Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to clarify current teaching on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) content in Japanese medical schools and compare it with data from the USA and Canada reported in 2011 and Australia and New Zealand reported in 2017.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Eighty-two medical schools in Japan.

Participants

The deans and/or relevant faculty members of the medical schools in Japan.

Primary outcome measure

Hours dedicated to teaching LGBT content in each medical school.

Results

In total, 60 schools (73.2%) returned a questionnaire. One was excluded because of missing values, leaving 59 responses (72.0%) for analysis. In total, LGBT content was included in preclinical training in 31 of 59 schools and in clinical training in 8 of 53 schools. The proportion of schools that taught no LGBT content in Japan was significantly higher than that in the USA and Canada, both in preclinical and clinical training (p<0.01). The median time dedicated to LGBT content was 1 hour (25th–75th percentile 0–2 hours) during preclinical training and 0 hour during clinical training (25th–75th percentile 0–0 hour). Only 13 schools (22%) taught students to ask about same-sex relations when obtaining a sexual history. Biomedical topics were more likely to be taught than social topics. In total, 45 of 57 schools (79%) evaluated their coverage of LGBT content as poor or very poor, and 23 schools (39%) had some students who had come out as LGBT. Schools with faculty members interested in education on LGBT content were more likely to cover it.

Conclusion

Education on LGBT content in Japanese medical schools is less established than in the USA and Canada.

Keywords: LGBT, medical education, undergraduate, Japan, international comparison

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used a questionnaire that included the same questions as previous studies to compare the quality and quantity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) education in Japanese medical schools with that in the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand.

In addition to the questions used in the surveys in the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand, our questionnaire included items investigating whether the presence of medical students/faculty who had come out and the presence of faculty interested in LGBT education were associated with covering LGBT content.

Unlike a previous study in Japan, we distributed the questionnaire regarding LGBT content in education to all medical schools in the country.

This survey was conducted approximately 3 years after the Australia/New Zealand survey and approximately 9 years after the US/Canada survey; therefore, our study involved the limitation of not being able to make contemporaneous comparisons with these countries.

Because the questionnaire was sent to the dean of the medical school, it may not have been given to a person with an overall understanding of LGBT education in medical schools.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) people are exposed to health inequities. These health disparities are partly attributable to social discrimination. In Japan, no nationwide survey of the size of the LGBT population has been undertaken by the government. However, several surveys have been conducted at the municipal level. A survey conducted in Osaka City, the third largest city in Japan, revealed that 2.7% of respondents identified as LGBT. When individuals who identified as asexual were included, the figure was 3.3%.1 Social discrimination and health disparities against LGBT people have also been reported in Japan. Fifty-eight per cent of LGBT people have been bullied in school,2 and 61.4% of transgender people have reported difficulties finding a job because of their gender identity.3 As for health disparities, for example, gay and bisexual men have a higher rate of attempted suicide than heterosexual men,4 and transgender people have high rates of suicidal ideation.5 Lesbian and bisexual women have high rates of self-harm.6

Furthermore, in Japan, it has been reported that there are barriers for LGBT people to access medical care, and that they are sometimes treated inappropriately in medical settings. More than 40% of transgender people reported that they had unpleasant experiences during medical visits or hesitated to seek medical care.7 A survey of hospital nurse managers reported that more than 30% of hospitals allowed visitation and end-of-life care only to relatives, and partners of the opposite sex, but not to partners of the same sex.8

To eliminate these health disparities, healthcare providers should be equipped with better knowledge, skills and attitudes. A systematic review reported that medical staff and students’ knowledge and attitude towards LGBT patients was improved by education.9 Education may therefore be an important tool in improving medical care for LGBT patients. However, as shown in this review, most of the reports on medical education about LGBT content are mainly from the USA, with limited reports from Asia. Understanding the cultural background is important in developing medical education about LGBT content in East Asian countries, which have different cultural backgrounds from the West.

