Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to describe whether adolescent and young adult patients truthfully disclose sexual activity to providers during a sexual history and explore associations between disclosure and receipt of recommended services.

Methods:

Data from the 2018 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior were used to describe self-reported disclsoure of sexually active 14- to 24-year-olds who had a health care visit in the previous year where a sexual history was taken (n = 196). We examined bivariate associations between disclosure and age, race/ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, and receipt of sexual health services.

Results:

Most (88%) respondents reported telling their provider the truth about sexual activity. A higher proportion of the younger adolescents (14- to 17-year-olds) did not disclose compared with the 18- to 24-year-old respondents (25.4% vs 3.9%; p < .001). A higher proportion of patients who disclosed reported having a sexually transmitted disease test (69.6% vs 26.7%; p < .001); being offered a sexually transmitted disease test (44.3% vs 4.5%; p < .001); and being asked by providers about number of partners (54.3% vs 15.4%; p < .01).

Conclusions:

Most young patients disclose their sexual history to their provider, but younger patients might be less likely to do so. Positive patient-provider relationships may encourage disclosure of sexual activity and support receipt of indicated sexual and reproductive health services.

Keywords: Sexual history, Adolescent sexual health, Adolescent clinical services, Patient—provider relationship

Professional medical organizations recommend providers elicit a patient’s sexual history during clinic visits to ensure receipt of appropriate sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services [1–3]. Despite these recommendations sexual history taking is not a routine provider practice, with providers reporting barriers such as their own discomfort, patient embarrassment, time constraints, and perceived patient dishonesty [4–7]. Little is known about the latter, which may be particularly relevant for adolescent patients who report confidentiality concerns [8]. We conducted an exploratory study to (1) describe whether sexually active adolescents and young adults (AYA) disclose their sexual activity to providers; (2) identify correlates of disclosure; and (3) examine associations between disclosure and receipt of SRH services for sexually active AYA.

Methods

Data are from the 2018 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, a U.S. nationally representative probability survey of adolescents and adults, sampled from the Internet-based Ipsos KnowledgePanel. The Institutional Review Board of the Human Subjects Office at Indiana University-Bloomington approved all study protocols (#141211166). Because of a limited analytic sample size for our research question and because the topic is exploratory and not intended to produce generalizable estimates, we used unweighted data. Respondents reporting a health care visit in the previous year (n = 1,086) who indicated their doctor inquired about sexual activity (n = 585) were then asked, “What did you say?”; response options were (1)“I said I am sexually active, which was true”; (2) “I said I am sexually active, which was not true”; (3)“I said I am not sexually active, which was true”; and (4)“I said I am not sexually active which was not true.” For respondents aged 14–24 years who indicated they were sexually active by choosing response option 1 or 4 (n = 196), we calculated the prevalence of disclosure. Using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test when cells included fewer than five responses, we measured bivariate associations between disclosure and age (14–17 years vs. 18–24 years), race/ethnicity (white, non-Hispanic vs. black/Hispanic/Other), gender (male vs. female), and sexual identity (straight/heterosexual vs. gay/lesbian/bisexual). We also examined bivariate associations between disclosure and patient agreement with statements about their provider (perceived comfort, trust that provider will preserve confidentiality, gave accurate information, and did not judge) as well as receipt of SRH services: being offered a sexually transmitted disease (STD) test at clinic visit; ever having an STD test; patient—provider discussions about birth control, STD prevention, pregnancy prevention, or condom use; and being asked about number of partners, sexual identity, oral sex, and anal sex.

Results

One third (34.2%) of the analytic sample (n = 196) were aged 14–17 years, 50.0% were white/non-Hispanic, 66.8% female, and 86.1% were straight/heterosexual. Most respondents (88.8%, n = 174) reported disclosing their sexual activity. A higher proportion of 14- to 17-year-olds reported not disclosing compared with those aged 18–24 years (25.4% vs. 3.9%; p < .001). There were no significant differences in disclosure by race/ethnicity, gender, or sexual identity.

