Abstract

The cDNA of a 14-kDa trypsin inhibitor (TI) from corn was subcloned into an Escherichia coli overexpression vector. The overexpressed TI was purified based on its insolubility in urea and then refolded into the active form in vitro. This recombinant TI inhibited both conidium germination and hyphal growth of all nine plant pathogenic fungi studied, including Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus, and Fusarium moniliforme. The calculated 50% inhibitory concentration of TI for conidium germination ranged from 70 to more than 300 μg/ml, and that for fungal growth ranged from 33 to 124 μg/ml depending on the fungal species. It also inhibited A. flavus and F. moniliforme simultaneously when they were tested together. The results suggest that the corn 14-kDa TI may function in host resistance against a variety of fungal pathogens of crops.

High levels of enzyme inhibitors found in the seeds of many plant species serve as storage or reserve proteins, as regulators of endogenous enzymes, and as defensive agents against attacks by animal predators and insect or microbial pests (15). Among these inhibitors, some were found to have activity against both trypsin and α-amylase (3, 16, 17).

The most extensively studied enzyme inhibitor is trypsin inhibitor (TI). Direct evidence of TI involvement in plant defense is that the expression of the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) TI gene in tobacco increased host resistance against herbivorous insects (7). Antifungal activities have also been reported for TI proteins from several crops, including TIs from barley (18) and trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors from cabbage (14) as well as the 22-kDa TI from corn (8) and the 24-kDa cysteine protease inhibitor from pearl millet (9). However, most were described to be active only against a very limited group of fungi. In a recent report from this laboratory (4), a TI was described with efficacy against Aspergillus flavus, the major fungus causing extensive crop loss in corn, cotton, peanut, and tree nuts due to contamination with aflatoxins. This 14-kDa corn TI is present at high levels in corn genotypes resistant to A. flavus infection but at low or undetectable levels in susceptible genotypes (4). The same TI has also been reported to be a specific inhibitor of activated Hageman factor (factor XIIa) of the intrinsic blood clotting process (6), as well as an inhibitor of α-amylases from certain insects (1, 3). Purification of the 14-kDa TI from corn requires large quantities of resistant corn kernels, which are usually in short supply. This has hampered efforts to test its efficacy against other important pathogens and to investigate its mechanism of inhibition. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to overexpress this protein in Escherichia coli to obtain large quantities and to use the purified active recombinant TI to test for inhibition of various plant-pathogenic fungi.

Overexpression of the TI gene in E. coli and purification technique.

The complete coding region of mature corn 14-kDa TI cDNA (GenBank accession no. X54064) (19) was amplified from plasmid pT7-7 with Taq polymerase by using the primer pair 2041 (5′ GAGCTCTTACTTGGAGGGCATCGTTCCGC) and 2164 (5′ CATATGAGCGCCGGGACCTCCTGC) with mismatches (underlined) to introduce an NdeI (5′ end) or SacI (3′ end) restriction site. After cloning into TA cloning vector pCRII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and complete sequence analysis, the amplified 0.4-kb PCR product was subcloned into the unique NdeI and SacI sites of an E. coli overexpression vector, pET-28b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). Positive clones were identified by using PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The correct in-frame fusion of the construct was verified by DNA sequencing of positive transformants before it was transformed into an E. coli BL21 (DE3) expression host. TI expression was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM as previously described (5). The overexpressed TI was predicted to be 16.5 kDa, containing a vector His tag and a thrombin cleavage site at the N terminus (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHM) followed by the complete mature TI (127 amino acid residues) (19).

E. coli cells overexpressing TI were harvested from a 500-ml culture after 6 h of induction, washed twice with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and then resuspended in 10 ml of the same buffer. The cells were ultrasonically disrupted on ice with pulses delivered intermittently for 6 min. Inclusion bodies were recovered by centrifugation (18,000 × g, 20 min) and washed twice with the same buffer. The supernatant was saved as the water-soluble fraction. Inclusion bodies were then resuspended in 100 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 6 M urea, and urea-soluble proteins were separated from the urea-insoluble fraction by centrifugation (18,000 × g, 20 min) and saved as the urea-soluble fraction. This step was repeated three times. The resulting urea-insoluble fraction was dissolved in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 6 M urea and 140 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After insoluble cell debris was removed by centrifugation, proteins in the supernatant (β-mercaptoethanol-soluble fraction) were subjected to refolding with cystamine as described previously by Kohno et al. (10). Proteins which had precipitated during refolding were removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was concentrated in Centriprep-10 (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.), exchanged at least five times with equal volumes of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) to remove trace urea, and then filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter. The purity of the protein then was assessed by using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the method of Laemmli (12) before storage of the fractions in aliquots at −70°C. The content of overexpressed TI in each fraction was quantified with a Bio-Rad GS-700 gel densitometer.

