Abstract

Mirror therapy is increasingly used in stroke rehabilitation to improve functional movements of the affected limb. However, the extent of mirroring in conventional mirror therapy is typically fixed (1:1) and cannot be tailored based on the patient’s impairment level. Further, the movements of the affected limb are not actively incorporated in the therapeutic process. To address these issues, we developed an immersive VR system using HTC Vive and Leap Motion, which communicates with our free and open-source software environment programmed using SteamVR and the Unity 3D gaming engine. The mirror therapy VR environment was incorporated with two novel features: (1) scalable mirroring and (2) shared control. In the scalable mirroring, mirror movements were programmed to be scalable between 0 and 1, where 0 represents no movements, 0.5 represents 50% mirroring, and 1 represents 100% mirroring. In shared control, the contribution of the mirroring limb to the movements was programmed to be scalable between 0 to 1, where 0 represents 100% contribution from the mirroring limb (i.e., no mirroring), 0.5 represents 50% of movements from the mirrored limb and 50% of movements from the mirroring limb, and 1 represents full mirroring (i.e., no shared movements). Validation experiments showed that these features worked appropriately. The proposed VR-based mirror therapy is the first fully developed system that is freely available to the rehabilitation science community. The scalable and shared control features can diversify mirror therapy and potentially augment the outcomes of rehabilitation, although this needs to be verified through future experiments.

Keywords: virtual rehabilitation, motor control, telehealth, low cost, illusion, mirror neurons

1. Introduction

Stroke affects millions of people every year (WHO 2002) and is the leading cause of long-term adult disability in the United States (Virani et al. 2020). Those who survive often have impairments that disproportionately affect the movement of one side of their body. These impairments can manifest as weakness (hemiparesis) or abnormal coordination, both of which affect the survivor’s ability to control the limbs on their more-impaired side. Asymmetric motor control can lead to increased reliance on the less-impaired limb, inhibiting rehabilitation and restoration of normal movement. Therefore, a key element of rehabilitation should be restoring symmetrical movement across the body.

Mirror therapy is a commonly used therapeutic approach to improving movement control after stroke, particularly in severely impaired stroke survivors. Conventional mirror therapy obstructs the patient’s view of their more-impaired limb and then uses a mirror to reflect the less-impaired limb onto the more-impaired limb. This creates the illusion that the more-impaired limb’s movements are the same as the less-impaired limb. Mirror therapy works by primarily activating the mirror neurons and ipsilateral projections of the primary sensorimotor cortex (Garry et al. 2005; Fritzsch et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2020). Mirror therapy is also known to strengthen the functional connectivity between the sensorimotor cortex and the supplementary motor area, thereby making it a potentially powerful approach to restoring sensorimotor function after stroke (Bai et al. 2020). Originally used to relieve phantom limb pain in amputees (V. S. Ramachandran et al. 1995; V.S. Ramachandran & Rogers-Ramachandran 2019), mirror therapy has since been expanded to help stroke survivors with impairments in both the upper (Arya and Pandian 2013; Park et al. 2015; Arya et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016; Thieme et al. 2018) and lower limbs (Broderick et al. 2018; Arya et al. 2019). However, conventional mirror therapy can only provide a fixed, one-to-one representation of the movements of less-impaired limb onto the more-impaired limb. Thus, the movements of the more-impaired limb will perfectly track the movements of the less-impaired limb and cannot be altered based on patient-specific impairments. This can break the mirror therapy illusion, especially if a patient’s more-impaired limb has significantly reduced mobility, because the patient can quickly realize that the movements they see are not real (González-Franco et al. 2010). Further, conventional mirror therapy cannot incorporate movements of the more-impaired limb, which is critical for neuroplasticity and recovery after stroke (Kleim and Jones 2008). This can also break the illusion of mirror therapy because the limb the user sees does not react to their motor commands. Given that the effects of mirror therapy depend on creating a convincing illusion, altering (1) the coupling between the more- and less-impaired limbs and (2) the contribution of the more-impaired limb could help augment the therapeutic benefits of mirror therapy in stroke survivors.

Previous researchers have implemented mirror therapy in a virtual reality (VR) environment (Kang et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2014; In et al. 2016; Hoermann et al. 2017; Weber et al. 2019; Heinrich et al. 2020). These previous virtual reality systems enabled the user to see a virtual depiction, either via a computer screen or VR headset, of both the mirrored and mirroring limbs, as well as a detailed virtual environment. Occasionally, the environment would feature an object that the user is meant to interact with, such as a cup. Typically, these previous systems only allowed for the movement of one joint or extremity and used special equipment and/or software to determine kinematics, such as a custom joystick or a sensor that monitored the position of a tracker attached to the participant (Kang et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2014; Weber et al. 2019; Heinrich et al. 2020). A key advantage of VR-based mirror therapy is that the application can be extended beyond the physical confines of the mirror box, particularly when using an immersive system (Morkisch et al. 2019). Further, VR interventions can provide an enriched environment to perform various therapeutic activities, which can improve patient engagement and motivation (Crosbie et al. 2007; Subramanian and Levin 2011; Subramanian et al. 2013, 2020).

