Abstract

This study explored the role of social activism in the association of exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests with perceptions of mental health. Data for this study came from a sample of African Americans (N = 304) who responded to an online survey. Perceptions of mental health were assessed using a single item developed by the research team. Exposure to police brutality and protests was measured by asking how often they had seen or heard about African Americans being victims of police brutality and seen or heard about protests on television, social media, or other outlets. Participants were also asked about the extent to which these events caused them emotional distress. Social activism was assessed by asking participants if they had ever participated in political activities, such as calling their representative. Moderation and mediation analyses were conducted using linear regression. Moderation analyses showed that greater emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests was associated with worse perceptions of mental health only when engagement in social activism was low. In contrast, mediation analyses indicated that greater frequency of and emotional distress from exposure to media coverage was indirectly associated with worse perceptions of mental health through increased engagement in social activism. Social activism may be an important method for coping with emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests, but more research is needed to understand how African Americans might engage in social activism without adversely impacting mental health.

Keywords: Poor mental health, African Americans, Police brutality, Protests, Social activism, Media

Introduction

The death of George Floyd while in police custody in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on May 25, 2020, rocked the USA [1]. Within 3 days, over 8.8 million tweets had been tagged with the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) hashtag on Twitter [2], and by June 5, videos related to George Floyd and BLM had been shared over 1.4 billion times on Twitter alone [3]. Floyd’s death mobilized millions of Americans to protest for racial equality and law enforcement reform. Between May 26 and August 22, over 7750 protests and demonstrations occurred across more than 2440 locations in the USA [4]. Although less than 5% of these protests were violent, this period of unrest was associated with at least 19 deaths, more than 14,000 arrests, and $1–2 billion in property damages, with $500 million in damage in Minneapolis–Saint Paul alone [5]. In addition, the death of George Floyd and the unrest that occurred after likely contributed to widespread psychological distress across the country, with African Americans bearing a disproportionate share of the poor mental health burden. According to data from the US Census Household Pulse survey, the prevalence of depression and anxiety was significantly higher among African Americans than Whites in the week following George Floyd’s death [6].

Police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans are not only a racial health equity issue [7], but also a broad public health issue because some incidents involving police brutality receive national and worldwide media coverage (like exposure to terrorist attacks, controversial political events, and natural disasters), and as a result, may contribute to psychological distress beyond the affected population [8]. Also known as spillover effects, people are most often indirectly or vicariously exposed to police brutality against African Americans via victimized relatives or friends, through discussions about these events with social contacts, by watching television, listening to the radio, reading the newspaper, or more recently, using social media [9, 10]. For example, research conducted in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks demonstrated that watching or reading coverage of the attack was associated with poor mental health in the broader US population, including posttraumatic stress symptoms [11, 12]. Further, Tynes et al. demonstrated that more frequent exposure to traumatic events online, such as a viral video of an African American being shot by a police officer, was associated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms and depressive symptoms in a sample of African American and Latinx adolescents and young adults [13]. Other studies have also shown that the deaths of African Americans, particularly unarmed individuals in police custody, contribute to poor mental health within the African American population [14–16].

Police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans sometimes trigger strong social reactions. After the death of George Floyd, numerous researchers observed a sharp decline in anti-Black attitudes in the general population, increased public awareness of structural racism, and a strong desire for social change [17–19]. Further, numerous organizations published statements supporting BLM and social reform [20] and crafted proposals to reimagine public safety in urban environments [21, 22]. Research is needed to determine the extent to which social and political engagement to address police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans might protect against psychological distress. Studies that examine the political behavior of college students have found that African Americans who experience racism and discrimination experience lower levels of depression and anxiety when they outwardly support social justice groups, such as BLM [23, 24]. Taking action, such as delivering a speech or participating in a protest, increases feelings of optimism and empowerment, and increases social solidarity and identification with one’s racial and social class background, which have been shown in prior research to alleviate psychological distress [25–27]. Therefore, social activism may serve as a potent adaptive coping strategy for African Americans exposed to police-involved injuries and killings.

However, engagement in social activism does not always benefit mental health and can even sometimes be harmful. For example, people may experience burnout and fatigue due to the excessive psychological and emotional demands associated with sustained long-term activism [28]. Engaging in activism may also increase visibility and thus vulnerability to being victimized and isolated by political opposition and the general public, and sometimes may disrupt relationships with friends and family members due to ideological differences [29]. Also, personal identities and traumatic experiences are powerful motivators for becoming socially engaged [30]. For example, many African Americans who have experienced police victimization become socially engaged and influential advocates for reform [31]. However, these same individuals may be more sensitive to progress within the social movement than those who lack a personal connection [32]. Therefore, when a social movement fails to achieve its mission, the people who strongly identify with the movement may suffer from poor mental health outcomes, such as anxiety and depression, because they begin to feel hopelessness or despair in the face of perceived injustice [33].

