More than 6 million adults in the United States are affected by Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), the majority of whom rely on assistance from an unpaid care partner (family, friends; Alzheimer’s Association, 2022). ADRD care partners assist with disease management tasks (Riffin et al., 2017) and perform critical functions within the health-care system, such as attending routine medical visits (Wolff & Roter, 2011), facilitating hospital discharge processes (Levine et al., 2010), and coordinating long-term services and supports (Kelly et al., 2013). Yet, care partners report feeling marginalized in medical encounters due to unmet needs for training and support (Burgdorf et al., 2019). If left unattended, these unmet needs can contribute to burnout for the care partner (Jennings et al., 2015), diminished quality of care for the patient (Black et al., 2019), and substantial economic burdens for the health-care system in the form of increased rates of hospitalization and institutionalization among older adults (Amjad et al., 2021). Thus, systematically engaging and supporting care partners in health-care and long-term care settings is critical to delivering high-quality care to persons with ADRD.

Increasing federal investments and innovations in health-care policy, delivery, and payment have raised the prospect of explicit inclusion and support of ADRD care partners in health-care delivery (Department of Health and Human Services, 2013; Reyes et al., 2020). Yet, the extent to which these initiatives are leading to improvements in ADRD care-partner identification, assessment, and support is unclear, in large part because there are limited empirical data regarding their effectiveness and no clear research agenda to guide future evaluations and scaling.

The goal of the 2021 Conference on Engaging Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers of Persons With Dementia in Healthcare Delivery, funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), was to establish a policy- and practice-aligned research agenda for enhancing ADRD care-partner engagement and support in health-care settings. It builds on prior research summits and policy initiatives (summarized in Mitchell & Gaugler, 2021) by focusing exclusively on ADRD care-partner identification, engagement, and support in clinical encounters and by leveraging an evidence-based, participatory method for establishing actionable priorities. This article presents the key priorities generated from these consensus conference activities.

