Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been linked to multiple immune system related genetic variants. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) genetic variants are risk factors for AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, soluble TREM2 isoform (sTREM2) is elevated in cerebrospinal fluid in the early stages of AD and associated with slower cognitive decline in a disease stage dependent manner. Multiple studies have reported an altered peripheral immune response in AD. However, less is known about the relationship between peripheral sTREM2 and an altered peripheral immune response in AD. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between human plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory activity in AD. The hypothesis of this exploratory study was that sTREM2 related inflammatory activity differs by AD stage. We observed different patterns of inflammatory activity across AD stages that implicates early stage alterations in peripheral sTREM2-related inflammatory activity in AD. Notably, fractalkine showed a significant relationship with sTREM2 across different analyses in the control groups that was lost in later AD-related stages with high levels in the MCI. Although, multiple other inflammatory factors either differed significantly between groups or were significantly correlated with sTREM2 within specific groups, three inflammatory factors (FGF-2, GM-CSF and IL-1β) are notable since they exhibited both lower levels in AD, compared to MCI, and a change in the relationship with sTREM2. This evidence provides important support to the hypothesis that sTREM2-related inflammatory activity alterations are AD stage specific and provides critical information for therapeutic strategies focused the immune response.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, plasma, TREM2, inflammation, cytokines, FGF-2, GM-CSF, IL-1β, fractalkine, ATN

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that impacts 5.8 million Americans and is the 6th leading cause of death in the United States (1). Multiple studies suggest that AD-related pathology, which includes amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles, accumulates years prior to the onset of dementia symptoms which delays a clinical diagnosis of AD until after neurodegeneration manifests as cognitive decline and the inability to manage daily living activities (2, 3).

Clinical stages of AD progression are primarily based on clinical signs and symptoms while a more recent classification method is based on CSF biomarkers. In the classic symptomatic classification, asymptomatic individuals are classified as “cognitively normal,” often in the absence of testing for CSF biomarkers and brain pathology. Cognitively normal (CN) individuals are without symptoms of dementia such as memory loss. The next stage is mild cognitive impairment (MCI), in which cognition has declined to an extent greater than expected for one’s age but without having Alzheimer’s disease or other diagnoses. This form of MCI thought to progress into AD dementia is referred to as amnestic MCI (4). Finally, a person can progress to AD dementia, of which there are also progressively mild, moderate, and severe forms (5). The ATN continuum is a second method of defining stages of AD dementia, and can be based on measures of CSF biomarker proteins or neuroimaging. “ATN” refers to “A” amyloid β (Aβ), “T” phosphorylated tau (p-Tau), and “N” neurodegeneration. Aβ is normally 40kD (Aβ40), while a pathogenic form is 42kD (Aβ42). The ATN categories can be utilized to identify different stages of Aβ or tau abnormalities. Individuals without CSF Aβ or tau abnormalities can be categorized as A−T−N−. The early first stage is A+T−N− if an individual has only altered CSF Aβ42/Aβ40. The next stage is A+T+N− if an individual has both CSF Aβ and p-Tau pathology. The last more severe stage is A+T+N+ if an individual has abnormal CSF Aβ, p-Tau and t-Tau, a biomarker of neurodegeneration, which is more typical in AD than CN individuals (6).

AD is a disease of the brain, but there is evidence that peripheral inflammation is associated with AD (7, 8). Several inflammatory disorders are risk factors for AD including obesity, metabolic syndrome, traumatic brain injury, and chronic periodontitis development (9). It has been suggested that recurrent inflammatory events over one’s life including infections, ischemia, and free radical exposure, parallel to the accumulation of Aβ, can increase the risk of AD development due to the repeated cycle of activated immune cells both in the peripheral and the central nervous system (10). The mechanism underlying the link between peripheral inflammation and AD is not fully understood.

In order to better understand the role of peripheral inflammation and AD, studies have measured levels of circulating inflammatory factors. Importantly, there is evidence that immune system dysregulation can also contribute to risk of AD, and it may be the lack of a proper immune system reaction that makes people susceptible to repeated infections and consequently AD. For example, a retrospective review of hospital data found that participants admitted to the hospital with autoimmune disorders were more likely to be diagnosed with AD, and 18 of the 25 autoimmune disorders that were part of the study showed significant correlations with dementia (11). Similarly, age-related decline in immune system function, referred to as immunosenescence, may contribute to risk of AD (12). Meta-analyses of inflammatory factors in people with AD compared to controls often show mixed results which may be a result of pathological heterogeneity across study groups and confounding factors including age and APOE e4 status (13–15).

One immune receptor associated with AD is triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2). Normally, TREM2 functions as a pattern recognition receptor in the innate immune response. It is expressed on microglia in the brain and other myeloid cells in peripheral blood. Several loss-of-function mutations in TREM2 have been shown to increase AD risk (16, 17). The R47H TREM2 mutation, results in decreased function of the receptor (16). Another mutation associated with increased AD risk is H157Y. It leads to less full-length cell-surface TREM2 and more of the cleaved version, soluble TREM2 (sTREM2), which is detectible in CSF and plasma (18, 19). Increased CSF sTREM2 in MCI and AD has been described in multiple studies, while results from plasma are less clear, and neither CSF sTREM2 or plasma sTREM2 are feasible biomarkers given the modest elevation in MCI or AD (20, 21). However, the relationship between elevated sTREM2 and inflammatory activity is unclear and is a critical piece of missing information needed to understand the role of sTREM2 in the broader immune response.

Since there is an association between TREM2 and AD and evidence of peripheral inflammatory factor alterations in AD, but little is known about the relationship between peripheral sTREM2 and peripheral inflammatory activity in AD, the aim of this study was to explore the relationship between plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory activity in AD. The hypothesis was that alterations in plasma sTREM2 are related to altered peripheral inflammatory activity in AD, in a stage specific manner as defined by mild cognitive impairment or AD pathological stage (ATN category).

Materials and Methods

Participant recruitment and study design.

Participants defined as cognitively normal (CN) controls (n=88), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI; n=37) and Alzheimer’s disease dementia (AD; n=75) donated biospecimens under the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease Biobank (LRCBH-Biobank) and the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (CADRC) protocols approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. Participants were all over 55 years of age. Venipunctures were performed after overnight fasting for the collection of whole blood. Plasma was isolated from lavender-top EDTA tubes and stored at −80°C. CSF was aliqouted into amber tubes and immediately frozen and stored at −80°C as previously described (22).

Neurological testing, diagnosis, and consensus:

All study participants underwent cognitive testing upon enrollment in Cleveland Clinic LRCBH-biobank or CADRC. The participants were reviewed by neurologists in a formal consensus panel to assign diagnostic groups. Only the groups CN (n=88), MCI without AD or other diagnoses (n=37) and AD dementia (n=75) were included in this study (Table 1). A subset of this group had both a blood draw and a lumbar puncture for collection of CSF for which AD-related biomarkers Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau (t-Tau), and phosphorylated-tau 181 (p-Tau) were measured for research studies (CN: n=33, MCI: n= 36, AD: n= 65) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort demographics, clinical chemistry, and AD-related biomarkers.

| CN |

MCI |

AD |

CN vs MCI |

CN vs AD |

MCI vs AD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Description | ||||||

| n = | 88 | 37 | 75 | |||

| Age range (years) | 55–84 | 55–83 | 56–86 | |||

| Average age (years) | 66.5 | 68.6 | 66.4 | 0.3576 | >0.9999 | 0.2091 |

| % Male | 44.3 | 59.5 | 49.3 | 0.1698 | 0.5332 | 0.3241 |

| % APOE4+ | 38.6 | 67.6 | 66.7 | 0.0035 | 0.0005 | >0.9999 |

| Clinical chemistry | ||||||

| Complete Blood Counts: n = | 49 | 33 | 60 | |||

| White Blood Cells mean (SD) | 5.5 (1.4) | 4.9 (1.1) | 6.0 (2.1) | 0.2234 | >0.9999 | 0.0239 |

| Neutrophil % mean (SD) | 60.7 (8.4) | 61.0 (9.1) | 62.5 (10.8) | >0.9999 | 0.5727 | >0.9999 |

| Lymphocyte % mean (SD) | 27.7 (6.8) | 26.9 (9.1) | 26.3 (8.9) | >0.9999 | 0.6040 | >0.9999 |

| Monocyte % mean (SD) | 8.3 (1.8) | 8.9 (1.8) | 8.5 (3.2) | 0.1540 | >0.9999 | 0.1069 |

| Basophil % mean (SD) | 0.53 (0.28) | 0.45 (0.23) | 0.39 (0.24) | 0.8922 | 0.0309 | 0.6943 |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate: n = | 48 | 33 | 59 | |||

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate Mean (SD) | 12.2 (9.1) | 7.5 (6.1) | 8.7 (6.0) | 0.0188 | 0.4160 | 0.3817 |

| C-reactive Protein: n = | 46 | 32 | 53 | |||

| C-reactive Protein Mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.0) | 3.8 (10.9) | 2.5 (4.7) | >0.9999 | >0.9999 | 0.7810 |

| Blood Brain Barrier Integrity: n = | 13 | 22 | 35 | |||

| Blood Brain Barrier Integrity Mean (SD) | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.5887 | >0.9999 | 0.1321 |

| AD-related Biomarkers (ATN) | ||||||

| n = | 33 | 36 | 65 | |||

| CSF AB 42/40 (A) mean (SD) | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.0007 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 |

| CSF pTau-181 (pg/ml) (T) mean (SD) | 51.5(25.8) | 97.5 (71.3) | 150.8 (111.8) | 0.0025 | <0.0001 | 0.0021 |

| CSF tTau (pg/ml) (N) mean (SD) | 482.2 (325.1) | 568.0 (407.9) | 763.0 (458.1) | 0.1987 | 0.0007 | 0.0085 |

The cohort was comprised of cognitively normal (CN), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) participants, ages 55–86 years. Age ranges and average ages per group are shown, and did not differ between groups by Kruskal-Wallis test. Proportions of male participants were similar between groups but APOE 4+ alleles were more prevalent in MCI and AD than CN (by Fisher’s exact test). AD showed significantly higher levels of WBC compared to MCI and lower basophil percentages compared to CN, while CN had higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates, compared to MCI (by Kruskal-Wallis). AD-related biomarkers were significantly different between disease groups. Significant differences are noted in bold.

Clinical testing:

Complete blood counts (CBC) were performed on n=49 CN, n=33 MCI, and n=60 AD participants via microscopy by trained Cleveland Clinic technicians blinded to sample group. Lumbar punctures were performed for the collection of CSF from a subset of these participants (CN: n=13, MCI: n= 22, AD: n= 35) to assess blood brain barrier integrity (Table 1). Blood and CSF samples were drawn on the same date in each participant to allow for direct comparison of clinical markers and study markers.

APOE genotyping:

Genotyping of apolipoprotein E (APOE) was performed from blood samples using the 7500 Real Time PCR System and TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (rs429358, rs7412) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described (23).

