Abstract

This study aimed to assess the association of childhood trauma, stressful life events and HIV stigma with mental health in South African adolescents from the Cape Town Adolescent Antiretroviral Cohort (CTAAC). The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Life Events Questionnaire and the HIV Stigma Scale for South African Adolescents Living with HIV was used to assess childhood trauma, stressful life events and stigma in adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV and healthy controls enrolled in the CTAAC. These measures were associated with mental health outcomes including the Beck-Youth Inventories, Child Behaviour Checklist, Columbian Impairment Scale, Childrens Motivation Scale, Conners Scale for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder using Pearson correlations and self-reported alcohol use, using Spearman-rank correlation. 63.7% of adolescents reported at least one childhood trauma on the CTQ. Significant associations were reported between CTQ measures and Beck-Youth Inventories. Emotional abuse was associated with anxiety, anger, depression and disruptive behaviour. Emotional neglect was associated with poor self-concept and disruptive behaviour. LEQ total score was significantly associated with Beck-Youth Inventories including anxiety, depression, anger and disruptive behaviour scales. HIV stigma was significantly associated with Beck-Youth Inventories including depression, anger and disruptive behaviour. Childhood trauma, stressful life events and HIV stigma in South African adolescents are associated with anxiety, depression, anger, disruptive-behaviour and poor self-concept. This study highlights the importance of enquiring about exposure to a variety of traumas, particularly those commonly experienced by South African adolescents. In addition, it is important to understand the impact of trauma exposure on each individuals mental health and functioning.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, Mental health, Perinatal HIV infection, Adolescent

Introduction

Mental health symptoms are, amongst numerous other outcomes, associated with childhood trauma in adolescents (Aebi et al., 2015; Ballard et al., 2015; Larson et al., 2017; Mills et al., 2013; de Moraes et al., 2018). Mental health symptoms account for 16% of the global burden of disease in adolescents aged 10–19 years (WHO, 2019), with many common mental disorders beginning in adolescence (Patel et al., 2007). For instance, the prevalence rates of common mental health symptoms, such as depression, in South African female adolescents have been found to be as high as 44.6% (Cheng et al., 2014). Moreover, 12% of adolescents living with HIV screened positive for symptoms of depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (West et al., 2019). A number of reviews have indicated that adolescents who experience significant childhood trauma and negative lifetime events may be at increased risk of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, behavioral issues and substance use disorders to name a few (Dvir et al., 2014; Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Larson et al., 2017; Norman et al., 2012; Simpson & Miller, 2002). It is important to note that there are a significant number of additional risk factors that increase the risk of common mental health symptoms.

Some studies suggest that adolescents may be at increased risk of exposure to chronic trauma (Larson et al., 2017; Macdonald et al., 2010; Overstreet & Mathews, 2011). This concept describes multiple and repeated exposure to traumatic events (Macdonald et al., 2010; Overstreet & Mathews, 2011), which may in turn exacerbate mental health symptoms. This is particularly relevant in South Africa where the majority of youth come from disadvantaged backgrounds (Leeper et al., 2019; Toska et al., 2019). For example, a large proportion of adolescents are exposed to chronic violence, such as repeated assault, frequently in the context of substance use, gang related activities and poverty (Leeper et al., 2019). Furthermore a study found that 93.1% of adolescents in South Africa had experienced more than one type of violence including domestic, school, neighborhood and sexual violence (Kaminer et al., 2013). Multiple childhood traumas experienced amongst South African adolescents also include bullying, emotional trauma, sexual abuse, poverty, parental substance abuse and food insecurity (Boyes et al., 2014; L. Cluver & Orkin, 2009; Oldewage-Theron et al., 2006). South Africa’s unique history, characterised by apartheid, a form of constitutional racial segregation and exploitation, and a long period of political violence and state-sponsored oppression ending only in 1994, suggests a high level of trauma exposure in the general population (Atwoli et al., 2013). In the context of a country in the midst of change, violence in South Africa, and the physical and psychological injuries that can result, is one of the three growing public health crises (along with HIV, tuberculosis and maternal, neonatal, and child health) that have made health care and prevention so challenging (Mayosi et al., 2012; Wyatt et al., 2017).

Adolescents with perinatal HIV infection (PHIV) may experience unique traumas such as stigmatization due to their illness, orphanhood, early hospitalisation, missed school and social opportunities associated with living with a chronic condition (Claude A. Mellins & Malee, 2013). AIDS-orphaned children also have higher rates of depression and PTSD than children orphaned due to other causes (L. D. Cluver et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2014; Claude A. Mellins & Malee, 2013). Stigmatization in PHIV adolescents is characterised by negative attitudes and beliefs towards their condition by themselves and others and often results in poor access to care and adherence to treatment (MacQuarrie et al., 2009). Stigma in PHIV adolescents has also been associated with anxiety and depression (Akena et al., 2012; Boyes & Cluver, 2015; Casale et al., 2019). Notably, the availability and affordability of healthcare remains a challenge for PHIV adolescents in South Africa and therefore may also impact on their mental health (Doyle et al., 2019; Mokomane et al., 2017). Moreover, many PHIV adolescents have lost their parents and are left as the head of the household and are therefore more likely to experience trauma (Mogotlane et al., 2010). A previous study conducted on this cohort when they were 9–12 years old, found higher rates of mental disorders in PHIV children compared to healthy controls (Hoare et al., 2019). Both PHIV children and controls were recruited from communities with the same level of economic standing, settlement type and quality of education. Few studies have reported on the association between childhood trauma and mental health in adolescents living in South Africa.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of childhood trauma, stressful life events and HIV stigma with mental health in South African adolescents from the Cape Town Adolescent Antiretroviral Cohort (CTAAC) (Hoare et al., 2019). First, we hypothesised that South African adolescents in CTAAC may experience trauma, negative lifetime events and HIV stigma. Second, we hypothesised that childhood trauma, negative lifetime events and stigma would be associated with mental health outcomes in South African adolescents in CTAAC.

