Abstract

Continued professional development is important for promoting quality early childhood care and education (ECE) programs. One approach to fulfill this need for professional development is through the creation of a community of practice, which brings together professionals with similar interests. In this investigation, we report the evaluation results for one CoP, called the Early Childhood Consortium, that included ECE center directors and teachers. We examine if members of the consortium formed a Sense of Community (SOC). Factors that may relate to SOC were also considered for both teachers and directors, including trust in information shared, workplace characteristics (e.g., perceived support, hours worked), and Consortium members’ professional agency. Trust in the information exchanged within the Consortium and workplace characteristics within member centers were related to SOC, but differences, supported by t-tests, between director and teacher SOC did occur. SOC also significantly correlated with survey and activity measures of professional agency within the Consortium in that those endorsing stronger SOC said they would be more likely to share and adopt knowledge with one another. SOC also positively correlated with participation of center staff within the Consortium, but not with individual levels of involvement, suggesting that directors and teachers influence one another’s participation in professional development activities. CoP leaders should be intentional in supporting directors’ abilities to promote SOC within their own centers and to connect CoP professional activities with classroom practices.

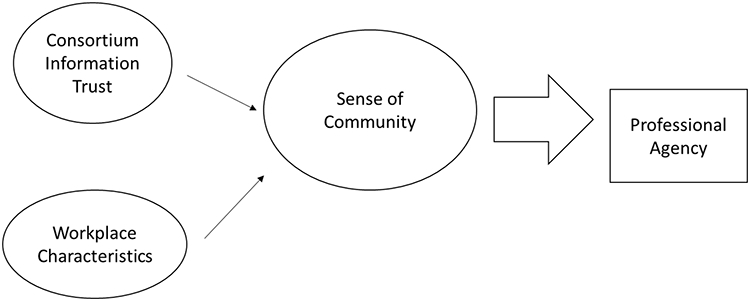

Professional development is important for early childhood educators who face multiple challenges, which often converge to compromise program quality (Whitebook, King, Philipp, & Sakai, 2016). These challenges are often greater in poorer urban areas, and include inadequate preparation, high stress, minimal qualifications for teachers and directors, and high attrition (Fuligni, Howes, Lara-Cinisomo, & Karoly, 2009; Gable, Rothrauff, Thornburg, & Mauzy, 2007; Madill, Blasberg, Halle, Zaslow & Epstein, 2016). Professional development is often provided for early childhood educators with the aim of addressing these challenges (Howes, Pianta, Bryant, Hamre, Downer, & Soliday-Hong, 2008), but the effectiveness of professional development programs reflects the changes in learning and practice that result from them (Sankey & Machin, 2013). Consequently, it is important to identify characteristics of professional development programs that support desired outcomes. In the current investigation, we report results of an evaluation (i.e., a systematic examination of whether a program leads to desired outcomes) to examine the impact of a community of practice (CoP) called the Early Childhood Consortium (hereafter referred to as the “Consortium”) composed of early childhood care and education (ECE) center directors and their teachers in an urban area. We explored sense of community (SOC) among members of the Consortium and evaluated correlates of SOC (see Figure 1) over the course of two years.

Figure 1.

Possible relationships among the factors guiding the program evaluation questions.

The aim of the Consortium was to strengthen program quality through changes in practice brought about by director and teacher engagement in and learning from the professional development activities it provides. We aimed to create SOC within the Consortium to help support these outcomes; thus, evaluation of the program focused on SOC. The two factors we explored as possible contributors to SOC were (1) Consortium information trust, a central feature of the CoP experience in general (Evans & Wensley, 2009), and (2) characteristics of the workplaces from which CoP participants were drawn (i.e., support and hours worked; McGinty, Justice & Rimm-Kaufman, 2008; Royal & Rossi, 1996; see Figure 1). We proposed that SOC is in turn related to professional agency, which is integral to lifelong learning and change in workplace practice and can serve as an input to change in practice (Toom et. al, 2017). In line with conceptualization of professional agency by Etelapelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, and Paloniemi (2013), we operationalize professional agency as knowledge exchange and Consortium engagement. In the sections to follow, we review the literature relevant to CoPs, SOC, and discuss building SOC within the Consortium.

Community of Practice and Sense of Community

An approach to professional development involves participation in a CoP. Communities of Practice bring together professionals with common interests to interact, share resources, and learn new knowledge from one another (Wenger, 1999). CoPs may best promote changes in practice and professional agency when a SOC emerges among its members (Cobb & McClain, 2001; Nistor, Daxecker, Stanciu, & Diekamp, 2015). SOC is a psychological construct reflecting the “fundamental human phenomenon of collective experience” (Peterson, Speer, & McMillan, 2008), and has been examined in many contexts, including schools and professional development settings involving educators (Admiraal & Lockhorst, 2012). Changes in instructional practice influenced by SOC, and potentially the agency resulting from it, are in turn related to improvements in program quality and child outcomes (Guo, Kadervaek, Prasta, Justice, & McGinty, 2011). Despite the potential significance of SOC for professional development, a review of the literature indicates that only a small number of studies involve early childhood educators and fewer still include center directors or urban settings.