Trypsin activity assay.

Trypsin-inhibiting activity of the purified recombinant TI was assayed as previously described with bovine pancreatic trypsin and, as a substrate, α-N-benzyl-dl-arginine-p-nitroanilide HCl (BAPNA) (4). All assays were conducted three times.

Antifungal assays.

The activity of this recombinant TI against the growth of nine plant-pathogenic fungi (see Fig. 2) was assayed in 10% potato dextrose broth (PDB) (Difco) by using microtiter plates as described previously (4). Conidia (7 days old) from V8 juice agar medium (5% [vol/vol] V8 juice, 2% [wt/vol] agar [pH 5.2]) maintained at 25°C were harvested in sterile water and diluted to 106/ml. For Cercospora kikuchii and Fusarium species, this test was done with macroconidia. Conidia were allowed to germinate and grow in the presence of TI at 50, 100, 200, and 300 μg/ml at 25°C for 12 h. Negative controls were 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) or heat-inactivated TI at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. The hyphal length of control or TI-treated fungi was measured with an ocular micrometer after 12 h of incubation at 25°C. For each treatment, the hyphal lengths were measured for at least 40 randomly selected hyphae, and the mean hyphal length was used for comparison. The hyphal length in the control containing heat-inactivated TI was similar to that in the phosphate buffer control. Conidium germination was based on counts of at least 100 conidia per replicate. For C. kikuchii, Fusarium graminearum, and Fusarium moniliforme, which produce multicelled conidia, a conidium was considered germinated if a hypha was visible for at least one of the cells. The bioassay was performed three times for A. flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus and twice for all other fungi, with three replicates per treatment. The data presented are means for all experiments.

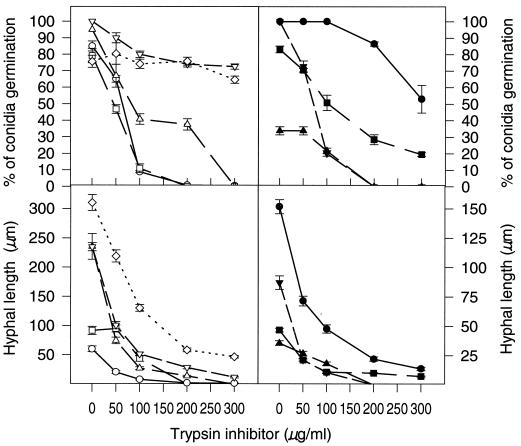

FIG. 2.

Conidium germination and hyphal growth in the presence of TI overexpressed in E. coli. The percentage conidium germination and hyphal growth were determined after 12 h of incubation at 25°C in 10% PDB medium with different concentrations of TI. The data are means ± standard errors of three (for A. flavus and A. parasiticus) or two (all other fungi) repeated experiments. Symbols: ○, A. flavus AF13; □, A. niger; ▵, A. parasiticus; ▿, F. graminearum; ◊, F. moniliforme; ●, C. kikuchii; ■, P. chrysogenum; ▴, R. stolonifer; ▾, T. viride.

To mimic the field situation, where A. flavus and F. moniliforme frequently coexist in infected corn kernels (2), conidia of A. flavus and microconidia of F. moniliforme harvested from potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium were germinated and grown together in 10% PDB containing 100 μg of TI per ml for 12 h.

Purification and characterization of overexpressed TI.