In Japan, it has been suggested that there are few people who come out, making LGBT people less visible. For example, in a survey of 16 countries conducted by Ipsos, 46% of respondents answered that they had an LGBT person close to them, compared with only 5% of respondents in Japan, the second lowest of the 16 countries.10 Tamagawa also commented that ‘a number of Japanese GLBT scholars and activists attest that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to come out of the closet in Japanese society’ (p 488).11 In Japan, where LGBT people are thus less visible, the revision of the model core curriculum for medical education for the 2016 academic year (2017) was the first version to include a learning goal about being able to ‘explain gender formation, sexual orientation, and ways of consideration for gender identification’ (p 43).12 However, there are still no guidelines about what and how to teach LGBT-related content in medical education in Japan. Epidemiological studies are necessary to look at the current situation in detail and compare it with countries where education is already advanced. However, there is only one report in English describing the status of training on LGBT content in medical schools in Japan.13 It had a low response rate and did not ask for details about the content of the education without direct comparison by survey data to other countries. Our study is the first attempt of which we are aware to survey the quantity and quality of education on LGBT content in Japanese medical schools and compare the result with the data from other countries. We used a questionnaire developed for a previous study in the USA and Canada14 and subsequently used in a study in Australia and New Zealand15 and compared the results with data from those previous studies.

Methods

Participants and study setting

Questionnaires were mailed to the 82 deans of the medical schools in Japan between July 2018 and January 2019. The aim and importance of our study were announced in the journal Medical Education Japan in April 2018.16 We asked each dean to complete the questionnaire, involving the director of education and/or relevant faculty members when necessary.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire consisted of 18 questions, including 13 drawn from Obedin-Maliver et al14 and translated into Japanese with permission from the author and the American Medical Association through the Copyright Clearance Center (Copyright 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved).

Five new questions were also included: (1) the type of school (public or private/others), (2) whether any medical students had come out as LGBT, (3) whether any faculty members had come out as LGBT, (4) whether any faculty members were interested in education on LGBT content, and (5) who completed the questionnaire.

The primary outcome was hours dedicated to teaching LGBT content in each medical school. The secondary outcomes were: teaching methods, the extent to which LGBT health areas are taught, the evaluation methods of LGBT-related teaching and strategies to increase time devoted to education of LGBT content.

Data collection process

Data were collected between July 2018 and January 2019. If there was no response by the due date, we mailed the questionnaire twice more and contacted the school by telephone.

If schools did not wish to participate, we asked them to return the blank questionnaire. To confirm which universities had responded, the university name was included on the response envelope. The divisional clerk, who was not involved in the research, opened the envelopes and kept the answer sheets separately. The name of the university therefore could not be linked to the answers, and the completed questionnaires were treated as anonymous. The questionnaires included details of these processes. The questionnaire included information about the purpose of the study and how the answers would be used. Questionnaire completion was considered to show consent to participate in the study.

Data analysis

Each question was analysed excluding missing values. We compared the proportions of medical schools that taught each LGBT topic between Japan and the USA and Canada14 using Fisher’s test. This was also used to identify the statistical significance of the relationships between factors and teaching on LGBT content in Japan. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test the significance of difference in hours spent teaching LGBT content between public and private/other schools. Testing excluded any answers indicating ‘declined to answer’. All statistical analyses used Stata V.16.0.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Results

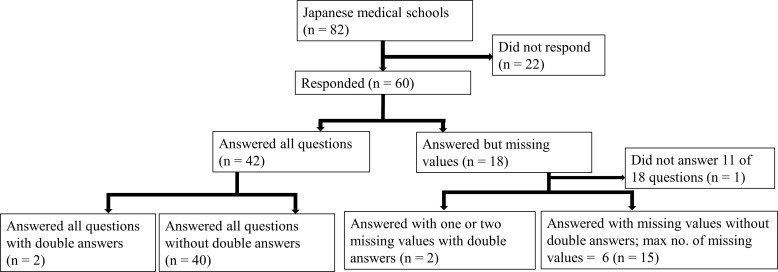

In total, 60 of the 82 schools (73.2%) responded, and 42 answered all the questions. Four schools provided double answers to one question. We removed one respondent who did not answer 11 of 18 questions, leaving responses from 59 schools (72.0% of Japanese medical schools) for analysis. The remaining respondents had no more than six missing answers and were included in the analysis (figure 1). Two researchers checked the double answers and agreed how to combine them.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of respondent selection.

Only 15 of the 59 deans completed the questionnaire themselves. In 36 schools, the respondents were the directors of education, 11 were completed by obstetrician-gynaecologists, 8 by psychiatrists, 8 by urologists and 24 by others (eg, other specialties or office workers). Of the 59 schools, 28 were public, 27 were private or others and 4 schools did not answer this question.

