Abstract

Financial constraints usually hinder students, especially those in low-middle income countries (LMICs), from seeking mental health interventions. Hence, it is necessary to identify effective, affordable and sustainable counter-stress measures for college students in the LMICs context. This study examines the sustained effects of mindfulness practice on the psychological outcomes and brain activity of students, especially when they are exposed to stressful situations. Here, we combined psychological and electrophysiological methods (EEG) to investigate the sustained effects of an 8-week-long standardized Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention on the brain activity of college students. We found that the Test group showed a decrease in negative emotional states after the intervention, compared to the no statistically significant result of the Control group, as indicated by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (33% reduction in the negative score) and Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS-42) scores (nearly 40% reduction of three subscale scores). Spectral analysis of EEG data showed that this intervention is longitudinally associated with increased frontal and occipital lobe alpha band power. Additionally, the increase in alpha power is more prevalent when the Test group was being stress-induced by cognitive tasks, suggesting that practicing MBSR might enhance the practitioners’ tolerance of negative emotional states. In conclusion, MBSR intervention led to a sustained reduction of negative emotional states as measured by both psychological and electrophysiological metrics, which supports the adoption of MBSR as an effective and sustainable stress-countering approach for students in LMICs.

Keywords: MBSR, EEG, Stress reduction, Cognitive tasks

1. Introduction

In low-middle income countries (LMICs), several studies reported the high prevalence of mental health issues among university students, up to 55% (Dessauvagie et al., 2021, Pham et al., 2019, Pham Tien et al., 2020). With the intensive impact of COVID-19, nearly 44.6% of students reported having experienced adverse psychological effects during the pandemic (Chinna et al., 2021). Consequently, these stressful experiences could influence brain structures, cognition, and behavior, which profoundly affect working motivation and emotional regulation (Li et al., 2014, Lupien et al., 2009, McEwen, 2000). Therefore, considering a coping stress strategy with high effectiveness and affordability is essential for LMICs students.

One potential stress alleviation strategy is the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), a psychological therapy that offers intensive meditation practice to guide participants to cope with acute stress and decrease distraction (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003, Virgili, 2015). With the availability of its curriculum and online adaptation by the Palouse Mindfulness, MBSR represents a low-cost stress alleviation therapy (Knight et al., 2015, Miller et al., 1995). This therapy has demonstrated positive efficacy in alleviating psychological and physical conditions in different populations (Anh Hoang Minh et al., 2020, Chi et al., 2018). For students of diverse ages, mindfulness-based therapies were shown to be reliable and effective in reducing negative emotional states (Zenner et al., 2014). None of such psychological effects have been thoroughly validated in the LMICs context, where mental health issues rapidly increase amidst the negative economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic while facing a lack of intervention programs. Hence, it is uncertain whether the adaptation of MBSR might be feasible and effective considering the social and cultural differences between developed and developing countries. Therefore, it is important to validate if MBSR could potentially serve as a low-cost and effective stress-reducing strategy for students in LMICs.

Previous studies have not fully addressed whether MBSR-associated psychological effects could be sustained and what might be the neural correlates of these effects. Concomitantly, it is currently unclear whether the overall psychological effects of MBSR could link with the practitioner’s ability to control their stress and anxiety levels when exposed to immediate stress stimuli. To address these inquiries, combining psychological questionnaires with real-time brain activity monitoring techniques could allow us to further understand the effect of MBSR. Electroencephalogram (EEG) is one such technique that has been widely applied to monitor the neural oscillation of distinct brainwaves such as alpha wave. An increase in alpha band power in the prefrontal and frontal lobe during mediation or eyes closed states has supported the effectiveness of the MBSR program on stress reduction and self-awareness enhancement (Aftanas and Golocheikine, 2001, Cahn and Polich, 2006, Gao et al., 2016, Morais et al., 2021, Moynihan et al., 2013). Although most studies successfully demonstrated the immediate and short-term effect of the MBSR program, the sustained impact of this intervention on neural activity has not been shown. Most longitudinal studies reported that questionnaires and brain activity outcomes return to the baseline (pre-MBSR) values (Bennett and Dorjee, 2016, Gouda et al., 2016, McIndoo et al., 2016, Moynihan et al., 2013). Recently, utilizing electrophysiological measures (i.e., ECG, EEG, and EDA), Morais et al. has found that MBSR is associated with an increase of alpha power in the prefrontal cortex during and after the intervention, but no significant similar increase was observed at other brain areas and especially, at two months post the training course (Morais et al., 2021). Additionally, these results are hindered by the lack of a control group, thus giving less power to the conclusion that the change in prefrontal alpha power might be associated with mindfulness training. In light of these findings, it is necessary to design the EEG study to clarify the short-term and sustained effects of MBSR on brain activity of students, especially when exposed to immediate stress conditions. These understandings will certainly shed light on the mechanism of MBSR’s effectiveness.

The present study aims to validate the feasibility and explore the potential sustained effect of the MBSR program in reducing the negative emotional states of a college student population in a low-middle income country (herein: Vietnam). A Control group is included to separate MBSR-associated effects from those due to subjects’ increasing familiarity with the experimental design across the course of the study. We hypothesized that MBSR intervention could effectively lower subjective stress perception and induce changes in brain activity right after the intervention and in a 2-month follow-up. Furthermore, by integrating stress-induced tasks during EEG acquisition, we examine whether the MBSR program helps students retain higher alpha power, which represents stress alleviation and relaxation states, during short-term stress conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Participant recruitment

Forty-nine students with an age range from 18 to 22 years old were initially recruited (35 females; mean age = 19.9 ± 0.75 years and 14 males; mean age = 20.0 ± 0.6 years). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were neurologically healthy (Association, 2013). Additionally, the participants who scored from severe to extremely high score on the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (Depression > 21, Anxiety > 15, and Stress > 26) were excluded. After signing the consent form, subjects were randomly assigned into two groups: Test group – practice MBSR (N = 25) and Control group - do not practice MBSR (N = 24). In the final measurement session (Sustained measurement), the total number of remaining subjects was 41 subjects (N = 20 for the Test group and N = 21 for the Control group). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Biomedical Engineering, International University, Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam National University.

2.2. The intervention: MBSR program

The MBSR program includes 8-week practices strictly following the Palouse Mindfulness course (Palouse). This course was derived from the Jon Kabat-Zinn program (Kabat‐Zinn, 2003) under the guidance of certified mindfulness coaches. The curriculum and training materials of the course were translated into Vietnamese to optimize the effectiveness of the training process. The course objective is to raise self-awareness of well-being and resilience for all students with negative emotional states. Participants were required to attend at least six out of eight lessons and one meditation retreat day. They attended weekly 1.5 h-long classes and a 7-h retreat day, all under instructions from the Palouse Mindfulness certified coaches.

