Abstract

Objective:

Palliative care has the potential to improve goal-concordant care in severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI). Our primary objective was to illuminate the demographic profiles of sTBI patients who receive palliative care encounters (PCEs), with an emphasis on the role of race. Secondary objectives were to analyze PCE usage over time and compare healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) between patients with or without PCEs.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting, Participants, and Intervention:

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried for patients age ≥ 18 and a diagnosis of sTBI using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes. PCEs were defined using ICD-9 code V66.7 and trended from 2001 to 2015. To assess factors associated with PCE in sTBI patients, we performed unweighted generalized estimating equations regression. PCE association with decision making was modeled via its effect on rate of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement. To quantify differences in PCE-related decisions by race, race was modeled as an effect modifier.

Measurements and Main Results:

From 2001 to 2015, the proportion of palliative care usage in sTBI patients increased from 1.5% to 36.3%, with 41.6% of white versus 22.3% of black and 25% of Hispanic sTBI patients having a palliative care consultation in 2015. From 2008 to 2015, we identified 17,673 sTBI admissions. White and affluent patients were more likely to have a PCE than Black and Hispanic and low SES patients. Across all races, patients receiving a PCE resulted in a lower rate of PEG tube placement; however, white patients exhibited a larger reduction of PEG tube placement versus Black patients. Patients using palliative care had lower total hospital costs (median $16,368 versus $26,442).

Conclusions:

Palliative care usage for sTBI has increased dramatically this century, and it reduces resource utilization. This is true across races, however, its usage rate and associated effect on decision-making are race-dependent, with white patients receiving more PCE and being more likely to decline a PEG tube if they have had a PCE.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, palliative care, racial disparity, healthcare resource utilization

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health issue. In the United States, 2.5 million people suffer TBIs annually, leading to 230,000 hospitalizations, 50,000 deaths, and $20.6 billion in work loss. Severe TBI (sTBI) patients have a high mortality rate (31%-49%) and many survivors have long-term neurological disability1,2. TBI guideline-driven care is aimed at improving survival and decreasing disability3. It is important to balance interventions in sTBI aimed at improving survival with those geared toward patient quality of life and reducing caregiver burden. Palliative care consultation aids medical teams and families navigate between medical interventions focused on life extension and quality of life4,5.

Palliative care aims to prevent suffering and improve quality of life by both optimizing symptom management and holistically supporting patients and families6–8. Over the past decade, hospital-based palliative care consultations have increased by 26%9. The increasing use10 of specialty palliative care has decreased hospital resource utilization10. Moreover, in elderly trauma patients, palliative care consultation has been shown to improve satisfaction for caregivers and patients during goals of care discussions11.

Beyond influences on utilization, quality of life, and caregiver well-being, palliative care consultation has the potential to help address racial disparities in resource utilization in sTBI. Black patients suffer a 35% higher incidence of TBI12 and higher likelihood of worse functional outcomes13. In sTBI, Black patients are less likely to choose withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment than their white counterparts14. Though there are real cultural and personal differences in opinion regarding goals of care after severe injury or at the end of life15, studies have shown that Black patients are open to having discussions regarding end-of-life and palliative care if presented with the opportunity16. In light of the racial disparities in TBI incidence, prognosis and treatment, understanding the relationship between these components becomes essential.

In this study of sTBI patients, we aim to 1) characterize trends in palliative care usage and its association with resource utilization, 2) identify characteristics associated with palliative care use and 3) analyze potential racial disparities regarding the impact of palliative care on rates of aggressive treatment usage, particularly PEG tube usage. Based on prior work identifying differences in utilization of gastrostomy and tracheostomy by race in TBI, we decided to use gastrostomy as a proxy for study of aggressive interventions17. Of note, in this manuscript, we will use PCE as an abbreviation for palliative care encounter to describe times when specialty consultation to a palliative care provider was involved.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Objective

We aim to understand which sTBI patients received PCEs. As part of this objective, a national trend in PCEs was assessed. The secondary objective of the study was to 1) compare healthcare resource utilization between patients with and without PCEs and 2) assess racial disparity in PCE use, primarily by describing differences in PEG utilization, though we also quantify other invasive procedure rates and clinical outcomes.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study examined sTBI admissions using discharge data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)18. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and a diagnosis of severe TBI using the comprehensive list of inpatient International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes chosen by the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) 2012 Criteria19. Severe (i.e. loss of consciousness > 24 hours) and penetrating TBI were combined into one cohort. Patients whose TBI severity could not be classified were not included. Discharge records with invalid principal procedure code (n = 2), missing sex (n = 28), missing hospital information (n = 304), and extreme age values (age >110) were excluded.

Because palliative care was formally recognized as a medical subspecialty in 2008 and coding/billing practices may have changed with this evolution (despite physicians practicing aspects of palliative care long before this century)10, the inclusion of prior years could confound the analysis. Therefore, palliative care time trends were summarized across all years, but the analysis of association between prognostic factors and PCEs was only conducted on patients with admissions from 2008–2015.