Methods

Participants

A total of 122 PHIV adolescents and 36 healthy controls were recruited to the neuropsychiatric sub-study of the Cape Town Adolescent Antiretroviral Cohort study (CTAAC) (Hoare et al., 2018). PHIV adolescents were sampled consecutively and were not recruited based on disease complexity or virological suppression/unsuppression. Controls were HIV negative and frequency matched for age and sex; controls selected had similar characteristics in regard to ethnicity, home language, years of education, quality of education and annual household income. Controls and PHIV adolescents underwent rapid HIV testing, which included pre- and post-test counselling, prior to enrolment to confirm HIV status. Exclusion criteria for both PHIV adolescents and controls were an uncontrolled medical condition, an identified central nervous system condition, a history of head injury, a history of perinatal complications or neurodevelopment disorder not attributed to HIV (Hoare et al., 2018). The Childhood trauma questionnaire was completed by 99 PHIV adolescents and 36 controls at the 36 month follow-up visit. Participants were between the ages of 12–15 years and were seen in the Department of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at the University of Cape Town, South Africa (Hoare et al., 2018). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Health Sciences, Cape Town, South Africa. Parental consent and adolescent assent was obtained from all participants in this study in the participants home language.

Descriptive Measures

Age, sex, years of education, percentage of participants with low household income and age of initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), were obtained from medical records and interviews with adolescent/caregiver dyads. CD4+ count and viral load were obtained by blood draw.

Trauma, Negative Life Events and Stigma Measures

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form was used to assess retrospective childhood trauma. It is a 28-item self-report 5-point Likert scale that provides valid screening for history of abuse and neglect experienced during childhood and adolesence. It measures five types of maltreatment: physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as physical and emotional neglect. Scores range from 25 to 125, with higher scores representing more severe exposure to trauma (D. P. Bernstein et al., 2003). Due to the retrospective nature of CTQ, there is a chance for minimization/denial of the extent of childhood trauma experienced. The minimization/denial scale comprises three items that are dichotomized and summed. Any score above 0 indicates minimization. If participants scored 1–3 on the scale, it suggests possible underreporting of childhood trauma. A score of 0 corresponds to no minimization, 1 to low minimization, 2 to intermediate minimization and 3 to high minimization (D. Bernstein & Fink, 1998).

The Life Events Questionnaire measures 70 specific life events. This includes traumatic events as well as environmental stressors. The responses are dichotomous and are tallied for a total score out of 70 (Masten et al., 1994).

Stigma was measured with the HIV Stigma Scale for South African Adolescents Living with HIV (Pantelic et al., 2018). This inventory consists of 10 items which measure the three HIV stigma mechanisms experienced by adolescents living with HIV, namely enacted, anticipated and internalized stigma. Participants are asked to rate each statement about their HIV status on a 3-point Likert scale.

Mental Health Measures

The Beck-Youth Inventories is a self-report scale, completed by the adolescents themselves, and was used to assess an adolescents’ experience of depression, anxiety, anger, disruptive behaviour and self-concept (Deighton et al., 2014). The caregivers of the adolescents reported on the following scales: The Child Behavior Checklist was used to assess adolescent behavioural and emotional problems and psychopathology (Verhulst, 1989). The Columbia Impairment Scale was used to assess functional impairement in adolescents (Attell et al., 2020). The Childrens Motivation Scale was used to measure adolescents motivation levels or tendency toward apathy (Gerring et al., 1996). The Conners Scale for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder assessed adolescents ADHD levels (Izzo et al., 2019). Self-reporting of alcohol use and urine toxicology for ilicit substances were also included.

All questionaires were administered by trained study staff who have extensive experience working with PHIV adolescent. Questionnaires were conducted in private rooms in the participants home language or language of preference and were forward and back translated by an independent language expert. In addition, all questionairres have been proved reliable for use in isi-Xhosa speaking adolescents in South Africa (Joska et al., 2011)(Hoare et al., 2016).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic and clinical variables. T-tests were used for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Pearson’s correlations were used to test associations between trauma subtypes on the CTQ, total LEQ, and total stigma with BECK-Youth inventories, CBCL, CIS, CMS and Conners Scale. Spearman rank correlations were used to associate self-reports of alcohol use and urine toxicology, as well as HIV status with the CTQ subtypes, total LEQ and total stigma. Benjamini Hochberg FDR correction for p < 0.05 was used to correct for multiple comparisons throughout.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Attributes of PHIV Adolescents and Healthy Controls (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of PHIV adolescents and healthy controls (n = 135)

| Variable | PHIV (n = 99) | Controls (n = 36) | Statistic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years: Mean (SD) | 13.49 (0.99) | 13.76 (1.24) | T = 1.163 | P = 0.250 |

| Sex: Male/Female | 45/54 | 18/18 | X = 0.219 | P = 0.640 |

| Level of education highest grade in years: mean (SD) | 5.76 (1.36) | 5.96 (1.46) | T = 1.288 | P = 0.200 |

| Low household income (%)* | 74 (74.7%) | 28 (77,8%) | X = 0.638 | P = 0.888 |

| Age of ART initiation (SD) (n = 99) | 3.38 (2.49) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Viral load detectable/undetectable (n = 99) | 45/54 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Viral load median (IQR) | 49 (132) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CD4 count median (IQR) cells/mm3 (n = 99) | 687 (543) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Self-report of alcohol use: Yes/No | 25/74 | 0/36 | X = 11.157 | P < 0.001*** |

| Urine Toxicology substance use: Mandrax/cannabis/none | 1/2/96 | 0/1/35 | X = 0.432 | P = 0.806 |

| Beck Self-Concept Inventory | 52.96 (9.32) | 51.85 (9.47) | T = −0.588 | P = 0.559 |

| Beck-Y Anxiety Inventory | 45.90 (11.78) | 47.56 (10.75) | T = 0.756 | P = 0.452 |