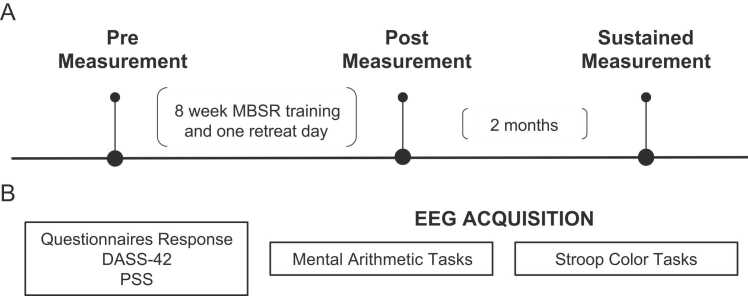

2.3. The overall design of data collection

The experiment includes three main data collection sessions. The first data collection, called the pre-MBSR measurement, occurred right after recruitment (Fig. 1A). The post-MBSR measurement was conducted immediately after the MBSR intervention (Fig. 1A). The last one, called Sustained measurement, happened two months after the previous MBSR session (Fig. 1A). The structure of these measurements is similar for all subjects. At each session (Fig. 1B), subjects were asked to complete two questionnaire packages (See Section 2.4.) and perform two Stress-induced tasks (See Section 2.5.) while their EEG signals (See Section 2.6.) were collected. All questionnaires and stress-inducing tasks were delivered via the Omniscience platform (EMOTIV Inc., Australia). A survey was conducted at the Sustained measurement to track the continuation of meditation practice of the Test group.

Fig. 1.

General experimental procedure.

2.4. Questionnaires

2.4.1. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS includes 10 questions about the unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded situations respondents encountered during the previous month. Four positively phrased items are referred to as “Perceived Coping” or “Perceived Self-Efficacy,” while six negatively phrased items are referred to as “Perceived Distress.” The PSS score is calculated by summing the reverse scores of the positive items and the score of negative items. Higher scores imply higher levels of perceived stress in a range of 0–40 total scores (Maroufizadeh et al., 2018, Roberti et al., 2006).

2.4.2. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-42)

The DASS-42 measures the negative emotional states, namely depression, anxiety, and stress. With 42 items, three subscales such as “Stress,” “Anxiety,” and “Depression” are defined with 14 numbered questions in the form. The score for each category is summed up to be classified from 0 to 42. Five severity labels – “normal,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe” and “extremely severe” are used to describe the meaning of each subscales’ scores (Crawford and Henry, 2003, Lovibond and Lovibond, 1996).

Both PSS and DASS-42 questionnaires were translated into the native language of the subjects, revised and finalized by a Vietnamese neuroscientist and a Vietnamese psychologist before being used. Considering that the main scope of our study is measuring the changes in negative emotions after MBSR training, the contents and length of these two questionnaires were most suitable, as both DASS-42 and PSS were confirmed to be valid and reliable in both clinical and non-clinical samples including the Vietnamese population, and have been widely used in previous MBSR studies (Crawford and Henry, 2003, Jovanović and Gavrilov-Jerković, 2015).

2.5. Cognitive tasks

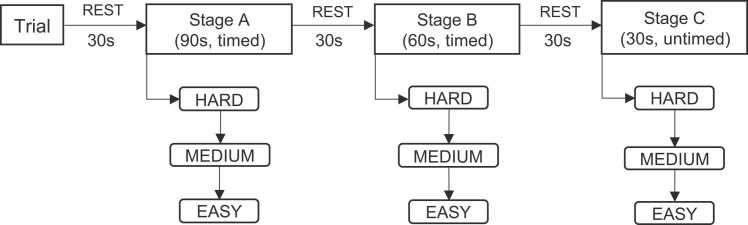

2.5.1. Mental arithmetic (MA) task

Mental arithmetic tasks act as artificial stressors to trigger acute mental stress (Li-Mei Liao and Carey, 2015, Ushiyama et al., 1991). The tasks include one trial stage and three main stages (i.e., Stages A–C). Each stage includes three rounds with different difficulty levels (Fig. 2). The calculations in this task include addition, subtraction, and multiplication. The trial stage is set at the easiest level, which consists of adding or subtracting one digit, for participants to get used to the task and the keyboard. The difficulty level is designed in the order of hard-medium-easy for each stage. The calculation in the hard level applies all the mentioned operations, while the medium and easy levels require from one to two operations of addition or subtraction in one digit. After finishing one round, subjects were asked to evaluate the difficulty of the tasks and their stress level while doing the calculations.

Fig. 2.

Design of the mental arithmetic task.

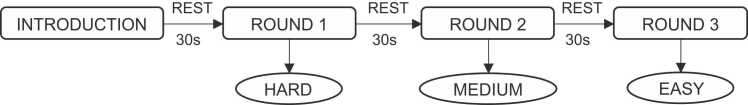

2.5.2. Color Stroop task

Stroop color task is utilized as an artificial stressor (Li-Mei Liao and Carey, 2015, Svetlak et al., 2010). The task consists of three rounds; each round has a time limit of approximately 60 s (Fig. 3). There will be four different colors (yellow, red, purple, green) in this task, which were translated into Vietnamese. Each color corresponds to a single key on the keyboard, which are I–L, respectively. The participants are required to remember the color related to the key. When a word appears on the screen, the participants need to press the key corresponding to the color of that word but not the meaning of the word. The speed of displaying each word is increased after each round; therefore, the time response for one displayed word is reduced.

Fig. 3.

Experimental design of the Stroop color task.

2.6. Electroencephalogram (EEG) recording and analysis

2.6.1. EEG and EOG signal acquisition

The Alice 5 Polysomnography recording system was utilized in conjunction with Alice Sleepware software or Sleepware G3 software (Philips, Respironics Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) to collect raw EEG signals. All recording parameters are kept the same for three measurement sessions except for the sampling rate (i.e., which is set to be 500 Hz for Pre-measurement, and 200 Hz for Post- and Sustained measurements). It is worth noting that this difference in sampling rate between Pre- and Post-, Sustained measurement sessions would not have an effect on EEG analysis as all raw EEG data in Pre-measurement was down-sampled to 200 Hz prior to the analysis. We selected two channels located at the prefrontal (Fp1/Fp2) and four at the frontal (F3/F4 and F7/F8) cortices, as these areas are associated with stress-related states (Al-Shargie et al., 2016). Also, two temporal channels (T5/T6) and two occipital channels (O1/O2) were selected since the included stress tasks in our study were expected to mainly affect temporal and occipital cortices (Wang and Sourina, 2013). Thus, the overall EEG setup comprised 10 Ag/AgCl electrodes with the ground electrode Fpz, and these were re-referenced to mastoid electrodes (M1/M2). EOG signal was recorded from two electrodes located at the tail of the eyes to detect horizontal eye movement. The impedance of all electrodes was kept below 5 kΩ.

2.6.2. EEG preprocessing

The continuous raw EEG data of pre-measurement was firstly down-sampled to the sampling rate of 200 Hz to ensure consistency among all three recording sessions (i.e., Pre-, Post-, and Sustained measurements). The down-sampling process was assisted with the MNE-Python package’s resampling function (i.e., mne.filter.resample), which uses the Fourier method with the improvement of edge padding and frequency-domain windowing (Gramfort et al., 2013, Virtanen et al., 2020). Next, the raw EEG data were subjected to an empirical mode decomposition (EMD) based preprocessing pipeline to remove high-frequency noises (e.g., electromyography (EMG) induced and powerline interference noises) (Zhang et al., 2008). EMD is a data-driven signal decomposition method, of which the underlying notion of instantaneous frequency provides insights into the time-frequency feature of the signal (Huang et al., 1998). EMD decomposes the signal into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). In this study, an enhanced version of EMD, referred to as masking EMD (Deering and Kaiser, 2005), was used to resolve the inherent mode-mixing problem in the original EMD (Deering and Kaiser, 2005, Nguyen et al., 2019, Tsai et al., 2018).

