OBJECTIVES:

Determine the role of surfactant protein D (SPD) in sepsis.

DESIGN:

Murine in vivo study.

SETTING:

Research laboratory at an academic medical center.

PATIENTS:

SPD knockout (SPD−/−) and wild-type (SPD+/+) mice.

INTERVENTIONS:

SPD−/− and SPD+/+ mice were subjected to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). After CLP, Escherichia coli bacteremia was assessed in both groups. Cecal contents from both groups were cultured to assess for colonization by E. coli. To control for parental effects on the microbiome, SPD−/− and SPD+/+ mice were bred from heterozygous parents, and levels of E. coli in their ceca were measured. Gut segments were harvested from mice, and SPD protein expression was measured by Western blot. SPD−/− mice were gavaged with green fluorescent protein, expressing E. coli and recombinant SPD (rSPD).

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

SPD−/− mice had decreased mortality and decreased E. coli bacteremia compared with SPD+/+ mice following CLP. At baseline, SPD−/− mice had decreased E. coli in their cecal flora. When SPD−/− and SPD+/+ mice were bred from heterozygous parents and then separated after weaning, less E. coli was cultured from the ceca of SPD−/− mice. E. coli gut colonization was increased by gavage of rSPD in SPD−/− mice. The source of enteric SPD in SPD+/+ mice was the gallbladder.

CONCLUSIONS:

Enteral SPD exacerbates mortality after CLP by facilitating colonization of the mouse gut with E. coli.

Keywords: cecal ligation and puncture, critical illness, Escherichia coli, sepsis, surfactant protein D

Sepsis is a syndrome caused by a dysregulated inflammatory response to infection, resulting in organ failure, and causes significant morbidity and mortality (1). Current sepsis therapies are limited to early control of infection and supportive care (2, 3). Many investigational agents have failed to improve sepsis outcomes (4). Surfactant protein D (SPD), a member of the collectin family of pattern recognition receptors, plays a key role in innate immunity (5). Accordingly, SPD is protective in preclinical models of infectious disease (6, 7). Although SPD is largely synthesized in the lung, SPD has also been detected in the mouse gastrointestinal tract after synthesis and secretion from the gallbladder, suggesting extrapulmonary functions of SPD (8). However, the role of SPD in nonpulmonary infections remains unknown.

Given the role of SPD in innate immunity, we hypothesized that SPD deficiency would increase mortality following polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Unexpectedly, we found that SPD−/− mice had improved survival after CLP. This difference in mortality was driven by SPD-dependent differences in colonization of the mouse gut by Escherichia coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Housing

SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice were provided by Drs. Whitsett and Kingma (Cincinnati, OH) (9). Male mice were used for mortality experiments (Figs. 1 and 2), except for a confirmatory mortality experiment performed in females (Supplemental Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995). Otherwise, combinations of adult females and males were used. See Supplemental Table 1 (http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995) for experimental animal ages. Animals were housed separated by genotype (except as noted for cohousing experiments below) in a barrier facility. Mice were maintained on a mixed background (Black Swiss, 129, C57BL/6). Experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines (10).

Figure 1.

