Abstract

Ketamine is analgesic at anesthetic and subanesthetic doses, and used recently to treat depression. Biotransformation mediates ketamine effects, influencing both systemic elimination and bioactivation. CYP2B6 is the major catalyst of hepatic ketamine N-demethylation and metabolism at clinically relevant concentrations. Numerous CYP2B6 substrates contain halogens. CYP2B6 readily forms halogen-protein (particularly Cl-π) bonds, which influence substrate selectivity and active site orientation. Ketamine is chlorinated, but little is known about metabolism of halogenated analogs. This investigation evaluated halogen substitution effects on CYP2B6-catalyzed ketamine analogs N-demethylation in vitro, and modeled interactions with CYP2B6 using various computational approaches. Ortho phenyl ring halogen substituent changes caused substantial (18-fold) differences in Km, on the order Br (bromoketamine, 10 μM)< Cl <F <H (deschloroketamine, 184 μM). In contrast, Vmax varied minimally (83–103 pmol/min/pmol CYP). Thus apparent substrate binding affinity was the major consequence of halogen substitution and the major determinant of N-demethylation. Docking poses of ketamine and analogs were similar, sharing a π-stack with F297. Libdock scores were deschloroketamine < bromoketamine < ketamine < fluoroketamine. A Bayesian log Km model generated with Assay Central had a ROC of 0.86. The probability of activity at 15μM for ketamine and analogs was predicted with this model. Deschloroketamine scores corresponded to the experimental Km, but the model was unable to predict activity with fluoroketamine. The binding pocket of CYP2B6 also suggested a hydrophobic component to substrate docking, based on a strong linear correlation (R2=0.92) between lipophilicity (AlogP) and metabolism (log Km) of ketamine and analogs. This property may be the simplest design criteria to use when considering similar compounds and CYP2B6 affinity.

Keywords: ketamine, halogen, cytochrome P450, CYP2B6, substrate modeling

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic, in clinical use since 1970, and is listed as a World Health Organization Essential Medicine. Ketamine is analgesic at anesthetic and subanesthetic doses, and causes hypnosis, amnesia and sedation with minimal respiratory system depression.1

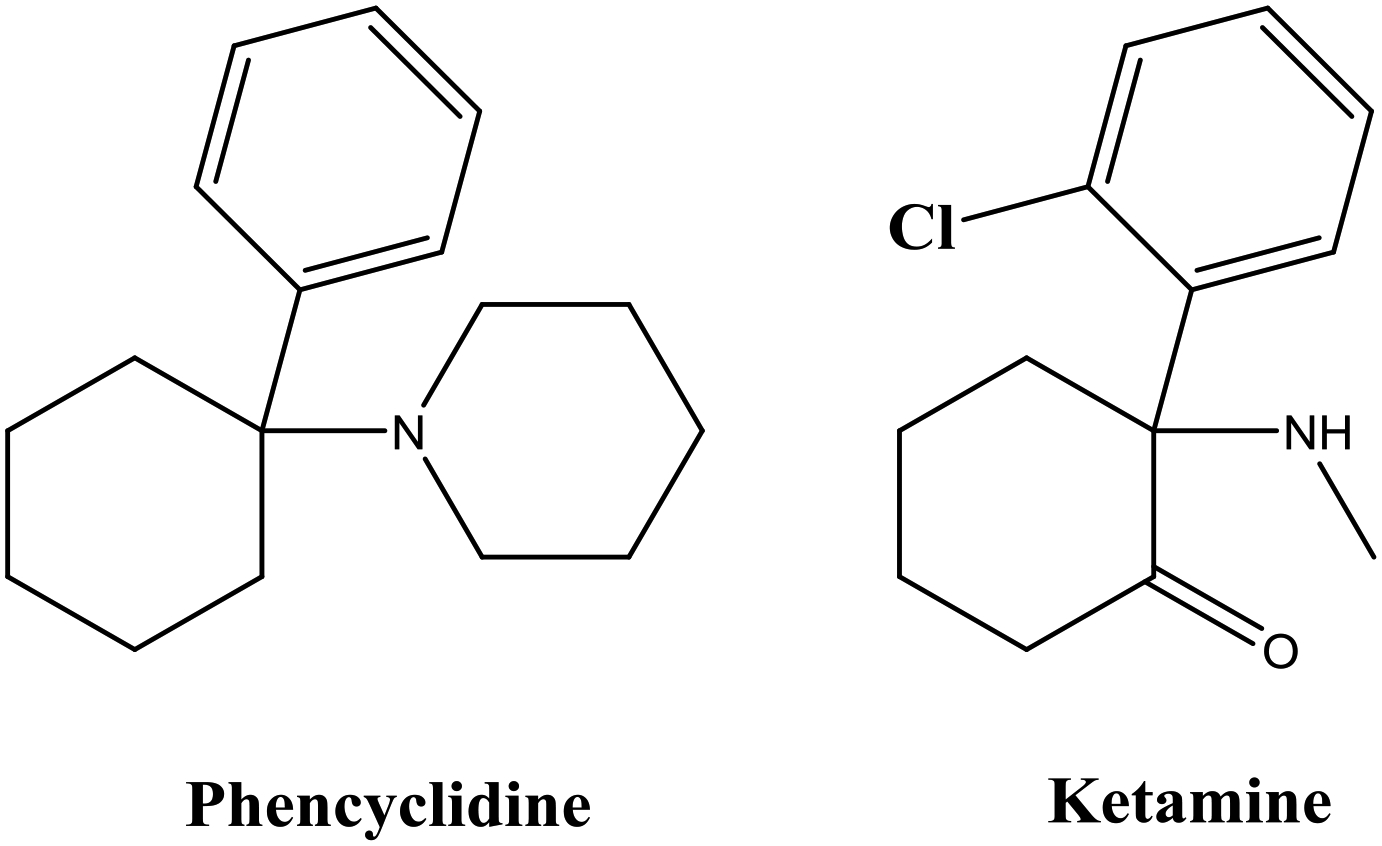

Ketamine was initially synthesized as a derivative of phencyclidine (PCP, 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)piperidine).2–4 Phencyclidine was developed in the 1950s by Parke Davis as a general anesthetic,5 but was discontinued in 1965 due to undesirable side effects including hallucination and neurotoxicity. A series of related arylcyclohexylamine compounds was synthesized in the search for a safer alternative.3, 4 One of the compounds, 2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-(methylamino)cyclohexan-1-one, was an excellent anesthetic (scheme 1). It was named ketamine for its two functional groups (ketone and amine). Ketamine has three structural differences compared to phencyclidine: the piperidino changed to a methylamino group, introduction of a ketone on the cyclohexyl ring, and chlorine addition to the phenyl ring. Ketamine binds to the activated open ion channel of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), causing uncompetitive blockade.6 Therapeutic applications for ketamine have recently expanded, to include severe and treatment-resistant major depression, with rapid and sustained response.7–10

Scheme 1.

Ketamine was initially synthesized as a derivative of phencyclidine.

