Abstract

Rice is one of the main food crops for the world population. Various abiotic stresses, such as low temperature, drought, and high salinity, affect rice during the entire growth period, determining its yield and quality, and even leading to plant death. In this study, by constructing overexpression vectors D-163 + 1300:OsSCL30 and D-163 + 1300-AcGFP:OsSCL30-GFP, the mechanism of action of OsSCL30 in various abiotic stresses was explored. Bioinformatics analysis showed that OsSCL30 was located on the chromosome 12 of rice Nipponbare, belonging to the plant-specific SCL subfamily of the SR protein family. The 1500 bp section upstream of the open reading frame start site contains stress-related cis-acting elements such as ABRE, MYC, and MYB. Under normal conditions, the expression of OsSCL30 was higher in leaves and leaf sheaths. The results of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction showed that the expression of OsSCL30 decreased after low temperature, drought and salt treatment. In root cells OsSCL30 was localized in the nuclei. The results of the rice seedling tolerance and recovery tests showed that overexpression of OsSCL30 diminished the resistance to low temperature, drought and salt stresses in transgenic rice and resulted in larger accumulation of reactive oxygen species. This study is of great significance for exploring the response mechanisms of SR proteins under abiotic stresses.

Subject terms: Physiology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the main food crops, and about 50% of the world’s population depends on rice as the staple food1,2. Plants may encounter various abiotic stresses during their growth and development, among which low temperature, drought and salinity are common stress conditions that determine their yield and quality, and may even lead to plant death3–6. Rice, when subjected to abiotic stresses, responds and adapts at the molecular, cellular, biochemical and physiological levels to survive under stress conditions7–9.

A family of serine/arginine (SR) -rich proteins plays important roles in both constitutive and alternative splicing by binding to specific RNA sequences and assembling spliceosomes at weakly spliced sites for alternative splicing10–12. The sequence feature of the canonical SR protein family is the presence of one or two N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs), followed by a serine/arginine-rich repeat domain of at least 50 amino acids. The arginine/serine (RS) or SR repeats are characterized by an RS content greater than 40%. Stresses such as low temperature, high temperature, and drought regulate the splicing pattern, phosphorylation state, and subcellular distribution of SR proteins in plants13. The SR proteins of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and brachypodium (Brachypodium distachyon) are similar to the rice SR proteins and can be widely expressed. In the promoter regions of SR protein genes of wheat and brachypodium, 92 cis-elements related to plant growth and development, stress and hormone were found, indicating that SR proteins play an important role in plant growth and development and stress response14–17.

Low temperature stress is a major limiting factor for rice growth and geographic distribution, affecting both vegetative and reproductive stages, influencing seed germination, seedling growth, plant height, photosynthesis, heading date, and fertility18–20. Many transcription factors (TFs) play a role in low temperature stress, such as MYB4, MYBS3, OsNAC5, and OsbZIP7321–23. Three rice CBF gene family members (OsCBF1, OsCBF2, and OsCBF3) were up-regulated under low temperature stress24, these three CBF proteins are the major transcriptional activators required for cold-induced gene expression25. Rice has at least four DREB2 homologous genes, of which OsDREB2A and OsDREB2B are induced by drought, high salt and high temperature stresses. The expression of OsDREB2B is regulated by alternative splicing, resulting in two types of transcripts: functional and non-functional forms26.

The role of SR proteins in plant growth, development and stress response has been studied. For example, the SCL30a from cassava (Manihot esculenta) overexpressed in Arabidopsis negatively regulates salt tolerance27; and deletion of SR45 in Arabidopsis results in enhancing sensitivity to salt stress and altering the expression and splicing of genes which regulate salt stress response28. Currently, rice growth is affected by environmental stresses such as salinity, drought, and extreme temperature. Therefore, it is of great significance to understand the response of SR proteins in rice under abiotic stress. In the present study, the results showed that overexpression of OsSCL30 diminished the resistance to low temperature, drought and salt in transgenic rice.

Results

Bioinformatics analysis of OsSCL30

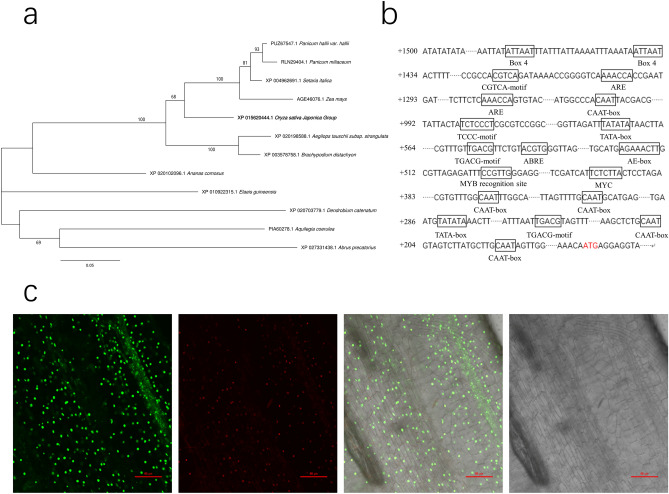

The OsSCL30 gene is located on rice chromosome 12, with an open reading frame of 792 bp, encoding 263 amino acids. It belongs to the plant-specific SCL subfamily of the SR protein family. In order to understand the relationship of OsSCL30 sequences among different species, the species with high amino acid sequence similarity were selected for cluster analysis. The OsSCL30 was found to be clustered with panicgrass (Panicum hallii), broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), millet (Setaria italica), and maize (Zea mays), with a strong genetic relationship (Fig. 1a). Using the PlantCARE online website to analyze about 1500 bp upstream of ATG, it was found that the promoter of the OsSCL30 gene contains various elements related to stress response (Fig. 1b). These elements include ABRE (ABA responsive element), G-box (light-responsive element), TGA-element (auxin-responsive element), GCN4_motif (involved in endosperm expression), TC-rich repeats (involved in defense and stress response), MYB (drought-related response element), etc.

Figure 1.

(a) Cluster analysis of OsSCL30 homologous genes in plants. (b) Analysis of elements associated with the OsSCL30 promoter region. (c) Subcellular localization of OsSCL30-GFP.