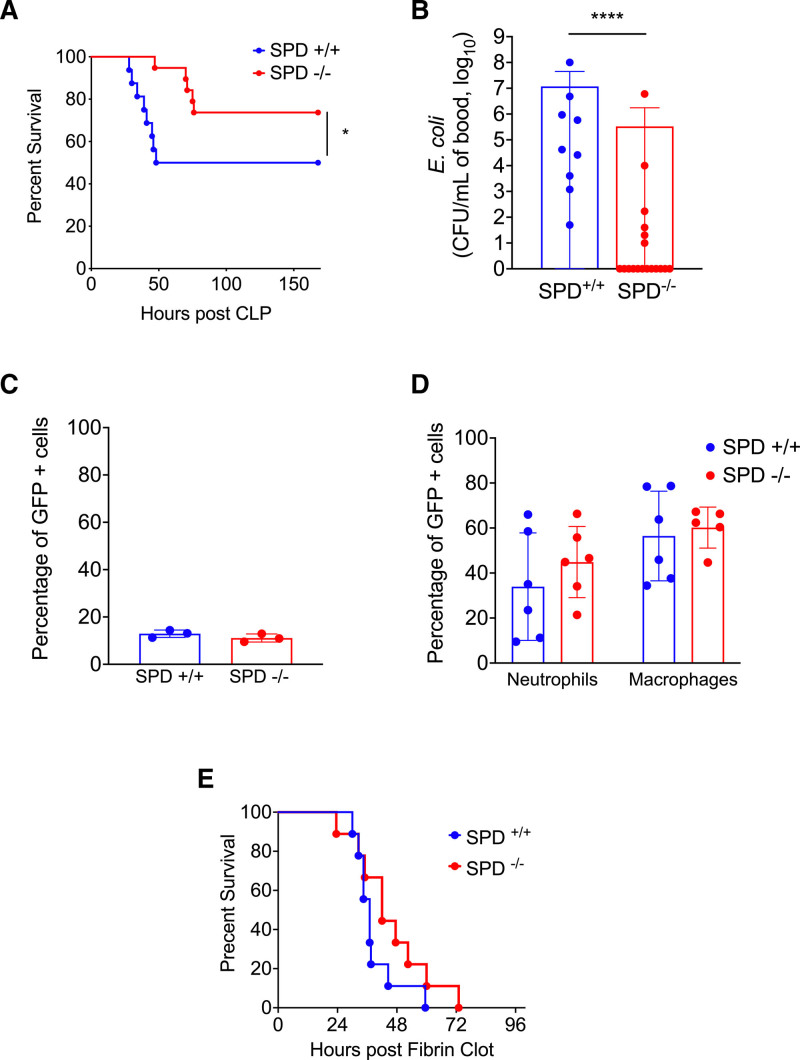

Surfactant protein D (SPD) deficiency reduces Escherichia coli bacteremia and mortality after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) by reducing cecal colonization by E. coli. A, CLP (100 % ligation, 19-G puncture, two holes) was performed on SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice (n = 16/group) (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon, *p < 0.05). B, Blood E. coli load following CLP. E. coli colony forming units (CFU) in blood 24 hr after CLP (100% ligation, 19-G puncture, one hole) in SPD+/+ (n = 9) and SPD−/− (n = 18) mice (Mann-Whitney, ****p < 0.0001). C, Ex vivo phagocytosis. Neutrophils were isolated from SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice (n = 3/group) and incubated with green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing E. coli. The percentage of GFP+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney). D, In vivo phagocytosis. SPD+/+ mice (n = 5–6) and SPD−/− mice (n = 6) were injected intraperitoneally with GFP expressing E. coli. Neutrophils and macrophages were identified by cell surface markers, and the percentage of GFP+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney). E, Post E. Coli fibrin clot survival of SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice (n = 9/group) (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon, p > 0.05), where both SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice were exposed to exogenous E. coli. E. coli for fibrin clot was isolated from SPD+/+ cecum.

Figure 2.

