Abstract

Background

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease is a common debilitating condition that predominantly affects young adults, with a profound impact on their activities of daily living. The condition is treated surgically, and in some cases the wound in the natal cleft is left open to heal by itself. Many dressings and topical agents are available to aid healing of these wounds.

Objectives

To assess the effects of dressings and topical agents for the management of open wounds following surgical treatment for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus in any care setting.

Search methods

In March 2021, we searched the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and EBSCO CINAHL Plus. We also searched clinical trials registries for ongoing and unpublished studies, and we scanned reference lists of included studies, reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology reports to identify additional studies. There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

We included parallel‐group randomised controlled trials (RCTs) only. We included studies with participants who had undergone any type of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease surgery and were left with an open wound.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence for each outcome.

Main results

We included 11 RCTs comprising 932 participants. Two studies compared topical negative pressure wound therapy (TNPWT) with conventional open wound healing, two studies compared platelet‐rich plasma with sterile absorbent gauze, and the other seven studies compared various dressings and topical agents. All studies were at high risk of bias in at least one domain, whilst one study was judged to be at low risk of bias in all but one domain. All studies were conducted in secondary care. Mean participant ages were between 20 and 30 years, and nearly 80% of participants were male. No studies provided data on quality of life, cost‐effectiveness, pain at first dressing change or proportion of wounds healed at 6 or 12 months, and very few adverse effects were recorded in any study.

It is unclear whether TNPWT reduces time to wound healing compared with conventional open wound healing (comparison 1), as the certainty of evidence is very low. The two studies provided conflicting results, with one study showing benefit (mean difference (MD) −24.01 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) −35.65 to −12.37; 19 participants), whilst the other reported no difference. It is also unclear whether TNPWT has any effect on the proportion of wounds healed by 30 days (risk ratio (RR) 3.60, 95% CI 0.49 to 26.54; 19 participants, 1 study; very low‐certainty evidence). Limited data were available for our secondary outcomes time to return to normal daily activities and recurrence rate; we do not know whether TNPWT has any effect on these outcomes.

Lietofix cream may increase the proportion of wounds that heal by 30 days compared with an iodine dressing (comparison 4; RR 8.06, 95% CI 1.05 to 61.68; 205 participants, 1 study; low‐certainty evidence). The study did not provide data on time to wound healing.

We do not know whether hydrogel dressings reduce time to wound healing compared with wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine (comparison 5; MD −24.54 days, 95% CI −47.72 to −1.36; 31 participants, 1 study; very low‐certainty evidence). The study did not provide data on the proportion of wounds healed. It is unclear whether hydrogel dressings have any effect on adverse effects as the certainty of the evidence is very low.

Platelet‐rich plasma may reduce time to wound healing compared with sterile absorbent gauze (comparison 6; MD −19.63 days, 95% CI −34.69 to −4.57; 210 participants, 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence). No studies provided data on the proportion of wounds healed. Platelet‐rich plasma may reduce time to return to normal daily activities (MD −15.49, 95% CI −28.95 to −2.02; 210 participants, 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence).

Zinc oxide mesh may make little or no difference to time to wound healing compared with placebo (comparison 2; median 54 days in the zinc oxide mesh group versus 62 days in the placebo mesh group; low‐certainty evidence). We do not know whether zinc oxide mesh has an effect on the proportion of wounds healed by 30 days as the certainty of the evidence is very low (RR 2.35, 95% CI 0.49 to 11.23).

It is unclear whether gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge reduces time to wound healing compared with no dressing (comparison 7; MD −1.40 days, 95% CI −5.05 to 2.25; 50 participants, 1 study; very low‐certainty evidence). The study did not provide data on the proportion of wounds healed.

Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC)‐coated dressings may make little or no difference to time to wound healing compared with alginate dressings (comparison 8; median 69 (95% CI 62 to 72) days in the DACC group versus 71 (95% CI 69 to 85) days in the alginate group; 1 study, 246 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

One study compared a polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing with an alginate dressing (comparison 3) whilst another study compared a hydrocolloid dressing with an iodine dressing (comparison 9). It is unclear whether either intervention has any effect on time to wound healing as the certainty of evidence is very low.

Authors' conclusions

At present, the evidence that any of the dressings or topical agents contained in this review have a benefit on time to wound healing, the proportion of wounds that heal at a specific time point or on any of the secondary outcomes of our review ranges from low certainty to very low certainty. There is low‐certainty evidence on the benefit on wound healing of platelet‐rich plasma from two studies and of Lietofix cream and hydrogel dressings from single studies. Further studies are required to investigate these interventions further.

Plain language summary

How effective are dressings and topical agents in the management of wounds after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus of the buttocks?

Key messages

‐ Platelet‐rich plasma (part of the participant's own blood that promotes tissue regeneration) may reduce time to wound healing compared with sterile gauze ‐ Lietofix skin repair cream may help wounds to heal by 30 days compared with a dressing with iodine (which helps to reduce bacteria in the wound) ‐ It is not clear whether hydrogel dressings (designed to keep the wound moist) reduce time to wound healing compared with wound cleaning with iodine

What is pilonidal sinus disease of the buttocks?

Pilonidal sinus disease of the buttocks is a common painful condition that mainly affects young adults.

It occurs in the natal cleft (the groove between the buttocks). It begins as infected or inflamed hair follicles. A vacuum effect, created by the motion of the buttocks, may draw more hairs down into the inflamed area. Symptoms can be very painful and sometimes last for a long time.

How is pilonidal sinus of the buttocks treated?

The condition is often treated surgically, by cutting out the inflamed area containing the hair and debris, and in some cases the wounds are not closed by stitches but left open to heal naturally. A lot of dressings and topical agents (creams or lotions) are available to help these wounds heal.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to see which dressings and topical agents are better for treating open wounds after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus of the buttocks.

