Abstract

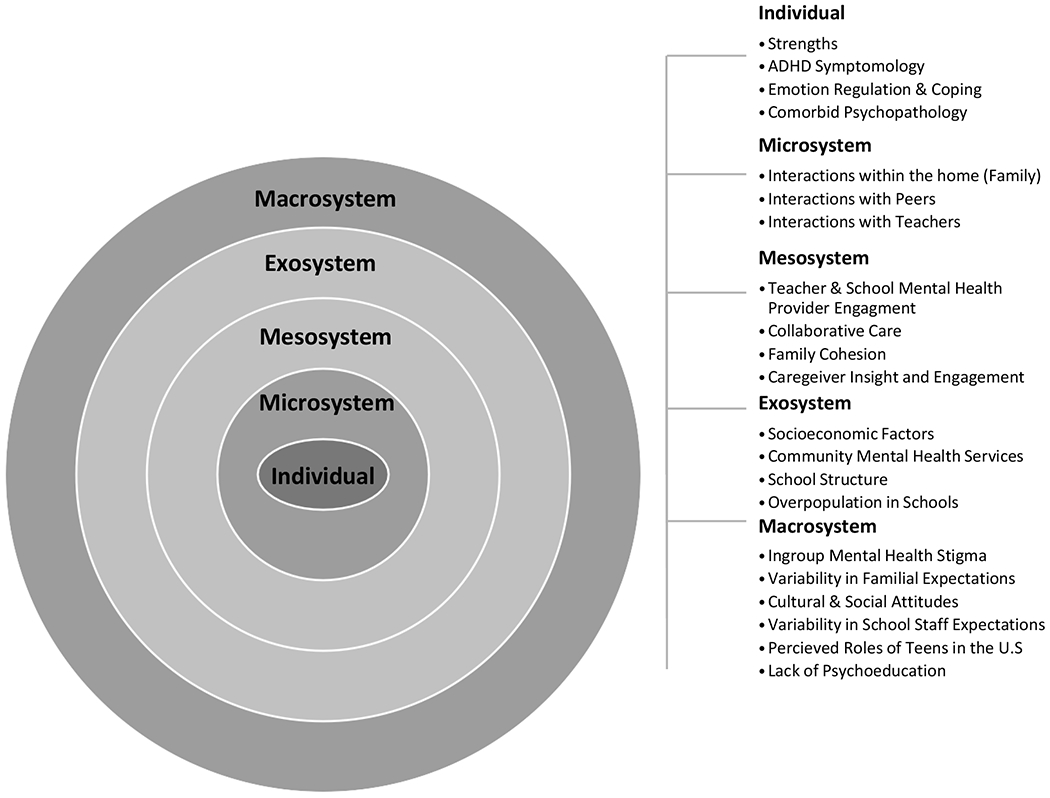

The high school years are a challenging developmental period for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), their families, and those who work with them in the school system. Moreover, racially minoritized families and schools in low-resource, urban settings often experience additional adverse experiences that can make access to evidence-based mental health care particularly difficult. This qualitative investigation into the experiences of Black high school students with ADHD, their caregivers, teachers, and school mental health providers (SMHPs) aimed to understand this community’s experiences with ADHD across development and to explore the barriers/facilitators to adequate services. Through focus group interviews with stakeholders (i.e., 6 adolescents with a diagnosis of ADHD, 5 caregivers of adolescents with ADHD, 6 teachers, 5 school mental health providers), themes emerged related to (1) developmental changes observed in ADHD presentation in high school students and (2) contextual factors (including barriers/facilitators to optimal school and home functioning). These themes led to the development of an ecological model that show various contextual factors influencing the experiences of Black adolescents with ADHD in under-resourced urban public high schools (e.g., adolescents’ coping strategies, caregiver involvement, teacher burden or lack of ADHD-knowledge, socioeconomic status, access to care). This qualitative study represents the first step of a treatment development project assessing the implementation of a depression prevention intervention for Black adolescents with ADHD in urban public-school settings. Clinical implications (e.g., coordination of care between home and schools, increasing attention to social determinants of health, ensuring culturally competent discussion of ADHD and its treatment) are discussed.

Urban high schools serving primarily racially minoritized (e.g., Black youth) and/or low-income families are often faced with insufficient resources, frequent staff turnover, suboptimal learning conditions, and safety concerns (Keigher, 2010; Osher et al., 2014). Within these schools, there are certain groups of adolescents who may be particularly sensitive to the environmental stressors typical of under-resourced, urban school conditions. Adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) represent one such group.

The transition to high school introduces unique challenges for adolescents in general, but particularly so for adolescents with ADHD whose educational/social impairment makes it even more difficult to meet increased academic and interpersonal demands (Brocki & Bohlin, 2006; Litner, 2003). ADHD affects up to 9% of children (Danielson et al., 2018), a majority of which continue to display impairment into adolescence and adulthood (Sibley et al., 2017). Adolescence is an important intervention point, given that youth with ADHD at this stage in development struggle with the aforementioned academic and social demands (Brocki & Bohlin, 2006; Litner, 2003) and subsequently experience greater risk for elevated depressive symptoms, suicide attempts (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010), and substance use (Molina & Pelham, 2003). However, there is a notable paucity of research focusing on clinical issues associated with ADHD in Black and low-income youth (Slobodin & Masalha, 2020).

Though ADHD prevalence is consistent across racial groups (Caldwell et al., 2016), Black children are 69% less likely to receive a diagnosis for ADHD compared to White youth (Morgan et al., 2014). Beyond inadequate screening and diagnosis, Black youth are also less likely to receive evidence-based services for ADHD (DuPaul et al., 2019) and be retained in care than their White counterparts (McKay et al., 2001; Whitaker et al., 2018). Understanding the experiences of Black adolescents with ADHD in an urban environment (e.g., their presentation, coping experiences) as well as barriers to care for Black youth with ADHD therefore represents an understudied and critical public health concern.

In addition to individual-level factors (e.g., ADHD) that affect the experiences and trajectories of Black youth, a complete understanding requires examining the larger, structural context within which these individual-level factors occur. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model may help to guide our understanding of the experiences of Black adolescents with ADHD attending low-income urban high schools. Critically, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) model contextualizes the overarching effects of Individual characteristics, family interactions, environmental (e.g., school), and societal-level influences. On the individual level, various factors may affect the experience of ADHD in Black, urban youth. For instance, research has indicated that adolescents with severe symptom profiles had worse outcomes (including antisocial behavior, juvenile justice system involvement, and unemployment) than adolescents without or with subclinical symptoms of ADHD (Sasser et al., 2016). Prior studies have demonstrated that adolescents with ADHD are more likely than their peers without ADHD to experience difficulties in emotion regulation (Seymour et al., 2014) and to employ maladaptive coping strategies, (e.g., Harty et al., 2017; Molina et al., 2005). Similar patterns of negative coping behavior have been documented among adolescents exposed to poverty (Kim et al., 2016). However, such examinations have yet to be conducted among low-income Black youth with ADHD in the unique context of under-resourced urban schools.