Overall, it is plausible that social activism can serve as both a moderator and mediator when examining the association between media coverage of police brutality and protests with poor mental health [34]. For example, on the one hand, African Americans may engage in social activism to voice concerns about incidents of police brutality towards African Americans, which could improve mental health compared to African Americans who choose not to engage in social activism after learning about incidents of police brutality. On the other hand, after being exposed to media coverage of police brutality, engaging in social activism may contribute to poor mental health because they may face additional hardship as they challenge the status quo, such as being harmed during a protest or being stigmatized by close friends or relatives because of ideological differences [29]. This study will explore social activism as a potential moderator and mediator using the “competing models” approach [35, 36]. Because this current study will use a cross-sectional dataset to examine the potential dualistic role of social activism, social activism will be tested as a moderator and mediator in separate models to identify empirical support for either one or both models. The primary hypothesis is that support will be demonstrated for both the moderation and mediation models. In particular, the risk of poor mental health associated with exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests will decrease as engagement in social activism increases, and it is also hypothesized that media coverage of police brutality and protests will be indirectly associated with an increased risk of poor mental health through greater engagement in social activism. Secondarily, exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests will be associated with poor mental health, and greater engagement in social activism will also be associated with poor mental health.

Methods

These data were collected as part of an ongoing 2-year cohort study focused on African Americans’ mental and behavioral health in Oklahoma. The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board approved this study on 12/23/2020.

Study Procedures

Recruitment for this study started via Facebook about 10 months (March 2021) after the death of George Floyd and ended in November 2021. The targeted Facebook marketing campaign focused on Oklahoma residents only and used keywords that broadly reflected African American interests, such as favorite television shows and music genres. Recruitment ads for the cohort study appeared on the Facebook members’ web pages, and interested members clicked on the recruitment ad. Facebook members who clicked on the ad were redirected to an online survey tool to briefly screen for study eligibility. Adults were eligible to participate in this cohort study if they (a) were 18 years of age or older, (b) self-identified as Black/African American (adults who identified as Hispanic or multi-racial but also identified as Black/African American were included), and (c) lived in Oklahoma (verified by driver’s license). There were no other inclusion/exclusion criteria.

A total of 2363 adults started the screening process, and of those, 51.25% (n = 1211) completed the process. Among those who completed the screening process, 3 people were removed from the sample because they were below the age of 18, 96 adults were removed because they did not self-identify as Black/African American, 1 adult was removed because they completed the screening process twice, and 807 adults failed to upload a copy of their Oklahoma driver’s license. The remaining 304 adults (25%) met study criteria and signed an informed consent form before enrolling in the cohort study. Participants completed their first survey immediately after qualifying for the study and were compensated with a $50 gift card for survey completion. All data utilized in the current study were collected during the initial study survey.

Measures

Dependent Variable

The primary dependent variable, perceptions of mental health, was measured via a single-item measure of self-rated mental health [37], “in general, would you say your mental health is,” and included the following response options, “poor” (4), “fair” (3), “good” (2), “very good” (1), or “excellent” (0).

Independent Variable

The primary independent variables were media coverage of police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans (i.e., police brutality) and media coverage of protests (assessed via the frequency of exposure and emotional distress from exposure). The frequency of exposure to media coverage of police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans was assessed by asking participants, “How often have you watched television or social media coverage of African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers in America following the death of George Floyd?” The frequency of media coverage of protests was assessed with the question, “How often have you watched television or social media coverage of the recent protests that have taken place around the country following the death of George Floyd?” For both items, participants selected from the following response options: (0) never, (1) rarely, (2) sometimes, (3) often, and (4) always. Because very few participants reported “never” or “rarely” watching media coverage of police brutality or protests, these two options were combined into one category (i.e., “never or rarely”).

Emotional distress from watching media coverage of police-involved injuries and killings of African Americans and protests was assessed by asking two questions: (1) “Following the death of George Floyd, to what extent has watching African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers on television or social media caused you emotional distress?” (2) “Following the death of George Floyd, to what extent has watching the recent protests that have taken place around the country caused you emotional distress?” Participants selected from the following response options for both questions: (0) not at all, (1) a little, (2) somewhat, (3) a lot, and (4) extremely. The frequency of exposure to and emotional distress from these events were analyzed as separate continuous variables.

Moderator/Mediator Variable

Engagement in social activism was measured using items from the Pew Research Center [38]. We asked participants whether they had engaged in any of the following activities since the death of George Floyd (yes/no): (1) contacted a public official to express your opinion on issues related to race or racial equality, (2) contributed money to a group or organization that focused on race or racial equality, (3) attended a protest or rally that focused on issues related to race or racial equality, (4) had conversations with family or friends about issues related to race or racial equality, and (5) posted or shared content on social networking sites related to race or racial equality. A total score was created from participants’ responses (min = 0 and max = 5), and their total score was then categorized to establish three distinct levels of social engagement: low (0–1), medium (2–3), and high (4–5).

Covariates

Biological sex (males [0] and females [1]), age (years), education (high school diploma, GED, or less [0], some college, associate’s degree or technical school [1], and at least bachelor’s degree, postgraduate, or professional school [2]), annual household income ($0–$49,999 [2], $50,000–$99,999, [1] and ≥ $100,000 [0]), and homeownership (own [0], rent [1], and other [2]) were all measured via self-report and were included as covariates in analyses.