Education on LGBT content

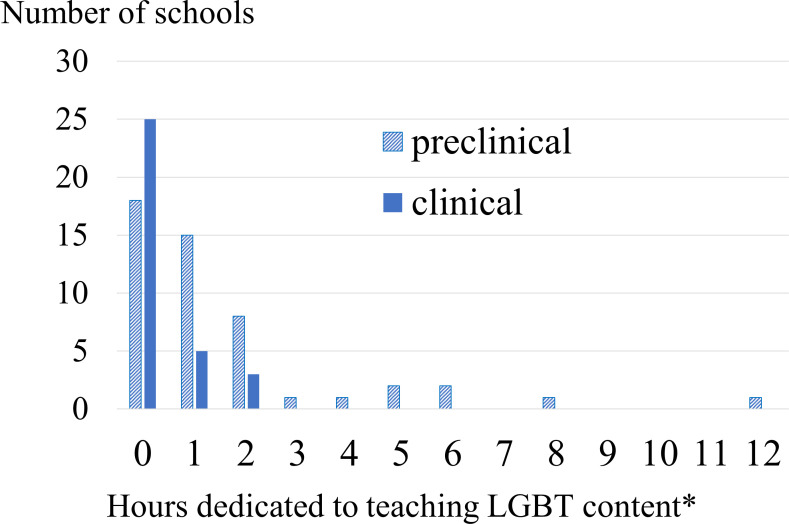

In total, 31 of the 59 schools (52.5% of respondents) included LGBT content in preclinical training, 18 (30.5%) did not and 10 (16.9%) did not know how many hours were spent. For the 49 schools that provided this information for preclinical training, the median (25th–75th percentiles) and mean (±SD) hours were 1 hour (0–2 hours) and 1.6 (±2.4) hours (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hours dedicated to teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) content in Japanese medical schools. *The numbers after the decimal point were rounded up.

Only 8 of 53 schools (15.1% of respondents) included LGBT content during clinical training, 25 schools (47.2%) did not cover it and 20 (37.7%) did not know. The median (25th–75th percentiles) and mean (±SD) hours of the 33 schools were 0 (0–0) hour and 0.3 (±0.6) hour (figure 2).

In total, 33 schools (55.9% of respondents) provided information about hours spent on teaching LGBT content across the whole curriculum. The median (25th–75th percentiles) and mean (±SD) were 0 (0–2) hours and 1.4 (±2.4) hours. Six schools provided no information about clinical training time, resulting in fewer schools for analysis of total time. The median and mean total time were therefore shorter than the preclinical time.

There was no statistically significant relationship between type of school (public or private/other) and teaching about LGBT content (Fisher’s exact test, preclinical p=0.38, clinical p=0.65, total p=0.24). The time spent in preclinical and clinical training was also not significantly different between public and private/other schools (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p=0.19, p=0.76).

In total, 51 schools provided information about whether their curricula covered 16 LGBT-related topics. Of these, 15 (29.4%) covered at least half the topics. For each topic, the number of schools that responded that it was taught in the required or elective curriculum and that it did not need to be taught is summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Proportion of schools teaching particular LGBT topics in the required or elective curriculum and answering ‘coverage not needed’ about each topic

| Available in required or elective curriculum (n=51) |

Coverage not needed (n=53) |

|

| Disorders of sex development (DSD)/intersex | 23 (45%) | 2 (4%) |

| HIV in LGBT people | 20 (39%) | 2 (4%) |

| Gender identity | 19 (37%) | 3 (6%) |

| Sexual orientation | 17 (33%) | 6 (11%) |

| Coming out | 16 (31%) | 6 (11%) |

| Transitioning | 16 (31%) | 3 (6%) |

| Sex reassignment surgery (SRS) | 16 (31%) | 2 (4%) |

| Sexually transmitted infections (not HIV) in LGBT people | 15 (29%) | 2 (4%) |

| Barriers to accessing medical care for LGBT people | 14 (27%) | 5 (9%) |

| Mental health in LGBT people | 14 (27%) | 5 (9%) |

| LGBT adolescent health | 7 (14%) | 5 (9%) |

| Body image in LGBT people | 7 (14%) | 6 (11%) |

| Alcohol, tobacco or other drug use among LGBT people | 5 (10%) | 7 (13%) |

| Chronic disease risk for LGBT populations | 5 (10%) | 4 (8%) |

| Safer sex for LGBT people | 4 (8%) | 6 (11%) |

| Unhealthy relationships among LGBT people | 0 (0%) | 5 (9%) |

These items were taken from questions 8 and 9 from the questionnaire by Obedin-Maliver et al.14

LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

In total, 37 of 57 respondents (64.9%) did not evaluate teaching about LGBT content. The most frequent form of evaluation was a written examination (16 of 57, 28.1%). No schools used faculty-observed patient interactions or evaluation by patients, and only one used peer-to-peer evaluations and evaluation by standardised patients. The free text responses included answers such as reaction papers, reports, presentations and oral examinations.