In addition to potential individual factors, various environmental factors can impact the experience of ADHD, coping strategies, and receipt of services for Black youth. The family is one such influential factor. Families who live in urban neighborhoods are often subject to economic hardships which, in combination with uncontrolled ADHD, can attribute to family adversity (Thapar et al., 2013). This can be further complicated by parental mental illness, large family sizes, and trauma (Brown et al., 2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are one factor that could be particularly prevalent among this population; youth with ADHD are more likely to have experienced an ACE than youth without ADHD (Crouch et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2017). Additionally, in a longitudinal study, inconsistent parenting practices and family adversity were linked with severity of adolescents’ inattentive symptom profiles (Sasser et al., 2016), though this has not been explored specifically in Black youth with ADHD.

Further, Black parents and guardians may conceptualize ADHD and seek care for their children with ADHD in various ways. A series of studies by McKay et al. (2001) examined child, family, and environmental correlates of service seeking and service use among urban and primarily low-income youth and their families. Factors such as parenting traits, attitudes about mental health services, family stress, certain child psychopathology symptoms, and family make-up were predictors of families initiating or maintaining service use beyond demographics alone (McKay et al., 2001). Further, in a qualitative study of Black families with a child recently diagnosed with ADHD, various beliefs regarding the etiology of ADHD emerged among parents. These included views of ADHD as a medical issue with immediate resolution through prescribed medication, a behavioral issue with or without biological underpinnings, or a school-related issue with a sense of forced compliance to services (dosReis et al., 2007). These types of processes and attitudes may be additional considerations that contribute to how Black families navigate service seeking and what types of care they pursue for their child with ADHD.

Outside of the family unit, school context can also have an impact on outcomes of youth with ADHD. At the classroom level, studies show that youth with ADHD have a worse student-teacher ‘working alliance’ (i.e., the emotional and collaborative learning connection between students and teachers) compared to their peers without ADHD (Rogers et al., 2015). However, among students with ADHD, those with stronger student-teacher bonds had increased academic motivation (Rogers et al., 2015). In a qualitative study, Black parents of children with ADHD expressed frustration with the shortage of school-based educational services, qualified counselors, and financial resources for children with behavioral issues in low-income areas. Parents cited teachers’ lack of patience, unfavorable student-teacher ratios, and inadequate administrative systems as contributing to the ineffective management of their children’s behavioral problems (Olaniyan et al., 2007). School-level factors can exacerbate ADHD-related difficulties through multifarious avenues; thus, it is important to understand the lived impact of these factors from the perspectives of students, caregivers, and school mental health providers (SMHPs).

Sociocultural factors can exert considerable influence on the presentation, perception, and treatment of Black adolescents with ADHD. For example, the ‘achievement gap’—referring to disparities in achievement between Black and White students—has remained largely unchanged since the 1970s (Merolla & Jackson, 2019) and is pronounced in states with higher levels of racial segregation in schools (Condron et al., 2013), suggesting a pattern whereby fewer resources are allocated to schools where the majority of students are Black (Merolla & Jackson, 2019). Relatedly, Black students are more likely to face disproportionate disciplinary action for externalizing behaviors in relation to their White peers (e.g., suspensions, expulsions), thus negatively impacting their achievement (Sullivan et al., 2013). Exposure to such racial discrimination and other adverse experiences (e.g., poverty, neighborhood violence, lack of health insurance) places low-income Black youth attending urban schools at substantial risk for behavioral and mental health difficulties (Cave et al., 2020). This is likely to be exacerbated among youth with ADHD who often need additional supports to be successful (Pfiffner & DuPaul, 2015). For instance, in one study of low-income Black male youth, which found that living in poverty and having ADHD was related to academic failure, higher rates of punishment, and an increase in disruptive behaviors (Tucker & Dixon, 2009). Moreover, mental health treatment is often stigmatized in the Black community. Many Black parents fear social stigma from family and friends or believe mental health should be a private matter, and may thus forgo treatment seeking for their child (Bailey et al., 2010; Thapar et al., 2013).

In sum, it is important to capture the lived experiences of low-income Black adolescents with ADHD and of individuals who support, educate, and parent these youth to improve our understanding of challenges related to treatment utilization, symptom management, and coping skills (Behnken et al., 2014). Capturing the experiences of Black youth with ADHD, their caregivers, teachers, and SMHPs in the uniquely challenging environment of an under-resourced, urban school system presents the opportunity to understand research and clinical issues within this population and inform how treatments can be conceptualized, adapted, and disseminated. Therefore, we conducted focus group interviews to document the perspectives of high school-aged Black adolescents with ADHD, their caregivers, teachers, and SMHPs in low-resource, urban schools aiming to: (1) better understand these stakeholders’ overall experience with ADHD across development, including positive/negative coping strategies for managing ADHD symptomatology; and (2) learn more about barriers and facilitators to adequate care to guide future development of treatment that promotes greater access and uptake of services. To this end, we initiated a qualitative exploration into this critical yet understudied area of research.

Methods

The present study examined focus group interviews conducted as part of the first phase of a National Institute of Mental Health-funded, school-based, randomized controlled trial to reduce the risk of depression among adolescents with ADHD in a low-resource, urban school district [MH117086; MPI Meinzer & Chronis-Tuscano]. This study was preregistered via ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04104841). This study received IRB approval from both the University of Maryland and IRB for the Baltimor City Schools system. Prior to the start of this study, the research team developed relationships with these high schools by providing mental health consultation and pro-bono mental health treatment groups.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Focus group participants were recruited from two public urban high schools in a mid-Atlantic school district where approximately 78.6% of students are Black (Baltimore City Schools, 2019). Recruitment of adolescents with ADHD and their caregivers occurred predominantly via referrals from SMHPs. Other methods of caregiver and adolescent recruitment included the use of flyers and sign-up sheets placed in classrooms or distributed by study staff. Teachers and SMHPs were recruited through flyers circulated in staff mailboxes, in-school announcements, and word of mouth. Eligibility criteria for adolescents included a prior diagnosis of ADHD and enrollment at a participating high school. Caregivers of adolescents who met these criteria were also eligible to participate.

Participants and Procedures

Our sample consisted of a total of 22 participants (77% Black, 23% White): Six adolescents with an already established diagnosis of ADHD (100% Black), five caregivers (100% Black), six teachers (66.7% Black, 33.3% White), and five SMHPs (40% Black, 60% White). Recruitment was conducted per the gold standard for focus groups with group consisting of the recommended five to six participants (Krueger & Casey, 2000). Focus groups met for 1-1.5-hour discussions scheduled at different times of the day to optimize convenience to participants. The focus groups took place at participating high schools or nearby community venues (e.g., public libraries) and were conducted in private rooms to ensure confidentiality.

