Abstract

Conflict, albeit normal in every relationship, can increase stress and tension. Workplace conflict is highly prevalent in the field of health care and has been correlated with lowered job satisfaction and burnout. However, little is known about workplace conflict for practicing Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®). We distributed an electronic survey through the Behavior Analysis Certification Board® (BACB®) to determine the impact and prevalence of workplace conflict for practicing BCBAs. Most of our participants reported various levels of conflict with different workplace professionals including teachers, caregivers, colleagues, and supervisees. We found that a high proportion of practitioners reported losing cases and wanting to leave their jobs because of workplace conflict. Most of our participants did not feel that they had the training they needed to have sufficient skills to resolve workplace conflict effectively. Therefore, in this article we outlined the component skills necessary to manage conflict effectively and made recommendations for training these skills.

Keywords: applied behavior analysis, conflict resolution, workplace conflict, conflict resolution training, employee turnover, employee burnout, interdisciplinary team

In general, conflict is defined as an “antagonistic state or action (as of divergent ideas, interests, or persons).” Being in conflict is normal and a natural part of all relationships. Within the field of human services, Studdert et al. (2003) defined conflict as a “dispute, disagreement, or difference of opinion related to the management of a patient [which] involve[es] more than one individual and require[es] some decision or action.” At present, there is a body of peer-reviewed quantitative and qualitative survey research literature on workplace conflict experienced by a variety of human service professionals. In health care, workplace conflict with a patient has been reported with a prevalence rate of 78% (Breen et al., 2001). The results of another survey indicate that 78% of physicians and nurses experience conflict at work, with patients and/or other staff at least once per week (Azoulay et al., 2009). A similarly high prevalence rate of 83% has been reported in educational settings (Tantleff-Dunn et al., 2002).

Taken together, these descriptive research findings suggest that mitigating workplace conflict and preparing professionals who may be at high risk for facing conflict is important, especially when considering the negative affects workplace conflict can have on the individual and their respective field. Researchers have found that workplace conflict has been correlated with increased employee stress, turnover, burnout, lowered job satisfaction, and lowered professional commitment (Crane & Iwanicki, 1986; Greenhaus et al., 2001; Schwab & Iwanicki, 1982; Shafer, 2002), all of which affect the service provider, the employer, and consumers of their services. It is socially significant to find ways to improve workplace conflict resolution skills of health-care providers given that conflict in relationships is inevitable and the proportion of waking hours the average professional spends at their occupation. Within this robust body of literature on conflict and conflict resolution, there is one human service profession that is greatly underrepresented: Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®).

The number of BCBAs, professionals who are credentialed to practice applied behavior analysis (ABA), has been steadily increasing over the past decade. As of December 2020, there were over 44,000 internationally certified BCBAs, which is 6.3 times the number that were certified in 2010 (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, n.d.-a). In conjunction with the growth of BCBAs, the demand for them has exponentially increased. There were about 20 times the number of U.S. job postings for BCBAs in 2018 compared to 2010, an overall increase of 1,942% over 8 years (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2019). The rising demand for BCBAs is great for the profession, but risk factors for burnout and voluntary turnover (i.e., employees choosing to terminate an existing employment contract) continue to challenge the field (Plantiveau et al., 2018). Moving forward, the retention of competent, ethical BCBAs is as important for the profession of behavior analysis as the recruitment of qualified individuals invested in becoming skilled science-informed practitioners.

The role of the BCBA, often as a supervisor, is to work professionally and collaboratively with other individuals to develop and implement treatment plans. As such, within the profession of ABA alone, the variables affecting voluntary turnover for this position likely differ from other BACB-related credentials outside of BCBAs (e.g., Registered Behavior Technician® [RBT®] and Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst® [BCaBA®]). For example, of the 96 behavior technicians surveyed by Kazemi et al. (2015), the main variables predicting voluntary turnover included: satisfaction with initial trainings, satisfaction with supervision, satisfaction with pay, and different aspects of the job such as career advancement opportunities. Some of these variables do not affect BCBAs and behavior technicians in the same manner given the differing job responsibilities. To maximize career longevity of BCBAs in the profession, behavior analysts must identify the variables within their control that lead to voluntary turnover and find ways to mitigate them. Voluntary employee turnover due to life events (e.g., pursuing a college degree, needing to relocate due to family needs) is likely outside of the employer’s control. On the other hand, workplace variables leading to voluntary employee turnover are in the control of the employer and leaders in the workplace. One such variable may be work experiences that involve frequent and unresolved workplace conflict.

Unlike other human care professions, graduate programs in behavior analysis are not required to have coursework focused on conflict detection and resolution. According to the available curricula and course descriptions of the five programs that produced the most BACB examination candidates from 2015 to 2019 (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, n.d.-b), there are none that require conflict resolution coursework (“ABA Online,” n.d.; “Master of Arts in Applied Behavior Analysis,” n.d.; “Master of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis,” n.d.; “MS in Psychology, Applied Behavior Analysis: Courses,” n.d.; “Online Master of Arts in Special Education [Applied Behavior Analysis],” n.d.). Pastrana et al.’s (2016) evaluation of the most frequently assigned readings for programs that had at least an 80% pass rate in 2014 also yielded no conflict resolution literature. Although conflict management coursework does exist in some graduate programs, the training requirements for BCBAs to become certified is highly technical with a strong focus on the science of human behavior, conceptual understanding of behavioral principles, behavior measurement and assessment, behavior change procedures, and experimental methods to evaluate treatment effects (see the task list requirements to become eligible to sit for the BCBA exam [BACB, 2017]).

