Key Points

Question

Is the use of 5α-reductase inhibitors associated with the risk of dying of prostate cancer in healthy men?

Findings

In this large population-based cohort study of 349 152 men without a previous diagnosis of prostate cancer, users of 5α-reductase inhibitors had a lower prostate cancer mortality after longer treatment durations for their benign prostate hyperplasia.

Meaning

This cohort study found an association between treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitors and reduced mortality in prostate cancer, suggesting that these drugs are safe to use regarding the risk of prostate cancer.

Abstract

Importance

There is evidence that 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), a standard treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia, are associated with a decrease in the incidence of prostate cancer (PCa). However, studies to date have had conflicting results regarding the association with prostate cancer mortality (PCM).

Objective

To evaluate the association of treatment with 5-ARIs with PCM in men without a prior diagnosis of PCa.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study was conducted in Stockholm, Sweden, between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2018, and included 429 977 men with a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test within the study period. Study entry was set to 1 year after the first PSA test. Data were analyzed from September 2021 to December 2021.

Exposures

After their initial PSA test, men with 2 or more newly dispensed prescriptions of 5-ARI, finasteride, or dutasteride were considered 5-ARI users (n = 26 190).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was PCM. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality and PCM.

Results

The study cohort included 349 152 men. The median (IQR) age for those with 2 or more filled prescriptions of 5-ARI was 66 (61-73) years and 57 (50-64) years for those without. The median follow-up time was 8.2 (IQR, 4.9-10) years with 2 257 619 person-years for the unexposed group and 124 008 person-years for the exposed group. The median exposure to treatment with 5-ARI was 4.5 (IQR, 2.1-7.4) years. During follow-up, 35 767 men (8.3%) died, with 852 deaths associated with PCa. The adjusted multivariable survival analysis showed a lower risk of PCM in the 5-ARI group with longer exposure times (0.1-2.0 years: adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.64-1.25; >8 years: adjusted HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.27-0.74). No statistically significant differences were seen in all-cause mortality between the exposed and unexposed group. Men treated with 5-ARIs underwent more PSA tests and biopsies per year than the unexposed group (median of 0.63 vs 0.33 and 0.22 vs 0.12, respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cohort study suggest that there was no association between treatment with 5-ARI and increased PCM in a large population-based cohort of men without a previous PCa diagnosis. Additionally, a time-dependent association was seen with decreased risk of PCM with longer 5-ARI treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether the differences are because of intrinsic drug effects or PCa testing differences.

This cohort study examines the association of treatment with 5α reductase inhibitors with prostate cancer mortality in men without a prior diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Introduction

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) followed by substantial lower urinary tract symptoms affects 50% of men in their 50s and 85% of men in their 80s, impairing their quality of life.1,2 One of the most common and effective treatments of lower urinary tract symptoms in men with BPH is the drug class 5α reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), including finasteride and dutasteride, which have been shown to improve urinary symptoms and decrease the risk of acute urinary retention and BPH-related surgery.3,4 The effect of 5-ARIs is mediated by inhibiting the conversion of testosterone into the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Studies have shown that DHT contributes to the malignant transformation of prostatic tissue, and men with congenital 5α reductase deficiency do not develop prostate cancer (PCa).5

An effective chemoprevention strategy for PCa has been highly demanded for decades, and 2 large randomized clinical trials investigated if 5-ARIs could serve this purpose.6,7 Both trials, the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT)6 and Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events (REDUCE),7 found a lower incidence of low-risk and intermediate-risk PCa in men receiving treatment with 5-ARIs.6,7 However, men in the 5-ARI groups also had an increased incidence of high-risk PCa,6,7 which led to a safety warning by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2011.8 Subsequent analyses of the PCPT data suggested that the increase in high-risk PCa could be associated with detection bias because 5-ARIs reduce the prostate size and increase biopsy detection accuracy.9,10,11,12 Moreover, the 18-year follow-up of PCPT showed no difference in all-cause mortality (ACM),13 and a 25%, nonstatistically significant reduction in prostate cancer mortality (PCM) was seen.14 Still, there is an ongoing debate regarding whether treatment with 5-ARIs is associated with PCM. Most observational studies show no association between treatment with 5-ARI and prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM).15,16,17,18 However, Sarkar et al19 found a significant increase in PCSM in men treated with 5-ARIs. Importantly, to our knowledge, Sarkar et al19 and all other observational studies on the topic to date have only included men with a PCa diagnosis, limiting the possibility to study the association of 5-ARIs with PCM.