Plasma sTREM2:

Plasma soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) levels were measured using a Luminex 200 3.1 xPONENT System (EMD Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA) and a custom detection method designed to capture the soluble portion of TREM2 protein as previously described (24). The custom designed plasma sTREM2 assay uses Luminex xMap technology, a reliable and robust bead-based ELISA method, (25, 26) which has been published previously by our group (24, 27). Briefly, a capture antibody bound to MagPlex beads binds sTREM2 (R&D #MAB1828 human TREM2 antibody monoclonal mouse IgG2B Clone #263602; Immunogen His19-Ser174). A biotinylated antibody with a SAPE conjugate was used for detection (R&D: #BAF1828; human TREM2 biotinylated antibody; antigen affinity-purified polyclonal goat IgG; Immunogen His19-Ser174).

Plasma inflammatory markers:

A panel of 38 plasma inflammatory factors (cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) were measured with a human cytokine/chemokine panel utilizing Luminex 200 xMap technology and the MILLIPLEX MAP ® multiplex kit (Luminex xMAP technology; EMD Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA, kit HCYTMAG60PMX41BK) following the manufacturer’s instructions for analyte detection in human plasma. The Luminex xMAP assays are a bead-based ELISA and have been well validated in the past with documentation of reliability and repeatability. (25, 26, 28) This panel was selected because it included both previously-studied cytokines and cytokines without previous study with sTREM2 in AD. The inflammatory markers in the panel were: Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF-2), eotaxin, Transforming Growth Factor alpha (TGF-α), Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt-3L), Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF), Fractalkine (also known as CX3CL1), interferon (IFN) α2 (IFNα2), IFNγ, growth-regulated oncogene (GRO), interleukin (IL) 10, (IL-10), Monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP-3, also known as CCL7), IL-12 40kDa (IL-12p40), Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), IL-12 70kDa (IL-12P70), IL-13, IL-15, soluble CD40-ligand (sCD40L), IL-17A, IL-1 receptor agonist (IL-1RA), IL-1α, IL-9, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, interferon-gamma inducible protein 10kDa (IP-10), MCP-1 (also known as CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1α (MIP-1α also known as CCL3), MIP-1β (also known as CCL4), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha (TNFα), TNFβ, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF).

Quality control:

Plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory markers were measured in plasma on plates that also contained buffer-alone background wells and serial dilutions of analytes in order to generate a standard curve. Plates measuring inflammatory markers also contained quality control proteins. Each plate was evaluated to ensure that the standards and quality controls ran in the expected ranges. Samples from different disease groups were run across each plate to control for batch effects. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of analytes were calculated and averaged between duplicate samples. Our analyses compared MFI rather than calculated concentration because many participants had low levels of cytokines, which were undetectable by the standard curve interpolation. Utilization of MFI values allowed inclusion of all participants, including the samples at the low range of detection, to avoid biasing the results towards participants with higher values (29–31).

CSF biomarkers:

CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau (t-Tau), and phosphorylated-tau 181 (p-Tau) were measured according to manufacturer specifications (Luminex xMAP technology; EMD Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA: HNABTMAG-68K), modified by a 1:10 dilution of CSF. Each Aβ and Tau kit comes with an Aβ and Tau standard, as well as Aβ and Tau quality controls. The kit provides the expected concentrations of each working standard as well as each of the quality controls. The standards, controls, and CSF samples are all run in duplicate. If the coefficient of variation for any of the replicate wells is greater than 25% or if both replicate wells have a bead count of less than 35 beads for a given analyte, the results are repeated or excluded for that analyte.

ATN groups:

CSF measurements of Aβ40, Aβ42, t-Tau, and p-Tau were performed as described above. Participants were categorized into ATN groups based on the following criteria: A+ indicates participants were in the lower 10th percentile of all Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios within CN group in the cohort, T+ indicates participants were in the upper 90th percentile of all phosphorylated tau protein concentrations within the CN group in the cohort, and N+ indicates participants were in the upper 90th percentile of total tau protein concentrations within CN group in the cohort. Cutoff values generated by percentile analysis were as follows: A+ ≤ Aβ42/Aβ40 0.139; T+ p-Tau≥ 65.5pg/ml; N+ t-Tau ≥ 695.9pg/ml. These cutoff values were tested in contingency tables with numbers of CN and AD participants. The cutoffs were selected because they had the highest sensitivity and specificity in our cohort, compared to cutoffs set at 20th/80th percentiles, 15th/85th percentiles, and 5th/95th percentiles (for Aβ42/Aβ40, and p-Tau and T-Tau, respectively) as well as concentrations previously published (32–34). Using the 10th/90th percentiles and cutoffs listed above our cutoffs had Aβ42/Aβ40: sensitivity=0.963, specificity=0.901 (p<0.001 by Fisher’s exact test); p-Tau: sensitivity=0.722, specificity=0.887 (p<0.001 by Fisher’s exact test); and t-Tau: sensitivity=0.426, specificity=0.811 (p=0.0266 by Fisher’s exact test).

Plasma sTREM2 Tertiles:

We characterized participants into sTREM2 tertiles in order to compare groups with the highest versus lowest levels of plasma sTREM2. Levels of sTREM2 from participants were sorted from lowest to highest, regardless of disease status and ATN group, and the results were divided into three groups. Tertile 1 (n=67) refers to the lowest sTREM2 levels, and Tertile 3 (n=67) refers to the highest sTREM2 levels. Tertile 2 (n=66) was not included in the tertile analyses. Tertiles were used rather than quartiles or quintiles in order to maximize the sample size while still analyzing two distinct groups of sTREM2 levels.

Statistical Analyses:

CN, MCI, and AD demographics, plasma inflammatory marker, and plasma sTREM2 were compared between groups using Mann-Whitney, without and with outlier removal using the ROUT method (Q=1%). ATN groups were compared by Mann-Whitney tests along the ATN continuum (A−T−N− vs A+T−N−, A+T−N− vs A+T+N−, and A+T+N− vs A+T+N), without and with outlier removal using the ROUT method (Q=1%). The ROUT method using Q=1% indicates there is a 1% chance of incorrectly identifying outliers (false discovery rate). This method is appropriate for our relatively small sample size dataset, and has been published previously in both cytokine and Alzheimer’s disease research. (35, 36) Sensitivity and specificity of ATN group cutoffs were analyzed by Fisher’s exact tests and contingency tables of sTREM2 tertiles in disease groups were analyzed by Chi square tests. These data were analyzed, and violin plots and bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Using R (R version 3.6.1), the “lm” function was used to create a single linear regression model for each cytokine. The standardized beta coefficient was then obtained by applying the “standardize_parameters” function from the “effectsize” package to these models (37). The “cor” function was used to determine Spearman correlations. Correlograms were made using the resulting spearman correlation matrix with the “corrplot” function in the “corrplot” package (38) and arranged according to hierarchical clustering using the Ward’s method. The p-values were added using results from the “rcorr” function from the “Hmisc” function as a parameter in the corrplot function (39). To compare the graphs of correlation matrix, the Steiger test was applied to the correlation matrices with the “cortest.normal” function from the psych package (40). A power analysis utilizing analyte data from a small pilot study indicated a minimum sample size of n=25 per group was necessary to achieve a significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.8 for these analyses.

Co-expression network visualization:

A co-expression network was generated using data without outlier removal for each group based on the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient ρ. For inflammatory factors, Spearman r > 0.8 and p < 0.05 was used as cutoff for co-expressions; for sTREM2 vs. other inflammatory factors, Spearman r > 0 and p < 0.05 was used as a cutoff. The co-expression networks were visualized by Gephi 0.9.2 (41).

Results

Cohort demographics and clinical measurements

Characteristics of the study populations were compared between cognitively normal (CN) controls (n=88), individuals with MCI (n=37), and participants with AD (n=75). There were no statistically significant differences in age between groups by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. There were also no differences in distributions of male/female sex between groups by Fisher’s exact test. There were significant differences in APOE4+ allele status between groups (Table 1).

Peripheral blood cell counts were assessed in a subset of participants with available measures from Cleveland Clinic clinical chemistry. Participants with AD had significantly higher white blood cell counts compared to MCI (p=0.0239) and significantly lower basophil percentages compared to CN (p=0.0309). Participants with MCI had significantly lower erythrocyte sedimentation rates compared to CN (p=0.0188). Participants did not vary by percentages of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, levels of C-reactive protein, or blood brain barrier integrity (BBBi: ratio of CSF albumin/serum albumin) (Table 1).

A subgroup of the cohort had CSF measurements of Aβ42/40, p-Tau 181, and total Tau (CN n=33, MCI n=36, AD n=65). Significant differences were observed between all three disease groups in levels of AD-related biomarkers; Aβ42/40 and levels of p-Tau. Additionally, both CN and MCI groups had significantly lower levels of total Tau compared to the AD group (Table 1).

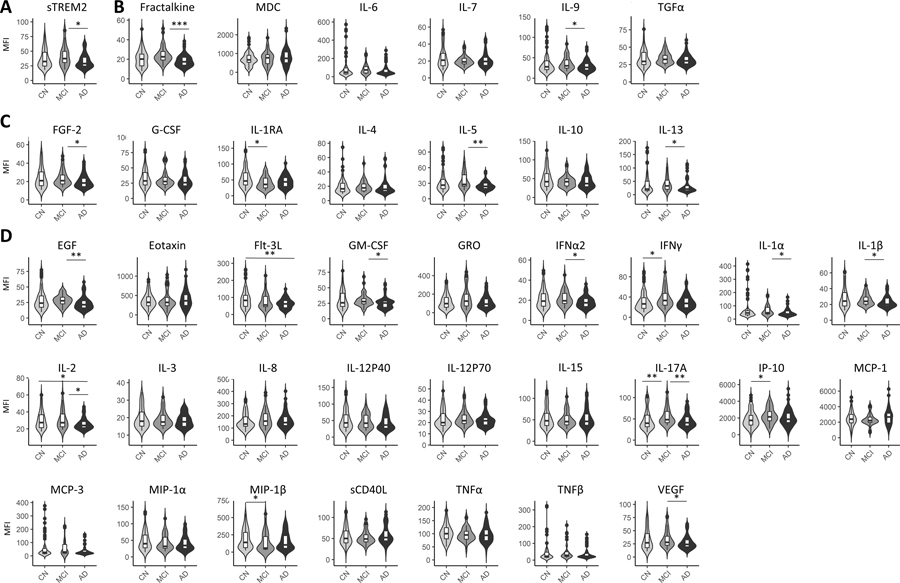

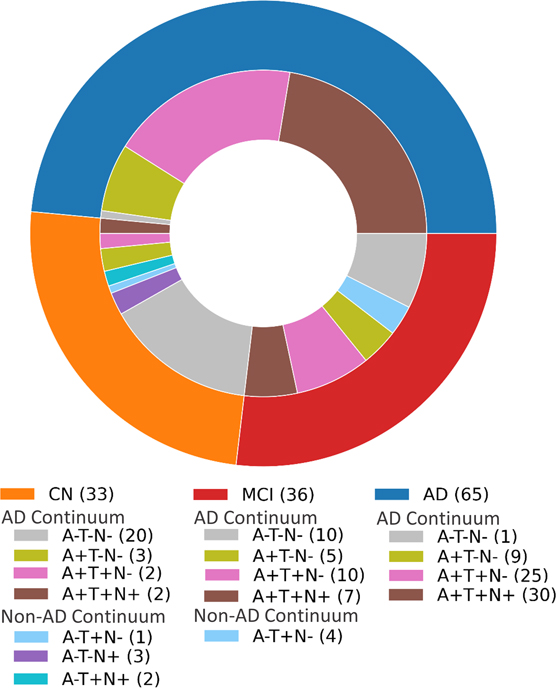

Levels of sTREM2 and multiple other inflammatory factors tend to be lower in AD, compared to MCI

Levels of sTREM2 were significantly higher in MCI compared to AD with outlier removal (Figure 1A) and without outlier removal (Table 2). Immunoregulatory/pleiotropic cytokines; fractalkine and IL-9, had significantly higher levels in MCI, compared to AD after outlier removal (Figure 1B). Anti-inflammatory factors; FGF-2, IL-1RA, IL-5 and IL-13, had significantly higher levels in MCI, compared to AD after outlier removal (Figure 1C). Pro-inflammatory factors; EGF, GM-CSF, IFNa2, IL-1a, IL-1B, IL-2, IL-17A, IP-10, and VEGF, had significantly higher levels in MCI, compared to AD after outlier removal (Figure 1D). Two inflammatory factors: Flt-3L, IL-2, were higher in controls, compared to AD and two; MIP-1B and IL-1RA were higher in controls, compared to MCI (Figure 1D). Results from Mann-Whitney analyses with or without outlier removal and the number of outliers removed are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1: Plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory factors by disease status.