When it comes to the workplace, conflict can occur with anyone with whom the BCBA has interactions (e.g., supervisees, boss, payee). However, in most other health-care and human-service professions, the type of workplace conflict that has been targeted for research and training is centered around delivery of treatment (Studdert et al., 2003). Studdert et al.’s (2003)care-centered definition of conflict as differing opinion(s) in treatment paths seems applicable to ABA providers who work among interdisciplinary teams to make decisions regarding the client’s treatment (circumstances that may certainly lend to differences of opinion; see LaFrance et al., 2019). Imagine, for example, a BCBA working to develop a behavior reduction plan for attention-maintained problem behavior to implement in the client’s school setting. If the client’s teacher disagrees with any approach that involves withholding attention when the client engages in problem behavior, there is a risk of conflict between the teacher and BCBA due to the difference in their professional opinions for how to intervene effectively, realistically, and appropriately. For example, the BCBA may suggest an intervention that does not factor in the other contingencies that the teacher has to meet to perform their job appropriately, or the teacher and the BCBA may disagree on the density of the reinforcement schedule. Additional opportunities for conflict may arise with the teacher’s assistant and any other member of the client’s interdisciplinary team with whom the BCBA works.

It can be argued that, in addition to retention, how a BCBA manages workplace conflict can affect their interpersonal relationships at work as well as their therapeutic relationships with consumers (see De Dreu et al., 2004, for workplace conflict implications). Taylor et al. (2018) found by surveying parents of children receiving ABA services (n = 95) that, of the 21 survey questions the authors determined convey compassion and empathy, parents’ Likert scale scores yielded only 6 questions with which they agreed. Taylor et al. (2018) stated that “the majority of the items [that convey empathy and compassion] represent areas for improvement” (p. 658), a potential result of BCBA’s skill deficits in conflict detection and resolution. Conflict management involves active listening, which is an integral skill in empathic care. On a larger scale, BCBAs’ ability to resolve conflict can influence the overall impression of behavior analysts as compassionate, understanding, and collaborative professionals who hold positions of leadership in human care services.

Consider, for example, a BCBA who gets a phone call from a parent who disagrees with the BCBA’s decision to use a picture exchange communication system (PECS) instead of solely depending on vocal-verbal communication for their child. The BCBA’s rationale for implementing PECS as an alternative to vocal–verbal communication may be sound and based on the client’s current prerequisite skill level; however, a solid clinical rationale alone is not sufficient to help the BCBA resolve the conflict with a parent who disagrees with it. To establish trust in the clinical team, as an antecedent condition that sets the occasion for successful conflict resolution, the BCBA listens to the parent so that the parent’s perspective can be factored into the proposed intervention plan, and the parent feels heard (Taylor et al., 2018). In addition, as a consequence strategy, the BCBA must be able relay their rationale for their clinical decision in a manner that leaves room for suggestions for change and improvement without defensiveness. To approach the topic and set the parent at ease, the BCBA will likely have to start by acknowledging responsibility for the conflict and collaborate with the parent to come up with a joint solution. If the BCBA can detect the rising conflict and resolve it successfully, the BCBA will have demonstrated the appropriate leadership and collaboration skills to create the most individualized plan for the client in question. By doing this, the BCBA is not only modeling appropriate conflict management, but they are also ensuring that the parent’s advocacy for their child contacts reinforcement. The success of the intervention plan depends on the parent’s engagement and the overall acceptability of the treatment prescribed: without their input the intervention would have not been realistic, agreeable, or likely successful overall. The BCBA may also develop a stronger relationship with the parent by competently handling a difficult situation, which will likely prove helpful in future interactions. It is likely that the existing professional relationship is strengthened after conflict resolution because resolving conflict effectively involves discussing common values and the shared goal to provide effective care to the client. Having the skills to resolve conflict may also decrease the likelihood of the BCBA losing the case and the parent or the BCBA requesting to work with another behavior health provider. In the end, detecting and resolving the conflict will demonstrate that the BCBA is a professional focused on human care with the skills to be flexible, problem-solve, and manage difficult conversations that arise in professional relationships.

Experiencing high levels of unresolved conflict is not uncommon among human care service providers in general (Breen et al., 2001; Azoulay et al., 2009), and has been associated with voluntary turnover and burnout (Greenhaus et al., 2001; Rupert et al., 2009). To date, however, there are no studies documenting the prevalence nor the impact of workplace conflict specifically for BCBAs. This gap in the literature calls into question whether the data published in other human service professions accurately reflect the experiences of behavior analysts. As the demand for BCBAs continues to rise, knowing how often BCBAs encounter workplace conflict and how they perceive it affects their professional lives is the first step to developing a plan to address the problem.