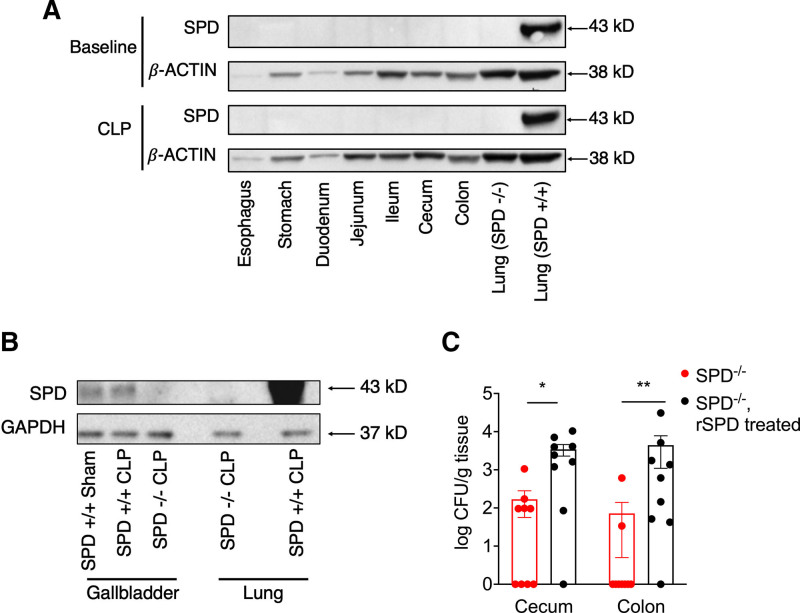

Surfactant protein D (SPD) is synthesized by the gallbladder and promotes colonization of both the cecum and colon with Escherichia coli. A, SPD+/+ gut organs were harvested at baseline or post-cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) with Western blots performed for SPD or β-actin (loading control). Blots represent pooled samples, n = 2/group. Representative gel shown from three experiments. Lungs from SPD−/− and SPD+/+ mice were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. B, Gallbladder was isolated from SPD+/+ mice after CLP or sham surgery and from SPD−/− mice after CLP with Western blots performed for SPD or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (GAPDH; loading control). Blots represent pooled samples, n = 5–7/group. Lungs from SPD−/− mice and SPD+/+ were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. C, SPD−/− mice (n = 9) were gavaged with recombinant surfactant protein D (rSPD), followed by gavage with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled E. coli, and compared with SPD−/− mice gavaged only with GFP-labeled E. coli (n = 9). After 24 hr, cecum and colon were harvested. GFP-labeled E. coli were then detected by culture (Mann-Whitney *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). CFU = colony forming units.

CLP and Fibrin Clot Sepsis Models

CLP was performed, as described (11–13). Briefly, after induction of anesthesia and analgesia with ketamine (85 mg/kg) and xylazine (34 mg/kg), mice were anesthetized, and a midline laparotomy was performed. The cecum was externalized, ligated, and punctured, after which a small amount of cecal contents were extruded from the puncture holes. The cecum was then replaced in the abdomen, and the abdominal incision was closed in layers. The mice were resuscitated with 1-mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed in a warmed cage for postoperative recovery. As our study was focused on bacterial growth, the mice did not receive antibiotics to avoid reducing the sensitivity of blood and stool cultures. Fibrin clots were prepared as described (14, 15) prior to inoculation with Escherichia coli isolated from SPD+/+ mice stool.

Bacterial Culture From Blood and Peritoneal Fluid

Mice underwent CLP (50% ligation, two 19G-holes) and were sacrificed 24 hours later. Peritoneal lavage was performed with 10-mL PBS, and blood was withdrawn from the right ventricle. Assessment for bacterial load in the peritoneum was measured by culturing samples on Luria-Bertani [LB] agar.

Cecal Culture of E. coli

Mice were anesthetized, and ceca were removed under sterile conditions, washed in sterile PBS, weighed, and frozen (−80°C). Frozen samples were transferred to 5 mL of sterile PBS at room temperature, then homogenized (26,000 rotations per minute [RPM], 10 s), plated onto MacConkey agar, and incubated overnight (37°C). Lactose fermenting colonies that were flat and nonmucoid were recultured onto sheep’s blood agar, and indole testing was performed. E. coli colonies were identified as indole positive, flat, nonmucoid, pink colonies on MacConkey agar (16).

Phagocytosis Assays

For in vivo assays, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled E. coli (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC] 25922GFP) were injected (intraperitoneally [IP]) into SPD+/+mice. At 1 hour, the peritoneal lavage was performed, and cells were harvested (see Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995). Using flow cytometry, neutrophils (CD45+, CD11bhigh, Ly6Ghigh, and Ly6Chigh) and macrophages (CD45+ and F4/80high) were identified, and phagocytosis was quantified by measuring the positive GFP signal in those populations. For ex vivo assays, mice were pretreated with 1-mL 2% biogel P-100 (Biorad, Hercules, CA) IP, followed 24 hours later by peritoneal lavage. Neutrophils were isolated and incubated with GFP-labeled E. coli and then identified by flow cytometry (Ly6Ghigh and GR1+), and the amount of phagocytosis was determined as above.

Cohousing Experiments

Littermate SPD−/− mice and SPD+/+ mice were bred from SPD heterozygous (SPD+/−) parents. The mice were then either cohoused until sacrificed and cultured or separated by genotype after weaning (3–4 wk), and then killed prior to culture of cecal contents.

