Summary

Treatment endpoints in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) are response of eosinophilic inflammation and of symptoms. Steroids and diet therapy are effective in inducing histologic response in EoE, but there may be poor correlation between histologic and symptomatic response. Despite this, we find that in clinical practice symptoms are commonly used to guide management without assessing histologic response. We hypothesized that symptom response alone is not reliable in assessing response to therapy and is confounded by endoscopic dilation. We conducted a systematic review and meta-regressions to estimate the association of histologic and symptomatic response, stratified by whether concurrent dilation was permitted. We performed a systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science for studies describing both histologic and symptomatic responses to dilation, steroid, and diet therapies. We abstracted the proportion of histologic response and symptom response. Studies were stratified by whether dilation was permitted. We performed meta-regressions of the association between the proportions with histologic and symptomatic response, stratified by whether dilation was permitted. We identified 1359 articles, of which 62 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 23 were included providing data on 1202 patients with EoE. Unstratified meta-regression of histologic versus symptomatic response showed moderate association and large heterogeneity (inconsistency index [I2] = 89%). In adult studies in which dilation was allowed, there was weak association between symptomatic and histologic response (β1 = 0.21), minimal symptomatic response of 67% and the heterogeneity persisted, I2 = 77%. In studies that prohibited dilation, maximal symptomatic response was 72% and was moderately associated with histologic response (β1 = 0.39) with less heterogeneity, I2 = 59%. Studies of EoE that permit dilation obscure the relation between histologic and symptomatic response and have a high floor effect for symptomatic response. Studies that prohibit dilation demonstrate moderate association between histologic and symptomatic response, but have a ceiling effect for symptomatic response. Our results demonstrate that success of dietary or medical management for EoE cannot be judged by symptoms alone, and require histologic assessment, particularly if dilation has been performed.

Keywords: eosinophilic, esophageal dilation, esophagitis, histology, meta-analysis, symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, allergic, and immune-mediated disease characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and the presence of eosinophils within the esophageal epithelium. Clinical presentation of EoE includes dysphagia, food impaction, and reflux in adults, as well as vomiting, difficulty feeding, and abdominal pain in children. By consensus, EoE is diagnosed in the setting of symptoms of esophageal dysfunction with histologic evidence of ≥15 eosinophils per high-power field (hpf). Current available medical therapies for EoE include topical steroids and elimination diets, both effective in targeting in the inflammatory component of the disease.1,2 Endoscopic dilation is also a safe and effective method to manage symptoms, particularly for fibrostenotic sequelae of the disease.3–5 Treatment goals include controlling esophageal eosinophilia and improvement of symptoms. While symptoms are an important measure of response to EoE treatment, prior reports suggest that patient-reported symptoms do not correlate well with histologic disease activity.6,7 Despite this, we have observed that many practitioners, both in community and academic settings, rely on symptoms alone to guide management without reassessing histologic response with repeat endoscopy and biopsy. We hypothesized that when dilation is performed concurrently with steroid or diet therapy, symptom response is not correlated with histologic response. Conversely, when dilation is not performed with medical or dietary therapy, there may be a stronger association between histologic and symptom response, but with a smaller proportion of patients with complete symptom improvement owing to residual fibrostenotic disease. Therefore, we aimed to estimate the association between histologic and symptomatic response in the published literature, stratified by whether dilation was permitted.

METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in reference databases (PUBMED, EMBASE, Web of Science) from January 2000 through December 2017. The MeSH terms used in the terms were ‘eosinophilic esophagitis’, ‘eosinophilia’, ‘esophagitis’, ‘glucocorticoids’, ‘steroids’, ‘diet therapy’, ‘balloon dilation’. Other search terms used included ‘eosinophilic esophagitis’, ‘esophageal’, ‘budesonide’, ‘fluticasone’, ‘prednisone’, ‘elimination’, ‘elemental’, and ‘endoscopic dilation’. For the EMBASE database, key search terms included ‘eosinophilic esophagitis’, ‘esophageal OR esophagus OR oesophageal OR oesophagus’, ‘budesonide’, ‘fluticasone’, prednisone’, ‘diet’, and ‘therapy’. The Web of Science database was searched to identify conference proceedings and abstracts; only free text word searches were performed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers (JC, RY) independently screened the database search for titles and abstracts. If a study appeared to meet eligibility criteria based on the abstract, the full text was reviewed for assessment of eligibility and data abstraction. Full texts in English were included. Studies included adult and pediatric patients previously diagnosed with EoE based on eosinophil-rich esophagitis with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction or by guideline criteria, treated with either topical or systemic steroids, elimination diet, and/or esophageal dilation. Cutoffs for eosinophilia varied from ≥15 to 24 eosinophils per high-power field. All experimental or observational studies including randomized controlled trials, prospective, and retrospective studies which measured proportions of both histologic and symptom response to the intervention were included. Studies including case reports and case series with less than 10 subjects were excluded. Studies that did not document both histologic and symptomatic response to therapy were excluded.

