DEATH CREATES FORM

Michelangelo once described his art like this: “For sculpture, I mean that made by removing; that by adding is similar to painting.”1 Although animals are not fashioned from solid blocks by the removal of unneeded parts, such a process does contribute to the generation of form and function in the embryo. Of course, development is an immensely complex process involving cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and adhesion as well as cell–cell interactions and cell death. But here, we are concerned primarily with the latter.

The goal here is not to catalog all the ways that cell death contributes to animal development but, instead, to explore how specific cues can activate the core cell death machinery, to program cell death in development. That is, we examine how a cell can be specified for death.

As noted in Green (2022a), the term “programmed cell death” refers to cell death that occurs at a genetically prescribed point during development (and has since come to mean apoptosis in many investigators’ lexicons) and removes extra cells that can be present for a variety of reasons. For example, they might have inductive or scaffolding functions in developing tissues or be involved in selection steps. We discuss examples of each. Alternatively, animals can undergo metamorphosis during their life cycles, and cell death is involved in the repatterning that occurs. The specification of cells for death by developmental cues is best understood in invertebrate systems, and we begin with some examples from these.

CELL DEATH IN NEMATODE DEVELOPMENT

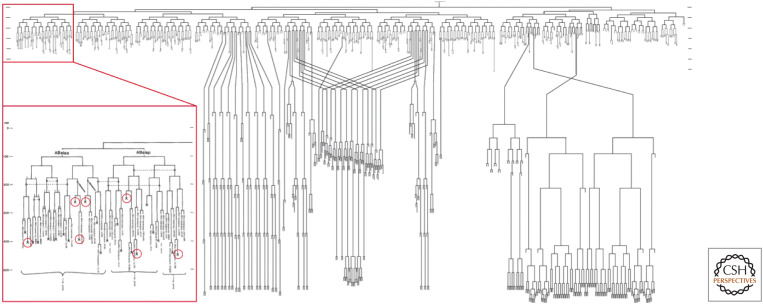

During the development of nematodes, cells follow a strict program in which every cell produced, beginning with the fertilized egg, has a predetermined fate. There are 1090 cells produced, and 113 of these die during embryogenesis. After this, another 18 cells die on the way to adulthood. Some of the cell deaths that occur during embryogenesis are indicated in the inset in Figure 1. In the adult hermaphrodite, about half of the developing oocytes die, but there are no other cell deaths. In males (the other sex), no cell death occurs in adults.

Figure 1.

Developmental plan of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. During development, each cell that arises by cell division undergoes a set process of further division, differentiation, or cell death. (Inset) Part of the developmental plan, with seven cell deaths circled. (Reprinted from Sulston et al. 1983, ©1983 with permission from Elsevier.)

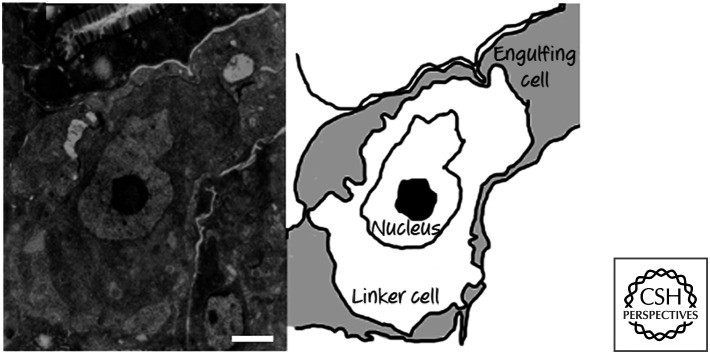

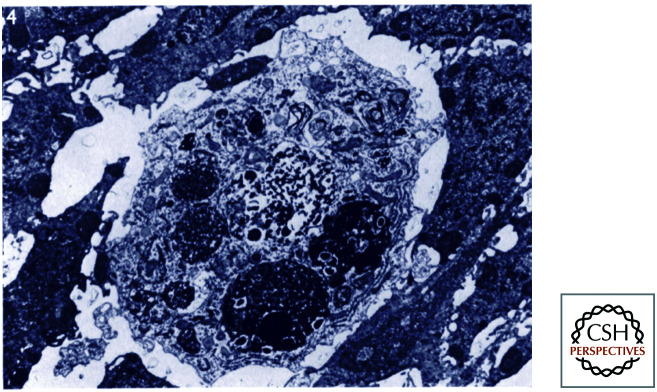

All of the cell deaths that occur are by apoptosis, except for one—the death of the so-called linker cell. This cell is involved in the development of the male gonad and, based on morphology, appears to die by necrosis (Fig. 2). All of the other cell deaths depend on CED4 (the APAF1 homolog) and CED3 (the caspase).

Figure 2.

Necrotic-type linker cell death. In the micrograph (left), note that the dying linker cell has no features of apoptosis. (Reprinted from Abraham et al. 2007, ©2007 with permission from Elsevier.)

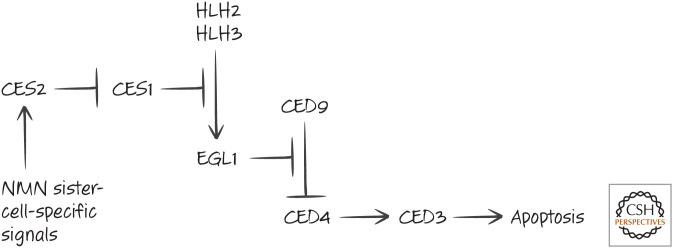

Most of this cell death is in the neuronal lineages. The signals controlling the core apoptotic pathway are known for two of these: the neurosecretory motor neuron (NMN) sister cells and the hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs). The latter only die in developing male worms.

