Abstract

Background:

Cabozantinib, a multiple kinase inhibitor, was recently approved for patients with previously treated unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC). We investigated the real-world safety and efficacy profiles of cabozantinib.

Methods:

This multicenter retrospective study included 110 patients with uHCC who received cabozantinib after progression on other systemic treatments between October 2019 and May 2021.

Results:

The median age was 58 (range, 20–77) years, and 98 (89.1%) were male. Prior to cabozantinib, all patients were treated with other systemic therapies: sorafenib (n = 104, 94.5%) and regorafenib (n = 91, 82.7%) were the most commonly used agents. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were previously used in 93 patients (84.5%). Cabozantinib was used beyond the third-line of therapy in most patients (n = 90, 81.8%). With a median follow-up duration of 11.9 months [95% confidence interval (CI), 10.8–17.2], the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.7 months (95% CI, 3.1–4.9), and the median overall survival (OS) was 7.5 months (95% CI, 5.5–9.5). The disease control rate and overall response rate (ORR) were 66.3% and 3.6%, respectively. In the Child–Pugh A cohort (n = 88), the ORR was 4.5%, and the median PFS and OS were 4.3 months (95% CI, 3.6–5.8) and 9.0 months (95% CI, 7.5–11.7), respectively.

Conclusion:

Cabozantinib showed consistent efficacy outcomes with a prior phase III trial, although in this study, it was used as later-line therapy for patients who were refractory to multiple systemic treatments, including immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Keywords: cabozantinib, hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. 1 For patients with advanced HCC, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Although sorafenib was the only agent approved for unresectable HCC (uHCC), 2 multiple agents have recently acquired approval for the management of patients with uHCC based on positive results in the prospective phase II and III trials.3–8 While sorafenib and lenvatinib have been the standard first-line therapy,2,3 the landscape of first-line therapy for uHCC is rapidly changing as atezolizumab–bevacizumab and tremelimumab–durvalumab demonstrated significant improvements in overall survival (OS) compared to sorafenib in the phase III IMbrave150 and HIMALAYA trials.8,9 Atezolizumab plus cabozantinib showed significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared to sorafenib in the phase III COSMIC-312 trial, but it failed to demonstrate its superiority in terms of OS. 10

As salvage therapies, regorafenib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab have demonstrated survival benefits for patients who progressed on first-line sorafenib in randomized phase III trials.4,5,11 Despite a lack of positive data in the phase III trials, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and an ipilimumab–nivolumab combination, were approved in some countries for patients who progressed on sorafenib based on the promising results in the phase II trials.6,12,13

Cabozantinib is an oral multiple kinase inhibitor (MKI) targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) 1, 2, and 3, MET, and the TAM kinase family (TYRO-3, AXL, and MER). 14 In the CELESTIAL trial, cabozantinib showed significant improvement in terms of a median PFS of 3.3 months and a median OS of 2.2 months compared to placebo for patients with uHCC who are intolerant of or progressed on sorafenib. 5 In contrast to ramucirumab, which has only been approved for patients with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels ⩾400 ng/ml 11 and the pivotal trial for regorafenib 4 was limited to sorafenib-tolerant patients, cabozantinib demonstrated a clinical benefit in a more general patient population. Cabozantinib was investigated as second- or third-line therapy in the CELESTIAL trial, while other agents were tested as only second-line therapy. 5

Given that the characteristics of patients with uHCC in daily practice are often different from those in the prospective clinical trials in terms of liver function or tumor burden, and the rapidly changing landscape of the management of uHCC, particularly the widespread incorporation of ICIs in first- or later-line therapy, 15 there is an unmet need for real-world efficacy and safety assessments of cabozantinib. We, therefore, performed a multicenter retrospective analysis of cabozantinib as subsequent therapy after progression on any prior systemic therapy for patients with uHCC.

Patients and methods

This was a multicenter, retrospective, open-label, non-comparative observational study. Patient data were retrospectively collected and reviewed using electronic medical records from three tertiary referral hospitals in Korea. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each participating center. Informed consent from the patients was waived by the IRB because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Between October 2019 and May 2021, a total of 110 uHCC patients who received cabozantinib as a subsequent therapy after failure of other systemic therapy were identified. The dosing schedule and modification per adverse events (AEs) of cabozantinib were based on the protocol of the CELESTIAL trial in general. 5 However, doses could be adjusted at the discretion of the attending physicians with the consideration of toxicities on prior therapy or comorbidities. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, chemistry and coagulation battery, and a physical examination, were performed every 4 weeks. Tumor response evaluation was performed using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans every 8–12 weeks and was graded per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Liver functions were classified according to the Child–Pugh score and albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) grade as previously described.16,17

PFS was defined as the time from the initiation of cabozantinib to the date of disease progression determined by the RECIST v1.1 criteria or death. OS was defined as the time interval between the date of the initiation of cabozantinib and the date of death from any cause. The safety profile was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE), version 5.

The survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses of PFS and OS were performed using log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards models. In the multivariate analysis, variables with a potential relationship (p < 0.1) in the univariate analyses were included. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 58 (range, 20–77) years, and 98 (89.1%) were male. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (n = 99, 90.0%) was the most frequent etiology of HCC. Most patients (n = 88, 80.0%) had Child–Pugh A, whereas 22 (20.0%) had Child–Pugh B liver function at the time of initiating cabozantinib. All patients had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) C stage; 51 (46.4%) patients had macrovascular invasion, and 104 (94.5%) had extrahepatic metastasis.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| N = 110 (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 (20–77) |

| Male gender | 98 (89.1) |

| Etiology | |

| HBV | 99 (90.0) |

| HCV | 2 (1.8) |

| Alcohol | 4 (3.6) |

| Unknown | 5 (4.5) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1 | 96 (87.3) |

| 2 | 14 (12.7) |

| BCLC stage | |

| C | 110 (100.0) |

| Child–Pugh class | |

| A | 88 (80.0) |

| B | 22 (20.0) |

| ALBI grade | |

| 1 | 24 (21.8) |

| 2 | 69 (62.7) |

| 3 | 17 (15.5) |

| Macrovascular invasion | |

| Yes | 51 (46.4) |

| No | 59 (53.6) |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | |

| Yes | 104 (94.5) |

| No | 6 (5.5) |

| AFP, median (range), ng/ml | 475.6 (1.6–503,168) |

| <400 | 52 (47.3) |

| ⩾400 | 54 (49.1) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.6) |

| Previous systemic treatment lines | |

| 1 | 2 (1.8) |

| 2 | 18 (16.4) |

| ⩾3 | 90 (81.8) |

| Previous treatments | |

| Liver transplantation | 9 (8.2) |

| Surgical resection | 47 (42.7) |

| TACE | 85 (77.3) |

| RFA | 9 (8.2) |

| SBRT | 46 (41.8) |

| Previous systemic treatment | |

| Sorafenib | 104 (94.5) |

| Lenvatinib | 26 (23.6) |

| Regorafenib | 91 (82.7) |

| Ramucirumab | 2 (1.8) |

| Nivolumab | 82 (74.5) |

| Atezolizumab + bevacizumab | 10 (9.1) |

| Durvalumab | 2 (1.8) |

| Pembrolizumab | 3 (2.7) |

| Doxorubicin + cisplatin | 3 (2.7) |

ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PS, performance status; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range).

All patients received other types of systemic therapy prior to the administration of cabozantinib. Most patients (n = 90, 81.8%) received cabozantinib as the fourth or greater line of therapy followed by third line (n = 18, 16.4%). Sorafenib was the most frequently used agent prior to cabozantinib (n = 104, 94.5%), followed by regorafenib (n = 91, 82.7%); the median time to progression (TTP) on prior sorafenib and regorafenib was 2.7 (range, 0.5–28.9) months and 3.4 (range, 0.9–23.0) months, respectively. ICIs were previously given to 93 patients [84.5%; nivolumab (n = 82, 74.5%), atezolizumab–bevacizumab (n = 10, 9.1%), pembrolizumab (n = 3, 2.7%), and durvalumab (n = 2, 1.8%)]. A sorafenib–regorafenib sequence was previously used in 79 patients (71.8%). The starting dose of cabozantinib was 60 and 40 mg daily in 65 (59.1%) and 43 (39.1%) patients, respectively. The remaining two (1.8%) patients received 60 mg every other day at the discretion of the attending physician with the consideration of financial constraints as the cost of cabozantinib was not reimbursed. In patients with Child–Pugh A and B liver function, a starting dose of 60 mg daily was used in 57 (64.8%) and 8 patients (36.4%), respectively.

