Abstract

Flexibility in work schedules is key to helping parents with young children balance work and caregiving responsibilities. Prior research shows that work schedule inflexibility is associated with greater parenting stress and work-family conflict. Through these negative implications for parental wellbeing, work schedule inflexibility may also adversely influence children’s socioemotional development. This study uses data from an urban, birth-cohort sample of children born to predominantly unmarried parents, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study, to test the hypothesis that mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility is associated with children’s behavior problems at age 5. Results from lagged dependent variable models suggest that mothers’ high work schedule inflexibility was associated with more externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in their children, relative to experiencing low inflexibility. These associations were partially mediated by mothers’ parenting stress and depressive symptoms, and for externalizing behaviors only, these associations were concentrated among single-mother and low-income families.

Following dramatic increases in mothers’ labor force participation in the latter half of the twentieth century, managing work and child caregiving responsibilities has become a common and key challenge of modern parenting. Since 1965, labor force participation rates among women with children increased by 60% (from 45 to 78%; Bianchi, 2011), and correspondingly, the percentage of children in families with all parents working full-time and full-year rose from 14% in 1967 to 33% in 2009, with only 34% having a parent at home full-time in 2009 (Fox, Han, Ruhm & Waldfogel, 2013). Children in single-parent families are even more likely to have an employed parent: nearly half (45%) live with a parent that works full-time. With maternal employment now more likely to be the norm than the exception, understanding the work conditions that either promote or undermine child and family wellbeing is important for better supporting working parents with young children.

A key aspect of work conditions for child and family wellbeing is work schedule flexibility, defined as workers’ ability to decide when to work, such as the ability to vary the start and end times of the workday (Hill, Grzywacz, et al., 2008). Prior research suggests that work schedule flexibility is associated with lower work-family conflict and more positive mental health outcomes for parents (Jang, 2009; Michel, Kotrba, Mitchelson, Clark, & Baltes, 2011), whereas work schedule inflexibility is associated with more parenting stress (Nomaguchi & Johnson, 2016). Through its negative implications for parental wellbeing, work schedule inflexibility may also adversely influence children’s socioemotional development. Several studies suggest that parents’ work schedules (i.e., standard versus nonstandard), job quality, and work-family conflict are associated with children’s socioemotional outcomes (e.g., Johnson, Kalil, & Dunifon, 2012; Strazdins, O’Brien, Lucas, & Rodgers, 2013). Yet, little is known as to whether (in)flexibility in work schedules may also matter for children’s socioemotional development. Work schedule inflexibility may be particularly challenging for single-parent and low-income families, who have more limited social and economic resources with which to manage caregiving responsibilities.

This study contributes to the existing literature by empirically testing the hypothesis that mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility is positively associated with child behavior problems using data from an urban, birth cohort study of children born to predominantly unmarried parents, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). Mothers of young children are the focus of this study because managing work and caregiving demands is particularly challenging during early childhood before children are in school and when work-family conflict tends to be higher (Allen & Finkelstein, 2014; Hill, Jacob, et al., 2008), and thus, work schedule inflexibility may be particularly important during this developmental stage. Lagged dependent variable models are used to predict child behavior problems from mothers’ work schedule inflexibility when children were 5 years old, adjusting for a prior measure of child behavior. This study also examines the extent to which the associations between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior operate through mothers’ mental health, and whether these associations are moderated by family structure and income.

Background

Mothers’ work schedule flexibility might influence child and family wellbeing through two primary pathways. First, work schedule inflexibility may increase mothers’ experiences of work-family conflict, especially time-based conflict, which occurs when the time pressures of their job interfere with their ability to fulfill the demands of their family responsibilities (Greenhaus & Beutel, 1985; Voydanoff, 2002). For example, mothers may experience role conflict when they are unable to leave work early to attend to a sick child. By increasing work-family conflict, work schedule inflexibility may have negative consequences for mothers’ mental and emotional wellbeing, and in turn, their child’s socioemotional wellbeing. Second, stable and predictable environments are important for healthy early childhood development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), and work schedule inflexibility might interfere with mothers’ ability to maintain stable child care arrangements and consistent routines for their child, such as mealtimes and bedtimes (Lee, Hale, Berger, & Buxton, 2019). This is especially likely to be true for mothers in low-wage jobs with unpredictable and unstable work schedules (Carrillo, Harknett, Logan, Luhr, & Schneider, 2017).

Prior research suggests that workers’ perceived work schedule flexibility (e.g., how much flexibility they had in scheduling when they worked) is a stronger predictor of work-family fit than their use of flexible work arrangements (e.g., how often they chose when they started and ended work; Jones et al. 2008). This is likely because perceiving that work schedule flexibility is available if needed—whether through formal or informal flexible scheduling policies—provides some psychological benefit to workers even if they do not make use of flexible work arrangements (Allen, Johnson, Kiburz, & Shockley, 2013). Perceptions of work schedule flexibility are shaped not only by workplace policies but also by individuals’ and their families’ unique characteristics (Grzywacz, Carlson, & Shulkin, 2008; Kelly et al., 2008). Two mothers with the same flexible work arrangements available to them may differ in their perceptions of work schedule flexibility due to differences in personality, their child’s needs, or the availability of support with caregiving at home. This also suggests that child, maternal, and family characteristics could bias associations between perceived work schedule inflexibility and child and family wellbeing if unmeasured and unaccounted for. The current study focuses on mothers’ perceived work schedule flexibility and uses longitudinal data and lagged dependent variable models to minimize the potential for bias from omitted variables.

Prior studies and meta-analyses consistently find that greater work schedule flexibility, defined in various ways, is associated with lower work-family conflict (Allen et al., 2013; Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011; Michel et al., 2011; Shockley & Allen, 2007; Voydanoff, 2004), whereas greater work-family conflict is related to parents’ higher stress levels and worse mental health outcomes (Carlson et al., 2011; Grice et al., 2007; Strazdins et al., 2013). However, only a few studies have specifically examined the direct associations between work schedule (in)flexibility and parents’ stress and mental health. Using data from the FFCWS on families with 3-year-old children, Nomaguchi and Johnson (2016) found that mothers and fathers who reported higher levels of perceived work schedule inflexibility also reported more parenting stress compared to those who were not employed or who reported never experiencing inflexibility. In a subsample of working parents from a national sample of the U.S. workforce, Jang (2009) found support for a mediation model in which perceived work schedule flexibility was positively associated with parents’ general mental health through better work-life balance. Furthermore, studies that included a diverse sample of workers—including parents and childless adults—have found that flexible work schedules and perceived schedule flexibility are associated with lower stress and burnout and better mental health outcomes (Grzywacz et al., 2008; Henly & Lambert, 2014; Joyce, Pabayo, Critchley, & Bambra, 2010; Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Despite evidence that work schedule (in)flexibility is related to parents’ work-family conflict, stress, and mental health outcomes, less is known about whether the potential negative effects of work schedule inflexibility on parental wellbeing might spill over to their children. Research consistently finds that higher levels of parenting stress and depressive symptoms are related to more behavior problems in children (Abidin, 1992; Dawson et al., 2003); thus, it is plausible that work schedule inflexibility could lead to more child behavior problems at least in part through its effects on parents’ mental health. In support of this, recent research has found that parents’ unpredictable work schedules—those that provide workers with limited advance notice or control over of their weekly schedule, change hours and shifts week to week, and are adjusted or cancelled at the last minute—are associated with more externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in children and that these associations are mediated by household economic insecurity, time-based work-family conflict, and parental wellbeing, with the latter explaining the largest proportion of the associations (Schneider & Harknett, 2019). Moreover, other parental job characteristics, including work-family conflict, job quality, and nonstandard work schedules, have been found to predict child behavior, both externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, especially among young children (Dunifon, Kalil, Crosby, & Su, 2013; Johnson et al., 2012; Joshi & Bogen, 2007; Lombardi & Coley, 2013; Strazdins et al., 2013; Strazdins, Shipley, Clements, O’Brien, & Broom, 2010).

