Sound decision-making is important for success and well-being in all stages of life but is critical in old age, when many complex and influential decisions are made and opportunities to correct mistakes are limited. Decisions related to financial and health matters are of utmost importance for older adults and have far-reaching implications. Older adults control most household wealth in the United States and face a host of difficult financial decisions related to Social Security distributions, asset decumulation, intergenerational transfers of wealth, and more. Older adults also suffer a disproportionate burden of disease and face complex medical decisions related to chronic disease management and end-of-life care. Adding to the complexity of late-life decision-making, many choices older adults face involve novel considerations and inherent uncertainty; for example, effective management of limited retirement funds requires an estimation of one’s own life expectancy.

Despite a lifetime of experience with decision-making, accumulating evidence suggests that many older adults struggle with financial and health decision-making. Older adults often take Social Security distributions too early (resulting in a significant long-term financial disadvantage), engage in unsound investments and risky credit/spending behaviors, and fail to take advantage of financial and health-care benefits. Perhaps even more alarming, older adults are highly vulnerable to financial exploitation and lose more than $30 billion annually in the United States alone. Further, recent Federal Trade Commission survey data suggest a disturbing increase in losses, with adults >60 years losing more than younger adults and considerably higher dollar amounts than their peers in prior years. Losses nearly doubled from 2019 to 2020 among individuals >80, the fastest-growing segment of the population. Further compounding the economic challenge is a looming public health crisis. Financial exploitation is associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including depression, hospitalization, and early mortality. Indeed, the National Council on Aging dubbed scams against the elderly the “crime of the 21st century” and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other federal agencies have called for immediate and intense efforts to address financial exploitation among older adults.

Degraded Rationality: A Novel Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Impact of Aging on Decision-Making and Financial Exploitation

Decision-making is a complex behavior that involves evaluating alternative options, weighing risks and benefits, forecasting future outcomes, and ultimately making a choice. Virtually all behaviors, from the ordinary (e.g., should I have a burger and fries or salad for lunch? Should I answer the phone when a stranger calls?) to the complex (e.g., which investment should I choose? Should I sign up for the Medicare part D plan?), involve some degree of decision-making. It has long been appreciated that cognitive resources and deliberative thinking are required for good decision-making, especially when many options are available. Early economic models of decision-making relied on assumptions of perfect rationality and posited that individuals generate and process all available alternatives and align them with their preferences to make decisions that yield maximum personal utility. However, more recent models from behavioral economics and psychology recognize the limits of human rationality (and the frequency of suboptimal decision-making) and conceptualize the decision-making process as one of bounded rationality. According to the theory of bounded rationality, humans rely on incomplete information and process it within their cognitive limitations and time constraints. Bounded rationality helps explain systematic errors in decision-making and applies to individuals of all ages.