The procedure for EEG signal preprocessing using an open-source Python EMD package is described as follows (Quinn et al., 2021). Firstly, the EEG signal was decomposed sequentially by EMD with an initial masking signal of frequency at 50 Hz to a maximum of ten (N = 10) intrinsic mode functions (IMF) (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B). Secondly, the Hilbert transform was applied to each IMF to obtain the frequency distribution of each IMF (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Each IMF can be distinctively characterized by its frequency range and power. Thirdly, the first mode characterized by high-frequency components (which usually contain power interference and EMG noise) and the last three modes dominated by low-frequency components were removed. The signal was then reconstructed from the remaining IMFs.

2.6.3. EEG Power Spectral Density (PSD)

Power Spectral Density (PSD) is a widely used feature for EEG signal analysis as it can provide insights into brain activation. Since the previous studies suggested that increasing alpha and/or theta power, estimated from PSD, are often observed during meditation compared with control conditions (Aftanas and Golocheikine, 2001, Fan et al., 2014a, Takahashi et al., 2005, Tang et al., 2009). Hence, including PSD is relevant in the context of this study to evaluate the sustained effect of MBSR. The procedure for PSD calculations can be described as follows. The clean data underwent a Fast Fourier transform (FFT) with 4-s Hanning windows and 50% overlap. For each channel, spectral power (µV2) for all task and rest conditions was computed for the following bands: theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), and beta (15–30 Hz). To minimize the inter-individual differences in absolute power, which can be potentially caused by technical variability of each measurement session, we normalized the spectral power of three bands by the baseline spectra similar to previous EEG studies (Bian et al., 2014, Papagiannopoulou and Lagopoulos, 2016, Sammler et al., 2007, Zhao et al., 2018). Specifically, the relative power (RP) for each channel and band was then obtained by dividing the spectral power of that band by the total spectral power between 4 and 40 Hz as in Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where f1 (lower bound) and f2 (upper bound) represent the cut-off frequencies for each band of interest. For example, for the alpha band, the f1 and f2 are 8 and 13 Hz, respectively.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were only conducted on participants who completed all data collections (final total subjects n = 41). We performed the statistical results in GraphPad Prism 8.0 software to analyze statistics in three stages in two groups. In the analyzes described below, the significant results were demonstrated when the p-value was < 0.05. We specified the star representing the p-value reported in APA style, according to: .033 (*), .002 (**), < 0.001 (***) and < 0.0001 (****) for all figures. The statistical results were plotted as the column graphs.

Two-way ANOVA with Šidák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for the psychological self-evaluation and performance results of the two stress-inducing cognitive tasks.

For EEG band power, the relative power value that differs more than two folds of the standard deviation from the group mean in each electrode in multiple frequency bands was first excluded from the analysis. Given this outliers exclusion and missing data, the linear mixed-effects model with Sidak correction was used to examine group differences (Bates et al., 2015). Linear mixed-effect models are appropriate to process longitudinal data with missing values (Magezi, 2015, Overall and Tonidandel, 2006). The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used for violations of sphericity. It is important to note that interactions not involving groups are not reported.

We also applied linear regression in scatter plots to understand the correlation between two variables, which are Stress vs. Difficulty and PSD features vs. questionnaires. Then, the two-sample t-test is utilized to determine the differences between slopes in two subject groups.

3. Results

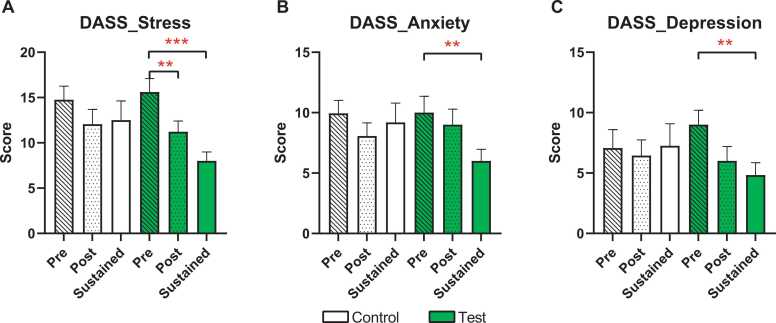

3.1. MBSR intervention reduces stress, anxiety, and depression scores

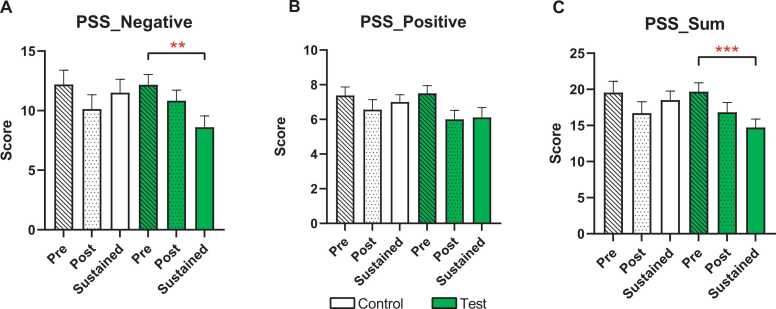

In the previous studies, the MBSR was shown to effectively reduce the stress levels in several subject groups such as Social Anxiety Disorder patients (Faucher et al., 2016), and university students (Galante et al., 2018), and employees (Janssen et al., 2018). However, it is unclear if a student group in the LMICs context could also benefit from MBSR. Here we utilized the PSS and the Stress score in the DASS-42 scale to assess the subjective stress perception of student participants. Our result demonstrated that right after the intervention (post-MBSR measurement), only the Test group’s DASS stress score was found to decrease (p = 0.002, 30%, Fig. 5A), while no change in PSS scores was noticed in post-MBSR measurement (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the Test group’s stress score for both measures substantially decreased when comparing between pre-MBSR measurement score and the Sustained measurement score (p = 0.002, 33%, Fig. 4A and p < 0.001, 50%, Fig. 5A for PSS negative score and DASS stress score, respectively). The combined PSS sum score of the Test group was also reduced by 25% (p < 0.001) in the Sustained measurement (Fig. 4C). On the contrary, the DASS stress score and PSS negative score of the Control group remained unchanged over time (Fig. 5A and Fig. 4A). The PSS’s positive score (i.e., the “Perceived Coping” items) also did not show any change in both groups (Fig. 4B). Note that the p-values of all multiple comparisons in PSS and DASS scores between three measurement sessions of both Control and Test group can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 5.

The change in score of the three subscales score of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-42) questionnaire in three data measurements for both Control group (n = 21) and Test group (n = 20). A) Stress, B) Anxiety, C) Depression. Each bar represents Mean ± SEM.

Fig. 4.

