Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide, and the third leading cause of cancer-related death globally. HCC comprises nearly 90% of all cases of primary liver cancer. Approximately half of all HCC patients receive systemic therapy during their disease course, particularly in the advanced stages of disease. Immuno-oncology has been paradigm shifting for the treatment of human cancers, with strong and durable anti-tumor activity in a subset of patients across a variety of malignancies including HCC. Immune checkpoint inhibition with atezolizumab and bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor neutralizing antibody, has become first line therapy for patients with advanced HCC. Beyond immune checkpoint inhibition, immunotherapeutic strategies such as oncolytic viroimmunotherapy and adoptive T cell transfer are currently under investigation. The tumor immune microenvironment of HCC has significant immunosuppressive elements that may impact response to immunotherapy. Major unmet challenges include defining the role of immunotherapy in earlier stages of HCC, evaluating combinatorial strategies that employ targeting of the immune microenvironment plus immune checkpoint inhibition, and identifying treatment strategies for patients who do not respond to the currently available immunotherapies. Herein, we review the rationale, mechanistic basis and supporting preclinical evidence, and available clinical evidence for immunotherapies in HCC as well as ongoing clinical trials of immunotherapy.

Keywords: tumor immune microenvironment, immune-related adverse events, liver cirrhosis, locoregional treatment, systemic treatment

I. Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most common cancers in the world and has a rising incidence worldwide, particularly in the West [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer, accounting for over 90% of cases. HCC typically arises in a background of chronic liver disease including chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Although hepatitis B is the most notable risk factor as it accounts for a significant proportion of HCC cases, NASH is becoming the fastest growing risk factor for HCC, particularly in the Western world [2]. Management options for HCC vary based on the tumor burden, liver function, comorbidities, and performance status of a patient. For early-stage disease, surgical resection and liver transplantation are the primary potentially curative treatment options with excellent long-term outcomes [3]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is the primary local modality employed for early-stage HCC [4], and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) remains the standard of care for patients with intermediate-stage HCC [5]. The use of systemic anticancer therapy for advanced stage HCC was controversial prior to 2008 due to lack of efficacy and poor patient tolerance. In 2007, the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib received FDA approval for patients with advanced HCC with preserved liver function. This was based on the SHARP trial, a phase 3, randomized controlled trial that demonstrated an overall survival (OS) benefit in the sorafenib group compared to placebo [6]. Over the last 4 years, three other TKIs were approved for advanced HCC; lenvatinib was found to be non-inferior to sorafenib in the first line setting [7], while regorafenib (in patients who are tolerant to sorafenib) and cabozantinib had a survival benefit in the second line setting [8, 9]. In addition, ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGFR2, was approved in patients with baseline alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) concentrations ≥400 ng/dL after progression on sorafenib [10].

Over the past decade, immuno-oncology has been a paradigm shift in the treatment of malignancies including liver cancer. The anti-tumor immune response harnesses elements of the innate and adaptive immune system [11]. However, tumors can co-opt this response and enact immune evasion by different mechanisms such as fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment or mediating cytotoxic cell dysfunction. An immunosuppressive tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is characterized by an abundance of regulatory T cells (Treg), immunosuppressive myeloid cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and inhibitory B cells [12]. Activation of immune checkpoints including coinhibitory molecules restrains activation of effector lymphocytes and is integral to tumor immune evasion [13]. These negative regulators of T cell activation include programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) amongst others. Immunotherapeutic approaches to treat cancer include immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) with monoclonal antibodies that block the checkpoint receptor-ligand interactions thereby fostering a robust cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response [14]. Adoptive cell-based therapies employ infusion of cytotoxic immune cells into patients. Transgenic tumor antigen-specific T cell receptors or chimeric antigen receptors are the two primary approaches of adoptive cell therapy. ICI therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy in a subset of patients across a variety of malignancies including HCC. The combination of the anti-PDL1 antibody atezolizumab and the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) neutralizing antibody bevacizumab has become first-line therapy for HCC [15]. Herein, we review the rationale, mechanistic basis and supporting preclinical evidence, and available clinical evidence for immunotherapies in HCC as well as ongoing clinical trials of immunotherapy.

II. Tumor Immune Microenvironment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The liver plays an essential role in immune surveillance and thus has a distinctive microenvironment [16]. The liver is continually exposed to blood-borne pathogens, particularly gut-derived pathogens, as it has both an arterial and portal venous blood supply. Accordingly, the baseline liver microenvironment has a plethora of innate and adaptive immune cells to facilitate pathogen clearance, while maintaining tolerance to non-pathogenic exogenous molecules in portal blood. This balance is critical and accounts for the liver having a unique immune tolerogenic niche, which in turn can facilitate HCC development [17]. The immune microenvironment of HCC likely has an impact on efficacy of ICI. Accordingly, a comprehensive understanding of the HCC TIME is essential in the effort to develop effect immunotherapies. Notably, the current insights into the HCC TIME have been based primarily on early-stage tumors. It is plausible that the TIME varies by disease stage with advanced-stage HCC having a distinct TIME compared to early-stage HCC.

a. Cytotoxic elements of the HCC TIME and therapeutic implications

The cytotoxic immune response is attenuated in HCC. CD8+ T lymphocytes are the primary cytotoxic tumor infiltrating lymphocyte subset in HCC. Enrichment of CD8+ T lymphocytes is associated with a better prognosis [18, 19]. However, these CTLs have impaired interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production, suggesting that they are dysfunctional [19]. There are a variety of factors and cell types that contribute to a dysfunctional state of CD8+ T lymphocytes. For instance, accumulation of liver-resident immunoglobulin-A-producing (IgA+) cells in murine and human NASH is associated with a robust inhibition of the tumor-directed CTL response in HCC. Immune checkpoints are negative regulators of CTL function across a variety of malignancies including HCC. Immune checkpoints in the HCC TIME include PD-1, CTLA-4, lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), V-domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing-3 (TIM3).

Similarly, natural killer (NK) cell dysfunction also occurs in HCC and correlates with patient survival. For instance, patients with better outcomes have NK cells with higher expression of cytotoxic granules or the activating KIR2DS5, and lower levels of the inhibitor NK receptor NKG2A [20, 21]. Moreover, accumulation of CD11b−CD27− NK cells, an immature and inactive phenotype with poor cytolytic activity, is associated with HCC progression [22]. NK cell function can also be dampened by immunosuppressive cells such as MDSCs and Tregs as well as immunosuppressive cytokines including interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) [23, 24].

b. Immunosuppressive elements of the HCC TIME and their therapeutic potential

An accumulation of immunosuppressive elements dampens the cytotoxic immune response in the HCC TIME and is associated with poor patient outcomes. Pro-tumor, immunosuppressive cell types in HCC include lymphocytes and myeloid cells.

i. Immunosuppressive lymphocytes

Tregs have an essential role in maintenance of self-tolerance and regulation of immune responses under physiologic conditions as well as in disease states including cancer. Circulating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs are increased in HCC patients and correlate with tumor progression and decreased patient survival [25]. Moreover, accumulation of Tregs in the tumor core is associated with reduced infiltration and effector function of CD8+ T cells [25]. Intratumoral balance of Tregs and CD8+ T cells is also prognostic with a balance favoring CD8+ T cells being associated with improved OS [26]. However, it remains to be determined whether the balance of CD8+ T cells and Tregs correlates with response to ICI. In a comprehensive biomarker analysis of tumor specimens from patients enrolled in CheckMate 040, increased frequency of CD3+ T cells was associated with response to ICI with nivolumab. Moreover, the presence of tumor-infiltrating CD3+ and CD8+ T cells was associated with a trend towards improved OS. The presence of inflammatory signatures including an interferon gamma signature correlated with either objective response rate (ORR) or OS. However, FoxP3+ Treg abundance did not correlate with response to nivolumab [27]. Tumor-infiltrating Tregs are recruited to the HCC TIME by chemokines such as chemokine ligand 20 and other immunosuppressive cells such as MDSCs [28, 29]. TGF-β can promote abundance and differentiation of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs. Similarly, VEGF augments infiltration of MDSCs and Tregs in tumors with concomitant attenuation of effector T cell activation [30]. Accordingly, blockade of either VEGF or TGF-β restrains tumor growth via modulation of the TIME including reduction in Treg and MDSC abundance and increased effector T cell activation. Blockade of the TGF-β receptor using a specific inhibitor, SM-16, reduced Treg infiltration and HCC progression in a N-nitrosodiethylamine induced murine model [31].

Although B cells are an abundant element in tumors, their role in liver cancer is not well-defined [32]. Regulatory B cells (Bregs) have a pro-tumorigenic role via production of immunosuppressive cytokines and regulation of the cytotoxic T cell response [33–36]. There is some evidence that such an immunosuppressive population is also present in HCC. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3-positive (CXCR3+) B cells comprise a significant proportion of the B cell population in HCC, and their accumulation is correlated with early recurrence of HCC. CXCR3+ B cells facilitate transition of macrophages to an alternatively activated, ‘M2-like’ phenotype in HCC and their depletion using anti-CD20 attenuates M2-like polarization and HCC growth in preclinical models [34]. PD-1+ Bregs have a phenotype distinct from peripheral Bregs and constitute approximately 10% of all B cells in advanced stage HCC [36]. Upon encountering PD-L1+ cells, PD-1+ Bregs acquire regulatory functions via IL-10 signaling with consequent T cell dysfunction and disease progression.

ii. Immunosuppressive myeloid cells

Immunosuppressive myeloid cells play an essential role in HCC as they contribute to a pro-tumor microenvironment and are associated with a poor prognosis. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) with high levels of CD163 and scavenger receptor are characterized as M2-like, and abundance of M2-like macrophages in HCC patients is associated with increased tumor nodules and venous infiltration [37]. An immunogenomic analysis of 10,000 tumors across 33 cancers assessed lymphocyte and myeloid signatures using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data and identified six immune subtypes. HCCs were categorized under the lymphocyte-depleted subtype characterized by a prominent macrophage signature and a high M2 response [38]. However, single cell transcriptomics has highlighted that TAM phenotypes are more complex and dynamic than the conventional M1/M2 model [39].

