Abstract

Background:

Beginning in 2012 direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were approved for treatment and prevention of VTE. Prior investigations have demonstrated slow rates of adoption of novel therapeutics for black patients. We assessed the association of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic factors with DOAC use among commercially-insured VTE patients.

Methods and Results:

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of adult patients with an incident diagnosis of VTE between January 2010 and December 2016 using OptumInsight’s Clinformatics Data Mart. We identified the first filled oral anticoagulant prescription within 30 days of discharge of an inpatient admission. We performed a multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, region, zip-code linked household income, and clinical covariates to identify factors associated with the use of DOACs. Race and ethnicity were determined in this database through a combination of public records, self-report, and proprietary ethnicity code tables.

There were 14,140 patients included in the analysis. Treatment with DOACs increased from less than 0.1% in 2010 to 65.6% in 2016. In multivariable analyses black patients were less likely to receive a DOAC compared to white patients (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77 – 0.97, p=0.02). There were no differences in DOAC utilization among Asian (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.75 – 1.49, p=0.74) or Hispanic patients (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.88 – 1.22, p=0.66) compared to whites. Patients with a household income over $100,000 per year were more likely to receive DOAC therapy compared to patients with a household income of less than $40,000 per year (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.33 – 1.69, p<0.0001).

Conclusions:

Although DOAC adoption has increased steadily since 2012, among a commercially-insured population, black race and low household income were associated with lower use of DOACs for incident VTE despite controlling for other clinical and socioeconomic factors. These findings suggest the possibility of both racial and socioeconomic inequity in access to this novel pharmacotherapy.

Introduction

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) have been used as an anticoagulant pharmacotherapy for over 60 years in the United States and until recently had been the standard therapy for venous thromboembolism (VTE). However, VKA require frequent and perpetual monitoring of the anticoagulant effect to ensure appropriate dosing, and their narrow therapeutic range despite close monitoring places patients at risk of both insufficient and excess anticoagulation, with resultant serious adverse effects [1].

In contrast, direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) have a more predictable and stable anticoagulant effect, and thus they have become a more attractive therapeutic option. DOACs were initially used for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), with subsequent expansion of clinical indications to include the treatment and prevention of VTE after numerous studies demonstrated non-inferiority or superiority of DOACs compared to VKA for VTE patients [2,3,4]. Beginning in 2012, these medications were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the treatment and prevention of VTE, and they are now the treatment of choice for VTE per consensus guideline recommendations [5]. Several DOACs have been introduced in the U.S. market, including rivaroxaban in November 2012, dabigatran in April 2014, apixaban in August 2014, and edoxaban in January 2015.

To date, few studies have assessed equity in the adoption of DOACs among patients with VTE in the United States. Prior studies of technology adoption have revealed substantial disparities in access to new treatments among disadvantaged patient groups [6,7]. In the present study, we sought to evaluate recent time trends in prescription of direct oral anticoagulants among a large, commercially-insured population of VTE patients, and we assessed whether race and income were predictors of the likelihood of receiving DOACs versus VKA.

Methods

Study Data

Data for this study were obtained from the OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart database, a large private payer administrative claims database. The database consists of inpatient, outpatient, laboratory, and pharmacy claims for a geographically diverse cohort of 13 million patients annually. Patients are predominantly located in the Midwest, South, and Southeast. Demographic and socioeconomic data, including median household income, are available through ZIP-code-linked enrollment data from the US Census Bureau. Race and ethnicity were determined in this database through a combination of public records, self-report, and proprietary ethnicity code tables. This study used deidentified data and was considered exempt from review by the institutional review board. The methods used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Cohort

We identified adult (i.e., age>18 years) patients in the database with an index diagnosis of VTE between January 1, 2010 and December 1, 2016 who filled a prescription for an oral anticoagulant (VKA, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban or apixaban) within 30 days of hospital discharge. Patients were identified as having a diagnosis of VTE following a previously-validated scheme for identifying patients with VTE using administrative claims data [8,9]. Specifically, patients were selected if they had a diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 451.1, 451.2, 451.8, 451.9, 453.2, 453.8, and 453.9; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes: I80.2, I80.3, I80.1, I82.8, I80.9, I82.9, I80.8, O22.3, O22.9, O87.1) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (ICD-9-CM: 415.0 and 415.1; ICD-10-CM: I26.9, I26.0) in any diagnostic field. To increase the specificity of the VTE patient-identification algorithm, we also required that all patients have a claim with a procedural code indicating they had received imaging necessary for the diagnosis of VTE, such as computed tomography angiography (Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 71275), ventilation-perfusion scan (CPT code 78582) or lower limb compression ultrasound (CPT codes code 93970, 93971, 93975, 93976).