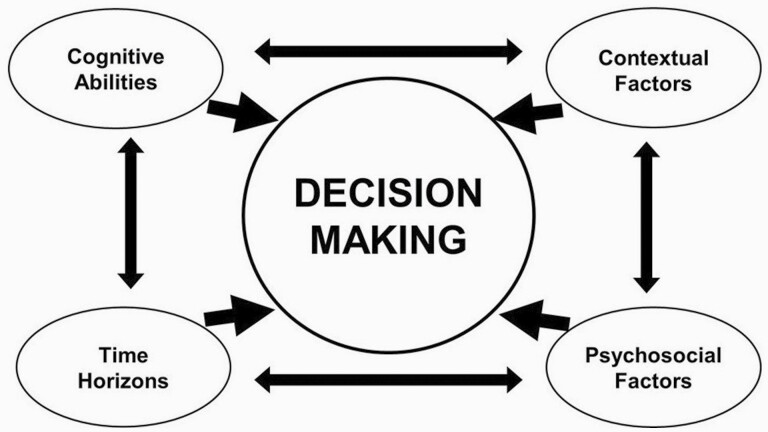

We posit that aging poses unique challenges that are not fully addressed by bounded rationality and can lead to a state of degraded rationality, in which decision-making is further compromised as a result of aging-related changes in the resources needed for good decision-making. In our conceptual framework, late-life decision-making requires a complex interplay among diverse abilities and resources, including cognitive abilities and time constraints but also contextual (e.g., financial and health literacy, financial resources) and psychosocial (e.g., personality, affective, and psychological/social) factors (Figure 1). These resources can have wide individual differences, and they are also uniquely impacted by aging. That is, while old age is recognized as a time of diminishing cognitive abilities and time horizons, it is also a time of changing contextual and psychosocial resources. In our view, aging-related changes and deteriorating brain health can impair and/or disrupt the dynamic interplay among skills needed for good decision-making, resulting in degraded rationality. Degraded rationality renders older adults—including those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) (i.e., ADRD, characterized by significant cognitive impairment), as well as many who are cognitively healthy (i.e., without overt cognitive impairment)—vulnerable to decision-making errors and exploitation by bad actors.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing the dynamic interplay among diverse resources that support financial and health decision-making among older adults.

Our theory of degraded rationality is supported by compelling findings accrued over the past decade from our study of decision-making among >1,500 participants of the Rush Memory and Aging Project, a longitudinal, clinical–pathologic epidemiologic study of aging. This study involves detailed annual assessments of financial and health decision-making and related abilities, including financial and health literacy, scam susceptibility, fraud risk, decision styles, and risk preferences. Many of the measures are performance-based and have objectively correct or incorrect answers that can be scored to indicate more accurate (better) or less accurate (poorer) decision-making. Participants also undergo detailed clinical evaluations each year to document adverse health outcomes, including dementia, and a brain autopsy is performed after death for quantification of common age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), in the brain. Our data suggest that many older adults demonstrate poor decision-making: that is, a vulnerability to decisional errors or exploitation by bad actors. These data also suggest that degraded rationality is common both among individuals with dementia as well as among many cognitively healthy older adults. Thus, the economic and public health challenges related to degraded rationality may be much greater than currently appreciated. Efforts to promote sound decision-making and prevent financial exploitation among older adults warrant prioritization and immediate focus. Below, we present key research findings and policy considerations.

What Have We Learned About Aging and Decision-Making? Five Takeaways

-

1.

Poor financial and health decision-making is common not only among older adults with dementia but even among cognitively intact older adults. It is often assumed that poor decision-making among older adults is largely due to dementia, and decision-making is indeed impaired in individuals with ADRD. However, compelling evidence suggests that poor decision-making is not at all limited to individuals with severe cognitive deficits. We and others have shown that mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a syndrome characterized by only mild deficits in memory or other aspects of cognition, is associated with poorer financial and health decision-making and lower financial and health literacy. MCI also is associated with an increased susceptibility to scams and fraud.

Critically, however, even among cognitively intact persons—those without dementia or even MCI—30% to 40% of older adults exhibit suboptimal decision-making and financial and health literacy. Further, even very subtle age-related changes in cognition (those typically attributed to normal aging) contribute to poor decision-making, decreased literacy, and greater susceptibility to scams and fraud. Similarly, many cognitively intact older adults report engaging in behaviors associated with financial exploitation. For example, in our study, >75% of cognitively intact participants report that they answer the phone whenever it rings even if they do not know who is calling, about 25% listen to solicitations by telemarketers, and more than 10% have difficulty ending an unwanted communication with a telemarketer (Boyle et al., 2019). Further, about 8% of our cognitively intact participants report being a victim of fraud each year. This percentage is consistent with population estimates of fraud prevalence rates that indicate that 5% to 10% of cognitively intact individuals are victimized annually (Burnes et al., 2017). Notably, these prevalence rates are underestimates considering that many older adults do not report victimization and/or do not know they were victimized. Together, these data provide strong evidence that a considerable proportion of older adults—including many without overt cognitive impairment—are at risk of suboptimal decision-making and financial exploitation. The challenges associated with poor decision-making and exploitation will only increase as the number of older adults, particularly those >80, rises dramatically in the coming decades.

-

2.