Prior to focus groups, adult participants signed informed consent. For adolescents under age 18, informed consent from a parent or guardian was required in addition to the adolescents’ assent. Those 18 years or over consented for themselves. Focus groups were conducted by one of the principal investigators and by a post-baccalaureate project coordinator. The principal investigators developed a semi-structured interview guide which was used to ask fully open-ended questions followed by probes and then moderated or supervised focus group discussions. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed to ensure accurate representation of stakeholder feedback. Participants were paid $25.

The adolescent focus group concentrated on ADHD- and mood-related difficulties and motivation for treatment. Though the focus of the grant under which the current study originated was on reducing depression among adolescents with ADHD, questions were open ended and did not prompt participants to report on mood-related issues specifically but rather difficulties and impairment in general. Example questions included “What are the things that you find most difficult/frustrating in your life?” and “What changes would you most like to see in your life?” Caregivers were interviewed about their experiences parenting adolescents with ADHD and feasibility of caregiver involvement in treatment. Example questions included: “What types of problems does your teen with ADHD struggle with?”; and “What changes would you most want to see in your teen with ADHD?” The teacher focus group elicited feedback about difficulties experienced teaching students with ADHD, effective engagement strategies for students with ADHD, and issues surrounding the acceptability of a school-based treatment program (e.g., ways to minimize lost instruction time to participating students, feasibility of involving teachers in treatment). The SMHP focus group examined challenges in providing services to adolescents with ADHD and possible solutions, issues typically addressed with adolescents with ADHD, potential barriers to implementation (e.g., anticipated adolescent/caregiver engagement), and ways to improve feasibility of implementation. Questions posed to SMHPs included “For what primary concerns do students with ADHD most often come to seek school-based services?” and “What are common challenges you’ve experienced in providing treatment for students with ADHD?.”

These interviews provided a comprehensive and rich picture of the overall experience of youth with ADHD and their experiences across settings during the high school years from an array of perspectives. Though investigating the summative experience of high school aged adolescents in urban environments was not the sole aim of the focus groups, participants shared deeply insightful experiences about this phase of life that extended beyond practical considerations for treatment development.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were entered into NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International, 2020) qualitative analysis software. Two project coordinators who participated in study recruitment, data collection and relationship building between the research team and community, and one doctoral student with qualitative research training and experience reviewed the transcripts and developed a codebook that was refined iteratively through an open coding process across caregiver, child, and school staff focus groups. This comprehensive process ensured that the codebook was appropriate for the entire dataset. Discrepancies during the coding process were resolved through consensus. Once a codebook was finalized, two analysts coded the full data set using NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International, 2020). The team of three analysts who developed the codebook analyzed the coded data for themes, an inductive approach that allowed for patterns in the text to be determined from the words of the participants themselves and with no a priori hypotheses. As themes “emerged” from the data, the analysts selected quotations from the text that captured the defined themes richly and did not require contextual knowledge from the focus groups to comprehend (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Miles et al., 2014).

Results

Two major themes emerged regarding the experience of the high school years in a low-income, urban setting from the perspectives of youth with ADHD, their parents, and school staff: (1) developmental changes affecting the presentation of ADHD among Black high school students, (2) contextual factors influencing Black adolescents with ADHD.

Developmental Changes to ADHD Presentation in Adolescence

Across focus groups, caregivers and school staff revealed that ADHD affected high schoolers differently than it did during elementary or middle school, noting the added responsibilities at home and more challenging coursework typical of this developmental period as possible contributing factors. Caregivers also highlighted mood difficulties that manifest during high school for youth with ADHD.

“It’s not the same ADHD as when he was in middle school.” -Female Caregiver

“His grades were very good. He was an “A” student up to, I think the 7th grade. When he got to 8th, that’s when the problem [started].”-Female Caregiver

“But when he got to high school, he cannot sit, “I’m not doing the work”. But back in elementary school, he doesn’t do that.”- Female Caregiver

Participants noted that changes in responsibilities and symptom presentation often led to down-stream effects on adolescents’ ability to regulate emotions and subsequent comorbid psychopathology.

“He wasn’t moody until he got to high school.” -Female Caregiver

“Now he’s at this place I think now, mood-wise, where there’s an indifference. So, we’ve gone through the “what’s wrong with me” phase, we’ve gone through the “I’m angry about this” phase, and now we’re just kind of indifferent.”-Female Caregiver

“I wish that I wasn’t so sensitive. And that a lot of stuff didn’t get me mad. ‘Cus like it don’t really be serious but I get mad over small stuff.”-Female Student

“[They’re] very highly sensitive to their environment.” -Female SMHP

“… Mood, like frustration. I think since we’re in a high school they’ve had so many years of feeling a lack of success perhaps that sometimes there’s like a helplessness. You know I just can’t do it anyway and a feeling of lack of success. So also maybe like depressive type symptoms as well.” -Female SMHP

“After I’m done exploding or whatever I just sit back and think like ‘you gotta do better, that kinda stuff shouldn’t make you mad.’” -Female Student

Participants across groups described the struggle high school students with ADHD face with the aforementioned impairment while seeking normative teenage experiences and attaining developmental milestones in line with their peers (e.g., obtaining a part-time job, trying to fit in with peers, and experimenting with substances). However, having ADHD seemed to impact the ability of youth to engage in these behaviors without difficulties such as forgetting to show up for a job and getting fired and having trouble sustaining peer relationships.

“She got a job for a summer program. Got the job, she just didn’t show up. Why? ‘I didn’t have a ride.’ We’re on the bus line! You know, it’s just taking responsibility.” -Female Caregiver

“I think one of her biggest stressors is… her peers at school. She gets teased a lot. And that is one of the biggest things that we deal with because I get calls from her therapist all week long. ‘[Adolescent] isn’t here, she says she can’t go back to school, she cut class, and she’s falling apart.”- Female Caregiver

“I think sometimes…it starts out as playful behavior with peers or whatever and it’s not being able to tell when to stop or not being able to stop until it gets into something more contentious.” -Female SMHP

Future developmental stages were also a source of concern that emerged during the focus groups. Caregivers and school staff described fears about how adolescents’ ADHD-related impairment may affect the transition from adolescence to early adulthood. Specifically, they worried about adolescents’ abilities to attend post-secondary education, have a successful career, and have serious romantic relationships due to difficulties associated with ADHD.