Data abstraction

The same two reviewers (JC, RY) independently abstracted information from each eligible study using a standardized data sheet. This data included study design, adult or pediatric participants, sample size, type of intervention (including dose, frequency, and duration), and if dilation was allowed with medical therapy. Unless stated otherwise in the study, concurrent dilation was assumed to be permitted. Data abstracted for histologic response included the study-specific definitions of response or remission and the proportion of subjects who obtained response. The proportion of subjects reporting symptomatic response, symptom scale used and if validated, and reported symptoms were also abstracted. Discrepancies were adjudicated by consensus between the two reviewers.

Data analysis

The meta-analysis on proportions of patients with symptomatic improvement and histologic responses was estimated using a random effects model. Meta-regressions of the association between the proportions of histologic and symptomatic responses were performed, estimating the slope of association (β1) and the proportion experiencing symptomatic response in the absence of histologic resolution (y-axis intercept, β0). Meta-regression was performed with and without restriction to studies which measured symptom response using validated or structured scores, then stratified by whether dilation was permitted. The placebo arms within studies prohibiting dilation were included as a reference for minimal symptomatic and histologic response. For each analysis, the regression coefficient and y-axis intercept were estimated. Heterogeneity and variation across the studies were estimated using the I2 statistic, where <25% is considered low heterogeneity and >75% high heterogeneity.8 Analyses were performed in Stata v. 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) using the metaprop using a random effects model and metareg commands.

RESULTS

Selection of studies

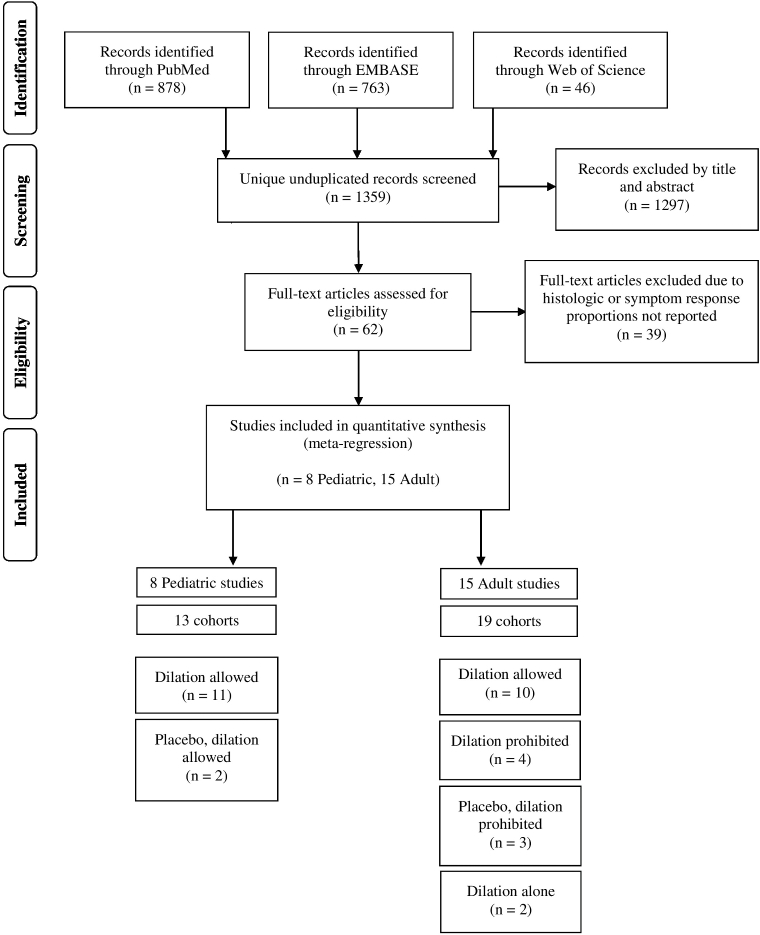

Our search strategy yielded 1359 references (Fig. 1) and 1297 were excluded by title and abstract. The remaining 62 studies were retrieved for evaluation of the full text. Of these, 39 were excluded because either the histologic and symptom responses were not reported. Ultimately 23 total studies were included in the final quantitative analysis, among which 15 included adults3,9–22 and 8 included pediatric subjects.23–30 Among these, 8 were RCTs (35%), 7 were prospective (30%), and 8 were retrospective (35%) in design.