MDSCs are pathologically activated potent immunosuppressive cells, and their accumulation in cancer is associated with poor patient outcomes. The two primary subsets of MDSCs classified according to their origin as granulocytic or polymorphonuclear and monocytic MDSCs [40]. Several subsets of MDSCs have been described in liver cancer. CD14+HLA-DR/low cells are present in the peripheral blood of HCC patients and have potent immunosuppressive properties including suppression of autologous T lymphocyte proliferation and induction of Tregs [29]. MDSCs foster tumor growth and progression, in part, via production of VEGF, a soluble factor which augments tumor vascularization and neoangiogenesis [40]. MDSCs from HCC patients also inhibit autologous NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion in an NKp30 dependent manner [23]. Depletion of MDSCs from HCC patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells restored CTL effector function as evidenced by production of granzyme B and also increased the number of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells [41]. MDSCs also play an important role in immune evasion in HCC. Adoptive cell transfer of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) into tumor-bearing mice had impaired antitumor activity due to an increase in MDSCs in two different HCC models [42]. The robust pro-tumor, immunosuppressive function of MDSCs has garnered interest as a potential immunotherapeutic approach. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibition is one approach that has been utilized to target MDSCs [43]. PDE5 inhibition in preclinical models of HCC attenuated MDSC function via blockade of arginase 1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase [42]. This reversal of MDSC-mediated immunosuppression enhanced CIK activity.

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) can support tumor progression and promote an immunosuppressive TIME by fostering tumor angiogenesis, migration, and invasion [44]. CXCL5 promotes TAN infiltration in HCC, and CXCL5 overexpression and TAN abundance is associated with poor patient prognosis in HCC [45]. CCL2+ or CCL17+ TANs correlate with tumor size, microvascular invasion, tumor differentiation and stage in HCC [46]. Moreover, TANs modulate the HCC TIME via recruitment of macrophages and Tregs. Accordingly, the combination of TAN depletion and sorafenib attenuated neovascularization and tumor growth in preclinical models of HCC.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells with an essential role in activation of the anti-tumor adaptive immune response. DCs acquire tumor antigens and activate CTLs. However, tolerogenic DCs are a regulatory DC subtype that can suppress the anti-tumor immune response [47]. CD14+CTLA-4+ regulatory DCs suppress the CTL response in HCC via IL-10 and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase [48]. LAMP3+ DCs are a mature form of conventional DCs, and are another DC subset that may be associated with dysfunctional CTLs as they can potentially regulate a variety of lymphocytes in human HCC [39]. The immunostimulatory role of DCs can be leveraged in immunotherapeutics. AFP has been identified as a tumor rejection antigen in murine HCC. In a phase I/II clinical trial, patients (n=10) with AFP-positive HCC were immunized with intradermal vaccinations of AFP peptides pulsed onto autologous DC [49]. Six of the 10 subjects had a significant increase in AFP-specific T cells postvaccine. In a subsequent study, the same investigators demonstrated that vaccination of HCC patients with peptide-loaded DCs enhanced NK cell activation and reduced Treg frequency in the HCC TIME [50].

c. Single immune cell landscape, crosstalk, and mechanisms of immune evasion in HCC

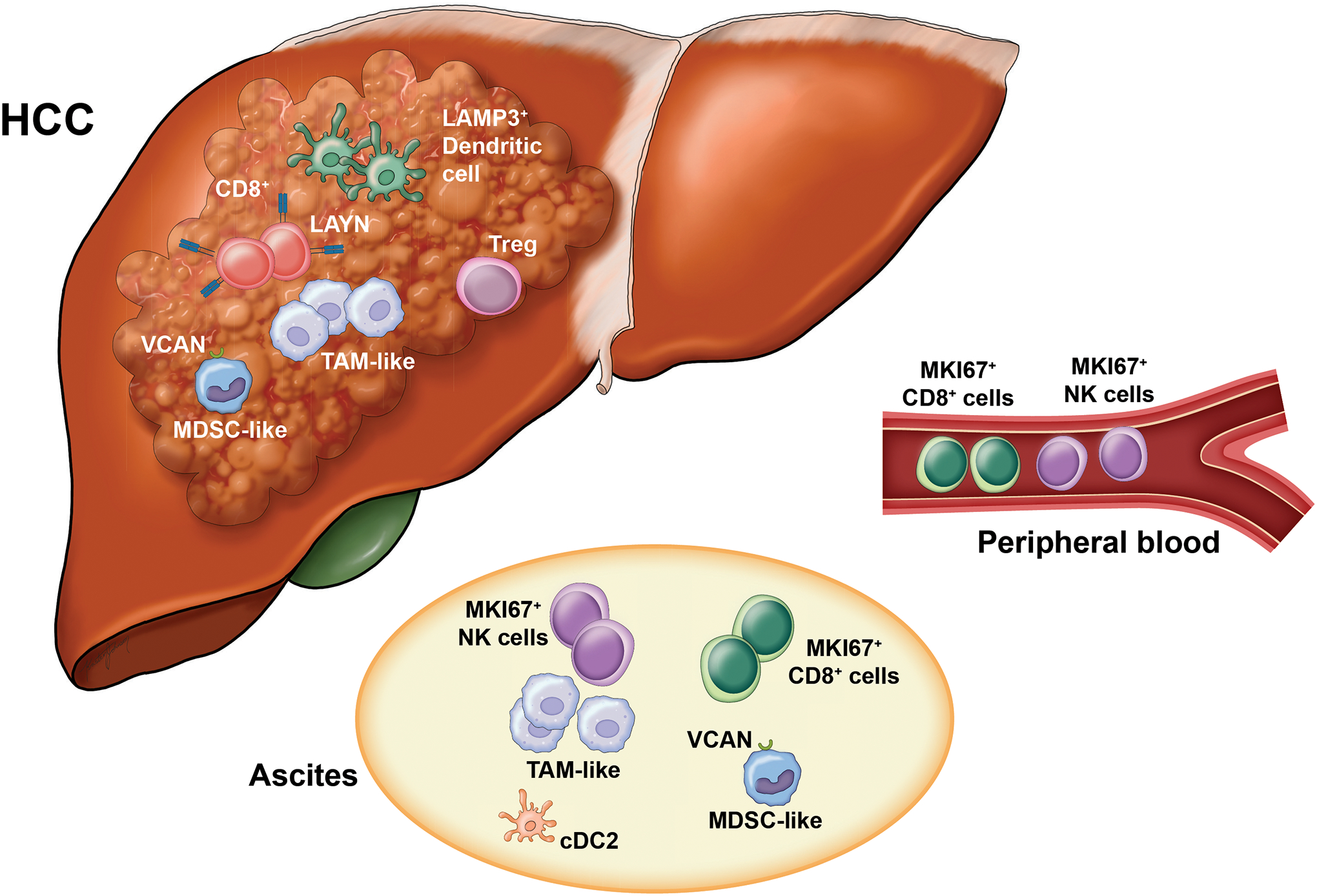

Single cell omics has provided essential insight into the dynamics and diversity encountered within complex tumor ecosystems. Such high-resolution analyses have identified distinct immune subsets and their functional states as well as predictions of complex cellular crosstalk [39, 51–53]. In-depth single-cell transcriptomic analysis of 5,063 single T cells isolated from 6 HCC patients revealed enrichment and potential clonal expansion of Tregs and exhausted CD8+ T cells with high expression of a regulatory gene, layilin (LAYN) [51]. LAYN overexpressed CD8+ T cells were dysfunctional with repressed cytotoxic function including attenuation of IFN-γ production, whereas LAYN-overexpressed Tregs were potentially more repressive and stable. Transcriptome profiling of 75,000 CD45+ single immune cells from 16 HCC patients demonstrated dynamic properties of diverse CD45+ immune cell types. For instance, two distinct states of macrophages in HCC tumors, TAM-like macrophages and MDSC-like macrophages, were described (36). TAM-like macrophages had high expression of C1QA+ and expressed GPBMB and SLC40A1, both genes were linked to poor patient prognosis based on TCGA analysis. In comparison, MDSC-like macrophages had high expression of S100A family genes FCN1 and VCAN. A unique subset of conventional dendritic cells, LAMP3+, was also detected. LAMP3+ DCs had a lymphocyte regulatory function, correlated with dysfunctional T cells, and had the potential to migrate to lymph nodes. This study also demonstrated that lymphocytes and macrophage subsets identified in ascites of HCC patients could originate from the primary tumor. The immune ecosystem of early-relapse HCC is unique and may, in part, explain the high relapse rate and poor overall prognosis associated with HCC. Profiling of the transcriptomes of 17,000 cells from 18 primary or early-relapse HCC patients revealed clonal expansion of innate-like CD8+ T cells that exhibited low cytotoxicity [52]. In aggregate, these findings provide insight into the dynamic nature of various immune cell subsets, and their contribution to largely immunosuppressive TIME in HCC (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dynamics of the tumor immune microenvironment of HCC.

High resolution analysis using single cell omics has provided insight into the dynamic nature of various immune subsets and their contribution to a largely immunosuppressive immune microenvironment in HCC. Immunosuppressive cell populations in the HCC TIME including Tregs, MDSCs and TAMS contribute to dysfunction of CD8+ T cells and DCs. LAMP3+ DCs may be a common DC subset that has maturation features and may play a role in T cell dysfunction. In HCC patients with ascites, immune cell subsets may migrate from the primary tumor (TAM-like, MDSC-like) or from the peripheral blood (MKI67+ CD8+ cells or NK cells). DC, dendritic cell; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TIME, tumor immune microenvironment.

d. HCC mutational landscape, hepatic environment, and the TIME

Oncogenic pathways driven by genetic alterations may have an impact on the immune microenvironment and immune surveillance. This in turn can impact response to immunotherapies. The Wnt–β-catenin signalling pathway is activated in 30–50% of HCCs [54]. β-catenin activated HCCs are characterized by lower immune signatures and downregulation of chemokine (c-c motif) ligands 4 which is associated with failure of T cell priming [55]. Accordingly, these tumors are also characterized by T cell exclusion. In a unique genetic mouse model of HCC, β-catenin activation resulted in immune evasion via defective recruitment of dendritic cells and impaired T cell activity with consequent resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy [56].

