Abstract

3-methylglutaconic (3MGC) aciduria occurs in numerous inborn errors associated with compromised mitochondrial energy metabolism. In these disorders, 3MGC CoA is produced de novo from acetyl CoA in three steps with the final reaction catalyzed by 3MGC CoA hydratase (AUH). In in vitro assays, whereas recombinant AUH dehydrated 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG) CoA to 3MGC CoA, free CoA was also produced. Although HMG CoA is known to undergo non-enzymatic intramolecular cyclization, forming HMG anhydride and free CoA, the amount of free CoA generated increased when AUH was present. To test the hypothesis that the AUH-dependent increase in CoA production is caused by intramolecular cyclization of 3MGC CoA, gas chromatography – mass spectrometry analysis of organic acids was performed. In the absence of AUH, HMG CoA was converted to HMG acid while, in the presence of AUH, 3MGC acid was also detected. To determine which 3MGC acid diastereomer was formed, immunoblot assays were conducted with 3MGCylated BSA. In competition experiments, when α−3MGC IgG was pre-incubated with trans-3MGC acid or cis-3MGC acid, the cis diastereomer inhibited antibody binding to 3MGCylated BSA. When an AUH assay product mix served as competitor, α−3MGC IgG binding to 3MGCylated BSA was also inhibited, indicating cis-3MGC acid is produced in incubations of AUH and HMG CoA. Thus, non-enzymatic isomerization of trans-3MGC CoA drives AUH-dependent HMG CoA dehydration and explains the occurrence of cis-3MGC acid in urine of subjects with 3MGC aciduria. Furthermore, the ability of cis-3MGC anhydride to non-enzymatically acylate protein substrates may have deleterious pathophysiological consequences.

Keywords: 3-methylglutaconyl CoA, AUH hydratase, intramolecular cyclization, inborn error of metabolism, acetyl CoA diversion pathway

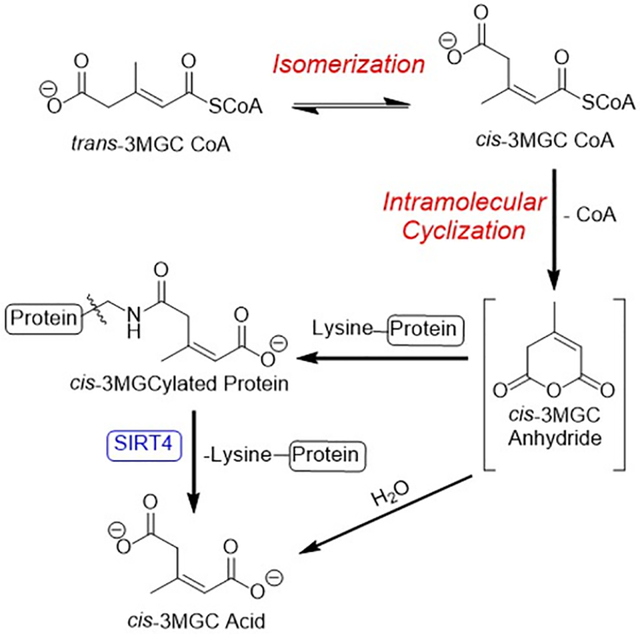

Graphical Abstract

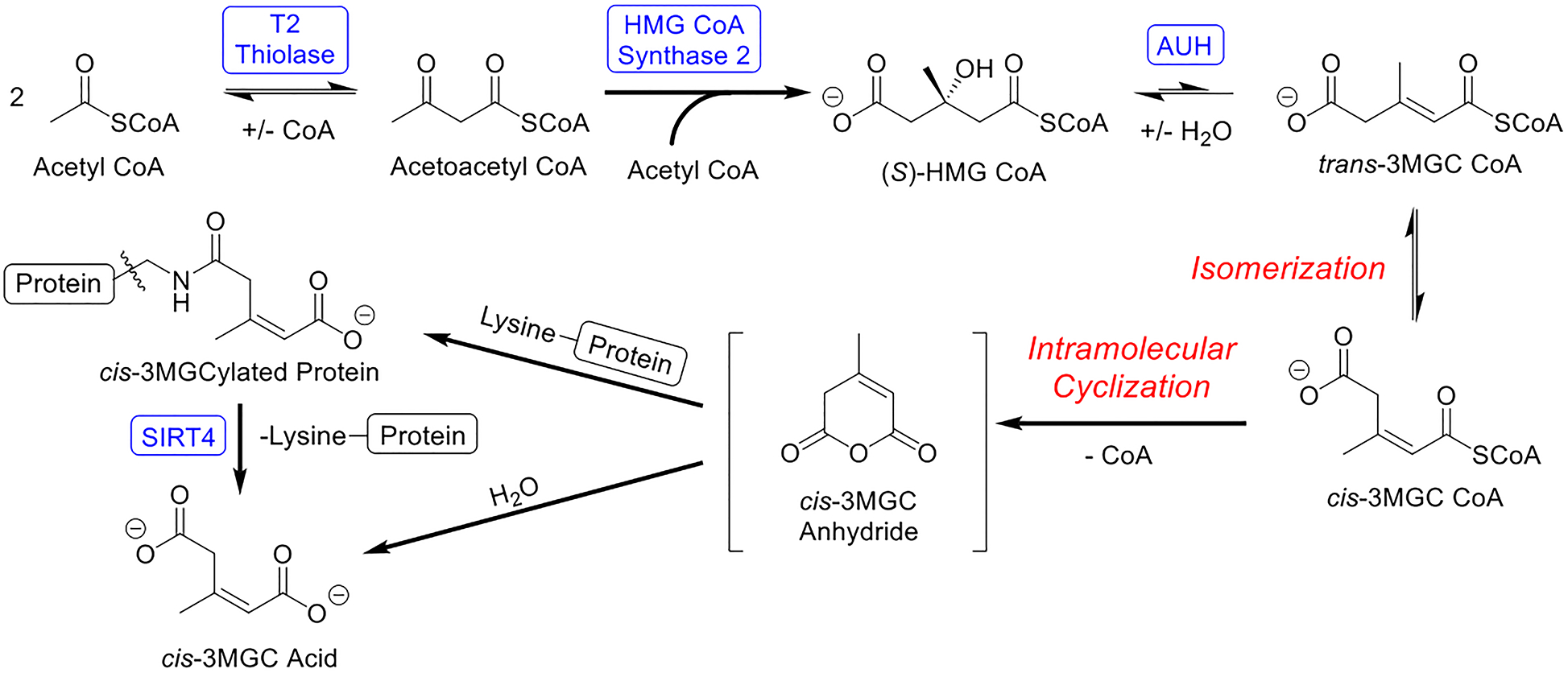

In various inborn errors of metabolism, acetyl CoA is enzymatically converted to trans-3-methylglutaconyl (3MGC) CoA, via acetoacetyl CoA (T2) thiolase, HMG CoA synthase 2 and 3MGC CoA hydratase (AUH). Subsequently, trans-3MGC CoA undergoes non-enzymatic chemical reactions, including isomerization and intramolecular cyclization to form cis-3MGC anhydride. Once formed, cis-3MGC anhydride has two possible fates, a) hydrolysis to cis-3MGC acid or b) protein 3MGCylation. 3MGCylated proteins are substrates for SIRT4 mediated diacylation.

Introduction

3-methylglutaconic (3MGC) aciduria is a distinctive phenotypic feature of a growing number of inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) that affect mitochondrial energy metabolism [1,2]. Investigations have revealed that two types of 3MGC aciduria exist, primary and secondary. Primary 3MGC aciduria is caused by deficiencies in either of two leucine catabolism pathway enzymes, 3-methylglutaconyl CoA hydratase (AUH) or 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA lyase (HMGCL) [3]. In this case, as leucine is catabolized, pathway intermediates upstream of the deficient enzyme accumulate. Ultimately, these intermediates are converted to organic acids and excreted in urine. IEMs that affect AUH or HMGCL activity result in the excretion of large amounts of 3MGC acid [1,4], with excretion levels increasing upon leucine loading [5].