In NMN sister cells and the HSNs destined to die, the helix–loop–helix transcription factors HLH2 and HLH3 induce EGL1, the nematode BH3-only protein. Another factor, CES1, inhibits expression of EGL1 in the NMN cells that do not die. Yet another protein, CES2, is expressed in the NMN sister cells specified for death, and CES2 transcriptionally represses CES1. As a result, the NMN sister cells die (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Neurosecretory motor neuron (NMN) sister cell death.

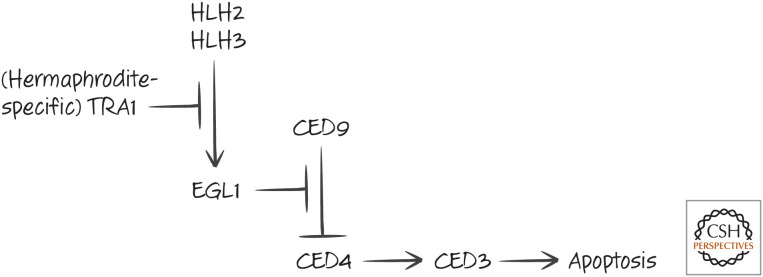

In males, the pathway controlling HSN death is similar. Again, HLH2 and HLH3 induce expression of EGL1, leading to cell death. In hermaphrodites, expression of EGL1 in the HSN cells is blocked by expression of another factor, TRA1, that is not expressed in males (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Hermaphrodite-specific neuron (HSN) cell death in males.

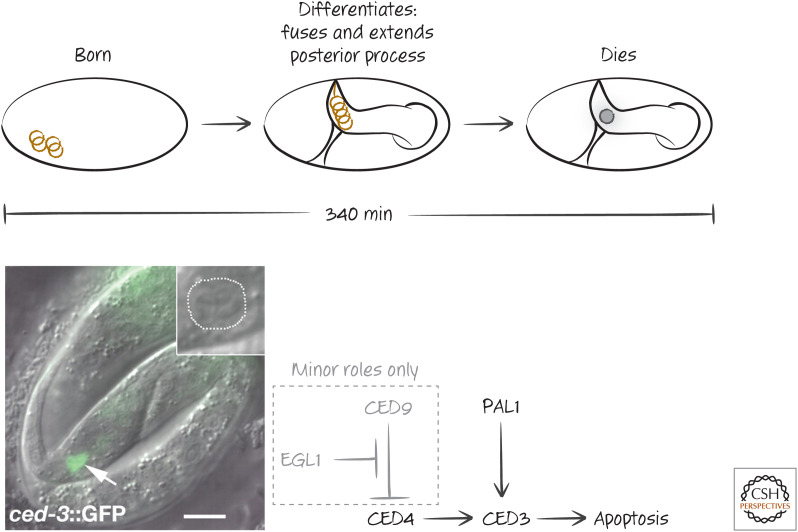

Additional pathways exist in other cell lineages. These probably also act through regulators of the core apoptosis pathway, but how this occurs is less clear. In a cell called the tail-spike cell, the timing of cell death appears to be controlled by transcriptional regulation of the caspase CED3 (Fig. 5). Although CED4 is required for the developmental death of this cell, EGL1 and CED9 (which are upstream) appear to have only minor regulatory effects. The control mechanism is a transcription factor, the homeobox protein PAL-1, that regulates CED3 and therefore apoptosis in this cell. EGL1 and CED9 therefore influence death but, in this case, are not targets of the specification.

Figure 5.

Cell death in the tail-spike cell. (Top) Timing of the appearance (“born”), differentiation, and death of the tail-spike cell during embryogenesis. (Lower left) Image shows expression of CED3 (arrow) in the tail-spike cell in an embryo in which the ced3 gene is replaced with the gene for green fluorescent protein (and is therefore under the same regulation as ced3). (Inset) Death of the tail-spike cell in a wild-type embryo at the same stage. (Lower right) Schematic of the genetic pathway. Death in this cell is controlled mainly by the transcription factor PAL-1, which controls the expression of CED3, with little contribution from CED9 or EGL1. (Reprinted from Maurer et al. 2007, ©2007 with permission from The Company of Biologists.)

The death of the tail-spike cell illustrates a concept that is useful for understanding the timing of cell death in development. If one or more components of the cell death pathway are limiting in a cell, factors that influence the expression and/or functions of these components can be crucial for specification of the cell for death. Although only one cell in Caenorhabditis elegans appears to be specified by the regulation of caspase availability, this general mechanism for the developmental regulation of cell death is probably involved in developmental cell death in other organisms.