Overview of the Conference

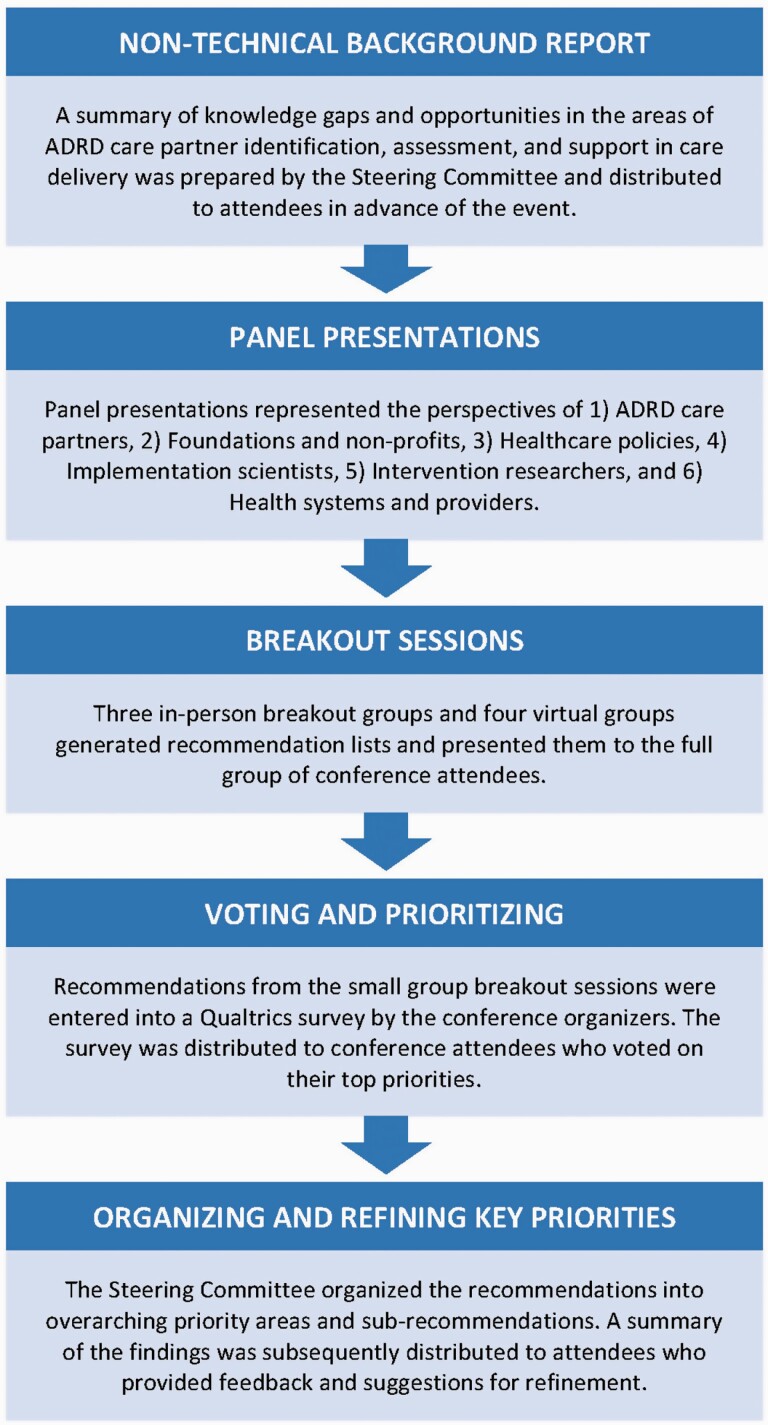

The conference activities were organized according to the Cornell Institute for Translational Research on Aging Research-to-Practice Consensus Workshop Model (Figure 1), an evidence-based method for bridging gaps in research, policy, and practice by bringing multidisciplinary stakeholders into the agenda-setting process (Pillemer et al., 2015). A 10-person Steering Committee representing five stakeholder groups: care partners of persons with ADRD, health-care providers, researchers, payers, and non-profit organizations guided the event. Conference attendees were a select group of thought leaders from diverse sectors, including caregiver advocates, health-care providers, researchers, individuals in policy roles, and representatives from funding agencies and caregiving organizations. In total, 65 individuals from across the nation attended the hybrid event, held on October 1, 2021: 23 convened at the Weill Cornell Medical College campus in New York City and 42 attended virtually (via Zoom). The event opened with a series of six expert panels representing the perspectives of (1) ADRD care partners; (2) foundations and non-profits; (3) policy advocates; (4) intervention researchers; (5) implementation scientists; and (6) health systems and providers. These panels set the stage for consensus activities. Attendees were charged with generating recommendations and voting on their top priorities. A summary of the conference objectives can be found at: https://geriatrics-palliative.weill.cornell.edu/dementiacaregiving2021, and the process for identifying recommendations is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conference activities. ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Key Priority Areas

Conference recommendations centered on five key topics: (1) identification and assessment of care partners; (2) reimbursement and financing for provider time spent on care-partner identification, assessment, and support; (3) care-partner training and support; (4) health-care provider education; and (5) technology (Table 1). To support future work in each of the five priority areas, conference participants highlighted the importance of leveraging lessons from implementation science and models of equity and inclusion (Table 2). In the sections that follow, we summarize the overarching priorities and sub-recommendations identified by the conference participants, highlighting key organizations and efforts that can help to catalyze action and enact strategies that meaningfully integrate care partners into the health-care delivery system.

Table 1.

