AGITATION, AGGRESSION, AND VIOLENCE: AN OVERVIEW

Agitation is a complex topic, not only in definition but also in administration. It is a state of motor and cognitive hyperactivity marked by inappropriate or excessive verbal or motor activity, as well as emotional excitement.[1] According to Garriga et al., agitation is described as “excessive physical or verbal activity, a temporary emergent scenario that fractures the therapeutic partnership and necessitates prompt and immediate action”.[2] Agitation is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)[3] as “There is a link between excessive motor activity and a feeling of inner stress. Pacing, fidgeting, wringing of hands, pulling of garments, and reluctance to sit still are examples of nonproductive and repetitive actions” (DSM -5). Agitation is also defined as a spectrum of physical, verbal, and emotional arousal symptoms ranging from minor to severe.[4] Table 1 summarizes the main behavioral components of Agitation, which are separated into nonaggressive and aggressive actions.

Table 1.

Component behaviours of agitation

| Nonaggressive behaviors | Aggressive behaviors |

|---|---|

| Restlessness (akathisia, fidgeting) | Physical |

| Wandering | Combativeness, punching walls |

| Loud, excited speech | Throwing or grabbing objects, destroying items |

| Pacing or frequently changing body positions | Clenching hands into fists, posturing |

| Inappropriate behavior (disrobing, intrusive, repetitive questioning) | Self-injury (repeatedly banging one’s head) |

| Verbal | |

| Cursing | |

| Screaming |

Because there is little systematic research in this field, determining the prevalence of acute agitation episodes will be complicated; however, this is a typical emergency seen in emergency rooms, triages, and inpatient facilities. Inpatient, outpatient, and emergency therapeutic settings all have different rates of agitation episodes. It ranges from 10.5%[5] to 52%.[6] It may be higher in emergency clinical settings. Involuntary medication, physical constraint, and seclusion may be used unnecessarily due to ineffective early detection and management of agitation. As agitation is linked to high-risk aggression and violence, early detection of Agitation in a therapeutic environment is critical. In a clinical context, this is critical to protect the patient’s, family’s, and healthcare staff’s safety. Well-developed standardized and appropriate procedures and algorithms can assist healthcare providers in identifying patients at risk of Agitation and assessing and detecting their agitation.[2,7] Martnez-Raga et al. also discuss the preliminary identification of agitation symptoms, which are all listed in Table 2.[8]

Table 2.

Signs for preliminary identification of agitation

| Inability to stay calm or still |

| Motor and verbal hyperactivity and hyperresponsiveness |

| Emotional tension |

| Difficulties in communication |

As health care facilities are not equipped with skilled healthcare professionals (HCPs), and due to ethical/legal concerns on the various management processes, identification and management of the agitated patient in consultation-liaison are vital. Aggression, aggressive, harmful, or destructive behavior, and physical violence in consultation-liaison settings can impair the established therapeutic environment and rapport with a patient, both directly and indirectly. As a result, evaluating and disseminating empirically determined best practices for diagnosing and managing agitation that is culturally acceptable to patients, carers, and HCPs and economically cost-effective to the healthcare system becomes crucial.

ETIOLOGY OF AGITATION

It is critical to understand the etiopathogeneses of agitation, subsequent risk, and predisposition to physical aggression and violence. The etiology of agitation can be divided into two categories, neither of which is mutually exclusive:

Disease-related

In this case, the source of Agitation is a diagnosable disease, which can be either a medical or mental health problem.

Psychiatric symptoms of nonpsychiatric illnesses

Substance abuse due to intoxication or withdrawal

Psychiatric disease (primary).

Behavioral

Agitation results from a person’s actions rather than a medical or mental condition symptom. This grouping is unlikely if patients gain from medical intervention (e.g., anti-social behavior, criminal behavior). A quick verbal de-escalation trial is considered under these circumstances. Depending on the severity of the agitation, security or law enforcement may be considered. Table 3 lists several different etiologies. Past episodes of aggression/violence, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the presence of impulsivity/hostility, more extended hospitalization, and involuntary hospitalization are all individual characteristics that consistently increase the risk of physical violence among agitated patients in psychiatric inpatient settings.

Table 3.

Etiology of agitation

| Primary psychiatric conditions | Medical conditions |

|---|---|

| Delirium | Head injury |

| Dementia | CNS infections- meningitis, encephalitis |

| Substance intoxication (alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, stimulants, hallucinogens, inhalants) | Encephalopathies (hepatic, renal, etc.) |

| Substance withdrawal (alcohol delirium) | Brain tumors/metastases |

| Schizophrenia | Stroke |

| Bipolar affective disorder | Wernicke-korsakoff’s psychosis |

| Agitated depression | Metabolic abnormalities (electrolytes, glucose, calcium, etc.) |

| Anxiety disorder | Hypoxia |

| Personality disorder-antisocial | Toxins/poisoning |

| Autism/intellectual disability | Hormonal (thyroid dysfunction) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | Seizure (postictal state) |

| Adverse effects/toxicity of mediations |

CNS – Central nervous system

ASSESSMENT, EVALUATION, AND APPROACH TO AGITATION

Assessing and evaluating Agitation for medical and psychological causes in therapeutic settings is critical. These three aspects must be highlighted by healthcare personnel during the examination of an intensely agitated patient:

The patient’s, caregivers, and healthcare workers’ safety

Prompt detection or exclusion of life-threatening medical and psychological conditions

A comprehensive differential diagnosis is considered to discover or rule out other common etiologies.

The safety of patients and employees remains at the top of the priority list. The other technique should be adapted to the patient’s level of agitation and the threat level they pose. Regardless of this strategy, it is important to note that any patient, regardless of their initial level of Agitation, is vulnerable to escalation, Agitation, and aggression under the right circumstances. If warning indicators [Table 4] are recognized during the initial evaluation, the physician and team can anticipate agitation/violence.

Table 4.

