Abstract

Behavior analytic interventions for people with disabilities often rely on implementation by novice caregivers and staff. However, behavior intervention documents are ineffective at evoking the level of performance needed for behavior change, and intensive training is often needed (Dogan et al., 2017; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012). The cost and time requirements of intensive training may not be viable options for some clients, leading to nonadherence or attrition (Raulston et al., 2019). In addition, others may feel that prescribed interventions are not appropriate or will not work (Moore & Symons, 2011). These barriers may reflect a cultural mismatch (Rathod et al., 2018). One potential way to increase efficacy of intervention materials is to improve the cultural sensitivity and comprehensibility of these documents. Although the body of research on cultural adaptation of behavioral interventions is becoming more robust, adaptation of behavior intervention documents as a means to create effective behavior change when cultural and linguistic diversity are factors, is an area of behavior analytic practice that is not well researched and there remains a need for cultural humility. Because diversity can include expansive differences between individuals, such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, gender and sexuality; understanding and adapting to each of these areas may be best done through separate reviews. It is the intent of this article to focus on ethnic diversity in the United States as a starting point and frame of reference for cultural adaptation. This tutorial includes tips learned from health communication research to give step-by-step guidance on creating comprehensible, culturally adapted intervention plans through the example of training for parents of autistic children.

Keywords: Behavior intervention plans, Comprehensibility, Cultural and linguistic diversity, Deep structure, Ethnic, Parent treatment integrity, Race, Surface structure

Culture is a widely used and sometimes misunderstood term. It is more than just a fixed categorization of a group of people. It goes beyond race and ethnicity and is more than a label of lifestyle or socioeconomic status (Kreuter & McClure, 2004). Instead, culture is a dynamic compilation of socially established beliefs, values, and practices that are shared by members of groups and subgroups, to varying levels across individuals. Culture is transmitted across generations, and learned through family, friends, and community (Kreuter & McClure, 2004). The adaptive nature of culture results in aggregates of complex, dynamic interactions, beliefs and behaviors that epitomize cultural and linguistic diversity (Brodhead et al., 2014). Because culture can exist within groups large and small, a person can be culturally related to those with whom they are housed, neighbors that share a locale (e.g., town or city), peers attending the same school or educational program, members of clubs and cliques, coworkers sharing an employment site, and people attending the same religious establishment. They can share culture with others of similar regional experiences (e.g., West Coast vs. Southern living), those having the same country of birth, people of the same race and ethnicity, and so on. Because culture is intersectional, it varies widely across individuals and can affect behavior and health. Behavior analysts therefore must use this information to create appropriate treatments (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2014; Fong & Tanaka, 2013).

Treatments reflecting cultural sensitivity (CS) often have positive effects on client outcomes (Barrera et al., 2013; Di Noia et al., 2013; Kline et al., 2016; Singelis et al., 2018; Woodruff et al., 2002), however, failure to culturally adapt intervention materials may hinder client outcomes (Barrera et al., 2013; Kumpfer et al., 2017; Rathod et al., 2018). Yet, health disparities continue to be pervasive in our society and intervention outcomes for minoritized and marginalized people remain lower than outcomes for white Americans (Becerra et al., 2014; Rathod et al., 2018; Stubbe, 2020). Further, behavior analysts are mandated to practice with cultural competence when working with clients of diverse (nonmajority, marginalized, and/or minoritized) backgrounds in order to provide effective interventions (BACB, 2014; Fong & Tanaka, 2013). Despite a growing body of research on culturally adapted behavior interventions (Bernal & Adames, 2017), there has been little behavior analytic research on enhancing behavior intervention plan documents to be more effective with non-white ethnic groups (Quigley et al., 2018) for which cultural and linguistic diversity may be factors (Wang et al., 2019).

Cultural awareness describes knowing one’s own culture and biases. Cultural awareness is a component of cultural sensitivity, which goes a step forward to include recognizing and working through our biases, so we can relate to others from a perspective of cultural acceptance (Benuto et al., 2021). We provide a list of culture-related terms that are often interrelated but distinctive in Table 1 as a resource to readers who are less familiar with the topics of culture, diversity, equity, and inclusion. Thus, the ability to create effective culturally sensitive intervention materials would be a staple of cultural competence. Cultural knowledge, cultural awareness, and cultural skills are the three main components generally regarded as key to cultural competence, though these do not represent every possible component (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016).

Table 1.

Cultural Adaptation Terminology

| Term | Definition | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cultural awareness | Acknowledging one’s own cultural beliefs and one’s biases related to varying ethnic and cultural values, beliefs, and practices. | (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016) |

| 2. | Cultural competence | Development of thorough understanding of disparities between values, beliefs, and practices including cultural knowledge, cultural awareness, and cultural skills. | (Fong & Tanaka, 2013) |

| 3. | Cultural humility | “Entering a relationship with another person with the intention of honoring their beliefs, customs, and values. It entails an ongoing process of self-exploration and self-critique combined with a willingness to learn from others.” | (Stubbe, 2020, p 49) |

| 4. | Cultural knowledge | Gathering information on the values, beliefs, and practices of others’ cultures. | (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016) |

| 5. | Cultural sensitivity | Being aware of the differences and biases between one’s own culture and the cultures of others, as well as relating to others from a perspective of cultural acceptance. In health documents, it can be understood in terms of appropriate cultural adaptation of surface and deep structures. |

(Benuto et al., 2021) (Resnicow et al., 1999) |

| 6. | Cultural skills | The ability to effectively interact with people of diverse cultural backgrounds, including adapting and applying interventions that are culturally sensitive. | (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016) |

| 7. | Cultural targeting | Adapting health communication materials to match characteristics such as values and beliefs shared by a cultural group. | (Halder et al., 2008) |

| 8. | Cultural tailoring | Adapting health communication materials to reach a specific individual based on unique cultural characteristics determined through assessment. | (Halder et al., 2008) |

| 9. | Deep structure | Incorporating sociocultural values and beliefs into materials through text. | (Resnicow et al., 1999) |

| 10. | Surface structure | Incorporating visual agreement (such as in images) with the cultural group, such as common facial features, clothing, and other environmental arrangements. | (Resnicow et al., 1999) |

The terms listed in the table reflect the authors’ corroborated interpretation and use within this article. These are by no means all terms relevant to all possible cultural adaptation situations, nor are these the only interpretations for the terms listed. Instead, these are the definitions that most aligned with the intent of this tutorial.

Cultural knowledge is knowing the values, beliefs, and practices of others’ cultures. Cultural knowledge is not a goal that can be met, but rather a dynamic value that drives continued self-education of others in order to develop an understanding of other ethnocultural groups (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016). Although reviewing literature is commonly used to build cultural knowledge (Coard et al., 2004; Leeman et al., 2008; Nierkens et al., 2013; Singelis et al., 2018), additional methods such as working with focus groups (Leeman et al., 2008; Singelis et al., 2018; Webb et al., 2007), sending out surveys (Davis et al., 2011; Kline et al., 2016; Leeman et al., 2008), and combinations of these can be effective strategies to gain current information that builds on the literature. For example, in order to create a diabetes self-management intervention for older Black women in rural areas, Leeman et al. (2008) relied on decades of personal experiences with diabetes care, review of the literature, and an exploratory study using surveyed representatives. The survey included 44 items and investigated Type 2 diabetes symptoms in 75 older Black women (i.e., age 55 and up). This informed the research team of the 16 most common current symptoms the women were experiencing, the severity of presenting symptoms, comorbidities, overall quality of life, and barriers to self-care. Combined information-gathering efforts such as these are both appropriate and extensive methods of acquiring cultural knowledge.

Cultural awareness can be tricky as it requires ongoing self-reflection and mindful interaction with people of different backgrounds, including participating in nonjudgmental cultural experiences such as story circles (Deardorf, 2020). In addition to cultural knowledge, Leeman et al. (2008) showed cultural awareness when despite having 30 years of experience with diabetes care, the authors recognized that they needed to learn more about current challenges for their target population, variations amongst individuals, and personal perspectives on supports and needs.