Key Recommendations Identified by the 2021 Conference on ADRD Caregiving

| Topic | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Identification and assessment | Develop standardized tools that can be integrated within health information technologies and promote accurate identification of care partners in medical settings. Conduct stakeholder-engaged research to design identification and assessment protocols that are responsive to the heterogeneity in patients’ and care partners’ circumstances and preferences. Evaluate whether and how identifying and supporting care partners earlier in their care recipient’s disease trajectory may impact care quality and outcomes. Collaborate with health-care systems and payment plans (Medicare and Medicaid) to embed and reimburse for care-partner identification and assessment procedures in routine care delivery. |

| Reimbursement and financing | Determine the prevalence of and barriers to the use of payment mechanisms that enable providers to bill for services provided to an ADRD care partner who is not their patient. Identify what incentives may promote health-care systems’ uptake and use of care partner–focused reimbursement codes. Evaluate the longitudinal benefits of ADRD care-partner interventions on macro-level outcomes, including effects on labor supply, work productivity, and tax revenues. Design studies that measure potential unintended consequences of new and existing policies and payment reforms on ADRD caregivers and use the findings to promote policy changes. |

| Care-partner training and support | Identify and subsequently implement and disseminate best practices for facilitating ADRD care-partner referrals from medical settings to community-based services and to ongoing clinical trials; compare these practices across health-care settings and systems of care. Develop unified models of care delivery that support ADRD care partners across the care continuum and especially during critical care transitions (e.g., into long-term care settings). Design interventions that extend across each stage in the disease trajectory and are responsive to the changes in care partners’ needs over time. Develop and test training programs that attend to issues beyond the tasks care partners provide, including help with health literacy and numeracy, financial planning, and end-of-life planning. |

| Provider education | Design and implement evidence-based curricula that prepare medical professionals to deliver person- and family-centered care. Develop training programs to help health-care providers navigate “shared care” encounters in which a person with ADRD has a network of multiple care partners. Test impacts of provider communication skills training on patient and care-partner outcomes, including care quality and satisfaction. |

| Technology | Determine how the electronic health record and other interoperable devices may assist with identifying ADRD care partner(s) and assessing their respective contributions and needs. Leverage technology to facilitate the remote delivery of evidence-based interventions. Build on existing digital infrastructures (patient portals, electronic care plans, apps) to support ADRD care partners and share information across providers and care settings. Identify and evaluate technology applications that can provide support for the caregiving role (e.g., monitoring, assisting with ADL/IADLs) and determine how to best integrate these applications with care plans. Target technology to demographic subgroups for examining and increasing the benefits to underserved communities. |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living; ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Table 2.

Core Elements for Advancing and Sustaining Progress on ADRD Care-Partner Engagement and Support in Care Delivery Settings

| Core element | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Implementation science | Develop a systematic, unified strategy—guided by the existing evidence—for advancing the science of implementation and dissemination research on ADRD caregiving. Establish best practices for expanding the scale and reach of evidence-based interventions for ADRD care partners that take into account unique contextual considerations. Develop and test promising strategies for monitoring intervention fidelity and promoting sustainability after implementation in community and clinical settings. Conduct a portfolio analysis of funding mechanisms, focused on implementation, dissemination, and sustainability, to stimulate greater emphasis on this type of funding and raise awareness among researchers regarding potential opportunities in this area. Foster implementation of evidence-based interventions and develop and test caregiver programs that are ancillary to direct care services but integrate patient systems of care. |

| Models of inclusion and equity | Conduct inclusive research on ADRD caregiving by using community-driven approaches to engage stakeholders from diverse minority groups in every aspect of future work, from inception to dissemination. Leverage intersectionality frameworks to consider how multiple factors may affect ADRD care partners and their interactions with health-care systems. Achieve consensus on best practices for adapting and tailoring existing evidence-based interventions to diverse populations, including ADRD caregivers of underserved or overlooked groups (e.g., rural caregivers or caregivers of veterans). |

Note: ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Identification and Assessment

The need for standardized methods to facilitate accurate identification of ADRD care partners is a major priority. Identification should occur in care-partner interactions with health-care systems and care-partner attendance at care recipients’ medical appointments. Identification should be aligned with structured methods for effective, sensitive, and timely need and risk assessments. This recommendation recognizes the heterogeneity of care partners’ contexts, preferences, and stages in the care pathway. Active engagement of ADRD care partners from diverse backgrounds in the process of developing and refining care-partner identification and assessment protocols was deemed essential for ensuring relevance to individuals’ circumstances and preferences (e.g., the family’s cultural values).

