Abstract

Introduction

Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-2 (LEAP2) is an endogenous ghrelin receptor antagonist, which is upregulated in the fed state and downregulated during fasting. We hypothesized that the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) is involved in the downregulation of LEAP2 during conditions with high circulating levels of BHB.

Methods

Hepatic and intestinal Leap2 expression were determined in 3 groups of mice with increasing circulating levels of BHB: prolonged fasting, prolonged ketogenic diet, and oral BHB treatment. LEAP2 levels were measured in lean and obese individuals, in human individuals following endurance exercise, and in mice after BHB treatment. Lastly, we investigated Leap2 expression in isolated murine hepatocytes challenged with BHB.

Results

We confirmed increased circulating LEAP2 levels in individuals with obesity compared to lean individuals. The recovery period after endurance exercise was associated with increased plasma levels of BHB levels and decreased LEAP2 levels in humans. Leap2 expression was selectively decreased in the liver after fasting and after exposure to a ketogenic diet for 3 weeks. Importantly, we found that oral administration of BHB increased circulating levels of BHB in mice and decreased Leap2 expression levels and circulating LEAP2 plasma levels, as did Leap2 expression after direct exposure to BHB in isolated murine hepatocytes.

Conclusion

From our data, we suggest that LEAP2 is downregulated during different states of energy deprivation in both humans and rodents. Furthermore, we here provide evidence that the ketone body, BHB, which is highly upregulated during fasting metabolism, directly downregulates LEAP2 levels. This may be relevant in ghrelin receptor–induced hunger signaling during energy deprivation.

Keywords: energy deprivation, exercise, ketone bodies, ketogenic diet, LEAP2

The hypothalamus serves a critical function in appetite and body weight (BW) regulation by sensing and integrating local and peripheral signals, consequently balancing energy status (1, 2). Ghrelin, a stomach-derived 28-amino acid peptide hormone, is the only known endogenous orexigenic peptide hormone that acts directly in the hypothalamus (3, 4). Conversely, leptin is secreted from the adipocytes and circulates in the blood in proportion to adipose tissue content, with the primary physiological role to serve as a long-term energy regulator, by acting in the hypothalamus (5, 6). A reduction in adipose tissue, hence circulating leptin levels, initiates counterregulatory signals including increased eating and a reduction in energy consuming processes (5, 6). Another central physiological response during energy deprivation is hepatic metabolic adaptations to control energy homeostasis and continue production and secretion of nutrients through gluconeogenesis (7, 8). This is driven by a dramatic increase in hepatic fatty acid oxidation (FAO), providing bioenergetics such as ATP and NADH to facilitate gluconeogenesis (9). A byproduct of hepatic FAO is ketone bodies which are generated through ketogenesis and function as alternative but important fuel sources for highly oxidative tissues such as the brain and cardiomyocytes (10-12). The plasma levels of ketone bodies increase during fasting, after exercise, and during carbohydrate-deprived ketogenic diet, all where energy production relies on FAO (10-16). Hepatic FAO has also been implicated in the control of food intake (17-21). Despite controversial results as to whether inhibition or stimulation of hepatic FAO increases food intake, recent results have demonstrated that increased hepatic FAO stimulates eating after prolonged food deprivation in rodents (17, 18). However, the underlying mechanisms for this biology remain unknown. While these findings emphasize a connection between liver metabolism and appetite regulation, a putative circulating liver-derived factor mediating these effects has not yet been identified. Recently, liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-2 (LEAP2) was indicated to function as an endogenous antagonist and inverse agonist of the ghrelin receptor (22-25). The ghrelin receptor is known to have almost 50% constitutive activity; hence, it signals without any ghrelin hormone present (26, 27), which has been proposed to be of physiological importance in constitutive stimulation of basal food intake (26, 27). This concept was supported by the discovery of LEAP2 as an endogenous inhibitor of both the ghrelin-mediated stimulation and of the spontaneous signaling of the ghrelin receptor (22-25). LEAP2 reduces food intake and growth hormone secretion in mice (22, 28) and LEAP2 deletion enhances ghrelin’s actions in female mice (29). Thus, LEAP2 appears to constitute another important liver-produced factor controlling central appetite regulation. LEAP2 is expressed and secreted from the liver and small intestines (22, 25). The appetite suppressing hormone is upregulated by body mass in rodents and humans and is regulated opposite to that of ghrelin during fed and prolonged fasted state in rodents (22, 23, 25). Furthermore, LEAP2 is positively correlated to pancreatic peptide in rodents in contrast to ghrelin (30). The plasma levels of LEAP2 increase with high blood glucose levels in rodents (23); however, the specific metabolites and/or nutritional factors governing the regulation of LEAP2 during fasting metabolism remain undescribed (31).

In the present study, we investigated the regulation of LEAP2 during exposure to high but physiological levels of BHB. As LEAP2 is downregulated during fasting, we hypothesized that the most abundant ketone body in plasma during energy deprivation, BHB, is involved in the downregulation of LEAP2 expression and secretion from hepatocytes.

Methods

Plasma Samples From Lean and Obese Human Individuals

Individuals with obesity

Fasting plasma samples were obtained from 20 humans with obesity referred to elective Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery. Baseline plasma samples were measured from before preoperative diet-induced weight loss and LEAP2 levels have been reported in a recent publication (32) with a focus on the effect on LEAP2 after weight loss and RYGB. For detailed participation characteristics and experimental design, we refer to Jorsal et al (2020) (33). In short, 5 males and 15 females participated (baseline characteristics: median [IQR] age 46.5 [39.0-50.8] years, BMI 40.3 [36.3-43.6] kg/m2, hemoglobin A1c 33 [30-34] mmol/mol). Three subjects were excluded due to diagnosis with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes. Blood samples were collected from an intravenous catheter inserted into an antecubital vein. The arm for blood sampling was wrapped in a heating pad (45 °C) to arterialize the venous blood. Blood was collected in chilled P800 K2EDTA tubes containing a cocktail of protease, esterase, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (#366420, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and tubes were centrifuged for 15 minutes (2900g, 4 °C). Plasma was extracted from the blood and kept at −80 °C until analysis.

Lean individuals

Fasting plasma samples were taken from 10 young healthy lean men aged 23 (22-24) years and with an average BMI of 22.5 (21.9-22.8) kg/m2 at 2 separate days. Plasma samples have been used in a recent publication (32) and were collected and stored as described above. LEAP2 plasma levels in these subjects were not reported in the publication.

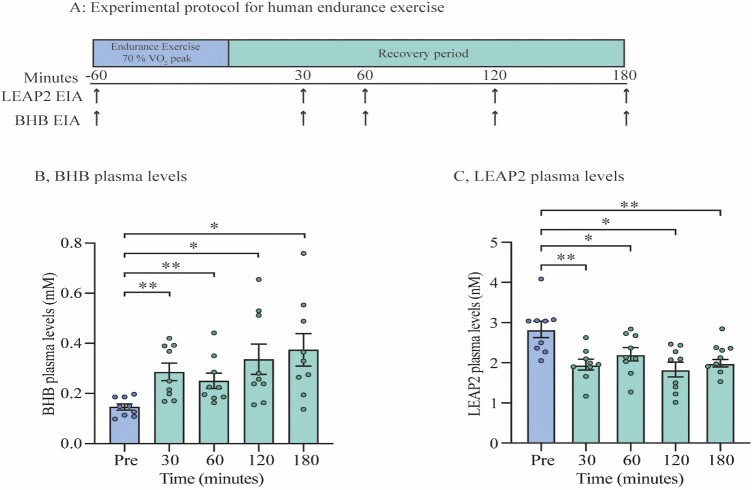

Human Exercise Study

Plasma samples from 9 healthy recreationally active men were analyzed. These samples have been used in a previous publication (34). We investigated the plasma samples from participants before and after endurance exercise. In the morning after an overnight fast, all individuals performed 60 minutes of exercise on a bike ergometer, composed of 10 minutes warm-up (100 watts and 150 watts for 5 minutes each) following 50 minutes bike exercise of individualized 70% VO2 peak workload. Blood samples were taken before exercise and 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes after termination of exercise, in EDTA tubes (Fig. 2A for schematic protocol). For this study, plasma samples before exercise and 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes after exercise were analyzed. Blood samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes (3756g, 4 °C) and plasma was separated and kept at −80 °C until analyses.

Figure 2.