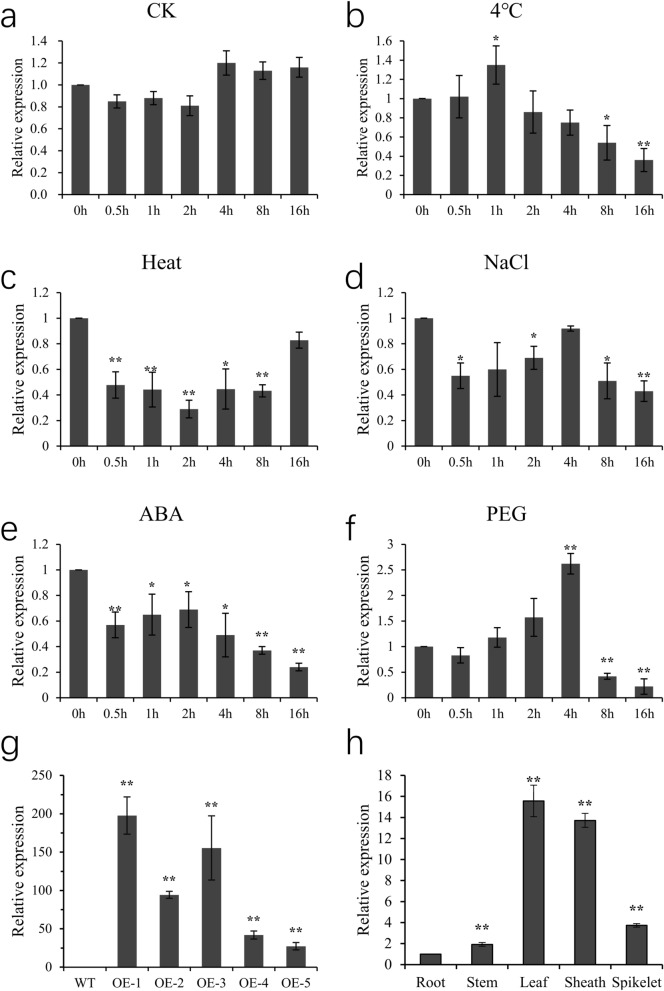

Relative expression of OsSCL30

In order to select overexpressed lines for subsequent experiments, the expression level of OsSCL30 was detected by qRT-PCR. The results (Fig. 2g) showed that compared with WT, the expression levels of OE-1 and OE-3 were up-regulated the most, which were 197 times and 155 times, respectively. Therefore, OE-1 and OE-3 were selected as the subsequent experimental lines.

Figure 2.

(a–f) OsSCL30 gene expression pattern under various environmental stresses and ABA treatment. (a. ck; b. 4 °C; c. 42 °C; d. 150 mM NaCl; e. 50 μM ABA; f. 15% w/v PEG) (g) OsSCL30 transgenic lines expression detection. (h) Tissue expression of OsSCL30. Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

To detect the tissue-specific expression pattern of OsSCL30 gene, different untreated tissues (root, stem, leaf, sheath and spikelet) were collected, and the expression level of OsSCL30 in different tissues was detected by qRT-PCR. The results (Fig. 2h) showed the expression of OsSCL30 was highest in leaves, followed by leaf sheaths.

OsSCL30 is activated by abiotic stress

Because a variety of stress response factors were found in the promoter of OsSCL30, different stresses were applied to rice seedlings, and the expression level of OsSCL30 was detected by qRT-PCR. The results showed that the expression level of OsSCL30 in the control group was similar to the initial value during the whole process (Fig. 2a). The expression of OsSCL30 increased briefly after the low temperature treatment was imposed, rising to the highest level at 1 h, and then gradually decreased (Fig. 2b). The change in the whole period was not significant. The expression of OsSCL30 began to decrease immediately after imposition of the high temperature treatment, decreasing to a minimum at 2 h, and then gradually increased, but was lower than the initial value throughout the treatment (Fig. 2c). Under salt stress, the expression of OsSCL30 decreased significantly, then increased with the treatment duration, reaching the maximum at 4 h and then began to decrease, but the expression was lower than the initial value during the whole treatment duration (Fig. 2d). Under exogenous ABA treatment, the expression level of OsSCL30 was similar to that under salt treatment (Fig. 2e). After 0.5 h of drought treatment, the expression of OsSCL30 decreased briefly, then increased gradually, reaching a peak at 4 h, and then decreased sharply with prolonged treatment duration (Fig. 2f). In summary, various abiotic stresses can reduce the expression of OsSCL30 gene; among them, drought stress has the greatest impact on the OsSCL30 expression.

Subcellular localization of OsSCL30

The WOLF PSORT online website predicts that the OsSCL30 protein is localized in the nucleus. To further examine the subcellular localization of OsSCL30 protein in rice, the roots of transgenic rice plants OsSCL30-GFP were stained with DAPI and observed by confocal microscopy. The results showed that the GFP signal of the SCL30-GFP fusion protein was visible only in the nucleus, consistent with the prediction (Fig. 1c). Hence, we concluded OsSCL30 protein was localized in the nucleus of rice.

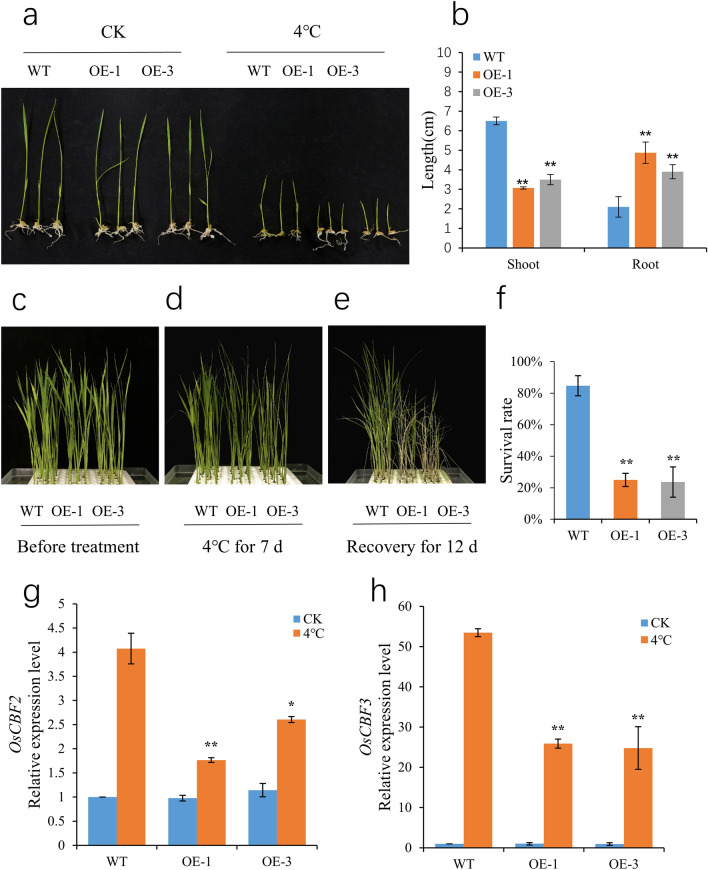

Overexpression of OsSCL30 attenuates low temperature resistance in transgenic rice

To verify the response of OsSCL30 overexpression to low temperature stress, we cultured 5-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpression lines (OE-1, OE-3) at 4 °C for 3 days followed by 7-day recovery. The results showed that the growth of OsSCL30-OE was similar to that of WT seedlings under normal growth conditions, but low temperature inhibited the growth of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (Fig. 3a). The plant height of OsSCL30-OE seedlings after low temperature treatment was significantly shorter than that of WT, but the root length was significantly longer than that of WT (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Effects of cold stress in wild type (WT) and OE lines. (a) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines under 4 °C for 3 days. (b) Plant height and root length of WT and OE lines treated at 4 °C for 3 days. (c) Phenotype of WT and OE lines hydroponically cultivated for 14 days (before imposition of the cold stress). (d) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines treated for 7 days at 4 °C. (e) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines after 12 days recovery following the 4 °C treatment. (f) Survival of recovered WT and OE lines. (g–h) The expression levels of OsCBF2 and OsCBF3 were analyzed after two days of treatment at 4 °C, respectively. Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

We cultured 14-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) at 4 °C for 7 days and then allowed them to recover for 12 days. The wilting of OsSCL30-OE seedlings after low temperature treatment was more severe than that of WT (Fig. 3d). After the recovery period, the survival rate of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (24–25% for the two lines) was significantly lower than that of WT (85%) (Fig. 3e–f).