For each intervention we looked at:

‐ how long it took wounds to heal; ‐ the number of wounds healed after 30 days, 6 months and 1 year; ‐ whether the wounds came back; ‐ how long it took people who had been treated to return to normal daily activities; ‐ quality of life; ‐ value for money; ‐ pain during the first dressing change; ‐ harmful effects (for example surgical site infection or allergic reaction) after treatment.

What did we do?

We included participants of any age and either sex who had been treated in any care setting. We searched for studies where:

‐ participants had been treated for pilonidal sinus disease of the buttocks and were left with an open wound; ‐ different dressings and topical agents were compared to see how effective they were for helping wounds to heal.

What did we find?

We included 11 studies with a combined total of 932 participants. Two studies compared topical negative pressure wound therapy (which applies controlled suction to the surface of the wound) with simple wound dressings. Two studies compared platelet‐rich plasma with sterile absorbent gauze. The other seven studies compared various dressings and topical agents. All the studies took place in hospitals.

‐ No studies provided data on quality of life, value for money or pain at the first dressing change. ‐ We do not know if topical negative pressure wound therapy helps wounds to heal faster than simple wound dressings. ‐ Lietofix skin repair cream may help wounds to heal by 30 days. ‐ We do not know if hydrogel dressings help wounds to heal faster or protect better against surgical site infection compared with wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine. ‐ Platelet‐rich plasma may reduce the time to wound healing compared with sterile absorbent gauze. ‐ Compared with placebo mesh, mesh with zinc oxide (which is thought to have healing properties) may have little or no effect on whether wounds heal by 30 days, and it is unclear if it reduces the time to wound healing. ‐ We do not know if collagen sponge soaked in antibiotic has any effect on the time to wound healing compared with no dressing. ‐ Dressings coated with dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (a substance that bacteria sticks to) may make little to no difference to wound healing time compared with alginate dressings (derived from seaweed).

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We are not very confident in the evidence because there were only one or two studies in each comparison and most of the studies were very small. It is also possible that people in the studies were aware of what treatment they were getting.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence in this review is up to date to March 2021.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Pilonidal sinus disease is a common, debilitating condition, first described in the literature nearly 200 years ago (Mayo 1833). The etymology of the word 'pilonidal' is from the Latin words 'pilus' and 'nidus', with the literal translation being 'nest of hair'. The condition predominantly affects young adults and is more common in men, obese individuals and those with a sedentary occupation (Søndenaa 1995a). The natal cleft (the recess between the buttocks) is by far the most common site for pilonidal sinus formation, but it can also occur in other areas of the body, such as the umbilicus (Meher 2016), or the web spaces of the fingers (Stern 2004). Pilonidal sinus disease occurring in the natal cleft is often termed 'sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease', referring to its anatomical location between the sacrum and the coccyx. The disease begins as a folliculitis (infection and inflammation of hair follicles), leading to blockage of the follicle. A vacuum effect, created by the motion of the buttocks, may draw further hairs down into the pits (Bendewald 2007). Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease has an estimated incidence of 26 cases per 100,000 (calculated using secondary care data from Norway; Søndenaa 1995a). It has a range of clinical presentations, from acute abscesses to a painful chronic condition.

An acute pilonidal abscess is managed by incision and drainage, as is the case for abscesses of other aetiologies. However, many people may present with a chronic pilonidal sinus (a longstanding, intermittently discharging sinus) either without ever having experienced an acute abscess, or after they have had an acute abscess drained. These people may go on to have one of many possible elective surgical procedures to treat the underlying pilonidal sinus. These operations can range from minimally invasive procedures (Lund 2017; Tien 2018; Sian 2018), to wide excision of the diseased tissue. After excision, a variety of techniques have been described to deal with the wound (Al‐Khamis 2010). It may be packed and left open to heal by secondary intention (i.e. the wound is left unstitched), meaning that the wound edges are not brought together, and the defect is healed by the growth of new granulation tissue. Alternatively, it can be closed primarily (where the wound edges are brought together), using either a simple sutured closure or a more complex operation involving the use of tissue flaps (Al‐Khamis 2010). A previous Cochrane Review concluded that there was no evidence of a clear benefit for either off‐midline primary closure or leaving wounds open to heal by secondary intention over each other; hence both techniques are routinely employed (Al‐Khamis 2010). It is also estimated that up to 20% of complications from wounds closed primarily are cases of dehiscence (wound breakdown), which creates a new open wound that then has to heal by secondary intention (Onder 2012).

Management of an open wound can have a profound physical and psychological impact on the affected person (McCaughan 2018), leading to the inability to carry out their normal activities of daily living (Stewart 2012). They may also require multiple visits to healthcare professionals for dressing changes, and the healing process may take months (Chetter 2017).

Description of the intervention

The objective of managing an open wound following pilonidal sinus surgery is to promote rapid healing by secondary intention, control excess exudate (the fluid that leaks from the wound) and minimise the risk of pilonidal sinus recurrence. The location of a wound after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease is the natal cleft, which is close to the anus. For this reason, care must be taken to prevent faecal contamination of the wound and possible subsequent infection (Harris 2012). A range of dressings and topical agents are available for managing open cavity wounds. Those recommended for treating pilonidal sinus wounds include:

alginates (a highly absorbent fibre derived from brown seaweed; BNF 2019a);

hydrocolloids (waterproof dressings intended to promote a moist wound healing environment whilst providing a barrier to bacteria; Fowler 2012);

topical antimicrobials (dressings containing ingredients such as honey, silver or iodine to reduce the bacterial load in a wound; BNF 2019b);

foam dressings (dressings made from a polyurethane foam designed to absorb exudate and cushion the wound; BNF 2019c); and

hydrogels (gel‐based dressings designed to absorb exudate whilst also maintaining a moist wound environment; Jones 2005).

How the intervention might work

Normal wound healing is a complex process that occurs in three main phases: inflammation, proliferation and remodelling. A variety of problems can disrupt normal, orderly wound healing, resulting in the development of chronic, non‐healing wounds. Progression from the inflammatory stage may be prevented if the wound develops a chronic deep infection or a bacterial biofilm, or contains a foreign body or area of necrotic tissue. This can initiate a process of chronic inflammation. Excessive tension on wound edges and repeated lateral pressure forcing the wound apart can prevent proper progress of the proliferative and remodelling phases. Poor circulation can compromise all three stages of acute wound healing. Interventions to promote wound healing therefore seek to prevent or resolve these issues (Han 2017).

