Abstract

Context:

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has been shown to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and diabetes. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy was shown to reduce inflammation and improves glycemic status. Recently, adjunctive low level laser therapy (LLLT) has been shown to alter the inflammatory process.

Aim:

To evaluate and compare the alteration in TNF-α levels before and after treatment in patients with periodontitis with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Settings and Design:

Randomised clinico-biochemical study was carried out for 8 weeks from September 2019 to December 2020.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty-four participants were divided into Groups A (periodontitis) and B (periodontitis associated with T2DM), based on probing depth ≥5 mm, clinical attachment level ≥2 mm, and history of T2DM. Later were subdivided into A1, A2, B1, B2, based on assigned treatments. Clinical periodontal parameters and salivary TNF-α levels were evaluated and compared at baseline to 8 weeks.

Statistical Analysis:

Multiple group comparisons were done using analysis of variance, intra group comparisons were made using t-tests.

Results:

Comparison of periodontal parameters and salivary TNF-α levels from baseline to 8 weeks showed statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in all groups, indicating a positive effect of scaling and root planing (SRP) and adjunctive LLLT.

Conclusion:

Both SRP and SRP with adjunctive LLLT effectively altered TNF-α levels, correlating reduced periodontal inflammation.

Keywords: Low-level laser therapy, periodontitis, salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha, scaling and root planing, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis (P) is an inflammatory response caused by pathogenic microorganisms of longstanding dental biofilm resulting in progressive damage to tooth-supporting structures.[1] The occurrence of rapid periods of destruction is observed in periodontitis, mainly influenced by systemic or environmental factors due to host and bacterial interactions, compromising host defence system.[2]

A complex bidirectional relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and periodontitis creates a vicious circle exacerbating both diseases when present simultaneously in the same individual.[3,4]

Global burden of disease study (2017) postulated that severe periodontal disease was the 11th most common condition in the world, ranging from 20% to 50%.[5] Oral health survey by dental council of India reported 17.5% and 21.4% of periodontitis between the ages 35–44 and 65–74 years respectively.[6] In India, out of 77 million people with T2DM, 75% of individuals suffer from periodontitis.[7,8]

Periodontitis and T2DM, according to Southerland et al. (2006) share common pathogenesis involving an increased inflammatory reaction on the local and systemic level,[9] with elevated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a macrophage-released pro-inflammatory cytokine and a prototypical ligand of the TNF superfamily, is one of the pro-inflammatory factors. It's a pleiotropic molecule that plays a key role in inflammation, the development of the immune system, apoptosis, and lipid metabolism.[10]

Various therapeutic modalities of periodontitis include scaling and root planing (SRP), disinfectants,[11] antibiotics,[12] and surgical techniques.[13] Recently, few studies reported a reduction in TNF-α levels in periodontitis after SRP.[14,15,16] Many had addressed periodontal treatment on metabolic control and TNF-α level of individuals with T2DM in serum and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF).[17,18,19,20,21,22]

However, SRP has certain physical limitations, such as the inability to access interproximal and furcation areas and deep periodontal pockets.[23] To surmount the limitations of SRP and reduce the bacterial load, laser therapy (LT) has been proposed as a treatment strategy for periodontitis. All available laser wavelengths are being used in dentistry as an adjunct to SRP.[24]

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has a bio-stimulatory, anti-infective, and anti-ablation effect.[25] Studies on LLLT adjunct to SRP have shown decreased TNF-α levels in GCF and gingival tissue level of periodontitis subjects by suppressing the bacterial presence and bio stimulating the healing tissue through an anti-inflammatory effect.[26,27]

Salivary cytokines have also been increasingly related to periodontal status and oral inflammatory burden in recent times. Since systemic inflammation influences salivary inflammatory burden, it is easy, rapid, and noninvasive as a salivary biomarker.

In the literature, very few studies have attempted to correlate the levels of TNF-α in periodontitis and T2DM adjunct to LLLT.[27,28,29]

Hence in the present study, an attempt was made to evaluate and compare salivary TNF-α levels in periodontitis associated with and without T2DM before and after SRP alone and SRP with adjunctive LLLT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was designed and conducted between September 2019 and December 2020, before commencement of the study institutional ethical clearance was obtained.

Inclusion criteria consisted of; body mass index (BMI) normal (18.5–24.9) based on WHO criteria.[30] Periodontitis with a probing depth (PD) of ≥5 mm, clinical attachment level (CAL) of ≥2 mm.[31] Periodontitis and well-controlled T2DM.

