Abstract

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a severe mental disorder with high morbidity and lifetime disability rates. Patients with SCZ have a higher risk of developing metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes mellitus, leading to increased mortality. Antipsychotics (APs), which are the mainstay in the treatment of SCZ, increase the risk of these metabolic perturbations. Despite extensive research, the mechanism underlying SCZ pathophysiology and associated metabolic comorbidities remains unclear. In recent years, gut microbiota (GMB) has been regarded as a ‘chamber of secrets’, particularly in the context of severe mental illnesses such as SCZ, depression, and bipolar disorder. In this scoping review, we aimed to investigate the underlying role of GMB in the pathophysiology of SCZ and metabolic alterations associated with APs. Furthermore, we also explored the therapeutic benefits of prebiotic and probiotic formulations in managing SCZ and AP-induced metabolic alterations. A systematic literature search yielded 46 studies from both preclinical and clinical settings that met inclusion criteria for qualitative synthesis. Preliminary evidence from preclinical and clinical studies indicates that GMB composition changes are associated with SCZ pathogenesis and AP-induced metabolic perturbations. Fecal microbiota transplantation from SCZ patients to mice has been shown to induce SCZ-like behavioral phenotypes, further supporting the plausible role of GMB in SCZ pathogenesis. This scoping review recapitulates the preclinical and clinical evidence suggesting the role of GMB in SCZ symptomatology and metabolic adverse effects associated with APs. Moreover, this scoping review also discusses the therapeutic potentials of prebiotic/probiotic formulations in improving SCZ symptoms and attenuating metabolic alterations related to APs.

Keywords: antipsychotics, fecal transplatation, gut microbiota, prebiotic, probiotic, schizophrenia

Introduction

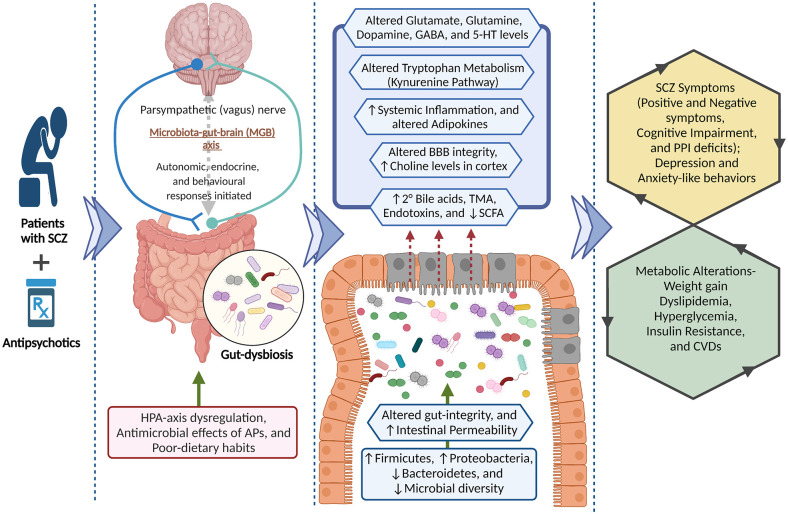

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a severe mental illness affecting 20 million people worldwide. Compared to the general population, patients with SCZ have a two- to three-fold higher mortality rate and 10–25 years reduced life expectancy, mainly due to the increased incidence of cardio-metabolic comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1–3 Impaired glucose homeostasis in patients within the first episode of psychosis (FEP) affirms an intrinsic risk for developing T2DM. Unfortuntately, antipsychotics (APs), which are the mainstay of treatment in SCZ spectrum disorders, have been found to further exacerbate this risk. 4 Despite their clinical efficacy, all APs, and particularly second-generation APs (SGAs), induce severe metabolic adverse effects, including weight gain, adiposity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia.5–7 Studies show that SGAs in acute and chronic treatment can disrupt glucose metabolism peripherally and centrally.8,9 Currently, the most common mechanistic insights behind AP-induced metabolic alterations (AIMA) include heterogenous neurotransmitter–receptor interactions, 10 impaired hypothalamic appetite-regulating pathways 11 and energy-sensing,12,13 altered glucose and lipid metabolism,5,14 and aberrant adipose tissue homeostasis (increased lipogenesis and inflammatory state). 15 However, despite years of research, it is still unclear how these mechanisms may interact to produce the metabolic perturbations associated with SCZ and AP medication.

The human gastrointestinal (GI) tract is considered the most diverse and densely populated microbial habitat. It contains approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and yeast collectively called the ‘gut microbiota’ or ‘gut microbiome’ (GMB). The GMB encodes for more than three million genes, and orders more than the human genome (~23,000 genes). Major bacterial phyla comprising the GMB include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes represent 90% of the GMB. For the Firmicutes phylum, the major genera include Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Enterococcus, and Ruminococcus. Bacteroides and Prevotella are the major genera of phylum Bacteroidetes, while Actinobacteria phylum (Bifidobacterium genus) is a less abundant component of GMB. 16 Gut bacteria are essential for regulating digestion, immunity, and metabolic homeostasis.16,17 These bacteria play a pivotal role in the digestion, fermentation, and absorption of several nutrients and metabolites such as carbohydrates, lipids, protein, and amino acids while producing secondary metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).16,18 Increased intestinal permeability and decreased epithelial integrity have been associated with an altered GMB. Similarly, the GMB has been shown to modulate blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity.19,20

The brain connects with the gut via bidirectional communication involving neuroendocrine and neuro-immune pathways. These connecting pathways are closely regulated by the GMB and together form the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis. The bidirectional communication of the MGB axis is such that changes in GMB composition can affect behaviors or behavioral perturbations may alter the GMB.19,21 The vagus nerve is a chief mediator of the bidirectional communication along the gut-brain axis through cholinergic activation of nicotinic receptors. 22 Sensory afferent neurons of the vagus nerve detect a diverse range of chemical and mechanical stimuli in the intestines and transmit messages to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the brainstem to initiate autonomic, endocrine, and behavioral responses.23,24 Working in the other direction, the vagus nerve also regulates gut functions including regional motility, secretion, permeability, and mucosal immune response which collectively can induce changes in GMB composition and activity. 25 Furthermore, a functioning GMB is also required for the development and regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Altered GMB in early life plausibly impacts neuro-immuno-endocrine functions and predisposes an individual toward stress-related disorders in adulthood. 26 Increased gut permeability due to intestinal barrier impairment has been associated with elevated corticosterone levels in early life stress. 27 The neuro-immuno-endocrine functions of the MGB axis are regulated by GMB-derived molecules such as SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites,28,29 and secondary bile acids (e.g. deoxycholic acid, ursodeoxycholic acid, and lithocholic acid), which are derived from primary bile acids (cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid) primarily by gut bacteria. 30 The GMB is also capable of secreting and utilizing neurotransmitters and neuroactive compounds such as serotonin (5-HT), dopamine, norepinephrine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which underly behavioral alterations.28,31–33 Likely, owing to these neuro-immuno-endocrine modulations (mainly HPA axis dysfunction), changes in GMB composition have been associated with severe mental illnesses such as major depression, 34 bipolar disorder, 35 and SCZ.36,37

Accumulating evidence suggests that GMB alteration largely associated with SCZ pathogenesis and AIMA. AP treatment causes dysbiotic (i.e. obesogenic) shifts in the GMB, including an increased abundance of Firmicutes and decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes phyla in rodents and human studies.22,38–41 In addition, changes in GMB composition have been associated with altered glutamate neurotransmission, 42 cognitive impairments in SCZ, and AP-induced increases in adiposity and alterations in glucose homeostasis and energy balance.43,44 Considering the potential role of GMB in the pathogenesis of SCZ and AIMA, several prebiotics and probiotics have been examined to improve disease symptoms45,46 and adverse metabolic effects associated with APs.47–50 The present scoping review synthesizes current clinical and preclinical evidence examining the role of the GMB in SCZ and AIMA, including the use of prebiotic/probiotic formulations as a therapeutic adjunct. Improved understanding of the links between GMB, SCZ, and AIMA and the therapeutic potential of prebiotic/probiotic formulations can provide further insight into the complex pathology of SCZ and holds important implications for improving metabolic outcomes in these patients.

Methods

The present study protocol was developed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s scoping review methodological framework.51,52

Search strategy

A search strategy including three main concepts (illness/treatment, GMB, and metabolic alterations) was developed, discussed, and implemented by the authors (R.S., N.S., and E.S.). Ovid Medline, EMBASE, PsychINFO, EBSCO’s CINAHL, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases were searched from inception to December 2021. Specific search terms and syntax were adjusted as necessary for each database. The full search string is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Screening and study selection

All search results were imported to Covidence for screening and automatic deduplication. Three authors (R.S., N.S., and E.S.) independently completed the title/abstract and full-text screening according to prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 2). Conflicts were resolved by discussion and consensus among the authors, and consultation with senior authors (S.M.A. and M.H.).