The change in score of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire in three data measurements (Pre: pre-MBSR, Post: post-MBSR or Sustained) for both Control group (n = 21) and Test group (n = 20). A) Negative score, B) Positive score, C) Total score. Each bar represents Mean ± SEM.

To understand whether MBSR could influence other mental health issues, we analyzed the Depression and Anxiety scores from the DASS-42 scales. In general, the Control group had a stable subscale score over time. Interestingly, in the Sustained measurement, the Anxiety and Depression subscales of the Test group were reduced by almost 40% from the initial scores (p = 0.002, Fig. 5B and 5C), though no change in this score is observed between the pre-MBSR and post-MBSR measurement (Fig. 5B and 5C). It remains unclear whether the slow effect of MBSR on anxiety and depression levels (Fig. 5) should be attributed to the training course or the continuation of mediation practice after course completion (Supplementary Fig. S2).

3.2. Investigating brain activity response to stress-induced tasks

3.2.1. Validating the stress-inducing effect of the Mental Arithmetic (MA) and Stroop tasks

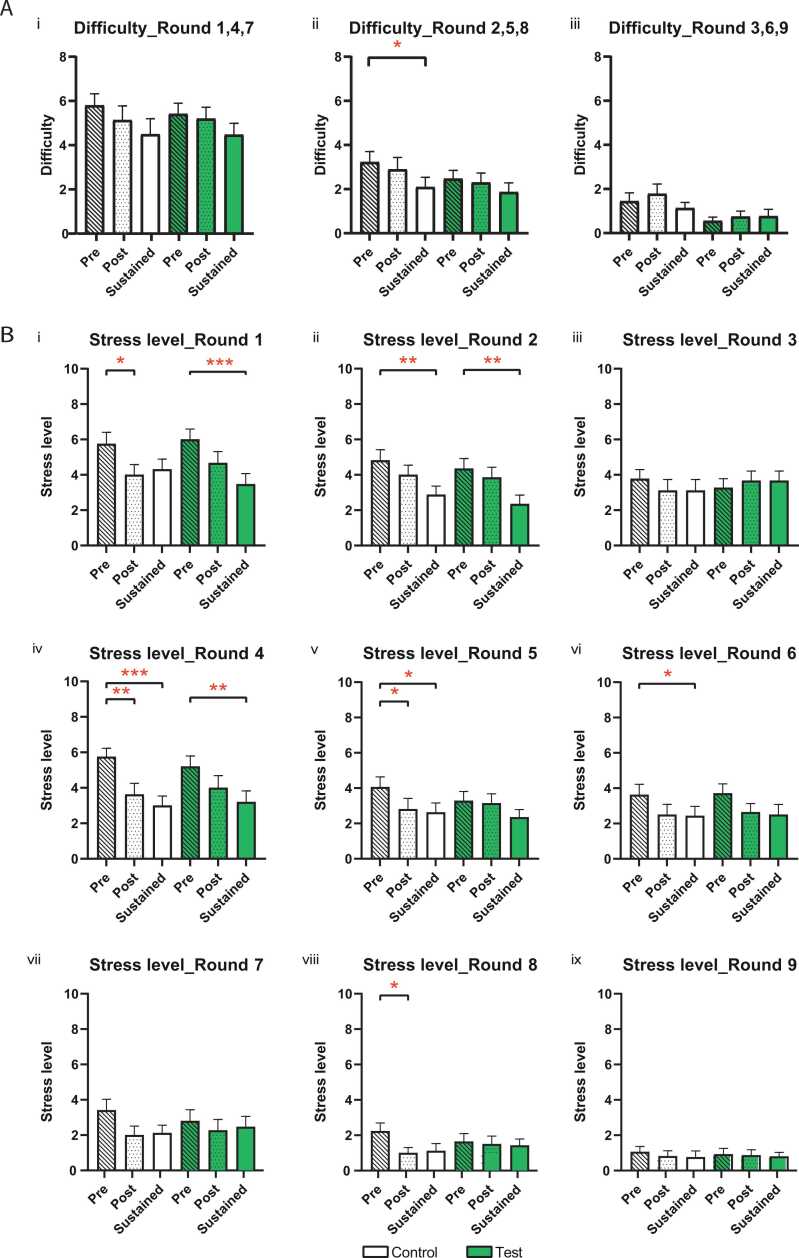

Since one of the main goals of MBSR training is to improve the participants’ ability to cope with their negative emotions, we hypothesize that MBSR could influence brain activity in response to stress (Carroll et al., 2021, Johns et al., 2016, Katahira et al., 2018). To validate this hypothesis, we first designed a set of stress-induced tasks, including the Mental Arithmetic (MA) tasks and the Stroop tasks. We arranged the tasks in the order of hard-medium-easy repetitively during three-stage MA tasks performance, while the Stroop tasks speed up the reaction after each round (Al-shargie et al., 2016, Jun and Smitha, 2016)

Comparing different difficulty levels of the MA tasks, we found that the difficulty and stress rating of the subjects is aligned with our experimental design (p < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. S3). Specifically, these difficulty and stress ratings reduced significantly from timed rounds to untimed rounds in both groups at all three measurements (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The Control group’s difficulty and stress perception scores toward the MA tasks were reduced at several task rounds between pre-MBSR and Sustained measurement, specifically on hard and medium rounds (Fig. 6A ii and Fig. 6B). In contrast, the perception of the Test group toward these two metrics remained largely stable over time. On the other hand, at the easy level, both groups did not report any considerable difference except for the reduction in stress perception of the Control group in Round 6 (p = 0.033, Fig. 6B vi). Note that the p-values of difficulty and stress level in each round are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. These findings could be attributed to the increasing familiarity with the tasks of the Control group, which resulted in the reduction of mean reaction time (p = 0.033, Supplementary Fig. S4A) and higher accuracy (Supplementary Fig. S5A).

Fig. 6.

Self-reported evaluation of difficulty (A) and stress (B) in different task levels in three data measurements for both Control group (n = 21) and Test group (n = 20). Rounds 1, 4, 7; rounds 2, 5, 8; and rounds 3, 6, 9 are defined as difficult, medium, and easy levels, respectively. Each bar represents Mean ± SEM.

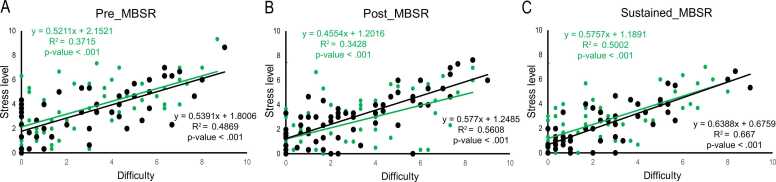

Overall, increasing difficulty perception of the tasks is positively correlated with higher stress sentiment among the subjects of both experimental groups across all three measurements (p < 0.001, R2 ~ 0.372–0.667, Fig. 7). Additionally, when comparing the linear regression slopes of the two groups, the self-reported evaluations did not show differences between the stress level and difficulty perceptions of all subjects (p > 0.05) (Fig. 7). Therefore, both groups reported equivalent perceptions about difficulty and stress levels corresponding to the tasks. In conclusion, these findings confirm that the stress-induced tasks successfully generated stress sensation, especially at higher difficulty levels for both the Control and Test groups.