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics were generated for independent and dependent variables, moderator/mediator variable, and covariates. Moderation and mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 2 and Model 4) in SAS 9.4 [39–41]. For moderation analyses, the PROCESS macro used linear regression models to inferentially test and estimate the magnitude of the moderated effect and provided the proportion of the variance of the dependent variable attributable to the moderated effect(s). Significant interactions were probed in the PROCESS macro using the pick-a-point approach. Likewise, the PROCESS macro also used linear regression models for mediation analyses to estimate direct and indirect effects, and 10,000 bootstrap samples were used to generate bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for each model. All models tested using the PROCESS macro included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates.

Results

As shown in Table 1, most participants identified as female (n = 238, 78.6%) and were 41.9 years of age (SD = 13.5). More than half of the sample (n = 176, 58.1%) had obtained a Bachelor’s degree, 47.5% (n = 144) earned an annual household income between $0 and $49,999, and 40.6% (n = 123) owned their residence. Less than 8% (n = 23) of participants reported that their mental health was “poor,” 22.4% (n = 68) reported their mental health was fair, 35.0% (n = 106) reported their mental health was “good,” 26.1% (n = 79) reported their mental health was “very good,” and 8.9% (n = 27) reported their mental health was “excellent.”

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 304)

| Characteristic | N (%) or M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 41.9 (SD = 13.5) |

| Biological sex (% identified as female) | 238 (78.6%) |

| Educationa | |

| High school diploma, GED, or lessa | 28 (9.2%) |

| Some college, associate’s degree, or technical school | 99 (32.7%) |

| At least bachelor’s degree, postgraduate, or professional school | 176 (58.1%) |

| Annual household income | |

| $0–$49,999 | 144 (47.5%) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 99 (32.7%) |

| ≥ $100,000 | 60 (19.8%) |

| Homeownership | |

| Own | 123 (40.6%) |

| Rent | 141 (46.5%) |

| Otherb | 39 (12.9%) |

| Perceptions of mental health | |

| Excellent | 27 (8.9%) |

| Very good | 79 (26.1%) |

| Good | 106 (35.0%) |

| Fair | 68 (22.4%) |

| Poor | 23 (7.6%) |

| How often have you watched television or social media coverage of African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers in America? | |

| Never or rarelyc | 17 (5.6%) |

| Sometimes | 49 (16.2%) |

| Often | 153 (50.5%) |

| Always | 84 (27.7%) |

| To what extent has watching African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers on television or social media affected your life? | |

| Not at all | 7 (2.3%) |

| A little | 18 (6.0%) |

| Somewhat | 45 (15.1%) |

| A lot | 119 (39.8% |

| Extremely | 110 (36.8%) |

| How often have you watched television or social media coverage of the recent protests that have taken place around the country? | |

| Never or rarelyd | 22 (7.3%) |

| Sometimes | 77 (25.4%) |

| Often | 135 (44.6%) |

| Always | 69 (22.8%) |

| To what extent has watching the recent protests that have taken place around the country affected your life? | |

| Not at all | 22 (7.3%) |

| A little | 31 (10.3%) |

| Somewhat | 92 (30.7%) |

| A lot | 105 (35.0%) |

| Extremely | 50 (16.7%) |

| Following the death of George Floyd, have you ever done any of the following (% yes)? † | |

| Had conversations with family or friends about issues related to race or racial equality | 294 (97.0%) |

| Posted or shared content on social networking sites related to race or racial equality | 234 (77.2%) |

| Attended a protest or rally that focused on issues related to race or racial equality | 109 (36.0%) |

| Contributed money to a group or organization that focuses on race or racial equality | 106 (35.0%) |

| Contacted a public official to express your opinion on issues related to race or racial equality | 82 (27.1%) |

| Social activism†† | |

| Low | 55 (18.2%) |

| Medium | 162 (53.5%) |

| High | 86 (28.4%) |

All variables had less than 5% missing data

†A total score was created from participants’ responses (min = 0 and max = 5), and their total score was then categorized to establish three distinct levels of engagement in social activism: low (0–1), medium (2–3), and high (4–5)

aDid not finish high school (n = 2), and high school or GED (n = 26)

b “Other” was defined as living with parents (n = 27) or other living arrangements (n = 12)

cNever (n = 4), and rarely (n = 13)

dNever (n = 3), and rarely (n = 19)

Notably, at least 94.4% (n = 286) of the sample had “sometimes” watched television or social media coverage of African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers, and 91.7% (n = 274) reported they were at least “somewhat” affected by watching coverage of these incidents. Similarly, at least 92.8% (n = 281) of participants watched media coverage of protests and demonstrations “sometimes,” and 82.4% (n = 247) of participants were at least “somewhat” affected by viewing these incidents. Since the death of George Floyd, (1) 97.0% (n = 294) of participants had conversations with family or friends about issues related to race or racial equality, (2) 77.2% (n = 234) posted or shared content on social networking sites related to race or racial equality, (3) 36.0% (n = 109) attended a protest or rally that focused on issues related to race or racial equality, (4) 35.0% (n = 106) contributed money to a group or organization that focused on race or racial equality, and (5) 27.1% (n = 82) contacted a public official to express their opinion on issues related to race or racial equality. Based on their pattern of responses to these questions, 18.1% (n = 55) of participants engaged in a low level of social activism, 53.5% (n = 162) engaged in a moderate level of social activism, and 28.4% (n = 86) engaged in a high level of social activism.

