Abstract

Objectives

Public health trends are formed by political, economic, historical and cultural factors in society. The aim of this paper was to describe overall changes in mental health among adolescents and adults in a Norwegian population over the three last decades and discuss some potential explanations for these changes.

Design

Repeated population-based health surveys to monitor decennial changes.

Setting

Data from three cross-sectional surveys in 1995–1997, 2006–2008 and 2017–2019 in the population-based HUNT Study in Norway were used.

Participants

The general population in a Norwegian county covering participants aged 13–79 years, ranging from 48 000 to 62 000 000 in each survey.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence estimates of subjective anxiety and depression symptoms stratified by age and gender were assessed using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 for adolescents and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for adults.

Results

Adolescents’ and young adults’ mental distress increased sharply, especially between 2006–2008 and 2017–2019. However, depressive symptoms instead declined among adults aged 60 and over and anxiety symptoms remained largely unchanged in these groups.

Conclusions

Our trend data from the HUNT Study in Norway indicate poorer mental health among adolescents and young adults that we suggest are related to relevant changes in young people’s living conditions and behaviour, including the increased influence of screen-based media.

Keywords: mental health, public health, epidemiology, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The HUNT Study is a large general county population health survey repeated every decade since the 1980s in Norway, suitable for following trends in public health.

The total population of 13+ years are invited to complete the survey.

Identical screening tools for measuring anxiety and depression symptoms have been used in all three surveys covered by this article; Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-5 for adolescents and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for adults.

Data covered approximately 78% of the total adolescent population and 54%–70% of the total adult population with the risk of selection bias.

Changes in sociocultural and behavioural attitudes towards depression, anxiety and mental health in general in recent years may have made it easier for participants to report mental health concerns in questionnaires that may have introduced some reporting bias.

Introduction

Mental health problems are among the leading causes of disease burden worldwide.1 2 Further, mental health issues are primary drivers of disability worldwide, causing over 40 million years of disability in 20–29 year-olds.3 Depression alone accounts for more disability-adjusted life years than all other mental disorders together4 and is projected to become the leading cause of disability in high-income countries by 2030.5 Thus, the public health burden of mood disorders is substantial, with negative effects including functional problems, reduced quality of life, disability, low-work productivity, increased mortality and increased healthcare utilisation.

In Norway, estimates of years lived with disability in 2016 display anxiety and depression ranked as number four and seven on the list of the most contributing diseases in the Global Burden of Disease statistics.6 Mental disorders are highly prevalent in disability benefit statistics, with awards often granted at younger ages than for other diagnoses. Mental disorders have additionally been shown to be responsible for the most working years lost (33.8%) of any disability.7

During the last decade, rates of depressive symptoms have increased in several adolescent populations.8–10 In the USA, rates of depression, self-harm and suicide attempts increased substantially in adolescents after 2010.11–13 On the other hand, data have paradoxically shown an improvement in mental health with age indicating the opposite trend among older people.14 15

Several prominent research-based theories and models, which have provided significant support to modern understanding and practice of health promotion and disease prevention, may offer insights into understanding the causes of current trends in mental health. The WHO’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (SDH), for example, defined the SDH as ‘the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age’ as the fundamental drivers of public health.16 Thus, when observing emerging trends in population health, it is important to look at the underlying conditions that may drive the changes. The eminent epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose stressed that the determinants of individual cases and the determinants of incidence rates are two different issues. The second seeks the causes of changing incidence of health problems in the population.17 This theory argues that political, economic, historical and cultural trends in Western societies may have affected mental health by influencing changes in social living conditions. Neoliberalism has been the dominating political ideology in Europe and USA since the 1980s. Economic growth has been the main priority of the neoliberal agenda, together with the deregulation of economies, forcing open national and international markets to trade.18 This has contributed to major changes in the living conditions of groups in societies around the world, including young people. For many, optimism and the belief in economic growth and improved quality of life have been replaced by concerns about climate change, growing social injustice, threats to democracy and the threat of technological developments leading to increased exploitation and potentially magnifying many of these other concerns.19 These concerns have become particularly visible for young people growing up in many western, developed societies.

It has become increasingly apparent that the rapidly growing global unregulated information technology sector collects and mines enormous amounts of data on individuals.20 The term dataism is used to describe the mindset or philosophy created by this trend. Recently, the term has been expanded to describe what others, including leading historian Yuval Noah Harari and leading social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff, has called an emerging form of capitalism, ideology or even a new form of religion.20 21 The increase in global interactions has caused a growth in international trade and the exchange of ideas and culture. Consumerism, the increasing polarisation due to so-called technologically produced ‘echo-chambers’ in digitally mediated spaces of social interaction are but a few of the trends influencing these developments.22 Taking selfies, and along with that, improving our image for public consumption have become regular in younger generations.23