All remaining IEMs that manifest this phenotypic feature are referred to as secondary 3MGC acidurias. In these disorders, no deficiencies exist in leucine catabolism pathway enzymes. Instead, 3MGC aciduria occurs when discrete IEMs induce defects in mitochondrial energy metabolism [2]. Thus, rather than arising from leucine, trans-3MGC CoA is synthesized de novo from acetyl CoA, via an aberrant metabolic pathway termed the “acetyl CoA diversion pathway” [3]. This pathway is initiated when the IEM affects 1) cristae membrane structure [6]; 2) components of the electron transport chain (ETC) [7] or 3) ATP synthase (8). When these structures / processes are disrupted in cardiac, skeletal muscle or brain tissue mitochondria, the ETC’s capacity to oxidize reduced cofactors (i.e. NADH and FADH2) generated during oxidative fuel metabolism is reduced. Subsequently, NADH levels rise in the matrix space, resulting in inhibition of enzymes that generate NADH as a product, including three TCA cycle enzymes [2]. Inhibition of TCA cycle activity leads to increased matrix levels of acetyl CoA and, under these circumstances, acetyl CoA becomes a substrate for acetoacetyl CoA thiolase (T2 thiolase). This enzyme functions in reverse of its usual direction, condensing two equivalents of acetyl CoA to yield acetoacetyl CoA. A second condensation reaction, catalyzed by HMG CoA synthase 2, converts acetoacetyl CoA and acetyl CoA into HMG CoA. AUH then dehydrates HMG CoA, forming trans-3MGC CoA. Once formed via this route, trans-3MGC CoA cannot proceed further up the leucine degradation pathway because the reaction catalyzed by the next enzyme, 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase, is unidirectional.

The concept that trans-3MGC CoA formed via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway simply accumulates until it becomes a substrate for acyl CoA thioesterase-mediated CoA hydrolysis [9,10] is not consistent with other observations. First, the equilibrium constant for the reaction catalyzed by AUH favors HMG CoA over trans-3MGC CoA by a factor of ~20 [11]. Indeed, during leucine catabolism, as trans-3MGC CoA is formed, it is rapidly and efficiently hydrated to HMG CoA. When produced via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway, it is anticipated that HMG CoA would be favored over trans-3MGC CoA due to the equilibrium constant of this reversible hydration / dehydration reaction. Second, 3MGC acid recovered in urine of subjects with primary 3MGC aciduria is present as a ~2:1 mixture of cis- and trans- diastereomers, respectively [12,13]. Jones et al [4] recently reported that, although trans-3MGC acid isomerization occurs as a function of time and temperature, the rate of this reaction at 37 °C is far too slow to account for the cis:trans ratio observed in urine of subjects with 3MGC aciduria.

To investigate this further, AUH activity assays have been performed in vitro using HMG CoA as substrate. The results obtained provide experimental evidence that, at physiological temperature, as trans-3MGC CoA is formed via AUH-catalyzed dehydration of HMG CoA, it isomerizes to cis-3MGC CoA. This terminally carboxylated acyl CoA then undergoes intramolecular cyclization, forming cis-3MGC anhydride and free CoA. Subsequently, cis-3MGC anhydride can either be hydrolyzed to generate cis-3MGC acid or it can react with lysine side chain amino groups to 3MGCylate proteins [15]. This non-enzymatic reaction sequence alters the AUH substrate / product equilibrium and, thereby, induces further depletion of the HMG CoA pool. Thus, the acetyl CoA diversion pathway, which redirects acetyl CoA away from oxidative metabolism toward the organic acid waste product, 3MGC acid, is driven by an isomerization-dependent molecular sink created by three non-enzymatic chemical reactions.

Results

AUH-mediated dehydration of HMG CoA to trans-3MGC CoA

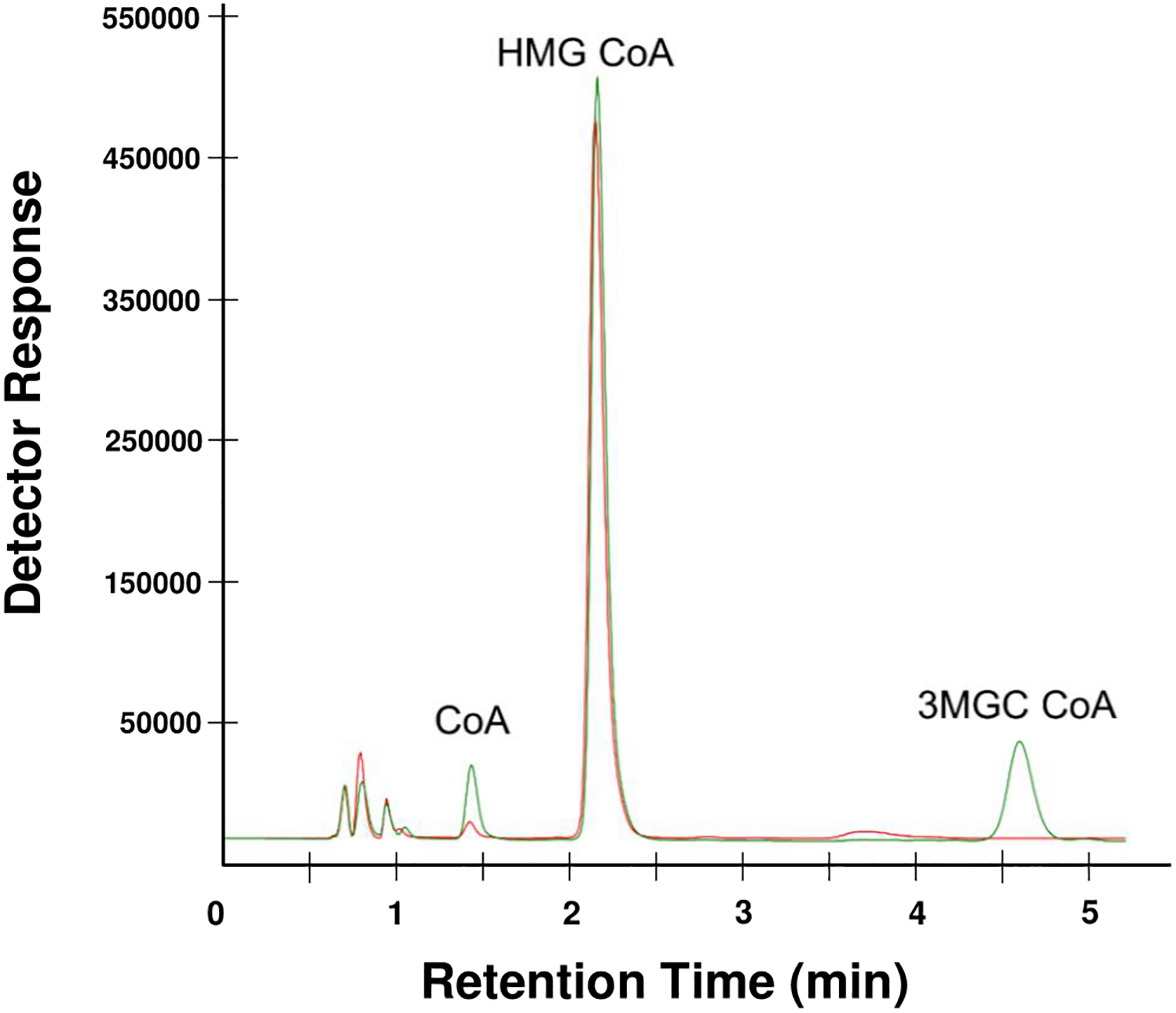

HMG CoA was incubated in the absence and presence of AUH for 1 h at 25 °C followed by reversed phase HPLC analysis of the reaction products (Figure 1). In incubations without AUH, a single major peak corresponding to HMG CoA was detected. When AUH was included, a new peak corresponding to the expected reaction product, trans-3MGC CoA, appeared. The observed ratio of HMG CoA:trans-3MGC CoA is consistent with the fact that this reversible dehydration / hydration reaction strongly favors the hydrated product [11]. In assays containing AUH, in addition to trans-3MGC CoA, a peak corresponding to free CoA increased as well.