Fig. 1.

Selection of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 23 individual studies included are shown in Table 1. The studies included 1202 total patients. A total of 19 (83%) studies allowed for dilation,3,9,10,14–19,21–30 whereas 4 (17%) prohibited concurrent dilation11–13,20 in the setting of steroid or diet therapy. Because individual studies often had more than one treatment arm, there were 25 total cohorts permitting dilation and 7 prohibiting dilation. Among adult studies of diet or steroid therapy that were included within the dilation permitted arm, 5 explicitly allowed for dilation and provided the rates of dilation which ranged from 16–45%.9,17–19,22 All patients within the two studies of dilation monotherapy received dilation.3,10 Dilation status was not clearly stated within any of the pediatric studies except one.29 Interventions included topical steroids in the form of swallowed fluticasone or oral budesonide in 14 (61%), diet therapy in 6 (26%), and dilation monotherapy in 2 (8.7%) studies. One (4.3%) study included three treatment arms of topical steroids, dietary restriction, and a combination of both modalities.30 Dietary interventions included elemental, targeted, six-food, four-food, two-food group, and milk elimination. Swallowed fluticasone or oral budesonide was the primary intervention in all four studies which explicitly prohibited dilation.

Table 1.

Summary of study characteristics.

| Study | Design | Population (% children) | Sample size | Treatment | Dilation permitted? | Definition of EoE | Definition of histologic response used in analysis | Proportion of histologic response | Symptom measurement instrument | Proportion of symptomatic response | Blinding performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Konikoff et al.23 | RCT | Pediatric (100%) | 36 (15 placebo, 21 fluticasone) | Fluticasone 880 mcg BID for 3 months | Not stated | ≥24 eos/hpf | <24 eos/hpf | Placebo 9% Fluticasone 65% | Unstructured | Placebo 0% Fluticasone 100% | Double blind |

| Remedios et al.9 | Pro. Cohort | Adults (0%) | 19 | Fluticasone 500 mcg BID for 4 weeks | Yes, 42% | >15 eos/hpf with dysphagia or food obstruction | <15 eos/hpf | 95% | Nonvalidated, structured | 100% | Pathologist blinded to treatments |

| Aceves et al.24 | Retro. Cohort | Pediatric (100%) | 20 | Budesonide 0.5, 1, 2 mg daily for 3–4 months | Not stated | ≥24 eos/hpf | <24 eos/hpf | 85% | Nonvalidated, structured | 90% | Not reported |

| Schaefer et al.25 | RCT | Pediatric (100%) | 80 (40 prednisone, 40 fluticasone) | Prednisone 1 mg/kg BID versus fluticasone 220–440 mcg QID for 12 weeks | Not stated | ≥15 eos/hpf | <15 eos/hpf | Prednisone 97%, Fluticasone 89% | Unstructured | Prednisone 100% Fluticasone 97% | No blinding |

| Bohm et al.10 | Cross-sectional | Adults (0%) | 16 | Dilation | Yes | Per consensus guidelines | Not included in meta-analysis | 0% | Nonvalidated, structured dysphagia score | 80% | Pathologist blinded |

| Dohil et al.26 | RCT | Pediatric (100%) | 24 (9 placebo, 15 OVB) | Budesonide 1 mg or 2 mg daily for 3 months | Not stated | ≥20 eos/hpf | <20 eos/hpf | Placebo 0% OVB 93% | Non-validated, structured | Placebo 56% OVB 80% | Double blind including pathologist |

| Peterson et al.11 | RCT | Adults (0%) | 30 (15 PPI, 15 fluticasone) | PPI versus Fluticasone 880 mcg BID for 8 weeks | No | ≥15 eos/hpf with dysphagia, food impaction, or chest pain | ≤15 eos/hpf | PPI 50% Fluticasone 31% | Validated RDQ and non-validated dysphagia score | PPI 25% Fluticasone 50% | Pathologist blinded No blinding of patients or investigators |

| Schoepfer et al.3 | Retro. Cohort | Adults (0%) | 63 | Dilation | Yes, 100% | Previously diagnosed | Not included in meta-analysis | 0% | Validated dysphagia score (Mellow-Pinkas) | 93% | Not reported |