Given the current conflicting evidence and widespread use of 5-ARIs, we aimed to investigate the association of treatment with 5-ARIs with PCM in men without a previous PCa diagnosis in a large population-based cohort. We leveraged the access to virtually complete coverage of 5-ARI prescriptions, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests, and prostate biopsies to include men at their first PSA test and enable a prospective follow-up design.

Methods

Data Sources

The individual Swedish personal number was used to link multiple large registries: the Stockholm PSA and Biopsy Register, National Prostate Cancer Register, Prescribed Drug Register, Swedish Death Register, National Patient Register, and Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies. The Stockholm PSA and Biopsy Register is a population-based register with all PSA tests and biopsies from men in Stockholm county since January 2003.20 Additionally, all men prescribed 5-ARIs are recommended to undergo a PSA test before initiating treatment. Consequently, most men in Stockholm county were included in this study. The National Prostate Cancer Register contains the tumor stage and Gleason score for all PCas diagnosed in Sweden.21 The Prescribed Drug Register records data on all prescribed drugs dispensed in pharmacies in Sweden since July 2005 and includes the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code, dose, pack size, number of prescriptions, and date of prescription.22 The Swedish Death Register contains the primary cause of death and contributing causes, which are classified according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), and has an 86%23 to 96%24 accuracy for PCa. The National Patient Register contains hospitalizations and outpatient specialist care visits with ICD-10 codes for diagnoses.25 The Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies has records on educational level, income, and civil status.26 This study was approved by the regional ethics board in Stockholm, Sweden, and informed consent was waived.

Study Population

Men 40 years and older with a PSA test recorded between January 2007 and December 2017 in the Stockholm PSA and Biopsy Register database were identified. The study start was set to 1 year after the first recorded PSA test to reduce reverse causality bias and detection bias. This limited the risk of including men prescribed 5-ARI to treat symptoms that were associated with PCa and men with a diagnosis of PCa because of the clinical investigation before the drug prescription. Men who underwent prior transurethral resection of the prostate or received treatment with 5-ARI before their first recorded PSA test were excluded. Only men without a previous PCa diagnosis could enter the study. Follow-up for all patients was until death, emigration, or end of the study period (December 31, 2018). The end of the study period was set to the last available update of the Swedish Death Register.

Definition of Exposure

First, men with a new finasteride or dutasteride prescription after their initial PSA test were identified. A minimum of 1.5 years between the start of the Prescribed Drug Register and first PSA test was required to ensure no recent prior 5-ARI exposure. The start of exposure to 5-ARI was defined as the second drug expedition date, which reduced the risk of misclassification of men who discontinued use of the drug immediately. Once exposed, men were always considered exposed. Cumulative exposure was categorized as unexposed, 0.1 to 2.0, 2 to 4, 4 to 6, 6 to 8, and 8 years or more of exposure.

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% CIs for the association between 5-ARI use and risk of ACM and PCM. Exposure was treated as a time-dependent covariate. Men could enter the study as exposed or unexposed and change their status from unexposed to exposed at the second 5-ARI prescription, thereby avoiding immortal time bias.27 Time-dependent variables were created with the tmerge, tdc, and cumtdc functions in the survival package in R (R Foundation).28 We estimated cause-specific HRs by censoring follow-up times at the time of death of other causes. The models were adjusted for age, PSA test, previous negative biopsy, family history of PCa, education, civil status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and year of study entry. The PSA levels were normalized by log transformation. All variables were determined at the time of the initial PSA test. The proportional hazards assumption was ensured by inspection of the Schoenfeld residuals for all covariates. Missing data points for education (6.7% missing) and civil status (0.9% missing) were imputed using the chained equation approach with the MICE algorithm in R.29 The imputed data sets (n = 10) were then analyzed separately, and the log HRs were pooled using the Rubin rule.

