Abstract

This study was designed to determine whether isolates from chicken carcasses, the primary source of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in human infections, commonly carry the cdt genes and also whether active cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) is produced by these isolates. Campylobacter spp. were isolated from all 91 fresh chicken carcasses purchased from local supermarkets. Campylobacter spp. were identified on the basis of both biochemical and PCR tests. Of the 105 isolates, 70 (67%) were identified as C. jejuni, and 35 (33%) were identified as C. coli. PCR tests amplified portions of the cdt genes from all 105 isolates. Restriction analysis of PCR products indicated that there appeared to be species-specific differences between the C. jejuni and C. coli cdt genes, but that the restriction patterns of the cdt genes within strains of the same species were almost invariant. Quantitation of active CDT levels produced by the isolates indicated that all C. jejuni strains except four (94%) had mean CDT titers greater than 100. Only one C. jejuni strain appeared to produce no active CDT. C. coli isolates produced little or no toxin. These results confirm the high rate of Campylobacter sp. contamination of fresh chicken carcasses and indicate that cdt genes may be universally present in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from chicken carcasses.

Campylobacter spp. are recognized as one of the most common causes of bacterial enteritis in the United States (2). There are several different Campylobacter species, but the most frequently identified pathogen from diarrheal cases of infection in humans is C. jejuni (1, 19, 33). The closely related species C. coli is less frequently a cause of human disease. The relative frequencies of isolation of these two species from humans with disease have varied in different reports, but C. coli appears to represent between 3% (8) and 10% (1) of Campylobacter isolates. Other species, such as C. lari (18, 32) and C. fetus (9), which can also cause human disease, appear to do so less frequently than C. jejuni and C. coli (17).

It is now well established that a primary source of Campylobacter spp. in human disease in the United States is contaminated chicken carcasses (3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 15, 21, 28, 33). C. jejuni, C. coli, and, to a lesser extent, C. lari inhabit the chicken intestinal tract without causing apparent health problems for the chickens (1). During slaughter and in subsequent processing steps, poultry carcasses may become contaminated with these Campylobacter spp.; the reported incidence of Campylobacter spp. on poultry carcasses has ranged from less than 2% (27) to as high as 100% (11). Human disease likely results from improper handling or incomplete cooking of the contaminated carcasses (1).

C. jejuni and C. coli have been reported to produce a number of apparently different toxin activities, yet to date, only one of these activities, cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), has been genetically defined (25). CDT production by Campylobacter spp. was first described by Johnson and Lior in 1988 (14). They reported that CDT activity in culture supernatants caused several cultured cell lines, including HeLa and Vero cells, to become slowly distended over a 2- to 4-day period, after which the cells disintegrated. The activity was nondialyzable and sensitive to heat and trypsin (14). Johnson and Lior also reported that CDT appeared to be produced by only some strains of C. jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, and C. fetus, but there did not appear to be any correlation between production of CDT and biotype, serotype, or strain source (14).

The C. jejuni cdt genes have been cloned and sequenced (25). CDT activity is encoded by three adjacent genes, cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC, which encode proteins predicted to have molecular weights of about 30,000, 29,000, and 21,000, respectively. The specific functions of the Cdt proteins are unknown; the predicted amino acid sequences are unlike those of any of the proteins in available databases (25). However, Whitehouse et al. (36) recently reported that C. jejuni CDT causes HeLa cells to become blocked in the G2 phase of the cell cycle. The actual target of CDT remains undiscovered.

CDT titers, as determined in a HeLa cell assay, for 20 C. jejuni strains and 12 C. coli strains were reported by Pickett et al. (25). All of the C. jejuni strains produced CDT, suggesting that CDT production by C. jejuni isolates might be more prevalent than previously reported. The C. coli strains appeared to make little if any active CDT, although hybridization studies with C. coli strains indicated that cdt sequences were present (25). However, none of the strains tested had been isolated from chickens (25). Since contaminated chicken meat is apparently a leading source of Campylobacter sp. infection of humans, and since there is no information available about the prevalence of cdt genes in C. jejuni and C. coli strains isolated from chicken meat, we decided to isolate Campylobacter spp. from fresh chicken carcasses. The isolates were then tested for the presence of cdt genes and for the production of active CDT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Poultry samples.