Proxy Codes

Independent variables that are not readily available in NIS were derived using ICD diagnosis codes or procedure codes. Injury Severity Score (ISS) was derived by mapping ICD-9 diagnosis codes to Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), using the ICD Programs for Injury Categorization (ICDPIC)20. Mechanism of Injury (MOI) was defined using NIS variable ECODE1-ECODE4, and was classified into four categories: unintentional MVT, unintentional fall, assault and self-harm, struck by or against an object, and other/unknown21. Frailty score was derived using the 19-item Frailty Risk Scale (FRS) system22, where the score was the count of frailty items the patients had. Reoperation with craniotomy or craniectomy was defined as repeat surgery procedure codes within the same hospital admission.

Cost Analyses

Inpatient charges were converted to inpatient costs using NIS cost-to-charge ratio files (ratio variable GAPICC before 2012, APICC after 2012). Top 1% and bottom 1% of the charges and costs were considered outliers and were removed to obtain the trimmed values. All charges and costs were adjusted for inflation using 2019 as the reference year using data provided by US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistic23.

Palliative Care Trends Analyses

PCEs were identified using the ICD-9 code V66.7 as in previous studies24–26. To investigate the national trend of PCE for patients with admissions for sTBI from 2001 to 2015, weighted analysis was conducted accounting for clustering and stratification for the complex NIS survey design. NIS discharge weights were utilized to calculate weighted frequencies and percentages following HCUP Methods Series Report27.

Factors Associated with Palliative Care

To assess factors associated with PCE, unweighted regression analysis was performed for patients with admission of sTBI between 2008 and 2015. The generalized estimating equations (GEE) method was used to model palliative care use with a logit link function to account for the clustering of patients admitted to the same hospitals in the same year. Covariates included age, admission day on weekend, frailty score, penetrating injury, late effects of cerebrovascular disease, renal failure, metastatic cancer, ISS, subdural/epidural hemorrhage, sex, insurance type, race, household income quartile (here treated as a reflection of socioeconomic status, SES), hospital location and teaching status, hospital region, hospital control ownership, transfer in status, and primary mechanism of injury (MOI). All missing values were coded to an “unknown”. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize secondary outcomes.

Race as an Effect Modifier for Palliative Care

Descriptive analysis was conducted to compare PCE rate and patient outcomes among different racial groups. Asian/Pacific Islanders and American Indians were combined into the Other/Unknown group to be consistent with the study team’s prior research14 and maintain appropriate subgroup sample sizes. Per precedent, Hispanic patients were assigned to the Hispanic group regardless of their other races identified28. We chose to specifically analyze the association of PCE with utilization of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) because the timing of the decision is typically delayed and therefore less influenced by variable emergency care and the decision regarding PEG is a common timepoint providers use to discuss goals of care and continuation of treatment with surrogate decision makers. We recognize that there are multiple procedures involved in the care of sTBI patients and not all are studied within this manuscript. To examine if the association of PCE on reducing PEG tube utilization differed among racial groups, race was modeled as an effect modifier with PCE. Adjusted modified Poisson regression models were used to obtain estimates and 95% CIs for the following according to Knol and VanderWeele’s recommendations29: i) Relative risks (RRs) for each stratum of race and PCE group with a single referent category; ii) RR of PEG tube use between patients receiving PCE versus no PCE within each racial group30; iii) measures of effect modification on the additive scale - relative excess risks due to interaction (RERI) between race and PCE with their 95% CIs estimated by 1000 bootstrap samples31; iv) measures of effect modification on the multiplicative scale - ratio of RRs comparing utilization of PEG Tube among different racial groups. The generalized estimating equations (GEE) were utilized with a log link and a Poisson distribution to obtain the RRs and measures of interactions, controlled for the clustering of hospital center and covariates that were included in the model of PCE utilization.

Software

In all cases, statistical significance was assessed at level alpha = 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9,4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Inclusion and Demographics

859,220 patients were identified with TBI in the NIS database between 2001 and 2015, of which 35,456 experienced sTBI. In 2008 or later, 17,705 patients had a sTBI. Following removal of excluded patients based on missing values, 17,369 patients remained in the analysis (eFigure 1).