Soluble TREM2 was significantly lower in AD, compared to MCI (A). Two immunoregulatory inflammatory factors, were significantly lower in AD, compared to MCI (B). Four anti-inflammatory factors exhibited significantly different levels by disease status (C). Twelve pro-inflammatory factors exhibited significantly different levels by disease status (D). Levels were compared between disease groups by Mann-Whitney tests. Here asterisks denote significance upon outlier removal. Outliers were removed per disease group for each inflammatory factor using the ROUT method. See Table II for p-values with and without outliers. P-value notations: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Table 2:

Inflammatory factor comparisons by disease status.

| CN (n = 88) vs MCI (n = 37) |

CN (n = 88) vs AD (n = 75) |

MCI (n = 37) vs AD (n = 75) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

Outliers n = |

With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

Outliers n = |

With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

Outliers n = |

|

| p-value |

p-value |

CN |

MCI |

p-value |

p-value |

CN |

AD |

p-value |

p-value |

MCI |

AD |

|

| sTREM2 | 0.1789 | 0.1454 | 7 | 3 | 0.2093 | 0.2295 | 7 | 5 | 0.0147 | 0.0119 | 3 | 5 |

| Immunoregulatory/ Pleiotropic | ||||||||||||

| Fractalkine | 0.1669 | 0.0594 | 13 | 5 | 0.1410 | 0.1672 | 13 | 10 | 0.0020 | 0.0004 | 5 | 10 |

| MDC | 0.7070 | 0.7215 | 2 | 1 | 0.2829 | 0.1780 | 2 | 0 | 0.7665 | 0.5945 | 1 | 0 |

| IL-6 | 0.6322 | 0.2132 | 19 | 6 | 0.5044 | 0.7164 | 19 | 16 | 0.2735 | 0.0617 | 6 | 16 |

| IL-7 | 0.9010 | 0.4481 | 8 | 7 | 0.2703 | 0.3057 | 8 | 6 | 0.3087 | 0.9332 | 7 | 6 |

| IL-9 | 0.7231 | 0.2419 | 19 | 6 | 0.3012 | 0.3940 | 19 | 15 | 0.1928 | 0.0394 | 6 | 15 |

| TGF-α | 0.9698 | 0.4488 | 18 | 5 | 0.4823 | 0.8445 | 18 | 13 | 0.4319 | 0.1864 | 5 | 13 |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||||||||||||

| FGF-2 | 0.6554 | 0.6436 | 11 | 5 | 0.2371 | 0.1425 | 11 | 10 | 0.0865 | 0.0378 | 5 | 10 |

| G-CSF | 0.9267 | 0.6094 | 6 | 5 | 0.3342 | 0.1624 | 6 | 7 | 0.3932 | 0.5226 | 5 | 7 |

| IL-1RA | 0.0259 | 0.0135 | 15 | 5 | 0.1268 | 0.0912 | 15 | 12 | 0.2790 | 0.2454 | 5 | 12 |

| IL-4 | 0.9096 | 0.5117 | 25 | 10 | 0.3082 | 0.7792 | 25 | 17 | 0.2761 | 0.2836 | 10 | 17 |

| IL-5 | 0.3249 | 0.1086 | 17 | 6 | 0.3875 | 0.2272 | 17 | 17 | 0.0583 | 0.0020 | 6 | 17 |

| IL-10 | 0.4870 | 0.5325 | 7 | 8 | 0.2418 | 0.2717 | 7 | 5 | 0.1249 | 0.8086 | 8 | 5 |

| IL-13 | 0.6870 | 0.1345 | 20 | 5 | 0.3292 | 0.4916 | 20 | 15 | 0.1556 | 0.0149 | 5 | 15 |

| Pro-inflammatory | ||||||||||||

| EGF | 0.7806 | 0.4391 | 13 | 4 | 0.1629 | 0.0782 | 13 | 12 | 0.0794 | 0.0079 | 4 | 12 |

| Eotaxin | 0.7435 | 0.8969 | 2 | 0 | 0.2534 | 0.3875 | 2 | 4 | 0.2423 | 0.4566 | 0 | 4 |

| Flt-3L | 0.2830 | 0.2530 | 5 | 2 | 0.0019 | 0.0035 | 5 | 2 | 0.3299 | 0.4405 | 2 | 2 |

| GM-CSF | 0.3550 | 0.5236 | 8 | 5 | 0.4507 | 0.1483 | 8 | 11 | 0.0657 | 0.0237 | 5 | 11 |

| GRO | 0.1834 | 0.1248 | 4 | 1 | 0.3839 | 0.9532 | 4 | 9 | 0.5547 | 0.1452 | 1 | 9 |

| IFNα2 | 0.1540 | 0.3670 | 6 | 5 | 0.4117 | 0.2105 | 6 | 8 | 0.0313 | 0.0332 | 5 | 8 |

| IFNγ | 0.1383 | 0.0309 | 15 | 5 | 0.5804 | 0.5229 | 15 | 6 | 0.0311 | 0.0616 | 5 | 6 |

| IL-1α | 0.6438 | 0.2491 | 20 | 8 | 0.2076 | 0.2110 | 20 | 17 | 0.1168 | 0.0144 | 8 | 17 |

| IL-1β | 0.9053 | 0.7152 | 14 | 5 | 0.1357 | 0.1322 | 14 | 11 | 0.1153 | 0.0457 | 5 | 11 |

| IL-2 | 0.9849 | 0.6751 | 11 | 3 | 0.0875 | 0.0246 | 11 | 11 | 0.1610 | 0.0223 | 3 | 11 |

| IL-3 | 0.6320 | 0.9046 | 6 | 5 | 0.4515 | 0.4264 | 6 | 5 | 0.2718 | 0.5539 | 5 | 5 |

| IL-8 | 0.9547 | 0.1494 | 24 | 5 | 0.6797 | 0.1880 | 24 | 12 | 0.7665 | 0.6226 | 5 | 12 |

| IL-12P40 | 0.8647 | 0.7260 | 8 | 4 | 0.1743 | 0.1942 | 8 | 6 | 0.3314 | 0.4355 | 4 | 6 |

| IL-12P70 | 0.4619 | 0.2479 | 15 | 6 | 0.8208 | 0.6931 | 15 | 10 | 0.2802 | 0.3291 | 6 | 10 |

| IL-15 | 0.9612 | 0.7523 | 7 | 4 | 0.5033 | 0.9437 | 7 | 2 | 0.7407 | 0.6897 | 4 | 2 |

| IL-17A | 0.0329 | 0.0093 | 12 | 5 | 0.9323 | 0.6512 | 12 | 9 | 0.0172 | 0.0087 | 5 | 9 |

| IP-10 | 0.0307 | 0.0272 | 2 | 1 | 0.1306 | 0.2131 | 2 | 4 | 0.2708 | 0.1573 | 1 | 4 |

| MCP-1 | 0.9720 | 0.5468 | 1 | 3 | 0.3625 | 0.2977 | 1 | 0 | 0.5693 | 0.1897 | 3 | 0 |

| MCP-3 | 0.9633 | 0.3574 | 20 | 5 | 0.3995 | 0.6953 | 20 | 15 | 0.5321 | 0.1774 | 5 | 15 |

| MIP-1α | 0.4125 | 0.3875 | 8 | 3 | 0.0698 | 0.0929 | 8 | 5 | 0.5567 | 0.6350 | 3 | 5 |

| MIP-1β | 0.1320 | 0.0360 | 3 | 3 | 0.4014 | 0.2661 | 3 | 4 | 0.3074 | 0.1514 | 3 | 4 |

| sCD40L | 0.7090 | 0.7127 | 5 | 2 | 0.5657 | 0.3393 | 5 | 2 | 0.3360 | 0.2063 | 2 | 2 |

| TNFα | 0.2086 | 0.2810 | 2 | 0 | 0.1248 | 0.1021 | 2 | 2 | 0.7453 | 0.5712 | 0 | 2 |

| TNFβ | 0.6890 | 0.0900 | 24 | 7 | 0.3930 | 0.9489 | 24 | 17 | 0.2253 | 0.0501 | 7 | 17 |

| VEGF | 0.3343 | 0.3162 | 9 | 4 | 0.4108 | 0.2705 | 9 | 9 | 0.0661 | 0.0282 | 4 | 9 |

Inflammatory factors levels were compared between cognitively normal controls, (CN), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Mann Whitney was utilized to test between group significant differences with and without outliers (p-values shown). Outlier tests were performed using the ROUT method (Q=1%). Number of outliers removed per group and per analyte are shown.

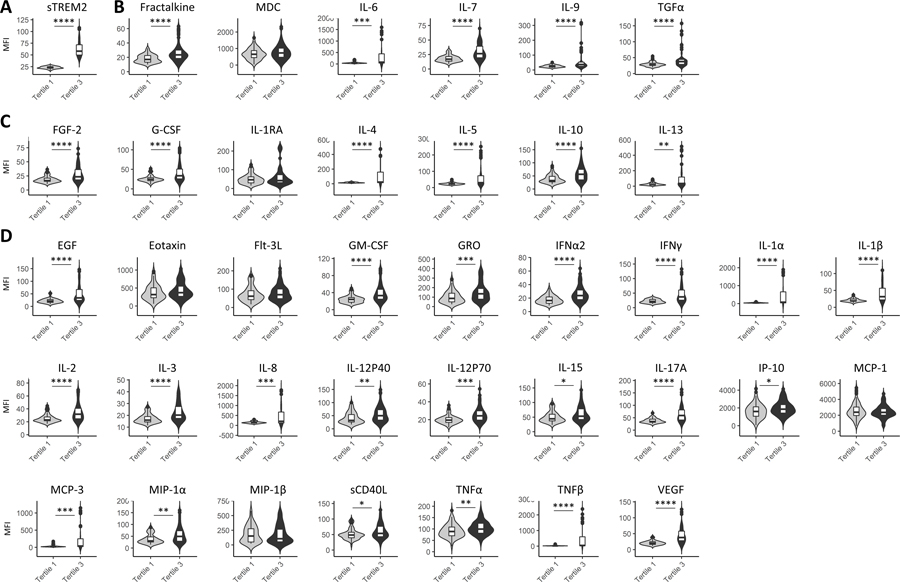

Regardless of disease status inflammatory factors tend to be higher in the high sTREM2 tertile