Biotransformation plays a seminal role in the clinical effects of ketamine, influencing both systemic elimination and bioactivation. Ketamine undergoes extensive hepatic N-demethylation to the predominant metabolite norketamine.1, 11 Norketamine and the other primary metabolite hydroxyketamine are both further metabolized by hydroxylation and N-demethylation, respectively, to hydroxynorketamine. Norketamine is also further metabolized to dehydronorketamine. Drug interactions which alter hepatic ketamine metabolism greatly influence systemic ketamine concentrations.12–14 Oral ketamine undergoes considerable first-pass metabolism, and is consequently only 15% bioavailable.1 Metabolism also influences the molecular pharmacology of ketamine. Norketamine and hydroxynorketamine are pharmacologically active and may contribute to the antidepressant and/or analgesic effects of ketamine, possibly through NMDA or α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptors.15–18 Ketamine N-demethylation is catalyzed by both CYP2B6 and CYP3A4, however these are high-affinity (low Km) and low-affinity (high Km) isoforms, respectively, and CYP2B6 is the major catalyst in vitro of hepatic ketamine N-demethylation, norketamine hydroxylation, and ketamine metabolism overall, at clinically relevant concentrations,19–24 as well as clinically.13 Ketamine N-demethylation by CYP2B6 is also the first step in bioactivation to a putative active metabolite, hydroxynorketamine.25

Halogen substitution is strategically used in drug design and development, typically to improve drug-target binding affinity and/or selectivity, as well as decrease metabolism.26, 27 The most common organohalogen amongst marketed drugs is chlorine, because heavy organohalogens form hydrogen bonds while organofluorines generally do not. Nevertheless, a recent survey found that in addition to influencing receptor pharmacology, 19% of halogen-protein interactions involved those mediating absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, including P450-catalyzed metabolism and detoxification.27 Indeed, halogenation was suggested as an underused strategy for tuning metabolism and molecular optimization,27 particularly exploiting halogen-π interactions between ligand and protein.28 Because numerous CYP2B6 substrates contain halogens, and this enzyme readily forms halogen-protein (particularly Cl-π) bonds,29 the role of halogen-π bonds in substrate selectivity and active site orientation interactions was recently investigated, using the halogenated monoterpene bornyl bromide and the nonhalogenated analog bornane. These results suggested that such interactions may be unique to the CYP2B family of enzymes within the CYP2 family.28

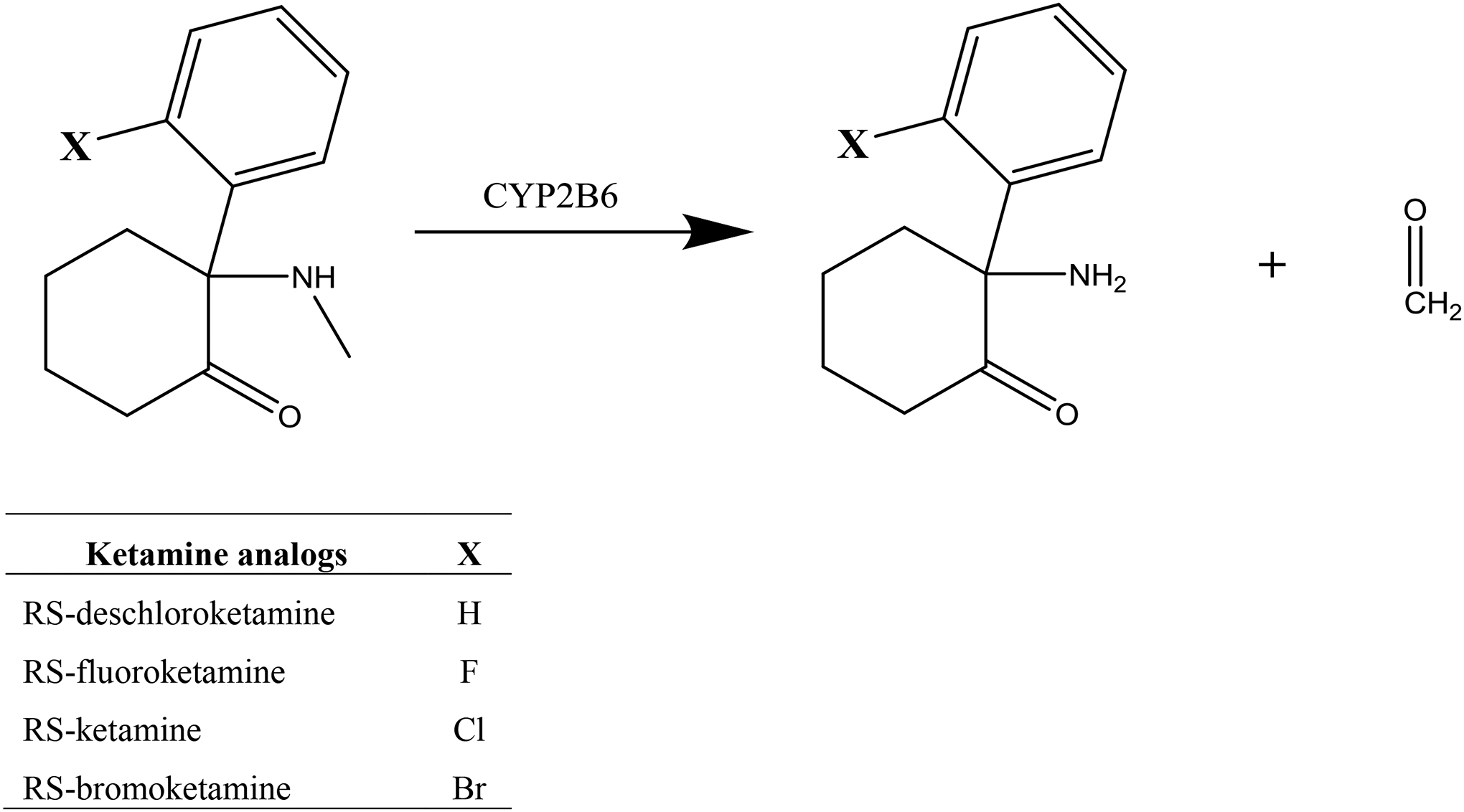

The availability of halogenated and non-halogenated ketamine analogs (Scheme 2) afforded the opportunity to investigate further the influence of halogen substitution on CYP2B6-catalyzed metabolism. The purpose of the current investigation was to directly evaluate halogen substitution effects on ketamine N-demethylation catalyzed by CYP2B6, and attempt to predict the interaction of these variously halogenated analogs with CYP2B6 using various computational approaches.

Scheme 2.

N-demethylation of ketamine analogs catalyzed by CYP2B6.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Formaldehyde, acetylacetone and S-ketamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). R-ketamine was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Racemic RS-ketamine was from Spectrum Chemical Corp (New Brunswick, NJ). Norketamine (d0 and d4) were from Cerilliant (Round Rock, TX). Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells and Sf-900 III SFM culture media were purchased from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA). Trichoplusia ni (Tni) cells, ESF AF culture media, and BestBac 2.0 Baculovirus Cotransfection Kits were from Expression Systems (Davis, CA). BacPAK Baculovirus Rapid Titer Kit was from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). Strata-X 33u (30 mg) solid-phase extraction plates were from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). Other reagents were from SigmaAldrich. Ketamine analogs deschloroketamine (2-phenyl-2-(methylamino)cyclohexan-1-one), fluoroketamine (2-(2-fluorophenyl)-2-(methylamino)cyclohexan-1-one, and bromoketamine (2-(2-bromophenyl)-2-(methylamino)cyclohexan-1-one were synthesized using reported methods.

Generation of recombinant baculoviruses

Production of recombinant human proteins CYP2B6, P450 reductase (POR) and cytochrome b5 was performed as previously described.30 In brief, CYP2B6, POR and b5 genes were amplified from the Human Liver Quick-Clone cDNA library (Clonetech), and inserted individually into the transfer vector pVL1393 using the In-Fusion HD Cloning system (Clontech). Recombinant baculovirus was produced with BestBac 2.0 Baculovirus Cotransfection Kit (Expression Systems). Sf9 insect cells were cotransfected with BestBac linearized DNA and the plasmid DNA of transfer vector carrying the gene of interest on a 6-well plate to produce p0 generation of recombinant baculovirus. Sf9 cells in suspension culture were infected with p0 to make subsequent viral generation. Viral titers were determined using the BacPAK Baculovirus Rapid Titer Kit (Clontech).