| Beck-Y Depression Inventory | 41.70 (9.02) | 44.47 (10.66) | T = 1.355 | P = 0.181 |

| Beck-Y Anger Inventory | 37.92 (8.37) | 40.50 (8.66) | T = 1.509 | P = 0.137 |

| Beck-Y Disruptive Behavior Inventory | 41.40 (8.85) | 44.09 (8.23) | T = 1.605 | P = 0.114 |

| CBCL Total Competence | 38.20 (8.89) | 41.55 (7.92) | T = 2.024 | P = 0.047** |

| CBCL Internalising behaviour | 50.09 (10.16) | 49.24 (10.43) | T = −0.407 | P = 0.686 |

| CBCL Externalising behaviour | 48.53 (10.95) | 46.06 (11.19) | T = −1.103 | P = 0.275 |

| CBCL Total problems | 49.20 (11.35) | 46.27 (11.51) | T = −1.269 | P = 0.210 |

| CMS Total | 3.15 (6.05) | 4.94 (11.35) | T = 1.176 | P = 0.242 |

| CIS Total | 43.06 (7.74) | 43.66 (5.90) | T = 0.470 | P = 0.640 |

| Conners Scale for ADHD | 6.72 (9.92) | 5.97 (6.33) | T = −0.513 | P = 0.609 |

| CTQ Physical abuse | 5.74 (1.97) | 6.14 (2.26) | T = 0.944 | P = 0.349 |

| CTQ Sexual abuse | 5.42 (1.42) | 5.50 (1.18) | T = 0.311 | P = 0.757 |

| CTQ Emotional abuse | 6.19 (1.89) | 7.17 (2.88) | T = 2.279 | P = 0.024** |

| CTQ Emotional neglect | 8.92 (3.90) | 9.56 (4.11) | T = 0.807 | P = 0.423 |

| CTQ Physical neglect | 6.87 (2.13) | 6.97 (1.83) | T = 0.278 | P = 0.782 |

| CTQ Total | 44.25 (6.09) | 46.03 (6.96) | T = 1.353 | P = 0.182 |

| LEQ Total | 6.93 (6.44) | 9.64 (8.51) | T = 1.977 | P = 0.050 |

| Stigma total | 2.17 (2.87) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

All Beck-Y Inventories, CBCL scales, CIS and Conners ADHD are reported as standardised t-values

Abbreviations: CBCL – Childhood Behavior Checklist; CIS – Columbia Impairment Scale, CMS – Childrens Motivation Scale, CTQ – Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, LEQ – Life Events Questionnaire

*A household income of R0 – R25 000 per annum is considered low in this case

**Significant at p < 0.05 not corrected for multiple comparisons

***Significant at p < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons

The mean age for PHIV adolescents was 13.5 years, with 45 males and 54 females. For healthy controls the mean age was 13.8, with 18 males and 18 females. Low household income was reported for 74 PHIV adolescents and 28 controls. Twenty-five PHIV adolescents self-reported alcohol use, which was significantly different to controls who reported no alcohol use. The urine toxicology screens were positive in 1 PHIV adolescent for mandrax and 2 for cannabis, as well as testing positive on cannabis for 1 control. All demographic measures were well matched between PHIV adolescents and controls apart from alcohol use. For PHIV adolescents, mean age of ART initiation was 3.4 years with a median duration of 9.82 years. Viral load was detectable for 45 PHIV adolescents with a viral load median of 49 and CD4 count median of 687.

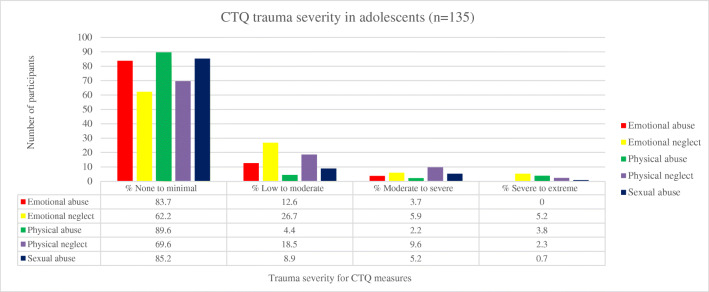

Description of Trauma Severity for Total Sample (Figure 1)

Fig. I.

Trauma severity for CTQ sub-scales in adolescents (n=135). Abbreviations: CTQ – Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

A total of 63.7% of adolescents reported any trauma. The most common trauma reported was emotional neglect and the least common trauma reported was physical abuse. Other trauma subtypes indicated that 22 adolescents reported emotional abuse, 20 reported sexual abuse and 41 reported physical neglect. The majority of trauma reported was in the none to minimal range for all trauma subtypes.

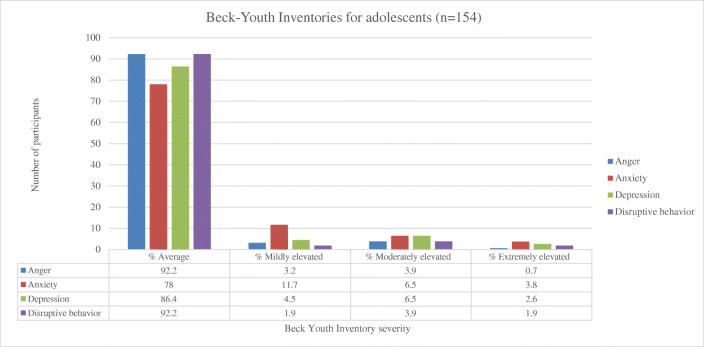

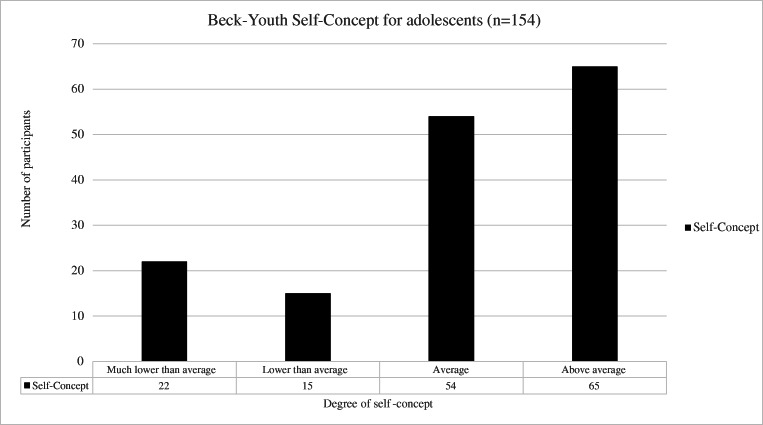

Description of Beck-Youth Inventories Degree and Severity for Total Sample (Figures 2 and 3)

Fig. II.

