Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

We previously established that housing loss and residential dislocation in the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami was a risk factor for cognitive decline among older survivors. The present study extends the follow-up of survivors out to 6 years.

METHODS:

The baseline for our natural experiment was established in a survey of older community-dwelling adults who lived 80 km west of the epicenter 7 months before the earthquake and tsunami. Two follow-up surveys were conducted approximately 2.5 years and 5.5 years after the disaster to ascertain housing status and cognitive decline from 2,810 older individuals (follow-up rate through three surveys: 68.4%).

RESULTS:

The experience of housing loss was persistently associated with cognitive disability (coefficient = 0.14, 95% confidence interval: 0.04 to 0.23).

DISCUSSION:

Experiences of housing loss continued to be significantly associated with cognitive disability even after six years after the disaster.

Keywords: Natural disaster, cognitive decline, Japan, panel data, natural experiment

Introduction

Older individuals are particularly vulnerable in the aftermath of natural disasters. For example, following Hurricane Katrina, 63 percent of deaths occurred among older people aged 65 or older (608 older people out of 971 total fatalities)[1]. During the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami, 66% of the victims (10,360 older people out of 15,681 total fatalities) who lost their lives were aged 65 years and older [2].

In contrast to the wealth of evidence on the lingering mental health effects of exposure to a natural disaster (e.g., studies of PTSD), there is a critical gap in the literature documenting the health impacts specific to the needs of aging populations. Studies conducted in the aftermath of disaster – e.g. the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami [3, 4] as well as Hurricanes Katrina/Rita [5, 6]—have documented a high prevalence of dementia or accelerated cognitive decline among older survivors. Plausible mechanisms have been put forward to explain the connection between disaster experience and cognitive decline, including the direct effects of psychological trauma and residential dislocation leading to social isolation [7]. However, causal inference in existing studies has been hampered by small samples, cross-sectional designs, the lack of an appropriate control group of individuals who were not exposed to disaster, the absence of information on risk factors for cognitive decline pre-dating the disaster, and/or relatively short follow-up durations.

We previously reported a linear dose-response relation between the severity of disaster-related housing damage and cognitive decline, using two waves of panel data that was collected (respectively) seven months before and 2.5 years after the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami [7]. From the result of mediation analysis, we suggested two plausible mechanisms linking property damage to cognitive decline among older people: 1) new onset of depression and 2) disruption of social contacts.

After the disaster, many survivors who lost their homes were moved into temporary housing communities [kasetsu jutaku], resembling Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster relief trailer communities in the United States. At the end of April 2016, the temporary housing community in our field site (Iwanuma city, Miyagi prefecture) was closed, and the majority of residents moved to a permanent housing community comprising a mix of new private housing and government provided rental housing.

In the present study, we explored the long-term influence of housing damage/residential relocation on cognitive disability 5.5 years later the disaster.

Methods

Study participants.

The Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) was established in 2010 as a nationwide sample of community-dwelling residents aged 65 years or older. One of the field sites of the JAGES cohort is based in the city of Iwanuma (total population 44,187 in 2010). We mailed questionnaires to every resident aged 65 years or older in August 2010 (n=8,576), using the official residential register of Iwanuma City. The survey inquired about personal characteristics, life style, and health status. The response rate was 59.0% (n = 5,058), which is comparable to other surveys of community-dwelling residents [8].