Expression of recombinant proteins in insect cells

Protein expression was performed as described previously.30 Briefly, Tni cells in suspension culture in early log phase growth were infected with the recombinant baculoviruses carrying CYP2B6, POR and b5 genes, with multiplicities of infection of 4:2:1 (CYP2B6:POR:b5), in the presence of heme precursors δ-aminolevulinic acid and ferric citrate. After 48 to 72 hr growth post infection, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and stored frozen at −80°C. Frozen cells were thawed and lysed on ice in a Potter-Elvehjem tissue homogenizer and aliquots stored at −80 °C. P450 content, b5 content and POR activity were measured as described previously.30

Ketamine demethylation measured by formaldehyde formation

Ketamine is converted to norketamine and formaldehyde in the primary metabolism step by CYP2B6. The product formaldehyde was measured using Nash reagent for ketamine analog metabolism, while both formaldehyde and norketamine were measured for metabolisms of R-, S-, and RS-ketamine. All incubations were carried out in 96-well PCR plates with raised wells. Ketamine analogs and RS-ketamine with concentrations of 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 700, and 1000 μM was mixed with the enzyme CYP2B6/POR/b5, and preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Substrate concentration range of 0–500 μM was used for enantiomers R- or S-ketamine. Final CYP2B6 concentration was 5 pmol/ml, and total reaction volume was 200 μl in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH7.4. The reaction was initiated by adding an NADPH regenerating system (final concentrations: 10 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 1 mM ß-NADP, 1 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 5 mM magnesium chloride, preincubated at 37°C for 10 min). After incubation for 10 min, the reaction was quenched by adding 40 μl of 15% zinc sulfate, and the plate was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min to remove precipitated proteins and zinc hydroxide. Formaldehyde was measured using a previously described method,31 with minor modifications. A stock solution of 38.8 mM acetylacetone was prepared in 30% (W/V) ammonium acetate. Reaction supernatant (160 μL) was transferred to a new plate, and mixed with 80 μL of 38.8 mM acetylacetone, and incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. The plate was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min and 160 μL supernatant was transferred to a Corning 96-well black polystyrene plate with clear flat bottom, and mixed with 20 μL of 6% (W/V) bovine serum albumin solution. After incubation for 5 minutes, fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation and emission wavelength of 415nm, and 480 nm, respectively, using the Biotek Synergy MX Microplate Reader. For calculation of formaldehyde concentrations, a standard curve was generated using standardized formaldehyde sample. A stock solution of 33 mM formaldehyde was prepared from 37% formaldehyde solution (Sigma Aldrich) and standardized by following a previously described procedure of pH titration,32 Formaldehyde was reacted with excess sodium sulfite by adding 25 mL of 33 mM formaldehyde into 25 mL 0.1 M sodium sulfite, and pH was recorded prior to and after addition of formaldehyde (sodium hydroxide released in the reaction caused pH increase in the range of pH 9–11). Then the mixture was titrated back to the original pH using 0.1 N HCl solution which was prepared from standard 1 N HCl solution (Fisher SA48–1), and the volume of HCl consumption was used to calculate the standard formaldehyde concentration. A series of formaldehyde solutions with concentrations 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 μM were prepared from the standard stock solution. The standard solutions were transferred to the 96-well plate that also carries samples after CYP2B6 incubation. Reaction with acetylacetone and fluorescence measurement were carried out under same conditions as described above.

Ketamine demethylation measured by norketamine formation

Norketamine formation from R-, S-, and RS-ketamine was measured by HPLC/MSMS.30 Substrate concentrations were 0.125–500 μM R- or S-ketamine, and 0.25–1000 μM RS-ketamine. Incubations with CYP2B6 were carried out under the same conditions as described above, except that the reactions were quenched by adding 40 μL 20% trichloroacetic acid containing internal standard norketamine-d4 (final concentration 90 ng/ml). Norketamine concentrations were determined by enantioselective HPLC tandem mass spectrometry using solid-phase extraction, as originally implemented for plasma analysis.11, 30 Calibration standards contained 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000 and 2000 ng/ml racemic norketamine and were processed identically to incubation samples. Stereoselective analysis was performed using a ChiralPak AGP analytical column (100 × 2.0mm, 5μm) and AGP guard column (10 × 2.0mm) (Chiral Technologies, West Chester, PA), coupled to an API 4000 QTrap LC-MS/MS linear ion trap triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Foster City, CA), as described previously.30 Interday coefficients of variation were 5% or less at 5, 50, and 500 ng/ml norketamine, and accuracy was within 5%.

Data Analysis

Results are reported as the mean ± SD of triplicates. Product formation (formaldehyde or norketamine) versus substrate concentration data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis (SigmaPlot 12.5, Systat, San Jose, CA) using single enzyme Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

Docking

Ketamine and all analogs were drawn in XMDS without stereochemistry. Ketamine and all ketamine analogs were prepared using Discovery Studio (Biovia, San Diego, USA) using the default settings. Two stereoisomers were created for each ligand as well as a charged and neutral variant. The crystal structure of cytochrome P4502B6 (3IBD) with inhibitor 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole33 was prepared in Discovery Studio using the default settings (waters removed). A default sized binding pocket was created by selecting the crystallized ligand 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole as an initiation point and creating an input site sphere of 23.6216, 13.8463, 25.7039, 15Å. The docking software Libdock within Discovery Studio was then used to dock the ligands within these constraints. The highest scoring poses were saved as .pdb files and visualized in pymol (Schrodinger,1.8.2.3, New York, NY).