Only two prior studies have examined the associations between mothers’ work schedule flexibility and child outcomes, focusing on child health outcomes but not behavior problems. Lee and colleagues (2019) found that increases in mothers’ perceived work schedule flexibility from child ages 5 to 9 were associated with increases in child sleep duration at age 9, and that this association was mediated by increases in child’s adherence to a regular bedtime. Dush, Schmeer, and Taylor (2013) found that maternal work chaos—which included work schedule inflexibility—when children were 3 years old was associated with poorer maternal-rated child health at age 5 years. Thus, although theory and prior research suggest that mothers’ work schedule inflexibility may also be related to children’s behavioral functioning, this hypothesis has not been empirically tested.

Moreover, families’ social and economic resources may buffer the potential adverse effects of mothers’ work schedule inflexibility on child behavior. Mothers who do not have a partner at home with whom to share caregiving responsibilities may be more adversely impacted by a lack of flexibility in their job for dealing with family and child care issues. Similarly, low-income families have fewer economic resources with which to manage work and child care, including arranging high-quality and reliable child care (Pilarz & Hill, 2017). Thus, the associations between mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems may be more pronounced in single-mother and low-income families compared to married or cohabiting families or higher-income families, respectively.

Current Study

The purpose of this study is to further knowledge on how mothers’ work schedule inflexibility matters for children’s behavior by addressing three key research questions. First, is mothers’ work schedule inflexibility associated with children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior problems when children are 5 years olds? The study focuses on mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility—defined as mothers’ perceived lack of flexibility in their work schedule to deal with family issues and work schedule-related stress—and hypothesizes that higher levels of inflexibility will be associated with higher levels of behavior problems. Second, does mothers’ mental health explain the associations between mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems? I hypothesize that parenting stress and depressive symptoms will each partially mediate these associations. Third, do the associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems vary by family structure and income? I hypothesize that the associations between inflexibility and child behavior problems will be more pronounced among single-mother and low-income families. By using longitudinal data from the FFCWS, a key strength of this study is its ability to adjust for prior levels of child behavior problems and a large set of child and family characteristics to minimize the potential for selection bias.

Method

Data and Sample

This study used data from the FFCWS study, an urban, birth cohort sample of 4898 children born between 1998–2000 in 20 large U.S. cities with populations of at least 200,000 (Reichman, Teitler, Garkinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). Children born to unmarried parents were oversampled and comprise nearly three-fourths of the sample. The FFCWS study interviewed children’s biological parents shortly after the child’s birth and at follow-up core surveys via telephone when children were approximately 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15 years of age. Families who participated in the core surveys at the 3-year and 5-year waves were invited to participate in a home visit, which included an interview with the child’s primary caregiver (95–96% the child’s biological mother) and child assessments. This study used data from the first four waves of the mothers’ core surveys and the 3- and 5-year wave in-home interviews. Response rates ranged from 86% to 90% for mothers’ core surveys and 79% to 81% for the in-home interviews.

The analytic sample for this study included children whose mothers participated in the 3-year and 5-year core surveys and in-home interviews (2409 cases excluded because they did not), who lived with their mother at least half of the time at both waves (40 cases excluded), and who were not missing data on the dependent variables (20 cases excluded). Children whose mothers were not employed at the 5- year wave were also excluded from the main models (978 cases excluded). Missing data in the variables used in the analyses was low, ranging from 1% to 4%. To minimize potential bias from excluding cases with incomplete data, multiple imputation then deletion was used (von Hippel, 2007). Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data on all variables using imputation by chained equations in Stata 16; then, cases with missing data on the dependent variables were dropped. The final analytic sample consisted of 1451 cases. As the FFCWS study does not provide sampling weights for the in-home interview component, analyses were not weighted.

Measures

Perceived work schedule inflexibility.

This is defined as mothers’ perceived lack of flexibility in their work schedule to deal with family issues and their work schedule-related stress. Mothers rated the following three items based on how often they were true, ranging from always (1), often (2), sometimes (3), or never true (4): “My shift and work schedule cause extra stress for me and my child”; “Where I work it is difficult to deal with child care problems during work hours”; “In my work schedule, I have enough flexibility to handle family needs.” The first two items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicate higher levels of inflexibility (α=.60). This scale has been used in several prior studies of work inflexibility or chaos (Dush et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2019; Nomaguchi & Johnson, 2016). A categorical measure of work schedule inflexibility was created using the mean score on these items from the 5-year wave in order to account for non-linearity in the relationship between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior. Three categories were used: low inflexibility (a score equal to 1) indicates never experiencing inflexibility; moderate inflexibility (a score between 1–2) indicates sometimes experiencing inflexibility; and high inflexibility (a score greater than 2) indicates often or always experiencing inflexibility. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| Full Sample | Low Inflexibility | Mod. Inflexibility | High Inflexibility | Sig. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % | (SD) | Mean or % | (SD) | Mean or % | (SD) | Mean or % | (SD) | ||||||

| Mothers’ work schedule inflexibility (5-year) | |||||||||||||

| Low inflexibility | 38.02% | ||||||||||||

| Moderate inflexibility | 43.96% | ||||||||||||

| High inflexibility | 18.02% | ||||||||||||

| Child behavior problems (5-year) | |||||||||||||

| Externalizing behaviors | 0.53 | (0.31) | 0.48 | (0.30) | 0.54 | (0.30) | 0.60 | (0.33) | *** | ||||

| Internalizing behaviors | 0.24 | (0.20) | 0.21 | (0.18) | 0.24 | (0.19) | 0.29 | (0.23) | *** | ||||

| Mediators (5-year) | |||||||||||||

| Maternal parenting stress | 2.13 | (0.66) | 2.00 | (0.65) | 2.16 | (0.65) | 2.34 | (0.64) | *** | ||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 0.83 | (2.09) | 0.60 | (1.80) | 0.80 | (2.08) | 1.38 | (2.57) | *** | ||||

| Other employment characteristics (5-year) | |||||||||||||

| Work hours | |||||||||||||

| Employed part-time (<35 hours/week) | 28.53% | 30.23% | 28.01% | 26.19% | |||||||||

| Employed full-time (35–40 hours/week) | 52.08% | 53.80% | 52.83% | 46.65% | |||||||||