Patients were excluded if they did not have continuous insurance enrollment for at least 1 year prior to admission for VTE, so that a complete picture of comorbidities, recent medical events, and prior anticoagulation use could be obtained for all patients. In addition, patients were required to have at least 30 days of insurance enrollment following hospital discharge for VTE, and they were required to have filled at least one pharmacy claim during this time period, to ensure that their pharmaceutical use was being “captured” in our data. Since our study was focused on patients who were being initiated on anticoagulation therapy, we excluded patients who had been treated with VKA, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban or apixaban in the preceding year, and we excluded patients with atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and prosthetic heart valves, because these patients may have had a concomitant clinical indication for anticoagulation. We excluded patients with any VTE diagnoses within the preceding year to focus on incident diagnoses. Patients with concurrent major bleeding during the admission, as well as a diagnosis of cancer or end-stage renal disease were likewise excluded, as their underlying condition may have influenced the choice of anticoagulant.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics for patient characteristics are presented as means with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous data and are presented as total number and percentages for categorical data. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test.

To assess the relationship of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors to the use of DOACs, we estimated multitvariable logistic regression models with the use of DOAC vs. VKA as the dependent variable, and with independent variables including age, sex, region of residence, zip-code linked household income, history of prior stroke, presence of an inferior vena cava filter, the Elixhauser comorbidity index [10], and race/ethnicity. Household income categories were chosen based on available categories defined in the database. Candidate variables included in the model were selected a priori based on pathophysiological plausibility and all were used in the multivariable model. Estimated adjusted odds ratios (OR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). We then estimated secondary models including interaction effects between race/ethnicity and household income in order to assess for the presence of effect modification of household income on race/ethnicity by repeating the multivariable logistic regression analysis with an interaction parameter between household income and race/ethnicity. The effect of missing data was addressed via multiple imputation analysis [11]

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical testing was 2-tailed, with p-values<0.05 designated statistically significant.