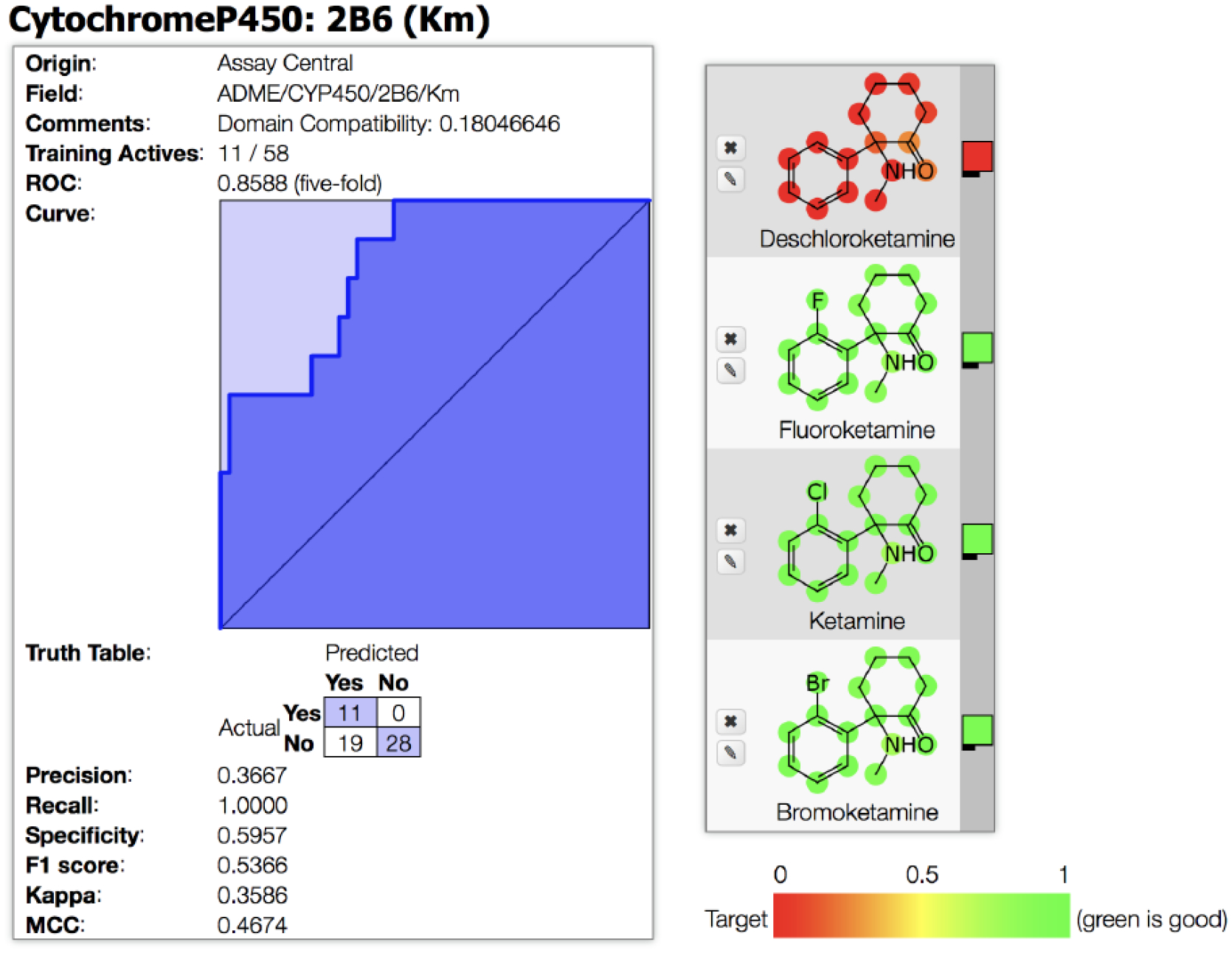

CYP2B6 Bayesian model

We curated a total of 58 unique molecules from multiple sources and experimental groups with log Km data for CYP2B6,34 and 4 additional compounds (efavirenz and 3 analogs35) were added from ChEMBL (www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/). Of note is that this dataset contained both R- and S-ketamine with calculated Km values of 74 and 44μM, respectively, obtained using human liver microsomes.20 This varies significantly from the current data with Km values of 10–15μM. These compounds were therefore removed from the model in order to reduce an activity bias for the ketamine analogs. A Bayesian model was then built with Assay Central.36–38 The model was built with a threshold of 15μM using ECFP6 descriptors, which generated 11 active compounds. Five-fold cross validation was performed. In addition, using data from ChEMBL CYP2B6 inhibitor models were built where the IC50/EC50 measurements (198 compounds, 78 actives) were calculated with a threshold of 15.22 μM and the Ki (224 compounds, 83 actives) was calculated with a threshold of 16.27 μM.39

Results

Enantioselective HPLC MS/MS methods have been developed for analysis of ketamine and metabolites, using metabolite reference standards.11, 40 The method was used successfully for recent investigation of stereoselective ketamine N-demethylation to norketamine by CYP2B6 genetic variants.30 However, for the present analysis of the metabolism of ketamine analogs, the reference standards bromo-norketamine and fluoro-norketamine were not available. Therefore, in the current investigation a formaldehyde assay was used as an alternative method to evaluate N-demethylation of ketamine analogs.

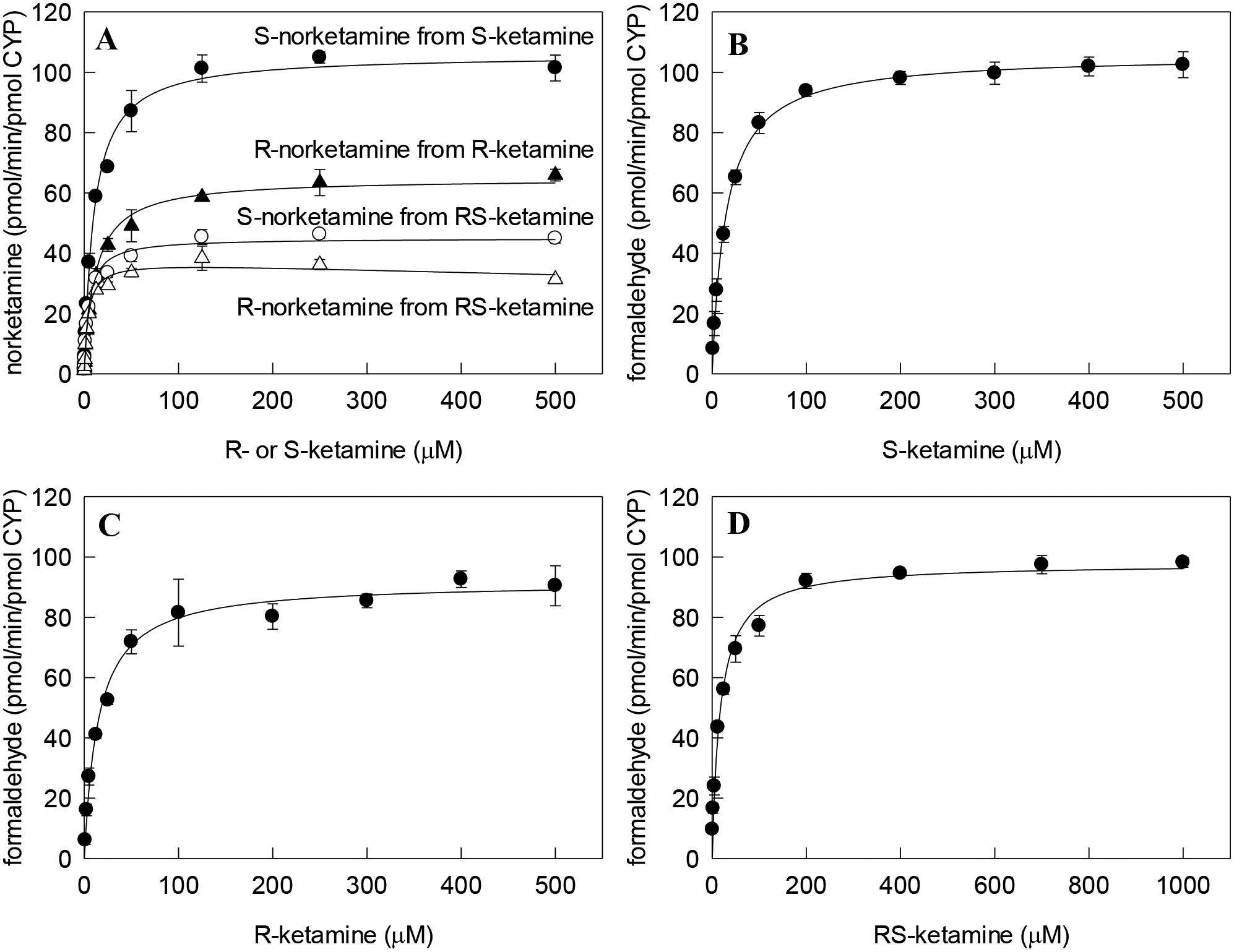

The single enantiomers, S- and R-ketamine, and racemic RS-ketamine were incubated with CYP2B6 in the presence of POR and cytochrome b5. The two products of N-demethylation, norketamine and formaldehyde, were measured by HPLC MS/MS and formaldehyde assay, respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). Apparent Km values from the formaldehyde analysis were somewhat higher than from the norketamine analysis, Vmax values were generally in good agreement, and the in vitro intrinsic clearance (Clint, Vmax / Km) values, particularly for the racemate, were in excellent agreement. Our previous studies showed that conversion of norketamine to secondary metabolites was not detectable under the experimental conditions used.30 Thus, formaldehyde formation was an acceptable surrogate for norketamine formation from RS-ketamine.

Fig 1.