The signs of impending violence[10]

| Provocative behavior |

| Angry demeanor, fixed gaze, avoidance of gaze, hostile facial expression |

| Loud, excited, aggressive speech |

| Tense posturing (e.g., gripping arm rails tightly, clenching fists) |

| Pacing or frequently changing body position |

| Aggressive acts (e.g., pounding walls, throwing objects, hitting oneself) |

| Behaviour of looking for an escape |

| Physical signs of stress (e.g., hyperventilation, sweating, tremor) |

The following are universal safeguards must be observed during the initial evaluation:

Searching and disarming of patients on a regular, non-confrontational, and nondiscriminatory basis[9]

Interviewing in a calm, quiet, private, but non-isolated environment[10,11]

Objects that could be used as weapons are not allowed in the environment[10,11]

The history and physical examination, which will lead the future evaluation and intervention procedure, can be considered once arrangements for an optimum assessment environment and safety measures have been observed.[12] Any agitation is invariably assigned to psychiatric causes by physicians (anchoring bias), and this bias may induce clinicians to miss or disregard other relevant evidence that could indicate life-threatening illnesses or injuries (confirmation bias).[13] As a result, a thorough history and physical examination can help to reduce bias in clinical decision-making. The primary goal at this stage is to rule out a medical or physical cause for the patient’s symptoms and treat them properly.[14,15]

If patients are cooperative and just slightly agitated, they can describe the circumstances of their presentation, including triggers and appropriate actions. If patients are agitated and unwilling to cooperate, additional sources of information such as friends or family members, attendants, nursing staff, and papers can be used. As shown in Table 5, certain vital information must be acquired from accessible sources.

Table 5.

Critical information which must be part of the history of presenting illness

| Timing of agitation |

| Nature of agitation |

| Concomitant substance use |

| Medication details: changes, new medicines, stopped any medicine |

| Noncompliance to medications |

| Other medical conditions |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE AGITATION

The amount of agitation in an acutely agitated patient can range from non-agitation (average level of activity) to severe Agitation, and it is often dynamic in response to stimulations and interventions (verbal de-escalation or medications). Table 6 shows the standard differentials that can be examined.

Table 6.

Common and potentially life-threatening aetiologies of the acutely agitated patient[16]

| Toxicological | Metabolic |

| Alcohol intoxication or withdrawal | Hypoglycemia |

| Stimulant intoxication | Hyperglycemia/diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Other drugs or drug reactions | Hypoxia |

| Neurologic | Hyper/hyponatremia |

| Stroke | Other medical conditions |

| Intracranial lesion (e.g., hemorrhage, tumor) | Hyperthyroidism/thyroid storm |

| CNS infection | Shock syndromes |

| Seizure disorder | AIDS |

| Dementia | Hypothermia or hyperthermia |

| Psychiatric | |

| Psychosis | |

| Schizophrenia | |

| Paranoid delusional disorder | |

| Personality disorder | |

| Antisocial behavior |

CNS – Central nervous system; AIDS – Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

SMART MEDICAL CLEARANCE PROTOCOL (SMART)

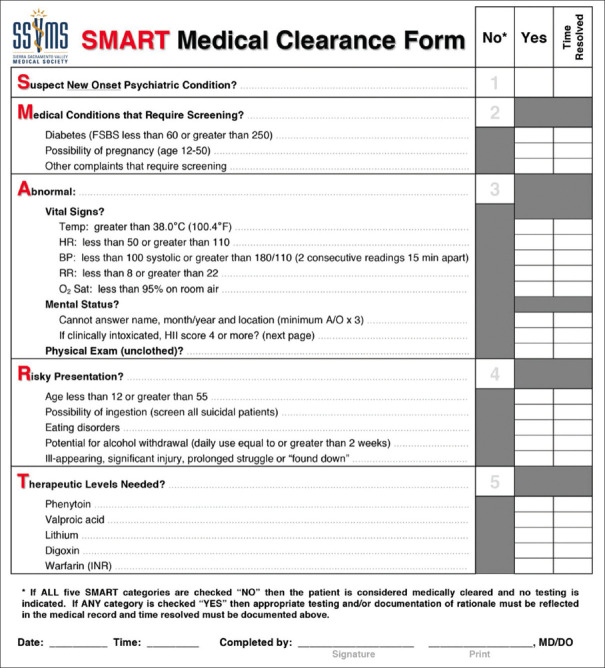

Standardized screening protocols have been created to guide focused medical assessments and applied in some situations to help make quick decisions. The SMART Medical Clearance Approach (SMART), developed by Dr. Seth Thomas and colleagues, is one such protocol, as depicted in Figure 1. This can be tailored to meet the specific clinical demands of the practice.

Figure 1.

SMART medical clearance form

PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION OF AGITATION

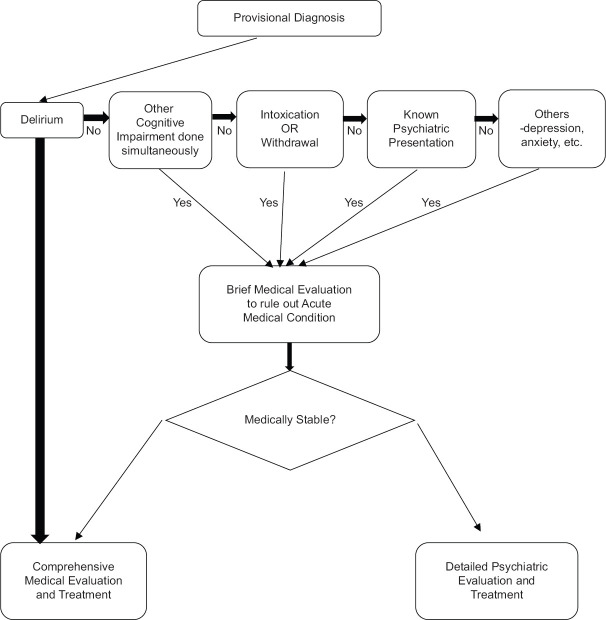

The medical and psychiatric evaluations of agitation are complementary. Initial exploration – history of current disease, Psychiatric status examination (PSE), working diagnosis, differential diagnosis, risk assessment, completion of psychiatric history, and any definite diagnosis will be on the same agenda for both psychiatric and medical evaluations. Figures 2 and 3 show the evaluation algorithm.