The strategies that could be used to increase training on LGBT content are shown in table 2. The most common was ‘Faculty willing and able to teach LGBT-related curricular content’.

Table 2.

Possible strategies to increase LGBT-specific content* (n=50)

| Respondents n (%) |

|

| Faculty willing and able to teach LGBT-related curricular content | 29 (58.0) |

| Curricular material coverage required by accreditation bodies | 24 (48.0) |

| Questions based on LGBT health/health disparities on national examinations | 20 (40.0) |

| More time in the curriculum to be able to teach LGBT-related content | 20 (40.0) |

| Curricular material focusing on LGBT-related health/health disparities | 16 (32.0) |

| Increased financial resources | 10 (20.0) |

| More evidence-based research regarding LGBT health/health disparities | 8 (16.0) |

| Logistical support for teaching LGBT-related curricular content | 6 (12.0) |

| Methods to evaluate LGBT curricular content | 6 (12.0) |

| Don’t know | 9 (18.0) |

| Other | 3 (6.0) |

These items were taken from question 13 from the questionnaire by Obedin-Maliver et al.14

*To focus on what would help in future, we specifically asked about future strategies rather than current success strategies.

LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

Original questions

The results of our new questions are shown in table 3. There were no relationships between whether any students or faculty members had come out and teaching about LGBT content (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.31, p=0.29). The schools that clearly indicated that they had faculty members interested in education on LGBT content were more likely to cover it (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.01).

Table 3.

Responses to our original question (n=59)

| Were/are there | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) | Declined to answer (%) |

| Any students who had come out as LGBT? | 23 (39.0) | 10 (17.0) | 20 (33.9) | 6 (10.2) |

| Any faculty members who had come out as LGBT? | 7 (11.9) | 11 (18.6) | 37 (62.7) | 4 (6.8) |

| Faculty members interested in education on LGBT content? | 27 (45.8) | 1 (1.7) | 30 (50.9) | 1 (1.7) |

LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

Comparison between Japan, the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand

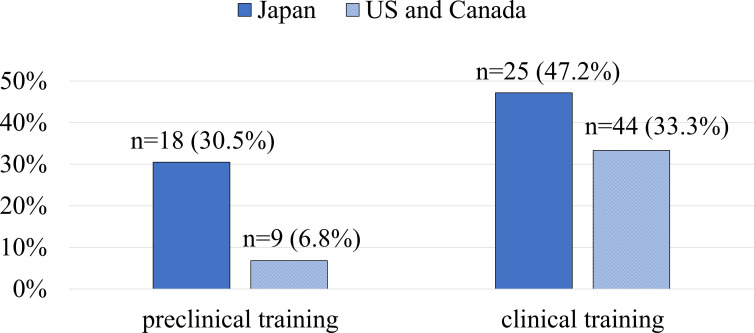

Only 9 of 132 schools (6.8%) in the USA and Canada did not include LGBT content in preclinical training.14 The proportion of schools not teaching it in Japan (18 of 59 schools, 30.5%) was therefore much higher (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.01) (figure 3). Even if all the schools that responded ‘not known’ had provided education on LGBT content during preclinical training in Japan, the proportion of schools not teaching about LGBT content would still be significantly higher in Japan than the USA and Canada (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.01). In the USA and Canada, 44 of 132 schools (33.3%) did not include LGBT content during clinical training,14 which was significantly less than in Japan (25 of 53 schools, 47.2%) (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.01) (figure 3). There were also significant differences in both preclinical and clinical training when schools that answered ‘don’t know’ were excluded (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.01). We were unable to statistically compare our data with Australia and New Zealand because there was no information about how many schools there did not teach about LGBT content.15

Figure 3.

Proportion of schools that did not teach about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) content at all. The data of the USA and Canada were quoted from Obedin-Maliver et al.14

In the USA and Canada, the median time (25th–75th percentiles) spent on LGBT content during preclinical and clinical training was 4 (2–6) and 2 (0–3) hours,14 longer than the 1 (0–2) and 0 (0–0) hours in Japan. The study in Australia and New Zealand did not provide the median hours.15

The detailed comparison between Japan, the USA/Canada14 and Australia/New Zealand15 is shown in table 4. There were too few data from Australia and New Zealand for detailed statistical comparisons.