Fig. 7.

The relationship between Stress and Difficulty after performing the Mental Arithmetic tasks in three data measurements for both Control group (black dots, n = 21) and Test group (green dots, n = 20).

Regarding the Stroop color tasks, the mean reaction time of Round 1 tended to reduce in all subjects of both groups, while similar metrics of the last two rounds were stable over time. Meanwhile, the Control group increased accuracy (p = 0.002) at all three measurements in the Stroop tasks, indicating that they got accustomed to the tasks (Supplementary Fig. S4B, S5B).

3.3. Electroencephalography

3.3.1. Power Spectral Density (PSD)

As the previous EEG studies on mindfulness have shown that meditation was associated with increased alpha power and theta power in both healthy individuals and in patient groups (Fan et al., 2014a, Fan et al., 2014b; Lomas et al., 2015; Takahashi et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2009), we hypothesized that the Sustained effect of participating in MBSR training would be characterized by the increase in power of alpha and theta oscillations. To test this hypothesis, we performed the PSD calculation based on preprocessed EEG data, then compared the relative power of oscillations (e.g., alpha, beta, and theta) during task performing and resting phases between the Control and Test groups. The initial analysis of relative power in 22 individual phases (i.e., 9 rounds of mental arithmetic tasks, 3 rounds of Stroop tasks, and 10 rests) indicated no difference (p > 0.05) between the two groups. We then averaged the relative power of all rounds of mental arithmetic tasks, all rounds of Stroop tasks, and all rest sections related to each task to perform statistical analysis. Thus, the results of statistical analysis are reported for the following conditions: Mental Arithmetic Tasks, Mental Arithmetic Rest (i.e., averaged value of six resting phases in-between each round of mental arithmetic tasks), Stroop Tasks, and Stroop Rest (i.e., averaged four resting phases in-between each round of Stroop tasks). The p-values of all multiple comparisons between PSD values of three measurement sessions of both Control and Test group are summarized in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

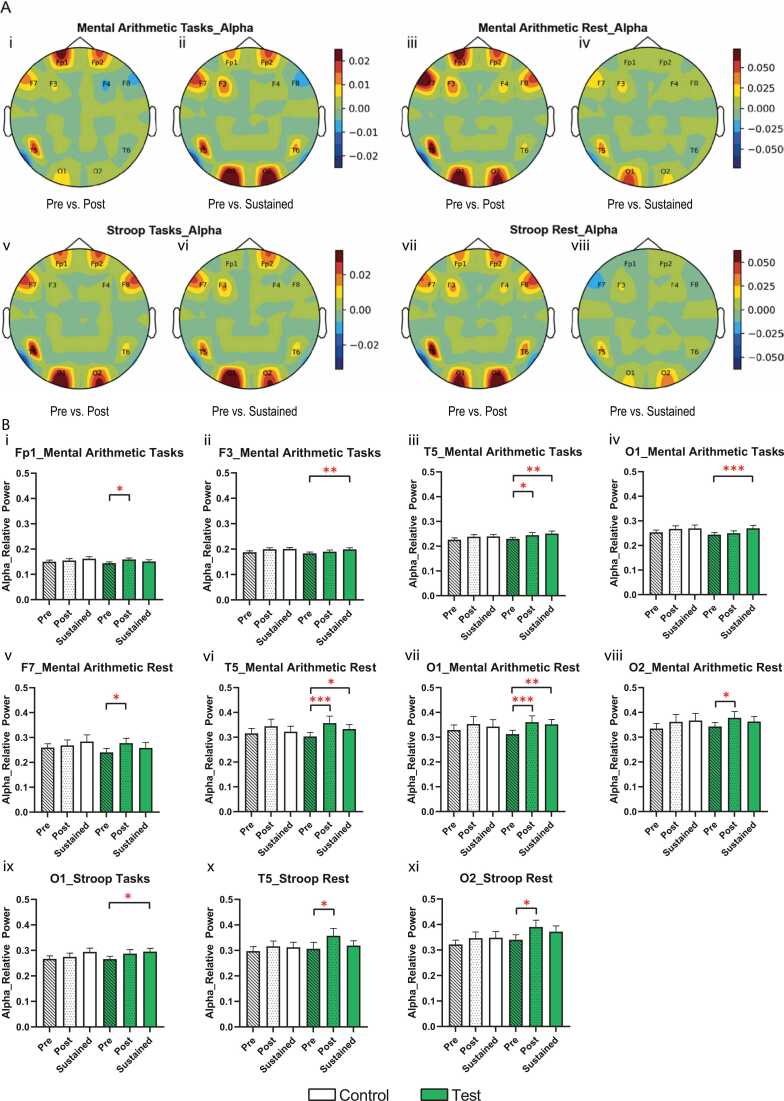

3.3.2. MBSR intervention is associated with a sustained increase in alpha band power

Test group’s relative alpha power was distinctively characterized by significant increases in the frontal, temporal and occipital areas right after and 8-week after the intervention (i.e., post-MBSR measurement and Sustained measurement) (Fig. 8). No change was observed for the Control group. There were also no noticeable differences in alpha power between two groups over time when applied One-way ANOVA. The increase in the relative alpha power of the Test group can be revealed spatially in the topographic map (Fig. 8A). Specifically, in the frontal area, relative alpha power for the Test group showed robust increases at both post-MBSR (p = 0.033, Fig. 8B i, v, at Fp1 and F7 channels) and Sustained measurement (p = 0.002, Fig. 8B ii, at F3 channel) when compared with pre-measurement. A similar rise in alpha band power was also found in the temporal cortex, which was present in both post-MBSR measurement (p = 0.033, Fig. 8B iii and p < 0.001, Fig. 8B vi) and Sustained measurement (p = 0.002, Fig. 8B iii and p = 0.033, Fig. 8B vi). At the occipital area, the alpha power after intervention for the Test group was also higher at both post-MBSR and Sustained measurement for the O1 electrode (Fig. 8B iv, vii, ix) or only post-MBSR measurement for the O2 electrode (Fig. 8B viii and xi). Overall, the MBSR training led to a global strengthening in alpha band power at both rest and task stages. To estimate the correlation between changes in alpha band power and changes in subjective stress perception, we applied linear regression in the delta values (i.e., post – pre) of alpha power at each channel and delta values of each questionnaire subscale. We found that the Test group has a significant correlation between the delta values of alpha power of temporal and occipital lobes with the delta values of the DASS results, especially in the Anxiety and Depression subscales after completing the MBSR course (Supplementary Table 5, p < 0.05 and R2 = 0.305), implying that the change in alpha power at these brain regions might be a neural representation of the psychological improvement.

Fig. 8.

The effect of MBSR practice on brain activity during Resting phase and during Stress-induced tasks is reported by the relative power of alpha band. A) Topo maps indicate the changes in brain activity in Test group. B) The column plots summarize specific channels having statistically significant changes in alpha band power. Each bar represents Mean ± SEM.