All 95% CIs were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using R, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Rates of PSA Testing and Biopsies

To examine differences between the exposed and unexposed group in PSA tests per year, biopsies per year, and time from elevated PSA level to biopsy, drug treatment episodes were used. Methods by Pazzagli et al30 were applied to create drug episodes from the Prescribed Drug Register. A PSA level of 3 ng/ml or greater (to convert to μg/L, multiply by 1) was considered elevated.31 The drug episodes were updated each time a prescription was filled, which allowed for a correct adjustment of PSA because treatment with 5-ARIs was associated with a 50% reduction in PSA levels in 3 to 6 months.12,32 The PSA level was doubled if a man had been treated with 5-ARI for at least 3 months and not discontinued use for more than 3 months. Quantile regression was used to obtain adjusted median differences between 5-ARI users and nonusers.

Sensitivity Analysis

To test the assumption that men continued to take 5-ARIs after their second prescription, an additional Cox regression model was created. This model was adjusted for the same variables as in the primary analysis. However, 5-ARI exposure was updated each time the drug prescription was filled, allowing the exposure to cumulate with the number of daily defined doses per filled prescription. Furthermore, a landmark analysis with a landmark set at study entry was created to visualize adjusted survival probabilities.33 Survival probabilities were pooled using the Rubin rule on the log-log scale and then back-transformed to the original scale.34

Results

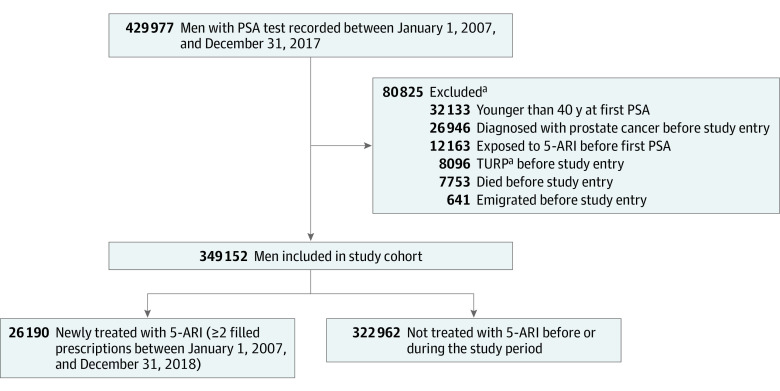

In the final cohort of 349 152 men, 26 190 men were 5-ARI users with 2 or more filled prescriptions during follow-up (Figure 1). Median follow-up time35 was 8.2 (IQR, 4.9-10) years, with 2 257 619 person-years accumulated for the unexposed group and 124 008 person-years for the exposed group. The median exposure to 5-ARI was 4.5 (IQR, 2.1-7.4) years. Men exposed to 5-ARI during the study period were older, more likely to have had a previous negative biopsy, and had higher PSA levels and Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (Table 1). Prostate cancer was diagnosed in 1377 (0.4%) and 14 804 men (4.2%) with vs without 5-ARI exposure, respectively. The exposed group also had higher PSA levels, larger prostates, higher Gleason score, and higher TNM stage at diagnosis (Table 2). A total of 35 767 patients (10.2%) died during follow-up, with 852 deaths attributed to PCa.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Men Included in the Study Cohort.

5-ARI indicates 5α-reductase inhibitor; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate.

aThese categories are not mutually exclusive.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics at Initial PSA Test.

| Characteristic | ≥2 Filled prescriptions of 5-ARI, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| No (n = 322 962) | Yes (n = 26 190) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 57 (50-64) | 66 (61-73) |

| PSA level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 1.00 (0.60-1.80) | 2.90 (1.50-5.20) |

| Previous negative biopsy | 7170 (2.2) | 2756 (11) |

| Prostate cancer in a first-degree relative | 37 985 (12) | 2401 (9.2) |

| Highest level of education obtained | ||

| Elementary school | 53 277 (18) | 4978 (23) |

| High school | 129 556 (43) | 8996 (41) |

| University/college | 120 945 (40) | 7992 (36) |

| Unknown | 19 184 | 4224 |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 126 316 (39) | 8415 (32) |

| Partner | 193 916 (61) | 17 534 (68) |

| Unknown | 2730 | 241 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ||

| 0 | 284 716 (88) | 21 346 (82) |

| ≥1 | 38 246 (12) | 4844 (18) |

| Year of study entry | ||

| 2008-2011 | 193 899 (60) | 22 021 (84) |

| 2012-2015 | 86 702 (27) | 3269 (12) |

| 2016-2018 | 42 361 (13) | 900 (3.4) |

Abbreviations: 5-ARI, 5α-reductase inhibitor; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA to μg/L, multiply by 1.

