Abstract

Background

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) mutations have been reported in many cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The frequency of these mutations varies among tumor locations and might be relevant to treatment outcomes among HNSCC. In this study, we examined the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in the different subsites of HNSCC.

Methods

Ninety-six fresh biopsy specimens were investigated for mutations in PIK3CA exons 4, 9, and 20 using allele-specific real-time polymerase chain reaction. Patient characteristics and survival were analyzed and compared between specimens with or without PIK3CA mutations.

Results

The study included primary tumors originating from the oral cavity (n = 63), hypopharynx (n = 23), and oropharynx (n = 10). We identified mutations in 10.4% of patients (10 of 96 specimens). The overall mutational frequency was 17.4% (4/23) and 9.5% (6/63) in the hypopharynx and oral cavity, respectively. No patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma had mutations. Among the 10 mutant specimens, five were missense mutations (exon 9 [E545K] in two samples and exon 20 [H1047R] in three samples) and five were silent mutations in exon 20 (T1025T). Mutations were not found in exon 4. Among 84 patients with available clinical data, we found no significant differences in clinical characteristics and survival based on the presence or absence of PIK-3CA mutations.

Conclusions

The results indicate that PIK3CA mutations are involved in HNSCC carcinogenesis, and the hypopharynx should be considered a primary site of interest for future studies, particularly in Southeast Asian populations.

Keywords: PIK3CA mutations, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Oral cavity carcinoma, Hypopharyngeal carcinoma, Oropharyngeal carcinoma

Head and neck cancer includes all tumors that arise from various anatomical subsites, including the oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, paranasal sinuses, and salivary glands. Although histologic subtypes are diverse, malignancies of the epithelial lining, namely squamous cell carcinoma, are the most common [1].

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide, with approximately 890,000 new cases diagnosed and 450,000 deaths reported in 2008. Among all HNSCC, the oral cavity is the most common subsite of a primary tumor [2]. The burden of HNSCC varies across regions of the world. In Thailand, HNSCC is one of the most common cancers, with approximately 10,000 new cases diagnosed annually. The age-standardized incidence rates of HNSCC in males and females are 15.7 and 10.7, respectively [3]. The dominant tumor locations of HNSCC in males are the oral cavity, nasopharynx, and larynx; and the most common location in females is the oral cavity [3].

At the time of diagnosis, most patients with HNSCC have locally advanced, unresectable tumors. Despite advanced multidisciplinary treatments, including surgery with either or both radiotherapy and chemotherapy, only modest improvements in outcomes have been achieved over the past 20 years. HNSCC molecular profiling and biomarker studies have provided information regarding rapid diagnosis, prognosis, and surveillance for recurrence and metastasis. However, biomarkers that serve as potential targets of novel therapies to improve survival outcomes are important. Among the signaling pathways associated with tumor proliferation and survival, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) pathway is the most frequently altered oncogenic pathway in HNSCC [4,5].

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gene (PI3K) encodes PI3K enzymes (PI3Ks), which ultimately trigger various downstream signaling pathways that result in cell survival, apoptosis, transformation, metastasis, and cell migration. PI3Ks are classified into three major subclasses (class I, II, and III) that are determined based on PI3K structure and substrate specificity. Phosphatidylinositol- 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) is a 34-kb gene located on chromosome 3q26.3 that consists of 20 exons coding for 1,068 amino acids, yielding a protein with a molecular weight of 124 kDa (p110α catalytic subunit protein, class I) [6]. Several studies previously reported alterations in PIK3CA in many cancers. The presence of PIK3CA mutations is associated with prognosis and might predict response to PI3K inhibitors [6,7]. In HNSCC, the frequency of PIK3CA mutations varies among primary tumor locations [6,8–15]; hence, the frequency of these mutations from different tumor subsites might be relevant to determine treatments and outcomes among HNSCCs. Furthermore, the mutation rate in PIK3CA might be diverse among ethnicities [15,16]; the mutation rate is unknown in Southeast Asian populations, including the Thai population. Therefore, in the present study, we evaluated the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and hypopharynx in southern Thailand. Furthermore, the clinical characteristics and survival between patients with or without PIK3CA mutations were analyzed and compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and specimens

During 2002–2003, 96 fresh tissues (63 from the oral cavity, 10 from the oropharynx, and 23 from the hypopharynx) were obtained from patients registered at the head and neck clinic of Songklanagarind Hospital. The tissue samples were obtained from a biopsy or sampling of surgical resection specimen, after which they were snap frozen and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction. All collected tissues were subsequently reviewed to ensure cancer site and pathological diagnosis of cancer by a pathologist (P.T). All cases were primary tumors that had not been treated with radiation or chemotherapy.