The Early Childhood Consortium

The authors, who are university faculty and staff, organized the Consortium in 2011 to provide networking, collaboration, mentoring, and professional development for directors of ECE centers within a particular neighborhood in a large Midwestern city. The Consortium was part of a larger city-wide initiative to develop the community by strengthening early childhood education. The primary focus was on center directors given their needs for connection and collaboration to be effective leaders (Stremmel, Benson, & Powell, 1993) and the role their leadership plays in creating change within their programs. Despite this role, professional development for directors has been limited overall (Ryan & Whitebook, 2012), and even less often provided within the context of a CoP like the Consortium (Ratner, Bocknek, Miller, Elliott, &Weathington, 2018). Thus, most Consortium programs were for center directors, but there were also less frequent offerings for teachers.

We, the Consortium leadership team, recruited directors through face-to-face meetings and phone calls. As the Consortium leadership team, we also facilitated Consortium programming. Director incentives to participate included resources for the centers such as children’s books, training manuals, support from community service organizations and agencies, and professional development. Centers received these resources free of charge and associated costs were funded by foundation and federal grants applied for, awarded to, and administered by one or more of the authors.

During the academic year, the Consortium hosted monthly meetings and an annual training for center directors and community partners. The Consortium also held an annual conference for teachers, directors, and community partners. Additionally, centers wishing to participate received coaching and onsite training, which involved both the director and the teachers at the site. The purpose of these activities was to strengthen program quality by focusing on topics suggested by directors and to promote SOC. These topics included instruction (e.g., essential instructional practices in early literacy), classroom climate (e.g., social problem-solving with young children), resources and services for families (e.g., collaborative partnerships with parents, homelessness, autism, crisis care, health/mental health, trauma, basic needs), or staff management (e.g., how to develop teams). Across all Consortium contexts, directors and teachers were encouraged to incorporate what they had learned into their center practices.

Building Sense of Community

Consortium Information Trust.

Although format for content delivery was sometimes traditional, the process used to create content was intended to reflect “authentic” features of communities of practice, such as meeting the needs of the group members (MacPhail, Patton, Parker, & Tannehill, 2014), collaboration, shared learning (Brown, Horn, & King, 2018); and listening to feedback (Black, 2019). For instance, in the monthly meetings facilitated by the authors the member directors decided together on what the professional development content would be and helped design customized services often delivered onsite at the centers. Directors and teachers provided feedback on how activities could be improved to meet their needs, and then this feedback was incorporated into the next activity. Over time by working together the expectation was that relationships would deepen among Consortium members and with leaders, greater collaboration would occur across centers, and more information and resources would be available to directors and teachers, creating a sense of trust in one another and in the information shared (Evans & Wensley, 2009). These aspects of the Consortium experience reflected a collaborative culture rather than contrived collegiality (Hargreaves & Dawe, 1990). In collaborative cultures, relationships evolve and trust is organically created. Contrived collegiality often involves the administrative imposition of interactions and is characterized by patterns of control. Trust is important in the effectiveness of professional development initiatives (Conner, 2015), bringing about transformational change (Browning, 2014; Kutsyuruba & Walker, 2015), and building sense of community (McMillan, 1996). Thus, we anticipated that higher levels of trust in information from the Consortium would be related to higher SOC.

Member Center Workplace Characteristics.

Directors were the focus of the Consortium because of the central role that they play in leading their centers and improving program quality (Talan, Bloom, & Kelton, 2014). Nevertheless, changes in practice cannot occur without the participation and engagement of teachers (Conner, 2015). Consequently, teachers were also included in the Consortium and participated in key Consortium activities, such as the annual conference. Joint participation of directors and teachers, however critical to the goal of changing practices, may in itself create contexts that could heighten or hinder the development of SOC within the Consortium. For instance, directors and teachers who already work together may bring the dynamics of their working relationships to Consortium activities and later attempts to apply Consortium learning to practices within the centers. In particular, given the positive relation between social support and sense of community (McMillan & Chavis, 1986), a stronger SOC within the Consortium may emerge among those who already feel greater support and less stress within their own centers. The number of hours worked within the center may also be relevant. Directors and teachers who work together more may have deeper relationships with one another that then could extend to the Consortium, as in other contexts (Blatt & Camden, 2007), or conversely working more hours may contribute to higher levels of stress (Johnstone, 1993) that could hinder the emergence of SOC. Thus, we examined the relationship between workplace characteristics and SOC.