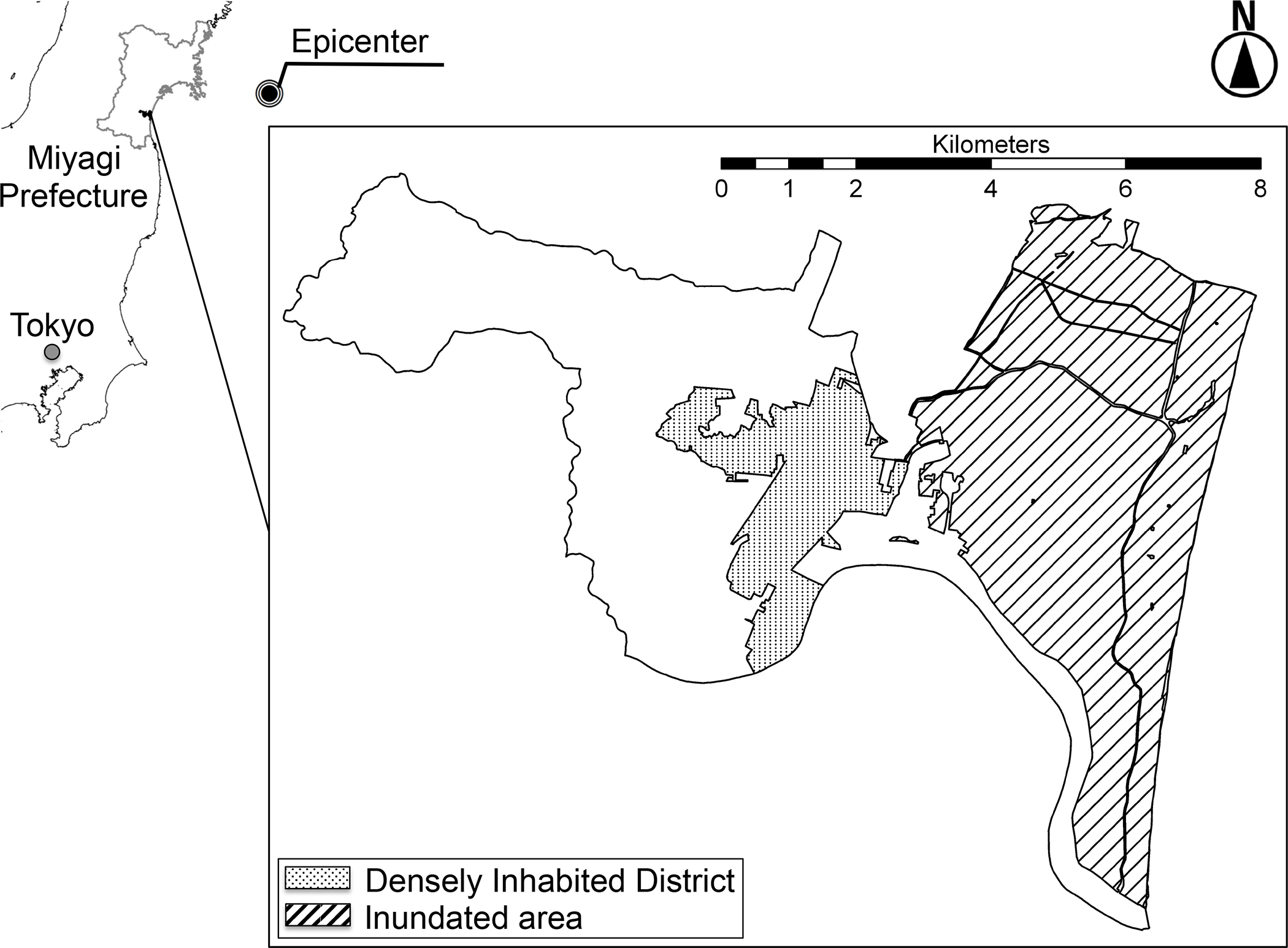

The earthquake and tsunami occurred on March 11, 2011, seven months after the baseline survey was completed. Iwanuma city is a coastal municipality located approximately 80 kilometers west of the earthquake epicenter that it was in the direct line of the tsunami. That disaster killed 180 of the town’s residents, damaged 5,542 housing units and inundated 48% of the land area (Figure 1) [9].

Figure 1.