Pioneering work on wounds made experimentally in pigs demonstrated that wounds maintained in a moist environment healed more effectively than those allowed to scab over (Winter 1962). It has since been shown that retaining a limited amount of exudate on the wound allows for autolytic debridement, supporting the inflammatory phase of wound healing (Han 2017). Today, all advanced wound‐dressing products help to create a moist wound environment to facilitate healing.

The anatomical location of sacrococcygeal pilonidal wounds results in a risk of faecal contamination, leading to a high bacterial load within the wound (Søndenaa 1995b). Furthermore, the area has relatively poor blood supply, and is subjected to tension and lateral pressure when the person sits. The ideal dressing for use in a sacrococcygeal pilonidal wound would therefore need to absorb excess exudate, fill any cavities, prevent contamination to reduce the bacterial load on the wound bed, encourage blood supply and maintain a moist environment (Harris 2012).

Alginate dressings are considered to be highly absorptive, and are intended to remove excess slough and exudate from the wound (Dabiri 2016). Foams have a similar mechanism of action, and may also reduce trauma to the wound during dressing changes (Han 2017). Antimicrobial solutions and dressings, such as silver and polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB), may reduce bacterial load in the wound (Collier 2017; Schultz 2017), and there is some evidence for their effectiveness against biofilms (Percival 2008).

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has multiple possible mechanisms of action, including maintaining a moist environment whilst removing excess exudate, optimising blood flow, applying traction to wound edges and maintaining a seal to prevent bacterial contamination of the wound. There is some evidence of its effectiveness in improving healing in chronic wounds (Venturi 2005).

The interventions detailed above are examples of possible wound treatments. Any one, or a combination of possible treatments, may help to mitigate the challenges of healing open sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus wounds. It may be that advanced wound products are no more effective than simple dressings.

Why it is important to do this review

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease is a common condition, which has already been the subject of two Cochrane Reviews within the Cochrane Wounds Group (Al‐Khamis 2010; Lund 2017). A range of products and non‐surgical techniques is available to manage open wounds left after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease, and some of these options have been assessed in randomised controlled trials. However, there is no current consensus on the optimal management of these wounds. To date, there has not been a systematic review of the evidence regarding the most effective means of achieving healing of open pilonidal sinus wounds after surgery.

Objectives

To assess the effects of dressings and topical agents for the management of open wounds following surgical treatment for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus in any care setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We only included parallel‐group randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of individuals. We would also have included cluster‐randomised trials and unpublished studies if we had identified any. We excluded cross‐over studies, as the intervention period covers the entire healing process, with no possibility of a washout period between interventions. Our search had no date or language limitations.

Types of participants

We included studies in which all participants had undergone surgical treatment for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease that left an open wound in the natal cleft. The wounds managed with topical agents or dressing could be those deliberately left open to heal by secondary intention, or those that had broken down after primary closure. We included all ages and both sexes of participant in this review, and we did not restrict studies by care setting of wound management (primary or secondary care).

If we had identified studies containing a mixture of participants (some with wounds from other types of surgery) and the data were not presented separately for the different groups, we would have contacted the corresponding authors to attempt to acquire the data specific to wounds from sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease surgery. If we had identified studies involving a mixture of wounds from sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease surgery (some healing by primary intention and others by secondary intention) and the data for the respective participants were not presented separately, we would have contacted the corresponding authors to attempt to obtain separate datasets. If we had been unable to obtain separate data for pilonidal sinus healing by secondary intention in either case, then these mixed population studies would have been excluded.

Types of interventions

The interventions of interest were any topical agent or dressing applied to either a wound deliberately left open to heal by secondary intention, or a wound that had broken down after primary closure, compared with any other topical agent or dressing. We classified the interventions according to the categories outlined in the relevant section of the British National Formulary BNF 2019a. We also included studies that compared any topical agent or dressing with no intervention, although we expected these to be rare. We did not include studies with co‐interventions, unless both groups had received these.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome for this review is complete wound healing. We regarded the following measures as providing the most relevant and rigorous measures of this outcome.

Time to wound healing (time in days until wound has healed), assessed clinically by researchers or a clinical team, using a validated wound healing score. Where possible, we aimed to present time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Mean time‐to‐healing data were only included where we were certain that all wounds had healed.

Proportion of wounds healed (number of wounds healed/not healed) during short (30‐day), medium (6‐month) and long‐term (1‐year) follow‐up, assessed clinically by researchers or a clinical team

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence rate (number of wounds that recurred at the same site as the original wound/number of wounds that did not recur), reported during the longest follow‐up in the study and assessed clinically by researchers or a clinical team

Time (in days) to return to normal daily activities, as described during study follow‐up. Where possible, we aimed to present data as time‐to‐event (HR).

Quality of life, measured using validated scales such as the 36‐Item Short Form Survey (SF‐36; Ware 1992), EuroQol‐5 Dimension (EQ‐5D; EuroQol 1990) or the Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule (Price 2004) during study follow‐up

Cost‐effectiveness, assessed using the quality‐adjusted life year (QALY) for the primary outcomes

Pain, measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale (VAS) during the first dressing change

Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) during study follow‐up, reported as the number of participants in each group with an adverse effect, assessed clinically by researchers or a clinical team

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to identify reports of relevant clinical studies.

The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register (searched 3 March 2021)

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library (searched 3 March 2021)

Ovid MEDLINE including In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (1946 to 3 March 2021)

Ovid Embase (1974 to 3 March 2021)

EBSCO CINAHL Plus (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 3 March 2021)

The search strategies for the Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register, CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase and EBSCO CINAHL Plus can be found in Appendix 1. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version, 2008 revision (Lefebvre 2021). We combined the Ovid Embase search with an adapted version of the Cochrane Centralised Search Project filter for identifying RCTs in Ovid Embase developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2021). We combined the CINAHL Plus search with the trial filter developed by Glanville et al. (Glanville 2019). There were no restrictions with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

We also searched the following clinical trials registries.