Results

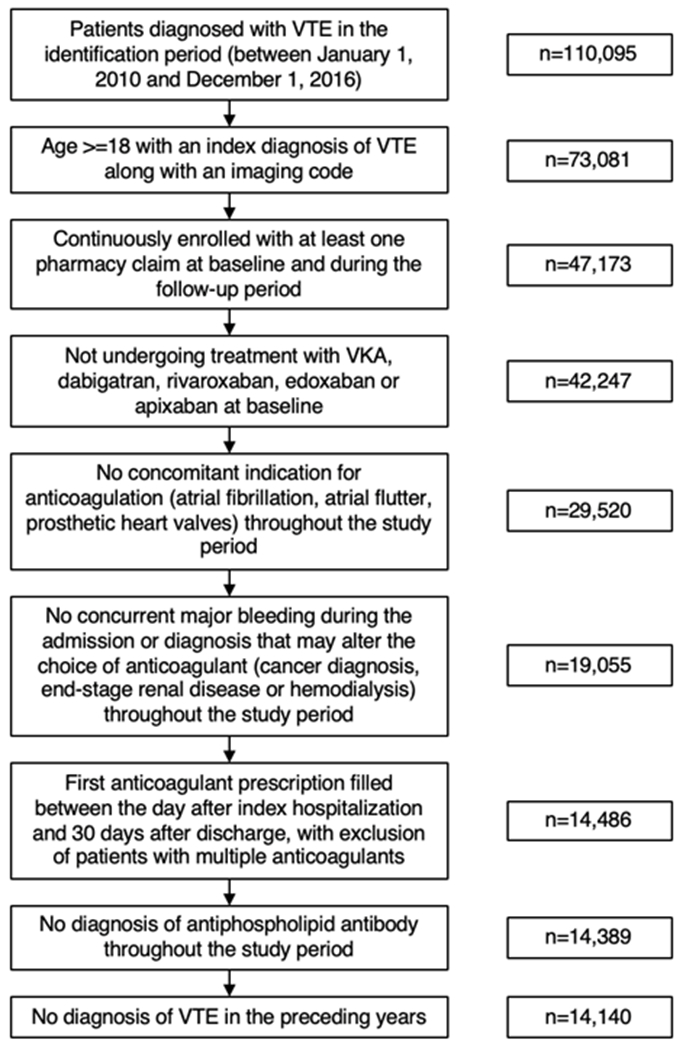

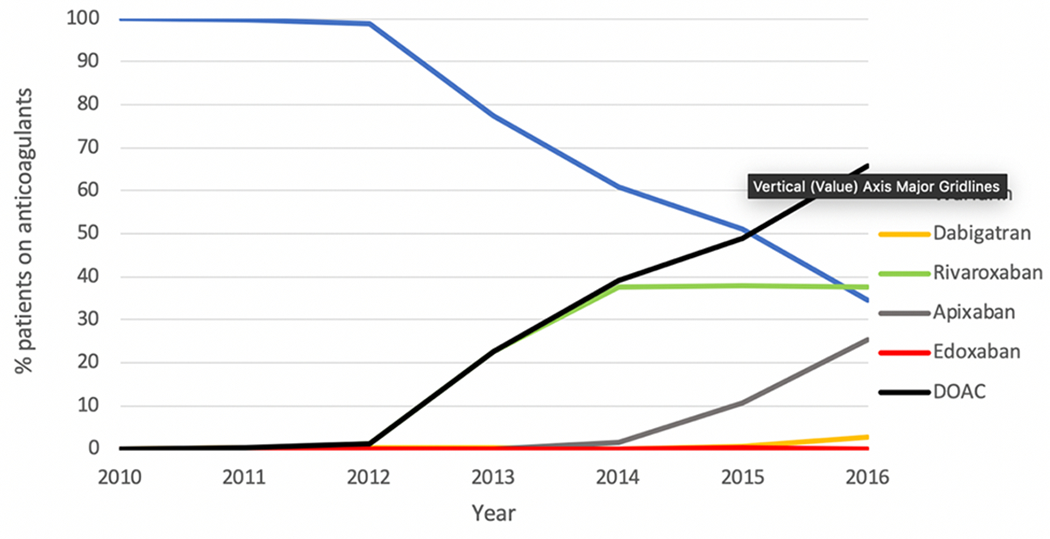

A total of 14,140 patients were included in the analysis after application of exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Between 2010 and 2016, the percentage of patients treated with DOACs increased from less than 0.1% in 2010 to 65.6% in 2016 (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Flowchart of study population with applied exclusion criteria.

Figure 2:

Trends of oral anticoagulant prescription among patients with venous thromboembolism.

Baseline demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics for all patients with VTE are presented in Table 1. Overall, 10,495 (74.2%) of the patients in our cohort were treated with VKA and 3645 (25.8%) were treated with DOAC. The mean age of the cohort was 58.7 years, and 78.8% of included patients were white and 14.1% of patients were black. The South and Midwest were the most highly represented areas of the country. There was a wide variety in household income, with 34.2% of the overall cohort having an annual income over $100,000, and 26.0% of patients earning less than $40,000 annually.