To determine if individuals with elevated sTREM2 also exhibit elevated levels of other inflammatory factors, the cohort was stratified by sTREM2 tertiles. This was done by ordering sTREM2 MFI levels from smallest to largest and evenly dividing them into three groups, regardless of disease status. Tertile 1 refers to the lowest sTREM2 levels and tertile 3 refers to the highest sTREM2 levels. Levels of cytokines between tertiles 1 and 3 with and without outlier removal exhibited significant differences between tertiles for 32 of the 38 inflammatory factors measured (upon outlier removal) (Figure 2, Table 3). The cytokines that were significantly higher in tertile 3 were immuneregulatory/pleiotropic cytokines fractalkine, IL-6, IL-7,IL-9, and TGFα (Figure 2B, Table 3), anti-inflammatory cytokines FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 (Figure 2C, Table 3) and pro-inflammatory cytokines EGF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-8, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, IL-17A, IP-10, MIP-1α, MCP-3, sCD40L, TNFα, TNFβ, and VEGF (Figure 2D, Table 3). Results from Mann-Whitney analyses with or without outlier removal and the number of outliers removed are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2: Inflammatory factors by sTREM2 tertile status.

sTREM2 Tertile 1 showed a range in sTREM2 MFI of 16.75–28.25, and Tertile 3 had a range of 43.0–108.0 MFI (A). The immunoregulatory/ pleiotropic factors that were significantly higher in the high sTREM2 tertile included: fractalkine, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, ad TGF-α (B). The anti-inflammatory factors that were significantly higher in the high sTREM2 tertile included: FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 (C). The pro-inflammatory factors that were significantly higher in the high sTREM2 tertile included: EGF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-8, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-15, IL-17A, IP-10, MCP-3, MIP-1α, sCD40L, TNFα, TNFβ, and VEGF (D). Levels were compared between sTREM2 Tertile 1 (low) and sTREM2 Tertile 1 (high) by Mann-Whitney tests after removal of outliers. Table 3 shows numbers of outliers removed per disease group for each cytokine using the ROUT method as well as significance between groups. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

Table 3:

Inflammatory factor comparisons by sTREM2 tertile status.

| sTREM2 Tertile 1 (n = 67) vs sTREM2 Tertile 3 (n = 67) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

||

| p-value |

p-value |

Tertile 1 |

Tertile 3 |

|

| sTREM2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 | 6 |

| Immunoregulatory/ Pleiotropic | ||||

| Fractalkine | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 8 | 10 |

| MDC | 0.2640 | 0.2543 | 1 | 1 |

| IL-6 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 12 | 14 |

| IL-7 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 6 | 8 |

| IL-9 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 15 | 18 |

| TGF-α | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 6 | 15 |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||||

| FGF-2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 7 | 9 |

| G-CSF | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 7 | 6 |

| IL-1RA | 0.0222 | 0.5532 | 4 | 15 |

| IL-4 | 0.0019 | 0.0001 | 17 | 10 |

| IL-5 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 13 | 14 |

| IL-10 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4 | 8 |

| IL-13 | 0.0004 | 0.0022 | 11 | 15 |

| Pro-inflammatory | ||||

| EGF | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 5 | 8 |

| Eotaxin | 0.1783 | 0.1514 | 3 | 3 |

| Flt-3L | 0.0827 | 0.2748 | 4 | 9 |

| GM-CSF | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 5 | 5 |

| GRO | 0.0113 | 0.0009 | 5 | 1 |

| IFNα2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4 | 5 |

| IFNγ | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 10 | 11 |

| IL-1α | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 15 | 8 |

| IL-1β | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 11 | 6 |

| IL-2 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 8 | 9 |

| IL-3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 4 | 3 |

| IL-8 | 0.0011 | 0.0006 | 10 | 8 |

| IL-12P40 | 0.0002 | 0.0038 | 4 | 12 |

| IL-12P70 | 0.0015 | 0.0002 | 12 | 13 |

| IL-15 | 0.0013 | 0.0114 | 2 | 8 |

| IL-17A | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 10 | 10 |

| IP-10 | 0.0203 | 0.0221 | 2 | 3 |

| MCP-1 | 0.8245 | 0.7016 | 1 | 2 |

| MCP-3 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 11 | 14 |

| MIP-1α | 0.0009 | 0.0031 | 4 | 8 |

| MIP-1β | 0.8920 | 1.0000 | 4 | 3 |

| sCD40L | 0.0201 | 0.0302 | 3 | 5 |

| TNFα | 0.0108 | 0.0078 | 2 | 2 |

| TNFβ | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 13 | 10 |

| VEGF | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 10 | 6 |

Inflammatory factors levels were compared between sTREM2 lower tertile 1 and upper tertile 3. Mann Whitney was utilized to test between group significant difference with and without outliers (p-values shown). Outlier tests were performed using the ROUT method (Q=1%). Number of outliers removed per group and per analyte are shown.

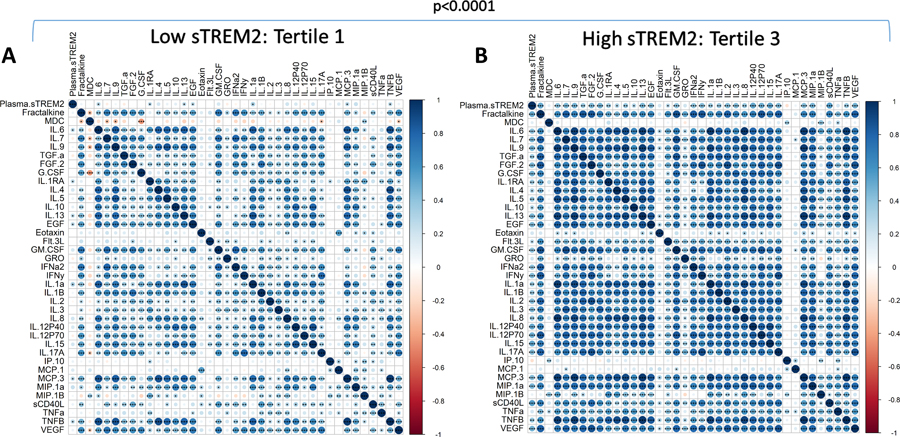

Correlation matrices were generated to characterize relationships between inflammatory factors in sTREM2 Tertile 1 (low) (Figure 3A) compared to Tertile 3 (high) (Figure 3B). The plots shown are without outlier removal. Outlier removal was not possible for correlation matrix analyses because of limitations in the software package since missing values resulted in the elimination of participants. The correlation patterns were very different between Tertile 1 and Tertile 3, shown visually by a color gradient of positive (blue) to negative (red) correlations, with white showing no correlation (Spearman r=0). Overall, Tertile 1 had fewer significant correlations than Tertile 3 including between sTREM2 and other inflammatory factors. Correlation matrices were compared by Steiger test and found to be significantly different (p<0.0001) (Figure 3). In a separate analysis that allowed for the removal of outliers, after outlier removal sTREM2 was correlated with each cytokine within tertiles. Tertile 1 (low sTREM2) did not significantly correlate with any of the 38 cytokines after outlier removal, while Tertile 3 (high sTREM2) had significantly positive correlations with 24 cytokines; Fractalkine, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-4, IL-5, EGF, GM-CSF, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-8, IL-12p40, IL-15, IL-17A, MIP-1α, sCD40L, TNFβ, and VEGF (Spearman correlation with and without outlier removal shown in Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 3: Inflammatory factor correlation matrices by sTREM2 tertile.

sTREM2 and each cytokine were correlated to each other in (A) sTREM2 Tertile 1 (n=67) and (B) sTREM2 Tertile 3 (n=67). Data used is without outlier removal (see Supplemental Table I for p-values with and without outlier removal). Steiger tests to compare matrices indicate significant differences between low and high sTREM2 tertiles. Correlation directions are shown by a color gradient; positive correlations are shown in blue and negative correlations are in red. Significant correlations are noted by displaying asterisks for p values. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

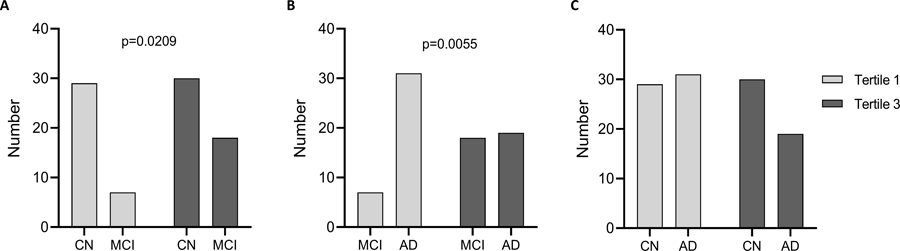

There were significantly higher proportions of CN in tertile 3 vs MCI and MCI in tertile 3 vs AD, but not CN vs AD by Fisher’s exact test, indicating CN and MCI represented a majority of the high sTREM2 values (Figure 4). When we compared the numbers of individuals in each disease group by sTREM2 tertiles, approximately half of the CN group was in tertile 3 and the other half in tertile 1 (Figure 4A). In contrast, a greater proportion of MCI were in tertile 3, compared to tertile 1 while MCI numbers were lower than CN in both tertiles (Figure 4A). MCI numbers were lower in tertile 1, but not in tertile 3, compared to AD (Figure 4B). Fewer AD were in Tertile 3, compared to tertile 1 while more MCI were in tertile 3, compared to tertile 1, and MCI had fewer than AD in tertile 1 (Figure 4B). There was not a significant distribution difference when comparing AD and CN by tertile (Figure 4C).

Figure 4: Number of individuals in each sTREM2 tertile.

CN, MCI, and AD participants were separated into tertiles based on low (Tertile 1) and high (Tertile 3) levels of plasma sTREM2. There were significantly different numbers of CN vs MCI (A), and MCI vs AD (B), but not CN vs AD (C) by Fisher’s exact test.