Relevant data extracted from each study were presented in tables with the following headings: publication (reference), study design (country of origin, study design, and experimental techniques), significant outcomes, type of prebiotic/probiotic used, and change in the GMB composition.

Results and discussion

Search results

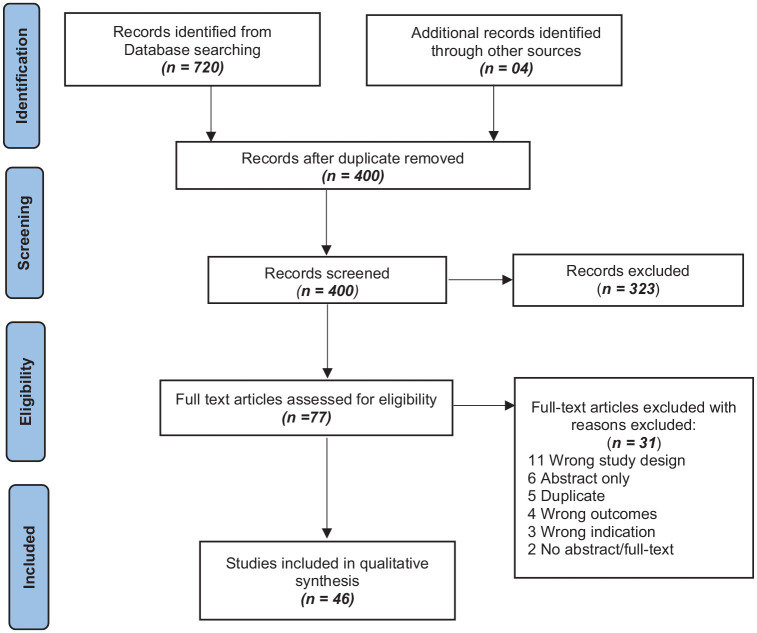

Our search from all the databases and gray literature search yielded 724 results, which upon deduplication reduced to 400. These 400 studies were subjected to the title and abstract screening, which excluded 323 studies, and 73 were assessed for full-text screening. In total, 27 studies were further removed in full-text screening, while 46 studies (13 preclinical and 33 clinical) included in quantitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

Literature search and selection process of included studies.

Role of the GMB in SCZ and AIMA

Emerging evidence from preclinical and clinical studies suggests the putative role of the GMB in SCZ symptomatology22,36,53 and AIMA.22,44,54,55 The evidence supporting this line of thought is summarized in the following sections.

Preclinical evidence – GMB and SCZ (Table A)

Preclinical studies in mice suggest that the GMB is important in modulating behavioral phenotypes resembling clinical symptoms of SCZ, such as social isolation and cognitive impairment. In one study, GMB depletion in adolescent mice using antibiotics was associated with SCZ-like behavioral phenotype, an altered tryptophan metabolic pathway, and reduced brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the adult brain. 56 Similar social and cognitive impairment has been observed in germ-free mice (GFM).22,56 Furthermore, fecal transplantation from SCZ patients to GFM has been shown to induce SCZ-like behavioral phenotypes, mainly psychomotor hyperactivity, learning and memory impairment, depression and anxiety-like behaviors, and increased startle response in the pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) test.42,57 These behavioral alterations were also associated with altered neurotransmitter levels, such as increased extracellular basal dopamine (in the prefrontal cortex), 5-HT (hippocampus), and elevation of the tryptophan degradation pathway (kynurenine-kynurenic acid pathway) in the brain and periphery, which play a pivotal role in SCZ pathogenesis. 57 Hippocampal glutamate hypofunction and disruptions in the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle are majorly associated with SCZ pathophysiology, mainly negative symptoms, cognitive decline, and heightened dopamine neurotransmission in mesocortical pathways.58,59 Related to this, mice which received fecal transplants from SCZ patients displayed decreased glutamate and increased glutamine and GABA levels in the hippocampus compared to mice that received fecal transplants from HCs.42,57 These behavioral and neurochemical phenotypes of SCZ were also associated with altered GMB composition. Mice that received the SCZ fecal transplant displayed an increased relative abundance of taxa such as Parabacteroides, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Odoribacter, and Fusobacterium, 57 as well as families, including Bacteroidaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Veillonellaceae. 42 Together, this evidence suggests a possible role of the GMB in the pathogenesis of SCZ.

Preclinical evidence – GMB and AIMA (Table 1B)

Table 1.

Preclinical findings showing the role of GMB in SCZ and AIMA.

| SNo. | Publication | Study details | Major outcomes | Change in GMB composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. GMB and SCZ | ||||

| 1. | Zhu et al. 57 | Country: China Study design: Fecal transplantation study Fecal samples from 11 SCZ patients and 10 HC were collected, processed, and transplanted in specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6 J mice. Experimental method(s): Animals were tested for SCZ-like behaviors in several paradigms. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing and 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Metagenomic Operational Taxonomic Units (mOTU) were used for taxonomic characterizations. |

Fecal transplantation in antibiotic-treated mice showed behavioral phenotypes like SCZ (mainly psychomotor hyperactivity, learning, and memory impairment). Furthermore, fecal transplanted mice also showed abnormal neurotransmitter levels like increased extracellular basal dopamine (in the prefrontal cortex), 5-HT (hippocampus), and elevated tryptophan degradation pathway (kynurenine-kynurenic acid pathway) in the brain and periphery as compared to the mice transplanted with fecal samples from HCs. |

GMB of SCZ donor had 261 mOTU, 112 were seen in GMB of fecal transplanted mice, while 55 mOTUs were present in significantly different relative abundance in SCZ and HC mice. In SCZ mice, majorly abundant taxa were Parabacteroides (distasonis and merdae), Bacteroides eggerthii, Clostridium (scindens and leptum), Odoribacter splanchnicus, Fusobacterium ulcerans, and Holdemania filiformis. |

| 2. | Zhu et al. 60 | Country: China Study design: Transplantation of SCZ-rich microbiota (rich in Streptococcus vestibularis) into male C57BL/6 J mice pretreated with antibiotics. Experimental method(s): Metagenomic shotgun sequencing was performed using Illumina platform, mOTU were used for taxonomic characterizations, KEGG databases were used for analysis of functional profiling. Behavioral tests such as open field test, social interaction in three-chamber social test, and elevated plus maze were performed. Neurotransmitters (dopamine, 5-HT, and GABA) were estimated in different tissue samples. |

Mice fecal transplanted with SCZ GMB (S. vestibulari) overall increased distance traveled and rearing in the open field, reduced social interaction in three-chamber social test, exhibiting behavioral phenotype of SCZ. S. vestibulari treated mice showed significantly lower levels of dopamine in serum, intestinal contents, colon tissue and decreased GABA levels in intestinal content immediately after transplantation. Increased 5-HT levels in intestinal content were also observed in fecal transplanted mice. Levels of neurotransmitters were not affected in the brain except decreased tryptophan levels in the prefrontal cortex of the mice compared to control mice receiving saline gavage. | GMB characterization was not done in the mice transplanted with SCZ-rich microbiota (enrich in S. vestibularis). But the clinical component of the study has shown the GMB characterization. |

| 3. | Zheng et al. 42 | Country: China Study design: Fecal transplantation study GMB from five male SCZ patients and five HC males was transplanted to the germ-free mice (FT-GFM) to explore the SCZ-like behavioral phenotypes. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was done for GMB characterization. Metabolite profiling was also done for different neurotransmitters. Behavioral tests like open field test, sociality, social novelty preference test, forced swim test, Y-maze, and pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) test were conducted in the FT-GFM. |

Fecal transplantation from SCZ in GFM showed locomotor hyperactivity, decreased depression and anxiety-like behaviors, increased startle response as compared to mice transplanted with the fecal sample from HCs. SCZ group mice also showed decreased glutamate, increased glutamine, and GABA in the hippocampus, which could be correlated with SCZ-like behaviors attributed to glutamatergic hypofunction. |

GMB characterization was done in the FT-GFMs; however, the clinical subdivision of the study displayed GMB analysis. Increased relatively abundant families: Bacteroidaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Veillonellaceae Decreased relatively abundant families: Acidaminococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Rikenellaceae, and Ruminococcaceae in SCZ compared to HCs. |

| B. GMB and AIMA | ||||

| 4. | Luo et al. 61 | Country: China Study design: In total, 48 male rats were treated with olanzapine (4 mg/kg) and metformin (300 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg) for 35 days. Experimental method(s): Histopathology biochemical assays were performed. 16 S rRNA sequencing was used for GMB composition analysis. |

Thirty-five days of olanzapine treatment showed significantly increased body weight, serum glucose, and lipids (increased triglycerides and LDL; decreased HDL) levels, reversed with metformin treatment. Olanzapine treatment also showed increased adipocytes and liver fibrosis, which was reversed by metformin treatment. |