In order to clarify the regulatory pathway of OsSCL30, we detected the expression of important genes in the cold response pathway of OsSCL30 overexpressed plants. The results showed that the core components of rice ICE-CBF pathway29, including OsCBF2 and OsCBF3, were down regulated in OsSCL30-OE compared with WT (Fig. 3g–h). In conclusion, overexpression of OsSCL30 reduced the low temperature resistance of transgenic rice plants.

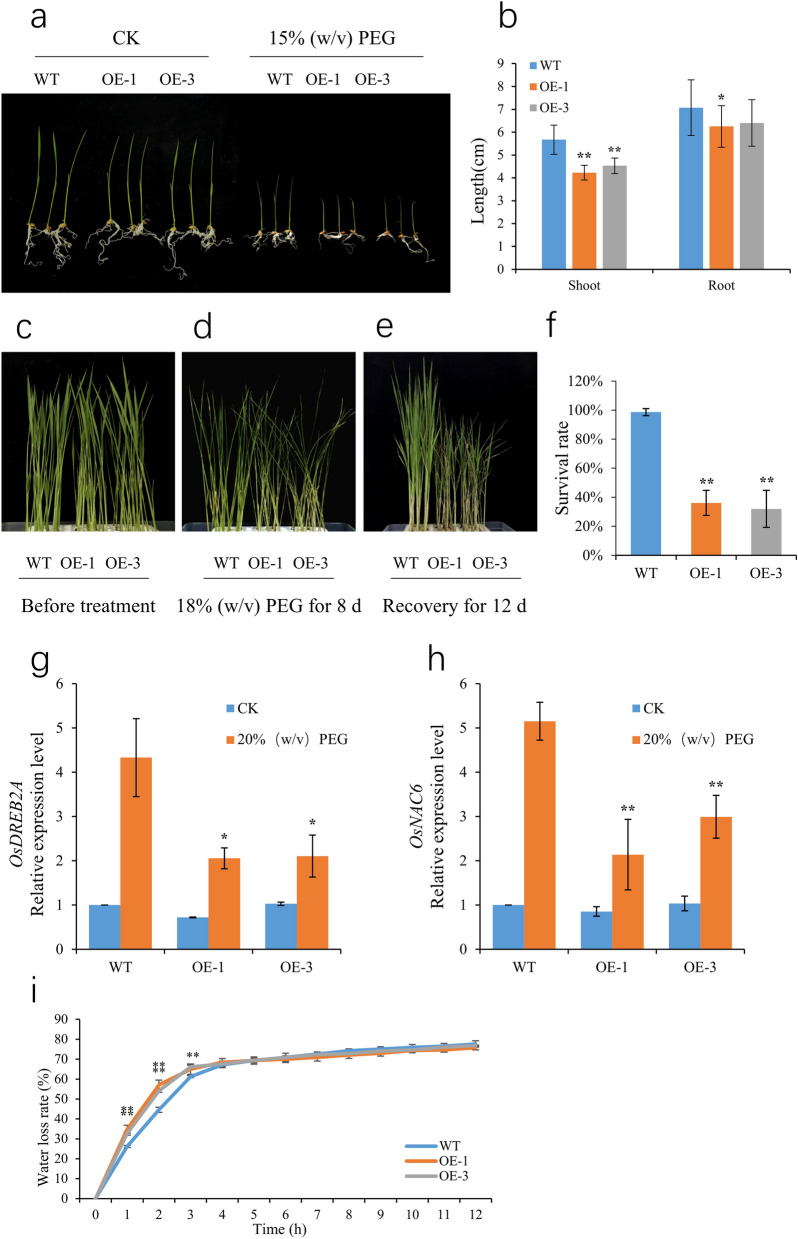

Overexpression of OsSCL30 attenuates drought resistance in transgenic rice

To verify the response of OsSCL30 overexpression to drought stress, we cultured 5-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) in 15% w/v PEG for 3 days followed by 7-day recovery. The OsSCL30-OE grew similarly to WT seedlings under normal growth conditions, but drought inhibited the growth of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (Fig. 4a). After drought treatment, the plant height and root length of transgenic lines were shorter (root length was significant in OE-1 and not significant in OE-3) compared with WT (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Effects of drought stress in wild type (WT) and OE lines. (a) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines under 15% w/v PEG for 3 days. (b) Plant height and root length of WT and OE lines treated at 15% w/v PEG for 3 days. (c) Phenotype of WT and OE lines hydroponically cultivated for 14 days (before imposition of the drought stress). (d) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines treated for 8 days at 18% w/v PEG. (e) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines after 12-day recovery following the 18% w/v PEG treatment. (f) Survival of recovered WT and OE lines. (g–h) The expression levels of OsDREB2A and OsNAC6 were analyzed after two days of treatment at 20% w/v PEG, respectively. (i) Water loss rates of detached leaves from 14-day-old plants. Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

To exacerbate the drought stress, we cultured 14-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) in 18% w/v PEG environment for 8 days and then allowed them to recover for 12 days. The results showed that the severity of wilting was similar in OsSCL30-OE and WT seedlings after 8 days of 18% w/v PEG treatment (Fig. 4d). However, after the recovery period, the survival rate of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (32–36% for the two OE lines) was significantly lower than that of WT (98%) (Fig. 4e–f).

In order to explore the regulatory mechanism of OsSCL30 under drought stress, we detected the expression of important genes in the drought response pathway of OsSCL30 overexpressing plants. The results showed that the expression of drought related response genes OsDREB2A30 and OsNAC631 in rice OsSCL30-OE was down regulated compared with WT (Fig. 4g–h).

In addition, compared with WT, the water loss rate of detached leaves of OsSCL30-OE was significantly higher, indicating that the water holding capacity of OsSCL30-OE was weaker (Fig. 4i). In conclusion, overexpression of OsSCL30 reduced the drought resistance of transgenic rice plants.