Comparison of ketamine N-demethylation measured by norketamine formation using HPLC MS/MS analysis and by formaldehyde formation. (A) Norketamine formation from ketamine analyzed by HPLC MS/MS. S-norketamine from S-ketamine substrate (●), R-norketamine from R-ketamine substrate (▲), S-norketamine from racemic RS-ketamine substrate (○), R-norketamine from racemic RS-ketamine substrate (△). (B) Formaldehyde formation from S-ketamine substrate. (C) Formaldehyde formation from R-ketamine substrate. (D) Formaldehyde formation from RS-ketamine substrate. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of triplicates. Lines represent velocities predicted from nonlinear regression analysis of data using single enzyme Michaelis-Menten equation.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for ketamine demethylation measured from norketamine and formaldehyde formation

| Substrate | Product | Km (μM) |

Vmax (pmol・min−1・pmol CYP−1) |

Clint (ml・min–1・nmol P450–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-ketamine | S-norketamine | 10 ± 1 | 106 ± 1 | 10.4 |

| S-ketamine | formaldehyde | 15 ± 1 | 106 ± 1 | 7.2 |

| R-ketamine | R-norketamine | 11 ± 1 | 65 ± 1 | 5.7 |

| R-ketamine | formaldehyde | 15 ± 1 | 92 ± 2 | 6.2 |

| RS-ketamine | S-norketamine | 5 ± 1 | 45 ± 1 | 9.0 |

| RS-ketamine | R-norketamine | 4 ± 1 | 38 ± 1 | 9.2 |

| RS-ketamine | formaldehyde | 17 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 | 5.7 |

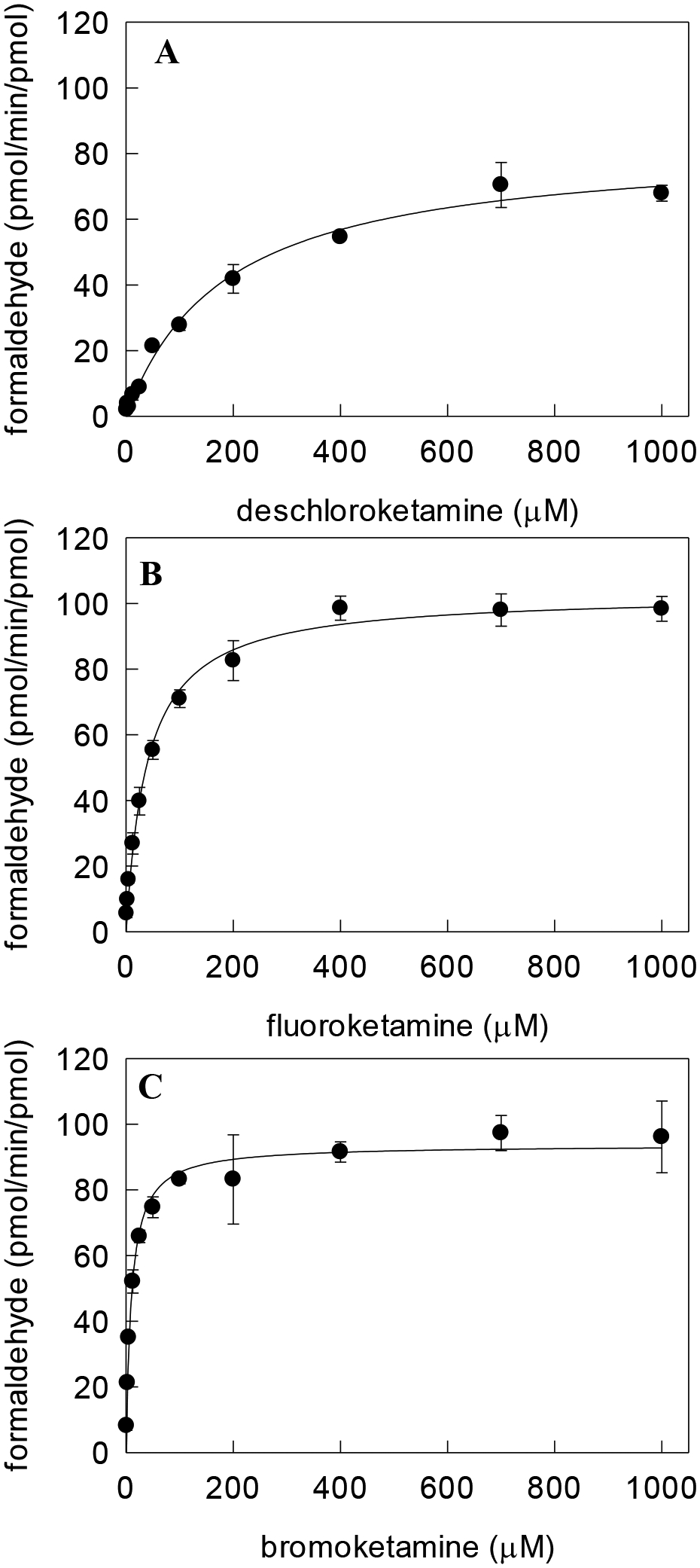

N-demethylation of ketamine analogs by CYP2B6 was evaluated by formaldehyde analysis (Figure 2), and the kinetic parameters are provided in Table 2. With substituent changes at the ortho position on the phenyl ring from hydrogen to fluorine, chlorine, and bromine, substantial (18-fold) differences in Km values were observed, from 184 μM for deschloroketamine to 10 μM for bromoketamine. In contrast, Vmax values showed relatively minor differences (range 83 to 103 pmol/min/pmol CYP).

Fig 2.

N-demethylation of (A) deschloroketamine, (B) fluoroketamine, and (C) bromoketamine measured from formaldehyde formation. Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. of triplicates. Lines represent velocities predicted from nonlinear regression analysis of data using single enzyme Michaelis-Menten equation.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for demethylation of ketamine analogs measured by formaldehyde formation

| Ketamine analog | Halogen substitution | Km (μM) |

Vmax (pmol・min−1・pmol CYP−1) |

Clint (ml・min–1・nmol P450–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS-deschloroketamine | H | 184 ± 18 | 83 ± 3 | 0.45 |

| RS-fluoroketamine | F | 40 ± 3 | 103 ± 2 | 2.6 |

| RS-ketamine | Cl | 17 ± 1 | 98 ± 1 | 5.7 |

| RS-bromoketamine | Br | 10 ± 1 | 94 ± 2 | 9.6 |

Docking

To understand the influence of halogen substitution on ketamine metabolism by CYP2B6, we carried out molecular docking simulations to study CYP2B6-ligand interactions in the active site and the structural basis of ligand binding affinity and substrate selectivity associated with halogen substitution.

For deschloroketamine, a docking pose was chosen not only based on a high score, but also based on the logical positioning of the N-methyl group of the molecule in proximity to the P450 heme, because of the substantial size of the CYP2B6 binding site. The docking poses of ketamine and all the analogs were very similar, sharing a π-stack with F297. The libdock scores had the following relationship: deschloroketamine < bromoketamine < ketamine < fluoroketamine (Figure S1).

Bayesian models

The Bayesian Km model generated with literature data using Assay Central resulted in an ROC of 0.86 and other statistical measures after 5-fold cross-validation (Figure 3) which were generally acceptable for such a small training set. The probability of activity at 15μM for ketamine and analogs was predicted based on this model to produce an output score and applicability value (Table 3). The deschloroketamine score strongly suggested inactivity, which corresponded to the experimental Km value of 184μM (Tables 2 and 3). The model was unable to accurately predict the activity of fluoroketamine, which was predicted to be active, (although the observed experimental Km, 40μM, was relatively high (Tables 2 and 3). This was similar to the lack of accuracy of the docking scores. Surprisingly, when we expanded this model to include the updated Km values for R- and S-ketamine of < 15μM, deschloroketamine was not well predicted to be active as compared to the other analogs, suggesting the importance of the halogen for predicted activity. We also scored the inhibitory potential of these ketamine analogs against Bayesian models built from publically accessible Ki and EC50 or IC50 data for CYP2B6 from ChEMBL. The Ki model had an ROC of 0.81 and the EC50 or IC50 model had an ROC of 0.84 (Figure S2). Each of the ketamine compounds scored as probable inhibitors of CYP2B6 with a probability score of approximately 0.5 (Table 3).

Figure 3:

ROC plot for the CYP2B6 Km model and predictions for ketamine and analogs in Assay Central.

Table 3.

Ketamine and analogs Assay Central Km, Ki, IC50/EC50 models with applicability scores and some molecular properties.

| Molecule | Molecular Structure | MW | AlogP | Assay Central Probability Score (Km model) | Assay Central Applicability Score (Km model) | Assay Central Probability Score (Ki model) | Assay Central Applicability Score (Ki model) | Assay Central Probability Score (IC50/EC50 model) | Assay Central Applicability Score (IC50/EC50 model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| deschloroketamine |

|

204.3 | 0.985 | −3.614 | 0.579 | 0.527 | 0.474 | 0.595 | 0.553 |

| fluoroketamine |

|

222.3 | 1.19 | 15.231 | 0.535 | 0.510 | 0.442 | 0.530 | 0.422 |

| ketamine |

|

238.7 | 1.649 | 8.554 | 0.488 | 0.564 | 0.465 | 0.595 | 0.488 |

| bromoketamine |

|

283.2 | 1.733 | 8.144 | 0.419 | 0.584 | 0.395 | 0.568 | 0.419 |

Higher probability scores relate to increased affinity. Applicability scores address overlap of fragments of a molecule compared to the training set for each model. The higher the score the more similar to compounds in the training set.