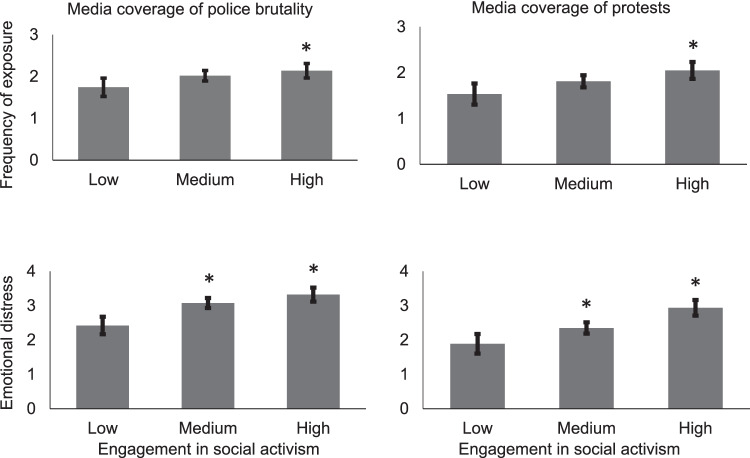

Frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality (r = 0.027, p = 0.789) and protests (r = 0.003, p = 0.963) was not correlated with perceptions of mental health. Emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality (r = 0.100, p = 0.085) and protests (r = 0.092, p = 0.110) was also not correlated with perceptions of mental health. Notably, a significant association between independent and dependent variables was not required to establish evidence of moderation or mediation [39]. However, as shown in Fig. 1, there were significant differences in the frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests based on the level of social activism. In particular, compared with participants who engaged in low levels of social activism, participants who engaged in high levels of social activism also viewed more media coverage of police brutality (2.139 vs. 1.743, p = 0.011) and protests (2.049 vs. 1.532, p = 0.001). Further, there were also significant differences in the amount of emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests based on the level of social activism. Compared with participants who engaged in low levels of social activism, participants who engaged in medium or high levels of social activism were also more emotionally distressed from watching media coverage of these events (all p-values < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Differences in the frequency of exposure to (top half) and emotional distress (bottom half) from media coverage of police brutality (left side) and protests (right side) based on the level of engagement in social activism. Low engagement in social activism is the reference category. The models included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates. *p < .05