Map of the Tsunami Inundated Area in Iwanuma City, Japan

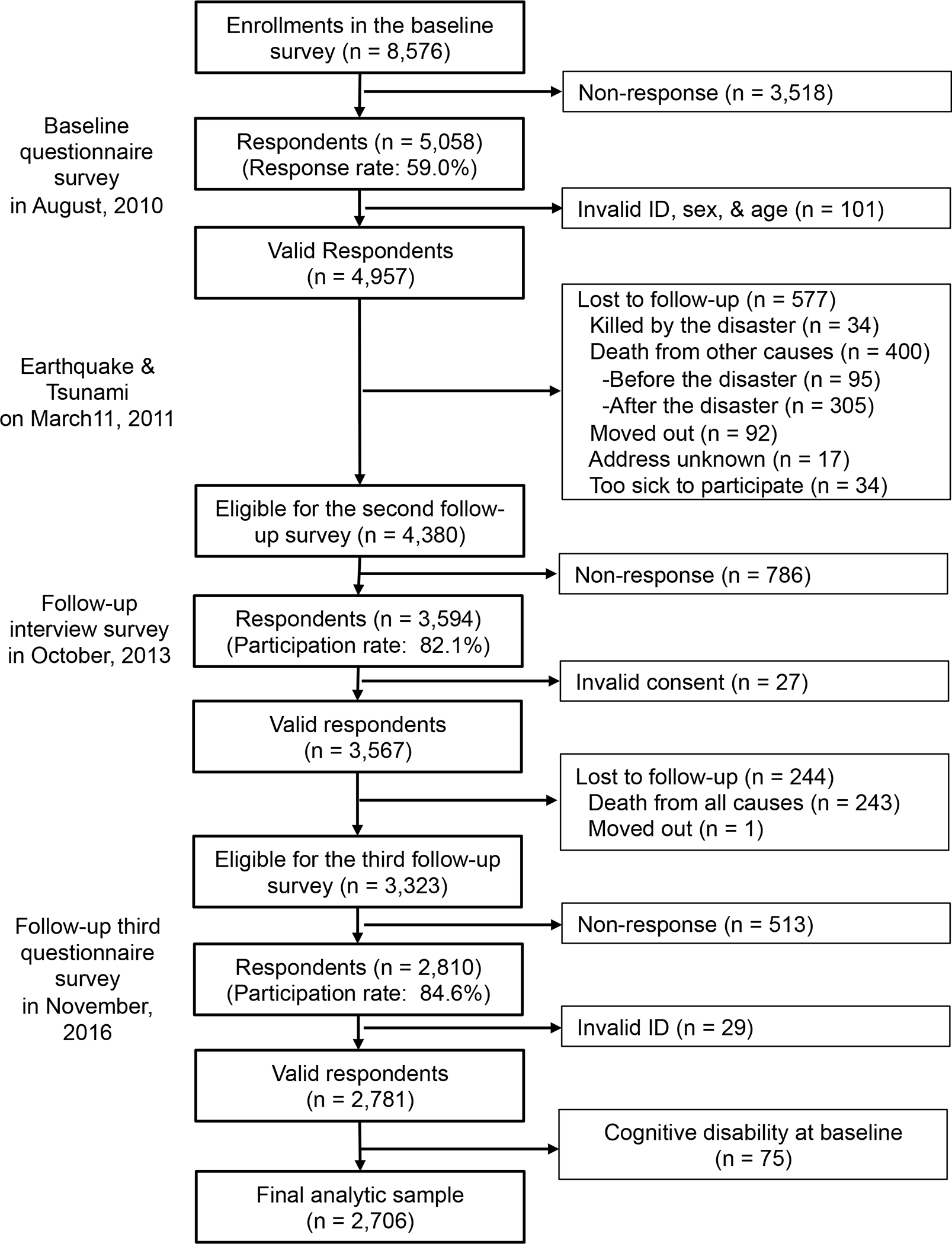

Approximately 2.5 years after the disaster (starting October 2013), we conducted the follow-up survey of survivors. The survey gathered information about personal experiences during the disaster as well as updated information about health status. The detailed flow-chart of the analytic sample is presented in Figure 2. Of the 4,380 eligible participants from the baseline survey, we managed to re-contact 3,594 individuals (participation rate: 82.1%). From the participants, 27 individuals were excluded due to incompletely signed informed consent forms.

Figure 2.

Participants Flow for Analytic Sample (n = 2,706)

Approximately three years after the second survey, we administered the third survey wave to respondents who answered the prior two surveys. We updated their health status and housing status. As shown in Figure 2, we collected data from 2,810 individuals (participation rate: 84.6%, follow-up rate through three surveys: 68.4%) and dropped 29 respondents due to invalid identification. Finally, the analytic sample was 2,706 respondents, after excluding 75 respondents who had cognitive disability at baseline.

The respondents were then linked to the national long-term care insurance (LTCI) registry, which includes information about cognitive status and disability based on an in-home assessment by trained investigators (e.g., public health nurse).

Outcome variable.

Our primary outcome is level of cognitive disability assessed by a standardized in-home assessment under the Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) scheme established in 2000 [10]. Registration in this LTCI scheme is mandatory, and each applicant requesting long-term care is assessed for eligibility to receive services (e.g., home help) by a trained investigator dispatched from the certification committee in each municipality.

During the home visit, each individual is assessed with regard to their activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, cognitive function (e.g., short-term memory, orientation, and communication) as well as mental and behavioral disorders (e.g., delusions of persecution and confabulation) using a standardized protocol. Following the assessment, the applicants are classified into one of 7 levels (1: Suffering some cognitive deficits, but otherwise almost completely independent – 7: Needs constant treatment in a specialized medical facility) according to the severity of their cognitive disability (Table 1). The index of cognitive decline is strongly correlated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (Spearman’s rank correlation ρ = −0.73, p < .01) [11] and level I of the cognitive disability scale has been demonstrated to correspond with a 0.5 point rating on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (both specificity and sensitivity were 0.88) [12].

Table 1.

Criteria for Levels of Cognitive Decline in the Japanese Long-term Care Insurance System

| Rank | Criteria | Examples of observable symptoms or behaviors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Suffers from some cognitive decline, but the daily living is almost all independent in the domestic and social spheres. | ||

| II | Manifests some symptoms/behaviors and communication difficulties that may hinder the daily activities, but can be independent if someone takes care of them. | ||

| IIa | The above-mentioned conditions in II are observed while outside the domestic sphere. | Frequently gets lost on the street, or makes noticeable mistakes in matters that the person was previously able to handle, such as shopping, personal administrative tasks, or financial management. | |

| IIb | The above-mentioned conditions in II are also observed within the domestic sphere. | Is unable to manage taking medication or stay alone at home due to an inability to answer the phone or the door. | |

| III | Occasionally manifests communication difficulties or symptoms/behaviors that hinder daily activities, thus requiring care. | ||

| IIIa | Manifests above-mentioned conditions described in III predominantly during the day. | Has difficulty or takes time to change clothes, take meals, defecate, or urinate; puts objects into the mouth, picks up and collects objects, is incontinent, makes loud and incoherent screams, carelessly handles fire, or engages in unhygienic acts or inappropriate sexual acts, etc. | |

| IIIb | Manifests above-mentioned conditions described in III predominantly at night. | Same as rank IIIa. | |

| IV | Frequently manifests difficulties communicating or symptoms/behaviors that hinder daily activities and constantly requires care. | Same as rank III. | |

| M a | Manifests significant mental symptoms, problematic behaviors, or severe physical illnesses and requires specialized medical care. | Shows continued mental symptoms, such as delirium, delusions, and agitation, and manifests associated problematic behaviors, such as self-mutilation or harm to others. | |

Needs special medical treatments

The initial certification is valid for six months, after which periodic re-assessments are conducted every 12 months [10]. Individuals and their caregivers can request a re-assessment before the expiration date if their health status changes markedly.