Table 4.

Comparison of education on LGBT content between Japan, the USA and Canada, and Australia and New Zealand

| Japan | USA and Canada14 | Australia and New Zealand15 | ||

| Number of responders/total number of schools (proportion) | 59/82 (72%) | 132/176 (75%) | 15/21 (71%) | |

| Methods of teaching LGBT content | n (proportion) | |||

| LGBT-specific content in the required preclinical curriculum† | Interspersed | 19 (32.8%) | 88 (66.7%)* | 9 (60.0%) |

| Discrete modules | 11 (19.0%) | 32 (24.2%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Lectures or small-group sessions in the required clinical curriculum‡ | 12 (20.3%) | 79 (59.8%)* | 2/1¶¶ (13.3%/6.7%) | |

| Clinical clerkship site that is specifically designed to facilitate LGBT patient care§ |

Required clerkship | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (5.3%) | 5*** (33.3%) |

| Elective clerkship | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (9.1%)** | 7*** (46.7%) | |

| Faculty development for teaching about LGBT health¶ | 5 (8.5%) | 27 (20.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Coverage of LGBT content | n (proportion) | |||

| Asking about same-sex relations when obtaining sexual history** | 13 (22.0%) | 128 (97.0%)* | 12 (80.0%) | |

| Teaching difference between behaviour and identity†† | 17 (28.8%) | 95 (72.0%)* | 10 (66.7%) | |

| At least half of 16 LGBT-related topics covered in elective or required curriculum‡‡ | 15 (29.4%) | 99 (75.0%)* | – | |

| Evaluation of coverage of LGBT content (very poor/poor)§§ | 45 (79.0%) | 34 (25.8%)* | 3 (20.0%) | |

Items on methods of teaching LGBT content and coverage of LGBT content were cited from or corresponding to questions 2–5, and 6, 7, 8 and 10 of the questionnaire by Obedin-Maliver et al.14

*P<0.01; **p<0.05 for comparison of the proportions of schools that answered yes between Japan and USA/Canada.

†Number of respondents answering ‘Do not know’/missing value among Japanese responses: 3/1

‡11/0

§0/0

¶4/0

**17/0

††10/0

‡‡0/8

§§3/2

¶¶Two schools had lectures and one had small-group sessions. Sanchez et al asked separately about lectures and small-group sessions.15

***Two schools had clinical rotation site as a required clinical rotation, four as an elective and three as both.15

LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender.

Discussion

This survey was the first attempt to compare education about LGBT content in medical schools in Japan with other countries. A much higher proportion of schools did not teach about LGBT content in Japan than in the USA and Canada. The coverage of LGBT topics was also much lower in Japan than in the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand. Faculty members interested in teaching LGBT content could be important in increasing its coverage in medical education.

In total, 31 of 59 schools said they taught about LGBT content. In contrast, a previous study by Yamazaki et al reported that only 22 of 37 schools provided lectures or workshops on sexual and gender minorities (SGM) in Japan.13 This is because the methodology in selecting target schools was different from ours, which resulted in the longer lecture time (median 130 min) than ours. In Yamazaki et al’s study, one faculty member was first selected from each of 80 medical schools based on a list of a medical education organisation. Next, double postcards were sent to each of the 80 selected faculty members asking them to refer a key person who could provide accurate information about lectures on SGM in their medical schools. Among 47 schools for which postcards were returned, 43 were considered eligible for the survey. Finally, the second questionnaire about lectures on SGM was sent, and 37 schools responded. Thus, the final response rate was 46.3% (37/80).13 Accordingly, the current study has the strength of having a better response rate than that of Yamazaki et al. Both our study and that of Yamazaki et al13 suggested that the time spent teaching about LGBT content is significantly lower in Japan than in the USA and Canada. Our study also showed that a much higher proportion of schools in Japan do not include LGBT content during either preclinical or clinical training than in the USA and Canada.14 Nine years have passed since the survey in the USA and Canada,14 but the curricula in Japan are still less established.