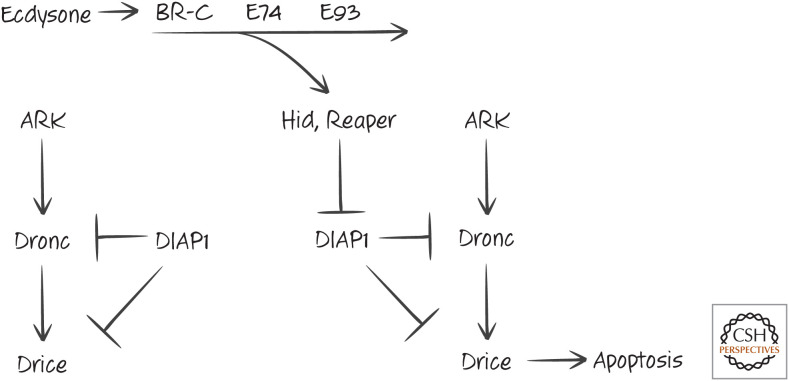

CELL DEATH DURING METAMORPHOSIS IN DROSOPHILA

In insects, there is a dramatic change in morphology when the larva pupates and undergoes metamorphosis to form an adult. In the fruitfly Drosophila, this is triggered by two waves of the steroid hormone ecdysone, whose receptor is a ligand-dependent transcription factor. The second wave of ecdysone induces the expression of the transcription factors BR-C, E74, and E93. These up-regulate the expression of several genes encoding proteins involved in cell death, including ARK, Dronc, and Drice (the fly APAF1 homolog, caspase-9 homolog, and executioner caspase, respectively). These are probably not sufficient to cause cell death in metamorphosis because the caspases are inhibited by DIAP (see Green 2022b). However, the transcription factors also induce the expression of two DIAP inhibitors, Reaper and Hid, and as a consequence, apoptosis is engaged (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Activation of the apoptosis pathway by the hormone ecdysone. By inhibiting DIAP1, the proteins Hid and Reaper promote the cell death pathway leading to activation of the executioner caspase Drice.

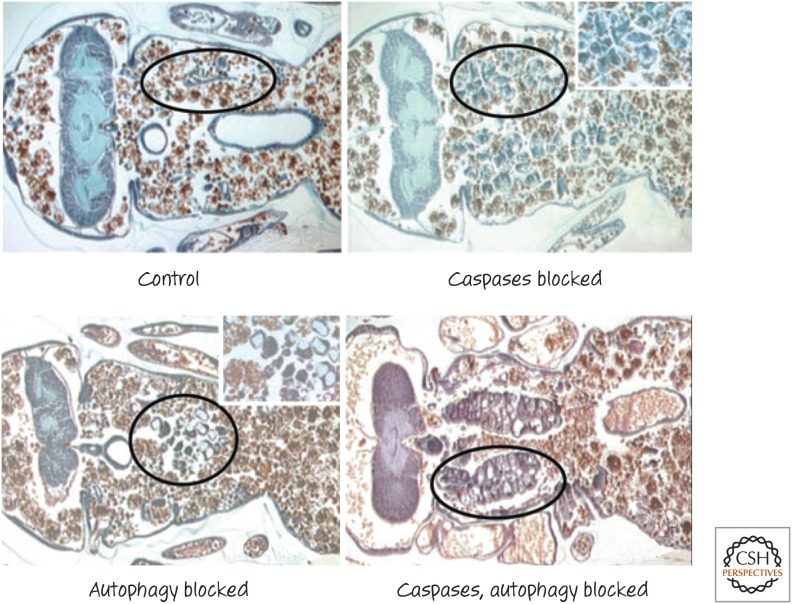

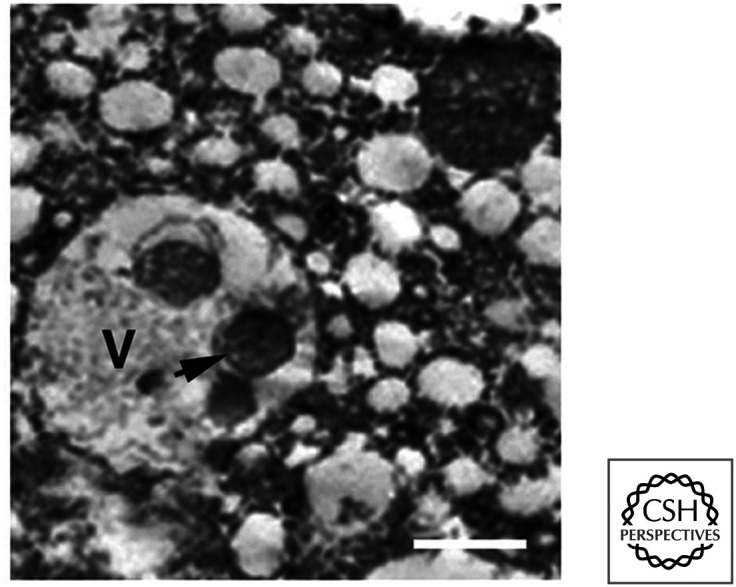

Cell death by apoptosis proceeds in the anterior muscles, larval midgut, and larval salivary glands. Apoptosis is not responsible for all (or even most) of these cell deaths. Much of the cell death that occurs during insect metamorphosis displays characteristics of the second form of cell death, autophagic cell death (see Green 2022c). Figure 7 shows autophagic cell death in the metamorphosing salivary gland.

Figure 7.

Type II death in the Drosophila salivary gland. Autophagosomes in dying cells (arrow) are abundant. V, vacuole-containing autophagosomes. (Reprinted from Lee and Baehrecke 2001, ©2001 with permission from The Company of Biologists.)

It turns out that BR-C, E74, and E93 also induce the expression of several proteins in the autophagy pathway, including ATG5 and ATG7. As discussed in Green (2022c), autophagic (type II) cell death is accompanied by autophagy but is often not dependent on this process. In this case, however, the autophagy pathway is required for the cell death that occurs, and flies with defects in autophagy display fewer cell deaths in the salivary glands during metamorphosis (Fig. 8). We do not know precisely how the autophagy pathway kills these cells, but several tissues show this effect.

Figure 8.

Cell death in the metamorphosing salivary gland of Drosophila. Inhibition of either caspases or autophagy in the animal promotes cell survival (circled areas, magnified in insets); inhibition of both produces additive effects. (Reprinted from Neufeld and Baehrecke 2008, ©Landes Bioscience.)