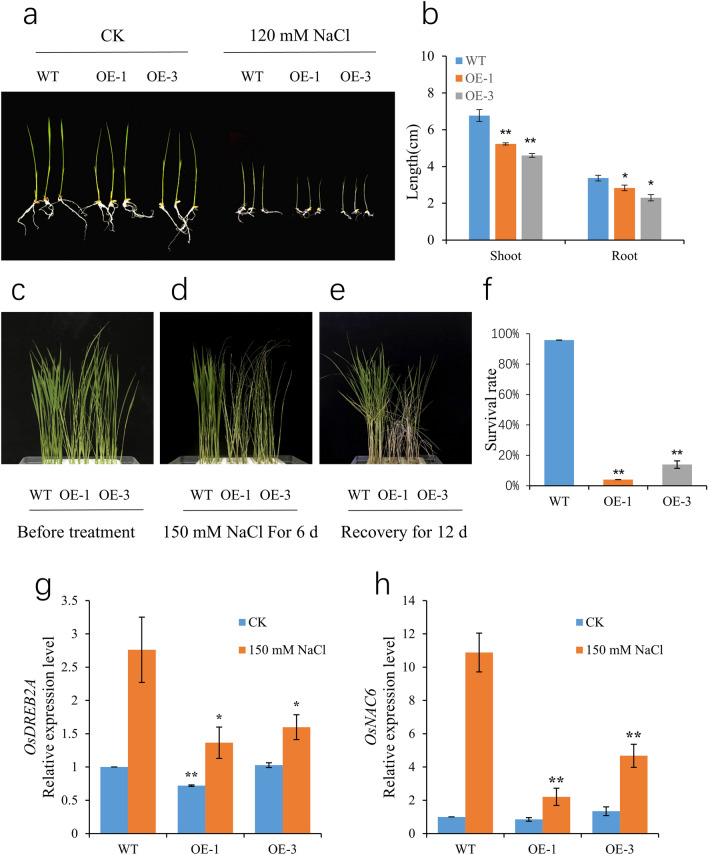

Overexpression of OsSCL30 weakens salt resistance in transgenic rice

To verify the response of OsSCL30 overexpression to high salt stress, we cultured 5-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) in 120 mM NaCl for 3 days followed by recovery for 7 days. The OsSCL30-OE grew similarly to WT seedlings under normal growth conditions, but high salt inhibited the growth of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (Fig. 5a). After salt treatment, both plant height and root length of OsSCL30-OE seedlings were significantly shorter than those of WT (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Effects of salt stress in wild type (WT) and OE lines. (a) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines under 120 mM NaCl for 3 days. (b) Plant height and root length of WT and OE lines treated at 120 mM NaCl for 3 days. (c) Phenotype of WT and OE lines hydroponically cultivated for 14 days (before imposition of the salt stress). (d) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines treated for 6 days at 150 mM NaCl. (e) Phenotypes of WT and OE lines after 12 days recovery following the 150 mM NaCl treatment. (f) Survival of recovered WT and OE lines. (g–h) The expression levels of OsDREB2A and OsNAC6 were analyzed after two days of treatment at 150 mM NaCl, respectively. Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

We cultured 14-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) in 150 mM NaCl for 6 days and then allowed them to recover for 12 days. The results showed that wilting after 6 days of 150 mM NaCl treatment was more severe in OsSCL30-OE than WT seedlings (Fig. 5d). After recovery, the survival rate of OsSCL30-OE seedlings (4–14% for the two lines) was significantly lower than that of WT (96%) (Fig. 5e–f).

In order to explore the regulatory mechanism of OsSCL30 under salt stress, we detected the expression of important genes in the salt response pathway of OsSCL30 overexpressing plants. The results showed that the expression of salt related response genes OsDREB2A30 and OsNAC631 in rice OsSCL30-OE was down regulated compared with WT (Fig. 5g–h). Therefore, we conclude the overexpression of OsSCL30 reduced the salt tolerance of transgenic rice plants.

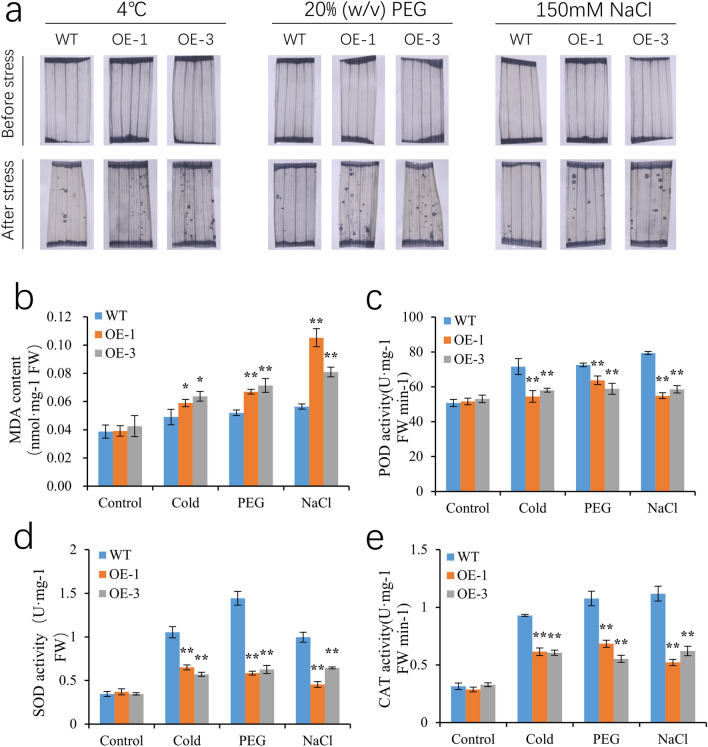

Overexpression of OsSCL30 affects the accumulation and scavenging of ROS under different stresses

To examine the effect of OsSCL30 overexpression on the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), we subjected 14-day-old Nip (WT) and two overexpressing lines (OE-1, OE-3) to different stresses, and performed NBT staining to estimate the accumulation of superoxide ions (O2−). In the control (no stress) treatment, the OsSCL30-OE leaves showed no significant difference from WT; by contrast, after the low temperature, drought and salt treatments the OsSCL30-OE leaves had numerous black spots (indicating more ROS accumulation and more severe oxidative damage) compared with WT (Fig. 6a). As an indication of cellular oxidative damage, the content of MDA showed no significant difference between OsSCL30-OE and WT in the control treatment without stress, whereas after low temperature, drought and salt treatments OsSCL30-OE accumulated more MDA and suffered more severe oxidative damage than WT (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining was used to detect the levels of superoxide anion in wild type (WT) and OE lines before and after low temperature (4 °C for 2 days), drought (20% w/v PEG for 2 days), and salt (150 mM NaCl for 2 days) treatments. (b–e) Detection of reactive oxygen species scavenging enzyme activities in wild type (WT) and OE lines before and after low temperature (4 °C for 2 days), drought (20% w/v PEG for 2 days) and salt (150 mM NaCl for 2 days). Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

The activities of reactive oxygen species scavenging enzymes (SOD, CAT and POD) were similar between OsSCL30-OE and WT without any stress imposed, whereas these activities were significantly lower in OsSCL30-OE than WT after the low temperature, drought and salt treatments, indicating relatively poor capacity of the OsSCL30-OE lines to scavenge reactive oxygen species (Fig. 6c–e).