Immunoblotting

After sacrifice, gut segments were flushed with PBS. Tissue was harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored (−80°C). Frozen tissues were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay protein lysis buffer, centrifuged at 4°C, 8,000 RPM for 10 minutes, and supernatant was collected. After sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose, membranes were incubated with anti-SPD antibody 2 µg/mL or 10 µg/mL (CatAF6839 R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (Abcam Cat97051, Cambridge, United Kingdom) or anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich CatA5441, St. Louis, MO) as control (see Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995).

GFP-Labeled E. coli Colonization

SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice were gavaged with 10 μL/g of ampicillin-resistant GFP-labeled E. coli (ATCC 25922GFP, 3.74 × 108 colony forming units/mL) with or without recombinant human surfactant protein D (rSPD) (Cat 1920-SP-050, R&D systems). Twenty-four hours later, mice were sacrificed, and gut segments were harvested under sterile conditions and frozen (−80°C). Cecum and colon were isolated and homogenized in 5 mL of sterile PBS and then cultured on LB agar plates with ampicillin 100 µg/mL selected for growth of ampicillin-resistant GFP-labeled E. coli. Fluorescent colonies were identified under UV light and manually counted using a ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Biorad).

Mouse Microbiome Analysis

Cecal contents were collected from three SPD+/+ mice and three SPD−/− mice and immediately placed in an anaerobic transport system. Contents were incubated and cultured, and colonies were identified based on morphology, Gram stain, or long-chain fatty acid analysis. For isolates unable to be typed by biochemical methods, 16S ribosomal RNA analysis was performed (see Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995).

Statistics

Data are reported as mean ± sd. Data were assessed for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Groups were compared using Student t test for parametric data or Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data. Mortality curves were compared using the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Differences were considered significant if p value was less than or equal to 0.05.

Study Approval

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee [IACUC] Protocol 2016N000308) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA, and the IACUC at the Ohio State University, in Columbus, OH (the Ohio State University IACUC approval 2020A00000037) in agreement with the regulations of the National Institutes of Health Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, Bethesda, MD.

RESULTS

SPD deficiency reduces E. coli bacteremia and mortality after CLP by reducing cecal colonization by E. coli. We unexpectedly found SPD−/− mice had increased survival after CLP (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995). Following CLP, SPD+/+ mice had higher E. coli bacteremia than SPD−/− mice (Fig. 1B). Immune effector cells from SPD−/− mice did not demonstrate enhanced phagocytosis of E. coli compared with SPD+/+ mice (Fig. 1, C and D). To determine whether SPD−/− mice were inherently resistant to infection with E. coli, we inoculated SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice using fibrin clot admixed with exogenous E. coli implanted into the peritoneal space and found no difference in mortality between SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice (Fig. 1E).