A noteworthy disadvantage of these previous systems is, like a physical mirror, they only allowed for a perfect mirroring of the less-impaired limb onto the more-impaired limb. Specifically, these previous VR systems could not alter the extent of movement coupling between limbs or integrate inputs from the more-impaired limb. Because the patient only sees a virtual rendering of their body in VR, it is possible to alter the rendered movements of the more-impaired limb so that they are not a perfect mirroring of the less-impaired limb (Morales-Rodriguez and Pavard 2007). This allows for new types of mirror therapy that consider inputs from the more-impaired limb. Specifically, mirroring could be altered so that the joint angles of the virtual more-impaired limb are scaled relative to the reflected less-impaired limb. For example, if the real less-impaired shoulder is abducted 90°, 50% scaling would show only 45° of abduction in the virtual more-impaired shoulder. This would create a type of mirror therapy that is still engaging to the sensorimotor system, but more believable to the user. We call this “scalable mirroring”. Further, the virtual more-impaired limb could incorporate the movements of the more-impaired limb in addition to the mirrored movements of the less-impaired limb, which we call “shared control”. The relative consideration of each limb would depend on the goals of therapy, ranging from “conventional mirror therapy” (all control is from the less-impaired limb) to “normal movement” (all control is from the more-impaired limb). Shared control would encourage patients to challenge their more impaired limbs and make the mirror therapy more believable, as the rendered movements in VR would respond to the actual movements of the more-impaired limb. The incorporation of scalable and shared mirror therapy could potentially revolutionize the concept of mirror therapy and lead to a paradigm shift in stroke rehabilitation. However, scalable mirroring and shared control are yet to be implemented in a VR environment, so their advantages over conventional mirror therapy are unknown.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to develop a novel platform for scalable mirroring and shared control settings in a custom-made VR environment. We also validated the VR application for its intended use by ensuring that the (1) kinematics of the virtually-rendered user, or “avatar”, reasonably reflected the kinematics of the user, (2) mirrored limb was correctly reflected across the user’s center of the body (i.e., mid-sagittal plane), (3) mirrored movements are appropriately scaled in scalable mirroring, and (4) mirrored movements appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control. Finally, we also made this software freely available to the public so that the application is immediately translatable to the clinic with minimal cost and hardware requirements.

2. Methods

2.1. Equipment and Software

The system was primarily developed on a laboratory desktop computer (Intel Xeon W-2125 [4 GHz base frequency, 4 cores], 256GB NVMe M.2 Solid-State Drive [for OS], NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 6GB, and 1TB NVMe M.2 Solid-State Drive [for memory]), while some minor development was also conducted on a student’s laptop (ASUS ROG GL502VS-DS71, 7th Generation Intel® Kaby Lake™ i7–7700HQ (2.8GHz - 3.8GHz, 6MB Intel® Smart Cache) Processor, NVIDIA® GeForce® GTX 1070 (8GB) GDDR5 (Pascal) DX12, 240GB Solid State Drive (SATA III 6GB/s), 1TB Samsung 960 EVO M.2 NVMe PCIe SSD (Read 3200MB/s - Write 1900MB/s). The software repository for our system can be found here: https://github.com/NeuRRoLab/NeuRRoVR. We used the Unity game engine (Unity Technologies, Version 2018.2.12f1) to create our virtual world so that we could evaluate our scalable mirroring and shared control systems. This virtual world was composed of a virtual representation of the user (i.e., the avatar) and its surroundings. The program included a graphical user interface (Fig. 1b) that allowed us to select different avatars (Fig. 1c), change their skin tone (Fig. 1d), and scale their anthropometry to match the user. The degrees of freedom (DOF) of the avatar’s joints are shown in Table 1. These DOFs were governed by measurements from sensors both attached to the user and fixed relative to the laboratory environment (Fig. 1a). We used an HTC Vive Headset to track the motion of the user’s head. An HTC Vive Tracker was attached to the user’s lower back to track their position in the virtual environment and their trunk orientation. HTC Vive Controllers were fixed to the user’s forearms to track their arm posture, and HTC Vive Trackers were attached to each of the user’s feet to track their leg posture (Fig. 1a). Additionally, we used a Leap Motion Controller (Leap Motion Labs, 90–0005) mounted to the headset to track the user’s wrist, hands, and fingers. Two HTC Vive SteamVR Base Stations (Version 1.0) were mounted on opposing corners of the data collection area to track the sensors on the user relative to a fixed reference frame (i.e., the laboratory). SteamVR (Version 1.14) used these base stations in conjunction with the sensors mounted on the user to provide a comprehensive virtual representation of the user (i.e., the avatar) as well as their position in the virtual environment.

Fig. 1.

A schematic of the (a) Sensors used and their recommended positions on the user. The headset located the position and orientation of the user’s head. The sensors on the user’s forearms and feet provided the kinematics for the arms and legs, respectively. A sensor fixed to the user’s back located the user’s trunk, and two SteamVR Base Stations (not pictured) mounted on opposing corners of the data collection area located the user in the virtual environment. A Leap Motion Controller provided kinematics for the user’s wrists, hands, and fingers; (b) Graphical user interface (GUI) of the virtual reality system. Through the GUI, the user could select different avatars to control, as well as alter the avatar’s anthropometry and skin tone; (c) Different avatars that could be controlled by the user in the virtual environment; and (d) Control to alter the skin tone of the avatar

Table 1.

Degrees of Freedom (DOF) of each Avatar joint.

| Arms | Fingers | Legs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Joint | DOF | Joint | DOF | Joint | DOF |

|

| |||||

| Shoulder | 3 | Finger Metacarpal | 2 | Hip | 3 |

| Elbow | 2* | Finger Proximal | 1 | Knee | 1 |

| Wrist | 2 | Finger Distal | 1 | Ankle | 2 |

| Thumb MCP | 2 | ||||

| Thumb IP | 1 | ||||

Note that the actual DOF for the elbow is 3 but has been indicated as 2 for simplicity due to anatomical constraints