Olanzapine treatment increased the Firmicutes: Bacteroidetes ratio. In species levels, olanzapine treatment showed a decreased relative abundance of Ruminococcus bromii compared with the control group. However, metformin co-administration increased the relative abundance of Bacteroides (uniformis and acidifaciens), Ruminococcus bromii, Desulfovibrio simplex, and Arcobacter butzleri. Still, it decreased the abundance of Lactobacillus reuteri and Bacteroides pectinophilus compared with the olanzapine-treated group. |

| 5. | Bahr et al. 62 | Country: USA Study design: Female wild-type C57BL/6 J mice were treated with risperidone (20–80 μg/day, orally in drinking water) for 60 days. A subgroup was given antibiotics (ampicillin and ciprofloxacin) along with risperidone for 10 days. Fecal transplantation was also done from risperidone-treated mice. Experimental method(s): Energy consumption, utilization, physical activity, core body temperature, resting metabolic rate were measured in combined calorimetry. 16s rRNA gene sequencing was done for GMB analysis. |

Risperidone treatment caused significant weight gain, associated with decreased energy expenditure and altered GMB. Fecal (phage) transplantation from the risperidone-treated mice significantly increased body weight and reduced the resting metabolic rate, supposedly by suppressing anaerobic metabolism. Furthermore, antibiotic treatment failed to attenuate risperidone-induced weight gain. However, risperidone differentially inhibited the growth of anaerobes in cultured gut microbes. |

Risperidone-treated mice showed increased relative abundance (32.6%) of phylum Firmicutes and decreased (22.4%) relative abundance of phylum Bacteroidetes.

In the phylum Firmicutes, Lactobacillus spp. was more abundant in the control group, while Allobaculum spp. was more abundant in the risperidone-treated group. However, phylum Bacteroidetes (Bacteroides spp.) was more abundant in risperidone-treated mice, while Alistipes spp. was more abundant in the control group compared with the risperidone-treated group. |

| 6. | Morgan et al. 38 | Country: USA Study design: Female C57BL/6 J germ-free mice were treated with olanzapine containing a high-fat diet (HFD, 50 mg/kg of diet) and only an HFD for 7 weeks. Furthermore, an HFD without medication was given for 2 weeks and then HFD with olanzapine or placebo for 7 weeks. Experimental Method(s): 16s rRNA gene sequencing was done for GMB analysis. |

Olanzapine-induced significant weight gain. GMB was found to be essential for weight gain induced by olanzapine. Mice did not show weight gain in germ-free conditions, whereas after colonization, mice treated with olanzapine gained significantly higher weight than the placebo diet. Olanzapine shifted the GMB to an obesogenic profile and showed direct antimicrobial activity. |

Olanzapine treatment increased the relative abundance of class Erysipelotrichi (phylum Firmicutes) and class Gammaproteobacteria (phylum Proteobacteria), as well as a decreased abundance of class Bacteroidia (phylum Bacteroidetes). These GMB disarrangements were associated with weight gain. Increased abundance of class Actinobacteria was also associated with weight gain, but it was independent of olanzapine treatment. Olanzapine also showed antimicrobial effects against common enteric bacterial strains such as Escherichia coli (phylum Proteobacteria) and Enterococcus faecalis (phylum Firmicutes). |

| 7. | Davey et al. 39 | Country: Ireland Study design: Rats were treated with olanzapine (2 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally) vehicle and antibiotic cocktail (neomycin, metronidazole, and polymyxin B) for 21 days. Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing. 30 min locomotor activity was performed in open field test. |

Antibiotic and olanzapine cotreatment showed reduced fat accumulation, overall weight gain, plasma free fatty acids, and reversed liver adipogenesis markers. | Rats treated with olanzapine had increased Firmicutes and decreased Bacteroidetes numbers, which was reversed by antibiotic and olanzapine cotreatment. |

| 8. | Davey et al. 40 | Country: Ireland Study design: Male and female rats were treated with 2 mg/kg/day and 4 mg/kg/day of olanzapine intraperitoneally for 21 days. Bodyweight measurement, food intake, locomotor activity, and adipose tissue were done. Expression (in adipose tissue) and plasma levels of inflammatory parameters were also estimated. Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing. 30 min locomotor activity was performed in open field test. |

Olanzapine significantly increased food intake, adiposity, body weight, and decreased locomotion, which were more prominent in female rats. Olanzapine treatment increased the mRNA expression of IL-6 and CD68, decreased SREBP-1c expression, and increased IL-8, IL-1 β, and leptin levels in female rats. |

Olanzapine treatment resulted in increased Firmicutes, decreased Bacteroidetes abundance, and reduced GMB diversity in female rats. However, male rats were less sensitive to olanzapine-induced GMB alterations. |

5-HT, serotonin; AIMA, AP-induced metabolic alterations; CD68, cluster of differentiation 68; FT-GFM, fecal transplanted germ-free mice; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GFM, germ-free mice; GMB, gut microbiome/gut microbiota; HC, healthy controls; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; IL, interleukin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; SCZ, schizophrenia; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein.

Rodent models have also been instrumental in characterizing AIMA and associated changes in the GMB. For example, in one study, olanzapine treatment in male and female rats increased body weight and adiposity, decreased locomotion, and increased the expression of interleukin (IL)-6 in adipose tissue and plasma levels of IL-8, IL-1 β, leptin, and free fatty acids.39,40 Olanzapine also increased fatty acid synthase (FAS) expression in the liver and CD68 (a macrophage marker, which causes the release of proinflammatory cytokines from adipocytes) expression in adipose tissue. These metabolic alterations were associated with increased abundance of Firmicutes and decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes, which was reversed in rats receiving olanzapine with antibiotic cocktail treatment.39,40 In line with these findings, olanzapine treatment in female C57BL/6 J GFM shifted the GMB to an obesogenic profile characterized by increased abundance of phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and decreased Bacteroidetes. Olanzapine also exhibited antimicrobial activities against common enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis. 38

Similarly, risperidone treatment in female wild-type C57BL/6 J mice has been shown to cause significant weight gain, associated with decreased energy expenditure and altered GMB composition, with a notable increase in the relative abundance of Firmicutes versus Bacteroidetes. Although risperidone-induced weight gain was not attenuated by antibiotic treatment, risperidone differentially inhibited the growth of anaerobes in cultured gut microbes. 62 Recently, metformin treatment was found to reverse olanzapine-induced metabolic alterations (increased body weight, serum glucose, triglycerides, LDL, and decreased HDL levels) and gut dysbiosis (increase in the Firmicutes: Bacteroidetes ratio) in rats. 61 Taken together, these preclinical findings further support the interplay of the GMB and AIMA.

Clinical evidence – GMB and SCZ (Table 2)

Table 2.

Clinical findings showing the role of GMB in SCZ.

| SNo. | Publication | Study details | Major outcomes | Change in GMB composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Yuan et al. 68 | Country: China Study design: A 24-week follow-up study involving 107 drugs naïve-FEP patients and 107 HCs. PANSS scores were assessed at Weeks 0, 6, 12, and 24 of AP treatment. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was used for the analysis of GMB composition. Uparse software (V7.0.1001) was used for sequence analysis. |

Dynamic changes were observed in the levels of hs-CRP and homocysteine and BMI after 24 weeks of risperidone treatment. SCZ patients showed lower alpha diversity at baseline compared with HCs, while a significant difference in beta diversity between SCZ and HC groups was also observed. | Twenty-four weeks of risperidone treatment showed increased alpha diversity compared with that of HCs at baseline. Significantly increased abundance of genus Romboutsia and decreased abundance of genus Lachnoclostridium was observed in the SCZ group, which was associated with treatment response in SCZ patients. |

| 2. | Chen et al. 70 | Country: China Study design: GMB profiling in 28 SCZ patients with violence (V.SCZ) and compared with 16 SCZ patients without violence (NV.SCZ). MacArthur Community Violence Instrument was used to assess violence, and PANSS was used to assess psychiatric symptoms. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was used to analyze GMB composition, and bioinformatic and statistical tools were used for differential GMB composition in both patient cohorts. |

This study profiled differences in the GMB composition between V.SCZ and NV.SCZ patients. | Differential GMB analysis showed 59 taxonomical compositions between V.SCZ and NV.SCZ patients, while 15 taxonomical compositions were found to be responsible for the difference in both groups, which is as follows: Five enriched microbial taxonomic compositions (phylum: Bacteroidetes, class: Bacteroidia, order: Bacteroidales, family: Prevotellaceae, and species: Bacteroides uniformis), and 10 poor microbial taxonomic compositions (phylum: Actinobacteria, class: unidentified Actinobacteria, order: Bifidobacteriales, families: Enterococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, genera: Enterococcus, Candidatus Saccharimonas, and Bifidobacterium, and species: Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum). |

| 3. | Zhu et al. 69 | Country: China Study design: Pilot study comprising 42 acute SCZ patients, 40 remission SCZ patients, and 44 HCs. Experimental method(s): PANSS score was used for the assessment of symptoms. 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis, followed by data analysis using R Version 3.3.2) and R Studio (Version 1.0.136) to explore the microbial diversities. Principal coordinate analysis (PCA) was used for identification of OTUs. |