Participants who underwent LT in the past 3 months. Surgical or nonsurgical therapy within 6 months before the study. Pregnancy, lactating women. Autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis,[32] ankylosing spondylitis,[33] inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis,[34] refractory asthma.[35] With Oro mucosal abnormalities. Tobacco habit in any form, and the presence of prosthetic teeth were excluded to avoid confounding effect.

For allocation of the participants, determined a Power analysis with 95% confidence intervals and a sample size of n = 64.

Participants were grouped based on PD, CAL and history of T2DM under medication as periodontitis and as T2DM associated with periodontitis. Based on computer-generated randomisation tables, these groups were subdivided into A1, A2, B1, B2 as follows:

Group A: Participants with periodontitis alone

Group B: Participants with periodontitis and T2DM

Group A1: Participants of Group A receiving SRP alone

Group A2: Participants of Group A receiving SRP + LLLT

Group B1: Participants of Group B receiving SRP alone

Group B2: Participants of Group B receiving SRP + LLLT.

All the eligible participants were thoroughly informed about the nature, potential risks, and benefits of participation obtained informed consent and were subjected to full mouth SRP (FM-SRP) in single sitting within 24 h under local anaesthesia. Participants in Groups A2 and B2 were recalled within 1 week and were subjected for LLLT. Oral hygiene instructions were given to all the participants to follow strict maintenance protocol during the study period.

Random blood sugar (RBS) level was evaluated at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment, using glucometer, by capillary finger-prick method.[36,37]

Demographic information was collected, including the (1) Age; (2) Gender; (3) The BMI was calculated by dividing the body weight (in kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters).

Periodontal parameters were measured and recorded at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment. The following clinical periodontal parameters were included in the study: Plaque index (PI),[38] Bleeding index (BI),[39] PD, and CAL using a sterile mouth mirror, explorer, and UNC-15 probe (Hu-friedy's).[31]

PD and CAL were measured to the nearest millimeters at four sites per tooth i.e., around mesiobuccal, mid buccal, distobuccal, and lingual surfaces, using UNC-15 probe (Hu–friedy).[31] Obtained PD by measuring the distance from the gingival margin to the base of the periodontal pocket.[31] Obtained CAL by measuring the distance from the Cemento enamel junction to the base of the periodontal pocket.

LLLT was done with the wavelength of 630–670 nm and 0.8 W of power output, equipped with a probe tip, was applied externally with light contact to the gingival tissues corresponding to pockets apical-coronal direction for 15s per site including both lingual, buccal and interproximal sites. The Laser tip was discarded after each session.

Three milliliters of unstimulated saliva were collected at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment from all the participants into sterile tubes using the method that described by Navazesh.[40] The samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 2000–3000 rpm and kept at-80°C until the experiment. Salivary TNF-α levels were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique.

Participants in Groups A2 and B2 were recalled within 1 week and were subjected for LLLT. All the clinical parameters, and salivary TNF-α levels were evaluated between 7 and 8 weeks after SRP and LLLT.

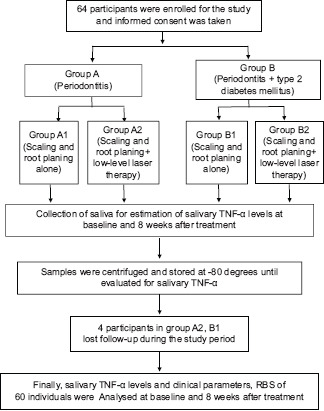

Four individuals lost their follow-up after treatment; finally included 60 participants for analysis. Representation of study methodology is shown in [study Flow Chart 1].

Flow Chart 1.

Study flow chart. TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; RBS – Random Blood Sugar

All the clinical and biochemical parameters were subjected to statistical analysis using the Jamovi version (1.2.27). Basic descriptions were presented in the form of mean and standard deviation. Multiple group comparisons were done using analysis of variance. For intragroup comparisons, t-tests were used. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for all tests.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics such as gender, the mean and standard deviation of age, BMI in all the groups. represented in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data representing mean and standard deviation of gender, age, body mass index in all the groups

| Demographic variables | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 7 | 5 | 9 | 7 |

| Females | 9 | 9 | 5 | 9 |

| Age, mean±SD | 47.56±6.17 | 43.86±7.63 | 46.43±7.93 | 45±9.15 |

| BMI, mean±SD | 23.3±1.46 | 22.5±1.90 | 22.2±1.86 | 22.5±1.72 |

T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level laser therapy; BMI – Body mass index; SD – Standard deviation

Intragroup comparison of clinical (PI, BI, PD CAL) parameters, Salivary TNF-α and RBS levels from baseline and 8 weeks after treatment. All parameters showed a significant (P < 0.05) difference represented in [Tables 2, 2a, 2b].