Late-life decision-making reflects a dynamic interplay among diverse skills and resources, and noncognitive resources play important roles. We have identified numerous factors that impact decision-making, including contextual factors, such as financial and health literacy and financial resources, and psychosocial factors, such as loneliness and well-being, to name just a few (Stewart et al., 2018). Moreover, the nature of the associations of these factors with decision-making can differ in important and interesting ways. Whereas some impact decision-making relatively independent of cognition, others interact with cognition to impact decision-making. For example, we reported that contextual factors (e.g., financial and health literacy, financial fragility) and personality attributes (e.g., risk aversion) are related to decision-making relatively independently of cognition. By contrast, psychological factors (e.g., loneliness, well-being) interact with cognition to affect decision-making. Overall, our work suggests that negative factors (e.g., loneliness) tend to exert deleterious effects on decision-making, particularly among older adults with relatively lower cognition (though still within the nonimpaired range), whereas positive factors such as well-being enhance decision-making, particularly among those with relatively lower cognition.

We suspect that noncognitive factors are critical for decision-making when cognitive resources are low because they help compensate in the face of cognitive limitations. However, we acknowledge that the skills needed for good decision-making can vary depending on the task at hand. Noncognitive resources may be less important for certain (e.g., highly analytic) decisions but highly relevant for emotionally charged decisions. For example, resisting fraudsters requires social cognitive processes, including the ability to recognize that others may have untoward intentions and the ability to resist social pressure. This can be challenging, especially for older adults who are lonely or depressed. Indeed, studies sponsored by the National Institute of Justice suggest that social isolation and depression are drivers of victimization among independently living and cognitively intact individuals. Thus, aging-related processes can differentially impair the resources needed for good decision-making (Figure 1), thereby rendering older adults—including those with ADRD, as well as those without cognitive impairment—vulnerable in different settings for different reasons.

-

3.

Poor decision-making in old age is a very early harbinger of adverse health outcomes. An important goal of our research is to understand the health and financial consequences of poor decision-making among older adults. Toward this end, we examined the association of decision-making with several important outcomes, including mortality, Alzheimer’s dementia, and MCI. Findings consistently showed that decision-making is an early and robust indicator of adverse outcomes. For example, poor financial and health decision-making is associated with a substantially increased risk of mortality; those who exhibited poor decision-making were about 4 times more likely to die over about 4 years compared to those who exhibited good decision-making. Similarly, poor decision-making is associated with a substantially increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI; those making poor decisions were more than twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI compared to those making good decisions. Further, increased scam susceptibility is associated with a doubling in the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI (Boyle et al., 2019). Importantly, decision-making is related to these outcomes after controlling for cognition, suggesting that it is an early and relatively independent risk factor for a variety of adverse health outcomes and a preclinical manifestation of impending ADRD in some older adults.

-

4.

Poor decision-making among older adults is also an early indicator of deteriorating brain health. There is now widespread awareness among the aging and ADRD research community that the pathology of AD is nearly ubiquitous in the brains of older adults and degrades functional abilities prior to the onset of dementia, including among some individuals who will never develop overt dementia. We hypothesized that poor decision-making may be one of the earliest behavioral manifestations of AD pathology in the aging brain, in part because decision-making requires coordination of diverse abilities supported by distributed neural networks. In fact, among nondemented older adults who underwent brain autopsy, we found that AD pathology, particularly its earliest manifestation (i.e., beta-amyloid), was associated with poorer financial and health decision-making, lower financial and health literacy, and increased scam susceptibility (Boyle et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2018). These findings strongly suggest that poor decision-making is a very early behavioral manifestation of accumulating AD pathology in the aging brain.

-

5.

Poor decision-making among older adults is not simply due to longstanding deficits; rather, decision-making declines over time with advancing age. Few studies have the repeated decision-making assessments needed to examine aging-related change in decision-making over time, as in our study. Our emerging data consistently show that the quality of financial and health decision-making tends to decline over time with advancing age. Notably, as with other abilities (e.g., cognition), there is considerable variability in rates of decision-making decline, with some individuals declining rapidly, others at a moderate rate, and still others remaining stable over time (Yu et al., 2018). Thus, aging-related changes in decision-making are common but not inevitable. An important goal of our work is to identify risk factors for decision-making declines, as these can help identify older adults vulnerable to poor decision-making. Our initial analyses suggest that negative psychological factors, such as depressive symptoms, predict faster declines over time, and positive psychosocial factors, such as purpose in life, are protective against decline. These results suggest that poor decision-making among older adults reflects an aging-related decline (rather than simply a low starting level) and that we can identify risk factors for decline, some of which are modifiable. Continued collection and analysis of longitudinal data will allow us to further characterize age-related declines in decision-making and identify additional risks and protective factors. This work will facilitate interventions to support late-life decision-making, which are critically needed.