A Survey of BCBAs

We conducted a survey to explore the frequency and impact of workplace conflict for current BCBAs. In developing the survey, we reviewed existing literature on conflict and adapted measures (Azoulay et al., 2009; Breen et al., 2001; Tantleff-Dunn et al., 2002), or specific survey items (Kazemi et al., 2015), for the purpose of answering our research questions. We also generated new questions because we found no standardized workplace conflict surveys that were available for distribution.1 We developed a pilot survey using Qualtrics online software. Qualtrics has a cell-phone-friendly display, which enables participants to respond to the questionnaire using their cell phones rather than restricting response opportunities to those with access to a computer or tablet. We developed 26 questions, including 10 demographic items (e.g., level of education, number of years of experience, and the types of settings in which they provide services), and 16 rating-scale questions related to workplace conflict to identify the prevalence and impact of the problem (e.g., turnover, job satisfaction, lost cases, and prior training). We conducted a field test of the survey items by sending the survey to a sample of 209 BCBAs and analyzing the results for general trends, agreement, and internal consistency. We then revised several items based on our analyses and the feedback we received from the pilot group of participants prior to distributing it to the larger sample.

We selected our sample by distributing the Qualtrics survey link through the BACB email system. BACB staff sent the email to any BCBA or Board Certified Behavior Analysts-Doctoral® (BCBA-Ds®) registered to receive email correspondence from the BACB. We chose to distribute the survey nationally through the BACB because we wanted a representative sample of behavior analysts. California State University, Northridge (CSUN), Humans Subjects Institutional Review Board approved the study prior to its distribution. We decided to allow participants to respond to the survey anonymously to decrease any social desirability bias to answer questions a certain way and to increase the likelihood they would respond honestly about their experiences in their workplace.

Participants’ responses were saved automatically via Qualtrics. The survey was active for 2 weeks following distribution of the first invitation through the BACB email system. BACB staff sent a reminder email 1 week after the first invitation at the request of the second author. We exported the responses from the online survey platform to the statistical software program SPSS for analysis and ensured there were no duplicate responses by comparing response IDs. Our final sample of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds only included surveys submitted with complete responses to primary survey items of interest (e.g., items related to conflict rate, turnover, lost cases, and training) in the final analyses. We analyzed the responses using frequency counts/percentages and means.

At the time the survey was distributed, the BACB reported that there was a total of 15,856 certificants registered to receive the email containing the survey invitation (D. Killen, personal communication, September 27, 2017). Of those, a total of 3,569 individuals opened the email they received and 665 attempted the survey (i.e., clicked on the survey link and accessed at least the consent page). Our final sample consisted of 601 individuals who completed a portion of the survey (e.g., demographic questions only) and 494 who completed all items.

Following demographic questions, participants were directed to a 14-point, bolded quote of Studdert et al.’s (2003) definition of conflict, along with a mand to keep the definition in mind when answering subsequent questions regarding conflict. We included questions in the survey related to the frequency of conflict with various individuals in the workplace, frequency of unresolved workplace conflict with those individuals, likelihood of turnover, number of lost cases due to workplace conflict, job satisfaction, and level of training with conflict resolution. We posed many of these questions using best-practice recommendations in developing surveys (see Sturgis et al., 2014). For example, we used rating scales without a middle or neutral option, which may be indistinguishable from undecided or I don’t know responses (e.g., we provided answer options ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree)

In Table 1, we provide the demographic characteristics of our participants. We found that the majority of our participants identified as women (85%), between the ages of 34 and 48 (46%), with a master’s degree as their highest level of education (86%), and employed full time at the time of the survey (84%). Also, most respondents (58%) reported being certified by the BACB for over 3 years and 52% self-reported that they had worked as a supervisor in the field of ABA for over 3 years. Most of the participants had primary job responsibilities of supervising a clinical team overseeing client treatment (61%). In addition, participants reported working predominantly in school (21%), home (24%), or both school and home settings (19%). The majority of our participants reported that they had 13 or more clients on their caseload (48%). We compared these demographics to those reported by the National Professional Employment Survey published by the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts (APBA) in 2014 and found that in general our sample was similar to the BCBAs and BCBA-Ds examined by the APBA regarding employment status, length of credential, and type of work (Association of Professional Behavior Analysts, 2015). Unfortunately, we failed to ask questions about sex, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and disability, which should be reported (see Li et al., 2017, for a great discussion of how these demographics have been missing in behavior analytic journals and why we should all begin to report them).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Survey Participants

| Sample Characteristics | Sample Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender identity | Highest degree obtained | ||||

| Female | 509 | 85 | Master’s Degree | 518 | 86 |

| Male | 89 | 15 | Doctoral Degree | 83 | 14 |

| Age | Time credentialed as BCBA | ||||

| 19–33 | 231 | 39 | Less than 1 year | 71 | 12 |

| 34–48 | 268 | 46 | A little over 1 year to 3 years | 180 | 30 |

| 49–62 | 75 | 13 | A little over 3 years to 6 years | 166 | 28 |

| 63+ | 12 | 2 | More than 6 years | 183 | 30 |

| Employment status | Degree designation | ||||

| Full-time | 507 | 84 | Psychology | 99 | 17 |

| Part-time | 73 | 12 | Psychology w/ BA emphasis | 112 | 19 |

| Unemployed or Retired | 14 | 2 | BA or ABA | 151 | 25 |

| Other | 7 | 1 | Education | 26 | 4 |

| Time spent as a supervisor | Education w/ BA emphasis | 37 | 6 | ||

| Less than 1 year | 79 | 13 | Special Education | 60 | 10 |

| A little over 1 year to 3 years | 147 | 25 | Special Ed. w/ BA emphasis | 74 | 12 |

| A little over 3 years to 6 years | 126 | 21 | Other (Counseling, MFT) | 41 | 7 |