Clinicopathological parameters of the patients were retrieved from medical records. The patient information extracted from the database was date of birth, sex, vital status, history of smoking and alcohol consumption, date of diagnosis, stage, and treatment. Pathological information was obtained from pathological reports. Date of death was obtained from the national civil registration system.

Mutation detection using conventional polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh tissue using an E.Z.N.A Tissue DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), and the procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PIK3CA gene analysis was performed in exons 4, 9, and 20; 100 ng of DNA was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the following primer sets: PIK-3CA-exon 4 forward (5′-CATCTTATTCCAGACGCATTTC-3′), PIK3CA-exon 4 reverse (5′-AGATTACTGTATAGTGCAAGA AAA-3′), PIK3CA-exon 9 forward (5′-CCAGAGGGGAAAAA TATGACA-3′), PIK3CA-exon 9 reverse (5′-CATTTTAGCACT TACCTGTGAC-3′), PIK3CA-exon 20 forward (5′-CATTTGC TCCAAACTGACCA-3′), and PIK3CA-exon 20 reverse (5′-TG AGCTTTCATTTTCTCAGTTATCTTTTC-3′). The PCR conditions for PIK3CA exons 4 and 9 were denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes; amplification for 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds; and extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. The PCR conditions for PIK3CA exon 20 were denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes; amplification for 45 cycles at 95°C for 45 seconds, 58°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute; and extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. All gene sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM 3730xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). DNA sequences were analyzed to ascertain point mutations in PIK3CA exons 4, 9, and 20. The conventional PCR technique was performed in certain samples to determine the reference point mutations. Then, allele-specific real-time PCR was performed for the remaining tissue samples.

Allele-specific real-time PCR

Reference point mutations were used to design allele-specific probes (dual-labeled fluorogenic probes) to develop a real-time PCR technique. The allele-specific probes were composed of short DNA sequences covering the mutational areas. The probes were labeled with two fluorescent dyes: HEX for the PIK3CA wild-type allele and FAM for the mutated allele (Sigma-Aldrich, Singapore). BHQ-1 was used as a quencher. For all samples, 20 ng of DNA was obtained and subjected to real-time PCR using previously described primer sets and allele-specific probe sets (Table 1). PCR mixtures contained 10 μL of 2 × FastStart Essential DNA Probes Master buffer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 0.5 μL forward primer, 0.5 μL reverse primer, 0.25 μL wild-type probe, 0.25 μL mutated probe, 6.5 μL molecular grade water, and 20 ng DNA in a final volume of 20 μL. The real-time PCR conditions for PIK3CA exon 9 were 95°C, 3 minutes and (95°C, 10 seconds; 58°C, 30 seconds) × 45 cycles. The real-time PCR conditions for PIK3CA exon 20 were 95°C, 3 minutes and (95°C, 10 seconds; 62°C, 30 seconds; 72°C, 30 seconds) × 45 cycles. Template controls were not included in each real-time PCR run. All samples were subsequently subjected to real-time PCR using the probes. Five mutant specimens served as positive controls.

Table 1.

Allele-specific probes

| Probe name | Type | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA exon 9 G>A | Wild-type probe | 5′-(HEX) CTCTCTGAAATCACTGAGCAGGAGAA (BHQ-1)-3′ |

| PIK3CA exon 9 G>A | Mutated probe | 5′-(FAM) CTCTCTGAAATCACTAAGCAGGAGAA (BHQ-1)-3′ |

| PIK3CA exon 20 A>G | Wild-type probe | Anti-sense 5′ (HEX) AGCCACCATGATGTGCATCATTC (BHQ-1)-3′ |

| PIK3CA exon 20 A>G | Mutated probe | Anti-sense 5′ (FAM) AGCCACCATGACGTGCATCATTC (BHQ-1)-3′ |

| PIK3CA exon 20 C>T | Wild-type probe | 5′-(HEX) ACATTCGAAAGACCCTAGCCTTAGAT (BHQ-1)-3′ |

| PIK3CA exon 20 C>T | Mutated probe | 5′-(FAM) ACATTCGAAAGACTCTAGCCTTAGAT (BHQ-1)-3′ |

PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the data between the two groups of patients. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare proportional data, and Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess the differences in continuous data. Descriptive results are presented as the median (continuous variable) and percentage (categorical variable).