Driven by these societal and technological trends, the use of the internet began to increase in the early 2000s, and smartphones after 2010. Social media also became more popular after 2010. These trends may have had a significant impact on human behaviour, especially among adolescents and young adults. In several large studies, heavy users of such technologies are more likely to be depressed9 24 or have lower levels of well-being.9 25 Similarly, the HUNT Study of Norway have shown associations between the number of hours of screen time and increased anxiety and depression symptoms, which was particularly strong in girls when screen time predominantly involved the use of social media and internet.26 Declines in face-to-face social interaction among adolescents may also impact even non-users of digital media, increasing the need for social assurance and reducing opportunities for in-person social interaction.27 However, the need for social assurance fueled by excessive smartphone use is often not gratified, and eventually leads to greater loneliness.28 Some evidence suggests that increased time spent using these technologies and, more generally, exposure to the evolving modern technological environment may be causes of the sudden increase in depression since 2010.11 Stronger associations between digital media time and mental health indicators have been shown in girls compared with boys, perhaps because social media, used more frequently by girls, is more strongly linked to depression than gaming, used more frequently by boys.9 Furthermore, research on adolescents in Norway has associated psychiatric problems with sleep quality problems, which are exacerbated by the use of social media and computer gaming among adolescents.29–31 In addition, higher academic pressure following the dominant political preoccupation with competition and a credentials-based labour market influencing educational programmes may also have increased mental distress among adolescents and students.32 33 A Norwegian study has shown a clear decline in young peoples’ reporting of happiness and life satisfaction over the last 10 years. The study showed that increasing concern about the future contributed most to the decline. This concern was related to fears of various adverse events, such as future job opportunities and one’s own financial situation. Other conditions such as dissatisfaction with social relationships, health, physical fitness and body also had significance.34

The aim of this paper was to describe the parallel changes in mental health among adolescents and adults in a Norwegian population over the three last decades and suggest some potential explanations for these changes based on theories related to the social determinants of health.16 17

Methods

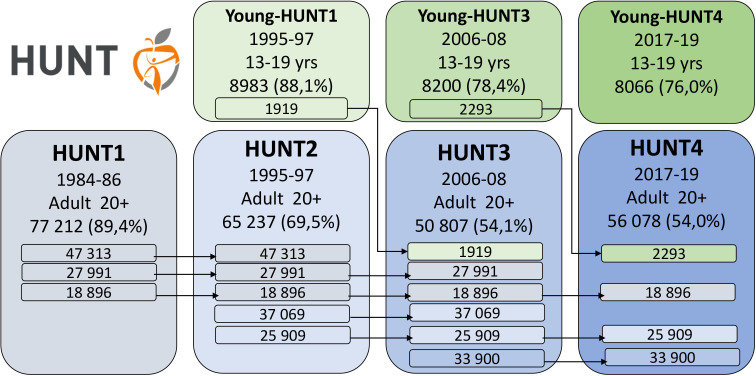

The data were taken from three different waves in the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), Young-HUNT1 and HUNT2 (1995–1997), Young-HUNT3 and HUNT3 (2006–2008) and Young-HUNT4 and HUNT4 (2017–2019) (figure 1).35 The invited participants were the total population in the Nord-Trøndelag County area aged 13–19 years (Young-HUNT) and 20+ years (HUNT).36 The numbers and attendance rates are shown in figure 1. The samples ranged from 8980 to 8066 adolescent participants and from 62 444 to 48 362 adult participants.

Figure 1.

Data collected in the HUNT Study, Norway. Number of participants and response rates.35 36

Data from the different decades were stratified by age and sex. In the Young-HUNT surveys, we applied the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 (HSCL-5). Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) is a widely applied self-report measure of anxiety and depression symptoms. Compared with the HSCL-25, the short form model fit is good and correlations with established measures demonstrate convergent validity.37 38 Prevalence (%) of anxiety and depression symptoms were measured with HSCL-5 (cut-off ≥2). For adults, we applied the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS is a brief 14-item self-report questionnaire, consisting of 7-items for the anxiety subscale (HADS-A) and 7 for the depression subscale (HADS-D), each scored on a Likert-scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (symptoms maximally present). For this study, valid ratings of the HADS-D and HADS-A were defined as at least five completed items on both subscales. The score of those who filled in five or six items was based on the sum of completed items multiplied with 7/5 or 7/6, respectively. We used the conventional cut-off threshold of ≥8 for the HADS subscales. This cut-off value is found to provide optimal sensitivity and specificity (about 0.80) and a good correlation with the case of clinical depression based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-8/9 diagnostic criteria.34 HADS is found to perform well in assessing the symptom severity and case categorisation of anxiety and depressive disorders in the general population and in somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients.39 Results are reported as prevalence (in %) along with 95% CI and we also report p values for linear trend according to time. Data management and analyses were done with Stata V.16.40

Patient and public involvement

Public stakeholders and patient organisations have been involved in the planning of all HUNT surveys. No patients were involved in the design or implementation of this specific study. As the study used previously collected data, we did not ask patients or the public to assess the burden of participation. Public stakeholders and patient organisations are involved in dissemination of results from the HUNT Study.

All participants gave informed consent before taking part in the HUNT Study.