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 3 March 2021)

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (trialsearch.who.int); searched 3 March 2021)

Search strategies for clinical trial registries can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of identified studies to identify other potentially relevant studies. We used Google Scholar to identify potentially relevant studies that cited studies included from the electronic searches.

We also searched the last three years' conference proceedings of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, European Society of Coloproctology, the European Wound Management Association, Wounds UK and the Journal of Wound Care conference.

Data collection and analysis

We carried out data collection and analysis according to the methods stated in the published protocol (Herrod 2019), which were based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Li 2021). Changes from the protocol or previous published versions of the review are documented in Differences between protocol and review.

Selection of studies

Two authors (PH and TM) independently screened the titles and abstracts using Rayyan systematic review management software (Ouzzani 2016), resolving any disagreement by consulting a third author (PJH) until reaching consensus. Two authors (PJH and EH) then independently screened potentially relevant full texts against the inclusion criteria, resolving any disagreement by consulting a third author (BD). We identified any duplicate publications at this stage using author name, study date and details of the intervention. We obtained all publications for studies that had multiple references. Whilst we only included the study once in the review, we obtained all publications to maximise the amount of extracted data. If we had found studies that satisfied our inclusion criteria but did not report any relevant outcomes, we would have contacted the authors to enquire about the missing data.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (PJH and EH) independently collected and extracted study data into an electronic database. The authors compared the extracted data, resolving any disagreements by consensus and consultation with a third author (BD) when required, prior to transferring the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5; Review Manager 2020). Where relevant data were missing from studies, we attempted to contact the study authors to obtain this.

We extracted the following data.

Country in which the study took place

Publication status of study

Source of funding

Care setting

Study design

Number of participants randomised to each study arm

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participant baseline characteristics (including age, sex, BMI)

Details of operation performed

Details of treatment regimen

Details of any co‐interventions

Duration of follow‐up

Primary and secondary outcomes of the studies (with definitions)

Outcome data for primary and secondary outcomes

Number of withdrawals per group, with reasons

Had we identified studies with more than two intervention arms, each would have been used in the relevant comparisons. Intervention arms that were similar in nature would have been combined into one group as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (PJH and EH) assessed risk of bias independently, resolving any disagreement by consensus and involving a third author when required. We used the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB1; Higgins 2017), described in Appendix 2. We assessed random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. We accepted that blinding in these studies would be difficult and expected many to be at high risk for this domain. We then assigned each study either low, high or unclear risk of bias using the criteria of the Cochrane tool. To assess selective outcome reporting, we searched clinical trials databases for the original study registration or MEDLINE for a pre‐published protocol, and then compared this with the published study. We presented risk of bias data in a summary table (Figure 1) and a risk of bias graph (Figure 2). We decided that a significant imbalance in participant characteristics at baseline constituted a high risk of 'other' bias and reported this accordingly. If we had identified any cluster‐randomised trials, we would have also considered the risk of bias in terms of recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis and comparability with individually randomised trials (Higgins 2021), as described in Appendix 3).

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Measures of treatment effect

For the primary outcome of time to wound healing, we planned to report time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs). For studies reporting time‐to‐event data without hazard ratios, we planned to estimate these using other reported outcomes (Tierney 2007), however this was not possible. We presented dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcome data, we presented mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. We only used a mean time‐to‐healing measure where it was clear that all wounds had healed. If different scales had been used, we would have presented results as standardised mean differences (SMDs). We planned to analyse continuous outcomes dependent on baseline risk (pain) using meta‐regression, presenting reductions from a meta‐regression equation (Doleman 2018), but we found no such data.

Unit of analysis issues

We expected nearly all studies to be parallel‐group RCTs, where each participant would be the unit of analysis. Since participants only have one natal cleft and all recognised operations for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease form only one wound, we did not anticipate any unit of analysis issues.

We planned to analyse any cluster‐randomised trials using appropriate methods that take account of unit of analysis issues (Donner 2002). Had we found any studies of this type, we would have included the data in the analysis using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021). We would have used the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient to calculate an effective sample size if the primary study had conducted an inappropriate analysis, and we would have directly entered effect estimates if the primary study had derived these using appropriate methods (e.g. multilevel models). We would have used the generic inverse variance method for the meta‐analysis of cluster‐randomised trials.

Dealing with missing data

Where we identified studies with missing data, we first attempted to contact the corresponding author to obtain them. Where we did not receive a response, we planned to extract data from published graphs using WebPlotDigitizer, however this was not possible. Where the publications did not report standard deviations, we attempted to estimate these from other included studies in the review or from other reported measures of variance such as the interquartile range. Where studies reported medians rather than means, we reported this data separately in a narrative synthesis, but excluded them from the meta‐analysis. Had there been any participants with data missing for dichotomous outcomes, we would have assumed they had not suffered the event (best‐case scenario). In addition, we would have conducted a sensitivity analysis assuming participants with missing data had suffered the event (worst‐case scenario). Where data that were required to calculate time‐to‐event outcomes were missing, and study authors could not provide additional data, we presented data as mean differences instead.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity during the data extraction process using information on study populations, nature of the interventions and types of wounds. Where we found substantial clinical heterogeneity, we discussed the studies in a narrative review without pooling them for meta‐analysis. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 measure (Higgins 2003), interpreting the resulting values as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2021).

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

We expected heterogeneity between participants whose wound was deliberately left open compared with those whose wound had broken down after primary closure. We planned to investigate this heterogeneity using subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

For any analysis including 10 or more studies, we planned to assess publication bias qualitatively using funnel plots and quantitatively using Egger’s regression test (Egger 1997). For continuous outcomes dependent on baseline risk (pain), we planned to use a novel test based on meta‐regression residuals and inverse sample size (Doleman 2020). We would have regarded P < 0.1 as evidence of small study effects and therefore possible publication bias.