The VR system contains two methods of calibrating the sensor readings to the participant: “pose” and “stylus-based” calibration. Prior to either calibration, the program requires the user’s segment lengths to be entered into the system (see Fig. 1b for all required measurements). This information was used to scale a VR character to match the user’s measured segment lengths. In pose calibration, a VR character with a predetermined pose was created so that the user could pose on to this character. The VR system then combined the sensor readings from this pose with the VR character’s pose information to calibrate the sensor measurements. The stylus-based calibration option was incorporated for individuals who cannot assume the calibration pose (e.g., individuals with significant disabilities) (Fig. 2a). During stylus-based calibration, an HTC Vive Controller was used to designate anatomical landmarks on the user. To calibrate the user’s torso, the stylus was used to touch the back tracker to assign it to the torso. The torso was assumed to be a rigid body, and the shoulder and hip joint centers were therefore assumed to be fixed, user-specific distances from the back tracker. Each shoulder and hip joint center were found by touching opposite sides of each joint with the stylus, from which the program took an average of both measurements to find the joint center. To calibrate the leg, the foot was assumed to be a rigid body and the ankle was assumed to be a fixed, user specific distance from the foot tracker. Therefore, the foot tracker was first assigned to the foot, then the ankle joint center was found by touching opposite sides of the joint with the stylus, and then the orientation of the foot relative to the foot tracker was found by aligning the stylus to the foot orientation. Similarly, the arm was calibrated by assuming the forearm was a rigid body and the elbow joint center was a fixed distance from the HTC Vive Controller attached to the forearm. The controller attached to the forearm was assigned, the elbow joint center was found by touching either side with a stylus, and the orientation of the forearm was found by aligning the stylus to the forearm. The position and orientation of the user’s head was assumed to coincide with the headset, and therefore did not require calibration.

Fig. 2.

(a) Demonstration of stylus-based calibration. Calibrating the torso starts by touching the calibration stylus (HTC Vive Controller) to the back tracker, which assigns the tracker to the torso. The shoulder and hip joint centers are assumed to be fixed distances from the back tracker (torso is assumed to be rigid) and are found by touching opposite sides of each joint with the calibration stylus and taking the average. To calibrate the leg, the foot is assumed to be rigid, then the tracker is assigned to the foot. Following this, the ankle joint center is assumed to be a fixed distance from the foot tracker and is found by touching opposite sides of the joint with the stylus and taking the average. Then the orientation of the foot is found by aligning the stylus with the foot’s orientation. Like the leg, the arm is calibrated by assuming that the forearm is a rigid body and assigning the tracker to the correct limb and then finding the elbow joint center and forearm orientation. (b) A diagram detailing how the virtual reality system determines the proximal segments of the user’s extremities. The positions of the trackers are directly accessible to the program (green vectors). The shoulder, elbow, hip, and ankle joint centers are known from calibration (orange vector). The humerus is computed as the difference between the vectors to the elbow and shoulder joint centers. To determine the knee position, the program assumes the hip, knee, and ankle joint centers fall in the same plane, and uses closed-form inverse kinematics to determine the knee joint center from the vector from the hip to the ankle and the measured thigh and shank lengths

We used inverse kinematics to reconstruct the proximal segments of the arms and legs because they were not directly accessible from the sensor readings (Fig. 2b). The humerus was constructed by creating a vector between the shoulder and elbow joint centers, both found during calibration. It is important to note that the joint center of the wrist position can be determined from the forearm tracker and the Leap Motion Controller. To correct for kinematic misalignment between the two sensors, position output from the Leap Motion controller was used when the hands are in view, otherwise, the position was found via the Vive Controller attached to the forearm. To find the position of the user’s knee joint center, the program first assumed that the ankle, knee, and hip joint centers were coplanar. The program then used a closed-form inverse kinematic solution of a two-link system (given the known positions of the ankle and hip joint centers from calibration and the measured femur and shank lengths) to find the position of the knee joint center. The program then constructed the femur by creating a vector between the hip and knee joint centers and constructed the shank by creating a vector between the knee and ankle joint centers.

2.2. Scalable Mirroring and Shared Control Systems

Within our VR system, we implemented two mirroring paradigms that generalize the concept of conventional mirror therapy: (1) scalable mirroring and (2) shared control (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A schematic of the different forms of mirror therapy. (a) Conventionally, mirror therapy creates a perfect reflection of the user’s limb. (b) In scalable mirroring, the virtual arm is no longer a perfect reflection of the user’s limb, instead exhibits motion that is scaled down from the user’s actual motion. (c) In shared control, the virtual limb is controlled by both limbs of the user

2.2.1. Scalable Mirroring

Scalable mirroring found a limb pose between the user’s actual pose and a predetermined reference pose (set prior to training), and then reflected this new pose across the midsagittal plane to the opposite limb. The position between the user and reference poses was determined by the scaling factor. Specifically, the program computed a rotation between the user and reference poses for each joint using angle-axis representation, i.e., a rotation angle about a single axis. A scaled pose was then created from the reference pose by rotating each joint about their axis by a scaled version of their rotation angle. This scaled pose was then reflected across the midsagittal plane and assigned to the opposing limb of the avatar. For example, the reference pose for the user’s left arm could be set while relaxed at their side (i.e., elbow fully extended, wrist in a neutral position, fingers straight) and the scaling factor set to 50%. If the user abducted their left shoulder until their hand pointed upwards (180°), the left arm of the avatar would mimic the movement of the user’s left arm while the right arm of the avatar would raise until it was parallel with the ground (90°) with the elbow, wrist, and finger joints unchanged. Expressed mathematically in Equation (1), if controlling the avatar’s right limb with the left, the avatar’s right limb pose is a scaled version of the rotation between the reference pose and the user’s left limb pose, mirrored across the midsagittal plane.

| (1) |

denotes the limb pose of the mirroring limb of the avatar, denotes the limb pose of the mirrored limb of the user relative to the reference pose, and λ is the scaling factor. Setting λ to 1 (100%) results in conventional mirror therapy, while 0 results in no control over the avatar’s limb. Intuitively, the above equation can be described as:

2.2.2. Shared Control

Shared control works similarly to scalable mirroring, except that instead of measuring rotation relative to a stationary reference pose, rotation is measured relative to the user’s mirroring limb. As a result, the limb of the avatar being controlled is sensitive to movement from both limbs of the user. The level of contribution from each limb is determined by an altered form of Equation (1) where the reference pose is replaced with the user’s right limb (i.e., denotes the limb pose of the mirrored limb of the user relative to the mirroring limb). Here, λ = 1 would represent conventional mirroring, λ = 0.5 would represent equal control from both limbs, and λ = 0 would recreate the user’s actual movement of the mirroring limb. Conceptually, the movements of the avatar limb can be described by a combination of movements from both the mirrored and the mirroring limbs, which is the same as the general idea of shared control in haptic interfaces/robotics (Abbink et al. 2012; Ranganathan 2017).