In addition to expression of proteins that promote death by apoptosis and autophagy, ecdysone triggers expression of Croquemort, the Drosophila CD36 homolog involved in phagocytosis and clearance of dying cells (see Green 2022d). Presumably, Croquemort is expressed in cells that do not die, so that they can participate in corpse removal during metamorphosis. There is another possibility, however; it might be that autophagy and phagocytosis in the dying cells cooperate in their death. Flies with defects in phagocytosis accumulate living cells in the metamorphosing salivary gland, and intriguingly the CED1 homolog Draper (involved in engulfment of dying cells) is required for autophagic cell death in this tissue.

CELL DEATH IN VERTEBRATE DEVELOPMENT

Cell death occurs in many cell types throughout vertebrate development, and, in the majority of cases, this is by apoptosis. In invertebrates, cell death has roles in formation of structures, removal of structures, and control of cell number. In vertebrates, it can also have fundamental roles in selecting cells for emergent functions of a cell population (discussed in the next section).

A classic example of cell death in the formation of a structure is the generation of digits in the vertebrate limb. During development, a limb paddle (or autopod) forms in which tissue fills the areas between the skeletal elements. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) family, trigger an apoptotic pathway in the interdigital webs, but how this specifies cells for death is not known. Figure 9 shows examples from chick and duck development in which the extent of apoptosis creates characteristically different outcomes.

Figure 9.

Cell death in developing chick and duck autopods. Dying cells in the autopods of both birds stain with red dye at the web tips. An artifact creates the more general staining in the duck interdigital webs. (Left, Reproduced with permission from Zuarte-Luís and Hurlé 2002; right, reprinted from Gañan et al. 1998, ©1998 with permission from Elsevier.)

Although the precise mechanisms have not been delineated, this interdigital cell death is almost certainly mediated by the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Mice lacking the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family effectors BAX and BAK usually die as embryos, but rare mice that survive retain persistently webbed feet (Fig. 10). Remarkably, this is also seen in mice that lack two of the BH3-only proteins, BIM and BMF. As discussed in Green (2022e), there are several BH3-only proteins, but, in this case, it appears that the developmental cell death is dependent only on two of them, which function redundantly. Mice lacking APAF1 or caspase-9 show a delay in digit formation during embryogenesis, but the cells nevertheless die by caspase-independent cell death (see Green 2022c,f).

Figure 10.

Webbed feet in mice lacking BAX or BAK, and mice lacking BIM or BMF, compared with mice expressing either (or both) of the genes. (Left two panels, Reprinted from Lindsten et al. 2000, ©2000 with permission from Elsevier; right two panels, reprinted from Hubner et al. 2010, ©2010 with permission from American Society for Microbiology.)

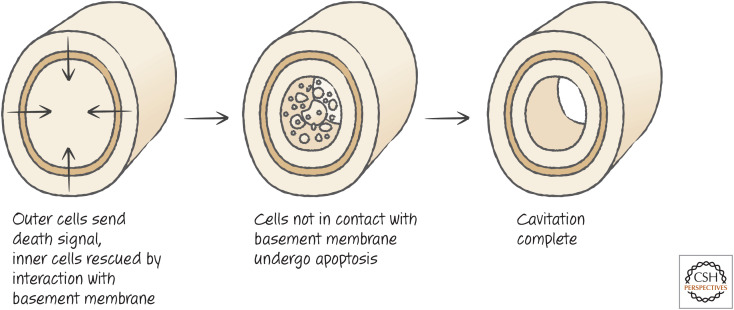

Another example of cell death creating form is cavitation, the process by which some areas hollow out during development. Examples include the formation of the pro-amniotic cavity just after implantation in mammals and the hollowing of ducts in the mammalian breast. An unknown pro-death signal is generated, but cells that are in contact with the basement membrane receive survival signals that block the death. Only the cells in the center undergo apoptosis (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

A basic plan depicting the regulatory signaling events leading to hollowing/cavitation. (Adapted from Coucouvanis and Martin 1995, ©1995 with permission from Elsevier.)

In the case of the mammalian breast, the cell death signal appears to be provided by the BH3-only proteins BIM and BMF. Anti-apoptotic effects of MCL-1 can prevent the death of cells in contact with the basement membrane.

In the acini (the milk-producing structures) of the breast, cells that move away from the basement membrane and its extracellular matrix can undergo anoikis (see Green 2022e) because they no longer receive protective survival signals. The concept is a useful one and probably applies to many other developmental events. The survival signals provided by growth factors and the extracellular matrix help to define the boundaries to which a tissue can extend.

Other interesting examples of developmental cell death in vertebrates are the loss of the tail and restructuring of the intestine during amphibian metamorphosis (Fig. 12). Here, the signal for metamorphosis and cell death is thyroid hormone. This triggers a gene-expression program in which several caspase genes are induced, and there are changes in the expression of BCL-2 family proteins as well as a variety of tissue proteases. How cells are specified for death is not well understood, nor is the initiation of apoptosis. It is likely that the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is important because removing the amphibian caspase-9 homolog severely perturbs metamorphosis.

Figure 12.

Frog metamorphosis and cell death. An apoptotic cell in the tail of a metamorphosing tadpole. (Reprinted from Kerr et al. 1974, ©1974 with permission from The Company of Biologists.)

Not all developmental cell death in mammals is apoptotic. When the embryo implants, cells of the uterine epithelium must die for implantation to occur. However, no caspase-3 cleavage (indicative of apoptosis) occurs in these cells. Instead, it appears that embryonic cells (trophectoderm) engulf the epithelial cells (and it is possible that this is entosis [see Green 2022d]), thus killing the cells of the epithelium.

APOPTOSIS AND SELECTION IN DEVELOPMENT

Collections of cells can have emergent properties that far exceed the sum of their parts. By overproducing cells and then selecting for functions, the body can take advantage of such emergent properties. Selection can be positive, negative, or both, and most (if not all) selection involves cell death. Two examples of such selection in vertebrate development produce connectivity among neurons and self–nonself discrimination in the immune system. The latter probably represents the best example available of specification for cell death in a vertebrate system.

