Abstract

Aiming to develop a DNA marker specific for Bacillus anthracis and able to discriminate this species from Bacillus cereus, Bacillus thuringiensis, and Bacillus mycoides, we applied the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting technique to a collection of 101 strains of the genus Bacillus, including 61 strains of the B. cereus group. An 838-bp RAPD marker (SG-850) specific for B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, B. anthracis, and B. mycoides was identified. This fragment included a putative (366-nucleotide) open reading frame highly homologous to the ypuA gene of Bacillus subtilis. The restriction analysis of the SG-850 fragment with AluI distinguished B. anthracis from the other species of the B. cereus group.

The Bacillus cereus group encompasses four species: Bacillus anthracis, B. cereus, Bacillus mycoides, and Bacillus thuringiensis (10). B. anthracis is the active agent of anthrax disease (34). B. cereus causes food-borne disease syndromes associated with enterotoxin and emetic toxin (15, 20). B. thuringiensis is an insect pathogen (2), and it is widely used for the biological control of insects in crop protection. B. mycoides has been recently recognized as a plant growth-promoting bacterium associated with conifer roots (25). Although the natural habitat of these bacteria is the soil, they should be considered ubiquitous organisms. Owing to their ability to form spores, these organisms are very resistant to environmental stresses and are widespread in the environment. For example, B. cereus is frequently found in milk products, rice spoilage (10), and other environmental matrices such as artistic stonework (26).

Although the four species were included as separate taxa in the 1980 Approved List of Bacterial Names (33) and DNA hybridization studies have justified the separation (21, 22), they are often indistinguishable in comparisons of the 16S and 23S rRNA sequences (3–5) and the 16S-23S rRNA (9, 18) and gyrB-gyrA (DNA gyrase) intergenic spacer regions (18).

The availability of suitable markers to distinguish B. anthracis from the other species of the B. cereus group remains an actual need, as shown in the recent anthrax outbreaks that occurred in France in 1997 (24). The discrimination of Bacillus spp. isolated from soil from B. anthracis strains, by using available B. anthracis-specific DNA markers such as the chromosomal marker BA813 (23) and the variable-number tandem repeats in the vrrA gene (19), failed, suggesting that these DNA traits may be present in strains other than B. anthracis.

The randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting technique (35, 36) has been proposed (6, 17) as a tool for generating taxon-specific markers with different specificities (13) and was successfully applied to the detection of Azospirillum strains in a soil microcosm (16). Recently, Andersen et al. (1) developed a pair of primers in an open reading frame (ORF) (vrrA) within an arbitrarily primed PCR amplicon that was able to distinguish B. anthracis strains from the type strains of B. cereus and B. mycoides.

The aim of our study was to select an RAPD marker specific for the B. cereus group and useful in diagnosis for the discrimination of B. anthracis.

A total of 101 Bacillus strains of different origins and/or from different sources were used in the study (Table 1). All the strains were cultivated under the conditions previously described (8, 11, 12). The environmental isolates of the B. cereus group were assigned to the group by PCR amplification of a region of the cerA gene (Table 1) specific for the B. cereus group (32) and by tDNA-PCR fingerprinting (8). The identification was confirmed by the API 20 NE and API 50 CHB tests (bioMerieux, Milan, Italy).

TABLE 1.

Bacillus strains screened with cerA and SG-749 PCR and restriction groups obtained by cutting the SG-749 fragment with the endonuclease AluI

| No. of isolate | Species | Strain (collection)a | Source | Result of PCR for:

|

AluI restriction haplotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cerA | SG-749 | |||||