The committee also asks a panel of physicians to independently assess the cognitive disability level of applicants to determine the care requirements of the applicants [13]. The medical assessment is conducted independently of the in-home assessment, but we confirmed a high correlation between these two methods of assessment (Pearson’s correlation γ= 0.80, p < .01). In our primary analyses, we used the in-home assessment for our outcome, but in sensitivity analyses, we also used the medical examination data.

We linked JAGES cohort participants to the LTCI register in Iwanuma city for the follow-up period from April 1, 2010, to December 2, 2016. These data include the results of the initial assessment as well as subsequent re-assessments for each individual.

Explanatory variables.

Our primary exposure variable is disaster-related housing damage. We asked each respondent to report the results of the objective residential damage assessment performed by two or more technical officers who categorized the level of housing damage into five levels (1: No damage; 2: Partial damage; 3: Minor; 4: Major; and 5: Destroyed) (eTable 1). On the 3rd survey wave we also assessed each respondent’s housing status. At the end of April 2016, the temporary housing community was closed and the residents were moved to a permanent housing community comprised of a mix of new private housing and government provided rental housing.

We thus categorized housing status into three groups: 1) no relocation; 2) house damaged, moved to temporary housing, then moved into new private housing in the permanent housing community; and 3) house damaged, moved to temporary housing, then moved into government provided rental housing in the permanent housing community.

Covariates and mediators.

We selected several demographic variables as potential confounding variables for cognitive disability: Age, sex, income [14], educational attainment [15], divorce or bereavement [16], and employment status [17]. We also controlled for experiences of loss of relatives and/or friends in the disaster.

We additionally examined a set of variables as potential mediators of the relation between housing damage/change of housing status, and cognitive disability. These variables included: Alcohol drinking [18], smoking [19], depressive symptoms (measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale-15) [20], medical diagnoses of stroke [21] and diabetes [22], declines in frequency meeting with friends [7], interaction with neighbors [7], and daily walking time [23]. Frequency of meeting with friends ranged from “four or more times a week” to “rarely” (6-point scale). Interactions with neighbors was asked in terms of how close the respondents felt to their neighbors, ranging from “mutual consultation, lending and borrowing of daily commodities, cooperation in daily life” to “none, not even greeting neighbors” (4-point scale)

Household income was equivalized by dividing the gross income by the square root of the number of household members [14]. Depressive symptoms were categorized into lower risk (4 points and under) versus higher risk (5 points and over) [24].

Statistical analysis.

To address clustering due to the repeated measures design, we used a random effects model (multiple waves of data clustered within individuals) to calculate coefficients and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between housing damage/change in housing status, and cognitive decline.

To address potential bias due to missing data, we conducted multiple imputation by the Markov chain Monte Carlo method, assuming missingness at random for covariates. We created twenty imputed data sets and combined each result of analysis using the Stata command “mi estimate.” All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 (STATA Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Comparing our analytic sample with data from the local census at baseline (eTable 2), we can see that women made up 56.1% of our analytic sample, which is quite comparable to the actual census of older residents in Iwanuma city in October 2010 (male 42.8%, female 57.2%) [25]. The age distribution of our sample is close to the local census data except for the group aged 85 years and over (respondents 3.1%, census data 13.2%) [25]. A higher proportion of our respondents were married (76.6%) compared to the census data (64.7%) [26]. The proportion of employed individuals in our data (19.3%) is also close to the census data (17.2%) [27]. These comparisons support the representativeness of our data relative to Iwanuma city as a whole.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of respondents at baseline (before the disaster), at follow-up 2.5 years after the disaster, and at follow-up 5.5 years after the disaster. The prevalence of cognitive disability increased over time (4.9% in the second wave, 13.0% by the third wave). Among respondents, 58.4% reported personal damage to their property at the second wave (see further description of property damage in eTable 1). By the time of the third wave, 1.3 % had purchased new housing and 1.2% were renting government provided hosing in the permanent housing community.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Analytic Sample at Baseline, Second and Third Wave

| Baseline : 7 months before the disaster (August, 2010) |

Second wave: 2.5 years after the disaster (October, 2013) |

Third wave: 5.5 years after the disaster (November, 2016) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| n | % | Mean | SD | n | % | Mean | SD | n | % | Mean | SD | |