Figure 1. Reversed phase HPLC of AUH reaction products.

HMG CoA was incubated with (green line) or without AUH (red line) for 1 h at 25 °C and, following incubation, the reaction products were analyzed by HPLC. A representative chromatogram is shown. Peaks were identified by comparison with standards.

Effect of incubation time and temperature on AUH reaction product formation

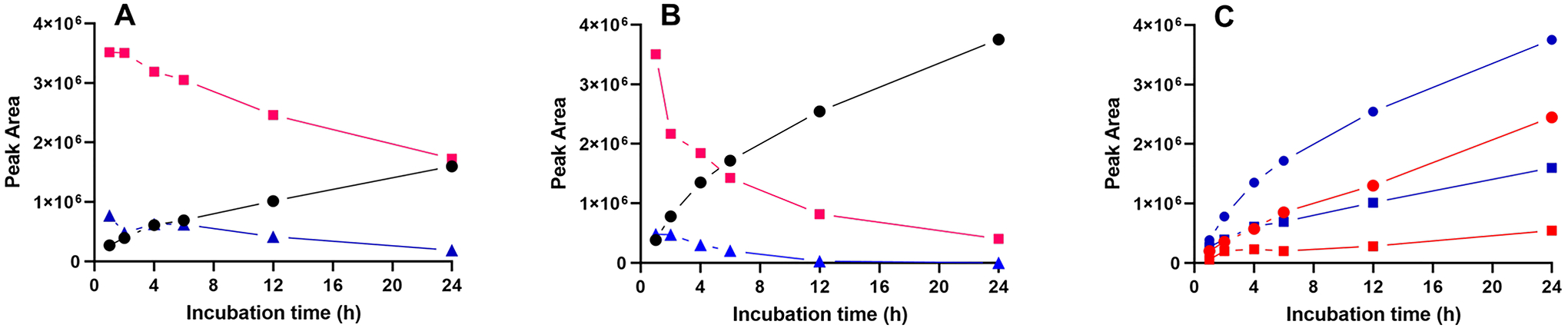

To determine the effect of assay time on the products formed, HMG CoA was incubated with AUH for 1, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h at 25 °C, followed by reversed phase HPLC analysis of the products formed. The results obtained (Figure 2A) indicate that, at time points beyond 1 h, the amounts of both HMG CoA and trans-3MGC CoA declined as a function of incubation time. By contrast, a steady increase in the peak corresponding to free CoA was observed. The same experiment was then conducted at 37 °C. Compared to results obtained at 25 °C, a more pronounced time-dependent decline in HMG CoA levels was noted (Figure 2B). Once again, the decline in HMG CoA did not lead to a corresponding increase in trans-3MGC CoA product formation. Rather, under these conditions, trans-3MGC CoA levels remained comparatively low at early time points (e.g. 1 h) and declined further over time. At 12 h and beyond, trans-3MGC CoA was undetectable by HPLC. As the peaks for HMG CoA and trans-3MGC CoA were declining, the peak corresponding to free CoA steadily increased. The large accumulation of free CoA in assays containing only HMG CoA and AUH prompted an examination of this reaction in greater detail.

Figure 2. Effect of reaction time and temperature on AUH reaction products.

Panel A) AUH was incubated with HMG CoA at 25 °C for specified times and, following incubation, aliquots were subjected to reversed phase HPLC. Panel B) same as in Panel A, except that the incubation temperature was 37 °C. Red line, square symbols) HMG CoA; Blue line, triangles) 3MGC CoA; Black line, circles) free CoA. Panel C) Effect of AUH on the formation of free CoA from HMG CoA. HMG CoA was incubated in the absence and presence of AUH for specified times at 25 °C or 37 °C. Following incubation, sample aliquots were subjected to HPLC and the peak corresponding free CoA measured. Red line with square symbols) HMG CoA incubated at 25 °C; Blue line with squares) HMG CoA plus AUH incubated at 25 °C; Red line with circles) HMG CoA incubated at 37 °C; Blue line with circles) HMG CoA plus AUH incubated at 37 °C.

Effect of AUH on the production of free CoA from HMG CoA

HMG CoA was incubated for specified times in the absence and presence of AUH at 25 °C and 37 °C and the amount of free CoA generated was measured by reversed phase HPLC. Whereas little or no free CoA was present when HMG CoA was incubated for 1 h at 25 °C (Figure 2C), increased amounts of free CoA appeared at longer time points. When incubations of HMG CoA included AUH, the time-dependent increase in free CoA generation was greater than that observed in incubations lacking AUH. A similar trend in CoA formation was observed in incubations conducted at 37 °C, with even greater amounts of CoA produced. Thus, three factors appear to modulate the amount of free CoA generated in these incubations: temperature, time and the presence / absence of AUH.

In the absence of AUH, it has been reported that HMG CoA undergoes non-enzymatic intramolecular cyclization, forming free CoA and cyclic HMG anhydride [15]. When AUH is present, additional free CoA would be generated if the reaction product, trans-3MGC CoA, also undergoes intramolecular cyclization. In contrast to HMG CoA, however, trans-3MGC CoA is sterically incapable of undergoing intramolecular cyclization to yield free CoA. To investigate this further, organic acid analysis of the reaction products was performed.

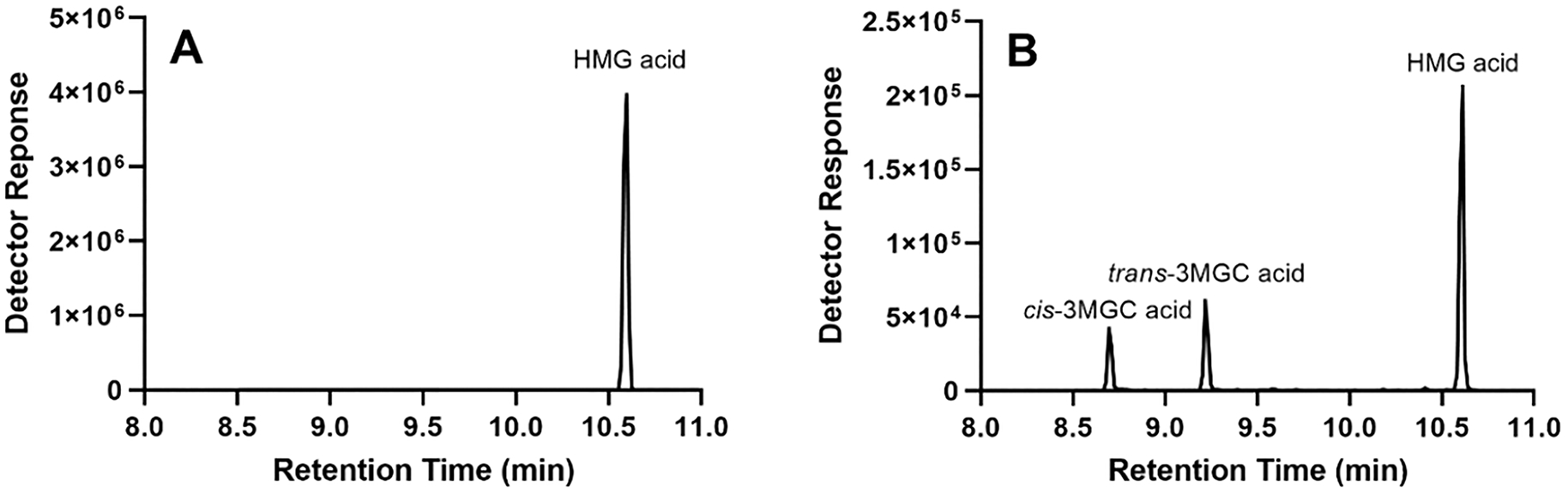

Organic acid analysis of AUH reaction products

HMG CoA was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the absence and presence of AUH. Following incubation, reaction products were acidified, extracted with ethyl acetate, silylated and analyzed by GC-MS. When a control, non-incubated, sample of HMG CoA was subjected to the same procedure, no HMG acid peak was detected (data not shown). When HMG CoA alone was incubated prior to GC-MS, a peak identified as HMG acid was observed (Figure 3A). This result provides evidence of intramolecular cyclization since non-enzymatic hydrolysis of HMG anhydride yields HMG acid. In incubations containing HMG CoA and AUH, GC-MS analysis of the reaction products revealed the peak for HMG acid as well as two additional peaks, corresponding to cis- and trans-3MGC acid, respectively (Figure 3B). Insofar as isomerization of 3MGC acid diastereomers occurs during derivatization and / or GC [14], assignment of which diastereomer was produced in incubations of HMG CoA and AUH is not possible using this method. However, given that steric constraints prevent trans-3MGC CoA from undergoing intramolecular cyclization, the data suggest that, after trans-3MGC CoA is formed by AUH-mediated dehydration of HMG CoA, it isomerizes to cis-3MGC CoA, which then undergoes intramolecular cyclization, generating cis-3MGC anhydride and free CoA. Subsequent non-enzymatic hydrolysis of cis-3MGC anhydride produces cis-3MGC acid, which is detected as a mixture of cis and trans diastereomers by GC-MS.