Results

The percentage of adolescents screening positive for anxiety and depression nearly doubled between 1995–1997 and 2017–2019, from 15.3% to 29.8%, with most of the increase occurring between 2006–2008 and 2017–2019 (see table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics for the sample aged 13–19 years. The Young-HUNT Study36

| Young HUNT1 1995–1997 |

Young HUNT3 2006–2008 |

Young HUNT4 2017–2019 |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | 13–19 years | 8980 | 100 | 8199 | 100 | 8066 | 100 |

| Sex | Girls | 4463 | 49.7 | 4128 | 50.4 | 4106 | 50.9 |

| Boys | 4517 | 50.3 | 4071 | 49.6 | 3960 | 49.1 | |

| HSCL-5* | Low | 7412 | 82.5 | 6441 | 78.6 | 5410 | 67.1 |

| High | 1372 | 15.3 | 1520 | 18.5 | 2404 | 29.8 | |

| Missing | 196 | 2.2 | 238 | 2.9 | 252 | 3.1 | |

| Total | 8980 | 100 | 8199 | 100 | 8066 | 100 | |

*Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 (HSCL-5) cut-off ≥2.

The percentage of adults screening positive for depression declined from 9.4% in 1995–1997% to 6.7% in 2017–2019, and the percentage screening positive for anxiety increased from 12.4% in 1995–1997% to 13.4% in 2017–2019 (see table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics for the sample aged 20–79 years. The HUNT Study35

| HUNT2 (1995–1997) | HUNT3 (2006–2008) | HUNT4 (2017–2019) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age groups | 20–29 years | 9111 (14.6) | 4511 (9.3) | 6428 (12.3) |

| 30–39 years | 11 630 (18.6) | 6859 (14.2) | 6755 (12.9) | |

| 40–49 years | 13 603 (21.8) | 10 012 (20.7) | 9002 (17.2) | |

| 50–59 years | 11 058 (17.7) | 11 425 (23.6) | 10 761 (20.5) | |

| 60–69 years | 9048 (14.5) | 9801 (20.3) | 11 186 (21.3) | |

| 70–79 years | 7994 (12.8) | 5754 (11.9) | 8310 (15.9) | |

| Sex | Females | 32 991 (52.8) | 26 316 (54.4) | 28 488 (54.3) |

| Males | 29 453 (47.2) | 22 046 (45.6) | 23 954 (45.7) | |

| HADS depression* | Low | 51 049 (81.8) | 34 301 (70.9) | 35 271 (67.3) |

| High | 5855 (9.4) | 3453 (7.1) | 3505 (6.7) | |

| Missing | 5540 (8.9) | 10 608 (21.9) | 13 666 (26.1) | |

| HADS anxiety* | Low | 44 462 (71.2) | 32 192 (66.6) | 31 594 (60.3) |

| High | 7736 (12.4) | 5387 (11.1) | 7004 (13.4) | |

| Missing | 10 246 (16.4) | 10 783 (22.3) | 13 844 (26.4) | |

| Total | 62 444 (100) | 48 362 (100) | 52 442 (100) | |

*Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) cut-off ≥8.

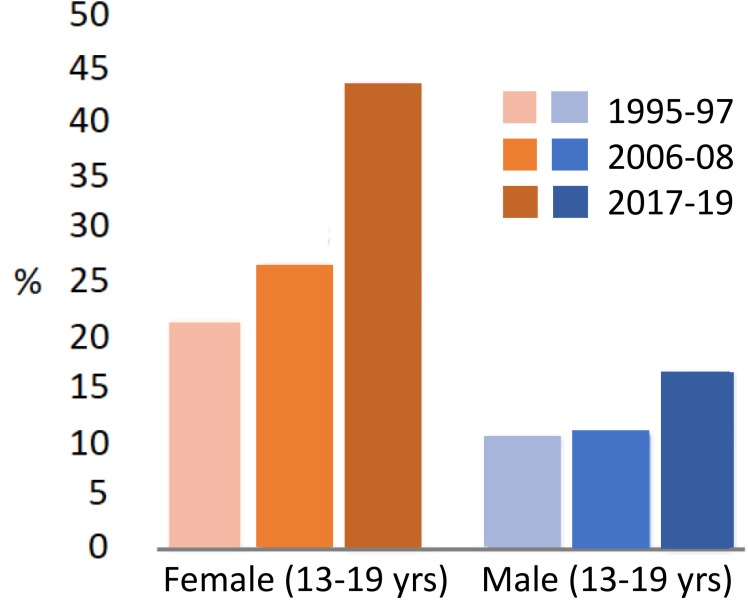

Table 3 shows the trends in prevalence (%) and 95 % CI for symptoms of poor mental health by age group and sex. Among adolescents, the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms above the recommended cut-off on the HSCL-5 scale38 was 10.2% for boys and 21.1% for girls in the 1990s. In the latest survey (2017–2019), the prevalence had changed to 16.5% for boys and 44.4% for girls, that is, particularly large change in the last 10 years for girls (figure 2).