HCC induction and anti-tumor immune response can be regulated by the hepatic environment, which in turn may vary according to HCC etiology. Emerging preclinical data suggest that tumor immune surveillance is impaired in HCC arising in the context of NASH [57]. In mouse models of NASH-related HCC, but not HCC due to other etiologies, immunotherapy with anti-PD-1 led to an enrichment of CD8+PD1+T cells without tumor regression. Prophylactic anti-PD-1 therapy in murine models of NASH unexpectedly led to an increase in CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T cells and increased incidence of HCC in NASH mice. CXCR6+CD8+PD1+ T cells had high expression of cxcr6, Gzmb, Ifng, Tnf, and Pdcd1 suggesting features of tissue residency, effector function, and exhaustion, respectively. A similar CD8+PD1+T cell profile was observed in human NASH. These data suggest that the liver immune microenvironment may be unique in NASH. However, it remains to be seen whether immune surveillance and immunotherapy response may differ according to the underlying etiology of HCC.

e. Modulation of the HCC TIME by microbiome and stromal factors

The gut microbiota has an integral role in regulation of bile acid production, and disruption of this crosstalk can facilitate inflammation and carcinogenesis including HCC [58]. Patients with chronic liver disease have accumulation of gut-derived endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Attenuation of LPS levels using antibiotics or genetic ablation of its receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) inhibits tumor growth in preclinical models of HCC [59]. Moreover, in murine models of chronic liver injury, intestinal microbiota and TLR4 activation facilitate hepatocarcinogenesis [60]. The commensal microbiome may impact antitumor immunity in cancer, and is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in melanoma [61]. Alteration of commensal gut bacteria in mice had an anti-tumor effect in preclinical models of liver cancer via an increase in hepatic CXCR6+ natural killer T (NKT) cells [62]. Conversion of primary-to-secondary bile acids via the gut microbiome led to NKT cell accumulation. In aggregate, these studies suggest there is a link between regulation of commensal gut microbiome and liver antitumor immunity.

The TGF-β is implicated in cancer progression and metastasis. High TGF-β levels in HCC patients are associated with lower OS, and poor response to sorafenib [63]. Activated TGF-β signaling can promote an immunosuppressive TIME via several mechanisms including induction of tolerogenic DCs and facilitating a switch to pro-tumor, M2-like macrophages [47, 64]. Accordingly, high baseline plasma TGF-β levels are associated with resistance to the anti-PD-L1 antibody, pembrolizumab [65].

VEGF, another soluble factor that plays an integral role in the tumor microenvironment, is produced by tumor cells as well as stromal cells. VEGFA amplification in a subset of human HCCs mediates paracrine interactions within the HCC TME with increased production of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and consequent tumor growth and progression. Accordingly, VEGFA inhibition downregulated HGF production and attenuated tumor growth in a preclinical model of HCC. Moreover, murine and human HCCs harboring VEGFA amplification had enhanced sensitivity to the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib [66]. The function of VEGF extends beyond promoting tumor angiogenesis. Single cell RNA sequencing of primary liver cancers has demonstrated that these tumors have high diversity which has a negative correlation with patient prognosis [53]. Malignant cells with high diversity produce VEGFA which reprograms the tumor microenvironment of liver cancer including promotion of T cell dysfunction. Furthermore, VEGF has extensive immunomodulatory effects including expansion of immunosuppressive elements such as Tregs and MDSCs in the TIME, attenuation of effect T cell activation, and inhibition of DC function [30]. The VEGF inhibitor bevacizumab restores antitumor immunity partly via reduction of circulating S100A9 positive MDSCs [67]. This essential role of VEGF in the HCC TIME provides rationale for the success of combination anti-VEGF and ICI in the first-line setting for HCC.

III. Immunotherapy for Advanced Stage HCC

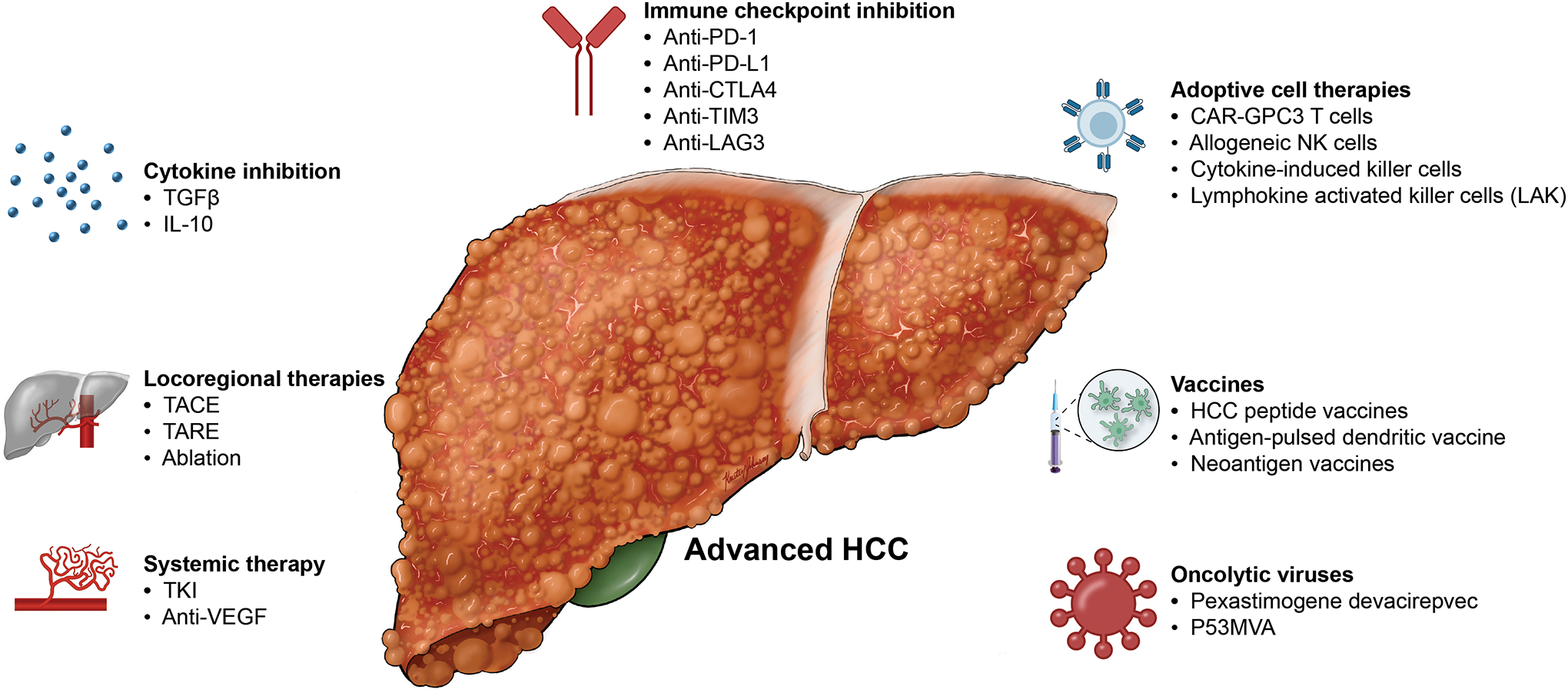

The benefit of immunotherapy for advanced HCC has been clearly established. The predominant drug class are the ICIs, in particular those that block PD-1 or PD-L1. They have been tested both alone and in combination in large clinical trials and have become an integral part of systemic treatment of HCC. Moreover, emerging immunotherapeutics such as adoptive cell therapy have the potential to enhance the efficacy of ICI in HCC (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Potential combination strategies employing ICI in HCC.

Multiple therapies under investigation have the potential to enhance the anti-tumor response in HCC when combined with ICI. These include combination of ICI with other immunotherapeutics such as adoptive cell therapies, vaccines, and oncolytic viruses. ICI can also be combined with systemic therapies and locoregional therapies. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition.

Monotherapies with ICIs

Nivolumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against PD-1, was first tested in HCC in the phase I/II CheckMate 040 study which included 262 patients with HCC with or without previous exposure to sorafenib. Nivolumab produced an ORR of 14% by RECIST 1.1 (18% by mRECIST) with a median response duration of 17 months (95% confidence interval (CI) 6–24) [68]. The study reported a median OS of 15.6 months and a safety profile similar to previous trials with nivolumab. As a consequence, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to nivolumab for patients with advanced stage HCC previously treated with sorafenib (Table 1). The following phase 3 CheckMate 459 study tested nivolumab as first-line treatment against sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC who had not received systemic treatment before [69]. They were randomized to receive either nivolumab at 240 mg IV once every two weeks (n = 371) or sorafenib with the standard dose of 400 mg bid (n = 372). Surprisingly, the study did not meet its primary endpoint of improving OS, although patients treated with nivolumab had a numerically superior OS compared to sorafenib (median OS for nivolumab 16.4 months vs 14.7 months for sorafenib; HR = 0.85 [95% CI: 0.72–1.02]; p = 0.0752). Correspondingly, the median OS rates at 12 months and 24 months were higher for nivolumab than for sorafenib (60% vs. 55% and 37% vs. 33%). The observed benefit was independent of the PD-L1 status and present across most predefined subgroups. While the ORR was higher in the nivolumab (15%) than in the sorafenib arm (7%), the median progression-free survival (PFS) was similar between both arms (3.7 months for nivolumab and 3.8 months for sorafenib). In terms of safety, nivolumab showed a less toxic profile than sorafenib with fewer grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events (trAEs) and fewer trAEs leading to discontinuation. Following an assessment of accelerated approvals for ICIs by the FDA which recommended against upholding the approval of nivolumab, the manufacturer of nivolumab (Bristol Myers Squibb) decided to withdraw its indication as post-sorafenib monotherapy in HCC from the US market [70].

Table 1.

Past clinical trials on systemic immunotherapy in HCC that resulted in regulatory approval.

| Trial Name | Treatment arms | Line of Therapy | Primary Endpoint | ORR | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHECKMATE 040 | Nivolumab* single arm | Second | ORR | 15% | N/A | N/A |

| CHECKMATE 040 | Nivolumab + ipilimumab** single arm | Second | ORR | 32% | N/A | N/A |

| IMbrave150 | Atezolizumab+bevacizumab vs. sorafenib | First | OS and PFS | 29.8 vs. 11.3% | 6.8 vs. 4.3 months | 19.2 vs. 13.4 months (HR 0.66) |

| KEYNOTE 224 | Pembrolizumab** single arm | Second | ORR | 17% | N/A | N/A |

Initial regulatory approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has been withdrawn by the manufacturer. No approval by the European Medicines Agency.