Table 2.

Intragroup comparison of clinical parameters from baseline and 8 weeks after treatment

| Groups | Clinical parameters | Time interval | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | 95% CI | t | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| A1 | PI | Baseline | 16 | 1.73±0.45 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 1.33 | 7.73 | 15.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 0.69±0.21 | ||||||||

| BI | Baseline | 16 | 1.90±0.63 | 1.46 | 1.142 | 1.77 | 9.86 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 0.44±0.17 | ||||||||

| PD | Baseline | 16 | 6.05±0.63 | 3.19 | 2.79 | 3.54 | 18.1 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 2.88±0.41 | ||||||||

| CAL | Baseline | 16 | 6.06±0.66 | 2.18 | 2.79 | 3.56 | 17.7 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 2.88±0.41 | ||||||||

| A2 | PI | Baseline | 14 | 1.71±0.51 | 1.11 | 0.815 | 1.41 | 8.04 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 0.69±0.21 | ||||||||

| BI | Baseline | 14 | 2.29±0.42 | 1.17 | 0.908 | 1.44 | 9.59 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 1.12±0.48 | ||||||||

| PD | Baseline | 14 | 5.98±0.59 | 2.99 | 2.57 | 3.54 | 15.3 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 2.99±0.43 | ||||||||

| CAL | Baseline | 14 | 2.99±0.43 | 3.03 | 2.58 | 3.49 | 14.4 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 2.99±0.43 | ||||||||

| B1 | PI | Baseline | 14 | 2.00±0.66 | 1.62 | 1.26 | 1.97 | 9.92 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 0.38±0.14 | ||||||||

| BI | Baseline | 14 | 1.96±0.62 | 1.54 | 1.53 | 1.92 | 8.66 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 0.43±0.17 | ||||||||

| PD | Baseline | 14 | 5.93±0.97 | 2.93 | 2.50 | 3.52 | 14.9 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 3.00±0.48 | ||||||||

| CAL | Baseline | 14 | 6.15±0.94 | 3.03 | 2.68 | 3.38 | 18.9 | 13.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 3.12±0.59 | ||||||||

| B2 | PI | Baseline | 16 | 2.14±0.57 | 1.83 | 1.55 | 2.10 | 14.30 | 15.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 0.31±0.14 | ||||||||

| BI | Baseline | 16 | 1.84±0.55 | 1.39 | 1.086 | 1.69 | 9.84 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 0.45±0.12 | ||||||||

| PD | Baseline | 16 | 5.87±0.94 | 3.01 | 2.50 | 3.52 | 12.6 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 2.86±0.44 | ||||||||

| CAL | Baseline | 16 | 5.97±1.00 | 3.04 | 2.55 | 3.53 | 13.3 | 15.0 | <0.001* | |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 2.93±0.49 | ||||||||

*Paired t-test, value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; t – t statistic value; df – Degrees of freedom; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive to low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level laser therapy; PI – Plaque index; BI – Bleeding index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; CI – Confidence interval

Table 2a.

Intragroup comparison of salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels from baseline and 8 weeks after treatment

| Groups | Time interval | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | 95% CI | t | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| A1 | Baseline | 16 | 14.42±2.53 | 5.14 | 0.59 | 1.74 | 4.33 | 15.0 | <0.01* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 9.13±1.72 | |||||||

| A2 | Baseline | 14 | 14.43±1.85 | 4.38 | 1.04 | 2.20 | 6.02 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 10.04±1.86 | |||||||

| B1 | Baseline | 14 | 21.05±2.60 | 6.87 | 4.87 | 8.22 | 8.45 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 14.18±2.43 | |||||||

| B2 | Baseline | 16 | 21.59±2.25 | 7.99 | 4.45 | 11.52 | 4.82 | 15.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 12.36±2.29 | |||||||

*Paired t-test, value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; t – t statistic value; df – Degrees of freedom; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy; CI – Confidence interval

Table 2b.