The quality of education on LGBT content was also lower in Japan than in the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand. Some topics were not considered to be necessary by some Japanese respondents. Biomedical topics such as HIV and disorders of sex development (DSDs) were more likely to be taught than social topics such as unhealthy relationships, safer sex and substance abuse. Although teaching about DSDs is important, it is not a substitute for teaching LGBT content. The term LGBTI is sometimes used to include intersex in LGBT in Japan,17 whereas DSDs refer to a wide range of congenital conditions, not sexual orientation or gender identity. We believe that the lack of educational guidelines on LGBT content means that there has been little discussion about what should be taught, resulting in lack of acknowledgement of the importance of social problems among LGBT people. In contrast, in the USA, the guideline for medical education from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) summarised the health disparities of individuals who are LGBT, gender non-conforming or born with DSD, including social issues, and provided professional competency objectives to improve healthcare for those people.18

Additional questions in our survey were designed to explore the factors that promote LGBT education. A study in the USA and Canada found that East Asian medical students were less likely to come out about their sexual identity than white students,19 so we assumed that sexuality would also tend to be hidden in medical schools in Japan as well. We hypothesised that openly LGBT students or staff might stimulate interest. Of respondent schools, 39% had students who had come out as LGBT, which was more than we expected. However, we found no relationship between teaching time and whether there were LGBT staff or students who came out. It is possible that staff or students coming out may be considered a single case, not a common issue, and therefore not result in changes in educational policy in the school.

The reasons why LGBT-related education in Japan is so much worse in both quantity and quality may be both sociocultural and medical-educational. Socioculturally, there are no antidiscrimination laws regarding sexual orientation or gender identity, and same-sex marriages have not been approved in Japan. Cultures and social systems that protect the rights of LGBT people may therefore be less mature in Japan. This could make it difficult for LGBT people to come out. In medical settings, 58% of LGBT people who accessed medical services for mental health issues did not disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity to staff.20 It may therefore be hard for healthcare professionals to identify LGBT patients as such. However, the movement for the rights of LGBT people in Japan is slowly making progress. For example, there is a growing movement at the local government level to issue certificates for same-sex partnerships. Medical institutions are also beginning to provide support for LGBT people. For example, Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo established a working group in 2021 to consider and respond to patients, families and staff regarding sexual orientation and gender identity, and has started activities such as providing learning opportunities for medical staff and a sexual orientation and gender identity consultation service.21

From a medical education perspective, Yamazaki et al reported that the most common reason for not teaching LGBT content in Japanese medical schools was unavailability of suitable instructors.13 In our study, the most popular future strategy for increasing the time on LGBT content was ‘Faculty willing and able to teach LGBT-related curricular content’. We found that schools with faculty members interested in education on LGBT content were more likely to cover this topic. We therefore believe it is essential to provide more opportunities for faculty members to acquire the skills to teach about LGBT issues. Yamazaki et al recommended the following six steps to promote medical education on SGM: engaging appropriate stakeholders, developing a textbook or educational guide for SGM education and developing a diverse curriculum team for each medical school, as well as conducting faculty development, curriculum development and curriculum evaluation.13 We believe that all of these steps are necessary in Japan. Our study highlighted the importance of the third step ‘diverse curriculum team for each medical school’ and the fourth step ‘conducting faculty development’. In Japan, although workshops have been held to devise and implement education about LGBT content in medical education courses, such meetings are not conducted on a continuous basis. Accessible online courses could potentially provide valuable opportunities for more educators in Japan to learn about teaching LGBT content, such as those offered by Stanford Medicine.22 The current results also revealed that one school in Japan had made outstanding progress, spending 12 hours on LGBT education. It would be useful to share information about how this school started and evolved their teaching, so that schools who are not currently teaching LGBT content at all can start teaching it. There is also an urgent need in Japan to develop guidelines for medical education on LGBT content. In addition to education provided by each medical school, internet resources such as AAMC material can be used to provide opportunities for all medical students in Japan to learn LGBT content.23

To the best of our knowledge, no previous survey has examined the current status of postgraduate education for physicians on LGBT issues in Japan. Although a small number of lectures and workshops have recently been held in the level of academic society,24 25 the opportunities for physicians to learn about LGBT content after graduation are still limited. Therefore, it is important to provide opportunities for education on LGBT content in undergraduate education.