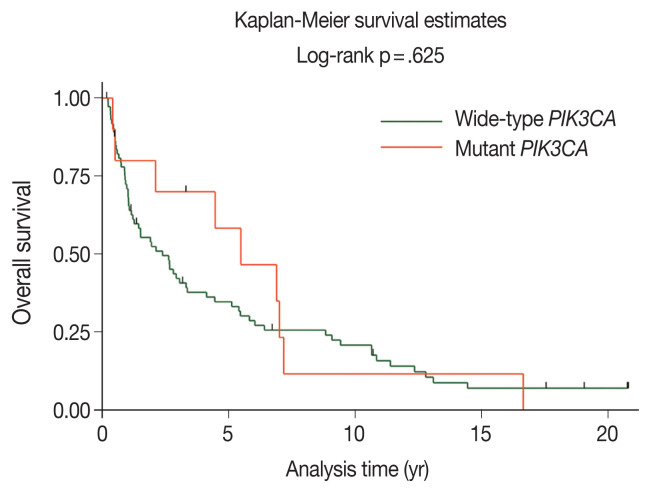

Duration of follow-up and overall survival (OS) time were calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of last follow-up or date of death from any cause, respectively. The data of patients who were alive at the last date of follow-up, December 20, 2021, were censored. The survival curve was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparisons of survival curve among groups were performed using the log-rank test.

Stata/MP ver. 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to perform all analyses. p-values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The samples used in this study comprised 96 HNSCC samples diagnosed from 2002–2003. The study included primary tumors originating from the oral cavity (n = 63), hypopharynx (n = 23), and oropharynx (n = 10). The patient demographics and their baseline clinical characteristics were available for 84 cases and are shown in Table 2; 49 cases were male, and the median age at diagnosis was 68 years.

Table 2.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Variable | Total (n = 84) | Wild-type PIK3CA (n = 74) | Mutant PIK3CA (n = 10) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | .100 | |||

| Median ± SD | 68 ± 12.6 | 68 ± 12.8 | 70 ± 9.7 | |

| Sex | .307 | |||

| Male | 49 (58.3) | 45 (60.8) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Female | 35 (41.7) | 29 (39.2) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Smoking | .324 | |||

| Yes | 47 (56.0) | 43 (58.1) | 4 (40.0) | |

| No | 37 (44.0) | 31 (41.9) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Alcohol drinking | .182 | |||

| Yes | 44 (52.4) | 41 (55.4) | 3 (30.0) | |

| No | 40 (47.6) | 33 (44.6) | 7 (70.0) | |

| Tumor location | .380 | |||

| Oral cavity | 57 (67.9) | 51 (68.9) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Tongue | 14 (16.7) | 13 (17.6) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Gums | 13 (15.4) | 12 (16.2) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Buccal mucosa | 11 (13.1) | 10 (13.5) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Floor of mouth | 6 (7.1) | 5 (6.7) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Lip | 5 (6.0) | 3 (4.1) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Hard palate | 4 (4.8) | 4 (5.4) | 0 | |

| Retromolar area | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.7) | 0 | |

| Oral cavity (unspecified) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.7) | 0 | |

| Oropharynx | 6 (7.1) | 6 (8.1) | 0 | |

| Base of tongue | 6 (7.1) | 6 (8.1) | 0 | |

| Hypopharynx | 21 (25.0) | 17 (23.0) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Pyriform sinus | 21 (25.0) | 17 (23.0) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Clinical stage | .628 | |||

| I | 16 (19.0) | 14 (18.9) | 2 (20.0) | |

| II | 17 (20.3) | 13 (17.6) | 4 (40.0) | |

| III | 19 (22.6) | 18 (24.3) | 1 (10.0) | |

| IVa | 29 (34.5) | 26 (35.1) | 3 (30.0) | |

| IVb | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | |

| IVc | 2 (2.4) | 2 (2.7) | 0 | |

| Treatment | .337 | |||

| Surgery | 23 (27.4) | 18 (24.3) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Surgery followed by RT | 42 (50.0) | 38 (51.4) | 4 (40.0) | |

| RT | 13 (15.5) | 12 (16.2) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Best supportive care | 6 (7.1) | 6 (8.1) | 0 |

Values are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; SD, standard deviation; RT, radiotherapy.