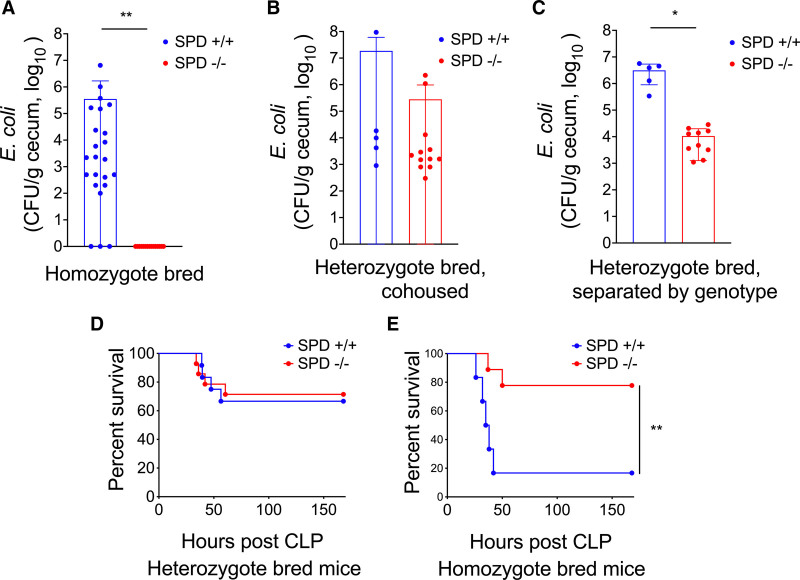

SPD−/− mice have diminished cecal E. coli colonization. We found significantly more E. coli in cecal contents from SPD+/+ relative to SPD−/− mice (Fig. 3A), suggesting that decreased mortality and E. coli bacteremia in SPD−/− mice following CLP are driven by decreased cecal colonization with E. coli. E. coli was one of several bacterial species that differed between genotypes (Supplemental Fig. 2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A995). Caging conditions and maternal microbiota impact the gut microbiome (17, 18). To control for these variables, we bred SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice from SPD heterozygous parents and cohoused wild-type and knockout offspring. SPD−/− offspring from heterozygous parents housed with SPD+/+ littermates became colonized with similar levels of E. coli compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 3B). However, when heterozygous-bred SPD−/− offspring were separated from SPD+/+ littermates after weaning, SPD−/− mice had decreased cecal colonization with E. coli compared with SPD+/+ mice (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that effects of SPD persist when controlling for maternal microbiome and cage conditions. We next hypothesized that cohousing would eliminate mortality differences observed between SPD−/− and SPD+/+ mice. When SPD+/+ and SPD−/− offspring from heterozygous parents were cohoused, there were no differences in mortality following CLP (Fig. 3D). SPD−/− offspring from homozygous parents raised in separate cages from SPD+/+ mice again demonstrated improved survival after CLP (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Surfactant protein D (SPD)−/− mice have diminished cecal Escherichia coli colonization. A, E. coli cultured from cecal culture of homozygote bred SPD+/+ mice (n = 24) and SPD−/− mice (n = 15) (**p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney). B, E. coli cultured from cecal culture of heterozygote bred, cohoused SPD+/+ (n = 5) mice and SPD−/− mice (n = 12) (p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney). C, E. coli cultured from cecal culture of heterozygote bred, SPD+/+ mice (n = 5) and SPD−/− mice (n = 10) after 7 wk of separation, by genotype (*p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney). D, Post-cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) survival in heterozygote bred, cohoused SPD+/+ mice (n = 12) and SPD−/− mice (n = 14), where SPD−/− mice had exposure to E. coli from the feces of SPD+/+ mice (p = ns, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon). E, Post-CLP survival of homozygote bred SPD+/+ (n = 6) and SPD−/− (n = 9) mice (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon, **p < 0.01) for concurrent recapitulation of the findings in Figure 1A. CFU = colony forming units.

SPD is synthesized by the gallbladder and promotes colonization of both the cecum and colon with E. coli. Given that SPD has been detected in the gut (8, 19) and can bind E. coli (5), we hypothesized that gut SPD expression was driving differences in E. coli colonization between SPD+/+ and SPD−/− mice. The gallbladder was the only gut tissue in which we detected expression of SPD (Fig. 2A). SPD expression in the gallbladder was not significantly changed after CLP (Fig. 2B). SPD−/− mice pretreated with enteral rSPD prior to gavage with GFP-labeled E. coli had significantly more E. coli retained in the cecum and colon compared with SPD−/− mice that did not receive rSPD (Fig. 2C). Together, these data suggest that SPD plays a critical role in colonizing the mouse gut with E. coli.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that mice lacking SPD unexpectedly have improved survival after CLP mediated by decreased gut colonization by E. coli. Deficiency of SPD has been implicated in the development of obesity (20), emphysema (21), and pulmonary infections (7); however, this is the first study to our knowledge to investigate the role of SPD in polymicrobial sepsis from an abdominal source. Gut microbiota are an important factor impacting sepsis outcomes (22). E. coli bacteremia is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for 27% of bacteremia and an estimated case fatality rate of 12% (23). Hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients with E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae blood stream infections were more likely to have those bacteria identified in their gut microbiota, suggesting an intestinal source (24). Several studies have noted that species like E. coli, which predominate in the absence of anaerobes, are those most likely to translocate and cause bacteremia (24–28).

Our work builds substantially upon Sarashina-Kida et al (8), who described that gallbladder-derived SPD influences gut microbiota in a noninfectious colitis model. However, they did not describe how SPD deficiency affects gut colonization with E. coli that we report here. It is possible that their use of untargeted 16S sequencing without standard culture techniques did not permit the detection of E. coli. Use of bacterial culture allowed us to detect scarce, but rapidly proliferating organisms that are potentially pathogenic.

