Abstract

Objectives

To adapt key components of exertional heat stroke (EHS) prehospital management proposed by the Intenational Olympic Committee Adverse Weather Impact Expert Working Group for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 so that it is applicable for the Paralympic athletes.

Methods

An expert working group representing members with research, clinical and lived sports experience from a Para sports perspective reviewed and revised the IOC consensus document of current best practice regarding the prehospital management of EHS.

Results

Similar to Olympic competitions, Paralympic competitions are also scheduled under high environmental heat stress; thus, policies and procedures for EHS prehospital management should also be established and followed. For Olympic athletes, the basic principles of EHS prehospital care are: early recognition, early diagnosis, rapid, on-site cooling and advanced clinical care. Although these principles also apply for Paralympic athletes, slight differences related to athlete physiology (eg, autonomic dysfunction) and mechanisms for hands-on management (eg, transferring the collapsed athlete or techniques for whole-body cooling) may require adaptation for care of the Paralympic athlete.

Conclusions

Prehospital management of EHS in the Paralympic setting employs the same procedures as for Olympic athletes with some important alterations.

Keywords: disabled persons, body temperature regulation, hot temperature, wheelchair, athletes

Introduction

With the increasing knowledge in the clinical management of heat-related illnesses, development of specific guidelines and protocols to treat exertional heat stroke (EHS) and other heat-related conditions are becoming readily available.1–3 These documents are of high relevance considering global warming, the increasing number of mass participation events that take place in extreme environments and the increasing number of participants of all competitive levels engaging in these events. Although elite athletes, including Paralympic athletes, are more likely to be better prepared for competing in the heat (ie, heat acclimatisation, pre-cooling and par-cooling) the medical care provided in elite events follow the same principles as those applied at mass participation events. The environmental conditions at the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games have raised concerns among teams, organisers and the scientific community due to the expected high temperatures and relative humidity, based on the recent trends and reports.4 In this context, a new set of guidelines for prehospital management of EHS at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games was recently published, focusing on the medical care and logistical set up required to provide high-quality care at the sporting venue.3 Although the clinical management of EHS in athletes competing in Para sport may adopt the same principles, there are substantial differences that should be taken into consideration when organising prehospital management strategies.

Athletes at the Paralympic Games are classified into 10 impairment types (eight physical impairments as well as visual and intellectual impairments) resulting in a heterogeneous athlete population. The available evidence indicates that the incidence of EHS in the Paralympic athlete population is low.5–7 Nonetheless, some Paralympic athletes across the spectrum of eligible impairments are inherently at greater risk of thermoregulatory strain during exercise in the heat (table 1). As such, heat syncope/exhaustion are still possible, and clinicians must be prepared to manage these athletes appropriately at the Paralympic Games and other events globally. Additionally, given the ever-increasing standard and professionalism of Paralympic sports (eg, 124 Paralympic records were broken during the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics) and the trend towards international events being staged in hot and/or humid environments and the increased prevalence of foreseen heatwaves,8 including the 2024 venue in Paris and 2028 venue in Los Angeles, the prevalence of EHS will likely increase over time.

Table 1.

Examples of medical condition specific to Paralympic athletes in relation to thermoregulation

| Diagnosis | Thermoregulation considerations for in-competition performance | Para sport | Reporting of heat-related illness/ symptoms |