Data synthesis

We grouped dressings and topical agents for synthesis using the classification described within the British National Formulary wound management products section (BNF 2019d). We combined studies in random‐effects meta‐analyses where possible. We presented effect estimates and precision using forest plots. We calculated pooled relative risks and mean differences as appropriate. All pooled outcomes are presented with 95% CI. We combined hazard ratios and continuous outcomes using generic inverse variance if the studies only reported effect estimates and did not provide enough information to enter raw data. Where studies reported hazard ratios and continuous outcomes for the same outcome, we analysed and reported these separately. We aggregated results using a DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model for all analyses as we anticipated an element of clinical heterogeneity and therefore different underlying effects to estimate. We used Review Manager 2020 to aggregate study data and had planned to use Stata to conduct Egger's linear regression test (Egger 1997). We did not conduct a network meta‐analysis of interventions.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform a subgroup analysis to explore differences in the primary and secondary outcomes between participants whose wound was deliberately left open and those whose wound had dehisced after primary closure, but none of the included studies made this distinction.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to repeat meta‐analyses removing studies we considered to be at high risk of bias in any domain. In addition, we planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis assuming the worst‐case scenario, meaning participants with missing follow‐up data had either suffered an event (if negative, for example recurrence) or did not achieve a desired outcome (if positive, for example proportion of wounds healed).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in summary of findings tables (Deeks 2021). The summary of findings tables also included an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2013). The primary and secondary outcomes included in the summary of findings tables are

time to wound healing;

proportion of wounds healed;

cost effectiveness;

pain;

adverse effects.

We downgraded the certainty of evidence from high to moderate, low, or very low if concerns existed in any of the five domains. Two review authors independently downgraded the evidence, reaching agreement by consensus. We carried out GRADE assessment on all outcomes in the review. Characteristics of the evidence that could result in downgrading include:

limitations in the design and implementation of available studies, suggesting a high likelihood of bias (e.g. high risk in blinding);

indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, or outcomes);

unexplained heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), or inconsistency of results not explained through subgroup analyses;

imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals);

evidence of publication bias (P < 0.1 on Egger’s linear regression test and visual evidence on funnel plot).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

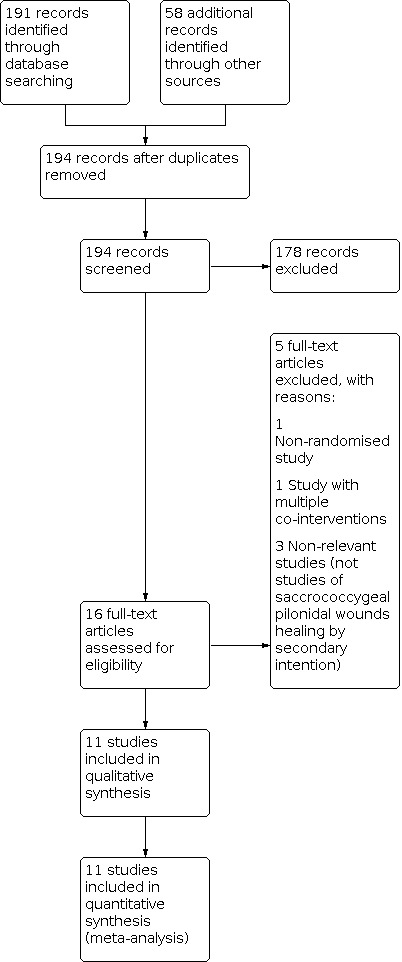

We identified 191 studies from searches of the electronic databases and 58 studies from trial registry searches (Figure 3). We did not identify any further studies from reference lists, conference abstracts or from searches of studies citing included studies on Google Scholar. After removing duplicates, we screened 194 records, excluding 178 and reviewing the full text of the remaining 16. We considered 11 randomised controlled trials to be eligible for inclusion in the final review (Agren 2005; Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Mohammadi 2017; Ozbalci 2014; Romain 2020; Viciano 2000).

3.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included 11 RCTs comprising 932 participants (Agren 2005; Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Mohammadi 2017; Ozbalci 2014; Romain 2020; Viciano 2000). All studies were published as full manuscripts, and had been conducted in secondary care in European and Middle Eastern countries. Ten studies were published in English and one was only available in Turkish (Characteristics of included studies). We translated this study with Google Translate. The earliest study was published in 1996 and the latest in 2020. The interventions and comparators used in our included studies are displayed in Table 8.

1. Summary of interventions and comparators in included studies.

| Study | Intervention | Comparator |

| Agren 2005 | Zinc oxide mesh | Placebo mesh |

| Banasiewicz 2013 | Topical negative pressure wound therapy | Conventional absorbent dressing |

| Berry 1996 | Polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing | Calcium sodium alginate dressing |

| Biter 2014 | Topical negative pressure wound therapy | Silicone dressing |

| Giannini 2019 | Lietofix cream | Iodoform dressing |

| Gohar 2020 | Platelet‐rich plasma | Absorbent sterile cotton gauze |

| Kayaoglu 2006 | Hydrogel dressing | Wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine |

| Mohammadi 2017 | Platelet‐rich plasma | Absorbent sterile cotton gauze |

| Ozbalci 2014 | Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge | No intervention |

| Romain 2020 | Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride‐coated dressing | Alginate dressing |

| Viciano 2000 | Hydrocolloid dressing | Iodine dressing |

Participants and surgery

The mean age of participants in all included studies was between 20 and 30 years, in keeping with the previously described peak incidence of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease (Søndenaa 1995a). Most participants (78%) were male, which was to be expected as male sex is a risk factor for the disease (Søndenaa 1995a). The surgery described in all included studies consisted of excisional surgery to remove the pilonidal sinus tissue, and all wounds were left open to heal by secondary intention. Six studies used intraoperative injection of methylene blue into the sinus to aid recognition of tracts. Eight included studies described a limit to the depth of their surgical resection, with two studies specifying an excision down to bone if required, whilst the other six reported excision to the level of the presacral fascia. The wounds in one study were marsupialised, whilst in the other 10 studies no intervention to the wound margins was described. Seven studies reported follow‐up until wounds in all participants had healed, whilst four studies provided follow‐up to a designated time point, ranging from 60 days to 6 months.