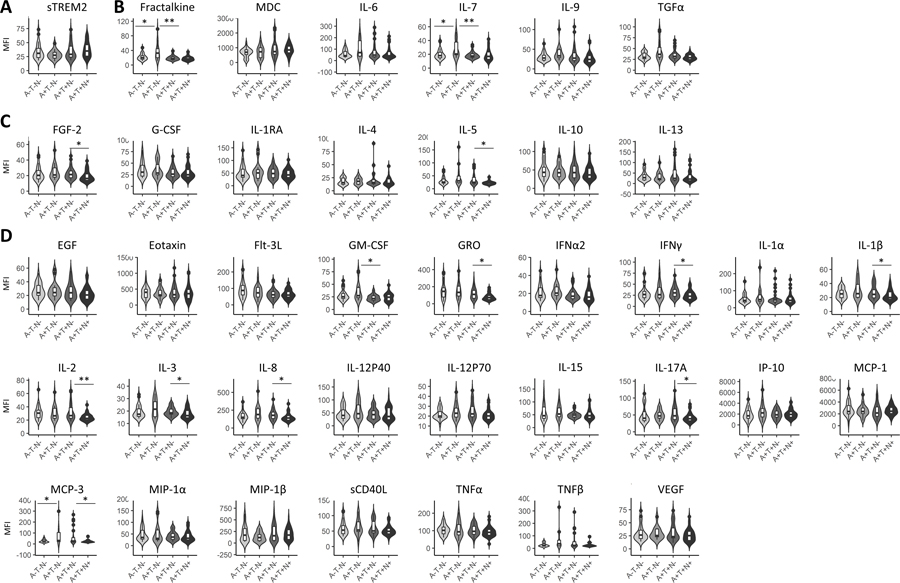

Levels of immunoregulatory/pleiotropic factors tend to be higher in A+T−N− while anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory factors tend to be higher in A+T+N−

Cutoff values of AD-related biomarkers were generated by percentile analysis (A+ ≤ Aβ42/Aβ40 0.139; T+ p-Tau≥ 65.5pg/ml; N+ t-Tau ≥ 695.9pg/ml: see methods section). The within CN, MCI and AD distribution of designated ATN categories according to these cutoff values are exhibited in a pie chart (Figure 5). Characteristics of the ATN continuum categories; A−T−N− (n=31), A+T−N− (n=17), A+T+N− (n=37), and A+T+N+ (n=39) indicate no significant differences in age, sex or APOE4 status (Table 4). There were 71 participants who could not be defined by ATN group because of the lack of CSF material available. There were no statistically significant differences in age (by Mann-Whitney tests) or gender (by Fisher’s exact test) between groups (Table 4). People in other ATN groups (n=10), such as A-T+N−, A−T−N+ and A−T+N+, were not included in further analyses (Figure 5). Upon stratification by ATN category, increased neutrophil counts in A+T−N−, compared to A−T−N−, and higher WBC counts in A+T−N− compared to both A−T−N− and A+T+N− were observed (Table 4).

Figure 5. ATN distribution within disease group:

Participants in each disease category with CSF AD-related biomarker data were classified into ATN groups.

Table 4.

Cohort demographics, clinical chemistry, and AD-related biomarkers by ATN status.

| A−T−N− |

A+T−N− |

A+T+N− |

A+T+N+ |

A−T−N− vs A+T−N− |

A+T−N− vs A+T+N− |

A+T+N− vs A+T+N+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Description | |||||||

| n= | 31 | 17 | 37 | 39 | |||

| Age range (years) | 55–79 | 56–76 | 55–84 | 56–86 | |||

| Average age (years) | 64.4 | 66.8 | 66.7 | 67.1 | 0.1167 | 0.7924 | 0.9320 |

| % Male | 64.5 | 70.6 | 54.1 | 38.5 | 0.7566 | 0.3723 | 0.3518 |

| % APOE4+ | 45.2 | 76.5 | 75.7 | 61.5 | 0.0666 | >0.9999 | 0.2224 |

| Clinical data sub-cohort | |||||||

| n= | 24 | 15 | 34 | 32 | |||

| White blood cell (WBC) mean (SD) | 5.20 (1.23) | 6.35 (1.28) | 5.59 (1.68) | 5.33 (1.24) | 0.0064 | 0.0358 | 0.8783 |

| Absolute Neutrophil Count mean (SD) | 3.22 (0.99) | 4.82 (2.24) | 3.37 (0.88) | 3.52 (1.20) | 0.0140 | 0.0660 | 0.7996 |

| Neutrophil % mean (SD) | 59.25 (10.09) | 64.35 (8.354) | 63.58 (7.98) | 60.91 (10.43) | 0.1018 | 0.5730 | 0.5257 |

| Absolute Lymphocyte Count mean (SD) | 1.44 (0.40) | 1.55 (0.42) | 1.32 (0.46) | 1.37 (0.46) | 0.5204 | 0.2002 | 0.8953 |

| Lymphocyte % mean (SD) | 28.2 (7.61) | 24.49 (8.36) | 25.39 (7.29) | 27.59 (9.55) | 0.1366 | 0.3577 | 0.5857 |

| Absolute Monocyte Count mean (SD) | 0.46 (0.11) | 0.50 (0.22) | 0.47 (0.12) | 0.46 (0.10) | 0.9792 | 0.8518 | >0.9999 |

| Monocyte % mean (SD) | 8.56 (1.17) | 7.94 (1.18) | 7.97 (1.95) | 8.92 (1.84) | 0.1120 | 0.8342 | 0.0737 |

| Absolute Basophil Count mean (SD) | 0.022 (0.014) | 0.028 (0.012) | 0.023 (0.014) | 0.022 (0.012) | 0.1378 | 0.2307 | 0.8100 |

| Basophil % mean (SD) | 0.50 (0.32) | 0.38 (0.23) | 0.42 (0.23) | 0.43 (0.21) | 0.2565 | 0.5845 | 0.8543 |

| n= | 21 | 15 | 34 | 32 | |||

| Sedimentation rate Mean (SD) | 7.7 (4.68) | 5.8 (2.18) | 8.24 (4.89) | 7.3 (3.75) | 0.1842 | 0.0986 | 0.5796 |

| n= | 23 | 13 | 31 | 32 | |||

| C-reactive protein (CRP) Mean (SD) | 1.35 (1.21) | 1.22 (0.87) | 1.38 (1.04) | 0.90 (0.74) | 0.9636 | 0.6961 | 0.0538 |

| n= | 14 | 8 | 19 | 23 | |||

| Blood Brain Barrier Integrity Mean (SD) | 0.005 (0.002) | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.006 (0.002) | 0.008 (0.004) | 0.7639 | 0.7975 | 0.1647 |

| CSF ATN | |||||||

| CSF AB 42/40 (A) mean (SD) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | <0.0001 | 0.2759 | 0.2466 |

| CSF pTau-181 (pg/ml) (T) mean (SD) | 37.1 (13.4) | 48.4 (9.5) | 113.1 (37.8) | 205.2 (123.0) | 0.0033 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| CSF tTau (pg/ml) (N) mean (SD) | 298.7 (136.0) | 324.3 (111.1) | 504.9 (114.5) | 1150.1 (400.5) | 0.4441 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

A subset of participants with available CSF measures of AD-related biomarkers; Aβ42/40, p-Tau181 and t-Tau were classified into ATN groups. Characteristics of the study populations were compared between groups defined by the ATN Continuum: A−T−N− (n=31), A+T−N− (n=17), A+T+N− (n=37), and A+T+N+ (n=39). Cutoff for positive ATN values were Aβ42/40 <0.139 (A+), p-Tau181 >65.5 (T+), and t-Tau >695.9 (N+). There were significant differences in WBC and Neutrophil count between groups. There were no statistically significant differences in age (by Mann-Whitney tests), sex (by Fisher’s exact test) or APOE4 status between groups. Significant differences are noted in bold.

Levels of sTREM2 and inflammatory factors were compared between ATN categories. To focus on designations related to AD stage (6), we analyzed only participants defining the AD-related ATN continuum: A−T−N−, A+T−N−, A+T+N, or A+T+N+ (124 participants out of 200 in the total cohort). Groups were compared by Mann-Whitney tests after outlier removal (A−T−N− vs A+T−N−, A+T−N− vs A+T+N−, and A+T+N− vs A+T+N+). Levels of sTREM2 did not significantly differ between ATN groups after outlier removal (Figure 6A) or without outlier removal (Table 5). Levels of immunoregulatory/pleiotropic cytokines fractalkine and IL-7 were significantly higher in the A+T−N− group compared to the A−T−N− and A+T+N− groups after outlier removal (Figure 6B). The A+T+N+ group had significantly lower levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines FGF-2 and IL-5 compared to the A+T+N− group after outlier removal (Figure 6C). Similarly, levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines GM-CSF, GRO, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-8, IL-17A, and MCP-3, were significantly lower in A+T+N+ compared to A+T+N− after outlier removal (Figure 6D). In addition, higher levels of MCP-3 were observed in A+T−N, compared to A−T−N− after outlier removal (Figure 3D). Results from Mann-Whitney analyses with or without outlier removal and the number of outliers removed are in Table 5.

Figure 6: Plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory factors by ATN status. Levels of sTREM2 were not different between ATN categories (A).

The immunoregulatory/pleiotropic factor, fractalkine, was significantly higher in the A+T−N−, compared to A−T−N− and A+T+N. IL-7 was significantly higher in the A+T−N− group, compared to A−T−N− and A+T+N− (B). The anti-inflammatory factors, FGF-2 and IL-5 were significantly higher in A+T+N−, compared to A+T+N+ (C). The pro-inflammatory factors GRO,, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-8, IL-17A and MCP-3 are lower in A+T+N+, compared to A+T+N−, while GM-CSF is lower in A+T+N−, compared to A+T−N−, and MCP-3 is higher in A+T−N−, compared to A−T−N− (D). Levels were compared between A−T−N− vs. A+T−N−, A+T−N− vs A+T+N−, and A+T+N− vs A+T+N+ by Mann-Whitney tests. Asterisks denote significance upon outlier removal. Outliers were removed per ATN group for each inflammatory factor using the ROUT method. See Table V for p-values with and without outliers. P-value notations: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Table 5:

Inflammatory factor comparisons by ATN status.

| A−T−N− (n = 31) vs A+T−N− (n = 17) |

A+T−N− (n = 17) vs A+T+N− (n = 37) |

A+T+N− (n = 37) vs A+T+N+ (n = 39) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

With Outliers |

Without Outliers |

Outliers n = |

||||

| p-value |

p-value |

A−T−N− |

A+T−N− |

p-value |

p-value |

A+T−N− |

A+T+N− |

p-value |

p-value |

A+T+N− |

A+T+N+ |

|

| sTREM2 | 0.2621 | 0.2995 | 4 | 1 | 0.4285 | 0.3854 | 1 | 3 | 0.3209 | 0.1855 | 3 | 2 |

| Immunoregulatory/ Pleiotropic | ||||||||||||

| Fractalkine | 0.1106 | 0.0211 | 3 | 0 | 0.0472 | 0.0023 | 0 | 6 | 0.1499 | 0.3327 | 6 | 3 |

| MDC | 0.8982 | 0.7507 | 1 | 0 | 0.3089 | 0.3089 | 0 | 0 | 0.7099 | 0.7099 | 0 | 0 |

| IL-6 | 0.2400 | 0.1709 | 6 | 4 | 0.4619 | 0.3207 | 4 | 8 | 0.5060 | 0.5247 | 8 | 8 |

| IL-7 | 0.1516 | 0.0171 | 5 | 1 | 0.0831 | 0.0039 | 1 | 7 | 0.2010 | 0.4772 | 7 | 4 |

| IL-9 | 0.0906 | 0.0839 | 5 | 4 | 0.2296 | 0.1054 | 4 | 8 | 0.1006 | 0.0830 | 8 | 7 |

| TGF-α | 0.2956 | 0.0874 | 4 | 1 | 0.5325 | 0.2123 | 1 | 5 | 0.2890 | 0.0843 | 5 | 7 |