Efficacy outcomes

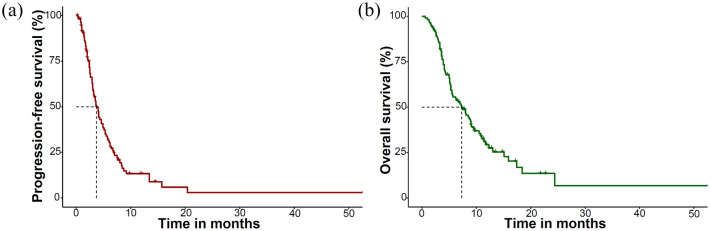

With a median follow-up of 11.9 months [95% confidence interval (CI), 10.8–17.2], the median PFS was 3.7 months (95% CI, 3.1–4.9) and the median OS was 7.5 months (95% CI, 5.5–9.5) among all patients (Figure 1). The overall response rate (ORR) was 3.6%, with 4 (3.6%), 69 (62.7%), and 20 (18.2%) patients showing partial responses, stable disease, and progressive disease, respectively, and a response evaluation was not available for 17 patients (15.5%). In the Child–Pugh A cohort (n = 88), the ORR was 4.5%, and the median PFS and OS were 4.3 months (95% CI, 3.6–5.8) and 9.0 months (95% CI, 7.5–11.7), respectively (Table 2). Among the 79 patients who received the sorafenib–regorafenib sequence prior to cabozantinib, the median OS from the start of first-line sorafenib was 28.3 months (95% CI, 26.3–33.1) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the survival outcomes of the study cohort: (a) PFS and (b) OS.

Table 2.

Efficacy parameters of cabozantinib.

| Response according to RECIST version 1.1 | Overall (n = 110) | Child–Pugh A | Child–Pugh B (n = 22) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 88) | Second and third line (n = 16) | Fourth line (n = 72) | |||

| Complete response, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Partial response, n (%) | 4 (3.6) | 4 (4.5) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (4.2) | 0 (0) |

| Stable disease, n (%) | 69 (62.7) | 59 (67.0) | 11 (68.8) | 48 (66.7) | 10 (45.5) |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | 20 (18.2) | 13 (14.8) | 2 (12.5) | 11 (15.3) | 7 (31.8) |

| Not evaluable, n (%) | 17 (15.5) | 12 (13.6) | 2 (12.5) | 10 (13.9) | 5 (22.7) |

| ORR, % | 3.6 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 0 |

| Disease control rate, % | 66.3 | 71.5 | 75.1 | 70.9 | 45.5 |

| Median OS, month (95% CI) | 7.5 (5.5–9.5) | 9.0 (7.5–11.7) | 24.4 (11.7–NR) | 8.5 (7.0–10.8) | 3.8 (2.9–5.0) |

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 3.7 (3.1–4.9) | 4.3 (3.6–5.8) | 5.3 (4.0–NR) | 4.1 (3.1–6) | 2.2 (1.4–3.3) |

CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

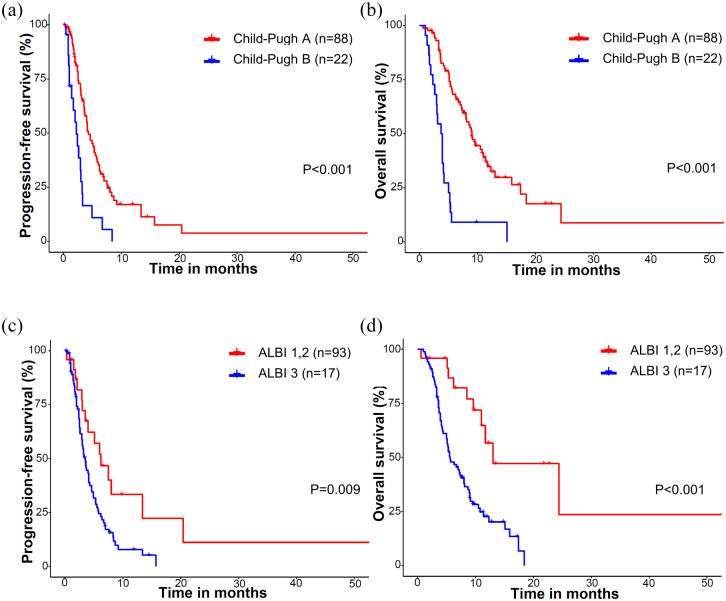

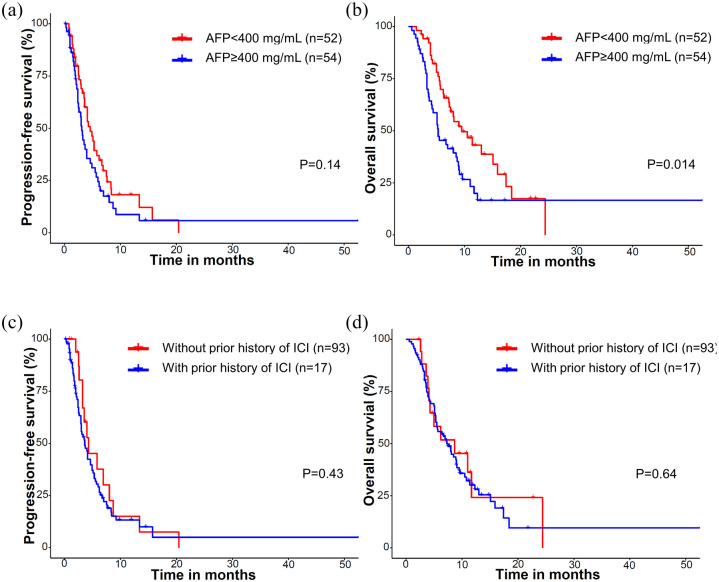

Because of the heterogeneous nature of the population included in this study, the efficacy outcomes were analyzed after stratification according to the treatment line of cabozantinib and the Child–Pugh class when cabozantinib was initiated (Table 2). Compared with patients with Child–Pugh A, patients with Child–Pugh B had worse PFS (median 4.3 versus 2.2 months, p < 0.001), OS (9.0 versus 3.8 months, p < 0.001), and lower disease control rates (DCRs; 71.5% versus 45.5%, p = 0.021). Patients with ALBI grade 3 showed significantly worse PFS (3.5 versus 6.2 months, p = 0.009) and OS (5.6 versus 13 months, p < 0.001) compared to patients of ALBI grade 1 or 2 (Figure 2). Patients with AFP levels ⩾ 400 ng/ml showed significantly worse OS (5.3 versus 9.5 months, p = 0.014), while there was a trend toward worse PFS (3.1 versus 4.6 months, p = 0.14). Prior administration of ICIs was not associated with PFS (p = 0.43) or OS (p = 0.64) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Survival outcomes according to the Child–Pugh score and ALBI grade: (a) PFS and (b) OS according to the Child–Pugh score. (c) PFS and (d) OS according to ALBI grade.

Figure 3.

Survival outcomes according to the AFP level and prior exposure to ICIs: (a) PFS and (b) OS according to AFP (⩾400 and <400 ng/ml). (c) PFS and (d) OS according to prior exposure to ICIs.

Multivariate analysis revealed that Child–Pugh B was an independent negative prognostic factor for both PFS [versus Child–Pugh A, hazard ratio (HR), 3.38 (95% CI, 1.50–4.60); p = 0.001] and OS [HR, 4.95 (95% CI, 2.81–10.2); p < 0.001] (Table 3). There were marginal significances for the association between OS and baseline serum AFP levels [⩾400 versus <400 ng/ml; HR, 1.89 (0.98–2.74); p = 0.059] and TTP on prior sorafenib [⩾median versus <median; HR, 0.61 (0.37–1.04); p = 0.069]. Multivariate analysis including ALBI grade was conducted separately, considering the potential high collinearity between the ALBI score and the Child–Pugh score (Supplementary Table 1). ALBI grade 3 was significantly associated with a worse PFS [HR, 2.07 (95% CI, 1.13–3.79); p = 0.018] and OS [HR, 2.85 (95% CI, 1.43–5.70); p = 0.003] compared to ALBI grade 1 or 2. In this analysis set, baseline AFP level was significantly associated with OS [⩾400 versus <400 ng/ml; HR, 1.68 (1.02–2.76); p = 0.042].

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses for PFS and OS.

| Variables | PFS | OS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age (⩾60 versus <60 years) | 0.89 (0.58–1.38) | 0.606 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | 0.341 | ||||

| Sex (Male versus female) | 0.89 (0.41–1.94) | 0.766 | 0.68 (0.30–1.58) | 0.373 | ||||

| Etiology (HBV versus others) | 1.16 (0.58–2.33) | 0.678 | 1.80 (0.77–4.20) | 0.177 | ||||

| Child–Pugh class (B versus A) | 2.84 (1.67–4.81) | <0.001 | 3.38 (1.50–4.60) | 0.001 | 4.10 (2.40–6.95) | <0.001 | 4.95 (2.81–10.2) | <0.001 |

| Presence of macrovascular invasion (Yes versus no) | 1.48 (0.96–2.30) | 0.076 | 0.80 (0.76–1.92) | 0.421 | 2.03 (1.29–3.21) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.63–1.97) | 0.715 |