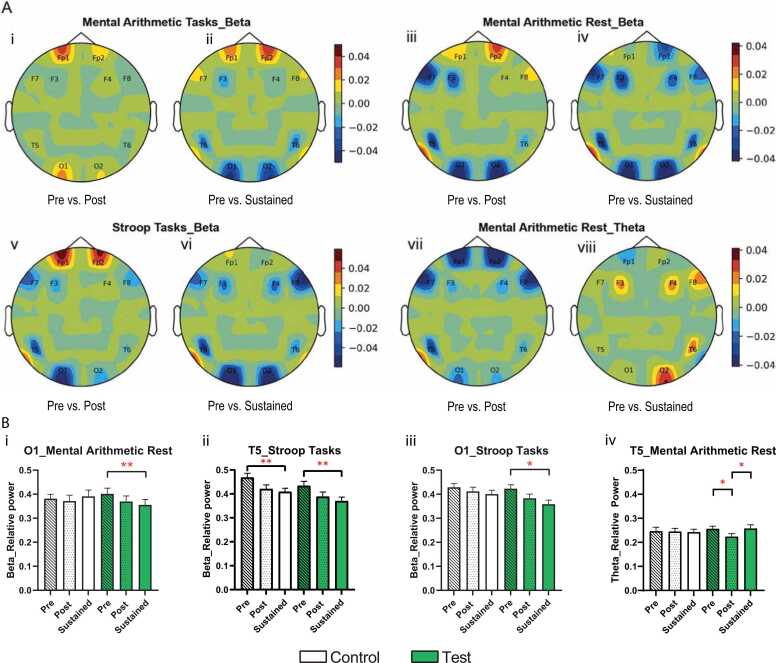

3.3.3. Lower beta power was observed after the intervention

Theta and beta activities were also lower for the Test group in post- and Sustained measurements (Fig. 9A), but these changes were not prevalent and distinctive as those in alpha power. In particular, the relative beta power of the Test group in Mental Arithmetic Rest and Stroop Tasks at the O1 position was reduced eight weeks after intervention (Sustained measurement, p = 0.002, p = 0.033, respectively) (Fig. 9B i and iii). Surprisingly, both the Control and Test groups had lower beta relative power during Stroop Tasks at the T5 position (p = 0.002, Fig. 9B ii), implying that this reduction might be independent of the MBSR training. With regards to relative theta power, the statistical analysis only revealed one decrease at the T5 position for the Test group during Mental Arithmetic Rest right after intervention (post-measurement) (p = 0.033), but then followed by an increase in Sustained measurement (p = 0.033) (Fig. 9B iv), indicating that this effect of MBSR on theta band power is not long-lasting. Overall, Supplementary Fig. S6 summarizes the effect of MBSR practice on brain activity during rest and task stages. Here, it was evident that MBSR practice is associated with sustained stronger alpha power at rest stages (Supplementary Fig. S6A, B) and during mental arithmetic task performance but not during Stroop task (Supplementary Fig. S6B). Compared to the increase in relative alpha power, the decrease in beta and theta is less pervasive and not particularly distinctive for MBSR intervention.

Fig. 9.

The effect of MBSR practice on brain activity during Resting phase and during Stress-induced tasks is reported by the power of beta and theta frequency bands. A) Topo maps indicate the changes in the beta band (i–vi) and theta band (vii–viii). B) The column plots summarize specific channels having significant changes in the relative power of beta band and theta band. Each bar represents Mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

4.1. MBSR training led to a sustained reduction in negative emotion states

The overall negative emotional states were steeply reduced in the Test group post-intervention in the DASS-42 Stress subscale (Fig. 5A). These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated stress reduction in either university students or other populations (cancer patients and the elderly) via PSS or DASS-42 scales (Aftanas and Golocheikine, 2001, Fan et al., 2014b, Matousek et al., 2011, McIndoo et al., 2016, Morais et al., 2021, Moynihan et al., 2013, Song and Lindquist, 2015). Despite the disruption caused by the COVID-19 outbreak during the last two weeks of the MBSR program, the MBSR program still brings out the robust effect on stress reduction.

This study was also one of the first longitudinal studies that showed the sustained effects of MBSR on stress, depression, and anxiety reduction (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). In previous works, the PSS or DASS scores mostly returned to baseline in the follow-up measurement (McIndoo et al., 2016, Morais et al., 2021, Moynihan et al., 2013), which might occur due to the difference in subject groups or practice environment. It was rather intriguing to notice that most of these MBSR-induced positive psychological impacts were more evident in the 2-month follow-up rather than immediately after the intervention, implying such a program would be more profoundly beneficial if subjects continue to implement the skills and knowledge taught during the course. The majority of Test group subjects in our study maintained their meditation sessions (Supplementary Fig. S2), resulting in the sustained psychological effect of MBSR and highlighting the high feasibility of this intervention.

4.2. Mindfulness practice primarily induced higher alpha band power

We found a significant increase in alpha power for the Test group in frontal, temporal, and occipital cortices in both hemispheres post-intervention (Fig. 8). This finding is in line with several previous studies which reported the increase in alpha synchronization associated with mindfulness compared with pre-intervention (Morais et al., 2021). The alpha band power is indicative of the state of stress reduction and relaxation (Seo and Lee, 2010). This increase in alpha power post-intervention of the Test group, especially in the prefrontal and frontal area, might reflect the improvement of internal processing, suggesting the enhanced ability to direct attention internally, with a decrease in thought dispersion (Cooper et al., 2006).

As shown in Fig. 9A and Supplementary Fig. S6, changes in beta power are not typically distinctive for the Test group, as there was the T5 electrode of the Control group showed a significant main effect or interaction. These changes in beta power might be misinterpreted as sustained effects of MBSR training if the Control group was not included, as there were in similar MBSR studies (Morais et al., 2021). Longitudinal reduction of beta-band power has been associated with previously reported mindfulness training (Saggar et al., 2012). However, there was a discrepancy among EEG studies on mindfulness regarding changes in beta oscillations, and the interpretation of the functional significance of beta is also mixed (Lomas et al., 2015). We suspected that changes in both Test and Control groups might reflect the participants’ familiarity with included cognitive tasks, since beta oscillations are typically associated with the sensorimotor processing (Brovelli et al., 2004). While both the brain response and the negative emotion scales exhibited similar trends after MBSR practices for only the Test group, a concomitantly significant correlation between these measurements was found in both subject groups (Supplementary Table 1). No difference in the degree of correlation was detected. Therefore, MBSR potentially did not affect the intrinsic relationship between psychological measurements and their corresponding neural representative.

4.3. Limitations

While the current study shows several promising results, few limitations are presented. Firstly, the relatively small-scale study (n = 49, in one university) could potentially limit the statistical analysis. Additionally, the MBSR session requires 8-week consecutive practice; therefore, participants, such as full-time employees, might drop out due to a limited time budget. One potential strategy to maintain the participants’ commitment is to utilize shortened versions of MBSR, which were successfully implemented on subject groups such as pharmacy students and demonstrated clear psychological improvement (Hindman et al., 2015, McIndoo et al., 2016, O'Driscoll et al., 2019). An official and validated version of a shortened MBSR program is, however, not available; hence, their implementation is rather challenging.