A total of 17369 patients with admissions after 2008 were included in the analysis of investigating potential factors associated with palliative care use. Patients who had palliative care encounters were older (median age: 71 vs 48 years). There were also more females (37.6% vs 27.7%), more white patients (69.5% vs 59.5%), and more patients with renal failure (7.2% vs 3.3%) and subdural/epidural hemorrhage (36.6% vs 22.8%) in this group. However, the two groups were similar in overall injury severity (ISS), head injury severity (AIS), comorbidity condition before the injury (Elixhauser comorbidity index), frailty score, and household income (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Characteristics Palliative Care Use

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=13279) | (N=4090) | (N=17369) | |

| Age in years at admission | |||

| Mean (SD) | 49.2 (22.0) | 65.9 (20.2) | 53.1 (22.8) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 48.0 (29.0–67.0) | 71.0 (52.0–83.0) | 53.0 (32.0–73.0) |

| Range | (18.0–111.0) | (18.0–101.0) | (18.0–111.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9607 (72.3%) | 2554 (62.4%) | 12161 (70.0%) |

| Female | 3672 (27.7%) | 1536 (37.6%) | 5208 (30.0%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 7899 (59.5%) | 2841 (69.5%) | 10740 (61.8%) |

| Black | 1299 (9.8%) | 239 (5.8%) | 1538 (8.9%) |

| Hispanic | 1421 (10.7%) | 256 (6.3%) | 1677 (9.7%) |

| Other/Unknown | 2660 (20.0%) | 754 (18.4%) | 3414 (19.7%) |

| Subdural/epidural hemorrhage | 3021 (22.8%) | 1495 (36.6%) | 4516 (26.0%) |

| Injury severity score (ISS) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.2 (9.7) | 21.1 (8.8) | 22.0 (9.5) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 22.0 (16.0–26.0) | 25.0 (16.0–25.0) | 22.0 (16.0–26.0) |

| Range | (4.0–75.0) | (4.0–75.0) | (4.0–75.0) |

| Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) head score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.9 (0.9) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Range | (2.0–6.0) | (2.0–6.0) | (2.0–6.0) |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | 6.7 (9.0) | 6.6 (9.0) | 6.6 (9.0) |

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 4.0 (0.0–11.0) | 4.0 (0.0–11.0 | 4.0 (0.0–11.0) |

| Range | (−19.0–53.0) | (−18.0–47.0) | (−19.0–53.0) |

| Frailty score | |||

| 0 | 8788 (66.2%) | 2367 (57.9%) | 11155 (64.2%) |

| 1 | 3393 (25.6%) | 1213 (29.7%) | 4606 (26.5%) |

| 2 | 872 (6.6%) | 400 (9.8%) | 1272 (7.3%) |

| 3 | 191 (1.4%) | 91 (2.2%) | 282 (1.6%) |

| 4+ | 35 (0.3%) | 19 (0.5%) | 54 (0.3%) |

| Renal failure | 438 (3.3%) | 296 (7.2%) | 734 (4.2%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 57 (0.4%) | 70 (1.7%) | 127 (0.7%) |

| Median household income national quartile | |||

| First quartile (lowest) | 4110 (31.0%) | 1044 (25.5%) | 5154 (29.7%) |

| Second quartile | 3255 (24.5%) | 1080 (26.4%) | 4335 (25.0%) |

| Third quartile | 2910 (21.9%) | 986 (24.1%) | 3896 (22.4%) |

| Fourth quartile (highest) | 2423 (18.2%) | 852 (20.8%) | 3275 (18.9%) |

Prevalence of PCE increased over time.