Circulating LEAP2 decrease in response to exercise while BHB levels increase. (A) Experimental protocol for human endurance exercise study, (B) Time course of BHB plasma levels on the following time points; before endurance exercise, and 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes after exercise (C) Time course of LEAP2 plasma levels on the following timepoints; before endurance exercise, and 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes after exercise. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA repeated measures followed by Tukey post hoc test (B-C) n = 9. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. Abbreviations: BHB; beta-hydroxybutyrate, EIA; enzyme immunoassay, LEAP2; liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2.

Animals

Male C57BL/J mice (Janvier breeding center, France) with ad libitum access to water and a chow diet (Altromin, 1310, Brogaarden, Denmark) were housed in a temperature-controlled (22 °C) environment under a 12:12 hour light-dark cycle with a 1- to 2-week acclimatization period, unless otherwise stated.

In Vivo Experimental Studies

Ad libitum–fed and fasted mice

Mice were either ad libitum–fed with chow diet or fasted for 24 hours. The day after, mice were decapitated and liver biopsies from left lateral lobe, duodenum (2-6 cm distally from the pyloric sphincter), and jejunum (10-16 cm distally to the pyloric sphincter) were isolated from all mice and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were kept at −80 °C until analysis.

In vivo administration of BHB

Male mice (16-18 weeks of age) (20-22 weeks old in Supplementary Figure 2 (35)) were randomized by BW and were divided into either vehicle or BHB-treated groups. All mice were deprived from food 2 hours before the experiment and subsequently dosed orally with either BHB (100 mg/kg BW; 150-83-4, Sigma Aldrich, Germany) or vehicle (ddH2O) (dose volume: 0.1 mL/10g BW). Blood glucose was measured from a tail puncture before and 2 hours after administration. After 2 hours, blood, liver, duodenum, and jejunum were collected as previously described within 30 seconds following euthanization and were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Blood samples were collected from the orbital sinus into EDTA-coated tubes containing aprotinin (A1153, Sigma Aldrich, Germany) (final concentration of 0.6 TIU). Blood samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes (8000g, 4 °C) and plasma was separated. All samples were kept at −80 °C until analyses.

Ketogenic diet study

Adult male mice (8 weeks) were placed on either a standard chow diet or a high-fat diet (HFD) (60% kcal from fat, D12492, Research Diets, USA) for 20 weeks. Mice were group-housed with up to 8 mice per cage. Prior to the ketogenic diet study all mice were single-housed and acclimatized for 2 weeks. BW was measured every 2 to 3 days and MRI scanned once per week. Mice were placed in the following diet groups at start of the ketogenic study (see Fig. 3A): 14 chow-fed mice were divided into a group that continued chow diet (GroupChow) (n = 7) and a group that was switched to ketogenic diet (GroupChow-KD) (n = 7) (75.1% kcal from fat, 3.2% kcal from carbohydrate, F3666, Bioserv, New Jersey, USA) for 3 weeks. Twenty-eight mice that had been fed a 60% HFD were divided into 3 groups; a group that continued on HFD (GroupHFD) (n = 10), a group that was switched to normal chow diet (GroupHFD-Chow) (n = 9) and a group that was switched to ketogenic diet (GroupHFD-KD) (n = 9) for 3 weeks. Prior to study termination, BW was measured and blood glucose and BHB levels were measured by a tail puncture. Mice were decapitated and liver and duodenum samples were collected as previously described during dark phase in nonfasted mice.

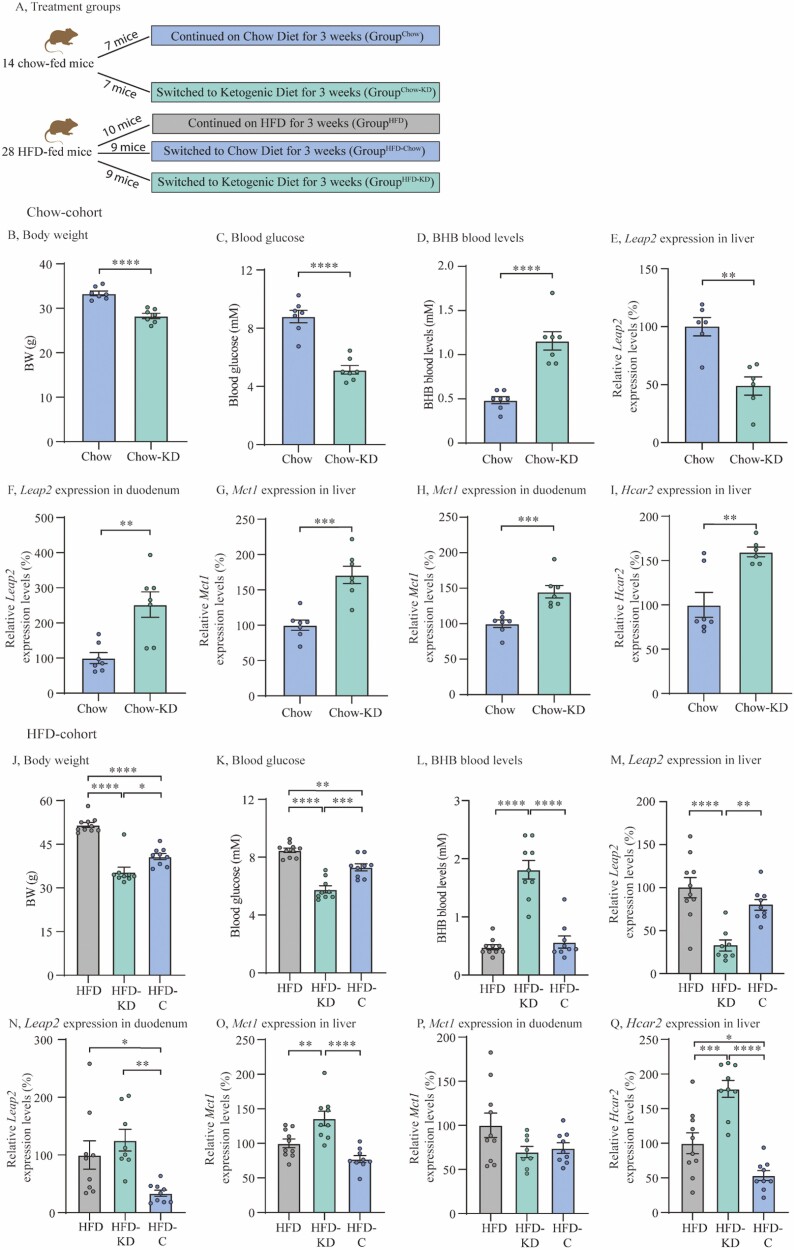

Figure 3.

Ketogenic diet downregulates Leap2 expression in mouse liver. (A) Treatment groups, (B) BW in chow-cohort, (C) Blood glucose levels in chow-cohort, (D) BHB blood levels in chow-cohort, (E) Relative Leap2 expression levels in liver in chow-cohort, (F) Relative Leap2 expression levels in duodenum in chow-cohort (G) Relative Mct1 expression levels in liver in chow-cohort, (H) Relative Mct1 expression levels in duodenum in chow-cohort, (I) Relative Hcar2 expression levels in liver in chow-cohort, (J) BW in HFD-cohort, (K) Blood glucose levels in HFD-cohort, (L) BHB blood levels in HFD-cohort, (M) Relative Leap2 expression levels in liver in HFD-cohort, (N) Relative Leap2 expression levels in duodenum in HFD-cohort, (O) Relative Mct1 expression levels in liver in HFD-cohort, (P) Relative Mct1 expression levels in in duodenum in HFD-cohort, (Q) Relative Hcar2 expression levels in in liver in HFD-cohort. Data were normalized to reference gene Ywhaz and subsequently normalized to either chow or HFD control (E-I and M-Q, respectively). Data were analyzed by unpaired t test (B-I), and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test (J-Q). GroupChow, n = 7; GroupChow-KD, n = 7; GroupHFD, n = 10; GroupHFD-KD, n = 9; GroupHFD-Chow n = 9. Outliers were identified and exclusion of outlier did not diverge from the results of the main analysis and result (E, I, M, N, P). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: BHB; beta-hydroxybutyrate, HFD; high-fat diet, Leap2; Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2.