| Anti-inflammatory | ||||||||||||

| FGF-2 | 0.4249 | 0.3057 | 4 | 2 | 0.8303 | 0.5978 | 2 | 6 | 0.0476 | 0.0246 | 6 | 5 |

| G-CSF | 0.9570 | 0.9622 | 2 | 1 | 0.4285 | 0.2324 | 1 | 4 | 0.5746 | 0.8599 | 4 | 2 |

| IL-1RA | 0.3885 | 0.5662 | 3 | 3 | 0.7728 | 0.9809 | 3 | 5 | 0.3577 | 0.4217 | 5 | 4 |

| IL-4 | 0.6741 | 0.8931 | 7 | 5 | 0.9629 | 0.9294 | 5 | 9 | 0.4234 | 0.3338 | 9 | 10 |

| IL-5 | 0.2443 | 0.2316 | 4 | 3 | 0.2758 | 0.2719 | 3 | 5 | 0.1992 | 0.0404 | 5 | 8 |

| IL-10 | 0.4376 | 0.6969 | 4 | 1 | 0.9777 | 0.9007 | 1 | 3 | 0.5961 | 0.4459 | 3 | 4 |

| IL-13 | 0.7792 | 0.9452 | 4 | 3 | 0.8595 | 0.7873 | 3 | 6 | 0.2728 | 0.2090 | 6 | 6 |

| Pro-inflammatory | ||||||||||||

| EGF | 0.8971 | 0.9015 | 4 | 3 | 0.6085 | 0.6413 | 3 | 6 | 0.2011 | 0.2243 | 6 | 5 |

| Eotaxin | 0.8478 | 0.9913 | 1 | 0 | 0.4619 | 0.9103 | 0 | 4 | 0.2137 | 0.6370 | 4 | 0 |

| Flt-3L | 0.1710 | 0.2899 | 2 | 0 | 0.4733 | 0.2789 | 0 | 2 | 0.8638 | 0.8261 | 2 | 2 |

| GM-CSF | 0.8885 | 0.4536 | 3 | 0 | 0.4674 | 0.0134 | 0 | 9 | 0.4448 | 0.6984 | 9 | 4 |

| GRO | 1.0000 | 0.8507 | 1 | 0 | 0.7586 | 0.2152 | 0 | 5 | 0.0432 | 0.0109 | 5 | 6 |

| IFNα2 | 0.3317 | 0.2803 | 2 | 1 | 0.3234 | 0.0671 | 1 | 6 | 0.1116 | 0.3585 | 6 | 2 |

| IFNγ | 0.8631 | 0.7363 | 6 | 3 | 0.9258 | 0.7183 | 3 | 4 | 0.1291 | 0.0312 | 4 | 6 |

| IL-1α | 0.4065 | 0.4148 | 6 | 4 | 0.6020 | 0.4793 | 4 | 8 | 0.7083 | 0.7786 | 8 | 8 |

| IL-1β | 0.3943 | 0.2644 | 4 | 2 | 0.4284 | 0.3793 | 2 | 4 | 0.1278 | 0.0461 | 4 | 5 |

| IL-2 | 0.8800 | 0.7694 | 3 | 2 | 0.9851 | 0.8197 | 2 | 3 | 0.1252 | 0.0092 | 3 | 7 |

| IL-3 | 0.8292 | 0.2885 | 4 | 0 | 0.7093 | 0.2683 | 0 | 4 | 0.0118 | 0.0362 | 4 | 1 |

| IL-8 | 0.3008 | 0.1722 | 4 | 2 | 0.9406 | 0.5392 | 2 | 7 | 0.0682 | 0.0445 | 7 | 6 |

| IL-12P40 | 0.6124 | 0.2513 | 3 | 0 | 0.3663 | 0.2013 | 0 | 2 | 0.9090 | 0.7605 | 2 | 3 |

| IL-12P70 | 0.2574 | 0.2878 | 6 | 4 | 0.5326 | 0.9800 | 4 | 5 | 0.1484 | 0.1158 | 5 | 5 |

| IL-15 | 0.8630 | 0.7148 | 1 | 0 | 0.7444 | 0.3205 | 0 | 4 | 0.3260 | 0.4986 | 4 | 2 |

| IL-17A | 0.5460 | 0.6109 | 4 | 3 | 0.9554 | 0.6761 | 3 | 5 | 0.0386 | 0.0313 | 5 | 4 |

| IP-10 | 0.3042 | 0.3042 | 0 | 0 | 0.5672 | 0.4554 | 0 | 1 | 0.6419 | 0.9153 | 1 | 3 |

| MCP-1 | 0.7009 | 0.7009 | 0 | 0 | 0.5926 | 0.5926 | 0 | 0 | 0.1880 | 0.2518 | 0 | 1 |

| MCP-3 | 0.1957 | 0.0292 | 7 | 2 | 0.6348 | 0.2784 | 2 | 7 | 0.3059 | 0.0480 | 7 | 11 |

| MIP-1α | 0.6124 | 0.7326 | 3 | 1 | 0.8889 | 0.9337 | 1 | 3 | 0.6512 | 0.4714 | 3 | 4 |

| MIP-1β | 0.9142 | 0.4121 | 0 | 2 | 0.4178 | 0.2686 | 2 | 3 | 0.5853 | 0.9559 | 3 | 0 |

| sCD40L | 0.6430 | 0.5065 | 1 | 0 | 0.7094 | 0.5870 | 0 | 1 | 0.1685 | 0.1565 | 1 | 1 |

| TNFα | 0.7489 | 0.7489 | 0 | 0 | 0.9554 | 0.9554 | 0 | 0 | 0.2104 | 0.2104 | 0 | 0 |

| TNFβ | 0.1579 | 0.0562 | 7 | 4 | 0.5266 | 0.3409 | 4 | 8 | 0.5295 | 0.2100 | 8 | 11 |

| VEGF | 0.5604 | 0.8966 | 4 | 4 | 0.3966 | 0.8166 | 4 | 4 | 0.3940 | 0.2562 | 4 | 5 |

Inflammatory factors levels were compared between ATN categories. Mann Whitney was utilized to test significant differences between group with and without outliers (p-values shown). Outlier tests were performed using the ROUT method (Q=1%). Number of outliers removed per group and per analyte are shown.

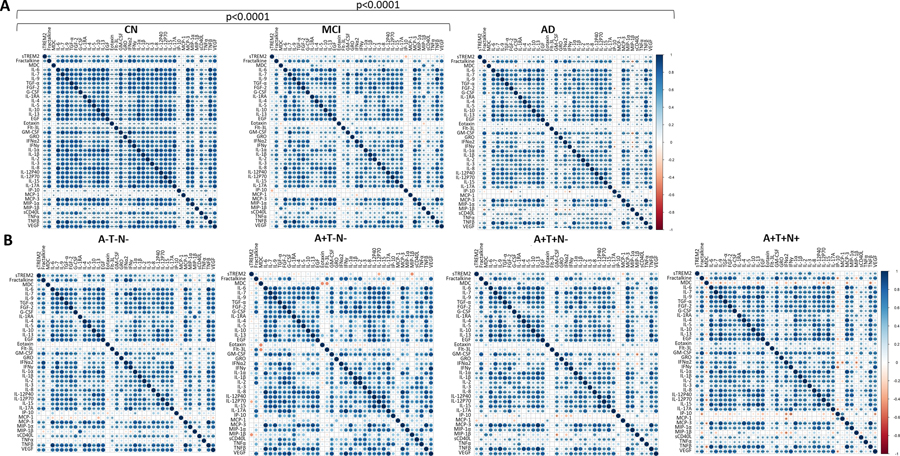

Inflammatory factor correlation landscapes are significantly different between disease groups

Correlation matrices were generated to characterize relationships between inflammatory factors by disease status (Figure 7A) or ATN status (Figure 7B) on all 39 inflammatory factors (sTREM2 and 38 cytokines). Outlier removal was not possible for correlation matrix analyses because of limitations in the software package since missing values resulted in the elimination of participants. A Steiger test to compare correlation landscapes indicates that the CN group was significantly different than both the MCI and AD groups (p<0.0001) (Figure 7A) while there was no difference between ATN groups (Figure 7B).

Figure 7: Inflammatory factor correlation matrices by disease and ATN status.

Plasma sTREM2 and each inflammatory factor were correlated to each other within disease groups (CN: n=88, MCI: n=37, AD: n=75 (A) and ATN groups (A−T−N−: n=31, A+T−N−: n=17, A+T+N− n=37, A+T+T+: n=39) (B). Spearman correlations for these correlation matrices were performed without outlier removal (see Supplemental Table III for p-values with and without outliers removed). Steiger tests to compare matrices were performed and significant differences were identified for CN verses MCI (p<0.0001) and CN verses AD (p<0.0001). Correlation directions are shown by a color gradient; positive correlations are shown in blue and negative correlations are red. Significant correlations are noted by displaying asterisks for p values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

CN showed significant positive correlations between sTREM2 and 34 of the 38 inflammatory factors (the exceptions were eotaxin, MDC, MCP-1 and MIP-1β) (Figure 7A). After outlier removal Fractalkine, IL-7, TGF- α, FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-10, EGF, GM-CSF, IFNα2, IFNy, IL-2, IL-17A, IP-10, MIP-1α, sCD40L, TNF-α and VEGF remained significant (Supplemental Table 2). This was in contrast to the MCI group, in which sTREM2 significantly correlated with only IL-10, EGF, IL-1α and IL-1β before outlier removal (Figure 7A) and none remained significant after outlier removal (Supplemental Table 2). In the AD group, sTREM2 significantly correlated with 12 of the 38 inflammatory factors; IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-13, EGF, IFNy, IL-1β, IL-3, MCP-3 and MIP-1β (Figure 7A), five of which remained significant after outlier removal; IL-10, EGF, IL-1β, IL-3 and VEGF (Supplemental Table 2).

The A−T−N− had significant positive correlations between sTREM2 and multiple inflammatory factors, including Fractalkine, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, TGFα, FGF-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, EGF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-8, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-17A, MCP-3, TNFβ, and VEGF (Figure 7B). Only two of these inflammatory factors remained significant (IL-5, EGF) and two others gained significance (MDC, IP-10) after outlier removal (Supplemental Table 3). In the A+T−N− group there were no significant correlations between sTREM2 and inflammatory factors (Figure 7B) unless outliers were removed; IL-4, IL12p70 (Supplemental Table 3). The A+T+N− group exhibited significant correlations between sTREM2 and IL-6, IL-9, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, EGF, IL-1α, IL-1β, MCP-3, and TNFβ (Figure 7B) while after outlier removal TGFα gained significance, and IL-10, EGF and IL-1β remained significant (Supplemental Table 3). A+T+N+ showed positive correlations between sTREM2 and IL-6, IL-7, TGFα, FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-1RA, EGF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-12p70, IL-17A, TNFβ and VEGF (Figure 7B) while after outlier removal only IL-7, FGF-2, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IL-1β and IL-3 remained significant (Supplemental Table 3).