“She’s 18, she’s officially a young woman, and she can’t—she wants to go to college—she can’t stay focused in high school. And college is a bigger, bigger thing… you can’t stay focused in a basic math class, you can’t stay focused in medical school.”-Female Caregiver

“Seniors sometimes don’t want to graduate because they’re scared to face reality and don’t want to leave the comfort of the school building. They’re not ready to go out there.” -Female Teacher

“If you’re not washing yourself, if you’re not completing your homework, how are you gonna go out here and get a job, how are you gonna get married one day?”- Female Caregiver

Contextual Factors Influencing Adolescents with ADHD

The second theme that emerged involved contextual factors influencing adolescents with ADHD and their interaction at various levels (school, community, family) to affect adolescent success and access to care. These included both positive factors (e.g., strengths of adolescents with ADHD, effective ADHD management strategies) and negative factors (e.g., environmental and systematic barriers to mental health care) that fell within 4 domains: individual, familial, school, and community/systems-level. These negative factors, especially prevalent in urban settings, pose a particular challenge to adolescents with ADHD, who already face significant disadvantages in initiating and maintaining care.

Individual Factors

The primary individual factor that emerged from interviews with stakeholders was the coping strategies employed by adolescents with ADHD. These ranged in effectiveness from adaptive strategies (defined as behaviors that engender better overall functioning or long-term benefits in adolescents) to maladaptive strategies (i.e., short-term, unsuccessful, or unhealthy responses to the environment).

Participants consistently reported impairments in emotion regulation among adolescents with ADHD. Indeed, emotion dysregulation (including emotional “meltdowns,” verbal arguments with caregivers/school staff, displays of disproportionate anger or aggression) provided an outlet for these youth with ADHD to maladaptively cope with negative experiences. Additional strategies described by caregivers, school staff, and students included internalizing centered around avoiding negative or potentially negative stimuli, trying to get out of tasks and obligations by making excuses, and learned helplessness.

“I think it is partly because of the many years of them feeling unsuccessful some of them have really wrecked out [i.e., become exhausted]. So, in the classroom this disruptive behavior, you know it’s hard to motivate them to get back on track or to work hard or to consistently come to class, some of them are like ‘I don’t care.’”- Female SMHP

“She will just, she will spend three days of a five-day week at home because she is ‘so sick.’ And she’s only sick during school hours.”- Female Caregiver

Per one student, this experience of avoidance and disengagement can come after experiencing emotional escalation stating,

“If I get mad or angry, I just like basically don’t do anything. I just give up. Cause I just don’t feel like doing anything no more. I just like do nothing. Just sit there.” -Male Student

Additionally, SMHPs described students with ADHD using substances to cope with school.

“I had several kids tell me that too. They smoke almost every day because they feel that they do better in school when they smoke marijuana. That they can focus better.” -Female SMHP

Caregivers, school staff, and adolescents also described the adaptive coping strategies of adoles-cents with ADHD, including help-seeking behavior:

“So if it’s not on an IEP it’s usually driven by the student. So if the student wants to see you, they’ll find you when they feel like they need to.” -Female SMHP

“I think at one point in time he probably used his ADHD as a crutch to do what he want but I think at this point he’s starting to own it so he know when he’s getting to a certain point, a level of frustration, it’s like okay I need to take a break. And he’ll say ‘can I get a pass?’ Whether he wants to go to the social worker or the psychologist. So I think with his situation him building relationships with different people and being comfortable with discussing how he feel kind of help him cope with it.”- Male Teacher

“It can be anyone in the building that they feel cares about them or that they’re connected to. It could be a teacher or it could be an administrator.” -Female SMHP

“I think people that they trust regardless of their position. You know, somebody that they’ve built a relationship with and they trust and who will follow through with things they say they will.” -Female SMHP

“So what I do - I mean I’m good at the class but I want to do better so what I do is sometimes I just go after class talk to my teacher and find some specific ways in I can do better in the class so I can be at the same level as certain people are.” -Male Student

Familial Factors

Throughout focus groups with teachers and SMHPs, the importance of caregiver involvement was a central feature for providing adequate support for adolescents with ADHD.

“When you do have a parent that finds a way to be involved in the students’ life though, in my experience those end up being the most successful students.” -Male Teacher

Teachers and SMHPs shared several explanations for low caregiver involvement, suggesting that some are uninvested while others are overwhelmed with their own responsibilities and stressors.

“I called and the [parental guardian] who answered said, ‘Don’t you ever call me again’ and he [the student] said, ‘Don’t do it. Please don’t call. She’ll yell at you.’ And she did.

She said, ‘I don’t want you calling. Tell those other teachers to stop calling me. He’s 17 years old. I’m sick of him, I’m sick of his brothers and sisters. I had them for years. He needs to do what he needs to do and don’t you call me again,’ and hung up. And he looks at me and he says, ‘I told you.’ And I said ‘I’m so sorry.’ So you’re dealing with kids that are coming out of homes that aren’t homes at all. The guardian is really not invested in their success. Not that there aren’t great guardians out there but we don’t know what the home is like.”-Female Teacher

“I think a lot [of parents] work and are busy and I think sometimes if a parent comes across upset I think it’s sometimes their own stress.”-Female SMHP

“My job is pretty intense and I’m a saleswomen… so, I- I had off today, that’s why I was able to come. And I won’t always be able to do this.”-Female Caregiver

“The biggest issue I had with therapists and psychiatrists was like time…theirs don’t work for me or things like that.”-Female Caregiver

Though contextual factors related to family and home life can place additional burden on adolescents with ADHD, several positive factors emerged as potentially protective against adverse outcomes. One positive factor was having caregivers and teachers who praise adolescents’ strengths and abilities rather than just focusing on their difficulties. For instance,

“On his progress reports and his report cards they all say the same thing – ‘Brilliant student, fun to teach, can do better in class, needs to focus more.” -Female Caregiver

“They are amazing on the basketball court where they’re focused. Their ability it’s like oh my gosh that’s him. I have pictures down there of that child making baskets, doing this exquisite physical, challenging, concentrated, successful performance on the playing field.” -Female Teacher

“You know when he’s really interested in something, you know he plays trumpet for the school band, and um, he’s really good! He’s really good when he focuses.” -Female Caregiver

Additionally, an open line of communication between the caregiver and school staff promoted improvements in both home and school domains. This uninterrupted, coordinated system of care appeared to yield the most successful outcomes for adolescents with ADHD.

“So, in the classroom, I email his teachers at least once every week. And it’s not because I have to, it’s just because I think that he does better when there’s an open line of communication that lets him know there’s an expectation.”- Female Caregiver

School-Based Factors

Teachers and SMHPs identified several barriers to care, including a lack of training and support for school staff in effective behavioral management. This was especially true for novice teachers:

“Oh my goodness…It’s a lot for experienced teachers let alone for a new teacher coming in. So I think there is a need [for training in behavioral management techniques]…and not just [for] teachers…Teachers and staff.”-Female Teacher

In addition to lack of support for school staff, participants reported instances of low teacher insight about ADHD resulting in greater stigmatization and harsher punishment for students with ADHD in comparison to their peers.

“My concern would be how the other teachers and administrative staff will view their behavior. How they view their actions and how they will be corrected. Some staff may not understand ADHD and give them a harsh or unjustified, in my opinion, punishment or consequence.”-Female SMHP

“Sometimes students, because they move, it’s almost like an actor who gets caught into playing the same role for every movie. Teachers automatically typecast them. They think that they know who the child is, and if it’s a child like mine, who speaks a lot, they don’t listen and read between the lines.”-Female Caregiver

[to her son’s teacher] “‘When I first started, I wanted to work with you. But I feel like you’ve bullied my son, and you’ve penalized him for something that’s outside of his control. And what you’ve said is ‘no, it is in his control, he can do something, he can make it better.’”- Female Caregiver

“You know, and it’s challenging because we try to help him but I just think he’s using it as a crutch, as a way not to do work.” -Male Teacher

As a result of teachers’ limited capacity to provide individual attention to struggling students (e.g., due to large class sizes, varying student ability), adolescents with ADHD often had negative perceptions of teachers and school staff.

“You know so if I put down this student every day, I put this student out now the student don’t even want to come back to class… we see the student in the hallway they’re like she don’t like me. Mr. so and so don’t like me and that’s not the case but it’s, they [teachers] don’t know how to deal with the disorder.”-Female SMHP

Conversely, teachers reported several strategies that they found helpful for students with ADHD, which often involved modifying the classroom environment.

“‘If you really can’t handle this in this moment, work on this’ and then in 10 minutes come back. It’s a long period to sit there. You let them be unsuccessful for 70 minutes but can you give them something that you know they can…and they all like to draw or they like to do anything graphic design. There’s something settling about the motion of a pen or pencil across paper. They’re still doing a quote unquote an assignment but it’s not the one that will send them out the door or to put their head down.” -Female Teacher

“I’m telling you the fact that they’re in the classroom for half the day and then, and you know for our ADHD kids if there was a chance for them to go down and work off their energy running around the gym and doing a couple laps midway through the day I bet we could hold them in the afternoon.” -Female Teacher

In addition to classroom-based barriers, systematic concerns at the school level added to difficulties experienced by students with ADHD (e.g., classroom sizes and class structure).

“If you’ve got ADHD you have to sit there for 70 minutes? On these hard chairs and keep working? Come on now.”-Female Teacher

“We have some classes with 40 kids in it…so fortunately someone like [teacher name] with years of experience is able to pinpoint a child with a disability like that pretty easily.”-Male Teacher

Despite the many school-based factors that contributed to lack of success and frustration seen in students with ADHD, there were many positive aspects of school-based resources as well.

“Most students who have an IEP [Individualized Education Program] has someone on their case like a social worker or some staff that they build a relationship with and they feel comfortable with.”- Female SMHP

“There’s also ‘coach class’…if they want to spend time with the teacher and go over the work that they need help with they can do that too.”-Female SMHP

Community/Systems-Level Factors

In addition to ADHD, students with low socio-economic status may face housing and food insecurity and lack of essential resources. This often resulted in youth assuming some financial or caregiving responsibility for their family, adding obligations on top of an overwhelming academic workload.

“Sometimes it’s just basics. It could be homelessness or not having enough clothes or food or supplies or being concerned that they have enough to pay for rent or those sort of things.” -Female SMHP

“You’ve got the kids that are working immediately when school’s over to put food on the table...Or the kid who’s a good athlete…a student whose parent…[thinks] they’re showing disloyalty because he’s going to wrestle instead of working to bring in money. -Female Teacher

“So when we look at the… juniors and seniors, a lot of them are raising themselves and their younger siblings.” -Male Teacher

Another systematic barrier reported was lack of both access to quality mental health services outside school and health insurance coverage. Students with ADHD had several resources within schools including mental health providers, social workers, and learning accommodations in the form of IEPs or 504 plans. Caregivers saw value in these resources but worried about how to maintain improvements without the support of school-based care (e.g., during the summer, after school hours).

“But when you have like, with her therapy, like the school therapy, that’s why I got the extra therapy, so when school ends she still has therapy. So, and she doesn’t have to pick up where she left off and try to start back and get re-acclimated.”- Female Caregiver

However, caregivers often found difficulty securing health insurance coverage for their adolescent or even finding adequate health care when they do have insurance, making bridge services over the summer or more intensive outpatient services unobtainable.

“She’s [my daughter] got three children. And neither one of them have health insurance yet. And I’m still trying to get her to go and get health insurance so that we can get him [my grandson] started back on something.”-Female Caregiver

“[The counselor] would come, maybe spend 10 minutes, but nothing was accomplished. They’ll sit around and look. And [adolescent], he wouldn’t do anything. He would just sit there and look, he wouldn’t participate in talking, so nothing was accomplished.”-Female Caregiver

Discussion

This qualitative study expanded existing literature by capturing the perspectives of Black adolescents with ADHD, their caregivers, teachers, and SMHPs in under-resourced urban high schools. Two overarching themes emerged: (1) developmental changes affecting the presentation of ADHD, and (2) the influence of contextual (i.e., school-/familial-/community-level) factors on adolescent success and access to care. To best connect the overarching themes and perspectives provided by focus group interviews, a conceptual model was adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979): “Ecological Model of Adolescents with ADHD in Urban High Schools.”

Using the framework of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979), we identified a range of characteristics that informed the lived experiences of low-income Black adolescents with ADHD in urban settings and the environmental influences surrounding their development. Nguyen and colleagues (2019) used quantitative methods to develop an ecological representation of ADHD in low-income (primarily White) youth that identified the presence of family- and community-level factors, many of which paralleled in-depth descriptions by our participants in this qualitative study. By utilizing an adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s model, we were able to identify similar contextual and systemic factors to characterize our sample of Black adolescents with ADHD. Qualitative data from this study are best represented by the following layers: Individual, Microsystem, Mesosystem, Exosystem, Macrosystem.

Individual: A Black Adolescent with ADHD in an Urban, Low-Income School District

Black adolescents with ADHD in low-income, urban areas are influenced by several individual level characteristics, including their own ADHD symptomatology, ability to cope, comorbid psychopathology, and individual strengths. These findings were consistent with prior literature implicating the influence of ADHD symptoms (Krueger & Kendall, 2001), coping skills (Harty et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2016; Molina et al., 2005), depressive/emotional symptoms (Hechtman et al., 2016; Howard et al., 2019), and individual strengths (Fugate et al., 2013; Harty et al., 2017) on the lived experiences and long-term outcomes of youth with ADHD. Both positive and negative individual-level factors and experiences in turn shape how adolescents with ADHD interact with their environments. Individual-level negative factors identified in our study included low frustration tolerance and ineffective coping strategies. These results aligned with previous work linking these negative characteristics with adverse consequences (e.g., depression, substance use) in adolescents with ADHD (Harty et al., 2017; Seymour et al., 2014).