Beta diversity of the acute SCZ group was significantly different from the remission SCZ and HC group. | GMB of the HC group was enriched with Coprococcus and Lachnospira, while acute SCZ groups were enriched with genera (Actinomyces, Chthoniobacterales, Fusobacteriales Turicibacter, and Turicibacterales). Remission SCZ group was found to be enriched with phyla (Desulfovibrio, Mitsuokella, Lactobacillus, and Succinivibrio) and families (Succinivibrionaceae and Lactobacillaceae) The abundance of Haemophilus was positively correlated with negative symptoms, cognition, excitement, and depression, whereas, Coprococcus was negatively correlated with negative symptoms. |

| 4. | Manchia et al. 71 | Country: Italy Study design: 38 SCZ patients and 20 HCs were recruited for a cross-sectional study. SCZ patients were also tested for response to APs [20 responders and 18 with treatment-resistant SCZ (TRS)] Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. Bioinformatic analysis was done using 16 S Metagenomics GAIA v.2.0 software. |

BMI was significantly higher in SCZ groups (responders and TRS) than HCs. No change in alpha diversity was observed. |

Several taxa were detected in the HC group but were absent in the SCZ groups. Phylum (Cyanobacteria), families (Cytophagaceae, Morganellaceae, and Paenibacillaceae), genera (Acetanaerobacterium, Gracilibacter, Haemophilus, Hespellia, Intestinibacter, Obesumbacterium, Turicibacter, and Weissella), and species (mainly Bacteroides sp, Bifidobacterium actinocoloniiforme, Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, Coprococcus eutactus, Streptococcus equinus, Prevotella sp., Ruminococcus sp., and Candidatus Dorea massiliensis) were populated only in the GMB of HCs, not in SCZ patients. |

| 5. | Nguyen et al. 72 | Country: USA Study design: 48 chronic SCZ patients and 48 matched (age, sex, BMI, antibiotic use, and sequencing plate) nonpsychiatric comparison subjects (HCs) were recruited for the study. Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. QIIME 2 Version 2019.7 was used for raw sequencing data processing, while ANCOM, a statistical program, was used for microbial taxa and functional pathways analysis. |

SCZ patients showed a significant difference in beta diversity in GMB composition and predicted functional pathways compared with HCs; however, no difference in the alpha diversity was observed. Within the SCZ group, no beta diversity differences were observed between AP users and non-AP users. |

The abundance of Lachnospiraceae was significantly higher in the SCZ group compared to HCs. Functional pathway analysis revealed alteration in biosynthetic pathways related to trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase and Kdo2-lipid A in SCZ. These metabolic pathways are linked to inflammatory cytokines associated with the risk of coronary heart diseases in SCZ. |

| 6. | Li et al. 73 | Country: China Study design: 38 SCZ patients and 38 demographically matched HCs were recruited for the study. In total, 35 SCZ patients were receiving AP treatment. Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. To elucidate the brain structural and functional differences, structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) and resting-state functional (rs-fMRI) were used. |

GMB alteration was associated with brain structure and functional changes. Low gray matter volume (GMV) and regional homogeneity, but the higher amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation in several brain regions of SCZ patients compared with HCs. A robust linear relationship between alpha diversity and GMV and regional homogeneity | A significantly lower abundance of genera Ruminococcus and Roseburia and a lower abundance of genus Veillonella were observed in SCZ patients compared with HCs. |

| 7. | Zhu et al. 69 | Country: China Study design: 197 SCZ patients and 200 HCs were enrolled in a two-stage cross-sectional study to compare short-chain fatty acid levels, systemic immune activation Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. Microbial diversity and differential OTU identification were done by R (Version 3.3.2) and R Studio (Version 1.0.136), and PCA analysis, respectively. |

SCZ patients showed significantly higher acetate, propionate, butyrate, and total SCFAs concentrations than HCs. SCFA levels were negatively correlated with cognitive function. | Bacteria producing SCFAs were enriched in the GMB of the SCZ patients.

60

GMB alpha diversity was increased in SCZ patients, which was positively associated with SCFA concentration in serum but not in feces. Patients with higher circulating SCFAs also showed immune activation (increased CRP, IL-6, soluble IL-2R, and sCD14 in serum). |

| 8. | Li et al. 74 | Country: China Study design: 82 SCZ patients and 80 demographically matched HCs were enrolled to evaluate the correlation between GMB composition and symptom severity in SCZ. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. Raw sequences were processed using QIIME 2, while DADA2 algorithm was performed to demultiplexing raw sequences and identifying the microbial features |

No significant difference in alpha diversity was found, but significant differences in beta diversity were observed between SCZ and HC. | Significantly increased abundance of phylum: Actinobacteria and genera: Collinsella, Corynebacterium, Lactobacillus, Mogibacterium, Succinivibrio, and undefined Eubacterium, and undefined Ruminococcus, whereas decreased abundance of phylum: Firmicutes and genera: Adlercreutzia, Anaerostipes, Faecalibacterium, and Ruminococcus were observed in SCZ group compared with HCs. In the SCZ group, the abundance of Succinivibrio was positively correlated with total and general PANSS scores, while Corynebacterium was negatively correlated with the negative scores of PANSS. |

| 9. | Li et al. 75 | Country: China Study design: 97 SCZ patients and 69 matched HCs were recruited in the study Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis and metagenomic for microbial enterotypes identification. Participants whose GMB was enriched with Prevotella and Bacteroides were marked as enterotype-P and enterotype-B, respectively. |

SCZ patients had significantly higher BMI than the HCs. Patients with enterotype-P had higher BMI. | SCZ group with enterotype-P had a significantly higher abundance of phyla Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, whereas HCs with enterotype-P had a significantly higher abundance of phylum Bacteroidetes. |

| 10. | Pan et al. 76 | Country: China Study design: 29 SCZ patients’ fecal samples were collected at two time points (onset and remission periods) and 29 samples from HCs. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA Miseq was used for GMB analysis. OTU clustering and taxonomic analysis was done using Usearch software (V.7.0). |

Bacterial taxonomic composition analysis showed no significant difference between SCZ patients and HCs at phylum and genus levels. However, there were differences in the GMB composition of SCZ patients with acute onset and remission (aSCZ and rSCZ, respectively). Furthermore, three genera, i.e., Eisenbergiella, norank-f Ruminococcaceae, and Turicibacter were found to be the best biomarker in aSCZ patients. |

In the SCZ patients, aSCZ GMB was found to be enriched with 15 taxa such as families (Ruminococcaceae, Actinomycetaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae), class: Deltaproteobacteria, orders (Desulfovibrionales and Actinomycetales), genera (Turicibacter, Anaerotruncus, Bilophila, Intestinibacter, Ruminococcaceae UCG-004, Flavonifractor, Ruminiclostridium-9, Actinomyces, and Acetanaerobacterium). On the other hand, the rSCZ group was found to be enriched in 19 genera such as Anaerofustis, Anaerotruncus, Atopobium, Actinomyces, Bilophila, Clostridium sensu-stricto-1, Comamonas, Intestinibacter, Flavonifractor, Epulopiscium, Parabacteroides, Turicibacter, norank f-Ruminococcaceae, Ruminococcaceae UCG-004, Lactonifactor, norank f-Christensenellaceae, Solobacterium, Prevotella, and Holdemania. Furthermore, compared with aSCZ, rSCZ patients had increased abundances of family Clostridiaceae-1, genera Clostridium sensu-stricto-1, and unclassified f-Peptostreptococcaceae. |

| 11. | Zhu et al. 60 | Country: China Study design: Metagenome-wide association of GMB in SCZ. 90 treatment-free SCZ patients (acutely relapsed and first episode of SCZ) and 81 healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled in a cross-sectional study. Experimental method(s): On the Illumina platform, Metagenomic shotgun sequencing was done. Furthermore, SCZ-associated GMB composition was determined using pathway/module analysis (KEGG). |

GMB of SCZ patients had greater alpha and beta diversity at genus and microbial gene level and comprised more genes than HCs. GMB alteration was functionally associated with SCFAs synthesis, tryptophan metabolism, and other neurotransmitters. | SCZ patients GMB harbored (rare in HCs) Lactobacillus fermentum, Enterococcus faecium, Alkaliphilus oremlandii, and Cronobacter sakazakii/turicensi.