| Straumann et al.12 | RCT | Adults (6%) | 36 (18 placebo, 18 budesonide) | Budesonide 1 mg BID for 15 days | No | ≥20 eos/hpf with dysphagia | ≤20 eos/hpf | Placebo 20% OVB 89% | Non-validated, structured dysphagia score | Placebo 22% OVB 72% | Double blind |

| Alexander et al.13 | RCT | Adults (0%) | 42 (21 placebo, 21 fluticasone) | Fluticasone 880 mcg BID for 6 weeks | No | ≥20 eos/hpf with dysphagia | Decrease in mean eos >90% | Placebo 0% Fluticasone 62% | Validated dysphagia score (MDQ-30) | Placebo 40% Fluticasone 47% | Double blind |

| Gonsalves et al.14 | Pro. Cohort | Adults (0%) | 50 | SFED for 6 weeks | Not stated | ≥15 eos/hpf with symptoms | ≤15 eos/hpf | 74% | Non-validated, structured dysphagia score | 94% | Pathologist blinded |

| Kagalwalla et al.27 | Retro. Cohort | Pediatric (100%) | 17 | Milk elimination for 6 weeks | Not stated | >15 eos/hpf with symptoms | ≤15 eos/hpf | 65% | Unstructured | 100% | Not reported |

| Moawad et al.15 | RCT | Adults (0%) | 42 (21 PPI, 21 fluticasone) | Fluticasone 440 mcg BID for 8 weeks | Yes, 36% | ≥15 eos/hpf and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction | <7 eos/hpf | PPI 33% Fluticasone 19% | Validated dysphagia score (MDQ 2-week) | PPI 83% Fluticasone 89% | Single blind (investigator) Pathologist blinded |

| Boldorini et al.28 | Pro. Cohort | Pediatric (100%) | 34 | Fluticasone 750 mcg TID for 6 weeks | Not stated | >15 eos/hpf | ≤20 eos/hpf | 74% | Unstructured | 100% | Not reported |

| Molina-Infante et al.16 | Pro. Cohort | Adults (2%) | 52 | FFED for 6 weeks | Not stated | >15 eos/hpf and dysphagia or food impaction | <15 eos/hpf | 54% | Non-validated, structured dysphagia score | 67% | Pathologist blinded |

| Wolf et al.17 | Retro. Cohort | Adults (0%) | 22 | Targeted elimination diet | Yes, 27% targeted diet | Per consensus guidelines | <15 eos/hpf | 32% | Unstructured | 68% | Not reported |

| Wolf et al.18 | Retro. Cohort | Adults (42%) | 221 | Budesonide 0.5 mg BID or fluticasone 440–880 mcg BID for 8 weeks | Yes, 25% | Per consensus guidelines | <15 eos/hpf | 57% | Unstructured | 79% | Not reported |

| Albert et al.19 | Retro. Cohort | Adults (25%) | 75 (48 fluticasone, 27 budesonide) | Children: Fluticasone 220 mcg BID or Budesonide 0.5 mg BIDAdults: Fluticasone 440 mcg BID or Budesonide 1 mg BID for 8 weeks | Yes, 45% adults | Per consensus guidelines | <15 eos/hpf | Fluticasone 48% Budesonide 56% | Unstructured | Fluticasone 64% Budesonide 83% | Pathologist blinded |

| Al-Hussaini et al.29 | Retro. Cohort | Pediatric (100%) | 11 | Fluticasone 250 μg or 500 μg BID for 2 months before taper | Yes, 100% | ≥15 eos/hpf | <15 eos/hpf | 46% | Unstructured | 100% | Not reported |

| Warners et al.22 | Pro. Cohort | Adults (0%) | 17 | Elemental diet for 4 weeks | Yes, 16% | >15 eos/hpf | ≤15 eos/hpf | 71% | Nonvalidated, structured dysphagia score and validated RDQ | 88% | Pathologist blinded |

| Dellon et al.20 | RCT | Adults (38%) | 87 (49 budesonide, 38 placebo) | Budesonide 2mg BID for 12 weeks | No | Per consensus guidelines | ≤15 eos/hpf | Placebo 8% Budesonide 47% | Validated dysphagia score (DSQ) | Placebo 45% Budesonide 69% | Double blind |

| Constantine et al.30 | Retro. Cohort | Pediatric (Unknown) | 63 (17 steroid, 14 diet, 32 combination) | Steroid: budesonide 1–2 mg BID, fluticasone BID. Diet: based on skin-prick or atopic patch testing Combination | Not stated | ≥15 eos/hpf | <15 eos/hpf | Steroid 50% Diet 60% Combination 80% | Unstructured | Steroid 71% Diet 64% Combination 91% | Pathologist blinded |

| Molina-Infante et al.21 | Pro. Cohort | Adults (19%) | 130 | 2-food group elimination for 6 weeks | Not stated | Per consensus guidelines | <15 eos/hpf | 43% | Nonvalidated, structured dysphagia score (DSS) | 75% | Not reported |