| Baseline serum AFP levels (⩾400 ng/ml versus <400 µg/mL) | 1.39 (0.90–2.15) | 0.142 | 2.43 (1.12–2.85) | 0.015 | 1.89 (0.98–2.74) | 0.059 | ||

| Presence of prior history of ICI (Yes versus no) | 1.26 (0.71–2.25) | 0.431 | 1.16 (0.62–2.16) | 0.642 | ||||

| TTP of sorafenib (⩾median versus <median) | 0.95 (0.60–1.49) | 0.816 | 0.53 (0.33–0.84) | 0.007 | 0.61 (0.37–1.04) | 0.069 | ||

| Treatment lines (>3 versus ⩽3) | 1.35 (0.79–2.31) | 0.271 | 2.12 (1.05–4.27) | 0.035 | 1.23 (0.55–2.95) | 0.574 | ||

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HR, hazard ratio; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TTP, time to progression.

Safety outcomes

The AEs associated with cabozantinib are summarized in Table 4. Any grade AEs were noted in 83 (75.5%) patients, while grade 3–4 AEs were present in 18 (16.4%) patients. The most common toxicity was hand-foot skin reaction; any grade in 35 patients (31.8%) and grade 3–4 in 5 patients (4.5%). Thrombocytopenia (n = 28, 25.5%), diarrhea (n = 23, 20.9%), and anorexia (n = 18, 16.4%) were also frequently reported toxicities. The dose of cabozantinib was reduced in 18 (16.4%) patients because of the toxicities. Hand-foot skin reaction (n = 5, 4.5%) and thrombocytopenia (n = 5, 4.5%) were the most common cause of dose reduction, followed by stomatitis (n = 2, 1.8%), fatigue (n = 2, 1.8%), nausea (n = 2, 1.8%), diarrhea (n = 1, 0.9%), and elevated aspartate aminotransferase (n = 1, 0.9%). Compared to patients with Child–Pugh A, an increased bilirubin level was more frequently noted in patients with Child–Pugh B (2.3% versus 13.6%, p = 0.054 for any grade and 0% versus 9.1%, p = 0.039 for grade 3–4).

Table 4.

AEs.

| NCI-CTCAE v5 | All (n = 110) | Child–Pugh A (n = 88) | Child–Pugh B (n = 22) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |

| Any AEs | 83 (75.5) | 18 (16.4) | 67 (76.1) | 13 (14.8) | 16 (72.7) | 5 (22.7) | 0.466 | 0.272 |

| Hand-foot skin reaction | 35 (31.8) | 5 (4.5) | 31 (35.2) | 4 (4.5) | 4 (13.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0.098 | 0.739 |

| Anorexia | 18 (16.4) | 1 (0.9) | 15 (17.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 0.492 | 0.800 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (4.5) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) | 0.261 | 0.492 |

| Diarrhea | 23 (20.9) | 3 (2.7) | 18 (20.5) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (22.7) | 1 (4.5) | 0.509 | 0.492 |

| Hypertension | 17 (19.8) | 4 (3.6) | 12 (13.6) | 3 (3.4) | 5 (22.7) | 1 (4.5) | 0.228 | 0.596 |

| Fatigue | 5 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.261 | NE |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 5 (2.7) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (9.1) | 0.054 | 0.039 |

| Elevated AST/ALT | 22 (20) | 1 (0.9) | 16 (18.2) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 0.250 | 0.800 |

| Anemia | 14 (12.7) | 2 (1.8) | 12 (13.6) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.5) | 0.437 | 0.361 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 28 (25.5) | 4 (3.6) | 21 (23.9) | 3 (3.4) | 7 (31.8) | 1 (4.5) | 0.304 | 0.596 |

| Neutropenia | 6 (5.5) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (4.5) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.345 | 0.800 |

| Skin rash | 4 (3.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) | 0.596 | 0.200 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NCI-CTCAE, National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; NE, not evaluable.

Discussion

This multicenter retrospective study, which included uHCC patients who were refractory to at least one prior systemic chemotherapy, showed that the efficacy outcomes of cabozantinib were consistent with the results of the CELESTIAL trial, even though the current study included a broader patient population. 5 The median PFS and OS with cabozantinib were 3.7 and 7.5 months, respectively, and the ORR per RECIST v1.1 was 3.6%. Our findings were also in line with the results of recent European multicenter retrospective studies (median PFS, 3.2–5.1 months; and median OS, 6.8–12.1 months).18,19