Severity of anger, anxiety, depression and disruptive behaviour as measured by the Beck-Youth Inventories for adolescents (n = 154). There was missing data for n = 4 participants

Fig. III.

Degree of self-concept as measured by the Beck-Youth Self-Concept Inventory for adolescents (n = 154). There was missing data for n = 4 participants

For the Beck-Y Anger subscale 12 adolescents reported above the average range of anger. For the Beck-Y Anxiety subscale, 34 adolescents reported above the average range of anxiety. For the Beck-Y Depression scale, 21 adolescents reported above the average range of depression. For the Beck-Y Disruptive Behaviour subscale, 12 adolescents reported above the average range of disruptive behaviour. For the Beck-Y Self-Concept Scale, 37 adolscents reported below average self-concept. There was missing data for n = 4 participants.

Description of Child Behaviors Checklist for Total Sample

For the CBCL total competence scores, 83 adolescents scored within the normal range and 66 adolescents scored below normal, indicating impaired competence. For the internalising behaviour checklist, 133 adolescents reported no internalising behavior, with 19 adolescents reporting some degree of internalising behaviour. No externalising behaviors were reported by 135 adolescents, with 17 reporting some degree of externalising behavior. For the total problems scale, 132 adolescents reported no total problems with 20 reporting problems. There was missing data on the internalising and externalising and total problems scale for n = 6 participants and missing data on the total competence scale for n = 9.

Description of Degree of Minimization when Reporting Childhood Trauma for Total Sample

95 adolescents reported some degree of minimization. Of these adolescents 33 reported low minimization, 36 reported intermediate minimization and 26 reported high minimization. Of the adolescents who reported low minimization, 5 reported no to minimal trauma and 28 reported trauma. Of the adolescents who reported intermediate minimization, 19 reported no to minimal trauma and 17 reported trauma. Of the adolescents who reported high minimization, 21 reported no to minimal trauma and 5 reported trauma.

Association of CTQ, LEQ and Stigma Scores with Beck-Youth Inventories in Adolescents (Table 2)

Table 2.

Significant associations of CTQ subscales, LEQ and stigma with Beck-Youth Inventories in adolescents (n = 135)

| Variable | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Emotional abuse | Emotional neglect | Physical neglect | LEQ total | Stigma total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck-Youth Self-Concept Inventory |

R = -0.172 P = 0.050 |

R = 0.012 P = 0.894 |

R = -0.208 P = 0.017 |

R = -0.294 P = 0.001* |

R = -0.082 P = 0.351 |

R = -0.174 P = 0.047 |

R = -0.205 P = 0.044 |

| Beck-Youth Anxiety Inventory |

R = 0.114 P = 0.193 |

R = 0.014 P = 0.876 |

R = 0.224 P = 0.010* |

R = 0.043 P = 0.625 |

R = 0.159 P = 0.070 |

R = 0.407 P < 0.001* |

R = 0.161 P = 0.115 |

| Beck-Youth Depression Inventory |

R = 0.170 P = 0.053 |

R = 0.066 P = 0.452 |

R = 0.391 P = <0.001* |

R = 0.193 P = 0.027 |

R = 0.217 P = 0.013 |

R = 0.527 P < 0.001* |

R = 0.437 P < 0.001* |

| Beck-Youth Anger Inventory |

R = 0.150 P = 0.088 |

R = 0.014 P = 0.871 |

R = 0.323 P = <0.001* |

R = 0.174 P = 0.047 |

R = 0.174 P = 0.047 |

R = 0.600 P < 0.001* |

R = 0.451 P < 0.001* |

| Beck-Youth Disruptive Behavior Inventory |

R = 0.196 P = 0.025 |

R = 0.075 P = 0.392 |

R = 0.358 P = <0.001* |

R = 0.246 P = 0.005* |

R = 0.205 P = 0.019 |

R = 0.535 P < 0.001* |

R = 0.313 P = 0.002* |

*Significant differences at P < 0.05 FDR-corrected

Stigma total associations were only performed within the PHIV group (n = 99)

There were significant associations of CTQ emotional abuse with Beck-Y Inventories. CTQ emotional neglect was also significantly associated with Beck-Y Inventories. LEQ total score was significantly associated with Beck-Y HIV stigma was significantly associated with Beck-Y inventories including depression, anger and disruptive behaviour. There was no significant association between CTQ measures, LEQ or HIV stigma with the CBCL scores, CIS, CMS, HIV status, urine toxicology and alcohol use.

Discussion

This study explored levels of childhood trauma, stressful life events and HIV stigma and their associations with mental health outcomes in an adolescent cohort in South Africa. First, we found that 63.7% of South African adolescents in this study experienced at least one type of childhood trauma, with emotional neglect being the most prevalent. Second, we found that there was an association of childhood trauma, as measured by the CTQ, with Beck-Y inventories. Stressful life events, as measured by the LEQ, were associated with Beck-Y inventories. Lastly, HIV stigma was associated with Beck-Y inventories.