Intragroup Comparison of Random blood sugar Levels from baseline and 8 weeks after treatment

| Groups | Time interval | n | Mean±SD | Mean difference | 95% CI of the difference | t | df | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| A1 | Baseline | 16 | 95.37±3.48 | 1.75 | 0.46 | 3.03 | 2.91 | 15.0 | 0.01* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 93.62±4.33 | |||||||

| A2 | Baseline | 14 | 94.92±3.66 | 1.29 | 0.66 | 1.90 | 4.50 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 93.64±3.69 | |||||||

| B1 | Baseline | 14 | 167.07±13.28 | 2.79 | 1.74 | 3.83 | 5.77 | 13.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 14 | 164.28±11.97 | |||||||

| B2 | Baseline | 16 | 165.25±11.97 | 2.56 | 1.31 | 3.81 | 4.39 | 15.0 | <0.001* |

| 8 weeks | 16 | 162.68±11.17 | |||||||

*Paired t test, value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; t – t statistic value; df – Degrees of freedom; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy; CI – Confidence interval

Intergroup comparison of clinical parameters at baseline, showed significant difference (P < 0.05), in salivary TNF-α levels and RBS. whereas PI, BI, PD, CAL did not show any difference represented in [Tables 3, 3a, 3b].

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of clinical parameters at baseline

| Parameter | Study groups | n | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| F | P | ||||

| PI | A1 | 16 | 1.73±0.45 | 2.24 | 0.09 (NS) |

| A2 | 14 | 1.71±0.51 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 2.00±0.66 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 2.14±0.57 | |||

| BI | A1 | 16 | 1.90±0.63 | 1.88 | 0.14 (NS) |

| A2 | 14 | 2.29±0.42 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 1.96±0.62 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 1.84±0.55 | |||

| PD | A1 | 16 | 6.05±0.63 | 0.14 | 0.94 (NS) |

| A2 | 14 | 5.98±0.59 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 5.93±0.97 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 5.87±0.94 | |||

| CAL | A1 | 16 | 6.06±±0.66 | 0.13 | 0.94 (NS) |

| A2 | 14 | 6.02±0.62 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 6.15±0.94 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 5.97±1.00 | |||

P>0.05 statistically NS. n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; NS – Nonsignificant; P – Probability; PI – Plaque index; BI – Bleeding index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Table 3a.

Intergroup comparison of salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels at baseline

| Parameter | Study groups | n | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| F | P | ||||

| TNF-α | A1 | 16 | 14.42±2.53 | 48.4 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 14 | 14.43±1.60 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 20.92±2.55 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 21.59±2.25 | |||

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Table 3b.

Intergroup comparison of random blood sugar levels at baseline

| Parameter | Study groups | n | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| F | P | ||||

| RBS | A1 | 16 | 95.62±3.14 | 282.2 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 14 | 96.52±3.66 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 167.07±13.68 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 165.25±11.176 | |||

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. RBS – Random blood sugar; n – Number of participants; SD – Standard deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Intergroup comparison of Salivary TNF-α levels at 8 weeks after treatment showed a significant difference (P < 0.05), represented in [Table 4].

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison of salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels at 8 weeks after treatment

| Time interval | Study groups | n | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| F | P | ||||

| 8 weeks | A1 | 16 | 9.28±0.976 | 20.06 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 14 | 9.24±1.090 | |||

| B1 | 14 | 14.04±2.397 | |||

| B2 | 16 | 12.36±2.297 | |||

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. P – Probability; n – Number of participants; SD – Standard Deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Intergroup comparison of the change in clinical parameters, TNF-α, RBS levels from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment, is represented in [Table 5, 5a, 5b] respectively. PI, BI, salivary TNF-α, RBS showed a significant difference (P < 0.05), whereas PD, CAL did not show any difference.

Table 5.

Intergroup comparison of change in clinical parameters from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment

| Parameter | Groups | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| F | P | |||

| PI | A1 | 1.04±0.54 | 7.68 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 1.11±0.52 | |||

| B1 | 1.62±0.61 | |||

| B2 | 1.83±0.51 | |||

| BI | A1 | 1.46±0.59 | 7.05 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 1.17±0.46 | |||

| B1 | 1.54±0.66 | |||

| B2 | 1.39±0.56 | |||

| PD | A1 | 3.16±0.70 | 0.24 | 0.87 (NS) |

| A2 | 2.99±0.73 | |||

| B1 | 2.93±0.74 | |||

| B2 | 3.01±0.95 | |||

| CAL | A1 | 3.18±0.72 | 0.13 | 0.94 (NS) |

| A2 | 3.03±0.79 | |||

| B1 | 3.03±0.60 | |||

| B2 | 3.04±0.92 | |||

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. P>0.05 statistically NS. SD – Standard deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; P – Probability; NS – Nonsignificant. PI – Plaque index; BI – Bleeding index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Table 5a.

Intergroup comparison of change in salivary Tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment

| Parameter | Groups | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| F | P | |||

| TNF-α | A1 | 5.18±1.98 | 12.06 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 4.39±2.10 | |||

| B1 | 6.88±1.60 | |||

| B2 | 9.23±2.11 | |||

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; SD – Standard deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Table 5b.