Sense of Community and Professional Agency

Individuals become members of CoPs because they think they can satisfy their needs within them (Owens & Johnson 2009). Others, and what they provide, are considered resources and members discover how they can benefit from what the community offers. Members develop a sense of belonging and feel that they are valued by other members (McMillan & Chavis, 1986). Perceived ties within a community may lead members to share knowledge and influence one another to adopt new ideas (Wenger, 1999). Knowledge sharing and knowledge adoption (Hislop, 2013), which involve active restructuring of new and old information, can be seen as aspects of professional agency and potential inputs into changes in practice (Runhaar & Sanders, 2016). In support of this idea, SOC has been found to play a role in acceptance of knowledge sharing in higher education settings (Nistor et al. 2015) and knowledge adoption among virtual communities (Chou, Wang, & Tang 2015). Both have been found to be related to improved and more creative work performance among individuals and in many types of teams and organizations (Ahmad & Karim, 2019).

SOC may also be related to engagement in professional development activities, which requires action, a key component of professional agency. McMillan (2011) argues that as a result of perceived connections to a community, members are willing to participate in the community and take on responsibilities within the group. Relationships deepen as members share activities and create a common history, reducing isolation and promoting interaction. Engagement with these purposeful and goal-oriented professional development activities is a first step toward ultimate learning and changes in practice (Eun, 2008). We examined whether SOC in the Consortium was related to professional agency.

Evaluation Questions

Three questions involving the factors illustrated in Figure 1 guided our program evaluation:

Did ECE directors and teacher members of the Early Childhood Consortium form SOC?

Was trust in Consortium information and center workplace characteristics related to SOC for directors, teachers, or both?

Was SOC related to Consortium professional agency?

Method

Evaluation data were collected from the Consortium ECE center directors and teachers during two years: Year 1 was academic year 2016-2017 and Year 2 was academic year 2017-2018.

Participants

Consortium center members.

The Consortium included community-based centers in two defined inner-city areas within a large Midwestern city. In Year 1, 14 member centers participated and in Year 2, 15. The number and type of center participant in each year appears in Table 1. Nine centers participated in both years. Two years of data allowed assessment of whether patterns shifted as members changed.

Table 1.

Early Childcare and Education (ECE) Center Type Participants in Year 1 and 2 Assessment

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| ECE Type | ||

| Agency-Sponsored | 4 | 7 |

| Chartered | 1 | 1 |

| Corporate | 4 | 2 |

| Privately-Owned | 3 | 3 |

| University-Based | 2 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 14 | 15 |

Survey participants.

Year 1.

Director (n = 15) and teacher (n = 46) data were compiled from the 14 ECE centers. For one of the centers, the director did not participate but a teacher did, leaving 13 centers represented by their directors in the sample. Two centers had two directors and for each center both directors participated, yielding 15 directors. Background data for Year 1 directors were not available. (See next section.) Year 1 participant information appears in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Director and Teacher Participants in Year 1 and Year 2 Assessment

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directors | Teachers | Directors | Teachers | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Women | 14 | 93.3 | 44 | 95.7 | 14 | 93.3 | 36 | 97.3 |

| Men | 1 | 6.7 | 2 | 4.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.7 |

| Years’ Experience in Early Childhood | ||||||||

| <1 | a | 9 | 19.6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 13.5 | |

| 1-3 | 5 | 10.9 | 1 | 6.7 | 4 | 10.8 | ||

| 3-5 | 4 | 8.7 | 2 | 13.3 | 7 | 18.9 | ||

| 5-15 | 13 | 28.3 | 5 | 33.3 | 10 | 27.0 | ||

| >15 | 15 | 32.6 | 7 | 46.7 | 11 | 29.7 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | ||||||||

| Yes | a | 14 | 30.4 | 12 | 80.0 | 15 | 40.5 | |

| No | 32 | 69.6 | 3 | 20.0 | 12 | 32.4 | ||

Demographic information was not collected for Directors in Year 1. See Method for more details.

Year 2.

Director (n = 15) and teacher (n = 37) data were compiled from the 15 ECE centers. Again, for one of the centers, the director did not participate but a teacher did, leaving 14 centers represented by their directors. In addition, one center had two directors and both directors participated, yielding 15 directors. Year 2 participant information for both directors and teachers appears in Table 2.

Evaluation Procedures

Evaluation information was collected at several points throughout the two years. Records were maintained and reviewed for who attended each Consortium event and in which center they worked. All surveys were submitted to the authors' University Institutional Review Board. Because the information collected was for the purpose of program evaluation and because the information was professional and not personal in nature, the project was determined to be a program evaluation and further review was not required.

Year 1.