Regulatory approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but not the European Medicines Agency.

HR, hazard ratio; N/A, not available; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Pembrolizumab, another anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody, suffered a similar fate: After a successful Keynote-224 phase 2 trial [71], it was approved by the FDA for advanced stage HCC previously treated with sorafenib (Table 1). However, the subsequent Keynote-240 phase 3 trial failed to meet its primary endpoints [72]. Keynote-224 tested pembrolizumab in 104 patients with advanced HCC who had progressed on sorafenib. It reported an ORR of 17% (RECIST v1.1), a PFS of 4.9 months and a median OS of 12.9 months. There were no new safety signals. Unlike CheckMate 459, Keynote-240 evaluated pembrolizumab in the second-line setting randomizing 413 patients 2:1 to receive either pembrolizumab at 200 mg IV once every three weeks (n = 278) or placebo (n = 135). The study was designed to measure both OS and PFS as primary endpoints and reported a median OS of 13.9 months (95% CI: 11.6 to 16.0 months) for pembrolizumab versus 10.6 months (95% CI: 8.3 to 13.5 months) for placebo (HR = 0.781 [95% CI: 0.611 to 0.998]; p = 0.0238) and a median PFS of 3.0 months for pembrolizumab (95% CI: 2.8 to 4.1 months) versus 2.8 months for placebo (95% CI: 1.6 to 3.0 months) at final analysis (HR = 0.718 [95% CI, 0.570 to 0.904]; p = 0.0022). These co-primary endpoints just missed the pre-defined threshold for statistical significance (p=0.0174 for OS and p=0.002 for PFS) resulting in a formally negative study and no approval for pembrolizumab monotherapy outside the USA. Regarding safety, the known side-effects were recorded with grade 3 or higher adverse events being slightly more frequent in the pembrolizumab than in the placebo group (147 [52.7%] vs. 62 [46.3%]; treatment related 52 ([18.6%] vs. 10 patients [7.5%]). KEYNOTE-394 was a phase 3 trial evaluating pembrolizumab against placebo in Asia in 453 patients with advanced HCC previously treated with sorafenib (randomized 2:1). Recently, the study reported a significantly improved OS (HR = 0.79 [95% CI 0.63–0.99]; p = 0.0180), PFS (HR = 0.74 [95% CI 0.60–0.92]; p = 0.0032) and ORR (estimated difference 11.4% [95% CI 6.7–16.0]; p = 0.00004) for pembrolizumab versus placebo. The median OS was 14.6 versus 13.0 months, PFS 2.6 versus 2.3 months and ORR 13.7% versus 1.3% [73].

Although the phase 3 studies CheckMate 459 and KEYNOTE-240 did not yield the required proof that single agent use of either nivolumab or pembrolizumab provides a benefit in advanced HCC, they showed that these agents appear to have some antitumor activity in a subgroup of patients reflected in an ORR of 14–17% and response durations of >1 year. Therefore, they remain a later line treatment option in patients with advanced HCC who have progressed on the available tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and have not received a PD1/PD-L1 inhibitor previously.

Further proof that single agent PD1/PD-L1 inhibition has antitumor activity has been provided by the HIMALAYA phase 3 trial, which has tested a single, high priming dose of tremelimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody, added to durvalumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody (STRIDE), or durvalumab alone in comparison to sorafenib as first-line treatment in 1,171 patients with advanced HCC (NCT03298451). Monotherapy with durvalumab met the objective of OS non-inferiority to sorafenib (HR = 0.86 [96% CI 0.73–1.03]) while being less toxic (12.9% grade 3/4 trAEs with durvalumab versus 36.9% with sorafenib) [74].

Regarding anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy, the study 22 (phase 1/2) found a median OS of 15.1 months (95% CI 7.7 – 24.6) and a median PFS of 2.0 months (95% CI 1.8 – 5.4) with a manageable safety profile for tremelimumab monotherapy in patients previously treated with sorafenib after intolerable toxicity or rejection of sorafenib. However, the combination of tremelimumab with durvalumab showed an overall better benefit-risk ratio [75]. Moreover, early expansion of Ki67+CD8+ T cells was associated with response to either treatment alone or the combination.

Tislelizumab is another anti-PD1-antibody which is currently tested as first-line in unresectable HCC against sorafenib in the RATIONALE 301 phase 3 trial [76] (NCT03412773; Table 2). This is currently the last trial which could bring a single agent checkpoint inhibitor regimen towards global regulatory approval. Overall, the attention and expectations have shifted to combination treatments.

Table 2.

Current clinicals trials on systemic immunotherapy in advanced HCC.

| Trial | Identifier | Phase | BCLC Stage | Treatment Arms | Primary Endpoint(s) | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMate 9DW | NCT04039607 | Phase 3 | C | Nivolumab + ipilimumab Sorafenib or lenvatinib |

OS | First-line |

| COSMIC-312 | NCT03755791 | Phase 3 | B or C | Cabozantinib + atezolizumab Sorafenib Cabozantinib |

PFS per RECIST 1.1 OS |

First-line |

| HIMALAYA | NCT03298451 | Phase 3 | B or C | Durvalumab Durvalumab + trevelimumab (2 regimens) Sorafenib |

OS | First-line |

| LEAP-002 | NCT03713593 | Phase 3 | B or C | Lenvatinib + pembrolizumab Lenvatinib |

PFS per RECIST 1.1 OS |

First-line |

| RATIONALE-301 | NCT03412773 | Phase 3 | B or C | Tislelizumab Sorafenib |

OS | First-line |

| N/A | NCT03764293 | Phase 3 | B or C | Camrelizumab (SHR-1210) + apatinib Sorafenib |

PFS OS |

First-line |

| Bayer 19497 | NCT03347292 | Phase 1b/2 | B or C | Regorafenib + pembrolizumab | Safety | First-line |

| GOING | NCT04170556 | Phase 1/2 | BCLC C | Regorafenib (monotherapy for the first 8 weeks) + nivolumab | Safety | Second-line |

| ORIENT-32 | NCT03794440 | Phase 2/3 | B or C | Sintilimab + IBI305 Sorafenib |

PFS per RECIST 1.1 OS |

First-line |

| RENOBATE | NCT04310709 | Phase 2 | B or C | Regorafenib + nivolumab | ORR per RECIST 1.1 |

First-line |

| N/A | NCT04183088 | Phase 2 | B or C | Part 1: Regorafenib + tislelizumab Part 2: Regorafenib + tislelizumab Regorafenib |

Part 1: Safety Part 2: PFS per RECIST 1.1 ORR per RECIST 1.1 |

First-line |

| N/A | NCT04442581 | Phase 2 | B or C | Cabozantinib + pembrolizumab | ORR per RECIST 1.1 | First-line |

| N/A | NCT03941873 | Phase 1/2 | B or C | Phase 1: Sitravatinib Sitravatinib + tislelizumab Phase 2: Sitravatinib Sitravatinib + tislelizumab |

Phase 1: Safety Phase 2: ORR per RECIST 1.1 |

First- and later line |

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours.

Dual therapies combining ICIs with anti-VEGF antibodies

Following the positive outcome of the IMbrave150 phase 3 trial [15], a landmark study, the strategy of combining a PD1/PD-L1 inhibitor with a VEGF inhibition has been established as a new paradigm for the treatment of advanced HCC. Initially, a phase 1b study of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in patients with untreated advanced HCC had demonstrated good safety and promising antitumor activity with an ORR of 36% and a median PFS of 7.3 months by RECIST 1.1 (95% CI: 5.4 to 9.9 months) [77]. The IMbrave150 trial then tested the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab versus sorafenib in 501 patients with advanced HCC who had not received systemic treatment previously and who were randomly assigned (2:1) to either study arm [15]. Patients received either atezolizumab at 1200 mg IV plus bevacizumab at 15 mg/kg IV once every three weeks (n = 336) or sorafenib at 400 mg bid (n = 165) until unacceptable toxicity or loss of clinical benefit. The study assessed the co-primary endpoints OS and PFS by independent review and RECIST 1.1 in the intention-to- treat population. At the data cut-off for the first analysis on August 29, 2019 and a median follow up duration of 8.6 months (8.9 months in the combination arm and 8.1 months in the sorafenib arm) treatment with atezolizumab and bevacizumab reduced the risk of death by 42% in comparison with sorafenib (HR = 0.58 [95% CI: 0.42 to 0.79]; p<0.001). The median OS was not reached for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab, and was 13.2 months for sorafenib (95% CI: 10.4 months to not reached). The median PFS per RECIST 1.1 with 6.8 months was significantly longer for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (95% CI: 5.7 to 8.3 months) than for sorafenib with 4.3 months (95% CI: 4.0 to 5.6 months; HR = 0.59 [95% CI: 0.47 to 0.76]; p<0.001). The ORRs were 27.3% (95% CI: 22.5 to 32.5%) for atezolizumab and bevacizumab vs 11.9% for sorafenib (95% CI: 7.4 to 18%; p<0.001). The frequency of grade 3–4 adverse events was similar with 56.5% for atezolizumab and bevacizumab vs. 55.1% for sorafenib. Importantly, the IMbrave150 trial excluded patients with complications due to portal hypertension such as esophageal/gastric varices at high risk of bleeding, moderate to severe ascites or a previous episode of hepatic encephalopathy.

The IMbrave150 trial has led to the approval of the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab as first-line treatment for unresectable HCC in the USA and Europe (Table 1), which has become the new standard of care replacing the TKIs sorafenib and lenvatinib. The reason behind its success lies in the likely synergistic anti-tumor activity of PD-L1 inhibition which activates the immune response (particularly T effector cells) and VEGF inhibition which reduces VEGF-mediated immunosuppression and promotes T-cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment [78].