Having cultural skills describes the ability to effectively interact with people of different cultural backgrounds (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016). Without an honest investigation of one’s own ethnocentric attitudes, it may be hard to successfully apply cultural skills (Deardorf, 2020). Even when training in cultural knowledge is evident, directly training cultural skills (Benuto et al., 2021) may be absent, perhaps explaining why practitioners have been slow to culturally adapt behavior intervention materials across ethnic groups. Lack of cultural skills among practitioners might contribute to the limited behavioral research testing the effects of culturally sensitive materials on intervention outcomes—a research area that is greatly needed (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016) and a gap that is concerning because behavior analysts are ethically mandated to be competent and effective with clients from different backgrounds (BACB, 2014; Fong & Tanaka, 2013).

Effectively tailoring interventions aligned to each individual’s background exemplifies cultural skills and is especially important because many behavior analytic interventions recommended may not have been tested for efficacy across all cultural groups (Bernal & Adames, 2017; Jones et al., 2020). For example, Leeman et al. (2008) demonstrated cultural skills by creating surveys to inform intervention materials, running focus groups to refine materials, and creating individualized materials based on each participant’s assessment of symptom expression and functional needs. The nurses used active listening during staff training and interaction, while using storytelling to supplement written materials with patients. The researchers incorporated into materials the pertinent cultural themes such as spirituality, caregiving responsibilities, and family role, as well as stressors such as transportation, medication, and comorbidity. Cultural skills such as these have also been demonstrated by practitioners from other disciplines. For example, cultural skills have been applied when creating cancer prevention messaging of mammography and diet in health magazines for Black women (Kreuter et al., 2003), Telenova entertainment-education interventions for diabetes self-management in Latine populations (Kline et al., 2016), child oral health pamphlets for Spanish-speaking mothers of Mexican descent (Singelis et al., 2018), and in-home smoking cessation programs with culturally adapted curricula—including themes such as familismo, simpatía, and collectivism—for Latine participants (Woodruff et al., 2002).

Often, research on culturally tailored intervention materials is being completed by professionals who are not behavior analysts and published in nonbehavior-analytic journals that may be regarded as health communication research, such as Tobacco Control, Journal of Health Communication, Health Education and Behavior, and The Diabetes Educator (Kline et al., 2016; Leeman et al., 2008; Singelis et al., 2018; Woodruff et al., 2002). With behavior-analytic research being extremely limited in this area, we may need to begin this body of research using the guidelines that health communication research has thus far developed. This should be a starting point for the effective cultural adaptation of behavior analytic intervention materials as more research will be needed to empirically support recommended guidelines.

The ability to culturally adapt behavior intervention materials to effectively increase user fidelity is a cultural skill that behavior analysts greatly need. For example, when conducting parent training programs for autistic children, if contingencies of the parent’s social community (i.e., cultural group) are in contrast to behavioral recommendations, this can lead to parental nonadherence (Allen & Warzak, 2000). Allen and Warzak (2000) recommend altering these effects through use of verbal instructions. Behavior intervention plans (BIPs) are a widely used example of verbal instructions given by behavior analysts. However, standard behavior intervention documents often fail to produce the level of performance that novice implementers need in order to make meaningful improvements in client behavior—unless combined with more intrusive training components. This may be related to the practitioner’s inexperience with adaptations related to cultural and linguistic diversity (Brodhead et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2019). The historically poor efficacy of written instructions on novice implementer performance is a likely reason why they are often used in baseline measures in training programs (Dogan et al., 2017; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012). In one example, Ward-Horner and Sturmey (2012) conducted a component analysis of behavioral skills training (BST) to teach functional analysis procedures to teachers. The study used a baseline phase with written instructions that described the purpose and steps of the procedures. Accuracy of teachers implementing the procedures ranged from 20%–22% on average. In a separate study by Dogan et al. (2017), BST was used to teach parents of autistic children to implement procedures of a social skills program. The baseline condition included written instructions and parent accuracy during this condition ranged 0%–13% on average. The low efficacy of written instructions should not be assumed to imply that behavior analysts do not make reasonable efforts to improve these documents. However, additional guidelines are needed to inform practitioners of the most appropriate methods for adapting intervention documents (Quigley et al., 2018).

When creating written materials for clients, behavior analysts use lay terms and parent friendly language. Although using conversational language in behavior intervention documents results in higher fidelity than when using technical terms (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008), contents of behavior intervention plans are often standardized based on essential components, rather than adapted to be usable and effective for a target audience (Quigley et al., 2018). Verbal behavior embedded in BIPs should evoke the desired listener behavior of the reader (Neuman, 2018), whose responding can also be influenced by cultural beliefs, values, and experiences (Allen & Warzak, 2000; Brodhead et al., 2014; Rathod et al., 2018). Although reasons behavior intervention plans are sometimes ineffective has not been systematically investigated, and could be the result of many factors, health communication research would suggest two main components that may be lacking: CS and comprehensibility (Catagnus et al., 2020; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2009; Resnicow et al., 1999). These areas are worthy of discussion as they can be adapted to enhance behavior intervention materials. The following sections review CS and comprehensibility adaptations that can be applied to behavior intervention documents. Tables 3, 4, and 5 provide specific recommendations for application to BIPs. The proposed guidelines will need empirical support; however, this tutorial serves as a starting point for research, and a foundation for cultural and comprehensible adaptation of behavior intervention plan documents to be used in combination with other empirical procedures.

Table 3.

Guidelines for General BIP Adaptation Process

| Step | Description | Example / Nonexample | Social Validity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Information gathering | Review the literature to gain information on cultural trends of the population, cultural implications for presenting behavioral challenges, and enablers and barriers to treatment, before creating the BIP. It is important for the practitioner to be humble and acknowledge that personal experiences are a glimpse from a single perspective and that additional information from the perspective of the target population is needed. This can include interviews, surveys, focus groups and other means of information gathering (Barrera et al., 2013). |

Example: Creating parent training materials for autistic children after reviewing the literature on enablers and barriers to treatment for the relevant cultural group and interviewing population representatives to see what their priorities and needs are. Nonexample: When creating parent training materials for autistic children, use your own insight, past experiences, and current understanding of the population to create materials without doing additional information gathering. |

To understand and plan for the specific cultural beliefs, values and needs of your clients. |

| 2. | Preliminary design | Start by creating comprehensible empirical interventions based on the function and topography of the behavior, environmental constraints, and client preferences (see “Comprehensibility” section for specifics). Next, adapt the evidence-based procedures to represent the cultural beliefs and values of the client, while maintaining the core content and procedural integrity of the prescribed protocols (see “Cultural Adaptation of Deep Structure” section). It is important not to diminish the preciseness of the procedures when culturally adapting protocols as this would weaken the empiricism and likely efficacy of the intervention (Bernal & Adames, 2017). Use subject matter experts, representative focus groups, questionnaires and/or surveys about your materials (Barrera et al., 2013). |

Example: Creating parent training materials based on empirical recommendations after adapting steps of the procedure for comprehensibility and cultural appropriateness, and asking subject matter experts and representative individuals to rate them for appropriateness and consistency. Nonexample: Creating parent training materials based on the procedures that you always recommend for a given problem, tweaking phrases to replace jargon with lay terms, and distributing them for use with parents. |

To get input from the representative population and ensure that materials are likely to be culturally representative without being offensive. |

| 3. | Preliminary testing | Pilot materials with a small sample of representative participants and take data on qualitative and quantitative dimensions (Barrera et al., 2013). Qualitative dimensions could include things like ease of application, challenges with content or activities, the extent to which the materials helped solve the problem, preference for these materials compared to others, overall satisfaction with the program, and acceptability of the intervention. It would be advisable to ask about the acceptability of cost, time requirements, flexibility, whether the training felt supportive and professional (Raulston et al., 2019), goodness of fit for the family and community, whether parents think the intervention will work, and whether parents think they can perform the intervention (Moore & Symons, 2011). Quantitative measures could include fidelity of using the materials compared to standard materials (Barrera et al., 2013). This could be through percentage of steps performed correctly, trials to criterion; or other quantitative analysis of efficacy, maintenance and generalization. |