| 1 | B. cereus | 31T (DSMZ) | + | + | A | |

| 2 | 345 (DSMZ) | + | + | A | ||

| 3 | 351 (DSMZ) | + | + | A | ||

| 4 | 626 (DSMZ) | + | + | A | ||

| 5 | 2896 (DSMZ) | + | + | A | ||

| 6 | CER3 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | A | |

| 7 | CO1 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | A | |

| 8 | CO2 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | A | |

| 9 | MY1 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | A | |

| 10 | MYd (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | A | |

| 11 | 487 (DSMZ) | + | + | B | ||

| 12 | 6127 (DSMZ) | + | + | B | ||

| 13 | 46321 (DSMZ) | + | + | B | ||

| 14 | CER4 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | B | |

| 15 | PO1 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | B | |

| 16 | CER5 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | C | |

| 17 | 318 (DSMZ) | + | + | E | ||

| 18 | 336 (DSMZ) | + | + | E | ||

| 19 | 360 (DSMZ) | + | + | F | ||

| 20 | BC2 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | G | |

| 21 | CER1 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | G | |

| 22 | CER6 (DISTAM) | A. Galli | + | + | H | |

| 23 | BC1 (DISTAM) | + | + | I | ||

| 24 | B. thuringiensis | 2046T (DSMZ) | + | + | A | |

| 25 | 5724 (DSMZ) | + | + | A | ||

| 26 | 5725 (DSMZ) | + | + | C | ||

| 27 | A1 (DISTAM) | L. Allievi | + | + | C | |

| 28 | B. mycoides | 303 (DSMZ) | + | + | C | |

| 29 | BM S (DISTAM) | + | + | D | ||

| 30 | 2048T (DSMZ) | + | + | G | ||

| 31 | 299 (DSMZ) | + | + | G | ||

| 32 | 309 (DSMZ) | + | + | G | ||

| 33 | 384 (DSMZ) | + | + | G | ||

| 34 | 307 (DSMZ) | + | + | J | ||

| 35 | B. anthracis | ANT 2522 (IZF) | M. Luini | + | + | K |

| 36 | ANTmi (IZF) | M. Luini | + | + | K | |

| 37 | CEB 7700 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 38 | CEB 7702 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 39 | CEB 4229 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 40 | CEB 6602 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 41 | CEB Cepanzo | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 42 | CEB Davis TE702 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 43 | CEB 957 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 44 | CEB 227 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 45 | CEB 170 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 46 | CEB 300 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 47 | CEB 779 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 48 | CEB 832 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 49 | CEB 663 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 50 | CEB 376 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 51 | CEB 846 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 52 | CEB 256 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 53 | CEB 582 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 54 | CEB 282 | M. Mock | + | + | K | |

| 55 | 6445/RA3 | M. Mock | NDb | + | K | |

| 56 | 6445/RA3R | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 57 | 6687/4896/L | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 58 | 6769 | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 59 | 7611 | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 60 | 7611R | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 61 | 9240 | M. Mock | ND | + | K | |

| 62 | B. subtilis | 8633 (ATCC) | L. Allievi | − | − | NAc |

| 63 | BSU (DISTAM) | − | − | NA | ||

| 64 | 347 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 65 | B. amyloliquefaciens | 7T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 66 | BAM (DISTAM) | − | − | NA | ||

| 67 | B. pumilus | 27T (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 68 | B. licheniformis | 14580T (ATCC) | C. Parini | − | − | NA |

| 69 | 13T (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 70 | 3.2 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 71 | 17.1 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 72 | 61.1 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 73 | 75.2 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 74 | 283.A (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 75 | F1 4 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 76 | F1 11 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 77 | MP3 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 78 | 4-40 (MIM) | C. Parini | − | − | NA | |

| 79 | B. brevis | 30T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 80 | B. circulans | 11T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 81 | B. coagulans | 1T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 82 | 9365 (NCIB) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 83 | B. megaterium | 32T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 84 | B. pasteurii | 33T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 85 | B. polymyxa | 36T (DSMZ) | − | − | NA | |

| 86 | B. smithii | 4216 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 87 | B. sphaericus | 461 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 88 | B. stearothermophilus | 22T (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 89 | 12980T (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 90 | 29609 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 91 | 12016 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 92 | 21365 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 93 | 10339 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA | |

| 94 | B. acidocaldarius | 2000 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 95 | “B. caldotenax” | 406 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 96 | “B. caldovelox” | 411 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 97 | “B. caldolyticus” | 405 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 98 | “B. flavothermus” | 2641 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 99 | B. thermocatenulatus | 730 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 100 | B. thermodenitrificans | 465 (DSMZ) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

| 101 | B. thermoleovorans | 43513 (ATCC) | D. Mora | − | − | NA |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. DISTAM, Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Alimentari e Microbiologiche, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy. DSMZ, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany. IZF, Istituto Zooprofilattico, Milan, Italy. MIM, Microbiologia Industriale Milano, Milan, Italy. NCIB, National Collection of Industrial Bacteria, Aberdeen, Scotland.

ND, not determined.

NA, not applicable.

