Abstract

The white rot basidiomycete Trametes versicolor secretes a large number of peroxidases which are believed to be involved in the degradation of polymeric lignin. These peroxidases have been classified previously as lignin peroxidases or manganese peroxidases (MnP). We have isolated a novel extracellular peroxidase-encoding cDNA sequence from T. versicolor CU1, the transcript levels of which are repressed by low concentrations of Mn2+ and induced by nitrogen and carbon but not induced in response to a range of stresses which have been reported to induce MnP expression.

The lignin-degrading ability of the white rot basidiomycete Trametes versicolor has been well studied (2, 10). Along with laccases, two groups of heme-containing proteins, lignin peroxidases (LiP) and manganese peroxidases (MnP), have been reported to be involved in the ligninolytic process. LiP attacks both phenolic and nonphenolic aromatic residues, with the latter giving rise to cation radicals that fragment spontaneously (24). MnP catalyzes the oxidation of Mn(II) to Mn(III), which in turn can oxidize phenolic lignin subunits (14). LiP and MnP are both produced by white rot fungi as a number of isozymes which are encoded by families of structurally related genes. In one study, 16 forms of LiP and 5 forms of MnP were detected in a T. versicolor culture fluid (16). A number of genomic clones encoding LiP isozymes (21) have been characterized, and recently Johansson and Nyman (17) have described a genomic sequence encoding a T. versicolor MnP. In addition, a third type of peroxidase-encoding gene, PGV, has been isolated from T. versicolor PRL 572 (20). The expression of various isozymes of both the LiP and MnP subfamilies is differentially regulated at the level of gene transcription by physiological growth conditions such as carbon or nitrogen concentration (9, 13). Brown et al. (5) have demonstrated that production of mRNA encoding MnP in Phanerochaete chrysosporium is induced by the enzyme’s primary substrate, Mn2+. Furthermore, Mn2+ induction of different MnP isozymes is coordinately regulated in P. chrysosporium (9, 13, 32). Further studies have indicated that MnP production in P. chrysosporium is transcriptionally regulated by a number of other factors, including heat shock (6), H2O2, chemical stress, and molecular oxygen (26).

We report here the cloning and characterization of a novel extracellular peroxidase-encoding cDNA sequence (npr) from T. versicolor. The deduced amino acid sequence of the NPR protein contains the 10 invariant residues of all members of the plant peroxidase superfamily (41) (see Fig. 1). A comparison of the sequence with various MnP and LiP sequences reveals a high degree of similarity near the active site. In addition, the proposed Mn2+-binding residues of MnP are present in the deduced NPR. In contrast, the LiP residues suggested to interact with aromatic substrates are not present. This putative protein may therefore represent a new class of ligninolytic peroxidases. Using a reverse transcription (RT)-PCR approach, we have determined that, in contrast to MnP-encoding genes, npr transcript levels are repressed by low levels of Mn2+. In addition, we have investigated the effects on npr transcript levels of a number of other factors which are known to regulate MnP and LiP expression.