| Spinal cord-related disorders |

|

Wheelchair Rugby Para Athletics Para Archery Paratriathlon |

Heat-related disorientation29

Convulsion5 Heat-related fatigue22 Heat-related illness30 |

| Non-spinal cord-related neurological disorders |

|

Para Athletics Paratriathlon |

Heat exhaustion5

Heat-related illness5 Heat-related illness30 |

| Limb deficiency |

|

Para Athletics Paratriathlon |

Cramps and collapse5

Heat exhaustion5 Heat-related illness5 Heat-related illness30 |

| Visual impairment |

|

Para Athletics Paratriathlon |

Dermatological burn5

Heat exhaustion5 Heat-related illness5 Heat-related illness30 |

Grobler et al 5 competitive athletics taking place in wet-globe temperatures 24.6–36.0°C; Griggs et al 29 wheelchair rugby match play at 18.4–20.9°C and 31.1%–45.1% relative humidity; Handrakis et al 22 competitive archery outdoors for 10 hours (conditions not reported); Stephenson et al 30 competitive paratriathlon in 33°C relative humidity 35%–41%. The reader is guided to Westaway et al 43 for lists of medications that can interfere with thermoregulation, dehydration and heat-related illness.

Adapted from Stephenson and Goosey-Tolfrey44 and evidence of heat-related illness reported in Paralympic sports.3 16–18

Tc, body core temperature; Tsk, skin temperature.

EHS prehospital care overview

Basic components of EHS prehospital care include: (1) early recognition, (2) early diagnosis, (3) rapid, on-site cooling and (4) advanced clinical care.3 Unlike other sports-related medical emergency (eg, spinal injury, brain trauma, complex fracture), EHS requires the treatment to be completed on-site first, before the patient is transported to the advanced care.9 This is due to the fact that the duration of sustained hyperthermia is known to dictate patient prognosis.10 A delay in appropriate recognition, diagnosis and cooling can lead to catastrophic outcome.11 12 Current clinical best practice suggests that EHS patients must be cooled until their core body temperature is below 39°C within 30 min of the onset.3 Therefore, it becomes critical that medical providers working at sporting events with risk of EHS are well equipped with skills and resources to execute (1) rectal temperature assessment to confirm the diagnosis, (2) rapid cooling using whole-body cold-water immersion and (3) follow-up examination to assess discharge readiness.

When possible, it may be of benefit to acquire the athlete’s medical history and ongoing therapy prior to the event since impairment type indicated by the competition class does not necessarily represent whether the athlete is predisposed to increase thermoregulatory strain. For example, eligibility in the Quad class of wheelchair tennis is not restricted to athletes with tetraplegia. Consequently, a player with a spinal cord injury at the C8 level or above versus a player with an upper limb myopathy will both be eligible, but the former is at higher risk for exertional heat illness. If personal medical information cannot be acquired due to medical privacy reasons, organisers of the event are advised to request participating athletes and staff to report any foreseeable heat-related issues prior to the day of the competition. Some of the key questions to ask include: (1) presence of thermoregulatory impairment and the reason, (2) history of exertional heat illness, (3) baseline blood pressure, if lower than the reference value and (4) any intake of medication that may alter the interpretation of vital signs.

Heat deck/medical tent

Heat deck set-up and transfer of patient from field of play to medical tent

Heat deck, a designated area for EHS treatment and management, should be located within or adjacent to the main athlete medical tent. When the sport of interest involves Paralympic athletes, who compete in wheelchair sports (eg, wheelchair racing), the space within and corridor to the medical tent must be designed to accommodate the width of varying sports wheelchairs. Securing a clean water source, ice and appropriate drainage is at high priority to manage cold water immersion tubs.

Once the Paralympic athlete is suspected of experiencing EHS at the field of play, the athlete should be transferred directly to heat deck. Medical personnel assigned to work at Paralympic events should be familiar with transfer techniques of athletes with different impairments, particularly the collapsed athlete. Manual lifting in healthcare training programmes and policies are encouraged to prevent musculoskeletal injuries to the volunteers by athlete handling.13 14 If the Paralympic athlete collapses while in sports equipment (eg, sports wheelchair, handcycle), carefully extricate the athlete from their equipment. Therefore, prior familiarisation with equipment and strapping used by athletes is important.