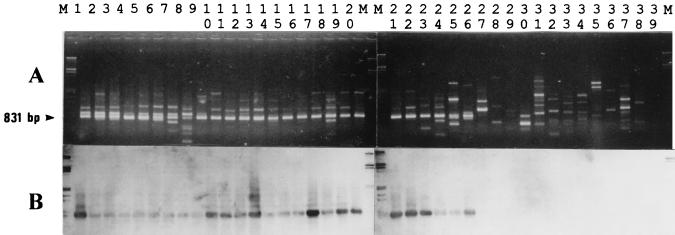

For RAPD screenings, total DNA was extracted from bacterial cells by lysis accomplished by boiling them in the presence of Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) as previously described (8, 12, 14), and amplifications were carried out under the conditions described elsewhere (12). When analyzed by RAPD fingerprinting, the strains of B. cereus showed a very high degree of variability (12). Interestingly, the RAPD patterns obtained with primer OPG-8 (5′-TCACGTCCAC-3′; Operon Technologies, Alameda, Calif.) showed in all strains of the B. cereus group a shared amplicon of about 850 bp (SG-850; Fig. 1A), which was also amplified by RAPD under more stringent conditions, with annealing temperatures of 40, 45, and 50°C (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Identification of the SG-850 RAPD marker for the B. cereus group strains by RAPD fingerprinting of Bacillus strains obtained by amplifying total DNA with primer OPG-8 (A) and Southern hybridization of the RAPD patterns with the SG-850 DIG-labelled probe obtained from B. cereus 2896 (B). Lanes M, DNA size markers (EcoRI-, HindIII-digested lambda DNA, DIG labelled; Boehringer Mannheim). Lanes 1 to 22, B. cereus 31T, 318, 336, 6127, 46321, CER4, 487, CER6, 360, 345, 351, 626, 2896, BC1, BC2, CER1, CER3, CER5, MY1, MYd, CO1, and CO2. Lanes 23 and 24, B. thuringiensis 2046T and A1. Lane 25, B. mycoides 2048T. Lane 26, B. cereus PO1. Lanes 27 to 39, B. sphaericus 461, B. coagulans 1T, B. amyloliquefaciens 7T, B. circulans 11T, B. brevis 30T, B. smithii 4216, B. megaterium 32T, B. pasteurii 33T, B. polymyxa 36T, B. amyloliquefaciens BAM, B. subtilis 8633, B. licheniformis 14580T, and a negative control.

The specificity of the SG-850 fragment was tested in Southern hybridization experiments with, as a probe, the 850-bp fragment from B. cereus 2896, excised from the agarose gel with the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and labelled with digoxigenin (DIG) by random priming. Labelling, prehybridization, hybridization, and detection were performed with the DIG DNA labelling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (7). Results showed that the SG-850 RAPD fragment specifically hybridized only with the 850-bp fragment of the B. cereus group strains (Fig. 1B).