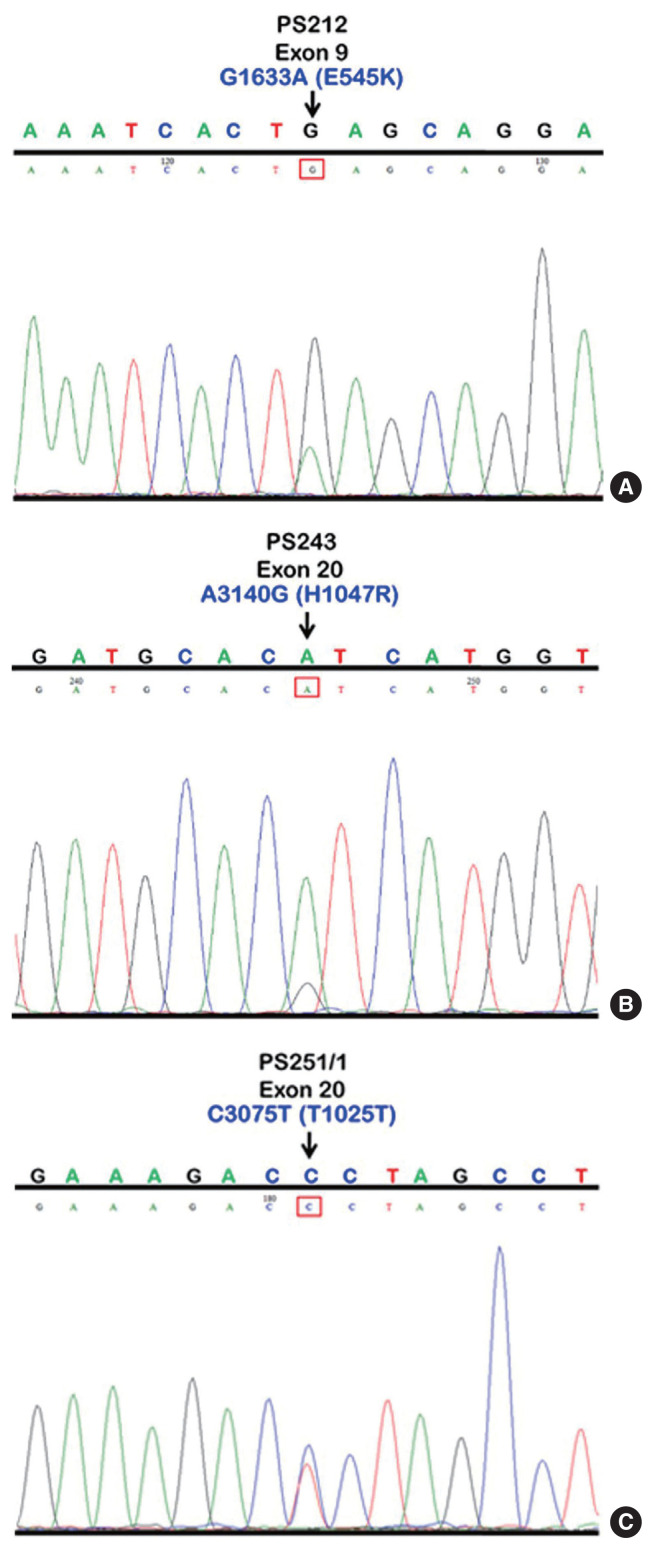

We initially identified three PIK3CA point mutations using conventional PCR (Fig. 1A–C): one in exon 9 and two in exon 20. Mutations were not detected in exon 4. We then applied these known mutations as a reference to design allele-specific probes (dual-labeled fluorogenic probes) as shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PIK3CA mutations in exons 9 and 20 using conventional PCR as illustrated in sequencing chromatograms showing a missense mutation in sample No. PS212 at position 1633, G>A (E545K) in exon 9 (A), a missense mutation in sample No. PS243 at position 3140, A>G (H1047R) in exon 20 (B), and a silent mutation in sample No. PS251/1, C>T (T1025T) in exon 20 (C). PIK-3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