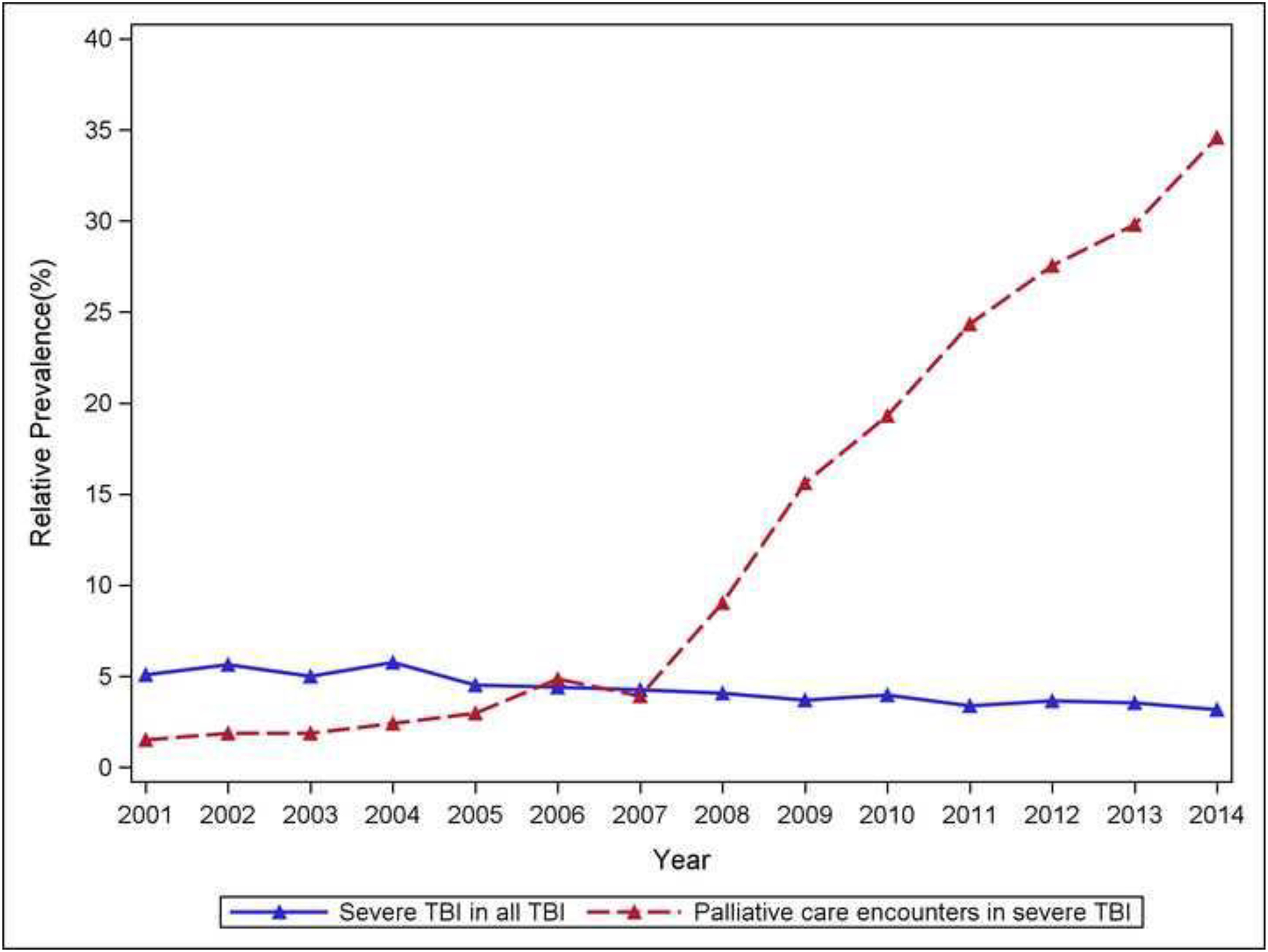

Weighted analysis was conducted to investigate the national time trend of having palliative care encounters for patients with admissions for sTBI in NIS from 2001 to 2015. There were 35,346 discharges with sTBI, which represented a weighted estimate (per method of calculating trends in NIS) of 169,569 discharges nationwide. The trend was illustrated in eTable 1 and Figure 1. From 2001 to 2007, the proportion of palliative care usage in sTBI patients increased slowly and was relatively stable at 1.5 to 5%. This percentage increased to 9% in 2008 and to 36.3% in 2015 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time trend of palliative care utilization, demonstrating a notable increase from 2001 to 2015.

Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to have PCE.