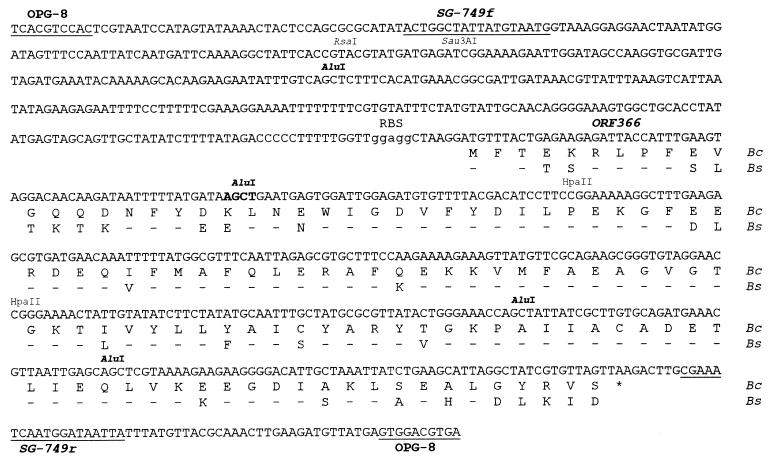

For DNA sequencing, the selected RAPD marker from B. cereus 336 was cloned into the plasmid vector pCRII, supplied in the Invitrogen TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sequencing of RAPD marker SG-850 was performed by using the standard technique described by Sanger et al. (31). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed that the fragment was 838 bp with a G+C content of 31.1% and, as expected, showed the OPG-8 sequence at both ends of the marker, suggesting that no rearrangement had occurred during the amplification and/or cloning (Fig. 2). The nucleotide sequence was compared with those contained in other databases by using the Wu-Blastn program. The analysis revealed that the 3′ half of the fragment had a very high degree of sequence similarity [P(N) 1.5e−37] with a region of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome harboring the 1,926-bp ypuA gene (28), which encodes a putative protein with a very high degree of sequence similarity with the Escherichia coli dinG gene. In contrast, the 5′ half of the fragment did not reveal a significant degree of sequence similarity with any sequence contained in the databases. A search for ORF revealed the presence of a 366-nucleotide (nt) ORF (ORF366) encoding a putative protein of 122 amino acids (aa), with most codons (73%) ending in A or T, in agreement with the G+C content of the fragment. The amino acid sequence of the putative protein was compared with the available sequences in other databases by using the tBlastn program, which gave a very high score [P(N) 6.9e−64] for the 641-aa protein of B. subtilis encoded by the ypuA gene. The alignment of the two sequences revealed that B. cereus ORF366 showed a very high degree of sequence similarity (76% identity and 94% similarity) with the first 121 aa of the YpuA protein (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the SG-850 RAPD marker from B. cereus 336. Regions that are underlined represent the target sequences of primer OPG-8, SG-749f, or SG-749r. The recognition sites of the restriction endonuclease AluI (and those of others) are also indicated. The B. cereus (Bc) ORF366, spanning nt 404 to 773, encodes an amino acid sequence (shown below the nucleotide sequence in the single-letter code) homologous to the B. subtilis (Bs) YpuA protein. Hyphens represent residues identical in the B. cereus ORF366 and the B. subtilis YpuA protein; RBS indicates the putative ribosome binding site upstream from the ORF366.

In order to use the SG-850 fragment as a PCR-specific marker for strains of the B. cereus group, two primers of 19 and 20 bp, located 48 and 41 nt, respectively, from the ends of the fragment (Fig. 2) and referred to as SG-749f (5′-ACTGGCTAATTATGTAATG-3′) and SG-749r (5′-ATAATTATCCATTGATTTCG-3′), were designed to obtain an amplicon of 749 bp (SG-749). The efficiencies of these primers, purchased from Amersham Pharmacia, Milan, Italy, were tested in PCR experiments with each of the strains listed in Table 1. The PCRs were performed in a 50-μl final volume, containing 5 μl of 10× buffer (Promega), 50 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.7 μM concentrations of each primer, 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Promega), and 1 μl of the DNA solution. The reaction mixture was covered with 40 μl of mineral oil. Amplification was performed in a model PTC-100 DNA thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) with the following parameters: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 38 cycles, consisting of steps at 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (30). The expected SG-749 fragment was amplified only in members of the B. cereus group (Table 1), suggesting that the SG-749 fragment could be proficiently used for the rapid identification of B. cereus group isolates. The amplification of the SG-749 fragment was obtained from the DNAs of virulent and avirulent strains of B. anthracis, i.e., also from the strains that were cured of one or both of the pXO plasmids (23, 27), showing that the SG-749 fragment is probably located on the chromosome.