Figure 3. AUH-dependent production of 3MGC acid from HMG CoA.

HMG CoA was incubated in the absence (panel A) and presence (panel B) of AUH for 4 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the sample was extracted, derivatized and analyzed by GC-MS.

AUH-dependent 3MGCylation of BSA

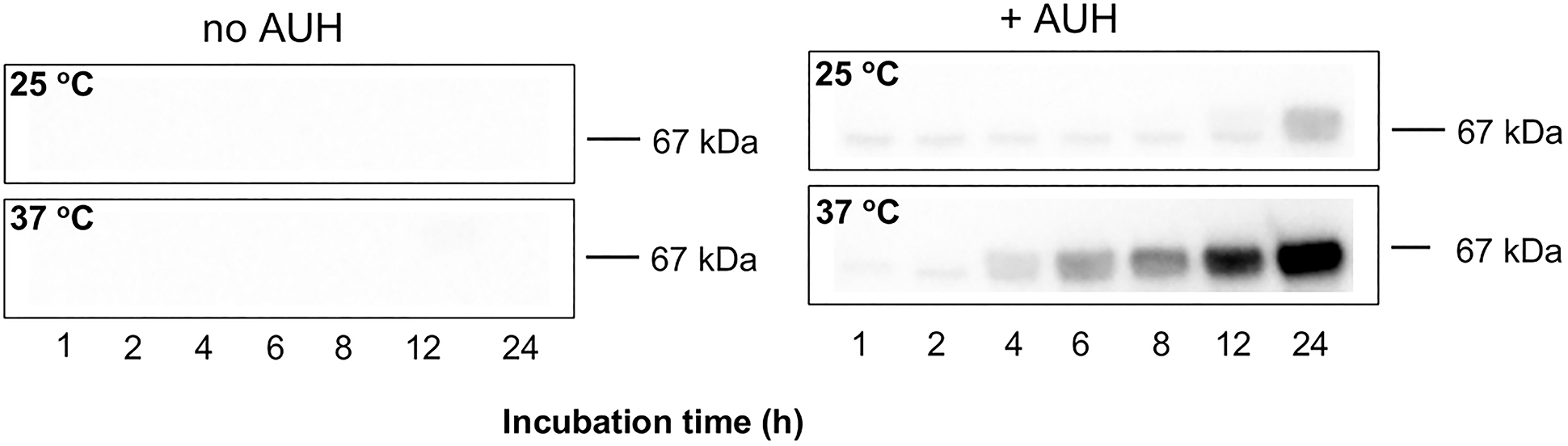

In addition to hydrolysis to the corresponding organic acid, cyclic anhydrides formed by intramolecular cyclization can non-enzymatically acylate protein lysine side chain amino groups [15]. To assess whether trans-3MGC CoA generated upon incubation of AUH with HMG CoA is able to 3MGCylate BSA, an immunoblot assay was employed. Key to this assay is the availability of an isolated rabbit polyclonal antibody (α−3MGC IgG) that specifically recognizes 3MGC moieties [16]. When HMG CoA was incubated with BSA at 25 °C or 37 °C, no evidence of 3MGCylated BSA was obtained (Figure 4). By contrast, when AUH was present in incubations of HMG CoA and BSA, time- and temperature-dependent BSA 3MGCylation was detected. This result provides support for the concept that, as HMG CoA is dehydrated to trans-3MGC CoA by AUH, it isomerizes to cis-3MGC CoA, which undergoes intramolecular cyclization to form cis-3MGC anhydride and CoA. Once formed, cis-3MGC anhydride acylates lysine side chain amino groups on BSA and this reaction is detected by probing BSA immunoblots with α−3MGC IgG.

Figure 4. Effect of time, temperature and AUH on 3MGCylation of BSA.

HMG CoA and BSA were incubated in the absence and presence of AUH at specified temperatures, as described in Materials and Methods. At the indicated times, aliquots of the reaction were removed and subjected to immunoblot analysis. The blot was probed with α−3MGC IgG (1:40,000) and detected with HRP conjugated secondary antibody.

Effect of protein on the fate of cis-3MGC anhydride.