Ninety-one fresh chicken carcasses were purchased from four local supermarkets in June, July, and August of 1996 and 1997. The chickens used in this work came from three different, widely available, suppliers. Each chicken carcass, in its original package, was placed onto an individual polyethylene bag and transferred to the laboratory in a cool box within 1 h of purchase. The temperature of the cool box was maintained at 3 to 5°C. Immediately after arrival at the laboratory, each carcass was placed into a separate sterile plastic bag by using fresh, sterile disposable gloves.

Isolation and identification of Campylobacter spp.

The isolation procedure for Campylobacter from whole meat carcasses was based on the procedure described by Hunt and Abeyta (13). A rinse of 200 ml of 0.1% sterile peptone water was added to the sterile polyethylene bags containing individual chicken carcasses. The sealed bags were hand massaged for 3 min. The rinse solution was subsequently filtered through sterile cheesecloth and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was discarded, and the pellet was suspended in 12 ml of 0.1% peptone water. For preenrichment, 3 ml of the suspended pellet was inoculated into 100 ml of Hunt broth and incubated microaerobically (85% nitrogen, 10% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide) at 30°C for 3 h with agitation (150 to 200 rpm on a Model 50 waterbath [Precision Sci., Winchester, Va.]) and then at 37°C for 2 h with agitation. This was followed by a 24-h enrichment in which the cultures were transferred to a 37°C microaerobic incubator and incubated without shaking. Fifty-microliter aliquots of enriched sample were streaked onto CCDA and Abeyta-Hunt agars (13), and incubated microaerobically at 42°C for 24 to 48 h. The resultant colonies were examined visually, and at least one presumptive Campylobacter sp. colony per plate was selected for further testing. Colonies that appeared as curved, gull wing-shaped, gram-negative rods were tentatively identified as Campylobacter species and streak purified on Abeyta-Hunt agar. Catalase and oxidase tests were performed, and isolates with the appropriate reactions were identified to the species level. Species identification of all isolates was performed by using both API Campy (Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), and by a species-specific PCR procedure which uses two sets of primers that amplify unique regions of either the C. jejuni or C. coli chromosomes (30, 31). Two isolates, AED974 and AEB9727, which were not definitively identified with API Campy, were also tested for the presence of the hippuricase gene (16) as an additional method for species determination.

Strains and media.

The 105 strains isolated in this work were given strain names consisting of three letters and three or four numbers. The letters AEA, AEB, AEC, and AED, designate the four different markets in which the chickens were purchased; the numbers indicate the year of isolation and a running total of the strains isolated from a given store in a given year. C. jejuni 81-176 has been described previously (25). The cdt genes from this strain have been cloned and sequenced, and they were used as a positive control for C. jejuni cdt genes in this work. C. coli 43473 has also been described previously (25) and was used as a positive control for C. coli strains. Campylobacter isolates were routinely grown on brucella agar as previously described (23). When necessary, selective antibiotics were added to the following final concentrations: cephalothin, 15 μg/ml; vancomycin, 10 μg/ml; trimethoprim, 5 μg/ml. All Campylobacter sp. isolates were stored in brucella broth–15% glycerol at −80°C.

DNA techniques and PCR.

Total bacterial cell DNA was isolated by using a QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.). PCR reagents were obtained from Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, Conn.), and PCR primers were supplied by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa). Chromosomal DNA from C. jejuni or C. coli was used as a template in reactions with either the primers VAT2 and WMI1 or VAT2 and LPF-X. VAT2 and WMI1 (Fig. 1) were described by Pickett et al. (25) and have, respectively, the following nucleotide sequences based on portions of the cdtB genes of E. coli: 5′-GT(ACGT)GC(ACGT)AC(ACGT)TGGAA(CT)CT(AGCT)CA(AG)GG-3′ and 5′-(GA)TT(GA)AA(GA)TC(AGCT)CC(TC)AA(TGA)ATCATCC-3′. LPF-X has the nucleotide sequence 5′-AAA(CT)TG(AC)AC(AGT)TA(AGT)CCAAAAGG-3′ and is based on a conserved amino acid sequence (LPFGYVQ) in the cdtC genes of C. coli D730 and C. jejuni 81-176 (22, 25). All PCR mixtures contained 0.2 mM (each) dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and TTP; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 1× Taq DNA polymerase buffer; 0.25 μM (each) primer; 0.25 μg of template DNA; and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. The parameters for all reactions were 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 42°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min.

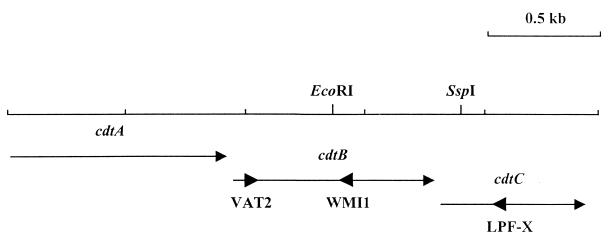

FIG. 1.