Figure 2.

Initial assessment of agitated patient. (*) - ICU - Intensive care unit, HDU - High dependency unit

Figure 3.

Diagnostic evaluation

INTERVENTION

As a first thing to do, the psychiatrist should discuss with referring unit/clinician and explain/educate about the need of:

Intervention goals are from the individual patient’s perspective

-

Need of a structured setting to ensure proper evaluation/interventions

Privacy: room (private/semi-private)

A realistic and clear set of expectations with a written schedule

Staff who is responsible for the individual patient’s care

Attempt and enlist the patient in the treatment, i.e., past good response to the type of medication, total dose received side/adverse effects, and route of administration.

Attempting to engage the patient in the treatment, based on the patient’s previous positive reaction to the type of medication, total dose received side/adverse effects, and mode of administration.

GOALS OF INTERVENTION

The primary purpose is to keep patients and others safe. Collecting samples for laboratory evaluations, establishing rapport, arriving at a provisional diagnosis, facilitating the resumption of the treating team-patient relationship, calming the patient without sedation, and co-management with a medical/surgical team are all goals to be met during the process. Table 7 lists a few general guidelines to follow while dealing with Agitation.

Table 7.

General recommendations in managing agitation

| Initial attempts should identify the most likely cause of agitation and establish a provisional diagnosis and specific medication for the diagnosed cause/condition. Medications as restraint can be discouraged initially before arriving at any provisional diagnosis |

| Nonpharmacologic methods of interventions should be considered. Environmental modifications to reduce stimulation (low lighting, quiet room) and verbal de-escalation have to be considered, if possible, before medications |

| Medications sold calm the patient rather than induce sleep |

| Patient should be kept in the loop of proceedings, even if the patient is agitated. E.g., convey the need for restraints, choice of medication, selection of room/ward, check for preference of route of medicine administration, duration of conditions, etc. |

| If the patient is cooperative to take oral medicines, then oral medication can be preferred based on resources available for managing any acute exacerbation |

MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION

Agitation management begins during the evaluation process; instead, both will co-occur. The steps for dealing with Agitation are as follows: (Hollman and Jeller, 2012)

Medical assessment and triage

Psychiatric assessment

Communication/behavioral Interventions and Verbal De-escalation [Table 8]

Interventions in the environment

Psychopharmacological therapy

Use of restraint/seclusion

Coordination with the medical and surgical teams

Table 8.

Communication/behavioural interventions[18]

| Nonverbal | Verbal |

|---|---|

| Maintain a safe distance | Speak in a calm, more transparent tone |

| Maintain a neutral posture | Personalize yourself |

| Do not stare; the eye contact should convey sincerity | Avoid confrontation; offer to solve the problem |

| Do not touch the patient | |

| Stay at the same height as the patient | |

| Avoid any sudden movements | |

| Aligning goals of care | Monitoring intervention progress |

| Acknowledge the patient’s grievance | Be acutely aware of progress |

| Acknowledge the patient’s frustration | Know when to disengage |

| Shift the focus to a discussion of how to solve the problem | Do not insist on having the last word |

| Emphasize common ground | |

| Focus on the big picture | |

| Find ways to make small concessions |

ENVIRONMENTAL INTERVENTIONS

Environmental interventions will focus on reducing patient sensory stimulation and establishing a safe atmosphere for patients, assisting clinicians in clinical observation, and assuring the patient’s and healthcare workers’ safety. Clearing the space, eliminating harmful objects, having personnel on hand as a “show of force,” close observation, calm dialogue, and lowering the sensory intensity are just a few examples.

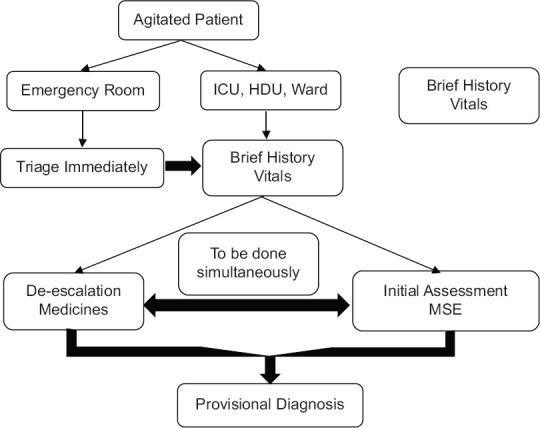

RESTRAINTS FOR MEDICAL REASONS

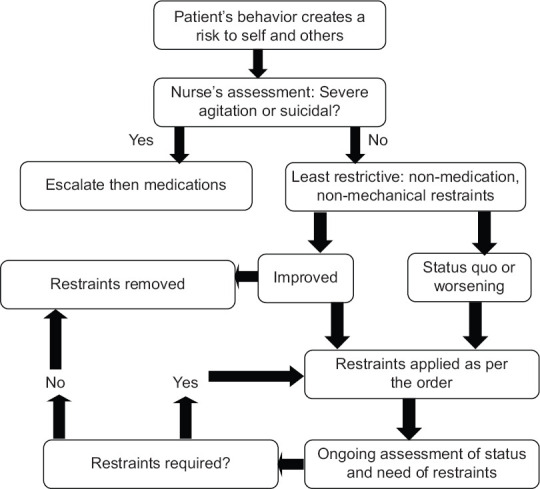

For centuries, medical restraint and isolation have been used in medical and mental settings. Medical restraints have a long history and have developed through time in legal settings.[17] If the patient is unable to assent, written informed consent from the patient and a family member, or solely a family member/legal guardian, must be obtained in the presence of two witnesses. It is essential to know how long medical constraints will last. Every time restrictions are utilized, this should be done. Medical restraints should not be used as a form of punishment or discipline, as a substitute for less restrictive measures, or as a precaution when there is insufficient nursing/healthcare personnel, to name a few examples. Local algorithms can be created to assess when medical restraint can be employed based on the institution’s needs. Figure 4 depicts an example algorithm. Table 9 details the indications and contraindications for medical restraints. Table 10 shows the negative results associated with constraints.