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) and 95% CI for symptoms of anxiety and depression by age group and sex. The HUNT Study, Norway

| Young-HUNT1 HUNT2 (1995–1997) |

Young-HUNT3 HUNT3 (2006–2008) Prevalence 95% CI |

Young-HUNT4 HUNT4 (2017–2019) |

p value for trend |

||

| Prevalence 95% CI | Prevalence 95% CI | ||||

| Adolescents HSCL-5* |

|||||

| Girls | 13–19 | 21.1 (19.9 to 22.3) | 27.3 (26.0 to 28.7) | 44.4 (42.8 to 45.9) | 0.000 |

| Boys | 13–19 | 10.2 (9.3 to 11.1) | 10.6 (9.7 to 11.6) | 16.5 (15.4 to 17.7) | 0.000 |

| Adults HADS depression† | |||||

| Females | 20–29 | 4.2 (3.7 to 4.8) | 4.6 (3.7 to 5.7) | 10.7 (9.5 to 12.0) | 0.000 |

| 30–39 | 6.9 (6.3 to 7.6) | 6.3 (5.5 to 7.2) | 8.9 (7.9 to 10.1) | 0.004 | |

| 40–49 | 9.3 (8.6 to 10.0) | 7.7 (6.9 to 8.5) | 9.0 (8.2 to 10.0) | 0.377 | |

| 50–59 | 12.3 (11.5 to 13.3) | 9.0 (8.3 to 9.9) | 8.4 (7.7 to 9.3) | 0.000 | |

| 60–69 | 14.2 (13.2 to 15.3) | 8.8 (8.0 to 9.7) | 7.4 (6.7 to 8.2) | 0.000 | |

| 70–79 | 17.5 (16.3 to 18.9) | 12.6 (11.4 to 14.0) | 7.6 (6.8 to 8.5) | 0.000 | |

| Males | 20–29 | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.5) | 5.8 (4.5 to 7.4) | 10.2 (8.7 to 11.9) | 0.000 |

| 30–39 | 6.9 (6.2 to 7.6) | 7.3 (6.2 to 8.6) | 11.6 (10.2 to 13.2) | 0.000 | |

| 40–49 | 10.4 (9.7 to 11.2) | 9.0 (8.0 to 10.0) | 10.2 (9.0 to 11.4) | 0.358 | |

| 50–59 | 13.6 (12.7 to 14.6) | 10.5 (9.6 to 11.4) | 9.4 (8.5 to 10.4) | 0.000 | |

| 60–69 | 13.9 (12.8 to 15.0) | 11.1 (10.2 to 12.1) | 8.4 (7.6 to 9.3) | 0.000 | |

| 70–79 | 16.8 (15.4 to 18.2) | 13.7 (12.4 to 15.2) | 10.5 (9.5 to 11.6) | 0.000 | |

| HADS anxiety† | |||||

| Females | 20–29 | 15.5 (14.4 to 16.5) | 19.1 (17.4 to 21.0) | 32.0 (30.1 to 33.9) | 0.000 |

| 30–39 | 17.1 (16.1 to 18.1) | 17.8 (16.5 to 19.2) | 26.7 (25.1 to 28.4) | 0.000 | |

| 40–49 | 17.9 (17.0 to 18.9) | 17.1 (16.0 to 18.2) | 22.1 (20.8 to 23.4) | 0.000 | |

| 50–59 | 18.6 (17.5 to 19.8) | 18.0 (17.0 to 19.1) | 20.4 (19.3 to 21.6) | 0.028 | |

| 60–69 | 18.0 (16.7 to 19.3) | 16.4 (15.4 to 17.6) | 17.9 (16.8 to 19.0) | 0.896 | |

| 70–79 | 17.2 (15.7 to 18.8) | 17.2 (15.8 to 18.8) | 16.2 (15.0 to 17.4) | 0.290 | |

| Males | 20–29 | 11.9 (10.9 to 13.0) | 12.0 (10.2 to 14.2) | 19.0 (17.0 to 21.2) | 0.000 |

| 30–39 | 12.9 (12.0 to 13.9) | 11.4 (10.0 to 12.9) | 18.8 (17.0 to 20.7) | 0.000 | |

| 40–49 | 14.0 (13.2 to 15.0) | 12.5 (11.4 to 13.7) | 16.5 (15.1 to 18.0) | 0.030 | |

| 50–59 | 12.5 (11.6 to 13.5) | 11.7 (10.8 to 12.7) | 15.2 (14.0 to 16.4) | 0.001 | |

| 60–69 | 9.2 (8.3 to 10.2) | 8.5 (7.6 to 9.4) | 11.0 (10.1 to 12.0) | 0.004 | |

| 70–79 | 9.4 (8.2 to 10.6) | 6.5 (5.6 to 7.6) | 8.4 (7.5 to 9.4) | 0.325 | |

*Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 (HSCL-5) cut-off ≥2.

†Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) cut-off ≥8.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of anxiety and depression symptoms measured with Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 (cut-off ≥2), from three decades of adolescents in the Young-HUNT Study.