Learning health systems—systems committed to implementing evidence-based practices and improving efficiencies in health-care delivery through evaluation of local practices and use of internal data (Agency for Health Research and Quality, 2019)—were identified as optimal settings to test care-partner identification and assessment protocols. The input of key stakeholders within these systems was identified as essential in facilitating adaptation and refinement of existing processes and practices.

Future work in these areas would benefit from leveraging evidence-based resources, such as evidence reviews by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Family Caregiver Alliances’ searchable repository of dementia programs, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care’s guidance on best clinical practices, and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ measures inventory, to guide health-care systems in developing procedures for identifying and supporting care partners. Lastly, existing assessment tools such as the Care Partner Profile checklist developed by the Alzheimer’s Association (2022) could be tailored based on stakeholder feedback.

Reimbursement and Financing

Growth in Medicare Advantage, recognition of the relevance of social factors to health care, and development of chronic care management codes were acknowledged as affording new opportunities to reimburse health-care providers for the time they spend on care-partner identification, assessment, and support (Griffin et al., 2022). Accordingly, a key recommendation was to embed pragmatic trials of care partner–focused reimbursement codes within health systems to identify barriers and facilitators to the uptake of such codes, including those that enable billing for services provided directly to an ADRD care partner. It will be critical to evaluate benefits and unintended consequences of payment reform on persons with ADRD and their care partners and to use the findings to promote policy change.

Collaborations between health systems and payers (both private and government) were identified as a key mechanism for supporting future integration and reimbursement for ADRD care-partner assessment and support in routine care delivery. Recent passage of the federal Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act raised the possibility of Medicare Advantage plan coverage of supportive services for ADRD care partners, such as counseling, training, and respite care (Willink & DuGoff, 2018), but requires payer–researcher partnerships to establish an evidence base on cost savings, quality improvement, and member satisfaction (Thomas et al., 2019). Standard billing codes that capture social determinants of health (i.e., socioeconomic factors ranging from food security to education) represent an opportunity to assess ADRD care partners’ needs and risks. For example, the American Medical Association, in partnership with UnitedHealthcare, has begun to use International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition codes to track social service needs among Medicare beneficiaries (Bresnick, 2019) and could readily incorporate ADRD care-partner assessments into future reimbursement policies.

Care-Partner Training and Support Across the Care Continuum

There was broad consensus regarding the need for clinical care pathways that would enable linkages between care-partner assessment outcomes and relevant community-based programs and ongoing clinical trials. To date, the Veterans Administration has served as a model for enacting such linkages through the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers, allowing eligible veterans to identify up to three of their care partners to receive additional services, such mental health counseling and respite care (Bruening et al., 2019). Outside of the Veterans Administration system, Area Agencies on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association Chapters are positioned to develop and implement structured referral-support protocols in collaboration with medical settings (e.g., hospitals, memory clinics) and deliver education, training, and access to resources to ADRD care partners. Promising new data suggest the feasibility and benefit of embedding evidence-based interventions within publicly funded Medicaid home and community-based service waiver programs (Fortinsky et al., 2020) and adult day services (Gitlin et al., 2019). Such innovations have the potential to support care partners across the care continuum and to pave the way for future research–practice–community partnerships in diverse settings.