Example: Before giving the new materials to parents, have a small group of staff test out the materials to test comprehensibility and usefulness. Role play that you are the learner and the staff member is the parent implementing the strategy. Collect basic fidelity measures on staff performance of each step of the procedure. Solicit feedback on goodness of fit from staff familiar with the family. Adjust materials to be clearer and more precise if needed. Nonexample: Complete an initial draft of your materials and bring it to the target family for a test run. If the parent is offended or confused, make revisions. |

To make sure procedures are a good fit, culturally appropriate, and solve the problem they are intended for. |

| 4. | Refinement | Once case studies and or pilot studies end, use information gathered to refine materials and intervention protocols. |

Example: Based on feedback, adjust brightness, contrast, and sharpness of images. Zoom in or change images for clarity. Edit and revise text to reflect language that would be most easily understood by the target family. Remove distracting or confusing contents. Nonexample: Change technical terms to lay terms while maintaining all original information and tips. |

To revise the materials so that they are clear and precise before presenting them to the client’s family. |

| 5. | Final trial tailoring | When you are ready to conduct your final trial or use with your client’s family, be sure to use tools to tailor interventions to individual participants (Halder et al., 2008). Because you may have been creating templates for family BIPS up to this point, it would be important to further individualize the materials at this point. Tailoring will require you to use a survey or questionnaire that can be used to measure the extent to which the participant identifies with the cultural themes you identified during information gathering. For example, you can use the CIFA (Tanaka-Matsumi et al., 1996) to inform the type and extent of cultural surface and deep structure adaptations that you will embed for individual participants (see “Cultural Adaptation of Deep Structure” section for more information on how to use cultural domains to adapt deep structure). Specific instructions by Halder et al., (Halder et al., 2008) may be a good place to start for practitioners new to tailoring. |

Example: After creating parent training protocols and material samples that have been adapted to include themes that are common to Black American culture, you create a survey for each family to rate their agreement with the cultural themes displayed. Then you adapt each participant’s materials to reflect individual cultural tendencies before using them with clients. Nonexample: After creating parent training protocols and material samples that have been adapted to include themes that are common to Black American culture, you distribute them to all of your families assuming that the cultural themes will more-or-less fit all families and will work better than no adaptation. |

To further individualize the materials to fit the family culture. |

Guidelines for adapting behavior intervention materials are described using a focus on cultural differences related to ethnicity and through the perspective of materials created for parents of autistic children for illustrative purposes.

Table 4.

Guidelines for Applying Comprehensibility Adaptations to BIPs

| Step | Description | Example / Nonexample | Social Validity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Concisely tell the reader what to do | Plan to use each document as a focused tool. Always give the most important information first and limit information to no more than three to four main messages per document (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). This should focus on what the reader needs to do or know, rather than what is nice to know. Remember that the point of the document is to change behavior, knowledge, or beliefs so writing must stay clear, appropriate, and to the point. This should tell the reader what actions they should take in a concise manner. |

Example: “Quickly give a reward to Kiara after she finishes the task. Waiting to receive a reward can be frustrating for her.” Nonexample: “Try not to have long latencies (pauses between events and behaviors) when providing reinforcers to Kiara, even though these are sometimes unavoidable. Providing reinforcers immediately can help reduce challenging behavior.” |

To convey quickly and clearly what should be done; to help the reader quickly remember and act on the information. |

| 2. | Keep lists short and avoid rotating topics | Stick to one idea at a time and be sure it is fully covered (Catagnus et al., 2020). It is best to complete a whole idea rather than skipping between topics. This way, the reader does not need to piece together information from different sections. In addition, if you are listing items, this should be a short list with no more than three to seven bulleted items and should use an active voice (CDC, 2009). This is important because literacy deficits can affect one’s ability to recall information from long lists (CDC, 2009). If you have more information to list, it should be broken up with subheadings. |

Example: 1. Tell Zander to do the writing task. 2. Point to the crayons and help him complete the task if needed. 3. Once his writing is done, smile and reward him with the coloring book. Nonexample: 1. Join Zander at the table and instruct him to write in his book. 2. Check on Zander’s math sheet after lunch. Don’t check every problem on the worksheet, just pick a few. But first have him finish writing. 3. When writing in the book, point to the crayon that you think Zander may want. This will work as a prompt to get him started. 4. Before moving on to lunch, make sure Zander finishes his writing. When he completes his writing, provide descriptive praise and access to the coloring book. Next have lunch and check his math work. |

To build understanding of the topic without distraction by limiting the amount of information given at a time. |

| 3. | Use simple language | Communicate in simple, conversational language as if you were talking to a friend (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008). You should also avoid passive statements and stick to the point. When giving directions, be sure to focus on what to do rather than what not to do (CDC, 2009). This will help you focus on the positive and keep your reader engaged. When information points out a person’s undesired behavior, they are less likely to act on it so information for parents and stakeholders should focus on staying proactive. Remember to be respectful, use an encouraging tone, and focus on small practical steps (Catagnus et al., 2020). |

Example: 1.“You can show him which item to pick by pointing to the right picture.” 2. “Follow through with your first instruction by pointing to the right picture and waiting for him to copy.” Nonexample: 1. “Physical prompts can be added to facilitate correct responding.” 2. “Do not move on to different instructions if he does not respond to your first instruction; instead, add a prompt.” |

To help the reader feel comfortable with instructions and support buy-in while clearly communicating. |

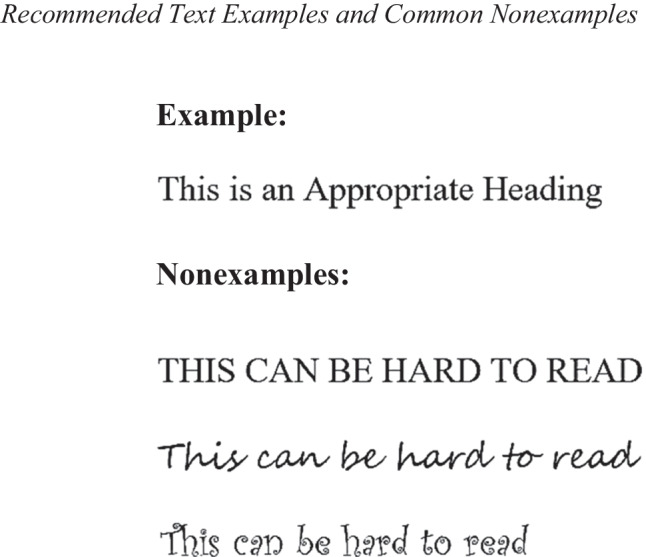

| 4. | Use large clear fonts | Font sizes between 12 and 14 pts are easiest to read, whereas smaller fonts can be challenging for some readers (CDC, 2009). Section headings should be at least 2 pts higher than the body font and should avoid using all caps. Texts written in upper- and lowercase lettering are easier to read. Also, underlining, italics, and light text on dark backgrounds should be minimized as they reduce readability. Finally, be sure to stick with clear fonts that have distinct letters that are easy to read (Catagnus et al., 2020), rather than fancy, childish, or script fonts. See Figure 1 for examples. |

Example: “Point to the faucet and wait for your child to copy you.” Nonexample: “Point to the faucet and wait for your child to copy you.” |