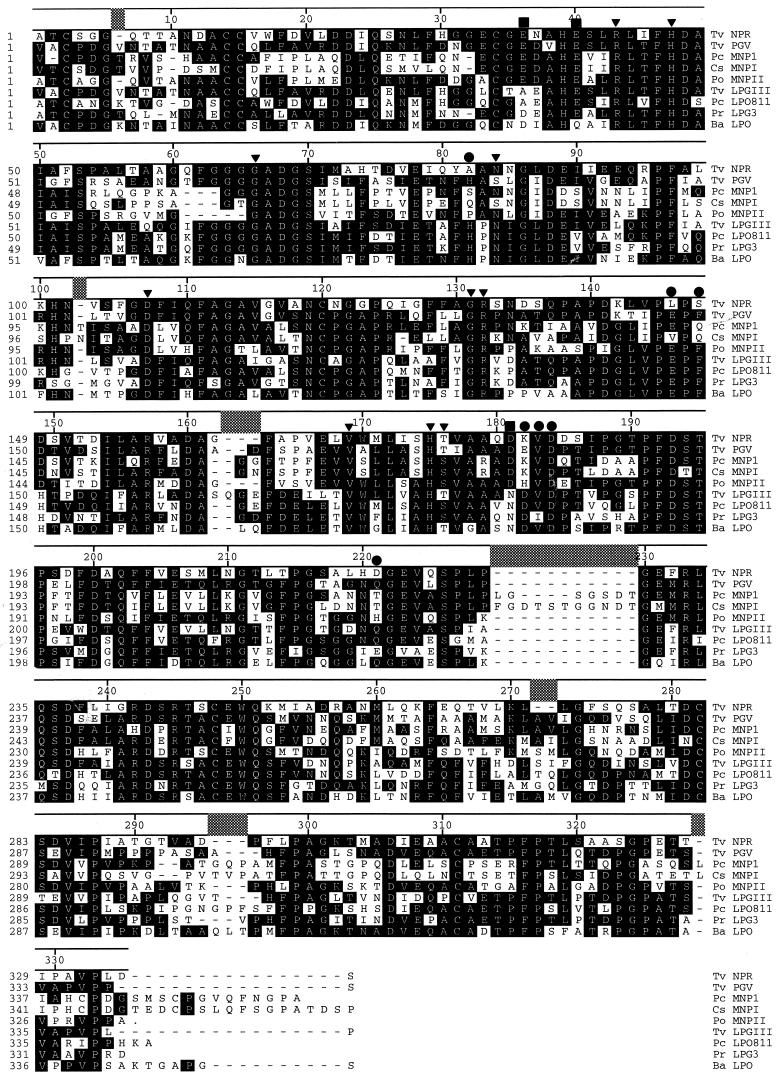

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the NPR amino acid sequence with various fungal manganese and lignin peroxidases. Areas of dark background indicate common amino acids. The positions of the amino acids involved in Mn2+ binding (19, 25, 39) are indicated with squares. The 10 invariant residues of all members of the plant peroxidase superfamily (41) are indicated with inverted triangles. The positions of the LiP residues suggested to interact with aromatic substrates are indicated by circles (33). The amino acid sequences were either experimentally determined or deduced from nucleotide sequences of T. versicolor (Tv NPR [this study] and Tv PGV [20]), P. chrysosporium manganese peroxidase (Pc MNP1) (34), Ceriporiopsis subvermispora manganese peroxidase (Cs MNPI) (28), P. ostreatus manganese peroxidase (Po MNPII) (4), T. versicolor lignin peroxidase (Tv LPGIII) (17), P. chrysosporium lignin peroxidase (Pc LPO811) (35), Phlebia radiata lignin peroxidase (Pr LPG3) (36), and B. adusta lignin peroxidase (Ba LPO) (3).

Cloning and characterization of the npr cDNA sequence.

A Lambda ZAP II T. versicolor CU1 cDNA library, constructed by Stratagene (Cambridge, United Kingdom) and containing 3.3 × 109 amplified recombinants per ml, was plated at a density of 5 × 104 PFU per 150-mm petri dish and hybridized overnight at 55°C with 32P-labelled MNP-1 from P. chrysosporium (34), as previously described (37). After hybridization, the membranes were washed once with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 20 min at 55°C and twice with 0.2× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 20 min at 55°C. Six putative positive clones were isolated, and one of these, npr, was chosen for sequencing and characterization. Sequencing was via the dideoxy chain termination method (38), with a Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit and AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), on a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) and an automated DNA sequencer (model 373 Stretch; Applied Biosystems). The sequencing strategy consisted of the initial use of M13 universal primers, followed by designing of primers by using the newly acquired sequences. Both strands were sequenced independently. Sequence data was assembled and processed with the DNASTAR (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) software package. The BLAST algorithm (1) was used to search DNA and protein databases for similarity. The CLUSTAL program was used for amino acid sequence alignment.

The npr nucleotide sequence is 1,362 bp long and contains an open reading frame of 1,089 bp which encodes a protein of 362 amino acids. The coding region G+C content is 66%, similar to that previously reported for T. versicolor LiP- and MnP-encoding exon regions (17). The predicted mature NPR translation product is shown in Fig. 1. Eight cysteine residues are present within the deduced NPR sequence, allowing four possible disulfide linkages to be formed. This would be consistent with evidence from X-ray crystallographic studies with LiP (33) from P. chrysosporium, which indicates an arrangement of four disulfide linkages of 1-3, 2-7, 4-5, and 6-8. Such linkages have also been observed in peroxidases from T. versicolor (27). However, this differs from MnP, which has a fifth disulfide bond believed to be required for the correct formation of the Mn2+ binding site (39).