Previous studies of childhood trauma in healthy South African adolescents have reported similar CTQ scores, with emotional neglect also being the most prevalent form of trauma (Martin et al., 2014, 2019; Nöthling et al., 2019). A review by Meinck et al. reported high rates of childhood trauma in studies conducted in numerous African countries including South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Swaziland and Mauritania, with the highest prevalence being 64% in Egypt (Meinck et al., 2015). The majority of these studies assessed physical and sexual abuse with prevalence rates ranging from 7.6% – 45% and 1.6% – 77.7% respectively (Meinck et al., 2015). Although we found notably high rates of trauma in our sample, there were many children who reported none to minimal trauma; this may in part be due to 70.4% of the cohort minimizing their experience of trauma. Moreover, the level or experience of trauma may not have been as significant as presumed; in that each individual may have experienced their level of impact of trauma subjectively, which cannot be measured statistically as a given specific level. PHIV adolescents are more likely to have access to counselors, caregivers and medical staff due to their chronic illness. This social/medical support in turn has been shown to contribute to their characteristics of resilience and ability to cope (Bhana et al., 2016; Kuo et al., 2019; Petersen et al., 2010), which ultimately may mitigate their experience or exposure to childhood trauma. Supporting studies found reduced mental health symptoms in adolescents who experienced emotional warmth in their parent-child relationship and school connectedness (de Moraes et al., 2018; Sharp et al., 2018). However, HIV stigma, a common experience for young people living with HIV, can be considered traumatic and has been associated with mental health outcomes (Boyes et al., 2019).

Worryingly, adolescents tend to have experienced more traumas by later adolescence (Finkelhor et al., 2005, 2007). Studies conducted on female youth indicate that they are more likely to experience sexual trauma between the ages of 16 and 25 (Hirschowitz, Ros; Worku, Seble; Orkin, 2000). In South Africa where disadvantaged households are frequently patriarchal (Morrell et al., 2012), this dynamic increases the risk of gender based violence (Jewkes et al., 2006). Given the young age of our cohort compared to other studies (Martin et al., 2014, 2019; Nöthling et al., 2019) it may be that they have not yet experienced extremely high levels of exposure to trauma. This is concerning especially since adults living with HIV have reported high rates of childhood trauma (Bekele et al., 2018; LeGrand et al., 2015), emphasizing the need for longitudinal work. Furthermore, it is important to note that responses to the CTQ may have been influenced by cultural as well as adolescent expectation within their own society at a micro level. For example, studies have found that female adolescents struggle to seek help after experiencing sexual assault (Smith et al., 2010), this may prevent disclosure of these incidences as trauma. Males are also often expected to take on an authoritative role if there is no father present, which is often the case in homes of PHIV adolescents (Bray & Dawes, 2016), this may not be experienced as trauma. Moreover, studies have reported childhood trauma and mental health resilience in South African adolescents (Collishaw et al., 2016; MacEdo et al., 2018; Phasha, 2010).

It is important to note that the minimization scores calculated for the CTQ show that 70.4% of adolescents in this study reported some degree of minimization. In addition, of the adolescents who reported high minimization, 80.8% reported in the none-minimal trauma category indicating that these adolescents are most likely under-reporting their experience of trauma. It is important to note that under-reporting is a greater risk than over-reporting (Maughan & Rutter, 1997). A study using a large multi-national sample also found that minimization is not rare and that prior analysis of maltreatment prevalence and its effects that have used the CTQ may have underestimated its incidence and impact (MacDonald et al., 2016).

Here we report on significant associations between childhood trauma, negative life events and stigma with mental health outcomes. Emotional abuse and emotional neglect were positively associated with all Beck-Y Inventories including depression, anxiety, disruptive behaviour, anger and self-concept. Supporting this, a review by Mills et al (Mills et al., 2013), found adolescents exposed to childhood maltreatment, particularly emotional abuse and neglect, reported higher levels of both internalizing and externalizing behaviour. Additionally, another review by Norman et al (Norman et al., 2012), also found an association between emotional abuse and neglect with depression in adolescents. Furthermore, studies have found that psychological maltreatment and physical abuse in childhood resulted in an increased risk of low self-esteem and self-concept in adolescence in Tanzania and India respectively (Devi et al., 2013; Mwakanyamale & Yizhen, 2019). LEQ scores were associated with all Beck-Y inventories apart from the self-concept inventory. Only a few studies have investigated the association of LEQ scores with mental health outcomes in adolescents (Sun et al., 2017). HIV stigma was associated with Beck-Y inventories including depression, anger and disruptive behaviour. This supports previous studies conducted in South African adolescents, which report on the association between stigma and depression (Boyes & Cluver, 2015; Casale et al., 2019).

We did not find any associations of CTQ measures, LEQ scores and stigma with CBCL scores, Columbia Impairment Scale, Childrens Motivation Scale, HIV status, urine toxicology or alcohol use. No association between childhood trauma and alcohol use was unexpected. A previous study conducted in this cohort on a larger number of participants found that 1 in 10 adolescents reported having used alcohol, although the use of tobacco and other drugs were low (Brittain et al., 2019). Notably, other risk taking behaviours reported in this study included sexual activity, bullying others and suicidality; moreover, all risk taking behaviour in PHIV adolescents was associated with poor adherence to ART (Brittain et al., 2019). Notably, another study conducted in South African adolescents reported an association between childhood abuse measured by the CTQ and greater alcohol and drug problems (Hogarth et al., 2019). Moreover, alcohol use has also been associated with mental health disorders in PHIV adolescents (Claude Ann Mellins et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2010). It is likely that the reason we did not find any associations between childhood trauma and alcohol use as well as toxicology reports is that there were fewer reported cases in this study cohort compared to other studies in adolescents, as well as the small sample size included in this study.