2.3. Software Validation

To evaluate the performance of our scalable mirroring and shared control programs in the virtual environment, we devised experiments to (1) compare the kinematics of the avatar to that of a user, (2) ensure that mirroring appeared as a true reflection from the user’s perspective, (3) ensure that mirrored movements are appropriately scaled in scalable mirroring, and (4) ensure that mirrored movements appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control. The kinematic data in each experiment were smoothed with a 4th order, 6 Hz low-pass Butterworth filter.

2.3.1. Comparing the kinematics of the avatar to the user

We compared the kinematics of the avatar to a user’s motion by having one of the coauthors perform two tests. In the first test, we evaluated how well the VR program could reconstruct a known path (circle of 0.75m radius) traced in a workspace. To ensure that a fixed path was followed during testing, one end of a string was fixed to the user’s end-effector while the other end was fixed to a horizontal table. The length of the string was measured, and the user then pulled the string taut and traced a circle five times on the table’s surface. The fixed point on the table and the path of the end-effector were measured in the VR program, and the average distance between the path and the fixed point was compared with the length of the string. We then computed the average absolute error between the circle’s radius measured by the VR program and the known string length. This testing was performed both with the wrist and the ankle treated as the end-effector.

In the second test, we compared joint angles recorded by the VR program to joint angles measured externally during different single DOF movements via Tracker, an open-source video analysis and modeling tool (Tracker, V5.1.5). Using webcam footage recorded during each movement, Tracker monitored the positions of small, brightly colored markers placed at anthropometric landmarks. The positions of these markers were then used to construct vectors fixed to the limbs connected by the joint. The joint angle corresponded to the angle between these vectors. We evaluated shoulder abduction/adduction, elbow flexion/extension, and knee flexion/extension movements. For each joint, we computed the average absolute error between the angles measured in VR and by Tracker.

2.3.2. Ensuring that mirroring is accurate from the user’s perspective

To evaluate whether the mirrored limb was correctly reflected across the user’s center of the body (i.e., mid-sagittal plane), we mirrored the user’s right arm across the midsagittal plane so that it appeared as their left arm in the VR environment. Then, the VR program measured the distance between different anatomical landmarks on both limbs and a point on the midsagittal plane. Specifically, the program measured the distances to each virtual joint center on both limbs while the user moved their real right arm. If the mirroring was accurate, the average absolute difference between distances to the same joint center on different limbs should be close to zero. For this experiment, we tracked the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and middle finger joint centers.