BID, twice per day; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; eos, eosinophils; FFED, four-food elimination diet; hpf, high-power field; MDQ-30, Mayo dysphagia questionnaire 30 day; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; Pro, prospective; QID, four times per day; RCT, randomized control trial; RDQ, reflux disease questionnaire; Retro, retrospective; SFED, six-food elimination diet; TID, three times per day.

Histologic and symptom response

Individual studies defined histologic response as a decrease of mean eosinophil count to <15 to 23 eosinophils per high-power field or by greater than 90% reduction. Symptomatic response was measured using various instruments. Four (17%) studies reported symptom improvement using validated scores such as the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire and Reflux Disease Questionnaire. Nonvalidated but structured tools such as clinic-specific dysphagia scores were used in 10 (44%) studies. The remaining 9 (39%) studies reported response using unstructured symptom assessments. Assessed symptoms broadly included dysphagia, reflux, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, regurgitation, odynophagia, chest pain, abdominal pain, food impaction, weight loss, failure to thrive, anorexia, and weight loss.

Among all medical and dietary interventions, histologic response ranged from 31 to 97% and symptomatic response from 47 to 100%. In placebo arms, histologic response ranged from 0 to 29% and symptomatic response from 0 to 56%. Two studies of dilation monotherapy for EoE reported symptomatic responses of 80 and 93% and histologic response of 0% in both. These two studies were excluded from further meta-regressions stratified for dilation.