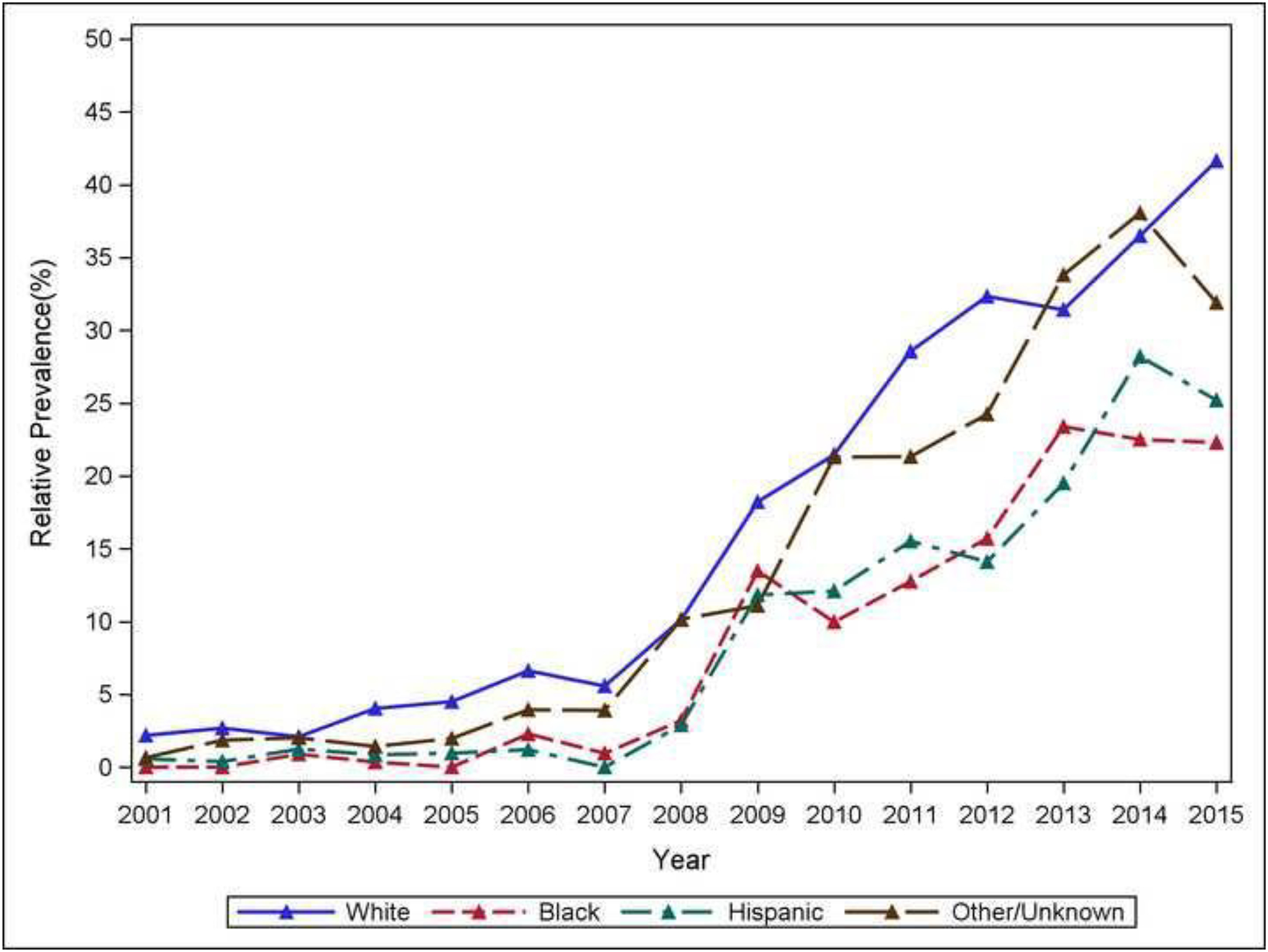

Rate of palliative care in different race groups are reported in eTable 2. White patients and patients in the Other/Unknown category tended to use palliative care more than those who were Black or Hispanic.

Comparison of palliative care use between Black and white patients over years was plotted in Figure 2. The percentage of white sTBI patients using palliative care reached 41.6% (weighted) in 2015, compared to 22.3% (weighted) of Black patients and 25.2% (weighted) of Hispanic patients in the same year.

Figure 2.

Racial differences in time trend of palliative care utilization. Palliative care consultations were used almost twice as frequently for white patients compared to their Black and Hispanic counterparts.

Length of stay, procedural utilization, and costs were less for patients with PCE; mortality was higher.

Patients who used palliative care had lower costs (median $16,368 vs $26,442), shorter LOS (median 2 vs 3 days), fewer inpatient complications (75.1% vs 80.7%), fewer craniotomies (6.3% vs 10.2%), lower rates of mechanical ventilation during hospitalization (79.1% vs 85.4%), and less usage of other aggressive procedures such as invasive intracranial pressure monitoring and placement of central lines (33.8% vs 42.2%; eTable 3). However, the in-hospital mortality rate of this group was also higher than that of patients who did not receive palliative care (87.3% vs 67.7%, eTable 4).

Independent Variables Associated with Receiving Palliative Care: Regression Model

A 10-year increase in age was associated with a 34% increase in the odds of using palliative care (95% CI: [1.30, 1.38]). In addition to age, factors that are associated with increased odds of receiving palliative care included renal failure, late effects of cerebrovascular disease, metastatic cancer, lower ISS, subdural/epidural hemorrhage, year of admission, being female, being white, higher SES, larger hospital bed number, hospitals in the West, private non-profit hospitals, being transferred in from another acute care hospital, and primary MOI of unintentional fall (eTable 5).

Palliative care decreases utilization of PEG tube, but more so for white patients.

Table 3 provides the summary statistics of PEG tube utilization between patients with and without PCE in different racial groups. Across all races, patients receiving a PCE had a lower rate of PEG tube placement. Specifically, the proportion receiving a PEG tube dropped from 13% to 2.3% for white patients, from 16.8% to 5.9% for black patients, and from 15.7% to 5.5% for Hispanic patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of PCE on PEG Tube Utilization by Race

| PCE | No PCE | RR (95% CI); P for PCE vs. No PCE within strata of race | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG/No PEG Tube | RR (95% CI); P | PEG/No PEG Tube | RR (95% CI); P | ||

| White | 65/2776 | 1.0 (Reference) | 1030/6869 | 4.62 (3.57, 5.98); P<.001 | 0.22 (0.17, 0.28); P<0.001 |

| Black | 14/225 | 2.21 (1.24, 3.92); P=0.007 | 218/1081 | 5.59 (4.24, 7.38); P<.001 | 0.39 (0.23, 0.67); P=0.001 |

| Hispanic | 14/242 | 1.92 (1.11, 3.33); P=0.020 | 223/1198 | 5.20 (3.94, 6.87); P<.001 | 0.37 (0.22, 0.61); P<.001 |

| Other | 24/730 | 1.27 (0.81, 1.98); P=0.295 | 342/2318 | 4.40 (3.36, 5.78); P<.001 | 0.29 (0.19, 0.44); P<.001 |

Adjusted measure of effect modification on additive scale (RERI) (White as reference): Black 0.07 (-0.19, 0.30); Hispanic 0.09 (-0.11, 0.29); Other 0.11 (-0.02, 0.23). Confidence intervals of RERIs were obtained from 1000 bootstrap samples.