| More than 6 years | 223 | 37 | Primary service setting | ||

| Capacity as a BCBA | Public schools | 127 | 21 | ||

| Directly with clients | 63 | 11 | Day school program | 17 | 3 |

| Clinical sup. & direct services | 366 | 61 | Home-based program | 146 | 24 |

| BA not directly working w/ clients | 153 | 26 | Combination school and home | 112 | 19 |

| BA services in different professions | 17 | 3 | Residential program | 35 | 6 |

| Number of clients | Center-based program | 100 | 17 | ||

| 0 | 39 | 7 | Office | 11 | 2 |

| 1–5 | 99 | 17 | Other | 23 | 4 |

| 6–12 | 169 | 28 | Combined settings | 23 | 4 |

| 13– | 287 | 48 | |||

Note. N = 601. Percentages do not all add up to 100 due to the “Choose not to answer” option.

In Table 2 we provided the frequency of conflict BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported across their relationships. We found that 30% of our respondents reported that they experience workplace conflict daily, 40% said weekly, 25% said monthly, 4% said yearly, and 1% said never.BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported more frequent conflict with teachers and caregivers (i.e., the means, medians, and modes were slightly higher with these groups; see Table 2), followed by colleagues and supervisees. When it comes to workplace conflict, it is not just the frequency of conflict that matters, it is also the frequency of unresolved conflict. To account for this, we also analyzed the frequencies of unresolved conflict BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported. We found that 11% of our participants reported that their conflict is always unresolved, 33% said it is often unresolved, 30% said sometimes unresolved, 23% said rarely unresolved, and 2% said never unresolved. We looked across the relationships that BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported having and found that participants reported the highest amount of unresolved conflict with teachers and caregivers, followed by colleagues and supervisees (see Table 2 summary data for unresolved conflict).

Table 2.

Frequency of Conflict across Relationships and How Often It is Unresolved

| Across Relationships | Teachers | Caregivers | Adults (clients>18 years old) | Colleagues | Supervisees | Supervisors | Admin. | Multidisc. | Healthcare | Community Members | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary Data of Frequency of Contacting Conflict (1 = never, 5 = daily) | |||||||||||

| M | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| Mdn | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Mode | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| SD | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Percentage of Responses for Each Coded Frequency of Contacting Conflict | |||||||||||

| Daily (5) | 30.0 | 8.4 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 0.9 |

| Weekly (4) | 39.8 | 24.5 | 25.1 | 16.8 | 14.4 | 16.6 | 11.3 | 13.0 | 9.4 | 10.5 | 2.5 |

| Monthly (3) | 25.1 | 35.3 | 42.8 | 22.3 | 36.2 | 34.7 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 35.8 | 34.5 | 22.5 |

| Yearly (2) | 4.3 | 24.5 | 21.0 | 20.6 | 24.0 | 22.5 | 29.8 | 22.1 | 35.8 | 36.8 | 37.3 |

| Never (1) | 0.8 | 7.4 | 5.6 | 34.0 | 16.2 | 18.2 | 30.7 | 34.1 | 14.8 | 14.1 | 36.7 |

| Summary Data of Frequency of Unresolved Conflict (1 =never, 5 = always) | |||||||||||

| M | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Mdn | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Mode | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| SD | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Percentage of Responses for Each Coded Frequency of Unresolved Conflict | |||||||||||

| Always (5) | 11.2 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 13.0 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 4.9 | 8.5 |

| Often (4) | 33.1 | 21.3 | 13.5 | 9.2 | 15.3 | 12.0 | 14.4 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 14.5 | 7.6 |

| Sometimes (3) | 30.0 | 28.5 | 27.4 | 10.9 | 21.0 | 15.4 | 17.4 | 19.3 | 28.7 | 30.6 | 18.7 |

| Rarely (2) | 23.3 | 26.1 | 34.9 | 29.0 | 29.3 | 34.3 | 24.6 | 23.7 | 29.6 | 28.3 | 26.9 |

| Never (1) | 2.4 | 18.2 | 18.0 | 37.8 | 25.3 | 27.4 | 33.1 | 35.7 | 22.4 | 21.7 | 38.3 |

Note: Only individuals who answered both frequency of contacting conflict and frequency of unresolved conflict were included in the above data analyses.