Meta-analysis

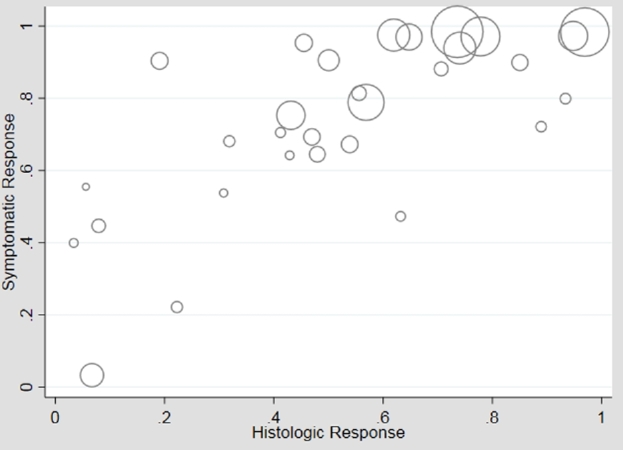

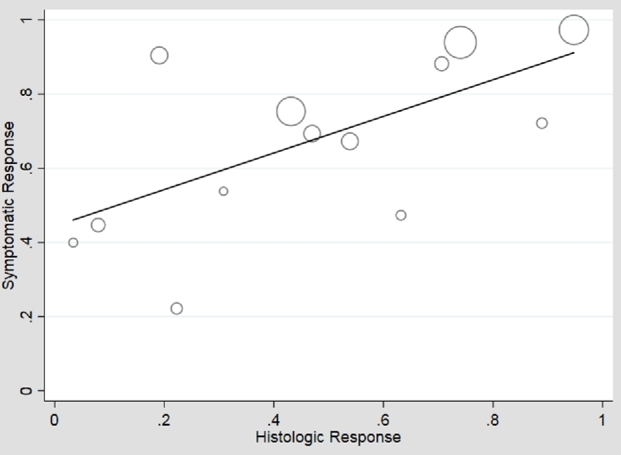

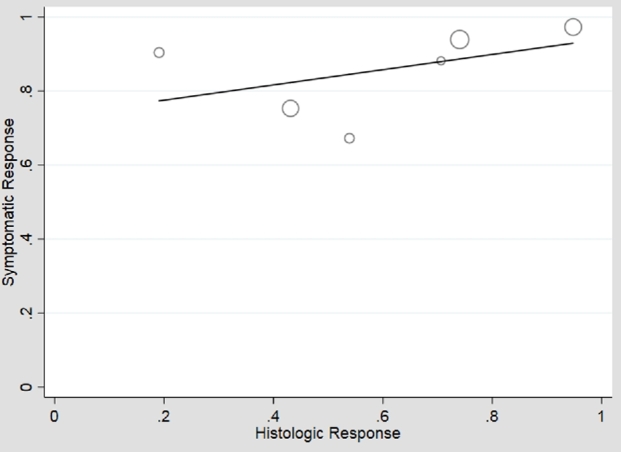

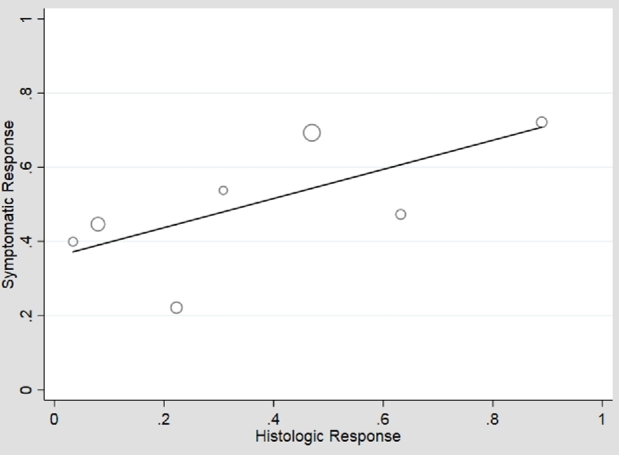

In an unstratified analysis of the remaining 21 adult and pediatric studies, meta-regression of histologic versus symptomatic response to any therapy showed moderate association (β1 = 0.64), 41% symptomatic response in the absence of histologic response (β0 = 0.41), but high heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) (Fig. 2). Use of an unstructured symptom assessment could lead to misclassification of symptoms and bias toward the null. Additionally, the frequency of use of endoscopic dilation may be considerably lower in children than adults, and there was an insufficient number of pediatric studies that measured symptoms with validated or structured tools to perform meta-regression on this group. Therefore, we performed analyses restricted to adult studies which measured symptoms using a validated or structured assessment tool (n = 10). Meta-regression of histologic versus symptomatic responses in these higher quality studies again showed moderate association (β1 = 0.49), moderate symptomatic response in the absence of histologic response (β0 = 0.44) and high heterogeneity (I2 = 83%) (Fig. 3). These higher quality studies were stratified into 6 which permitted dilation and 4 which prohibited dilation. In adult studies permitting dilation, the symptomatic response ranged from 67 to 100% with weak association with histologic response (β1 = 0.21) but high symptomatic response in the absence of histologic response (β0 = 0.73) (Fig. 4). The heterogeneity persisted with I2 = 77%. In the studies that prohibited dilation, the symptomatic response was lower than those which permitted dilation, ranging from 47 to 72%, corresponding with a low symptomatic response in the absence of histologic response (β0 = 0.36). Among these studies, the symptomatic response was more strongly correlated with histologic response (β1 = 0.39) and there was less heterogeneity in study results (I2 = 59%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Plot of histologic versus symptomatic response, unstratified analysis of all studies. Meta-regression found moderate association (β1 = 0.64, P < 0.01; β0 = 0.41, P < 0.01), but considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 89%).

Fig. 3.

Plot of histologic versus symptomatic responses, restricted to studies with higher quality symptom assessment, unstratified for dilation. There was moderate correlation (β1 = 0.49, P = 0.02; β0 = 0.44, P < 0.01) between histologic and symptomatic response, but high heterogeneity persists (I2 = 83%).

Fig. 4.

Plot of histologic versus symptomatic responses, among studies where dilation is permitted. Symptoms have a high ‘floor effect’ of response with the intercept at 0% histologic response having 73% symptomatic response (β0 = 0.73, P < 0.01). Histology correlates only weakly with symptomatic response (β1 = 0.21, P = 0.35), still with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 77%).

Fig. 5.

Plot of histologic versus symptomatic responses, among studies where dilation is prohibited. When dilation is prohibited, there is a lower symptomatic response in the absence of histologic response (β0 = 0.36, P = 0.01), and also a ceiling effect with symptomatic response peaking at 72%. Histology is modestly associated with symptomatic response (β1 = 0.39, P = 0.16) and there is less heterogeneity (I2 = 59%).

DISCUSSION

We performed a systematic review and series of meta-regressions, finding that in studies permitting endoscopic dilation, there is minimal correlation between histologic and symptomatic response, and stronger association when dilation is prohibited. In addition, in studies permitting dilation, there is a ‘floor effect’ represented by a higher y-axis intercept, by which a greater symptomatic response is observed even in the absence of histologic response. On the other hand, in studies prohibiting dilation, there is a ‘ceiling effect’ of symptoms, in which a minority of patients do not attain symptomatic response despite histologic response. These clinically important findings suggest that symptoms alone cannot be used to predict histologic response to therapy and direct assessment of histology is required to guide management decisions of steroid or diet therapy whether it be continuation, escalation, de-escalation, or change in therapy.