Adjusted measure of effect modification on multiplicative scale (ratio of RRs) (White as reference): Black 1.82 (1.02, 3.27); Hispanic 1.71 (0.98, 2.98); 1.33 (0.84, 2.12).

RRs, RERIs, and ratio of RRs were adjusted for age, admission day on weekend, frailty score, penetrating injury, late effects of cerebrovascular disease, renal failure, metastatic cancer, ISS, subdural/epidural hemorrhage, sex, insurance type, race, household income quartile, hospital location and teaching status, hospital region, hospital control ownership, transfer in status, primary mechanism of injury (MOI), and calendar year, controlled for clustering effect of hospital center and calendar year.

The results after adjusting for covariates are also presented in Table 3. For white patients, PCE was associated with a 78% decrease in the rate of having a PEG tube placed (RR 0.22, 95% CI [0.17, 0.28]). On the other hand, for Black patients, PCE was associated with a 61% decrease in the rate of having a PEG tube placed (RR 0.39, 95% CI [0.23, 0.67]).

Table 3 presents the role of race as an effect modifier for PCE as it is associated with PEG tube placement, from both the additive and multiplicative perspectives. When controlling for covariates and comparing Black versus white patients, the differences between the association of PCE on the PEG tube placement use were not statistically significant on the additive scale (RERI 0.07, 95% CI [-0.19, 0.30]). In other words, the absolute differences in risks of PEG tube placement between the PCE and No PCE groups were not statistically different when comparing Black versus white patients. However, the differences were significant on the multiplicative scale, which is important because it compares relative risks by race. The ratio of RRs across race stratum was 1.82 (95% CI [1.02, 3.27]), indicating that the estimated relative risk of PEG tube placement comparing PCE vs. No PCE was 82% higher for Black patients (adjusted RR 0.39) than that for white patients (adjusted RR 0.22).

DISCUSSION

We analyzed database records of palliative care encounters (PCEs) in sTBI. Patient and hospital factors were associated with increased odds of consulting palliative care. Patients who received palliative care consultation during the sTBI admission utilized less hospital resources. Compared to white patients, Black patients had higher inpatient costs and higher rates of invasive procedures such as craniotomy, mechanical ventilation, and PEG tube placement but also fewer PCEs. Hispanic patients also had less PCEs. PCE was associated with reduced utilization of PEG tubes for patients of all races with nuanced effects depending on race.

The rate of palliative care encounters for sTBI patients increased between 2001 and 2015. The upward trend of PCEs is particularly visible after 2008 when palliative care was more widely recognized as a distinct speciality, and it also mirrors trends for other disease processes associated with increases in PCEs following 200832. Considering the concentrated effort to increase the use of palliative care in sTBI, these trends in utilization are particularly relevant7,33.

Palliative care encounters have not risen as quickly for patients of color. Our study showed key demographic differences in utilization of PCE including patients of white race and wealthier patients being more likely to get PCEs than Black and Hispanic patients and, separately, patients with low SES. There are several possible explanations for this. Black patients suffer more TBI with worse functional outcomes; sicker patients may not be offered palliative care. There is evidence that Black patients may present to centers with less palliative care experience at the end of life. To avoid effects related to center, we controlled for both hospital type and teaching status. Additionally, Black patients are more likely to choose aggressive care and less likely to choose palliative approaches despite expressing quality of life-focused goals for their loved ones14,34,35. Differences in opinion among racial groups regarding goals of care after severe injury exist15. Prior research in palliative care has cited cultural backgrounds, religious beliefs, treatment preferences, knowledge inequities, and organizational barriers as reasons why Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to seek palliative care services36. The key is to align care with patient goals, allowing for cultural differences in decisions, and palliative care has the potential to do this.

PCEs were associated with decreased PEG tube utilization among Black and Hispanic patients. This association had a smaller effect size than that for white patients. This difference can be explained in a variety of ways; PCE may partially close a gap between Black patients and the medical system that has been widened by poor trust, cultural differences, communication and barriers to access37. This may represent a cultural inclination towards more aggressive care that is clarified rather than altered by a PCE.

We found that PCEs were associated with decreased utilization and inpatient cost for all patients. This may be mediated by shorter length of stay and less utilization of invasive procedures, as . It is important to note that sicker patients did receive palliative care consultation and therefore these shorter lengths of stay and decisions not to pursue aggressive care (such as a PEG tube) likely related to severity of illness. Additionally, withdrawal of life-sustatining treatment decisions are associated with earlier mortality and therefore decreased utilization. This being said, the regression analysis did control for many clinical factors including age, ISS, frailty score, and multiple specific comorbidities. It did not control for decision to withdrawal life-sustaining treatment and this interaction should be explored in further studies. It is important to try to navigate the challenging decisions in sTBI in a way that is least burdensome to the patient, their family, and the healthcare system.