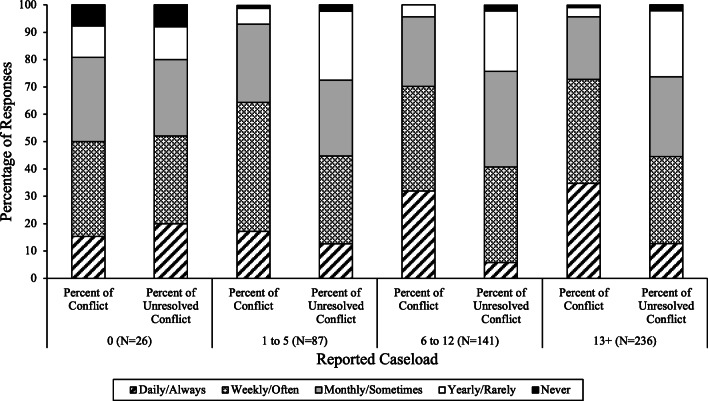

In addition, we asked participants questions about their job satisfaction and likelihood to turnover because of workplace conflict. We provided the participants’ responses to our survey questions in Table 3. We combined agree and strongly agree responses for the summary outlined here to facilitate interpreting our descriptive findings. We asked participants if they have considered leaving a job (previous or current) because of workplace conflict and we found that 62.4% either agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. Overall, 44.7% of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported they have had to terminate or have lost a case due to conflict. It should be noted that we did not differentiate the exact conflict(s) that resulted in termination of cases (e.g., conflict with a parent, conflict with a clinical director, conflict with community members). The majority (i.e., 60.9%) of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds surveyed either agreed or strongly agreed that their satisfaction with their overall job is related to how much conflict they face. We found that the frequency of conflict seemed to increase with BCBA’s/BCBA-D’s reported caseload, which makes sense because increased caseloads BCBAs/BCBA-Ds likely result in interacting with more individuals. It is interesting that the reported amount of conflict that was unresolved seems unaffected by increased caseloads, indicating a stable percentage of unresolved conflict for BCBAs/BCBA-Ds(see Fig. 1). Regarding conflict resolution skills, 94.1% agreed or strongly agreed that knowing how to resolve workplace conflict effectively is an important skill for a BCBA. We found that only 32% of our participants agreed or strongly agreed that they felt they received the training they needed to have sufficient skills to resolve workplace conflict. Finally, 68.9% of our respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they were interested in receiving formal training on how to resolve workplace conflict.

Table 3.

Participants’ Responses to Survey Questions Regarding Conflict

| Item | Yes | No | Prefer not to State | Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have considered leaving a job (previous or current) because of workplace conflict (N = 479) | 0.4 | 38.4 | 24.0 | 12.1 | 7.1 | 12.1 | 5.8 | ||

| I have lost or had to terminate a case/contract because of conflict (N = 475) | 44.7 | 53.8 | 1.5 | ||||||

| I feel my satisfaction with my overall job is related to how much conflict I face (N = 479) | 26.5 | 34.4 | 23.2 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 1.9 | |||

| I feel that knowing how to resolve workplace conflict effectively is an important skill for a BCBA (N = 476) | 73.7 | 20.4 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |||

| I feel I have received the training I needed to have sufficient skills to resolve workplace conflict effectively (N = 476) | 0.4 | 9.9 | 22.1 | 27.5 | 21.0 | 13.2 | 5.9 | ||

| I would be interested in receiving formal training on how to resolve workplace conflict (N = 476) | 0.2 | 26.9 | 42.0 | 18.5 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 3.2 |

Fig. 1.

Percent of Conflict and How Often It is Unresolved as Caseload Increases. Note. N = Number of responses. “Frequency of Conflict” was reported on a Likert scale of Daily, Weekly, Monthly, Yearly, and Never. “Frequency of Unresolved Conflict” was reported on a Likert scale of Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, and Never. The corresponding label for each Likert scale value for each question is depicted above.

Based on the results of our survey, we found that BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported facing conflict at a similar frequency to other human-care professions (Azoulay et al., 2009; Breen et al., 2001; Tantleff-Dunn et al., 2002) and that unresolved conflict may have significant impact on their likelihood to turnover and/or lose cases. Also, supervisors with a greater number of years of experience in the field reported higher rates of conflict than those in their first year, which may suggest a few things. It is possible that the rate of conflict may only increase with time in the absence of formal training. It is also possible that the more experience accrued by the supervisor, the more likely they are to be assigned cases with higher likelihood of conflict. On the other tail, perhaps less experienced BCBAs avoid taking on cases with higher probability of conflict. Lastly, it is possible that without formal training on conflict detection, less experienced BCBAs are less skilled at detecting, and therefore reporting, emerging or actual conflict. Taken as a whole, our findings indicate a socially significant need for BCBAs to receive effective training in conflict resolution.

Recommendations

It is more likely than not that practitioners providing human care services are going to interact with many different individuals and face workplace conflict on a frequent basis. As such, it is important for behavior analysts to know how to resolve workplace conflict effectively and feel that they have sufficient skills to manage conflict when it arises. Based on our results, the majority of BCBAs/BCBA-Ds surveyed do not feel they have received the training they need to resolve conflict and they would be interested in receiving such trainings. At present, there are several conflict-resolution self-help books (see Critchfield, 2010), as well as workshops and trainings that are highly sought after by medical professions and other human-care service providers. The first and second authors reviewed the trainings available and concurred that the conceptual framework for most of them is based on personality theories, which place a focus on personality and its variation among individuals. For example, during our search for books and trainings, we often found titles such as “How Best to Deal with Difficult People” in the workplace. Lectures or instruction-based trainings of this nature likely are relatable and include easily understandable language that is accessible to members of various professions. These trainings are widely accessible, which when compounded with the need for conflict resolution training, may explain why they are often offered to large groups of human-service providers who need conflict resolution training.

Despite their availability, there are several ways the current trainings can be improved with principles of behavior analysis. One major limitation of current trainings is the lack of research-based evidence of their effectiveness on actual behavior change. Second, conflict in the workplace is often attributed to people’s personalities, with an emphasis on the person as the problem (Conlow & Watsabaugh, 2010; Rucci, 1991; Tiffan, 2009), rather than on the environmental contingencies that facilitate and maintain the behaviors that lead to workplace conflict. Discussions of various personalities (probable behaviors in the presence of conflict) may be very helpful at the beginning of training, and the long-standing tradition and success of such trainings demonstrate their social acceptability. Describing the constellations of behaviors someone may face when dealing with another person in conflict can be helpful in teaching discrimination of conflict and current maladaptive approaches, such as avoidance of it. The third limitation to existing trainings is that many of them focus on theories of conflict and the experience of feeling conflict instead of clearly specified strategies to approach and resolve conflict with practical practice opportunities. Overall, most current trainings place a focus on people’s personality rather than behavior, are instruction- instead of practice-based, and lack outcome data demonstrating behavior change.