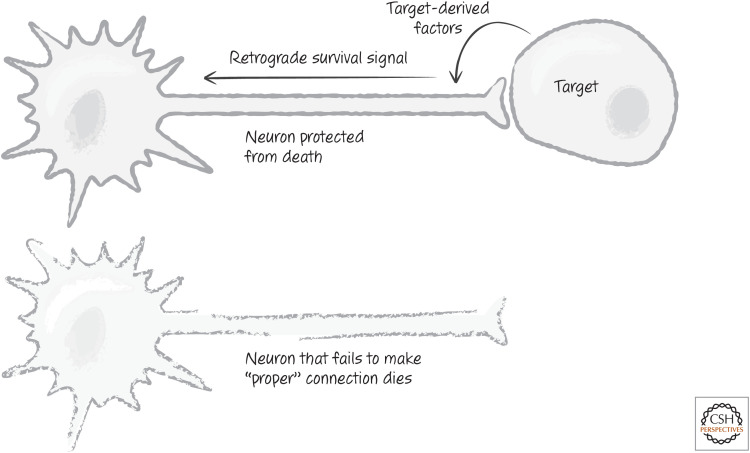

SELECTING NEURONS

In the developing nervous system, the axons of neurons extend to form connections with the dendrites of other neurons, and proper connectivity is essential for higher-order functions. One important way this can come about is proposed in the neurotrophism model. In this model, more neurons than will be ultimately used are produced, and these extend their axons toward another “target” population of neurons. Those that hit their targets then receive signals necessary to sustain their survival, whereas those that miss their targets die (Fig. 13).

Figure 13.

Cell death as a mechanism of neuronal selection. Neurons that fail to contact the appropriate target cell do not receive factors that promote their survival.

Neurotrophic survival factors, such as nerve growth factor, released by the target cells, bind to receptors (e.g., TrkA) on the recipient axon and are transported to the cell body. There, the signals generated by the receptor are easily transmitted to the mitochondria and the nucleus. We can mimic this effect by culturing neurons and then depriving them of survival signals. When developing sympathetic neurons are deprived of nerve growth factor, they undergo apoptosis. This apoptosis depends, in part, on the BH3-only proteins BIM, BAD, and HRK and the pro-apoptotic effectors BAX and BAK (see Green 2022e). Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) then occurs, and caspases are activated through the mitochondrial pathway. As discussed in Green (2022e), MOMP can result in caspase-independent cell death in many cell types. However, neurons deprived of nerve growth factor can survive post-MOMP if the mitochondrial pathway is blocked or disrupted. This might be why mice lacking APAF1, caspase-9, or caspase-3 sometimes have brain abnormalities and excess neurons (see Green 2022f). However, an alternative explanation for these extra neurons is discussed in more detail below.

There is a problem with the view that the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is crucial for neuronal development. Mice lacking BAX and BAK cannot engage the mitochondrial pathway, but the animals sometimes survive, and, although these animals display increased numbers of neurons, their behavior is not obviously disturbed. We have no good explanation for this. Perhaps cell death is not essential for neurotrophic selection and other mechanisms are involved.

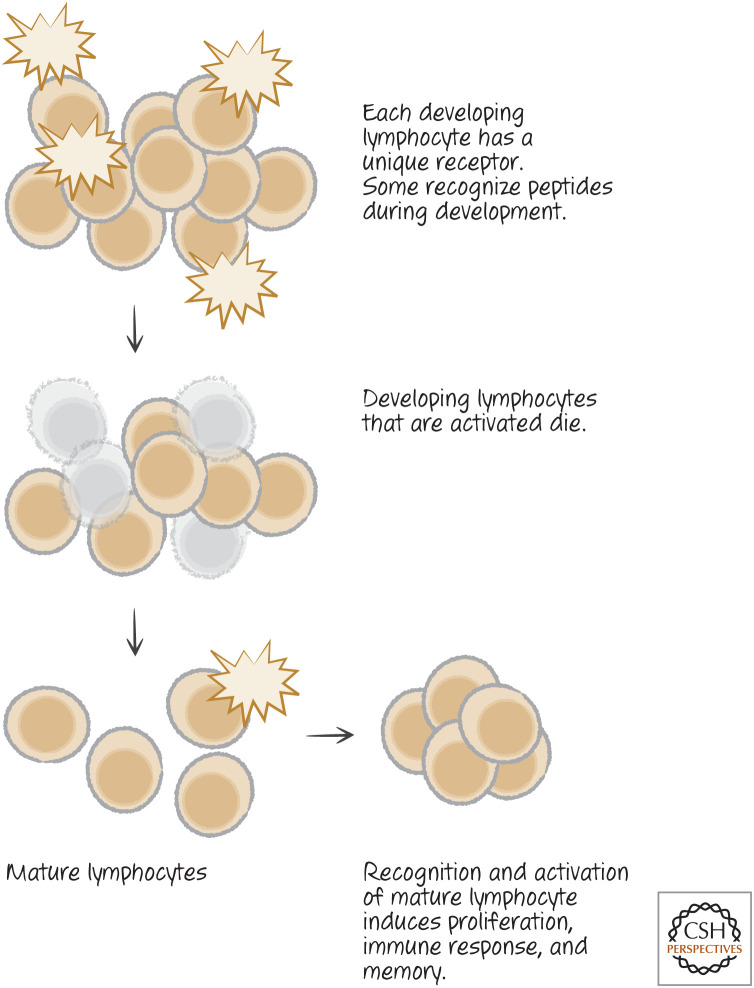

APOPTOSIS IN LYMPHOCYTE SELECTION

The immune system has a remarkable ability to discriminate between self-tissues and foreign invaders, and this self–nonself recognition is essential for survival in an opportunistic world.2 How this comes about involves a number of mechanisms, but we will focus on a central process that specifies developing lymphocytes to undergo apoptosis if they have the potential to recognize self-tissues that would obviously endanger the organism.