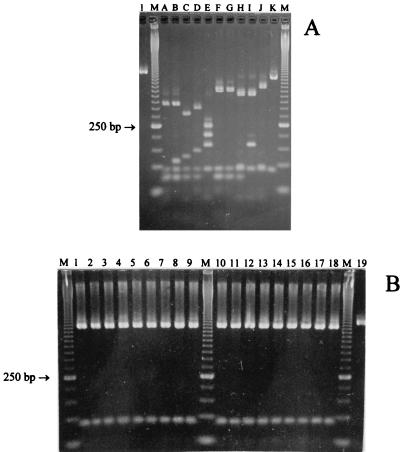

The amplified fragment was characterized in all 61 strains of the B. cereus group by restriction analysis with the endonuclease AluI (Amersham Pharmacia). Five microliters of the amplified product was digested with 5 to 8 U of enzyme and the buffer provided by the manufacturer and analyzed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis (30). AluI discriminated 11 groups (Fig. 3A and Table 1) showing a wide sequence diversity among the isolates. Such sequence diversity explains the different intensities of the hybridization signals found in the Southern hybridization experiment among the strains (Fig. 1B). The most intense hybridization signals were found in the strains showing an AluI restriction profile identical to B. cereus 2896 from which the probe was prepared. As expected, the restriction patterns of the SG-749 fragment from B cereus 336 were in agreement with its nucleotide sequence. Restriction analysis of the amplified SG-749 fragment confirmed the variability of the species B. cereus and B. thuringiensis. The isolates of these two species were distributed among different molecular groups, even though most of the strains were included in two main groups related to B. cereus 31T and 6127, respectively. B. mycoides strains were also heterogeneous, since several restriction profiles were observed. Four of the seven strains analyzed, including the type strain, fell into a separate group with respect to the other species. Restriction digestion generated two DNA fragments of about 90 and 660 bp in all the strains of B. anthracis, confirming the clonal nature of this species (Fig. 3B). This restriction profile was peculiar to B. anthracis, differentiating the isolates of this species from all the other strains of the B. cereus group and thereby suggesting the potential usefulness of this marker for the pathogen (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Characterization of the SG-749 fragment with the restriction enzyme AluI. (A) AluI restriction haplotypes of the SG-749 fragment found in the 61 strains of the B. cereus group listed in Table 1. Lanes M, 50-bp DNA size ladder; lane 1, SG-749 fragment; lanes A to K, AluI haplotypes (the capital letters refer to the haplotypes reported in Table 1). (B) AluI restriction pattern (haplotype K) of B. anthracis strains. Lanes M, 50-bp DNA size ladder; lanes 1 to 18, B. anthracis CEB 7700, 7702, 4229, 6602, Cepanzo, Davis TE702, 957, 227, 170, 300, 779, 832, 663, 376, 846, 256, 582, and 282; lane 19, SG-749 fragment.

The availability of chromosomal markers for B. anthracis has been only recently demonstrated. Patra et al. (23) identified a 277-bp fragment (BA813) in avirulent B. anthracis 7700 that was absent from all the other Bacillus species examined. It has been proposed (23, 27) that this fragment is useful for B. anthracis identification, prescinding from the molecular markers placed on the pXO plasmids previously used to identify and detect this organism (29). The plasmids can be lost by the cell, thereby leading to a misidentification of the isolate (23). Considering that in B. anthracis the SG-850 DNA fragment is placed on the chromosome, amplification of SG-749 followed by restriction analysis with AluI can be a useful tool to discriminate virulent and avirulent B. anthracis strains from the other closely related species of the B. cereus group.

In a very recent paper Patra et al. (24) found that some soil isolates lacking the pXO plasmids and resembling B. cereus were positive for the presence of the chromosomal marker BA813 considered specific for B. anthracis. The availability of other chromosomal markers specific for this pathogenic bacterium, such as the SG-749 fragment, may be useful for the identification of uncertain strains.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of RAPD marker SG-850 was submitted to the EMBL database under accession no. AF036105.