5. Conclusion

Academic pressure tends to affect the mental health of college students negatively. This study aims to clarify an effective MBSR program for college students by assessing the sustained efficacy of the intervention on stress alleviation and brain activity when responding to short-term stress conditions. Our results indicated that MBSR effectively reduced stress scores in the Test group after completing the MBSR training, whereas the similar measure of the Control group remained stable (Fig. 5A). Even two months after the training, subjects in the Test group exhibited lower negative emotional states, especially in the Anxiety and Depression scores (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). The stress reduction effect in the Test group was accompanied by an increase in frontal, temporal and occipital alpha power (Fig. 8) when subjects were exposed to short-term stress stimulations at both post and Sustained measurements. In conclusion, the sustained effects of MBSR were successfully demonstrated based on the reduction of subjective stress perception score and the ability to maintain high alpha power while coping with stress-stimuli.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anh An: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Huy Hoang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Long Trang: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Quyen Vo: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Luan Tran: Software, Investigation. Thao Le: Investigation. Anh Le: Investigation. Alicia McCormick: Conceptualization, Software, Resources. Kim Du Old: Software, Resources. Nikolas S William: Software, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Geoffrey Mackellar: Software, Resources. Emy Nguyen: Software, Resources. Tien Luong: Conceptualization, Resources. Van Nguyen: Conceptualization, Resources. Kien Nguyen: Software, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Huong Ha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

This research is funded by International University, (VNU-HCM), Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, under Grant no. T2019-04-BME. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to EMOTIV inc. for supporting Omniscience Platform for this study and to Thuong Nguyen, Nhu Nguyen, Khiet Dang, Hieu Nguyen, Quang Nguyen, Thinh Tran, Dang Nguyen, Duy Phan for their help during data collection. We also express special thanks to Dr Khoa Duong for his suggestions on study design and to Chi Nguyen for her suggestions on the MBSR curriculum.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ibneur.2022.05.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Aftanas L.I., Golocheikine S.A. Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: high-resolution EEG investigation of meditation. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;310(1):57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shargie, F., Tang, T.B., Badruddin, N., Dass, S.C., Kiguchi, M., 2016. Mental stress assessment based on feature level fusion of fNIRS and EEG signals. In: Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference on Intelligent and Advanced Systems (ICIAS).

- Anh Hoang Minh, A., Nghia Trung, N., Thuong Hoai, N., Khiet Thi Thu, D., Ha, H.T.T., 2020. The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction among various subject groups: a literature review. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam.

- Al-shargie, F.M., Tang, T.B., Badruddin, N., Kiguchi, M., 2016. Mental Stress Quantification Using EEG Signals. In: Ibrahim, F., Usman, J., Mohktar, M., Ahmad, M. (eds) International Conference for Innovation in Biomedical Engineering and Life Sciences. ICIBEL 2015. IFMBE Proceedings, 56. Springer, Singapore, pp. 15–19.

- Association A.P. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67(1) doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K., Dorjee D. The impact of a mindfulness-based stress reduction course (MBSR) on well-being and academic attainment of sixth-form students. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):105–114. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0430-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Z., Li Q., Wang L., Lu C., Yin S., Li X. Relative power and coherence of EEG series are related to amnestic mild cognitive impairment in diabetes [original research] Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brovelli A., Ding M., Ledberg A., Chen Y., Nakamura R., Bressler S.L. Beta oscillations in a large-scale sensorimotor cortical network: directional influences revealed by Granger causality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(26):9849–9854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308538101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn B.R., Polich J. Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132(2):180. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A., Sanders-O′Connor E., Forrest K., Fynes-Clinton S., York A., Ziaei M., Flynn L., Bower J.M., Reutens D. Improving emotion regulation, well-being, and neuro-cognitive functioning in teachers: a matched controlled study comparing the mindfulness-based stress reduction and health enhancement programs. Mindfulness. 2021:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01777-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi X., Bo A., Liu T., Zhang P., Chi I. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1034. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinna K., Sundarasen S., Khoshaim H.B., Kamaludin K., Nurunnabi M., Baloch G.M., Hossain S.F.A., Sukayt A., Dalina N., Rajagopalan U. Psychological impact of COVID-19 and lock down measures: an online cross-sectional multicounty study on Asian university students. PLoS One. 2021;16(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N.R., Burgess A.P., Croft R.J., Gruzelier J.H. Investigating evoked and induced electroencephalogram activity in task-related alpha power increases during an internally directed attention task. Neuroreport. 2006;17(2):205–208. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000198433.29389.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J.R., Henry J.D. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): normative data and latent structure in a large non‐clinical sample. Brit. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003;42(2):111–131. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering, R., Kaiser, J.F., 2005. The use of a masking signal to improve empirical mode decomposition. In: Proceedings. (ICASSP'05). IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, 2005.

- Dessauvagie A.S., Dang H.-M., Nguyen T.A.T., Groen G. Mental health of university students in southeastern Asia: a systematic review. Asia Pac. J. Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10105395211055545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Tang Y.-Y., Tang R., Posner M.I. Short term integrative meditation improves resting alpha activity and stroop performance. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 2014;39(3):213–217. doi: 10.1007/s10484-014-9258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Tang Y.-Y., Tang R., Posner M.I. Short term integrative meditation improves resting alpha activity and stroop performance. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 2014;39(3–4):213–217. doi: 10.1007/s10484-014-9258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faucher J., Koszycki D., Bradwejn J., Merali Z., Bielajew C. Effects of CBT versus MBSR treatment on social stress reactions in social anxiety disorder. Mindfulness. 2016;7(2):514–526. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0486-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galante J., Dufour G., Vainre M., Wagner A.P., Stochl J., Benton A., Lathia N., Howarth E., Jones P.B. A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the mindful student study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(2):e72–e81. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Fan J., Wu B.W.Y., Zhang Z., Chang C., Hung Y.-S., Fung P.C.W., hung Sik H. Entrainment of chaotic activities in brain and heart during MBSR mindfulness training. Neurosci. Lett. 2016;616:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda S., Luong M.T., Schmidt S., Bauer J. Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study [original research] Front. Psychol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramfort A., Luessi M., Larson E., Engemann D., Strohmeier D., Brodbeck C., Goj R., Jas M., Brooks T., Parkkonen L., Hämäläinen M. MEG and EEG data analysis with MNE-Python [methods] Front. Neurosci. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman R.K., Glass C.R., Arnkoff D.B., Maron D.D. A comparison of formal and informal mindfulness programs for stress reduction in university students. Mindfulness. 2015;6(4):873–884. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0331-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N.E., Shen Z., Long S.R., Wu M.C., Shih H.H., Zheng Q., Yen N.-C., Tung C.C., Liu H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998;454(1971):903–995. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1998.0193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen M., Heerkens Y., Kuijer W., Van Der Heijden B., Engels J. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on employees’ mental health: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns S.A., Von Ah D., Brown L.F., Beck-Coon K., Talib T.L., Alyea J.M., Monahan P.O., Tong Y., Wilhelm L., Giesler R.B. Randomized controlled pilot trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast and colorectal cancer survivors: effects on cancer-related cognitive impairment. J. Cancer Survivorship. 2016;10(3):437–448. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0494-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović V., Gavrilov-Jerković V. More than a (negative) feeling: validity of the perceived stress scale in Serbian clinical and non-clinical samples. Psihologija. 2015;48(1):5–18. doi: 10.2298/PSI1501005J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jun Guo, Smitha K.G. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) IEEE; 2016. EEG based stress level identification; pp. 3270–3274. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat‐Zinn J. Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katahira K., Yamazaki Y., Yamaoka C., Ozaki H., Nakagawa S., Nagata N. EEG correlates of the flow state: a combination of increased frontal theta and moderate frontocentral alpha rhythm in the mental arithmetic task. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:300. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R.W., Bean J., Wilton A.S., Lin E. Cost-effectiveness of the mindfulness-based stress reduction methodology. Mindfulness. 2015;6(6):1379–1386. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0408-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li W., Wei D., Chen Q., Jackson T., Zhang Q., Qiu J. Examining brain structures associated with perceived stress in a large sample of young adults via voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2014;92:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Mei Liao R., Carey M.G. Laboratory-induced mental stress, cardiovascular response, and psychological characteristics. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015;16:28–35. doi: 10.3909/ricm0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas T., Ivtzan I., Fu C.H. A systematic review of the neurophysiology of mindfulness on EEG oscillations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015;57:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond S.H., Lovibond P.F. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychol. Found. Austr. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Lupien S.J., McEwen B.S., Gunnar M.R., Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10(6):434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magezi D.A. Linear mixed-effects models for within-participant psychology experiments: an introductory tutorial and free, graphical user interface (LMMgui) Front. Psychol. 2015;6:2. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroufizadeh S., Foroudifard F., Navid B., Ezabadi Z., Sobati B., Omani-Samani R. The perceived stress scale (PSS-10) in women experiencing infertility: a reliability and validity study. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2018;23(4):456–459. [Google Scholar]