Although we did not measure what mediates the association between childhood trauma and mental health, previous studies have suggested that childhood trauma resulting in mental health symptoms might be due to increased stress sensitivity or emotion dysregulation (Peh et al., 2017; Rauschenberg et al., 2017). Additionally the role of the HPA axis has been implicated in the association of childhood trauma with behavioural issues in adolescents in previous studies (Kuhlman et al., 2018). Numerous factors other than childhood trauma may contribute to the development of mental health symptoms in South African adolescents (Woollett et al., 2017). The causal relationship between childhood trauma and mental health symptoms is complex and requires further investigation.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, as the study is cross-sectional we are not able to make inferences about what mediates the association between childhood trauma and mental health. Second, the majority of childhood trauma measures were derived from self-report data, this may have been subject to under or over reporting of events and symptoms (Demetriou et al., 2015). Third, due to the CTQ and LEQ being retrospective measures of childhood trauma and negative life events, responses may have been subject to recall bias (Frissa et al., 2016). Notably, the CTQ is a restrictive measure of childhood trauma in that it does not measure the impact of trauma. In addition, the CTQ may be impacted by minimization. The scale is only rated on 5 dimensions, which potentially do not provide enough granularity when investigating CTQ minimization. Moreover, responses for the LEQ are dichotomous and therefore also fail to identify the severity of trauma experienced during or after the event. Fourth, the sample size for healthy controls was significantly smaller than PHIV adolescents. Furthermore, the healthy controls were recruited from Masiphumelele (Freedom House, 2017), a region where adolescents are exposed to particularly high levels of trauma that encompass high rates of poverty and crime (SAHO, 2019). Lastly, the minimization scores for CTQ indicate that the majority of adolescents in this study are likely under-reporting their experience of trauma.

Despite its limitations, the strengths of this study and its novelty lie in the uniqueness of this cohort. In South Africa, no previous study has investigated the association of trauma with mental health symptoms in adolescents, including PHIV adolescents. The historical background of South Africas apartheid regime provides a unique context that underlies trauma in South African youth to this day (Adonis, 2016). As the majority of current studies have been conducted in higher income countries, there is value in including data from limited resource regions where little is published. In addition, HIV is a significant trauma that is seen across the globe but more so in South Africa. Children and adolescents are a relatively understudied population, and this is an important emerging research area in South Africa. While many structural factors have been studied, mental health problems that are prevalent in South Africa have received less attention. In conditions of extreme poverty and instability, characteristic of much of Sub-Saharan Africa, the pressures on parents differ markedly from those faced by parents in higher income communities that are typically the focus of research in adolescent mental health (Wyatt et al., 2017). The majority of the adolescents included in this cohort are living with HIV, which as mentioned is in itself is a traumatic experience. As well as living with HIV, South African adolescents experience concerningly high levels of gender based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV). A meta-analysis indicated an estimated 28% of adolescent and 29% of young adult women reported lifetime physical or sexual IPV, which was found to be most prevalent in the East and Southern African region (Decker et al., 2015). Another study found an association between lower socio-economic status, childhood trauma and increased likelihood of having gender inequitable masculinity (Jewkes et al., 2016). Furthermore, a study found a 30.9% prevalence of IPV experienced by girls in grade 8 in South Africa (Shamu et al., 2016). Moreover, the age range of early adolescence in this study is important as most studies that investigate this association investigate mental health outcomes in much older adolescent cohorts.

The CTQ has been validated in South Africa and amongst adolescents (Charak et al., 2017; Spies et al., 2019), making it a reliable tool in investigating childhood trauma exposure. However, future studies would benefit from using additional measures such as GBV and IPV, which have been shown to be particularly concerning in South African adolescents (Jewkes et al., 2006, 2016; Shamu et al., 2016). Further investigation into the association between childhood trauma and alcohol and substance use in this cohort is also needed, as a number of studies in South Africa and internationally have found a significant correlation between these two factors, which in turn has been shown to impact mental health symptoms (Barahmand et al., 2016; Benjet et al., 2013; Oshri et al., 2012; Park et al., 2019). Moreover, future studies would benefit by using tools measuring more detailed experiences of childhood trauma, such as the Adverse Child Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) developed by the World Health Organisation, which was adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente’s ACE study in America (Felitti et al., 1998; WHO, 2018), in order do obtain a more accurate representation of the meaning of trauma for the individual. The ACE-IQ is also able to draw correlations between negative adolescent outcomes and has been validated recently in adolescents (Kidman et al., 2019). In addition it has been used previously in South African PHIV adolescents (Kidman et al., 2018). Furthermore, the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT) developed by Dr. Perry is another useful tool to consider in future studies (Hambrick, Brawner, & Perry, 2019a). The NMT allows clinicians to catalogue the child’s developmental history and current functioning, giving more information into the timing of developmental experiences and how this impacts current functioning in key brain-mediated domains (Hambrick, Brawner, & Perry, 2019a; Hambrick, Brawner, Perry, et al., 2019b). Despite the difficulties in disclosing trauma by many children, the study staff made effort to address this by only administering the CTQ at the end of the day in order to build trust between the adolescents and the study staff before asking difficult questions. Lastly, future studies would benefit from a larger healthy control sample size and for controls to be recruited from the same areas as PHIV adolescents.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings in this study indicate that 63.7% of adolescents in South Africa have experienced at least one trauma before the age of 14. Childhood trauma, negative life events and stigma were associated with numerous mental health outcomes including depression, anxiety, disruptive behaviour, anger and poor self-concept. This study provides a foundation for future longitudinal research to assess childhood trauma and its association with mental health disorders in South African adolescents as they age. This study highlights the importance of understanding the emotive outcome and impact of trauma exposure in adolescents living in South Africa.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the staff on the CTAAC neuropsychiatric sub-study for their work towards primary data collection. We would also like to give special thanks to all adolescents and their parents/caregivers who participated in the CTAAC neuropsychiatric sub-study.

Author Contributions

JH is the PI of this study. HJZ is the PI of the CTAAC study, for which the data was derived. JPF carried out the statistical analysis. TS wrote the article. The remaining authors helped conceive the study, reviewed and approved of the final article.