| Cognitive impairment level | ||||||||||||

| Independent | 2706 | 100 | 2572 | 95.1 | 2355 | 87.0 | ||||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 82 | 3.0 | 196 | 7.2 | ||||||

| IIa | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0.4 | 45 | 1.7 | ||||||

| IIb | 0 | 0 | 31 | 1.2 | 71 | 2.6 | ||||||

| IIIa | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.3 | 29 | 1.1 | ||||||

| IIIb | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.3 | ||||||

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||||

| M a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Housing damageb | ||||||||||||

| No damage | 1066 | 39.3 | ||||||||||

| Affected | 1176 | 43.5 | ||||||||||

| Minor | 194 | 7.2 | ||||||||||

| Major | 99 | 3.7 | ||||||||||

| Destroyed | 109 | 4.0 | ||||||||||

| Missing | 62 | 2.3 | ||||||||||

| Housing status at 3rd wave c | ||||||||||||

| No relocation | 2640 | 97.5 | ||||||||||

| Private new housing | 35 | 1.3 | ||||||||||

| Government provided housing | 31 | 1.2 | ||||||||||

| Loss of relatives and/or friendsb | ||||||||||||

| No | 1651 | 61.0 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1055 | 39.0 | ||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| (Continuous, years) | 2706 | 100 | 72.6 | 5.56 | 2706 | 100 | 75.8 | 5.57 | 2706 | 100 | 78.9 | 5.57 |

| Sex c | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1187 | 43.9 | ||||||||||

| Female | 1519 | 56.1 | ||||||||||

| Equivalized income | ||||||||||||

| (Continuous, 10,000 JPY) | 2271 | 83.9 | 231.50 | 137.31 | 2324 | 85.9 | 220.06 | 134.21 | 1975 | 73.0 | 216.83 | 139.99 |

| Missing | 435 | 16.1 | 382 | 14.1 | 731 | 27.0 | ||||||

| Education d | ||||||||||||

| 1: <6 y – 4: ≥13 y | 2631 | 97.2 | 2.88 | 0.75 | ||||||||

| Missing | 75 | 2.8 | ||||||||||

| Divorce or widowed | ||||||||||||

| No | 2015 | 74.5 | 1931 | 71.4 | 1760 | 65.0 | ||||||

| Yes | 615 | 22.7 | 737 | 27.2 | 825 | 30.5 | ||||||

| Missing | 76 | 2.8 | 38 | 1.4 | 121 | 4.5 | ||||||

| Employment | ||||||||||||

| No | 1939 | 71.6 | 2257 | 83.4 | 1792 | 66.2 | ||||||

| Yes | 465 | 17.2 | 373 | 13.8 | 283 | 10.5 | ||||||

| Missing | 302 | 11.2 | 76 | 2.8 | 631 | 23.3 | ||||||

| Current drinking | ||||||||||||

| No | 1609 | 59.5 | 1765 | 65.2 | 1671 | 61.8 | ||||||

| Yes | 1046 | 38.7 | 924 | 34.2 | 842 | 31.1 | ||||||

| Missing | 51 | 1.9 | 17 | 0.6 | 193 | 7.1 | ||||||

| Current smoking | ||||||||||||

| No | 2222 | 82.1 | 2472 | 91.4 | 2348 | 86.7 | ||||||

| Yes | 282 | 10.4 | 217 | 8.0 | 197 | 7.3 | ||||||

| Missing | 202 | 7.5 | 17 | 0.6 | 161 | 6.0 | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||||||||

| 4 points or below | 1682 | 62.2 | 1675 | 61.9 | 1413 | 52.2 | ||||||

| 5 points or above | 688 | 25.4 | 714 | 26.4 | 589 | 21.8 | ||||||

| Missing | 336 | 12.4 | 317 | 11.7 | 704 | 26.0 | ||||||

| Stroke | ||||||||||||

| No | 1989 | 73.4 | 2172 | 80.2 | 2203 | 81.4 | ||||||

| Yes | 50 | 1.9 | 110 | 4.1 | 119 | 4.4 | ||||||

| Missing | 667 | 24.7 | 424 | 15.7 | 384 | 14.2 | ||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| No | 1707 | 63.0 | 1919 | 70.9 | 1934 | 71.5 | ||||||

| Yes | 332 | 12.3 | 363 | 13.4 | 388 | 14.3 | ||||||

| Missing | 667 | 24.7 | 424 | 15.7 | 384 | 14.2 | ||||||

| Frequency meeting with friends | ||||||||||||

| 1: ≥ 4/weeks – 6: Rarely | 2615 | 96.6 | 3.24 | 1.44 | 2675 | 98.9 | 3.28 | 1.51 | 2572 | 95.0 | 3.42 | 1.55 |

| Missing | 91 | 3.4 | 31 | 1.1 | 134 | 5.0 | ||||||

| Frequency of interactions with neighbors | ||||||||||||

| 1: Frequently – 4: None | 2632 | 97.3 | 1.95 | 0.66 | 2687 | 99.3 | 2.02 | 0.67 | 2625 | 97.0 | 2.04 | 0.71 |

| Missing | 74 | 2.7 | 19 | 0.7 | 81 | 3.0 | ||||||

| Walking time per day | ||||||||||||

| 1: ≥ 90 min. – 4: < 30 min. | 2604 | 96.2 | 2.92 | 1.02 | 2677 | 98.9 | 2.86 | 1.02 | 2530 | 93.5 | 2.98 | 1.03 |

| Missing | 102 | 3.8 | 29 | 1.1 | 176 | 6.5 | ||||||

Needs special medical treatments

Measured at only the second/third wave

Empty cells due to time-invariant variables.