From Degraded Rationality to Reality: Policy Implications and the Path Forward

Mounting research over the past decade has transformed our understanding of the impacts of aging on decision-making. Our research provides strong and consistent evidence that aging-related changes in behavioral and brain functioning degrade financial and health decision-making among older adults. This work supports our theory of degraded rationality and shows that poor decision-making is common among even cognitively intact older adults (in addition to those with diagnosable cognitive syndromes). This means that a considerable proportion of all older adults are vulnerable to poor decision-making and financial exploitation, which pose major threats to both individuals (e.g., financial loss, depression, hospitalization, and early mortality) and society as a whole (e.g., increased costs as a result of after-the-fact financial and medical interventions). These threats will only increase as the population ages in the coming decades.

Addressing the challenges associated with aging and decision-making will require a collaborative approach that engages diverse stakeholders. Real-world considerations and challenges should inform research and guide priorities, and science should inform and facilitate objective, evidence-based policy changes. Improving the integration between research and policy requires open communication, collaboration, funding, and an infrastructure that unites researchers, government agencies, regulatory bodies, policy-makers, and financial and health-care providers. The National Institute of Justice, National Adult Protective Services Association, American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Foundation, and others are working to facilitate collaboration between researchers and policy-makers via conferences and training programs, but a robust infrastructure for these activities is lacking. Academic, government, and policy partnerships are essential to address the economic and public health challenges posed by poor decision-making and financial exploitation among older adults.

Below are some suggestions regarding how our understanding of aging and decision-making can inform and improve policies to facilitate good decision-making and support older adults.

Reconsider how financial and health policies are structured to address degraded rationality, and change them where appropriate. While this is a broad suggestion, we already have examples in the financial-services industry. For example, FINRA and more than 30 states have enacted laws or rules that encourage broker-dealers or investment advisers to temporarily pause suspicious transactions or disbursements so that investigators can investigate and, if needed, take action before a customer is harmed. Similarly, California has enacted a research-backed law that reformed the disclosures accompanying certain mortgage products. Similar protections could be applied within the health-care domain.

Improve structural interventions for financial and health-care providers. Beyond interventions targeted toward individuals, broader structural interventions may help. A structural intervention is an intervention by a financial or health services provider, such as when a bank employee notifies a customer that the transfer they would like to make may be to a scammer. For example, the “Senior Safe Act,” enacted in 2018, is an important law designed to assist in the protection of older Americans’ financial resources. Specifically, the law ensures that financial institutions and their eligible employees can report suspected financial exploitation without the concern of liability for that action. In furtherance of the intent of this law, together with the North American Securities Administrators Association and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) staff, FINRA provides a resource that securities firms can use to train investment advisors and other providers how to detect, prevent, and report financial exploitation of vulnerable investors. Similarly, the National Center on Elder Abuse offers virtual resources to train health-care professionals and advocates to identify signs of exploitation and strategies to inform potential victims. Such programs would benefit from expansion to include a broader network of financial and health professionals that work directly with older adults, as they are often the first responders to financial exploitation.

Leverage research findings to identify the most vulnerable older adults and develop evidence-based interventions to facilitate better decision-making. The available research provides important clues as to how to identify those older adults at greatest risk of poor decision-making and financial exploitation. Specifically, older adults who are isolated, depressed, have low literacy or cognition, and have limited financial resources may be at high risk and represent a target population for interventions to improve decision-making. Interventions designed to improve mood and literacy likely will be more beneficial than those aimed at improving cognition, and such interventions should be prioritized. Behavioral interventions already have demonstrated efficacy for improving mood among older adults, although they have not been studied in the context of decision-making. Further, studies have shown that literacy can be improved via educational programs. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of such interventions for decision-making specifically (and possibly related health impacts, such as delaying the onset of dementia). Development of novel interventions is also encouraged.