To increase legibility and facilitate understanding. |

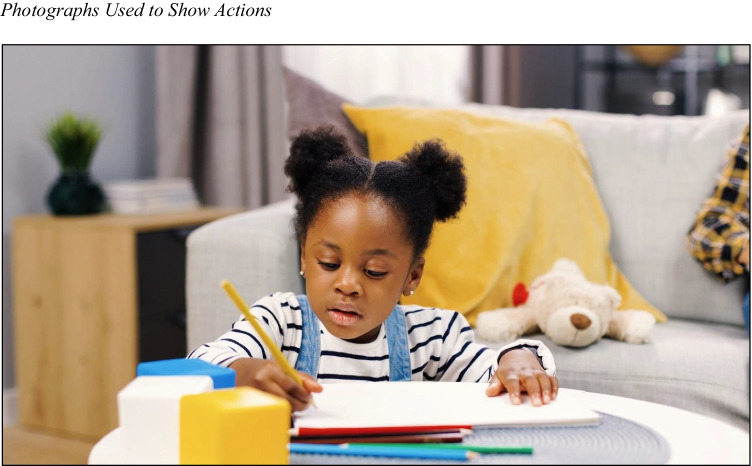

| 5. | Use visuals that show actions |

Visuals can improve communication when used correctly (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). As a rule, photographs of actions are most effective for showing events, emotions, and people. They can quickly gain the reader’s attention and tell a story (CDC, 2009). This works best when they are appropriately cropped, in focus, and do not feature distracting backgrounds (see example in Figure 2). Images should be screened by a representative audience to be sure they convey the intended behavior, such as actions like asking, prompting, reaching, and other postures that can be interpreted differently in a single snapshot. When photographs are not available, a clear illustration can be used to show a simple procedure like folding a towel. Illustrations should be simple drawings that avoid unnecessary detail (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Finally, visuals intended to decorate should be avoided so that visuals are carefully selected and only displayed to clarify the text (CDC, 2009). |

Example: Including a photograph for meal preparation featuring a grandparent helping a child eat with additional family members seated at the dinner table; to be used with an Indian American family in Houston, Texas living in a multigenerational home. Nonexample: Including a photograph for meal preparation featuring images from a popular commercial depicting several Indian American children dancing around a banquette table, to be used to be used with an Indian American family in Houston, Texas, living in a multi-generational home. |

To model behaviors that are acceptable to the reader and clear enough to be imitated. |

| 6. | Use short captions with images | When using visuals, you should present one message per visual and label visuals with short captions (CDC, 2009). The text should be near the visual, help explain the action, and use a tone and content that reflect the values and beliefs of the target culture (Singelis et al., 2018). Captions are most effective when written in complete sentences,using sticky language (catchy or memorable) and including the key message (Catagnus et al., 2020). Remember to use visuals and captions that show the reader what to do, rather than what not to do (CDC, 2009). |

Example: 1.Accompanying and image with the caption, “Give a bigger reward for great behavior or a smaller reward for good behavior.” 2. Accompanying and image with the caption, “Give more attention for good behavior and less attention for bad behavior.” Nonexample: 1. Accompanying and image with the caption, “Don’t Reinforce!” 2. Accompanying and image with the caption, “It is important to reward target good behaviors that you want to see more of while ignoring the challenging behaviors that cause problems in your home. This way your child’s behavior will improve in ways that are important to your family. |

To support fluency by the reader by making it quick and easy to understand and respond to the information. |

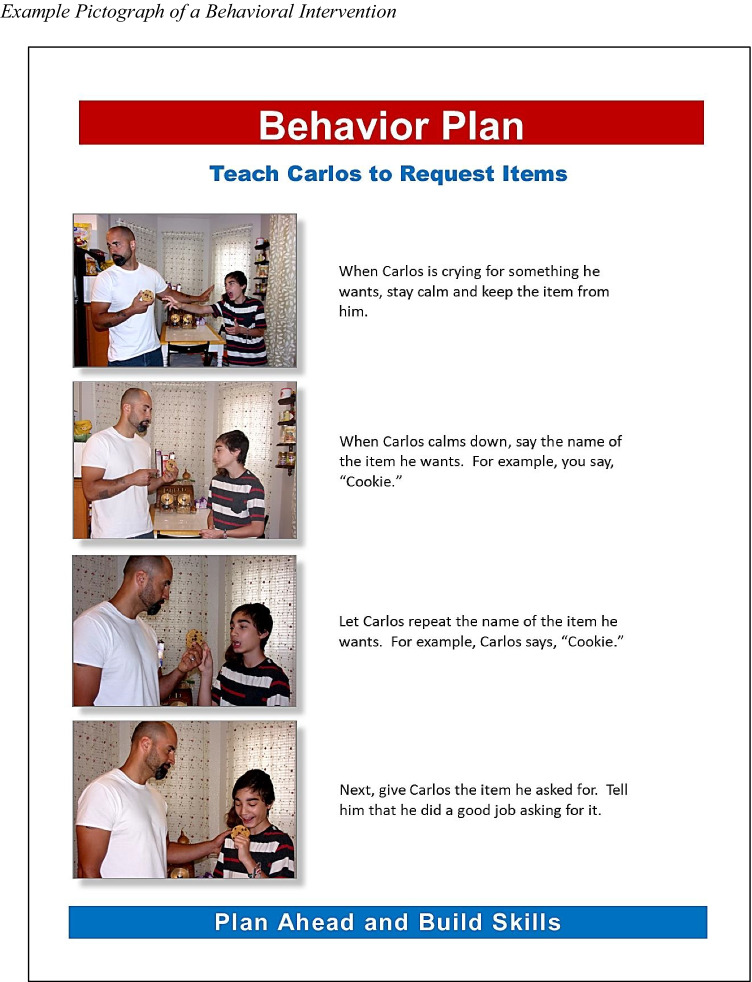

| 7. | Use pictographs | Pictographs use picture sequences to quickly convey information and be memorable to audiences (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). They are best used to show specific actions, such as how medication is taken or how to complete a simple procedure (CDC, 2009; Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Pictographs can be incorporated into BIPS when teaching parents how to follow simple behavioral strategies (see example in Figure 3), to quickly help parents understand a sequence of actions (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001), and can be combined with other recommendations for easy-to-read materials, including (1) well-focused, timed, and cropped action photographs (CDC, 2009); (2) limited messages per document (Catagnus et al., 2020); and (3) text and captions written in complete sentences and focused on telling the reader what to do (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). |

Example: Including a pictograph for washing laundry featuring images (1) of a mother helping a child place items in a washing machine; (2) pouring detergent into a measuring cup; (3) pouring the cup of detergent into the washer; and (4) setting the knob to the “Regular Wash” setting. All images appear to feature the same models. Nonexample: Including a pictograph for washing laundry featuring images of (1) a child tugging on their shirt; (2) an elderly man reaching into a washing machine; and (3) a mother holding up a shirt while smiling at a teenager. |

To show a behavior chain in short simple steps allowing the reader to perform relatively more complex behavior. |

It may be beneficial to use the guidelines in this section to create a BIP template that can be used with a wide variety of images and strategies. This would allow practitioners to readily create a basic BIP strategy that can then be adapted to each family. See Figure 3 for an example.

Table 5.