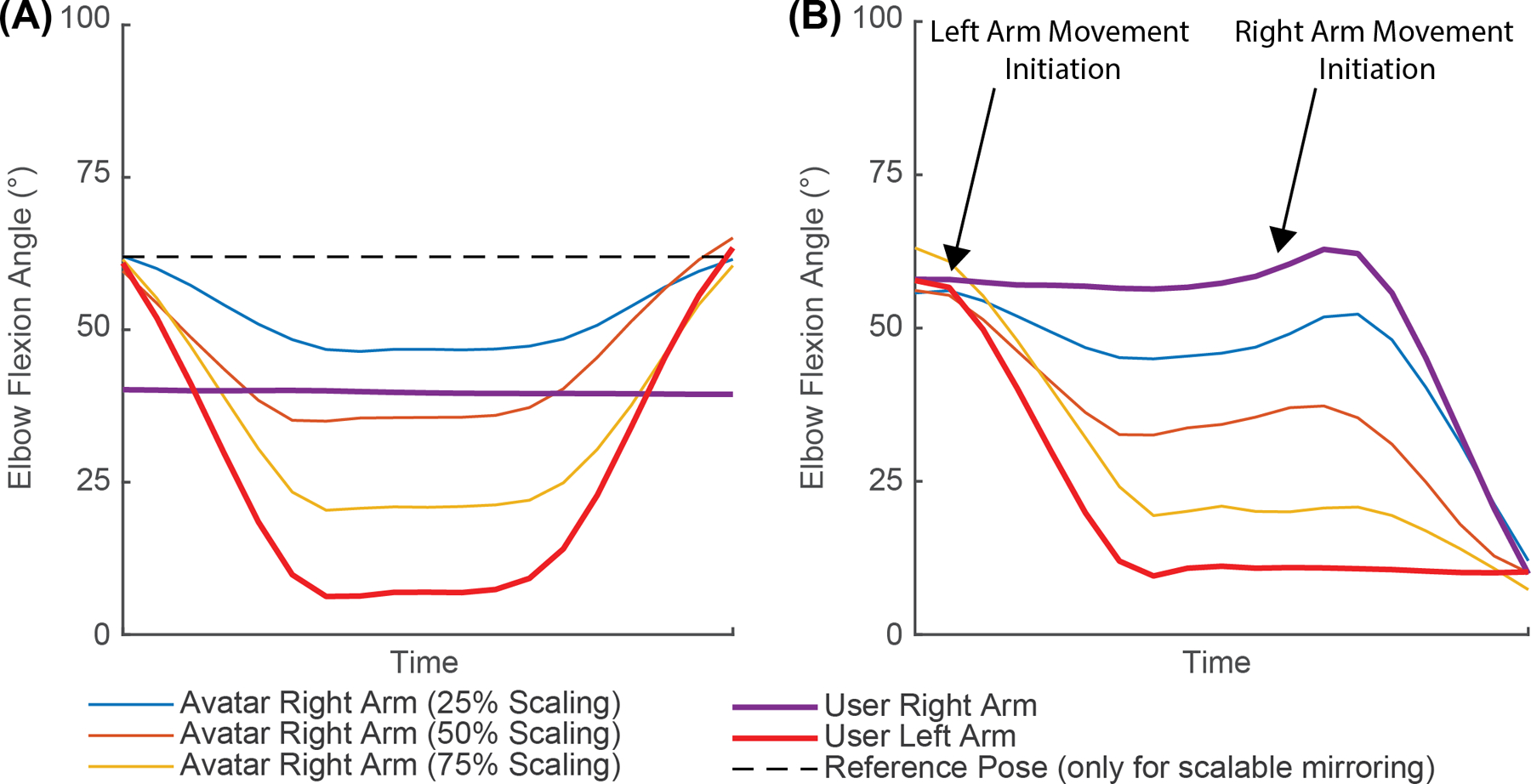

2.3.3. Ensuring mirrored movements are appropriately scaled in scalable mirroring

To examine if the program scaled the mirrored limb correctly, we mirrored the user’s left arm onto their right, and then measured the rotation of both limbs relative to the reference pose when performing a reaching task. The reference pose was set when the arms were resting on the armrests of a chair. We evaluated 25, 50, and 75% scaling for the elbow. Five trials were performed and the ensemble average of the five trials was used in the analysis.

2.3.4. Ensuring that mirrored movements appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control

To examine if the program appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control, we evaluated the rotations of both limbs when performing a reaching task while sharing control of the avatar’s right arm between the user’s right and left arms. The reaching task was initially performed with the left arm and then followed by the right arm. We investigated shared control ratios of 25, 50, and 75%.

3. Results

Comparing the kinematics of the avatar to the user:

The program accurately reconstructed the end-point of the user during the circle-drawing experiments with an average absolute error of 5.3±1.9%, 3.9±3.4%, 7.5±2.8%, and 3.5±2.2% (Fig. 4) for the right wrist, left wrist, right ankle, and left ankle positions, respectively. The avatar tracked the motion of the user at all joints in real-time (Fig. 5), tracking the position and orientation of their head and torso, as well as the configurations of their extremities. In general, the avatar’s joint angles matched the angles measured using the Tracker software well (Fig. 6), having an average error of 4.95°, 7.03°, and 13.53° for the shoulder, knee, and elbow, respectively.

Fig. 4:

The end-point trajectories recorded by the virtual reality program while the user traced a fixed trajectory (a circle of 0.75m radius). Note that the end-points were accurately tracked (average error of about 5%) by the virtual reality system

Fig. 5.

A schematic showing side-by-side comparisons of the user and the avatar in different postures in real-time. Note that the avatar tracked the user’s postures reasonably well without any noticeable differences

Fig. 6.

Comparison of joint angles measured by the virtual reality program with joint angles measured using Tracker software

Ensuring that mirroring is accurate from the user’s perspective:

The experiment to ensure accurate mirroring across the midsagittal plane found an average absolute error in distance of < 1mm for each joint center (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Measured distances from a point on the pelvis in the user’s mid-sagittal plane to different joint centers on each arm during conventional mirroring. Note that the distances from the pelvis to the joint centers on each arm were nearly identical, indicating that the mirroring happened correctly across the user’s mid-sagittal plane

Ensuring mirrored movements are appropriately scaled in scalable mirroring:

For scalable mirroring, the right arm of the avatar mimicked the user’s left arm according to the selected scaling factor, while the user’s left arm did not influence the avatar (Fig. 8a). The average angle of the user’s left elbow joint relative to the reference position was 35.76° during reaching, and the average angle of the virtual right elbow relative to the reference position was 9.76°, 17.16°, and 27.33° for the 25%, 50%, and 75% scaling conditions.

Fig. 8.

Traces of the elbow flexion angles (0° is full elbow extension) during (a) scalable mirroring and (b) shared control. In (a) the user reached forward with their left arm only, keeping their right arm stationary. In (b) the user reached forward with their left arm, and then followed that reach with an identical reach using their right arm. Note that the joint angles relative to the reference pose and the joint angles relative to the user’s right arm scaled appropriately in both scalable mirroring and shared control, respectively. The dashed line (black) denotes the reference pose for scalable mirroring

Ensuring that mirrored movements appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control:

For shared control, the right arm of the avatar accurately mimicked both of the user’s arms according to the selected shared control ratio (Fig.8b). The average angle of the user’s left elbow joint relative to the right was 28.53° during reaching, and the average angle of the virtual right elbow joint relative to the user’s right was 5.67°, 14.78°, and 23.24° for the 25%, 50%, and 75% scaling conditions.

4. Discussion

Mirror therapy has been shown to improve functional recovery by creating an illusion that a patient’s affected limb can perform normal movements (Samuelkamaleshkumar et al. 2014; Park et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016). However, conventional mirror therapy has several limitations: (1) the extent of mirroring is typically fixed (1:1 ratio) and cannot be controlled or tailored based on the patient’s impairment level, (2) the movements of the affected limb are not actively incorporated in the therapeutic process, and (3) therapy has to be usually limited to small movements and distal segments due to the physical constraints of the mirror. As a result, the effectiveness of mirror therapy is diminished because the patient can soon recognize that they are being tricked by the illusion and due to the lack of involvement of the paretic limb in the training process. VR can address these key issues by offering the possibility of scaling the extent of mirroring between limbs, incorporating the movements of the mirroring limb in a more realistic and modifiable environment, and eliminating the constraints of a physical mirror. Here, we showcase the development of a novel, open-source platform for scalable mirroring and shared control settings in a custom-made VR environment. We also evaluated the VR application for its intended use using validation experiments. The results of our study show that the VR program reasonably replicated the kinematics of the user, correctly reflected the mirrored limb across the user’s center of the body, appropriately scaled the mirrored movements in scalable mirroring, and appropriately incorporated the movements of each limb in shared control. We expect that these novel features can potentially augment the outcomes of mirror therapy and provide an opportunity to evaluate several mechanistic research questions related to mirror therapy and shared control that is not possible through conventional mirror therapy.