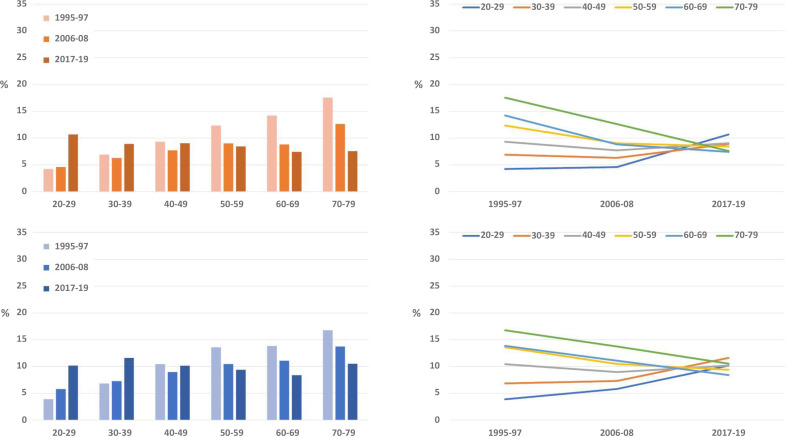

For adults, table 3 shows that an increasing prevalence for depressive symptoms above cut-off with age was observed in both sexes, from around four per cent among young adults 20–29 years and around 17% among older people 70–79 years in 1995–1997 (figure 3). In contrast to this, the highest prevalence among young women (10.7%), and the lowest among the elderly aged 70–79 (7.6%) were observed in the last survey (2017–2019) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence (%) of depression symptoms measured with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-depression (cut-off ≥8) from three decades, the HUNT Study.

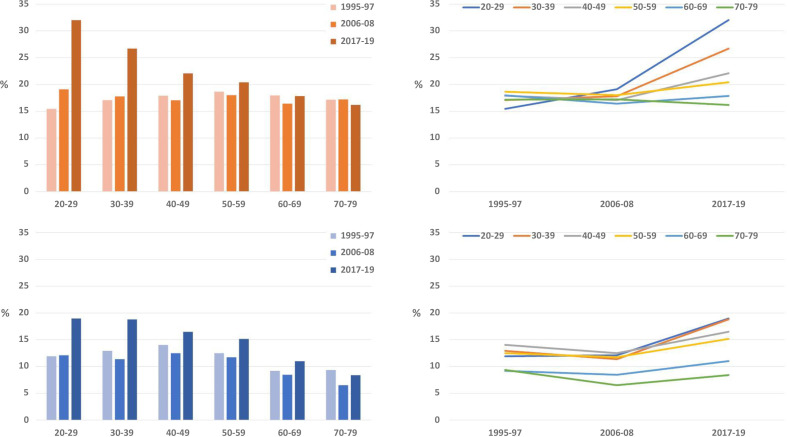

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms above cut-off measured with HADS-A was similar in all age groups in 1995–1997 (table 3); around 10% for men and 17% for women. In the last survey, we observed a markedly higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms for both genders for participants aged 20–39 years (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Prevalence (%) of anxiety symptoms measured with Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-anxiety (cut-off ≥8) from three decades, the HUNT Study.

The negative trends among young adults and the positive trends among older participants shown in figures 3 and 4 were statistically significant in almost all groups (online supplemental appendix table 1).

bmjopen-2021-057654supp001.pdf (33.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

Results from the large Norwegian population-based HUNT Study of more than 170 000 people showed large increases in the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms among adolescents and young adults since the 1990s, especially between 2006–2008 and 2017–2019. These increases were largest among young women, though there were also increases among young men. In contrast, among older adults rates of depressive symptoms declined, and anxiety symptoms remained largely unchanged.

Possible reasons for change

An important question is whether the increases in anxiety and depression symptoms reported were influenced by changes in sociocultural and behavioural attitudes towards anxiety, depression and mental health in general. In recent years, mental health among young people has received increased attention in the Norwegian society. As a result, it may have become easier for young participants to report anxiety and depression symptoms and express emotion in questionnaires. For the adult participants, we have used a different tool than for adolescents (HADS), however, the exact same trend for participants aged 20–39 years as in adolescents was identified. The opposite trend was observed for the elderly. The fact that two different instruments present similar trends among young people in our sample, and the divergent trends by age, supports the validity of our findings. In addition, results are supported by data from the Norwegian health services and prescription databases, clearly demonstrating increasing numbers of individuals either referred for, or in need of treatment for mental illness among young people.41 The increase in reported anxiety and depression symptoms demonstrated in our data, is also accompanied by an increasing number of adolescents in the general population referred to mental health services,42 an increased use of psychotropic drugs in age groups reporting increasing symptoms,43 and an increasing number of young adults in need of social welfare.44 In addition, similar increases in mental health issues in countries such as the USA have been accompanied by concurrent increases in hospital admissions for self-harm behaviours and suicide attempts that cannot be attributed to changes in survey self-reports.45 46 Consistent with the changes we see in our Norwegian data, a clear decline in young people’s happiness and life satisfaction over the last 10 years has been reported as well.34

Thus, taken together, evidence seems to suggest that the observed trends in poorer mental health among young people are real. To determine the causes behind such public health trends is, however, challenging. Younger generations clearly face concerns that have increased in significance and importance throughout the previous few decades. These include worsening climate change, growing social injustice,47 emerging threats to democratic institutions and the propagation of consequences related to the advent of innovative modern technological developments.19 In addition, higher academic pressure reflects the dominant neoliberal political preoccupation with competition.33 When young people’s sense of self-worth is dependent on what they achieve in school, it can also lead to anxiety and depression if they do not achieve expected results.32