| Employed 41+ hours | 19.39% | 15.97% | 19.16% | 27.15% | *** | ||||||||

| Work schedule | |||||||||||||

| Standard hours only | 45.11% | 50.85% | 44.30% | 34.95% | *** | ||||||||

| Worked evenings | 26.13% | 20.22% | 28.17% | 33.65% | *** | ||||||||

| Worked nights | 12.40% | 9.69% | 12.77% | 17.21% | ** | ||||||||

| Worked weekends | 39.69% | 35.36% | 38.05% | 52.81% | *** | ||||||||

| Worked variable schedule | 24.92% | 21.62% | 26.40% | 28.30% | + | ||||||||

| Annual earnings | 21528.39 | (20409.35) | 22279.02 | (18914.82) | 21108.36 | (21229.77) | 20968.69 | (21401.33) | |||||

| Occupation | |||||||||||||

| Professional/executive | 22.71% | 24.95% | 22.95% | 17.36% | + | ||||||||

| Sales | 11.11% | 9.62% | 12.25% | 11.47% | |||||||||

| Administrative | 27.14% | 28.16% | 27.20% | 24.86% | |||||||||

| Machine operators/laborers | 6.13% | 4.17% | 6.59% | 9.18% | * | ||||||||

| Service | 32.91% | 33.11% | 31.01% | 37.13% | |||||||||

| Control variables | |||||||||||||

| Child gender is male | 50.86% | 50.21% | 52.68% | 47.80% | |||||||||

| Child low birthweight | 8.41% | 8.08% | 8.94% | 7.82% | |||||||||

| Child temperament score (1-year) | 2.75 | (1.04) | 2.65 | (1.03) | 2.80 | (1.05) | 2.87 | (1.03) | ** | ||||

| Child health is poor/fair/good health (3-year) | 9.65% | 7.79% | 10.03% | 12.62% | + | ||||||||

| Child age (months; 5-year) | 61.12 | (2.39) | 61.05 | (2.39) | 61.14 | (2.43) | 61.22 | (2.27) | |||||

| Child externalizing behavior problems (3-year) | 0.63 | (0.38) | 0.58 | (0.38) | 0.65 | (0.36) | 0.71 | (0.40) | *** | ||||

| Child internalizing behavior problems (3-year) | 0.37 | (0.23) | 0.33 | (0.21) | 0.39 | (0.23) | 0.40 | (0.24) | *** | ||||

| Mother’s age at child’s birth | 25.23 | (5.95) | 25.50 | (6.11) | 25.12 | (5.86) | 24.95 | (5.84) | |||||

| Mother’s race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 22.34% | 24.54% | 21.36% | 20.06% | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 52.10% | 50.01% | 52.77% | 54.86% | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 22.81% | 22.36% | 23.68% | 21.64% | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic other race/ethnicity | 2.76% | 3.09% | 2.20% | 3.44% | |||||||||

| Mother’s highest level of education | |||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 25.45% | 23.08% | 27.21% | 26.14% | |||||||||

| High school or equivalent | 30.90% | 32.08% | 29.63% | 31.47% | |||||||||

| Some college or technical school | 30.76% | 30.81% | 30.57% | 31.09% | |||||||||

| College degree or higher | 12.90% | 14.02% | 12.58% | 11.30% | |||||||||

| Mother’s relationship to child’s father | |||||||||||||

| Married | 25.22% | 25.80% | 26.54% | 20.80% | |||||||||

| Cohabiting | 36.39% | 40.24% | 32.61% | 37.48% | * | ||||||||

| Romantically involved | 26.26% | 24.65% | 26.97% | 27.92% | |||||||||

| Other relationship | 12.13% | 9.31% | 13.88% | 13.80% | * | ||||||||

| Mother is single (5-year) | 41.83% | 37.22% | 43.67% | 47.07% | * | ||||||||

| Mother born outside U.S. | 11.73% | 11.78% | 11.01% | 13.38% | |||||||||

| Mother’s health is poor/fair/good (3-year) | 37.56% | 32.87% | 38.97% | 44.02% | ** | ||||||||

| Mother’s high perceived social support (3-year) | 49.99% | 55.71% | 49.95% | 38.01% | *** | ||||||||

| Number of children in household (5-year) | 2.45 | (1.30) | 2.44 | (1.25) | 2.45 | (1.33) | 2.49 | (1.31) | |||||

| Number of adults in household (5-year) | 1.94 | (0.84) | 1.93 | (0.81) | 2.00 | (0.90) | 1.81 | (0.76) | * | ||||

| Type of child care (5-year) | |||||||||||||

| Parental care only | 9.16% | 9.27% | 8.58% | 10.34% | |||||||||

| Center-based care | 79.98% | 80.53% | 80.10% | 78.53% | |||||||||

| Home-based care | 10.86% | 10.20% | 11.33% | 11.13% | |||||||||

| Prior non-parental child care use | |||||||||||||

| No prior non-parental care | 20.58% | 19.67% | 22.12% | 18.72% | |||||||||

| Non-parental care at 1-year wave only | 9.83% | 10.11% | 8.78% | 11.82% | |||||||||

| Non-parental care at 3-year wave only | 26.33% | 25.43% | 26.38% | 28.13% | |||||||||

| Non-parental care at both prior waves | 43.26% | 44.79% | 42.72% | 41.34% | |||||||||

| Prior employment status | |||||||||||||

| Not previously employed | 16.33% | 16.69% | 17.23% | 13.37% | |||||||||

| Employed at 1-year wave only | 13.25% | 10.80% | 14.01% | 16.58% | + | ||||||||

| Employed at 3-year wave only | 17.48% | 15.61% | 17.96% | 20.27% | |||||||||

| Employed at both prior waves | 52.94% | 56.90% | 50.80% | 49.79% | + | ||||||||

| Family income as % of FPL | |||||||||||||

| 0–49% | 15.71% | 14.68% | 16.78% | 15.30% | |||||||||

| 50–99% | 15.09% | 13.96% | 15.05% | 17.59% | |||||||||

| 100–199% | 25.84% | 24.71% | 25.33% | 29.48% | |||||||||

| 200–299% | 17.09% | 16.13% | 18.19% | 16.44% | |||||||||

| 300%+ | 26.26% | 30.51% | 24.66% | 21.19% | ** | ||||||||

Notes: N=1451. Variables were measured at baseline unless noted otherwise in parentheses. Results are unweighted. Sig. column indicates that the mean of the variable differs across columns (i.e., low inflexibility, mod. Inflexibility, and high inflexibility) based on the results of an F-test.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10

Child behavior problems.

Mothers rated children’s behaviors using a subset of items from the Externalizing and Internalizing subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/2–3 and CBCL/4–18) at the 3-year and 5-year in-home interviews (Achenbach, 1991; 1992). The Aggressive subscale of the CBCL (15 items at 3-year wave; 20 items at 5-year wave) was used to measure children’s externalizing behaviors and includes items about aggressive, destructive, and disobedient behaviors (3-year wave α=.86; 5-year wave α=.85). Items from the Anxious/Depressed and Withdrawn subscales (25 items at 3-year wave; 22 items at 5-year wave) were used to measure internalizing behavior problems and include items about unhappy, shy, nervous, and fearful behaviors (3-year wave α=.81; 5-year wave α=.76). Mothers rated each behavior item as not true (0), somewhat/sometimes true (1), or very/often true (2) for the child. As recommended by the FFCWS study (Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, 2019), externalizing and internalizing items were summed and divided by the number of valid responses in each subscale (mean scores are shown in Table 1). Mean scores on each subscale from the 5-year wave were used as dependent variables, and mean scores from the 3-year wave were used as control variables.