Intergroup comparison of change in random blood sugar level from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment

| Parameter | Groups | Mean±SD | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| F | P | |||

| RBS | A1 | 93.62±4.33 | 282.9 | <0.001* |

| A2 | 93.64±3.69 | |||

| B1 | 164.28±13.68 | |||

| B2 | 162.68±11.17 | |||

RBS – Random blood sugar; SD – Standard Deviation; ANOVA – Analysis of variance; F – Fisher in ANOVA test; *Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. P – Probability; T2DM – Type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing alone; A2 – Periodontitis participants receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low-level laser therapy; B1 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing alone; B2 – Periodontitis participants with T2DM receiving scaling and root planing with adjunctive low level-laser therapy

Correlation of clinical parameters, RBS and TNF-α levels at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment in different groups showed a significant difference in PI and RBS scores (P < 0.05), represented in [Table 6].

Table 6.

Represents correlation of clinical, random blood sugar and salivary tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment in different groups

| Time interval | Salivary parameter | Clinical parameters | Spearman’s corelation | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | TNF-α levels | PI | 0.15 | 0.24 (NS) |

| BI | −0.17 | 0.19 (NS) | ||

| PD | −0.11 | 0.40 (NS) | ||

| CAL | −0.05 | 0.67 (NS) | ||

| RBS | 0.766 | <0.001* | ||

| 8 weeks | TNF-α levels | PI | −0.52 | <0.01* |

| BI | −0.13 | 0.29 (NS) | ||

| PD | −0.07 | 0.54 (NS) | ||

| CAL | 0.007 | 0.38 (NS) | ||

| RBS | 0.630 | <0.001* |

*Value of P is considered statistically significant P<0.05. P>0.05 statistically NS. TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; PI – Plaque index; BI – Bleeding index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment level; RBS – Random blood sugar; P – Probability; NS – Nonsignificant

DISCUSSION

Various efforts at eliminating infectious agents through periodontal treatment often do not represent a definitive therapy in periodontitis, warranting more sophisticated treatment modalities.[41]

In the present study, the demographic characteristics (age, gender, BMI) showed no significant difference between all the study groups indicating the proper random assignment of participants avoiding selection bias.

BMI within normal range (18.5–24.9) was taken into consideration because of its relevance to TNF-α. As the literature mentions that increased BMI (>24.9) leads to inflammatory state, that is characterised by the increase in production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α), and its soluble receptors, leading to severity of periodontal disease and insulin resistance in T2DM when associated with periodontitis.[42,43,44]

In the present study glucometer was used as a chairside diagnostic device, for RBS evaluation,[37] in order to improve the patient's comfort. As the literature also mentions that in some cases, HbA1c cannot be trusted due to defect in glycation or severe anemia.[44]

The majority of investigations,[22,27] have involved GCF because of its proximity to the site and release of molecular markers, making it site-specific but, at the same time, limiting its role to express the status of other inactive sites. However, saliva sampling solved this problem because it represents pooled concentrations obtained from all the sites in the mouth, giving an overall assessment of disease status and severity.[45] Saliva is considered over serum for the estimation of TNF-α as it is noninvasive and has equal potency. The present study was conducted involving unstimulated saliva to assess the salivary TNF-α levels in periodontitis patients with and without T2DM before and after SRP alone and SRP with adjunctive LLLT.

In the present study FM SRP was performed in single sitting within 24 h, followed by maintenance phase. According to Apatzidou and Kinane[46] both FM-SRP and quadrant-SRP (Q-SRP) modalities are efficacious, and also FM-SRP shows less recolonization when compared to Q-SRP.[47]

Additionally, lasers of various wavelengths have been proposed as alternative treatments for nonsurgical periodontal therapy, because of considerable antibacterial potential by direct ablation, thermal denaturation, or other destruction of bacterial cells. The application of LLLT would reduce bacteria with fewer thermal side effects.[48,49]

LLLT was given within 1 week after SRP in groups A2 and B2. As LLLT showed reduction in migration of monocytes and neutrophils to the site of inflammation thus reducing the production of TNF-α, and other chemotactic factors, initiating the back-feeding of inflammatory process. Therefore, LLLT would contribute to the breakdown of positive feedback loop of inflammation, when it is applied after SRP.[27]

Clinical parameters PI, BI, PD, CAL and response of TNF-α levels were evaluated at 8 weeks after treatment. There was a time gap of 7 to 8 weeks after LLLT, before the final readings were taken. As the studies mention that there was precisely oriented collagen bundle fibers, between 4 and 8 weeks for the primary evaluation of nonsurgical therapy.[27,50,51]

No difference was observed in clinical parameters at baseline, indicating direct result of the intervention. A significance in TNF-α and RBS levels were observed as we had included participants with T2DM (Group B1, B2).[52]

Intra and intergroup comparisons of PI and BI from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment in all groups showed significant difference. This result can be attributed to reducing local factors like plaque and calculus by SRP and improving inflammatory conditions by SRP adjunct to LLLT. This was in accordance with the studies conducted by Calderín et al.,[27] Giannopoulou et al.,[53] Badersten et al.[54] Whereas, Nguyen et al.,[55] obtained similar results in 3 months period.