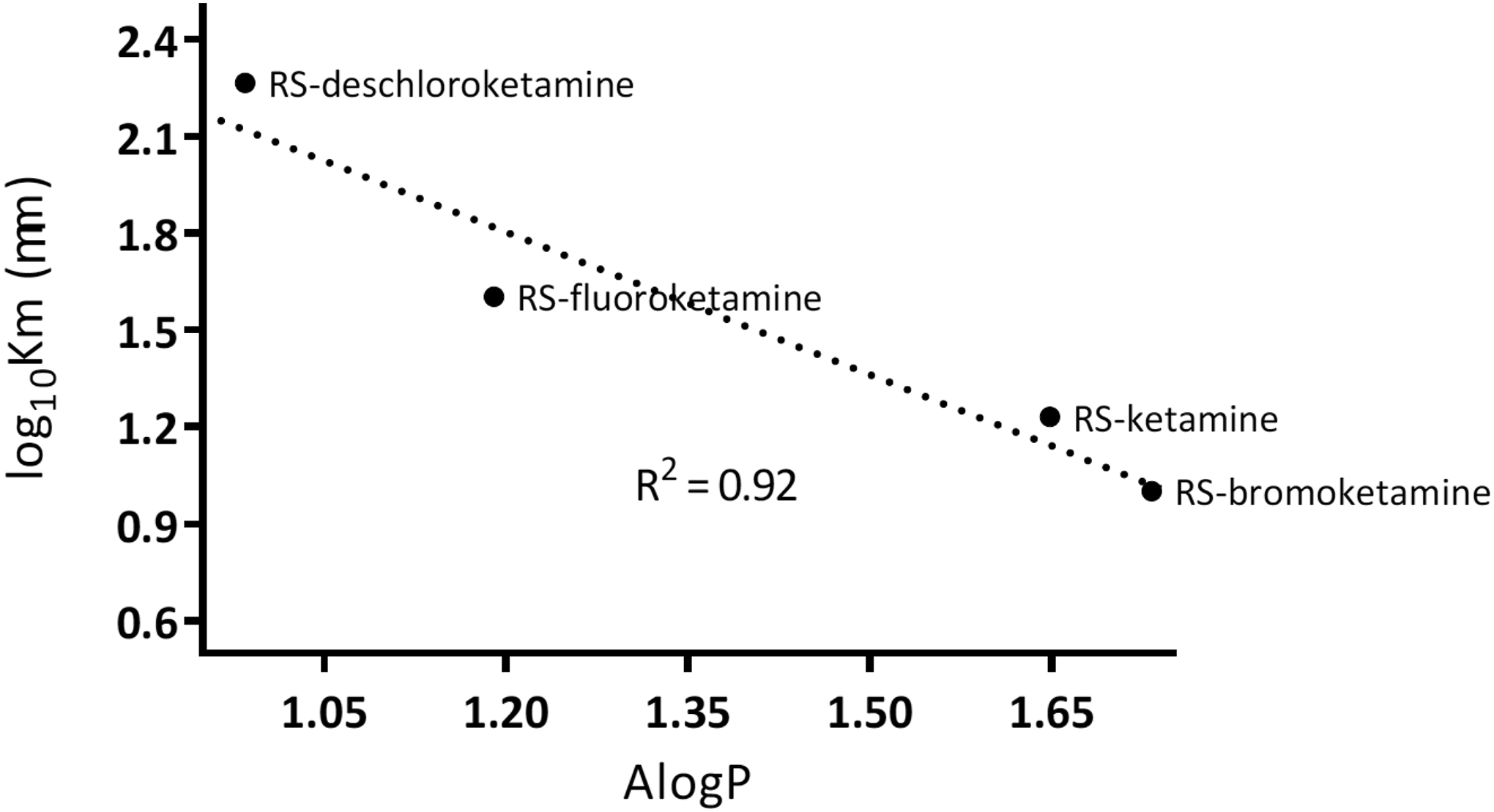

Assessing the binding pocket of CYP2B6 suggests a hydrophobic component to substrate docking. There are several hydrophobic residues, including I101, I114, L363, V367, and V477 in the substrate binding pocket. Comparison of AlogP (calculated in Discovery Studio) and log Km of ketamine and ketamine analogs showed a strong linear correlation (R2=0.92, Figure 4). This calculated chemical property successfully predicted the experimental log Km, with an increase in hydrophobicity correlating with an increase in affinity.

Figure 4.

Correlation of log Km and AlogP for N-demethylation of halogenated and non-halogenated ketamine analogs

Discussion

The main finding of this investigation was that the halogen substituent at the ortho position on the phenyl ring of racemic ketamine analogs markedly influenced the rate of N-demethylation. Metabolism, based on Clint, was on the order Br > Cl > F > H. Vmax values were relatively unchanged, while Km was on the order Br < Cl < F < H. Thus, apparent substrate binding affinity was the major consequence of halogen substitution on ketamine analogs, and the major determinant of N-demethylation.

Incorporation of halogen atoms into a drug molecule can have profound pharmacological implications. Halogen substitution has been investigated extensively in drug research for optimization of drug adsorption, distribution, recognition and selectivity. It is estimated that approximately 20% of approved drugs are halogenated, as are a similar portion in other stages of discovery and development.27 Halogen effects on interactions of small molecules with proteins can be mediated through classical halogen properties of reactivity, lipophilicity, and electronegativity, and the newly characterized halogen bond.41 Halogen bonding is analogous to hydrogen bonding, driving short, stabilizing electrostatic interactions with electron-rich atoms, with the halogen serving as a halogen bond donor to an electron rich acceptor – typically the carbonyl oxygen of the peptide bond in proteins.41 The strength of halogen bonding correlates with polarizability of the halogen atoms and changes in the order of F<Cl<Br<I.26 Similarly, the hydrophobicity of halogenated substrates is also affected by polarizability, and lowest for fluorine and highest for iodine.

Major determinants of substrate binding affinity to P450s depend on the specific isoform. In general, determinants for binding include hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding features, while electronic factors determine reaction rates.42, 43 For CYP2B6 more specifically, halogen-π interactions between substrates and phenylalanine side chains in the hydrophobic active site are considered to drive substrate selectivity and affinity.28 There are however few systematic evaluations, of the effects on metabolism or affinity more generally, of halogen substitution on a particular substrate scaffold.26

Based on the results of this investigation, the major determinant of halogen substituent effects on ketamine analogs binding affinity to CYP2B6 is likely hydrophobicity. This conclusion is based on the excellent correlation between the calculated property AlogP and log Km (R2=0.92, Figure 4). Thus hydrophobicity changes due to halogen substitution may be the simplest design criteria to use when considering similar compounds and the affinity for CYP2B6. There is also species evidence that proposes a hydrophobic element to CYP2B substrate selection, with variation in the hydrophobic active sites found between orthologs.28 An unexpected truism is that halogens are generally hydrophobic atoms, with Br having the same hydrophobic effect as a methyl group.44, 45 This has been shown experimentally, where halogen substitutions had a drastic effect on the logP(octanol-water) of compounds and the larger the halogen the more dramatic the effect.46 It has also been previously suggested that hydrophobic interactions are a major contribution in the interface between human protein kinase CK2α and a series of halogen-substituted benzotriazoles, and was directly linked with the hydrophobicity of the halogen substituent.47 Inhibition increased as the electronegativity of the halide substituent decreased (IC50: F<Cl<Br). Molecular modeling suggested that the substituted halogen forms direct interactions with hydrophobic residues within the binding pocket in a similar fashion to those found in the crystal structure of human pCDK2. These interactions are thought to stabilize the complex by protecting the hydrophobic halogen atoms from solvent accessibility.