Table 2. Prostate Cancer Characteristics at Diagnosis.

| Characteristic | ≥2 Filled prescriptions of 5-ARI, No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 14 804) | Yes (n = 1377) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 68 (63-72) | 74 (68-80) | <.001 |

| PSA level, median (IQR), ng/mL | 6 (4-10) | 8 (5-16) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 4257 | 462 | |

| Prostate volume, median (IQR), mL | 38 (29-50) | 46 (34-65) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 4860 | 543 | |

| PSA density, median (IQR), ng/mL/mL | 0.16 (0.11-0.25) | 0.17 (0.10-0.32) | .07 |

| Unknown | 4974 | 583 | |

| Gleason score | |||

| 6 | 4884 (47) | 331 (36) | <.001 |

| 7 | 4342 (41) | 346 (38) | |

| 8-10 | 1242 (12) | 238 (26) | |

| Unknown | 4336 | 462 | |

| Clinical T stage | |||

| 1 | 7144 (68) | 558 (58) | <.001 |

| 2 | 2601 (25) | 269 (28) | |

| 3 | 725 (6.9) | 121 (13) | |

| 4 | 72 (0.7) | 11 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 4262 | 418 | |

| Clinical N stage | |||

| 0 | 2130 (95) | 219 (93) | .17 |

| 1 | 114 (5.1) | 17 (7.2) | |

| Unknown | 12 560 | 1141 | |

| Clinical M stage | |||

| 0 | 8940 (97) | 863 (94) | <.001 |

| 1 | 315 (3.4) | 55 (6.0) | |

| Unknown | 5549 | 459 | |

Abbreviations: 5-ARI, 5α-reductase inhibitor; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA to μg/L, multiply by 1.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test; Pearson χ2 test.

Survival Analyses

In the multivariable Cox regression, there was no evidence of a difference in ACM for any of the 5-ARI exposure levels (0.1-2 years: adjusted HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05; >8 years: adjusted HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.88-1.07) (Table 3). Use of 5-ARI was associated with a decrease in PCM with longer exposure times (0.1-2.0 years: adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.64-1.25; >8 years: adjusted HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.27-0.74) (Table 3). The adjusted differential HR between short (0.1-2.0 years) and long (>8 years) exposure to 5-ARI was 0.50 (95% CI, 0.27-0.91).

Table 3. Association of All-Cause and Prostate Cancer Mortality With Duration of 5-ARI Treatment.

| 5-ARI use, y | No. of Cases | Person-years | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Fully adjusteda | |||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| 0 | 31 304 | 2 257 619 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 0.1-2 | 1175 | 38 347 | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) |

| 2-4 | 1203 | 35 561 | 0.96 (0.90-1.01) | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

| 4-6 | 977 | 24 602 | 1.02 (0.96-1.09) | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) |

| 6-8 | 667 | 15 695 | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 1.01 (0.94-1.10) |

| >8 | 441 | 9803 | 0.96 (0.88-1.06) | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) |

| Prostate cancer mortality | ||||

| 0 | 711 | 2 257 619 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 0.1-2 | 36 | 38 347 | 1.27 (0.91-1.77) | 0.89 (0.64-1.25) |

| 2-4 | 29 | 35 561 | 0.84 (0.58-1.23) | 0.54 (0.37-0.78) |

| 4-6 | 38 | 24 602 | 1.24 (0.89-1.72) | 0.72 (0.52-1.01) |

| 6-8 | 22 | 15 695 | 0.92 (0.60-1.42) | 0.51 (0.33-0.79) |

| >8 | 16 | 9803 | 0.88 (0.53-1.46) | 0.44 (0.27-0.74) |

Abbreviations: 5-ARI, 5α-reductase inhibitor; HR, hazard ratio; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Adjusted for age, PSA level, previous negative biopsy, family history of prostate cancer, education, civil status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and year of study entry.