Similar to the IMbrave150 trial, the ORIENT-32 phase 2/3 trial tested sintilimab (anti-PD1 antibody) plus IBI305 (a bevacizumab biosimilar) versus sorafenib in systemic treatment-naïve Chinese patients (NCT03794440). Sintilimab/IBI305 showed both an improved median OS and PFS relative to sorafenib (median OS: not reached vs. 10.4 months; median PFS: 4.6 vs 2.8 months) with acceptable toxicity [79].

Dual therapies combining PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors

Having been established in other cancer entities such as melanoma, the strategy of combining inhibitors of different immune checkpoints such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 is currently being explored in advanced HCC. The first clinical data came from the CheckMate 040 trial which tested nivolumab and ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody, in 148 patients with advanced HCC who had progressed on sorafenib [80]. The study had three arms: arm A with nivolumab at 1 mg/kg IV and ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg IV once every three weeks for 4 doses followed by nivolumab 240 mg IV once every two weeks (n = 50), arm B with nivolumab at 3 mg/kg IV and ipilimumab at 1 mg/kg IV once every three weeks for 4 doses followed by nivolumab 240 mg IV once every two weeks (n = 49), or arm C with nivolumab 3 mg/kg IV once every two weeks and ipilimumab 1 mg/kg IV once every six weeks (n = 49). The trial reported an ORR of 31% with a median duration of response (DOR) of 17 months, a disease control rate (DCR) of 49% and a 24-months OS rate of 40%. Patients in arm A experienced the longest median OS with 23 months. The side-effect profile was acceptable with 37% of patients having grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events. However, more than half of patients needed systemic steroids to manage side effects. Overall, the trial’s results were regarded as a success and led to the approval of the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab by the FDA (as used in the regimen of arm A; Table 1). Furthermore, the combination is currently being tested in the CheckMate 9DW phase 3 trial in the first line against sorafenib or lenvatinib in advanced HCC (CheckMate 9DW, NCT04039607).

Similarly, the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab showed robust activity with an ORR of 17.5% in unresectable HCC [81]. In the HIMALAYA trial STRIDE achieved a significantly improved OS over sorafenib (HR = 0.78 [96% CI 0.65–0.92]; p = 0.0035) while offering better tolerability (25.8% grade 3/4 trAEs with STRIDE versus 36.9% with sorafenib) [74].

Dual therapies combining checkpoint with multi-kinase inhibitors

Combining ICIs with TKIs instead of anti-VEGF antibodies may present an alternative to antibody-mediated VEGF inhibition. Several such combinations are currently being explored (Table 2).

The combination of cabozantinib and atezolizumab is being evaluated in the multi-cohort COSMIC-021 phase 1b trial in advanced solid tumors including HCC (cohort 14; NCT03170960). In addition, it is being tested in the first-line setting in patients with advanced HCC against sorafenib in the COSMIC-312 phase 3 trial [82] (NCT03755791). Here, cabozantinib monotherapy is additionally compared to sorafenib as a secondary outcome measure. Patients are randomized 6:3:1 to cabozantinib 40 mg qd and atezolizumab 1200 mg IV q3w, sorafenib 400 mg bid, or cabozantinib 60 mg qd. OS and PFS are measured as co-primary endpoints. Pending peer-reviewed publication, the study’s sponsor communicated in a press release that the trial demonstrated a significantly improved PFS for the combination treatment (HR=0.63 [99% CI: 0.44–0.91]; p=0.0012). However, a prespecified interim analysis for OS did not reach statistical significance. Results from its final analysis are expected in early 2022 [83].

The combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab was studied in a phase 1b trial and produced respectable results in 104 patients with unresectable HCC who had not received systemic treatment previously [84]. The ORRs by independent imaging review were 46.0% per mRECIST (95% CI: 36.0 to 56.3%) and 36.0% per RECIST 1.1 (95% CI, 26.6% to 46.2%). The median DORs were 8.6 months per mRECIST (95% CI: 6.9 months to not estimable) and 12.6 months per RECIST 1.1 (95% CI: 6.9 months to not estimable). Median PFS was 9.3 months per mRECIST and 8.6 months per RECIST 1.1. Median OS was 22 months. A total of 67% of patients experienced grade ≥ 3 trAEs (3% grade 5). The LEAP-002 phase 3 trial is currently testing this combination against lenvatinib monotherapy [85] (NCT03713593).

Finally, the combination of apatinib (rivoceranib, TKI) and camrelizumab (SHR1210), an anti-PD-1 antibody, is under clinical development. A phase 1 study in patients with advanced HCC reported an ORR of 50% [86]. The combination is also currently being evaluated in a phase 3 study in comparison with sorafenib in the first-line setting in patients with advanced HCC (NCT03764293).

Further currently ongoing clinical trials are mentioned in Table 2.

Systemic treatment beyond immune checkpoint inhibition

Inhibition of the immune checkpoints PD1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 is currently the most popular form of cancer immunotherapy. An alternative immune checkpoint is LAG-3 which inhibits T cell activity making it a marker of T-cell exhaustion [14]. Relatlimab is an antibody blocking LAG-3 and it is being evaluated in combination with nivolumab in the phase 2 RELATIVITY-073 trial (NCT04567615) in advanced, ICI-naive HCC after progression on prior TKI therapy [87]. Furthermore, an increasing number of alternative immunotherapeutic approaches are being explored. Such interventions may prove to be efficacious where today’s ICIs fail. For example, adoptive transfer of NK or T cells to boost infiltration of tumors is an approach that may benefit patients whose tumors are not infiltrated by effector immune cells.

Most immune interventions beyond classic checkpoint inhibition are still at a preclinical or early clinical stage and include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-) T cells, allogeneic NK cells, and oncolytic viruses (Table 3). One of the first phase 1 studies targeting Glypican 3 (GPC3) reported no dose limiting toxicity, an ORR of 16.7% and a DCR of 50% in six evaluable patients with advanced GPC3+ HCC who had received at least two lines of prior systemic therapy including the combination of TKIs and PD1/PD-L1 ICI [88] (NCT03980288). Four more phase 1 studies with CAR-T cells targeting GPC3 are currently ongoing (NCT04121273; NCT02905188; NCT03884751; NCT05003895).

Table 3.

Current clinical trials on gene and cell-based systemic treatments.

| Identifier | Phase | BCLC Stage | Treatment Arms | Primary Endpoint(s) | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02905188 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT03980288 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT05003895 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT03132792 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT04011033 | Phase 2 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT03319459 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT03841110 | Phase 1 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

| NCT03071094 | Phase 1/2 | C |

|

|

Advanced stage |

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; DCR, disease control rate; iNKT cells, invariant natural killer T cells; NK cells, natural killer cells; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

The first phase 1 trial targeting AFP is evaluating the safety and anti-tumor activity of autologous T cells expressing enhanced TCRs specific for AFP (AFPc332T) in HLA-A2 positive subjects with advanced HCC (NCT03132792). According to a recent conference presentation, the DCR in cohort 3 was 64% (7 of 11 patients, 1 CR and 6 SD) with an acceptable toxicity profile [89].

One phase 2 study is testing treatment with invariant NKT cells and TACE against TACE alone (NCT04011033). Furthermore, there are phase 1 trials which evaluate FT500, an allogeneic NK cell-line, and FATE-NK100, donor-derived NK cells, in various cancer entities including HCC (NCT03319459; NCT04106167; NCT03841110). In the field of oncolytic viruses, pexastimogene devacirepvec (Pexa-Vec) failed as second-line monotherapy in advanced HCC in the TRAVERSE phase 2b trial [90] and in combination with sorafenib in the PHOCUS trial [91] (NCT02562755; phase 3). A phase 1/2a trial is now testing Pexa-Vec in combination with nivolumab (NCT03071094).

Novel immunotherapeutic approaches hold the promise of bringing the benefits of immunotherapy to a growing number of patients. However, at this stage, success is not guaranteed and it is open which strategies will supplement or even replace the current systemic agents.

IV. Immunotherapy for Intermediate Stage HCC

The standard of care for intermediate-stage BCLC B HCC is TACE with a demonstrated improvement in overall survival [92, 93]. TACE also appears to modulate the tumor immune response [94–96]. TACE can enhance the anti-tumor immune response by decreasing Tregs and exhausted effector T cells in the tumor core, and can enhance the pro-inflammatory tumor response [95]. The safety and feasibility of tremelimumab and ablation was assessed in patients with HCC who were ineligible for liver transplantation or surgical resection (n=32) [97]. Patients received tremelimumab every 4 weeks for 6 doses. On day 36 they underwent subtotal radiofrequency ablation or TACE. Confirmed partial response was noted in 5 of 19 evaluable patients, and median OS was 19.4 months. In those patients who had a clinical benefit, 6-week tumor biopsies demonstrated an increase in CD8+ T cells. Hence, there is mechanistic rationale for the combination of immunotherapy and locoregional therapy for intermediate stage HCC.

Combination treatments

The IMbrave 150 trial also provided some data on patients with intermediate stage HCC, since it enrolled those with unresectable HCC [15]. However, the proportion of patients with intermediate stage was fairly small (~15%). Thus, it does not suffice for a final assessment of the efficacy of atezolizumab and bevacizumab in this subgroup, particularly in comparison to TACE. In order to address this open question, the ABC-HCC trial, a large investigator-initiated phase 3b trial, is testing atezolizumab and bevacizumab against TACE in patients with intermediate HCC (NCT04803994; Table 4) [98]. Another large investigator-initiated phase 3 trial in this patient population is RENOTACE, which will test the combination of regorafenib and nivolumab against TACE (NCT04777851; Table 4). Both trials have the potential to be practice changing and to establish systemic treatment in the intermediate stage. However, they face the challenge of comparing two different treatment modalities with different criteria for evaluating therapeutic success. In this regard, the ABC-HCC trial is proposing a novel kind of primary endpoint coined time to failure of treatment strategy, which measures the time until either treatment strategy (systemic treatment or TACE) is discontinued by the investigator because of failure [98]. RENOTACE, in contrast, measures PFS per mRECIST as primary endpoint which is established as a surrogate endpoint for OS and which accounts for devascularized tumor tissue.

Table 4.