Guidelines for Applying Cultural Adaptations to BIPs

| Step | Description | Example / Nonexample | Social Validity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Include culturally appropriate images | Visuals should be familiar to your audience and avoid items and symbols that would not be easily understood (CDC, 2009; Nierkens et al., 2013; Osmar & Webb, 2015; Singelis et al., 2018). If the client has physical challenges, such as medically necessary equipment or support, this can be included in visuals to help the reader relate to the image. Be sure that all components of the image such as skin tone, facial features, clothing style, food or other items, and background scenes are culturally appropriate to your target audience (Nierkens et al., 2013; Singelis et al., 2018). Photographed people should portray interactions that are in line with cultural norms (Singelis et al., 2018). Each scene depends on the unique culture of the target family and be specific all the way down to the type of food on the table (Houts et al., 2006; Resnicow et al., 1999). |

Example: Including a photograph for meal preparation featuring a Chinese American family dressed in casual Southern California style clothing seated at the dinner table, to be used with a Chinese American family in Los Angeles, living in a multigenerational home similar to the image and wearing clothing similar to the image. Nonexample: Including a photograph for meal preparation featuring images from a thematic Broadway play depicting several Chinese children in embroidered costumes on a set with golden embellishments hanging in the background; to be used to be used with a Chinese-American family in Los Angeles, California. |

To be relatable to the reader in order to facilitate comprehension and buy-in. |

| 2. | Avoid stereotypes | It is important to avoid stereotypes and derogatory images when selecting CS visuals (Singelis et al., 2018). For example, including a photograph of a child of the matching ethnicity but located in an impoverished or inappropriate background environment could be considered offensive. In some cases, with consent it may be best to create photographs of the client and parent performing the actions of interest for use in the individualized behavioral documents. When visuals are needed to represent diverse audiences, photographs should feature a variety of ages, ethnicities, and racial groups (CDC, 2009). |

Example: Including a photograph featuring a Black woman and child wearing jeans and short-sleeve shirts, to be used for a Black child and his mother who live in San Antonio, Texas. Nonexample: Including images from a country music video depicting a Black man with a cowboy hat, to be used for a Black child and his mother who live in San Antonio, Texas. |

To maintain cultural humility, by approaching each interaction with consideration and respect; to contributing to the reader’s comprehension and buy-in. |

| 3. | Operationalize cultural themes | Before attempting to adapt text, operationalize cultural themes that will be included in the materials—these are the themes or domains that you identified during information gathering. This will allow text to be easily and reliably adapted. For example, some cultural themes that can affect diverse families with children with ASD are locus of control (Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016), acceptability of using behavioral interventions (Burkett et al., 2015), parental role and responsibility (Liao et al., 2018; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016), and support systems (Goedeke et al., 2019; Gona et al., 2020). Cultural agreement within each of these domains can occur across a spectrum so materials may need to be adapted to best reflect individual beliefs in each domain, e.g.. external locus or internal locus, high to low acceptability, high to low feelings of responsibility for child behavior change, and high to low levels of support from family and friends. When attempting to operationalize a cultural domain, it should be clearly explained, include a guideline of how to adapt, and include examples and nonexamples. This will help to consistently adapt phrasing. Consider these operationalization examples of locus of control. |

Example: External Locus of Control: This a person’s perception of the determining factors for attaining reinforcers, or other outcomes, being widely attributed to external causes (Rotter, 1966). For example, a person may consider a reinforcer to be delivered in part due to an outside force such as chance, fate, luck, or other higher power. When events are interpreted as being heavily controlled by an outside source, this is referred to as external locus. When incorporating external locus, embed themes of outside sources of behavior change (such as parent support). Example: “You can practice these steps many times to teach your child to stay engaged.” Nonexample: “These steps can be practiced many times so your child learns to stay engaged.” Nonexample: External Locus of Control: When incorporating external locus, embed themes of outside sources of behavior change (such as parent support). For example, write, “help him learn.” |

To be relatable to the reader in order to facilitate understanding and buy-in. |

| 4. | Embed lay terms and cultural themes | Once you have a list of protocol steps and operationalized cultural themes, adapt your recommendations to better align with cultural themes, being careful not to reduce the preciseness of the procedures. When simplifying procedures, conversational language should be chosen over technical language (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008; Neuman, 2018). For example, when using technical language, it would be appropriate to say, “reinforce the behavior.” When using conversational language, it would be appropriate to say, “reward the child.” Notice that these are conceptually different messages, yet both specify the delivery of a desired item after a behavior. When the goal of intervention materials is to quickly change parent behavior, it is important to choose phrases that the parent is likely to quickly understand and respond to—remember, additional education on behavioral principles can always be taught at a later date (Neuman, 2018). The statements chosen should be clear, concise and reflect the client’s cultural beliefs. When intermixing precise, technological, and conversational language, it is important not to confuse word meanings because this breach of logic could contribute to added confusion (Neuman, 2018). |

Example: 1. “Reward the child.” 2. “Give a reward after he completes the task.” 3. “Reinforce this behavior so that he does it more in the future” (for readers with some behavioral training). Nonexample: 1. “Reward the behavior” (breach of logic). 2. “Reinforce the child” (breach of logic). 3. “Deliver reinforcers for compliance. (jargon and technical language). |

To increase comprehension and maintain precise instructions that are likely to be followed. |

It may be beneficial to use the guidelines in this section to create pictographs of common strategies for use by clients of various ethnic backgrounds. This would allow practitioners to readily create a basic BIP strategy that can then be adapted to each family.

Cultural Sensitivity in Health Materials

CS in health materials can be understood in terms of surface structure and deep structure (Resnicow et al., 1999). Surface structure in health materials involves visual agreement (such as in images) with the cultural group, such as common facial features, clothing, and other environmental arrangements. People in visuals should be of the same ethnic and cultural background as the representative audience whenever possible, including skin tone, age, gender, clothing style, actions, and relevant environments (Resnicow et al., 1999; Singelis et al., 2018). Ethnicity and culture are not the same constructs so practitioners should be careful to accurately represent their intended audience. For example, a photograph of an Indian American child doing homework in his suburban home in San Diego, California, would likely have vastly different clothing and background scenes than a photograph of a child participating in a cultural event in India. Although both images may include a child of Indian descent, the surface structure of each would likely be appropriate for some families and not others. Surface structure adaptations require all elements of embedded images to be culturally appropriate to the target population (Resnicow et al., 1999; Singelis et al., 2018). In addition, if the client has physical challenges, such as medically necessary equipment or support, this can be included in visuals to help the reader relate to the image (CDC, 2009).

When adapting surface structure, practitioners should be sure that all components of the image are culturally appropriate to the target audience (Nierkens et al., 2013; Singelis et al., 2018). Photographed people should portray interactions that are in line with cultural norms (Singelis et al., 2018). Each scene depends on the unique culture of the target family and should be specific all the way down to the type of food on the table (Houts et al., 2006; Resnicow et al., 1999). It is important to avoid stereotypes and derogatory images when selecting CS visuals (Singelis et al., 2018). For example, including a photograph of a child of the matching ethnicity but located in an impoverished or inappropriate background environment could be considered offensive. In some cases, with consent it may be best to create photographs of the client and parent performing the actions of interest for use in the individualized behavioral documents. When visuals are needed to represent multicultural audiences, photographs could even feature a variety of ages, ethnicities, and racial groups (CDC, 2009). We have included examples and nonexamples of adapting surface structure in images in Table 5.

Deep structure incorporates sociocultural values into the materials, often through text (Resnicow et al., 1999). This can include themes such as religiosity and family support, much like Leeman et al. (2008) noted for older Black American women in rural areas, and can even include using a tone relevant to the targeted culture (Resnicow et al., 1999; Singelis et al., 2018). For example, authoritative directions may be accepted by some people of a given culture but feel oppressive or unrelatable to people of another culture (Resnicow et al., 1999; Singelis et al., 2018). Having a thorough understanding of the target culture is important for adapting deep structure to be aligned with family values, spiritual beliefs, and acceptable practices that are incorporated into the culture’s verbal behavior (Brodhead et al., 2014). In one study, when evaluating standard versus culturally sensitive oral health materials with Mexican American mothers, a deep structure adaptation that Singelis et al. (2018) added was a warm friendly tone to reflect simpatía. In contrast, standard materials reflected an authoritative, direct tone not intended to reflect any given culture or ethnic group, a practice that instead may reflect the culture of the author.

Before attempting to adapt text, it is important to operationalize cultural themes that will be included in the materials—these are the themes or domains that you identified during information gathering. This operationalization will allow text to be easily and reliably adapted. For example, some cultural themes that can affect non-white families of autistic children include locus of control (Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016), acceptability of using behavioral interventions (Burkett et al., 2015), parental role and responsibility (Liao et al., 2018; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016), and support systems (Goedeke et al., 2019; Gona et al., 2020). Cultural agreement within each of these domains can occur across a spectrum so materials may need to be adapted to best reflect individual beliefs in each domain (e.g., external locus or internal locus, high to low acceptability, high to low feelings of responsibility for child behavior change, and high to low levels of support from family and friends). When attempting to operationalize a cultural domain, it should be clearly explained, include a guideline of how to adapt, and include examples and nonexamples. This will help to consistently adapt phrasing. Table 5 includes examples and nonexamples of operationalizing cultural themes.