In the present study, intragroup comparison of PD and CAL from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment, all groups showed significant difference. This change can be due to reduced inflammation and the formation of reattachment following SRP and removal of pocket lining, hemostasis, and coagulation of periodontal inflamed soft tissues by SRP adjunct to LLLT. The results are in accordance with the studies conducted by Calderín et al.,[27] Reis et al.,[56] Giannopoulou et al.[53] Whereas Euzebio Alves et al.,[57] Morozumi et al.,[58] Chen et al.[17] obtained similar results in 6 weeks’ time period.

In the present study, the intergroup comparison of PD and CAL at 8 weeks after SRP showed no significant difference. May be due to mechanical therapy alone. It is not effective in eliminating pathogenic bacterial species in the soft tissue and areas inaccessible to periodontal instruments, such as deep pockets, furcation areas, and root depressions. The results are in agreement with studies conducted by Dukić et al.,[59] Calderín et al.,[27] Euzebio Alves et al.,[57] Giannopoulou et al.[53]

Intergroup comparison of PD and CAL at 8 weeks after SRP adjunct to LLLT showed no significant difference. The results are in accordance with study conducted by Calderín et al.[27] This may be due to the efficacy of LLLT in periodontal disease is still controversial.

In the present study, the intragroup comparison of salivary TNF-α levels from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment showed a significant difference in all the groups. This change may be due to mechanical therapy, and the anti-inflammatory effect of LLLT reduced the clinical inflammation. Whereas Giannopoulou et al.,[53] Calderín et al.,[27] observed similar results who evaluated in GCF, Chen et al.,[17] evaluated in serum, Pesevska et al.,[26] evaluated at the gingival tissue level. However, contradictory results were obtained by Morozumi et al.,[58] who evaluated TNF-α levels in GCF.

In the present study, intergroup Comparison at 8 weeks after SRP showed a significant difference in TNF-α levels. This change may be due to reduced clinical inflammation through mechanical therapy. Whereas Correa et al.,[19] and Kardesler et al.,[20] observed similar results who evaluated in serum. However, Chen et al.,[17] Morozumi et al.,[58] obtained contradictory results who evaluated in serum and in GCF respectively. This may be attributed to difference in sampling timings.

In the present study, intergroup comparison at 8 weeks after SRP adjunct to LLLT showed a significant difference in TNF-α levels; this change may be due to LLLT adjunct to SRP prevented the bacterial recolonisation. The results are in agreement with studies conducted by Giannopoulou et al.,[53] Chen et al.,[17] Reis et al.[56] However, contradictory results were observed by Morozumi et al.,[58] Lalla et al.,[60] D’Aiuto et al.,[14] Calderín et al.[27]

In the present study, both intra and intergroup comparison of RBS levels showed a significant difference from baseline to 8 weeks after treatment in all the groups. In the Diabetic group (B1 and B2), this significance difference may be indicative of the effects of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on diabetic patient's glycemic control. In comparison, similar results were observed in the study by Martínez-Aguilar et al.,[52] who evaluated by using HbA1c.

Comparison of RBS and salivary TNF-α levels at baseline and 8 weeks after treatment in different groups showed a significant correlation; this may be due to effective periodontal therapy that might have decreased RBS values by reducing TNF-α concentrations. Whereas Dağ et al.,[21] showed similar results by evaluating through HbA1c.