Moderation Analyses

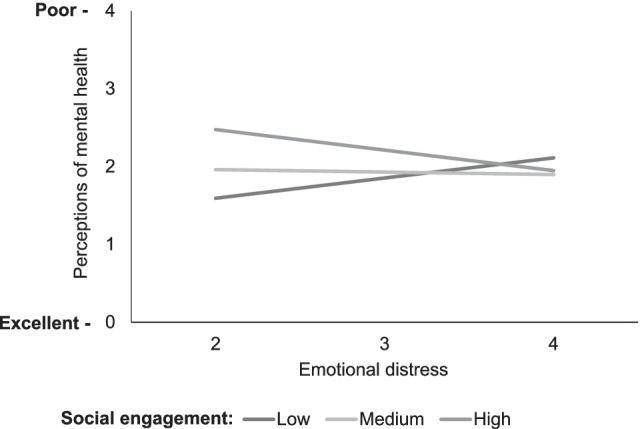

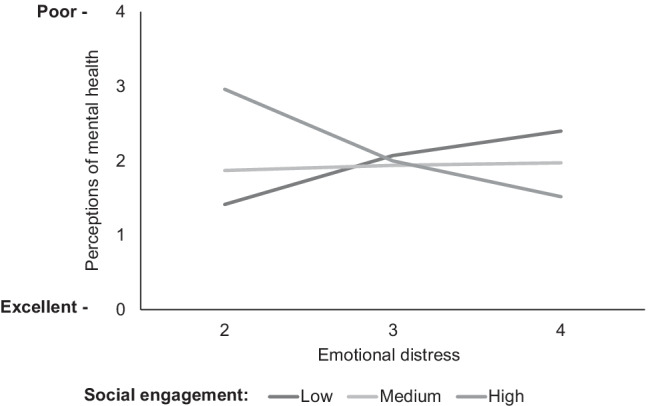

The associations of frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests with perceptions of mental health did not vary by the level of engagement in social activism (data not shown). However, the association of emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality with perceptions of mental health did vary by the level of engagement in social activism. As shown in Fig. 2, post hoc comparisons using the pick-a-point approach showed that greater emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality was significantly associated with worse perceptions of mental health when engagement in social activism was low (B = 0.259, SE = 0.119, p = 0.030). This significant interaction alone explained 1.2% of the total variance in perceptions of mental health (entire model, R2: 12.9%). Likewise, the association between emotional distress from watching media coverage of protests and perceptions of mental health also varied by engagement in social activism. As shown in Fig. 3, post hoc comparisons showed that greater emotional distress from watching media coverage of protests was significantly associated with worse perceptions of mental health when engagement in social activism was low (B = 0.328, SE = 0.117, p = 0.005), and was associated with better perceptions of mental health when engagement in social activism was high (B = − 0.481, SE = 0.190, p = 0.012). These significant interactions alone explained 2.7% of the total variance in perceptions of mental health (entire model, R2: 14.3%).

Fig. 2.

The association of emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality with the perceptions of mental health varies by the level of engagement in social activism. The model included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates

Fig. 3.

The association of emotional distress from watching media coverage of protests with the perceptions of mental health varies by the level of engagement in social activism. The model included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates

Mediation Analyses

Mediation analyses (see Table 2) demonstrated that greater frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality (B = 0.027 [95% CI = 0.003, 0.065]) and protests (B = 0.034 [95% CI = 0.005, 0.073]) was indirectly associated with worse perceptions of mental health through increased engagement in social activism. Likewise (see Table 3), greater emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality (B = 0.038 [95% CI = 0.002, 0.080]) and protests (B = 0.037 [95% CI = 0.001, 0.077]) was indirectly associated with worse perceptions of mental health through increased engagement in social activism. In both mediation analyses, greater engagement in social activism (i.e., mediator) was associated with worse perceptions of mental health.

Table 2.

Mediation models linking frequency of exposure to media coverage of African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers and protests with perceptions of mental health

| Mediator | X → M (a path) | M → Y (b path) | X → Y (c′ path/direct effect) | X → M → Y (ab path/indirect effect) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | 95% CIa | |

| Model 1: Media coverage of police brutality | ||||||||

| Engagement in social activism | 0.125 (0.047) | .008 | 0.220 (0.090) | .016 | 0.005 (0.074) | .943 | 0.027 (0.016) | 0.003, 0.065 |

| Model 2: Media coverage of protests | ||||||||

| Engagement in social activism | 0.151 (0.044) | .001 | 0.223 (0.091) | .015 | − 0.009 (0.070) | .898 | 0.034 (0.018) | 0.005, 0.073 |

X = independent variable (i.e., frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality [Model 1] and frequency of exposure to media coverage of protests [Model 2]), M = mediator (i.e., level of engagement in social activism), Y = dependent variable (i.e., perceptions of mental health). The models included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates

aBias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (10,000 bootstrap samples)

Table 3.

Mediation models linking emotional distress from watching media coverage of African Americans being seriously injured or killed by police officers and protests with perceptions of mental health

| Mediator | X → M (a path) | M → Y (b path) | X → Y (c′ path/direct effect) | X → M → Y (ab path/indirect effect) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | 95% CIa | |

| Model 1: Media coverage of police brutality | ||||||||

| Engagement in social activism | 0.196 (0.038) | < .001 | 0.195 (0.094) | .039 | 0.062 (0.064) | .334 | 0.038 (0.021) | 0.002, 0.080 |

| Model 2: Media coverage of protests | ||||||||

| Engagement in social activism | 0.192 (0.033) | < .001 | 0.192 (0.095) | .044 | 0.058 (0.057) | .308 | 0.037 (0.019) | 0.001, 0.077 |

X = independent variable (i.e., emotional distress from watching exposure to media coverage of police brutality [Model 1] and emotional distress from watching exposure to media coverage of protests [Model 2]), M = mediator (i.e., level of engagement in social activism), Y = dependent variable (i.e., perceptions of mental health). The models included sex, age, education, household income, and homeownership as covariates

aBias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (10,000 bootstrap samples)

Sensitivity Analysis

The frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality was positively correlated with the frequency of exposure to media coverage of protests (r = 0.603, p < 0.001), Likewise, emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality was also positively correlated with emotional distress from watching media coverage of protests (r = 0.642, p < 0.001). These variables were combined to measure the overall frequency of exposure and emotional distress, respectively. Moderation and mediation analyses were repeated using these combined variables. Moderation analysis showed that the association of the overall frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests with perceptions of mental health did not vary by the level of engagement in social activism. However, the association of overall emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests with perceptions of mental health did vary by the level of engagement in social activism. Post hoc comparisons showed that greater overall emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests was significantly associated with worse perceptions of mental health when engagement in social activism was low (B = 0.338, SE = 0.126, p = 0.001) and was associated with better perceptions of mental health when social activism was high (B = − 0.431, SE = 0.212, p = 0.043). These significant interactions alone explained 1.9% of the total variance in perceptions of mental health (entire model, R2: 13.7%).