Ex vivo experimental study

Isolation of mouse hepatocytes was based on a previously published protocol (36). Male mice (8-10 weeks of age) were used in this study. After overnight incubation, isolated hepatocytes were incubated in Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate (KRB) buffer (pH 7.4, 1 × KRB buffer, HEPES (15630-056, Gibco), NaOH (25080-060, Gibco), 2mM glucose) (control) and stimulated with either BHB (either 1 or 10 mM) (A1153, Sigma Aldrich), trichostatin A (TSA) (10nM or 100nM) (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. no. 58880-19-6), TMP269 (0.1uM, 1uM or 10uM) (Selleckchem Cat. no. S7324) or AR319277 (AR277) (10nM, 100nM or 1uM) (Arena Pharmaceuticals, CA, USA) in duplicates, triplicates, or quadruplicates for 4 hours at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After stimulation, media was removed and cells were lysed in RLT buffer:beta mercaptoethanol (100:1) (74034, Qiagen, Germany). All lysates were kept at −80 °C until analysis. Mice were normalized independently and collected in the same analysis; n is the number of biologically independent samples for which data were averaged from duplicate, triplicate, or quadruplicate measurements.

Measurements of LEAP2 Plasma Levels

Human and mouse plasma LEAP2 concentrations were assessed by use of a specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for human LEAP2 detection (EK-075-40 Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, USA, RRID:AB_2909436, https://scicrunch.org/resources/Any/search?q=ab_2909436&l=ab_2909436). The plasma concentrations of LEAP2 were measured and calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

BHB Measurements

Human and mouse blood and plasma BHB levels were measured by FreeStyle Precision Neo (Blood β-Ketone Test Strips, Abbott, USA) or by use of a Beta-Hydroxybutyrate AssayKit (MAK041, Sigma Aldrich). The assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantification of RNA Levels

Liver biopsies and small intestinal samples and cultured hepatocytes were lysed, and RNA was extracted using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (1023539, Qiagen) or RNeasy PLUS Tissue Micro Kit (74034, Qiagen), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity of RNA was determined on a Nanodrop (Nanodrop 2000, Spectrophotometer). The cDNA synthesis was done using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (18080400, Invitrogen, USA). The quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed by use of QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (PPLUS-machine type-20ML,Invitrogen) in a MicroAmp Optical 384-well Reaction Plate (Thermo Fisher [Invitrogen]). Program: (95 °C for 30 seconds, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 30 seconds, and 60 seconds at 60 °C) All expression data were normalized by the 2^(ΔCt) method. Tyrosine 3- monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein zeta polypeptide (Ywhaz) was used as reference gene.

The following primers were used; Hcar2 forward 5′-3′ (ATGAAAACATCGCCAAGGTC) reverse 3′-5′ (TGGATTTCCAGGACTTGAGG), Leap2 forward 5′-3′ (AATGACCCCATTTTGGAGAG) reverse 3′-5′ (CACACTTAGGGAACAGCGTCT), Mct1 forward 5′-3′ (CATTGGTGTTATTGGAGGTC) reverse 3′-5′ (GAAAGCCTGATTAAGTGGAG), Ywhaz forward 5′-3′ (AGACGGAAGGTGCTGAGAAA) reverse 3′-5′ (GAAGCATTGGGGATCAAGAA).

Statistics

All statistical evaluations were processed in GraphPad Prism (8.4.3, GraphPad, USA). All data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), unless otherwise stated. Data were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with or without repeated measures. When analysis of variance revealed significant differences, a Tukey post hoc test was used to correct for multiple comparisons. A ROUT outlier test was used to identify outliers. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and is denoted as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

Study Approvals

Human studies were approved by the local ethics committee of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg (H-17030450) or the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-6-2014-047 and H-18027152). All human studies were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All rodent experiments were approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (license: 2019-15-0201-00289) and performed according to institutional guidelines.

Results

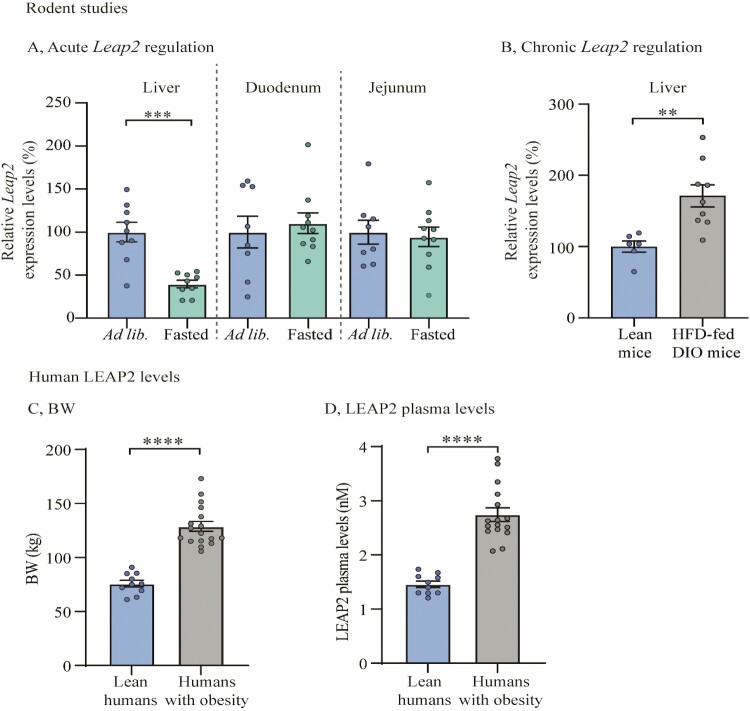

LEAP2 Levels Decrease With Fasting and Increase With Obesity

It has previously been indicated that plasma levels of LEAP2 decrease after prolonged fasting in rodents (22, 23, 25). Here, we confirmed that Leap2 expression was significantly suppressed in the liver after 24 hours of fasting as compared to ad libitum–fed mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). Notably, we did not observe any difference in Leap2 expression in response to fasting in duodenum nor jejunum (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Figure 1 for threshold cycle (CT) values (37)).

Figure 1.

LEAP2 levels decrease by fasting and increase with obesity. (A) Relative Leap2 mRNA expression levels from liver, duodenum, and jejunum samples in 2 treatment groups; ad libitum–fed (ad lib.) mice and mice fasted for 24 hours; n = 9 in ad libitum–fed and n = 10 fasted mice (B) Relative Leap2 mRNA expression levels from liver in 2 groups; lean and HFD-fed DIO mice; n = 6 in lean mice and 9 in HFD-fed DIO mice (C) Mean BW of lean vs obese human individuals; lean human individuals n = 10 (averaged from 2 separate days), obese human individuals n = 17 (D) LEAP2 plasma levels in lean vs obese human individuals; lean human individuals n = 10 (averaged from 2 separate days), obese human individuals n = 17. Data were normalized to reference gene Ywhaz and subsequently normalized to corresponding control (A-B). Data were analyzed by unpaired t test. One outlier was identified and excluded due to technical error and exclusion of outlier did not diverge from the results of the main analysis and result (A [fasted mice in duodenum and jejunum] , in both lean and HFD-fed DIO mice (1 in each) and D in humans with obesity. ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. Abbreviations: DIO; diet-induced obesity, HFD; high-fat diet, LEAP2; liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2.

These findings suggest that Leap2 expression is selectively decreased in the liver during energy deprivation.

It has been demonstrated that the plasma levels of LEAP2 increase with body mass in humans and rodents (23). Here, we found increased Leap2 expression in the liver by approximately 70% in HFD-fed diet-induced obese (DIO) mice as compared with chow-fed lean mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B). We also confirmed that circulating plasma levels of LEAP2 were approximately 100% higher in humans with obesity than in lean individuals (Fig. 1C and 1D) (23); yet a caveat to these data is an age difference of more than 10 years between the 2 groups of individuals. However, whether there is an interaction between age and LEAP2 levels in humans remains undescribed.

These results suggest that LEAP2 is regulated by metabolic status in both rodents and humans and that Leap2 expression is downregulated by fasting selectively in the liver.

Circulating LEAP2 Decreases in Response to Exercise While BHB Levels Increase

Next, we aimed to investigate whether LEAP2 levels decrease in other states of energy deprivation in humans. Prolonged endurance exercise induces a state of energy deficiency, depending on intensity and duration of exercise (12), similar to long-term fasting where plasma levels of BHB are increased, also referred to as postexercise ketosis (13, 16). We therefore tested LEAP2 plasma levels in the recovery period following exercise in human individuals. In this study, humans performed bike exercise of 70% VO2 peak workload for 50 minutes and blood samples were taken before and after exercise (Fig. 2A for study design). As expected, plasma levels of BHB almost doubled with an increase from 0.15 ± 0.01 mM to 0.29 ± 0.03 mM as soon as 30 minutes after exercise (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). The highest mean plasma levels of BHB were detected 180 minutes after exercise with 0.37 ± 0.07 mM, equivalent to a 147% increase from baseline levels (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). In contrast to BHB levels, we found significantly reduced LEAP2 plasma levels from 2.8 ± 0.2 nM before exercise to 1.9 ± 0.2 nM 30 minutes after exercise (Fig. 2C), equivalent to a 31% reduction (P < 0.01). The reduction in plasma levels of LEAP2 remained significantly reduced at all time points from 30 minutes to 180 minutes after exercise compared with baseline levels.

