MRSA-MW1 (S. aureus) bacterial strain internalized into the phagosome compartment of macrophages, and treatment with ReApoBds-vancomycin killed most of the intracellular bacteria as assessed by Live/Dead assay. (AVI)

Video S2: The representative 3D reconstructed super-resolution lighting microscopy Z-stack images showing the MRSA-MW2 (S. aureus) internalization into the phagosome compartment of macrophages and intracellular killing efficacy of S. aureus by ReApoBds-vancomycin as assessed by Live/Dead assay. (AVI)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Canary Center at Stanford, Department of Radiology for facility and resources. We also thank SCi3 small animal imaging service center, Stanford University School of Medicine for providing imaging facilities and data analysis support. This research was supported by NIH R01CA209888, NIH R21EB022298, the Focused Ultrasound Society, and the Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation. We also acknowledge NIH shared instrument grant (1S10OD023518-01A1) for the purchase of Celigo Optical Imaging System which was used for collecting data used in this manuscript. This work was also supported by the Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence for Translational Diagnostics (CCNE-TD) at Stanford University through an award (grant no: U54 CA199075) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c00921.

Schemes and figures detailing in vitro uptake of ReApoBds in 2D cell cultures and 3D spheroids, intracellular vancomycin delivery and bacterial killing efficiency, and in vivo biodistribution using optical imaging are provided as Figures S1–S26. Table S1 provides the DLS and NTA results of ReApoBds derived from different cancer cells, and Tables S1 and S2 provide the protein profile of ReApoBds derived from 4T1 and SKBR3 cells, respectively. (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c00921

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Rajendran J. C. Bose, Department of Radiology, Molecular, Imaging Program at Stanford (MIPS), Stanford University, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 94305, United States

Nagendran Tharmalingam, Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital and Alpert, Medical School of Brown University, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States.

Fernando J. Garcia Marques, Department of Radiology, Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection, Stanford, University School of Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California 94305, United States.

Uday Kumar Sukumar, Department of Radiology, Molecular, Imaging Program at Stanford (MIPS), Stanford University, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 94305, United States.

Arutselvan Natarajan, Department of Radiology, Molecular, Imaging Program at Stanford (MIPS), Stanford University, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 94305, United States.

Yitian Zeng, Department of Radiology, Molecular Imaging, Program at Stanford (MIPS), Stanford University School of, Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California 94305, United States.

Elise Robinson, Department of Radiology, Molecular Imaging, Program at Stanford (MIPS), Stanford University School of, Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California 94305, United States.

Abel Bermudez, Department of Radiology, Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection, Stanford University School, of Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California 94305, United States.