Conversely, and consistent with prior literature (Harty et al., 2017), results of our thematic analysis linked effective emotion regulation and adaptive coping strategies to positive outcomes (e.g., reduced vulnerability to alcohol misuse, improved academic performance, elevated emotional well-being) among youth with ADHD. Our results extended these findings to low-income Black adolescents in urban schools, indicating need within this unique population for integrated treatment approaches involving components of socio-emotional learning, organization/time management, and emotion regulation and coping strategies (Haft et al., 2019; Meinzer et al., 2018).

Microsystem: The Adolescent’s Home, Peer Network, and Classroom

The microsystem of Black adolescents with ADHD in low-resource, urban areas consists of their interactions within the family, peer group, and classroom. In discussions surrounding the home life of adolescents with ADHD, caregivers and school staff described a number of negative influences (e.g., caregivers being overworked/stressed, lack of health insurance, family conflict). These observations have been identified in prior literature as contributing to increased risk for negative outcomes in youth with ADHD (Cuffe et al., 2009; Eadeh et al., 2017; Walther et al., 2012).

A review of youth with ADHD and relationships with their peers conducted by Gardner and Gerdes (2013) revealed that adolescents with ADHD had fewer friends and lower quality friendships (Gardner & Gerdes, 2013); this aligns with our finding that low-income Black adolescents with ADHD experience difficulties engaging in positive peer relationships, which could be due to poor emotion regulation and social skills. At the classroom level, research has found that adolescents with ADHD often receive harsher punishments and greater stigmatization by teachers (Kranke & Floersch, 2009). This aligns with results from the current study in which participants identified numerous negative school-based factors (e.g., low teacher insight, inflexible teaching strategies, peer rejection, stigma, large class sizes), which have been linked to adverse outcomes for youth with ADHD (Bussing et al., 2002; Kos et al., 2006; Kranke & Floersch, 2009; Mrug et al., 2012).

Mesosystem: Interactions between the Home, School, and Community

The mesosystem encompasses the connections between caregivers, teachers, and SMHPs. Results from our thematic analysis support the view that high caregiver engagement at home contributes to increased success for adolescents with ADHD in school settings. This finding aligns with existing research showing that adolescents with ADHD who have strong family cohesion experience more positive adjustment (Dvorsky & Langberg, 2016). This strong family cohesion can include family involvement in adolescents’ mental health care and academics (e.g., involving caregivers into treatment) which has been shown to be important in achieving positive psychotherapeutic outcomes (Sibley et al., 2016). Additionally, observations by caregivers and school staff of the benefits of coordinated care across home and school settings align with prior research demonstrating the advantages of multi-tier systems of support (MTSS) for youth with ADHD (Dong et al., 2020).

Exosystem: The Adolescent’s School System and Socio-economic Factors

Characteristics of the exosystem (i.e., the indirect environment) also exerted considerable influence on the experiences of Black adolescents with ADHD in low-resource, urban high schools. Based on our qualitative analysis, two types of indirect environments emerged: school and neighborhood contexts. Regarding the former, participants reported that schools and classrooms were regularly overpopulated, presenting additional challenges to teachers (especially those with limited teaching experience). This observation aligns with a survey by Bussing and colleagues in which teachers reported that large class sizes and lack of training were barriers to implementing effective instruction to students with ADHD, including learning accommodations (e.g., IEPs, 504 plans; Bussing et al., 2002).

Additionally, a study by Lawson and colleagues (2017) found a link between socioeconomic status and ADHD severity among a sample of racially and ethnically diverse children and adolescents. In our study, teachers and SMHPs described possible explanations for this relation, reporting that families’ financial struggles placed additional burden (e.g., caregiving responsibilities) on Black adolescents with ADHD managing an already overwhelming workload. Further examination is warranted to improve understanding of contextual stressors faced by this population.

Macrosystem: Cultural Perspectives, Social Values, and Familial Expectations

The macrosystem unites overarching social and cultural values that shape the experiences of low-income Black adolescents with ADHD in urban high schools. Previous research shows that many Black families express cultural mistrust and concerns about ingroup mental health stigma. This preoccupation with how they or their children will be perceived often elicits a barrier to help-seeking behaviors (Murry et al., 2011). Furthermore, Black caregivers may not be well-informed about the symptoms/impairment or treatment options for ADHD (Bailey et al., 2010). Our data extended these findings to teachers as well. Parents and teachers alike are sometimes ill-informed about the symptoms/impairments of ADHD and could benefit from additional psychoeducation. Additionally, across focus group interviews, there was considerable variability in familial expectations from caregivers and school staff regarding the desired roles and responsibilities of low-income Black adolescents with ADHD. These findings indicate the importance of cultural attitudes surrounding adolescence in shaping help-seeking behaviors, responsibilities, and expectations faced by youth with ADHD. Indeed, adolescents with ADHD from different ethnic groups may struggle with distinct difficulties depending on the cultural and contextual influences. The variability in perceptions about mental health care created an additional barrier to help-seeking behaviors and care coordination in adolescents with ADHD in urban, low-resource high schools.

Clinical Implications

There are a number of important clinical implications of this research, namely regarding considerations for how to best implement treatment in urban school settings and to support Black youth, families, and school staff with limited resources. Substantial burdens to caring for the needs of low-income Black youth with ADHD in urban high school settings were notably described across multiple ecological levels. A key finding emphasized by caregivers and school staff was the coordination of care between systems, for instance schools involving caregivers or different types of school staff communicating about a student. Our work suggests that in order for school-based interventions to be successful, cross-systems communication may be just as vital as the therapeutic components.

Relatedly, health sciences fields have paid increasing attention to social determinants of health, a concept which proposes that social factors play a critical role in health and mental health outcomes of individuals (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2005). The results of this qualitative analysis highlighted that the experience of having ADHD in urban high schools and navigating care successfully hinges tremendously on determinants such as food insecurity, abuse and neglect, trauma, neighborhood factors, race, and socioeconomic status. Critically, Merolla and Jackson (2019) argue that these contextual factors constitute the mechanisms through which structural racism perpetuates racial disparities in academic achievement (Merolla & Jackson, 2019) and treatment engagement (McKay et al., 2001). Therefore, it becomes the responsibility of mental health providers to actively work against racialized social structures by engaging in anti-racist education (e.g., “critical race theory”) and acknowledging the role of race, privilege, and oppression in mental health treatment (Alang et al., 2019). However, studies often de-emphasize information about these determinants when addressing ADHD in adolescents. Researchers attempting to optimize intervention engagement in lower resourced urban settings may need to pay particular attention to social determinants of health to lead to more advantageous outcomes for urban Black youth with ADHD. It may be necessary to adapt services to be more culturally sensitive to the needs of Black youth and their families (dosReis et al., 2007).