Diagnostic Activity

Men treated with 5-ARI had more PSA tests per year (median [IQR], 0.63 [0.35-0.99] vs 0.33 [0.19-0.58]) and biopsies per year (median [IQR], 0.22 [0.13-0.42] vs 0.12 [0.09-0.20]) compared with the unexposed group (eTable in the Supplement). Years from elevated PSA levels to biopsy (median [IQR], 1.17 [0.33-2.98] vs 1.20 [0.24-3.44] years) was lower in men treated with 5-ARI than unexposed men. The results persisted in an adjusted analysis, with statistically significant median differences in PSA tests per year, biopsies per year, and time from elevated PSA level to biopsy (eTable in the Supplement).

Sensitivity Analyses

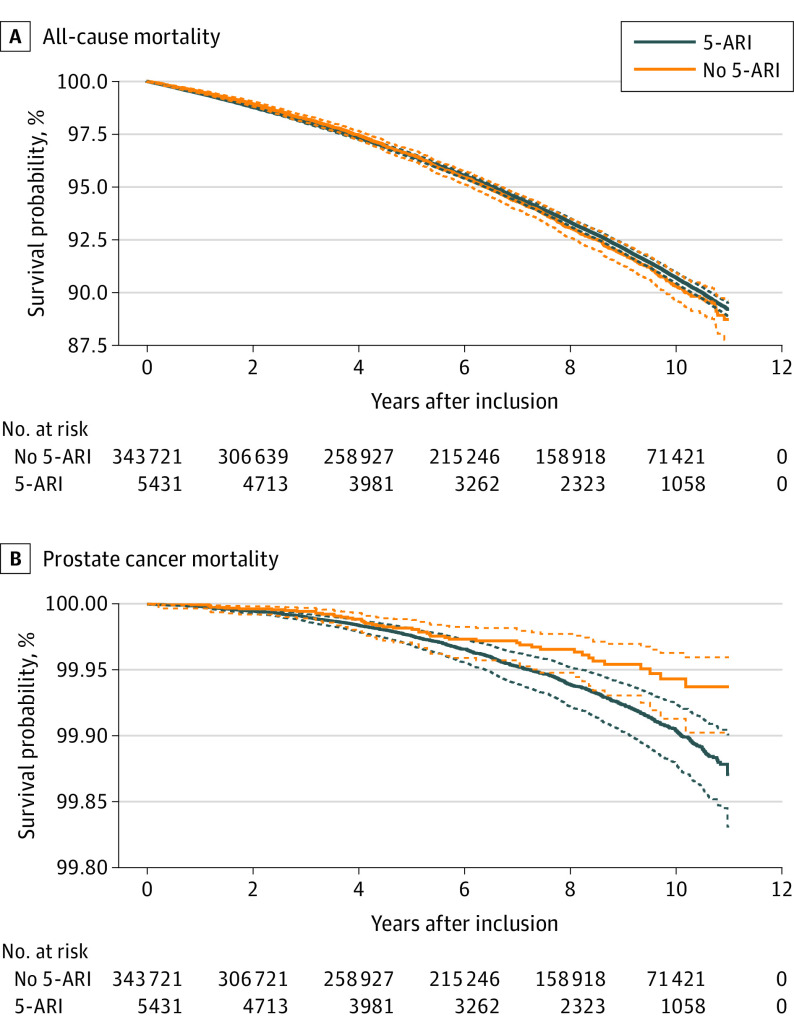

The additional model with time-dependent 5-ARI exposure, which was based on treatment episodes that were updated at each drug expedition, yielded similar results as the primary analysis. There was no difference in ACM (adjusted HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99-1.01). An additional 365 defined daily doses were associated with a decrease in PCM (adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.79-0.88). Finally, the landmark analysis shows no differences in adjusted overall survival probabilities and increased adjusted PCa survival probabilities after 6 years of exposure to 5-ARI (Figure 2).

Figure 2. All-Cause and Prostate Cancer Survival Probabilities in Men Exposed and Unexposed to 5α-Reductase Inhibitors (5-ARIs) at Study Start.

Adjusted for age, prostate-specific antigen levels, previous negative biopsy, family history of prostate cancer, education, civil status, Charlson Comorbidity Index scores, and year of study entry. Solid lines indicate adjusted survival probabilities; dashed lines, 95% pointwise CIs.