Table 1:

Baseline demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics for all patients with VTE

| Characteristic | VKA (n = 10495) | DOAC (n = 3645) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 58.78 (15.95) | 58.53 (15.56) | 0.42 |

| Male Sex (n) | 4892 (46.6) | 1759 (48.3) | 0.09 |

| Race/Ethnicity (n) | 0.01 | ||

| White | 8219 (78.3) | 2929 (80.4) | |

| Black | 1540 (14.7) | 454 (12.5) | |

| Hispanic | 616 (5.9) | 217 (6.0) | |

| Asian | 120 (1.1) | 45 (1.2) | |

| Region (n) | <0.001 | ||

| Midwest | 3066 (29.2) | 960 (26.3) | |

| Northeast | 932 (8.9) | 392 (10.8) | |

| South | 4441 (42.3) | 1713 (47.0) | |

| West | 2056 (19.6) | 580 (15.9) | |

| Household income (n) | <0.001 | ||

| $100K+ | 3402 (32.4) | 1434 (39.3) | |

| $75K-$99K | 1494 (14.2) | 513 (14.1) | |

| $60K-$74K | 1120 (10.7) | 359 (9.8) | |

| $50K-$59K | 788 (7.5) | 255 (7.0) | |

| $40K-$49K | 808 (7.7) | 291 (8.0) | |

| <$40K | 2883 (27.5) | 793 (21.8) | |

| Comorbidities (n) | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 987 (9.4) | 339 (9.3) | 0.88 |

| Hypertension | 6340 (60.4) | 2181 (59.8) | 0.56 |

| Diabetes | 2319 (22.1) | 792 (21.7) | 0.66 |

| Vascular disease | 944 (9.0) | 313 (8.6) | 0.48 |

| Renal disease | 929 (8.9) | 309 (8.5) | 0.51 |

| Liver disease | 500 (4.8) | 208 (5.7) | 0.03 |

| Ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack | 947 (9.0) | 206 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Presence of IVC filter | 153 (1.5) | 44 (1.2) | 0.30 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Count (n) | 0.12 | ||

| >=4 | 6813 (64.9) | 2329 (63.9) | |

| 2-3 | 1776 (16.9) | 671 (18.4) | |

| 0-1 | 1906 (18.2) | 645 (17.7) |

In unadjusted analyses, patients treated with DOACs had higher household incomes, with 39.3% of patients prescribed DOAC having a household income of over $100,000, as compared to 32.4% of patients prescribed coumadin (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease or renal disease among patients prescribed VKA vs. DOACs. However, there were fewer patients with prior ischemic stroke prescribed DOACs (5.7% versus 9.0%, p<0.001). There was no significant difference in the Elixhauser comorbidity count for patients prescribed DOACs as compared to VKA (p=0.12). There was a different race/ethnicity composition of patients prescribed VKA as compared to DOAC, with 14.7% of black patients prescribed VKA as compared to 12.5% who were prescribed DOACs (p=0.01).

In multivariable analyses (Table 2), black patients were less likely to receive a DOAC compared to white patients (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77 – 0.97, p=0.02). There were no differences in utilization among Asian patients (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.75 – 1.49, p=0.74) or Hispanic patients (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.88 – 1.22, p=0.66) as compared to white patients. Patients with a household income over $100,000 per year were more likely to receive DOAC therapy as compared to patients with a household income of less than $40,000 per year (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.33 – 1.69, p<0.0001). Interaction testing between an income less than $40,000 per year and black race was not significant (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.79 – 1.33, p=0.84).

Table 2:

Multivariable logistic regression on factors associated with prescription of DOACs versus VKA

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (18-54 years as reference) | ||

| 55-64 | 1.11 (1.00 - 1.22) | 0.05 |

| 65-74 | 1.09 (0.98 - 1.22) | 0.11 |

| Over 75 | 1.11 (0.98 - 1.26) | 0.09 |

| Male | 1.00 (0.92 - 1.08) | 0.98 |

| Race/Ethnicity (white as reference) | ||

| Asian | 1.06 (0.75 - 1.49) | 0.74 |

| Black | 0.86 (0.77 - 0.97) | 0.02 |

| Hispanic | 1.04 (0.88 - 1.22) | 0.66 |

| Region of residence (Northeast as reference) | ||

| Midwest | 0.74 (0.64 - 0.85) | <.0001 |

| South | 0.95 (0.83 - 1.08) | 0.41 |

| West | 0.66 (0.56 - 0.76) | <.0001 |

| Household income (<$40K as reference) | ||

| $100K+ | 1.50 (1.33 - 1.69) | <.0001 |

| $75K-$99K | 1.23 (1.07 - 1.42) | <0.01 |

| $60K-$74K | 1.16 (1.00 - 1.34) | 0.05 |

| $50K-$59K | 1.15 (0.97 - 1.36) | 0.11 |

| $40K-$49K | 1.30 (1.10 - 1.54) | <0.01 |

| Ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack | 0.61 (0.52 - 0.72) | <.0001 |