Figure 4.

Algorithm to use medical restraint

Table 9.

Indications and contraindications for medical restraints and seclusion

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Risk of imminent harm to self | Unstable medical condition |

| Risk of imminent harm to others | Severe drug reaction or overdose |

| Serious destruction to the environment | Punishment |

| Staff convenience | |

| Patient’s voluntary reasonable request | If experienced by the patient as positive |

| Decrease sensory overstimulation* | reinforcement for violence or disruptive behavior |

| Only for seclusion* |

*Only for seclusion

Table 10.

Adverse outcomes related to medical restraints

| Patient-related adverse events | Staff-related adverse events |

|---|---|

| Asphyxiation | Spit upon |

| Choking/aspiration | Fracture or skin injury |

| Dehydration | Eye injury |

| Joint injuries | Permanent disability |

| Blunt chest trauma | Adverse emotional reactions (e.g., sadness, guilt, self-reproach, retribution) |

| Skin problems (e.g., Bruising) | |

| Cardiac arrest/death | |

| Rhabdomyolysis | |

| Thrombosis (e.g., PE, DVT) | |

| Escaping restraint | |

| Escalating agitation | |

| Re-traumatization | |

| Emotional distress | |

| Feelings of humiliation, fear, dehumanization, isolation, being ignored |

PE – Pulmonary embolism; DVT – Deep vein thrombosis

ALTERNATIVE MEDICAL RESTRAINTS: PHYSICAL, CHEMICAL, ENVIRONMENTAL, AND SECLUSION

Physical

Hand straps, limb ties, belts, straitjackets, cloth body holders, four-point restraints, tucked securely in bedsheets, bedside rails, and mittens/gloves to avoid scratching are examples of physical restraints. Table 11 lists the elements to consider before employing physical restraints.

Table 11.

Factors to be considered before the physical restraints

| • What are the objectives of physical restraint? |

| • What are the risks associated with particular physical restraint? |

| • Management plan of specific anticipated risks associated with the particular restraint plan |

| • Consensus about the exact timing of using a specific physical restraint |

| • Patient-specific risk factors: age, gender, degree of cooperation, possible intoxication, any medications given, presence of cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, or musculoskeletal disorders |

| • Any specific risk factors that may increase the patient’s risk of harm during restraint? |

| • Vulnerability to significant psychological trauma, especially for minors and the elderly |

| • Any cultural connotations |

| • Availability of emergency medicines, oxygen, required medical equipment |

Chemical

These mainly consist of antipsychotics and benzodiazepines, given orally or intravenously depending on the severity of agitation. These are usually not part of the patient’s continuing treatment plan, and they are primarily intended to limit the patient’s conduct.

Environmental

This includes preventing the patient from moving freely on the premises to guarantee the patient’s and others’ safety. This may be a locked ward.

Seclusion

Entails isolating the patient in a room or area with the doors shut, preventing them from leaving.

MEDICAL RESTRAINT ORDER

The cause for the restriction, the duration of the medical restraint, the type of confinement, and the monitoring schedule should all be included in the medical restraint order. Nutrition, hydration, elimination, hygiene, range of motion, and circulation are all essential needs that must be met for the patient. In addition, the file should include the following documentation: a clinician’s order, an initial assessment by the resident doctor/duty doctor, and an in-person evaluation by the consultant as soon as possible, alternatives that were considered and tried, patient monitoring and outcomes of interventions used, periodic re-assessments for vitals and progress of agitation and physical condition, and psychoeducation of the patient and family member about the medical restraint provided.

INSTRUCTIONS TO THE STAFF CARRYING PHYSICAL RESTRAINT

The personnel in charge of physical restraint should be given specific instructions, as shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Instructions to the staff carrying physical restraint

| Before physical restraint |

| Know the steps and plan clearly |

| Adheres to the plan discussed to execute the use of physical restraint safely. Ensure that mechanical and postural factors should not interfere in breathing or circulation: e.g., to avoid prone restraint or any other position where the patient’s head or trunk is bent towards their knees |

| During the physical restraint |

| Physical force used should be as per the necessity and in a reasonable manner |

| To avoid excessive physical force or verbal aggression |

| Ensure and monitor ABC all the time: Airway, Breathing, Circulation |

| Consciousness and body alignment have to be monitored by the clinician |

| Do not put direct pressure on the neck, chest/thorax, back, or pelvic area |

| Nurse/resident doctors/duty doctors must observe for physical or mental distress indications and ensure that clinical concerns are timely and appropriately escalated and appropriate intervention is provided |

| Specifically, monitor patients who have received intramuscular or intravenous medication within an hour before (or during) the use of physical restraint |

| On period reviews, if necessary, physical restraint positions can be changed as per the need and safety of the patient |

| Discontinue physical restraint as soon as it is no longer required |

| Risk assessment of continuing or discontinuing the physical restraint needs to be continuously assessed and balanced |

| Postrestraint debriefing |

| After the physical restraint ends and the patient is cooperative, a debriefing session with the patient and the patient’s caretakers must be conducted. This is done |

| To ensure open discussion about the events that led to the use of physical restraint |

| To discuss the patient’s experience of events and physical restraint |

| To allow the patient to clarify any doubts or seek more details |

| To provide an opportunity to identify the risk factors and plan strategies for the prevention of the need for physical restraint |

DOCUMENTATION DURING RESTRAINT

Accurate and complete documenting of restraint episodes is required for adequate and improved care. It will start with the cause for the constraint, and the patients and family member’s/legal representatives’ informed permission. The documentation should include the patient’s mental status, details of medical restraints used and where they were used, vitals, airway/breathing/circulation, condition of limbs, range of motion in limbs, notes on skin care-change of posture, sponge bath, etc., liquids, food, and toileting offered. Appendix 1 is a sample medical restraint flowsheet.