In this study, cabozantinib was administered to heavily pretreated patients, as 81.8% of the study population received cabozantinib as the fourth or greater line of therapy and 20.0% of the patients had Child–Pugh B liver function. Cabozantinib was investigated as second- or third-line therapy for Child–Pugh A patients after failure on first-line sorafenib in the pivotal CELESTIAL trial. 5 In the previous real-life studies, cabozantinib was mainly used as third-line therapy (79.1% of 96 patients) in the Italian analysis (all patients were Child–Pugh A), and 20.4% of 88 patients in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany received cabozantinib as fourth or greater lines of therapy (25% of patients were Child–Pugh B).18,19 Consistent efficacy outcomes even in the later-line setting in the current analysis suggest that cabozantinib may maintain its clinical benefit even in heavily pretreated HCC patients and reinforce the importance of sequential treatments in patients with advanced HCC.

The current study showed that patients with Child–Pugh B and ALBI grade 3 were significantly associated with a worse OS with cabozantinib in the multivariate analyses. Considering the potential deterioration of liver function related to tumor progression, and the risk of mortality from liver decompensation, Child–Pugh, and ALBI grades, indicators of liver function were the significant prognostic factors in patients with advanced HCC treated with targeted agents including cabozantinib, sorafenib, lenvatinib, regorafenib, and ramucirumab.5,7,20–23 Lower starting doses in Child–Pugh B patients could also be associated with worse DCR and PFS compared to Child–Pugh A patients in the current study. Given the poor clinical outcomes and increased frequency of AEs in patients with poor liver function, the use of cabozantinib should be decided based on shared decision-making with consideration of the potential clinical benefits and risks for each individual patient. In addition, high baseline AFP levels ⩾400 mg/ml were associated with a worse OS in our patient population. This is in line with the results of prior prospective and real-world studies of cabozantinib, sorafenib, and regorafenib, which have all identified high serum AFP levels as a negative prognostic factor.4,24–28

As cabozantinib, regorafenib, and ramucirumab have only been investigated among patients previously treated with sorafenib, and there is no head-to-head comparison among these agents, selection of the appropriate drug for each individual patient is a key issue for the management of patients who failed on first-line sorafenib. Recent post hoc analysis studies, which used data from the pivotal trials of cabozantinib, 5 regorafenib, 4 and ramucirumab, 7 showed that cabozantinib was associated with a prolonged median PFS compared with ramucirumab in patients with AFP ⩾400 ng/ml (median 5.5 versus 2.8 months, p = 0.016) 29 and regorafenib in second-line treatment (median 5.6 versus 3.1 months, p < 0.001). 30 In addition, while a previous retrospective study of 440 patients showed that the efficacy of regorafenib was poor in patients with a shorter TTP on prior sorafenib, 31 the efficacy of cabozantinib was not significantly associated with TTP on prior sorafenib in the current study. Recent multinational retrospective analysis using matching-adjusted indirect comparison analysis also suggested that cabozantinib may provide a better OS than regorafenib in patients with early progression on prior sorafenib. 32 This may suggest that cabozantinib could be considered as a priority option, particularly for patients who progressed rapidly with sorafenib. In addition, as there is no established biomarker for the selection of therapeutic agents in HCC except AFP for ramucirumab, further efforts are required to define additional specific biomarkers for the prediction of each agent’s efficacy or toxicity. 33

A combination of atezolizumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, and bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, is the new standard first-line therapy based on the results of the pivotal IMbrave 150 trial, which demonstrated significantly improved ORR, PFS, and OS compared to sorafenib.8,34 Recently, the HIMALAYA trial demonstrated that a priming dose of tremelimumab and a regular dose of durvalumab was superior to sorafenib in terms of OS, and this regimen will become one of the standard first-line regimens. 9 When the CELESTIAL trial was conducted, ICIs were not available in daily practice for the management of unresectable HCC, and the clinical outcomes of cabozantinib in patients previously treated with ICIs have not been sufficiently demonstrated, although a post hoc analysis of the CELESTIAL trial showed that the outcomes of 14 patients previously treated with ICIs prior to cabozantinib were similar to the other patients. 35 In our study, ICIs were previously given to 93 patients (84.5%) and there was no significant impact of prior exposure to ICIs on the clinical outcomes of cabozantinib, implying that cabozantinib might provide consistent efficacy after progression on an atezolizumab–bevacizumab combination. In future studies, the clinical relevance of cabozantinib should be further investigated among patients after failure of these new combination treatments. Currently, a multinational prospective trial is ongoing to assess the efficacy and safety of cabozantinib after progression on ICIs, including atezolizumab–bevacizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04588051).