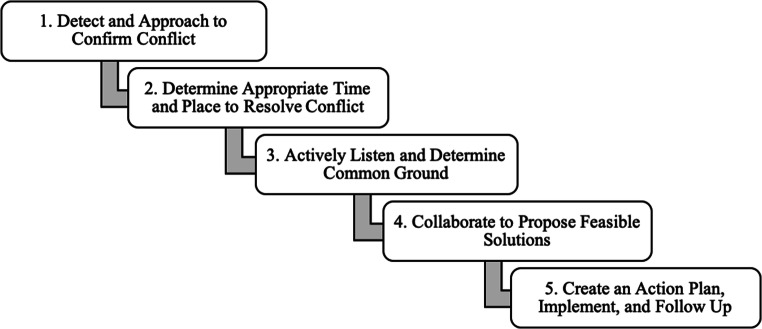

Looking across the literature on conflict resolution, we found some consistent recommendations that, if clearly operationalized, could place the focus on the behaviors of the individuals in conflict and provide us with the component skills needed to manage conflict successfully. First, the BCBA/BCBA-D has an ethical code to which they are expected to adhere before progressing in the conflict-resolution process. If conflict has risen because the BCBA/BCBA-D feels there is an ethical violation, they should follow the steps advised by Bailey and Burch (2016) and the BACB (e.g., bringing it up with the individual first, then if still unresolved reporting to the appropriate superiors). However, the following steps may be helpful as the BCBA/BCBA-D addresses the ethics violation. We identified multiple steps to resolving conflict and the decision points, or the antecedent events, that provide opportunity for a particular strategy to be used. We identified five commonly cited strategies. The first is detecting and approaching to confirm conflict. In the process of detection, it is important for the practitioner to determine if they or a member of their staff or organization is at fault (Rucci, 1991), and if so, providing a sincere apology. The second strategy involves determining the most appropriate time and place to meet with the opposing party to discuss the conflict at hand (Terry, 1996; Tiffan, 2009). Resolving conflict takes time and it is important that both parties are not emotionally responding or in a rush. Carving out time, as close to the event as possible, is helpful in giving both individuals time to discuss their points of view. The third strategy is engaging in active listening, which allows each person to listen to the other person and repeat what they heard. This step is the most important in conflict resolution because it helps each individual hear where the other person is coming from. This step sets the occasion for the individuals in conflict to find common ground by paraphrasing one another’s perspectives and asking open-ended questions to ensure mutual understanding (Conlow & Watsabaugh, 2010; Fisher et al., 1991; Terry, 1996). The fourth strategy involves the individuals looking for commonalities in what they shared and collaborating to generate potential solutions to the problem at hand (Gerardi, 2003; Strom-Gottfried, 1998). Finally, the fifth strategy is developing an action plan to implement and follow-up on the chosen solution and meeting again to ensure the resolution has maintained beyond the meeting where the solution was chosen (Conlow & Watsabaugh, 2010; Tiffan, 2009). See Fig. 2 for illustration of the sequence of these five components of conflict resolution.

Fig. 2.

Components of Conflict Resolution. Note. The five components of conflict resolution derived from the current literature and proposed to comprise a decision-making tree for practitioners who undergo training in conflict resolution.

Let us again consider conflict with a teacher who disagrees with any approach that involves withholding attention when the client engages in problem behavior, and the BCBA who has made this recommendation following a thorough assessment. Following their recommendation, and as soon as they suspect conflict, the BCBA should confirm its existence by stating to the teacher, “What are your opinions on these procedures?” or “How do you feel about this?” to address the presence of conflict without defensiveness (step 1). After the teacher confirms the existence of conflict, the BCBA should work with the teacher to schedule a time and place to have a discussion in an environment where the teacher can freely voice their viewpoint without feeling rushed or put on the spot (step 2). During the meeting at the mutually beneficial time, the BCBA should ask questions and actively listen by engaging in periodic check-ins that include restating exactly the words the teacher produced, not interpretations of the conversation. For example, the BCBA would say, “I hear you say you feel that it is not possible to completely withhold attention in the classroom. Is that correct?” or “I hear that your reservations about withholding attention for problem behavior come from a place of concern about classroom disruptions. Am I understanding your concern?” (step 3). Following this, the BCBA should provide information about why the treatment was selected in the first place without negating the information or concerns the teacher offered by refraining from using words such as “but.” In addition, the BCBA should state that their explanation is meant to provide additional context for moving toward common values and collaborating on a solution. For example, the BCBA can say, “We agree that the problem behavior causes disruption to the classroom and that attention seems to be motivating for the child. What if we make the attention for problem behavior less enticing than for appropriate behavior?” (step 4). Finally, the BCBA and the teacher should come up with and review an action plan. This process might be facilitated by asking questions such as, “What are some ways you think we can make attention for problem behavior less enticing?” and “When the child engages in problem behavior, what if the attention you deliver is limited to a few short words whereas when the child engages in appropriate behavior, you pour on attention by delivering praise and giving the child a fist-bump?” The BCBA and the teacher should then schedule a mutually convenient follow-up time to review the plan’s effectiveness based on their observations and any data collected (step 5).