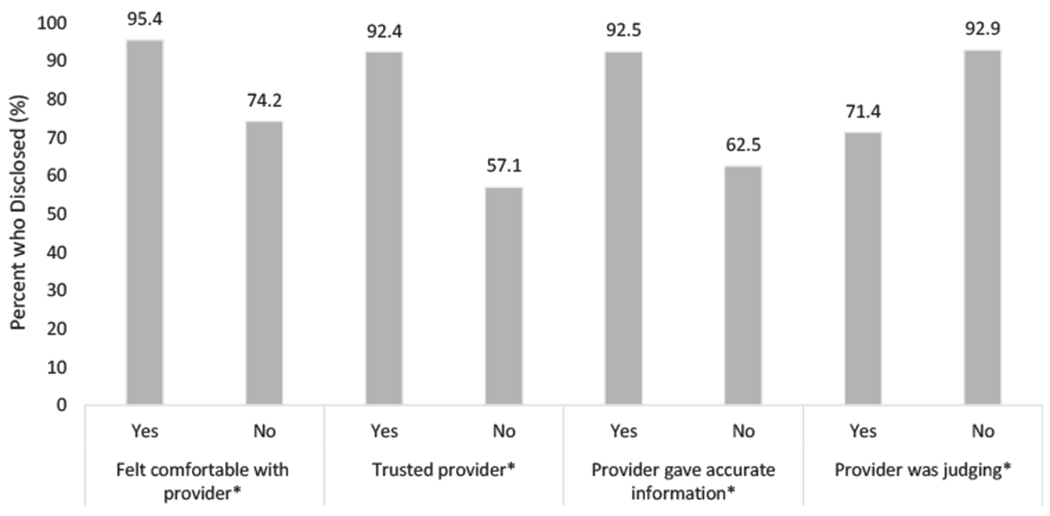

Figure 1 illustrates associations between adolescents’ disclosure and patient—provider dynamics. Prevalence of disclosure was higher among those who were comfortable with their provider compared with those not comfortable (95.4% vs. 74.2%; p < .001), trusted their provider compared with those who did not (92.4% vs. 57.1%; p < .05) and believed their provider gave them accurate information compared with those who did not (92.5% vs. 62.5%; p < .05). Fewer respondents reported disclosure if they felt judged by their provider compared with those who did not (71.4% vs. 92.9%; p < .05).

Figure 1.

Percent of sexually active 14- to 24-year-olds with a past year clinic visit (n = 196) who disclosed their sexual activity by patient—provider dyanmicsa.

aAmong those who said yes to “Did you and your healthcare provider(s) discuss sex or sexual health?” *p < .05.

Disclosure was associated with receipt of various SRH services (Table 1). Compared with respondents who did not disclose, a higher proportion of those who did reported ever having an STD test (69.6% vs. 26.7%; p < .01); being offered an STD test at their last visit (48.4% vs. 5.0%; p < .01); discussing pregnancy prevention (72.7% vs. 35.0%; p < .001) and condoms (83.7% vs. 53.8%; p < .01) with their provider; and being asked by providers about penile-vaginal intercourse (63.6% vs. 23.1%; p < .01), number of partners (58.8% vs. 16.7%; p < .01), and painful sex (33.0 vs. 0%; p < .05).

Table 1.

Bivariate associations between disclosure of sexual activity and receipt of sexual and reproductive health services among sexually active 14- to 24-year-olds with a past year clinic visit (n = 196)

| Health service | Did not disclose (n = 22), % | Disclosed (n = 174), % | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever STD test | 26.7 | 69.6 | .001a |

| Offered STD test at last visit | 5.0 | 48.4 | <.001 a |

| Discussed with a provider: | |||

| Pregnancy prevention | 35.0 | 72.7 | <.001 |

| STD prevention | 44.4 | 63.0 | .126 |

| Birth controlb | 58.3 | 81.1 | .064 |

| Condomsb | 53.8 | 83.7 | .009 |

| Asked by provider aboutb: | |||

| Sexual orientation | 0.0 | 28.8 | .066a |

| Penile-vaginal sex | 23.1 | 63.6 | .007a |

| Oral sex | 18.2 | 33.3 | .500a |

| Anal sex | 8.3 | 18.6 | .691a |

| Number of sex partners | 16.7 | 58.8 | .006a |

| Painful sex | 0.0 | 33.0 | .031a |

STD = sexually transmitted disease.