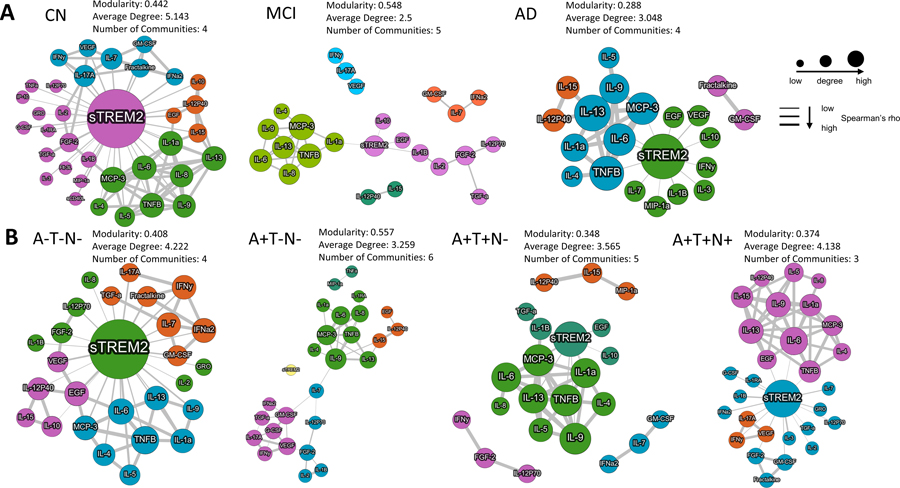

Inflammatory factor networks are altered at the MCI and A+T−N− stages

To estimate the complexity of the relationship between inflammatory factors, a network analysis was performed (without outlier removal) (Figure 8). The CN group exhibited a large sTREM2 node at the center of the module representing the most connections to other cytokines with an overall modularity of 0.442 and four communities (each community shown as a different color) (Figure 8A). In contrast, the MCI group showed a very sparse network where only four cytokines connected to sTREM2 and the modularity (0.548) and number of communities was increased (5 communities). The AD group exhibited the lowest modularity with more cytokines connected to sTREM2, and four communities. The MCI and AD groups also showed networks of inflammatory factors that were not connected to sTREM2, while the CN group did not (Figure 8A). The A−T−N− network analysis showed a large sTREM2 node and a modularity of 0.408 with four communities (Figure 8B). In contrast, the A+T−N− group exhibited no sTREM2 connections and the modularity was increased (0.557) and the number of communities increased to six (Figure 8B). A+T+N− and A+T+N+ both had lower modularity than A−T−N− and A+T−N−, while A+T+N− showed networks of inflammatory factors that were not connected to sTREM2 (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Inflammatory factor networks by disease and ATN status.

Upon stratification by clinical diagnosis, a large sTREM2 node was observed in CN with connections to multiple inflammatory factors, while there were fewer connections in MCI and AD as exhibited by the modularity, average degree and number of communities (A). Upon stratification by ATN, a large sTREM2 hub was observed in A−T−N−, which was absent in A+T−N−. The differences between ATN categories is also exhibited by differences in the modularity, average degree and number of communities. A large sTREM2 node was observed in A+T+N− and A+T+N+ where interconnectedness with sTREM2 was different than other ATN categories (B). Inclusion of inflammatory factors was based on Spearman r>0.8 and p<0.05. Inclusion of sTREM2 was based on p<0.05 without regard to Spearman r values. Node size and thickness of lines are related to levels of Spearman rho. Modularity is an indicator of the complexity of the networks. Average degree is an indicator of the how many of the nodes are connecting with other nodes. Communities are highlighted as one color and is a function of stronger and more frequent connections.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between plasma sTREM2 and inflammatory activity in AD. We sought to accomplish this by comparing plasma sTREM2 and plasma inflammatory factors across clinical or ATN categories.

Multiple cytokines exhibited a decrease in AD, compared to MCI, which is in contrast to previous studies that have observed both no difference or an increase in AD (14, 21) suggesting that heterogeneity in pathological stage across cohorts could contribute to the discrepancy across studies. For example, our cohort was assembled from biobanked samples collected in a dementia clinic and is not representative of the general population, including the CN group. To address the question of whether our CN and MCI sub-cohorts had underlying early stage pathology, a sub-cohort with CSF ATN measures was assessed. Indeed, the CN group included individuals with underlying neurological pathologies as indicated by their ATN status. Therefore, to address the question of whether heterogeneity in AD-related ATN pathology is associated with a decrease in cytokine levels, the cohort was stratified by ATN status. Three cytokines, Fractalkine, IL-7 and MCP-3, were significantly elevated in the A+T−N− stage, compared to A−T−N− suggesting that the A+ stage is a critical timepoint in the immune response in AD. Fractalkine can act as a chemoattractant for leukocytes and has been described as elevated in MCI (42). MCP-3 is also a chemoattractant for leukocytes and has been described as either elevated in AD or without a significant difference in AD (14). IL-7 regulates the development and homeostasis of immune cells, including B and T cells and has been somewhat inconsistently associated with AD (8, 43, 44). Together, this suggests that cell recruitment and development may play an important role in early stage AD. Multiple other cytokines exhibited decreased levels in the later A+T+N− or the A+T+N+ stages of AD, suggesting that there is potential peripheral immunosenescence in the later A+T+N− or the A+T+N+ stages of AD. This idea is supported by previous reports of age-related decline in immune function and in AD (45, 46).

Comparisons between sTREM2 tertiles regardless of disease or ATN status, indicates that when plasma sTREM2 is elevated many other inflammatory factors in the circulation are also elevated. Tertile 3 (high sTREM2) had significantly higher levels of 31 cytokines while tertile 1 did not have higher levels of any cytokine. In addition, inflammatory activity matrices were significantly different between tertiles and MCI is disproportionally in tertile 3 while AD is in tertile 1, further implicating TREM2-related inflammatory activity as playing a key role in early stage AD, while this role changes later in the disease. An early stage elevation of CSF sTREM2 has been associated with protection against cognitive decline (47, 48). In contrast, CSF sTREM2 is associated with cognitive decline in the later stages of AD (47, 48). Here we observed elevation of multiple inflammatory factors in the peripheral circulation that corresponds with elevated plasma sTREM2 in the MCI stage. Together, this implicates alterations in TREM2 function in the early stages of cognitive decline as a critical player in a broader potentially systemic immune response in AD.

An association between sTREM2 and inflammatory factors was observed that was different in the CN and A−T−N− groups compared to the other groups defined by AD symptoms (MCI and AD) or AD-related CSF biomarker categories (A+T−N−, A+T+N−, and A+T+N+). Overall, patterns of inflammatory activity and the relationship with sTREM2 was drastically altered in early stage AD (MCI and A+T−N− or A+T+N−), and remains altered in the later-stages of AD (AD and A+T+N+), although less so, suggesting that dysfunctional peripheral TREM2-related inflammatory activity plays a critical role early in disease progression especially at the MCI and A+T−N− stage. Although, increased expression of TREM2 in peripheral cells from MCI patients has been described previously, (49, 50) peripheral sTREM2 has been described either only modestly elevated (20, 21) or as not significantly elevated in AD (51). In contrast to previous findings, we observed a significant difference in plasma sTREM2 between MCI and AD where levels were decreased in AD and a non-significant elevation was observed in MCI, compared to CN. An association between elevated plasma sTREM2 and cognitive impairment after acute ischemic stroke and all-cause dementia has been described (52–54) suggesting that underlying heterogeneity may contribute to observed differences across study cohorts. Higher CSF sTREM2 has been described as attenuating APOE4-related risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration suggesting that central nervous system early elevation of TREM2 plays a critical role in AD progression (55). In addition, studies in mouse models suggest that TREM2 function impedes tau seeding in neuritic plaques (56) and potentially restrains the enhancement of tau accumulation and neurodegeneration initiated by β-amyloid pathology in the brain (57). In our study, after stratification by CSF ATN categories, plasma sTREM2 did not differ by ATN implicating other pathologies rather than amyloid and tau as contributing to higher sTREM2 levels in MCI. However, in support of a possible role of dysfunctional sTREM2 in early ATN, the correlation and network analyses show a complete lack of correlation with other inflammatory factors in the A+T−N− stage suggesting that early stage AD is a critical timepoint.

Interestingly, there were instances where there was not a relationship between sTREM2 and inflammatory factors. The four inflammatory factors that did not correlate significantly with sTREM2 in the CN group (eotaxin, MDC, MIP-1β, and MCP-1), did not significantly correlate in the MCI and AD group either, and were not different between sTREM2 tertiles suggesting that those inflammatory factors are not associated with sTREM2 in this cohort even though previous evidence suggests they are altered in AD (58, 59). Interestingly, MDC did correlate with sTREM2 in the A−T−N− group (Figure 9D–E) suggesting that in individuals negative for AD-related biomarkers, there is a relationship between MDC and sTREM2.

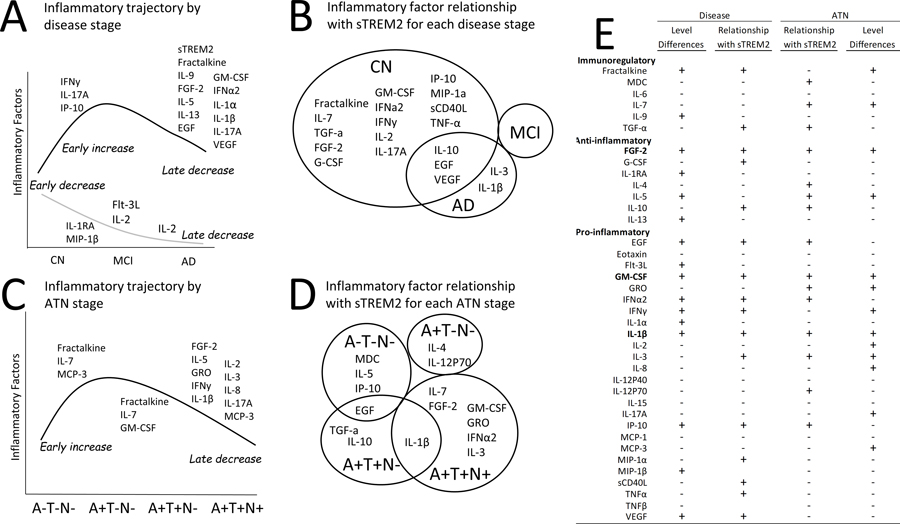

Figure 9. Summary of altered inflammatory factor levels and altered inflammatory factor relationships with sTREM2 in AD.

After outlier removal some inflammatory factors exhibited an early increase in the MCI stage (IFNy, IL-17A, IP10) while several were decreased later in the AD stage including sTREM2 (black line). Other inflammatory factors exhibited an early decrease (IL-1RA, MIP-1B) (grey line) while two inflammatory factors were significantly lower in the later AD stage compared to controls (Flt-3L, IL-2) or also in MCI compared to AD (IL-2) (grey line) (A). After outlier removal several inflammatory factors were uniquely significantly correlated with sTREM2 in the control group. Inflammatory factors significantly correlated with sTREM2 in controls, none in MCI, and five in AD (IL-10, EGF, VEGF, IL-3, IL-1B) and two were unique to AD (IL-3, IL-1B) (B). After outlier removal a few inflammatory factors were significantly increased in A+T−N−,compared to A−T−N− (Fractalkine, IL-7, MCP-3) and/or exhibited a decrease in the A+T+N− stage, compared to A+T−N− (Fractalkine, IL-7, GM-CSF) while several other inflammatory factors were significantly decreased later in the A+T+N+, compared to A+T+N− stage (C). After outlier removal individuals without AD-pathology (A−T−N−) uniquely exhibited significant correlations between sTREM2 and three inflammatory factors; MDC, IL-5, IP-10, while EGF was shared with A+T+N−. IL-4 and IL-12P70 were unique to the A+T−N− stage and TGF-α and IL-10 were unique to the A+T+N− stage while IL-1β overlapped with A+T+N+ and six were unique to the A+T+N+ group; IL-7, FGF2, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2 and IL-3 (D). Multiple inflammatory factors were either positive (+) or negative (−) for significant differences in levels or the relationship with sTREM2 by disease or ATN status. Only FGF-2, GM-CSF and IL-1β were positive for all four categories (E).