Abbreviations: JPY, Japanese Yen.

Proportions of stroke and diabetes increased during the follow-up period (1.9% to 4.4% for stroke, 12.3% to 14.3% for diabetes).

As shown in model 1 of table 3, the random effects model showed that experiences of housing damage in the 2011 disaster remained associated with cognitive decline in a linear dose-response manner even 5.5 years later, although only the category of total housing destruction showed a significant association with the cognitive impairment (coefficient = 0.14, 95% confidence interval: 0.04 to 0.23, p = 0.005). Among the different types of housing arrangement at the third wave, living in government provided rental housing was significantly associated with high risk of cognitive impairment (coefficient = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.22 to 0.56, p < .001).

Table 3.

Housing damage, Housing Status at the Third Wave and Cognitive Disability Assessed by Trained Investigators

| Model 1: Exposures and demographic variables | Model 2: Added mediating variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p | Coefficient (95% CI) | p | |

| Housing damage (ref: no damage) | ||||

| Partial | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | 0.57 | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.48 |

| Minor | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.14) | 0.10 | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.13) | 0.11 |

| Major | 0.07 (−0.03, 0.17) | 0.18 | 0.07 (−0.03, 0.16) | 0.18 |

| Destroyed | 0.14 (0.04, 0.23) | 0.005 | 0.12 (0.03, 0.22) | 0.01 |

| Housing status at the third wave | ||||

| new private house | 0.05 (−0.11, 0.21) | 0.58 | 0.06 (−0.10, 0.22) | 0.48 |

| government-provided housing | 0.39 (0.22, 0.56) | < .001 | 0.36 (0.19, 0.53) | < .001 |

| Loss of relatives and/or friends | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.99 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.72 |

| Age (years) | 0.02 (0.02, 0.02) | < .001 | 0.02 (0.01, 0.02) | < .001 |

| Female | 0.04 (0.01, 0.06) | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 2M JPY equivalized income | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.95 | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.18 |

| Educational attainment (years) | −0.02 (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.09 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | 0.15 |

| Divorce or widowed | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.001 | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07) | 0.007 |

| Employment status | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.63 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.70 |

| Survey year (ref: 2010) | ||||

| 2013 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.77 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.04) | 0.89 |

| 2016 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | < .001 | 0.11 (0.09, 0.14) | < .001 |

| Drinking | −0.04 (−0.07, −0.01) | 0.02 | ||

| Smoking | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.04) | 0.96 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | < .001 | ||

| Stroke | 0.25 (0.19, 0.31) | < .001 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.37 | ||

| Decreased frequency meeting friends | 0.06 (0.04, 0.08) | < .001 | ||

| Decreased interactions with neighbors | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.003 | ||

| Decreased walking time per day | 0.03 (0.02, 0.05) | < .001 | ||

| Constant | −0.45 (−0.66, −0.25) | < .001 | −0.55 (−0.76, −0.33) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; M, million; JPY, Japanese Yen.

Model 2 added the potential mediators. The onset of depression and stroke (coefficient = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.13, p < .001; coefficient = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.31, p < .001, respectively), and decreased frequency meeting with friends, interactions with neighbors, and daily walking time were also significant (coefficient = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.08, p < .001; coefficient = 0.01, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.02, p = .003; coefficient = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.05, p < .001, respectively). The addition of these mediators partially attenuated the effects of housing damage and subsequent change of housing status on cognitive disability. The most influential mediator was the onset of stroke.

The sensitivity analyses using the cognitive disability assessed by medical examination also showed the same results (eTable 3).

Discussion

Our study shows that even 5.5 years after the 2011 disaster, the experience of housing damage was persistently associated with the cognitive decline of older survivors. We have previously hypothesized that this association is partly explained by the loss of social connections (informal socializing with neighbors) as a result of residential relocation to the temporary trailer community [28]. By the time of the 3rd wave survey of our study (conducted 5.5 years after the disaster), the temporary trailer community had been closed down by the local municipality, and residents had a choice of moving to a newly built permanent community (consisting of a mix of privately owned or government rental property). This occasion afforded us the opportunity to observe whether the specific type of housing affected the risk of cognitive disability. We found that people moving into government provided rental housing had the highest risk of cognitive decline. However, caution is warranted in inferring causality in the association between housing type and cognitive decline. The markedly high risk of cognitive decline for people moving into rental accommodation is based on a small number of individuals (n=31). In addition, we cannot reject the role of endogeneity in housing selection, e.g., cognitively frail individuals are more likely to have opted to move into rental accommodation – rather than opt for the purchase of a new home -- when the temporary trailer community was closed down.