The present results can be compared with some previous observations. Many other CYP2B6 substrates are also halogenated, including the drugs bupropion, efavirenz, ticlopidine, and amlodipine, and various environmental chemicals.48 There has also been evidence that suggests halogen-π interactions may also play a role in CYP2B6-substrate interactions, with the crystal structure of CYP2B6 and its halogenated monoterpene bornyl bromide demonstrating bromine-π bonding with the aromatic side chain of phenylalanine 108.28 Similar computational modeling of myrtenyl bromide suggested bromine-π bonding to the aromatic side chain of phenylalanine 297.28 These results were interpreted to suggest that halogen-π interactions may be unique to CYP2B enzymes, which possesses a sufficiently malleable active site to enable halogen interactions with multiple phenylalanine residues.28 A kinetic investigation probed the influence of halogenation of CYP2B6-catalyzed metabolism.49 Using a small series of 4-trifluoromethyl-7-ethoxycoumarins to probe metabolism (O-dealkylation) by CYP2B6, it was found that 2-ethoxy chlorination, and more so bromination, moderately decreased the Km, while kcat was markedly reduced (by more than 90%) by either bromination or chlorination, resulting in net reduction (by 85–90%) in catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km).49 These turnover results are in contrast to the present results with ketamine analogs. Nevertheless, together these combined observations may implicate the role of halogen bonding in the selectivity of ligand binding to CYP2B enzymes.

There is little other catalytic, and no clinical information, about metabolism of halogenated ketamine analogs to our knowledge. It has been suggested, albeit without any accompanying data, that deschloroketamine, a black market designer drug, be more potent and longer lasting than ketamine.50 The results of the present study do suggest that slower metabolism of deschloroketamine might mean diminished systemic clearance. This presents potential opportunities for deriving new analogs in the future with improved pharmacokinetic properties. For example, analogs with reduced metabolism may have improved oral availability and/or greater duration of effect. Avid ketamine metabolism and low bioavailability may underlie the lack of analgesia of oral ketamine.51 Conversely, since ketamine antidepressant effects have been attributed to one or more active metabolites, such as norketamine and hydroxynorketamine,16, 17, 25 greater metabolite formation may enhance antidepressant effects. It is not apparent how chloro- (or more generally halogen) substitution alone influences interactions between ketamine and its drug targets.3

There are recognized limitations with the various computational approaches. The Libdock program used for docking only considers halogen H-bonding/π-stacking and did not include a halogen bond scoring function. Halogen bonding is very complex with many caveats, including directionality. The anisotropic electron distribution of halogens coupled with an aromatic ring adds an additional level of complexity, partially because it is impacted by the other electron withdrawing groups found on the ring. The binding pocket of CYP2B6 is large relative to a small molecule like ketamine making the docking very challenging.

CYP2B6 metabolizes 3–10% of therapeutic drugs, but is still less well characterized than many other CYP isoforms.34, 52–56 Monoterpenes have also been suggested as ideal active site probes for CYP2B6.28, 29, 57 The present results suggest that ketamine analogs may also be very useful probes, particularly for representatives of drugs as well as environmental contaminants such as pesticides and nerve agents and mitigating the toxicity of such molecules.58 These ketamine analogs suggest unmet needs and opportunities to better understand substrate-CYP2B6 interactions and enable reliable future computational predictions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Alex Clark is gratefully acknowledged for his assistance with Assay Central. Biovia are kindly acknowledged for providing Discovery Studio to SE

Funding:

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DA14211, R43GM122196 and R44GM122196, and by the Washington University in St. Louis Department of Anesthesiology Russel B and Mary D Shelden fund

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: SE is an owner and SE, TRL and KMZ are employees of Collaborations Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Peltoniemi MA; Hagelberg NM; Olkkola KT; Saari TI, Ketamine: A review of clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in anesthesia and pain therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 2016, 55, 1059–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domino EF, Taming the ketamine tiger. 1965. Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens CL; Thuillier A; Taylor KG; Daniher FA; Dickerson JP; Hansom HT; Nielsen NA; Tikotkar NA; Weier RM, Amino ketone rearrangements. VII. Synthesis of 2-methylamino-2-substituted phenylcyclohexanones. J. Org. Chem 1966, 31, 2601–2607. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens CL, Aminoketones and methods for their production. USPTO 1966, Patent 3,254,124.

- 5.Maddox VH; Godefroi EF; Parcell RF, The synthesis of phencyclidine and other 1-arylcyclohexylamines. J Med Chem 1965, 8, 230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zorumski CF; Izumi Y; Mennerick S, Ketamine: NMDA receptors and beyond. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 11158–11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobo WV; Vande Voort JL; Croarkin PE; Leung JG; Tye SJ; Frye MA, Ketamine for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar major depression: Critical review and implications for clinical practice. Depress Anxiety 2016, 33, 698–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoevers RA; Chaves TV; Balukova SM; Rot MA; Kortekaas R, Oral ketamine for the treatment of pain and treatment-resistant depression. Br J Psychiatry 2016, 208, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harraz MM; Snyder SH, Antidepressant actions of ketamine mediated by the mechanistic target of rapamycin, nitric oxide, and rheb. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade C, Ketamine for depression, 5: Potential pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions. J Clin Psychiatry 2017, 78, e858–e861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao LK; Flaker AM; Friedel CC; Kharasch ED, Role of cytochrome P4502B6 polymorphisms in ketamine metabolism and clearance. Anesthesiology 2016, 125, 1103–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noppers I; Olofsen E; Niesters M; Aarts L; Mooren R; Dahan A; Kharasch E; Sarton E, Effect of rifampicin on S-ketamine and S-norketamine plasma concentrations in healthy volunteers after intravenous S-ketamine administration. Anesthesiology 2011, 114, 1435–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peltoniemi MA; Saari TI; Hagelberg NM; Reponen P; Turpeinen M; Laine K; Neuvonen PJ; Olkkola KT, Exposure to oral S-ketamine is unaffected by itraconazole but greatly increased by ticlopidine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011, 90, 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peltoniemi MA; Saari TI; Hagelberg NM; Laine K; Kurkinen KJ; Neuvonen PJ; Olkkola KT, Rifampicin has a profound effect on the pharmacokinetics of oral S-ketamine and less on intravenous S-ketamine. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012, 111, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung LY; Baillie TA, Comparative pharmacology in the rat of ketamine and its two principal metabolites, norketamine and (Z)-6-hydroxynorketamine. J. Med. Chem 1986, 29, 2396–2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul RK; Singh NS; Khadeer M; Moaddel R; Sanghvi M; Green CE; O’Loughlin K; Torjman MC; Bernier M; Wainer IW, (R,S)-Ketamine metabolites (R,S)-norketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine increase the mammalian target of rapamycin function. Anesthesiology 2014, 121, 149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanos P; Moaddel R; Morris PJ; Georgiou P; Fischell J; Elmer GI; Alkondon M; Yuan P; Pribut HJ; Singh NS; Dossou KS; Fang Y; Huang XP; Mayo CL; Wainer IW; Albuquerque EX; Thompson SM; Thomas CJ; Zarate CA Jr.; Gould TD, NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016, 533, 481–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris PJ; Moaddel R; Zanos P; Moore CE; Gould T; Zarate CA Jr.; Thomas CJ, Synthesis and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity of ketamine metabolites. Org Lett 2017, 19, 4572–4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanagihara Y; Kariya S; Ohtani M; Uchino K; Aoyama T; Yamamura Y; Iga T, Involvement of CYP2B6 in N-demethylation of ketamine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos 2001, 29, 887–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hijazi Y; Boulieu R, Contribution of CYP3A4, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9 isoforms to N-demethylation of ketamine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos 2002, 30, 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portmann S; Kwan HY; Theurillat R; Schmitz A; Mevissen M; Thormann W, Enantioselective capillary electrophoresis for identification and characterization of human cytochrome P450 enzymes which metabolize ketamine and norketamine in vitro. J Chromatogr A 2010, 1217, 7942–7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desta Z; Moaddel R; Ogburn ET; Xu C; Ramamoorthy A; Venkata SL; Sanghvi M; Goldberg ME; Torjman MC; Wainer IW, Stereoselective and regiospecific hydroxylation of ketamine and norketamine. Xenobiotica 2012, 42, 1076–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y; Coller JK; Hutchinson MR; Klein K; Zanger UM; Stanley NJ; Abell AD; Somogyi AA, The CYP2B6*6 allele significantly alters the N-demethylation of ketamine enantiomers in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos 2013, 41, 1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palacharla RC; Nirogi R; Uthukam V; Manoharan A; Ponnamaneni RK; Kalaikadhiban I, Quantitative in vitro phenotyping and prediction of drug interaction potential of CYP2B6 substrates as victims. Xenobiotica 2018, 48, 663–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh NS; Zarate CA Jr.; Moaddel R; Bernier M; Wainer IW, What is hydroxynorketamine and what can it bring to neurotherapeutics? Expert Rev Neurother 2014, 14, 1239–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilcken R; Zimmermann MO; Lange A; Joerger AC; Boeckler FM, Principles and applications of halogen bonding in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J Med Chem 2013, 56, 1363–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Z; Yang Z; Liu Y; Lu Y; Chen K; Zhu W, Halogen bond: its role beyond drug-target binding affinity for drug discovery and development. J Chem Inf Model 2014, 54, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah MB; Liu J; Zhang Q; Stout CD; Halpert JR, Halogen-π interactions in the cytochrome P450 active site: Structural insights into human CYP2B6 substrate selectivity. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 1204–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah MB; Wilderman PR; Liu J; Jang HH; Zhang Q; Stout CD; Halpert JR, Structural and biophysical characterization of human cytochromes P450 2B6 and 2A6 bound to volatile hydrocarbons: analysis and comparison. Mol Pharmacol 2015, 87, 649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang PF; Neiner A; Kharasch ED, Stereoselective ketamine metabolism by genetic variants of cytochrome P450 CYP2B6 and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakajima M; Mizusawa K, Method for determination of formaldehyde. 1984, US Patent 4438206.