CONCLUSION

There is an association between salivary TNF-α levels in periodontitis and T2DM

SRP and SRP adjunct to LLLT showed significant improvement in clinical and salivary TNF-α levels

Further studies recommended with histological analysis and larger sample size.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was registered at Clinical Trials Registry, India, with registration number CTRI/2019/02/017737.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickup JC, Crook MA. Is type II diabetes mellitus a disease of the innate immune system? Diabetologia. 1998;41:1241–8. doi: 10.1007/s001250051058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preshaw PM, Foster N, Taylor JJ. Cross-susceptibility between periodontal disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: An immunobiological perspective. Periodontol 2000. 2007;45:138–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesia R, Gholami F, Huang H, Clare-Salzler M, Aukhil I, Wallet SM, et al. Systemic inflammatory responses in patients with type 2 diabetes with chronic periodontitis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4:e000260. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaju JP, Zade RM, Das M. Prevalence of periodontitis in the Indian population: A literature review. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:29–34. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson RG, Shlossman M, Budding LM, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, Genco RJ, et al. Periodontal disease and NIDDM in Pima Indians. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:836–40. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.8.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Moss K, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Commonality in chronic inflammatory diseases: Periodontitis, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:130–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118:503–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prietto NR, Martins TM, Santinoni CD, Pola NM, Ervolino E, Bielemann AM, et al. Treatment of experimental periodontitis with chlorhexidine as adjuvant to scaling and root planing. Arch Oral Biol. 2020;110:104600. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.104600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jepsen K, Jepsen S. Antibiotics/antimicrobials: Systemic and local administration in the therapy of mild to moderately advanced periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2016;71:82–112. doi: 10.1111/prd.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mailoa J, Lin GH, Khoshkam V, MacEachern M, Chan HL, Wang HL. Long-term effect of four surgical periodontal therapies and one non-surgical therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2015;86:1150–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Tonetti MS. Acute effects of periodontal therapy on bio-markers of vascular health. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:124–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazaki K, Honda T, Oda T, Ueki-Maruyama K, Nakajima T, Yoshie H, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment on the C-reactive protein and proinflammatory cytokine levels in Japanese periodontitis patients. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:53–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2004.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Górska R, Gregorek H, Kowalski J, Laskus-Perendyk A, Syczewska M, Madaliński K. Relationship between clinical parameters and cytokine profiles in inflamed gingival tissue and serum samples from patients with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:1046–52. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6979.2003.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Luo G, Xuan D, Wei B, Liu F, Li J, et al. Effects of non-surgical periodontal treatment on clinical response, serum inflammatory parameters, and metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized study. J Periodontol. 2012;83:435–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katagiri S, Nagasawa T, Kobayashi H, Takamatsu H, Bharti P, Izumiyama H, et al. Improvement of glycemic control after periodontal treatment by resolving gingival inflammation in type 2 diabetic patients with periodontal disease. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:402–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correa FO, Gonçalves D, Figueredo CM, Bastos AS, Gustafsson A, Orrico SR. Effect of periodontal treatment on metabolic control, systemic inflammation and cytokines in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:53–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kardeşler L, Buduneli N, Cetinkalp S, Kinane DF. Adipokines and inflammatory mediators after initial periodontal treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2010;81:24–33. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dağ A, Firat ET, Arikan S, Kadiroğlu AK, Kaplan A. The effect of periodontal therapy on serum TNF-alpha and HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetic patients. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarro-Sanchez AB, Faria-Almeida R, Bascones-Martinez A. Effect of non-surgical periodontal therapy on clinical and immunological response and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic patients with moderate periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:835–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleischer HC, Mellonig JT, Brayer WK, Gray JL, Barnett JD. Scaling and root planing efficacy in multirooted teeth. J Periodontol. 1989;60:402–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.7.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoki A, Sasaki KM, Watanabe H, Ishikawa I. Lasers in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2004;36:59–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makhlouf M, Dahaba MM, Tunér J, Eissa SA, Harhash TA. Effect of adjunctive low level laser therapy (LLLT) on nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30:160–6. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesevska S, Nakova M, Gjorgoski I, Angelov N, Ivanovski K, Nares S, et al. Effect of laser on TNF-alpha expression in inflamed human gingival tissue. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:377–81. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-0898-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calderín S, García-Núñez JA, Gómez C. Short-term clinical and osteoimmunological effects of scaling and root planing complemented by simple or repeated laser phototherapy in chronic periodontitis. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28:157–66. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eivazi M, Falahi N, Eivazi N, Eivazi MA, Raygani AV, Rezaei F. The effect of scaling and root planning on salivary TNF-α and IL-1α concentrations in patients with chronic periodontitis. Open Dent J. 2017;11:573–80. doi: 10.2174/1874210601711010573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gürsoy UK, Yildiz Çiftlikli S, Könönen E, Gürsoy M, Doğan B. Salivary interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-α in relation to periodontitis and glycemic status in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2015;7:681–8. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuno H, Yudoh K, Katayama R, Nakazawa F, Uzuki M, Sawai T, et al. The role of TNF-alpha in the pathogenesis of inflammation and joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): A study using a human RA/SCID mouse chimera. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:329–37. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rebelo A, Leite S, Cotter J. Association of ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn's disease successfully treated with infliximab. BioDrugs. 2010;24(Suppl 1):37–9. doi: 10.2165/11586220-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schottelius AJ, Moldawer LL, Dinarello CA, Asadullah K, Sterry W, Edwards CK., 3rd Biology of tumor necrosis factor-alpha- implications for psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:193–222. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berry M, Brightling C, Pavord I, Wardlaw A. TNF-alpha in asthma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:279–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S13–28. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rapone B, Ferrara E, Santacroce L, Topi S, Converti I, Gnoni A, et al. Gingival crevicular blood as a potential screening tool: A cross sectional comparative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7356. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:21–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benamghar L, Penaud J, Kaminsky P, Abt F, Martin J. Comparison of gingival index and sulcus bleeding index as indicators of periodontal status. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:147–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navazesh M. Methods for collecting saliva. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deo V, Bhongade ML. Pathogenesis of periodontitis: Role of cytokines in host response. Dent Today. 2010;29:60–2. 64-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2075–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzanavari T, Giannogonas P, Karalis KP. TNF-alpha and obesity. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2010;11:145–56. doi: 10.1159/000289203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alzamil H. Elevated serum TNF-α is related to obesity in type 2 diabetes mellitus and is associated with glycemic control and insulin resistance. J Obes. 2020;2020:5076858. doi: 10.1155/2020/5076858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang CZ, Cheng XQ, Li JY, Zhang P, Yi P, Xu X, et al. Saliva in the diagnosis of diseases. Int J Oral Sci. 2016;8:133–7. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apatzidou DA, Kinane DF. Quadrant root planing versus same-day full-mouth root planing. I. Clinical findings. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:132–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6979.2004.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zijnge V, Meijer HF, Lie MA, Tromp JA, Degener JE, Harmsen HJ, et al. The recolonization hypothesis in a full-mouth or multiple-session treatment protocol: A blinded, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:518–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, Schauer P, Doertbudak O, Wernisch J, et al. Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22:302–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:5<302::aid-lsm7>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moritz A, Gutknecht N, Doertbudak O, Goharkhay K, Schoop U, Schauer P, et al. Bacterial reduction in periodontal pockets through irradiation with a diode laser: A pilot study. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15:33–7. doi: 10.1089/clm.1997.15.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segelnick SL, Weinberg MA. Reevaluation of initial therapy: When is the appropriate time? J Periodontol. 2006;77:1598–601. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biagini G, Checchi L, Miccoli MC, Vasi V, Castaldini C. Root curettage and gingival repair in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1988;59:124–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martínez-Aguilar VM, Carrillo-Ávila BA, Sauri-Esquivel EA, Guzmán-Marín E, Jiménez-Coello M, Escobar-García DM, et al. Quantification of TNF-α in patients with periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:7984891. doi: 10.1155/2019/7984891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giannopoulou C, Cappuyns I, Cancela J, Cionca N, Mombelli A. Effect of photodynamic therapy, diode laser, and deep scaling on cytokine and acute-phase protein levels in gingival crevicular fluid of residual periodontal pockets. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1018–27. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badersten A, Nilvéus R, Egelberg J. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. I. Moderately advanced periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;8:57–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1981.tb02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen NT, Byarlay MR, Reinhardt RA, Marx DB, Meinberg TA, Kaldahl WB. Adjunctive non-surgical therapy of inflamed periodontal pockets during maintenance therapy using diode laser: A randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2015;86:1133–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.150152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reis C, DA Costa AV, Guimarães JT, Tuna D, Braga AC, Pacheco JJ, et al. Clinical improvement following therapy for periodontitis: Association with a decrease in IL-1 and IL-6. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:323–7. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Euzebio Alves VT, de Andrade AK, Toaliar JM, Conde MC, Zezell DM, Cai S, et al. Clinical and microbiological evaluation of high intensity diode laser adjutant to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A 6-month clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morozumi T, Yashima A, Gomi K, Ujiie Y, Izumi Y, Akizuki T, et al. Increased systemic levels of inflammatory mediators following one-stage full-mouth scaling and root planing. J Periodontal Res. 2018;53:536–44. doi: 10.1111/jre.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dukić W, Bago I, Aurer A, Roguljić M. Clinical effectiveness of diode laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized clinical study. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1111–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lalla E, Kaplan S, Yang J, Roth GA, Papapanou PN, Greenberg S. Effects of periodontal therapy on serum C-reactive protein, sE-selectin, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion by peripheral blood-derived macrophages in diabetes. A pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]