The inadequacy of medical education probably reflects the current state of medical practice in Japan. To reduce health disparities among LGBT people, it is necessary to examine whether LGBT people are being properly cared for in medical settings in countries where LGBT is invisible, such as Japan, as well as improving medical education.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, a high response rate was considered essential to enable comparisons with previous studies, so we actively followed up questionnaires, which increased the response rate from 47.6% after the first mail. However, the final response rate was just 73.2% (60 of 82 schools) which was lower than the 85.2% (150 of 176 schools) in the USA and Canada.14 The results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Second, we calculated the proportion of schools for each question excluding missing values. The studies in the USA and Canada14 and in Australia and New Zealand15 both used listwise case deletion. Using this method, the proportion of schools including LGBT content in preclinical and clinical training decreased from 52.5% (31 of 59 schools) and 15.1% (8 of 53 schools) to 35.7% (15 of 42 schools) and 11.9% (5 of 42 schools), an even bigger difference with the USA and Canada. The median (25th–75th percentiles) and mean (±SD) time were 1 (0–1.2) hour and 1.4 (±2.5) hours during preclinical training, and 0 (0–0) hour and 0.25 (±0.6) hour during clinical training, which were very similar to our previous figures.

Third, there were some double answers for one question. This may be because the questionnaire had been given to individual departments rather than a key faculty member aware of the overall education curriculum. It is therefore not clear whether the responses accurately reflected the current situation. However, this confusion probably reflects a lack of coordinated training on LGBT content.

Fourth, the survey in the USA and Canada used as a comparison was conducted in 2009–2010,14 approximately 9 years before the current study. In 2014, after this study was conducted, the AAMC published practical, detailed and evidence-based recommendation for educational curricula on LGBT content.18 Furthermore, in 2015, same-sex marriage was legalised across the USA. Over the past 10 years, various attempts and advances in medical education on LGBT content have been reported from the USA and Canada.26 27 Considering these developments, the gap between Japan and the USA and Canada may currently be expanding.

Conclusions

The median time given to LGBT content during preclinical training was 1 hour, and 30.5% of respondents did not include any time. During clinical training, the median time was 0 hour, only 15.1% of respondents included dedicated time and 47.2% did not cover it at all. The coverage of LGBT topics in medical education was much lower in Japan than in the USA/Canada and Australia/New Zealand. To promote education about LGBT content, it is necessary to train faculty members to be able to teach these topics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Osamu Fukushima for his help in distributing our questionnaire. We also thank Ms Chikako Mori, the clerk in our division, for her support, and Melissa Leffler, MBA, and Benjamin Knight, MSc, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: EY designed the study, was primarily responsible for data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. MM designed the study, contributed to the interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript. FO interpreted the results and reviewed the manuscript. All coauthors reviewed and approved the article prior to submission. EY is the guarantor of the work and accepts full responsibility for the presented content.

Funding: This study was supported by the Jikei University Research Fund for Graduate Students.

Disclaimer: The sponsor of this study had no role in the study design; the study conduct including collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the manuscript preparation; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: MM received lecture fees and lecture travel fees from the Centre for Family Medicine Development of the Japanese Health and Welfare Co-operative Federation. MM is an adviser of the Centre for Family Medicine Development Practice-Based Research Network and a programme director of the Jikei Clinical Research Program for Primary Care. MM’s son-in-law worked at IQVIA Services Japan K.K., which is a contract research organisation and a contract sales organisation. MM’s son-in-law works at Syneos Health Clinical K.K., which is a contract research organisation and a contract sales organisation. EY is a former trainee of the Jikei Clinical Research Program for Primary Care.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. No additional data are available because consent for publication of raw data was not obtained.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine for Biomedical Research (ref number 30-042(9063)).