Also, increased abundance of bacteria often present in the oral cavity (Veillonella Atypica/dispar, Bifidobacterium dentium, Dialister invisus, Lactobacillus oris, and Streptococcus salivarius) were found in SCZ patients as compared with HCs. |

| 12. | Zhang et al. 67 | Country: China Study design: A cross-sectional study enrolled in age, sex, and BMI-matched 10 AP-naïve patients with first-episode SCZ and 16 HCs. Experimental method(s): Gut microbiota and mycobiota analysis using 16 S rRNA gene sequencing and ITS1-based DNA sequencing from stool samples |

There was no significant difference in alpha diversity (microbial diversity and richness), while decreased beta diversity was observed in the SCZ group compared with HCs. | Increased relative abundance of harmful bacterial phylum (Proteobacteria) in SCZs compared with HCs. Decreased relative abundance of genera such as Lachnospiraceae and Faecalibacterium, which are essential for SCFAs production, were found in SCZs compared with HCs. |

| 13. | Ma et al. 66 | Country: China Study design: 40 AP-naïve first-episode SCZ patients, 85 chronic SCZ patients (receiving AP treatment), and 69 HCs were enrolled in the study. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis. UCHIME (v4.2.40) used for chimer checking and removal, and UPARSE algorithm was used for OTUs analysis. Taxonomical differences were assessed using DESeq2 package in R, and pathway analysis was done using KEGG databases. |

A lower microbiome alpha diversity index was observed in AP-treated SCZ patients but not in AP-naïve patients. SCZ-associated GMB was correlated with the aberrant volume of the right middle frontal gyrus. | Chronic AP-treated SCZ patients had increased relative abundance of taxa: phylum (Proteobacteria), families (Christensenellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae), genera (Bulleidia, Coprobacillus, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Shigella, Streptococcus, Trabulsiella, Veillonella, Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridiaceae_Clostridium, Enterobacer, Erysipelotrichaceae_Clostridium, Lachnobacterium) compared with HCs, and families (Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae. Streptococcaceae, Veillonellaceae) and genera (Escherichia, Fusobacterium, Megasphaera, SMB53, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Shigella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Enterobacteriaceae_unc, Citrobacter, Clostridiaceae_Clostridium, Enterobacter, Erysipelotricheae_Clostridium, Peptostreptococcaceae_Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Sutterella, Veillonellaceae_unc) compared with AP-naïve first-episode SCZ patients. Furthermore, chronic AP-treated SCZ patients had decreased relative abundance of taxa: phylum (Cyanobacteria), families (Pasteurellaceae, Turicibacteraceae, Streptophyta), and genera (Bacteroides, Parabacteroides Turicibacter, Bacteroidales, Barnesiellaceae, Rikenellaceae), as compared with HCs and phylum (Lentisphaerae) and genera (Lachnobacterium and Barnesiellaceae) as compared with AP-naïve first-episode SCZ patients. |

| 14. | Xu et al. 65 | Country: China Study design: The study included age and sex-matched 44 SCZ patients and 44 HCs. Experimental method(s): Shotgun metagenomic and 16 S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis for gut microbiota-associated epitopes (MEs). GUT-MEs were predicted with Immune Epitope Database (IEDB), Version 3.0. |

Patients with SCZ exhibited significantly reduced GMB richness or higher microbial diversity (MD) index than HCs. MD index was positively correlated with gut IgA levels. In the SCZ patients, increased glutamate synthase activity was observed, positively correlated with gut IgA levels. | Increased relative abundance of various taxa in SCZ compared with HCs: viz. phylum (Actinobacteria), class (Deltaproteobacteria), orders (Actinomycetales and Sphingomonadales), family (Sphingomonadaceae), genera (Eggerthella and Megasphaera) and species (Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Clostridium perfringens, Lactobacillus gasseri, and Megasphaera elsdeniis) were observed. Decreased relative abundance of various taxa in SCZ compared with HCs: order (Rhodocyclales), families (Alcaligenaceae, Enterococcaceae, Leuconostocaceae, Rhodocyclaceae, and Rikenellaceae), and genus (Enterococcus). |

| 15. | Nguyen et al. 77 | Country: USA Study design: The study included 25 chronic SCZ or schizoaffective disorder patients and 25 demographically matched HCs. 21 patients were receiving AP treatment at the time of enrollment. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis. Sequencing data were processed using QIIME 2, followed by Deblur algorithm for microbial sOUTs. |

SCZ patients had higher BMI and comorbid illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension compared with HCs. There was no significant difference in alpha diversity observed, while community-level separation in beta diversity was observed between SCZ and HC groups. Microbial taxa were also found to be associated with psychopathology. |

Increased relative abundance of genera (Anaerococcus, Blautia, Megasphaera, Ruminococcus), whereas decreased relative abundance of phylum (Proteobacteria), genera (Clostridium, Haemophilus, Oscillospira, and Sutterella), and species (Haemophilus parainfluenzae) in SCZ group as compared with HCs. |

| 16. | Zheng et al. 42 | Country: China Study design: 63 SCZ patients (mostly treated with APs) and 69 HCs were enrolled in a cross-sectional study. SGA used were clozapine (15), risperidone (14), olanzapine (9), chlorpromazine (5), aripiprazole (3), quetiapine (3), the combination of any two APs (9), and non-treated (5). Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis were done of GMB analysis. QIIME (Version 1.17) was used for demultiplexing the raw FASTQ files, and chimeric sequences were checked and eliminated by UCHIME. USEARCH (Version 7.0) was used for clustering the sequencing data to OTUs. Fecal microbial transplantation in mice, and behavioral tests mimicking SCZ-like behavioral phenotypes. |

Lower alpha diversity was observed in SCZ patients. Taxa such as Veillonellaceae and Lachnospiraceae were associated with SCZ severity. | Increased relatively abundant families (Bacteroidaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae, Veillonellaceae) and genera (Akkermansia, Fusobacterium, Megasphaera, Prevotella) were observed in SCZ patients. Decreased relatively abundant families (Acidaminococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Rikenellaceae, Ruminococcaceae), genera (Blautia, Citrobacter, Coprococcus, and Lachnoclostridium), and species such as Bacteroides (eggerthii and massiliensis), Collinsella stercoris, Haemophilus parainfluenzae were observed in SCZ patients. |

| 17. | Shen et al. 78 | Country: China Study design: Age, sex, and BMI-matched 64 SCZ patients receiving AP treatment for more than 6 months, and 53 HCs were enrolled in the study. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was done for GMB analysis. Raw sequence data were demultiplexed and analyzed using QIIME (Version 1.9.1). UCLUST method was used for selecting the OTUs. |

No significant difference in alpha diversity was observed, while a significant difference in beta diversity was observed. | Increased Proteobacteria and decreased Firmicutes relative abundance were observed in SCZ patients as compared with HCs. Genera such as Blautia, Coprococcus, and Roseburia were found to have a negative correlation with metabolic pathways associated with vitamin B6, taurine, hypotaurine, and glutathione. However, a positive correlation was found between the following genera and metabolic pathways: Coprococcus, Blautia, and Roseburia with methane; Collinsella with tyrosine; Clostridium with phenylalanine, butanoate, and beta-alanine. |

| 18. | Schwarz et al. 79 | Country: Germany Study design: Differences in the fecal microbiota between 28 FEP patients and 16 matched HCs were investigated in a 12-month longitudinal study. Experimental method(s): Fecal bacterial numbers were analyzed using qPCR for ‘all bacteria’. Number of cells present in the sample loaded in qPCR was calculated on the basis genome size and respective 16 S rRNA copy number per cell, which was identified using NCBI databases. Furthermore, metagenomic analysis on sequencing data using Illumina. |

Olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine (n = 10, 7, 8, respectively) were the most used APs with 20 days of median usage duration. | So significant difference was observed in the abundance of bacterial groups between the FEP patients and HCs. However, bacterial abundance was correlated with symptom severity in the PANSS score. The abundance of Bacteroides spp, Lactobacillus group, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae was positively correlated with negative symptoms and poor functioning, while only Lactobacillus group was associated with positive symptoms. |

| 19. | He et al. 64 | Country: China Study design: Longitudinal prospective observational study. Age and sex-matched 81 high risk (HR), 19 ultra-high risk (UHR) SCZ patients, and 69 HCs were enrolled. Experimental method(s): Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy ( 1 H-MRS) of the anterior cingulate cortex for choline quantification was done. 16 S rRNA sequencing analysis using QIIME 2 and DADA2 subOTUs. Prediction of functional profiles was done using KEGG database. |

In bioinformatic analysis, elevated pathways related to SCFAs biosynthesis (such as pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and fatty acid) were observed in UHR compared with HR SCZ patients and HCs. However, only the acetyl-CoA synthesis pathway was significantly increased. Furthermore, the 1H-MRS analysis demonstrated a significantly higher choline level in UHR subjects as compared with HCs. | Increased relative abundance of orders (Clostridiales, Lactobacillales, and Bacteroidales), genera (Lactobacillus and Prevotella), and species (only Lactobacillus ruminis) were observed in UHR compared with HR subjects and HCs. |

ANCOM, analysis of composition of microbes; AP, antipsychotics; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive peptid; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; FEP, first-episode psychosis; GMB, gut microbiome/gut microbiota; GMV, gray matter volume; HC, healthy controls; 1 H-MRS, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; HR, high risk; IEDB, Immune Epitope Database; IL, interleukin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MD, microbial diversity; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; OTU, operational taxonomic units; PANSS, positive and negative symptom scale; PCA, principal coordinate analysis; QIIME 2, quantitative insights into microbial ecology 2; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; SCZ, schizophrenia; SGA, second-generation APs; TRS, treatment resistant schizophrenia; UHR, ultra-high risk.