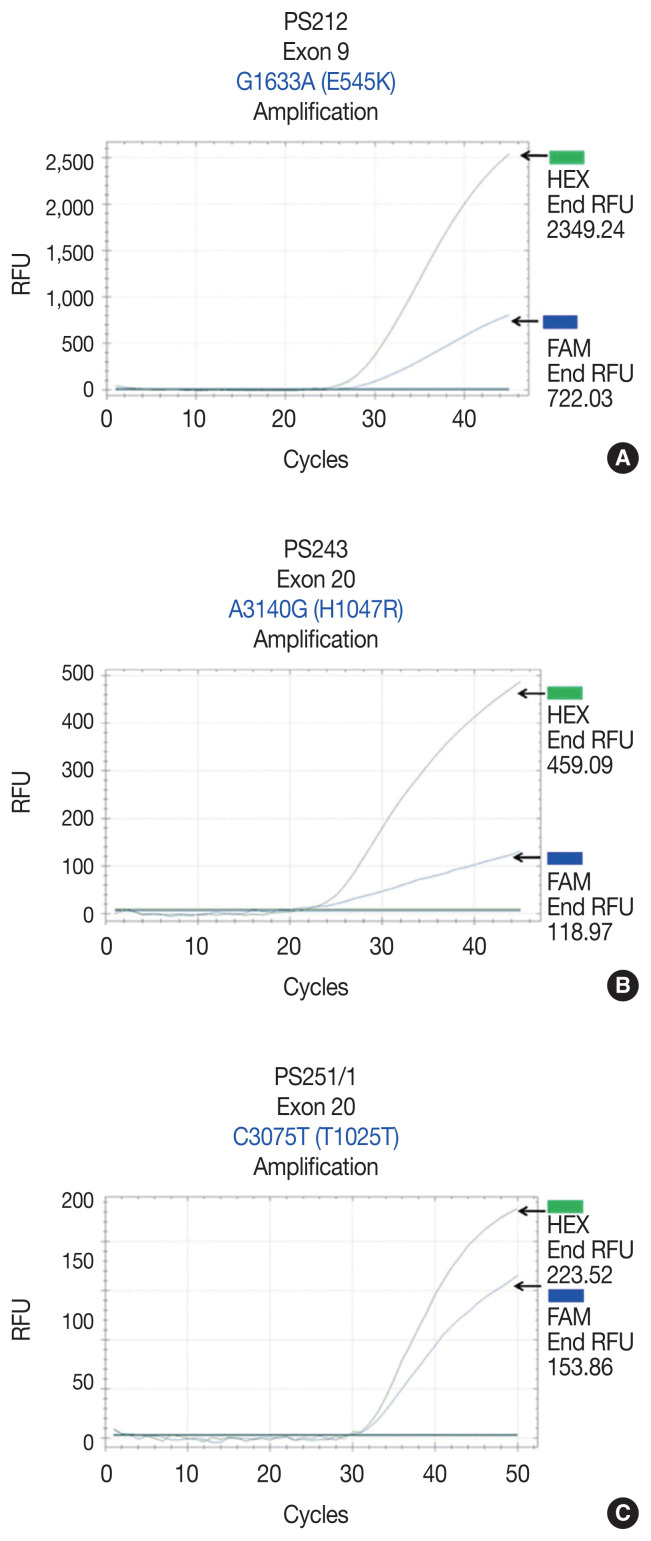

We found PIK3CA mutations in 10 of 96 samples (10.4%) with all heterozygous mutations. When the patients were classified based on mutational events in the primary tumor location, 17.4% (4/23) with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (HPSCC) and 9.5% (6/63) with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) had PIK3CA mutations. No patient (0/10) with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) had PIK3CA mutations (Table 3). Clinical characteristics between patients with or without PIK3CA mutations were not statistically significantly different (Table 2). The patient characteristics and details of PIK3CA mutations are shown in Table 4. Two patients had exon 9 mutations (Fig. 2A) and eight had exon 20 mutations (Fig. 2B, C). The 10 mutations were categorized as five missense and five silent mutations, which corresponded to E545K in exon 9 and T1025T and H1047R in exon 20. E545K (GAG1633AAG) and H1047R (CAT3140CGT) are missense mutations, and T1025T (ACC3075ACT) is a silent mutation.

Table 3.

Frequency of PIK3CA mutations in HNSCC by subsite

| Subsites of HNSCC | PIK3CA mutation | Overall PIK3CA mutations | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Exon 9 | Exon 20 | ||

| Oral cavity | 0/63 (0) | 6/63 (9.5) | 6/63 (9.5) |

| Oropharynx | 0/10 (0) | 0/10 (0) | 0/10 (0) |

| Hypopharynx | 2/23 (8.7) | 2/23 (8.7) | 4/23 (17.4) |

Values are presented as number (%).

PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 4.