As a recently recognized disease, the ideal initial management of EoE is not clear and currently, there are no studies comparing the efficacy of topical steroids to elimination diet as either induction or maintenance therapies. Both steroids and diet are effective in improving esophageal eosinophilia and symptoms; however, definitions of these therapeutic endpoints are not well standardized. The clinical relevance of our findings can be appreciated by considering two clinical scenarios. Consider a patient with documented EoE who undergoes endoscopic dilation and concurrently begins using topical steroids. Without obtaining repeat biopsies, one cannot know whether improved symptoms are due to steroid therapy and resolution of eosinophilic inflammation (in which case steroids ought to be continued) or if the eosinophilia persists and the symptomatic response is largely due to the initial endoscopic dilation. If the latter case, a continuation of topical steroid exposes the patient to the financial expense and possible adverse effects without known therapeutic benefit. Conversely, consider a second patient with documented EoE also treated with topical steroids, but whose symptoms are not resolved and has not undergone endoscopic dilation. Without obtaining repeat biopsies, one does not know whether the failure of the clinical response is due to ongoing eosinophilic inflammation (in which case one should consider escalating the dose of topical steroids, switching to a different formulation, or transitioning to dietary exclusion) or a persistent fibrotic stricture despite resolved eosinophilia (in which case endoscopic dilation with maintenance topical steroid to prevent recurrence should be considered). In either case, the management decision relies on obtaining repeat biopsies and considering those results in the context of the symptom response and adherence to therapy. The same considerations apply if a patient is using dietary exclusion rather than topical steroids. In such a case, continuing dietary therapy without known histologic response exposes the patient to the inconvenience and decrement in quality of life without any known benefit. Conversely, altering dietary therapy without assessing histologic response leads to confusion about which foods the patient is actually sensitive to and a prolonged elimination course. There is no clear benefit to assessing histology in patients undergoing management by periodic endoscopic dilation alone without either medical or dietary therapy. But in patients being managed with either medical or dietary therapy (with or without endoscopic dilation), our results demonstrate that assessment of histologic response to therapy is crucial to guiding management decisions.

Our study was limited in that none of the included studies reported whether patients or the providers assessing symptoms were blinded to the histology results, which could lead to bias of correlation between histologic findings and reporting symptomatic response. In addition, there was considerable heterogeneity among the definitions for histologic response or remission, as well as for symptomatic response. Currently, this is a limitation that all existing reviews and meta-analyses for EoE face as EoE-specific symptom scores are only now being validated for use. To date, symptoms are measured and reported using a mix of validated scores such as Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire, nonvalidated but structured scales, and unstructured dichotomous symptoms assessments. Finally, there were few studies of EoE that explicitly prohibited dilation and the considerable heterogeneity observed may be attributed to the inclusion of studies with various designs and interventions. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, we were able to identify a stronger association between histology and symptoms in studies prohibiting dilation, and we can reasonably expect that the findings would be strengthened if these limitations did not exist.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of histologic and symptomatic responses to steroid and diet therapy for EoE stratifying for endoscopic dilation. A recent prospective observational study by Safroneeva et al. demonstrated that symptoms assessed using a validated EoE-specific symptom tool conferred only modest accuracy with histologic or endoscopic remission, but did not assess the role of dilation with concurrent pharmacologic or diet therapy for inclusion in our analysis.31 Dellon et al. explored the role of dilation in assessing symptom response without histologic response to topical steroids or diet therapy.32 They found that dilation before or after these therapies explained symptom response in histologic nonresponders. This study was not included in our analysis because symptomatic responses were reported from two separate instruments, stratified by histologic response. Strengths of this systematic review include the broad inclusion of all studies of pharmacologic and diet therapy for the treatment of EoE. The heterogeneity in therapies examined in the studies led to variability in histologic response, and we were able to leverage that variability to find correlations between symptomatic and histologic response. Finally, we performed subanalyses restricted to studies which measured symptoms with structured or validated assessments.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that symptoms do not correlate well with histologic responses to steroid or diet therapy, particularly if endoscopic dilation is performed. Furthermore, endoscopic dilation leads to a floor effect for symptomatic response and in the absence of endoscopic dilation, there is a ceiling effect resulting in a substantial proportion of patients not reaching full symptomatic response despite histologic resolution. Successful management of EoE with pharmacologic or diet cannot rely on symptoms alone and requires repeat endoscopy with biopsy.