Another substantial change in Western societies during the last decade, and which we believe may have great significance, has been in technology use. The tech industry’s strong influence on young people’s behaviour using deliberately manipulative and exploitative strategies may be an important driver of the observed trends among young people in our data.11 Growing use of social media as a daily activity has led to the emergence of ethical concerns related to the management of data.48 Several studies have demonstrated the mechanisms of addiction to electronic devices used to access these digital ecosystems.20 49 Addiction to social networks is a consequence of users’ fear of missing out, feeling that they have an impact on others, and make them feel an instant reward when they publish content about themselves.48 Evidence has shown that heavy users of social media, for example, are twice as likely as light users to be depressed or report lower levels of well-being.11 These effects may be associated with an increase in the prevalence of loneliness seen after 201228 50 and reduced hours of sleep among adolescents.29 30 Some have questioned the suggestion that increased time spent on social media is a leading cause of adverse mental health among young people, with individual data revealing only a weak association between time use and mental health in a longitudinal study.51 However, associations at the individual level may be different from the group-level associations we examine here; even non-users of technology may be impacted by the changes in social interaction caused by technology use.11 The increased acceptance, integration and near-obligatory use of internet-based media technologies to access services and social networks in society increasingly either isolate non-users or force them to conform. Furthermore, as social norms move away from in-person social interaction, even individuals interested in in-person interactions find it increasingly difficult to find others to do so with. Social media is social, not just individual and naturally possesses powerful network effects.27 Thus, it becomes necessary to look further into the political, historical and cultural context in which these behavioural changes unfold.17 52

Among older segments of the population, we see no similar increase in mental health issues over the study period. In fact, our results highlight rather the opposite—improved mental health. Such trends have also been observed in other populations.14 National survey data in Norway shows that social media use follows a consistent age gradient, with younger populations showing considerably more use of social media daily compared with older.53 Older people in Norway benefit from good living conditions with financial security in a generous welfare state54 and good prospects of high life expectancy.55 Older individuals may also benefit from emotional regulation and complex social decision-making, and thus be able to cope with the stress of technological developments in other ways than young people.14 56

Strengths

The HUNT Study collects data from a total population at approximately 10 years intervals, enabling studies of health changes in the population over time.35 36 The invitation/sampling of participants, and methods for measuring mental health, have been conducted using the same methods and instruments in all three surveys included in the present study. Large sample sizes have ensured reliable estimates. Health trends in the county follow both national57 and international western health trends closely.58 The population is stable and relatively homogenous with a low net migration. As part of a national Nordic welfare state, the population recruited is part of a country with a universal public health service and a school system where almost everyone attends the same local schools.

Limitations

Our survey data covered approximately 78% of the total adolescent population and 70%–54% of the total adult population (as the result of a decrease in participation from HUNT2 to HUNT3 among adults). Non-response analyses for adult participants have shown that those who choose not to participate generally have a higher mortality rate, slightly higher prevalence of chronic illness and lower socioeconomic position than participants.59 This may have biased our findings so that unfavourable trends among adolescents are underestimated and favourable trends among adults are overestimated. The study design does not allow for causal inferences.

Relevance

The tech industry’s strong influence on young people’s behaviour has taken place without notable political concern in Norway or other western countries, in line with dominating neoliberal political ideology.18 60 This has allowed the rapid expansion of innovative technologies by commercial and corporate actors to facilitate the exploitation of spheres of society relatively untouched by capitalist interests before the emergence of these technologies. The consequences are, however, not going completely unrecognised, and awareness is growing, in part represented by an emerging discussion and appreciation for addressing the power and influence of commercial61 and corporate determinants of health.62

Our results are in line with results suggesting poorer mental health observed among adolescents and young adults internationally8 9 and, more specifically, in the USA.11 Supporting research shows, additionally, that social media use has significant effects on mental health, particularly in young people.25 The data on both are of great interest to public health policy. The undesirable trend has affected many young people and affected everyday life substantially for large groups in Norway. Based on earlier findings from the HUNT Study, there is reason to forecast that poorer mental health may contribute to an increasing incidence of work-related incapacity in Norway now and in the years to come.6 63

Need for further research and need for action

Our findings highlight the need for further research to find out if some of the reductions in mental health simply may be due to greater awareness of mental health or changes in reporting. It is, furthermore, necessary to investigate the broad range of potential driving factors underlying increased mental health problems in young people. The long-term consequences will be important to follow, to see if the correlation between poorer mental health in adolescents and negative outcomes in adulthood will be as expected based on previous studies.63 Based on what is outlined in this paper, there is every reason to consider policy measures to protect youth and young adults against increasing mental distress. A public health policy is needed that strengthens faith in the future, demonstrating our influence on living conditions and reduced pressure and stress on young people. Experience and evidence from population-based public health and relevant research, provides reason to believe that increased regulation of the tech industry, which has enjoyed relatively few restrictions for decades, will be important moving forward. Governments and individuals could challenge their role in defining the dominant narrative, setting the rules by which trade operates, commodifying knowledge and undermining political, social and economic rights in our society.62 Relevant measures could be, but are not limited to, an enforced age minimum for use of social media and online computer gaming, creating increased accountability for the content published by technology companies and their platforms, regulations to restrict addictive elements of different software and taxation of the industry to obtain funding for relevant public health initiatives. However, of greatest concern is restructuring and regulating the entire economic business model on which many of these tech giants not only depend on for their enormously powerful profits but have also had a central role in developing for the deliberate manipulation and exploitation of its most vulnerable users. Such measures would undoubtedly increase effectiveness through systematic international cooperation. In addition, the effects of climate change and global economic policy and academic pressure as a result of dominant political ideology, also should be further investigated.52