A plethora of evidence from human studies supports the involvement of the GMB in SCZ pathogenesis and metabolic alterations.22,36,53 A dysregulated MGB axis may explain the role of the GMB in SCZ pathogenesis, presenting as altered inflammatory processes and immune responses in SCZ patients. 22 Microbial translocation across the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) barrier, mediated by soluble CD14 (sCD14) and LPS-binding proteins (LBP), causes low-grade inflammation and immune reaction. Patients with SCZ exhibit altered patterns of these serological bacteria translocation markers including increased sCD14 seropositivity, and a positive correlation between levels of LBP and increased BMI. These alterations could be related to GI integrity and function.56,63 A magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in individuals with high and ultra-high risk for psychosis found altered GMB composition and higher choline levels in the cortex, which is a marker of membrane dysfunction. This suggests a role of gut dysbiosis-associated membrane dysfunction in SCZ. 64 GMB alterations in SCZ patients have also been associated with increased gut glutamate synthase activity and IgA levels, linking the GMB and immune response with SCZ pathophysiology. 65 Some recent studies have also reported gut dysbiosis in patients experiencing their first episode of SCZ.60,66,67 For example, Zhu et al. 60 found that the GMB of SCZ patients had greater alpha and beta diversity at the genus and microbial gene level and comprised more genes than healthy controls (HCs). These alterations in GMB composition were associated with SCFAs synthesis, metabolism of tryptophan and other neurotransmitters, such as GABA and glutamate. 60 Zhang et al. 67 investigated the GMB of AP-naïve patients with first-episode SCZ. They found an increased abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria belonging to phylum Proteobacteria, genus Romboutsia and decreased abundance of genera Lachnospiraceae and Faecalibacterium, essential for SCFA production.67,68 SCZ patients also showed increased serum and fecal concentrations of SCFAs, which was negatively correlated with cognitive function. Patients with higher circulating SCFAs showed immune activation evidenced by increased CRP, IL-6, soluble IL-2R, and sCD14 in Zhu et al.60,69

Furthermore, one study found that AP-treated patients with SCZ showed an increased relative abundance of phylum Proteobacteria and decreased abundance of phylum Cyanobacteria compared with HCs, and descreased abundance of phylum Lentisphaerae compared with AP-naïve first-episode SCZ patients. These GMB alterations were associated with abnormal right middle frontal gyrus volume. 66 Another study which examined the association of the GMB with brain structural and functional changes found that low gray matter volume (GMV) and regional homogeneity and high amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation were observed in several brain regions of SCZ patients compared with HCs. These patients had lower abundance of genera Ruminococcus and Roseburia, and lower abundance of genus Veillonella. 73

Differential abundance of microbial taxa also appears to be associated with varying psychopathology of SCZ including (1) an inverse relation between abundance of family Ruminococcaceae and severity of negative symptoms, (2) a positive relation between abundance of genus Bacteroides and severity of depressive symptoms, and (3) a positive relation between phylum Verrucomicrobia and self-reported mental well-being. 77 Lower alpha diversity was observed in SCZ patients receiving SGAs, while changes in abundance of taxa such as Veillonellaceae and Lachnospiraceae were associated with SCZ severity.42,72 Another study has reported the difference in GMB composition among the acute SCZ and remission SCZ patients. The remission SCZ group had enriched phyla (Desulfovibrio, Mitsuokella, Lactobacillus, and Succinivibrio). Furthermore, the abundance of Haemophilus was positively correlated with negative symptoms, cognition, excitement, and depression, whereas Coprococcus was found to be negatively correlated with negative symptoms. 69 In line with this, Pan et al. 76 have reported that compared with acute SCZ, remission SCZ patients had increased abundances of family Clostridiaceae-1 and genus Clostridium sensu-stricto-1 and unclassified family Peptostreptococcaceae. 76 Moreover, there was positive correlation between Succinivibrio abundance and total and general Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) scores, while Corynebacterium was negatively correlated with the negative scores of PANSS. 74

The increased relative abundance of Proteobacteria and decreased relative abundance of Firmicutes was also observed in SCZ patients receiving APs. The abundance of some genera (such as Blautia, Coprococcus, and Roseburia) was positively correlated with specific metabolic pathways (vitamin B6, taurine, and hypotaurine). In contrast, the abundance of some genera was negatively correlated with metabolic pathways of tyrosine (Collinsella), phenylalanine, and beta-alanine (Clostridium). 78 Furthermore, SCZ patients with or without violent behavior had different GMB profiles, which are highly enriched (phylum Bacteroidetes) and poorly enriched composition (phylum Actinobacteria). 70 Hence, in the light of the evidence presented, the GMB has a noticeable association with SCZ symptoms and pathophysiology.

Clinical evidence – GMB and AIMA (Table 3)

Table 3.

Clinical findings showing role of GMB in AIMA.

| SNo. | Publication | Study details | Major outcomes | Change in GMB composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Li et al. 81 | Country: China Study design: 94 drug naïve, first-episode SCZ patients and 100 HCs were enrolled in the study. Metabolic parameters such as BMI, fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, insulin, and HOMA-IR were measured. Both metabolic and GMB parameters were analyzed at the 12 and 24th weeks of risperidone treatment. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was used for fecal GMB analysis. Sequence library was cleaned with Cutadapt (V1.9.1), sequence read were cleaned with UCHIME algorithm, and chimers were eliminated. Alpha and beta diversity were estimated by Shannon diversity using QIIME (Version 1.7.0). |

At baseline, glucose levels were significantly higher in the SCZ group compared with HCs. Twenty-four weeks of risperidone treatment in SCZ patients significantly increased the BMI, HOMA-IR, serum lipids compared with baseline levels. | Twenty-four weeks of risperidone treatment in SCZ patients showed significant change in the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Christensenellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Proteobacteria, which was associated with the changes in metabolic parameters. At the baseline, the abundance of Christensenellaceae and Enterobacteriaceae was also significantly associated with increased BMI and elevated triglyceride and HOMA-IR after 24 weeks of risperidone treatment. |

| 2. | Pełka-Wysiecka et al. 54 | Country: Poland Study design: A 6-week observational prospective cohort study involving 20 SCZ patients. After 1 week of washout period for AP treatment (baseline), a 6-week olanzapine treatment (5–20 mg/day) was given. Experimental method: Analysis of fecal microbial composition was done using 16 S rRNA sequencing performed by the uBiome Inc. With the help of VSEARCH, sequences were filtered, and chimers were removed. KEGG functional pathway analysis was done using PICRUSt (Version 1.1.3). Furthermore, R software and R-based tools such as Phyloseq package (Version 1.24.2) were used for downstream pathway analysis. |

Olanzapine treatment improved clinical outcomes but caused a significant increase in BMI (in females). Olanzapine did not change the GMB composition. | The GMB of SCZ patients two specific types of taxonomic and functional cluster, which are Type 1: predominance of Prevotella and Type 2: higher abundance of Bacteroides, Blautia, and Clostridium. These changes were not altered by 6 weeks of olanzapine therapy. However, GMB was not associated with increased BMI and the clinical efficacy of olanzapine. |

| 3. | Yuan et al. 80 | Country: China Study design: In a 24-week study, 41 AP-naïve patients with first-episode SCZ and 41 HCs were enrolled. Experimental method(s): GMB analysis was done with qPCR. Five bacterial species were quantified using qPCR, where primers were designed as per previously done 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. Metabolic parameters were assessed using an automated analyzer. |

The 24 weeks of risperidone treatment significantly increased body weight, BMI, fasting serum glucose, low-density lipoproteins, triglycerides, antioxidant marker superoxide dismutase (SOD), inflammatory marker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and HOMA-IR, compared with HCs. | First-episode SCZ patients showed significantly decreased abundance of spp., such as Bifidobacterium, E. coli, and Lactobacillus compared with HCs. Risperidone treatment for 24 weeks significantly increased the abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. and E. coli, while significantly decreasing the abundance of Lactobacillus spp. and Clostridium coccoid group. Furthermore, change in fecal Bifidobacterium spp. was significantly correlated with body weight changes. |

| 4. | Flowers et al. 82 | Country: USA Study design: Cross-sectional study involving 117 patients with bipolar disorder (49 treated with SGAs and 69 non-AP treated). SGAs used were clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, asenapine, ziprasidone, lurasidone, aripiprazole, paliperidone, and iloperidone. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was carried out for detection of differentially abundant OTUs between groups. DNA sequencing was done using Illumina MiSeq V2 chemistry, followed by filtering the sequence with UCHIME19 and aligned to a mothur-adapted RDB database. Microbiome 16 S sequencing data were analyzed using software programs such as mothur (v.1.38.6) and R (v3.2). |