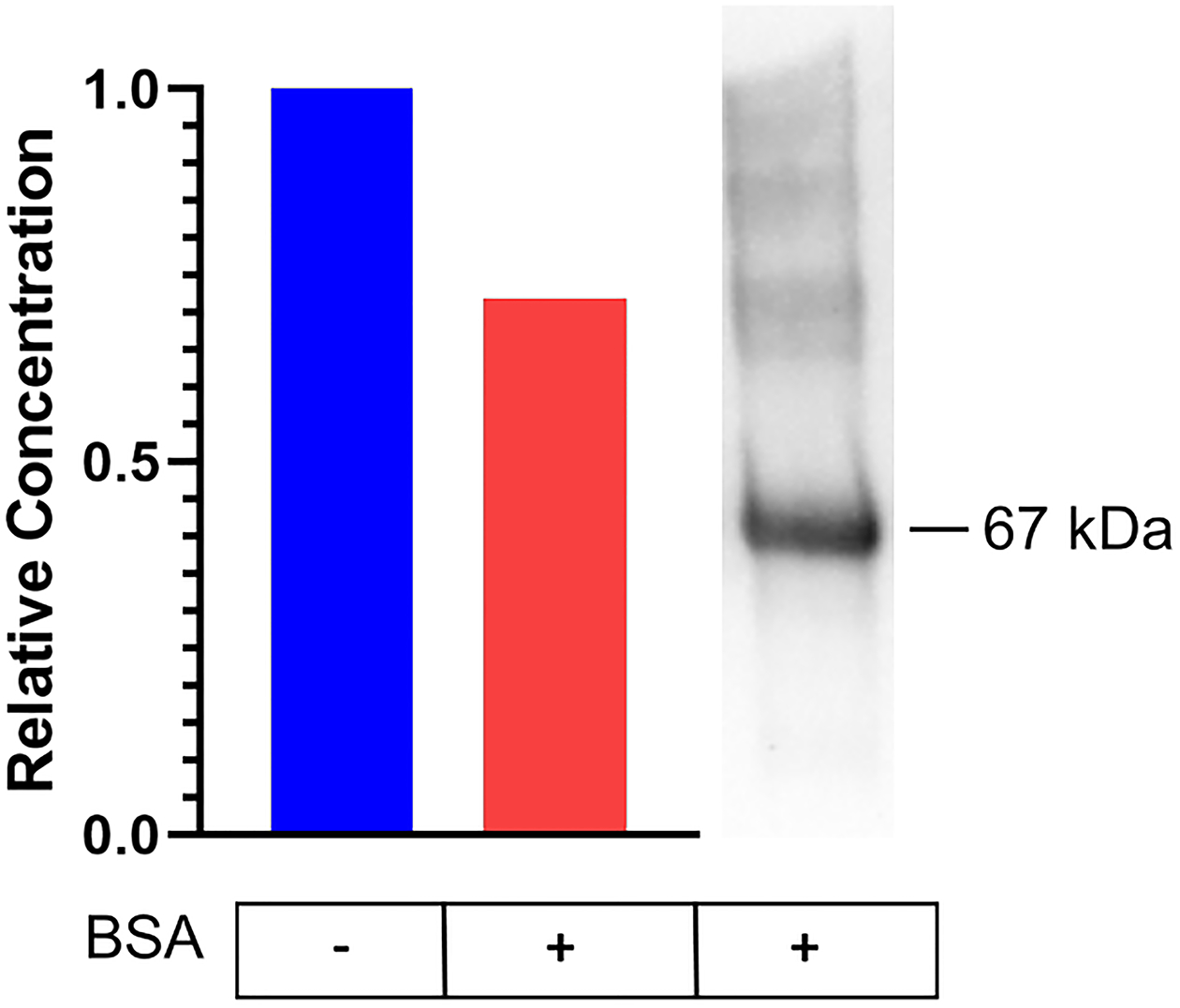

Data presented above indicate that, once formed, cis-3MGC anhydride has two possible fates: hydrolysis to form cis-3MGC acid or protein 3MGCylation. To estimate the relative proportion of these two products, equimolar amounts of cis-3MGC anhydride were incubated in the absence and presence of BSA. Following incubation, the samples were spin filtered to obtain retentate and filtrate fractions. The amount of cis-3MGC acid present in each filtrate was determined by 1H-NMR spectroscopy by comparison to an internal standard. The results indicate a 28 % reduction in cis-3MGC acid content in the filtrate that was incubated with BSA (Figure 5). When an aliquot of the incubation containing BSA was subjected to α−3MGC IgG immunoblot analysis, evidence of BSA 3MGCylation was obtained. Thus, it may be concluded that, under these conditions, the major fate of cis-3MGC anhydride is hydrolysis to yield cis-3MGC acid.

Figure 5. Fate of cis-3MGC anhydride.

cis-3MGC anhydride (10 μg) was incubated in the absence and presence of 0.5 mg / ml BSA for 1 h and, following incubation and filtration to remove BSA, the amount of cis-3MGC acid present was determined by 400 MHz 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Panel A) Left; histogram depicting the effect of BSA on the relative concentration of cis-3MGC acid produced and Right; α−3MGC IgG immunoblot analysis of an aliquot of the sample incubated with BSA.

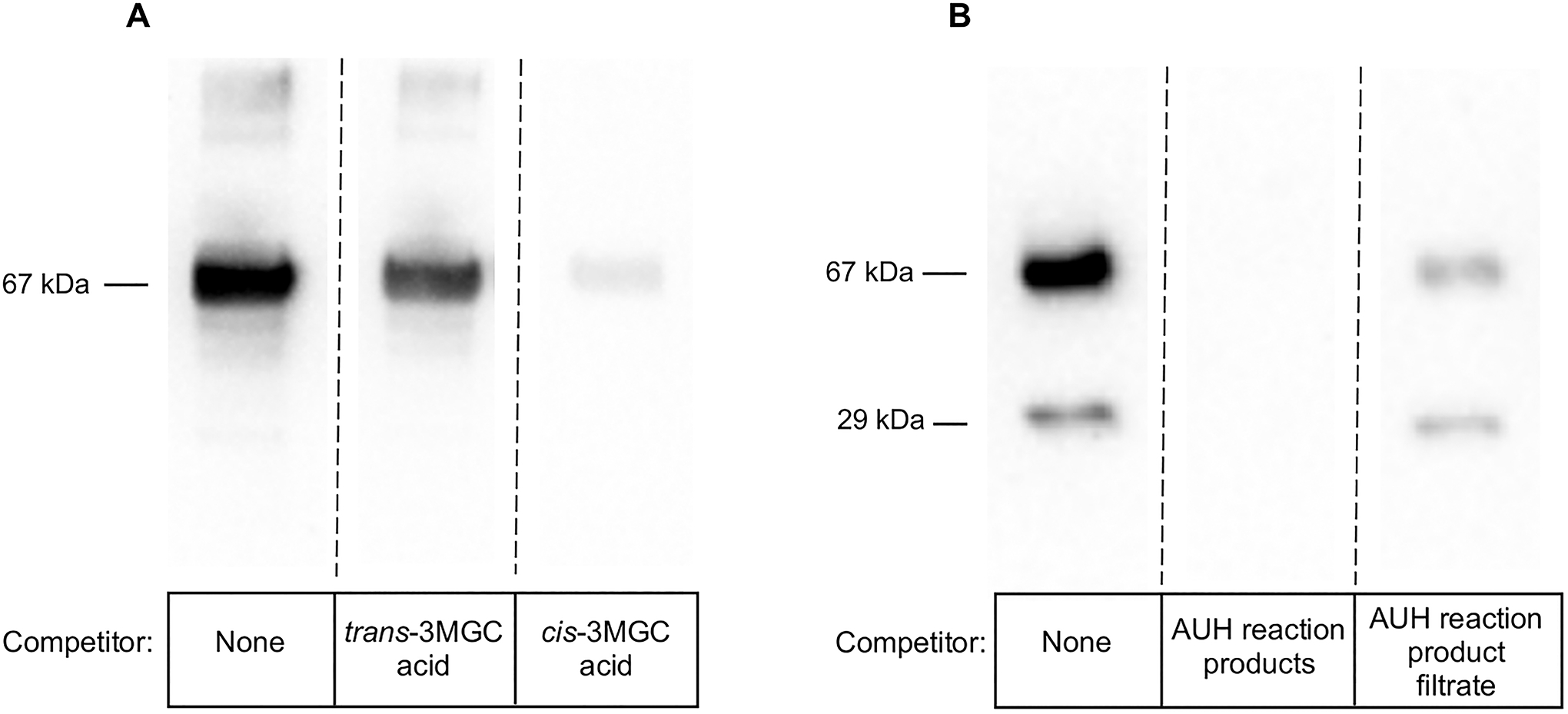

Competition binding experiments

Previous studies revealed that α−3MGC IgG displays an approximate 10-fold binding preference for cis-3MGC acid over trans-3MGC acid [16]. To determine if cis-3MGC acid is generated in incubations of AUH and HMG CoA, competition binding assays were performed. In this assay, 3MGCylated BSA was prepared, and identical aliquots applied to the lanes of an SDS-PAGE gel and, following electrophoresis, transferred to a PVDF membrane. Prior to probing individual lanes by immunoblot, aliquots of α−3MGC IgG were pre-incubated in buffer alone, buffer containing trans-3MGC acid, cis-3MGC acid or the products formed in an AUH enzyme assay. Following this pre-incubation, the antibody-containing solutions were used to probe 3MGCylated BSA by immunoblot. In the absence of competitor, as expected, α−3MGC IgG detected 3MGCylated BSA (Figure 6A). When α−3MGC IgG was pre-incubated with trans-3MGC acid, antibody binding to 3MGCylated BSA was slightly decreased. By contrast, when α−3MGC IgG was pre-incubated with cis-3MGC acid, antibody binding to 3MGCylated BSA was strongly attenuated. Thus, the 3MGC moiety of 3MGCylated BSA is present in the cis configuration. When α−3MGC IgG was pre-incubated with the products of an AUH activity assay, α−3MGC IgG binding to 3MGCylated BSA was abolished (Figure 6B). To exclude the possibility that 3MGCylated AUH, generated during the assay, contributed to the observed competition, an AUH assay product mix was spin filtered to remove protein. When the filtrate was incubated with α−3MGC IgG prior to probing a 3MGCylated BSA immunoblot, signal attenuation was observed, although the extent of attenuation was less than that detected with the complete AUH assay product mix. Based on these results, we conclude that the cis diastereomer of 3MGC acid is produced in AUH assays with HMG CoA as substrate.

Figure 6. Effect of competitors on α−3MGC IgG detection of 3MGCylated BSA.