Table 13.

Factors to be considered while choosing medications

| • Patient’s details: Age, gender, comorbid medical conditions, substance use, allergies |

| • Agitation details: Cause, presentation |

| • Pharmacological considerations: Route of administration, rapidity of action, duration of action, adverse effects and interaction with other medications, past good response to any particular psychotropic |

| • Monitoring facilities: Airway, breathing, and circulation monitoring facilities; crash cart for any medical emergency, availability of ICU and ventilator |

| • Patient’s preference of route of administration |

| • Route of administration |

| • Oral: Tablets or syrups can be preferred if the patient accepts |

| • IM: Helps in rapid elevation of drug plasma levels and faster onset of action, leading to an immediate reduction in agitation |

| • IV administration should be preferred when rapid restraint is essential |

| • IM – Intramuscular; IV – Intravenous; ICU – Intensive care units |

ALTERNATIVES TO RESTRAINT

According to,[19] about 90% of emergency departments consider employing an alternative before restricting. The most popular strategy is the one-on-one verbal discourse, followed by a time-out or pastoral care. Konito et al. propose three common alternatives:[20,21]

Interventions by nurses – The simple presence of nursing staff around the clock and regular staff talks with the patients will keep them engaged and reduce the likelihood of hostility

Multi-professional agreements involving patients – It was discovered that agreements between physicians, nursing staff, and patients about medications, dosage, ward difficulties, and restraint and seclusion criteria would encourage patients to participate in the treatment process, making them more cooperative and less aggressive

The use of authority/power, whether in the form of ward staff strength or a person with authority, such as a clinician or a senior nurse - presence or a conversation with the authority will aid in managing the violence without the need for restraint.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Despite these efforts, the patient continues to threaten, toss things, pace, and make hitting gestures, prompting medication use. However, medication preparation should be done at all times. Each hospital ward should have a crash cart with the psychotropics needed for sedation. Security guards should be alerted before the start of the assessment so that they are ready to help right away.

GOALS OF PHARMACOTHERAPY

-

Pharmacotherapy for acute agitation should, in theory, include the following:

Be non-traumatic and straightforward to use

Have a quick beginning of an action (rapid tranquilization) and last long enough without causing severe sedation

Have a low or no risk of severe side effects and drug interactions.

-

Rapid tranquilization should be the goal of psychopharmacologic treatment[7]

Calming process separate from total sleep induction

Allows the patient to participate in the care

Helps the clinician to collect history, start a work-up, and initiate the treatment of unidentified conditions

Better therapeutic endpoint

-

Sleep induction is not the desired outcome.

It conflicts with the goal of participation by the patient

It may not be essential for the improvement in the agitation or decrease in the psychotic symptoms.

PHARMACOLOGIC CONSIDERATIONS

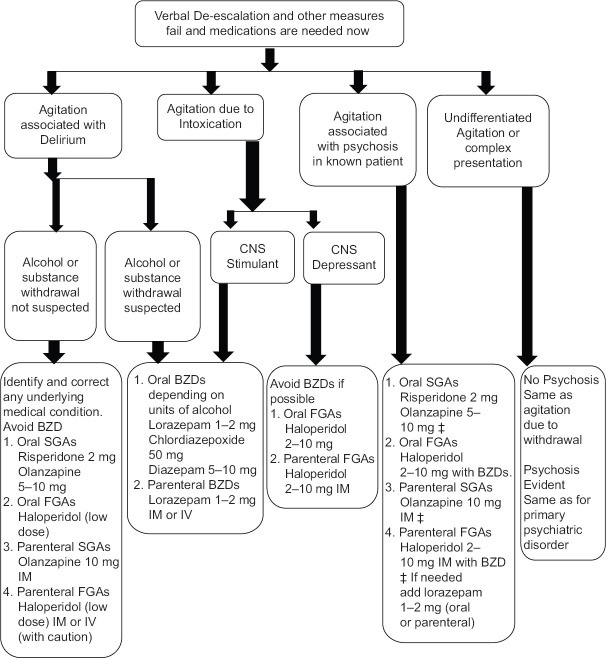

The drugs used to treat agitation should be kept in the crash cart. These should be simple to store. It will help if these can be reconstituted and administered quickly. Furthermore, these drugs should have a quick onset of effect. When using the parenteral method, the same medicine may act quickly. The treating team must decide the route of administration based on the severity of the agitation. In general, intravenous administration delivers drugs quickly, and the beginning of action is quicker than when pharmaceuticals are injected intramuscularly or orally. Intravenous formulations are preferred in cases of acute agitation. The medication should be adequate for a long time after being given. The drug supplied should have few side effects and no interactions with other medications. Table 13 lists the elements to consider while selecting drugs. Pharmacological intervention algorithm is given in Figure 5.

Table 14.

Medications used in managing agitation

| Initial dose (mg) | Tmax* (min) | Can repeat (h) | Maximum dose (per 24 h), mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | ||||

| Risperidone | 2 | 1 h | 2 | 6 |

| Olanzapine | 5-10 | 6 h | 2 | 20 |

| Haloperidol | 5 | 30-60 | 15 m | 20 |

| Lorazepam | 2 | 20-30 | 2 | 12 |

| IM | ||||

| Olanzapine | 10 | 15-45 | 20 m | 30 |

| Haloperidol | 5 | 30-60 | 15 m | 20 |

| Lorazepam | 2 | 20-30 | 2 | 12 |

| Ziprasidone | 10-20 | 15 | 10 mg q 2 h | 40 |

| 20 mg q 4 h | ||||

| >Aripiprazole | 9.75 | 1 h | 2 | 30 |

| IV | ||||

| Haloperidol | 5 | Immediate | 4 | 10 |

| Lorazepam | 2 | Immediate | 2 | 12 |

Maximum doses can vary depending on the outcome. q 2 h – Every 2 hours; q 4 h – Every 4 hours, IM – Intramuscular; IV – Intravenous

Figure 5.