While numerous manuscripts have found that mirror therapy led to significant improvements in motor control (Samuelkamaleshkumar et al. 2014; Park et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016), a systematic review of mirror therapy literature found only moderate-quality evidence for its positive effects (Thieme et al. 2018). A possible explanation for the modest case made by the existing literature could be the users’ subconscious acknowledgment that the movements are not their own. Mirror therapy, in effect, distorts the user’s visual feedback of their more-impaired limb by displaying movements that do not reflect reality. While the positive therapeutic effects of mirror therapy derive from this distortion, manipulating visual feedback can lead to the user losing the feeling of ownership of the viewed movement (Sanchez-Vives and Slater 2005; González-Franco et al. 2010; O’Sullivan et al. 2018). Therefore, scalable mirroring and shared control could be viewed as adaptations of mirror therapy that preserve the positive therapeutic effects while improving the patient’s sense of movement ownership. Scalable mirroring scales the magnitude of the mirrored movements such that they more closely reflect (yet still amplify) the patient’s movements. This could activate similar neurological changes as seen in conventional, 1:1 mirror therapy, but improve therapeutic outcomes because the mirrored movements would be more believable. We anticipate that stroke survivors with highly asymmetric motor impairments would likely benefit the most from scaling because 1:1 mirror therapy displays movements vastly different from their capabilities, which could quickly break the illusion. Further, shared control encourages the user to use the more-impaired limb during training by incorporating it into the movements of the mirroring limb, which is a key determinant of positive therapy outcomes (Kleim and Jones 2008). This approach may also improve the outcomes of mirror therapy because incorporating the more-impaired limb into the visual feedback could improve the user’s sense of ownership of the visualized limb.

The VR system discussed in this manuscript offers the opportunity to investigate many interesting aspects of mirror therapy. For instance, the scalable mirroring and shared control features could be used to examine how altering visual feedback distortion (i.e., making the mirroring illusion more or less similar to reality) influences therapeutic outcomes. Specifically, this means investigating how scaling the mirrored movements (scalable mirroring) and incorporating the more-impaired limb (shared control) affect the resulting therapeutic benefits. Additionally, our VR system can be used to explore the therapeutic effects of disabling the motion of the avatar’s mirrored limb. This is not possible in conventional mirror therapy because the physical mirror only allows the user to perceive symmetric, bimanual motion. Using VR, it is possible to display the motion of only the mirroring limb while keeping the mirrored limb of the avatar locked. For example, if mirroring the left arm onto the right, the user would move their left arm, and only the right arm of the avatar would move (Fig. 9). We call the immobilization of the avatar’s mirrored limb “freeze” or “unimanual” control. The therapeutic effects of unimanual mirror therapy compared to bimanual, conventional mirror therapy are currently unknown, and our VR system would allow investigation of this novel premise.

Fig. 9.

A schematic of bimanual control (a) and “freeze” or unimanual control (b) when a user was performing a grasping task in the virtual reality environment. Note, in the bimanual control, both the mirrored and the mirroring limb moved when performing the task, whereas, in the unimanual control, only the mirroring limb moved while the mirrored limb was frozen

We believe that researchers and clinicians will find our VR system valuable because it contains unique advantages over previously developed VR systems. As stated earlier, previous VR systems derived their advantages from their ability to display large, highly detailed environments to the user and accommodate more varied motions than a physical mirror. However, the disadvantages of these systems were that they were typically only built to mirror one limb (e.g., only the arm) and were comprised of custom equipment/software not easily accessible to the average person. Our system, however, can mirror all extremities and is comprised of only commercially available or open-source hardware and software. More importantly, previous VR systems do not implement the scalable mirroring and shared control paradigms discussed in this manuscript. Therefore, these previous systems cannot be used to probe the effects of altering movement coupling and incorporating the more-impaired limb. Additionally, our system can track therapy progress across multiple sessions by measuring the excursion of each joint and comparing across training sessions. Joint excursion is a useful metric because mirror therapy tricks the patient into thinking they have more mobility in their more-impaired limb than they really do. Therefore, increased joint excursion would be a direct consequence of successful mirror therapy and a useful metric to researchers and clinicians.

Furthermore, our VR system could likely be successfully integrated into rehabilitation clinics, as it contains features that clinicians consider to be valuable in rehabilitation technology. Prior surveys from clinicians indicate that they favor rehabilitation equipment that allows many different arm movements, offers virtual activities of daily living, and scales assistance based on the stroke survivor’s stage of recovery (Lu et al. 2011). Our VR system meets these recommendations because it allows all movement, can create virtual environments to imitate activities of daily living, and the scalable mirroring and shared control features scale the visual assistance. Additionally, clinicians like the technology to be portable enough for in-home use and cost less than $6000 (Lu et al. 2011). Our system also meets these criteria because our software is open-source and all of the hardware is commercially available, designed for in-home use, and costs less than $3,000. To further probe clinicians’ opinions and to develop the VR system, we sought feedback from physical and occupational therapists (via a survey) regarding our product’s functionality and features that would be beneficial for a viable product. The survey was designed to evaluate the potential for a new product and to improve the current product. All agreed that mirror therapy in a virtual environment would be beneficial and challenge/improve the functional abilities of a stroke survivor. They also felt that virtual mirror therapy offers unique advantages over traditional approaches (Table 2). Concerning future improvements, they suggested including games that incorporate both conventional mirroring and our novel mirroring paradigms, tasks that train balance and coordination, settings for exercise progression, and options to perform treadmill-based gait training and different exercise routines (e.g. yoga, boxing, etc.). We plan to add these features (and any recommended by the future stakeholders [e.g., researchers, clinicians]) in future iterations of this technology.