Another key recommendation is the need for models that support ADRD care partners at each stage in the disease trajectory, especially at diagnosis and during care transitions. It is important to understand whether and how identifying and providing needed support to care partners earlier in their care recipient’s disease trajectory impacts subsequent care quality and health-related outcomes for both the individual with ADRD and the care partner. Equally critical will be designing supports for care partners who are transitioning care recipients into long-term care (e.g., assisted living or nursing home settings) and ensuring supports are maintained after the initial transition. These recommendations represent important opportunities for researchers, intervention developers, and community partners to identify and codevelop supportive programs that are responsive to changes in care partners’ needs over time and to collaborate with national organizations, such as the National Council on Aging, to ensure that these programs have broad reach.

Health-Care Provider Education

The provision of high-quality ADRD care requires the interdisciplinary expertise of physicians, nurses, social workers, home health aides, case managers, and community health workers. One key recommendation is the need for development and dissemination of evidence-based training and education programs that prepare the workforce to deliver culturally competent, person- and family-centered care. These programs should include modules that address empathic communication, as well as implicit and explicit biases about care partners’ abilities, cultures, backgrounds, and motivation to provide care. Of equal importance is the need for continuing education that supports the ability of health-care professionals to navigate “shared care” encounters in which a person with ADRD has multiple care partners.

The Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program Coordinating Center, led by the American Geriatrics Society and funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration, is well positioned to advance work in these areas by funding and partnering with researchers to test the impacts of training and education programs on patient and care-partner outcomes (e.g., satisfaction with care). Other professional organizations that are committed to promoting care-partner engagement, like the National Hartford Center of Gerontological Nursing Excellence, can promote discipline-specific education by designating care-partner engagement as a core competency and providing continuing education credits to individuals who participate in care partner–focused training. With support from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Journal of Nursing and the American Association for Retired Persons recently published a compendium of articles to help nurses support care partners who manage their care recipient’s health care at home (The John A. Hartford Foundation, 2021). These resources could be adapted for other professionals, such as home health aides or community health workers, and expanded to include training in cultural competence, implicit biases, and shared care encounters.

Technology

Health information technology is a strategy to facilitate ADRD care partners’ access to health information and participation in care. Within this area, a core recommendation is to advance and extend research–practice partnerships that evaluate how electronic health records (EHR) and other interoperable devices may be used in medical settings to help identify ADRD care partner(s) and deliver tailored support to address their needs. Commitment from EHR vendors, such as Epic and Cerner, is necessary to build on and adapt existing digital infrastructures to support the integration of care partner–focused data fields and resources within existing electronic workflows. One initiative, a pilot study of an embedded pragmatic clinical trial, is evaluating the potential of embedding an efficacious online psychoeducational program for ADRD care partners—Tele-Savvy—in outpatient clinics and determining the viability of routinely collecting and storing care-partner data in the clinics’ EHR systems (Clevenger et al., 2021; National Institute on Aging IMPACT Collaboratory, 2021). As work in this area progresses, the involvement of patients and care partners from diverse backgrounds, as well as administrative, technical, and clinical representatives from health systems, will be critical for ensuring that new systems are accessible, inclusive, and responsive to a broad array of cultures and backgrounds.

The 21st Century Cures Act mandated that health-care organizations provide patients with electronic access to their health records. Consequently, direct messaging through electronic patient portals is a mainstream mode of health-care communication. Direct messaging affords new opportunities to identify care partners who interact electronically with clinicians and provide them with relevant resources through the online portal; for example, links to disease-based education or information on respite care. Future work in this area should also evaluate differences in usage and outcomes for demographic subgroups of care partners (minority groups, long-distance caregivers, individuals from rural areas), given a persistent “digital divide” whereby individuals from lower socioeconomic statuses, minoritized backgrounds, and rural areas typically experience barriers in technology access and skills (Anderson & Perrin, 2017). There was also consensus regarding the need to develop and evaluate technologies that could be employed to assist with care provision and environmental safety through video tracking of the home environment, robotic support, and medication management support. Such advancements were viewed as necessary to complement existing technology-based interventions that deliver psychosocial support to ADRD care partners (e.g., Czaja et al., 2013).