A phylogenetic tree was constructed, based on the alignment of the npr-encoded amino acid sequence and amino acid sequences deduced for LiP and MnP from T. versicolor and P. chrysosporium (data not shown). This indicates that NPR is significantly distant at the amino acid level from both the MnP and LiP subfamilies within the plant peroxidase superfamily proposed by Welinder (40). It shows an identity of approximately 45 to 50% in amino acid sequence with both LiP and MnP sequences from T. versicolor and no more than 53.6% identity with any of the other sequences examined. In the MnP subfamily, NPR appears to be most closely related to PGV (20), a T. versicolor peroxidase which displays a number of novel features. Within these groups, NPR exhibits the greatest divergence from P. chrysosporium MnP sequences.

Analysis of npr transcript levels.

In order to determine the point of maximal npr expression, a time course experiment in which npr transcript levels were measured after 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 18 days of growth was conducted. An RT-PCR approach which included an internal control system standardizing both the RT and PCR processes was employed. Total RNA was prepared from mycelium samples, as previously described (7), with residual contaminating DNA being removed by digestion with DNase I. Total RNA was quantitated by both spectrophotometric and visual methods (37). RT reaction mixtures contained 1 μg of total RNA, random hexamer primers, and other reaction components previously described (8). In order to standardize each set of RT-PCR mixtures, a known amount (10 pg) of a control template was added to each RT reaction mixture. This control consisted of RNA transcripts generated from a genomic lignin peroxidase gene (lip) fragment with the Riboprobe in vitro transcription system (Promega). The DNA template used in this in vitro transcription reaction had been amplified from T. versicolor CU1 genomic DNA with the lip forward (5′-CGACGCIATCGCCATCTC-3′ [I represents inosine]) and reverse (5′-GAACGGCTCGGG[G/C]ACGAG-3′) primers previously described (8). This fragment contains two introns, yielding an RT-PCR product of 418 bp, and thus could be distinguished from a fragment representing lip mRNA which would, if present, be 304 bp in size. The RT reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and reactions were terminated by heating to 65°C for 10 min. PCR amplifications were carried out with forward (5′-TCATGGCCCACACCGACG-3′) and reverse (5′-GCGGTCGGCGATCATCTT-3′) primers designed to specifically amplify npr cDNA sequences and not those encoding either LiP or MnP. With these primers, the npr amplification product is 560 bp. For PCR amplification, a 2-μl volume from each RT reaction was mixed with 75 ng of each primer, 5 μl of 10× NH4Cl Taq buffer (Bioline, London, United Kingdom), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase. In addition, each reaction mixture contained 75 ng of both lip PCR primers (8) in order to amplify the control RT-PCR fragment in each case. For each experiment, the constant band intensities seen for the amplified product of this lip fragment (see Fig. 2 to 5, lower bands) indicated the uniformity of RT-PCR efficiency. Reaction volumes were adjusted to 50 μl with water. Amplification was performed in a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, Mass.) with 30 cycles of denaturation (1 min at 94°C), annealing (1 min at 56°C), and extension (1 min at 72°C). Ten-microliter aliquots of each reaction mixture were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels, and the product band intensities within each experiment were visually compared after ethidium bromide staining. Both the npr fragment and the lip control fragment were sequenced to confirm their identities.

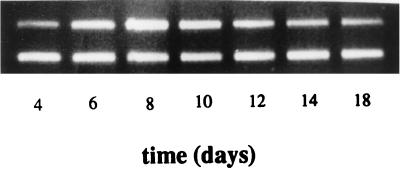

FIG. 2.

Time course of npr transcription in cultures of T. versicolor CU1. The higher-molecular-weight band (560 bp) represents the level of npr transcript present, and the lower band (418 bp) represents the lip fragment amplified as an internal control.