Pharmacological intervention

EMERGENCY PSYCHIATRY/AGITATION PHARMACOLOGICAL PREPARATION SALIENT INFORMATION

Combination therapy

-

Medications can be chosen to target to manage different components of agitation

Anxiety and increased arousal, to use benzodiazepine

Psychotic symptoms, use of antipsychotic.

To reduce the side effects combining medications at low doses will help while obtaining the desired effect

-

Most common combination

Haloperidol 5 mg IM

Lorazepam 2mg IM.

-

Benefits

Faster reduction in agitation

Fewer injections required

Simple to administer

Lower incidence of EPS.

-

Side effects

Overall, very well tolerated

-

The most common adverse reaction is excess sedation.

Recent studies suggest sedation rates appear similar to lorazepam treatment alone.

Special population: Intensive care unit patients

Mechanically ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients: analgesia and sedation are recommended

Atypical antipsychotics can reduce the duration of delirium in ICU patients

Special population: Weaning of ventilation

-

Dexmedetomidine (alpha 2 adrenergic sedative).

Better than midazolam (hypertension and tachycardia, time intubated)[1]

Better than haloperidol (time intubated, length of stay).

Association for emergency psychiatry recommendations are outlined in Table 14.

Table 15.

Use of benzodiazepines and typical antipsychotics in agitation

| Medication class | Medication | Dosing | Side effects/considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine | Alprazolam | Only available PO | Paradoxical reactions can be seen in character-disordered patients and can worsen symptoms in the elderly |

| Initial dose is 0.5-4 mg/day | |||

| Diazepam | PO, IM, IV | Calming/sedating effect with rapid onset | |

| Start at 5 mg | Use cautiously with elderly patients because of the long half-life | ||

| Lorazepam | PO, SL, IM, IV | There are no active metabolites; therefore, there is a small risk of drug accumulation | |

| Start at 1 mg, moderate half-life (10-20 h) | Metabolized only via glucuronidation; therefore, it can be used in most patients with impaired hepatic function | ||

| Drug of choice within this class due to the moderately long half-life | |||

| Typical antipsychotics | Haloperidol | PO, IM, IV | High-potency neuroleptic with favorable side-effect profile and cardiopulmonary safety |

| Start at 5-10 mg IM, IV | IV form less likely to cause EPS | ||

| ECG monitoring is needed to assess torsades de pointes or QTc prolongation | |||

| NMS risk increases in poorly hydrated, restrained, and kept in poorly aerated rooms while given large doses of antipsychotics | |||

| Frequent vital sign checks and testing for muscular rigidity are recommended | |||

| Can cause hypotension |

Adapted from Allen M, Currier G, Carpenter D: The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of behavioral emergencies, J Psychiatr Pract 11:1-112, 2005. CVD – Cardiovascular disorder; ECG – Electrocardiogram; EPS – Extrapyramidal symptoms; IM – Intramuscular; IV – Intravenous; NMS – Neuroleptic malignant syndrome; PO – Per os (by mouth, orally); SL – Sublingual; PR – Per rectum

The role of benzodiazepines and antipsychotics is shown in Tables 15 and 16.

Table 16.

Use of benzodiazepines and typical antipsychotics in agitation

| Medication class | Medication | Dosing | Side effects/considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical antipsychotics | Risperidone | PO, OTD | No IM form is available |

| Starting dose 0.5-2 mg acutely | Offers calming effect with the treatment of the underlying condition | ||

| Orthostatic hypotension with reflex tachycardia | |||

| Increased risk of stroke in the elderly with CVD | |||

| Olanzapine | PO, OTD, IM | Useful in patients with poor reaction to haloperidol | |

| Starting dose 2.5-5 mg, maximum 30 mg/24 h with doses 2-4 h apart | Calming medication with the treatment of the underlying disorder | ||

| Aripiprazole | PO, OTD | Akathisia risk | |

| Starting PO dose 5-10 mg, maximum 30 mg/day (currently IM formulation only for extended-release maintenance therapy) | Less sedating than other medications | ||

| Increased risk of stroke in the elderly | |||

| Good choice for patients with QT interval prolongation | |||

| Combinations | Haloperidol, lorazepam, diphenhydramine, or benzatropine | 5 mg IM, 2 mg IM, 50 mg IM, 1 mg IM | Most commonly used in the acute setting |

| Young athletic men are at increased risk for dystonia | |||

| Akathisia must be considered if agitation increases after administration |

PO – Per os (by mouth, orally); OTD – Orally disintegrating tablet; IM – Intramuscular; CVD – Cardiovascular disorder

CONCLUSION

This article includes a comprehensive discussion of the etiology, evaluations, treatment options, current international accepted agitation management practice, and practical guidance for physicians treating Agitation in inpatient psychiatric and consultation-liaison settings. Agitation should be recognized early using warning signals, and nonpharmacological therapies should be used to deescalate the patient’s agitation, according to internationally accepted agitation management practice. If these tactics do not work, recommendations suggest using medical restraint to calm patients rather than sedating them too quickly. The doctor must decide whether to use a medical restraint order that is non-invasive and simple to use, has a quick onset, successfully calms the patient without sedating them unduly, and treats the patient’s agitation. Medical staff must be trained through mock drills in addition to medical restraint orders and alternatives to ensure best practice. Along with that, documentation and monitoring of the patient’s continued need for medical restraints, mental status, details of medical restraints used and location of restraints, vitals, airway/breathing/circulation, condition of limbs, range of motion in limbs among patients on medical restraint orders, and the alternative is necessary to ensure adequate care and follow the best practice, which is socio-culturally acceptable, suitable, and legally accepted for low-intensity medical restrain.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