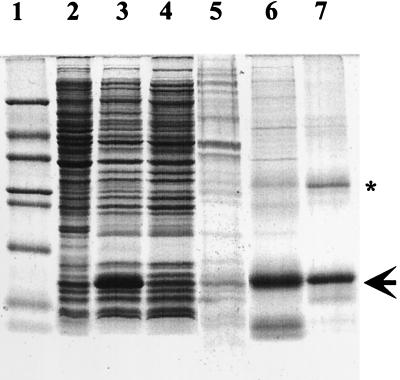

SDS-PAGE analysis of each fraction during purification showed that the overexpressed TI comprised 30 to 35% of total cell protein when the E. coli cells were induced and that it was not readily dissolvable in 6 M urea (Fig. 1). Overexpressed TI that remained insoluble in 6 M urea in the absence of β-mercaptoethanol prevented the use of traditional nickel ion affinity chromatography to purify this His-tagged recombinant TI; β-mercaptoethanol reacts with nickel ion affinity column material and forms precipitates. However, by taking advantage of this characteristic, the overexpressed TI in the urea-insoluble fraction was further enriched through repeated washings with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) containing 6 M urea, and the need for further purification was eliminated after refolding of the TI. The overexpressed TI accounted for more than 90% of the total protein in the β-mercaptoethanol-soluble fraction and for more than 96% of the total protein in the final refolded active TI fraction (Fig. 1). The yield of purified active TI was about 70 mg per liter of culture. It is believed that the second protein, having an apparent molecular mass of 33 kDa in the purified TI fraction (Fig. 1), is a dimer of the overexpressed TI based on the following observations (data not shown): (i) this 33-kDa protein cross-reacted with the antibody raised against purified native 14-kDa corn trypsin inhibitor, (ii) the resolving of the excised 33-kDa protein from a native gel on SDS-PAGE led to the appearance of the 16-kDa protein (the expected size of overexpressed TI), and (iii) the longer the denaturing time, the higher the intensity of the 16-kDa protein and the lower the intensity of the 33-kDa protein. However, we were not able to completely convert the 33-kDa protein to a 16-kDa protein by extending the denaturing time. This eliminated a possible concern that any future antifungal activity observed could be due to the presence of an antifungal compound other than TI in the extract.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of TI overexpressed in E. coli at different stages of purification and refolding. Lane 1, molecular mass standards (5 μg); lane 2, total protein extract from noninduced E. coli cells (10 μg); lane 3, total protein extract from induced E. coli cells (10 μg); lane 4, water-soluble-fraction proteins (10 μg); lane 5, urea-soluble-fraction proteins (5 μg); lane 6, β-mercaptoethanol-soluble-fraction proteins (5 μg); lane 7, purified and refolded active TI (2.5 μg, indicated by an arrow). The purity of this TI is 96% as quantified by gel densitometry. Molecular mass standards included were (from top to bottom) albumin (66 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (36 kDA), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), trypsinogen (24 kDa), TI (20 kDa), α-lactalbumin (14.2 kDa), and aprotinin (6.5 kDa). The asterisk indicates the possible dimer of this TI.

It was found that the purified recombinant TI was as effective as native TI isolated from corn in inhibiting proteolytic activity of trypsin. Refolded TI (7 μg) almost completely inhibited the activity of 10 μg of trypsin (molecular weight, 23,800), (the two were in nearly a 1:1 molar ratio). This result indicated that most of the overexpressed TI was active after refolding. The successful overexpression of TI in E. coli and the subsequent purification of large quantities of active TI from E. coli by simple procedures not only eliminated the need for intensive labor in the extraction and purification of TI from corn but also circumvented the need for large quantities of resistant kernels. Having large quantities of TI also enabled us to investigate its efficacy for inhibiting other fungal pathogens over a wide range of concentrations.

Inhibition of fungal growth.

The refolded active TI inhibited both conidium germination and hyphal growth of all nine fungi tested (Fig. 2). For most fungi, conidium germination decreased dramatically with increasing TI concentrations (Fig. 2). For six of the nine fungal species tested, conidium germination was reduced 50% at TI concentrations less than 115 μg/ml (Fig. 2, top panels). However, for F. graminearum, F. moniliforme, and C. kikuchii even the presence of 300 μg of TI per ml did not reduce conidium germination by 50% (Fig. 2). It might be significant that, of the nine species tested, the latter fungi are the only ones that produce large multicelled conidia. These conidia may have sufficient endogenous nutritional supplies to facilitate germination under adverse conditions.

The effects of this recombinant TI on conidium germination did not correlate with those on fungal hyphal growth. It appears that hyphal growth in general is more sensitive to TI inhibition than conidium germination (Fig. 2, bottom panels). Dramatic reduction in hyphal growth was observed in the TI range from 0 to 100 μg/ml for most fungi we tested. The calculated TI concentration required to cause 50% inhibition of hyphal growth (IC50) for A. flavus, A. parasiticus, C. kikuchii, F. graminearum, Penicillium chrysogenum, and Trichoderma viride ranged from 33 to 46 μg/ml, whereas the IC50 for Aspergillus niger, F. moniliforme, and Rhizopus stolonifer was about twofold higher (82 to 124 μg/ml). It appeared that the hyphae of A. flavus, A. parasiticus, C. kikuchii, F. graminearum, P. chrysogenum, and T. viride were more sensitive to inhibition by TI than those of A. niger, F. moniliforme, and R. stolonifer. Also, the IC50 of this recombinant TI for the growth of A. flavus was 33 μg/ml (2 μM), which is much lower than the concentration of native TI needed to show the inhibitory effect (4). In this study we tried to use the same medium to culture all the fungi as a more controlled means of comparison, and V8 juice medium was the only medium available because in other media, such as PDA medium, some of the fungi do not produce conidia or produce very few conidia. This was the reason for using F. moniliforme macroconidia in the study. However, when we examined the effect of TI on A. flavus and F. moniliforme, these fungi were grown together; PDA medium was therefore used to produce microconidia to mimic field conditions.