The manner in which ADHD-related difficulties are discussed is also important. In their seminal article, Garcia-Coll and colleagues (1996) note that research centered on racial minorities often characterize these youth as culturally “deprived” or “deficient” in comparison to their White peers. Their model highlights the importance of reporting adaptive skills and strengths within communities even when they face systemic barriers to optimal development opportunities due to factors such as racism, segregation, and other contextual factors that disproportionately impede access to resources for some groups (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). Our research highlighted a number of instances where families and school staff identified adaptive strategies for working with and raising urban adolescents with ADHD. Our subsequent theoretical model was deliberate in its ecological approach and addressing strengths and developmental competencies, rather than a focus merely on difficulties.

Limitations and Future Directions

The results from the current study and the subsequent adapted model need to be interpreted in light of their limitations. Notably, qualitative research as a methodology is highly informative for under-standing processes (e.g., contextual circumstances, lived experiences) by which phenomena take place and aiding researchers in posing thoughtful and meaningful hypotheses. However, this research does not tell us about the causality or intensity of these qualitative observations, nor does it quantify the salience of these themes. There may have also been some selection bias in this study. For instance, participating caregivers may be more engaged in their children’s schooling or mental health care given that they elected to participate in this research. Additionally, perceptions that disengagement was widespread among families, adolescents, and school staff in this population may not necessarily be reflective of all youth with ADHD, their caregivers, educators, and SMHPs, and we caution against broad over-generalizations of such perspectives.

Though the sample size for this study was appropriate for qualitative research, there were only six high school students with a previously established diagnosis of ADHD included as part of the focus groups, with the majority of participants being adult caregivers, teachers, and SMHPs. In some ways, this study provided a very rich picture of what the experience of supporting youth with ADHD in urban high school settings entails but was relatively less informative about the experience of being a high school student with ADHD. It also may be that these results may not generalize to an adolescent with ADHD who has not yet been identified or received a diagnosis of ADHD. Additionally, it should be noted that theoretical saturation did not guide the sampling strategy for this study. Because of this, there may be additional themes and perspectives not adequately captured in the data presented above. This may be particularly true for adolescent groups (e.g., regarding their coping strategies) and in relation to other systemic factors not explored (e.g., neighborhood characteristics, school district policy). Relatedly, because these focus groups were not designed primarily as a grounded theory qualitative study, certain hallmarks of this methodology, such keeping detailed process notes about reviewers’ experiences conducting the research and in-depth examination in researcher characteristics (e.g., demographics, training orientation, values) were not included or centered as they might otherwise be in a different study design. Further investigation is warranted to determine whether the implications of this research extend beyond family- and school-level themes explored here. Of note, the primary goal of these focus groups was to understand the feasibility of a school-based depression prevention intervention with a secondary aim of understanding the experience of high school students with ADHD. Future research on this topic should address this further and focus on including voices of youth living with ADHD. Additionally, future research is needed to test the proposed themes and model in this study quantitatively to facilitate an iterative approach to mixed methods and implementation research.

Conclusion

Two themes emerged portraying a multifaceted, interwoven picture of the individual and contextual strengths/challenges experienced by low-income Black adolescents with ADHD attending high schools in urban areas throughout their development, across multiple domains of functioning (home, school, with peers), and in the face of individual, familial, and structural barriers/facilitators to treatment. Our findings have implications for providing coordinated, cross-systems, culturally-competent care for Black adolescents with ADHD in under-resourced, urban settings.

Figure 1.

Ecological Model for Adolescents with ADHD In Urban High Schools, Adapted from Bronfenbrenner (1979).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from NIMH (R34 MH117086; MPI: Meinzer & Chronis-Tuscano).