Thus, the reduction in circulating LEAP2 levels after exercise in man is compatible with the notion that BHB is involved; however, many other mechanisms and/or factors could be in play.

Ketogenic Diet Downregulates Leap2 Expression in Mouse Liver

To further investigate whether BHB is linked to the regulation of LEAP2, we treated mice with a ketogenic diet, containing high amounts of fat and low amounts of carbohydrates, which consequently increases hepatic FAO and accordingly circulating levels of ketone bodies (12, 15). We investigated the effect of exposure to a ketogenic diet for 3 weeks on liver and intestinal expression levels of Leap2 in 2 cohorts: previously chow-fed lean mice and HFD-fed DIO mice (Fig. 3A and “Methods: In Vivo Experimental Studies: Ketogenic diet study” for study setup). In brief, the chow-fed lean mice (GroupChow) were compared to a cohort of lean mice that were switched to ketogenic diet for 3 weeks (GroupChow-KD). The HFD-fed DIO mice (GroupHFD) were compared to a cohort of mice that were switched to ketogenic diet for 3 weeks (GroupHFD-KD) and, importantly, also to a cohort of DIO mice that instead were switched to ordinary chow for 3 weeks (GroupHFD-Chow).

In accordance with the literature (38), we observed reduced BW and blood glucose in ketogenic diet treated mice (GroupChow-KD) compared to lean mice kept on ordinary chow (GroupChow) (P < 0.0001 for both), despite the higher energy content of the ketogenic diet compared to the chow diet (Fig. 3B and 3C). Circulating BHB levels were 2.5-fold higher in GroupChow-KD than in GroupChow: 1.2 ± 0.1 mM compared with 0.5 ± 0.04 mM, respectively (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3D). Notably, liver expression of Leap2 was reduced by 45% in GroupChow-KD as compared with GroupChow (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3E). Conversely, duodenal Leap2 expression was increased by almost 2-fold in GroupChow-KD compared with GroupChow (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3F).

We also measured the expression levels of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (Mct1), which transports lactate and ketone bodies across the cell membrane of various tissues (39). In both liver and duodenal tissue, we found significantly increased Mct1 expression levels in GroupChow-KD compared to GroupChow (P < 0.001 for both) (Fig. 3G and 3H). Additionally, we measured the expression levels of the endogenous surface receptor for BHB, the G protein–coupled receptor hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (Hcar2), and found increased liver expression levels of Hcar2 in GroupChow-KD compared with GroupChow (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3I).

In DIO mice switched to a ketogenic diet (GroupHFD-KD), BW was significantly lower as compared with mice kept on HFD (GroupHFD) (36 ± 0.5 g vs 52 ± 0.9 g) (P < 0.0001) and mice changed to a chow diet (GroupHFD-Chow) (41 ± 1 g) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3J). BW was likewise significantly lower in GroupHFD-Chow compared with GroupHFD (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3J). Blood glucose was also significantly lower in GroupHFD-KD (5.8 ± 0.2 mM) as compared to GroupHFD (8.5 ± 0.2 mM) and GroupHFD-Chow (7.3 ± 0.2 mM) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3K). Additionally, GroupHFD-Chow had significantly lower blood glucose levels compared with GroupHFD (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3K).

Circulating BHB levels were almost 4-fold higher in GroupHFD-KD compared with GroupHFD (1.8 ± 0.2 mM vs 0.5 ± 0.04 mM) (P < 0.0001) and 3-fold higher compared with GroupHFD-Chow (0.6 ± 0.1 mM) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3L), while liver Leap2 expression was reduced by 67% in GroupHFD-KD compared with GroupHFD (P < 0.0001) and by 59% compared with GroupHFD-Chow (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3M). Neither circulating BHB nor liver Leap2 expression were significantly different between GroupHFD and GroupHFD-Chow (Fig. 3L and 3M). Notably, duodenal Leap2 expression was significantly higher in GroupHFD and GroupHFD-KD compared with GroupHFD-Chow (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 3N).

Liver Mct1 expression was increased in GroupHFD-KD as compared with GroupHFD (P < 0.01) and with GroupHFD-Chow (P < 0.0001), with no changes in liver Mct1 expression between GroupHFD and GroupHFD-Chow (Fig. 3O) and in duodenal Mct1 expression levels in the HFD-cohort (Fig. 3P).

Additionally, liver expression levels of Hcar2 were significantly higher in GroupHFD-KD as compared with GroupHFD (P < 0.001) and GroupHFD-Chow (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3Q). Furthermore, liver Hcar2 expression levels were significantly higher in GroupHFD as compared with GroupHFD-Chow (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3Q).

From these data we suggest that Leap2 regulation after ketogenic diet is tissue dependent. We demonstrated that liver Leap2 expression decreases in response to ketogenic diet and high levels of BHB. Despite recent findings that LEAP2 is dependent on BW and blood glucose levels (23), we suggest that the findings in our ketogenic diet study are independent of changes in these factors, as we found no difference in liver Leap2 expression nor BHB levels between GroupHFD and GroupHFD-Chow, where we found a difference in BW and blood glucose. However, the changes in BW but not in hepatic Leap2 expression in GroupHFD-Chow are in contrast to previous findings in which investigators used similar manipulations (23). Furthermore, we found increased liver expression levels of both the ketone body transporter Mct1 and the BHB receptor Hcar2 in mice receiving a ketogenic diet as compared to both chow and HFD-fed mice.

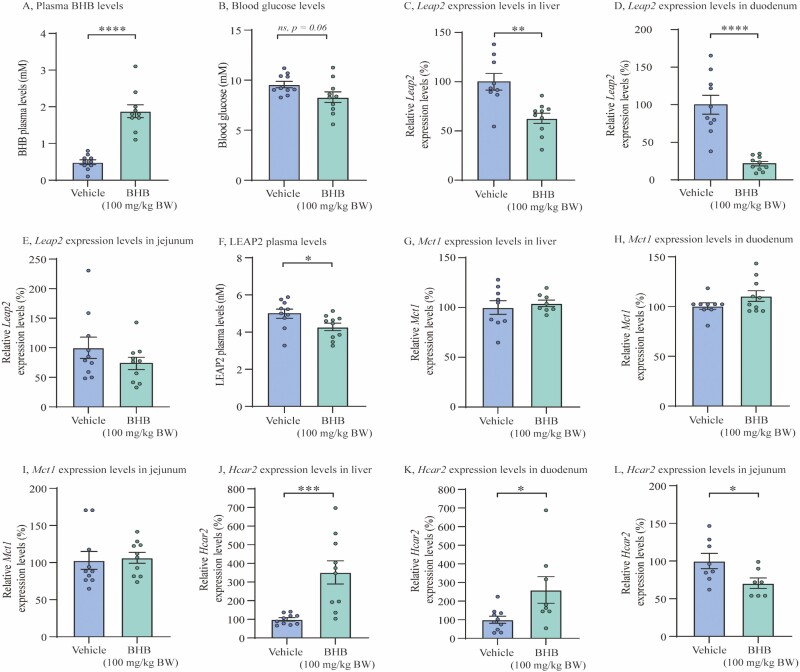

In Vivo Administration of Exogenous BHB Downregulates Circulating LEAP2 Levels and Leap2 Expression in Mouse Liver and Duodenum

Not only BHB, but many different circulating metabolites change in response to fasting, exercise, and ketogenic diet (14, 34, 38). As we found a downregulation of liver Leap2 expression following a ketogenic diet, we investigated whether BHB directly affects hepatic LEAP2 expression and secretion by administering BHB or vehicle orally to lean chow-fed mice, thus excluding other confounding factors. As expected, BHB treatment induced significantly higher plasma levels of BHB 2 hours after administration, yet we found a tendency in blood glucose difference between the 2 groups (Fig. 4A and 4B and Supplementary Figure 2 (35)). Importantly, we found that Leap2 expression was significantly reduced in the liver and in duodenum of mice treated with BHB compared with vehicle, 2 hours after oral administration (Fig. 4C and 4D and Supplementary Figure 2 (35)) (P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively). No changes were detected in jejunum (Fig. 4E). Additionally, we demonstrated reduced plasma levels of LEAP2 after BHB treatment (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