This paper has not been funded directly. Funding for CTAAC is provided by R01HD074051 and South African Medical Research Council (SA MRC). HJZ and DJS are supported by the SA MRC.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adonis CK. Exploring the salience of intergenerational trauma among children and grandchildren of victims of apartheid-era gross human rights violations. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology. 2016;16(1–2):163–179. doi: 10.1080/20797222.2016.1184838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Mclaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Kessler RC, Koenen KC. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in South Africa: Analysis from the south African stress and health Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barahmand U, Khazaee A, Hashjin GS. Emotion dysregulation mediates between childhood emotional abuse and motives for substance use. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2016;30(6):653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekele T, Collins EJ, Maunder RG, Gardner S, Rueda S, Globerman J, Le TL, Hunter J, Benoit A, Rourke SB, Ohtn Cohort Study Team T. Childhood adversities and physical and mental health outcomes in adults living with HIV: Findings from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network Cohort Study. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2018;2018:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2018/2187232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Méndez E. Chronic childhood adversity and stages of substance use involvement in adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(1–3):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana A, Mellins CA, Small L, Nestadt DF, Leu CS, Petersen I, Machanyangwa S, McKay M. Resilience in perinatal HIV+ adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2016;28(2):49–59. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes ME, Cluver LD. Relationships between familial HIV/AIDS and symptoms of anxiety and depression: The mediating effect of bullying victimization in a prospective sample of south African children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(4):847–859. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes ME, Cluver LD, Meinck F, Casale M, Newnham E. Mental health in south African adolescents living with HIV: Correlates of internalising and externalising symptoms. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2019;31(1):95–104. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1524121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, R., & Dawes, A. (2016). Parenting, Family Care and Adolescence in East and Southern Africa: An evidence-focused literature review. www.unicef-irc.org

- Brittain K, Myer L, Phillips N, Cluver LD, Zar HJ, Stein DJ, Hoare J. Behavioural health risks during early adolescence among perinatally HIV-infected south African adolescents and same-age, HIV-uninfected peers. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2019;31(1):131–140. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale M, Boyes M, Pantelic M, Toska E, Cluver L. Suicidal thoughts and behaviour among south African adolescents living with HIV: Can social support buffer the impact of stigma? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;245:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charak R, de Jong JTVM, Berckmoes LH, Ndayisaba H, Reis R. Assessing the factor structure of the childhood trauma questionnaire, and cumulative effect of abuse and neglect on mental health among adolescents in conflict-affected Burundi. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2017;72:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver LD, Orkin M, Gardner F, Boyes ME. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2012;53(4):363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S, Gardner F, Lawrence Aber J, Cluver L. Predictors of mental health resilience in children who have been parentally bereaved by AIDS in urban South Africa. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2016;44(4):719–730. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Latimore AD, Yasutake S, Haviland M, Ahmed S, Blum RW, Sonenstein F, Astone NM. Gender-based violence against adolescent and young adult women in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou, C., Ozer, B. U., & Essau, C. A. (2015). Self-Report Questionnaires. In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp507.

- Devi R, Anand S, Shekhar C. Abuse and neglect as predictors of self concept among below poverty line adolescents from India. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling. 2013;5(6):122–128. doi: 10.5897/IJPC2013.0213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS, Perma-Nente K. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. (2017). Xenophobia Outsider Exclusion Addressing Frail Social Cohesion in South Africa’s Diverse Communiies Masiphumelele Case Study. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Masiphumelele_ZA_Community_Case_Study_FINAL.pdf

- Frissa S, Hatch SL, Fear NT, Dorrington S, Goodwin L, Hotopf M. Challenges in the retrospective assessment of trauma: Comparing a checklist approach to a single item trauma experience screening question. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(20):20. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0720-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick EP, Brawner TW, Perry BD. Timing of early-life stress and the development of brain-related capacities. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2019;13:183. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick EP, Brawner TW, Perry BD, Brandt K, Hofmeister C, Collins JO. Beyond the ACE score: Examining relationships between timing of developmental adversity, relational health and developmental outcomes in children. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2019;33(3):238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschowitz, Ros; Worku, Seble; Orkin, M. (Statistics S. A. (2000). Quantitative research findings on rape in South Africa. In Statistics.