Maternal parenting stress and depressive symptoms.

Mothers’ perceived stress brought on by the demands of caring for her children was measured at the 5-year wave using the mean score on a 4-item scale adapted from the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1995). Mothers rated each item (e.g., “Being a parent is harder than I thought it would be”) on a 4-point scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4). Items were reverse-coded and averaged so that higher scores indicate higher levels of stress (α=.66). Mothers’ depressive symptoms were measured using 8 items (e.g., “During the past 12 months, has there ever been a time when you felt sad, blue, or depressed for two or more weeks in a row?”) from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF; Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998). Each item was assigned a score of 1 if the mother endorsed the item, and a summed score of all items was used with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms (α =.96).

Other maternal employment characteristics.

The following variables were included to assess whether mothers’ work schedule inflexibility uniquely predicts child behavior net of other job characteristics: Mother’s total work hours was measured using indicators for the mother works part-time (1–34 hours per week); full-time (35–40 hours per week; reference category); or more than 40 hours per week. Mothers’ work schedule was measured using indicators for the mother regularly worked in the evenings, nights, weekends, or a variable schedule (i.e., different times each week) versus standard hours only. Mothers could report working multiple different types of nonstandard schedules, and therefore, these indicator variables are not mutually exclusive from each other (but are mutually exclusive from standard hours only). Annual earnings included mothers’ total earnings from all regular jobs worked in the past 12 months. Mothers’ occupation was measured based on their response to an item asking what they did at their current job. The FFCWS combined responses into nine categories, and I further collapsed these into five categories due to small number of mothers in certain occupations (e.g., machine operators; see Table 1).

Control variables.

Child, maternal, and family characteristics were included to adjust for factors that could plausibly be related to both mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems and could thus bias these associations. Control variables were measured at baseline unless otherwise noted. Child characteristics included indicators for male gender; low birth weight (<2500 grams); mother-reported health as poor, fair, or good (vs. very good or excellent) at the 3-year wave; and age at the 5-year wave. The child’s difficult temperament was measured at the 1-year wave as the mean score on 3 items from the Emotionality, Activity, and Sociability Temperament Survey for Children scale (α=.60; Mathiesen & Tambs, 1999).

Maternal demographic characteristics included race/ethnicity; family income in relation to the federal poverty line (FPL); an indicator for the mother was born outside of the U.S.; age; and highest level of education. The mother’s relationship to the child’s father at the child’s birth was measured as: married; cohabiting; romantically involved (but not living together); and other relationship, including friendly or no relationship at all. Family structure and household composition at the 5-year wave were measured as the total number of children and adults in the household and an indicator for the mother was single (i.e., not married or living with a partner).

Characteristics of the mother’s physical and psychosocial health that could influence her perceptions of work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems were measured at the 3-year wave, prior to the measure of work schedule inflexibility, in order to avoid controlling for potential mediators of the association between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior. Self-reported health status was included as indicator for the mother reported poor, fair, or good health versus very good or excellent health. Perceived social support was measured with an indicator variable for scoring above the median on the summed score of 6 items of mother’s perceived instrumental support (e.g., mother could count on someone to loan $200; α =.81).

Mother’s prior employment status at the 1-year and 3-year waves was included using a 4-category variable: (1) not previously employed (i.e., not employed at either the 1-year or 3-year waves); (2) employed at the 1-year wave only; (3) employed at the 3-year wave only; (4) employed at both prior waves. Children’s prior experiences with non-parental care were captured using a similar 4-category variable (see Table 1). Additionally, the primary type of non-parental care used for the child at the 5-year wave was included as: parental care only; center-based care; and home-based care, including non-relative and relative care.

Analytic Plan

To address the first research question—whether mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility is associated with child behavior problems— I used a lagged dependent variable (LDV), OLS regression model. This model estimates the associations between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems when children were 5 years old, adjusting for a prior measure of child behavior problems from the 3-year wave. The LDV model provides a more conservative estimate of the association between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior than standard OLS regression models by adjusting for observed and unobserved time-invariant factors that have the same effect on child behavior problems at the 3-year and 5-year-waves, such as genetic factors. This model is particularly appropriate when the outcome is persistent over time (i.e., the outcome at one time point has a causal effect on the outcome at a subsequent time point), as is likely the case for children’s behavior, and when prior levels of children’s behavior are likely to influence mothers’ current experiences of work schedule inflexibility, which is also likely given that mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility may be determined in part by children’s prior behavior problems (Allison, 1990; Angrist & Pischke, 2009). When this is the case, the LDV model is preferable to a simple change model or child fixed effects model as it provides more power to detect associations. However, the LDV model cannot rule out bias from unobserved characteristics that have differential impacts on child behavior at the 3-year and 5-year waves (NICHD & Duncan, 2003) or from simultaneity bias, meaning the possibility that child behavior problems could contemporaneously influence mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility. Thus, estimates from the LDV model should not be interpreted as causal estimates.

Model 1 regressed child behavior problems at age 5 on mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility at age 5 (with low inflexibility as the reference group), a prior measure of child behavior problems from the 3-year wave, and the control variables shown in Table 1. Post hoc tests were used to test for statistically significant differences in outcomes between high versus moderate inflexibility. In Model 2, I added measures of other maternal employment characteristics to Model 1. In all models, the dependent variables were standardized to have a mean equal to 0 and a standard deviation equal to 1; model estimates can be interpreted in standard deviation units.

To assess whether maternal parenting stress and depressive symptoms help explain the associations between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems, I estimated the following three models and computed estimates of the indirect effects of work schedule inflexibility on child behavior problems through parenting stress and depressive symptoms (using seemingly unrelated regression or sureg in Stata 16): (1) parenting stress regressed on work schedule inflexibility; (2) depressive symptoms regressed on work schedule inflexibility; and (3) child behavior problems regressed on work schedule inflexibility, parenting stress, and depressive symptoms. (Each of these models also included measures of other employment characteristics, control variables, and the lagged child outcome variable.) Mothers’ work schedule inflexibility, parenting stress, depressive symptoms, and child behavior problems were each measured at the 5-year wave. Ideally, it would be possible to establish a clear temporal order between the key independent variable, mediators, and dependent variables. However, the FFCWS has a two-year lag between data collection waves, and we would expect that mothers’ work schedule inflexibility would have concurrent effects on mothers’ mental health and children’s behavior rather than lagged effects. Due to these data limitations, a cross-sectional mediation model was used instead of a longitudinal model.