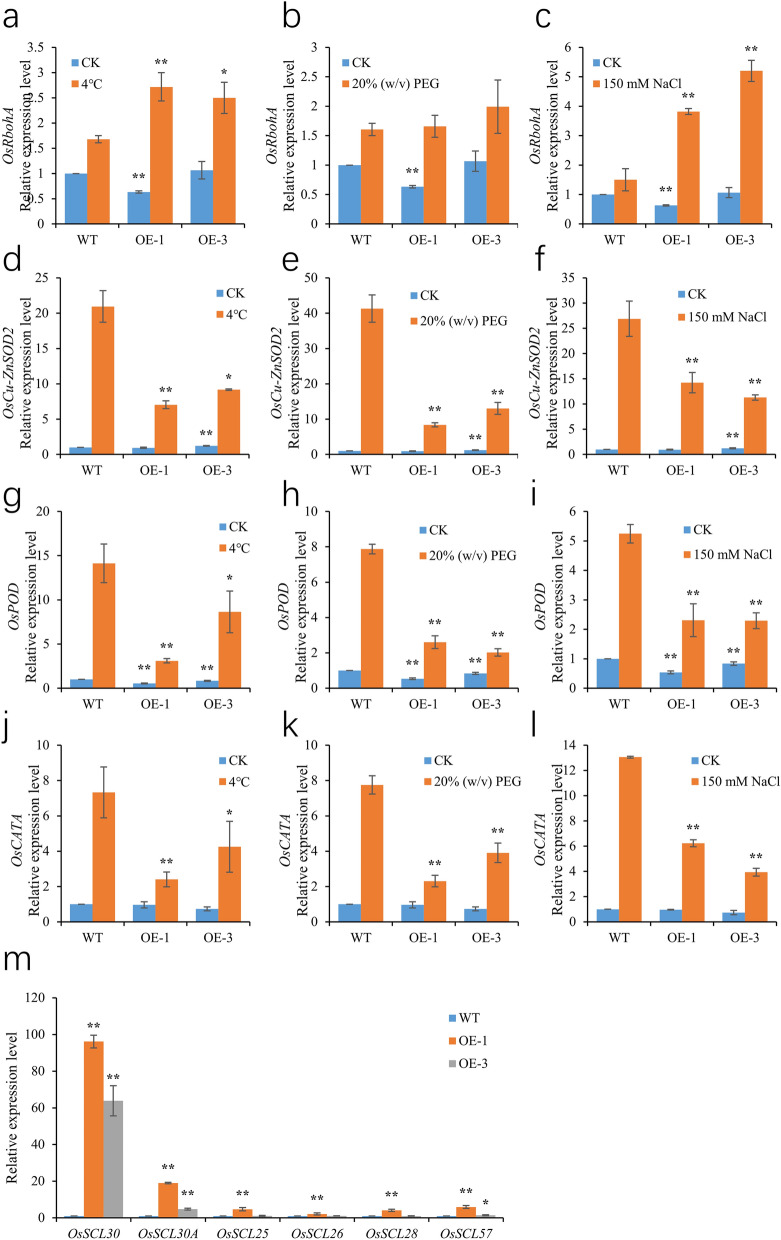

In addition, we also analyzed the changes in expression levels of genes related to reactive oxygen species production and scavenging under cold, drought, salt stress and normal conditions, including OsRbohA (NADPH oxidase), OsCu-ZnSOD2 (superoxide dismutase), OsPOD (peroxidase) and OsCATA (catalase)32,33. Under normal conditions, there was no significant difference in the expression of OsRbohA, OsCu-ZnSOD2, OsPOD and OsCATA between WT and OsSCL30-OE. However, under stress treatment, compared with WT, the expression of OsRbohA in OsSCL30-OE increased in varying degrees (Fig. 7a–c), and the expression of OsCu-ZnSOD2, OsPOD and OsCATA decreased in varying degrees (Fig. 7d–l). In conclusion, under low temperature, drought and salt stresses, overexpression of OsSCL30 can reduce the activity of enzymes scavenging reactive oxygen species, resulting in aggravated oxidative damage.

Figure 7.

(a-l) Expression of ROS production and clearance related genes in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants. (a–c) Expression of OsRbohA in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants are treated with or without 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG and 150 mM NaCl for 2 days. (d–f) Expression of OsCu-ZnSOD2 in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants are treated with or without 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG and 150 mM NaCl for 2 days. (g–i) Expression of OsPOD in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants are treated with or without 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG and 150 mM NaCl for 2 days. (j–l) Expression of OsCATA in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants are treated with or without 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG and 150 mM NaCl for 2 days. (m) Expression of SCL subfamily related genes in WT and OsSCL30-OE plants. Error bars represent ± SE (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between transgenic lines and WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Relative expression of OsSCL30 homologous proteins

It is an established fact that members of SR protein gene family play a crucial role in regulating proteome diversity in spatio-temporal manner. Since the SR protein family consists of multiple members, we studied the effect of OsSCL30 overexpression on other SCL subfamilies in transgenic lines (OsSCL30A, OsSCL25, OsSCL26, OsSCL28, OsSCL57)34. The results showed that the expression of its homologous proteins increased, and the increase of OsSCL30A was the most significant (Fig. 7m). The overexpression of OsSCL30 negatively regulated the abiotic stress tolerance of plants, which may be due to crosstalk with other members of the family, and the cumulative effect leaded to the sensitivity to abiotic stress.

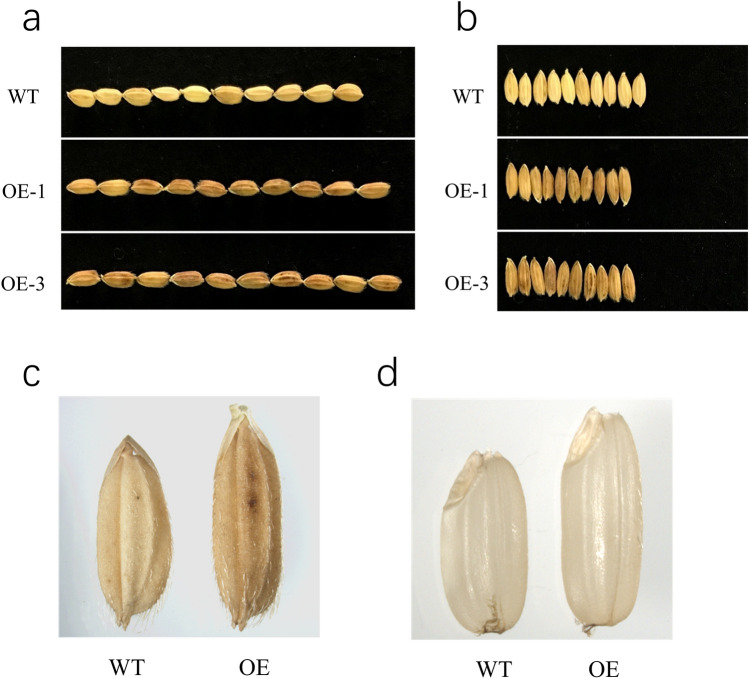

Analysis of agronomic traits in transgenic rice overexpressing OsSCL30

Compared with WT, OsSCL30-OE had obvious difference in grain size. Among them, grain length was significantly longer than WT, increasing by 13.5%, grain width was significantly smaller than WT, decreasing by 13.2%, grain thickness was significantly smaller than WT, decreasing by 4.3%, and 1000-grain weight was slightly larger than WT, but did not reach a significant level. In addition, the color of the glume of OsSCL30-OE was darker than that of WT, and the color of the endosperm was cloudier (Fig. 8). The results of field trait measurement showed that compared with WT, the plant height, tiller number, effective spikes and yield per plant of OsSCL30-OE were significantly reduced by 8.3%, 45.5%, 46.7% and 49.9%, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 8.