C. jejuni 81-176 cdt genes and locations of the PCR primers used in this study. Arrows with small heads indicate the size and direction of transcription of the cdt genes. Large arrowheads indicate the locations and orientations of the primers used to amplify cdt genes.

Toxin assay.

The HeLa cell assays for determination of CDT titers were performed as described by Pickett et al. (24) using sonic lysates of Campylobacter isolates grown overnight on brucella agar plates. The titers of the lysates were determined by performing twofold serial dilutions in 96-well microtiter plates. The titer of a given assay is represented as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that caused at least 50% of the HeLa cells in a well to be distended. Titers were adjusted for differences in cell number by dividing the titer by the A590 of the cells prior to sonication. The CDT titer for each strain is expressed as the geometric mean of three independent HeLa assays.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of Campylobacter spp. from chicken carcasses.

One hundred five Campylobacter isolates were obtained from 91 fresh chicken carcasses; at least 1 Campylobacter sp. isolate was obtained from each carcass. Our isolation procedure was designed to produce one Campylobacter isolate per chicken and was not designed to determine how often more than one species or strain was present on a single carcass. However, if there appeared to be two different colony morphologies on the Abeyta-Hunt or CCDA selection agars, then a representative of both colony types was tested further. This led to the testing of two isolates from 14 of the carcasses; 8 of these chicken carcasses yielded single C. jejuni and C. coli isolates, 5 gave rise to two C. jejuni isolates, and 1 produced two C. coli isolates. Overall, 69 of the 105 isolates (66%) were identified as C. jejuni, and 34 (32%) were identified as C. coli. Two isolates could not be identified to the species level the API Campy identification kit, but two species-specific PCR methods (16, 29, 30) identified one of these as C. jejuni and the other as C. coli (Table 1). More C. jejuni than C. coli isolates were obtained from all stores except one (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of methods of identification of C. jejuni and C. coli isolated from chicken carcasses

| Isolate | No. (%) identified by:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PCR | API | |

| C. jejuni | 70 (67) | 69 (66) |

| C. coli | 35 (33) | 34 (32) |

| Total | 105 | 103a |

Two isolates could not be identified by API Campy.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from four different supermarkets

| Store | No. (%) of isolates:

|

Total no. of isolates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. coli | C. jejuni | ||

| A | 4 (21) | 15 (79) | 19 |

| B | 20 (47) | 23 (53) | 43 |

| C | 3 (100) | 0 | 3 |

| D | 8 (20) | 32 (80) | 40 |

HeLa assay results.

Sixty-nine of the 70 (99%) C. jejuni isolates produced CDT; 65 of these produced mean CDT titers greater than 100 (Table 3). One C. jejuni isolate produced no toxin in repeated HeLa assays. Three C. jejuni isolates produced mean CDT titers ranging from 56 to 87. All of the C. coli isolates had mean CDT titers of less than 100; 30 (86%) had titers less than 5 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Range of CDT titers produced by Campylobacter isolates from chicken carcasses

| Species | No. (%) of isolates with CDT titera:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–100 | 101–400 | 401–800 | >800b | |

| C. coli | 35 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C. jejuni | 5 (7) | 25 (36) | 21 (30) | 19 (27) |

The titers shown represent mean CDT titers calculated as described in Materials and Methods. The division of the mean CDT titers into four groups was done in order to emphasize the differences between C. jejuni and C. coli titers and to illustrate the broad range of C. jejuni CDT titers between 100 and 2,000 represented by these isolates and the lack of any clustering of these titers at a particular level.

The highest mean CDT titer was 2,164 ± 1.

Detection of cdt genes in Campylobacter isolates.

The degenerative primers VAT2 and WMI1 were used to screen for the presence of cdtB sequences in all 105 Campylobacter isolates (Fig. 1). A single product of approximately 0.5 kb was observed in the reactions from 104 of the isolates (Fig. 2). This is very close to the expected size of 494 bp for a product amplified from cdtB by these two primers. Sequencing and hybridization studies (22, 25) have confirmed that the 0.5-kb products from selected C. jejuni and C. coli strains do represent an amplified product from cdtB. The restriction endonuclease fragment patterns produced by EcoRI digestion of the 0.5-kb PCR products were examined, since sequence data indicated that this enzyme cut the relevant portion of the C. jejuni 81-176 cdtB gene, but not the C. coli D730 cdtB gene (22, 25). The 0.5-kb PCR products of all C. jejuni isolates tested were cut once with EcoRI, yielding 0.35- and 0.15-kb fragments (Fig. 2A). None of the C. coli VAT2-WMI1 primer pair PCR products were cut with EcoRI (Fig. 2B).