References

- Alang SM (2019). Mental health care among blacks in America: Confronting racism and constructing solutions. Health services research, 54(2), 346–355. 10.1111/1475-6773.13115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RK, Ali S, Jabeen S, Akpudo H, Avenido JU, Bailey T, Lyons J, & Whitehead AA (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in African American youth. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12(5), 396–402. 10.1007/s11920-010-0144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnken MP, Abraham WT, Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Simons RL, & Gibbons FX (2014). Linking early ADHD to adolescent and early adult outcomes among African Americans. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42(2), 95–103. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brocki KC, & Bohlin G (2006). Developmental change in the relation between executive functions and symptoms of ADHD and co-occurring behaviour problems. Infant and Child Development: An International Journal of Research and Practice, 15(1), 19–40. 10.1002/icd.413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown NM, Brown SN, Briggs RD, Germán M, Belamarich PF, & Oyeku SO (2017). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Academic pediatrics, 17(4), 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Gary FA, Leon CE, Garvan CW, & Reid R (2002). General classroom teachers’ information and perceptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behavioral Disorders, 27(4), 327–339. 10.1177/019874290202700402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Assari S, & Breland-Noble AM (2016). The epidemiology of mental disorders in African American children and adolescents. In Handbook of mental health in African American youth (pp. 3–20). Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-25501-9_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cave L, Cooper MN, Zubrick SR, & Shepherd CC (2020). Racial discrimination and child and adolescent health in longitudinal studies: a systematic review. Social science & medicine, 250, 112864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Molina BS, Pelham WE, Applegate B, Dahlke A, Overmyer M, & Lahey BB (2010). Very early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(10), 1044–1051. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condron DJ, Tope D, Steidl CR, & Freeman KJ (2013). Racial segregation and the Black/White achievement gap, 1992 to 2009. The Sociological Quarterly, 54(1), 130–157. 10.1111/tsq.12010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E, Radcliff E, Bennett KJ, Brown MJ, & Hung P (2021). Examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Academic Pediatrics, Advanced Online Publication. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe SP, Moore CG, & McKeown R (2009). ADHD and health services utilization in the national health interview survey. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12(4), 330–340. 10.1177/1087054708323248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, & Blumberg SJ (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among US children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 199–212. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Garcia B, Pham AV, & Cumming M (2020). Culturally Responsive Approaches for Addressing ADHD Within Multi-tiered Systems of Support. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22, 1–10. 10.1007/s11920-020-01154-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Myers M, & Riley AW (2007). Coming to terms with ADHD: How urban African-American families come to seek care for their children. Psychiatric services, 58(5), 636–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Chronis-Tuscano A, Danielson ML, & Visser SN (2019). Predictors of receipt of school services in a national sample of youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(11), 1303–1319. 10.1177/1087054718816169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky MR, & Langberg JM (2016). A review of factors that promote resilience in youth with adhd and adhd symptoms. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(4), 368–391. 10.1007/s10567-016-0216-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eadeh HM, Bourchtein E, Langberg JM, Eddy LD, Oddo L, Molitor SJ, & Evans SW (2017). Longitudinal evaluation of the role of academic and social impairment and parent-adolescent conflict in the development of depression in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2374–2385. 10.1007/s10826-017-0768-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugate CM, Zentall SS, & Gentry M (2013). Creativity and working memory in gifted students with and without characteristics of attention deficit hyperactive disorder: Lifting the mask. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(4), 234–246. 10.1177/0016986213500069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Garcia HV (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DM, & Gerdes AC (2013). A Review of Peer Relationships and Friendships in Youth With ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(10), 844–855. 10.1177/1087054713501552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft SL, Chen T, LeBlanc C, Tencza F, & Hoeft F (2019). Impact of mentoring on socio-emotional and mental health outcomes of youth with learning disabilities and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child and adolescent mental health, 24(4), 318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty SC, Gnagy EM, Pelham WE Jr, & Molina BS (2017). Anger-irritability as a mediator of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder risk for adolescent alcohol use and the contribution of coping skills. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 58(5), 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Stehli A, Owens EB, Mitchell JT, … & Stern K (2016). Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(11), 945–952. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Kennedy TM, Macdonald EP, Mitchell JT, Sibley MH, Roy A, … & Molina BS (2019). Depression and ADHD-related risk for substance use in adolescence and early adulthood: concurrent and prospective associations in the MTA. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 47(12), 1903–1916. 10.1007/s10802-019-00573-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keigher A (2010). Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2008-09 Teacher Follow-Up Survey. First Look. NCES 2010-353. National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Neuendorf C, Bianco H, & Evans GW (2016). Exposure to childhood poverty and mental health symptomatology in adolescence: A role of coping strategies. Stress and Health, 32(5), 494–502. 10.1002/smi.2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos JM, Richdale AL, & Hay DA (2006). Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and their teachers: A review of the literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53(2), 147–160. 10.1080/10349120600716125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kranke D, & Floersch J (2009). Mental health stigma among adolescents: Implications for school social workers. School Social Work Journal, 34(1), 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger M, & Kendall J (2001). Descriptions of self: An exploratory study of adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 14(2), 61–72. 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2001.tb00294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, & Casey MA (2000). Focus groups. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson GM, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, Nahmias A, McConaughy SH, & Eiraldi R (2017). Do Parent and Teacher Report of ADHD Symptoms in Children Differ by SES and Racial Status?. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39(3), 426–440. 10.1007/s10862-017-9591-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litner B (2003). Teens with ADHD: The challenge of high school. Child and Youth Care Forum, 32(3), 137–158. 10.1023/A:1023350308485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, & Wilkinson R (Eds.). (2005). Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Pennington J, Lynn CJ, & McCadam K (2001). Understanding urban child mental health service use: Two studies of child, family, and environmental correlates. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 28(4), 475–483. 10.1007/BF02287777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer MC, Hartley CM, Hoogesteyn K, & Pettit JW (2018). Development and open trial of a depression preventive intervention for adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cognitive and behavioral practice, 25(2), 225–239. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merolla DM, & Jackson O (2019). Structural racism as the fundamental cause of the academic achievement gap. Sociology Compass, 13(6), e12696. 10.1111/soc4.12696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldana J (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Moldavsky M, & Sayal K (2013). Knowledge and attitudes about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and its treatment: the views of children, adolescents, parents, teachers and healthcare professionals. Current psychiatry reports, 15(8), 377. 10.1007/s11920-013-0377-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Marshal MP, Pelham WE, & Wirth RJ (2005). Coping skills and parent support mediate the association between childhood attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder and adolescent cigarette use. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30(4), 345–357. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG & Pelham WE (2003). Childhood predictors of adolescent substance use in a longitudinal study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(3), 497–507. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PL, Hillemeier MM, Farkas G, & Maczuga S (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in ADHD diagnosis by kindergarten entry. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(8), 905–913. 10.1111/jcpp.12204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Molina BS, Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L, & Arnold LE (2012). Peer rejection and friendships in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Contributions to long-term outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(6), 1013–1026. 10.1007/s10802-012-9610-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Heflinger CA, Suiter SV, & Brody GH (2011). Examining perceptions about mental health care and help-seeking among rural African American families of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1118–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MN, Watanabe-Galloway S, Hill JL, Siahpush M, Tibbits MK, & Wichman C (2019). Ecological model of school engagement and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(6), 795–805. 10.1007/s00787-018-1248-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyan O, Garriett V, Mychailyszyn MP, Anixt J, Rowe PC, & Cheng TL (2007). Community perspectives of childhood behavioral problems and ADHD among African American parents. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7(3), 226–231. 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osher D, Poirier J, Jarjoura R, Brown R, & Kendziora K (2014). Avoid simple solutions and quick fixes: Lessons learned from a comprehensive districtwide approach to improving student behavior and school safety. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 5(2), 16. [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, & DuPaul GJ (2015). Treatment of ADHD in school settings. In Barkley RA (Ed.), Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed., pp. 596–629). New York, NY: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020) NVivo (released in March 2020), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Rogers M, Bélanger-Lejars V, Toste JR, & Heath NL (2015). Mismatched: ADHD symptomatology and the teacher–student relationship. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 20(4), 333–348. 10.1080/13632752.2014.972039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser TR, Kalvin CB, & Bierman KL (2016). Developmental trajectories of clinically significant attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms from grade 3 through 12 in a high-risk sample: Predictors and outcomes. Journal of abnormal psychology, 125(2), 207–219. 10.1037/abn0000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour KE, Chronis-Tuscano A, Iwamoto DK, Kurdziel G, & MacPherson L (2014). Emotion regulation mediates the association between ADHD and depressive symptoms in a community sample of youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(4), 611–621. 10.1007/s10802-013-9799-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Graziano PA, Kuriyan AB, Coxe S, Pelham WE, Rodriguez L, … & Ward A (2016). Parent–teen behavior therapy+ motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 699–712. 10.1037/ccp0000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Hechtman LT, Owens EB, Stehli A, … & Jensen PS (2017). Defining ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood: optimizing sensitivity and specificity. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 58(6), 655–662. 10.1111/jcpp.12620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobodin O, & Masalha R (2020). Challenges in ADHD care for ethnic minority children: a review of the current literature. Transcultural psychiatry, 57(3), 468–483. 10.1177/1363461520902885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AL, Klingbeil DA, & Van Norman ER (2013). Beyond behavior: Multilevel analysis of the influence of sociodemographics and school characteristics on students’ risk of suspension. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 99–114. 10.1080/02796015.2013.12087493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, & Langley K (2013). Practitioner review: what have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(1), 3–16. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C & Dixon A (2009). Low-income African American male youth with adhd symptoms in the united states: recommendations for clinical mental health counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31(4), 309–322. 10.17744/mehc.31.4.j451mx7135887238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walther CA, Cheong J, Molina BS, Pelham WE Jr, Wymbs BT, Belendiuk KA, & Pedersen SL (2012). Substance use and delinquency among adolescents with childhood ADHD: The protective role of parenting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 585–598. 10.1037/a0026818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker K, Nicodimos S, Pullmann MD, Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Wasse JK, & Lyon AR (2018). Predictors of disparities in access and retention in school-based mental health services. School mental health, 10(2), 111–121. 10.1007/s12310-017-9233-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]