Three cytokines stood out as potentially important in AD since they had both significantly different levels between groups (both disease and ATN groups) and a significant relationship with sTREM2 in at least one group implicating a role in a systemic immune response in AD. These inflammatory factors were FGF-2, GM-CSF and IL-1β. Fractalkine also stood out because it was increased in the early A+T−N− stage and decreased in the late stages of AD while also correlated with sTREM2 in cognitively normal individuals implicating an early alteration in the normal relationship between sTREM2 and Fractalkine (Figure 9).

FGF-2 levels were decreased in AD and in the A+T+N+ individuals. It was positively correlated with sTREM2 only in CN and A+T+N+. When sTREM2 is elevated FGF-2 is also elevated (Figure 9). FGF-2, also known as basic fibroblast growth factor, is a growth factor and signaling protein that binds to and exerts effects via specific fibroblast growth factor receptors. It is involved in various cellular functions regulating proliferation, differentiation, survival, and migration (60, 61). FGF-2 stimulates pericyte proliferation and production of proteinases from endothelial cells, which can locally degrade the extracellular matrix, allowing cells to migrate for the formation of the new vessels (61–63). It induces formation of tubular structures in endothelial cell cultures in vitro and promotes angiogenic responses and vascular regeneration in vivo (60, 63, 64). Brain endothelial cells form the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and tightly regulate the transport between the brain and the periphery (65) and it has been suggested that aberrant angiogenesis and senescence of the cerebrovascular system initiates neurovascular uncoupling, vessel regression, brain hypoperfusion and neurovascular inflammation in AD (65). This previous evidence and our findings, suggest that a decline in sTREM2-related FGF-2 levels may be indicative of BBB changes in late stage AD. To our knowledge a link between peripheral sTREM2 and FGF-2 is a novel finding that is supported only by our previous report that indicates that, in a human microglial cell line treated with Aβ42, TREM2 overexpression inhibits FGF-2 (66).

GM-CSF levels were decreased in AD and in the A+T+N− individuals. It was also positively correlated with sTREM2 in CN individuals, but not in MCI or AD, while it was correlated in A+T+N+ individuals. When sTREM2 is elevated GM-CSF is also elevated in a pattern of early increase and late decrease in levels (Figure 9). Interestingly, in the network analysis GM-CSF is normally part of a community of other inflammatory factors associated with sTREM2 levels that include IFNy, IL-17A, VEGF, IL-7, Fractalkine and IFNa-2, while in the early stages of AD this association with sTREM2 is lost even though some of the relationships with other factors remains. GM-CSF is a cytokine that regulates the numbers and function of cells of macrophage-monocyte lineage (67). It is a product of cells activated during inflammatory or pathologic conditions and is secreted by macrophages, T cells, mast cells, natural killer cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts (67). In mouse models of AD, GM-CSF inhibition reduces brain amyloidosis, increases plasma Aβ, and rescues cognitive impairment (68, 69). One study suggests that GM-CSF improves cognition in cancer patients (70). Together, this suggests that in AD there may be a sTREM2-related decrease in GM-CSF that is indicative of an alteration in the normal function of peripheral cells of macrophage-monocyte lineage. To our knowledge a relationship between sTREM2 and GM-CSF is novel information. This implicates an alteration in the systemic inflammatory response in AD involving sTREM2-related GM-CSF that warrants further investigation.

IL-1β was lower in AD, compared to MCI and in A+T+N+, compared to A+T+N−. In addition, IL-1β correlated with sTREM2 in AD and in both A+T+N− and A+T+N+ groups (Figure 9). In the network analysis, IL-1β was normally part of the same community of inflammatory factors as FGF-2 and TREM2. This community relationship remained in MCI and A+T−N−, while not including sTREM2 in the A+T−N− group, and was lost in AD and A+T+N− or A+T+N+ groups. In contrast to our findings of lower levels of IL-1β in AD than in MCI, previous reports have shown either an increase or no difference in peripheral levels from patients with AD (8, 14, 71) suggesting that heterogeneity in pathological stage across cohorts could contribute to the discrepancy across studies. In support of this idea, there was a slight, although non-significant increase in MCI and in the early ATN groups in our cohort with the decrease only in late stage AD evident in the A+T+N+ group implicating a very late stage decrease in IL-1β in AD. IL-1β overexpression is associated with reduced amyloid plaques and levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in a mouse model of AD (72). Interestingly, IL-1β down-regulates expression of TREM2 mRNA in cultures of human peripheral blood monocytes and synovial fluid macrophages from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (73). Together, this suggests that the positive correlation between IL-1β and sTREM2 as well as decreased levels of IL-1β in later stages of AD observed in our study is not likely related to IL-1β induced downregulation of peripheral TREM2. However, further study is necessary to fully understand the nature of the relationship between TREM2 and IL-1β in AD.

Fractalkine was significantly higher in MCI than AD, and significantly higher in A+T−N− compared to both A−T−N− and A+T+N− suggesting that this cytokine may increase early in the A+ stage and later decrease as the disease progresses (Figure 9). Fractalkine was significantly correlated with sTREM2 only in the CN (Figure 9C) suggesting that normally when sTREM2 is elevated, fractalkine is also elevated. Interestingly, in the network analysis, Fractalkine is normally (in CN and A−T−N−), part of the same community as GM-CSF, but not in AD or A+T−N− or A+T+N−, while this relationship is regained in the A+T+N+ stage. This may suggest that this community of inflammatory factors are critically disrupted in early AD progression. This idea is supported by previous evidence that describes fractalkine as an immunoregulatory cytokine that reduces inflammatory signaling in activated microglia and reduce tau pathology when over-expressed (74–79). Additionally, both fractalkine and TREM2 are cleaved by the same enzyme, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM-10), which may link the downstream function of the two proteins (18, 19, 80) suggesting important links between Fractalkine and sTREM2.

A limitation of this exploratory study is small sample size, especially for the ATN groups. Although we did gather evidence for multiple cytokines, our findings will need to be tested in a larger cohort to validate the correlations observed. Even though, a preliminary power analysis suggested a sample size of 25 per group would achieve the desired power, the data should be approached with caution since there is a potential for false negative results for some of the analytes with detectable levels in the very low range. Another limitation is that some important inflammatory factors may have been missed since the thirty-eight inflammatory factors available on the inflammatory panel utilized is not comprehensive of the multiple immune factors present in the circulation. Outliers were removed using a standard method of ROUT with Q=1%, indicating a false discovery rate of outliers was, at most, 1%. This method has been published previously by other groups (35, 36). However, it does have the risk of eliminating true data points that are outside of the expected range that may contain biological significance. Follow-up studies of characteristics of participants with very high and low levels of cytokines could add further knowledge to the underlying biological mechanisms. Additionally, another limitation is that we utilized Aβ42/Aβ40 for “A”, p-Tau for “T” and t-Tau for “N” as in other reports (81). Others have argued that only “A” and “T” groups should be used or that imaging or neurofilament light should be used for “N” (82, 83). As with any test that uses a cutoff value for positivity, there is likely a grey area of overlap between the groups that could not be completely separated. Furthermore, given the identified alterations in basophil levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in AD the results should be approached with caution since, immune factor levels could have been altered due to factors such as undiagnosed inflammatory illnesses or impending infections. Future studies will benefit from increased sample size, more diverse inflammatory panels and single cell-based analyses to further understand the underlying source of these results. Importantly, longitudinal studies will help tease apart these inflammatory effects on disease progression.

In this exploratory study, we identified patterns of sTREM2-related inflammatory activity that differed by clinical diagnosis and ATN category. Plasma sTREM2 was linked to inflammatory activity in the peripheral circulation, where strong connections and patterns were observed in the groups without AD symptoms or CSF ATN biomarkers (CN and A−T−N−). In addition, they were profoundly altered in the MCI and A+T−N− stages suggesting that the pathological amyloid stage, prior to the pathological tau stage, may be the critical stage for peripheral immune system intervention in AD. Notable inflammatory factors that had both a significant relationship with sTREM2 and significantly different levels across groups were GM-CSF, FGF-2, IL-1β and Fractalkine. This study lays the groundwork for research and therapeutic strategies that seek to understand or target TREM2-related inflammatory activity in AD. Together, the findings suggest that depending on AD stage, therapeutically targeting TREM2 may broadly influence inflammatory activity.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Early stage alterations in peripheral sTREM2-related inflammatory activity.

These alterations implicate early cell development and recruitment signaling in AD.

Patterns of inflammatory activity are altered across all AD stages.

Funding:

National Institute of Aging (R01AG066707 and 3R01AG066707-01S1 (analysis and interpretation of data) AG063870 (collection, analysis and interpretation of data), P30 AG062428 (collection), R01 AG022304 (collection), Cleveland Clinic Center of Excellence Award (interpretation of data), Jane and Lee Seidman Fund (collection, analysis and interpretation of data), Aging Mind Foundation (analysis and interpretation of data).

• Ethics approval and consent to participate: Participants consented under the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease Biobank (LRCBH-Biobank) and the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (CADRC) protocols approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

List of abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- TREM2

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

- sTREM2

soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

- ATN

amyloid beta, phosphorylated tau, and neurodegeneration

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CN

cognitively normal

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- p-Tau

phosphorylated tau

- t-Tau

total tau

- LRCBH-Biobank

Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease Biobank

- CADRC

Cleveland Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

- CBC

Complete blood counts

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- EGF

Epidermal Growth Factor

- FGF-2

Fibroblast Growth Factor 2

- TGF-α

Transforming Growth Factor alpha

- G-CSF

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- Flt-3L

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor

- IFN

interferon

- GRO

growth-regulated oncogene

- IL

interleukin

- MCP

Monocyte chemotactic protein

- MDC

Macrophage-derived chemokine

- sCD40L

soluble CD40-ligand

- IL-1RA

interleukin 1 receptor agonist

- IP-10

interferon-gamma inducible protein

- MIP

macrophage inflammatory protein

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

Footnotes

Declarations:

• Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- 1.2020. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ. 2013. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet neurology. 12: 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jack CR Jr., Holtzman DM. 2013. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 80: 1347–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidd PM 2008. Alzheimer’s disease, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and age-associated memory impairment: current understanding and progress toward integrative prevention. Altern Med Rev. 13: 85–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis M, O.C. T, Johnson S, Cline S, Merikle E, Martenyi F, Simpson K. 2018. Estimating Alzheimer’s Disease Progression Rates from Normal Cognition Through Mild Cognitive Impairment and Stages of Dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 15: 777–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Feldman HH, Frisoni GB, Hampel H, Jagust WJ, Johnson KA, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Scheltens P, Sperling RA, Dubois B. 2016. A/T/N: An unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 87: 539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JC, Han SH, Mook-Jung I. 2020. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: a brief review. BMB Rep. 53: 10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Hu Y, Cao Z, Liu Q, Cheng Y. 2018. Cerebrospinal Fluid Inflammatory Cytokine Aberrations in Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 9: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calsolaro V, Edison P. 2016. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 12: 719–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Page A, Dupuis G, Frost EH, Larbi A, Pawelec G, Witkowski JM, Fulop T. 2018. Role of the peripheral innate immune system in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 107: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wotton CJ, Goldacre MJ. 2017. Associations between specific autoimmune diseases and subsequent dementia: retrospective record-linkage cohort study, UK. J Epidemiol Community Health. 71: 576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]