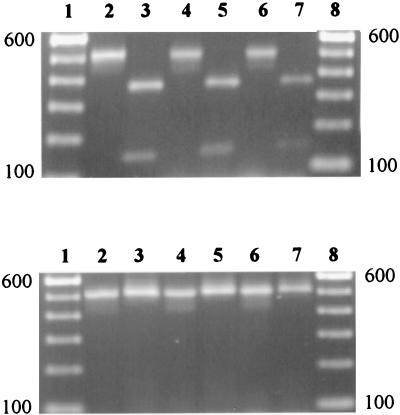

FIG. 2.

EcoRI restriction of VAT2-WMI1 PCR products from representative C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. (A) C. jejuni. Lanes: 1 and 8, 100-bp standard DNA ladder; 2, 4, and 6, uncut PCR products from strains 81-176, AEA962, and AED962, respectively; 3, 5, and 7, EcoRI-cut PCR products from strains 81-176, AEA962, and AED962, respectively. (B) C. coli. Lanes: 1 and 8, 100-bp standard; 2, 4, and 6, uncut PCR products from strains 43473, AEB962, and AED971, respectively; 3, 5, and 7, PCR products from 43473, AEB962, and AED971, respectively, treated with, but uncut by, EcoRI. The locations of the 100- and 600-bp standards are indicated at the sides of the figure.

The C. jejuni isolate for which VAT2-WMI1 did not amplify a product was screened for cdt genes with an alternative PCR mixture in which the downstream primer WMI1 was replaced with another primer, LPF-X (Fig. 1). A 1.05-kb product was amplified with these primers with template DNA from this strain (Fig. 3, lane 4). A similar-size product with use of these primers was seen with template DNA from the C. jejuni control strain, 81-176 (Fig. 3, lane 2). The predicted size for this product was 0.99 kb. SspI digestion of both the AED974 and 81-176 VAT2–LPF-X PCR products yielded fragments with apparent sizes of 0.92 and 0.09 kb, close to the expected sizes of 0.914 and 0.078 kb. Since the VAT2–LPF-X primer pair was the only primer pair that amplified a putative region of the cdt genes from strain AED974, we further verified the identity of the product in a hybridization experiment. The VAT2–LPF-X product from AED974 clearly hybridized to the VAT2–WMI1 product from C. jejuni 81-176 (data not shown).

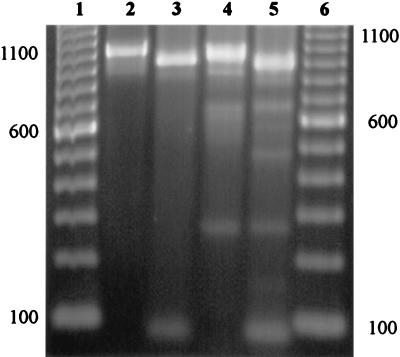

FIG. 3.

VAT2–LPF-X PCR products from C. jejuni 81-176 and AED974 and their restriction by SspI. Lanes: 1 and 6, 100-bp DNA ladders; 2 and 4, uncut PCR products from strains 81-176 and AED974, respectively; 3 and 5, SspI-cut PCR products from strains 81-176 and AED974, respectively. The locations of the 100-, 600-, 1,100-bp standards are indicated at the sides of the figure.

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of this work was to determine the prevalence of cdt genes in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from chicken carcasses. We chose to use PCR as a method for detecting cdt genes and used three different PCR primers in two different combinations. The sequences of the primers were based on a conserved region of the cdtB genes in E. coli and C. jejuni (24, 25, 26) or on a conserved region of the cdtC genes in C. jejuni and C. coli. cdtB sequences were detected in all of the chicken isolates; however, in one case, only one of the two primer sets amplified a portion of the cdt genes. This single C. jejuni isolate, AED974, was the C. jejuni isolate that produced no detectable CDT. It seems likely that there is a mutation(s) in at least a portion of the AED974 cdtB gene that renders it unable to make active toxin and that interferes with the ability of the WMI1 primer to anneal to the cdtB gene. Regardless, we have shown that cdt genes appear to be present in all of the Campylobacter isolates examined in this work and that the PCR primers used here are capable of easily detecting the presence of these genes.