Management of medical tent traffic

Given the complexity of managing emergency medical conditions in Paralympic athletes, it is important that a team representative who knows the athlete well is allowed to enter the heat deck during EHS management. This will allow the team representative to provide impairment-specific information (including medications and therapeutic use exemption considerations) to the management team, which may assist in the selection of prehospital care procedures. For athletes with visual impairment, their guide should have a guaranteed entry to the medical tent to provide assistance in the care of the athlete. Furthermore, athletes with communication disability (eg, dysarthria) should be allowed to have their team representative accompany the athlete to facilitate communication throughout treatment, and to ensure that the athlete has returned to baseline mental status prior to discharge.

Patient assessment

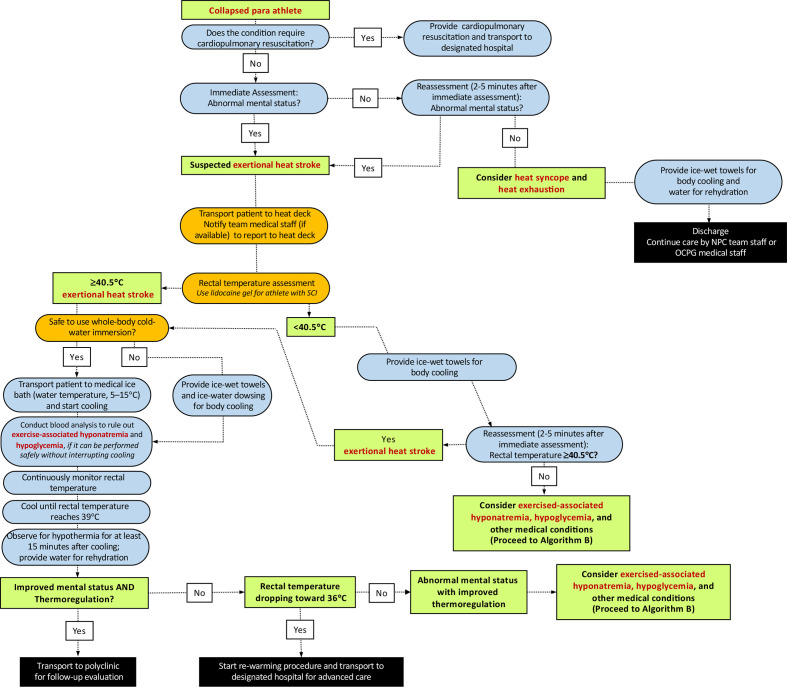

The general principles of prehospital EHS management in Paralympic athletes do not differ greatly from the standard care used in the general athletic context (figure 1). We encourage readers to review the paper by Hosokawa et al for an overview of the fundamental concepts.3

Figure 1.

Algorithm (A1) for the initial diagnosis and management of a Paralympic athlete with suspected exertional heat stroke who has no risk of autonomic dysreflexia. NPC, National Paralympic Committee; OCPG, Organising Committees for the Paralympic Games; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Rectal temperature should be assessed using a flexible probe to identify the extent of exercise-induced hyperthermia. If the collapsed athlete’s impairment is in the category of spinal cord injury at or above T6, heart rate and blood pressure should be checked immediately, and then monitored for signs of autonomic dysreflexia (AD) (table 2). These athletes are also at higher risk for impaired thermoregulation (eg, overheating/EHS or overshoot during cooling). When assessing the rectal temperature of athletes with spinal cord injury at or above T6, lidocaine gel should be used to prevent the risk of AD. However, such risk is minimal given this task constitutes only a brief, transient noxious stimulus. In relation to AD, medical providers should also consider bowel and bladder distension as the cause of AD (as EHS is unlikely to be the direct cause of AD). The induction of AD can have major implications on heart rate and blood pressure (elevations) leading to a dangerous condition. The reader is guided to Blauwet et al 15 for further guidance.

Table 2.