Mediation analyses also demonstrated that the overall frequency of exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests was indirectly associated with worse perceptions of mental health through increased engagement in social activism (B = 0.038 [95% CI = 0.006, 0.082]). However, overall emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests was not indirectly associated with perceptions of mental health through social activism (B = 0.043 [95% CI = − 0.002, 0.092]).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore social activism as a potential moderator and mediator of the association of media exposure to police brutality and protests with perceptions of mental health using the “competing models” approach [35, 36]. When social activism was conceptualized as a moderator, the data suggested that being greatly affected by watching media coverage of police brutality and protests was associated with worse perceptions of mental health when African Americans engaged in a minimal level of social activism. In contrast, being greatly affected by media coverage of protests was associated with better mental health when African Americans engaged in high levels of social activism. When social activism was conceptualized as a mediator, the data suggested that although African Americans were more socially engaged after being exposed and emotionally impacted by media coverage of police brutality or protests, their increased engagement may have contributed to worse perceptions of mental health. Overall, study findings suggest complex relations between engagement in social activism, exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests, and perceptions of mental health among African Americans.

To understand findings within the context of the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, between May 26 and August 30 of 2020, over 7750 protests occurred across the USA [4], and there were several other incidents of African Americans being injured or killed by police officers that received national attention during that time, such as the death of Breonna Taylor and the shooting of Jacob Blake. Some African Americans may have been deeply affected by these events perhaps because they emphasized or identified with the victims of police brutality and/or demonstrators fighting for important issues in their community [32, 42]. However, even though they were deeply affected by these events, some African Americans may have chosen not to engage in social activism, which may have contributed to worse perceptions of mental health. It may be important to consider whether African Americans should be encouraged to engage in activism to improve perceptions of their own mental health. These acts of social activism may not require a large personal commitment, such as attending a protest or sending a donation to a grassroots organization, but could be as small as having a conversation with friends or family members. Previous research has shown that activism may illicit feelings of empowerment and identification with one’s racial background [26], improving perceptions of mental health. This assertion is supported by a recent study that showed that African Americans who expressed low levels of BLM support reported worse depressive symptoms when exposed to racial discrimination than African Americans who expressed high levels of BLM support [23].

However, the seemingly dualistic role of social activism serving as an indirect source of poor mental health is not unexpected. Watson-Singleton et al. found that engagement in BLM activities, such as participating in BLM-sponsored protests or sit-ins, was associated with depression [23]. Also, previous research has shown that African Americans who are more engaged in social activism are more cognizant of microaggressions and vulnerable to stress and anxiety symptoms than African Americans who are less engaged in social activism [24]. In addition, sustained activism tends to increase feelings of hopelessness and frustration, especially if social change is slow or nonexistent [28]. In the case of police reform, a few months after the death of George Floyd, Americans only slightly favored spending more on policing in their area compared with decreasing funding (31% vs. 26%), but by 2021, the American public was overwhelmingly in support of spending more on police in their area (47% vs. 15%) [43]. This significant shift in public opinion regarding police funding is counter to the efforts made by many social movements to “defund the police” after George Floyd’s death [44], and setbacks such as these may contribute to worse perceptions of mental health among those who are engaged in social activism. African Americans engaged in social activism may be particularly vulnerable to these setbacks because they are often directly affected by policing in their communities [45].

Overall, the findings suggest that engagement in social activism may protect against and even contribute to worse perceptions of mental health after being exposed to and emotionally impacted by media coverage of police brutality and protests. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously because this study has several notable limitations. First, data analyzed from cross-sectional studies are not ideal for addressing moderation and mediation because of causal ordering and temporality issues. We strongly suggest that future research use the meta-theoretical paradigm outlined by Karazsia and Berlin to conduct a more rigorous and definitive analysis of the viability of social activism serving as a moderator and mediator [34]. Second, these data are from a non-random sample recruited primarily through social media, and only about half of the adults who clicked on the survey link finished the screener. In addition, 807 adults who stated they were African American and lived in Oklahoma did not provide a copy of their driver’s license, which excluded them from participating in the study. This may have prevented some older African Americans from participating in this study because older adults tend to have fewer internet skills, such as capturing and uploading an image to the Internet, than younger adults [46]. Relatedly, African Americans who participated in this study tended to identify as female, and be highly educated and wealthy, which does not reflect the overall demographics of African Americans in Oklahoma. Women tend to report more emotional distress than men [47], and women and adults with higher education are more likely to engage in social activism than men and adults with less education [48]. Therefore, the study findings may reflect the perspective of African Americans who were deeply affected by the watching media coverage of police brutality and protests and were more willing to participate in this research study to voice their opinion about this important social issue. Third, recruitment for this study occurred for at least 9 months, and participants provided their survey responses immediately after being recruited. Social activism and exposure to media coverage of police brutality and protests are time-sensitive, and since 2020, public support for BLM has weakened, and law enforcement reform is no longer a top public issue [43]. Social activism likely plays a more significant role in mental well-being closer to the time of the event rather than many months after [15, 16]. Fourth, the measure for perceptions of mental health was based on a one-item self-rated scale, and while related to poor mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety, does not fully assess symptoms of psychological distress and may better reflect overall mental well-being [37]. Last, the survey question for media coverage of protests and demonstrations was not specific to protests about law enforcement reform and may have also assessed exposure to other protests that have occurred since the death of George Floyd, including protests related to COVID-19 and the 2020 US Election [4].