The US dedicates significant resources to end-of-life surgery38. At times, these resources do not result in improved outcomes and rather prolong suffering for the patient and their family. This study shows that PCE can be effective in lowering utilization of aggressive care. Many argue that early involvement of palliative care consultation in sTBI will improve goal-concordant care33,39. Ensuring goal-concordant care can improve patient and caregiver outcomes, while decreasing unnecessary resource utilization. This data also shows that PCE can in part mitigate racial disparities in decision making after sTBI. Unfortunately, PCE is under-utilized in patients of color and low SES patients. This is a place where the healthcare community can focus on improving goal-concordant care for all patients.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. This study is a retrospective cohort and therefore no causality or temporal relationship can be inferred. The coding differences in PCE and variable sensitivity of the V66.7 code40,41 are limitations to the study and many previous studies related to usage of palliative care consultation. Moreover, there are likely confounding variables that could not be measured in this database, for example, race of provider, details of palliative and decision making conversations, and patient and family prior experience. Future studies could address these limitations by running prospective experiments based on the hypothesis-generating findings presented here.

CONCLUSIONS

PCE is associated with decreased utilization of aggressive interventions, particularly PEG tubes following sTBI. PCE rates are different between patients of color and white patients. Our model of PEG tube utilization shows that PCE decreases PEG use for patients of all races, though the effect is largest in white patients. An important area of further study is how PCE helps to align patient preferences with treatment options despite racial and cultural differences.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram

Table 2.

Patient Discharge Outcomes Palliative Care Use

| No | Yes | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=13279) | (N=4090) | (N=17369) | |

| Trimmed costs ($) * | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45647.9 (48606.5) | 27772.2 (31143.8) | 41437.5 (45738.7) |

| Median | 26442.3 | 16368.4 | 23748.2 |

| Q1-Q3 | 12337.6–61088.7 | 7710.5–36931.2 | 11005.5–53948.9 |

| Range | (1561.7–285790.6) | (1552.3–256605.4) | (1552.3–285790.6) |

| Missing | 816 | 250 | 1066 |

| Length of stay | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.1 (20.6) | 4.9 (8.4) | 9.6 (18.7) |

| Median | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| Q1-Q3 | 1.0–14.0 | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–11.0 |

| Range | (0.0–331.0) | (0.0–205.0) | (0.0–331.0) |

| Missing | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Died during hospitalization | |||

| Did not die in hospital | 4274 (32.2%) | 518 (12.7%) | 4792 (27.6%) |

| Died in hospital | 8989 (67.7%) | 3572 (87.3%) | 12561 (72.3%) |

| Missing | 16 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (0.1%) |

| Any Complication | 10712 (80.7%) | 3070 (75.1%) | 13782 (79.3%) |

| Craniotomy | 1348 (10.2%) | 256 (6.3%) | 1604 (9.2%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 11343 (85.4%) | 3234 (79.1%) | 14577 (83.9%) |

| Any Other Invasive Procedure | 5605 (42.2%) | 1381 (33.8%) | 6986 (40.2%) |

| Ventriculostomy | 1718 (12.9%) | 449 (11.0%) | 2167 (12.5%) |

| Incision/Excision of brain or meninges | 2467 (18.6%) | 685 (16.7%) | 3152 (18.1%) |

| Invasive ICP monitoring | 2219 (16.7%) | 510 (12.5%) | 2729 (15.7%) |

| Central line | 651 (4.9%) | 260 (6.4%) | 911 (5.2%) |

| PEG tube | 1813 (13.7%) | 117 (2.9%) | 1930 (11.1%) |

Outliers (top 1% and bottom 1%) were removed for trimmed values.

Funding/Support:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002553. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Lemmon receives salary support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23NS116453)

Footnotes

This manuscript complies with Ethical approval and informed consent for human studies.