CLP is the most frequently used animal model of sepsis and is considered to be among the most relevant because infection results from the release of live endogenous bacteria (12, 29). We and others have demonstrated the central role of the gut microbiota in driving the pathogenesis of CLP (18). However, assessment of the gut microbiome at the time of CLP is not typically performed (12). Gut microbial colonization of animals varies widely based on the vendor supplying the animals, the housing facility, and diet, which makes comparing findings between studies difficult (18). Thus, there is increasing recognition that the microbiome is a critical and potentially confounding variable, even in noninfectious mouse models (30). Future CLP studies should consider the mouse microbiome as a critical variable given its outsized role in driving mortality. Studies like ours, which used littermate controls housed under identical conditions, may decrease potential confounding.

Alterations in gut microbiota have been associated with increased risk of sepsis (31, 32). In addition to driving colonization of the gut with potentially pathogenic organisms, SPD may also increase susceptibility to sepsis via modulation of the microbiome. Our study raises the intriguing possibility that modulation of the interaction between SPD and the gut microbiome could represent a novel therapeutic approach in sepsis.

Our study has several limitations. The nature of the interaction between SPD and E. coli is not yet clear. SPD causes agglutination of E. coli via interactions with bacterial saccharides; however, it is unknown if this is also the mechanism by which E. coli is retained in the gut (33). Several bacteria, including E. coli, more effectively colonize mice when pretreated with streptomycin (34–37), and SPD may similarly allow for E. coli colonization via disruption of other bacteria that occupy and compete for niches within the gut microbiota. Biological sex is an important modulator of the microbiome (38). Although we showed directionally similar effects in mortality of female SPD+/+ versus SPD−/− mice, we did not examine for sex-related differences in the microbiome between male and female mice. Finally, although our study suggests important extrapulmonary effects of SPD in a preclinical model of sepsis, the importance of the relationship between E. coli and SPD in humans remains unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that absence of SPD confers protection from experimental sepsis by regulating gut colonization with E. coli. Our work demonstrates a novel role for SPD in the pathogenesis of sepsis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Andrew Onderdonk and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital microbiology laboratory for help with initial cultures. We thank Drs. Dennis Kasper, Richard Blumberg, and Michael Beers for helpful discussions. We thank Drs. Brooke King and Paul Kingma for assistance with obtaining SPD−/− mice.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

Drs. Varon and Arciniegas contributed equally.

Drs. Englert and Baron contributed equally.

New address: Current address for Dr. Amador-Munoz: Neuroscience (NEUROS) Research Group, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia; Mr. Corcoran: University of Cincinnati Medical School, Cincinnati, OH; Mr. DeCorte: Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN; Ms. Isabelle: Thomas Jefferson University Medical School, Philadelphia, PA; Dr. Pinilla Vera: Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD; Mr. Brown: Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Supported, in part, by R01 HL142093-01 and R01 GM115605 to Dr. Baron and K08 GM102695 to Dr. Englert.