Core Elements for Advancing and Sustaining Progress on ADRD Care-Partner Engagement and Support in Care Delivery

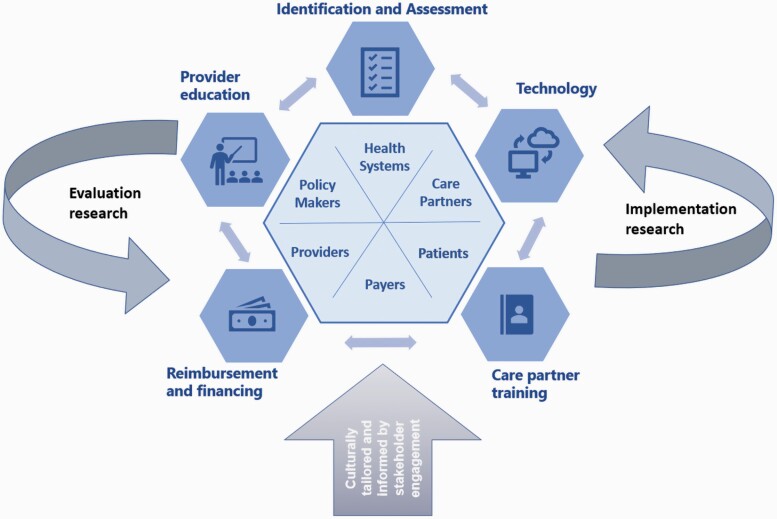

In addition to the five priority topics described above, the workgroup identified two elements fundamental to effectively sustaining a system of care delivery that engages and supports ADRD care partners: implementation science and inclusion and equity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework for advancing and sustaining future multidisciplinary collaboration on ADRD care-partner identification, assessment, and support in health-care delivery. ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Implementation Science

Implementation science—the study of methods to promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based programs—is essential for practice changes in health-care delivery. Future work will need to establish best practices for implementing care partner–specific tools and programs in care delivery settings and for expanding the scale and reach of evidence-based interventions. One particular concern was the need for systems to adapt evidence-based programs to their local contexts and monitor adherence to the program after the initial implementation period. As a leader in the development of methods designed to promote uptake of ADRD-focused interventions in health-care systems, the NIA IMbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and AD-Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) Clinial Trials (IMPACT) Collaboratory and its Implementation Core are developing foundational infrastructure to guide care delivery systems in embedding ADRD care-partner identification and assessment by providing expert consultation to investigators and training the next generation of ADRD researchers.

Inclusion and Equity

Systemic racial discrimination and exclusion of vulnerable populations is a persistent issue in research, policy, and practice related to ADRD caregiving (Harootyan & Rozario, 2021). There was strong consensus that future work to advance care-partner engagement and support in health-care delivery should use participatory, community-driven approaches to establish partnerships with diverse stakeholders (care providers, persons with ADRD, care partners) from traditionally marginalized and historically excluded groups, and that these partnerships should begin with the project’s inception and continue through to dissemination (Phillips & Wolfe, 2021).

There was also a resounding sentiment that for researchers to partner effectively with diverse stakeholders and support lasting policy and practice change, longer funding periods that allow time for establishing and nurturing partnerships are necessary. The NIA has taken important steps to enact progress on this front by investing in research on health disparities and inequities (National Institute on Aging, 2015). Additional action by federal agencies and private foundations should support community-driven work that represents diverse populations. To facilitate progress in this area, intersectionality frameworks will be necessary to understand how social factors, such as race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and the geographic setting, may affect ADRD care partners and their interactions with health systems.

Conclusion

Federal agencies, health-care systems, and funding bodies have strong incentives—encompassing financial, quality-of-care, and performance metrics—to support ADRD care partners in their care of persons with ADRD. There is clear evidence on the value of care partners’ unpaid contributions to their care recipients’ health outcomes. Supporting this high-need group is likely to yield important dividends for health systems, payers, and society at large.