Seed phenotypes of WT and OsSCL30-OE of rice. (a) Grain length. (b) Grain width. (c) Glume color. (d) Endosperm color.

Table 1.

Agronomic traits of WT and OsSCL30-OE of rice.

| Traits | WT | OE | Growth rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grain length (mm) | 0.74 ± 0.001 | 0.84 ± 0.012 | 13.5** |

| Grain width (mm) | 0.38 ± 0.017 | 0.33 ± 0.013 | − 13.2** |

| Grain thickness (mm) | 0.23 ± 0.005 | 0.22 ± 0.008 | − 4.3** |

| Thousand-kernel weight (g) | 26.6 ± 0.351 | 26.8 ± 0.400 | 0.75 |

| Tiller | 22 ± 0.834 | 12 ± 0.463 | − 45.5** |

| Plant height (cm) | 96 ± 1.188 | 88 ± 1.165 | − 8.3** |

| Yield per plant (g) | 40.5 ± 0.865 | 20.3 ± 0.968 | − 49.9** |

| Effective spikes | 15 ± 0.622 | 8 ± 0.678 | − 46.7** |

The data in the table are mean ± 10 standard deviations; Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and OsSCL30-OE (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

Abiotic stresses such as drought, salt and extreme temperatures have a huge impact on world agricultural production. Plants typically respond and adapt to these stresses at the levels ranging from molecular to cellular and organ levels, encompassing a range of physiological and biochemical processes35–38. Understanding the complexity of the mechanisms by which plants respond to abiotic stress is crucial for developing high-yielding crops. The results of this study showed that OsSCL30 overexpressing plants had reduced tolerance to low temperature, drought and salt.

The SR proteins are nucleophosmin proteins with characteristic Ser/Arg-rich domains and one or two RNA recognition motifs39.They are a very important class of splicing regulators and can be divided into six subfamilies according to their structural characteristics, namely: SR, RSZ, SC, SCL, RS2Z and RS subfamilies, of which SCL, RS2Z and RS are three subfamilies unique to plants34,40. The SR protein family in plants had been confirmed to have a role of alternative splicing in stress responses41. The expression of AtSR45a was induced by strong light exposure, and the expression of AtSR30 was increased by strong light exposure and plastoquinone (PQ) or salinity treatment, and decreased by low temperature42. Overexpression of Populus trichocarpa PtSCL30 in Arabidopsis reduced cold tolerance, possibly due to alternative splicing (AS) changes in genes critical for cold tolerance such as ICE2 and COR15A43. The cassava MeSCL30a overexpression lines were hypersensitive to salt and drought stress, and had lower germination and greening rates27. In the present study, the OsSCL30 (Os12g38430) (SCL subfamily) codes for the protein located in the nucleus and contains an N-terminal RNA recognition sequence. Low temperature, drought and salt stresses all decreased the expression of OsSCL30, with drought stress having the greatest effect on the expression of OsSCL30 (Fig. 2a–f), indicating that OsSCL30 may be involved in the abiotic stress responses. The overexpression of OsSCL30 reduced the survival rate of transgenic plants under low temperature, drought and salt stresses (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Under stress, the expression of positive regulatory genes in stress-related response in OsSCL30-OE was down regulated compared with WT (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). The overexpression of OsSCL30 affected the expression of SR genes (OsSCL30A, OsSCL25, OsSCL26, OsSCL28 and OsSCL57) of other SCL subfamilies in the transgenic line, and the expression of OsSCL30A increased most significantly (Fig. 7m). These results suggest that OsSCL30 may participate in the splicing of mRNAs, produce proteins with changed function and structure, and negatively regulate the tolerance of plants to low temperature, drought and saline alkali. In addition, OsSCL30 may have crosstalk with other members of the family and produce cumulative effects, thus affect the tolerance of transgenic plants to abiotic stress.

Plants subjected to abiotic stress accumulate ROS44, that can cause oxidative damage to cell membranes, proteins, DNA molecules, etc45–47. The activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT and POD, as well as membrane lipid peroxidation (generating MDA) can reflect the degree of damage to plants caused by stress to a certain extent. SOD can scavenge superoxide anion free radicals, CAT and POD can catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 into H2O and O2, which can help plants resist peroxidation and is positively related to the tolerance of various stresses48–50. As a product of ROS lipid peroxidation, MDA is often used to indicate a degree of cell membrane lipid peroxidation51,52. Overexpression of Cassava MeSR34 enhanced salt stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis by maintaining ROS homeostasis and affecting the CBL-CIPK pathway53; Overexpression of PtSC27 in Populus trichocarpa enhanced salt tolerance by regulating ROS accumulation in transgenic Arabidopsis and reduces the sensitivity of transgenic plants to exogenous ABA54. In the study presented here, the NBT staining results of OsSCL30-OE and WT before the three stress treatments were similar, and the NBT-stained leaves of OsSCL30-OE after stress treatment showed more black spots than WT (Fig. 6a), indicating that the OsSCL30-overexpressing lines accumulated more ROS. Furthermore, the activities of antioxidative enzymes under non-stress conditions were similar in the OsSCL30-overexpressing lines and WT, but under three stress conditions (low temperature, drought, high salt), the activities of SOD, POD and CAT were lower in the OsSCL30 overexpression lines than WT (Fig. 6c–e). The content of MDA was higher in the OsSCL30-overexpressing lines than WT (Fig. 6b). Under normal conditions, there was no significant difference in the expression of OsRbohA, OsCu-ZnSOD2, OsPOD and OsCATA in WT and OsSCL30-OE. However, under stress treatment, compared with WT, the expression of OsRbohA in OsSCL30-OE increased in varying degrees (Fig. 7a–c), and the expression of OsCu-ZnSOD2, OsPOD and OsCATA decreased in varying degrees (Fig. 7d–l). These findings suggested that overexpression of OsSCL30 may alter the splicing pattern of pre-mRNA to generate proteins with multiple functions and structures, so as to regulate ROS scavenging activity, cause transgenic rice plants to suffer more severe membrane damage and reduce their tolerance to cold, drought and salt stress.