These findings have statistically and clinically important implications. The effect size from destroyed housing (coefficient = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.22; model 2 in table 3) was comparable to new incident depressive symptoms (coefficient = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.13; model 2 in table 3).

There are also some plausible mechanisms linking housing damage in the aftermath of the disaster (and subsequently changed housing status) to the cognitive function of older people. Our mediation analysis (model 2) indicated that incident depressive symptoms and stroke, decreased frequency meeting with friends, interactions with neighbors, and daily walking time partially mediated those associations [7].

The findings from our mediation analysis suggest some potential interventions to improve cognitive resilience among disaster-affected older people. For example, promoting social participation may be effective for preserving cognitive function in the aftermath of a natural disaster [29] [30]. In a non-disaster context, we have previously found that promoting social participation through activities in community-based centers can be effective in maintaining cognitive function. In the town of Taketoyo (Aichi prefecture), we evaluated a community-based intervention in which community-based centers (called “salons” in Japan), were established where community-dwelling older seniors could congregate to engage in a variety of social programs and light physical activities. We demonstrated that participating in these community salons could prevent incident cognitive disabilities [31]. After the 2011 disaster, several local governments of affected municipalities have begun offering similar activities within the temporary housing communities. Researchers should assess the effect of participation in these community salon activities on older survivors’ cognitive function using longitudinal data.

A major strength of this study was the availability of information pre-dating the disaster about levels of cognitive disability as well as other health conditions. Our design was therefore able to effectively address the problem of recall bias that besets most studies conducted in post-disaster settings. Another strength of our study was the record linkage to medically verified cognitive disability obtained through home visits and medical examination.

A limitation of this study was the possibility of selection bias due to 59% response rate at baseline survey. Nonetheless, this response rate is quite comparable to similar surveys involving community-dwelling residents [8]. In addition, we confirmed that the demographic profile of our participants at baseline was quite similar to the rest of Iwanuma residents aged 65 years or older (eTable 2). Furthermore, the participation rates of our follow-up surveys were quite high (82.1% for wave 2, 84.6% for wave 3).

Supplementary Material

Funding sources.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG042463); Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI 15H01972, KAKENHI 23243070, KAKENHI 22390400, KAKENHI 22592327, and KAKENHI 24390469); a Health Labour Sciences Research Grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (H22-Choju-Shitei-008, H24-Choju-Wakate-009, H25-Choju-Ippan-003, and H28-Chouju-Ippan-002); and a grant from the Strategic Research Foundation Grant-Aided Project for Private Universities from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (S0991035).

Role of the Funder.

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations:

- FEMA

Federal Emergency Management Agency

- JAGES

Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study

- LTCI

Long-Term Care Insurance

- JPY

Japanese Yen

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. Authors declare no competing interests.

Financial disclosure. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Data and materials availability. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The JAGES data used in this study will be made available upon request, as per NIH data access policies. The authors require the applicant to submit an analysis proposal to be reviewed by an internal JAGES committee to avoid duplication. Confidentiality concerns prevent us from depositing our data in a public repository. Authors requesting access to the Iwanuma data need to contact the principal investigator of the parent cohort (K.K.) and the Iwanuma sub-study principal investigator (I.K.) in writing. Proposals submitted by outside investigators will be discussed during the monthly investigators’ meeting to ensure that there is no overlap with ongoing analyses. If approval to access the data is granted, the JAGES researchers will request the outside investigator to help financially support our data manager’s time to prepare the data for outside use.

Reference

- [1].Brunkard J, Namulanda G, Ratard R. Hurricane Katrina Deaths, Louisiana, 2005. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cabinet Office; Government of Japan. Annual Report on the Aging Society. Tokyo, Japan: Insatsu tsūhan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ishiki A, Furukawa K, Une K, Tomita N, Okinaga S, Arai H. Cognitive examination in older adults living in temporary apartments after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 2015;15:232–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Akanuma K, Nakamura K, Meguro K, Chiba M, Gutiérrez Ubeda SR, Kumai K, et al. Disturbed social recognition and impaired risk judgement in older residents with mild cognitive impairment after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011: the Tome Project. Psychogeriatrics. 2016;16:349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cherry KE, Su LJ, Welsh DA, Galea S, Jazwinski SM, Silva JL, et al. Cognitive and Psychosocial Consequences of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita Among Middle-Aged, Older, and Oldest-Old Adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS). Journal of applied social psychology. 2010;40:2463–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cherry KE, Brown JS, Marks LD, Galea S, Volaufova J, Lefante C, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Cognitive and Psychosocial Functioning After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Exploring Disaster Impact on Middle-Aged, Older, and Oldest-Old Adults. Journal of applied biobehavioral research. 2011;16:187–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hikichi H, Aida J, Kondo K, Tsuboya T, Matsuyama Y, Subramanian SV, et al. Increased risk of dementia in the aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:E6911–E8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Santos-Eggimann B, Cuénoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of Frailty in Middle-Aged and Older Community-Dwelling Europeans Living in 10 Countries. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2009;64:675–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Miyagi Prefectural Government. Current situations of damage and evacuation. [in Japanese]. 2017; https://www.pref.miyagi.jp/uploaded/attachment/625724.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2017.