Mutational status of PIK3CA in HNSCC

| Sample No. | Age at diagnosis (yr) | Sex | Tumor location | Exon | Nucleotide | Codon change | Amino acid change | Type of mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS212 | 76 | Male | Pyriform sinus | 9 | G1633A | GAG to AAG | E545K | Missense |

| PS220 | 62 | Female | Pyriform sinus | 9 | G1633A | GAG to AAG | E545K | Missense |

| PS243 | 72 | Male | Pyriform sinus | 20 | A3140G | CAT to CGT | H1047R | Missense |

| PS251/1 | 63 | Male | Pyriform sinus | 20 | C3075T | ACC to ACT | T1025T | Silent |

| OR183 | 58 | Female | Buccal mucosa | 20 | C3075T | ACC to ACT | T1025T | Silent |

| OR214 | 90 | Female | Tongue | 20 | C3075T | ACC to ACT | T1025T | Silent |

| OR378 | 79 | Female | Gums | 20 | C3075T | ACC to ACT | T1025T | Silent |

| OR391 | 69 | Male | Floor of mouth | 20 | C3075T | ACC to ACT | T1025T | Silent |

| OR205 | 79 | Female | Lip | 20 | A3140G | CAT to CGT | H1047R | Missense |

| OR209 | 66 | Female | Lip | 20 | A3140G | CAT to CGT | H1047R | Missense |

PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Fig. 2.

Amplification plot of allele-specific real-time PCR showing PIK3CA mutations in exon 9 and exon 20 and the HEX (green, wild-type PIK3CA allele) and FAM (blue, mutated PIK3CA allele) signals. (A) A missense mutation in sample No. PS212 at position 1633, G>A (E545K) in exon 9. (B) A missense mutation in sample No. PS243 at position 3140, A>G (H1047R) in exon 20. (C) A silent mutation in sample No. PS251/1, C>T (T1025T) in exon 20. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

The majority of patients with wild-type PIK3CA (51.4%) underwent surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy; however, patients with PIK3CA mutations underwent only surgery (50.0%), as shown in Table 2. The median duration of follow-up was 2.11 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21 to 3.26). The 5-year OS rates in the wild-type PIK3CA and mutant PIK3CA were 35% (95% CI, 24 to 46) and 58% (95% CI, 23 to 82), respectively (Fig. 3). There was no statistically significant difference in OS rate between the two groups (p = .625).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival for patients with wild-type PIK3CA or mutant PIK3CA. PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha.

DISCUSSION

In HNSCC, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is the most frequently altered oncogenic pathway associated with tumor proliferation and survival [4,5]. Reportedly, PIK3CA mutations are associated with advanced stage of HNSCC, particularly in subjects with oral squamous cell carcinoma, indicating that PIK-3CA mutations play an important role in the carcinogenesis of HNSCC [9,15]. In the present study, we evaluated the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in the different subsites of HNSCC in the Thai population.

When divided by primary tumor location, we detected a higher mutation rate in HPSCC than in OCSCC (17.4% vs. 9.5%). We also found a slightly higher PIK3CA mutation rate in HPSCC than reported in a study in the Chinese population (13.6%) [16]. The frequency of PIK3CA mutations in OCSCC in the present study (9.5%) was slightly higher than the 7.4% frequency reported in the Japanese population [9]. Notably, Kommineni et al. [15] reported a substantially high PIK3CA mutation rate of 52% in OCSCC tumor samples from Indian patients. Taken together, these findings might highlight the effect of diverse mutation rates even among Asian populations.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a well-known risk factor associated with OPSCC. Nichols et al. [17] reported a higher frequency of PIK3CA mutations in HPV-related OPSCC than HPV-negative tumors (28% vs. 10%). In the present study, we found no PIK3CA mutation in any patient with OPSCC. This result was discordant from those of a study by Beaty et al. [18] showing a PIK3CA mutation rate of 21% in patients with HPV-associated OPSCC. The reason for the discordance might be the small sample cohort in the OPSCC subgroup in the present study. Furthermore, information regarding HPV status in these patients was unknown due to the lack of sufficient specimens. However, in previous studies, the proportion of HPV-related OPSCC in Thai patients was remarkably low (15%–20%) [19,20] compared with 40%–60% reported in Western patients [21]. Thus, the correlation between PIK3CA mutations and HPV status should be further explored in Asian populations.

In the present study, PIK3CA mutations in exon 4 were not detected. In contrast, a previous study reported mutations in exon 4, with a rate of 2.6% in an oral cavity carcinoma cell line (primary tumor originated in the tongue) [8]. In the present study, the overall 10.4% mutation rate of PIK3CA, which included 2.1% in exon 9 (E545K) and 8.3% in exon 20 (H1047R and T1025T), was not significantly different from previous studies (9%–13% in non-nasopharyngeal carcinoma), as shown in Table 5. However, a higher mutation rate of 21% in pharyngeal carcinoma and 21% in oropharyngeal carcinoma were reported in two studies [11,18]. In those studies, a more advantageous technique, a novel mutant-enriched sequencing method, was used for analysis, which could explain the difference in results.