Interventions

Two studies (Banasiewicz 2013; Biter 2014) compared topical negative pressure wound therapy dressings with other dressings, whilst the remaining nine studies compared different passive dressings. Intervention dressings included a topical zinc oxide mesh, a polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing, Lietofix cream, platelet‐rich plasma, a hydrogel dressing, Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge, a dialkylcarbamoyl chloride‐coated dressing and a hydrocolloid dressing.

Comparators

The comparators used in the included studies were wide‐ranging, with one study leaving the wound open with no dressing, whilst the other 10 studies used a comparator dressing or topical agent. One of these 10 studies used "wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine", and the other nine described the comparator dressings as "conventional absorbent dressing", "silicone dressing", "placebo mesh", "iodoform dressing", "absorbent sterile cotton gauze", "alginate dressing" and "iodine dressing".

Excluded studies

We excluded five studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Cherkasov 2016 was a non‐randomised study. Panahi 2015 studied chronic wounds but did not include any sacrococcygeal pilonidal wounds. Rao 2010 was an RCT, but it compared wounds closed primarily with those left to heal by secondary intention, rather than comparing dressings or topical agents. Yetim 2010 was an RCT comparing different techniques for primary closure of sacrococcygeal pilonidal wounds. Sadati 2019 was an RCT comparing dressings used in the open healing of sacrococcygeal pilonidal wounds; however, the use of different co‐interventions in two of the study treatment arms invalidated between‐group comparisons (the treatment regimen in one group consisted of a combination of a hydrogel and hydrocolloid, switching to an alginate and hydrocolloid from the second week after surgery, whilst another group used a combination of a hydrogel and a vaseline gauze and the third group underwent daily wound cleaning and packing with sterile gauze).

We did not identify any ongoing studies or studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in the included studies is displayed in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

We judged five studies to be at low risk of bias for random sequence generation as they used computer‐generated randomisation (Agren 2005; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Mohammadi 2017; Romain 2020). However, the other six studies did not provide sufficient information to judge their risk of bias and so we considered them to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain (Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Gohar 2020 Kayaoglu 2006; Ozbalci 2014; Viciano 2000). For allocation concealment, seven studies provided insufficient information and we therefore judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Ozbalci 2014; Viciano 2000). Three studies used a random permuted block allocation, with the recruiting investigators blinded to the centralised allocation, so we judged them to be at low risk of bias (Agren 2005; Mohammadi 2017; Romain 2020). We judged one study to be at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment because the recruiting investigators received the whole randomisation list by email (Giannini 2019).

Blinding

We considered that only one study was at low risk of both performance bias and detection bias, as the placebo mesh it used was indistinguishable from the intervention mesh, and outcome assessment was performed by blinded investigators (Agren 2005). The remaining 10 studies were all judged to be at high risk of performance bias because the treatment regimens between intervention and control groups varied substantially, and no attempt was made to blind participants (Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Mohammadi 2017; Ozbalci 2014; Romain 2020; Viciano 2000). We judged two studies to be at low risk of detection bias (Agren 2005; Giannini 2019), as both described outcome assessment by a blinded investigator. We judged one study to be at unclear risk of detection bias because it failed to clarify whether the investigators had been blinded to outcome assessment or only to treatment allocation (Mohammadi 2017). We judged the remaining eight studies to be at high risk of detection bias as there was no blinding of outcome assessment (Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Ozbalci 2014; Romain 2020; Viciano 2000).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged one study to be at unclear risk of attrition bias because the information it provided regarding study dropouts was insufficient to make a judgement (Viciano 2000). We considered six studies to be at low risk of bias in this domain, as they either had a very low dropout rate or had complete outcome data (Agren 2005; Banasiewicz 2013; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Mohammadi 2017; Ozbalci 2014). We judged four studies to be at high risk of bias as they had dropout rates exceeding 10% (Berry 1996; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Romain 2020). We considered 10% to be an acceptable cutoff point as dropouts were likely to be related to negative study events (e.g. admission to hospital with a wound complication).

Selective reporting

We judged nine studies to be at unclear risk of bias as we were unable to identify either a prospective trial registration or a protocol (Banasiewicz 2013; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Ozbalci 2014; Romain 2020; Viciano 2000). One study had a prospective trial registration and so was judged to be at low risk of reporting bias (Agren 2005). Another study was considered to be at high risk of bias because the publication and the prospective trial registration mentioned different primary outcomes (Mohammadi 2017).

Other potential sources of bias

One study provided insufficient descriptions of the methodology and participants to judge the risk of bias due to other factors, so we judged it to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain (Viciano 2000). We judged five studies to be at low risk of bias due to other factors as they had groups with similar baseline characteristics and declared no industry funding (Banasiewicz 2013; Gohar 2020; Kayaoglu 2006; Mohammadi 2017; Romain 2020). We judged five studies to be at high risk of bias in this domain because of several imbalances in baseline characteristics between the study groups (Agren 2005; Berry 1996; Biter 2014; Giannini 2019; Ozbalci 2014).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7

Summary of findings 1. Topical negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional open wound healing.

| Topical negative pressure wound therapy compared with conventional open wound healing for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: topical negative pressure wound therapy Comparison: conventional open wound healing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Risk with conventional open wound healing | Risk with topical negative pressure wound therapy | |||||

| Time to wound healing (days) | Mean time to wound healing was 59.11 days | Mean time to wound healing was 35.10 days | MD −24.01 (−35.65 to −12.37) days | 19 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | Unpublished data. One other study (49 participants) reported no difference in median time to wound healing (84 days vs 93 days, P = 0.44). |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days | 111 per 1000 |

289 per 1000 (57 fewer to 2838 more) |

RR 3.60 (0.49 to 26.54) |

19 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb | Unpublished data |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A | |||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

| Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) | 0 | 0 | Not estimable | 68 (2 studies) | Not estimable | No adverse effects were reported in either study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level), imprecision (1 level) and inconsistency (1 level). bDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels).