To test the hypothesis that the associations between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems differ by family structure and income, I added to Model 2 a set of interaction terms between work schedule inflexibility and an indicator for the child’s mother was single or an indicator for the family had an income below 200% of the federal poverty line at the 5-year wave. Each set of interaction terms was entered in a separate model.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Approximately 38% of employed mothers reported low perceived work schedule inflexibility, 44% reported moderate inflexibility, and 18% reported high inflexibility (see Table 1). With regard to other employment characteristics, a majority of mothers in the sample (52%) worked 35–40 hours per week and regularly worked nonstandard hours (55%). The most common occupation was in the service industry (33% of mothers). The sample of families from the FFCWS is also relatively socioeconomically disadvantaged: about 57% had incomes below 200% of the FPL, about one-quarter of mothers had less than a high school education, and 25% were married to the child’s father at the time of the child’s birth. About 42% of children were living with a single mother at age 5.

Several employment, maternal, child, and family characteristics differed across mothers’ perceived levels of work schedule inflexibility (see Table 1). In particular, mothers’ work hours and schedules varied significantly across perceived inflexibility, suggesting that mothers who worked more than 40 hours per week and who worked nonstandard schedules experienced higher levels of inflexibility. Results also suggest that mothers’ perceived inflexibility differed by family income, family composition, and maternal and child health, and social support. For example, mothers who reported higher levels of perceived inflexibility were more likely to report poorer health and less likely to report high perceived social support at the 3-year wave.

Associations Between Work Schedule Inflexibility and Child Behavior Problems

Results from Model 1 show that mothers’ high perceived work schedule inflexibility was associated with their child scoring 0.18 standard deviations higher on externalizing behaviors and 0.24 standard deviations higher on internalizing behaviors relative to low inflexibility (see Table 2). Mothers’ high perceived inflexibility was also associated with higher externalizing and internalizing behaviors relative to moderate inflexibility (statistically significant at p<.10 for externalizing behaviors). When adding other maternal employment characteristics in Model 2, the associations between high versus low perceived work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems reduced slightly and remained statistically significant. Model 2 revealed few associations between other maternal employment characteristics and child behavior problems: working nights versus standard hours only was associated with more internalizing behaviors.

Table 2.

Lagged dependent variable regression models predicting child behavior problems at age 5

| Externalizing Behaviors | Internalizing Behaviors | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Variable (reference group) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | ||||||

| Work schedule inflexibility (Low inflexibility) | ||||||||||||

| Moderate inflexibility | 0.07 (0.05) | a+ | 0.06 (0.05) | a+ | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | a | 0.02 (0.05) | a | −0.00 (0.05) | a | |

| High inflexibility | 0.18 (0.06) | ** | 0.17 (0.06) | * | 0.11 (0.06) | + | 0.24 (0.07) | ** | 0.21 (0.07) | ** | 0.15 (0.07) | * |

| Work hours (Full-time) | ||||||||||||

| Part-time | −0.09 (0.06) | + | −0.11 (0.06) | * | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.05 (0.06) | ||||||

| 41+ hours | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.06) | ||||||||

| Work schedule (Standard hours only) | ||||||||||||

| Worked evenings | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.06) | ||||||||

| Worked nights | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.21 (0.08) | ** | 0.21 (0.08) | ** | ||||||

| Worked weekends | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.05) | ||||||||

| Worked variable schedule | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | ||||||||

| Annual earnings | −0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.00) | ||||||||

| Occupation (Professional/executive) | ||||||||||||

| Sales | 0.07 (0.09) | 0.06 (0.08) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.06 (0.09) | ||||||||

| Administrative | 0.07 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.06) | ||||||||

| Machine operators/Laborers | 0.06 (0.11) | 0.07 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.14) | 0.23 (0.13) | + | |||||||

| Service | 0.09 (0.07) | 0.07 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.07) | ||||||||

| Maternal parenting stress | 0.09 (0.02) | *** | 0.10 (0.03) | *** | ||||||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 0.05 (0.02) | * | 0.06 (0.03) | * | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.92 (0.59) | 0.92 (0.59) | 1.06 (0.59) | + | 0.81 (0.67) | 0.81 (0.67) | 0.97 (0.65) | |||||

| R 2 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 | ||||||

Notes: N=1451. Coefficients are shown with robust standard errors in parentheses. All control variables listed in Table 1 were included in the models. Outcome variables, maternal parenting stress, and maternal depressive symptoms were standardized. Results are unweighted. a indicates coefficient differs from “High inflexibility” at p<.05; a+ indicates coefficient differs from “High inflexibility” at p<.10.

p<.001;

p<.01;

p<.05;

p<.10

Examining Maternal Parenting Stress and Depressive Symptoms as Mediators

Adding maternal parenting stress and depressive symptoms to Model 2 substantially reduced the coefficients of work schedule inflexibility (see Model 3 in Table 2). In the model predicting externalizing behaviors the coefficient of high inflexibility reduced to 0.11 standard deviations and was no longer statistically significant at a .05 level. In the model predicting internalizing behaviors, the coefficient of high inflexibility reduced to 0.15 standard deviations but remained statistically significant. Post hoc comparisons showed that high work schedule inflexibility was also associated with more internalizing behavior problems relative to moderate inflexibility. In Model 3, maternal parenting stress and depressive symptoms were each statistically significantly associated with more externalizing and internalizing behavior problems (e.g., scoring 1 standard deviation higher on depressive symptoms was associated 0.05 standard deviations more externalizing behaviors). Additionally, mothers’ high work schedule inflexibility was associated with higher parenting stress and depressive symptoms relative to low or moderate inflexibility (see Table A1 in online supplementary material).

For externalizing behaviors, the indirect effect of high (versus low) schedule inflexibility via parenting stress was 0.04 (SE=0.01, p=.001) and the indirect effect via depressive symptoms was 0.01 (SE=0.01, p=.08). Together, parenting stress and depressive symptoms accounted for approximately 33% of the association between high inflexibility and externalizing behaviors. For internalizing behaviors, the indirect effects of schedule inflexibility via parenting stress were 0.05 (SE=0.01, p<.001) in the association with high versus low inflexibility and 0.03 (SE=0.01, p=.004) in the association with high versus moderate inflexibility; the indirect effects of schedule inflexibility via depressive symptoms were 0.02 (SE=0.01, p=.07) for high versus low inflexibility and 0.01 (SE=0.01, p=.09) for high versus moderate inflexibility. The indirect effects accounted for approximately 29% of association between high versus low work schedule inflexibility and internalizing behaviors and for 21% of the association between high versus moderate inflexibility and internalizing behaviors. Whereas the indirect effects of parenting stress were consistently statistically significant at p<.05, the indirect effects of depressive symptoms were only marginally statistically significant at p<.10. These results suggest that parenting stress and depressive symptoms together partially mediated the associations between high inflexibility and child behavior problems.