Table 2.

Results from a product-development survey of our virtual reality system. In the survey, 14 therapists who have experience with mirror therapy and working with stroke survivors offered their feedback on our system.

| Question | StrAgr | Agr | Neu | Dis | Str Dis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Do you think virtual reality for Mirror Therapy will be beneficial? | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think that mirror therapy performed in the virtual reality environment would challenge/improve the functional abilities of a patient’s paretic limb? | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think that mirror therapy performed in the virtual reality environment offers unique advantages over traditional mirror therapy? | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you feel that incorporating different avatars (e.g., robot like, human like, etc.) makes the virtual environment more enjoyable? | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you feel that incorporating features for customization (e.g., sex, height, skin tone, etc.) makes the virtual environment more realistic and immersive to the user? | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think people could eventually recognize that they are getting tricked [by conventional mirror therapy] because they know that they cannot produce such movements? | 2 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you think that a patient would find Mirror Therapy in the virtual environment to be more convincing if there was an option to scale the extent of movements seen in the virtual world to mimic their functional capability? | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you think that scalable mirror therapy performed in the virtual reality environment would challenge/improve the functional abilities of a patient’s involved limb? | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you think that scalable mirror therapy could offer unique therapeutic benefits over conventional 1:1 mirror therapy? | 6 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think incorporating movements of the involved limb in Mirror Therapy will be beneficial? | 7 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you think that shared control therapy performed in the virtual reality environment would challenge/improve the functional abilities of a patient’s paretic limb? | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think that engaging the involved limb during mirror therapy will augment the therapeutic benefits of doing mirror therapy alone? | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think that employing mirror therapy, scaled therapy, or shared control to rehabilitate finger function would benefit your patients? | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you think that this type of virtual reality system will be a good addition to the rehabilitation clinic? | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the Table: Str Agr = Strongly Agree, Agr -=Agree, Neu = Neutral, Dis = Disagree, and Str Dis = Strongly Disagree

Although our primary objective in developing this system was to address stroke-related issues, we have included several features that are valuable to a wide range of patient populations (e.g., cerebral palsy, amputees, individuals with balance disorders, etc.). Additionally, we performed pilot-testing of our system during development with an individual who had balance issues from hepatic cirrhosis. This person provided development feedback that was incorporated into our system. Additionally, while this manuscript focuses primarily on mirror therapy and stroke rehabilitation, our open-source software offers many games that could be useful during balance training, hand rehabilitation, alleviating phantom limb sensation, etc. Furthermore, the program includes exercises and games that can be played in several postures (e.g., sitting, standing, or walking).

We note that it is possible to run this system for VR-based mirror therapy even if we did not have trackers on the affected side (e.g., due to missing limbs due to amputation). This is because in conventional mirroring and scalable mirroring, the movements of the opposite limb are projected onto the affected limb, and hence, the system does not require any information about the movements of the affected limb. However, this would mean that calibration could be only performed using the Pose calibration method and not the stylus calibration method. In addition, we note that shared control requires input from both limbs and therefore, our system does not accommodate it when one sensor or more sensor from the affected limb is missing. If this feature is required, then it is expected that the person with an amputated limb would be wearing a prosthesis. In this situation, the tracker could be placed on the prosthetic limb. Alternatively, if the individual has a lower-level amputation (e.g., foot or below-knee) the tracker could be placed on the stump.

5. Limitations

It is important to note that the objective of this manuscript was to develop a simple, low-cost, and open-source platform for virtual reality and mirror therapy research. While this manuscript establishes the functioning of these novel features of the VR system, it does not establish the clinical potential of this device. Therefore, this manuscript should not be treated as evidence for the clinical potential of virtual reality, mirror therapy, or the novel mirroring paradigms discussed in this manuscript. On the contrary, our hope is that the greater rehabilitation research community will use the tools we developed in this manuscript as a means to probe the clinical potential of these ideas and replicate the results of others. By encouraging different researchers to use the same platform, we hope that the resulting research findings will be easier to compare and replicate, thereby strengthening any conclusions.

6. Conclusions

In summary, this study introduces a novel, low-cost VR system for mirror therapy and establishes the performance of this system using controlled laboratory experiments. The software utilizes high-end graphics, has many customizable features including two unique generalizations of mirror therapy: scalable mirroring and shared control mirroring, and is freely available to the general public. The source codes are also publicly available in an open-source repository (GitHub) so that interested users can modify and expand the current system to suit their needs. We anticipate that scalable mirroring and shared control open up numerous research possibilities that can significantly improve our understanding of mechanistic underpinnings of mirror therapy and advance the field of neurorehabilitation.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Adobe Inc. for providing rigged humanoid characters to be used freely in the virtual reality system and also the clinicians who provided valuable feedback for the product development of the virtual reality system.