Higher BMI in AP-treated group. A significant difference in microbial abundance was observed between AP-treated and non-AP-treated groups. Significantly decreased species diversity was observed in AP-treated (females) compared with non-SGA-treated females, while males did not show any significant changes. |

Differentially abundant OTUs and respective genera between treatment groups were as follows: I1 (Lachnospiraceae), I25 (Akkermansia), and I32 (Sutterella). |

| 5. | Bahr et al. 41 | Country: USA Study design: 1. Cross-sectional study: 18 medically healthy males (9–15 years of age) on risperidone for 1 year (chronic treatment). 2. Longitudinal study: Five males (9–13 years of age) within 1 month of risperidone treatment; 10 psychiatrically ill (but not receiving any SGA) participants (10–14 years of age) served as AP-naïve psychiatric controls. Experimental method(s): 16s rRNA sequencing was used for GMB analysis. Extracted DNA was sequenced using Illumina with MiSeq instrument. |

Chronic risperidone treatment associated with higher BMI and lower Bacteroidetes: Firmicutes ratio compared to AP-naïve psychiatric control. The gradual decrease in Bacteroidetes: Firmicutes ratio associated with acute AP treatment and increases in BMI. | AP-treated group showed increased Bacteroidetes: Firmicutes ratio. Increased Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria and decreased Verrucomicrobia abundance In chronic AP treatment group, increased abundance of Clostridium sp., Lactobacillus sp., Ralstonia sp. and Erysipelotrichaceae family in those who gained significant BMI and C. aerofaciens in those who did not gain significant BMI. Family Ruminococcaceae are most abundant in participants with significant BMI gain. |

AIMA, AP-induced metabolic alterations; AP, antipsychotic; BMI, body mass index; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; GMB, gut microbiome/gut microbiota; HC, healthy controls; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; QIIME, Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology; SCZ, schizophrenia; SGA, second-generation antipsychotics; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Chronic AP-treated SCZ patients with metabolic comorbidities, including diabetes, weight gain, and hypertension, have also shown altered GMB composition. For example, in one study, first-episode SCZ patients were found to have decreased abundance of spp. such as Bifidobacterium, E. coli, and Lactobacillus as compared with HCs. Twenty-four weeks of risperidone treatment significantly increased body weight, BMI, serum glucose and lipids, antioxidant markers (i.e. superoxide dismutase), and high-sensitivity C-reactive peptide (hs-CRP). These metabolic changes were accompanied by an increased abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. and E. coli, and a decreased abundance of Lactobaccillus spp. and the Clostridium coccoide group compared with baseline. Change in the abundance of Bifidobacterium was associated with a change in body weight. 80 In another study, adolescents receiving risperidone treatment were found to have increased BMI, a lower Bacteroidetes: Firmicutes ratio, and increased abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria and decreased abundance of Verrucomicrobia compared with an AP-naïve psychiatric control group. 41

Another study reported that risperidone treatment for 24 weeks caused a significant change in the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Christensenellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Proteobacteria, which was associated with the changes in metabolic parameters such as increased BMI, HOMA-IR, and serum lipids. 81 On the contrary, 6 weeks of olanzapine treatment in an observational study caused significant weight gain but did not change the GMB composition in SCZ patients. 54 In a nutshell, the GMB could be regarded as a potential player in metabolic perturbations associated with AP treatment.

Probiotic/prebiotic formulations as therapeutic adjuncts in SCZ and AIMA

Probiotics are live organisms, mainly bacteria, that exert therapeutic benefits when taken in adequate quantities. Prebiotics are the complex and indigestible food material (such as oligosaccharides), which upon fermentation in the colon, produces metabolites (such as SCFAs) that nourish the GMB and promote health benefits. When probiotics and prebiotics are taken together, they are termed ‘synbiotics’; when they are intended to produce therapeutic benefits in patients suffering from mental illnesses, they are referred as ‘psychobiotics’.83,84

Preclinical evidence (Table 4A)

Table 4.

Effect of probiotic/prebiotic in SCZ and AIMA..

| S No. | Publication | Study design | Pro/Prebiotics used | Major outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Preclinical evidence | ||||

| 1. | Huang et al. 85 | Country: China Study design: Female C57BL/6 mice were fed with HFD for 8 weeks followed by 16 weeks of olanzapine (5 mg/kg/day, twice a day) treatment orally in phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and 200 µL of Akkermansia muciniphilasub (5 × 109 CFU) twice a day. Biweekly food intake and body weight were measured, and locomotor activity was measured in the last week. Experimental methods: Oral glucose tolerance test, olanzapine tolerance test, serum markers [glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-β, Alanine transaminase (ALT) and Aspartate transaminase (AST) levels], hepatic PEPCK and G6Pase activity, and fat deposition by oil-o-red staining. |

Probiotic formulation containing A. muciniphilasub (Akk I subtype, GP01 strain). | A.muciniphilasub colonization was confirmed after 16 weeks of treatment. Probiotic did not suppress the olanzapine-induced weight gain but increased the locomotion. Probiotic treatment reversed the olanzapine-induced increase in serum markers (insulin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, ALT, and AST). It also alleviated olanzapine-induced gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance, and systemic inflammation (serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels). |

| 2. | Syed and Nayak 48 | Country: India Study design: 36 Wistar rats were treated with olanzapine (2 mg/kg/day) and probiotic formulation VSL#3 (two doses, 0.6 mg/kg/day and 1.2 mg/kg/day) for 28 days. Experimental method(s): Estimation of body weight and serum parameters (fasting glucose, lipid profile, total cholesterol, HDL, and triglycerides) was done. |

Probiotic: VSL#3 (Sun Pharma, India) is a freeze-dried mixture containing 112.5 billion CFU/capsule of Bifidobacterium (longum, breve, and infantis spp.), Lactobacillus (acidophilus, plantarum, casei, and bulgaricus spps.), and Streptococcus thermophiles. | VSL#3 treatment in low and high doses has significantly reduced the body weight, total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and increased HDL cholesterol in olanzapine-treated rats. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 3. | Kao et al. 49 | Country: UK Study design: 48 female SD rats were treated with B-GOS®/saline and B-GOS®/olanzapine (10 mg/kg/day), and further acetate/saline, acetate/olanzapine. Experimental method(s): Rats were treated for 2 weeks. Brain histone deacetylase (HDAC) and histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity were measured in the brain. HDAC 1–4 and NMDA receptor subunits expression was measured in the cortex and hippocampus. GMB analysis was done with 16 S rRNA sequencing. |

Prebiotic: BimunoTM galacto-oligosaccharides (B-GOS®; 500 mg/kg/day) and sodium acetate (500 mg/kg/day). | B-GOS® treatment decreased the HDAC activity in the cortex and hippocampus and increased HDAC-1 and HDAC-3 mRNA expression in the cortex in olanzapine-treated rats. B-GOS® and acetate treatment increased the plasma acetate levels in saline-treated rats but decreased plasma acetate levels in olanzapine-treated rats. Acetate treatment significantly reduced the HAT activity in the cortex-hippocampus; increased HDAC- (3 and 4) mRNA expression in the hippocampus of rats treated with saline as well as olanzapine. Acetate treatment showed decreased body weight, but it was not significant as compared with the olanzapine-treated group. Olanzapine and acetate treatment did not significantly change GMB, mainly in Coprococcus spp., Escherichia/Shigella spp., Oscillibacter spp., Clostridium. Coccoides spp., Roseburia Intestinalis Cluster, and Clostridium XVIII cluster. |

| 4. | Dhaliwal et al. 50 | Country: India Study design: Female Swiss albino mice were treated with olanzapine (3 mg/kg, oral gavage) and VSL#3 probiotic formulation (20 × 109 CFU/day). Oxidative stress, inflammatory markers, oral glucose tolerance test, serum glucose, adiponectin, and triglyceride were estimated. Experimental method(s): GMB analysis was done using QIAamp® DNA stool mini kit (Qiagen) following qPCR. |

Probiotic: VSL#3 formulation contains Bifidobacterium (longum, breve, and infantis spp.), Lactobacillus (acidophilus, plantarum, casei, and bulgaricus spps.), and Streptococcus thermophilus. | VSL#3 treatment reversed the metabolic alteration, oxidative stress, and elevated proinflammatory cytokines in olanzapine-treated mice. VSL#3 treatment also restored the GMB disarrangement viz. increased the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia muciniphila, Enterobacteriaceae (decreased in olanzapine-treated group), and decreased the abundance of Firmicutes (increased in olanzapine-treated group). |

| 5. | Kao et al. 43 | Country: UK Study design: Female SD rats were treated with B-GOS®/saline and B-GOS®/olanzapine (10 mg/kg/day.) Experimental method(s): Rats were treated for 2 weeks. Immunoblotting, in situ hybridization, RT-PCR, and gut microbiota analysis with 16 S rRNA sequencing. |