Table 5.

Previous studies of PIK3CA mutations in HNSCC

| Authors (year) | Location of HNSCC | PIK3CA mutations (%) | Type of mutation | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qiu et al. (2006) [8] | HNSCC | 11 (4/38) | Point mutation | 4, 9, and 20 |

| Kozaki et al. (2006) [9] | Oral cavity | 9 (11/122) | Point mutation | 9 and 20 |

| Qiu et al. (2008) [11] | Pharynx | 21 (5/24) | Point mutation | 9 and 20 |

| Murugan et al. (2008) [12] | HNSCC | 13 (7/54) | Point mutations, frameshift | 9 and 20 |

| Kommineni et al. (2015) [15] | HNSCC | 60.46 | Point mutation | 9 and 20 |

| Wu et al. (2017) [16] | Hypopharynx | 13.6 | Point mutation | 9 and 20 |

| Beaty et al. (2020) [18] | Oropharynx | 21 (16/77) | Point mutation | 9 and 13 |

| Lui et al. (2013) [32] | HNSCC | 12.6 (19/151) | Point mutation | 9, 20, and novel mutations |

PIK3CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

We found two of the three types of PIK3CA mutations, E545K and H1047R, which have been previously reported as hotspot mutations [22–24]. E545K is located on exon 9 in the helical domain of PIK3CA, and H1047R and T1025T are encoded by exon 20 within the kinase domain [25]. The E545K mutation disrupts an inhibitory charge–charge interaction between p110α and the N-terminal SH2 domain of the p85 regulatory subunit, and the H1047R mutation increases the binding affinity between p110α and the negatively charged phosphatidylinositol substrate [26–28]. The functional effect of these two hotspot mutations has been well established in many studies, showing the gain-of-function PI3K activity and downstream signaling via the AKT/mTOR pathway [22,23]. Furthermore, the benefit of PIK3CA mutations as a predictive marker for novel targeted therapies has been demonstrated. Alpelisib, an oral selective PI3K inhibitor, has been implemented in current practice for patients with advanced breast cancer harboring PIK3CA mutations [29,30]. The efficacy and safety of PI3K or mTOR inhibitors are being evaluated in several clinical trials for patients with advanced HNSCC [31]. In contrast to the previously mentioned two hotspot mutations, T1025T is categorized as a silent mutation. Notably, we detected the T1025T mutation, which was significantly high in OCSCC, in 4 of 5 mutant cases in the present study. This was concordant with a previous study in which the T1025T mutation was reportedly prominent in OCSCC [15]. However, whether the T1025T silent mutation is the oncogenic driver in HNSCC remains controversial. Kommineni et al. [15] reported a significantly higher frequency of T1025T silent mutation in patients with HNSCC (41.0%) than in healthy controls (16.7%, p < .001). In contrast, Dogruluk et al. [28] identified T1025T as a genetic variant in the human germline.

In the present study, clinical significance was not observed based on the presence or absence of PIK3CA mutations. This finding was similar to a previous study in which significant difference was not observed in clinical characteristics between patients with wild-type PIK3CA or mutant PIK3CA OPSCC [18]. However, the presence of a PIK3CA mutation in that study was associated with poorer disease-free survival among patients receiving de-intensified definitive chemoradiotherapy for HPV-related OPSCC [18]; survival did not differ between the two groups in the present study. This contradictory finding might be explained by the small sample cohort in the present study. A larger study in which PIK3CA mutations are investigated as a potentially prognostic factor in patients with OPSCC and non-OPSCC is warranted.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in HNSCC in Thailand. However, the limitations of the study included small sample size, particularly in the OPSCC subgroup, and lack of available data regarding HPV status. The absence of PIK3CA mutations in OPSCC might be due to the smaller number of samples tested than those at other subsites. Furthermore, testing for PIK3CA mutations in normal tissue from these patients was not performed; hence, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding involvement of the T1025T silent mutation in the pathogenesis of HNSCC or its involvement as a genetic variant in the human germline.