The 2021 Conference on Engaging Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers of Persons With Dementia in Healthcare Delivery convened multidisciplinary thought leaders from across the United States to establish a set of actionable recommendations to advance the field. These recommendations are intended to inform federal agencies and foundations about high-priority areas and motivate multidisciplinary collaborations to design care delivery systems that effectively engage and support ADRD care partners. Measurable and sustained progress is contingent on the active participation of health-care systems, the involvement of technical and content experts (e.g., EHR developers, implementation scientists), support from funding agencies and foundations, and commitment from federal- and state-level organizations and policies (e.g., Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage Family Caregiver Act, National Alzheimer’s Project Act, Building Our Largest Dementia Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act). As the prevalence of ADRD is projected to rise over the coming decades, with no disease-modifying treatment available, investing in the policies, research, and infrastructure necessary to support ADRD care partners is imperative.

The 2021 Conference on Engaging Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers of Persons With Dementia in Healthcare Delivery convened multidisciplinary thought leaders from across the United States to establish a set of actionable recommendations to advance the field.

These recommendations are intended to inform federal agencies and foundations about high-priority areas and motivate multidisciplinary collaborations to design care delivery systems that effectively engage and support ADRD care partners.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Sullivan and Erica Sluys for their administrative and technical assistance; Veerawat Phongtankuel, Chanee Fabius, Julia Burgdorf, and Rachel Bloom for facilitating small-group consensus activities; Mario Hernandez for his assistance with photography; and Ian Kwok for his assistance with outreach and promotion.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute on Aging (R13AG063512 and K01AG061275 to CR; R35AG072310 to JLW). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the conference; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Agency for Health Research and Quality. (March, 2019). About learning health systems. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2022). Alzheimer’s and dementia: Facts and figures Alzheimers & Dementia, 18, 700–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2022). Care partner checklist. https://www.alz.org/careplanning/downloads/caregiver-profile-checklist.pdf

- Amjad, H., Mulcahy, J., Kasper, J. D., Burgdorf, J., Roth, D. L., Covinsky, K., & Wolff, J. L. (2021). Do caregiving factors affect hospitalization risk among disabled older adults? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(1), 129–139. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.,& Perrin, A. (2020). Tech adoption climbs among older adults. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/ [Google Scholar]

- Black, B. S., Johnston, D., Leoutsakos, J., Reuland, M., Kelly, J., Amjad, H., Davis, K., Willink, A., Sloan, D., Lyketsos, C., & Samus, Q. M. (2019). Unmet needs in community-living persons with dementia are common, often non-medical and related to patient and caregiver characteristics. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(11), 1643. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218002296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick, J. (April 2, 2019). AMA, UnitedHealth partner for social determinants IDC-10 project. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/ama-unitedhealth-partner-for-social-determinants-icd-10-project

- Bruening, R., Sperber, N., Miller, K., Andrews, S., Steinhauser, K., Wieland, G. D., Lindquist, J., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Ramos, K., Henius, J., Kabat, M., & Van Houtven, C. (2019). Connecting caregivers to support: Lessons learned from the VA Caregiver Support Program. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(4), 368–376. doi: 10.1177/0733464818825050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf, J., Roth, D. L., Riffin, C., & Wolff, J. L. (2019). Factors associated with receipt of training among caregivers of older adults. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(6), 833–835. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger, C., Berg, K., Fortinsky, R., & Hepburn, K. (2021). Addressing tactical challenges in embedding Tele-Savvy in a pilot pragmatic trial. Innovation in Aging, 5(Supp 1), 175–175. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab046.662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, S. J., Loewenstein, D., Schulz, R., Nair, S. N., & Perdomo, D. (2013). A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(11), 1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services (2013). Working for quality: 2013 annual progress report to Congress: National strategy for quality improvement in health care. January 2020. https://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/reports/index.html#improvequal