Overview of the 22 sporting events at Tokyo Paralympic Games and the sports/events where athletes are at risk for autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and impaired thermoregulation with a spinal cord injury at or above the level T6

| Sports | Spinal cord-related disorders | Above or at SCI level T6 | Environmental heat stress | Event and class |

| Archery | ☑ | ☑ | Moderate | W1 |

| Athletics | ☑ | ☑ | High | WR track T51–T53 Seated throws F51–F53 |

| Badminton | ☑ | ☑ | Low | WH1 |

| Boccia | ☑ | ☑ | Low | BC1 |

| Canoe | ☑ | ☑ | Low | Kayak KL1 |

| Cycling | ☑ | ☑ | High | Handcycling H1 |

| Equestrian | ☑ | □ | Moderate | – |

| Football (5-a-side) | □ | □ | Moderate | – |

| Goalball | □ | □ | Low | – |

| Judo | □ | □ | Low | – |

| Powerlifting | ☑ | □ | Low | – |

| Rowing | ☑ | ☑ | Moderate | AS |

| Shooting | ☑ | ☑ | Moderate | Rifle SH2 |

| Sitting volleyball | ☑ | ☑ | Low | – |

| Swimming | ☑ | ☑ | Low | S1 SB1 and S2 SB1 |

| Table tennis | ☑ | ☑ | Low | Class 1 |

| Taekwondo | □ | □ | Low | – |

| Triathlon | ☑ | ☑ | High | PTWC |

| Wheelchair basketball | ☑ | □ | Moderate | – |

| Wheelchair fencing | ☑ | □ | Low | – |

| Wheelchair rugby | ☑ | ☑ | High | Typically, 0.5 and 1.0 |

| Wheelchair tennis | ☑ | ☑ | High | Quad class |

Before moving the athlete to whole-body cold-water immersion tub, assessment for pressure sores, open wounds and local burns should also be conducted thoroughly, which may be more prevalent in amputee athletes and athletes with insensate regions (paraplegia and tetraplegia). If open wounds are present, cover the area with an appropriately disinfected or new cold-water immersion tub to avoid the risk of contamination. It should be noted that these steps must be taken expeditiously to avoid unnecessary delays in care.