In conclusion, our study showed a higher frequency of PIK-3CA mutations in HPSCC than in OCSCC. The results suggest that these mutations are involved in carcinogenesis and could serve as biomarkers for novel targeted therapies as well as immunomodulators in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Furthermore, the hypopharynx is suggested as a primary site of interest for further studies, particularly in Southeast Asian populations.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University (REC 56-498-14-1) with a waiver of informed consent.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AD. Data curation: PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara), TD. Formal analysis: AD, PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara), PT (Paramee Thongsuksai), TD, SLG. Funding acquisition: AD. Investigation: PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara). Methodology: PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara), PT (Paramee Thongsuksai). Project administration: AD. Resources: PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara), PT (Paramee Thongsuksai). Supervision: AD, PT (Paramee Thongsuksai). Validation: PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara), PT (Paramee Thongsuksai). Visualization: AD, PT (Paramee Thongsuksai). Writing—original draft: AD, PT (Phatcharaporn Thongwatchara). Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand.

References

- 1.Cohen N, Fedewa S, Chen AY. Epidemiology and demographics of the head and neck cancer population. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2018;30:381–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospital-based cancer registry 2016 [Internet] Bangkok: National Cancer Institute, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand; [cited 2021 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.nci.go.th/th/File_download/Nci%20Cancer%20Registry/Hospital-Based%20NCI2%202016%20Web.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Valera JC, Zhao X, Chen Q, Gutkind JS. mTOR co-targeting strategies for head and neck cancer therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017;36:491–502. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:627–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karakas B, Bachman KE, Park BH. Mutation of the PIK3CA oncogene in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:455–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu W, Schonleben F, Li X, et al. PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1441–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Pimkhaokham A, et al. PIK3CA mutation is an oncogenic aberration at advanced stages of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Or YY, Hui AB, To KF, Lam CN, Lo KW. PIK3CA mutations in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1065–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu W, Tong GX, Manolidis S, Close LG, Assaad AM, Su GH. Novel mutant-enriched sequencing identified high frequency of PIK3CA mutations in pharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1189–94. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murugan AK, Hong NT, Fukui Y, Munirajan AK, Tsuchida N. Oncogenic mutations of the PIK3CA gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2008;32:101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou CC, Chou MJ, Tzen CY. PIK3CA mutation occurs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma but does not significantly influence the disease-specific survival. Med Oncol. 2009;26:322–6. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fendri A, Khabir A, Mnejja W, et al. PIK3CA amplification is predictive of poor prognosis in Tunisian patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2034–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kommineni N, Jamil K, Pingali UR, Addala L, M V, Naidu M. Association of PIK3CA gene mutations with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Neoplasma. 2015;62:72–80. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu P, Wu H, Tang Y, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals novel mutations and epigenetic regulation in hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:85326–40. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols AC, Palma DA, Chow W, et al. High frequency of activating PIK3CA mutations in human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:617–22. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaty BT, Moon DH, Shen CJ, et al. PIK3CA mutation in HPV-associated OPSCC patients receiving deintensified chemoradiation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:855–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsa L, Siripoon T, Trachu N, et al. Discrepancy in p16 expression in patients with HPV-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Thailand: clinical characteristics and survival outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:504. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08213-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Argirion I, Zarins KR, McHugh J, et al. Increasing prevalence of HPV in oropharyngeal carcinoma suggests adaptation of p16 screening in Southeast Asia. J Clin Virol. 2020;132:104637. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehanna H, Beech T, Nicholson T, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013;35:747–55. doi: 10.1002/hed.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang S, Bader AG, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408864102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davoli T, Mengwasser KE, Duan J, et al. Functional genomics reveals that tumors with activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase mutations are dependent on accelerated protein turnover. Genes Dev. 2016;30:2684–95. doi: 10.1101/gad.290122.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustin JP, Cosgrove DP, Park BH. The PIK3CA gene as a mutated target for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:733–40. doi: 10.2174/156800908786733504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miled N, Yan Y, Hon WC, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang S, Bader AG, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Mutated PI 3-kinases: cancer targets on a silver platter. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:578–81. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.4.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dogruluk T, Tsang YH, Espitia M, et al. Identification of variant-specific functions of PIK3CA by rapid phenotyping of rare mutations. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5341–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andre F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1929–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andre F, Ciruelos EM, Juric D, et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: final overall survival results from SOLAR-1. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung K, Kang H, Mehra R. Targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) Cancers Head Neck. 2018;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s41199-018-0030-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lui VW, Hedberg ML, Li H, et al. Frequent mutation of the PI3K pathway in head and neck cancer defines predictive biomarkers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:761–9. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]