Ongoing and planned clinical trials combining or comparing systemic immunotherapy with TACE.

| Trial/Identifier | Phase | BCLC Stage | Treatment Arms | Primary Endpoint(s) | Setting | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC-HCC/ NCT04803994 | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| CheckMate 74W/ NCT04340193 (not yet recruiting) | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| EMERALD-1/ NCT03778957 | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| LEAP-012/ NCT04246177 | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| RENOTACE/ NCT04777851 (not yet recruiting) | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| TACE-3/NCT04268888 | Phase 2/3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

| TALENTACE | Phase 3 | B |

|

|

First-line | ||

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; TAE, transarterial embolization.

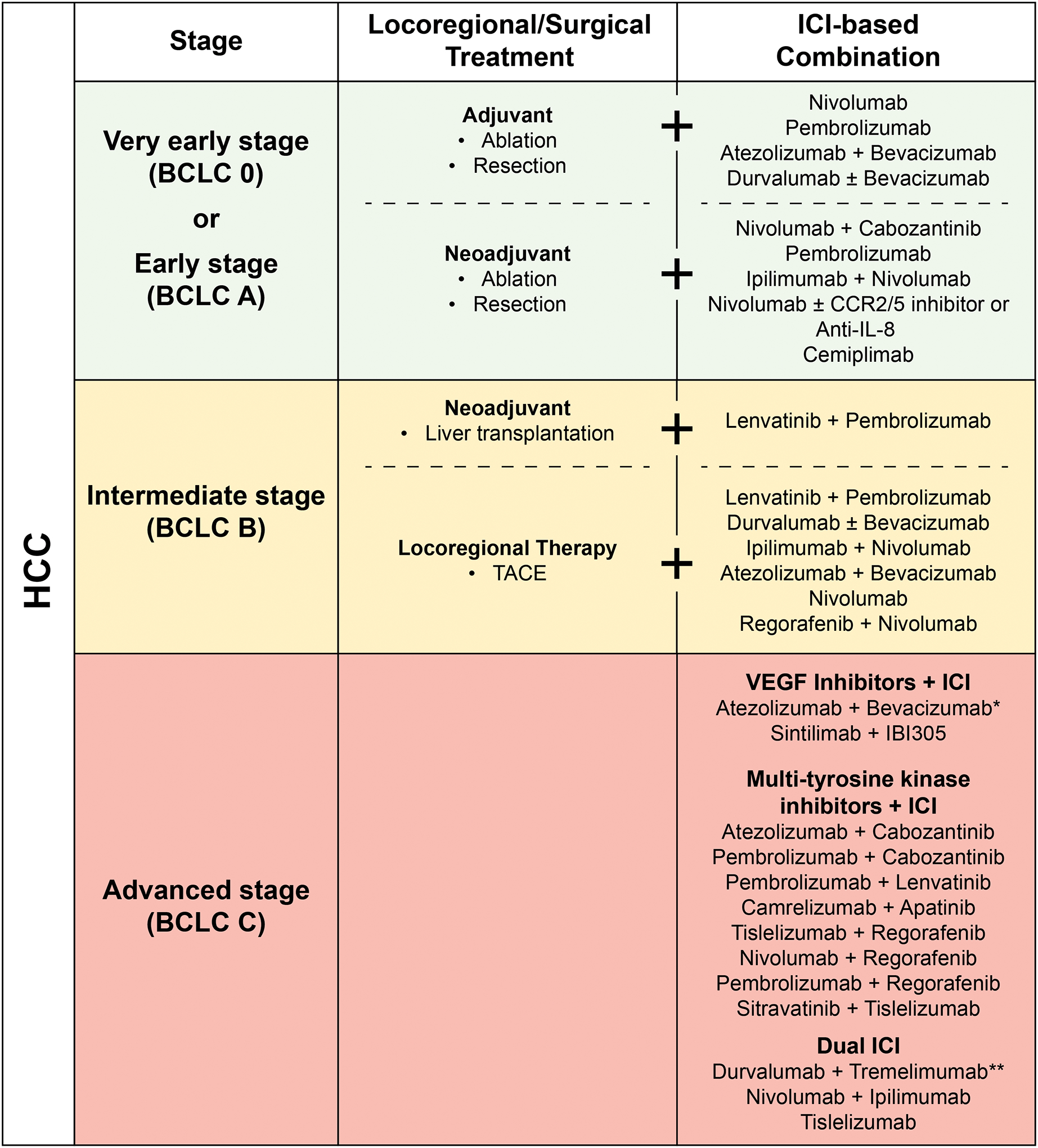

Rather than being exclusive, another option is to add systemic therapy to TACE in the intermediate stage (Figure 3). Four phase 3 trials are currently exploring this approach (Table 4): TALENTACE is testing the combination of atezolizumab, bevacizumab and TACE (NCT047126430) [99], LEAP-012 the combination of lenvatinib, pembrolizumab and TACE [100] (NCT04246177), EMERALD-1 the combination of durvalumab with or without bevacizumab and TACE [101] (NCT03778957), and CheckMate 74W the combination of nivolumab with or without ipilimumab and TACE [102] (NCT04340193) - all in comparison to TACE as the standard of care. In addition, the TACE-3 trial is comparing the combination of nivolumab and TACE/transarterial embolization (TAE) with TACE/TAE (NCT04268888).

Figure 3. Strategies integrating ICI based on HCC stage currently under investigation.

Combination strategies integrating ICI with surgical, locoregional, or other systemic therapies across HCC stages are depicted. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. *Regulatory approval in the first line setting for advanced stage HCC. ** Met primary endpoint of OS in the first-line setting for advanced stage HCC.

V. Immunotherapy for Early-Stage HCC

The current treatment options for patients with very early stage (BCLC 0) and early stage (BCLC A) HCC are surgical resection, ablation, and transplantation [54]. The primary objective of these therapies in very early and early BCLC stage HCC is cure. The 5-year survival with surgical treatments is approximately 70–80% [3]. However, recurrence following surgical resection remains a significant challenge. The 5-year rate of recurrence following surgical resection can be as high as 70% [103]. Presence of satellite lesions, cirrhosis, and thrombocytopenia are associated with recurrence [103]. Moreover, several immune factors are associated with poor outcomes following resection. Accumulation of immunosuppressive elements such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) or attenuation of cytotoxic elements such as interferon-γ, high PD-L1 expression is associated with a higher risk of recurrence [29, 104–106]. High density of CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the tumor core and margin and the corresponding Immunoscores, a score based on numeration of CD3+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in the tumor core and margin [107], are associated with a significantly low rate of recurrence following surgical resection for HCC [108]. Hence, there is a rationale to integrate immunotherapy in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting to increase the chance of cure following surgical treatments for HCC.

Adjuvant treatment

Many adjuvant approaches employing systemic treatment have failed to provide benefit after curative hepatic resection or ablation of HCC. Notably, sorafenib failed in this regard in the STORM trial [109]. CIK cells are a mixture of T lymphocytes that are expanded ex vivo with cytokines. In an open-label, phase 3 trial that included 230 HCC patients treated by surgical resection or ablation, the median survival in patients who received CIK was 44 months compared to 30 months for placebo (HR, 0.63; 95% CI 0.43–0.94; p=0.010). Four phase 3 trials in patients who have undergone curative surgery or ablation are currently ongoing (Table 5; Figure 3): CheckMate 9DX with nivolumab [110] (NCT03383458), KEYNOTE-937 with pembrolizumab [111] (NCT03867084), IMbrave 050 with atezolizumab and bevacizumab [112] (NCT04102098), and EMERALD-2 with durvalumab with or without bevacizumab [113] (NCT03847428).

Table 5.

Current clinical trials on adjuvant systemic immunotherapy after surgery or ablation.

| Trial | Identifier | Phase | BCLC Stage | Treatment Arms | Primary Endpoint(s) | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheckMate 9DX | NCT03383458 | Phase 3 | 0 or A |

|

|

Adjuvant |

| EMERALD-2 | NCT03847428 | Phase 3 | 0 or A |

|

|

Adjuvant |

| IMbrave050 | NCT04102098 | Phase 3 | 0 or A |

|

|

Adjuvant |

| KEYNOTE-937 | NCT03867084 | Phase 3 | 0 or A |

|

|

Adjuvant |

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Neoadjuvant treatment

Theoretically, in the neoadjuvant setting immune checkpoint inhibition can leverage the higher levels of tumor antigens present in the primary tumor and can promote expansion of clones of tumor specific T lymphocytes that are already present in the tumor microenvironment [114]. In preclinical models of triple-negative breast cancer, mice that underwent neoadjuvant regulatory T cell depletion using diphtheria toxin or anti-CD25 had a significantly improved long term survival (˃250 days) compared to control (≤100 days) [115]. In a subsequent study, the same investigators demonstrated that a short duration between first administration of neoadjuvant immunotherapy and resection of the primary tumor was necessary for optimal efficacy while a longer duration abrogated the efficacy of immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting [116]. In a single-arm phase 1b study, the feasibility of neoadjuvant cabozantinib and nivolumab in HCC was assessed [117]. The study enrolled 15 patients who were unresectable, and 12 of these had successful margin-negative resection following neoadjuvant therapy with cabozantinib and nivolumab. Moreover, this combination appeared to modulate the TIME as responders had an enrichment of CD138+ plasma cells and a distinct spatial rearrangement of B cells with B cells being in close proximity to other B cells. These results suggest a role for a coordinated B cell antitumor immune response.

While this is still a nascent topic, there are several early phase clinical trials being conducted (Table 6; Figure 3). The NIVOLEP trial is assessing nivolumab before and after electroporation (NCT03630640). There are several trials investigating immunotherapy in neoadjuvant setting for potentially resectable HCC: CaboNivo the combination of cabozantinib and nivolumab before hepatic resection in locally advanced/borderline resectable HCC [118] (NCT03299946); a phase 2 trial investigating pembrolizumab before and after curative ablation or resection (NCT03337841); multiple trial assessing the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab (NCT03222076; NCT0351087; NCT03682276).

Table 6.