Expand educational resources. Research findings, including those from the FINRA Foundation, suggest that older adults can benefit from educational programs targeting literacy and financial exploitation. For example, the FINRA Foundation’s work has shown that educational interventions delivered via video or text can efficiently improve financial literacy and reduce susceptibility to fraud. National organizations also have promoted online offerings to promote public awareness of common scams and the tactics of fraudsters. Many other resources also are available, though not necessarily publicized (e.g., tools such as spam-blocking telephones). With appropriate promotion and dissemination of accurate information, online resources could be very useful for older adults who may not be able to access resources and services outside the home.

Promote advance planning and tools for monitoring unusual behaviors. Planning ahead for common challenges may be an important protective strategy. For example, in 2018, amendments to FINRA Rule 4512 went into effect that require investment firms to make reasonable efforts to identify a “trusted contact” for individual customer accounts. The trusted contact is intended to be a resource for the advisor administering the financial account, with the goals of helping to protect assets and responding to possible financial exploitation. FINRA also implemented new rules in 2018 to provide firms with tools to help prevent suspected financial exploitation. In addition, financial institutions and investment firms are increasingly offering tools to identify unusual withdrawal patterns and other signs of erroneous decision-making and potential victimization. If administered judiciously, this type of monitoring may identify behavioral irregularities before a major financial loss or exploitation occurs. Similar approaches could be used to improve decision-making in health-care settings. For example, monitoring irregularities in health behaviors (e.g., missing appointments) may help identify individuals struggling with decision-making and at risk of adverse health outcomes.

The above considerations are recommended as a starting point for discussion, recognizing that we will need to continue to adapt policy efforts to best support and protect older adults as our understanding of the relationship between aging and financial and health decision-making advances. To be clear, we are not suggesting that aging-related vulnerabilities render older adults incapable of making good decisions; rather, we suggest that aging-related changes can contribute to decision-making challenges and that federal, state, local, and private policies can better address these challenges. Policy-makers across the country have already begun implementing such changes; these include the FINRA rules and state laws regarding placing a pause on certain suspicious activities in the securities industry, removing legal barriers to communication between key parties, and the federal enactment of the Senior Safe Act. Agencies are also exploring avenues to assist victims of financial abuse recoup lost money. For example, in 2020 the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau awarded a contract to researchers for a study of financial loss and recovery for older victims of financial exploitation.

We hope to further a national conversation focused on what it means to confront aging-associated vulnerabilities and why it is important to recognize this challenge from a policy-making perspective. The time is ripe to build on the policy work that has already been started and to further strengthen the connection between research and policy, ensuring that policy efforts maximize older adults’ dignity and independence.

Acknowledgments

Further information about the study and data requests is available at Resource Sharing Hub at http://www.radc.rush.edu.

Funding

Funding for this study came from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG33678 to Boyle, R01AG34374 to Boyle, R01AG60376 to Boyle, R01AG17917 to Bennett) and the Illinois Department of Public Health. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

References

- Boyle, P. A., Yu, L., Schneider, J. A., Wilson, R. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2019). Scam awareness related to incident Alzheimer dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A prospective cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170, 702–709. doi: 10.7326/M18-2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D., Henderson, C. R., Sheppard, C., Zhao, R., Pillemer, K., & Lachs, M. S. (2017). Prevalence of financial fraud and scams among older adults in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 107, e13–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C. C., Yu, L., Wilson, R. S., Bennett, D. A., & Boyle, P. A. (2018). Correlates of healthcare and financial decision making among older adults without dementia. Health Psychology, 37, 618–626. doi: 10.1037/hea0000610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L., Wilson, R. S., Han, S. D., Leurgans, S., Bennett, D. A., & Boyle, P. A. (2018). Decline in literacy and incident AD dementia among community-dwelling older persons. Journal of Aging and Health, 30, 1389–1405. doi: 10.1177/0898264317716361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]