Vertebrate T lymphocytes express specialized T-cell receptors capable of recognizing small peptides presented to them on the surfaces of other cells (see Green 2022d). These receptors are generated in developing T cells by a random process involving rearrangements of gene segments that provide each T cell and its progeny with copies of a unique T-cell receptor of indeterminate specificity. The immature T-cell progenitors arise throughout life from hematopoietic stem cells that move to the thymus and differentiate into T cells.

At one point in the process, after the T-cell receptor has been generated and expressed on the cell surface, the cell undergoes a test in the form of the ligand for its receptor—a peptide bound to a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule on another cell (see Green 2022d). If the T cell recognizes this ligand, it undergoes apoptosis and is removed from the population. This process is called negative selection. In effect, the ligand for the T-cell receptor on a given cell can specify the cell for death at this stage of lymphocyte development. Later, after the cell matures, recognition of ligand by the T-cell receptor instead produces an immune response (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

The concept of negative selection. Cell death of activated lymphocytes during their development produces emergent self–nonself discrimination.

Negative selection helps self–nonself discrimination emerge in T cells. Peptides derived from proteins from the organism itself are always present, and therefore negative selection ensures that no T cell matures that can make immune responses to these self-peptides (at least, those that are present). Novel peptides that appear (e.g., during infection) are detected by T cells that developed when these were not present, and hence survived the test. Therefore, superficially, the discrimination is between peptides that are always present (self) and those that are only sometimes present (nonself).

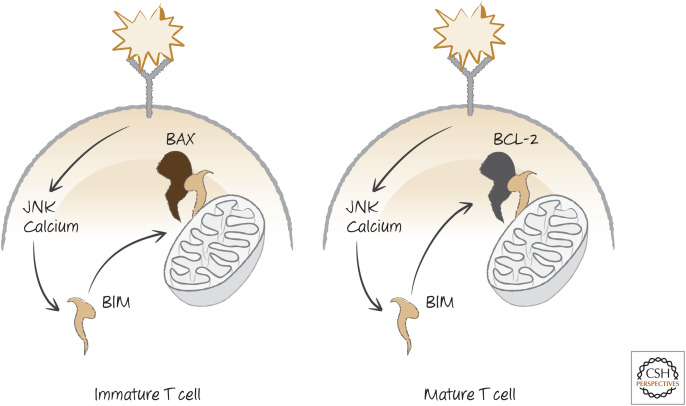

How T-cell receptor signaling results in apoptosis is at least partially understood. When stimulated, the receptor complex generates signals that cause a rapid elevation of calcium ions in the cytosol. Calcium stabilizes the BH3-only protein BIM, allowing it to accumulate.3 In addition, signaling also activates the mitogen-activated kinase JNK, which further stabilizes BIM and also phosphorylates BCL-2, and this decreases the anti-apoptotic activity of the latter (BIM is probably also transcriptionally induced in these cells, but the mechanisms have not been delineated). BIM then triggers the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Mice that lack JNK or BIM do not display apoptosis associated with negative selection. However, the surviving cells do not mature to produce autoimmune disease; so, clearly, there are additional checkpoints that control this important process if apoptosis fails.4 T-cell negative selection in the thymus nevertheless represents a clear example of specification for cell death mediated by a well-defined selection signal (Fig. 15).

Figure 15.

BIM and negative selection in T cells. T-cell activation induces JNK and elevated calcium, both of which stabilize BIM. In immature T cells, BIM induces apoptosis, but in mature T cells, this is blocked by BCL-2.

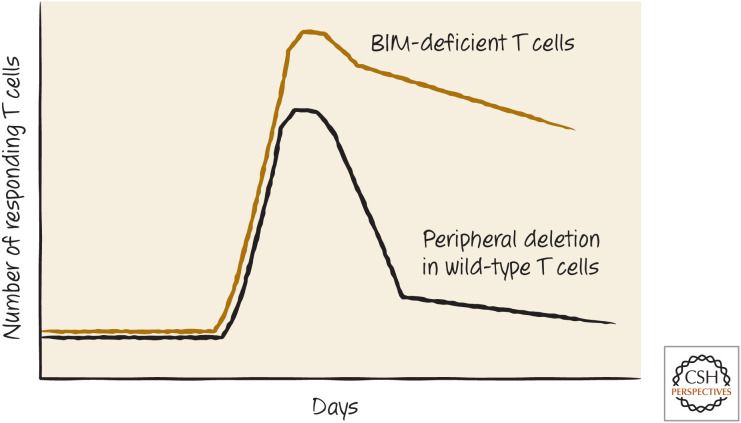

Once the T cell matures, BIM remains in place, but now elevated levels of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 appear to keep the cell alive. Mice that lack BCL-2 develop T cells, but these die in the first weeks after birth. If these animals also lack even one allele of Bim, however, the T cells mature normally and survive to function in immune responses.5 In normal individuals, the recognition of a ligand by a T cell causes it to proliferate rapidly, but this is followed a few days later by a population-contraction phase because of apoptosis of the clone, and this limits the immune response. This contraction phase is also dependent on BIM, and animals lacking BIM do not show this effect (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

Peripheral deletion and BIM. The absence of the BH3-only protein BIM inhibits the peripheral deletion of T cells that would otherwise reduce the numbers of responding cells.