The safety profiles of cabozantinib in this study were in line with the results of the CELESTIAL trial and previous retrospective studies of uHCC patients. 5 Most AEs were of grade 1 or 2, although there might be underestimation of the toxicity profile considering the retrospective nature of the current study. The toxicities noted in this study were mostly well manageable with appropriate supportive care, which may lead to improved treatment outcomes. 36 Although the overall incidence of AEs was comparable between Child–Pugh A and Child–Pugh B patients, grade 3–4 increased blood bilirubin was more frequently observed in Child–Pugh B patients, and this indicates that close monitoring of AEs is warranted for Child–Pugh B patients during the administration of cabozantinib.

This study has limitations, the most prominent of which is its retrospective design since this introduces unintentional biases. Although our study was based on multiple tertiary referral institutions, this study included only Korean patients and the study population was relatively small. This may limit the interpretation and generalizability of our data. Nevertheless, given the limited reports on clinical outcomes of cabozantinib treatment in the real world and among patients who progressed on prior ICIs, our results may be helpful for the management of uHCC and can be used to guide clinical decisions.

Conclusion

In this real-world analysis of Korean patients with uHCC, cabozantinib showed consistent efficacy and safety outcomes compared to the pivotal phase III CELESTIAL trial. Further investigations into the role of cabozantinib after failure of the new standard first-line treatment, atezolizumab–bevacizumab, are required.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tam-10.1177_17588359221097934 for Real-world efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis by Yeong Hak Bang, Choong-kun Lee, Changhoon Yoo, Hong Jae Chon, Moonki Hong, Beodeul Kang, Hyung-Don Kim, Sook Ryun Park, Won-Mook Choi, Jonggi Choi, Danbi Lee, Ju Hyun Shim, Kang Mo Kim, Young-Suk Lim, Han Chu Lee, Min-Hee Ryu and Baek-Yeol Ryoo in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-TIF-1-tam-10.1177_17588359221097934 for Real-world efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis by Yeong Hak Bang, Choong-kun Lee, Changhoon Yoo, Hong Jae Chon, Moonki Hong, Beodeul Kang, Hyung-Don Kim, Sook Ryun Park, Won-Mook Choi, Jonggi Choi, Danbi Lee, Ju Hyun Shim, Kang Mo Kim, Young-Suk Lim, Han Chu Lee, Min-Hee Ryu and Baek-Yeol Ryoo in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Footnotes

Ethical approval and patient consent statement: The ethical review boards of each participating site approved the study protocol (Asan Medical Center, 2021-1199; Yonsei Cancer center, 4-2021-1302; CHA Bundang Medical Center, 2021-10-024) and waived the need for informed consent for this study given the non-requirement of consent in retrospective analyses according to the regulations in Korea.

Consent for publication: All data are reported in an anonymized, aggregate manner.

Author contribution(s): Yeong Hak Bang: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Choong-kun Lee: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Changhoon Yoo: Conceptualization; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Hong Jae Chon: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Moonki Hong: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Beodeul Kang: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Hyung-Don Kim: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Sook Ryun Park: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Won-Mook Choi: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Jonggi Choi: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Danbi Lee: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Ju Hyun Shim: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Kang Mo Kim: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Young-Suk Lim: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Han Chu Lee: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Min-Hee Ryu: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Baek-Yeol Ryoo: Conceptualization; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

ORCID iDs: Yeong Hak Bang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6544-6431

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6544-6431

Changhoon Yoo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1451-8455

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1451-8455

Hong Jae Chon  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6979-5812

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6979-5812

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Yeong Hak Bang, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Choong-kun Lee, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Changhoon Yoo, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Seoul 05505, Korea.

Hong Jae Chon, Department of Medical Oncology CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

Moonki Hong, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Beodeul Kang, Department of Medical Oncology CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea.

Hyung-Don Kim, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Sook Ryun Park, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Won-Mook Choi, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Jonggi Choi, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Danbi Lee, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Ju Hyun Shim, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Kang Mo Kim, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Young-Suk Lim, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Han Chu Lee, Department of Gastroenterology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Min-Hee Ryu, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Baek-Yeol Ryoo, Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, Songpa-gu, Seoul 05505, Korea.