Summary of findings 2. Zinc oxide mesh versus placebo mesh.

| Zinc oxide mesh compared with placebo mesh for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: zinc oxide mesh Comparison: placebo mesh | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo mesh | Zinc oxide mesh | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

Median time for complete wound healing was 54 (interquartile range 42‐71) days in the zinc oxide mesh group and 62 (interquartile range 55‐82) days in the placebo mesh group; P = 0.32 |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Zinc oxide mesh may make little or no difference to time to wound healing. The certainty of evidence is low. | |||

|

Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days |

65 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (32 to 730) | RR 2.35 (0.49 to 11.23) | 64 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb | It is unclear whether Zinc oxide has an effect on the proportion of wounds healed at 30 days. The certainty of the evidence is very low. |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

|

Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) |

N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

| Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) | 0 | 0 | Not estimable | 64 (1 study) | Not estimable | No adverse effects were reported in the study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 2 levels to low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (1 level) bDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels).

Summary of findings 3. Lietofix cream versus iodoform dressing.

| Lietofix cream compared with iodoform dressing for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: Lietofix cream Comparison: iodoform dressing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Iodoform dressing | Lietofix cream | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

N/A |

Outcome not reported | ||||

|

Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days |

12 per 1000 | 97 per 1000 (13 to 740) | RR 8.06 (1.05 to 61.68) | 205 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Lietofix cream may increase the proportion of wounds healed at 30 days. The certainty of the evidence is low. |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

| Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) | 0 | 0 | Not estimable | 205 (1 study) | Not estimable | No adverse effects were reported in the study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 2 levels to low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (1 level).

Summary of findings 4. Hydrogel dressing versus wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine.

| Hydrogel dressing compared with wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: hydrogel dressing Comparison: wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine | Hydrogel dressing | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

Mean time to wound healing was 64.73 days | Mean time to wound healing was 40.19 days | MD −24.54 (−47.72 to −1.36) days | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa | The certainty of the evidence is very low. |

|

Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days |

N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

|

Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) |

63 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (14 to 1000) | RR 2.13 (0.22 to 21.17) | 31 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb | 3 surgical site infections reported in study. Data is for surgical site infection only |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 3 levels to low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels). bDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels).

Summary of findings 5. Platelet‐rich plasma gel versus absorbent sterile cotton gauze.

| Platelet‐rich plasma gel compared with absorbent sterile cotton gauze for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: platelet‐rich plasma gel Comparison: absorbent sterile cotton gauze | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Absorbent sterile cotton gauze | Platelet‐rich plasma gel | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

Mean time to wound healing was 59 days | Mean time to wound healing was 39 days | MD −19.63 (34.69 to 4.57) days | 210 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

Platelet‐rich plasma may reduce the time to wound healing. The certainty of the evidence is low. |

|

Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days |

N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

|

Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) |

0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 2 levels to low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (1 level)

Summary of findings 6. Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge versus no dressing.

| Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge compared with no dressing for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge Comparison: no dressing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No dressing | Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

Mean time to wound healing was 29.6 days | Mean time to wound healing was 28.2 days | MD −1.40 (−5.05 to 2.25) days | 50 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylow | Gentamicin‐impregnated collagen sponge may have little to no effect on time to wound healing. The certainty of the evidence is very low. |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

|

Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) |

0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels).

Summary of findings 7. Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC)‐coated dressing versus alginate dressing.

| Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC)‐coated dressing compared with alginate dressing for open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with open wounds after surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease Settings: secondary care Intervention: dialkylcarbamoyl chloride‐coated dressing Comparison: alginate dressing | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Alginate dressing | DACC‐coated dressing | |||||

|

Time to wound healing (days) |

Median time for complete wound healing was 69 (95% CI 62 to 72) days in the DACC group and 71 (95% CI 69 to 85) days in the alginate group. | 246 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | DACC‐coated dressings may make little or no difference to time to wound healing. The certainty of evidence is low. | ||

|

Proportion of wounds healed at 25 days |

17 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (1 to 94) | RR 0.51 (0.05 to 5.53) | 246 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | Data not reported at 30 days, but was available at 25 days |

| Proportion of wounds healed at 6 months | N/A |

|||||

| Proportion of wounds healed at 12 months | N/A |

|||||

| Cost‐effectiveness (assessed using quality‐adjusted life years) | N/A |

|||||

| Pain at first postoperative dressing change (measured using a validated scale such as a visual analogue scale) | N/A |

|||||

|

Adverse effects (surgical site infection or allergic reaction) |

0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded 2 levels to low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (1 level). bDowngraded 3 levels to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (1 level) and imprecision (2 levels).

We describe below the results of our comparisons between various dressings and topical agents. Unfortunately, we were unable to carry out either of our pre‐specified sensitivity or subgroup analyses due to the small number of studies for every comparison.

Comparison 1. Topical negative pressure wound therapy (TNPWT) versus conventional open wound healing (2 RCTs, 68 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing (68 participants)

It is unclear whether TNPWT reduces the time to wound healing compared with conventional open wound healing. Two studies evaluated the use of TNPWT therapy compared with conventional open wound healing (Banasiewicz 2013, Biter 2014); however, one of them did not report this outcome in their publication (Banasiewicz 2013), and the other reported this data narratively (as medians). The authors of Banasiewicz 2013 provided their data upon request, and we found that the two studies provided conflicting results: Banasiewicz 2013 observed a reduction in time to wound healing (MD −24.01 days, 95% CI −35.65 to −12.37; Analysis 1.1), whilst Biter 2014 reported no difference in time to wound healing (median 84 versus 93 days; P = 0.44). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level), imprecision (one level) and inconsistency (one level).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Topical negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional open wound healing therapy, Outcome 1: Time to wound healing (days)

Proportion of wounds healed (19 participants)