APPENDIX

| Appendix 1 |

|---|

| Medical restraint flowsheet |

| I. Patient’s details |

| Name: Age: Gender: Male/female/others Hosp. No. |

| II. Clinician’s order |

| Name: Dr. Date: Time: |

| a. Doctor’s Orders (orders must be renewed every 12–24 h based on the practice) |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| b. Initial Order |

| Start: Date/time |

| End: Date/time |

| c. Repeat order |

| Start: Date/time |

| End: Date/time |

| III. Alternatives attempted before initiation of medical restraints (check all that apply) |

| □Re-orient patient to time/date/place/person and/or situation |

| □Move patient closer to the nurses’ station |

| □Conceal lines/tubes/devices |

| □Minimize stimulation |

| □Reevaluate need for lines and tubes |

| □Appropriate diversional activities |

| □Repositioning |

| □Pain and sedation intervention |

| □Other |

| IV. Indication for using medical restraints |

| □Pulling lines |

| □Pulling tubes |

| □Removal of equipment |

| □Removal of dressing |

| □Inability to respond to direct requests or follow instructions |

| □Other |

| V. Type and details of medical restraints applied (Tick all that applies) |

| Wrists: Both/right only/left only |

| Legs: Both//right only/left only |

| Gloves/mittens: Both//right only/Left only |

| Waist Belt: Yes/No |

| Side railings: Yes/No |

| VI. Psycho-education of the patient |

| a. Informed the patient about the need and alternatives for medical restraints. Yes/No |

| b. Periodically patient has explained the behavior required to discontinue the restraint until an understanding was evidenced. Yes/No |

| Nurse’s name and sign Date and time |

| Doctor’s name and sign Date and time |

Medical restraint flow sheet contd…

| VII. Patient’s monitoring chart |

| In the first hour, observation checks are done every 15 min, then hourly |

| •15 min: Time_______ Behavior (**See Key)___________ Initials____________ |

| •30 min: Time_______ Behavior (**See Key)___________ Initials____________ |

| •45 min: Time_______ Behavior (**See Key)___________ Initials____________ |

| •60 min: Time_______ Behavior (**See Key)___________ Initials____________ |

| Time (hours) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation check | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (**See Key) Q1h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Circulation/skin check | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q2h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Food/fluids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q2h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elimination (or F for Foley in place) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q2h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Range of Motion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q2h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in type or number of Restraint (*See Key) Q1h |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Staff initials | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key: *Restraints | **Observed Behavior (May use more than one) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| NC=No change | CF – Confused; AG – Agitated; VA – Verbally abusive; TF – Tearful; JC – Hallucination; DL – Delusional; A – Patient asleep; SD – Sedated; SB – Subdued; CA – Calm; CO – Cooperative; O – Other | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↑3=Increase to 3pt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↑4=Increase to 4pt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓1=Decrease to 1pt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓2=Decrease to 2pt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ↓3=Decrease to 2pt |

VIII. Restraint discontinued:

Date: ................... Time: ....................... ◻N/A (ongoing)

Discontinue restraint at the earliest possible time that it is safe to do so, regardless of the scheduled expiration time of the orders

Table investigations and rationale

Table investigations and rationale

| Investigation | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Haemogram: Hb, TC, DC, ESR, Platelets, Indices | To evaluate infective etiology, anemia |

| RFT: Urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium | To evaluate renal causes and electrolyte imbalances |

| LFT: Total/direct bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, total protein, albumin, globulin, A/G ratio | To evaluate hepatic causes, acute/chronic liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy |

| TFT: T3, T4, TSH | To evaluate thyroid etiology |

| Sugars: RBS, FBS, PPBS, HBA1C | Hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia related causes |

| Urine complete analysis, microscopy, and urine drug screening | For detection of substances |

| Serum toxicology | Based on the history |

| Drug levels | If on valproic acid, lithium, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and toxicity is suspected |

| Ultrasound abdomen and pelvis | Based on history and indication: Blunt trauma abdomen |

| 12-Lead ECG | For cardiac causes and cardiac monitoring for medication-related changes |

| CT/MRI brain/part of the interest | As per the history and indication |

| Lumbar puncture and EEG | As per the indication |

Hb – Hemoglobin; HBA1C – Hb A1C; AST – Aspartate transaminase; ALT – Alanine aminotransferase; FBS – Fasting blood sugar; CT – Computed tomography; MRI – Magnetic resonance imagin

Association for Emergency Psychiatry Recommendations

| Situation | Preferences |

|---|---|

| Undifferentiated agitation/suspected intoxication with stimulant or withdrawal from alcohol/benzodiazepine | Oral benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam 1-2 mg) |

| Parenteral benzodiazepines (e.g., lorazepam 1-2 mg IM or IV) | |

| Acute intoxication with CNS depressant (e.g., alcohol) | Avoid benzodiazepine if possible |

| Oral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., haloperidol 2-10 mg) | |

| Parenteral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., haloperidol 2-10 mg IM) | |

| Delirium (not associated with alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal) | Oral 2nd generation antipsychotic (e.g., risperidone 2 mg, olanzapine 5-10 mg) |

| Oral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., low dose haloperidol) | |

| Parenteral 2nd generation antipsychotic (e.g., olanzapine 10 mg IM) | |

| Parenteral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., haloperidol low dose IM or IV) | |

| Schizophrenia or mania | Oral 2nd generation antipsychotic alone (e.g., risperidone 2 mg, olanzapine 5-10 mg) |

| Oral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., haloperidol 2-10 mg with benzodiazepine) | |

| Parenteral 2nd generation antipsychotic (e.g., olanzapine 10 mg IM) | |

| Parenteral 1st generation antipsychotic (e.g., haloperidol 2-10 mg IM) along with benzodiazepine (e.g., lorazepam 1-2 mg) |