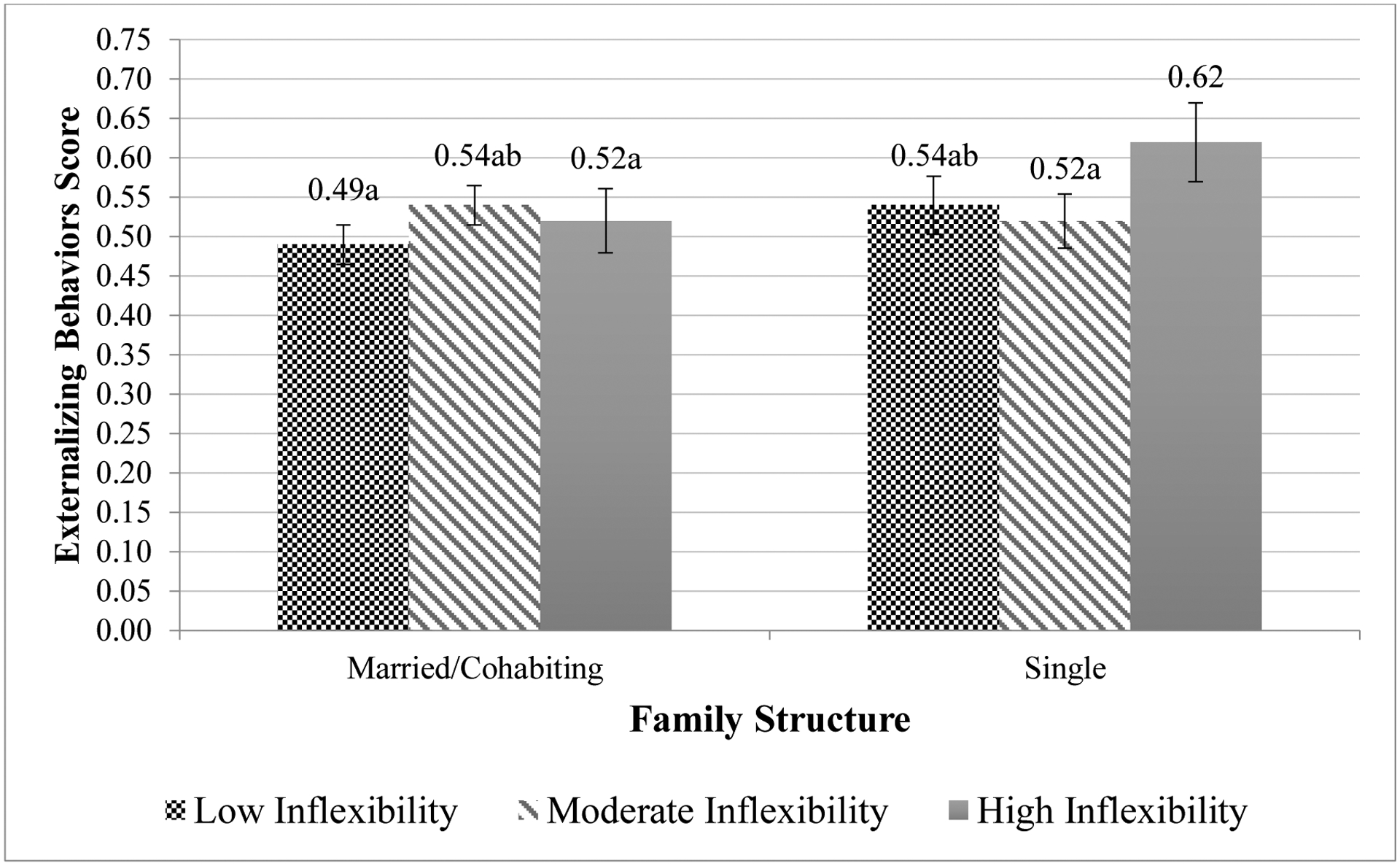

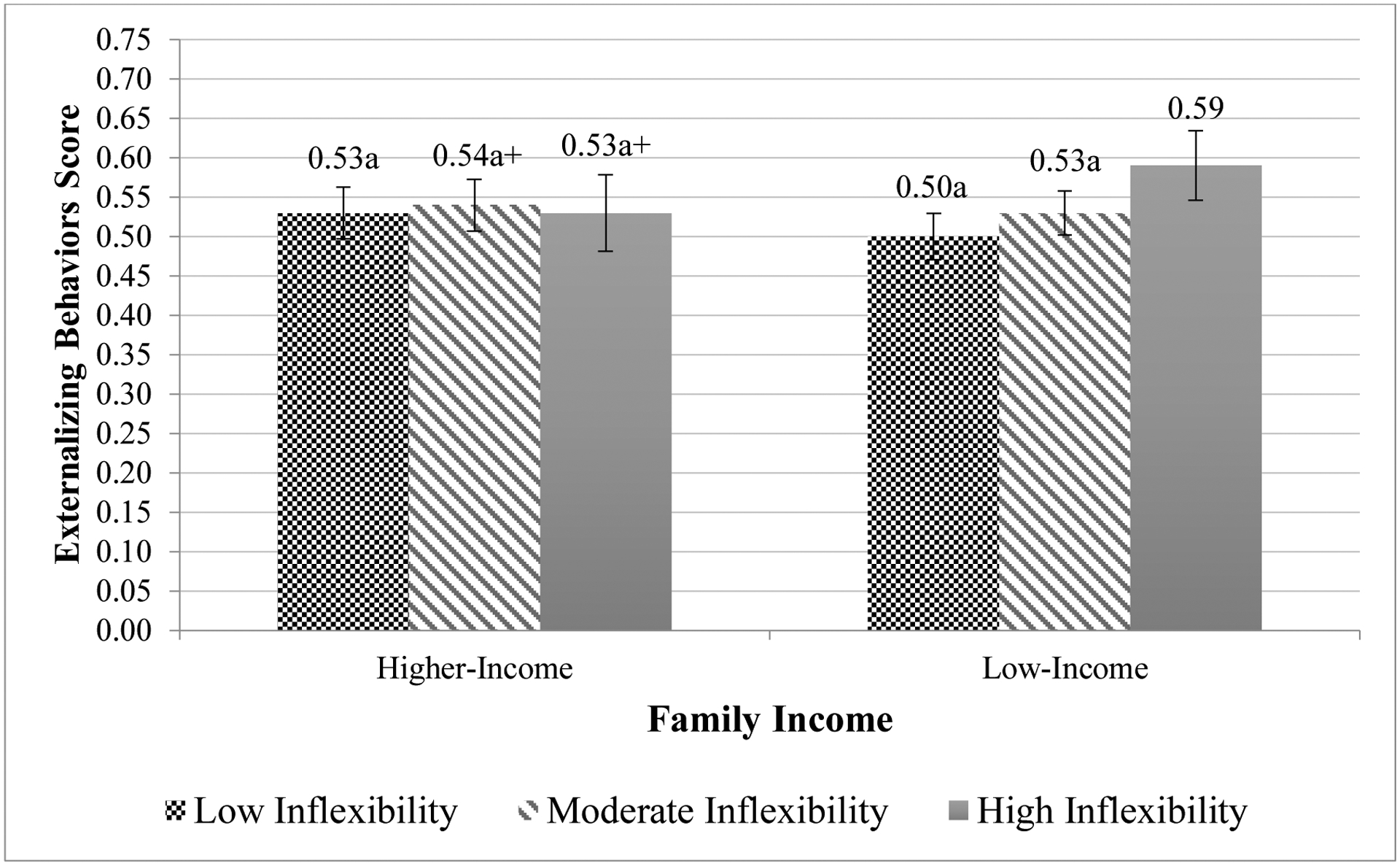

Examining Moderation by Family Structure and Family Income

Interaction model results suggest that the association between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and children’s externalizing behavior problems differs by family structure and family income (see Table A2 in the online supplementary materials); however, none of the interaction terms were statistically significant in the models predicting internalizing behavior problems. To ease interpretation of the findings, predicted means of externalizing behavior problems from the interaction models with family structure and family income are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Among single mother families, children who mothers reported high work schedule inflexibility scored higher on externalizing behaviors compared to children whose mothers reported low or moderate inflexibility (see Figure 1). These children also exhibited more externalizing behaviors relative to children in married/cohabiting families at each level of work schedule inflexibility. Among married/cohabiting families, there were no differences in the predicted means of work schedule inflexibility with one exception: moderate inflexibility was associated with more behavior problems relative to low inflexibility. With regard to family income, the results showed a similar pattern (see Figure 2). Among low-income families, children whose mothers reported high levels of work schedule inflexibility exhibited more behavior problems compared to those whose mothers reported low or moderate inflexibility and compared to children in higher-income families at each level of work schedule inflexibility (at a p<.10 or p<.05 significance level). There were no differences in children’s behavior problems by mothers’ work schedule inflexibility among higher-income families. These findings suggest that the associations between high work schedule inflexibility and externalizing behavior problems are concentrated among single-mother and low-income families.

Figure 1.

Predicted means of child externalizing behaviors from interaction model of work schedule inflexibility by family structure.

Notes: N=1451. a indicates mean is statistically significantly different from mean of “Single, High Inflexibility” at p<.05; b indicates mean is statistically significantly different from mean of “Married/cohabiting, Low Inflexibility” at p<.05.

Figure 2.

Predicted means of child externalizing behaviors from interaction model of work schedule inflexibility by family income.

Notes: N=1451. a indicates mean is statistically significantly different from mean of “Low-Income, High Inflexibility” at p<.05.

Sensitivity Analyses

I conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses: First, I examined the robustness of the findings to including mothers who were not currently employed at the 5-year study wave in the analytic sample (n=2429). These cases were coded as zero on the work schedule inflexibility items and were included as a separate category so that the work schedule inflexibility measure included four categories: not employed, low inflexibility, moderate inflexibility, and high inflexibility. In models that included not employed mothers, both the magnitude and statistical significance of the associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and children’s behavior problems were very similar as in the main models, suggesting that the findings are robust to the sample specification (see Table A3 in online supplementary material).

Second, I used an observer-rated measure of children’s behavior drawn from the 5-year in-home interview, which is available for approximately three-fourths of the analytic sample (n = 1067). In-home interviewers were asked to report whether the child displayed positive or negative behaviors during the interview and also to rate their persistence and cooperation with the child assessments, with higher scores indicating more positive behaviors overall. Results from models that used observer-reported positive behaviors as the outcome variable showed a similar trend but model estimates were smaller and not statistically significant (e.g., the coefficient of high inflexibility was −0.06 [SE=0.09; p=0.53]; see Table A4 in online supplementary material). This suggests that the findings may be sensitive to reporter type; however, the observer-rated measure of children’s positive behaviors differs substantively from the mother-reported measures of children’s behavior problems and is only available for a subset of the analytic sample. Given these differences in measures and samples, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions as to why findings differ when using the mother-reported versus observer-reported measures of child behavior.

Discussion

In an era of historically high levels of maternal employment, understanding the implications of mothers’ employment conditions for young children’s wellbeing is critical. Prior research has found that work schedule flexibility helps families balance work and family responsibilities and is associated with less work-family conflict and lower parenting stress (Jang, 2009; Nomaguchi & Johnson, 2016). The current study examined whether work schedule flexibility is also related to children’s socioemotional wellbeing by testing the hypothesis that higher levels of mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility would be associated with higher levels of child behavior problems. In this sample of predominantly low-income, unmarried families living in urban areas, nearly 1 in 5 working mothers experienced high levels of perceived work schedule inflexibility.