Dr. Baron reports serving on Advisory Boards for Merck and Genentech. Dr. Kitsios has received research funding from Karius. Dr. McVerry receives research funding from Bayer Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. : The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315:801–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varon J, Baron RM: A current appraisal of evidence for the approach to sepsis and septic shock. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2019; 6:2049936119856517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. : Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47:1181–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delano MJ, Ward PA: Sepsis-induced immune dysfunction: Can immune therapies reduce mortality? J Clin Invest 2016; 126:23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JR: Immunoregulatory functions of surfactant proteins. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5:58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du J, Abdel-Razek O, Shi Q, et al. : Surfactant protein D attenuates acute lung and kidney injuries in pneumonia-induced sepsis through modulating apoptosis, inflammation and NF-κB signaling. Sci Rep 2018; 8:15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeVine AM, Whitsett JA, Hartshorn KL, et al. : Surfactant protein D enhances clearance of influenza A virus from the lung in vivo. J Immunol 2001; 167:5868–5873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarashina-Kida H, Negishi H, Nishio J, et al. : Gallbladder-derived surfactant protein D regulates gut commensal bacteria for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:10178–10183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korfhagen TR, Sheftelyevich V, Burhans MS, et al. : Surfactant protein-D regulates surfactant phospholipid homeostasis in vivo. J Biol Chem 1998; 273:28438–28443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, et al. : Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol 2020; 18:e3000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SW, Liu X, Macias AA, et al. : Heme oxygenase-1–derived carbon monoxide enhances the host defense response to microbial sepsis in mice. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, et al. : Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc 2009; 4:31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredenburgh LE, Velandia MM, Ma J, et al. : Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency leads to intestinal barrier dysfunction and increased mortality during polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol 2011; 187:5255–5267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMarsh PL, Wells GI, Lewandowski TF, et al. : Treatment of experimental gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial sepsis with the hematoregulatory peptide SK&F 107647. J Infect Dis 1996; 173:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn DL, Rotstein OD, Simmons RL. Fibrin in peritonitis. Arch Surg 1984; 119:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.York MK, Baron EJ, Clarridge JE, et al. : Multilaboratory validation of rapid spot tests for identification of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38:3394–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pantoja-Feliciano IG, Clemente JC, Costello EK, et al. : Biphasic assembly of the murine intestinal microbiota during early development. ISME J 2013; 7:1112–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fay KT, Klingensmith NJ, Chen CW, et al. : The gut microbiome alters immunophenotype and survival from sepsis. FASEB J 2019; 33:11258–11269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madsen J, Kliem A, Tornoe I, et al. : Localization of lung surfactant protein D on mucosal surfaces in human tissues. J Immunol 2000; 164:5866–5870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stidsen JV, Khorooshi R, Rahbek MK, et al. : Surfactant protein d deficiency in mice is associated with hyperphagia, altered fat deposition, insulin resistance, and increased basal endotoxemia. PLoS One 2012; 7:e35066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida M, Whitsett JA: Alveolar macrophages and emphysema in surfactant protein-D-deficient mice. Respirology 2006; 4 (11 Suppl):S37–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adelman MW, Woodworth MH, Langelier C, et al. : The gut microbiome’s role in the development, maintenance, and outcomes of sepsis. Crit Care 2020; 24:278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonten M, Johnson JR, van den Biggelaar AHJ, et al. : Epidemiology of Escherichia coli bacteremia: A systematic literature review. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:1211–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamburini FB, Andermann TM, Tkachenko E, et al. : Precision identification of diverse bloodstream pathogens in the gut microbiome. Nat Med 2018; 24:1809–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedberg DE, Zhou MJ, Cohen ME, et al. : Pathogen colonization of the gastrointestinal microbiome at intensive care unit admission and risk for subsequent death or infection. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:1203–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw AG, Sim K, Randell P, et al. : Late-onset bloodstream infection and perturbed maturation of the gastrointestinal microbiota in premature infants. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0132923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graspeuntner S, Waschina S, Künzel S, et al. : Gut dysbiosis with bacilli dominance and accumulation of fermentation products precedes late-onset sepsis in preterm infants. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carl MA, Ndao IM, Springman AC, et al. : Sepsis from the gut: The enteric habitat of bacteria that cause late-onset neonatal bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:1211–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alverdy JC, Keskey R, Thewissen R: Can the cecal ligation and puncture model be repurposed to better inform therapy in human sepsis? Infect Immun 2020; 88:e00942–e00919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burberry A, Wells MF, Limone F, et al. : C9orf72 suppresses systemic and neural inflammation induced by gut bacteria. Nature 2020; 582:89–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prescott HC, Dickson RP, Rogers MA, et al. : Hospitalization type and subsequent severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192:581–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, et al. : The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2014; 124:1174–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuan SF, Rust K, Crouch E: Interactions of surfactant protein D with bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Surfactant protein D is an Escherichia coli-binding protein in bronchoalveolar lavage. J Clin Invest 1992; 90:97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roxas JL, Koutsouris A, Bellmeyer A, et al. : Enterohemorrhagic E. coli alters murine intestinal epithelial tight junction protein expression and barrier function in a Shiga toxin independent manner. Lab Invest 2010; 90:1152–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Que JU, Hentges DJ: Effect of streptomycin administration on colonization resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in mice. Infect Immun 1985; 48:169–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Que JU, Casey SW, Hentges DJ: Factors responsible for increased susceptibility of mice to intestinal colonization after treatment with streptomycin. Infect Immun 1986; 53:116–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lye DJ: A mouse model for characterization of gastrointestinal colonization rates among environmental Aeromonas isolates. Curr Microbiol 2009; 58:454–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markle JGM, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 2013; 339:1084–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]