| Presence of IVC filter | 0.80 (0.57 - 1.13) | 0.20 |

| Elixhauser Score (0-1 as reference) | ||

| 2-3 | 1.13 (0.99 - 1.28) | 0.07 |

| >=4 | 1.08 (0.97 - 1.21) | 0.15 |

Discussion

Since DOACs were first approved for the treatment and prevention of VTE in late 2012, there has been a steady and substantial increase in their use. However, even among a commercially-insured population with prescription drug coverage, black race and lower zip-code linked household income were each independently associated with lower prescription of DOACs for incident VTE despite controlling for other socioeconomic factors. To date, this is the first study to investigate the adoption of DOACs for VTE and factors associated with persistent VKA use in a contemporary population in the US.

DOACs were introduced for the prevention of stroke in patients in the US with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in 2010, two years before the approval for VTE. Previous studies among patients with atrial fibrillation have shown rapid rates of adoption, with one study finding the use of DOACs in almost 80% of patients in 2017 [12]. Further, the ease of clinical use of DOACs compared to VKAs has resulted in an overall increase in the percentage of patients with atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulation [13]. Among patients with VTE, a study of the Danish nationwide registry found that in 2016, 88% of patients were treated with DOACs, demonstrating a more rapid rate of adoption of DOACs [14], which have concurrently been shown to be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin [15].

Although we found that the adoption of DOACs increased monotonically throughout the study period, even as late as 2016 when DOACs were in widespread clinical use, 34% of VTE patients that were eligible for DOAC therapy were still prescribed VKA in this commercially insured population. There are several possible explanations for our findings. First, there were limited options for anticoagulation reversal for DOACs when they were first introduced, unlike VKA, raising concern among treating physicians that life-threatening bleeding could be irreversible if a DOAC was used. Second, treatment with VKA necessitates frequent monitoring, allowing treating physicians to monitor medication compliance and therapeutic anticoagulation. Third, treating physicians may have been wary about the out-of-pocket drug costs for their patients, and preferred generic VKA. Finally, novel therapeutics are often burdened by “clinical inertia”, where healthcare providers may be unfamiliar with updated guidelines or unwilling to change practices [16]. Given the relatively slow rate of adoption, we sought to identify factors that were associated with the use of DOACs or warfarin and assessed whether there were racial and ethnic disparities in use.

In our study, we found that black patients with an incident diagnosis of VTE were significantly less likely to receive DOACs as compared to white patients, controlling for other socioeconomic factors. This finding was not present among Asian or Hispanic patients, although those populations were smaller and thus our power to detect a meaningful difference in prescription rates was lower. Further, patients with lower household incomes were less likely to receive DOACs. These findings suggest the possibility of a racial inequity in access to this new pharmacotherapy, even among a population of patients with prescription drug insurance, who should face less financial pressure to choose the lowest cost therapy. Notably, there was no evidence of effect modification, because the interaction between black race and household income less than $40,000 annually was not statistically significant, which further emphasizes a major role of race in prescribing patterns.

These findings of racial/ethnic disparities are consistent with prior studies of DOAC use in atrial fibrillation. In a study of a prospective US-based registry of outpatients with atrial fibrillation, black patients were significantly less likely to receive DOACs than white patients for atrial fibrillation, even after controlling for clinical and socioeconomic factors [7]. In that study, there were no differences in the likelihood of prescription of DOACs between white and Hispanic patients, a finding remarkably similar to the results of our study. These findings are particularly poignant given prior data demonstrating decreased time with therapeutic INR among black patients, possibly due to underappreciation of different dosing requirements among different racial groups [17,18].