In vivo administration of exogenous BHB downregulates circulating LEAP2 levels and Leap2 expression in mouse liver and duodenum. (A) Plasma levels of BHB in 2 treatment groups; vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), 2 hours after oral administration, (B) Blood glucose levels in 2 treatment groups; vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), 2 hours after oral administration, (C-E) Relative Leap2 expression levels in 2 treatment groups; vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), in liver, duodenal, and jejunal, respectively, 2 hours after oral administration, (F) Systemic LEAP2 plasma levels from vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), 2 hours after oral administration, (G-I) Relative Mct1 expression levels in 2 treatment groups; vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), in liver, duodenal, and jejunal, respectively, 2 hours after oral administration, (J-L) Relative Hcar2 expression levels in 2 treatment groups; vehicle and BHB (100 mg/kg BW), in liver, duodenum, and jejunum, 2 hours after oral administration. Data were normalized to reference gene Ywhaz and subsequently normalized to vehicle (C-E + G-L). All data were analyzed by unpaired t test. n = 10 in each group. Outliers were identified and exclusion of outlier did not diverge from the results of the main analysis and result (C, G, H, K, L). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001, ns = not significant. Abbreviations: BHB; beta-hydroxybutyrate, Hcar2; hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2, LEAP2/Leap2; Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2, Mct1; monocarboxylate transporter 1.

Mct1 expressions were unchanged with BHB treatment in both liver and small intestines (Fig. 4G and 4I); however, we found increased expression levels Hcar2 in the liver (P < 0.001) and duodenum (P < 0.05) but reduced Hcar2 expression levels in jejunum (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4J-4L).

Thus, a selective and acute increase in circulating BHB levels obtained through oral administration of the ketone body BHB reduced liver and duodenal expression of Leap2 and systemic LEAP2 plasma levels. Furthermore, we found increased liver and duodenal Hcar2 expression but reduced jejunal expression levels. No changes were detected in Mct1 expression in any of the tissues after oral BHB administration.

Leap2 Expression Is Downregulated by BHB in Isolated Mouse Hepatocytes

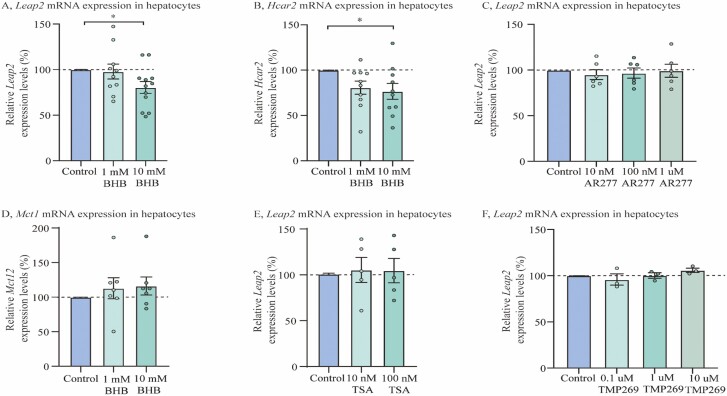

To investigate whether BHB-induced Leap2 regulations in the liver were due to a direct effect on liver cells, we investigated the effects of BHB in isolated murine hepatocytes. Leap2 expression was downregulated by 19% in isolated mouse hepatocytes stimulated with 10 mM exogenous BHB compared with control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A; 4 individual preparations are shown in Supplementary Figure 3 (40)). We also investigated whether Hcar2 was affected by BHB stimulation and found significantly decreased Hcar2 expressions in hepatocytes stimulated with 10 mM exogenous BHB compared to control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Leap2 expression is downregulated by BHB in isolated mouse hepatocytes. (A) Relative Leap2 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 1 and 10 mM BHB in mouse hepatocytes, (B) Relative Hcar2 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 1 and 10 mM BHB in mouse hepatocytes, (C) Relative Leap2 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1 uM AR277 in mouse hepatocytes, (D) Relative Mct1 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 1 and 10 mM BHB in mouse hepatocytes, (E) Relative Leap2 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 10 nM, 100 nM TSA in mouse hepatocytes, (F) Relative Leap2 expression levels after 4 hours incubation with 0.1 uM, 1 uM, and 10 uM TMP269 in mouse hepatocytes. Data from each mouse were normalized to reference gene Ywhaz and subsequently normalized to control and collected in the same analysis. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests (A-B). All data were presented as means ± SEM. n = 10-12 mice (A and B), 6 (C), 7 (D), 5 (E) and 3 (F). n is the number of biologically independent samples for which data were averaged from duplicate, triplicate, or quadruplicate measurements. * P < 0.05. Abbreviations: BHB; beta-hydroxybutyrate, Hcar2; hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2, Leap2; Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2, Mct1; monocarboxylate transporter 1, TSA; trichostatin a.

Despite opposite regulation of Hcar2 expression in vivo and ex vivo, we investigated whether the molecular mechanisms behind BHB-induced Leap2 regulation were mediated through the surface receptor HCAR2 by stimulating mouse hepatocytes with a synthetic selective agonist AR277. However, stimulation with AR277 did not affect Leap2 expression in mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 5C).

As BHB acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor (41), we investigated if the regulation of Leap2 expression by BHB was mediated via HDACs. We first measured the expression of Mct1 in hepatocytes, yet no regulation was detected after incubation with BHB (Fig. 5D). Subsequently, we stimulated mouse hepatocytes with different synthetic HDAC inhibitors, TSA and TMP269 (Fig. 5E-F). However, none of the HDAC inhibitors seemed to regulate Leap2 expression in mouse hepatocytes.

In summary, we demonstrated that BHB directly downregulated Leap2 expression in mouse hepatocytes, and further showed that the surface receptor Hcar2 was downregulated, presumably due to high and supraphysiological concentrations of BHB. No regulation was found in Mct1 or in Leap2 expression after incubation with either a HCAR2 agonist or HDAC inhibitors.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that the endogenous ghrelin receptor antagonist and inverse agonist LEAP2 is directly downregulated in plasma, liver, and duodenum by BHB administration in mouse and murine hepatocytes, and further inversely correlated with BHB levels after exercise in man. Additionally, we are the first to show a tissue-dependent regulation of Leap2 expression in mice after exposure to a ketogenic diet.

An association between BMI and plasma levels of LEAP2 has been reported in different cohorts of patients; however, results reported in the literature are inconsistent (23, 42-45). We confirmed that LEAP2 levels are regulated by BW in humans and mice (23). Conversely, we observed downregulated liver Leap2 expression after fasting, which led us to hypothesize that BHB may be involved in LEAP2 regulation, specifically in the liver. We therefore tested different states with high but physiological endogenous and exogenous levels of BHB on the regulation of LEAP2 levels.

LEAP2 After Exercise

It has been suggested that plasma levels of anorexigenic gastrointestinal hormones such as glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY increase in the acute period following exercise (46). These hormonal changes may contribute to a transient satiety frequently reported during and immediately following exercise (46). However, in the prolonged recovery period after exercise, increased appetite has been observed (47, 48). Mani et al (2018) found increased plasma levels of ghrelin after exercise and food deprivation (49). Furthermore, food intake was significantly higher in wild-type mice compared with ghrelin-receptor knockout mice after exercise (49), suggesting the importance of ghrelin and ghrelin receptor during exercise-induced hunger signalling during energy deprivation. In our study, we found reduced plasma levels of LEAP2 in the recovery period after exercise, which is in accordance with previous findings of inverse regulations of LEAP2 and ghrelin plasma levels (23). As LEAP2 has been shown to decrease the constitutive activity of the ghrelin receptor and furthermore to antagonize the actions of ghrelin (22), the decreased plasma levels of LEAP2 after exercise may contribute to further increase ghrelin receptor hunger signaling. Thus, we suggest that the suppression of LEAP2 levels after exercise may be of physiological relevance in order to replenish energy stores by increasing ghrelin receptor–induced appetite stimulation.