Whole body cold-water immersion

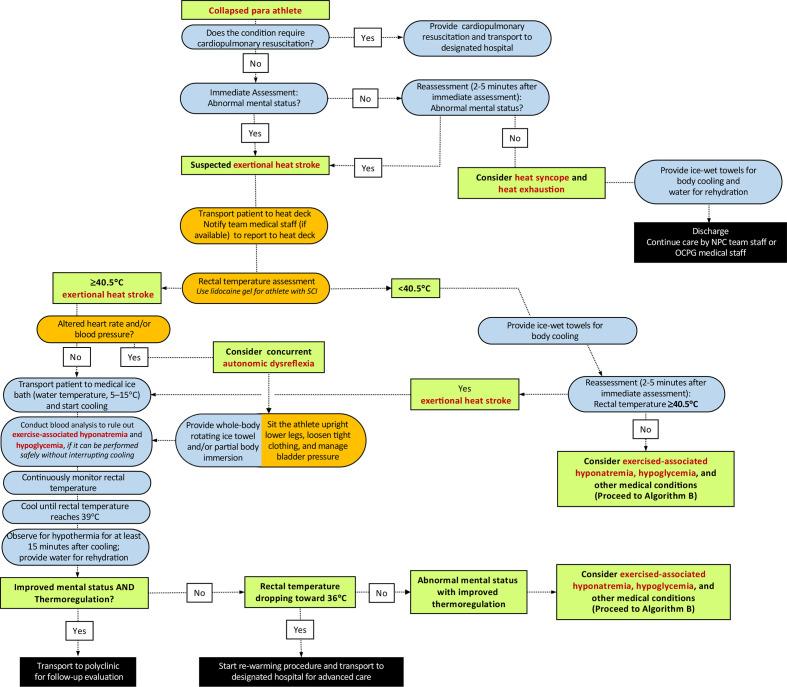

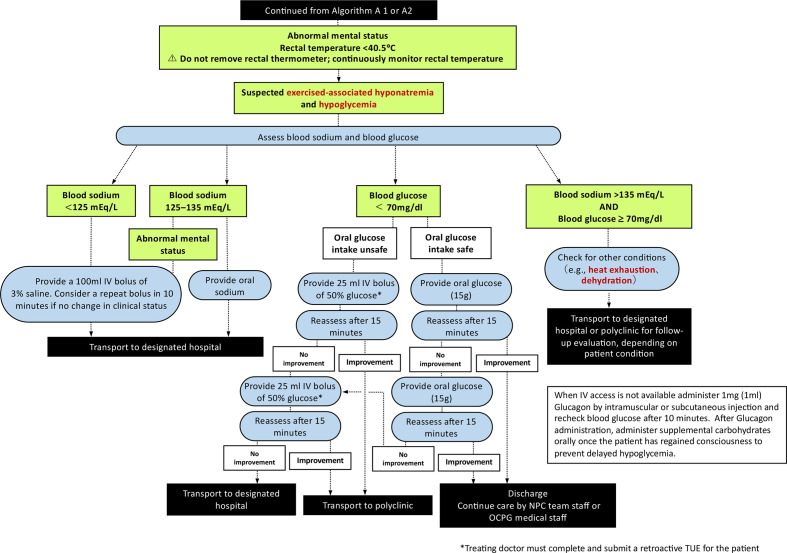

Medical providers must continuously monitor rectal temperature throughout the cooling process to determine the end point of treatment (ie, rectal temperature reaches 39.0°C) (figures 1–3). Clinicians should be reminded that inserting a rectal thermometer with proper technique (ie, use of lidocaine gel) is unlikely to cause AD. The immersion tub size should be selected accordingly to the average body size of the participants. An immersion tub that is traditionally used for the purpose of recovery ice bath may not be suitable for EHS treatment as it may be too deep for medical providers to transfer the collapsed athlete in and out from the bath and has the risk of drowning (readers are referred to Hosokawa et al for sample size of the immersion tub).3 The use of a pole-less stretcher to transfer the Paralympic athlete in and out of the tub may have increased importance than Olympic athletes since manual handling and moving patients who have mobility limitations requires some practice. If an athlete with amputation experiences EHS and needs to be cooled, the prosthesis should be removed prior to immersion (or whenever possible, if it can be done safely) to maximise the skin surface to be cooled. In some cases, there will be a connection or interface device (commonly made of silicone), which should be removed to maximise the skin surface area to be cooled. In rare circumstances, where it is not safe to employ whole-body cold-water immersion (ie, athletes with known intellectual impairments who are not compliant to treatment measures), medical providers may choose whole-body rotating ice towels and/or ice water dousing as an alternative option, as these cooling methods have been shown to have adequate cooling rates.16 Tarp-assisted cooling (TACo) is another alternative cooling technique used to treat EHS.17 However, in the case where whole-body cold-water immersion is deemed unsafe, it is unlikely that the TACo method can be administered safely since it also involves significant patient transfer. Among a small group of Paralympic athletes at risk of AD (ie, spinal cord injury at or above T6), transfer and change in the positioning of the patient should be minimised as much as possible to prevent noxious inputs that could trigger AD. In such situations, medical providers may consider using a mix of whole-body rotating ice towels and partial body immersion (ie, entire upper extremity) (figure 2). The reader is directed to the work of Griggs et al 18 and Pritchett et al 19 for more practical guidance. It should be emphasised that reduction of internal body temperature within the initial 30 min of collapse ensures survival and minimises the severity of sequela.20

Figure 2.

Algorithm (A2) for the initial diagnosis and management of a Paralympic athlete with suspected exertional heat stroke who has potential risk of autonomic dysreflexia and impaired thermoregulation (ie, individuals with spinal cord injury at T6 or above). NPC, National Paralympic Committee; OCPG, Organising Committees for the Paralympic Games; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Figure 3.