Notes

Guarantor of the article: Joy W. Chang.

Specific author contributions: Joy Chang and Joel Rubenstein were involved in study concept and design. Joy Chang and Raymond Yeow were involved in the acquisition of data. Statistical analysis was performed by Akbar Waljee and Joy Chang. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by Joy Chang and Joel Rubenstein. Drafting of the manuscript was performed by Joy Chang. Critical revision of the manuscript was performed by Joel Rubenstein and Akbar Waljee. Study supervision was provided by Joel Rubenstein.

Financial support: Akbar K. Waljee is supported by a career development grant award (CDA 11–217) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service.

Potential competing interests: None.

Contributor Information

J W Chang, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA.

R Y Yeow, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA.

A K Waljee, Veterans Affairs Center for Clinical Management Research, Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA.

J H Rubenstein, Veterans Affairs Center for Clinical Management Research, Ann Arbor VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA.

References

- 1. Dellon E S, Gonsalves N, Hirano Iet al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 679–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lucendo A J, Molina-Infante J, Arias Aet al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J 2017; 5: 335–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schoepfer A M, Gonsalves N, Bussmann Cet al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety and impact on the underlying inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1062–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kavitt R T, Ates F, Slaughter J Cet al. Randomized controlled trial comparing esophageal dilation to no dilation among adults with esophageal eosinophilia and dysphagia. Dis Esophagus 2016; 29: 983–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Runge T M, Eluri S, Cotton C Cet al. Outcomes of esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: safety, efficacy and persistence of the fibrostenotic phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pentiuk S, Putnam P E, Collins M Het al. Dissociation between symptoms and histological severity in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009; 48: 152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dellon E S, Woodward K, Speck Oet al. Symptoms do not correlate with histologic response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: S432. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins J P, Thompson S G, Deeks J Jet al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Remedios M, Campbell C, Jones D Met al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: clinical, endoscopic, histologic findings, and response to treatment with fluticasone propionate. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bohm M, Richter J E, Kelsen Set al. Esophageal dilation: simple and effective treatment for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal rings and narrowing. Dis Esophagus 2010; 23: 377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peterson K A, Thomas K L, Hilden Ket al. Comparison of esomeprazole to aerosolized, swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Straumann A, Conus S, Degen Let al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 1526–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alexander J A, Jung K W, Arora A Set al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 742–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gonsalves N, Yang G Y, Doerfler Bet al. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moawad F J, Veerappan G R, Dias J Aet al. Randomized controlled trial comparing aerosolized swallowed fluticasone to esomeprazole for esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Barrio Jet al. Four-food group elimination diet for adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective multicenter study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134: 1093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolf W A, Jerath M R, Sperry S L Wet al. Dietary elimination therapy is an effective option for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1272–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wolf W A, Cotton C C, Green D Jet al. Predictors of response to steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis and treatment of steroid-refractory patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albert D, Heifert T A, Min S Bet al. Comparisons of fluticasone to budesonide in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 1996–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dellon E S, Katzka D A, Collins M Het al. Budesonide oral suspension improves symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic parameters compared with placebo in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2017; 152: 776–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Alcedo Jet al. Step-up empiric elimination diet for pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: the 2-4-6 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 1365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Warners M J, Vlieg-Boerstra B J, Verheij Jet al. Elemental diet decreases inflammation and improves symptoms in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45: 777–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Konikoff M R, Noel R J, Blanchard Cet al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1381–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aceves S S, Bastian J F, Newbury R Oet al. Oral viscous budesonide: a potential new therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schaefer E T, Fitzgerald J F, Molleston J Pet al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox Let al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 418–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kagalwalla A F, Amsden K, Shah Aet al. Cow's milk elimination: a novel dietary approach to treat eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 711–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boldorini R, Mercalli F, Oderda G. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in children: responders and non-responders to swallowed fluticasone. J Clin Pathol 2013; 66: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Al-Hussaini A. Savary dilation is safe and effective treatment for esophageal narrowing related to pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 63: 474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Constantine G, Seth N, Chokshi Net al. Combination steroid and test-based food elimination for eosinophilic esophagitis: a retrospective analysis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 64: 933–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky Met al. Symptoms have modest accuracy in detecting endoscopic and histologic remission in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dellon E, Wolf W A, Rusin Set al. Mo1183 esophageal dilation explains discordance between histologic and symptom response in a prospective study of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: S662. [Google Scholar]