This outcome was not reported in either study, but the authors of Banasiewicz 2013 provided the relevant data upon request. It is unclear whether TNPWT affects the proportion of wounds healed at 30 days compared with conventional open wound healing (RR 3.60, 95% CI 0.49 to 26.54; Analysis 1.2). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (two levels). The authors of Banasiewicz 2013 informed us that all wounds in both groups were healed at 6 months and at 12 months.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Topical negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional open wound healing therapy, Outcome 2: Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days

Secondary outcomes

Recurrence rate (49 participants)

One study reported this outcome as the number of participants who had recurrent disease at six months (Biter 2014). It is unclear whether TNPWT affects the recurrence rate following wound healing compared with open wound healing (RR 3.13, 95% CI 0.35 to 28.00; Analysis 1.4). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (two levels).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Topical negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional open wound healing therapy, Outcome 4: Recurrence

Time to return to normal daily activities (68 participants)

It is unclear whether TNPWT has any effect on the time to return to normal daily activities. Two studies reported this outcome (Banasiewicz 2013; Biter 2014); however, the results of Biter 2014 are presented in a narrative synthesis with medians. The two studies provide conflicting results: Banasiewicz 2013 observed a reduction in time to return to normal daily activities (MD −8.60 days, 95% CI −13.40 to −3.80; Analysis 1.3), whilst Biter 2014 showed no difference in the median time to return to normal daily activities (27 days in the TNPWT group versus 29 days in the conventional open wound healing group; P = 0.92). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level), imprecision (one level) and inconsistency (one level).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Topical negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional open wound healing therapy, Outcome 3: Time to return to normal activities (days)

Neither study reported data for quality of life, cost‐effectiveness, pain during the first dressing change or adverse effects.

Comparison 2. Zinc oxide mesh versus placebo mesh (1 RCT, 64 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing (64 participants)

Zinc oxide mesh may make little or no difference to the time to wound healing. The one included study reported this outcome (Agren 2005), however only as median values (median 54 days in the zinc oxide mesh group versus 62 days in the placebo mesh group; P = 0.32). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (one level).

Proportion of wounds healed (64 participants)

It is unclear whether zinc oxide mesh improves the proportion of wounds healed at 30 days. This outcome was reported in the included study (Agren 2005), but only data at 30 days postoperatively were provided. The single study's small sample size led to imprecision in the effect estimate (5/33 in the zinc oxide mesh group versus 2/31 in the placebo mesh group; RR 2.35, 95% CI 0.49 to 11.23; Analysis 2.1). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (two levels). No data were reported for the six‐month or one‐year time points.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Zinc oxide mesh versus placebo mesh, Outcome 1: Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days

Secondary outcomes

The study did not report data for any of our secondary outcomes.

Comparison 3. Allevyn polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing versus Kaltostat alginate dressing (1 RCT, 20 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing (20 participants)

It is unclear whether polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressings reduce the time to wound healing. One included study reported this outcome (Berry 1996), but with ranges as a measure of variance, and no hypothesis testing. Mean time to wound healing was 57 days in the polyurethane foam hydrophilic dressing group compared with 66 days in the alginate dressing group. We were unable to calculate a mean difference with 95% CI for this comparison owing to the lack of any acceptable measure of variance. Standard deviations could not be imputed as there were no comparable studies. We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to imprecision (two levels: no acceptable measure of variance) and concerns over risk of bias (one level).

Proportion of wounds healed

This outcome was not reported in the included study.

Secondary outcomes

The study did not report data for any of our secondary outcomes.

In view of the paucity of relevant data, we have not produced a summary of findings table for this comparison.

Comparison 4. Lietofix cream versus iodine dressing (1 RCT, 205 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing

The one included study did not report this outcome (Giannini 2019).

Proportion of wounds healed (205 participants)

Lietofix cream may increase the number of wounds healed at 30 days compared with iodoform dressings. The included study reported the proportion of wounds healed at 30 days postoperatively (10/103 participants versus 1/83 participants; RR 8.06, 95% CI 1.05 to 61.68; Analysis 3.1). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (one level). No data were reported for the six‐month or one‐year time points.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Lietofix cream versus iodoform dressing, Outcome 1: Proportion of wounds healed at 30 days

Secondary outcomes

The study did not report data for any of our secondary outcomes.

Comparison 5. Hydrogel versus wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine (1 RCT, 31 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing (31 participants)

It is unclear whether hydrogel dressings reduce the time to wound healing compared with wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine. One included study reported this outcome (Kayaoglu 2006), with a mean difference of −24.54 days (95% CI −47.72 to −1.36; Analysis 4.1). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (two levels).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Hydrogel dressing versus wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine, Outcome 1: Time to wound healing

Proportion of wounds healed

This outcome was not reported in the included study.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse effects (31 participants)

Surgical site infections were reported in the included study. It is unclear whether hydrogel dressings have any effect on surgical site infection (RR 2.13, 95% CI 0.22 to 21.17; Analysis 4.2). We downgraded the certainty of evidence to very low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (two levels).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Hydrogel dressing versus wound cleaning with 10% povidone iodine, Outcome 2: Surgical site infection

The study did not report data for recurrence rate, time to return to normal daily activities, quality of life, cost‐effectiveness or pain during the first dressing change.

Comparison 6. Platelet‐rich plasma gel versus absorbent sterile cotton gauze (2 RCTs, 210 participants)

Primary outcomes

Time to wound healing (210 participants)

Platelet‐rich plasma may reduce the time to wound healing compared with absorbent sterile cotton gauze. Both Gohar 2020 and Mohammadi 2017 reported this outcome (MD −19.63 days, 95% CI −34.69 to −4.57; Analysis 5.1). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to low due to concerns over risk of bias (one level) and imprecision (one level).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Platelet‐rich plasma versus absorbent sterile cotton gauze, Outcome 1: Time to wound healing (days)

Proportion of wounds healed

This outcome was not reported in either of the included studies.

Secondary outcomes

Time to return to normal daily activities (210 participants)