Conclusion

The data from the HUNT Study in Norway indicate a strong increase in anxiety and depression symptoms among adolescents and young adults, and the opposite trend among the elderly. This trend is likely related to significant disruptions in the living conditions of young people in society and behavioural changes in adolescents and young adults, which we suggest are likely driven by major socio-political trends, such as the growth of neoliberal policy, globalisation and an expanding tech industry.21 The results of this study show that is urgently important that health authorities now see the need to implement significant political measures to address the underlying trends in mental health, and their causes, seen in young people.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU, Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Footnotes

Twitter: @steinak

Contributors: SK was the main author, responsible for the overall content as the guarantor for the study, and contributed to the conception and design of the work, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. DAW contributed to interpretation of data, drafting and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. MAK contributed to the conception and design, revising the work critically for important intellectual content, interpretation of data and revising it critically for important intellectual content. VR contributed to the acquisition of data, analyses and interpretation of data and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. KK contributed to acquisition of data, interpretation of data, drafting and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. JMI contributed to acquisition of data, interpretation of data and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. OB contributed to acquisition of data, interpretation of data and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. JT contributed to interpretation of data, drafting and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. ERS contributed to the conception and design of the work, acquisition of data, analyses and interpretation of data, drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and are accountable for all aspects of the work. SK accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The HUNT study is publicly funded, and this paper have no external funding. The funding sources were not involved in the study design; analysis, and interpretation; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The researchers were independent from funders and all authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data used is individual-based sensitive health data that can not be made available without violating the consent and Norwegian law. Data are available upon reasonable request to HUNT Research Centre.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by REK sør-øst C, Norway 196364/2020.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, et al. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007;369:1302–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tollånes MC, Knudsen AK, Vollset SE, et al. Disease burden in Norway in 2016. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2018;138:274. 10.4045/tidsskr.18.0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen AK, Øverland S, Hotopf M, et al. Lost working years due to mental disorders: an analysis of the Norwegian disability pension registry. PLoS One 2012;7:e42567. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, et al. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014;48:606–16. 10.1177/0004867414533834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twenge JM, Farley E. Not all screen time is created equal: associations with mental health vary by activity and gender. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021;56:207–17. 10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myhr A, Anthun KS, Lillefjell M, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in Norwegian adolescents' mental health from 2014 to 2018: a repeated cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 2020;11:1472. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twenge JM. Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Curr Opin Psychol 2020;32:89–94. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol 2019;128:185–99. 10.1037/abn0000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyes KM, Gary D, O'Malley PM, et al. Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:987–96. 10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas ML, Kaufmann CN, Palmer BW, et al. Paradoxical trend for improvement in mental health with aging: a community-based study of 1,546 adults aged 21-100 years. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77:e1019–25. 10.4088/JCP.16m10671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zivin K, Pirraglia PA, McCammon RJ, et al. Trends in depressive symptom burden among older adults in the United States from 1998 to 2008. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1611–9. 10.1007/s11606-013-2533-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129:19–31. 10.1177/00333549141291S206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:427–32. 10.1093/ije/30.3.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostry JD, Loungani P, Furceri D. Neoliberalism: oversold. Finance & development 2016;53:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harari YN. 21 lessons for the 21st century. London: Vintage Books, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuboff S. The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for the future at the new frontier of power. London, New York: Profile Books PublicAffairs, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harari YN. Homo deus: a brief history of tomorrow: random house, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris T. How technology hijacks people’s minds—from a magician and Google’s design ethicist. Medium Magazine 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuture & Creativity . Top 9 trends of global culture during the last 15 years, 2021. Available: https://www.culturepartnership.eu/en/article/top-9-trends-of-the-last-decade [Accessed 8 Feb 2021].