The OsSCL30 was localized mainly in the nucleus, with tissue-specific expression (higher in leaves and leaf sheaths than roots, stems and spikelets). Under stress, OsSCL30-overexpression resulted in more severe membrane damage in transgenic rice plants by decreasing the reactive oxygen species scavenging activity, thereby reduced tolerance to cold, drought and salt stress. The results of field trait measurement showed that the effective spikes and yield per plant of OsSCL30-OE were significantly lower than those of WT, and the reduction ratio of yield per plant was the most obvious. Characterization of the negative role of OsSCL30 in rice stress provides a theoretical basis for breeding more stress-tolerant rice using CRISPR/Cas9 gene modification system in the future.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

In this study, the japonica rice Nipponbare (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica 'Nipponbare') was used as the experimental material. We have been granted permission to collect Oryza sativa ssp. japonica 'Nipponbare'. Transgenic rice plants were obtained by agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated genetic transformation55. The seeds were soaked in water for 1 day, then surface sterilized by soaking in 2% v/v NaClO for 30 min and rinsing with sterile water. Afterwards, seeds were spread on moist filter paper in a Petri dish to promote germination. When the shoots grew to 5 mm, the seedlings were transplanted into rice nutrient solution and grown at 28 °C/22 °C and 16 h light/8 h dark cycle56. To study the effect of abiotic stress conditions on the expression of OsSCL30, after 2 weeks of culture, uniformly sized seedlings were selected for stress treatments, including cold (4 °C), salt (150 mM NaCl) and drought (15% w/v PEG 6000). All the experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Fresh leaves were sampled from the normal and stress treatments, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and used for total RNA extraction according to the operating instructions of the RNA extraction kit (BioFlux). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa) and was stored at –20 °C.

Quantitative analysis of OsSCL30 under abiotic stress

Two-week-old rice seedlings were subjected to cold, drought and salt stress treatments, and leaf tissue was harvested at the indicated times for extraction of total RNA and reverse transcription. This cDNA was diluted and used as a template to analyze the gene expression of OsSCL30 under abiotic stress. Primers were designed for OsSCL30 gene and the rice reference gene UBQ (ubiqutin) using Primer Premier 5 software (UBQ-F:5′-AACCAGCTGAGGCCCAAGA-3′; UBQ-R:5′-ACGATTGATTTAACCAGTCCATG-3′; OsSCL30-qRT -F:5′-GTCTCGTTCCCGTTCTC-3′; OsSCL30-qRT -R:5′-GTAGTCATCTCGCCGTCT-3′).

Analysis and cloning of the OsSCL30 gene

To obtain the OsSCL30-overexpression vector, the CDS sequence of OsSCL30 was obtained from the Rice Genome Database (rapdb). The primer for OsSCL30 gene was designed using software Primer Premier 5 (OsSCL30-F:5′- tggagaggacagcccaagcttATGAGGAGGTACAGCCCACCA -3′; OsSCL30-R:5′- gtaccgaattcccggggatccTCAGTCGCTGCGGGCAGG-3′). The amplified target fragments were purified and recovered with a gel recovery kit. The expression vector (D-163 + 1300) was double digested with Hind III and BamH I endonucleases, followed by recombination to construct an OsSCL30 overexpression vector.

Analysis and cloning of promoter

The sequence information about 1.5 kb upstream of the OsSCL30 open reading frame was obtained in NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and then passed through PlantCare (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) for analysis of cis-acting elements in the OsSCL30 promoter.

Genetic relationship analysis of OsSCL30 gene

In order to understand the phylogenetic relationships of OsSCL30 sequences, species with high amino acid sequence similarity were selected and clustered by software MEGA5.0.

Subcellular localization of OsSCL30

Seeds of the OsSCL30-GFP transgenic plants were germinated in the dark, stained with nuclear dye (DAPI), and observed using confocal microscopy.

Transgenic plants treated with abiotic stress

To study the effect of low temperature on overexpressing plants, we cultured 2-week-old plants at 4 °C for 7 days and then allowed them to recover at 28 °C for 12 days. To study the effect of drought on overexpressing plants, we cultured 2-week-old plants at 18% w/v PEG 6000 for 8 days followed by recovery at 28 °C for 12 days. To study the effect of high salt on overexpressing plants, we cultured 2-week-old plants in 150 mM NaCl for 6 days and then allowed them to recovery at 28 °C for 12 days. For all stress treatments plants were grown in the rice nutrient solution.

NBT staining

Two-week-old seedlings were treated at 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG 6000, or 150 mM NaCl for 2 days, respectively, and then stained. Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) staining was performed using the published protocols57.

Measurement of the physiological parameters

Physiological parameters were determined after 2-week-old seedlings were treated for 2 days at 4 °C, 20% w/v PEG 6000 or 150 mM NaCl. The MDA content was determined by spectrophotometry58. The activities of antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) were determined as described elsewhere59.

Water loss rate

The measurement of water loss rate was as described by predecessors60. The leaves of 14-day-old rice seedlings were sampled at room temperature. The leaves were placed on filter paper on the experimental bench and weighed at specified time. Then calculate the percentage of water loss. Three biological repeats were performed on each line.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times, and the results were consistent. The data were processed and analyzed by the t-test, and the difference was statistically significant at P < 0.05(*) or P < 0.01(**).

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Z.X. and L.L. conceived and designed the experiments; J.Z. and Y.S. performed the experiments, and wrote the article; Z.Z., Y.Z., Y.Y., X.Z., X.L., J.W. analyzed the data, produce the figures; X.G., R.C., Z.H. provided support and experimental guidance for this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program under Grant Numbers 2021YFH0085 and 2020YJ0352.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jia Zhang and Yihao Sun.

Contributor Information

Lihua Li, Email: lilihua1976@tom.com.

Zhengjun Xu, Email: mywildrice@aliyun.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-12438-4.