Current clinical trials on neoadjuvant systemic immunotherapy.

| Trial/Identifier | Phase | Patient Population | Treatment Arms | Primary Endpoint(s) | Setting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURORA/ NCT03337841 | Phase 2 | N=50; Curative resection/ablation possible; Child-Pugh A; ECOG PS) | Pembrolizumab | One-year RFS rate | Neoadjuvant & adjuvant | |

| CaboNivo/ NCT03299946 | Phase 1b | Locally advanced/borderling resectable HCC; BCLC A or B; ECOG 0–1 | Cabozantinib + nivolumab | Safety | Neoadjuvant | |

| NCT03222076 | Phase 2 | N=30; Resectable HCC; Prior therapy allowed; Child-Pugh A; ECOG PS 0–1; | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Safety | Neoadjuvant | |

| NCT0351087 | Phase 2 | N=40; Resectable HCC; Child-Pugh A; ECOG 0–1 | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Objective response | Neoadjuvant | |

| NCT04123379 | Phase 2 | N=50; resectable HCC; ECOG 0–1 | Nivolumab ± CCR2/5 inhibitor or Anti-IL-8 | <10% viable tumor at time of surgery | Neoadjuvant | |

| NCT03916627 | Phase 2 | N=94; resectable HCC; ECOG 0–1 | Cemiplimab | Significant tumor necrosis | Neoadjuvant | |

| NIVOLEP/ NCT03630640 | Phase 2 | N=50; Advanced HCC treated by electroporation; BCLC A or B; ECOG ≤2 | Nivolumab | Local RFS | Neoadjuvant & adjuvant | |

| PLENTY202001 | Phase 2 | HCC beyond Milan; Child-Pugh A-B7; ECOG 0–1 | Pembrolizumab + Lenvatinib No intervention | RFS | Neoadjuvant | |

| Prime-HCC/NCT03682276 | Phase 1/2 | N=32; HCC ineligible for liver transplantation; Child-Pugh A; ECOG PS 0–1 | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab | Safety; delay to surgery | Neoadjuvant | |

locally advanced/borderline resectable HCC;

HCC exceeding Milan criteria.

BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; N/A, not available; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Immunotherapy is also being evaluated in the neoadjuvant setting in liver transplantation. PLENTY202001 is testing the combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab before liver transplantation in patients with HCC exceeding the Milan criteria (NCT04425226; Figure 3). The use of ICIs in the transplant setting carries significant safety risks, since it may cause allograft rejection with potentially fatal consequences [119]. Therefore, clinical trials involving ICIs typically exclude solid organ recipients. The PLENTY202001 is a rare exception and will gather highly relevant safety information in this respect.

VII. Management of immunotherapy toxicities

Immune-related adverse events

Immune checkpoint molecules play a key role in the context of immune homeostasis. In particular, inhibitory immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1 or CTL-4 are essential for balancing T-cell activation and self-tolerance [120, 121]. Thus, ICIs targeting PD-1 (or its ligand PD-L1) or CTL-4 may cause a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) by enhancing self-immunity. IrAEs can potentially affect every organ system and range from low-grade rash to life-threatening complications.

The risk of irAEs driven by PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition is dose-independent [122]. A meta-analysis comprising 12,808 patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs reported an overall incidence of irAEs of 26.82% (95% CI: 21.73–32.61) irrespective of grade, 6.10% (95% CI: 4.85–7.64) grade ≥ 3 events and 0.17% lethal events. In contrast to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents, the risk of anti-CTL-4-related irAEs is dose-dependent [123]. According to a meta-analysis including 1,265 patients, the overall incidence of anti-CTL-4-related irAEs of any grade was 72% (95% CI: 65–79). Grade ≥ 3 events occurred in 24% (95% CI: 18–30), lethal events in 0.86% [123]. Regarding both anti-CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, the most frequently affected organ systems were the skin and the gastrointestinal tract, whereas the liver and endocrine system were less frequently affected [122, 123]. Another meta-analysis including 21 randomized controlled phase II/III trials with a total of 6,528 patients treated with ICIs reported rash as the most frequent all-grade irAE (13.9%; 95% CI: 10.6–18.0) and both colitis and AST-elevation as the most common high-grade irAEs (1.5 %; 95% CI: 0.9–2.5 and 1.5%; 95% CI: 0.7–3.4) [124]. Compared to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents, ipilimumab was associated with a significant higher risk of rash (all grades, relative risk (RR) 3.94; 95% CI: 3.02–5.14 vs RR 1.59; 95% CI: 0.90–2.82) and colitis (high grade, RR 22.5, 95% CI: 6.37–79.4 vs RR 2.47, 95% CI: 0.90–6.72) [124]. The overall incidence of lethal irAEs was 0.64% [124]. Importantly, no HCC trials were included in these large meta-analyses. To give an overview of the safety of ICIs in patients with HCC, frequencies of irAEs reported from major clinical trials in this patient population are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Immune-related adverse events reported from clinical trials with ICIs in HCC.

| IMbrave 150 [15] Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab Phase III |

CheckMate 040 [68] Nivolumab Phase I/II |

CheckMate 040 [80] Nivolumab + Ipilimumab Phase I/II |

KEYNOTE 224 [71] Pembrolizumab Phase II |

KEYNOTE-240 [72] Pembrolizumab Phase III |

NCT02519348 [75] Durvalumab + tremelimumab Phase I/II |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (intervention arm) | 329 | 48 | 49 | 49 | 48 | 104 | 279 | 74 |

| Dosing | 1200 mg atezolizumab + 15 mg/kg bevacizumab q3w | All doses tested in the dose-escalation phase | arm A† | arm B†† | arm C††† | 200 mg pembrolizumab q3w | 200 mg pembrolizumab q3w | T300 + D* |

| n (%) | ||||||||

| irAEs | ||||||||

| any grade | 226 (68.7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15 (14.4) | 51 (18.3) | 23 (31.1) |

| grade ≥3 | 85 (25.8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 (4) | 20 (7.2) | 9 (12.2) |

| irAEs leading to discontinuation of treatment | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9 (12.2)** |

| Skin | ||||||||

| Rash | ||||||||

| any grade | 64 (19.5) | 15 (31) | 17 (35)a / 0c | 14 (29)a / 1 (2)c | 8 (17)a / 0c | 10 (10)*** | 32 (11.5) | 3 (4.1) |

| grade ≥3 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 3 (6)a / 0c | 2 (4)a / 1 (2)c | 0a / 0c | 0*** | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pruritus | ||||||||

| any grade | 43 (13.1)*** | 13 (27) | 22 (45)*** | 16 (33)*** | 14 (29)*** | 12 (12)*** | 51 (18.3) | 0 |

| grade ≥3 | 0*** | 0 | 2 (4)*** | 0*** | 0*** | 0*** | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| GI tract | ||||||||

| Colitis | ||||||||

| any grade | 6 (1.8) | N/A | 5 (10)a,b / 2 (4)b,c | 1 (2)a,b / 0b,c | 1 (2)a,b / 0b,c | 2 (2)***** | 4 (1.4)X | 3 (4.1) |

| grade ≥3 | 2 (0.6) | N/A | 3 (6)a,b / 2 (4)b,c | 1 (2)a,b / 0b,c | 1 (2)a,b / 0b,c | 0 | 2 (0.7)x | 2 (2.7) |

| Diarrhoea | ||||||||

| any grade | 34 (10.3)*** | 15 (31) | 11 (11)*** | 48 (17.2) | 5 (6.8) | |||

| grade ≥3 | 1 (0.3)*** | 1 (2) | 0*** | 4 (1.4) | 0 | |||

| Liver | ||||||||

| Hepatitis | ||||||||

| any grade | 43 (13.1)**** | 2 (4) | 10 (20)a / 3 (6)c | 6 (12)a / 2 (4)c | 3 (6)a / 0c | 3 (3) | 5 (1.8) | 0 |

| grade ≥3 | 23 (7.0)**** | 2 (4) | 10 (20)a / 2 (4)c | 5 (10)a / 2 (4)c | 3 (6)a / 0c | 3 (3) | 4 (1.4) | 0 |

| Endocrine organs | ||||||||

| Adrenal insufficency | ||||||||

| any grade | 1 (0.3) | 1 (2) | 9 (18)a / 0c | 3 (6)a / 0c | 3 (6)a / 0c | 3 (3) | 2 (0.7) | N/A |

| grade ≥3 | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (4)a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Hypothroidism | ||||||||

| any grade | 36 (10.9) | 2 (4) | 10 (20)a / 0c | 5 (10)a / 0c | 6 (13)a / 1 (2)c | 8 (8) | 14 (5.0) | 4 (5.4) |

| grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Hyperthyroidism | ||||||||

| any grade | 15 (4.6) | N/A | 5 (10)a / 0c | 4 (8)a / 0c | 3 (6)a / 0c | 1 (1) | 9 (3.2) | 3 (4.1) |

| grade ≥3 | 1 (0.3) | N/A | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Hypophysitis | ||||||||

| any grade | N/A | N/A | 2 (4)a / 0c | 1 (2)a / 0c | 1 (2)a / 0c | N/A | 2 (0.7) | 0 |

| grade ≥3 | N/A | N/A | 0a / 0c | 1 (2)a / 0c | 1 (2)a / 0c | N/A | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Lung | ||||||||

| Pneumonitis | ||||||||

| any grade | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 5 (10)a / 3 (6)c | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | N/A | 10 (3.6) | 1 (1.4) |

| grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 3 (6)a / 2 (4)c | 0a / 0c | 0a / 0c | N/A | 4 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

Arm A: 1 mg/kg nivolumab + 3 mg/kg ipilimumab q3w (4 doses), followed by 240 mg nivolumab q2w.

Arm B: 3 mg/kg nivolumab plus 1 mg/kg ipilimumab q3w (4 doses), followed by 240 mg nivolumab q2w.

Arm C: 3 mg/kg nivolumab q2w plus 1 mg/kg ipilimumab q6w.

irAEs which required immunosuppressive treattment.

Diarrhoea/colitis combined.

irAEs leading to discontinuation.

T300 + D: 300 mg tremelimuab + 1,500 mg durvalumab (one dose), followed by 1,500 mg duvalumab q4w (this dosing regimen showed the best risk-benefit profile).

Any adverse event resulting in discontinuation of treatment.

Listed as treatment-related adverse event.

Includes only hepatitis (diagnosis), not hepatitis (laboratory abnormality).

Includes autoimmune colitis and colitis.

Includes colitis, enterocolitis and autoimmune colitis.