This study makes several contributions to our understanding of the relationships between mothers’ work schedule flexibility—defined as mothers’ perceived lack of flexibility in their work schedule to deal with family issues and work schedule-related stress—and young children’s wellbeing. First, results show statistically significant associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior problems at age 5 years, even after adjusting for other maternal employment characteristics (work hours, schedules, earnings, and occupation) and prior levels of child behavior problems. In particular, children whose mothers experienced high perceived inflexibility exhibited more externalizing and internalizing behaviors compared to those whose mothers experienced low perceived inflexibility and more internalizing behaviors relative to those whose mothers experienced moderate perceived inflexibility. Effects sizes were modest in size, ranging from about 0.18 to 0.24 standard deviations. Findings from this study build on prior research that has found associations between mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility and poorer child health outcomes (Dush et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2019) and suggest that when mothers experience high levels of work schedule inflexibility their children are also at risk for worse behavioral functioning.

Second, this study found that mothers’ parenting stress and depressive symptoms partially explained the associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and children’s behavior problems. Adjusting for maternal parenting stress and depressive symptoms statistically significantly reduced the estimated associations between mothers’ high perceived work schedule inflexibility and children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Together, mothers’ parenting stress and depressive symptoms accounted for about one-third of the associations between high versus low work schedule inflexibility and externalizing or internalizing behavior problems and for about one-fifth of the association between high versus moderate work schedule inflexibility and internalizing behavior problems. These findings are consistent with prior studies showing that work schedule inflexibility is associated with higher levels of work-family conflict, parenting stress, and mental health problems (e.g., Grzywacz et al., 2008; Jang, 2009; Joyce et al., 2010; Nomaguchi & Johnson, 2016). This study suggests that mothers’ work schedule inflexibility might lead to more child behavior problems at least in part by taking a toll on mothers’ mental health.

Third, findings from this study suggest that the associations between work schedule inflexibility and externalizing behavior problems (but not internalizing behavior problems) are concentrated among single-mother and low-income families. Children in single-mother families whose mothers experienced high levels of inflexibility exhibited the highest levels of externalizing behavior problems compared to all other groups of children (i.e., those in single-mother or partnered families whose mothers experienced low or moderate inflexibility or in partnered families who experienced high inflexibility), and the same was true for children in low-income families whose mothers experienced high levels of inflexibility. There was limited evidence that work schedule inflexibility was associated with more externalizing behavior problems in partnered (i.e., married or cohabiting) or higher-income families. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that families with fewer social and economic resources are less able to buffer adverse effects of work schedule inflexibility on children.

This study used longitudinal data from a diverse sample of predominantly low-income, non-married families to estimate associations between mothers’ perceived work schedule inflexibility and children’s behavior problems when children were 5-years-old. Because the FFCWS sample is more socioeconomically disadvantaged compared to the general U.S. population and limited to urban areas, findings may not be generalizable to other populations or geographic areas. This study was also limited by the FFCWS measures. The internal consistency scores for the measures of mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and parenting stress were adequate but not strong, and mothers’ reports of children’s behavior problems could be biased if mothers who are more depressed or stressed over-report their child’s behavior problems (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 2003). Non-maternal reports of children’s behavior in the FFCWS study are limited. Sensitivity tests using measures of observer-rated child behaviors (i.e., collected by the FFCWS in-home interviewer) found no statistically significant associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and child behavior although overall trends were similar. Further research on the associations between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and child behavior using stronger measures of non-maternal reports of child behavior problems is needed.