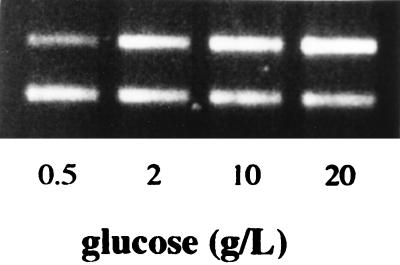

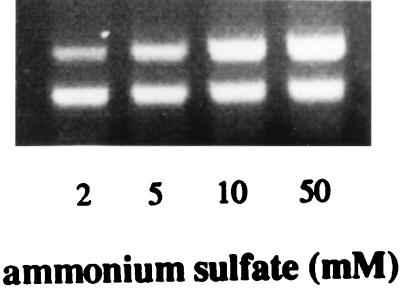

FIG. 5.

Effects of growth in the presence of various concentrations of carbon in the form of glucose on npr transcription levels. The higher-molecular-weight band (560 bp) represents the level of npr transcript present, and the lower band (418 bp) represents the lip fragment amplified as an internal control.

The time course experiment indicated the presence of npr transcripts after 4 days of growth, reaching a maximum after 8 days and then beginning to decrease. However, npr mRNA was still detected in 18-day-old cultures (Fig. 2). As the highest level of npr transcription was observed on day 8, for subsequent experiments, fungal mycelia from quadruplicate cultures were harvested, pooled, and analyzed for each datum point following 8 days of incubation.

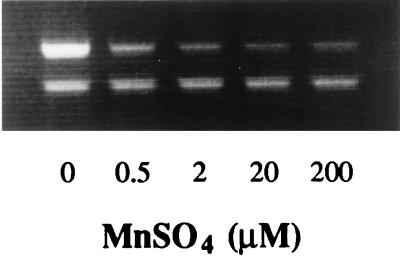

The effects of Mn2+ on npr transcript levels were investigated by adding MnSO4 at final concentrations of 0.5, 2, 20, and 200 μM to the growth medium. In order to remove trace levels of Mn2+ from the media used, all glassware was soaked overnight in 2 M nitric acid and then extensively rinsed with distilled deionized water. Mn2+ levels in media were measured by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (Pye Unicam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at a resonance line of 279.5 nm and in all cases were found to be lower than the detection limit of the instrument (0.018 μM). Supplementation of fungal cultures with low levels of Mn2+ had a repressive effect on npr transcript levels (Fig. 3). A high level of amplification product, representing npr mRNA, was observed when the medium contained no detectable Mn2+. However when Mn2+ at a concentration of 0.5 μM was added, a much reduced level of npr transcript was detected. A further decrease in the level of npr transcription occurred when the Mn2+ concentration was increased to 2 μM. Interestingly however, a low level of npr transcription was still detected at Mn2+ concentrations as high as 200 μM and even up to 500 μM (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effects of growth in the presence of various concentrations of Mn2+ on npr transcription levels. The higher-molecular-weight band (560 bp) represents the level of npr transcript present, and the lower band (418 bp) represents the lip fragment amplified as an internal control.

The possibility that expression of npr may be induced as a response to environmental stresses was investigated by subjecting 8-day-old cultures to a range of stresses before analysis. This was examined by adding either 2,5-xylidine (at a final concentration of 5, 20, 50, 200, or 500 μM) or ethanol (at a final concentration of 1, 2, 5, 10, or 15%) to 8-day-old cultures. For these experiments, cultures were harvested for analysis at 90 min after addition of the compounds. The effect of H2O2 addition (at a final concentration of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, or 5 mM) was determined by adding it to 8-day-old cultures for 80 min. For determination of a possible regulatory effect of heat shock, cultures were transferred from 26°C to water baths at either 37 or 45°C for a period of 120 min prior to harvesting of the mycelium. No effect on the level of npr transcription was observed as a response to either heat shock, oxidative stress in the form of H2O2, or chemical stress in the form of ethanol (data not shown). The presence of 2,5-xylidine, however, which previously has been demonstrated to induce laccase gene transcription in T. versicolor (7), was found to have a repressive effect on npr expression when present at concentrations as low as 5 μM (data not shown). This phenomenon may be due simply to the toxic effect of the compound on cellular metabolism.