- 32.EPA, U., Method 8315A (SW-846): Determination of carbonyl compounds by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Revision 1. 1996, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gay SC; Shah MB; Talakad JC; Maekawa K; Roberts AG; Wilderman PR; Sun L; Yang JY; Huelga SC; Hong WX; Zhang Q; Stout CD; Halpert JR, Crystal structure of a cytochrome P450 2B6 genetic variant in complex with the inhibitor 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole at 2.0-Å resolution. Mol Pharmacol 2010, 77, 529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekins S; Iyer M; Krasowski MD; Kharasch ED, Molecular characterization of CYP2B6 substrates. Curr Drug Metab 2008, 9, 363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox PM; Bumpus NN, Structure-activity studies reveal the oxazinone ring Is a determinant of cytochrome P450 2B6 activity toward efavirenz. ACS Med Chem Lett 2014, 5, 1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lane T; Russo DP; Zorn KM; Clark AM; Korotcov A; Tkachenko V; Reynolds RC; Perryman AL; Freundlich JS; Ekins S, Comparing and validating machine learning models for mycobacterium tuberculosis drug discovery. Mol Pharm 2018, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo DP; Zorn KM; Clark AM; Zhu H; Ekins S, Comparing multiple machine learning algorithms and metrics for estrogen receptor binding prediction. Mol Pharm 2018, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandoval PJ; Zorn KM; Clark AM; Ekins S; Wright SH, Assessment of substrate-dependent ligand interactions at the organic cation transporter OCT2 using six model substrates. Mol Pharmacol 2018, 94, 1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark AM; Ekins S, Open source Bayesian models. 2. Mining a “big dataset” to create and validate models with ChEMBL. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, 1246–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moaddel R; Venkata SL; Tanga MJ; Bupp JE; Green CE; Iyer L; Furimsky A; Goldberg ME; Torjman MC; Wainer IW, A parallel chiral-achiral liquid chromatographic method for the determination of the stereoisomers of ketamine and ketamine metabolites in the plasma and urine of patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Talanta 2010, 82, 1892–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho PS, Halogen bonding in medicinal chemistry: from observation to prediction. Future Med Chem 2017, 9, 637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis DF; Eddershaw PJ; Dickins M; Tarbit MH; Goldfarb PS, Structural determinants of cytochrome P450 substrate specificity, binding affinity and catalytic rate. Chem Biol Interact 1998, 115, 175–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis DF; Lake BG; Dickins M; Eddershaw PJ; Tarbit MH; Goldfarb PS, Molecular modelling of CYP2B6, the human CYP2B isoform, by homology with the substrate-bound CYP102 crystal structure: evaluation of CYP2B6 substrate characteristics, the cytochrome b5 binding site and comparisons with CYP2B1 and CYP2B4. Xenobiotica 1999, 29, 361–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scholfield MR; Zanden CM; Carter M; Ho PS, Halogen bonding (X-bonding): a biological perspective. Protein Sci 2013, 22, 139–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YH; Zou JW; Lu YX; Yu QS, Single-electron halogen bond: Ab initio study. Int J Quantum Chem 2007, 107, 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghose AK; Viswanadhan VN; W. JJ, Prediction of hydrophobic (lipophilic) properties of small organic molecules using fragmental methods: An analysis of ALOGP and CLOGP methods. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 3762–3772. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasik R; Lebska M; Felczak K; Poznanski J; Shugar D, Relative role of halogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions in inhibition of human protein kinase CK2alpha by tetrabromobenzotriazole and some C5-substituted analogues. J Phys Chem B 2010, 114, 10601–10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodgson E; Rose RL, The importance of cytochrome P450 2B6 in the human metabolism of environmental chemicals. Pharmacol Ther 2007, 113, 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J; Shah MB; Zhang Q; Stout CD; Halpert JR; Wilderman PR, Coumarin derivatives as substrate probes of mammalian cytochromes P450 2B4 and 2B6: Assessing the importance of 7-alkoxy chain length, halogen substitution, and non-active site mutations. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1997–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frison G; Zamengo L; Zancanaro F; Tisato F; Traldi P, Characterization of the designer drug deschloroketamine (2-methylamino-2-phenylcyclohexanone) by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography/high-resolution mass spectrometry, multistage mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2016, 30, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fallon MT; Wilcock A; Kelly CA; Paul J; Lewsley LA; Norrie J; Laird BJA, Oral ketamine vs placebo in patients With cancer-related neuropathic pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018, 4, 870–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H; Tompkins LM, CYP2B6: new insights into a historically overlooked cytochrome P450 isozyme. Curr Drug Metab 2008, 9, 598–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mo SL; Liu YH; Duan W; Wei MQ; Kanwar JR; Zhou SF, Substrate specificity, regulation, and polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2B6. Curr Drug Metab 2009, 10, 730–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turpeinen M; Zanger UM, Cytochrome P450 2B6: function, genetics, and clinical relevance. Drug Metabol Drug Interact 2012, 27, 185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zanger UM; Klein K, Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6): advances on polymorphisms, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Front Genet 2013, 4, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedrich WD; Hassan HE; Wang H, Insights into CYP2B6-mediated drug-drug interactions. Acta Pharm Sin B 2016, 6, 413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilderman PR; Shah MB; Jang HH; Stout CD; Halpert JR, Structural and thermodynamic basis of (+)-α-pinene binding to human cytochrome P450 2B6. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135, 10433–10440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jan YH; Richardson JR; Baker AA; Mishin V; Heck DE; Laskin DL; Laskin JD, Novel approaches to mitigating parathion toxicity: targeting cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism with menadione. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2016, 1378, 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.