In summary, the death of George Floyd was watched over 1.4 billion times on Twitter alone and reinvigorated social movements to address racial equality within the USA. On the one hand, findings from this study suggested that African Americans who experienced emotional distress from watching media coverage of police brutality and protests but engaged in minimal social activism reported worse perceptions of mental health, and those who engaged in high levels of social activism had better perceptions of mental health. On the other hand, increased engagement in social activism after being exposed to and emotionally impacted by media coverage of police brutality and protests may be associated with worse perceptions of mental health. More research is needed to improve our understanding of how and when African Americans can engage in social activism in response to media coverage of police brutality and protests to ensure they can contribute to important racial and social issues without increasing the risk for further trauma and psychological distress.

Author Contribution

AA designed the parent study. AA formulated the research questions and hypotheses and conducted the secondary data analyses for this study. AA also prepared the 1st draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the 1st draft and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was primarily supported by Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (https://tset.ok.gov/) contract number R21-02. Manuscript preparation was additionally supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant number 1K01MD015295-01A1) and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520 awarded to the Stephenson Cancer Center.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments (or comparable ethical standards). The study procedures were also approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Oklahoma University Health Sciences Center.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.1. Okri B. “I can’t breathe”: Why George Floyd’s words reverberate around the world. J Transnatl Am Stud [Internet]. 2021;12. Available from: 10.5070/T812154907

- 2.Anderson M, Barthel M, Perrin A, Vogels E. #BlackLivesMatter hashtag surges on Twitter after George Floyd’s death | Pew Research Center. Pew Res. Cent. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/10/blacklivesmatter-surges-on-twitter-after-george-floyds-death/

- 3.1. Blake S. Why The George Floyd protests feel different — lots and lots of mobile video. dot.LA. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.dot.la/george-floyd-video-2646171522.html?utm_campaign=post-teaser&utm_content=i87yytb3

- 4.Armed Conflict Location & Event Data. A year of racial justice protests: key trends in demonstrations supporting the BLM movement. United Kingdom; 2021. Available from: https://www.acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ACLED_Report_A-Year-of-Racial-Justice-Protests_May2021.pdf

- 5.1. Kingson JA. Exclusive: $1 billion-plus riot damage is most expensive in insurance history. Axios. 2020 [cited 2022 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.axios.com/riots-cost-property-damage-276c9bcc-a455-4067-b06a-66f9db4cea9c.html

- 6.Eichstaedt JC, Sherman GT, Giorgi S, Roberts SO, Reynolds ME, Ungar LH, et al. The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George Floyd on the US population. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118:e2109139118. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.2109139118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and Black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:662–5. Available from: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Waldron IRG. The wounds that do not heal: Black expendability and the traumatizing aftereffects of anti-Black police violence. Equal Divers Incl An Int J. 2020;40:29–40. Available from: 10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0175/full/html.

- 9.Neria Y, Sullivan GM. Understanding the mental health effects of indirect exposure to mass trauma through the media. JAMA. 2011;306:1374. Available from: 10.1001/jama.2011.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lowe SR, Galea S. The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017;18:62–82. Available from: 10.1177/1524838015591572. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Linley PA, Joseph S, Cooper R, Harris S, Meyer C. Positive and negative changes following vicarious exposure to the September 11 terrorist attacks. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:481–5. Available from: 10.1023/A%3A1025710528209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Suvak M, Maguen S, Litz BT, Silver RC, Holman EA. Indirect exposure to the September 11 terrorist attacks: does symptom structure resemble PTSD? J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:30–9. Available from: 10.1002/jts.20289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Tynes BM, Willis HA, Stewart AM, Hamilton MW. Race-related traumatic events online and mental health among adolescents of color. J Adolesc Health. Elsevier Inc.; 2019;65:371–7. Available from: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.McLeod MN, Heller D, Manze MG, Echeverria SE. Police interactions and the mental health of Black Americans: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:10–27. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. Elsevier Ltd; 2018;392:302–10. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.1. Curtis DS, Washburn T, Lee H, Smith KR, Kim J, Martz CD, et al. Highly public anti-Black violence is associated with poor mental health days for Black Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.2019624118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Reny T, Newman B. The opinion-mobilizing effect of social protest against police violence: evidence from the 2020 George Floyd protests. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2021;115:1499–507. Available from: 10.1017/S0003055421000460

- 18.Nguyen TT, Criss S, Michaels EK, Cross RI, Michaels JS, Dwivedi P, et al. Progress and push-back: how the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd impacted public discourse on race and racism on Twitter. SSM-Popul Health. 2021;15:100922. Available from: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Poliak A, Leas EC, Nobles AL, Dredze M, et al. Quantifying public interest in police reforms by mining Internet search data following George Floyd’s death. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e22574. Available from: 10.2196/22574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Canady VA. Groups mark Floyd anniversary with call for equitable practices. Ment Health Wkly. 2021;31:5–5. Available from: 10.1002/mhw.32811.