To facilitate the acquisition of the critical skills, practitioners and researchers should endeavor to create expanded decision-making algorithms and accompanying training workshops to map out all contingencies that teach trainees how and when to engage in the steps of conflict resolution. Engaging in the steps necessary to achieve successful conflict resolution requires a series of clinical decisions that are dependent on the circumstances of each conflict situation that arises. Decision-making trees have been proposed as a tool to teach behavioral practitioners similarly complex skills such as selecting a function-based differential reinforcement procedure given escape-maintained problem behavior (Geiger et al., 2010; see p. 29) and to select the most appropriate method of measurement given a specific behavior (LeBlanc et al., 2015; see p. 79).

At work, behavior analysts may face conflict with their trainees or supervisees, their supervisors or bosses, their colleagues, members of the multidisciplinary team, payees, their clients, and others. Even though we have outlined the common strategies for resolving conflict, there is no cookie-cutter approach to resolving all conflict because the history of the relationship, power dynamics, as well as the stakes if conflict is not resolved, are different for each type of relationship. Therefore, we recommend different trainings for conflict resolution for different types of relationships. Furthermore, we recommend training be conducted using behavior skills training (BST), which involves selecting common conflict scenarios, assigning trainees to role play, teaching the component skills through vocal–verbal instruction, modeling each component skill for trainees, providing trainees with the opportunity to rehearse the component skills they are being taught, and providing them with specific corrective feedback (Himle et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2012). After feedback is delivered trainees rehearse again until their performance meets a predetermined mastery criterion. Performance measurement tools should be utilized to measure change in performance from baseline.

Conclusion and Future Recommendations

From the results of our survey, we have determined that BCBAs/BCBA-Ds face workplace conflict as often as professionals in similar human care professions. Along the same lines, BCBAs/BCBA-Ds in our study reported terminating or losing cases as a result of conflict. Furthermore, BCBAs/BCBA-Ds reported that they have considered leaving a job (previous or current) because of workplace conflict. Despite the reported impact of workplace conflicts by BCBAs/BCBA-Ds, nearly half of them have never received formal training in conflict resolution. Even with the reported high prevalence rates of workplace conflict among BCBAs/BCBA-Ds across different professionals, the related negative outcomes, and the different variables within those relationships that may require nuanced topographical differences in the conflict resolution approach, training in conflict resolution is not required in behavior analytic coursework or certification training programs. It is a worthwhile endeavor to develop and disseminate a behavior analytic model of conflict resolution training to address this area of need. We utilized the results of our survey and literature reviews to recommend five general steps every BCBA should take to resolve conflict. In addition to a five-step decision tree, we proposed an approach to training individuals to utilize the decision tree to resolve conflict. The decision-making tree with corresponding behavior measurement tools can be incorporated in a BST workshop, or in graduate level coursework, for BCBAs. Although we have offered one solution to increasing conflict resolution skills of BCBAs, in the future researchers should endeavor to implement, test, and expand on the suggestions we have made by examining the effectiveness of such conflict resolution training. Following mastery of conflict resolution skills by a BCBA, supervisors can then implement consequence strategies involving specific positive or constructive feedback in vivo to further shape those skills. We recommend that in the future, researchers investigate the differences in function of workplace conflicts across populations with whom BCBAs report conflict, and whether the functions are correlated with specific outcomes (e.g., loss of cases, leaving a job). We also recommend that behavior analysts develop time and cost-efficient training (e.g., manualized training, computer-based instruction) to teach conflict resolution and evaluate their effectiveness using performance measurement tools. Finally, we recommend that researchers empirically evaluate such training programs to test their validity and generalizability across different relationships. Facing conflict is a normal part of every individual’s life. Relationships are not damaged because of the emergence of conflict, but how the conflict is addressed or resolved. To date, BCBAs report that they face high levels of workplace conflict that result in damaged or lost relationships. It is our hope that by identifying the key decision-making steps we have provided direction for training and guiding BCBAs to manage conflict successfully. In turn, we hope that BCBAs experience less stress, less burnout, and less intent to turnover because of unresolved conflict so that they can continue providing behavior analytic services to the thousands of patients in need of their care and have a long and successful career.

Declarations

We know of no conflicts of interest associated with this publication, and there has been no significant support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. Ellie Kazemi confirms that the manuscript has been read and approved for submission by all named authors. The survey study was reviewed and approved by the California State University, Northridge, Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. The data has not been publicly posted but can be requested by contacting Ellie Kazemi.

Footnotes

To access the specific survey questions, please contact the first author.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ABA Online. (n.d.). https://www.fit.edu/aba-online/degree-and-certificate-programs/bcba/. Accessed Jan 2021

- Association of Professional Behavior Analysts. (2015). 2014 U.S. professional employment survey: A preliminary report. http://www.csun.edu/~bcba/2014-APBA-Employment-Survey-Prelim-Rept.pdf. Accessed Jan 2021

- Azoulay, É., Timsit, J. F., Sprung C. L., Soares, M., Rusinová, K., Lafabrie, A., Abizanda, R., Svantesson, M., Rubulotta, F., Ricou, B., Benoit, D., Heyland, D., Joynt, G., Français, A., Azeivedo-Maia, P., Owczuk, R., Benbenishty, J., de Vita, M., Valentin, A. . . . Schlemmer, B. (2009). Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: The conflicus study. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine, 180(9), 853–860. 10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bailey JS, Burch MR. Ethics for behavior analysts. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.-a). BACB certificant data.https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.-b) BCBA examination pass rates for verified course sequences: 2015–2019. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BCBA-Pass-Rates-Combined-201228.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017). BCBA/BCaBA task list (5th ed.).