- 24.Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, et al. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:323–31. 10.1002/da.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keles B, McCrae N, Grealish A. A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int J Adolesc Youth 2020;25:79–93. 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korpås JA. Screen time associated to mental health in adolescents: knowledge from a population based study. Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dwyer RJ, Kushlev K, Dunn EW. Smartphone use undermines enjoyment of face-to-face social interactions. J Exp Soc Psychol 2018;78:233–9. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J-H. Longitudinal associations among psychological issues and problematic use of smartphones: a two-wave cross-lagged study. J Media Psychol 2019;31:117–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keyes KM, Maslowsky J, Hamilton A, et al. The great sleep recession: changes in sleep duration among US adolescents, 1991-2012. Pediatrics 2015;135:460–8. 10.1542/peds.2014-2707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med 2017;39:47–53. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hestetun I, Svendsen MV, Oellingrath IM. Sleep problems and mental health among young Norwegian adolescents. Nord J Psychiatry 2018;72:578–85. 10.1080/08039488.2018.1499043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascoe MC, Hetrick SE, Parker AG. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int J Adolesc Youth 2020;25:104–12. 10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cosma A, Stevens G, Martin G, et al. Cross-National time trends in adolescent mental well-being from 2002 to 2018 and the explanatory role of Schoolwork pressure. J Adolesc Health 2020;66:S50–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hellevik O, Hellevik T. Hvorfor ser færre unge lyst på livet? Utviklingen for opplevd livskvalitet blant ungdom og yngre voksne i Norge. [Why are fewer young people looking forward to life? The development for perceived quality of life among young people and younger adults in Norway ]. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Ungdomsforskning 2021;2:104–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:968–77. 10.1093/ije/dys095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmen TL, Bratberg G, Krokstad S, et al. Cohort profile of the young-HUNT study, Norway: a population-based study of adolescents. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:536–44. 10.1093/ije/dys232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmalbach B, Zenger M, Tibubos AN, et al. Psychometric properties of two brief versions of the Hopkins symptom checklist: HSCL-5 and HSCL-10. Assessment 2021;28:617–31. 10.1177/1073191119860910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, et al. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry 2003;57:113–8. 10.1080/08039480310000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. [program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC 2019.

- 41.Hartz I, Skurtveit S, Steffenak AKM, et al. Psychotropic drug use among 0-17 year olds during 2004-2014: a nationwide prescription database study. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:12. 10.1186/s12888-016-0716-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wæhre A, Schorkopf M. Gender variance, medical treatment and our responsibility. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2019;139:178. 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furu K, Hjellevik V, Hartz I. Legemiddelbruk hos barn og unge i Norge 2008-2017. [Drug use in children and young people in Norway 2008-2017]. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaltenbrunner Bernitz B, Grees N, Jakobsson Randers M, et al. Young adults on disability benefits in 7 countries. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:3–26. 10.1177/1403494813496931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercado MC, Holland K, Leemis RW, et al. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001-2015. JAMA 2017;318:1931–3. 10.1001/jama.2017.13317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics 2018;141:2426. 10.1542/peds.2017-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strand BH, Steingrímsdóttir Ólöf Anna, Grøholt E-K, et al. Trends in educational inequalities in cause specific mortality in Norway from 1960 to 2010: a turning point for educational inequalities in cause specific mortality of Norwegian men after the millennium? BMC Public Health 2014;14:1208. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saura JR, Palacios-Marqués D, Iturricha-Fernández A. Ethical design in social media: assessing the main performance measurements of user online behavior modification. J Bus Res 2021;129:271–81. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burr C, Taddeo M, Floridi L. The ethics of digital well-being: a thematic review. Sci Eng Ethics 2020;26:2313–43. 10.1007/s11948-020-00175-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: evidence from three datasets. Psychiatr Q 2019;90:311–31. 10.1007/s11126-019-09630-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coyne SM, Rogers AA, Zurcher JD, et al. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Comput Human Behav 2020;104:106160. 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verhaeghe P. What about me? The struggle for identity in a market-based society. London: Scribe Publications Pty Ltd, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Røgeberg O. Fire av fem nordmenn bruker sosiale medier [Four out of five Norwegians use social media]. Oslo: Statistics Norway, 2018. Available: https://www.ssb.no/teknologi-og-innovasjon/artikler-og-publikasjoner/fire-av-fem-nordmenn-bruker-sosiale-medier [Accessed 13 Apr 2022].

- 54.Thompson S, Cylus J, Evenovits T. Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Europe. Copenhagen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storeng SH, Krokstad S, Westin S, et al. Decennial trends and inequalities in healthy life expectancy: the HUNT study, Norway. Scand J Public Health 2018;46:124–31. 10.1177/1403494817695911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worthy DA, Gorlick MA, Pacheco JL, et al. With age comes wisdom: decision making in younger and older adults. Psychol Sci 2011;22:1375–80. 10.1177/0956797611420301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krokstad S, Westin S. Disability in society-medical and non-medical determinants for disability pension in a Norwegian total county population study. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1837–48. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00409-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) . Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Romundstad P, et al. The HUNT study: participation is associated with survival and depends on socioeconomic status, diseases and symptoms. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:143. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiss D. Round hole, square PEG: a discourse analysis of social inequalities and the political legitimization of health technology in Norway. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1691. 10.1186/s12889-019-8023-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kickbusch I. Addressing the interface of the political and commercial determinants of health. Health Promot Int 2012;27:427–8. 10.1093/heapro/das057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKee M, Stuckler D. Revisiting the corporate and commercial determinants of health. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1167–70. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pape K, Bjørngaard JH, Holmen TL, et al. The welfare burden of adolescent anxiety and depression: a prospective study of 7500 young Norwegians and their families: the HUNT study. BMJ Open 2012;2:1942. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057654supp001.pdf (33.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data used is individual-based sensitive health data that can not be made available without violating the consent and Norwegian law. Data are available upon reasonable request to HUNT Research Centre.