Although analytic models controlled for prior levels of children’s behavior problems and a large set of child and family background characteristics, it is not possible to rule out selection bias or reverse causality if children’s behavior problems influence mothers’ perceptions of work schedule inflexibility. For example, it is possible that a mother who needs more work schedule flexibility due to her child’s behavior problems perceives her work schedule to be inflexible because of her greater need for flexibility. If this is the case, then the observed associations between work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems could be driven in part by higher levels of child behavior problems contributing to mothers’ perceptions of schedule inflexibility. The lagged dependent variable models used in this study cannot parse out the directionality of the relationship between mothers’ work schedule inflexibility and child behavior problems, and thus, this remains an important question for future research.

Despite these limitations, this study advances our understanding of how mothers’ employment conditions matter for children’s wellbeing. The findings point to the importance of work schedule flexibility for helping mothers, particularly single and low-income mothers, to manage work and caregiving responsibilities and supporting mothers’ psychological wellbeing. The findings suggest that the effects of work schedule (in)flexibility may spill over from mothers to their children, and highlight the need for increasing access to flexible work schedules for working mothers with young children.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abidin RR (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21(4), 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR (1995). Parenting Stress Index (3rd ed.). Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile.Burlington VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1992). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile.Burlington VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, Johnson RC, Kiburz KM, & Shockley KM (2013). Work–family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing flexibility. Personnel Psychology, 66(2), 345–376. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, & Finkelstein LM (2014). Work–family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(3), 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD (1990). Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. Sociological Methodology, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD & Pischke J-S (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. (2019). User’s guide for the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Public Data, Year 5. Retrieved from https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/sites/fragilefamilies/files/year_5_guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S (2011). Change and time allocation in American Families. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 638, 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In Lerner RM & Damon W (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, (pp.793–828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DS, Grzywacz JG, Ferguson M, Hunter EM, Randall C, & Arcury TA (2011). Health and turnover of working mothers after childbirth via the work–family interface: An analysis across time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 1045–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo D, Harknett K, Logan A, Luhr S, & Schneider D (2017). Instability of work and care: How work schedules shape child-care arrangements for parents working in the service sector. Social Service Review, 91(3), 422–455. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Ashman SB, Panagiotides H, Hessl D, Self J, Yamada E, & Embry L (2003). Preschool outcomes of children of depressed mothers: Role of maternal behavior, contextual risk, and children’s brain activity. Child Development, 74(4), 1158–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, Kalil A, Crosby DA, & Su JH (2013). Mothers’ night work and children’s behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 49(10), 1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK, Schmeer KK, & Taylor M (2013). Chaos as a social determinant of child health: Reciprocal associations? Social Science & Medicine, 95, 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, & Horwood LJ (1993). The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 21(3), 245–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox L, Han W-J, Ruhm C, & Waldfogel J (2012). Time for Children: Trends in the Employment Patterns of Parents, 1967–2009. Demography, 50(1), 25–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, & Beutell NJ (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grice MM, Feda D, McGovern P, Alexander BH, McCaffrey D, & Ukestad L (2007). Giving birth and returning to work: The impact of work–family conflict on women’s health after childbirth. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(10), 791–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Carlson DS, & Shulkin S (2008). Schedule flexibility and stress: Linking formal flexible arrangements and perceived flexibility to employee health. Community, Work and Family, 11(2), 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Henly JR, & Lambert S (2014). Unpredictable work timing in retail jobs: Implications for employee work-life outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 67(3): 986–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Grzywacz JG, Allen S, Blanchard VL, Matz-Costa C, Shulkin S, & Pitt-Catsouphes M (2008). Defining and conceptualizing workplace flexibility. Community, Work and Family, 11(2), 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Jacob JI, Shannon LL, Brennan RT, Blanchard VL, & Martinengo G (2008). Exploring the relationship of workplace flexibility, gender, and life stage to family-to-work conflict, and stress and burnout. Community, Work and Family, 11(2), 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jang SJ (2009). The Relationships of Flexible Work Schedules, Workplace Support, Supervisory Support, Work-Life Balance, and the Well-Being of Working Parents. Journal of Social Service Research, 35(2), 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Kalil A, & Dunifon RE (2012). Employment patterns of less-skilled workers: Links to children’s behavior and academic progress. Demography, 49(2), 747–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Scoville DP, Hill EJ, Childs G, Leishman JM, & Nally KS (2008). Perceived versus used workplace flexibility in Singapore: Predicting work-family fit. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(5), 774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P, & Bogen K (2007). Nonstandard schedules and young children’s behavioral outcomes among working low‐income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(1), 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce K, Pabayo R, Critchley JA, & Bambra C (2010). Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD008009. Retrieved from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2/abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Kossek EE, Hammer LB, Durham M, Bray J, Chermack K, … & Kaskubar D. (2008). Getting there from here: Research on the effects of work–family initiatives on work–family conflict and business outcomes. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 305–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P, & Tranby E (2011). Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict schedule control in a white-collar organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290. 10.1177/0003122411400056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, & Wittchen H-U (1998). The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7(4), 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Hale L, Berger LM, & Buxton OM (2019). Maternal perceived work schedule flexibility predicts child sleep mediated by bedtime routines. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(1), 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi CM, & Coley RL (2013). Low‐income mothers’ employment experiences: Prospective links with young children’s development. Family Relations, 62(3), 514–528. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen KS, & Tambs K (1999). The EAS temperament questionnaire – Factor structure, age trends, reliability, and stability in a Norwegian sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(3), 431–439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JS, Kotrba LM, Mitchelson JK, Clark MA, & Baltes BB (2011). Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network & Duncan, G. J. (2003). Modeling the impacts of child care quality on children’s preschool cognitive development. Child Development, 74(5), 1454–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi K, & Johnson W (2016). Parenting stress among low-income and working-class fathers: The role of employment. Journal of Family Issues, 37(11), 1535–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarz AR, & Hill HD (2017). Child‐care instability and behavior problems: Does parenting stress mediate the relationship?. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(5), 1353–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile Families: sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4–5), 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D & Harknett K (2019). Parental exposure to routine work schedule uncertainty and child behavior (Working paper series). Washington, DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Retrieved from https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/parental-exposure-to-routinework-schedule-uncertainty-and-child-behavior/ [Google Scholar]

- Shockley KM, & Allen TD (2007). When flexibility helps: Another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(3), 479–493. [Google Scholar]

- Strazdins L, O’Brien LV, Lucas N, & Rodgers B (2013). Combining work and family: Rewards or risks for children’s mental health? Social Science & Medicine, 87, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazdins L, Shipley M, Clements M, Obrien LV, & Broom DH (2010). Job quality and inequality: Parents’ jobs and children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Social Science & Medicine, 70(12), 2052–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, & Ganster DC (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1), 6. [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel PT (2007). Regression with missing Ys: An improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology, 37(1), 83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P (2002). Linkages between the work-family interface and work, family, and individual outcomes: An integrative model. Journal of Family Issues, 23(1), 138–164. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P (2004). The effects of work demands and resources on work‐to‐family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 398–412. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.