Simultaneous inhibition of hyphal growth of A. flavus and F. moniliforme.

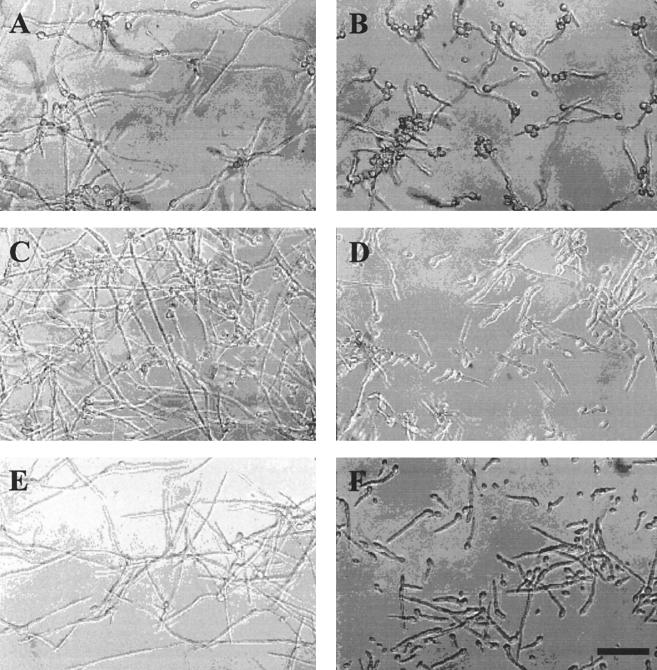

It was found that hyphal growth of A. flavus and F. moniliforme grown together was inhibited by TI as effectively as when they were grown separately (Fig. 3). More than 50% reduction of hyphal growth was obtained in the presence of 100 μg of TI per ml for F. moniliforme when microconidia were used. However, the calculated IC50 of TI for F. moniliforme hyphal growth was 124 μg/ml when macroconidia were used (Fig. 2). This supported our observation that macroconidia are less sensitive to TI inhibition than microconidia.

FIG. 3.

Simultaneous inhibition of A. flavus and F. moniliforme hyphal growth by TI protein overexpressed in E. coli at 25°C. (A and B) A. flavus treated with 0 and 100 μg of TI per ml, respectively, for 12 h; (C and D) A. flavus and F. moniliforme grown together and treated with 0 and 100 μg of TI per ml, respectively, for 12 h; (E and F) F. moniliforme treated with 0 and 100 μg of TI per ml, respectively, for 12 h. Bar = 25 μm.

Conclusions.

The two objectives of this study were to overexpress the 14-kDa TI in E. coli to obtain quantities suitable for testing protein bioactivity against several phytopathogenic fungi and to perform the actual antifungal bioassays. The original clone, pT7-7, was able to express TI in E. coli; however, the level was so low that it could be detected only by Western blot analysis. After the coding region of TI from pT7-7 was subcloned into vector pET-28b, the level of recombinant TI in E. coli total cell protein extract increased dramatically compared to that of clone pT7-7. Not only were suitable quantities obtained through overexpression in E. coli but also TI was purified by a novel procedure based on TI’s insolubility in urea in the absence of β-mercaptoethanol. The possibility exists that proteins overexpressed either in E. coli or in yeast with a high number of disulfide bonds also could be purified by this method.

The overexpressed TI inhibited hyphal growth and conidium germination not only in A. flavus but also in eight other fungi. Of these eight, seven are taxonomically similar, all being classified as hyphomycetes. The remaining fungus, R. stolonifer, a sporangiospore-producing zygomycete, is morphologically and taxonomically different. Inhibition of all nine fungi tested by TI indicates that this protein may have applicability for a broad range of fungal diseases. The fact that TI demonstrated efficacy simultaneously against A. flavus and F. moniliforme in vitro may also have significant implications. F. moniliforme, also a producer of mycotoxins, namely, fumonisins, commonly colonizes corn kernels throughout the world and has been isolated from kernels infected with A. flavus (11, 13). There are reports that F. moniliforme inoculated into corn ears can inhibit kernel infection by A. flavus and lead to reduced aflatoxin contamination in kernels (20, 21). However, interactions between these two fungi within kernels are not clear. Thus, it may be important for the development of resistance against aflatoxin contamination that the demonstrated efficacy of TI against A. flavus is not reduced in the presence of F. moniliforme, since they coexist in vivo. However, it may also become increasingly important to have corn kernel resistance against both F. moniliforme and A. flavus, if the attention given to animal and human health hazards associated with Fusarium toxins continues to increase.