Leap2 Expression Is Regulated in a Tissue-Dependent Manner After a Ketogenic Diet

As a ketogenic diet drastically increases the circulating levels of endogenous BHB (12), we investigated the effect of a ketogenic diet on Leap2 expression. Here we found divergent tissue dependent regulations in Leap2 expression in response to a ketogenic diet, which may be a result of distinct nutritional sensing and metabolism. We found a downregulation of hepatic Leap2 expression in mice fed a ketogenic diet compared with controls in both cohorts. During a ketogenic diet, the liver utilizes free fatty acids to control energy homeostasis by increasing glyconeogenesis and hepatic FAO and ketogenesis, similar to fasting conditions. However, during ingestion of a normal HFD or chow diet, carbohydrates are available for energy consumption and glucose and triglycerides are instead stored in peripheral tissues (7, 50). Thus, we suggest that the downregulation of the anorexigenic Leap2 expression in the liver after ketogenic diet may be a compensatory response to sensing “low energy status” and may be important in order to maintain energy homeostasis by increasing ghrelin receptor–induced food intake. Conversely, we found higher duodenal Leap2 expression in ketogenic diet–fed mice compared with chow-fed mice in both cohorts. Although the liver is believed to be the main ketogenic organ in the body (11), intestinal cell lines have been implicated to upregulate the key enzymes in FAO and ketogenesis after high-fat exposure to a higher degree than that of liver cells (51, 52), hence increasing fat metabolism and ketogenesis. However, in contrast to hepatic FAO during ketogenic diet and the following downregulation of Leap2 expression, we suggest that the increased duodenal Leap2 expression after exposure to HFD and a ketogenic diet may be a response to sensing high amount of triglycerides as we found no difference in duodenal Leap2 expression between HFD-fed mice and mice receiving a ketogenic diet. Furthermore, prolonged fasting evidently did not affect Leap2 expression in the small intestines but only in the liver. Together, these results imply that liver and not intestinal Leap2 expression is regulated by fasting metabolism.

It is well described that prolonged ingestion of ketogenic diet and also oral ingestion of ketone esters, which increases circulating BHB levels, reduce food intake in both rodents and humans (38, 53-60). The appetite-regulating effects mediated by ketone bodies have, however, not been determined at a molecular or cellular level. It could be mediated by central actions in the brain independent of the regulation of LEAP2, for example, by a reduction in the circulating levels of ghrelin (58, 60), or by changes in peripheral hormone secretion through the free fatty acid receptor 3, which has been shown to be activated by BHB and also to be involved in short-chain fatty acid–dependent energy regulation (61). BHB may also affect the vagal afferents directly, as it has been implicated that the inhibitory effect of eating by peripheral exogenous BHB administration depends on intact vagal afferents (55, 59). Importantly, we found increased duodenal Leap2 expression after receiving ketogenic diet which could play a role in the satiety effects of ketogenic diet. However, whether duodenal regulation of Leap2 expression determines the physiological functions of LEAP2 in response to ketogenic diet remains unknown.

Taken together, we suggest that the downregulation of liver Leap2 expression in response to a ketogenic diet may be a compensatory response to induce hunger during sensing of low nutritional status, whereas high expression levels of duodenal Leap2 may be a result of sensing fat and high energy status and contribute to the satiety effects of ketogenic diet.

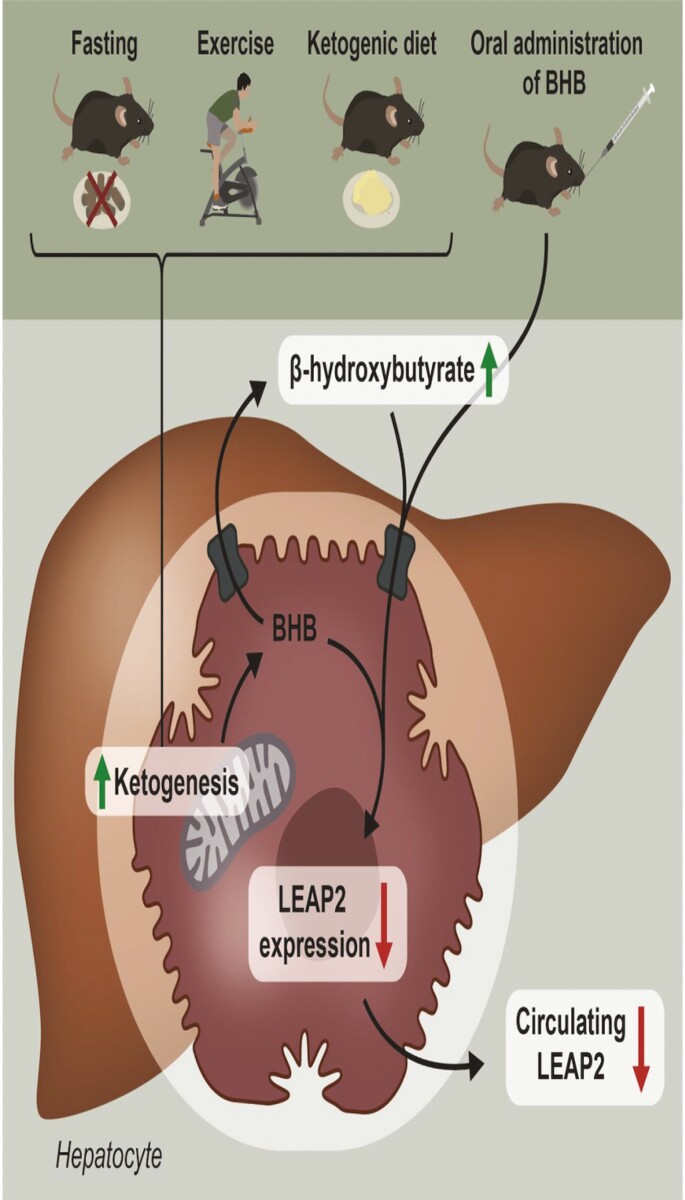

Direct Effect of BHB on LEAP2 Regulation

To examine if high plasma levels of BHB, independent of other exercise-, fasting-, or diet-induced metabolites, were able to regulate hepatic and intestinal Leap2 expression, we treated mice orally with BHB. Our study supported that BHB may serve as an important contributing factor not only in the downregulation of Leap2 expression in mouse liver but also in duodenum, and more importantly, this resulted in reduced circulating LEAP2 plasma levels. We did not expect a downregulation in duodenal Leap2 expression as we found no regulation in response to fasting and even an increase in Leap2 expression in response to ketogenic diet. Yet, a reduction in duodenal Leap2 expression may contribute to reduced systemic LEAP2 plasma levels together with reduced hepatic Leap2 expression. Notably, the plasma levels of BHB obtained after direct oral administration were similar to the plasma levels of endogenous BHB obtained after treatment with a ketogenic diet for 3 weeks (1.9 mM for acute in vivo BHB administration study; 1.1 mM for GroupChow-KD and 1.8 mM for GroupHFD-KD for our ketogenic diet study), where we found a similar decrease in hepatic Leap2 expression. Downregulation of Leap2 expression was also evident in isolated mouse hepatocytes stimulated with BHB. As hepatocytes synthesize the majority of the circulating BHB but are incapable of metabolizing ketone bodies (62), we suggest that BHB acts as a paracrine, autocrine, or intracrine modulator in hepatocytes to downregulate the expression of Leap2 which contributes to reduced systemic LEAP2 plasma levels (see graphical illustration Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Graphical illustration of BHB-induced LEAP2 regulation. Graphical illustration demonstrating that LEAP2 is reduced during energy-deprived conditions and that BHB directly downregulates LEAP2 expression and secretion in hepatocytes. Abbreviations: BHB; beta-hydroxybutyrate, LEAP2; Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2.

Ketone esters have recently been shown to reduce plasma ghrelin levels in humans (58, 60). In our study, we found reduced LEAP2 plasma levels in rodents after BHB administration, thus suggesting that ghrelin and LEAP2 are regulated in the same direction with increasing plasma BHB levels. This is unlike previous findings with inverse regulation of ghrelin and LEAP2 plasma levels (23). Whether LEAP2 plasma levels are affected after ingestion of ketone esters in humans remains, however, undescribed.

Is Plasma Glucose a Determining Factor in the Downregulation of LEAP2?

Plasma glucose levels have previously been described to regulate LEAP2 plasma levels (23). However, as we only found a tendency in blood glucose difference in our acute in vivo BHB administration study, we suggest that the direct effect of BHB treatment on LEAP2 liver and duodenal expression and plasma levels is independent of blood glucose levels. Additionally, no changes in blood glucose levels were observed in the human exercise study after endurance exercise compared with baseline levels (34). Furthermore, Mani et al (2019) only found a minor regulation in the plasma levels of LEAP2 in mice when inducing a strong upregulation of blood glucose levels by oral administration and in a type 1 diabetes mellitus mouse model compared with controls (23). However, as both low blood glucose levels and high BHB plasma levels reflect low energy status during energy depletion, they may collectively contribute to reduced LEAP2 levels in order to stimulate appetite and balance energy status. Yet, in our ketogenic diet study we found that the mice that were changed from HFD to chow had significantly lower blood glucose levels and no significant changes in blood levels of BHB and liver Leap2 expression as compared with the cohort that was kept on HFD. Moreover, Leap2 expression was similar in the HFD-fed mice and mice receiving ketogenic diet in the duodenum, thus supporting that low blood glucose may not drive the regulation of Leap2 expression in our studies. Therefore, we suggest that BHB may be a potent regulator of liver Leap2 expression in our chronic ketogenic diet study as well as expression and secretion in our acute in vivo BHB administration study.