Acknowledgments

Particular thanks are given to Michele Mock and Guy Patra, who kindly gave us the total DNA of virulent and avirulent strains of B. anthracis. We are also indebted to Mario Luini and Silvia Grassi, who allowed us to cultivate two B. anthracis strains for DNA extraction at the Istituto Zooprofilattico of Milan. We thank Michele Mock, Guy Patra, and Diego Mora for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen G L, Simchock J M, Wilson K H. Identification of a region of genetic variability among Bacillus anthracis strains and related species. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:377–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.377-384.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus T A. A bacterial toxin paralysing silkworm larvae. Nature. 1954;173:54–56. doi: 10.1038/173545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash C, Collins M D. Comparative analysis of 23S ribosomal RNA gene sequences of Bacillus anthracis and emetic Bacillus cereus determined by PCR-direct sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;94:75–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90586-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash C, Farrow J A E, Dorsch M, Stackebrandt E, Collins M D. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:343–346. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash C, Farrow J A E, Wallbanks S, Collins M D. Phylogenetic heterogeneity of the genus Bacillus revealed by comparative analysis of small-subunit-ribosomal RNA sequences. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1991;13:202–206. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazzicalupo M, Fani R. The use of RAPD for generating specific DNA probes for microorganisms. In: Clapp J P, editor. Methods in molecular biology. 50. S-species diagnostic protocols: PCR and other nucleic acids methods. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press Inc.; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehringer Mannheim GmbH. The DIG system user’s guide for filter hybridization. Mannheim, Germany: Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Biochemica; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borin S, Daffonchio D, Sorlini C. Single strand conformation polymorphism analysis of PCR-tDNA fingerprinting to address the identification of Bacillus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourque S N, Valéro J R, Lavoie M C, Levesque R C. Comparative analysis of the 16S to 23S ribosomal intergenic spacer sequences of Bacillus thuringiensis strains and subspecies and of closely related species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1623–1626. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1623-1626.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claus D, Berkeley R C W. Genus Bacillus Cohn 1872, 174AL. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1105–1139. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daffonchio D, Borin S, Consolandi A, Mora D, Manachini P, Sorlini C. 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacers as molecular markers for the species of the 16S rRNA group I of the genus Bacillus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daffonchio D, Borin S, Frova G, Manachini P L, Sorlini C. PCR fingerprinting of whole genomes: the spacers between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes and of intergenic tRNA gene regions reveal a different intraspecific genomic variability of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus licheniformis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:107–116. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day W A, Jr, Pepper I L, Joens L A. Use of an arbitrarily primed PCR product in the development of a Campylobacter jejuni-specific PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1019–1023. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1019-1023.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Lamballerie X, Zandotti C, Vignoli C, Bollet C, De Micco P. A one-step microbial DNA extraction method using “Chelex 100” suitable for gene amplification. Res Microbiol. 1992;142:793–796. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drobniewski F A. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:324–338. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fancelli S, Castaldini M, Ceccherini M T, Di Serio C, Fani R, Gallori E, Marangolo M, Miclaus N, Bazzicalupo M. Use of RAPD markers for the detection of Azospirillum strains in soil microcosms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fani R, Damiani G, Di Serio C, Gallori E, Grifoni A, Bazzicalupo M. Use of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) for generating specific DNA probes for microorganisms. Mol Ecol. 1993;2:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrell L J, Andersen G L, Wilson K H. Genetic variability of Bacillus anthracis and related species. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1847–1850. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1847-1850.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson P J, Walters E A, Kalif A S, Richmond K L, Adair D M, Hill K K, Kuske C R, Andersen G L, Wilson K H, Hugh-Jones M E, Keim P. Characterization of the variable-number tandem repeats in vrrA from different Bacillus anthracis isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1400–1405. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1400-1405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson S G, Goodbrand R B, Ahmed R, Kasatiya S. Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolated in a gastroenteritis outbreak investigation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura L K. DNA relatedness among Bacillus thuringiensis serovars. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:125–129. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura L K, Jackson M A. Clarification of the taxonomy of Bacillus mycoides. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patra G, Sylvestre P, Ramisse V, Thérasse J, Guesdon J-L. Isolation of a specific chromosomic DNA sequence of Bacillus anthracis and its possible use in diagnosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;15:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patra G, Vaissaire J, Weber-Levy M, Le Doujet C, Mock M. Molecular characterization of Bacillus strains involved in outbreaks of anthrax in France in 1997. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3412–3414. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3412-3414.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen D J, Shishido M, Brian Holl F, Chanway C P. Use of species- and strain-specific PCR primers for identification of conifer root-associated Bacillus spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;133:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Praderio G, Schiraldi A, Sorlini C, Stassi A, Zanardini E. Microbiological and calorimetric investigations on degraded marbles from the Cà d’Oro façade (Venice) Thermochim Acta. 1993;227:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramisse V, Patra G, Garrigue H, Guesdon J-L, Mock M. Identification and characterization of Bacillus anthracis by multiplex PCR analysis of sequences on plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 and chromosomal DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reich C, Gardiner K J, Olsen G J, Pace B, Marsh T L, Pace N R. The RNA component of the Bacillus subtilis RNase P. Sequence, activity, and partial secondary structure. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7888–7893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reif T C, Johns M, Pillai S D, Carl M. Identification of capsule-forming Bacillus anthracis spores with the PCR and novel dual-probe hybridization format. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1622–1625. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1622-1625.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schraft H, Griffiths M W. Specific oligonucleotide primers for detection of lecithinase-positive Bacillus spp. by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:98–102. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.98-102.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sneath P H A, editor. Approved list of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turnbull P C B, Hutson R A, Ward M J, Jones M N, Quinn C P, Finnie N J, Duggleby C J, Kramer J M, Melling J. Bacillus anthracis but not always anthrax. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb04876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:166–176. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams J G K, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]