References

- 1.Hiramori D, Kamano S. Asking about sexual orientation and gender identity in social surveys in Japan: Findings from the Osaka city residents’ survey and related preparatory studies. Journal of Population Problems 2020;76:443–66. 10.31235/osf.io/w9mjn [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hidaka Y. Reach Online 2016 for Sexual Minorities [In Japanese]. Available: https://health-issue.jp/reach_online2016_report.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 3.NPO Nijiiro Diversity . Center for Gender Studies at International Christian University. niji VOICE 2018. [In Japanese]. Available: https://nijibridge.jp/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/nijiVOICE2018.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 4.Hidaka Y, Operario D, Takenaka M, et al. Attempted suicide and associated risk factors among youth in urban Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008;43:752–7. 10.1007/s00127-008-0352-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terada S, Matsumoto Y, Sato T, et al. Suicidal ideation among patients with gender identity disorder. Psychiatry Res 2011;190:159–62. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hidaka Y. LGBT health issues (2) Bullying victimization, truancy, self-harm, and suicide attempts in school-aged children[In Japanese]. The journal of therapy 2020;102:1432–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaneko N, Asanuma T, Hirao S, et al. Current status of access to healthcare for gender identity disorder/gender dysphoria/transgender people [In Japanese], 2020. Available: teamrans.jp/pdf/tg-gid-tg-research-2020.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 8.Sambe M. Survey of nursing managers on dealing with LGBT patients [In Japanese], 2019. Available: researchmap.jp/multidatabases/multidatabase_contents/download/259573/22c639ed26cf64e8c59db15983d58854/20506?col_no=2&frame_id=498252 [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 9.Sekoni AO, Gale NK, Manga-Atangana B, et al. The effects of educational curricula and training on LGBT-specific health issues for healthcare students and professionals: a mixed-method systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21624. 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ipsos. Same-sex marriage: Citizens in 16 countries assess their views on same-sex marriage for a total global perspective: Global@dvisor. Available: www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/news_and_polls/2013-06/6151-ppt.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 11.Tamagawa M. Coming out of the closet in Japan: an exploratory sociological study. J GLBT Fam Stud 2018;14:488–518. 10.1080/1550428X.2017.1338172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology . Model core curriculum for medica education in Japan, AY 2016 revision., 2017. Available: https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2018/06/18/1325989_30.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2021].

- 13.Yamazaki Y, Aoki A, Otaki J. Prevalence and curriculum of sexual and gender minority education in Japanese medical school and future direction. Med Educ Online 2020;25:1710895. 10.1080/10872981.2019.1710895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011;306:971–7. 10.1001/jama.2011.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez AA, Southgate E, Rogers G, et al. Inclusion of Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex health in Australian and New Zealand medical education. LGBT Health 2017;4:295–303. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida E, Matsushima M. The education on LGBT contents at medical schools in Japan [In Japanese]. Med Educ Japan 2018;49:166–66. 10.11307/mededjapan.49.2_166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeo H. Sex education tips for obstetricians and gynecologists to know. DSDs: a new understanding and sex education of differences of sex development (disorders of sex development) [In Japanese]. Obstetrical and gynecological practice 2021;70:89–94. 10.18888/sp.0000001605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of American Medical Colleges . Implementing curricular and institutional climate changes to improve health care for individuals who are LGBT, gender Nonconforming, or born with DSD: a resource for medical educators. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2014Available. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/129/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansh M, White W, Gee-Tong L, et al. Sexual and gender minority identity disclosure during undergraduate medical education: "in the closet" in medical school. Acad Med 2015;90:634–44. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidaka Y. LGBT health issues (1) Mental health and consultation status [In Japanese]. The journal od therapy 2020;102:1272–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juntendo University . Juntendo News. Press Release. Juntendo University Hospital opened "SOGI consultation service" that takes diverse sexualities into consideration, so that patients who come to the hospital can receive treatment without concerns about their sexuality.; 2021[In Japanese]. Available: https://www.juntendo.ac.jp/news/20211111-01.html [Accessed 23 Dec 2021].

- 22.Stanford Medicine . Teaching LGBTQ+ health. Available: https://mededucation.stanford.edu/courses/teaching-lgbtq-health/ [Accessed 22 Dec 2021].

- 23.Association of American Medical Colleges . AAMC videos and resources about LGBT health and health care. Available: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/lgbt-health-resources/videos [Accessed 22 Dec 2021].

- 24.Japanese Society of Gender Identity Disorder. Expert training [In Japanese]. Available: http://www.okayama-u.ac.jp/user/jsgid/expert.html [Accessed 22 Dec 2021].

- 25.Japan Primary Care Association . The 18th Continuing Professional Development Autumn Seminar. A practical course on ther care of LGBT people for primary care physicians [In Japanese]. Available: https://www.primary-care.or.jp/seminar_c/20210919/pro.html#28 [Accessed 22 Dec 2021].

- 26.Nowaskie DZ, Patel AU. How much is needed? Patient exposure and curricular education on medical students' LGBT cultural competency. BMC Med Educ 2020;20:490. 10.1186/s12909-020-02381-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nolan IT, Blasdel G, Dubin SN, et al. Current state of transgender medical education in the United States and Canada: update to a scoping review. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2020;7:238212052093481. 10.1177/2382120520934813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. No additional data are available because consent for publication of raw data was not obtained.