Unknown Molecular Mechanisms Behind BHB-Induced Leap2 Regulation

As we found similar liver Leap2 regulations in our rodent studies in response to energy deprivation and high circulating BHB levels in both liver tissue and primary hepatocytes, we focused on the understanding of BHB-induced hepatic Leap2 regulation by use of isolated primary hepatocytes. We first examined whether the endogenous BHB receptor, HCAR2, was affected by BHB treatment and potentially could be involved in Leap2 regulation. Incubation with 10 mM BHB to isolated primary hepatocyte preparations reduced the expression of Hcar2. The underlying mechanisms behind this reduction remain unknown yet could be due to exposure to high levels of BHB. We also investigated the expression of Hcar2 in liver and intestinal tissue after oral administration of BHB and in our ketogenic diet study. Here, we found that Hcar2 expression levels were significantly higher in mice receiving BHB compared to controls in both liver and duodenum; however, a significant reduction was discovered in jejunum. Furthermore, we found increased Hcar2 expression levels in mouse liver from mice receiving ketogenic diet as compared with controls. Therefore, we tested whether the receptor, HCAR2, was involved in Leap2 regulation by stimulating mouse hepatocytes with a synthetic HCAR2 agonist, AR277. However, we found no regulation of Leap2 expression levels, suggesting that HCAR2 is not involved in BHB-induced Leap2 regulation in our hepatocyte setup, yet could still play a potential role in our in vivo models.

As BHB has been indicated to serve as a HDAC inhibitor (41), we measured the expression of Mct1 in our rodent studies. A regulation in Mct1 expression could implicate that BHB is transported into the cell and acts intracellularly to suppress Leap2 expression perhaps through HDAC inhibition within the nuclei of the hepatocytes. During ketogenic diet, liver Mct1 expression increased significantly compared with chow-fed and HFD-fed mice. We also found increased Mct1 expression in the duodenum in ketogenic diet–fed mice compared with lean chow-fed mice. In contrast, no changes were found in duodenal Mct1 expression in the DIO mice cohort and no changes were found in expression of Mct1 in mouse liver and intestines after oral administration of BHB, suggesting that the diet in the chow-cohort is more likely responsible for the regulation of Mct1 expression rather than exogenous BHB.

Nonetheless, we investigated whether BHB affected Mct1 expression in the hepatocytes, yet no changes were detected. As the regulation of Mct1 expression did not change in the liver or duodenum after oral administration of BHB and in mouse hepatocytes we suggest that Mct1 might not be involved in exogenous BHB-induced Leap2 downregulation but could be important during stimulation with endogenous BHB. However, we still investigated whether different synthetic HDAC inhibitors influenced Leap2 regulation, yet no regulation was discovered with either stimulation by TSA or TMP269 (HDAC class 1 or 2a, respectively).

Thus, the molecular mechanisms underlying BHB-induced Leap2 regulation in the liver remain unknown.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we suggest that LEAP2 is downregulated during different states of energy deprivation in both humans and rodents. We demonstrate that in both rodents and in humans, increased plasma levels of BHB (induced by oral administration of BHB, ketogenic diet, or endurance exercise) are associated with significantly reduced human and mouse plasma LEAP2 levels and rodent liver and duodenal Leap2 expressions. Furthermore, we show that isolated hepatocytes incubated with BHB decrease Leap2 expression, suggesting a direct effect of BHB on hepatocytes. Hence, we propose that high levels of BHB may act in a paracrine or autocrine manner in the liver to decrease liver Leap2 expression and further systemic levels of LEAP2. Since LEAP2 decreases the activation of the ghrelin receptor and reduces the orexigenic effect of ghrelin (22), the reduction in LEAP2 levels during high levels of BHB may be of physiological relevance during energy deprivation and fasting metabolism in order to reverse energy deficit and increase ghrelin-induced hunger signals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anette Bjerregaard and Chunyu Jin for experimental assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AR277

- BHB

beta-hydroxybutyrate

- BW

body weight

- DIO

diet-induced obese

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- HCAR2

hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2

- Hcar2

hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (gene)

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HFD

high-fat diet

- LEAP2

liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-2

- Leap2

liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-2

- Mct1

monocarboxylate transporter 1 (gene)

- TSA

tricostatin A

- Ywhaz

tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein zeta polypeptide (gene)

Contributor Information

Stephanie Holm, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Anna S Husted, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Louise J Skov, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Thomas H Morville, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Christoffer A Hagemann, Center for Clinical Metabolic Research, Copenhagen University Hospital—Herlev and Gentofte, 2900 Hellerup, Denmark; Gubra, 2970 Hørsholm, Denmark.

Tina Jorsal, Center for Clinical Metabolic Research, Copenhagen University Hospital—Herlev and Gentofte, 2900 Hellerup, Denmark.

Morten Dall, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Alexander Jakobsen, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Anders B Klein, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Jonas T Treebak, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Filip K Knop, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; Center for Clinical Metabolic Research, Copenhagen University Hospital—Herlev and Gentofte, 2900 Hellerup, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark; Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen, 2730 Herlev, Denmark.

Thue W Schwartz, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Christoffer Clemmensen, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Birgitte Holst, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark.

Author Contributions

B.H. and S.H. designed the study and were responsible for analyzing the results and the initial draft of the manuscript. A.S.H. and T.W.S. performed and contributed with samples from the ketogenic diet study and A.S.H. made the graphical abstract. L.J.S. performed, donated, and analyzed samples from ad libitum–fed vs fasted mice. A.J. supported mouse studies. T.H.M., A.B.K., and C.C. performed and donated samples from the human exercise study. C.A.H., T.J., and F.K.K. performed and donated human plasma samples from obese and lean individuals. M.D. and J.T.T. helped set up the ex vivo study. All authors have been involved in discussing, interpreting the results, and critically revising the manuscript, and all have given final approval of the version to be published.

Financial Support

S.H. is supported by a research grant from the Danish Diabetes Academy, which is funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, grant number NNF17SA0031406. A.S.H. and T.W.S. are supported by Challenge Grant NNF140C0013655, Challenge Grant NNF15OC0016798, and Immunometabolism Grant NNF15CC0018346 all from the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is supported by an unconditional grant (NNF18CC0034900) from the Novo Nordisk Foundation to University of Copenhagen. C.A.H. received research grant from the Innovation Fund Denmark (8053-00026B). J.T.T. is supported by Independent Research Fund Denmark (0134-00217B). C.C. is supported by research grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (Fellowship R238-2016-2859) and Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant number: NNF17OC0026114).

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories; see the Figshare repository for Supplementary Figures 1 to 3, which are listed in References;

Supplementary Figure 1 (37): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282373.v1

Supplementary Figure 2 (35): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282745.v1

Supplementary Figure 3 (40): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282880.v1

Disclosures

None declared.