Prebiotic: B-GOS®, 500 mg/kg/day | B-GOS® treatment attenuated olanzapine-induced weight gain. Olanzapine and B-GOS® cotreatment reduced the mRNA expression of the 5-HT2A receptor in the cortex of rats. B-GOS® treatment increased the cortical expression of GluN1 protein and GluN2A mRNA. B-GOS® treatment increased the acetate level in the saline-treated group, while showed reduced levels in the olanzapine-treated group. Furthermore, B-GOS® treatment increased the composition of Bifidobacteria spp. and decreased the genera such as Coprococcus spp., Escherichia/Shigella spp., Oscillibacter spp., Clostridium. Coccoides spp., Rosbeuria Intestinalis Cluster, and Clostridium XVIII cluster. |

| B. Clinical evidence | ||||

| 6. | Yamamura et al. 86 | Country: Japan Study design: 29 SCZ patients were treated with probiotic formulation for 4 weeks. Patients who showed reduction (>25%) in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale total score at the fourth week of the treatment were considered as ‘responders’ (n = 12) and who did not were considered as ‘non-responders’ (n = 17). Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis |

Probiotic formulation containing Bifidobacterium breve A-1 (B. breve MCC1274) containing 5.0 × 1010 colony-forming units (CFUs) | Increased abundance five functional genes responsible for higher lipids and energy metabolism were found in the responders compared with non-responders. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 7. | Liu et al. 87 | Country: China Study design: 100 patients with more than 10% weight gain after SGAs are being recruited in a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Subjects will receive probiotics (840 mg twice daily) + dietary fibers (30 g twice daily) and respective placebo combinations. |

Probiotics (Bifico is a triple live bacteria combination of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus) in a concentration of 5.0 × 107 CFU/g and Prebiotics (dietary fiber maltodextrin and perfect dietary fiber drink) | Ongoing study. The primary outcome will be weight gain. Secondary outcomes will be metabolic syndrome parameters, appetite score, and GMB composition. |

| 8. | Jamilian and Ghaderi 88 | Country: Iran Study design: In a randomized, double-blind placebo control study, out of 60 SCZ patients 30 received probiotics (8 × 109 CFU/day) plus 200 μg/day selenium, while 30 received placebo for 12 weeks. Experimental method(s): PANSS and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores were used for the assessment of SCZ symptoms. Biochemical parameters such as fasting plasma glucose, insulin, serum lipids, total antioxidant capacity (TAC), total glutathione and malondialdehyde, high sensitive-CRP levels were also measured for assessment of antioxidant and metabolic effects. |

Probiotic: LactoCare® containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium (lactis, bifidum, and longum) | Probiotic + Selenium co-supplementation for 12 weeks significantly improved the general PANSS scores compared with placebo. Significant elevation in TAC, total glutathione and reduction in total hs-CRP levels, decreased fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels and HOMA-IR index were observed in the supplemented group compared with placebo. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 9. | Kang et al. 89 | Country: China Study design: Randomized-controlled trial consisting of patients with the first episode of psychosis (FEP) having not used APs for at least 3 months before enrollment in the study. Patients were randomized for olanzapine (15–20 mg/day) or olanzapine plus probiotic formulation Bifico treatments for 12 weeks. Primary outcomes (weight gain, BMI, fasting insulin and insulin resistance), and secodary outocomes such as serum lipids (LDL, HDL, total cholesterol, triglycerides), PANSS scores, and appetite were meausred. |

Probiotics (Bifico is a triple live bacteria combination of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus at 5.0 × 107 CFU/g) | Probiotic cotreatment with olanzapine significantly reduced the fasting insulin and HOMA-IR compared with the olanzapine alone treated group. Probiotic cotreatment also reduced BMI and body weight compared with olanzapine alone, but the effects were not statistically significant. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 10. | Yang et al. 47 | Country: China Study design: 67 patients with SCZ or schizoaffective disorder were assigned to olanzapine (n = 34) and olanzapine with probiotic (n = 33) treatment for 12 weeks. Parameters such as body weight, BMI, and appetite latencies were measured at 3-time points (4, 8, and 12 weeks). |

Probiotics, a combined live bacteria combination of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Enterococcus, containing 1 × 107 CFU of each strain in a capsule. | A significant difference in weight gain and BMI was observed at the fourth week (decreased in the olanzapine and probiotic cotreatment group); however, it was not at the eighth and twelfth weeks. No difference was observed in appetite assessment. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 11. | Flowers et al. 90 | Country: USA Study design: 37 outpatients with SCZ or bipolar disorders were enrolled in the cross-sectional cohort study. Patients receiving SGAs were assigned to resistant starch supplementation for 14 days. Experimental method(s): 16 S rRNA sequencing was performed for GMB analysis. |

Prebiotic raw unmodified potato starch or resistant starch (~50% by weight). | No significant difference was observed between SGA users and non-SGA users at baseline. Decreased microbial diversity was observed in SGAs-treated females compared with non-SGA-treated females. Resistant starch supplementation showed an increased abundance of phylum Actinobacteria. |

| 12. | Okubo et al. 45 | Country: Japan Study design: An open-label, single-arm observational study includes 29 SCZ outpatients with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Experimental method(s): SCZ patients were treated with probiotic formulation for 4 weeks, and blood cytokines and GMB composition was investigated. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and PANSS scores were used. |

Probiotic formulation containing Bifidobacterium breve A-1 (1011 CFU/day) for 4 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of observation. | After 4 weeks of treatment, HADS and PANSS scores improved in the SCZ patients (responders) with a higher relative abundance of Parabacteroides than non-responders. Responders showed significantly increased IL-22 and TNF-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) expression while non-responders did not. |

| 13. | Severance et al. 46 | Country: USA Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized control trial (RCT). 56 SCZ outpatients (18–65 years of age) with psychotic symptoms were randomized to placebo and probiotic formulation (Bifiform Balance) for 14 weeks. Experimental method(s): Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the PANSS scale. Anti-Candida albicans and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae IgG antibodies were measured using ELISA. SGAs used were olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, quetiapine, haloperidol, and ziprasidone. |

Probiotic formulation containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (109 CFUs) and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bb12 (109 CFUs). | No difference in PANSS score was observed in probiotic supplemented SCZ patients. Furthermore, it had no effect on SCZ symptoms (PANSS score), but greater effects were seen for positive symptoms rather than negative symptoms. C. albicans IgG levels were significantly reduced by the probiotic formulation in males but not in females. Seronegativity for C. albicans in males showed improvement in positive symptoms and bowel movement. |

| 14. | Tomasik et al. 91 | Country: USA Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT. In total, 58 outpatients (18–65 years of age) with SCZ and schizoaffective disorder were randomized to placebo (27) and adjunctive probiotic (31). Experimental method(s): Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the PANSS scale. Multiplexed immunoassays and in silico studies. |

Probiotic formulation containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (109 CFUs) and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bb12 (109 CFUs). | Probiotics supplements had no effects on SCZ symptoms (PANSS score). Probiotic supplementation significantly decreased acute-phase reactant von Willebrand factor and increased the levels of MCP-1, BDNF, T-cell specific protein RANTES, Macrophage inflammatory protein 1 beta. In silico analysis suggested that probiotics regulated the immune functions via IL-17. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

| 15. | Dickerson et al. 92 | Country: USA Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT. 65 SCZ patients (18–65 years of age) with moderately severe psychotic symptoms were randomized to placebo and probiotic formulation. Experimental method(s): Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the PANSS scale. |

Probiotic formulation containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (109 CFUs) and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bb12 (109 CFUs) for 14 weeks. | No difference in PANSS score was observed in probiotics supplemented SCZ patients; however, they were less likely to develop bowel difficulty. GMB composition was not analyzed. |

5-HT, serotonin; AIMA, AP-induced metabolic alterations; ALT, Alanine transaminase; APs, Antipsychotics; AST, Aspartate transaminase; BDNF, Brain derived neurotrophic factor; BMI, Body mass index; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CFU, colony-forming units; CRP, C-reactive peptide; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; FEP, first episode of psychosis; GluN1, Glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit zeta-1; GMB, Gut microbiome/gut microbiota; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HDL, High-density lipoprotein; HFD, high-fat diet; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; IL, Interleukin; MCP-1, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; PBS, phosphate buffer saline; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; RANTES, Regulated upon Activation; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; Normal T Cell Expressed and Presumably Secreted; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; SCZ, Schizophrenia; SGA, second-generation APs; SD, Sprague dawley; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; TNF-α, Tumor-necrosis factor alpha; TRANCE, TNF-related activation-induced cytokine