Algorithm (B) for the management of an athlete with exertional heat stroke (continued from figures 1 and 2). When intravenous access is not available administer 1 mg (1 mL) Glucagon by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection and recheck blood glucose after 10 min. After Glucagon administration, administer supplemental carbohydrates orally once the patient has regained consciousness to prevent delayed hypoglycaemic. NPC, National Paralympic Committee; OCPG, Organising Committees for the Paralympic Games.

Finally, a laboratory study suggests that the risk of hypothermic overshoot may be more pronounced among athletes with impaired thermoregulation (eg, athletes with a spinal cord injury).21 Medical providers should monitor the rate of cooling closely as it may be faster compared with athletes with no disability.22 23

Hygiene-related considerations

Consider stump hygiene and skin health of athletes with a limb deficiency, particularly of the lower limb. While the residual limb may display skin irritation, if whole-body cold-water immersion is the preferred option, then ensure that once the prosthesis is removed, the area is fully dried post-immersion and cleansed to prevent infection.

Athletes with colostomy bags should still be cooled using whole-body cold-water immersion to prioritise life-saving procedure; however, whole-body cold-water immersion tub used to cool athletes with colostomy bag should be drained and disinfected after each use. If available, consider designating a large shower room (ie, such as those seen in sports arenas and locker rooms) where running water can be used to also cleanse the athlete while protecting privacy.

Post-treatment

There are currently no Para-athlete specific considerations for post-EHS treatment follow-up in the athlete medical tent. It is recommended that the need for specific testing be left to the team physician rather than medical tent team due to the wide variety of medical complications in Paralympic athletes.

Conclusion

Prehospital management of EHS in the Paralympic setting employs the same procedures as for an Olympic athlete with some important alterations. These include additional preparations to assist transport of Para-athletes with mobility equipment, planning for alternative whole-body cooling methods if cold water immersion is deemed unsafe, and extra precautions and monitoring for athletes at risk of AD. We hope that event and team medical practitioners and Para athletes themselves are familiar with the prehospital management of EHS, since global warming poses a significant risk to Para sport competitions in the future.

What are the findings?

The incidence of exertional heat stroke (EHS) is relatively low among Paralympic athletes, but with increased global warming and interest to host world stage events in hot and humid environments the risk of EHS in Paralympic athletes may increase over time.

Medical providers are advised to review participating athletes’ impairment classification and categories prior to the event in order to apply impairment-specific considerations to safely treat Paralympic athletes with suspected EHS.

Paralympic athletes with autonomic dysfunction may experience altered thermoregulation, putting them at higher risk of EHS, as well as hypothermic overshoot during cold water immersion.

Athletes with significant mobility disability with suspected EHS may warrant whole-body cooling options other than cold water immersion to ensure safety and ease of care.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the future?

While the core principles of prehospital management of EHS for Paralympic athletes are no different from the standard care used in the general athletic context, extra caution may be required regarding specific physiological differences (eg, autonomic dysfunction) that impact the management of the altered or collapsed athlete.

Due to the heterogeneous athlete population, a thorough knowledge and awareness of the physiological and thermoregulatory responses in Paralympic athletes is required to optimise medical services at sporting events.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marco Bernardi, Sergio Migliorini, Yoshi Kamijo, Fumihiro Tajima, Michelle Trbovich for their expert opinion and support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @paolo_emilio, @bstephenson311, @SportswiseUK, @ephysiol, @wderman