References

- 1.Gross BL, Zhao Z. Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:6190–6197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308942110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyman NB, Jagadish KS, Nalley LL, Dixon BL, Siebenmorgen T. Neglecting rice milling yield and quality underestimates economic losses from high-temperature stress. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almadanim MC, et al. Rice calcium-dependent protein kinase OsCPK17 targets plasma membrane intrinsic protein and sucrose-phosphate synthase and is required for a proper cold stress response. Plant, Cell Environ. 2017;40:1197–1213. doi: 10.1111/pce.12916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer GR, Urano K, Delrot S, Pezzotti M, Shinozaki K. Effects of abiotic stress on plants: a systems biology perspective. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu H, et al. A novel sweetpotato WRKY transcription factor, IbWRKY2, positively regulates drought and salt tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis. Biomolecules. 2020;10:506. doi: 10.3390/biom10040506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouyang SQ, et al. Receptor-like kinase OsSIK1 improves drought and salt stress tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Plant J: Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;62:316–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao C, et al. Mutational evidence for the critical role of CBF transcription factors in cold acclimation in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2744–2759. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni M, et al. Drought response in wheat: Key genes and regulatory mechanisms controlling root system architecture and transpiration efficiency. Front. Chem. 2017;5:106. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida K, Go M. Survey of conserved alternative splicing events of mRNAs encoding SR proteins in land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:1085–1094. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palusa SG, Ali GS, Reddy AS. Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs of arabidopsis serine/arginine-rich proteins: Regulation by hormones and stresses. Plant J.: Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;49:1091–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy AS, Sha Aali G. Plant serine/arginine-rich proteins: Roles in precursor messenger RNA splicing, plant development, and stress responses. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. RNA. 2011;2:875–889. doi: 10.1002/wrna.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishor PBK, et al. Lysine, lysine-rich, serine, and serine-rich proteins: link between metabolism, development, and abiotic stress tolerance and the role of ncRNAs in their regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:546213. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.546213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen S, Li J, Liu Y, Li H. Genome-wide analysis of serine/arginine-rich protein family in wheat and brachypodium distachyon. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2019 doi: 10.3390/plants8070188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Q, Xia X, Sun Z, Fang Y. Depletion of arabidopsis SC35 and SC35-like serine/arginine-rich proteins affects the transcription and splicing of a subset of genes. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Du B, Liu D, Qi X. Splicing factor SR34b mutation reduces cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating iron-regulated transporter 1 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;455:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon EK, Krishnamurthy P, Kim JA, Jeong M-J, Lee SI. Genome-wide characterization of brassica rapa Genes encoding serine/arginine-rich proteins: Expression and alternative splicing events by abiotic stresses. J. Plant Biol. 2018;61:198–209. doi: 10.1007/s12374-017-0391-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Chen Q, Wang S, Hong Y, Wang Z. Rice and cold stress: Methods for its evaluation and summary of cold tolerance-related quantitative trait loci. Rice (New York, N.Y.) 2014;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s12284-014-0024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakur P, Kumar S, Malik JA, Berger JD, Nayyar H. Cold stress effects on reproductive development in grain crops: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010;67:429–443. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Y, et al. Effects of low temperature stress on spikelet-related parameters during anthesis in Indica-Japonica hybrid rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1350. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang JC, et al. A CCR4-associated factor 1, OsCAF1B, confers tolerance of low-temperature stress to rice seedlings. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021;105:177–192. doi: 10.1007/s11103-020-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pino MT, et al. Use of a stress inducible promoter to drive ectopic AtCBF expression improves potato freezing tolerance while minimizing negative effects on tuber yield. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007;5:591–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pino MT, et al. Ectopic AtCBF1 over-expression enhances freezing tolerance and induces cold acclimation-associated physiological modifications in potato. Plant, Cell Environ. 2008;31:393–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong R, et al. Rice SnRK protein kinase OsSAPK8 acts as a positive regulator in abiotic stress responses. Plant Sci.: Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2020;292:110373. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Todaka D, Nakashima K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Toward understanding transcriptional regulatory networks in abiotic stress responses and tolerance in rice. Rice (New York, N.Y.) 2012;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsukura S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of rice DREB2-type genes that encode transcription factors involved in the expression of abiotic stress-responsive genes. Mol. Genet. Genom.: MGG. 2010;283:185–196. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0506-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Q, et al. Overexpression of SCL30A from cassava (Manihot esculenta) negatively regulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Funct. Plant Biol.: FPB. 2021;48:1213–1224. doi: 10.1071/fp21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albaqami M, Laluk K, Reddy ASN. The Arabidopsis splicing regulator SR45 confers salt tolerance in a splice isoform-dependent manner. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019;100:379–390. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun M, et al. miR535 negatively regulates cold tolerance in rice. Mol. Breed. 2020;40:14. doi: 10.1007/s11032-019-1094-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubouzet JG, et al. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-, high-salt- and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J. 2003;33:751–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima K, et al. Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J.: Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;51:617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang Y, et al. A stress-responsive NAC transcription factor SNAC3 confers heat and drought tolerance through modulation of reactive oxygen species in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:6803–6817. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, et al. The plasma membrane NADPH oxidase OsRbohA plays a crucial role in developmental regulation and drought-stress response in rice. Physiol. Plant. 2016;156:421–443. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barta A, Kalyna M, Reddy AS. Implementing a rational and consistent nomenclature for serine/arginine-rich protein splicing factors (SR proteins) in plants. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2926–2929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Vinocur B, Altman A. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: Towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta. 2003;218:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta A, Rico-Medina A, Caño-Delgado AI. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020;368:266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sage TL, et al. The effect of high temperature stress on male and female reproduction in plants. Field Crop Res. 2015;182:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janmohammadi M, Zolla L, Rinalducci S. Low temperature tolerance in plants: Changes at the protein level. Phytochemistry. 2015;117:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong XY, Wang P, Han J, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD. SR proteins in vertical integration of gene expression from transcription to RNA processing to translation. Mol. Cell. 2009;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barta A, Kalyna M, Reddy ASN. Implementing a rational and consistent nomenclature for serine/arginine-rich protein splicing factors (SR Proteins) in plants. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2926–2929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duque P. A role for SR proteins in plant stress responses. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011;6:49–54. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanabe N, Yoshimura K, Kimura A, Yabuta Y, Shigeoka S. Differential expression of alternatively spliced mRNAs of Arabidopsis SR protein homologs, atSR30 and atSR45a, in response to environmental stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1036–1049. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao X, et al. The SR splicing factors: providing perspectives on their evolution, expression, alternative splicing, and function in populus trichocarpa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms222111369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choudhury FK, Rivero RM, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J.: Cell Mol. Biol. 2017;90:856–867. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant, Cell Environ. 2010;33:453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mostofa MG, Hossain MA, Fujita M, Tran LS. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms associated with trehalose-induced copper-stress tolerance in rice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11433. doi: 10.1038/srep11433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scandalios JG. The rise of ROS. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:483–486. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegel BZ. Plant peroxidases: An organismic perspective. Plant Growth Regul. 1993;12:303–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00027212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q, et al. Changes in antioxidative metabolism accompanying pitting development in stored blueberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014;88:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem.: PPB. 2010;48:909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li T, et al. Sodium para-aminosalicylate delays pericarp browning of litchi fruit by inhibiting ROS-mediated senescence during postharvest storage. Food Chem. 2019;278:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He F, et al. PeSTZ1 confers salt stress tolerance by scavenging the accumulation of ROS through regulating the expression of PeZAT12 and PeAPX2 in populus. Tree Physiol. 2020;40:1292–1311. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpaa050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan Y, et al. Systematic analysis of the serine/arginine-rich protein splicing factors (SRs) and focus on salt tolerance of PtSC27 in populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022;173:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toki S, et al. Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J.: Cell Mol. Biol. 2006;47:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campo S, et al. Overexpression of a calcium-dependent protein kinase confers salt and drought tolerance in rice by preventing membrane lipid peroxidation. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:688–704. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.230268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaur N. Detection of reactive oxygen species in Oryza sativa L. (Rice) Bio-protocol. 2016 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z, Huang R. Analysis of malondialdehyde, chlorophyll proline, soluble sugar, and glutathione content in arabidopsis seedling. Bio-protocol. 2013 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen T, Zhang B. Measurements of proline and malondialdehyde contents and antioxidant enzyme activities in leaves of drought stressed cotton. Bio-protocol. 2016 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang Y, et al. Co-overexpression of the constitutively active form of OsbZIP46 and ABA-activated protein kinase sapk6 improves drought and temperature stress resistance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1102. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.