Funding:

This work was partly supported by the University of Michigan Office of Research under the Mcubed Diamond grant, National Institutes of Health (Grant # R01 EB019834), and National Science Foundation (Award # DGE 1256260 and Award # 1804053). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Code availability: The source codes are available for download through GitHub

References

- Abbink DA, Mulder M, Boer ER (2012) Haptic shared control: Smoothly shifting control authority? Cogn Technol Work 14:19–28. 10.1007/s10111-011-0192-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arya KN, Pandian S (2013) Effect of task-based mirror therapy on motor recovery of the upper extremity in chronic stroke patients: A pilot study. Top Stroke Rehabil 20:210–217. 10.1310/tscir2001-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya KN, Pandian S, Kumar D, Puri V (2015) Task-Based Mirror Therapy Augmenting Motor Recovery in Poststroke Hemiparesis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 24:1738–1748. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya KN, Pandian S, Kumar V (2019) Effect of activity-based mirror therapy on lower limb motor-recovery and gait in stroke: A randomised controlled trial. Neuropsychol Rehabil 29:1193–1210. 10.1080/09602011.2017.1377087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z, Fong KNK, Zhang J, Hu Z (2020) Cortical mapping of mirror visual feedback training for unilateral upper extremity: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Brain Behav 10:. 10.1002/brb3.1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick P, Horgan F, Blake C, et al. (2018) Mirror therapy for improving lower limb motor function and mobility after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture 63:208–220. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie JH, Lennon S, Basford JR, McDonough SM (2007) Virtual reality in stroke rehabilitation: Still more virtual than real. Disabil Rehabil 29:1139–1146. 10.1080/09638280600960909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch C, Wang J, Dos Santos LF, et al. (2014) Different effects of the mirror illusion on motor and somatosensory processing. Restor Neurol Neurosci 32:269–280. 10.3233/RNN-130343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry MI, Loftus A, Summers JJ (2005) Mirror, mirror on the wall: Viewing a mirror reflection of unilateral hand movements facilitates ipsilateral M1 excitability. Exp Brain Res 163:118–122. 10.1007/s00221-005-2226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Franco M, Pérez-Marcos D, Spanlang B, Slater M (2010) The contribution of real-time mirror reflections of motor actions on virtual body ownership in an immersive virtual environment. Proc - IEEE Virtual Real 111–114. 10.1109/VR.2010.5444805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C, Cook M, Langlotz T, Regenbrecht H (2020) My hands? Importance of personalised virtual hands in a neurorehabilitation scenario. Virtual Real. 10.1007/s10055-020-00456-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoermann S, Ferreira Dos Santos L, Morkisch N, et al. (2017) Computerised mirror therapy with Augmented Reflection Technology for early stroke rehabilitation: clinical feasibility and integration as an adjunct therapy. Disabil Rehabil. 39(15):1503–1514. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1291765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In T, Lee K, Song C (2016) Virtual Reality Reflection Therapy Improves Balance and Gait in Patients with Chronic Stroke: Randomized Controlled Trials. Med Sci Monit. 22: 4046–53. 10.12659/msm.898157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YJ, Park HK, Kim HJ, et al. (2012) Upper extremity rehabilitation of stroke: Facilitation of corticospinal excitability using virtual mirror paradigm. J Neuroeng Rehabil 9:. 10.1186/1743-0003-9-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee S, Kim D, et al. (2016) Effects of mirror therapy combined with motor tasks on upper extremity function and activities daily living of stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci 28:483–7. 10.1589/jpts.28.483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Jones TA (2008) Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: Implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res 51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Lee M, Lee K, Song C (2014) Asymmetric training using virtual reality reflection equipment and the enhancement of upper limb function in stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 23:1319–1326. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu EC, Wang RH, Hebert D, et al. (2011) The development of an upper limb stroke rehabilitation robot: Identification of clinical practices and design requirements through a survey of therapists. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 6:420–431. 10.3109/17483107.2010.544370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Rodriguez ML, Pavard B (2007) Design of an emotional and social interaction paradigm for the animation of 3D characters: The case of a therapy for brain injured people (the mirror neuron paradigm). Virtual Real 11:175–184. 10.1007/s10055-006-0063-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morkisch N, Thieme H, Dohle C (2019) How to perform mirror therapy after stroke? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Restor Neurol Neurosci 37:421–435. 10.3233/RNN-190935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan N, de Bezenac C, Piovesan A, et al. (2018) I Am There … but Not Quite: An Unfaithful Mirror That Reduces Feelings of Ownership and Agency. Perception 47:197–215. 10.1177/0301006617743392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH (2002) The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park Y, Chang M, Kim K-M, An D-H (2015) The effects of mirror therapy with tasks on upper extremity function and self-care in stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci 27:1499–501. 10.1589/jpts.27.1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D (2019) Mirror feedback assisted recovery from hemiparesis following stroke. in Reply to Morkisch et al.: How to perform mirror therapy after stroke? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci 37:437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D, Cobb S (1995) Touching the phantom limb. Nature 377:489–490. 10.1038/377489a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R (2017) Reorganization of finger coordination patterns through motor exploration in individuals after stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil 14:. 10.1186/s12984-017-0300-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelkamaleshkumar S, Reethajanetsureka S, Pauljebaraj P, et al. (2014) Mirror therapy enhances motor performance in the paretic upper limb after stroke: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 95:2000–2005. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vives MV, Slater M (2005) From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SK, Cross MK, Hirschhauser CS (2020) Virtual reality interventions to enhance upper limb motor improvement after a stroke: commonly used types of platform and outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SK, Levin MF (2011) Viewing medium affects arm motor performance in 3D virtual environments. J Neuroeng Rehabil 8:. 10.1186/1743-0003-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian SK, Lourenço CB, Chilingaryan G, et al. (2013) Arm motor recovery using a virtual reality intervention in chronic stroke: Randomized control trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 27:13–23. 10.1177/1545968312449695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieme H, Morkisch N, Mehrholz J, et al. (2018) Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke (Review) SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARIS1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Miyasaka H, Nonoyama S, et al. Randomized controlled comparative study on effect of training to improve lower limb motor paralysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1–182. 10.1002/14651858.CD008449.pub3.www.cochranelibrary.com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. (2020) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation E139–E596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber LM, Nilsen DM, Gillen G, et al. (2019) Immersive Virtual Reality Mirror Therapy for Upper Limb Recovery after Stroke: A Pilot Study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 98:783–788. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M-H, Zeng M, Shi M-F, et al. (2020) Visual feedback therapy for restoration of upper limb function of stroke patients. Int J Nurs Sci 7:170–178. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]