Panel A) Identical aliquots of 3MGCylated BSA, generated as described previously [16], were applied to lanes of a single SDS-PAGE gel. Following electrophoretic transfer of the gel contents to a PVDF membrane, individual lanes were excised and probed separately with the following antibody preparations: α−3MGC IgG (no competitor control), α−3MGC IgG pre-incubated with trans-3MGC acid and α−3MGC IgG pre-incubated with cis-3MGC acid. Antibody pre-incubations were conducted at 4 °C for 16 h. To generate the figure panel, an “intact” gel was reconstructed from individual immunoblot slices (demarcated by splice marks). Panel B) 3MGCylated BSA was generated by incubating HMG CoA and AUH with BSA (see Figure 4 legend). Identical aliquots of the reaction product were applied to lanes of a single SDS-PAGE gel. Following electrophoretic transfer of the gel contents to a PVDF membrane, individual lanes were excised and probed separately with the following antibody preparations: α−3MGC IgG (no competitor control), α−3MGC IgG pre-incubated with the products obtained following incubation of HMG CoA and AUH for 5 h at 37 °C, and α−3MGC IgG pre-incubated with the filtrate (10 kDa MW cutoff) obtained from the incubation of HMG CoA and AUH for 5 h at 37 °C. α−3MGC IgG pre-incubations were conducted at 4 °C for 16 h. To generate the final figure panel, an “intact” gel was reconstructed from individual immunoblot slices (demarcated by splice marks).

Discussion

In human intermediary metabolism, the unsaturated short-chain acyl CoA, trans-3MGC CoA, is found only in the leucine degradation pathway. During leucine catabolism in mitochondria, following transamination, CoA thioesterification and dehydrogenation, the unsaturated intermediate, 3-methylcrotonyl CoA, is carboxylated by 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase to form trans-3MGC CoA [17]. Normally, trans-3MGC CoA is rapidly hydrated by AUH to form HMG CoA, which is then converted to acetoacetate and acetyl CoA by HMGCL. In cardiac and skeletal muscle tissue, acetoacetate is further metabolized to acetoacetyl CoA by succinyl CoA-O-acyltransferase and cleaved by T2 thiolase, yielding two equivalents of acetyl CoA. In these tissues, the predominant fate of acetyl CoA is oxidation to CO2 via the TCA cycle. However, in a growing number of IEMs characterized by compromised mitochondrial energy metabolism, abnormal amounts of 3MGC acid are excreted in urine [1]. In these IEMs, collectively referred to as secondary 3MGC acidurias, no defects in leucine catabolism enzymes exist. This has led to the proposal that, in these disorders, 3MGC acid arises de novo via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway [2,3].

Whereas the acetyl CoA diversion pathway provides a coherent explanation of IEM-induced aberrant acetyl CoA metabolism, several questions remain to be addressed, including a) how does AUH overcome an equilibrium constant that strongly favors the hydrated state (HMG CoA) over the dehydrated state (trans-3MGC CoA) [11]; b) how is 3MGC acid generated from trans-3MGC CoA; and c) what is the molecular basis for the prevalence of cis-3MGC acid in 3MGC aciduria?

The observation that inclusion of AUH in incubations of HMG CoA increases free CoA production implies that the AUH reaction product, trans-3MGC CoA, also reacts to produce free CoA. Unlike HMG CoA, however, trans-3MGC CoA cannot undergo intramolecular cyclization due to steric constraints imposed by the trans alkene. Despite this fact, indirect evidence exists that this reaction occurs in vivo [15]. This discrepancy can be explained if trans-3MGC CoA isomerizes to cis-3MGC CoA, since intramolecular cyclization of the cis diastereomer is not sterically prohibited. If cis-3MGC CoA is generated, and undergoes intramolecular cyclization, cis-3MGC anhydride and free CoA are the anticipated products. If so, the anhydride has two possible fates: a) hydrolysis to form cis-3MGC acid; or b) 3MGCylation of protein lysine side chain amino groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Diagram depicting enzyme-mediated and non-enzymatic reactions in the acetyl CoA diversion pathway.

Initially, acetyl CoA is enzymatically converted to trans-3MGC CoA in three steps, catalyzed by T2 thiolase, HMG CoA synthase 2 and AUH. Subsequently, trans-3MGC CoA undergoes 3 non-enzymatic chemical reactions, including isomerization to cis-3MGC CoA and intramolecular cyclization to form cis-3MGC anhydride. Once formed cyclic cis-3MGC anhydride has two possible fates, a) non enzymatic hydrolysis to cis-3MGC acid or b) protein 3MGCylation. In the latter case, 3MGCylated proteins serve as a substrate for sirtuin 4 mediated deacylation, generating cis-3MGC acid as product.

Evidence presented herein revealed that incubations containing AUH and HMG CoA produce cis-3MGC acid, as well as cis-3MGCylated protein. Thus, isomerization of trans-3MGC CoA to cis-3MGC CoA precedes intramolecular cyclization of cis-3MGC CoA to form cyclic cis-3MGC anhydride. By extension, it may be concluded that these sequential non-enzymatic reactions serve to deplete the pool of trans-3MGC CoA produced in incubations of AUH and HMG CoA. As trans-3MGC CoA isomerizes and cyclizes, in order to re-establish the substrate / product equilibrium, more HMG CoA is subject to dehydration by AUH. In essence, this reaction sequence constitutes a molecular sink that facilitates AUH-catalyzed dehydration of HMG CoA through irreversible, non-enzymatic conversion of the reaction product, trans-3MGC CoA, to cis-3MGC anhydride and free CoA.

This non-enzymatic reaction sequence also provides an explanation for the excretion of cis-3MGC acid in 3MGC aciduria [12,13]. As mentioned above, once cis-3MGC anhydride is generated, it can either be hydrolyzed to cis-3MGC acid or it can acylate protein lysine side chains. Evidence that the latter reaction occurs in vivo was reported by Wagner et al [15] in a murine model of HMGCL deficiency. Subsequently, Anderson et al [18] reported that 3MGCylated proteins are substrates for deacylation by sirtuin 4 (SIRT4) [19]. In this NAD+-dependent reaction, the expected product is cis-3MGC acid [20]. Thus, whether generated directly by hydrolysis of cis-3MGC anhydride or by SIRT4-mediated deacylation of 3MGCylated proteins, trans-3MGC CoA formed via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway is destined to generate cis-3MGC acid, which is excreted in urine as a waste product. As shown by Jones et al [14], cis-3MGC acid largely resists isomerization to trans-3MGC acid under physiological conditions. Thus, once it is formed in vivo, cis-3MGC acid is excreted in urine as an organic acid waste product. A key experimental tool used to decipher the reaction sequence involved in cis-3MGC acid formation via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway is the α−3MGC IgG previously reported by Young et al [16]. This antibody was employed in immunoblot experiments to detect 3MGCylated BSA formation as a function of time, temperature and the presence / absence of AUH. Importantly, competition binding experiments revealed that the cis diastereomer of 3MGC acid is generated in AUH incubations with HMG CoA.

In an earlier study of AUH, Mack et al [11] noted the unexpected occurrence of free CoA in incubations of trans-3MGC CoA with AUH. These authors proposed that, in addition to enoyl CoA hydratase activity, AUH possesses an intrinsic acyl CoA hydrolase (i.e. thioesterase) activity, capable of converting trans-3MGC CoA to 3MGC acid and free CoA. Based on results presented herein, it is most likely these authors observed the effects of non-enzymatic isomerization / intramolecular cyclization as a competing reaction in their assays. Support for this interpretation includes the finding that, when trans-3MGC CoA, generated in vitro via 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase-catalyzed carboxylation of 3-methylcrotonyl CoA, was incubated with BSA, 3MGCylated BSA was detected [16]. In this case, despite never being exposed to AUH, trans-3MGC CoA was still converted to cis-3MGC anhydride and free CoA.

