INTRODUCTION

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHCA, 2017)[1] has been recently enacted with the objectives of providing mental health services and securing of rights of persons with mental illness (PMI).[2] Recently conducted National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) quoted prevalence of 13.7% lifetime and 10.6% current mental morbidity.[3] This psychiatric epidemiological report is consistent with earlier reports from India.[4] Further, NMHS reported that the treatment gap for common mental disorders (85.0%) was higher compared to that for severe mental disorders (73.6%).[3] As a large proportion of population in India is affected by mental disorders, there is an urgent need to have systems put in place that can facilitate better diagnosis and management of mental disorders across the country.[5] To address this mammoth problem, the Government of India started to make efforts to improve the mental health services in the form of formulating the National Mental Health Policy, 2014, and MHCA, 2017.[6] The act is progressive and rights-based.[7] MHCA, 2017 is heavily influenced by the Western model of legislation. It is based on individual rights, is patient-centric, and gives the individual total autonomy over them, which comes in the way of the treatment unless the patient gives informed consent. On a closer look, this act is premised on a hypothesis that the mental healthcare providers and family members are the main violators of the rights of the PMI, which is unfortunate.[7]

This rights-based legislation has changed the equation of providing services under the rights-based mental healthcare services framework. This new legislation has impacted the setting up of new mental health establishment (MHE) and providing mental healthcare services in India. The annual health expenditure of India is 1.15% of the gross domestic product, and the mental health budget is <1% of India’s total health budget.[8] Adding to the chaos, the availability of the trained mental health workforce is very sparse and nonexistent in certain parts of the country.[9,10] The ground realities are far from adequate with regard to economic readiness, human resources, and willpower to implement this rights-based legislation.[7] Unlike the other patients, PMI such as paranoid delusions, personality disorders, substance use disorder, and mania brings its unique challenges, from litigation, with-holding of consent, possible risks of violence to self or others, and absconding from MHE. Such clients are likely to complain against psychiatrists as a consequence of their mental health conditions, resulting in a cascade of legal proceedings. The psychiatrists are worried about the legal consequences, complications, compensations, and complexities of providing rights-based mental healthcare services. In this background, this article aims at providing a framework for mental health professionals to organize mental healthcare services under the new legal framework and minimizing the conflict with the law.

STARTING A MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT

Any person can start an MHE, however, it is mandated that all MHE shall be registered under the MHCA, 2017. Registration of MHEs is done under Section-65 of the legislation. Registration can be made provisional or permanent registration depending upon the notification of minimum standards of MHEs by the respective mental health authorities. Any person wishing to establish an MHE shall register the establishment in the respective state. As per every MHE shall, for registration should fulfill the minimum standards of facilities required, the minimum qualifications for the personnel engaged in such establishment, provisions for maintenance of records, and any other conditions as may be specified by regulations made by the Authority. Along with the above details, the person applying for registration shall give his/her details and submit the application to the respective Mental Health Authority in a prescribed format Form-B (See rules 11[2] and 12) of the Mental Healthcare (Central Mental Health Authority and Mental Health Review Boards) Rules, 2018,[1] Furthermore, make sure that your establishment fulfills the minimum standards prescribed by the respective Mental Health authorities under the Mental Health Regulations, such as adequate space for consulting rooms, examination rooms, provision for modified electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), adequate number of toilets, bathrooms and recreational place. Provisions for, kitchen, outpatient, solid waste management, room for Mental Health Review Board/legal aid clinic, visitors’ room, library, and appropriate treatment of sewage should be present. The inpatient (IP) facility should be safe, well ventilated, and well-lit at all times with easy accessibility. Separate accommodation for males, females, and children with a separate cot for the patient and the attendant is necessary. Emphasis on safety with adequate supervision, installing surveillance systems is needed but keeping in mind patient’s, need for privacy and dignity is the key. These are the few example provisions mentioned here for the sake of understanding.

Further, the MHE shall fulfill the norms prescribed under the Rights to Persons with Disability Act, 2016. This provision applies for all establishments, where persons with disability approach or access for services or amenities and it should be disability-friendly. The MHCA, 2017 also prescribes punishment/penalty running an establishment without registration under Section 107 (1), which shall not be less than five thousand rupees but which can be increased to 50,000 rupees for first contravention or a penalty which shall not be <50,000 rupees. However, this may extend to 200,000 rupees for a second contravention or a penalty which shall not be <200,000 rupees but which may extend to 500,000 rupees for every subsequent contravention.

Although there are few additional license and registration are essential to be acquired, not under the MHCA, 2017. These registration and license are worth mentioning here. They are based on various parameters such as the number of beds, number of employees, and number of floors of the building, such as a pollution control board license, fire department no objection certificate, registration under the clinical establishment act, and no objection certificate from adjoining property owners as mandatory for starting an MHE. Other miscellaneous licenses include pharmacy license, schedule X license under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1945 (amended), schedule H license, and approval of recognized medical institutions to stock and dispense narcotic drugs under the NDPS Act, 1985.[11,12] The in-charge of the MHE needs to apply for lift license, generator use and maintenance permission, canteen license, employee state insurance if more than ten employees, and provident fund registration, form the few other necessary procedures.

WORKING IN A MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT

If you are planning to work in any clinical establishment to provide mental healthcare services, please ensure that the clinical establishment is registered under the MHCA, 2017. If the clinical establishment provides exclusively outpatient (OP) services, there is no need for registration under the MHCA, 2017.

It is very essential to note the wordings drafted under the law is very clear under MHCA, 2017s 107 (2) Whoever knowingly serves in the capacity as a mental health professional in an MHE which is not registered under this act, shall be liable to a penalty which may extend to 25,000 rupees. It is advisable for every psychiatrist to make sure that the clinical establishment is registered under this law, if the establishment is providing inpatient services. Avoid providing any kind of mental healthcare services, including telepsychiatry services in an unregistered IP MHE services such as rehabilitation centers, addiction medicine centers, mental hospitals, and so forth. Any IP rehabilitation services such as (i) quarter way home, (ii) residential halfway home, (iii) long stay home, and (iv) de-addiction[11] shall register under the MHCA, 2017 and does not require to be registered under the Section 50 of the Right to persons with disability Act, 2016. As a rule of thumb, psychiatrists shall keep in mind that any places making supported admission shall be registered.

ADMISSION OF PERSONS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

Article 21, Right to life and liberty lays down that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to “procedure established by law.” Hence, in any institution where the right to life and liberty is violated, this amounts to a violation of the fundamental rights of a citizen ensured under the constitution of India. However, the right to life and liberty can be curtailed if there is a “procedure established by law.”[13]

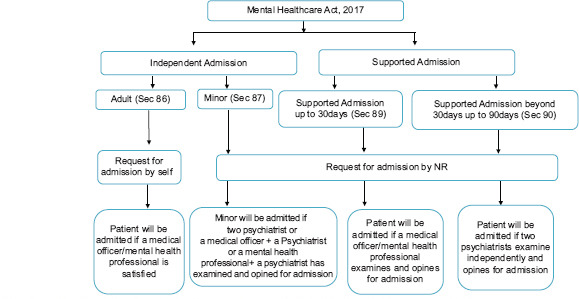

MHCA, 2017 is an established law under which the liberty of a person with mental illness can be restricted if they fulfill the requirement of the law. The key is to fully understand the laws regarding the supported (involuntary) admission for psychiatric evaluation, who is authorized to detain? How long? Does the facility have the registration to detain? Are there any checks and balances in the form of an unbiased redressal mechanism? Hence, all admissions to the MHE should comply with the MHCA, 2017 [Flow Chart 1]. All admissions to MHE need to follow certain important steps as follows:

Flow Chart 1.

Depicting the admission procedure under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017

a. All admission to MHE shall occur under specific sections of this legislation

b. Application for admission by PMI or NR or by an authorized person under the legislation

c. Assessment and certification by authorized personal regarding the requirement for admission and treatment

d. Admission under specific section should fulfill the criteria mentioned in that respective section

e. Documentation and Intimation of all admission to the concerned board

-

f. All mental health professionals should ensure:

- Documentation regarding the admission procedure

- Least restrictive environment

- Consent for treatment as mentioned in the respective section

- Capacity assessment

- Discharge of the patient shall be subject to patient improvement/gaining of capacity and/or request for discharge or as per MHRB orders or NR’s request.

All supported admission occurs initially under Section 89. However, if the patient needs continued care in MHE and still lacks the capacity on assessment, the treating team needs to ascertain the applicability of Section 90 provisions, obtain suitable application forms, have assessments by two independent psychiatrists and then continue or readmit PMI under section 90 for up to 90 days. MHRB has to be intimated of such admissions within 21 days for approvals. Provisions have been made for further extensions or renewal of permission for a subsequent IP stay up to 180 days in total with appropriate approvals from the concerned board. Discharge Planning has to be made as a mandated procedure for all admissions made at the MHE. It should include the explanation of possible side-effects, red-flag signs, future follow-ups and plans, discussion regarding the nomination of an NR if not nominated, and forming an AD. In case of any conflict with the patient or NR/patient’s family member please do not hesitate to contact MHRB for guidance. Tables 1 and 2 shows the admission procedure under the MHCA, 2017.

Table 1.

Depicts the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 sections, various types of admission, application, authorized personnel and number of days

| Section | Type of admission | Application for admission | Authorized personnel for admission | Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86 | Independent admission | Person with mental illness | Medical officer or mental health professional | No time limit |

| 87 | Minor admission | NR | Two psychiatrists, or one psychiatrist and one mental health professional or one psychiatrist and one medical practitioner | No time limit |

| 89 | Admission and treatment of PMI, with high support needs, in mental health establishment, up to 30 days | NR | 30 days | |

| 90 | Admission and treatment of PMI, with high support needs, in mental health establishment, beyond 30 days | NR | Two psychiatrists | 90 days. If requires IP care beyond 90 days, for the 1st Time-120 days but if the persons require continuation 180 days |

| 100 | Duties of police officers in respect of PMI | Police officer | The medical officer or mental health professional in-charge of the public mental health establishment | As per the section 86, 87, 89 and 90 |

| 102 | Conveying or admitting person with mental illness to mental health establishment by magistrate | Magistrate | Only 10 days admission as per the magistrate order | As per the section 86, 87, 89 and 90 |

| 103 | Prisoners with mental illness | The Prisoners Act, 1900 or the Air Force Act, 1950, or the Army Act, 1950, or the Navy Act, 1957, or under section 330 or section 335 of the CrPC 1973 | Permission of the mental health review board | No time limit mentioned in the act |

| All admission under section 87 and 89 of minor and women will be informed to the concerned board within 3 days and within 7 days the admission of any person not being a woman or minor. All admissions or readmission under section 90, will be informed to the concerned Board within 7 days | ||||

NR – Nominated representative; PMI – Persons with mental illness; IP – Inpatient

Table 2.

Depicts the different forms to be filled by specific stakeholders for various purposes as per the mental healthcare (rights of persons with mental illness) Rules, 2018

| Serial number | Request to be made by | Purpose of request | Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Person with mental illness | Basic medical records | Form A |

| 2 | Issuing of basic medical records by the treating psychiatrist within 15 days. There are three different formats for different services such as (1) OP services, (2) IP services, (3) Psychological assessments reports and (4) Therapy reports | Form B | |

| 3 | Any person who is not a minor and who considers himself to have a mental illness admission | As an independent patient | Form C |

| 4 | NR of the minor | Admission of the minor | Form D |

| 5 | NR of a person | Admission of a person with mental illness, with high support needs under section 89 of the act | Form E |

| 6 | NR of a person | Continuation of the admission of a person with mental illness, with high support needs under section 90 of the act | Form F |

| 7 | Person admitted as an independent patient or a minor admitted under section 87 of the act who attained the age of 18 years during his stay in the mental health establishment | discharge from a mental health establishment | Form G |

| 8 | NR of the minor | Discharge of the minor | Form H |

| 9 | NR of the person with mental illness admitted in a mental health establishment | Grant of leave to such person | Form I |

| 10 | Psychiatrist in charge of such mental health establishment | Request for taking into protection by a police officer of a prisoner with mental illness found to be absent from a mental health establishment without leave or discharge | Form J |

NR – Nominated representative; OP – Outpatient; IP – Inpatient

Admission of homeless wandering PMI shall be under Section 100 through police. If a person with mental illness and is being illtreated or neglected shall report the fact to the magistrate within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the person with mental illness resides and produced in public MHE. It is essential to note that all admissions under section 100 and 102 shall be to the public MHE.

UNAUTHORIZED ABSENCES FROM MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT

There are certain situations, person with mental illness admitted under any section of MHCA, 2017 can abscond from the MHE because of various reasons, including illness per section MHCA, 2017 clearly dictates to utilize Form J for informing to police about unauthorized absences of prisoners with mental illness admitted under section 103 from MHE but silent about the admission of PMI under other sections.

A study from Gowda et al. 2019,[14] done from NIMHANS, reported that the absconded patients were males; admitted involuntarily; diagnosed with either schizophrenia, mood disorder, and had comorbid substance use disorder; and lacked insight and had high perceived coercion. Absconding patients had the tendency to harm themselves and wanderaway from home. This study clearly indicates that need to inform police in Form No-K, to protect the person with mental illness admitted under any sections of the act. In the eventuality of the escape of aperson with mental illness PMI from the establishment, the medical officer-in-charge will make arrangements immediately to inform the contact Nominated Representative (NR). In the absence of NR or family members, the medical officer-in-charge may consider informing the police about the escape.

RIGHTS OF THE PERSONS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS AND MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT INSTITUTIONAL POLICIES

The preamble of MHCA, 2017 promises to provide mental healthcare and services for PMI and to protect, promote, and fulfill the rights of such persons during the delivery of mental healthcare and services. The act is progressive, patient-centric, and rights-based.[15] Chapter 5 on “Rights of the PMI” is the heart and soul of this legislation. MHCA, 2017 has enumerated the Rights of PMI from Section 18-28.[1]

No person shall violate the rights enumerated under this legislation such as the right to community living; right to live with dignity; protection from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment; treatment equal to persons with physical illness; right to relevant information concerning treatment, other rights and recourses; right to confidentiality; right to access their basic medical records; right to personal contacts and communication; right to legal aid; and recourse against deficiencies in the provision of care, treatment, and services.[1] MHEs can make institutional policies without violating the enumerated rights under the MHCA, 2017, rules and regulations. Institutional policies can include timings of admission, fees, a patient visiting timing, dietary protocol, restriction of smoking/alcohol use in the premises, restriction of phone usage in sensitive areas like Intensive Care Unit, or any protocols necessary for the safety of PMI and staff working there.

CAPACITY TO CONSENT FOR ADMISSION AND TREATMENT

Mental capacity refers to the ability of an individual to make one’s own decisions. Decision-making capacity has been described as the “key to autonomy” and an important ingredient of informed consent. Limited or impaired mental capacity embarks on a minefield of ethical and legal issues, which a psychiatrist needs to be aware of while dealing with a particular patient.[16] Adding to this mental capacity is not static, but dynamic in nature. People may have a condition or illness that affects their ability to make decisions. A lack of capacity may be temporary, such as that caused by some illnesses or the influence of drugs or alcohol or mood/affective state. The capacity of a person’s may vary over time, depending on the condition or illness that the person experiences. A person is presumed to have the capacity to make a decision unless there are good reasons to doubt this presumption. In general, capacity is assessed with respect to a specific decision at a specific time. A person is entitled in law to make unwise or imprudent decisions, provided they have the capacity to make the decision. Supported decision-making involves doing everything possible to maximize the opportunity for a person to make a decision for themselves. As per the MHCA, 2017 all PMI shall have capacity to make mental healthcare or treatment decisions but may require varying levels of support from their NR to make decisions. A person’s capacity should be assessed in relation to a particular task or decision. Capacity cannot generally be inferred from one task or decision to another. The person’s incapacity may be temporary, or fluctuating. If possible, an assessment of capacity should be done when the person’s condition has improved. For example, if the person has delirium, it is better to wait until this has resolved. In such patients with Delirium, Severe Manic Excitement, Stupor, Alcohol and other substance use intoxication, Capacity Assessment may not be feasible, and they can be deemed to have “Obvious” lack of capacity and may be recorded as such. Finally, the capacity assessment is based on the combination of relevant history, symptoms, behavior observation, mental status examination, and diagnosis. It is a clinical judgment of a clinician.

As per MHCA, 2017 section 81., (1) the central authority shall appoint an expert committee to prepare a guidance document for medical practitioners and mental health professionals, containing procedures for assessing, when necessary or the capacity of persons to make mental health care or treatment decisions. This guidance document (2) will be used by every medical practitioner and mental health professional to assess capacity of a person to make mental healthcare or treatment decisions.

This guidance document is only a guidance document and does not replace legal advice. This document is not a structured or checklist instrument and only a guidance document with provision for semi-structured assessment and documenting the capacity assessment findings. The final decision of capacity is based on holistic assessment of behavioral observation, clinical findings, mental status examination, diagnosis and capacity assessment as per the guidance document. Further it is the prerogative and the duty of the mental health professional/clinician to record the clinical findings in details and/or elaboration of the same.

There are many procedures including supported admission and treatment shall be done either with the consent of the patient or follow the advance directive or seek consent from NR. The legislation mandates to seek consent as follows in the hierarchy presented below:

i. The PMI for any procedure

ii. Follow the advance directives

iii. NR’s consent (NR shall exercise supported/shared decision-making).

A person who is capable of deciding on his health care must have that decision respected by the treatment provider. To proceed against the person’s wishes would amount to the deprivation of liberty, liable for tort, and in some cases, criminal assault. Besides, if consent is obtained from an incompetent patient is usually considered invalid by the law, in such a situation’s physicians may be subject to claims of having treated the person without informed consent.[16] Hence, it is always prudent to assess the mental capacity of the person, follow advance directives when required and seek consent from NR as per the MHCA, 2017. The guidance document needs to be used for assessment and Table 3 depicts the situation where Capacity Assessment to be done.

Table 3.

Capacity to make mental healthcare and treatment decisions assessment to be carried out on any person (above 18 years of age) during the following situations

| Situation | Section |

|---|---|

| The registration of advance directives | Section 11 (2) D |

| Before invoking the advance directive | Section 5 (3) |

| Independent admission | Section 86 (2) C |

| Supported admission up to 30 days | Section 89 (1) C |

| Every week, when admitted | Section 89 (8) |

| Supported admission beyond 30 days | Section 90 (12) |

| Every fortnightly, when admitted | Section 90 (13) |

| Before giving any information of the person to the NR (information will be given to NR only if the PMI do not have capacity) | Section 22 |

| For treatment-related decisions (other than admission) | Section 4 |

NR – Nominated representative; PMI – Persons with mental illness

As per the MHA, 2017, all PMI shall have the capacity to make mental healthcare or treatment decisions but may require varying levels of support from their NRs to make decisions.[17] A person’s capacity should be assessed concerning a particular task or decision. Capacity cannot generally be inferred from one task or decision to another. The guidance document is drafted and notified as per Section 81 of the MHA, 2017. An expert committee was set up to prepare a guidance document containing procedures for assessing the capacity of persons to make mental health care or treatment decisions. Further, Section 81 (2) depicts that every medical practitioner and mental health professional shall, while assessing the capacity of a person to make mental healthcare or treatment decisions, comply with the guidance document.

RIGHT TO ACCESS BASIC MEDICAL RECORDS

Every person with mental illness has the right to access his basic medical records of both OP and IP. Hence, there is an obligation to document and maintain records of OP department (OPD) and IP from the date of the first consultation till a period of at least three years from the last date of consultation, is needed. If any request is made for medical records by PMI in a prescribed format, the same is duly acknowledged and documents issued within 2 weeks.[18]

As per MHCA, 2017, any person with mental illness may apply for a copy of his basic IP medical record by requesting in writing in Form-A, addressed to the medical officer in charge of the concerned MHE. Within 15 days from the date of receipt of the request under sub-rule (2), basic IP medical records shall be provided to the applicant in Form-B of the Mental Healthcare (Rights of PMI) Rules, 2018. See Table 2 for various forms to be filled.

It is advisable psychiatrists should maintain a register of medical certificates giving full details of certificates issued, including identification marks or UHID or hospital numbers of the patient, and a copy of the certificate ought to be maintained for hospital records. Further, registers to be maintained include OP attendance register, IP admissions register, census register, treatment adverse effect monitoring record, certificate register, medico-legal register, escape register, restraint register, and mortality register.[18] Commonly the conflict between the person with mental illness and establishment occurs because of the access to basic medical records. In this regard, State Mental Health Rules 2018 has mandated the following documents to be maintained and provided on demand, such as basic OP record, IP record, psychological assessment record, and psychotherapy record. As shown in Table 2, various forms to be filled.

RIGHT TO CONFIDENTIALITY UNDER SECTION 23

All person with mental illness shall have the right to confidentiality in respect of his mental health, mental healthcare, treatment, and physical healthcare. All health professionals providing care or treatment to a person with mental illness shall have a duty to keep all such information confidential which has been obtained during care or treatment. However, exceptions have been placed for providing information to NR, other medical and mental health professionals to provide health care, release only such information if it is necessary to protect any other person from harm or violence or in the interests of public safety and security from the person with mental illness. The release of information upon order by concerned Board or the Central Authority or High Court or Supreme Court or any other statutory authority competent to do so. Further, under Section 24, NO photograph or any other information (physical and virtual/digital/electronic information) relating to a person with mental illness undergoing treatment at a MHE shall be released to the media without the consent of the person with mental illness. In any police investigation of cognizable offenses, the medical officer is responsible for providing information to the investigation officer after receiving a written request from the police and please do not hesitate to educate the police officer about the confidentiality issue. If the psychiatrist, has any doubt regarding providing information, please consider a) to procure consent from the concerned patient or b) contact MHRB for further directions to reveal or not.

EMERGENCY TREATMENT UNDER SECTION 94

Any medical treatment, including treatment for mental illness, may be provided by any registered medical practitioner to a person with mental illness either at a health establishment or in the community, subject to the informed consent of the NR, where the NR is available, and where it is immediately necessary to prevent:

a. Death or irreversible harm to the health of the person; or

b. The person inflicting serious harm to himself or to others; or

c. The person causing serious damage to property belonging to himself or to others where such behavior is believed to flow directly from the person’s mental illness.

This section also includes transportation of the person with mental illness to the nearest MHE for assessment. Emergency treatment is immediately necessary to prevent.

a. Death or irreversible harm to the health of the person

b. The person inflicting serious harm to self or to others

c. The person causing serious damage to property belonging to self or others where such behavior is believed to flow directly from the person’s mental illness.

Treatment can be administered only if the registered medical practitioner is available. In the absence of registered medical practitioner, arrangement can be considered for transferring the patient to the nearest MHE with or without the help of police. It is advisable to seek the help of police, if the patient is very violent and aggressive. The NR should give informed consent in the form of an application for ambulance services. The treatment under “emergency treatment” of the PMI’ shall be considered if registered medical practitioner is available onsite. Do not give any blanket order of injectables to the support personnel accompanying the ambulance in the absences of the registered medical practitioner. When the family members seek emergency services, they should be explained about the various provisions under the MHCA, 2017 to provide care and treatment to the patient. Avoid using telemedicine services under emergency treatment.

In an already diagnosed case of mental illness, the documents required include identification proof of the individual, proof of illness including the details of the patient if he was previously hospitalized or had sought emergency services, ongoing medications or previous prescriptions, details of other medical history, if there is the history of any substance use. In a fresh case of mental illness id proof of the individual and those of his accompanying family members will be needed. In both categories, the family members must be inquired if the person possesses any harmful weapons or tools in order to be prepared and ensure safety by arranging for police and other required extra protections. In any situation, the professional discretion of the psychiatrist needs to be considered to seek help from the police or not. If there are no adequate security personnel (police) and/or ambulance is not available, wait for the adequate security support is available. In any circumstances, the capacity assessment needs to be considered before taking any steps. If the person with mental illness has the capacity, please take consent from person with mental illness before proceeding.

Procedure to be followed to provide care under Section 94, following things needs to be considered (a) families will give an application in writing about the need for emergency treatment (Form-L) (b) make sure the accuracy of information and reliability of the history provided by the NR (c) family will take the responsibility for the damage caused to any of the team members, to any others or to any of the equipment during the process, (d) consent of the NR is required, wherever available, (e) physical restraint will be applied, whenever necessary only under the supervision of a psychiatrist only, which shall be documented and informed to MHRB as per the MHCA, 2017 requirement, (f) capacity assessment to be attempted in all section 94 treatment procedure and (g) required treatment can be administered under section 94 only in the presences of the registered medical practitioner. The medical officer in-charge health establishment will issue a letter to the police station officer of the jurisdiction for security purposes only in old cases (Form-M). In new cases, no such letter can be given without examining the patient. It will be the responsibility of the NR to get help from the police if required. The medical officer in charge of the establishment will be responsible for appropriate training of the personnel engaged in execution and providing care under section 94.

RESTRICTED, REGULATED AND PROHIBITED PROCEDURES

The psychiatrist should not indulge in prohibited procedures; ECT without muscle relaxants and anesthesia should not be done at any cost. ECT shall not be used for emergency treatment.[19] The above issues have been criticized for law trespassing to the clinical arena; however, now, it is the law of the land, psychiatrists shall abide by it. No person working in MHE shall order for seclusion or isolation or chaining of PMI in any manner.[20] MHCA is a rights-based, patient-centered mental health law. For many reasons, the act shall have a direct impact on the use of ECT in many ways and it deserves close attention.[20] Another important and welcoming step is the prohibition of sterilization of men or women when such sterilization is intended as a treatment for mental illness.

The psychiatrist shall seek prior permission from the board for certain procedures; ECT for minors shall be given with the consent of the guardian and prior approval by the concerned board.[21,22] Similarly, psychosurgery shall be undertaken only after the consent of the person with mental illness and permission from the concerned board. In this regard, a joint consensus guideline has been published in 2019 by The IPS, the Indian Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, and The Neuromodulation Society.[23] A consensus statement was devised based on available literature on neurosurgical procedures for psychiatric disorders. The available evidence supports the use of ablative surgery and deep brain stimulation as an experimental treatment for patients with chronic severe and highly treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, and Tourette syndrome. It is imperative to obtain informed consent from the patient after explaining the evidence and expected outcome following the procedure. The current Mental Health Act, 2017, further requires the approval of the mental health review board before performing surgery.[23] Before undertaking any research consent of the person with mental illness shall be procured. If person with mental illness does not has capacity to consent, all such research will be done with consent of the NR and permission from the concerned Authority. A copy of the protocol and informed consent will be sent to State Authority to get permission to carry out research.

The psychiatrist shall follow the procedure for restraint; MHCA, 2017 allows physical restraint may be used when it is the only means available to prevent imminent and immediate harm to persons concerned or to others. Restraint will be authorized by the psychiatrist and shall be informed to the concerned with the board every month. The method and nature of the justification for its imposition and duration of the restraints are to be immediately recorded in the medical notes of the patients by the treating team. Restraints shall not be used as punishment or deterrent in any circumstances and shall not be used merely on account of the shortage of staffs.

Restriction to discharge functions by professionals not covered by profession; At the same time, psychiatrist should know that Section 106 of the MHCA, 2017 places restrictions to discharge functions by professionals not covered by profession. Hence, the psychiatrist shall not discharge any duty or perform any function not authorized by this act or specify or recommend any medicine or treatment not authorized by the field of his profession.

There are certain situations such as, if a person with mental illness escapes from MHE or an attempted suicide versus attempted suicide is bought to the MHE for treatment or a person with mental illness under your treatment is found to have entered into conflict with the law, should it be informed to the police? In such scenarios, it would be prudent to seek an opinion immediately from a senior colleague or request for a legal opinion or seek help from MHRB members for guidance or register a medico-legal case or inform the police. Please do not assume things because each psychiatry case is potentially a medico-legal case.

PUNISHMENT FOR CONTRAVENTION OF PROVISIONS OF THE ACT OR RULES OR REGULATIONS

Failure to comply with any provisions of MHCA/violating any of the sections under the act/any complaints to MHRB with subsequent proof of guilt will incur heavy penalties ranging from Rs 10,000–50,000/-and again up to Rs. 5 Lakhs depending on the nature of the offense or repeatability of the offense (Section 107). It can also lead to imprisonment ranging from 6 months to two years. We are duty-bound to verify and offer services in registered MHE solely, except for services offered in OPD setting/treatment offered under Section 94.[24] However, any rights violation can be investigated by the concerned MHRB is irrespective of the treatment setting and establishment. In case of any doubt, please do not hesitate to contact MHRB for guidance.

INDEMNITY INSURANCE FOR PSYCHIATRIST

In India, along with MHCA, 2017, any medical practice has been brought under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019. Any deficiency in health services results in medical negligence and huge compensation to be paid to the client. The consumer can claim compensation for an untoward medical consequence in his place of residence, and the psychiatrist needs to travel to clients’ place to contest the case.[25] Hence, indemnity coverage for psychiatrists and health establishments becomes an essential requirement.[11] However, MHCA, 2017. Section 116 places “bar of jurisdiction”[1] by mandating that no civil court shall have jurisdiction to entertain any suit or proceeding in respect of any matter which the Authority or the Board is empowered by or under this Act todetermine, and no injunction shall be granted by any court or other authority in respect ofany action taken or to be taken in pursuance of any power conferred by or under this act.[1] Hope this clause may be blessing in disguise for psychiatrist.

PROOF OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS

All psychiatrists should be aware of Section 105 of MHCA, 2017. This clause dictates that if during any judicial process before any competent court, proof of mental illness is produced and is challenged by the other party, the court shall refer the same for further scrutiny to the concerned board and the board shall, after examination of the person alleged to have a mental illness either by itself or through a committee of experts, submit its opinion to the court.[1] This clause decreases the burden of proving or not proving the mental illness on the treating psychiatrist, and this clause should be utilized in inappropriate places for the benefit of the PMI.

TRAINING OF STAFFS OF MENTAL HEALTH ESTABLISHMENT IN MENTAL HEALTHCARE ACT, 2017

It is important to arrange workshops for MHE staff conducted by experts in law and mental health to learn various case scenarios and to comply better with the MHCA, 2017. No person working in MHE shall violate the rights of the PMI; hence, the training of staff becomes a high priority. Otherwise, MHE can be made to pay a heavy penalty under vicarious liability. MHE may consider having a legal advisory committee and help psychiatrist to make decisions in times of difficult scenarios to comply with the act. Learning from peers has been one of the best ways to enhance practice and regain confidence. In case of any doubt do not hesitate to take parallel opinion or request for the second opinion from colleagues or experts from the field.[26]

To conclude, MHCA, 2017 is a step in the right direction from the perspective of rights-based mental healthcare. Punishments prescribed in the act are too harsh, and there is no provision to assess whether a contravention is accidental, due to practical difficulties, or deliberate. Further, no psychiatrist should indulge in prohibited procedures at any cost. The psychiatrist should follow the MHCA, 2017 by documenting it, informing the MHRB, and respecting the rights of PMI. Unlike the other patients, the behavior and responses of the person with mental illness are different, and brings its unique challenges, from litigation, with-holding of consent, violation of rights, and possible risks of violence to self or others. Such clients are likely to complain against psychiatrists as a consequence of their mental health conditions, resulting in a cascade of legal proceedings. Such litigation-based mental healthcare can give rise to defensive practice and will increase the cost of mental health care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mental Healthcare Act. 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 18]. Available from:http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental%20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .

- 2.Mohan A, Math SB. Mental Healthcare Act 2017:Impact on addiction and addiction service. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S744–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_114_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh L, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16:Summary. Bengaluru:National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India:The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy RM, Kelly BD. India's Mental Healthcare Act, 2017:Content, context, controversy. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2019;62:169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Math SB, Basavaraju V, Harihara SN, Gowda GS, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, et al. Mental Healthcare Act 2017 –Aspiration to action. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S660–6. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_91_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, Hanna F, Jotheeswaran AT, Luo D, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet. 2016;388:3074–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namboodiri V, George S, Singh SP. The Mental Healthcare Act 2017 of India:A challenge and an opportunity. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;44:25–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Math SB, Gowda GS, Basavaraju V, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Enara A, et al. Cost estimation for the implementation of the Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S650–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_188_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowda MR, Das K, Gowda GS, Karthik KN, Srinivasa P, Muthalayapapa C. Founding and managing a mental health establishment under the Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S735–43. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_147_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Math SB, Mohan A, Kumar NC. Opioid substitution therapy:Legal challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:271–7. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_391_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Math SB, Murthy P, Chandrashekar CR. Mental health act (1987):Need for a paradigm shift from custodial to community care. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:246–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowda GS, Thamby A, Basavaraju V, Nataraja R, Kumar CN, Math SB. Prevalence and clinical and coercion characteristics of patients who abscond during inpatient care from psychiatric hospital. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:144–9. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_188_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy RM, Narayan CL, Goyal N, Kelly BD. New legislation, new frontiers:Indian psychiatrists'perspective of the Mental Healthcare Act 2017 prior to implementation. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:351–4. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_45_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Math SB, Moirangthem S, Krishna K, Reddi VSK. Capacity to consent in mental health care bill 2013:A critique. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;31:112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Namboodiri V. Capacity for mental healthcare decisions under the Mental Healthcare Act. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S676–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_76_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gajera G, Srinivasa P, Ameen S, Gowda M. Newer documentary practices as per Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S686–92. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_110_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar MT. Mental Healthcare Act 2017:Liberal in principles, let down in provisions. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40:101–7. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_23_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy RM, Gulati G, Paralikar V, Kasar N, Goyal N, Desousa A, et al. A focus group study of Indian psychiatrists'views on electroconvulsive therapy under India's mental healthcare act 2017:'The Ground Reality is Different'. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:507–15. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_247_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma E, Kommu JV. Mental Healthcare Act 2017, India:Child and adolescent perspectives. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S756–62. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_126_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grover S, Avasthi A, Gautam S. Inpatient care and use of electroconvulsive therapy in children and adolescents:Aligning with Mental Health Care Act, 2017. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:155–7. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_557_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doshi PK, Arumugham SS, Bhide A, Vaishya S, Desai A, Singh OP, et al. Indian guidelines on neurosurgical interventions in psychiatric disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:13–21. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_536_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hongally C, Sripad MN, Nadakuru R, Meenakshisundaram M, Jayaprakasan KP. Liabilities and penalties under Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S724–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_150_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomani M, Rahman F, Alhalboosi AK. Consumer Protection Act, 2019 and its implications for the medical profession and health care services in India. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2019;41:282–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harbishettar V, Enara A, Gowda M. Making the most of Mental Healthcare Act 2017:Practitioners'perspective. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S645–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_98_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]