Experiments were also conducted to determine the effect of nitrogen on npr transcript levels by culturing the fungus on basal medium (8) containing ammonium sulfate as the nitrogen source and no MnSO4. Expression of npr was found to be induced by nitrogen at the level of gene transcription (Fig. 4). As the concentration of nitrogen was increased from 2 mM (limiting nitrogen) to 5 mM (high nitrogen), a corresponding increase in npr transcript levels was observed. A similar effect was observed when the glucose concentration was observed when the glucose concentration was increased from 0.5 to 2 g per liter (Fig. 5). Further increases in the level of glucose in the medium had a less marked inducing effect.

FIG. 4.

Effects of growth in the presence of various concentrations of nitrogen on npr transcription levels. The higher-molecular-weight band (560 bp) represents the level of npr transcript present, and the lower band (418 bp) represents the lip fragment amplified as an internal control.

The deduced amino acid sequence of the NPR protein isolated here exhibits features characteristic of ligninolytic peroxidases from other strains of T. versicolor and other white rot fungal species. NPR also displays a high degree of amino acid sequence similarity, at and near its active site, with MnP, LiP, and a range of other peroxidases, i.e., the regions surrounding the so-called distal His (residue 47), believed to be involved in charge stabilization during reaction of the heme prosthetic group with H2O2, and proximal His (residue 175) residue, the proposed axial ligand of heme. In addition, an Arg (residue 43) also essential for activity (11) and a Leu (residue 44) near the distal His are well conserved in NPR and the various other MnP and LiP amino acid sequences. Furthermore, the deduced NPR amino acid sequence contains the 10 invariant residues of all members of the plant peroxidase superfamily (41) (Fig. 1).

Alignment of the npr DNA sequence (data not shown) or its deduced amino acid sequence with corresponding sequences for ligninolytic peroxidases indicated that NPR cannot be classified as either an LiP- or an MnP-type peroxidase. Instead, the product of npr expression may represent a more distinct class of peroxidase within the ligninolytic peroxidase family. The deduced NPR protein does, however, display some unique features which suggest a closer structural and functional relationship with MnP than with LiP. Firstly, the total Ser content of deduced NPR (26 residues) is consistent with the reported value for MnP (approximately 24 residues) rather than that for LiP (16 residues) (18). Johansson et al. (18) have previously reported this difference in the overall serine content in eight different LiP and MnP isozymes from T. versicolor. Secondly, a number of key residues in MnP, proposed to interact with its Mn2+ substrate (19, 39), are present in the deduced NPR sequence (Glu36, Glu40, and Asp181). In contrast, the LiP residues suggested to interact with aromatic substrates of the enzyme (33) are not present in the NPR sequence (Fig. 1). This suggests that NPR may be evolutionarily, or even functionally, more closely related to MnP. Although possibly related to MnP at the functional level, NPR expression contrasts markedly with regard to its regulation by Mn2+. Mn2+ has been demonstrated to directly induce mnp transcription in P. chrysosporium (5, 12, 13), and this is thought to be mediated via a metal response element in the mnp promoter region (15). In the case of npr, however, Mn2+ appears to have a similar but opposite effect whereby the presence of low concentrations of Mn2+ have a repressive effect on transcription.

A number of studies have reported that some level of mnp transcription occurs in P. chrysosporium in the absence of Mn2+ (5) and in the presence or absence of some other mnp-inducing factor (6, 26). Furthermore, Moreira and coworkers (31) reported that MnP was the predominant oxidative enzyme produced by Bjerkandera sp. strain BOS55, even under Mn2+-deficient conditions. This group has recently reported the characterization of an MnP-LiP hybrid enzyme produced by this strain in the absence of manganese (30).