This manuscript complies with ethical standards for animal studies

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper DJ, Myles PS, McDermott FT, et al. Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291(11):1350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks JC, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Hammond FM, Harrison-Felix CL. Long-term disability and survival in traumatic brain injury: results from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Model Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94(11):2203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giacino JT, Katz DI, Schiff ND, et al. Practice guideline update recommendations summary: Disorders of consciousness: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Neurology 2018;91(10):450–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dijck JTJM, Dijkman MD, Ophuis RH, de Ruiter GCW, Peul WC, Polinder S. In-hospital costs after severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and quality assessment. PLOS ONE 2019;14(5):e0216743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lilley EJ, Scott JW, Weissman JS, et al. End-of-Life Care in Older Patients After Serious or Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Low-Mortality Hospitals Compared With All Other Hospitals. JAMA surgery 2018;153(1):44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, Lavery R, Retano A, Livingston DH. Changing the Culture Around End-of-Life Care in the Trauma Intensive Care Unit: The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 2008;64(6):1587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang F, Pentakota SR, Glass NE, Berlin A, Livingston DH, Mosenthal AC. Older Patients With Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: National Variability in Palliative Care. The Journal of surgical research 2020;246:224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO | WHO Definition of Palliative Care [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2020 Oct 8];Available from: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS. The Growth of Palliative Care in U.S. Hospitals: A Status Report. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2016;19(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative Care Consultation Teams Cut Hospital Costs For Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Affairs 2011;30(3):454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGraw C, Vogel R, Redmond D, et al. Comparing satisfaction of trauma patients 55 years or older to their caregivers during palliative care: Who faces the burden? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90(2):305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry C, Ley EJ, Mirocha J, Salim A. Race affects mortality after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Surgical Research 2010;163(2):303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arango-Lasprilla JC, Rosenthal M, Deluca J, et al. Traumatic brain injury and functional outcomes: Does minority status matter? Brain Injury 2007;21(7):701–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williamson T, Ryser MD, Ubel PA, et al. Withdrawal of Life-Supporting Treatment in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Surg 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givler A, Bhatt H, Maani-Fogelman PA. The Importance Of Cultural Competence in Pain and Palliative Care [Internet]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493154/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waters CM. End-of-life care directives among African Americans: lessons learned--a need for community-centered discussion and education. Journal of Community Health Nursing 2000;17(1):25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RC, Creutzfeldt CJ, Cox CE, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health Care Utilization Following Severe Acute Brain Injury in the United States. J Intensive Care Med 2020;885066620945911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. HCUP-US NIS Overview [Internet]. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2011. [cited 2020 Nov 5];Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 19.ICD-10 Coding Guidance for Traumatic Brain Injury Training Slides [Internet]. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. 2015. [cited 2020 Nov 5];Available from: https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/material/icd-10-coding-guidance-traumatic-brain-injury-training-slides [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark DE, Osler TM, Hahn DR. ICDPIC: Stata module to provide methods for translating International Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision) diagnosis codes into standard injury categories and/or scores [Internet]. 2009. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457028.html

- 21.Taylor CA, Greenspan AI, Xu L, Kresnow M-J. Comparability of national estimates for traumatic brain injury-related medical encounters. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015;30(3):150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SM, Lekan D, Risoli T, et al. Association Between Dysphagia and Inpatient Outcomes Across Frailty Level Among Patients ≥ 50 Years of Age. Dysphagia 2020;35(5):787–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Consumer Price Index Data from 1913 to 2020 [Internet]. US Inflation Calculator. 2008. [cited 2020 Oct 26];Available from: https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/consumer-price-index-and-annual-percent-changes-from-1913-to-2008/

- 24.Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative Care for Hospitalized Patients With Stroke: Results From the 2010 to 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Stroke 2017;48(9):2534–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy SB, Moradiya Y, Hanley DF, Ziai WC. Palliative Care Utilization in Nontraumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage in the United States. Crit Care Med 2016;44(3):575–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruck JM, Canner JK, Smith TJ, Johnston FM. Use of Inpatient Palliative Care by Type of Malignancy. J Palliat Med 2018;21(9):1300–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houchens RL, Ross D, Elixhauser A. HCUP-US Methods Series [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [cited 2020 Nov 4];Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) [Internet]. 2008. [cited 2021 Mar 10];Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/siddistnote.jsp?var=hispanic [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41(2):514–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yelland LN, Salter AB, Ryan P. Performance of the modified Poisson regression approach for estimating relative risks from clustered prospective data. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174(8):984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assmann SF, Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Mundt KA. Confidence intervals for measures of interaction. Epidemiology 1996;7(3):286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roeland Eric J., MDa; Triplett Daniel P., MPHb; Matsuno Rayna K., PhD, MPHb; Boero Isabel J., BSb; Hwang Lindsay, BSb; Yeung Heidi N., MDa; Mell Loren, MDb; and Murphy James D., MD, MSb. Patterns of Palliative Care Consultation Among Elderly Patients with Cancer. Journal of National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2016;14(4):439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosenthal AC. Dying of Traumatic Brain Injury-Palliative Care too Soon, or too Late? JAMA Surg 2020;155(8):731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonner GJ, Freels S, Ferrans C, et al. Advance Care Planning for African American Caregivers of Relatives With Dementias: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38(6):547–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ormseth CH, Falcone GJ, Jasak SD, et al. Minority Patients are Less Likely to Undergo Withdrawal of Care After Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2018;29(3):419–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KS. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2013;16(11):1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, et al. Palliative and End-of-Life Care in the African American Community. JAMA 2000;284(19):2518–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwok AC, Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, et al. The intensity and variation of surgical care at the end of life: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378(9800):1408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livingston DH, Mosenthal AC. Withdrawing life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury. CMAJ 2011;183(14):1570–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hua M, Li G, Clancy C, Morrison RS, Wunsch H. Validation of the V66.7 Code for Palliative Care Consultation in a Single Academic Medical Center. J Palliat Med 2017;20(4):372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feder SL, Redeker NS, Jeon S, et al. Validation of the ICD-9 Diagnostic Code for Palliative Care in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure Within the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35(7):959–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Consort Diagram