Contributors: YH, PEA, SB and VLG-T contributed to the conception or design of the work. YH, PEA and VLG-T drafted the manuscript. YH, PEA, BTS, CB, SB, NW, SR, WD and VLG-T critically revised the manuscript. All gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: WD reports grants from IOC Research Centers Grant, other from IPC Travel Support, grants from World Rugby, grants from AXA, grants from Ossur, outside the submitted work.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Belval LN, Casa DJ, Adams WM, et al. Consensus Statement- prehospital care of exertional heat stroke. Prehosp Emerg Care 2018;22:392–7. 10.1080/10903127.2017.1392666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casa DJ, DeMartini JK, Bergeron MF, et al. National athletic trainers' association position statement: exertional heat illnesses. J Athl Train 2015;50:986–1000. 10.4085/1062-6050-50.9.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hosokawa Y, Racinais S, Akama T. Prehospital management of exertional heat stroke at sports Competitions: international Olympic Committee adverse weather impact expert Working group for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020. Br J Sports Med 2021. [Epub ahead of print: 22 Apr 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matzarakis A, Fröhlich D, Bermon S, et al. Quantifying thermal stress for sport Events—The case of the Olympic Games 2020 in Tokyo. Atmosphere 2018;9:479. 10.3390/atmos9120479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grobler L, Derman W, Racinais S, et al. Illness at a para athletics track and field world championships under hot and humid ambient conditions. Pm R 2019;11:919–25. 10.1002/pmrj.12086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Griggs KE, Stephenson BT, Price MJ, et al. Heat-Related issues and practical applications for Paralympic athletes at Tokyo 2020. Temperature 2020;7:37–57. 10.1080/23328940.2019.1617030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y, Bishop PA. Risks of heat illness in athletes with spinal cord injury: current evidence and needs. Front Sports Act Living 2019;1:68. 10.3389/fspor.2019.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ouzeau G, Soubeyroux J-M, Schneider M, et al. Heat waves analysis over France in present and future climate: application of a new method on the EURO-CORDEX ensemble. Climate Services 2016;4:1–12. 10.1016/j.cliser.2016.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Lee EC, et al. Cold water immersion: the gold standard for exertional heatstroke treatment. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2007;35:141–9. 10.1097/jes.0b013e3180a02bec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Epstein Y, Yanovich R. Heatstroke. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2449–59. 10.1056/NEJMra1810762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grundstein A, Knox JA, Vanos J, et al. American football and fatal exertional heat stroke: a case study of Korey Stringer. Int J Biometeorol 2017;61:1471–80. 10.1007/s00484-017-1324-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stearns RL, Casa DJ, O'Connor FG, et al. A tale of two heat strokes: a comparative case study. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016;15:94–7. 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fadul RM, Brown LM, Powell-Cope G. Improving transfer task practices used with air travelers with mobility impairments: a systematic literature review. J Public Health Policy 2014;35:26–42. 10.1057/jphp.2013.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hallmark B, Mechan P, Shores L. Ergonomics: safe patient handling and mobility. Nurs Clin North Am 2015;50:153–66. 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blauwet CA, Benjamin-Laing H, Stomphorst J, et al. Testing for boosting at the Paralympic games: policies, results and future directions. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:832–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDermott BP, Casa DJ, Ganio MS, et al. Acute whole-body cooling for exercise-induced hyperthermia: a systematic review. J Athl Train 2009;44:84–93. 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hosokawa Y, Adams WM, Belval LN, et al. Tarp-Assisted cooling as a method of whole-body cooling in hyperthermic individuals. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:347–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griggs KE, Price MJ, Goosey-Tolfrey VL. Cooling athletes with a spinal cord injury. Sports Med 2015;45:9–21. 10.1007/s40279-014-0241-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pritchett K, Broad E, Scaramella J. Hydration and cooling strategies for Paralympic athletes : applied focus. Challenges athletes may face at the upcoming Tokyo Paralympics. Curr Nutr Rep 2020;9:137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Demartini JK, Casa DJ, Stearns R, et al. Effectiveness of cold water immersion in the treatment of exertional heat stroke at the Falmouth road race. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:240–5. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Scheer JW, Kamijo Y-I, Leicht CA, et al. A comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation during mild whole-body cold stress in individuals with and without cervical spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Spinal Cord 2018;56:469–77. 10.1038/s41393-017-0021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Handrakis JP, Trbovich M, Hagen EM, et al. Thermodysregulation in persons with spinal cord injury: case series on use of the autonomic standards. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2017;3:1–8. 10.1038/s41394-017-0026-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheshire WP. Thermoregulatory disorders and illness related to heat and cold stress. Auton Neurosci 2016;196:91–104. 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Freund PR, Brengelmann GL, Rowell LB, et al. Attenuated skin blood flow response to hyperthermia in paraplegic men. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1984;56:1104–9. 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.4.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Normell LA. Distribution of impaired cutaneous vasomotor and sudomotor function in paraplegic man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl 1974;138:25–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hopman MT, Oeseburg B, Binkhorst RA. Cardiovascular responses in paraplegic subjects during arm exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1992;65:73–8. 10.1007/BF01466277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Graham-Paulson T, Perret C, Goosey-Tolfrey V. Case study: dose response of caffeine on 20-km handcycling time trial performance in a paratriathlete. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018;28:274–8. 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griggs KE, Havenith G, Price MJ, et al. Evaporative heat loss insufficient to attain heat balance at rest in individuals with a spinal cord injury at high ambient temperature. J Appl Physiol 2019;127:995–1004. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00893.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griggs KE, Havenith G, Price MJ, et al. Thermoregulatory responses during competitive wheelchair rugby match play. Int J Sports Med 2017;38:177–83. 10.1055/s-0042-121263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stephenson BT, Hoekstra SP, Tolfrey K, et al. High thermoregulatory strain during competitive paratriathlon racing in the heat. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2020;15:231–7. 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maltais D, Wilk B, Unnithan V, et al. Responses of children with cerebral palsy to treadmill walking exercise in the heat. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:1674–81. 10.1249/01.mss.0000142312.43629.d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kloyiam S, Breen S, Jakeman P, et al. Soccer-specific endurance and running economy in soccer players with cerebral palsy. Adapt Phys Activ Q 2011;28:354–67. 10.1123/apaq.28.4.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Runciman P, Tucker R, Ferreira S, et al. Paralympic athletes with cerebral palsy display altered pacing strategies in distance-deceived shuttle running trials. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016;26:1239–48. 10.1111/sms.12575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Christogianni A, Bibb R, Davis SL, et al. Temperature sensitivity in multiple sclerosis: an overview of its impact on sensory and cognitive symptoms. Temperature 2018;5:208–23. 10.1080/23328940.2018.1475831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allen DR, Huang MU, Morris NB, et al. Impaired thermoregulatory function during dynamic exercise in multiple sclerosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:395–404. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Epstein Y, Shapiro Y, Brill S. Role of surface area-to-mass ratio and work efficiency in heat intolerance. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1983;54:831–6. 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.3.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klute GK, Rowe GI, Mamishev AV, et al. The thermal conductivity of prosthetic sockets and liners. Prosthet Orthot Int 2007;31:292–9. 10.1080/03093640601042554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crandall CG, Davis SL. Cutaneous vascular and sudomotor responses in human skin grafts. J Appl Physiol 2010;109:1524–30. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00466.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mengelkoch LJ, Kahle JT, Highsmith MJ. Energy costs & performance of transtibial amputees & non-amputees during walking & running. Int J Sports Med 2014;35:1223–8. 10.1055/s-0034-1382056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor JB, Santi G, Mellalieu SD. Freestyle race pacing strategies (400 m) of elite able-bodied swimmers and swimmers with disability at major international championships. J Sports Sci 2016;34:1913–20. 10.1080/02640414.2016.1142108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Webborn N, Van de Vliet P. Paralympic medicine. Lancet 2012;380:65–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60831-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bothwell JE. Pigmented skin lesions in tyrosinase-positive oculocutaneous albinos: a study in black South Africans. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:831–6. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Westaway K, Frank O, Husband A, et al. Medicines can affect thermoregulation and accentuate the risk of dehydration and heat-related illness during hot weather. J Clin Pharm Ther 2015;40:363–7. 10.1111/jcpt.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stephenson B, Goosey-Tolfrey VL. Physiological considerations for paratriathlon training and competition. In: Migliorini S, ed. Triathlon medicine. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020: 393–415. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.