When adapting deep structure, not only should the meaning of text be culturally representative but also presented in the first language of the receivers (linguistically competent; Singelis et al., 2018) and adapted for cultural and linguistic diversity (Brodhead et al., 2014). Motivation and rewards described in text should be meaningful to the targeted demographic and specifically to the target family (Singelis et al., 2018). This is important because rewards like closeness and strong family bonds may be more valued to some populations although individual independence would be more important to others. Including one of these goals rather than the other could greatly affect the motivation of participants depending on cultural values. Adapting phrases and word choice to suit cultural and linguistic diversity can include using appropriate colloquial and conversational language. This can be done by embedding culturally appropriate lay terms and explanations. For example, after creating a list of protocol steps and operationalizing cultural themes, practitioners can adapt phrasing of their recommendations to better align with those themes, being careful not to reduce the preciseness of the procedures. To start, when writing intervention procedures, conversational language should be chosen over technical language (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008; Neuman, 2018). For example, when using technical language, it would be appropriate to say, “reinforce the behavior.” When using conversational language, it would be appropriate to say, “reward your child.” Notice that these are conceptually different messages, yet both specify the delivery of a desired item after a behavior. When the goal of intervention materials is to quickly change parent behavior, it is important to choose phrases that the parent is likely to quickly understand and respond to—remember, additional education on behavioral principles can always be taught at a later date (Brodhead et al., 2014; Neuman, 2018). The statements chosen should be clear, concise, and reflect the client’s cultural beliefs. When intermixing precise, technological, and conversational language, it is important not to confuse word meanings because this breach of logic could contribute to added confusion (Neuman, 2018).

Outcomes of Culturally Sensitive Health Materials

When the surface and deep structure of health materials reflect appropriate cultural adaptations, clients prefer the CS training to standard training and perform better (Singelis et al., 2018). For example, in one study on oral health information for Spanish-speaking mothers of Mexican heritage, Singelis et al. (2018) incorporated themes such as familismo and marianismo, as well as the roles and responsibilities of Mexican mothers through the surface structure with images of Latina mothers and children and by embedding messaging to reflect cultural beliefs and values in deep structure. The participants were asked to read either culturally adapted, standardized, or intermixed child oral health materials and to complete pre- and posttests on embedded information. Through a 2x2 factorial group design, researchers found that deep structure, surface structure, and combinations of these each resulted in better parent outcomes than standard materials alone. Increased recall and understanding of the materials were displayed through comparison of pre- and posttest results on exams, and participants reported a preference for culturally adapted materials. Such health information research uses randomized control trials (Bernal & Adames, 2017) surveys, pre/posttest, and statistical analysis (Coard et al., 2004; Kline et al., 2016; Nierkens et al., 2013), and shows how culturally adapted materials can affect preference and understanding of informational content. Further, adaptations of surface structure and deep structure such as these are commonly used when developing CS materials in health interventions (Barrera et al., 2013; Rathod et al., 2018). Behavior analysts should further evaluate the cultural adaptation of surface and deep structure in CS intervention materials to assist in the development of guidelines for creating CS behavior analytic intervention materials.

CS is also a key component to social validity. Social validity is a qualitative appraisal of the extent that an intervention focuses on goals that are significant to clients and interested parties, uses procedures that are acceptable and appropriate, and has outcomes that are important to society (Halbur et al., 2020). As the practitioner learns more about the culture of the client, they will be able to better predict whether an identified behavior is one that should be targeted and whether changing this behavior would likely make a difference in the person’s life. Social validity considerations related to the recommendations in this tutorial have also been included in Tables 3, and 5. When creating protocols and materials, CS interventions should incorporate preferences including intervention delivery, settings and modalities (Di Noia et al., 2013). Carefully constructing intervention materials to include preferred culturally appropriate content would be an important step toward increasing the social validity of materials. In addition, although preference does not necessarily indicate that performance of protocols will be improved by those administering the intervention, it may increase participant buy-in and reduce attrition (Moore & Symons, 2011; Raulston et al., 2019).

As a field, behavior analysts need to be driven toward cultural competence and culturally appropriate behavioral recommendations (BACB, 2014; Fong & Tanaka, 2013). We are also mandated to uphold the attitudes of science in recommending evidence-based procedures. In the area of using written intervention materials with novice individuals, the research on efficacy and best practice is extremely limited (Quigley et al., 2018). This has led practitioners to create materials based on longstanding content recommendations, rather than individualized application (Quigley et al., 2018). Although research shows that cultural adaptations in health materials can improve health behaviors (Kumpfer et al., 2017), the research on guidelines for best practice and effective components of BIPs would benefit from additional investigation through repeated measures and single-subject designs by behavior analysts. This calls for advances in behavior-analytic research on the enhancement of behavior intervention documents, cultural adaptation of materials, and guidelines for practitioners.

Comprehensibility in Health Materials

Comprehensibility refers to the extent that information can be easily understood. Written information can be made more comprehensible, leading to increased learning (Catagnus et al., 2020; Giebenhain & O’Dell, 1984; Kuhn et al., 1995; Osmar & Webb, 2015). Written intervention plans often fail to produce high quality performance in implementers (Dogan et al., 2017; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012); however, making behavioral intervention materials more comprehensible has been shown to increase treatment fidelity (Danforth, 2000; Jarmolowicz et al., 2008; Kuhn et al., 1995). Application of consistent guidelines for adapting materials is needed to increase this skill for behavioral practitioners, and to subsequently increase treatment integrity and social validity.

An argument can be made that behavior analysts are trained within a scientist-practitioner model and BIPs are a reflection of practitioner culture. We are part of a culture of science and without dissemination guidelines we could be imposing our culturally maintained linguistic values on our audiences through our BIPs. In this way, comprehensibility may also be thought of as a cultural variant and may explain behavior analytic practitioners’ preference for technical jargon over lay terms (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008). Although it may be challenging to step outside of our preferred vernacular, one way that behavior analysts could begin to systematically increase the comprehensibility of written behavioral intervention materials is to follow the FACT Model (Catagnus et al., 2020). FACT stands for Fluency, Amount to process, Coherence, and Time (Catagnus et al., 2020). These are comprehensibility indicators that are commonly recommended in health communication materials (e.g., CDC, 2009). We review these tools below, and have included a complete comparison of comprehensibility indicators, guidelines, and examples in Table 2.

Table 2.

Broad Comprehensibility Recommendations

| Indicator | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Fluency | Short Captions | Present one message per visual using short captions. Each caption should be near the visual and help explain the visuals in a tone appropriate to the readers. They should tell the reader what to do, instead of what not to do. |

| Headings as Cues | Headings should include whole statements to convey ideas rather than just a couple words. This lets headings communicate more. | |

| Readable Text | Use clear, nonfancy text in at least 12-pt sized font. Avoid italics and all caps as these can be hard to read. Headings should be at least 14-pt sized font. | |

| Pictographs | Pictographs are picture sequences that can be used to show a series of actions. They can quickly explain procedures and be memorable to the reader. Be sure to limit sequences to seven steps or fewer. | |

| Amount | White Space | Keep 10%–30% white space, including ½- to 1-in margins to keep the document clutter-free and easy to read. Cramming too much on the page can be overwhelming for readers. |

| Short messages | Give the most important information first and limit information to no more than three to four main messages per document and lists with three to seven bulleted items. | |

| Coherence | Images of People | Including people in images works best when people are of the same ethnic and cultural background as your reader, including skin tone, activities, clothing, and backgrounds. |

| Images That Show Actions | Photographs of actions are often most effective when used to show people engaging in activities and emotions. They can quickly gain attention while telling a story. Images work best when backgrounds are not distracting and pictures are focused and cropped. | |

| Familiar Language | Communicate in simple, conversational language as if you were talking to a friend. Use language that matches the readers’ values and beliefs. | |

| Timing | One Idea Per Page | Presenting one idea per page can help with conveying a cohesive message and aids recall. Having to turn the page in the middle can lead the reader to forget the beginning of the message. |

The table reflects recommendations for comprehensibility based on CDC guidelines (2009), Jarmolowicz et al. (2008), and the FACT Model recommended by Catagnus et al. (2020). Notice that this categorization is one way to align recommendations, however, these guidelines are not mutually exclusive and could satisfy multiple categories. For example, including people in images and images with actions could satisfy both fluency and coherence; keeping one topic per page could satisfy amount and timing, and including short captions could satisfy both fluency and coherence.