Bold indicates statistical significance at p < .05.

Fisher’s exact test was used instead of Pearson’s chi-square coefficient because some cells included fewer than five respondents.

Among those who said yes to “Did you and your healthcare provider(s) discuss sex or sexual health?”

Conclusions

It is promising that most sexually active AYA patients disclose their sexual activity to a provider during a sexual history. We found disclosure was associated with receipt of some recommended SRH services for this group such as STD testing, underscoring adolescent disclosure as a key element in receipt of quality SRH services. However, our findings suggest fewer younger sexually active patients disclose sexual activity, which may reflect heightened concerns about confidentiality (perhaps related to lack of time alone with a provider or mandatory reporting issues), or developmental differences across adolescence. Findings highlight the importance of the patient—provider relationship. Sexually active adolescents who were comfortable and trusted their provider were more likely to disclose, whereas those who felt judged were less likely.

Because of the small sample size and missing data, our analyses were limited to bivariate comparisons, and we were unable to examine more nuanced demographic differences (e.g., distinguishing gender minority youth or racial/ethnic minorities). We also may have had insufficient power to detect differences. Missing data because of survey skip patterns further limited sample sizes across our analyses. Given unadjusted findings and cross-sectional data, we cannot establish causality between patient—provider dynamics, disclosure, and receipt of SRH services. Finally, social desirability bias may influence respondents’ self-reports of sexual activity and disclosure.

Despite these limitations, our findings draw attention to a previously understudied topic and highlight areas for more rigorous research to inform clinical practice including studies with larger samples and those that consider how confidentiality concerns and developmental issues may impact patient/provider communications. Efforts to improve patient–provider relationships may increase sexually active adolescents’ disclosure. Strategies to do so may include provider preservice and continuing medical education, quality improvement initiatives, and systems-level innovations supportive of an adolescent-friendly practice where confidentiality and time alone are ensured [9,10]. Sexual health education can directly prepare adolescents for clinical interactions and stress the value of disclosing sexual activity. Finally, in accordance with existing literature [4–7], most AYA in our sample did not have a sexual history taken, highlighting a critical need to increase this practice. Our finding that sexually active AYA are overwhelmingly truthful when asked about their sexual behavior can reassure providers about the utility of doing so.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Most young sexually active patients disclose their sexual history, which may reassure clinicians who avoid these discussions. Some younger patients may not disclose because of confidentiality concerns. Findings underscore disclosure as a key element in receipt of quality adolescent services and the importance of the patient—provider relationship in promoting it.

Funding Sources

Funding for the National Survey of Sexual Health & Behavior was provided by Church & Dwight, Co., Inc., United States (Debby Herbenick, Principal Investigator) (Grant #00626284).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine. Sexual and reproductive health care: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/Surv2011.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:1705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bull SS, Rietmeijer C, Fortenberry D, et al. Practice patterns for the elicitation of sexual history, education, and counseling among providers of STD services: Results from the Gonorrhea Community action Project (GCAP). Sex Transm Dis 1999;26:584–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, et al. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:1924–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kurth AE, Holmes KK, Hawkins R, Golden MR. A national survey of clinic sexual histories for sexually transmitted infection and HIV screening. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:370–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Loeb DF, Lee RS, Binswanger IA, et al. Patient, resident physician, and visit factors associated with documentation of sexual history in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:887–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Copen CE, Dittus PJ, Leichliter JS. Confidentiality concerns and sexual and reproductive health care among adolescents and young adults aged 15–25. NCHS data brief, no 266 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Riley M, Ahmed S, Lane JC, et al. Using maintenance of certification as a tool to improve the delivery of confidential care for adolescent patients. J Ped Adol Gynecol 2017;30:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2016. Jul;31:755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]