In addition to detecting cdt genes in our isolates, we also assayed all of our C. jejuni and C. coli isolates for CDT production. Nearly all (66 of 70) of our C. jejuni isolates produced significant levels of CDT, yet all of the C. coli strains appeared to produce little or no toxin. These results confirm and extend our previous results, indicating that this difference in toxic activity appears to be found consistently in strains isolated both from humans with disease and from chicken carcasses (25). Whether the differences between the C. jejuni and C. coli CDTs seen in the HeLa assay reflect real differences in the amount of toxin produced, the specific activities of these two toxins, or the HeLa cell sensitivity to the two toxins is not yet known.

We found that 100% of the chickens examined were contaminated with either C. jejuni, C. coli, or both species. Isolation rates of Campylobacter from retail chicken may vary, depending upon the sampling time of the year, number of samples collected, the sampling procedures, isolation methodology, and whether the sample is fresh or frozen (3, 29, 35, 37). Other studies in which whole chicken carcasses purchased at the retail level were sampled for Campylobacter spp. by using sampling procedures similar to ours (4, 6, 15, 20, 21, 28, 34) have reported isolation rates of between 30 and 98%. Whether our relatively high rate is a reflection of increased incidence of Campylobacter spp. on chicken carcasses or results from a combination of optimal sampling season with optimal isolation procedure is not clear.

Most previous studies have not differentiated between C. jejuni and other Campylobacter spp. and instead reported the total Campylobacter isolation rate as the C. jejuni isolation rate, assuming that most of the Campylobacter spp. present would be C. jejuni. In our study, we used two techniques for species identification. The two methods used, the API Campy identification kit and species-specific PCR, were essentially in agreement, except that two isolates were not conclusively identified by the API Campy kit. However, two different PCR methods identified one of these isolates as C. jejuni and the other as C. coli. Taken together, the speciation methods indicated that 67% of our isolates were C. jejuni and 33% were C. coli. No C. lari isolates were obtained. These results certainly tend to confirm that C. jejuni is the predominant Campylobacter sp. present on fresh chicken carcasses, although the percentage of C. coli isolated was substantial, and it seems prudent not to dismiss the amount of C. coli present as insignificant. In addition, since 8 of the 14 chickens from which two isolates were obtained yielded isolates of both species, it may not be uncommon for a single chicken carcass to be contaminated with more than one species or strain of Campylobacter. However, since no systematic investigation of all 91 carcasses for carriage of both species was undertaken, the percentage found here, 57% (8 of 14), may not reflect the actual incidence of more than one Campylobacter sp. present on a single carcass.

It seems clear that cdt genes are likely universally present in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. However, it is not yet known what role CDT plays in food-borne illness. Animal model studies testing strains with defined mutations within their cdt genes will help elucidate the role of CDT in Campylobacter pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AI 41477 from the National Institutes of Health to C.L.P. A.E. was supported by a fellowship from the Turkish Higher Education Council and Uludag University, Bursa, Turkey.

We thank Daniel Cottle for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published with the approval of the Director of the Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station as journal paper no. 98-07-102.