- [10].Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, Reich MR, Ikegami N, Hashimoto H, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan’s long-term care insurance policy. The Lancet. 2011;378:1183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hisano S The relationship between Revised Hasegawa Dementia Scale (HDS-R), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Bed-fast Scale, and Dementia Scale. [in Japanese]. Japanese journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2009;20:883–91. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Meguro K, Tanaka N, Kasai M, Nakamura K, Ishikawa H, Nakatsuka M, et al. Prevalence of dementia and dementing diseases in the old-old population in Japan: the Kurihara Project. Implications for Long-Term Care Insurance data. Psychogeriatrics. 2012;12:226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Olivares-Tirado P, Tamiya N. Development of the Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan. Trends and Factors in Japan’s Long-Term Care Insurance System. Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. p. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hikichi H, Tsuboya T, Aida J, Matsuyama Y, Kondo K, Subramanian SV, et al. Social capital and cognitive decline in the aftermath of a natural disaster: a natural experiment from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2017;1:e105–e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Reitz C, Tang M, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. A summary risk score for the prediction of Alzheimer disease in elderly persons. Archives of Neurology. 2010;67:835–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sundström A, Westerlund O, Kotyrlo E. Marital status and risk of dementia: a nationwide population-based prospective study from Sweden. BMJ Open. 2016;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Subramaniam M, Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chua BY, Chua HC, et al. Prevalence of Dementia in People Aged 60 Years and Above: Results from the WiSE Study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015;45:1127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].North CS, Ringwalt CL, Downs D, Derzon J, Galvin D. Postdisaster course of alcohol use disorders in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Erskine N, Daley V, Stevenson S, Rhodes B, Beckert L. Smoking Prevalence Increases following Canterbury Earthquakes. The Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:596957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tsuboya T, Aida J, Hikichi H, Subramanian SV, Kondo K, Osaka K, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms following the Great East Japan earthquake: A prospective study. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;161:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Omama S, Yoshida Y, Ogasawara K, Ogawa A, Ishibashi Y, Nakamura M, et al. Influence of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami 2011 on Occurrence of Cerebrovascular Diseases in Iwate, Japan. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moscona JC, Peters MN, Maini R, Katigbak P, Deere B, Gonzales H, et al. The Incidence, Risk Factors, and Chronobiology of Acute Myocardial Infarction Ten Years After Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2018; doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.22:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yoshimura E, Ishikawa-Takata K, Murakami H, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Tsubota-Utsugi M, Miyachi M, et al. Relationships between social factors and physical activity among elderly survivors of the Great East Japan earthquake: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics. 2016;16:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Weintraub D, Oehlberg KA, Katz IR, Stern MB. Test characteristics of the 15-item geriatric depression scale and Hamilton depression rating scale in Parkinson disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:169–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Iwanuma City. Change of Population by Age Group and Sex. [in Japanese]. 2010; https://www.city.iwanuma.miyagi.jp/shisei/tokei/joho/documents/4nenreikakusaijinkousuii.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- [26].Iwanuma City. Population 15 Years of Age and Over, by Marital Status (4 Groups), Age (Five-Year Groups), Sex, and Averaged Age. [in Japanese]. 2010; https://www.city.iwanuma.miyagi.jp/shisei/tokei/joho/documents/7haiguukankeidanjobetsujinkou.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2017.

- [27].Iwanuma City. Population and Employed Persons 15 Years and Older, based on Place of Usual Residence and Place of Working or Schooling, by Age (Five-Year Groups) and Sex. [in Japanese]. 2010; https://www.city.iwanuma.miyagi.jp/shisei/tokei/joho/documents/23joujuuchimatahajuugyouchinojinnkou.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- [28].Hikichi H, Sawada Y, Tsuboya T, Aida J, Kondo K, Koyama S, et al. Residential relocation and change in social capital: A natural experiment from the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Science Advances. 2017;3:e1700426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Glei DA, Landau DA, Goldman N, Chuang YL, Rodríguez G, Weinstein M. Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: an analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. International journal of epidemiology. 2005;34:864–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang H-X, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late-Life Engagement in Social and Leisure Activities Is Associated with a Decreased Risk of Dementia: A Longitudinal Study from the Kungsholmen Project. American journal of epidemiology. 2002;155:1081–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hikichi H, Kondo K, Takeda T, Kawachi I. Social interaction and cognitive decline: Results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017;3:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.