N/A: not available, irAEs: immune-related adverse events.

Management of irAEs

Hepatologists face several challenges in diagnosing and managing irAEs since they are associated with a broad range of complicating factors in the context of HCC. First, liver cirrhosis itself leads to progressive immune dysfunction including both immune deficiency and systemic inflammation [125]. Thus, the liver-related immune homeostasis is already severely compromised in these patients. Second, cirrhosis-driven hepatic and extrahepatic complications may overlap with or exacerbate symptoms caused by irAEs, thereby hampering their early and rapid diagnosis, which is mandatory regarding the outcome of potentially life-threatening events [126]. Thus, careful selection and evaluation of patients with HCC prior to ICI therapy should be performed [126].

In general, the management of irAEs is based on three pillars. First, close monitoring is mandatory, including weekly clinical controls up to hospitalization depending on the severity of events. Importantly, patients with high-grade irAEs should be referred to a specialized center already at an early stage. This is particularly important in patients with liver cirrhosis, as the differential diagnosis between cirrhosis-associated complications and irAEs can be challenging, and premature termination of an effective anti-tumor therapy or initiation of a steroid therapy in cirrhotic patients may have severe consequences [126].

Second, temporary interruption or permanent discontinuation of ICI therapy depending on the type and severity of irAEs may be necessary. In general, permanent discontinuation of ICI therapy should be considered for irAEs of grade ≥ 3, apart from PD-1/PD-L1-driven rash, nephritis, adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism, which resolve within one month after discontinuation [126]. However, re-exposure to ICI therapy after discontinuation is associated with a relevant risk of recurrence of irAEs: In a cohort study comprising 93 patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents presenting with irAEs of grade ≥ 2, recurrence of irAEs occurred in 22 (55%) of 40 patients, who received the same agent after discontinuation [127]. While recurrence of irAEs was associated with a more rapid onset of the initial irAE, the recurrent irAEs did not differ in terms of severity [127].

Third, administration of glucocorticoids for irAEs of grade ≥ 2 may be indicated (0.5 up to 2 mg/kg/day prednisone PO or IV depending on the type and severity of irAEs).

Cutaneous irAEs, ranging from frequently observed rash or pruritus to very less common but more severe disorders such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, are treated with topical, oral or intravenous glucocorticoids and topical or oral antihistamines depending on the severity of clinical presentation [126]. Steroids should be continued until clinical signs resolve (at least 3 days) and tapered over one to four weeks [128, 129].

Regarding gastrointestinal irAEs, including particularly colitis and/or diarrhoea, differential diagnosis is mandatory, especially to exclude infectious diseases and drug side effects (in particular new administration or dosage adjustments of lactulose due to hepatic encephalopathy) [126]. For grade 2 glucocorticoids can be administered, and for grade ≥3 glucocorticoids should be started and hospitalization including sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy should be considered. In case of glucocorticoid failure, immunosuppressive therapy e.g. with infliximab or vedolizumab should be added early [126, 130]. Tapering should be done over 2–8 weeks depending on steroid response and severity of clinical presentation [128, 129].

The diagnosis and management of immune-related hepatitis in patients with HCC undergoing ICI therapy is particularly challenging. Importantly, up to 20% of placebo-treated patients present with any grade AST elevation [126]. Thus, early consultation of an experienced hepatologist is strongly recommended. Before diagnosing immune-related hepatitis, intrahepatic tumor progression, HBV and/or HCV flares or newly acquired viral hepatitis, CMV reactivation, hepatotoxic drug side effects, cholestasis and ascites should be excluded [126]. In addition, a liver biopsy should be considered prior to steroid administration. Upon diagnosis of immune-related hepatitis, oral or intravenous steroids may be administered for grade 2 and should be administered for grade ≥3 [126]. After toxicity resolves, tapering should be done over 4–6 weeks [126, 128, 129].

Pneumonitis represents a potential life-threating irAE. Therefore, the suspicion of pneumonitis should be followed by a rapid and comprehensive differential diagnosis, including exclusion of infectious etiologies, porto-pulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome [126]. For grade 2, steroids should be initiated and tapering should be performed over 4–6 weeks [128]. Infliximab or mycophenolate mofetil may be used after glucocorticoid failure [126].

Thyroid-associated irAEs include hypo- and hyperthyroidism as a consequence of thyroiditis. A progressive decrease of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in combination with normal or decreased levels of thyroxine (T4) should prompt regular cortisol measurements to rule out immune-related hypopituitarism [129]. Regarding hypothyroidism, T4 substitution is indicated only in symptomatic patients [129]. In symptomatic hyperthyroid patients, thyroid antibodies and uptake should be measured, and administration of beta-blockers and/or carbimazole should be considered [129]. Asymptomatic patients require no specific therapy and ICI treatment should be continued.

Patients undergoing ICI therapy should receive regular testing of both TSH and free T4. Each pituitary hormone axes should be screened, if central hypothyroidism is suspected [126]. This includes cortisol (drawn at 9 am), ACTH, CRH, TSH, free T4, LH, FSH, oestradiol (premenopausal women), testosterone (men), IGF-1 and electrolytes [126, 128, 129]. In addition, cranial MRI should be considered. Treatment of symptomatic patients comprises initiation of steroids (1–2 mg/kg/day of prednisone oral or intravenous depending on severity) with a tapering regimen of 1–4 weeks and hormone replacement (e.g. starting with 100 mg hydrocortisone IV and levothyroxine 0.5–1.5 μg/kg/day) [128, 129]. Regarding primary adrenal insufficiency, management includes administration of hydrocortisone and, if necessary, fludrocortisone (dosage depends on severity), followed by tapering over 5–14 days depending on symptoms [128].

VIII. Unmet Needs/Future Directions

The approval and therapeutic success of the first ICIs in advanced HCC has heralded in a new era of cancer immunotherapy for this disease. Three main questions remain to be solved by the field:

Does immunotherapy provide a benefit in earlier disease stages?

Which immune interventions other than PD-1/PD-L1/CTLA-4 inhibition have anti-tumor activity in HCC?

What are the treatment options for patients who do not respond to the currently available ICIs?

Regarding the first question, several clinical trials are exploring the use of ICIs in the intermediate and early stage. In the former, it is unclear whether checkpoint inhibitor containing regimens represent an alternative or an addition to TACE, the standard of care. The ABC-HCC and RENOTACE trials will evaluate the combinations of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and regorafenib plus nivolumab as an alternative. ABC-HCC recruits the whole spectrum of intermediate stage disease, while RENOTACE focuses on patients exceeding the up-to-seven criteria, i.e. the subgroup which has a higher tumor burden and is thus more advanced. The LEAP-012, EMERALD-1 and CheckMate 74W trials will test lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, durvalumab (plus bevacizumab) and nivolumab (plus ipilimumab) in addition to TACE. In addition, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and durvalumab plus bevacizumab are being evaluated as adjuvant treatment after surgery or ablation. Furthermore, the first trials evaluating ICIs for neoadjuvant strategies are being conducted. Taken together, this set of trials will investigate the efficacy and safety of immunotherapy in the early and intermediate stage from different angles and provide high quality data which will certainly help to clarify the role of checkpoint inhibition in these settings.

Regarding the second question, the targeting of other immune checkpoints such as LAG-3, the use of engineered immune cells such as CAR-T/-NK cells and the utilization of oncolytic viruses are under clinical development and may produce meaningful responses in patients who are unresponsive or have stopped responding to treatment with the established ICIs.

These novel immunotherapeutic approaches may also be part of the answer to the third question. However, it is likely that a subgroup of patients such as those with an immune desert tumor microenvironment will benefit less from immunotherapy. For such patients, the current and future targeted agents will be highly relevant, and exploration of novel therapeutic targets should not be neglected despite the impressive achievements by immunotherapy.

Key points.

Systemic treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors is a new paradigm in the treatment of advanced HCC. The combination of atezolizumab/bevacizumab is the first treatment which has won regulatory approval in the first-line setting. Other combination treatments are expected to follow in the near future.

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors may also be efficacious at earlier disease stages. Several combination treatments are being evaluated in addition to or against transarterial chemoembolization, the current standard of care in the intermediate stage. In addition, immune checkpoint inhibitors are being explored as adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments in the context of surgery or ablation in the early and very early stage.

Emerging evidence suggests there is a link between regulation of commensal gut microbiome and liver antitumor immunity.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are known to cause immune-related adverse events. However, the frequency of grade 3/4 events has been moderate in clinical trials of HCC. Therefore, immune checkpoint inhibitors are generally regarded as safe in patients with HCC.

Financial Support:

SJG is supported by the Clinician Scientist Fellowship “Else Kröner Research College: 2018_Kolleg.05”. SII is supported by the National Cancer Institute (K08 CA 236874) and the Hepatobiliary Cancer SPORE (P50 CA210964). Otherwise, this work was not financially supported by any grant or funding source.

List of Abbreviations:

- ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- Breg

Regulatory B cells

- CAR-T cells

Chimeric antigen receptor T cells

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIK

Cytokine-induced killer

- CRH

Corticotropin-releasing hormone

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated Protein 4

- CXCR3

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3-positive

- DC

Dendritic cells

- DCR

Disease control rate

- DOR

Duration of response

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FSH

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- GPC3

Glypican 3

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- irAEs

Immune-related adverse events

- LAG-3

Lymphocyte-activation gene 3

- LH

Luteinizing hormone

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- NASH

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- NKT

Natural killer T

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- PDE5

Phosphodiesterase-5

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- Pexa-Vec

Pexastimogene devacirepvec

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- T4

Thyroxine

- TACE

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TAE

Transarterial embolization

- TAMS

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor β

- TIM3

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 3

- TIME

Tumor immune microenvironment

- TKIs

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- trAEs

Treatment-related adverse events

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- TSH

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VISTA

V-domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T cell activation

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

FF reports receiving consulting and lectures fees from Roche; lectures fees from Lilly and Pfizer. SJG report no conflict of interest. SII reports receiving consulting fees from AstraZeneca. PRG reports receiving consulting and lectures fees from Adaptimmune, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boston Scientific, Eisai, Guerbet, Ipsen, Lilly, MSD, Roche, Sirtex.

References