Those cells that persist mediate immune memory to guard against the appearance of the ligand again. We do not know what factors determine which cells die after the initial expansion versus those that persist to preserve immune memory.

WHEN IS APOPTOSIS IMPORTANT IN MAMMALIAN DEVELOPMENT?

It is evident that cell death occurs during development in embryos and homeostasis in adults, but how crucial is apoptosis to these processes? We have discussed a number of striking developmental defects associated with removal of key components of the apoptotic machinery, some of which are necessary for survival. It is useful to revisit these to see how apoptosis participates in the developmental processes.

As seen in Green (2022f), mice lacking APAF1 or caspase-9 or mice with a mutation in cytochrome c that prevents APAF1 activation all display developmental defects that result in forebrain outgrowth, a catastrophic developmental abnormality. However, in some strain backgrounds, the same gene ablations have much smaller effects, and many mice survive into adulthood. As it turns out, this forebrain outgrowth is not due to a failure of the neurons to die through the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Instead, the defect is in the rate and efficiency of closure of the neural tube during development. Upon closure, the neural tube emits signals that halt the proliferation of developing neurons, and when this closure does not occur on schedule, the neurons continue to proliferate. Efficient apoptosis in the neural tube cells guides the closure of the neural tube and ensures that it occurs at the right developmental time. A delay in death can therefore result in the observed abnormalities.

The same is true for animals that lack BAX and BAK. Most of these animals (∼85%) die during development or shortly after birth. Triple deletion of BAX, BAK, and BOK is even more devastating; only ∼5% of these animals mature.6

Many of the animals that die around birth do so as a result of a severe cleft palate, resulting in them being unable to feed. As with the example above, apoptosis in the soft palate appears to be important in “guiding” the bones of the palate into proper position.

Nevertheless, some animals lacking BAX, BAK, and BOK survive into adulthood. These animals accumulate excessive myeloid and lymphoid cells (as do BAX, BAK double-deficient mice that survive), and therefore the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is important for homeostasis of these cells. However, most other tissues in these animals appear normal. Although the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is clearly important for normal development in most cases, the fact that some animals (and most of their tissues) can develop normally raises questions of how important this form of cell death is for most developmental and homeostatic processes.

Of course, there are other forms of cell death besides the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. At this point, we do not know whether such forms of cell death are important in development. We discussed the role of necroptosis in the embryonic lethality of animals that are deficient in caspase-8, FAS-associated death domain protein (FADD), or FLICE-like inhibitory protein (FLIP) (and this applies to a number of other effects of deletions of genes that regulate necroptosis), and there is no evidence that necroptosis, per se, is important in normal development. Mice that are deficient in RIPK3 or mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) cannot engage necroptosis in their cells, but develop normally.

Our foray into cell death in development has touched on how apoptosis and other forms of cell death are specified and how they function in some normal organismal processes. But cell death and survival also figure prominently in disease. We have seen how cell death is involved in ischemic injury and other forms of damage (see Green 2022c). We now turn to a discussion of how cell death and its regulation contribute to another important problem of defective cell and tissue homeostasis—cancer.

Footnotes

From the recent volume Cell Death: Apoptosis and Other Means to an End by Douglas R. Green

Additional Perspectives on Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

In a letter to Benedetto Varchi, he wrote, “Io intendo scultura quella che si fa per forza di levare: quella che si fa per via di porre è simile alla pittura.” Literally: “I mean, for sculpture, the one made by force of removing; the one through adding is similar to painting.” (Thanks to Gerry Melino for the translation.)

The concept of self–nonself discrimination by the immune system was proposed at the beginning of the 20th century and was so persuasive an idea that almost 50 years passed before we recognized that some diseases are actually caused by a failure of the mechanisms involved, leading to autoimmunity. It was around this time that we first realized that it is only an approximation of self–nonself discrimination that is learned by the immune system. It is a very complex process, and we concern ourselves here with only one of the steps in the learning mechanism and how cells are specified for apoptosis. Interested readers would do well to consult an immunology textbook for a detailed treatment.

In Green (2022e), some ways in which BIM is regulated are described. Another is through calcium, which appears to activate a phosphatase to remove a phosphate group from BIM that otherwise promotes its degradation.

In some experimental systems, defects in the recognition system that initiates negative selection permit such cells to mature, and the consequences include devastating multiorgan autoimmunity. It is likely that, in the absence of BIM-mediated apoptosis, stimulated cells differentiate into immunosuppressive regulatory T cells that inhibit any autoreactivity (see Green 2022d).

The story is more interesting than related here, with additional insights into apoptosis and development. Mice that lack BCL-2 develop fairly normally to birth, but turn gray within 3 weeks and die of kidney failure a few weeks later. If the animals lack one allele of Bim, they survive (but have gray hair). If they lack both alleles of Bim, their coat color is normal.

As mentioned in Green (2022e), this finding indicates that there are signals (yet to be discovered) that engage BOK during development.

ADDITIONAL READING

Cell Death in Development

Conradt B. 2009. Genetic control of programmed cell death during animal development. Annu Rev Genet 43: 493–523.

Baehrecke EH. 2002. How death shapes life during development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 779–787.

Meier P, Finch A, Evan G. 2000. Apoptosis in development. Nature 407: 796–801.

Opferman JT, Kothari A. 2018. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members in development. Cell Death Differ 25: 37–45.

Kutscher LM, Shaham S. 2017. Non-apoptotic cell death in animal development. Cell Death Differ 24: 1326–1336.

Cell Death in Nematode Development

Ellis RE, Yuan JY, Horvitz HR. 1991. Mechanisms and functions of cell death. Annu Rev Cell Biol 7: 663–698.