It is curious that subjects with primary 3MGC aciduria manifest a ~2:1 cis:trans ratio of 3MGC acid while, in subjects with secondary 3MGC aciduria, the ratio is closer to 1:1 [1]. Whereas the present results provide a plausible explanation for the occurrence of cis-3MGC acid in both cases, the molecular basis for the differential cis:trans ratio in primary versus secondary 3MGC aciduria has yet to be elucidated. The fact that trans-3MGC acid is observed in both primary and secondary 3MGC aciduria indicates the pathway involving non-enzymatic isomerization / intramolecular cyclization / hydrolysis to yield cis-3MGC acid is not the only route employed. Evidence reported by Jones et al [14], however, indicates that, once formed, neither cis- nor trans-3MGC acid isomerizes at physiological temperatures on a time scale that would affect the ratio of these acids recovered in urine. On the other hand, if trans-3MGC CoA serves as a substrate for a member of the acyl CoA thioesterase (ACOT) enzyme family, the ratio could be impacted. Cells possess at least 15 distinct ACOTs [21] that display distinct tissue expression / subcellular localization patterns and substrate specificities. For example, ACOT9 localizes to mitochondria, is expressed in numerous tissues and displays thioesterase activity with the terminally carboxylated substrate, glutaryl CoA [22]. Thus, ACOT9 may be capable of hydrolyzing trans-3MGC CoA. However, ACOT9 specificity toward trans-3MGC CoA as substrate has not been reported. In any case, it may be anticipated that trans-3MGC CoA is not the primary substrate for the responsible ACOT, such that the efficiency with which trans-3MGC CoA is hydrolyzed may be relatively low, especially if competition exists with other potential substrates. Based on the finding that ACOT9 has been shown to hydrolyze 3-hydroxyisovaleryl (3HIV) CoA [22], this enzyme appears to be responsible for the elevated levels of 3HIV acid observed in primary 3MGC aciduria [23]. By contrast, 3HIV acid levels are normal in secondary 3MGC aciduria. Thus, in primary 3MGC aciduria, if 3HIV CoA accumulation affects ACOT9 substrate utilization efficiency, it is conceivable that a greater proportion of the trans-3MGC CoA pool will undergo non-enzymatic isomerization / intramolecular cyclization / hydrolysis to yield cis-3MGC acid. In secondary 3MGC aciduria, this won’t occur because 3HIV CoA does not accumulate as a potential ACOT substrate. Future studies using mouse models of primary and secondary 3MGC aciduria may shed light on this issue.

Returning to the in vivo significance of the acetyl CoA diversion pathway, consider a disorder such as Barth Syndrome [6]. This IEM is caused by mutations in the TAZ gene, which codes for the cardiolipin transacylase, tafazzin. Characteristic phenotypic features are observed in this disorder, including dilated cardiomyopathy, muscle fatigue, neutropenia, lactic acidemia and 3MGC aciduria. Evidence indicates that tafazzin functions in cardiolipin acyl chain remodeling and, when missing or defective, the content and composition of cardiolipin in cristae membranes is altered. The occurrence of monolysocardiolipin, loss of tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin and increased cardiolipin acyl chain heterogeneity, leads to disruption of cristae membrane integrity [24]. When this occurs, ETC activity slows, resulting in compromised aerobic respiration. Under these conditions, reduced cofactors generated during oxidative metabolism are unable to donate electrons to the ETC and NADH and FAD2+ levels rise in the matrix space, thereby inhibiting the TCA cycle. To compensate, cells are forced to rely more on glycolysis to generate ATP, with lactic acid produced as a byproduct. Decreased acetyl CoA oxidation via the TCA cycle results in its diversion to cis-3MGC acid via the acetyl CoA diversion pathway. Over the long term, IEM-induced effects on energy metabolism in Barth Syndrome result in an inability to produce sufficient ATP to maintain the contractile function of the heart. When this occurs, dilated cardiomyopathy ensues. Hence, it is reasonable to consider that detection of 3MGC aciduria can provide a window into potential defects in mitochondrial energy metabolism that, over time, can lead to serious disease.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

(R,S)-HMG CoA, Coenzyme A, and synthetic standards of cis- and trans-3MGC acid (HPLC grade, >97% pure) were purchased from Millipore-Sigma and used without further modification. cis-3MGC anhydride was purchased from Carbosynth Limited, UK. Recombinant A. thaliana AUH was expressed in E. coli and isolated as described previously [25]. Rabbit α−3MGC IgG was prepared as described [16].

AUH enzyme assays.

Assays were conducted in 100 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, pH 8 at 25 °C or 37 °C by measuring AUH-dependent dehydration of HMG CoA to trans-3MGC CoA. Assays were initiated by the addition of 40 μg AUH to a buffered solution containing 250 μM HMG CoA. At indicated time points, 30 μl aliquots were removed and quenched with 30 μL 1 N HCl, which simultaneously inhibits enzymatic activity and stabilizes acyl CoA species present. Samples were then analyzed by HPLC directly or stored at −20 °C.

HPLC analysis.

Samples were chromatographed on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC fitted with a Kinetex® 5μm EVO C18 100 Å, 150 × 4.6 mm reversed phase column (Phenomenex) and a SecurityGuard™ ULTRA for EVO C18 guard column. The column was maintained at 30 °C. Thirty μL aliquots were injected onto the column and eluted with an isocratic flow rate of 0.5 mL / min for 10 minutes. The mobile phase consisted of a 6:94 ratio (v/v) of acetonitrile to 100 mM monosodium phosphate, 75 mM sodium acetate, adjusted to pH 4.6 using 1 M phosphoric acid [26]. Data analysis was conducted using Shimadzu Lab Solutions software. trans-3MGC CoA used as a HPLC standard was prepared in the laboratory using recombinant 3-methylcrotonyl CoA carboxylase, as described by Young et al [16], with the exception that the assay was conducted at 25 °C for 3 h.

Organic acid extraction.

Samples obtained following incubation of HMG CoA in the presence or absence of AUH were extracted from acidified aqueous media with ethyl acetate and dried under a stream of N2 gas. Dried extracts were dissolved in 100 μL anhydrous pyridine plus 100 μL bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide containing 1 % trichloromethylsilane and incubated for 30 min at 70 °C. The samples were then cooled, dried under a stream of N2 gas, and dissolved in 15 μL acetonitrile.

GC-MS analysis.

Silylated samples were applied to an Agilent 7890 GC equipped with a 5977 mass spectrometer detector (MSD) and flame ionization detector (FID). A 30 meter DB-5MS GC column connected with a 10 meter DuraGuard column (250 μm i.d. 0.250 μm film thickness) was used as the primary column. Samples (2 μl in acetonitrile) were injected via splitless injection. Injector temperature was held at 230 °C. Column flow rate (He) was a constant 2 ml/min. The GC oven was programmed with an initial temperature of 80 °C that was increased by 10 °C / min to 270°C and held for 10 min. Column eluent was directed to an FID electronic pressure control flow control manifold that splits the flow to the FID and MSD (~ 1:1 ratio). Columns running to the FID (1.7 m, 18 μm i.d.) or MSD (1 m, 200 μm i.d.) were comprised of deactivated fused silica. FID temperature was set to 240 °C. MSD transfer line was set to 280 °C. MSD parameters: EI 70 eV, m/z 40 – 700, 2 scans s−1. Data were analyzed using Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (selective ion extraction = 273 m/z).

Immunoblot assays.

Solutions containing HMG CoA (250 μM) and BSA (1 mg/ml) in 100 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, were incubated in the absence and presence of AUH (40 μg) for up to 24 h at 25 °C or 37 °C. At specified time points, aliquots were removed and applied to wells of a 4–20% acrylamide gradient gel. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. To determine the extent of BSA 3MGCylation, the membrane was blocked in TBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) and incubated with rabbit α−3MGC IgG (1:40,000) for 16 h at 4 °C. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed 4x with TBS-Tween 20 before, and after, antibody incubations. Antibody binding was detected by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS chemiluminescent substrate from ThermoScientific.

To assess the relative proportion of cis-3MGC anhydride that undergoes hydrolysis versus acylation, a solution containing 2.5 mg/ml cis-3MGC anhydride in 0.1 M sodium phosphate in D2O (pD = 8.0) was incubated in the absence and presence of BSA (0.5 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, the samples were spin filtered using a Vivaspin 500 centrifugal concentrator (10K MWCO; Sartorius). The corresponding filtrates were analyzed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy as described by Jones et al [14]. The amount of cis-3MGC acid in each sample was calculated utilizing 0.1 M sodium acetate as internal standard and comparing integration of the methyl proton resonances of cis-3MGC acid. In addition, an aliquot of the sample incubated with BSA was subjected to immunoblot analysis and probed with α−3MGC IgG, as described above.