CNS – Central nervous system; IV – Intravenous

Salient pharmacological features of benzodiazepines

| Class/molecule | Pharmacological features |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | Act by facilitating the activity of GABA, which is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter |

| Therapeutic effects due to decreased arousal | |

| Target symptom anxiety | |

| Can be used alone or in combination with antipsychotics | |

| Preferred in a patient in whom agitation is secondary to alcohol or sedative withdrawal | |

| Side effects to consider | |

| Excessive sedation; added sedation when combined with CNS depressant | |

| Respiratory depression; to avoid in patients with risk for CO2 retention | |

| Paradoxical disinhibition in high doses in patients with structural brain damage, mental retardation, or dementia | |

| Ataxia | |

| Typical antipsychotics (FGA) | Dopamine antagonist |

| Advantageous effects: as antipsychotic and for agitation | |

| Preferred in acute agitation | |

| Low potency FGA: Not recommended | |

| High potency FGA (haloperidol): virtually no anticholinergic properties, little risk of hypotension, no respiratory depression, can be given IV, the onset of action is within 30 min and lasts up to 12-24 h | |

| Side effects to consider | |

| EPS | |

| Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) | |

| Dystonia | |

| Akathisia | |

| Parkinson-like effects | |

| QTc prolongation | |

| May lower the seizure threshold | |

| Atypical antipsychotics (SGA) | Broader spectrum of response |

| Different side effect profile | |

| Fewer EPS and akathisia | |

| QTc concern remains | |

| Metabolic syndrome on prolonged use | |

| Olanzapine | |

| IM dose range of 5-10 mg | |

| Maximum of 30 mg/day | |

| 15-45 min until peak plasma concentration | |

| 21-54 h elimination half-life | |

| Oral dose range 5-10 mg and flexible-dose up to 40 mg/day | |

| Risperidone | |

| 1–6 mg PO or ODT | |

| Oral risperidone concentrate 2 mg+oral lorazepam 2 mg equivalent to IM haloperidol 5mg+IM lorazepam 2 mg | |

| Oral risperidone 2 mg equally effective as oral haloperidol 5 mg | |

| Risk of EPS | |

| Aripiprazole | |

| Partial dopamine agonist | |

| Oral aripiprazole 15 mg as effective as oral olanzapine 20 mg | |

| Low risk for QT interval prolongation (<1%) | |

| Quetiapine | |

| 25 mg onwards up to 400 mg | |

| 1–3 h to peak plasma concentrations | |

| Shallow risk of EPS | |

| Sedation and orthostasis are side effects |

FGA – First generation antipsychotics; EPS – Extrapyramidal symptoms; SGA – Second generation antipsychotics; CNS – Central nervous system; IV – Intravenous

REFERENCES

- 1.Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, Stiebel V, Ng AT, Bregman B, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient:consensus statement of the American association for emergency psychiatry project Beta medical evaluation workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:3–10. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garriga M, Pacchiarotti I, Kasper S, Zeller SL, Allen MH, Vázquez G, et al. Assessment and management of agitation in psychiatry:Expert consensus. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17:86–128. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2015.1132007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. (DSM-5); Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeller SL, Rhoades RW. Systematic reviews of assessment measures and pharmacological treatments for agitation. Clin Ther. 2010;32:403–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellesdal L. Aggression on a psychiatric acute ward:A three-year prospective study. [Internet] [Last cited 2016 Dec 19];Psychol Rep. 2003 92:1229–48. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.3c.1229. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2466/pr0.2003.92.3c.1229?journalCode=prxa . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreaux ED, Allen MH, Claassen C, Currier GW, Bertman L, Glick R, et al. The Psychiatric Emergency Research Collaboration-01:Methods and results. [Last accessed on 2021 Nov 15];Gen Hosp Psychiatry. [Internet]. 2009 31:515–22. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.009. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0163834309000863 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieta E, Garriga M, Cardete L, Bernardo M, Lombraña M, Blanch J, et al. Protocol for the management of psychiatric patients with psychomotor agitation. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:328. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Raga J, Amore M, Di Sciascio G, Florea RI, Garriga M, Gonzalez G, et al. 1st International Experts'Meeting on Agitation:Conclusions Regarding the Current and Ideal Management Paradigm of Agitation. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Emergency department violence:prevention and management. Dallas, TX: ACEP; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice MM, Moore GP. Management of the violent patient. Therapeutic and legal considerations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1991;9:13–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tardiff K. The current state of psychiatry in the treatment of violent patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:493–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820060073013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn W. Violence in the emergency department. Managing aggressive patients in a high-stress environment. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:143–8. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1999.01.504. 154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandhu H, Carpenter C, Freeman K, Nabors SG, Olson A. Clinical decision making:Opening the black box of cognitive reasoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:713–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.011. Epub 2006 Jun 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukens TW, Wolf SJ, Edlow JA, Shahabuddin S, Allen MH, Currier GW, et al. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Critical Issues in the Diagnosis and Management of the Adult Psychiatric Patient in the Emergency Department, Clinical policy:Critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:79–99. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolia V, Wilson MP. The medical clearance process for psychiatric patients presenting acutely to the emergency department. In: Zun L, Chepenik L, Mallory M N, editors. Behavioral Emergencies for the Emergency Physician. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2013. pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore G, Pfaff J. A. Hockberger R. S. (Ed.), Waltham MA., editors. Assessment and emergency management of the acutely agitated or violent adult. In UpToDate. [Last accessed 2021 Dec 16]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/assessment-and-emergency-management-of-the-acutely-agitated-or-violent-adult.

- 17.Holloman GH, Jr, Zeller SL. Overview of Project BETA:Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:1–2. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onyike C, Lyketsos C. Aggression and violence. Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine:Psychiatric Care of the Medically Ill, 2011;101:153–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downey LV, Zun LS, Gonzales SJ. Frequency of alternative to restraints and seclusion and uses of agitation reduction techniques in the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:470–4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontio R, Välimäki M, Putkonen H, Kuosmanen L, Scott A, Joffe G, et al. Patient restrictions:Are there ethical alternatives to seclusion and restraint? Nurs Ethics. 2010;17:65–76. doi: 10.1177/0969733009350140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raveesh BN, Gowda GS, Gowda M. Alternatives to use of restraint:A path toward humanistic care. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S693–S697. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_104_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]