- Matousek R.H., Pruessner J.C., Dobkin P.L. Changes in the cortisol awakening response (CAR) following participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction in women who completed treatment for breast cancer. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2011;17(2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B.S. Effects of adverse experiences for brain structure and function. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIndoo C.C., File A.A., Preddy T., Clark C.G., Hopko D.R. Mindfulness-based therapy and behavioral activation: a randomized controlled trial with depressed college students. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016;77:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.J., Fletcher K., Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 1995;17(3):192–200. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00025-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais P., Quaresma C., Vigário R., Quintão C. Electrophysiological effects of mindfulness meditation in a concentration test. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2021:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11517-021-02332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan J.A., Chapman B.P., Klorman R., Krasner M.S., Duberstein P.R., Brown K.W., Talbot N.L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for older adults: effects on executive function, frontal alpha asymmetry and immune function. Neuropsychobiology. 2013;68(1):34–43. doi: 10.1159/000350949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K.T., Liang W.-K., Lee V., Chang W.-S., Muggleton N.G., Yeh J.-R., Huang N.E., Juan C.-H. Unraveling nonlinear electrophysiologic processes in the human visual system with full dimension spectral analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53286-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll M., Sahm L.J., Byrne H., Lambert S., Byrne S. Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on undergraduate pharmacy students’ stress and distress: quantitative results of a mixed-methods study. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019;11(9):876–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall J.E., Tonidandel S. A two-stage analysis of repeated measurements with dropouts and/or intermittent missing data. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006;62(3):285–291. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palouse, M. 〈https://palousemindfulness.com/MBSR/manual.html〉.

- Papagiannopoulou E.A., Lagopoulos J. Resting state EEG hemispheric power asymmetry in children with dyslexia [original research] Front. Pediatr. 2016;4 doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T., Bui L., Nguyen A., Nguyen B., Tran P., Vu P., Dang L. The prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among medical students: an untold story in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham Tien N., Pham Thanh T., Nguyen Hanh D., Duong Hoang A., Bui Dang The A., Kim Bao G., Dang Huong G., Thi Thu H.N., Pham Ngoc H., Nguyen Thi Thanh H. Utilization of mental health services among university students in Vietnam. Int. J. Ment. Health. 2020:1–23. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2020.1816114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn A.J., Lopes-Dos-Santos V., Dupret D., Nobre A.C., Woolrich M.W. EMD: empirical mode decomposition and Hilbert-Huang spectral analyses in python. J. Open Source Softw. 2021;6(59):2977. doi: 10.21105/joss.02977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti J.W., Harrington L.N., Storch E.A. Further psychometric support for the 10–item version of the perceived stress scale. J. Coll. Couns. 2006;9(2):135–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saggar M., King B.G., Zanesco A.P., Maclean K.A., Aichele S.R., Jacobs T.L., Bridwell D.A., Shaver P.R., Rosenberg E.L., Sahdra B.K., Ferrer E., Tang A.C., Mangun G.R., Wallace B.A., Miikkulainen R., Saron C.D. Intensive training induces longitudinal changes in meditation state-related EEG oscillatory activity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012;6 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammler D., Grigutsch M., Fritz T., Koelsch S. Music and emotion: electrophysiological correlates of the processing of pleasant and unpleasant music. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(2):293–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S.-H., Lee J.-T. Stress and EEG. Converg. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 2010;1(1):413–424. doi: 10.5772/9651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Lindquist R. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today. 2015;35(1):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlak M., Bob P., Cernik M., Kukleta M. Electrodermal complexity during the Stroop colour word test. Auton. Neurosci. 2010;152(1–2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Murata T., Hamada T., Omori M., Kosaka H., Kikuchi M., Yoshida H., Wada Y. Changes in EEG and autonomic nervous activity during meditation and their association with personality traits. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2005;55(2):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-Y., Ma Y., Fan Y., Feng H., Wang J., Feng S., Lu Q., Hu B., Lin Y., Li J., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Zhou L., Fan M. Central and autonomic nervous system interaction is altered by short-term meditation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(22):8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904031106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S.Y., Jaiswal S., Chang C.F., Liang W.K., Muggleton N.G., Juan C.H. Meditation effects on the control of involuntary contingent reorienting revealed with electroencephalographic and behavioral evidence. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2018;12:17. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2018.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiyama K., Ogawa T., Ishii M., Ajisaka R., Sugishita Y., Ito I. Physiologic neuroendocrine arousal by mental arithmetic stress test in healthy subjects. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991;67(1):101–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgili M. Mindfulness-based interventions reduce psychological distress in working adults: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):326–337. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0264-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen P., Gommers R., Oliphant T.E., Haberland M., Reddy T., Cournapeau D., Burovski E., Peterson P., Weckesser W., Bright J., van der Walt S.J., Brett M., Wilson J., Millman K.J., Mayorov N., Nelson A.R.J., Jones E., Kern R., Larson E., SciPy C., et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods. 2020;17(3):261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Sourina O. Real-time mental arithmetic task recognition from EEG signals. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehab. Eng. 2013;21(2):225–232. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2236576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenner C., Herrnleben-Kurz S., Walach H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis [original research] Front. Psychol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.-x., Wu, X.-p., Guo, X.-j., 2008. The EEG signal preprocessing based on empirical mode decomposition. In: Proceedings of the 2008 2nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering.

- Zhao G., Zhang Y., Ge Y. Frontal EEG asymmetry and middle line power difference in discrete emotions [original research] Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018;12 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material