Fluency

Fluency describes the ease of processing text and images. Clear, familiar, and highly contrasted images are easier to process and are more understandable. When used in health communication materials (HCM) such as cancer pamphlets (Butow et al., 1998) and radiation therapy booklets (Osmar & Webb, 2015), fluency strategies, such as incorporating clear, high-quality images (see Figure 2 for an example) improves health behaviors and is supported by communication theory (Butow et al., 1998; Osmar & Webb, 2015; Singelis et al., 2018). Visuals can improve communication when used correctly (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). Photographs of actions are usually most effective for showing events, emotions, and people. They can quickly gain the reader’s attention and tell a story (CDC, 2009). This works best when they are appropriately cropped, in focus, and do not feature distracting backgrounds (see example in Figure 2). Images should be screened by a representative audience to be sure they convey the intended behavior, such as actions like asking, prompting, reaching, and other postures that can be interpreted differently in a single snapshot. When photographs are not available, a clear illustration can be used to show a simple procedure like folding a towel. Illustrations should be simple drawings that avoid unnecessary detail (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Finally, visuals intended to decorate should be avoided so that visuals are carefully selected and only displayed to clarify the text (CDC, 2009).

Fig. 2.

Photographs Used to Show Actions. Note. Example photograph of a young girl coloring independently. Stock photo used with permission by M_Agency/Shutterstock.com

Another way to improve fluency in comprehensibility is through incorporation of pictographs. Pictographs are picture sequences that represent words or ideas. They can quickly convey information and be memorable to audiences (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Pictographs are best used to show specific actions, such as how medication is taken or how to complete a simple procedure (CDC, 2009; Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001) such as a breast health instruction document for Latina women with limited literacy (Choi, 2012). In one study by Houts et al. (2001), pictographs were used to teach 21 adults with limited literacy 236 medical instructions. Participants showed an 85% mean recall across 4 weeks, suggesting the strong impact of pictographs on memory.

Pictographs may also be an effective tool for teaching parents how to follow simple behavioral strategies (see Figure 3), because they can quickly help the reader understand a sequence of actions (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Although currently available research on pictographs is promising, pictograph research needs to be extended to behavior analytic intervention materials, such as BIPs to establish the link between recall, efficacy, and adherence (Choi, 2012; Houts et al., 2001). Table 4 gives additional information and examples for using pictographs in BIPs.

Fig. 3.

Example Pictograph of a Behavioral Intervention. Note. Example of a pictograph used to teach manding prompt procedures to parents

Another contributor to fluency is easy-to-read text (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). Font sizes between 12 and 14 pts are easiest to read, whereas smaller fonts can be challenging for some readers (CDC, 2009). Section headings should be at least 2 pts higher than the body font and should avoid using all caps. Texts written in upper- and lowercase lettering are easier to read. Also, underlining, italics, and light text on dark backgrounds should be minimized because they reduce readability. Finally, it is best to use clear fonts that have distinct letters that are easy to read (Catagnus et al., 2020), rather than fancy, childish, or script fonts. See Figure 1 for examples and nonexamples.

Fig. 1.

Recommended Text Examples and Common Nonexamples. The example is in Times New Roman. Nonexamples include all capital letters, script fonts, and fancy fonts

Amount

The amount to process involves the amount of information that a person can consider at one time (Catagnus et al., 2020). Large quantities of complex information can lead a person to feel confused or overwhelmed. However, focused, familiar information can lead to increased understanding (see Table 2 for examples). Some ways to control the amount of information given are to limit the number of bullets in lists, refrain from carrying a single topic across multiple pages, and refrain from mixing topics on a single page (CDC, 2009). When practitioners create materials, it is best to stick to one idea at a time and be sure it is fully covered to complete a whole idea rather than skipping between topics (Catagnus et al., 2020). In this way, the reader does not need to piece together information from different sections. In addition, when listing items, no more than three to seven bulleted items should be used and information should be presented in an active voice (CDC, 2009). Short lists are important because literacy deficits can affect one’s ability to recall information from long lists (CDC, 2009).

According to the U.S. Department of Education (2003), only about 12% of consumers have proficient health literacy skills. Factors related to below basic health literacy include primary language differences, ethnicity, education level, and disabilities. This means that practitioners should adapt health information materials for upwards of 9 out of 10 recipients to overcome barriers that reduce meaningful access to effective treatment. Adaptations may enhance the ability to locate providers, complete forms, share personal information, manage illness, and perform health interventions (CDC, 2009). When creating easy-to-read documents, practitioners should give the most important information first and limit information to no more than three to four main messages per document (Catagnus et al., 2020; CDC, 2009). This should focus on what the reader needs to do or know, rather than what is nice to know. Remember that the point of the document is to change behavior, knowledge, or beliefs so writing must stay clear, appropriate, and to the point. This should tell the reader what actions they should take in a concise manner.

Adaptation is vital considering that it is well-documented that an inability to understand information and follow directions through text or spoken communication inhibits participation in medical and educational interventions (Butow et al., 1998; Miller, 2013; Moss & Puma, 1995; Osmar & Webb, 2015). For some, being able to gain information through language that is easy to say and read also contributes to visual fluency and can be important for accessing health information (Catagnus et al., 2020). Guidelines for using clear and understandable pictures and text were published by the CDC in their book Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy-to-understand Materials (2009) and include fluency strategies such as recommendations for font size, style, and placement, sentence structure and length, image type and usage, and visual layout of materials. These recommendations are supported by HCM research (National Cancer Institute, 2004) and could be used to enhance behavioral materials.

Coherence

Connecting information to existing knowledge is regarded as coherence. This allows people to build on their current understanding and can aid in building more complex frames of thought (Catagnus et al., 2020). Using familiar images and phrases that relate to culturally relevant people and actions could help readers connect information to their own experiences. Culturally adapting materials to match the readers’ values and beliefs may be a good strategy to use coherence to strengthen parent understanding and performance. In one study on oral hygiene health materials for Mexican heritage mothers, Singelis et al. (2018) compared culturally adapted pamphlets to standard materials and found that recall, understanding, and performance on a posttest quiz were better for parents who received the culturally sensitive pamphlets. Communication theory suggests that these cultural adaptations may have resulted in improved coherence (Singelis et al., 2018). Practitioners should communicate in simple, conversational language as if talking to a friend (Jarmolowicz et al., 2008). This can contribute to coherence when explanations use concepts that are familiar to the client. When giving directions, it is best to focus on what to do rather than what not to do (CDC, 2009), focusing on the positive and keeping the reader engaged. Using a respectful, encouraging tone and focusing on small practical steps that make sense to the client are important for establishing coherence and overall comprehensibility of documents (Catagnus et al., 2020).

Time

Finally, having time to process information is also important for learning (Catagnus et al., 2020). This can include spacing out training to give time to strengthen understanding of each concept before adding new concepts. When information will need to be processed for longer durations, visuals can facilitate processing (Catagnus et al., 2020). Therefore, separating training topics in parent training materials and providing breaks between topics would be a good idea to allow parents time to process strategies they have learned before moving on to new content. In addition, using a pictograph (see Figure 3) to explain a behavioral strategy with a number of steps can be a good way to give thorough information in a digestible amount and in a relatively short amount of time. We have included a concise breakdown of comprehensibility recommendations and indicators in Table 2. In addition, we elaborate how comprehensibility adaptations can be applied to BIPs in Table 4.