Racial inequities in US medical care are pervasive and well documented [19] and there are several proposed mechanisms for racial/ethnic inequities in the treatment of black patients with cardiovascular disease in the United States [20]. Reduced access to specialty providers, including cardiologists, has been demonstrated among black patients [21,22]. Other studies have cited differences in health insurance coverage rates to explain disparate care by race, yet we nevertheless observed racial and socioeconomic disparities in a population that was 100% insured [23]. Finally, due to the costs of DOACs, patients with lower socioeconomic status may have differential abilities to afford this medication. We did find that patients with household incomes of less than $40,000 were less likely to be treated with a DOAC than patients with a household income of over $100,000. Prior studies in this population have indicated that out-of-pocket costs influence patient behaviors and compliance with medications, as the higher costs of DOACs may be prohibitive for some patients [24].

The findings of our study, as well as previous studies raise the concern for implicit bias, or attitudes and stereotypes that affect decisions in an unconscious manner in the treatment of black patients in the United States. Studies suggest many health care providers demonstrate signs of implicit bias, with positive attitudes towards white patients and negative attitudes towards patients of color [25]. The presence of implicit bias among providers may contribute to the reduced likelihood of DOAC therapy in black patients with VTE, as they may preferentially prescribe novel, more expensive therapeutics to white patients due to perceptions of higher socioeconomic status and ability to afford the medication [26]. In addition, it has been previously demonstrated that provider interactions with patients of color are less patient-centered, with fewer requests for patient input about treatment decisions in general [27]. Prior studies have demonstrated significant heterogeneity in patient therapy preferences due to perceived differences in DOACs and VKA, which necessitates direct clarification of an individual patient’s values and preferences [28,29]. Black patients may not be given the same voice to express their preference for DOAC, especially if there are preconceived notions about preferences and ability to afford the novel therapy.

Our study has several limitations. First, the use of an administrative database provides limited granularity into the details of the circumstances surrounding individual patient care decisions, making it possible that our results were confounded by unobserved factors related to race that “drove” the choice of anticoagulant. To address the potential for confounding, we excluded any groups of patients that may have had underlying characteristics that altered the choice of anticoagulant therapy. However, because this study used administrative data, we were unable to observe important non-clinical variables such as patient preferences, clinician preferences/experience, prescribing provider specialty, insurance details, and/or clinician marketing exposure, which have been shown to influence the decision to use VKA versus DOAC [30,31]. This choice reflects subtle and nuanced clinical decision making that may not be completely represented in a claims database. Patterns of trust in the health care system differ by race, with black patients being less likely to trust healthcare providers than white patients [32]. We must acknowledge that black patients may be less trusting of novel therapies such as DOACs, and this behavior may contribute to our findings. Second, we are also unable to study patients who were prescribed oral anticoagulants on discharge but did not fill them, as they would appear indistinguishable from patients who were never filled an oral anticoagulant prescription. Third, we were unable to study differences in outcomes between the different treatment groups because of the lack of long term follow up data present within the OptumInsight database. Finally, we used the race and ethnicity category as defined within the OptumInsight database. Though the race/ethnicity ascertainment methods used in this database have not been validated, self-reporting and public records, as used in this database, are often used in population-based studies of race and ethnicity. Further, the categories present do not fully capture the many races and ethnicities present in the United States. Disparities within broad groups may not be fully represented. More importantly, the operationalization of race in a broader socioeconomic and sociopolitical context, the effects of structural racism, patients’ experience with the healthcare system and levels of perceived racism are not fully captured. However, despite the aforementioned limitations, and given the demonstrated benefit of DOACs as compared to VKA in the treatment of VTE, the finding of reduced use of use of DOAC among these patients highlights the importance of efforts to improve equitable medication uptake and utilization among all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

Conclusion

We found a consistent and substantial increase in the use of DOACs among patients with VTE in the United States. However, in this fully-insured patient population, black race and lower zip-code linked household income were each independently associated with lower use of DOACs for incident VTE. These findings suggest the presence of both racial and socioeconomic inequity in access to this novel pharmacotherapy.