REFERENCES

- 1.ACMSF (Advisory Committee on the Microbiological Safety of Food) Interim report on Campylobacter. London, United Kingdom: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser M J, Reller L B. Campylobacter enteritis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1444–1452. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112103052404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan F L, Doyle M P. Health risks and consequences of Salmonella and Campylobacter jejuni in raw poultry. J Food Prot. 1995;58:326–344. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer E, Hahne M. Cross-contamination with Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella spp. from raw chicken products during food preparation. J Food Prot. 1990;53:1067–1068. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.12.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deming M S, Tauxe R V, Blake P A, Dixon S E, Fowler B S, Jones T S, Lockamy E A, Patton C M, Sikes R O. Campylobacter enteritis at a university: transmission from eating chicken and from cats. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:526–534. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill C O, Harris L M. Hamburgers and broiler chickens as potential sources of human Campylobacter enteritis. J Food Prot. 1984;47:96–99. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-47.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graves T K, Bradley K K, Crutcher J M. Outbreak of Campylobacter enteritis associated with cross-contamination of food-Oklahoma, 1996. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:129–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths P L, Park W A. Campylobacters associated with human diarrheal disease. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:281–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrant R L, Lahita R G, Winn W C, Jr, Roberts R B. Campylobacteriosis in man: pathogenic mechanisms and review of 91 bloodstream infections. Am J Med. 1976;65:584–592. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90845-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris N V, Weiss N S, Nolan C M. The role of poultry and meats in the etiology of Campylobacter jejuni/coli enteritis. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:407–411. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood A M, Pearson A D, Shahamat M. The extent of surface contamination of retailed chickens with Campylobacter jejuni serogroups. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;100:17–25. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800065511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins R S, Scott A S. Handling raw chicken as a source for sporadic Campylobacter jejuni infections. J Infect Dis. 1983;4:770. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.4.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt J M, Abeyta C. Isolation of Campylobacter species from food and water. In: Tomlison L A, editor. Food and Drug Administration bacteriological analytical manual. 8th ed. Baltimore, Md: AOAC Int.; 1995. pp. 7.01–7.27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson W M, Lior H. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Campylobacter spp. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones F T, Axtell R C, Rives D V, Scheideler S E, Tarver F R, Jr, Walker R L, Wineland M J. A survey of Campylobacter jejuni contamination in modern broiler production and processing systems. J Food Prot. 1991;54:259–262. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linton D, Lawson A J, Owen R J, Stanley J. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2568–2572. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2568-2572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishu B, Patton C M, Tauxe R V. Clinical and epidemiologic features of non-jejuni, non-coli Campylobacter species. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L S, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nachamkin I, Stowell C, Skalina D, Jones A M, Hoop R M, Smibert R M. Campylobacter laridis causing bacteremia in an immunosuppressed patient. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:55–57. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods. Campylobacter jejuni/coli, The National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods. Dairy Food Environ Sanit. 1995;15:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oosterom J, Notermans S, Karman H, Engels G B. Origin and prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni in poultry processing. J Food Prot. 1983;46:339–344. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-46.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park C E, Stankiewicz Z K, Lovett J, Hunt J. Incidence of Campylobacter jejuni in fresh eviscerated whole market chickens. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27:841–842. doi: 10.1139/m81-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickett, C. L. Unpublished data.

- 23.Pickett C L, Auffenberg T, Pesci E C, Sheen V L, Jusuf S S D. Iron acquisition and hemolysin production by Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3872–3877. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3872-3877.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickett C L, Cottle D L, Pesci E C, Bikah G. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1046–1051. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1046-1051.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickett C L, Pesci E C, Cottle D L, Russell G, Erdem A N, Zeytin H. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp. cdtB genes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2070–2078. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2070-2078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott D A, Kaper J B. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:244–251. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.244-251.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern N J, Green S S, Thaker N, Krout D J, Chiu J. Recovery of Campylobacter jejuni from fresh and frozen meat and poultry collected at slaughter. J Food Prot. 1984;47:372–374. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-47.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern N J, Hernandez M P, Blankenship L, Deibel K E, Doores S, Doyle M P, Ng H, Pearson M D, Sofos J N, Sveum W H, Westhoff D C. Prevalence and distribution of Campylobacter jejuni in retail meats. J Food Prot. 1985;48:595–599. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-48.7.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern N J, Line J E. Comparison of three methods for recovery of Campylobacter spp. from broiler carcasses. J Food Prot. 1992;55:663–666. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.9.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stonnet V, Guesdon J L. Campylobacter jejuni: specific oligonucleotides and DNA probes for use in polymerase chain reaction-based diagnosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stonnet V, Sicinschi L, Megraud F, Guesdon J L. Rapid detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from clinical specimens using the polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:355–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02116533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tauxe R V, Patton C M, Edmonds P, Barrett T J, Brenner D J, Blake P A. Illness associated with Campylobacter laridis, a newly recognized Campylobacter species. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:222–225. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.2.222-225.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tauxe R V. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L S, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldroup A L, Rathgeber B M, Forsythe R H, Smoot L. Effects of six modifications on the incidence and levels of spoilage and pathogenic organisms on commercially processed post chill broilers. J Appl Poult Res. 1992;1:226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace J S, Stanley K N, Currie J E, Diggle P J, Jones K. Seasonality of thermophilic Campylobacter populations in chickens. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehouse C A, Balbo P B, Pesci E C, Cottle D L, Mirabito P M, Pickett C L. Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin causes a G2-phase cell cycle block. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1934–1940. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1934-1940.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willis W L, Murray C. Campylobacter jejuni seasonal recovery observations of retail market broilers. Poult Sci. 1997;76:314–317. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]