- Fortinsky, R. H., Gitlin, L. N., Pizzi, L. T., Piersol, C. V., Grady, J., Robison, J. T., Molony, S., & Wakefield, D. (2020). Effectiveness of the care of persons with dementia in their environments intervention when embedded in a publicly funded home- and community-based service program. Innovation in Aging, 4(6), igaa053. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igaa053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, L. N., Marx, K., Scerpella, D., Dabelko-Schoeny, H., Anderson, K. A., Huang, J., Pizzi, L., Jutkowitz, E., Roth, D. L., & Gaugler, J. E. (2019). Embedding caregiver support in community-based services for older adults: A multi-site randomized trial to test the Adult Day Service Plus Program (ADS Plus). Contemporary Clinical Trials, 83, 97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J. M., Riffin, C., Bangerter, L. R., Schaepe, K., & Havyer, R. (2022). Provider perspectives on integrating family caregivers into patient care encounters. Health Services Research. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harootyan, B., & Rozario, P. A. (2021). Addressing systemic inequities and policy deficiencies in the U.S. Public Policy & Aging Report, 31(4), 111–112. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prab027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, L. A., Reuben, D. B., Evertson, L. C., Serrano, K. S., Ercoli, L., Grill, J., ... & Wenger, N. S. (2015). Unmet needs of caregivers of individuals referred to a dementia care program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(2), 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The John A. Hartford Foundation. (2021, November 29). American Journal of Nursing article series: Supporting family caregivers in the 4Ms of an age-friendly health system. https://www.johnahartford.org/dissemination-center/view/american-journal-of-nursing-article-series-supporting-family-caregivers-in-the-4ms-of-an-age-friendly-health-system

- Kelly, K., Wolfe, N., Gibson, M., & Feinberg, L. (2013). Listening to family caregivers: The need to include family Caregiver Assessment in Medicaid home- and community-based service waiver programs - Digital Collections - National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101624597-pdf [Google Scholar]

- Levine, C., Halper, D., Peist, A., & Gould, D. A. (2010). Bridging troubled waters: Family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Affairs, 29(1), 116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, L. L., & Gaugler, J. (2021). Recommendations for the future science of family caregiving services and supports: A synthesis of recent summits and national reports. In Gaugler J. (Ed.), Bridging the family care gap. Academic Press, 141–176. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. (2015). NIA health disparities framework. November 5, 2018. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/osp/framework

- National Institute on Aging IMPACT Collaboratory. (2021). Pilot pragmatic clinical trial to embed Tele-Savvy into health care systems. https://impactcollaboratory.org/richard-fortinsky-phd-pilot/

- Phillips, K., & Wolfe, M. (2021). Promoting health equity through partnerships. Innovation in Aging, 31(4), 151–154. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab046.972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K., Chen, E. K., Riffin, C., Prigerson, H., & Reid, M. C. (2015). Practice-based research priorities for palliative care: Results from a research-to-practice consensus workshop. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2237–2244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, A. M., Thunell, J., & Zissimopoulos, J. (2020). Addressing the diverse needs of unpaid caregivers through new health-care policy opportunities. Public Policy & Aging Report, 31(1), 19–23. doi: 10.1093/ppar/praa039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffin, C., Van Ness, P. H., Wolff, J. L., & Fried, T. (2017). Family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(8), 1821–1828. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. S., Durfey, S. N. M., Gadbois, E. A., Meyers, D. J., Brazier, J. F., McCreedy, E. M., Fashaw, S., & Wetle, T. (2019). Perspectives of Medicare Advantage Plan representatives on addressing social determinants of health in response to the CHRONIC Care Act. JAMA Network Open, 2(7), e196923. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willink, A., & DuGoff, E. H. (2018). Integrating medical and nonmedical services—The promise and pitfalls of the CHRONIC Care Act. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(23), 2153–2155. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1803292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. L., & Roter, D. L. (2011). Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 612–632. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]