Discussion

This large population-based cohort study found a decreased risk of death of prostate cancer in men treated with 5-ARI for more than 2 years for lower urinary tract symptoms compared with men not treated with 5-ARI. Furthermore, men receiving treatment with 5-ARI had significantly higher diagnostic activity, with more PSA tests and prostate biopsies per year compared with nonusers. The study results support previous research7,12,36 showing a decrease in PCa incidence in men treated with 5-ARI. The results suggest the safety of 5-ARI treatment concerning PCM and that the increased grade and stage of PCa at diagnosis for men receiving treatment with 5-ARI are not associated with increased PCM. However, it is still unclear if 5-ARIs inherently suppress or slow the growth of PCa, or if the survival difference is caused by increased and more sensitive testing.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study assessing the association between 5-ARI treatment and PCM in a cohort of men without a previous PCa diagnosis. The observed lower PCM in men treated with 5-ARIs aligns with results from our previous study in the same cohort, which found a decreased risk of PCa in men treated with 5-ARIs.36 Although the 18-year follow-up of the randomized PCPT trial was underpowered to detect significant differences in PCM, its results indicated a 25% decrease in PCM in men treated with finasteride (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.50-1.12).14 Previous observational studies have identified men with PCa and then assessed exposure to 5-ARI before diagnosis.15,16,19 While this design may have been appropriate for their specific research questions, it was not optimal for evaluating the association of 5-ARI with PCM because the analysis only included men with diagnosed PCa. Specifically, a retrospective population-based cohort study by Azoulay et al15 found no significant association or dose-response relationship between 5-ARI and PCSM (adjusted HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.69-1.06). However, this study included only 574 patients who were exposed to 5-ARI, and the drug registry used contained only prescriptions from general practitioners, increasing the risk of misclassification of exposure. Further, Bonde et al16 found, in a similar cohort to the present study, no association between 5-ARI exposure and PCSM. However, their study was designed to investigate whether 5-ARI exposure is associated with prostate histopathology, which was achieved by stratifying the analysis by Gleason score. Additionally, HRs were adjusted for treatment modality, which could create an overadjustment bias because it directly affects the outcome.37 In summary, the overall evidence shows that men taking 5-ARI have a reduced risk of receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer, with unclear implications on the risk of dying of PCa. However, the present study and follow-up analyses from the PCPT trial indicate a possible time-dependent association between 5-ARI and decreased PCM. Furthermore, there is evidence that androgens are associated with carcinogenesis in prostate cancer, with DHT binding to the androgen receptor and inducing DNA synthesis and cell proliferation, and men with congenital 5-ARI deficiency not developing PCa.5,38 Given the nonrandomized design, we cannot determine if this is a causal relationship or whether it could result from detection bias or residual confounding.

The study results suggested that men receiving treatment with 5-ARI had a significantly higher diagnostic activity, with more PSA tests and prostate biopsies per year and a shorter time from elevated (adjusted for 5-ARI exposure) PSA levels to biopsy than nonusers. Contrary to our results, Sarkar et al19 observed a significantly lower diagnostic activity with extended time from an elevated PSA level to prostate biopsy in men receiving treatment with 5-ARI (median [IQR], 3.60 [1.79-6.09] vs 1.40 [0.38-3.27] years) in a cohort study of men within the Veterans Association (VA) with PCa. Additionally, they found an increased PCSM that was associated with 5-ARI (adjusted HR, 1.39; 95% Cl, 1.27-1.52). However, although a 50% reduction in PSA values for men receiving treatment with 5-ARI takes 3 to 6 months to materialize and increases if treatment is stopped,32,39 PSA values were immediately adjusted, which increased the risk of adjusting PSA values for men who were not being treated with 5-ARIs. Also, the study was performed within the VA medical system and thus did not include PSA tests, biopsies, or drug prescriptions from other clinicians, increasing the risk of misclassification.19 A possible explanation for the observed diagnostic differences in this study population could be that men receiving treatment with 5-ARI had more frequent contact with urologists, which was associated with receiving more frequent PSA tests and biopsies. Another possibility is that the higher initial PSA levels in the 5-ARI group triggered additional monitoring. The increased surveillance of men receiving treatment with 5-ARI could explain the observed decrease in PCM in this cohort.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study are its population-based design, large study cohort, long-term follow-up, and the comprehensive registries used. Previous observational studies on the association of 5-ARI treatments with PCM included the start of follow-up at the diagnosis of PCa. By contrast, we identified men before their diagnosis, which is the only way to study mortality as men without prostate cancer otherwise are excluded and do not accumulate follow-up time. We correctly identified men treated with 5-ARI and reduced misclassification by using registries with close to complete coverage. Irreversibly classifying men treated with 5-ARI as exposed after 2 filled prescriptions also reduced bias created by men who received a diagnosis of PCa discontinuing use of the drug. With the complete data on drug prescriptions, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis using treatment episodes to expand on the primary intention-to-treat analysis to confirm our results, further reducing the risk of misclassification. Furthermore, the landmark analysis graphically showed how the PCa survival probabilities are higher for men treated with 5-ARI after 6 years of treatment. Finally, we reduced reverse causality bias by including the men 1 year after their first PSA test because men should undergo PSA testing before a new 5-ARI prescription.