Acknowledgments

The pT7-7 plasmid was a kind gift from Gerald R. Reeck, Department of Biochemistry, Kansas State University. We thank D. Bhatnagar, P.-K. Chang, M. A. Rousselle, and J. Yu for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by USDA Cooperative Agreement 58-6435-2-130.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blanco-Labra A, Chagolla-Lopez A, Martinez-Gallardo N, Valdes-Rodriguez S. Further characterization of the 12 kDa protease/alpha amylase inhibitor present in maize seeds. J Food Biochem. 1995;19:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain W J, Bacon C W, Norred W P, Voss K A. Levels of fumonisin B1 in corn naturally contaminated with aflatoxins. Food Chem Toxicol. 1993;31:995–998. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M-S, Feng G, Zen K C, Richardson M, Valdes-Rodriguez S, Reeck G R, Kramer K J. α-Amylases from three species of stored grain Coleoptera and their inhibition by wheat and corn proteinaceous inhibitors. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;22:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z-Y, Brown R L, Lax A R, Guo B Z, Cleveland T E, Russin J S. Resistance to Aspergillus flavus in corn kernels is associated with a 14 kDa protein. Phytopathology. 1998;88:276–281. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Z-Y, Lavigne L L, Mason C B, Moroney J V. Cloning and overexpression of two cDNAs encoding the low-CO2-inducible chloroplast envelope protein LIP-36 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol (Rockville) 1997;114:265–273. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajima Y, Pierce J V, Pisano J J. Hageman factor fragment inhibitor in corn seeds: purification and characterization. Thromb Res. 1980;20:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(80)90381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilder V A, Gatehouse A M R, Sheerman S E, Barker R F, Boulder D. A novel mechanism of insect resistance engineered into tobacco. Nature. 1987;330:160–163. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huynh Q K, Borgmeyer J R, Zobel J F. Isolation and characterization of a 22 kDa protein with antifungal properties from maize seeds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi B N, Sainani M N, Bastawade K B, Gupta V S, Ranjekar P K. Cysteine protease inhibitor from pearl millet: a new class of antifungal protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:382–387. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohno T, Carmichael D F, Sommer A, Thompson R C. Refolding of recombinant proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85018-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kommedahl T, Windels C E. Root-, stalk-, and ear-infecting Fusarium species on corn in the USA. In: Nelson P E, Toussoun T A, Cook R J, editors. Fusarium: diseases, biology and taxonomy. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press; 1981. pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillehoj E B, Zuber M S. Distribution of toxin-producing fungi in mature maize kernels from diverse environments. Trop Sci. 1988;28:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorito M, Broadway R M, Hayes C K, Woo S L, Noviello C, Williams D L, Harman G E. Proteinase inhibitors from plants as a novel class of fungicides. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:525–527. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson M. Seed storage proteins: the enzyme inhibitors. Methods Plant Biochem. 1991;5:259–305. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson M, Valdes-Rodriguez S, Blanco-Labra A. A possible function for thaumatin and a TMV-induced protein suggested by homology to a maize inhibitor. Nature. 1987;327:432–434. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivaraj B, Pattabiraman T N. Natural plant enzyme inhibitors. Characterization of an unusual α-amylase/trypsin inhibitor from ragi (Eleusine coracana Geartn.) Biochem J. 1981;193:29–36. doi: 10.1042/bj1930029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terras F R G, Schoofs H M E, Thevissen K, Osborn R W, Vanderleyden J, Cammue B P A, Broekaert W F. Synergistic enhancement of the antifungal activity of wheat and barley thionins by radish and oilseed rape 2S albumins and by barley trypsin inhibitors. Plant Physiol (Rockville) 1993;103:1311–1319. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen L, Huang J K, Zen K C, Johnson B H, Muthukrishnan S, Mackay V, Manney T R, Manney M, Reeck G R. Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA clone that encodes the maize inhibitor of trypsin and activated Hageman factor. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;18:813–814. doi: 10.1007/BF00020026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wicklow D T, Horn B W, Shotwell O L, Hesseltine C W, Caldwell R W. Fungal interference with Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin contamination of maize grown in a controlled environment. Phytopathology. 1988;78:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zummo N, Scott G E. Interaction of Fusarium moniliforme and Aspergillus flavus on kernel infection and aflatoxin contamination in maize ears. Plant Dis. 1992;76:771–773. [Google Scholar]