Further contrasts also exist between the regulation of npr and mnp. Transcription of mnp can be induced as a heat shock-like response to chemical stress by ethanol, oxidative stress by H2O2 (26), or heat shock itself (6) in P. chrysosporium. However, in our study such responses were not detected, indicating further the heterogeneity between mnp and npr with respect to their regulation. Increased nitrogen and carbon levels result in increased npr transcripts in T. versicolor CU1. In P. chrysosporium, both MnP and LiP are produced during secondary metabolism only under conditions of carbon or nitrogen limitation (15), and various isozymes have been shown to be differentially regulated by these nutrients (13, 32). In contrast, a number of strains of Bjerkandera adusta in which nitrogen appears to have a stimulatory effect on both LiP and MnP production have been isolated (23, 29). MnP induction by high nitrogen levels has also been reported in Pleurotus ostreatus (23).

In conclusion, the translation product of npr cannot be clearly classified as an LiP- or MnP-type peroxidase on the basis of DNA or deduced amino acid sequence. An apparent biological contradiction exists in that, although it contains the residues proposed to function as Mn2+-binding ligands in MnP, transcription of npr is repressed by the presence of Mn2+. However, it is possible that these residues are involved in the binding of alternative substrates, such as aromatic amines. Furthermore, the repression of npr transcription by Mn2+ makes it difficult to speculate on what the physiological role of its putative translation product might be. One possibility is that it is expressed in the later stages of lignin degradation, when much of the Mn2+ present in wood has been oxidized by MnP to MnO2 and functions in the further oxidation of lignin subunits. Future work, therefore, will focus on the purification of this putative NPR protein, in either the native form or a recombinant form, in order to characterize it with respect to its substrate range and catalytic mechanism compared to MnP and LiP.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the npr gene has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF008585.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the European Union FAIR Programme Oxidative Enzymes for the Pulp and Paper Industry (OXEPI) CT95-0805.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald F S. Lignin peroxidase activity is not important in biological bleaching and delignification of unbleached kraft pulp by Trametes versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;58:3101–3109. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.3101-3109.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asada Y, Kimura Y, Oka T, Kuwahara M. Characterization of a cDNA and gene encoding a lignin peroxidase from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Bjerkandera adusta. In: Kuwahara M, Shimada M, editors. Biotechnology in the pulp and paper industry. Tokyo, Japan: Uni Publishers; 1992. pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asada Y, Watanabe A, Irie T, Nakayama T, Kuwahara M. Structures of genomic and complementary DNAs coding for Pleurotus ostreatus manganese (II) peroxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1251:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown J A, Alic M, Gold M H. Manganese peroxidase gene transcription in Phanerochaete chrysosporium: activation by manganese. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4101–4106. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4101-4106.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown J A, Li D, Alic M, Gold M H. Heat shock induction of manganese peroxidase gene transcription in Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4295–4299. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4295-4299.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins P J, Dobson A D W. Regulation of laccase gene transcription in Trametes versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3444–3450. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3444-3450.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins P J, Field J A, Teunissen P, Dobson A D W. Stabilization of lignin peroxidases in white-rot fungi by tryptophan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2543–2548. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2543-2548.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cullen D. Recent advances on the molecular genetics of ligninolytic fungi. J Biotechnol. 1997;53:273–289. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)01684-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson K-E, L, Blanchette R A, Ander P. Biochemistry of lignin degradation. In: Eriksson K-E L, Blanchette R A, Ander P, editors. Microbial and enzymatic degradation of wood and wood components. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 225–333. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finzel B C, Poulos T L, Kraut J. Crystal structure of yeast cytochrome c peroxidase refined at 1.7 A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1987;259:13027–13036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gettemy J M, Li D, Alic M, Gold M H. Truncated gene reporter system for studying the regulation of manganese peroxidase expression. Curr Genet. 1997;3:519–524. doi: 10.1007/s002940050239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gettemy J M, Ma B, Alic M, Gold M H. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis of the regulation of the manganese peroxidase gene family. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:569–574. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.569-574.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glenn J K, Akileswaren L, Gold M H. Mn(II) oxidation is the principal function of the extracellular Mn-peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;251:688–696. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold M H, Alic M. Molecular biology of the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:605–622. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.605-622.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson T, Nyman P O. Isozymes of lignin peroxidase and manganese (II) peroxidase from the white-rot basidiomycete Trametes versicolor. I. Isolation of enzyme forms and characterization of physical and catalytic properties. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:49–56. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson T, Nyman P O. A cluster of genes encoding major isozymes of lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase from the white-rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Gene. 1996;170:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00846-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson T, Welinder K G, Nyman P O. Isozymes of lignin peroxidase and manganese (II) peroxidase from the white-rot basidiomycete Trametes versicolor. II. Partial sequences, peptide maps and amino acid and carbohydrate compositions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:57–62. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson F, Loew G H, Du P. Prediction of Mn2+ binding site of manganese peroxidase from homology modelling. In: Welinder K G, Rasmussen S K, Penel C, Greppin H, editors. Plant peroxidases: biochemistry and physiology. Geneva, Switzerland: University of Copenhagen and Unversity of Geneva; 1993. pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jönsson L, Becker H G, Nyman P O. A novel type of peroxidase gene from the white-rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1207:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jönsson L, Nyman P O. Characterization of lignin peroxidase gene from the white-rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Biochemie. 1992;74:177–183. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90043-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jönsson L, Nyman P O. Tandem lignin peroxidase genes of the white-rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:408–412. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaal E E J, Field J A, Joyce T W. Increasing ligninolytic enzyme activities in several white-rot basidiomycetes by nitrogen-sufficient media. Bioresour Technol. 1995;53:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kersten P J, Tien M, Kalyanamaran B, Kirk T K. the ligninase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium generates cation radicals from methoxybenzenes. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2609–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishi K, Kusters-van Someren M, Mayfield M B, Sun J, Loehr T M, Gold M H. Characterization of manganese (II) binding site mutants of manganese peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8986–8994. doi: 10.1021/bi960679c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D, Alic M, Brown J A, Gold M H. Regulation of manganese peroxidase gene transcription by hydrogen peroxide, chemical stress, and molecular oxygen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:341–345. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.341-345.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limongi P, Kjalke M, Vend J, Tams J W, Johansson T, Welinder K G. Disulphide bonds and glycosylation in fungal peroxidases. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:270–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lobos S, Lorondo L, Salas L, Karahanian E, Vicuna R. Cloning and molecular analysis of a cDNA encoding a manganese peroxidase isozyme from the lignin degrading basidiomycete Ceriporiopsis subvermispora. Gene. 1998;206:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mester T, Peña M, Field J A. Nutrient regulation of extracellular peroxidases in the white-rot fungus Bjerkandera sp. strain BOS55. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;44:778–784. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mester T, Field J A. Characterization of a novel manganese peroxidase-lignin peroxidase hybrid isozyme produced by Bjerkandera sp. strain BOS55 in the absence of manganese. J Biol Chem. 1988;273:15412–15417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreira M T, Feijoo G, Sierra-Alvarez R, Lema J, Field J A. Manganese is not required for biobleaching of oxygen-delignified kraft pulp by the white rot fungus Bjerkandera sp. strain BOS55. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1749–1755. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1749-1755.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pease E A, Tien M. Heterogeneity and regulation of manganese peroxidases from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3532–3540. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3532-3540.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulos T L, Edwards S, Wariishi H, Gold M H. Crystallographic refinement of lignin peroxidase at 2A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4429–4440. doi: 10.2210/pdb1lga/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pribnow D, Mayfield M B, Nipper V J, Brown J A, Gold M H. Characterization of a cDNA encoding manganese peroxidase from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5036–5040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiser J, Walther I S, Fraefel C, Fiecther A. Methods to investigate the expression of lignin peroxidase genes by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2897–2903. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2897-2903.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saloheimo M, Barajas V, Niko-Paavola M-L, Knowles J K C. A lignin-peroxidase encoding cDNA from the white-rot fungus Phlebia radiata: characterization and expression in Trichoderma reesei. Gene. 1989;85:343–351. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundaramoorthy M, Kishi K, Gold M H, Poulos T L. The crystal structure of manganese peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium at 2.06-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32759–32767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welinder K G. Superfamily of plant, fungal and bacterial peroxidases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1992;2:383–393. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welinder K G, Gajhede M. Structure and evolution of peroxidases. In: Welinder K G, Rasmussen S K, Penel C, Greppin H, editors. Plant peroxidases: biochemistry and physiology. Geneva, Switzerland: University of Copenhagen and University of Geneva; 1993. pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]