Supplementary Material

What is Known:

Direct oral anticoagulants are an effective alternative to vitamin K antagonists in the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism

What this Study Adds:

The use of direct oral anticoagulants has increased in this country

Among a commercially-insured population, black race and low household income are associated with lower use of direct oral anticoagulants

Racial and ethnic inequities are pervasive within cardiovascular therapeutics

Footnotes

Disclosures: No relevant disclosures

References

- 1.Pokorney SD, Simon DN, Thomas L, Fonarow GC, Kowey PR, Chang P, et al. Patients’ time in therapeutic range on warfarin among US patients with atrial fibrillation: Results from ORBIT-AF registry. 2015;170:141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Investigators EINSTEIN-PE, Büller HR Prins MH, Prins MH Lesin AW, Decousus H Jacobson BF, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, Mismetti P, Schellong S, Eriksson H, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, Curto M, Gallus AS, Johnson M, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149:315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholzberg M, Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Yao Z, Mamdani MM, Laupacis A. The Influence of Socioeconomic Status on Selection of Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essien UR, Holmes DN, Jackson LR 2nd, Fonarow GC, Mahaffey KW, Reiffel JA, et al. Association of Race/Ethnicity With Oral Anticoagulant Use in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Findings From the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation II. JAMA Cardiol. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3945. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamariz L, Harkins T, Nair V. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying venous thromboembolism using administrative and claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21 Suppl 1:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alotaibi GS, Wu C, Senthilselvan A, McMurtry MS. The validity of ICD codes coupled with imaging procedure codes for identifying acute venous thromboembolism using administrative data. Vasc Med. 2015;20:364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y. Missing data analysis using multiple imputation: getting to the heart of the matter. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu J, Alexander GC, Nazarian S, Segal JB, Wu AW. Trends and Variation in Oral Anticoagulant Choice in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, 2010-2017. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:907–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD. National Trends in Ambulatory Oral Anticoagulant Use. Am J Med. 2015;128:1300–5.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sindet-Pedersen C, Pallisgaard JL, Staerk L, Berger JS, Lamberts M, Torp-Pedersen C. Temporal trends in initiation of VKA, rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran for the treatment of venous thromboembolism - A Danish nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Jong LA, Dvortsin E, Janssen KJ, Postma MJ. Cost-effectiveness Analysis for Apixaban in the Acute Treatment and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2017;39:288–302.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El-Kebbi M, Gallina DL, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen AY, Jao JF, Brar SS, Jorgensen MB, Wang X, Chen W. Racial/Ethnic differences in ischemic stroke rates and the efficacy of warfarin among patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2008;39:2736–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limdi NA, Veenstra DL. Warfarin pharmacogenetics. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:1084–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capers Q, Sharalaya Z. Racial disparities in cardiovascular care: A review of culprits and potential solutions. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2014;1;171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook NL, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Differences in specialist consultations for cardiovascular disease by race, ethnicity, gender, insurance status, and site of primary care. Circulation. 2009;119:2463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breathett K, Liu WG, Allen LA, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Jones J, et al. African Americans are less likely to receive care by a cardiologist during an intensive care unit admission for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirby JB, Kaneda T. Unhealthy and uninsured: exploring racial differences in health and health insurance coverage using a life table approach. Demography. 2010;47:1035–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dayoub EJ, Seigerman M, Tuteja S, Kobayashi T, Kolansky DM, Giri J, et al. Trends in platelet adenosine diphosphate P2Y12 receptor inhibitor use and adherence among antiplatelet-naive patients after percutaneous coronary intervention, 2008-2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. Jul 1;178(7):943–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient–physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loewen PS, Ji AT, Kapanen A, McClean A. Patient values and preferences for antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. A Narrative Systematic Review. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1007–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade JG, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, Purdham D, Ciaccia A, Connors S. Values and Preferences of Physicians and Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Who Receive Oral Anticoagulation Therapy for Stroke Prevention. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:747–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marzona I, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Franzosi MG, Moia M. Criteria for the choice of anticoagulant therapy for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation early after the marketing of direct oral anticoagulants in Italy. Eur J Intern Med. 2017. Jun;41:e12–e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajorek B, Saxton B, Anderson E, Chow CK. Patients’ preferences for new versus old anticoagulants: a mixed-method vignette-based study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17:429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NA. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003; 118: 358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.