An early survey of cell death in nematode development.

Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. 1986. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell 44: 817–829.

The original paper defining the genetic basis for cell death in nematode development.

Maurer CW, Chiorazzi M, Shaham S. 2007. Timing of the onset of a developmental cell death is controlled by transcriptional induction of the C. elegans ced-3 caspase-encoding gene. Development 134: 1357–1368.

Abraham MC, Lu Y, Shaham S. 2007. A morphologically conserved nonapoptotic program promotes linker cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell 12: 73–86.

Cell death in the tail-spike cell.

Ellis RE, Horvitz HR. 1991. Two C. elegans genes control the programmed deaths of specific cells in the pharynx. Development 112: 591–603.

The identification of CES1 and CES2 in specifying cell death in nematode development.

Metzstein MM, Hengartner MO, Tsung N, Ellis RE, Horvitz HR. 1996. Transcriptional regulator of programmed cell death encoded by Caenorhabditis elegans gene ces-2. Nature 382: 545–547.

Zarkower D, Hodgkin J. 1992. Molecular analysis of the C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-1: a gene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Cell 70: 237–249.

Cell Death in Fly Development

Hay BA, Guo M. 2006. Caspase-dependent cell death in Drosophila. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 623–650.

Baehrecke EH. 2000. Steroid regulation of programmed cell death during Drosophila development. Cell Death Differ 7: 1057–1062.

Rusconi JC, Hays R, Cagan RL. 2000. Programmed cell death and patterning in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ 7: 1063–1070.

Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. 2007. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell 131: 1137–1148.

The first clear-cut description of autophagy-dependent cell death in development.

Denton D, Shravage B, Simin R, Mills K, Berry DL, Baehrecke EH, Kumar S. 2009. Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol 19: 1741–1746.

Another example of developmental cell death dependent on autophagy.

Cell Death in Vertebrate Development

Montero JA, Hurlé JM. 2010. Sculpturing digit shape by cell death. Apoptosis 15: 365–375.

Coucouvanis E, Martin GR. 1995. Signals for death and survival: a two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo. Cell 83: 279–287.

Ishizuya-Oka A, Hasebe T, Shi YB. 2010. Apoptosis in amphibian organs during metamorphosis. Apoptosis 15: 350–364.

Cell Death and Selection

Yuen EC, Howe CL, Li Y, Holtzman DM, Mobley WC. 1996. Nerve growth factor and the neurotrophic factor hypothesis. Brain Dev 18: 362–368.

O'Leary DD, Fawcett JW, Cowan WM. 1986. Topographic targeting errors in the retinocollicular projection and their elimination by selective ganglion cell death. J Neurosci 6: 3692–3705.

An example of how cell death can select for proper neuronal connections.

Daley SR, Teh C, Hu DY, Strasser A, Gray DHD. 2017. Cell death and thymic tolerance. Immunol Rev 277: 9–20.

Li KP, Shanmuganad S, Carroll K, Katz JD, Jordan MB, Hildeman DA. 2017. Dying to protect: cell death and the control of T-cell homeostasis. Immunol Rev 277: 21–43.

Bouillet P, Purton JF, Godfrey DI, Zhang LC, Coultas L, Puthalakath H, Pellegrini M, Cory S, Adams JM, Strasser A. 2002. BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is required for apoptosis of autoreactive thymocytes. Nature 415: 922–926.

The role of BIM in the negative selection of immature T cells.

FIGURE CREDITS

- Abraham MC, Lu Y, Shaham S. 2007. A morphologically conserved nonapoptotic program promotes linker cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell 12: 73–86. 10.1016/j.devcell.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucouvanis E, Martin GR. 1995. Signals for death and survival: a two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo. Cell 83: 279–287. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90169-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gañan Y, Macías D, Basco RD, Merino R, Hurle JM. 1998. Morphological diversity of the avian foot is related with the pattern of msx gene expression in the developing autopod. Dev Biol 196: 33–41. 10.1006/dbio.1997.8843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner A, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. 2010. Functional cooperation of the proapoptotic Bcl2 family proteins Bmf and Bim in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 30: 98–105. 10.1128/MCB.01155-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JFR, Harmon B, Searle J. 1974. An electron-microscope study of cell deletion in the anuran tadpole tail during spontaneous metamorphosis with special reference to apoptosis of striated muscle fibres. J Cell Sci 14: 571–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-Y, Baehrecke EH. 2001. Steroid regulation of autophagic programmed cell death during development. Development 128: 1443–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsten T, Ross AJ, King A, Zong WX, Rathmell JC, Shiels HA, Ulrich E, Waymire KG, Mahar P, Frauwirth K, et al. 2000. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bak and Bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol Cell 6: 1389–1399. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer CW, Chiorazzi M, Shaham S. 2007. Timing of the onset of a developmental cell death is controlled by transcriptional induction of the C. elegans ced-3 caspase-encoding gene. Development 134: 1357–1368. 10.1242/dev.02818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP, Baehrecke EH. 2008. Eating on the fly: function and regulation of autophagy during cell growth, survival and death in Drosophila. Autophagy 4: 557–562. 10.4161/auto.5782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. 1983. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 100: 64–119. 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuzarte-Luís V, Hurlé JM. 2002. Programmed cell death in the developing limb. Int J Dev Biol 46: 871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- *.Green DR. 2022a. A matter of life and death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022b. Caspase activation and inhibition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022c. Nonapoptotic cell death pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022d. The burial: clearance and consequences. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022e. The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, Part II: the BCL-2 protein family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Green DR. 2022f. The mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, Part I: MOMP and beyond. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a041038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]