However, this study has some limitations. Although the data set included all men in Stockholm with PSA tests, there may be a selection bias, especially because men taking 5-ARI are more likely to have had a PSA test. Additionally, we lack data on confounders, such as body mass index and alcohol and tobacco use, potentially creating residual confounding for which we could not adjust. Also, there is some evidence connecting BPH to PCa, and Alcaraz et al40 suggested that inflammatory processes may be the common instigator. This could lead to an issue with confounding by indication in our study. However, no evidence points to BPH in reducing the risk of PCa, which reduces the risk of this study bias.40,41 While it is likely that men were taking the drug during the treatment episodes, we cannot guarantee this because we do not have data on serum drug levels. The risk of this affecting our study is reduced because the sensitivity analysis with cumulative drug use points in the same direction as the main study. It is unlikely that a man who does not take the drug would keep filling his prescriptions. Men using 5-ARI have increased diagnostic activity with biopsies and PSA tests, possibly leading to earlier interventions caused by more frequent visits to the urologist. Diagnostic activity may also differ between populations, decreasing the generalizability of this study. Finally, cause of death can be difficult to determine even if the Swedish Death Register has a high accuracy for PCa mortality.

Conclusions

The results of this cohort study suggest that men treated with 5-ARI had no increased risk of dying of prostate cancer, instead indicating a decreased risk with longer treatment duration. Additionally, 5-ARI was associated with increased diagnostic activity by PSA testing and prostate biopsies. Altogether, the results suggest that 5-ARIs are safe and effective to use. Combined evidence from this study, randomized trials, and other observational studies suggest that treatment with 5-ARI does not increase the risk of prostate cancer and may decrease the risk of dying of PCa. Future research may extend this work by separating the inherent effects on PCM of 5-ARI from differences in diagnostic activity with an interventional design, thereby reducing biases that affect observational studies.