References

- 1. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 524–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 1163–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng A-L, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 2492–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu AX, Kang Y-K, Yen C-J, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 282–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1894–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abou-Alfa GK, Chan SL, Kudo M, et al. Phase 3 randomized, open-label, multicenter study of tremelimumab (T) and durvalumab (D) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): HIMALAYA. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40(Suppl. 4): 379. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelley RK, Yau T, Cheng AL, et al. VP10-2021: cabozantinib (C) plus atezolizumab (A) versus sorafenib (S) as first-line systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC): results from the randomized phase III COSMIC-312 trial. Ann Oncol 2022; 33: 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 282–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yau T, Kang Y-K, Kim T-Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib: the CheckMate 040 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: e204564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10: 2298–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogasawara S, Koroki K, Kanzaki H, et al. Changes in therapeutic options for hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. Epub ahead of print 15 November 2021. DOI: 10.1111/liv.15101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsoris A, Marlar CA. Use of the Child Pugh score in liver disease. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finkelmeier F, Scheiner B, Leyh C, et al. Cabozantinib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: efficacy and safety data from an International Multicenter Real-Life Cohort. Liver Cancer 2021; 10: 360–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tovoli F, Dadduzio V, De Lorenzo S, et al. Real-life clinical data of cabozantinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2021; 10: 370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H-D, Bang Y, Lee MA, et al. Regorafenib in patients with advanced Child-Pugh B hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre retrospective study. Liver Int 2020; 40: 2544–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marrero JA, Kudo M, Venook AP, et al. Observational registry of sorafenib use in clinical practice across Child-Pugh subgroups: the GIDEON study. J Hepatol 2016; 65: 1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rimassa L, Personeni N, Czauderna C, et al. Systemic treatment of HCC in special populations. J Hepatol 2021; 74: 931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vogel A, Frenette C, Sung M, et al. Baseline liver function and subsequent outcomes in the phase 3 REFLECT study of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2021; 10: 510–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kelley RK, Meyer T, Rimassa L, et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels and clinical outcomes in the phase III CELESTIAL study of cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2020; 26: 4795–4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruix J, Cheng A-L, Meinhardt G, et al. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol 2017; 67: 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shen J, Chan HL, Wong GL, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by combined serum biomarkers. J Hepatol 2012; 56: 1363–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Personeni N, Bozzarelli S, Pressiani T, et al. Usefulness of alpha-fetoprotein response in patients treated with sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 57: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Teufel M, Seidel H, Köchert K, et al. Biomarkers associated with response to regorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019; 156: 1731–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trojan J, Mollon P, Daniele B, et al. Comparative efficacy of cabozantinib and ramucirumab after sorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and alpha-fetoprotein ⩾ 400 ng/ml: a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Adv Ther 2021; 38: 2472–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelley RK, Mollon P, Blanc JF, et al. Comparative efficacy of cabozantinib and regorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Ther 2020; 37: 2678–2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoo C, Byeon S, Bang Y, et al. Regorafenib in previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of prior immunotherapy and adverse events. Liver Int 2020; 40: 2263–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casadei-Gardini A, Rimassa L, Rimini M, et al. Regorafenib versus cabozantinb as second-line treatment after sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: matching-adjusted indirect comparison analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021; 147: 3665–3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rimassa L, Kelley RK, Meyer T, et al. Outcomes based on plasma biomarkers for the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib versus placebo in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2022; 11: 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheon J, Yoo C, Hong JY, et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2022; 42: 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abou-Alfa G, Cheng A, Saletan S, et al. PB02-04 clinical activity of cabozantinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with anti-VEGF and immuno-oncology therapy: subgroup analysis from the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial. In: Liver cancer summit-abstract book, Prague, 6–8 February 2020, p. 234. Prague: EASL. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rimassa L, Danesi R, Pressiani T, et al. Management of adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: improving outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev 2019; 77: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tam-10.1177_17588359221097934 for Real-world efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis by Yeong Hak Bang, Choong-kun Lee, Changhoon Yoo, Hong Jae Chon, Moonki Hong, Beodeul Kang, Hyung-Don Kim, Sook Ryun Park, Won-Mook Choi, Jonggi Choi, Danbi Lee, Ju Hyun Shim, Kang Mo Kim, Young-Suk Lim, Han Chu Lee, Min-Hee Ryu and Baek-Yeol Ryoo in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-TIF-1-tam-10.1177_17588359221097934 for Real-world efficacy and safety of cabozantinib in Korean patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis by Yeong Hak Bang, Choong-kun Lee, Changhoon Yoo, Hong Jae Chon, Moonki Hong, Beodeul Kang, Hyung-Don Kim, Sook Ryun Park, Won-Mook Choi, Jonggi Choi, Danbi Lee, Ju Hyun Shim, Kang Mo Kim, Young-Suk Lim, Han Chu Lee, Min-Hee Ryu and Baek-Yeol Ryoo in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology