Abstract

We examine how the shift to remote work altered responsibilities for domestic labor among partnered couples and single parents. The study draws on data from a nationally representative survey of 2,200 US adults, including 478 partnered parents and 151 single parents, in April 2020. The closing of schools and child care centers significantly increased demands on working parents in the United States, and in many circumstances reinforced an unequal domestic division of labor.

Keywords: Remote employment, COVID-19, Gender inequality, Housework, Child care

The pandemic of 2020 disrupted economic and social arrangements everywhere, altering where people work, shop, and eat, whom they can see, and how they imagine their futures. Yet despite the universal sweep of the pandemic, people were affected in radically different ways depending on their circumstances.

In the United States, gender proved to be an enduring cleavage in pandemic experiences. Whereas men experienced greater age-specific mortality from COVID-19, women (particularly those with less education) have suffered more job losses. Not only were they concentrated in hard-hit service sector jobs, but they also faced the loss of child care and schooling that are so essential for primary caregivers of children (Zamarro, Perez-Arce, and Prados 2021). Collins et al. (2020) report that four to five times more partnered mothers of young children have reduced their work hours than fathers. If the recession of 2008 was a “mancession,” then the pandemic of 2020 has been a “shecession” (Henderson 2020).

Before asking how big and long-lasting the consequences of the pandemic will be, we first need to understand how diverse families experienced and responded to sudden changes in employment and child care. We focus here on the immediate consequences for gender inequality in the home. First, we distill debates about how the pandemic affected the gender division of labor among parents. Second, we analyze data from a nationally representative survey of 2,200 U.S. adults, including 478 partnered parents and 151 single parents, conducted during April 2020. We focus on how the shift to remote work and the simultaneous loss of child care and in-person schooling affected the division of domestic work among partnered couples as well as single parents.

The evidence largely indicates that responses to the pandemic have reinforced and even widened gender disparities, though there is also reason for cautious optimism. The pandemic may prompt new policy discussions by exposing the depth of gender inequality in caregiving and the inadequacy of support from our work and caregiving institutions. Once the crisis has passed and children return to school and child care, some of the changes prompted by the pandemic—such as increased remote work—may enable employed parents to develop new ways of combining and sharing paid work and caregiving. Yet first we must understand how the pandemic is playing out in different family contexts.

COMBINING REMOTE WORK AND PARENTING

As an unexpected global event, the pandemic is a natural experiment whose effects can be discerned by comparing “before” versus “after.” The pandemic sparked multiple simultaneous changes affecting social groups in different ways. The rapid adoption of remote work, for example, could be a boon to people who long for greater workplace flexibility. Many work-family scholars have placed the option to partially or fully work remotely high on their list of reforms, arguing this would not only reduce commuting time but allow for more flexibility in integrating home activities with paid work (Correll et al. 2014; Kaduk et al. 2019; Mas and Pallais 2017). Yet the current rapid shift to home-based work has caught workers and firms unprepared, especially alongside closed schools and child care centers. Although some employees have welcomed the opportunity to work at home, few have envisioned doing so without schooling and child care for their children.

Additionally, remote work is a classed option for mostly white-collar workers whose jobs do not require providing in-person services or manipulating machines or tools. Whereas remotely working parents have been expected to suddenly care for children and supervise their education, parents who cannot work remotely have had to find caretakers for their children while they continue to commute to a hospital, grocery store, or other on-site work setting. Still others have had to cope with the demands of full-time parenting after losing their job or seeing their work hours reduced.

In evaluating these sudden large-scale changes, some have pointed to new possibilities for achieving gender equity (Carlson, Petts, and Pepin 2020). If the daily circumstances of mothers and fathers become indistinguishable and the need for “face time” at the office declines, then the classic rationales justifying an unequal division of domestic labor might recede. Yet conclusions—optimistic or otherwise—about the longer-term consequences of more widespread remote work are probably premature. Although surveys conducted early in the pandemic show fathers participating more in domestic activities, particularly fathers working from home (Carlson, Petts, and Pepin 2020; Lyttelton, Zang, and Musick 2020), our findings show that mothers’ participation has also risen, leaving enduring gender disparities.

Less sanguine observers have pointed out that greater work flexibility cannot overcome the combined costs of increased housework, child care, and home schooling. If this unpaid carework falls disproportionately on women, the loss of child care will exacerbate gender inequalities at home, especially given mothers’ greater risk relative to their partners of job loss, reduction in hours, and working from home.1

Zamarro, Perez-Arce, and Prados (2021) provide evidence for this view, reporting that 64 percent of college-educated mothers said they had reduced their working hours by early June, compared with 36 percent of college-educated fathers and 52 percent of college educated-women without young children. In early April 2020, one in three employed mothers reported that they were the main caregiver compared with only one in 10 employed fathers. Lyttelton, Zang, and Musick (2020) found that mothers were spending significantly more time doing housework and caring for children during their working hours in April and May than they did prepandemic. And children spent more than twice as much time with telecommuting moms than dads. Telecommuting fathers increased child care on telecommuting days, but not housework.

These early studies also confirm that closing schools and working from home had more deleterious psychological consequences for mothers than fathers. Zamarro, Perez-Arce, and Prados (2021) report that by early June, only 19 percent of men—with and without kids—stated being at least mildly distressed, compared with 30 percent of women without children and 34 percent of mothers. Lyttelton, Zang, and Musick (2020) find that significantly more telecommuting mothers than fathers reported feeling anxious, depressed, and lonely. A large study by McKinsey & Company (2020)2 reveals similar consequences for dual-earner couples who both work remotely. Though covering only employees of large corporations, the agency reports that the pandemic has prompted many more mothers than fathers to leave the work force or consider that option. Mothers, executive women, and black women also reported greater stress and burn-out. And mothers with children younger than 10 years were more than twice as likely as fathers to worry that their performance is being judged negatively.

To zero in on the consequences of suddenly becoming responsible for the daily care and schooling of children while also working remotely, we focus on partnered parents in households where someone is working remotely, along with a briefer examination of the consequences for single parents. Although dual remote-work parents represent a minority of families, they illuminate how parents respond when both are able to respond to the sudden disappearance of child care.

DATA AND METHODS

Our data come from an online poll conducted for the New York Times in April 2020 (Morning Consult and The New York Times 2020; Miller 2020; Miller and Tankersley 2020). The sample of 2,200 adults, including 629 parents of resident dependent children, was weighted to match the adult population by age, education, gender, race, and region. We focus on the 478 partnered parents with dependent children in the household and then turn to the experiences of 151 single parents. A more detailed description of these subgroups is available in Online Appendix 1.

Our data focus on respondents’ time spent in child care and housework, responsibility for overseeing these tasks, and feelings about the domestic work they perform. We address a range of questions, including

whether respondents are spending more time on housework (cooking and cleaning) and child care during the pandemic;

who is primarily responsible for housework and child care in respondents’ households;

whether respondents have increased their responsibility for housework or child care during the pandemic;

who is spending more time helping children with distance learning; and

how pressured parents feel to oversee their children’s distance learning.

These survey questions are presented in Online Appendix 2.

Our analysis focuses primarily on describing how mothers’ and fathers’ employment and remote work status shaped changes in their time and responsibility for housework and child care during the early stages of the pandemic. Unless noted, results here are statistically significant at the 0.05 level. We also estimated logistic regression models controlling for education, race, children under 12 years in the household, and community size. Results from these models are consistent in magnitude and significance with our descriptive results and are available in Online Appendix 3.

Housework, Child Care, and Home Schooling among Partnered Parents

The relocation of school, child care, and—for many—paid work to the home had substantial effects on the amount of time parents spend on housework and child care, and also altered how responsibility for these tasks is divided within couples. Many parents reported spending more time on housework and child care during the pandemic than they did before. Mothers were more likely to state having increased their housework time (55 percent) compared with fathers (45 percent), but mothers and fathers both reported spending more time on child care (36 and 33 percent, respectively). For some, the pandemic altered the division of responsibility for these tasks. Mothers and fathers were nearly equally likely to state that their responsibility for housework and child care within their household increased during the pandemic: 15 percent of mothers and 14 percent of fathers reported greater responsibility for housework, and 16 percent of mothers and 15 percent of fathers reported increased responsibility for child care.

Despite these observed increases in both responsibility for and time spent on housework and child care, the division of responsibility for these tasks nevertheless remained starkly gendered. Among all partnered parents, 79 percent of mothers said they are primarily responsible for housework in their household during the pandemic compared with 28 percent of fathers. Similarly, 66 percent of mothers stated being primarily responsible for child care compared with 24 percent of fathers.

The division of time spent home-schooling or assisting children with home learning during the pandemic was also starkly gendered. Three-quarters (73 percent) of mothers stated they spent more time on home education than did others in their household, compared with 34 percent of fathers. Mothers were also more likely to say they felt “some” or “a lot” of pressure regarding their children’s home learning (57 percent) compared with fathers (45 percent).

Employed Parents

Gender differences in housework and child care responses to the pandemic were particularly acute among employed parents. A majority (62 percent) of employed mothers reported spending more time on housework than before the pandemic, and 47 percent reported spending more time on child care compared with 47 and 35 percent among employed fathers, respectively. Being employed did not appear to reduce mothers’ shares of responsibility for housework, child care, or home learning within couples. To the contrary, 77 percent of employed mothers reported being mainly responsible for housework, 61 percent reported being mainly responsible for child care, and 78 percent reported taking the lead on helping with their children’s remote learning. The additional domestic demands created by the pandemic affected employed parents—especially employed mothers—in particular. Most employed mothers (64 percent) and half (50 percent) of employed fathers felt “some” or “a lot” of pressure related to their children’s home learning.

Remote Work

Given that mothers who were not employed before the pandemic had greater capacity to absorb the new tasks of full-time child care and home schooling, the intense gendering of these tasks among employed parents is surprising. Time availability explanations are inconsistent with these gender differences. Assessing domestic work when mothers and fathers worked remotely provides some clarity. In families where both parents worked remotely, greater egalitarian sharing across partners appears in some cases but is hardly universal.

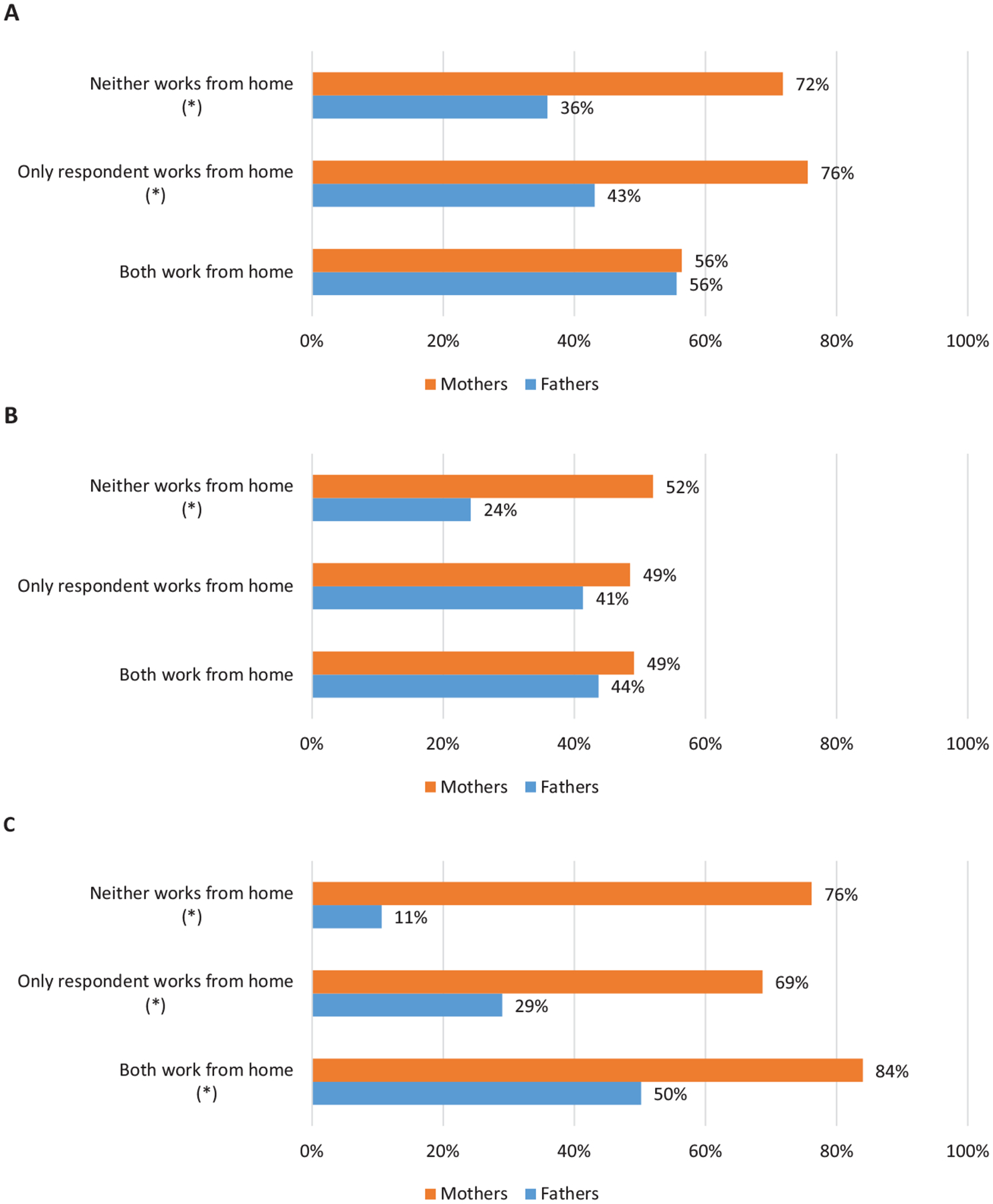

Several findings are instructive. First, both mothers and fathers in dual remote-worker households reported increases in the time spent on housework and child care (see Figure 1A and B). Yet the generally equal increase among both women and men leaves the overall preexisting gender gap largely unchanged. The gender gap did increase in terms of reported time spent on children’s home learning, with 84 percent of mothers compared with 50 percent of fathers spending more time on schooling compared with other household members (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1: Respondents’ Time Spent on (A) Housework, (B) Child Care, and (C) Children’s Home Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared with before the Pandemic.

NOTE: N = 336 partnered working parents. *Gender differences are statistically significant at p <0.05.

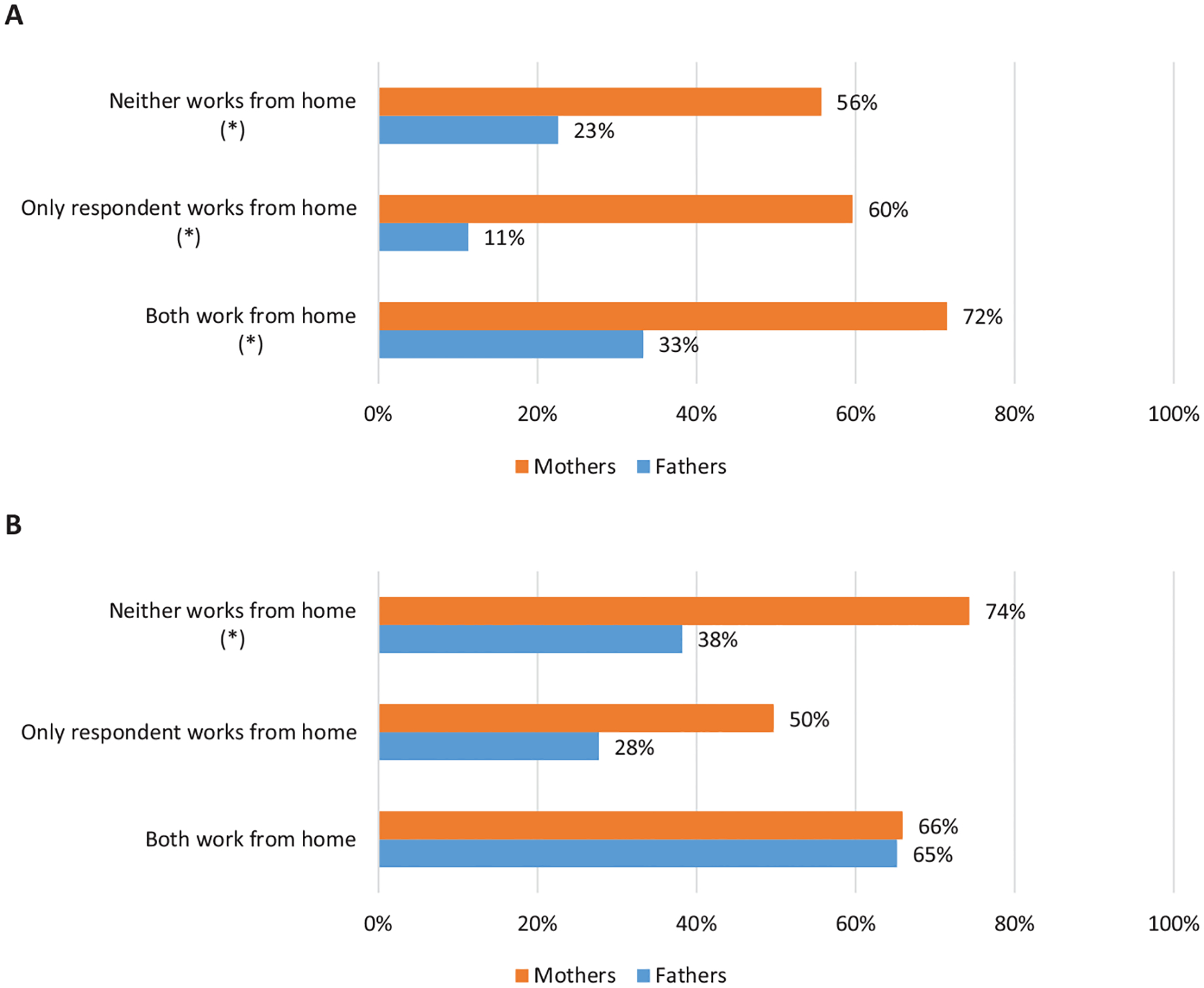

Mothers still feel largely responsible for education and child care even when both parents are theoretically available for these tasks. Among couples who both worked from home, 72 percent of mothers said they were primarily responsible for child care since the beginning of the pandemic compared with 33 percent of men (Figure 2A). In sum, even when both parents worked from home, a gendered division of labor persisted, and the gap neither increased nor decreased. Despite this gendered division of care work, mothers and fathers in dual remote-worker households felt nearly equal amounts of pressure around children’s schooling: 66 percent of fathers and 65 percent of mothers reported “some” or “a lot” of pressure regarding their children’s home learning (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2: Respondents Feel (A) Primarily Responsible for Child Care in Household, and (B) “Some” or “A Lot” of Pressure Regarding Children’s Home Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared with before the Pandemic.

NOTE: N = 336 partnered working parents. *Gender differences are statistically significant at p <0.05.

Disparities in housework, child care, and home education are even greater when only one spouse worked remotely. When fathers alone worked from home, they reported far less involvement in domestic work than did mothers working from home alone. Among mothers who worked from home (but whose spouse did not), 76 percent reported more time doing housework and 69 percent reported more time on their children’s home learning compared with similarly situated fathers (43 percent and 29 percent, respectively). Gendered norms appear to protect teleworking fathers, but not mothers, from extra domestic labor as well as from the stress of their children’s remote learning, even when fathers are the sole parent working from home.

When domestic workloads increased and neither parent worked from home, employed mothers were the ones who mostly picked up the slack—particularly for housework and home learning. Among couples where neither partner worked remotely, 72 percent of mothers reported doing more housework during the pandemic, and 79 percent reported being primarily responsible for housework, compared with 36 percent of fathers who increased their housework and 25 percent of fathers who said they are mainly responsible for housework. In households where no parent worked remotely, most mothers (76 percent) reported taking on the majority of home learning activities for their children, compared with 11 percent of fathers. Consequently, mothers not working remotely were twice as likely as fathers to say they felt “some” or “a lot” of pressure regarding children’s home learning (74 percent compared with 38 percent, respectively).

Single Parenting

Amid the pandemic, being a single parent has posed a distinct set of challenges, including declining access to the networks of support these parents depend on (Tach and Edin 2017). Yet single mothers overwhelmingly said they were primarily responsible for their children’s home learning, even though less than half were working remotely. Because of space limitations, these and other noteworthy findings are discussed in Online Appendix 4.

DISCUSSION

Some have argued that the rise of telecommuting and the loss of child care supports would prompt more domestic equality in child care and housework, especially among dual-earner couples. Others have worried these changes will exacerbate long-standing inequalities and undermine women’s ties to paid work. Our findings suggest neither scenario captures the full array of responses to the pandemic.

We find little evidence that the gender gap in domestic work declined as fathers who began working at home became more involved. Fathers did increase their contributions to housework and child care when both partners worked from home, but this did not change the gender division of domestic work because mothers also increased their involvement. In contrast, the gender gap increased when mothers worked from home, but their partner did not. And in couples where neither parent worked from home or where mothers alone worked from home, mothers became the stopgap who absorbed most of the additional caring and schooling of children. As important, responsibility for these tasks also remained gendered.

In sum, the rise of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic has not appreciably altered the domestic division of labor. When the jobs of both parents moved into the home, the gender gap neither increased nor decreased. In other circumstances, families relied primarily on mothers when parents lost the supports of child care centers and on-site schooling. We cannot know the longer-term consequences of the rise in remote work post-pandemic. Taken together, however, these findings suggest that gender remains a powerful force in organizing domestic work despite the greater flexibility that remote work allows. For reasons that need greater exploration, fathers who work from home are generally better able than mothers to protect themselves from the incursions of unpaid care work. Whether remote work fosters more equality or exacerbates preexisting inequalities will depend on the varied forms it takes in families going forward.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors are listed alphabetically. Thanks go to Barbara J. Risman and the editorial staff at Gender & Society for assisting with earlier drafts of this essay, and to Claire Cain Miller of the New York Times for assistance in accessing the Morning Consult data. This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Award (no. P2CHD042849) to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Biographies

Allison Dunatchik is a PhD student in Sociology and Demography at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research centers on gender, work and family, with a focus on how public policies affect gender and class inequalities inside and outside of the household.

Kathleen Gerson is Collegiate Professor of Arts & Science and Professor of Sociology at New York University. She is the author of “The Science and Art of Interviewing” and “The Unfinished Revolution: Coming of Age in a New Era of Gender, Work, and Family,” among other books. She is currently writing a book on the collision of work and caretaking in contemporary America.

Jennifer Glass is the Centennial Commission Professor of Liberal Arts in the Department of Sociology of the University of Texas–Austin, and Executive Director of the Council on Contemporary Families. Her recent research explores how work–family public policies improve family well-being, and why mothers continue to face a motherhood pay penalty as their income generating responsibility for their children grows.

Jerry A. Jacobs, Professor of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, is the co-founder and first president of the Work and Family Researchers Network. Jacobs has written extensively about women’s careers and work-family issues. His six books include The Time Divide: Work, Family and Gender Inequality (2004) with Kathleen Gerson and the Changing Face of Medicine: Women Doctors and the Evolution of Health Care in America (2008) with Ann Boulis.

Haley Stritzel is a PhD candidate in Sociology and a graduate student trainee in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Haley uses a range of quantitative and demographic research methods to study the family and neighborhood contexts of child and adolescent health. Her dissertation focuses on the geographic distribution and correlates of foster care entries associated with parental substance use.

Footnotes

The demands on single parents have not yet even been discussed much in either academic or popular publications, despite the severity with which this crisis has hit sole parents.

McKinsey & Company (2020) report that they surveyed 40,000 employees in 47 companies in 2019. Although they report “additional” surveys conducted between June and August of 2020, they do not provide either the sample size or the response rate for these supplemental data.

Contributor Information

ALLISON DUNATCHIK, University of Pennsylvania.

KATHLEEN GERSON, New York University.

JENNIFER GLASS, University of Texas-Austin.

JERRY A. JACOBS, University of Pennsylvania

HALEY STRITZEL, University of Texas-Austin.

REFERENCES

- Carlson, Daniel L, Petts Richard J., and Pepin Joanna R.. 2020. Men and women agree: During the COVID-19 pandemic men are doing more at home. They differ over how much, but in most households the division of housework and childcare has become more equal. Council on Contemporary Families Briefing Paper, 20 May. https://contemporaryfamilies.org/covid-couples-division-of-labor/ (accessed January 19, 2021).

- Collins Caitlyn, Landivar Liana Christin, Ruppanner Leah, and Scarborough William J.. 2020. COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work, & Organization. 10.1111/gwao.12506 (accessed August 20, 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll Shelley J., Kelly Erin L., O’Connor Lindsey Trimble, and Williams Joan C.. 2014. Redesigning, redefining work. Work and Occupations 41 (1): 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Tim. 2020. Mothers are 3 times more likely than fathers to have lost jobs in pandemic. Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts, 28 September. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/state-line/2020/09/28/mothers-are-3-times-more-likely-than-fathers-to-have-lost-jobs-in-pandemic (accessed January 19, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Kaduk Anne, Genadek Katie, Kelly Erin L., and Moen Phyllis. 2019. Involuntary vs. voluntary flexible work: Insights for scholars and stakeholders. Community, Work & Family 22 (4): 412–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttelton Thomas, Zang Emma, and Musick Kelly. 2020. Before and during COVID-19: Telecommuting, work–family conflict, and gender equality. Council on Contemporary Families Briefing Paper, 4 August. https://contemporaryfamilies.org/covid-19-telecommuting-work-family-conflict-and-gender-equality/ (accessed January 19, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Mas Alexandre, and Pallais Amanda. 2017. Valuing alternative work arrangements. American Economic Review 107 (12): 3722–59. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org. 2020. Women in the Workplace 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/women-in-the-workplace (accessed November 17, 2020).

- Miller Claire Cain. 2020. Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling; 3 percent of women agree. The New York Times, 6 May. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html (accessed January 19, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Miller Claire Cain, and Tankersley Jim. 2020. Paid leave law tries to help millions in crisis; many haven’t heard of it. The New York Times, 8 May. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/08/upshot/virus-paid-leave-pandemic.html (accessed January 19, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Morning Consult and The New York Times. 2020. National Tracking Poll #200424, April 9–10, 2020.

- Tach Laura, and Edin Kathryn. 2017. The social safety net after welfare reform: Recent developments and consequences for household dynamics. Annual Review of Sociology 43:541–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zamarro Gema, Perez-Arce Francisco, and Prados Maria Jose. 2021. Gender differences in the impact of COVID-19. Review of Economics of the Household. 10.1007/s11150-020-09534-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.