Although research suggests that making intervention documents more comprehensible can improve implementer performance (Danforth, 2000; Jarmolowicz et al., 2008; Kuhn et al., 1995), research in this area is extremely limited. Behavior analysts should investigate the controlling variables behind effective behavior intervention documents and create guidelines for building materials that are appropriately adapted to work with the targeted reader (Quigley et al., 2018). Additional research on creating easy-to-read intervention plans that lead to increased fidelity of implementation will help practitioners learn how and when to adapt materials to be appropriately comprehensible for caregivers, teachers, and other entry-level individuals.

Adapting BIPs for Parents of Autistic Children

One population that would likely benefit from empirical adaptation of intervention materials is parents of autistic children. More than ever, practitioners working with autistic children are serving clients from nonmajority, marginalized, and minoritized backgrounds. Health disparities within these populations are clear because autistic children have historically been disproportionately identified in white communities of higher socioeconomic status (SES) compared to those of Latine, Black, and other minoritized and marginalized people (Christensen et al., 2018). Despite this, children of non-white backgrounds are increasingly diagnosed with ASD and thus are increasingly seeking behavior analytic services (Department of Health and Human Services, 1999; Liao et al., 2018). Although participant demographics have been underreported in behavior analytic research (Jones et al., 2020), behavior analysts are tasked with competent provision of services to clients of all ethnic, racial, regional, gender, and other cultural backgrounds (BACB, 2014; Liao et al., 2018). This requires approaching disparities in values, beliefs, and practices with cultural humility (Foronda et al., 2016). In addition, parent performance is a driver of child progress in behavior analytic treatments, yet parents of autistic children are often expected to perform strategies with minimal training (Allen & Warzak, 2000). Due to the high need of this population, the cultural adaptation of parent training materials for parents of autistic children will be used as an example application throughout the tutorial section.

High quality parent performance of behavioral strategies can be hard to achieve without intensive parent training (Dogan et al., 2017; Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012), yet despite the possible positive outcomes of intensive parent training programs, parent performance and adherence to intervention protocols is often reduced in service delivery (Allen & Warzak, 2000; Raulston et al., 2019), reflecting a research to practice gap. Some research showed that parent attrition from behavioral training programs was as high as 50% (Raulston et al., 2019), yet other studies suggest that parental nonadherence to behavioral interventions for autistic children may be around 24% (Moore & Symons, 2011). Moreover, parental nonadherence and attrition could reflect lack of needed cultural adaptation in behavior interventions (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016; Allen & Warzak, 2000; Barrera et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2020).

To better understand the challenges with parent training, Raulston et al. (2019) interviewed seven focus groups comprised of 26 mothers and 4 fathers of autistic children of various backgrounds. Parents reported enablers and barriers to behavioral parent training that formed three major themes: “(a) individualized and supportive professional feedback; (b) accessible, flexible, and affordable training; and (c) social-emotional support and connection to community” (Raulston et al., 2019, p 696). In another investigation on parent attrition from behavior training programs, parents reported dropping out of training due to the perception that the interventions were not acceptable for the child in family and community life (Moore & Symons, 2011), which could reflect a cultural mismatch (Rathod et al., 2018). Other contributing factors that parents reported included perceptions that the intervention was not effective at changing behavior, and beliefs that following strategies would not produce meaningful outcomes (Moore & Symons, 2011). These may all be indicators pointing to a need for more culturally appropriate behavioral recommendations.

Although some research has examined using simplified methods of communicating behavioral strategies to parents (Danforth, 2000; Kuhn et al., 1995), behavior analysts would benefit from evidence-based guidelines for creating effective CS behavior intervention materials. This should be in conjunction with best practices for affirming social validity, preferred modality, and cultural competence.

General BIP Adaptation Process

Health communication research (Alizadeh & Chavan, 2016; Barrera et al., 2013; Resnicow et al., 1999) and recommendations from the CDC (2009) provide some guidelines that practitioners can use to incorporate CS into BIP materials. Because there are many different ways to culturally adapt materials and no single agreed upon method (Bernal & Adames, 2017; Rathod et al., 2018), it may be better to follow largely agreed upon processes such as adapting surface and deep structure (Resnicow et al., 1999) as a means of cultural targeting or cultural tailoring, and following common steps to test and refine CS BIP materials (Barrera et al., 2013).

A review by Barrera et al. (2013) found that there is general agreement that the five stages of cultural adaptation can be organized to include: “information gathering, preliminary design, preliminary testing, refinement, and final trial” (p. 196). Using Barrera’s five stages of cultural adaptation can be a strong example of using cultural competence by a behavior analyst and can be used as a general BIP adaptation process. The steps of this process are described in Table 3 along with examples and nonexamples in order to better illustrate how this can be used to develop culturally appropriate BIPs. To start, practitioners should use cultural awareness to identify their own biases related to the target population and problem. They should take a nonjudgmental approach (i.e., not assuming that differences are linked to deficient or otherwise negative characteristics in others) at increasing cultural knowledge through information gathering and preliminary design of the BIP.

Designing BIP materials should include embedded adaptations of surface and deep structure based on information gathered. Practitioners should start by creating comprehensible empirical interventions based on the function and topography of the behavior, environmental constraints, and client preferences. Next, the evidence-based procedures should be adapted to represent the cultural beliefs and values of the client, while maintaining the core content and procedural integrity of the prescribed protocols. We have included recommendations for adapting surface structure and deep structure of BIPs in Table 5. It is important not to diminish the preciseness of the procedures when culturally adapting protocols as this would weaken the empiricism and likely efficacy of the intervention (Bernal & Adames, 2017). When creating preliminary BIP designs, it is best to use subject matter experts, representative focus groups, questionnaires and/or surveys about your materials (Barrera et al., 2013).

Practitioners should next embark on preliminary testing from a stance of cultural humility. Cultural humility is an ongoing process of self-assessment, -exploration, and -critique when engaging with others, and the simultaneous learning and honoring of values, beliefs, and practices important to others’ customs (Stubbe, 2020). This can include piloting BIP materials with a small sample of representative participants and taking data on qualitative and quantitative dimensions (Barrera et al., 2013). Qualitative BIP dimensions could include things like ease of application of strategies, challenges with content or recommended activities, the extent to which the materials helped solve the behavioral problem, preference for these BIP materials compared to other BIPs, overall satisfaction with the behavioral program, and acceptability of the interventions. It would be advisable to ask about the acceptability of cost, time requirements, flexibility, whether the BIP training felt supportive and professional (Raulston et al., 2019), goodness-of-fit for the family and community, whether parents think the interventions will work, and whether parents think they can perform the interventions (Moore & Symons, 2011). Quantitative measures could include data on parent fidelity of using the materials compared to standard BIP materials (Barrera et al., 2013) such as through measures of percentage of BIP steps performed correctly, trials to criterion; or other quantitative analysis of efficacy, maintenance and generalization.

Practitioners should use cultural skills to refine BIP materials based on feedback received and begin the final trial with the target population. When you are ready to conduct your final trial or use the BIP with your client and family, it would be best at this point to tailor interventions to each individual client (Halder et al., 2008). Because you may have been creating templates for family BIPs up to this point through cultural targeting, it may be important to further individualize the materials for each family. Such tailoring would require you to use a survey or questionnaire that can be used to measure the extent to which the client identifies with the cultural themes you identified during information gathering and embedded into the BIP. For example, you can use the CIFA (Tanaka-Matsumi et al., 1996) to inform the type and extent of cultural surface and deep structure adaptations that you will embed for individual participants. It is possible that not all establishments will want to create BIP materials to this level of individualization and will instead target a small group of readers. For those who aim to individualize BIPs further, more specific instructions by Halder et al. (2008) may be a good place to start for practitioners who are new to cultural tailoring and wishing to supplement this tutorial with additional information.

Cultural Targeting Versus Cultural Tailoring