- 21.Goulka J, Del Pozo B, Beletsky L. From public safety to public health: re-envisioning the goals and methods of policing. J Community Saf Well-Being. 2021;6:22–7. Available from: 10.35502/jcswb.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Schultz D. The $2 billion-plus price of injustice: a methodological map for police reform in the George Floyd era. Minnesota J Law Inequal. 2021; Available from: 10.24926/25730037.637

- 23.Watson-Singleton NN, Mekawi Y, Wilkins K V., Jatta IF. Racism’s effect on depressive symptoms: examining perseverative cognition and Black Lives Matter activism as moderators. J Couns Psychol. 2021;68:27–37. Available from: 10.1037/cou0000436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hope EC, Velez G, Offidani-Bertrand C, Keels M, Durkee MI. Political activism and mental health among Black and Latinx college students. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2018;24:26–39. Available from: 10.1037/cdp0000144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bergstresser SM, Brown IS, Colesante A. Political engagement as an element of social recovery: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:819–21. Available from: 10.1176/appi.ps.004142012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ballard PJ, Muscatell KA, Hoyt LT, Flores AJ, Mendes WB. An experimental laboratory examination of the psychological and physiological effects of civic empowerment: a novel methodological approach. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2021;50:118–42. Available from: 10.1177/0899764020933360.

- 27.Szymanski DM, Goates JD, Strauss Swanson C. LGBQ activism and positive psychological functioning: the roles of meaning, community connection, and coping. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2021; Available from: 10.1037/sgd0000499.

- 28.Vestergren S, Drury J, Chiriac EH. The biographical consequences of protest and activism: a systematic review and a new typology. Soc Mov Stud. 2017;16:203–21. Available from: 10.1080/14742837.2016.1252665.

- 29.1. Dergić V, Dähnke I, Nartova N, Shilova A, Matos R, Carneiro A. When visibility becomes political: visibility and stigmatisation of young people. J Youth Stud. 2022;1–17. Available from: 10.1080/13676261.2021.2022109

- 30.Hope EC, Cryer-Coupet QR, Stokes MN. Race-related stress, racial identity, and activism among young Black men: a person-centered approach. Dev Psychol. 2020;56:1484–95. Available from: 10.1037/dev0000836. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.O’Leary N, Green S. From invisible to conspicuous: the rise of victim activism in the politics of justice. Victimology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 159–83. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-030-42288-2_7.

- 32.Krueger NT, Garba R, Stone-Sabali S, Cokley KO, Bailey M. African American activism: the predictive role of race related stress, racial identity, and social justice beliefs. J Black Psychol. 2021. Available from: 10.1177/0095798420984660

- 33.Collins RN, Mandel DR, Schywiola SS. Political identity over personal impact: early U.S. reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12. Available from: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.607639/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Karazsia BT, Berlin KS. Can a mediator moderate? Considering the role of time and change in the mediator-moderator distinction. Behav Ther. Elsevier Ltd; 2018;49:12–20. Available from: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Rose BM, Holmbeck GN, Coakley RM, Frank EA. Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:58–67. Available from: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.D’Lima GM, Pearson MR, Kelley ML. Protective behavioral strategies as a mediator and moderator of the relationship between self-regulation and alcohol-related consequences in first-year college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:330–7. Available from: 10.1037/a0026942. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ahmad F, Jhajj AK, Stewart DE, Burghardt M, Bierman AS. Single item measures of self-rated mental health: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:398. Available from: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Center PR. The public, the political system and American democracy. 2018. Available from: http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/01/11/publics-globally-want-unbiased-news-coverage-but-are-divided-on-whether-their-news-media-deliver/.

- 39.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2015;50:1–22. Available from: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.SAS . Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide. 2. Cary: SAS Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fabi S, Weber LA, Leuthold H. Empathic concern and personal distress depend on situational but not dispositional factors. Karl A, editor. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225102. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Parker K, Hurst K. Growing share of Americans say they want more spending on police in their area. Pew Res Cent. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/10/26/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-want-more-spending-on-police-in-their-area/.

- 44.Cobbina-Dungy JE, Jones-Brown D. Too much policing: why calls are made to defund the police. Punishment Soc. 2021;146247452110456. Available from: 10.1177/14624745211045652.

- 45.Owusu-Bempah A. Race and policing in historical context: dehumanization and the policing of Black people in the 21st century. Theor Criminol. 2017;21:23–34. Available from: 10.1177/1362480616677493.

- 46.Hargittai E, Piper AM, Morris MR. From internet access to internet skills: digital inequality among older adults. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2019;18:881–890. doi: 10.1007/s10209-018-0617-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almeida DM, Kessler RC. Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:670–680. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong H, Kim Y. What makes people engage in civic activism on social media? Online Inf Rev. 2021;45:562–576. doi: 10.1108/OIR-03-2020-0105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]