eTable. Diagnostic activity in men exposed and unexposed to 5-ARI

References

- 1.Guess HA, Arrighi HM, Metter EJ, Fozard JL. Cumulative prevalence of prostatism matches the autopsy prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate. 1990;17(3):241-246. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto T, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in four countries. Urology. 1998;51(3):428-436. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00717-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoner E. Three-year safety and efficacy data on the use of finasteride in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1994;43(3):284-292. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90068-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. ; Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group . The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(9):557-563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imperato-McGinley J, Guerrero L, Gautier T, Peterson RE. Steroid 5alpha-reductase deficiency in man: an inherited form of male pseudohermaphroditism. Science. 1974;186(4170):1213-1215. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4170.1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(3):215-224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, et al. ; REDUCE Study Group . Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1192-1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theoret MR, Ning YM, Zhang JJ, Justice R, Keegan P, Pazdur R. The risks and benefits of 5α-reductase inhibitors for prostate-cancer prevention. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1106783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akduman B, Crawford ED. The PCPT: new findings, new insights, and clinical implications for the prevention of prostate cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2006;5(9):634-639. doi: 10.1016/j.eursup.2006.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucia MS, Epstein JI, Goodman PJ, et al. Finasteride and high-grade prostate cancer in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(18):1375-1383. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinsky P, Parnes H, Ford L. Estimating rates of true high-grade disease in the prostate cancer prevention trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2008;1(3):182-186. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-07-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson IM, Chi C, Ankerst DP, et al. Effect of finasteride on the sensitivity of PSA for detecting prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(16):1128-1133. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson IM Jr, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Long-term survival of participants in the prostate cancer prevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):603-610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Darke AK, et al. Long-Term effects of finasteride on prostate cancer mortality. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):393-394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1809961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azoulay L, Eberg M, Benayoun S, Pollak M. 5α-reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer-related mortality in men with prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(3):314-320. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonde Miranda T, Garmo H, Stattin P, Robinson D. 5α-Reductase inhibitors and risk of prostate cancer death. J Urol. 2020;204(4):714-719. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murtola TJ, Karppa EK, Taari K, Talala K, Tammela TLJ, Auvinen A. 5-Alpha reductase inhibitor use and prostate cancer survival in the Finnish Prostate Cancer Screening Trial. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2820-2828. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Rompay MI, Curtis Nickel J, Ranganathan G, et al. Impact of 5α-reductase inhibitor and α-blocker therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia on prostate cancer incidence and mortality. BJU Int. 2019;123(3):511-518. doi: 10.1111/bju.14534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarkar RR, Parsons JK, Bryant AK, et al. Association of treatment with 5α-reductase inhibitors with time to diagnosis and mortality in prostate cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):812-819. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordström T, Aly M, Clements MS, Weibull CE, Adolfsson J, Grönberg H. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is prevalent and increasing in Stockholm County, Sweden, despite no recommendations for PSA screening: results from a population-based study, 2003-2011. Eur Urol. 2013;63(3):419-425. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. ; NPCR and PCBaSe Sweden . Cohort profile: the national prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):956-967. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726-735. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fall K, Strömberg F, Rosell J, Andrèn O, Varenhorst E; South-East Region Prostate Cancer Group . Reliability of death certificates in prostate cancer patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42(4):352-357. doi: 10.1080/00365590802078583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godtman R, Holmberg E, Stranne J, Hugosson J. High accuracy of Swedish death certificates in men participating in screening for prostate cancer: a comparative study of official death certificates with a cause of death committee using a standardized algorithm. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45(4):226-232. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.559950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Board of Health and Welfare . The National Patient Register. Accessed April 6, 2021. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/the-national-patient-register/

- 26.Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(4):423-437. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(4):492-499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Therneau T, Crowson C, Atkinson E. Using time dependent covariates and time dependent coefficients in the Cox model. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/timedep.pdf

- 29.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Software. 2010;45(3):1-67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pazzagli L, Brandt L, Linder M, et al. Methods for constructing treatment episodes and impact on exposure-outcome associations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(2):267-275. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02780-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regionala Cancercentrum i Samverkan . Nationellt vårdprogram prostatacancer. 2021. https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/prostatacancer/vardprogram/nationellt-vardprogram-prostatacancer.pdf

- 32.Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC, et al. ; The Finasteride Study Group . The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(17):1185-1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjölander A. A cautionary note on extended Kaplan-Meier curves for time-varying covariates. Epidemiology. 2020;31(4):517-522. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall A, Altman DG, Holder RL, Royston P. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(4):343-346. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(96)00075-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallerstedt A, Strom P, Gronberg H, Nordstrom T, Eklund M. Risk of prostate cancer in men treated with 5a-reductase inhibitors-a large population-based prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(11):1216-1221. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):488-495. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsing AW, Reichardt JKV, Stanczyk FZ. Hormones and prostate cancer: current perspectives and future directions. Prostate. 2002;52(3):213-235. doi: 10.1002/pros.10108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andriole GL, Guess HA, Epstein JI, et al. Treatment with finasteride preserves usefulness of prostate-specific antigen in the detection of prostate cancer: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Urology. 1998;52(2):195-201. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00184-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alcaraz A, Hammerer P, Tubaro A, Schröder FH, Castro R. Is there evidence of a relationship between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer? findings of a literature review. Eur Urol. 2009;55(4):864-873. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ørsted DD, Bojesen SE. The link between benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10(1):49-54. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Diagnostic activity in men exposed and unexposed to 5-ARI