References

- 1. Clemmensen C, Müller TD, Woods SC, Berthoud HR, Seeley RJ, Tschöp MH. Gut-brain cross-talk in metabolic control. Cell. 2017;168(5):758–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Small CJ, Bloom SR. Gut hormones and the control of appetite. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(6):259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrews ZB. Central mechanisms involved in the orexigenic actions of ghrelin. Peptides. 2011;32(11):2248– 2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trayhurn P, Bing C. Appetite and energy balance signals from adipocytes. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2006;361(1471). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kester JE. Liver. Encyclopedia of Toxicology: Third Edition. Ref Module Biomed Sci. 2014;96–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trefts E, Gannon M, Wasserman DH. The liver. Curr Biol. 2017;27(21):R1147–R1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee J, Choi J, Scafidi S, Wolfgang MJ. Hepatic fatty acid oxidation restrains systemic catabolism during starvation. Cell Rep. 2016;16(1):201– 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robinson AM, Williamson DH. Physiological roles of ketone bodies as substrates and signals in mammalian tissues. Physiol Rev. 1980;60(1). Printed in U.S.A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laffel L. Ketone bodies: a review of physiology, pathophysiology and application of monitoring to diabetes. Diabetes/Metabolism Res Rev. 1999;15(6):412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evans M, Cogan KE, Egan B. Metabolism of ketone bodies during exercise and training: physiological basis for exogenous supplementation. J Physiol. 2017;595(9):2857– 2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson RH, Walton JL, Krebs HA, Williamson DH. Post-exercise ketosis. Lancet. 1969;2(7635):1383-1385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Teruya T, Chaleckis R, Takada J, Yanagida M, Kondoh H. Diverse metabolic reactions activated during 58-hr fasting are revealed by non-targeted metabolomic analysis of human blood. Sci Rep. 2019;9(854). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Askew EW, Dohm GL, Huston RL. Fatty acid and ketone body metabolism in the rat: response to diet and exercise. J Nutr. 1975;105(11):1422–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koeslag JH, Noakes TD, Sloan AW. Post-exercise ketosis. J Physiol. 1980;301(1):79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Langhans W, Leitner C, Arnold M. Dietary fat sensing via fatty acid oxidation in enterocytes: possible role in the control of eating. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:554– 565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mansouri A, Pacheco-López G, Ramachandran D, et al. Enhancing hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation stimulates eating in food-deprived mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:131– 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jambor De Sousa UL, Arnold M, Langhans W, Geary N, Leonhardt M. Caprylic acid infusion acts in the liver to decrease food intake in rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;87(2):88–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scharrer E, Langhans W. Control of food intake by fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol. 1986;250(6):1003–R1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lutz TA, Diener M, Scharrer E. Intraportal mercaptoacetate infusion increases afferent activity in the common hepatic vagus branch of the rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1):R442–R445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge X, Yang H, Bednarek MA, et al. LEAP2 is an endogenous antagonist of the ghrelin receptor. Cell Metab. 2018;27(2):461–469.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mani BK, Puzziferri N, He Z, et al. LEAP2 changes with body mass and food intake in humans and mice. J Clin Investig. 2019;129(9):3909–3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. M’Kadmi C, Cabral A, Barrile F, et al. N-terminal liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 (LEAP2) region exhibits inverse agonist activity toward the ghrelin receptor. J Med Chem. 2019;62(2):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Islam MN, Mita Y, Maruyama K, et al. Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 antagonizes the effect of ghrelin in rodents. J Endocrinol. 2020;244(1):13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holst B, Cygankiewicz A, Jensen TH, Ankersen M, Schwartz TW. High constitutive signaling of the ghrelin receptor—identification of a potent inverse agonist. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(11):2201– 2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holst B, Schwartz TW. Constitutive ghrelin receptor activity as a signaling set-point in appetite regulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(3):113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lugilde J, Casado S, Beiroa D, et al. LEAP-2 counteracts ghrelin-induced food intake in a nutrientgrowth hormone and age independent manner. Cells. 2022;11(3):324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shankar K, Metzger NP, Singh O, et al. LEAP2 deletion in mice enhances ghrelin’s actions as an orexigen and growth hormone secretagogue. Mol Metab. 2021;53. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gupta D, Dowsett GKC, Mani BK, et al. High coexpression of the ghrelin and LEAP2 receptor GHSR with pancreatic polypeptide in mouse and human islets. Endocrinology. 2021;162(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrews ZB. The next big LEAP2 understanding ghrelin function. J Clin Investig. 2019;129(9):3542–3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hagemann CA, Zhang C, Hansen HH, et al. Identification and metabolic profiling of a novel human gut-derived LEAP2 fragment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;106(2):e966–e981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jorsal T, Christensen MM, Mortensen B, et al. Gut Mucosal gene expression and metabolic changes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity. 2020;28(11):2163– 2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morville T, Sahl RE, Trammell SA, et al. Divergent effects of resistance and endurance exercise on plasma bile acids, FGF19, and FGF21 in humans. JCI Insight. 2018;3(15):e122737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holm S, Husted A, Skov L, et al. Supplementary Figure 2. Figshare. Deposited March 3, 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.19282745 [DOI]

- 36. Dall M, Trammell SAJ, Asping M, et al. Mitochondrial function in liver cells is resistant to perturbations in NAD+ salvage capacity. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(36):13304–13326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holm S, Husted AS, Skov LJ, et al. Supplementary Figure 1. Figshare. Deposited March 3, 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.19282373 [DOI]

- 38. Kennedy AR, Pissios P, Otu H, et al. A high-fat, ketogenic diet induces a unique metabolic state in mice. Am J Physiol. 2007;292(6):E1724–E1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martini T, Ripperger JA, Chavan R, et al. The hepatic monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) contributes to the regulation of food anticipation in mice. Front Physiol. 2021;12:665476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holm S, Husted A, Skov L, et al. Supplementary Figure 3. Figshare. Deposited March 3, 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.19282880.v2 [DOI]

- 41. Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2012;339(6116):211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ma X, Xue X, Zhang J, et al. Liver Expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 is associated with steatosis in mice and humans. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2021;129(08): 601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aslanipour B, Alan M, Demir I. Decreased levels of liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide-2 and ghrelin are related to insulin resistance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36(3):222– 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barja-Fernández S, Lugilde J, Castelao C, et al. Circulating LEAP-2 is associated with puberty in girls. Int J Obes. 2021;45(3):502– 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fittipaldi AS, Hernández J, Castrogiovanni D, et al. Plasma levels of ghrelin, des-acyl ghrelin and LEAP2 in children with obesity: Correlation with age and insulin resistance. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182(2):165– 175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schubert MM, Sabapathy S, Leveritt M, Desbrow B. Acute exercise and hormones related to appetite regulation: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014;44(3):387– 403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Broom DR, Stensel DJ, Bishop NC, Burns SF, Miyashita M. Exercise-induced suppression of acylated ghrelin in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(6):2165– 2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Poon ETC, Sun FH, Chung APW, Wong SHS. Post-exercise appetite and ad libitum energy intake in response to high-intensity interval training versus moderate-or vigorous-intensity continuous training among physically inactive middle-aged adults. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mani BK, Castorena CM, Osborne-Lawrence S, et al. Ghrelin mediates exercise endurance and the feeding response post-exercise. Mol Metab. 2018;9(January):114–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tso P, Balint JA. Formation and transport of chylomicrons by enterocytes to the lymphatics. Am J Physiol. 1986;250(6 Pt 1):G715–G726. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51. Ramachandran D, Clara R, Fedele S, et al. Enhancing enterocyte fatty acid oxidation in mice affects glycemic control depending on dietary fat. Sci Rep. 2018;8(10818). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clara R, Schumacher M, Ramachandran D, et al. Metabolic adaptation of the small intestine to short- and medium-term high-fat diet exposure. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(1):167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gibson AA, Seimon RV, Lee CMY, et al. Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(1):64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deemer SE, Plaisance EP, Martins C. Impact of ketosis on appetite regulation—a review. Nutr Res. 2020;77:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Langhans W, Pantel K, Scharrer E. Ketone kinetics and D-(-)-3-hydroxybutyrate-induced inhibition of feeding in rats. Physiol Behav. 1985;34(4):579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Langhans W, Wiesenreiter F, Scharrer E. Different effects of subcutaneous D,L-3-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate injections on food intake in rats. Physiol Behav. 1983;31(4):483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Paoli A, Bosco G, Camporesi EM, Mangar D. Ketosis, ketogenic diet and food intake control: a complex relationship. Front Psychol. 2015;6(27). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stubbs BJ, Cox PJ, Evans RD, Cyranka M, Clarke K, de Wet H. A ketone ester drink lowers human ghrelin and appetite. Obesity. 2018;26(2):269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hepler C, Foy CE, Higgins MR, Renquist BJ. The hypophagic response to heat stress is not mediated by GPR109A or BHB. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310(10):R992–R998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vestergaard ET, Zubanovic NB, Rittig N, et al. Acute ketosis inhibits appetite and decreases plasma concentrations of acyl ghrelin in healthy young men. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(8):1834–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Inoue D, Tsujimoto G, Kimura I. Regulation of energy homeostasis by GPR41. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5(81). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Orii KE, Fukao T, Song XQ, Mitchell GA, Kondo N. Liver-specific silencing of the human gene encoding succinyl-CoA: 3-Ketoacid CoA transferase. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;21(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories; see the Figshare repository for Supplementary Figures 1 to 3, which are listed in References;

Supplementary Figure 1 (37): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282373.v1

Supplementary Figure 2 (35): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282745.v1

Supplementary Figure 3 (40): https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19282880.v1