- Hoare J, Phillips N, Joska JA, Paul R, Donald KA, Stein DJ, Thomas KGF. Applying the HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder diagnostic criteria to HIV-infected youth. Neurology. 2016;87(1):86–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth L, Martin L, Seedat S. Relationship between childhood abuse and substance misuse problems is mediated by substance use coping motives, in school attending south African adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;194(July 2018):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Koss MP, Levin JB, Nduna M, Jama N, Sikweyiya Y. Rape perpetration by young, rural south African men: Prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63(11):2949–2961. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Jama-Shai N, Chirwa E, Dunkle K. Understanding the relationships between gender inequitable behaviours, childhood trauma and socio-economic status in single and multiple perpetrator rape in rural South Africa: Structural equation modelling. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joska JA, Westgarth-Taylor J, Myer L, Hoare J, Thomas KGF, Combrinck M, Paul RH, Stein DJ, Flisher AJ. Characterization of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders among individuals starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(6):1197–1203. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Nachman S, Dietrich J, Liberty A, Violari A. Childhood adversity increases the risk of onward transmission from perinatal HIV-infected adolescents and youth in South Africa. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2018;79:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidman R, Smith D, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP. Psychometric evaluation of the adverse childhood experience international questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2019;92:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman KR, Geiss EG, Vargas I, Lopez-Duran N. HPA-Axis activation as a key moderator of childhood trauma exposure and adolescent mental health. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2018;46(1):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0282-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SP, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Ramgopal SP, Dandona L. Depression among AIDS-orphaned children higher than among other orphaned children in southern India. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2014;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C, LoVette A, Pellowski J, Harrison A, Mathews C, Operario D, Beardslee W, Stein DJ, Brown L. Resilience and psychosocial outcomes among south African adolescents affected by HIV. AIDS (London, England) 2019;33(1):29–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand S, Reif S, Sullivan K, Murray K, Barlow ML, Whetten K. A review of recent literature on trauma among individuals living with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2015;12:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, Thomas ML, Sciolla AF, Schneider B, Pappas K, Bleijenberg G, Bohus M, Bekh B, Carpenter L, Carr A, Dannlowski U, Dorahy M, Fahlke C, Finzi-Dottan R, Karu T, Gerdner A, Glaesmer H, Grabe HJ, Heins M, Kenny DT, Kim D, Knoop H, Lobbestael J, Lochner C, Lauritzen G, Ravndal E, Riggs S, Sar V, Schäfer I, Schlosser N, Schwandt ML, Stein MB, Subic-Wrana C, Vogel M, Wingenfeld K. Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential: Results from a large, multinational sample using the childhood trauma questionnaire. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146058. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0146058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEdo A, Sherr L, Tomlinson M, Skeen S, Roberts K. Parental bereavement in young children living in South Africa and Malawi: Understanding mental health resilience. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;78(4):390–398. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Kidd M, Seedat S. The effects of childhood maltreatment and anxiety proneness on neuropsychological test performance in non-clinical older adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;243(November 2017):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Viljoen M, Kidd M, Seedat S. Are childhood trauma exposures predictive of anxiety sensitivity in school attending youth? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;168:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rutter M. Retrospective reporting of childhood adversity: Issues in assessing long-term recall. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11(1):19–33. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi, B. M., Lawn, J. E., Van Niekerk, A., Bradshaw, D., Abdool Karim, S. S., & Coovadia, H. M. (2012). Health in South Africa: Changes and challenges since 2009. The Lancet, 380(9858), 2029–2043. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME, Mhlongo EL. Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2015;16(1):81–107. doi: 10.1177/1524838014523336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins, Claude A., & Malee, K. M. (2013). Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: Lessons learned and current challenges. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(Lmic). 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu CS, Elkington KS, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, McKay M, Bamji M, Abrams EJ. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2009;50(9):1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R, Scott J, Alati R, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Strathearn L. Child maltreatment and adolescent mental health problems in a large birth cohort. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2013;37(5):292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes CL, Sampaio PF, Reichenheim ME, da Veiga GV. The intertwined effect of lack of emotional warmth and child abuse and neglect on common mental disorders in adolescence. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2018;83(January):74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell R, Jewkes R, Lindegger G. Hegemonic masculinity/masculinities in South Africa: Culture, power, and gender politics. Men and Masculinities. 2012;15(1):11–30. doi: 10.1177/1097184X12438001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwakanyamale AA, Yizhen Y. Psychological maltreatment and its relationship with self-esteem and psychological stress among adolescents in Tanzania: A community based, cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2139-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöthling J, Suliman S, Martin L, Simmons C, Seedat S. Differences in abuse, neglect, and exposure to community violence in adolescents with and without PTSD and depression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(21–22):4357–4383. doi: 10.1177/0886260516674944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Tubman JG, Burnette ML. Childhood maltreatment histories, alcohol and other drug use symptoms, and sexual risk behavior in a treatment sample of adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(SUPPL. 2):S250–S257. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T, Thompson K, Wekerle C, Al-Hamdani M, Smith S, Hudson A, Goldstein A, Stewart SH. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and coping motives mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and alcohol problems. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(6):918–926. doi: 10.1002/jts.22467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peh CX, Shahwan S, Fauziana R, Mahesh MV, Sambasivam R, Zhang YJ, Ong SH, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2017;67:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Bhana A, Myeza N, Alicea S, John S, Holst H, McKay M, Mellins C. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2010;22(8):970–978. doi: 10.1080/09540121003623693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phasha TN. Educational resilience among African survivors of child sexual abuse in South Africa. Journal of Black Studies. 2010;40(6):1234–1253. doi: 10.1177/0021934708327693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschenberg C, van Os J, Cremers D, Goedhart M, Schieveld JNM, Reininghaus U. Stress sensitivity as a putative mechanism linking childhood trauma and psychopathology in youth’s daily life. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2017;136(4):373–388. doi: 10.1111/acps.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAHO. (2019). Masiphumelele Township, Cape Town | South African History Online. https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/masiphumelele-township-cape-town

- Shamu S, Gevers A, Mahlangu BP, Shai PNJ, Chirwa ED, Jewkes RK. Prevalence and risk factors for intimate partner violence among grade 8 learners in urban South Africa: Baseline analysis from the Skhokho supporting success cluster randomised controlled trial. International Health. 2016;8(1):18–26. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Penner F, Marais L, Skinner D. School connectedness as psychological resilience factor in children affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2018;30(sup4):34–41. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1511045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Bryant-Davis T, Tillman S, Marks A. Stifled voices: Barriers to help-seeking behavior for south african childhood sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2010;19(3):255–274. doi: 10.1080/10538711003781269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Kidd M, Seedat S. A factor analytic study of the childhood trauma questionnaire-short form in an all-female south African sample with and without HIV infection. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2019;92:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. J., Nui. G. F., You. Z. Q., Zhou. Z. K., & Tang, Y. (2017). Gender, negative life events and coping on different stages of depression severity: A cross-sectional study among Chinese university students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 209, 177–181. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- WHO. (2018). WHO | Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). WHO; World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/

- Williams PL, Leister E, Chernoff M, Nachman S, Morse E, Di Poalo V, Gadow KD. Substance use and its association with psychiatric symptoms in perinatally hiv-infected and hiv-affected adolescents. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(5):1072–1082. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9782-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollett N, Cluver L, Bandeira M, Brahmbhatt H. Identifying risks for mental health problems in HIV positive adolescents accessing HIV treatment in Johannesburg. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2017;29(1):11–26. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2017.1283320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Thames A, Simbayi L, Stein DJ, Burns J, Maselesele M. Trauma and mental health in South Africa: Overview. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2017;9(3):249–251. doi: 10.1037/tra0000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]