In competition experiments, α−3MGC IgG (1:40,000) was pre-incubated for 16 h at 4 °C in the absence or presence of 250 μg trans-3MGC acid or 250 μg cis-3MGC acid. Following pre-incubation, the antibody-containing samples were used to probe separate immunoblots containing identical amounts of 3MGCylated BSA, prepared as described previously [16]. In other experiments, HMG CoA (250 μM) was incubated with AUH (40 μg) for 5 h at 37 °C and, following incubation, the assay product mix was incubated with α−3MGC IgG (1:120,000). Alternatively, the assay product mix was filtered (10K MWCO) to remove protein. Aliquots of the filtrate were then incubated with α−3MGC IgG (1:120,000) as described above. Following these incubations, the antibody samples were used to probe separate 3MGCylated BSA immunoblots, wherein each blot contained identical amounts of 3MGCylated BSA antigen. The extent of signal attenuation versus non-competed α−3MGC IgG was used to distinguish between 3MGC acid diastereomers in known and unknown samples.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R37-HL64159) to ROR. The authors thank Jazmin Jimenez for her support in GC-MS analysis, Sharon Young with expression of recombinant AUH, Dr. Kathy Schegg for assistance with AUH assays, Dr. Gilles Basset for providing the AUH plasmid construct and Dr. Andrzej Witkowski for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- IEM

inborn error of metabolism

- 3MGC

3-methylglutaconyl

- HMG

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl

- AUH

3-methylglutaconyl CoA hydratase

- HMGCL

HMG CoA lyase

- ETC

electron transport chain

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- GC-MS

gas chromatography - mass spectrometry

- FID

flame ionization detector

- MSD

mass spectrometry detector

- SIRT4

sirtuin 4

- ACOT

acyl CoA thioesterase

- 3HIV

3-hydroxylisovaleryl

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Wortmann SB, Duran M, Anikster Y, Barth PG, Sperl W, Zschocke J, Morava E, & Wevers RA (2013) Inborn errors of metabolism with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria as discriminative feature: proper classification and nomenclature. J Inherit Metab Dis 36, 923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su B & Ryan RO (2014) Metabolic biology of 3-methylglutaconic acid-uria: a new perspective. J Inherit Metab Dis 37, 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones DE, Perez L, & Ryan RO (2020) 3-methylglutaric acid in mitochondrial energy metabolism. Clin Chim Acta 502, 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santarelli F, Cassanello M, Enea A, Poma F, D’Onofrio V, Guala G, Garrone G, Puccinelli P, Caruso U, Porta F, & Spada M (2013) A neonatal case of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric-coenzyme A lyase deficiency. Ital J Pediatr 39, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wortmann SB, Kluijtmans LA, Sequeira S, Wevers RA, & Morava E (2014) Leucine loading test is only discriminative for 3-methylglutaconic aciduria due to AUH defect. JIMD Rep 16, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikon N & Ryan RO (2017a) Barth syndrome: connecting cardiolipin to cardiomyopathy. Lipids 52, 99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coelho MP, Correia J, Dia A, Nogueira C, Bandeira A, Martins E, & Vilarinho L (2019) Iron-sulfur cluster ISD11 deficiency (LYRM4 gene) presenting as cardiorespiratory arrest and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. JIMD Rep 49, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tort F, Del Toro M, Lissens W, Montoya J, Fernàndez-Burriel M, Font A, Buján N, Navarro-Sastre A, López-Gallardo E, Arranz JA, Riudor E, Briones P, & Ribes A (2011) Screening for nuclear genetic defects in the ATP synthase-associated genes TMEM70, ATP12 and ATP5E in patients with 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. Clin Genet 80, 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkby B, Roman N, Kobe B, Kellie S, & Forwood JK (2010) Functional and structural properties of mammalian acyl-coenzyme A thioesterases. Prog Lipid Res 49, 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikon N & Ryan RO (2016) On the origin of 3-methylglutaconic acid in disorders of mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis 39, 749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mack M, Schniegler-Mattox U, Peters V, Hoffmann GF, Liesert M, Buckel W, & Zschocke J (2006) Biochemical characterization of human 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase and its role in leucine metabolism. FEBS J 273, 2012–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iles RA, Jago JR, Williams SR, & Chalmers RA (1986) 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency studied using 2-dimensional proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. FEBS Lett 203, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelke UF, Kremer B, Kluijtmans LA, van der Graaf M, Morava E, Loupatty FJ, Wanders RJ, Moskau D, Loss S, van den Bergh E, & Wevers RA (2006) NMR spectroscopic studies on the late onset form of 3-methylglutaconic aciduria type I and other defects in leucine metabolism. NMR Biomed 19, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones DE, Ricker JD, Geary LM, Kosma DK & Ryan RO (2021) Isomerization of 3-methylglutaconic acid. JIMD Reports 58, 61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner GR, Bhatt DP, O’Connell TM, Thompson JW, Dubois LG, Backos DS, Yang H, Mitchell GA, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD, Grimsrud PA, & Hirschey MD (2017) A class of reactive acyl-CoA species reveals the non-enzymatic origins of protein acylation. Cell Metab 25, 823–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young R, Jones DE, Diacovich L, Witkowski A, & Ryan RO (2020) trans-3-methylglutaconyl CoA isomerization-dependent protein acylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 534, 261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apitz-Castro R, Rehn K, & Lynen F (1970) Beta methylcrotonyl-CoA-carboxylase. Crystallization and some physical properties. Eur J Biochem 16, 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KA, Huynh FK, Fisher-Wellman K, Stuart JD, Peterson BS, Douros JD, Wagner GR, Thompson JW, Madsen AS, Green MF, Sivley RM, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD, Backos DS, Capra JA, Olsen CA, Campbell JE, Muoio DM, Grimsrud PA, & Hirschey MD (2017) SIRT4 is a lysine deacylase that controls leucine metabolism and insulin secretion. Cell Metab 25, 838e855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betsinger CN & Cristea IM (2019) Mitochondrial function, metabolic regulation, and human disease viewed through the prism of sirtuin 4 (SIRT4) functions. J Proteome Res 18, 1929e–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedalov A, Chowdhury S, & Simon JA (2016) Biology, chemistry, and pharmacology of sirtuins. Methods Enzymol 574, 183–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkby B, Roman N, Kobe B, Kellie S, Forwood JK (2010) Functional and structural properties of mammalian acyl-coenzyme A thioesterases. Prog Lipid Res 49, 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tillander V, Arvidsson Nordström E, Reilly J, Strozyk M, Van Veldhoven PP, Hunt MC, Alexson SE (2014) Acyl-CoA thioesterase 9 (ACOT9) in mouse may provide a novel link between fatty acid and amino acid metabolism in mitochondria. Cell Mol Life Sci 71, 933–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wortmann SB, Kluijtmans LA, Engelke UFH, Wevers RA & Morava E (2012) The 3-methylglutaconic acidurias: what’s new? J Inher Metabol Dis. J Inherit Metab Dis 35, 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acehan D, Xu Y, Stokes DL, Schlame M (2007) Comparison of lymphoblast mitochondria from normal subjects and patients with Barth syndrome using electron microscopic tomography. Lab Invest 87, 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latimer S, Li Y, Nguyen TTH, Soubeyrand E, Fatihi A, Elowsky CG, Block A, Pichersky E, & Basset GJ (2018) Metabolic reconstructions identify plant 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase that is crucial for branched-chain amino acid catabolism in mitochondria. Plant J 95, 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shurubor YI, D’Aurelio M, Clark-Matott J, Isakova EP, Deryabina YI, Beal MF, Cooper AJL, & Krasinov BF (2017) Determination of coenzyme A and acetyl-coenzyme A in biological samples using HPLC with UV detection. Molecules 22, 1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]