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2018.https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/US-Employment-Demand-for-Behavior-Analysts_2019.pdf

- Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, Tulsky JA. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(5):283–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlow R, Watsabaugh D. Handling difficult people and situations: Lead people through adversity. Axzo Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Crane SJ, Iwanicki EF. Perceived role conflict, role ambiguity, and burnout among special education teachers. Remedial & Special Education. 1986;7(2):24–31. doi: 10.1177/074193258600700206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS. Crucial issues in the applied analysis of verbal behavior: Reflections on Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when the stakes are high. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2010;26(1):133–145. doi: 10.1007/BF03393087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CKW, van Dierendonck D, Dijkstra MTM. Conflict at work and individual well-being. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2004;15(1):6–26. doi: 10.1108/eb022905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. Penguin Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger KB, Carr JE, LeBlanc LA. Function-based treatment for escape-maintained problem behavior: A treatment-selection model for practicing behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03391755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardi, D. (2003). Conflict management training for health care professionals. Mediate. http://www.mediate.com/articles/gerardi4.cfm (Original work published 2003)

- Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S, Collins KM. Career involvement and family involvement as moderators of relationships between work-family conflict and withdrawal from a profession. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2001;6(2):91–100. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.6.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle MB, Miltenberger RG, Flessner C, Gatheridge B. Teaching safety skills to children to prevent gun play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37(1):1–9. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi E, Shapiro M, Kavner A. Predictors of intention to turnover in behavior technicians working with individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;17:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LL, Raetz PB, Sellers TP, Carr JE. A proposed model for selecting measurement procedures for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;9(1):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0063-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance DL, Weiss MJ, Kazemi E, Gerenser J, Dobres J. Multidisciplinary teaming: Enhancing collaboration through increased understanding. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):709–726. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Wallace L, Ehrhardt KE, Poling A. Reporting participant characteristics in intervention articles published in five behavior-analytic journals, 2013–2015. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2017;17(1):84. [Google Scholar]

- Master of Arts in Applied Behavior Analysis. (n.d.). https://catalog.bsu.edu/en/2020-2021/Graduate-Catalog/Teachers-College/Special-Education/Master-of-Arts-Programs/Master-of-Arts-in-Applied-Behavior-Analysis

- Master of Science in Applied Behavioral Analysis. (n.d.). https://www.nu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MS_Applied_Behavioral_Analysis_Prgram_Flyer.pdf

- MS in Psychology, Applied Behavior Analysis: Courses. (n.d.). https://www.capella.edu/online-degrees/masters-applied-behavior-analysis/courses/

- Online Master of Arts in Special Education (Applied Behavior Analysis). (n.d.). https://asuonline.asu.edu/online-degree-programs/graduate/master-arts-special-education-applied-behavior-analysis/

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(2):2–11. doi: 10.1007/2FBF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana SJ, Frewing TM, Grow LL, Nosik MR, Turner M, Carr JE. Frequently assigned readings in behavior analysis graduate training programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;3:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantiveau C, Dounavi K, Virués-Ortega J. High levels of burnout among early-career board-certified behavior analysts with low collegial support in the work environment. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2018;19(2):195–207. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2018.1438339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rucci, R. B. (1991) Dealing with difficult people: a guide for educators. ERIC Document. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336810

- Rupert PA, Stevanovic P, Hunley HA. Work-family conflict and burnout among practicing psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 2009;40(1):54–61. doi: 10.1037/a0012538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab RL, Iwanicki EF. Perceived role conflict, role ambiguity, and teacher burnout. Educational Administration Quarterly. 1982;18(1):60–74. doi: 10.1177/0013161X82018001005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer WE. Ethical pressure, organizational-professional conflict, and related work outcomes among management accountants. Journal of Business Ethics. 2002;38(1):263–275. doi: 10.1023/A:1015876809254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strom-Gottfried K. Applying a conflict resolution framework to disputes in managed care. Social Work. 1998;43(5):393–401. doi: 10.1093/sw/43.5.393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Burns JP, Puopolo AL, Galper BZ, Truog RD, Brennan TA. Conflict in the care of patients with prolonged stay in the ICU: Types, sources, and predictors. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29(1):1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis P, Roberts C, Smith P. Middle alternatives revisited how the neither/nor response acts as a way of saying “I don’t know?”. Sociological Methods & Research. 2014;43(1):15–38. doi: 10.1177/0049124112452527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tantleff-Dunn S, Dunn ME, Gokee JL. Understanding faculty-student conflict: Student perceptions of precipitating events and faculty responses. Teaching of Psychology. 2002;29(3):197–202. doi: 10.1207/S15328023TOP2903_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR (2019) Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers?. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 654–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Terry PM. Conflict management. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 1996;3(2):3–21. doi: 10.1177/107179199600300202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffan B. Dealing with difficult people. Physician Executive. 2009;35(5):86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]