Directors and teachers completed surveys that included SOC and perceived support at their centers. When the academic year began, all center directors received an email that explained the survey and noted the expected time to complete it (less than 10 minutes). Participation was voluntary and in no way connected to receipt of Consortium programing. Eight directors completed the survey. This online survey was kept intentionally brief to ease the response burden of the directors. As a result, director demographic data was not requested. Teachers and directors completed a paper survey at the annual Consortium conference, which in addition to the SOC and support measures also included demographic characteristics. The evaluation survey was introduced at the end of the conference. We explained verbally to the group as a whole that participation was voluntary. Then voluntary participation was restated on a cover sheet explaining the brief survey that was given to each individual. The survey was completed by 46 teachers and 4 directors. At the end of the academic year, an email survey on SOC and perceived support at their centers was sent again to center directors. Again, this survey was brief and participation was voluntary. Some directors completed surveys at multiple points, but only information from their last survey was included for analysis. This information was compiled for Year 1 in a de-identified file.

Year 2.

Directors and teachers attending the annual conference received an email survey assessing demographics, SOC, and perceived support at their centers. Eleven directors and 34 teachers completed the survey. These same domains were assessed through a second survey at the annual professional development training. This survey was completed by eight directors and four teachers. As in Year 1, it was explained verbally and in writing that completion of the surveys was voluntary and unconnected to taking part in Consortium programming. When both surveys were completed, responses for only the final one were included for analysis. This information was compiled for Year 2 in a de-identified file.

Measures

Sense of Community.

A modified version of The Brief Sense of Community Scale (BSCS; Peterson, Speer, & McMillan, 2008) was used to assess participants’ SOC within the Consortium. Wording of the original items was changed to fit the current project (e.g., “I can get what I need from the Consortium” instead of “I can get what I need from this neighborhood.”). The BSCS includes eight items rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree), and is summed into four subscales with two items each: needs fulfillment (NF), membership (MB), influence (IN), and emotional connection (EC). Subscale items are presented in Table 3. A total SOC score was computed with a possible range from 0 to 32.

Table 3.

Items and Subscales Measuring Sense of Community

| Subscales | Items |

|---|---|

| SOC NF | The Consortium helps me fulfill my needs. |

| I can get what I need in the Consortium. | |

| SOC MS | I belong in the Consortium. |

| I feel like a member of the Consortium | |

| SOC IN | I have a say about what goes on in the Consortium. |

| People in the Consortium are good at influencing each other. | |

| SOC EC | I feel connected to the Consortium. |

| I have a good bond with others in the Consortium. |

Note: SOC NF = Sense of Community Needs Fulfillment, SOC MS = Sense of Community Membership, SOC IN = Sense of Community Influence, SOC EC = Sense of Community Emotional Connection

Consortium information trust.

To determine levels of trust members had in Consortium information, directors and teachers were asked to rate agreement with the statement “I trust the information that I receive from the Consortium.” Agreement was rated on a 5-point scale that varied from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Workplace characteristics.

Perceived support.

We selected 10 items from the Child Care Worker Job Stress Inventory (Curbow, Spratt, Ungaretti, McDonnell & Breckler, 2000) to measure perceived support. Items assessed childcare providers’ feelings of importance, respect, appreciation, and positive impact, along with one-on-one time with children, availability of supplies, and presence of child behavior problems. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Rarely/Never; 5 = Most of the Time). Two negatively worded items were reverse scored and then the 10 items were summed to create a Support score (range, 5 to 50). Higher scores indicated more support and less stress.

Hours worked.

Directors and teachers reported how many hours per week they worked at their centers.

Professional agency.

Knowledge exchange.

Knowledge exchange was assessed by asking two questions concerning knowledge adoption and knowledge sharing. Directors and teachers in Years 1 and 2 rated their agreement with two statements, “I gladly learn from other Consortium members” (knowledge adoption) and “I gladly share my knowledge with other Consortium members” (knowledge sharing). Agreement was rated on a 5-point scale that varied from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Consortium Involvement.

Two measures of Consortium Involvement were created. The first reflected participation on an individual level and the second, center-wide participation. For directors, the individual involvement measure was the number of hours they participated in collective Consortium activities (i.e., monthly meetings, conference planning meeting, professional development workshop, and annual conference). The one collective Consortium activity teachers could participate in was the annual conference. In Year 2 we assessed whether teachers were “low” or “high” participators based on whether they had attended one or more than one conferences, respectively.

For center-wide involvement, each center was given a score that reflected the number of hours a particular Consortium event required. For each event if any center member attended, the center received a score. Thus, the number of people attending did not influence the score allowing control for size of center. For directors this measure varied for each person whereas for teachers this value was the same for all those in the same center. For each monthly Consortium meeting any member attended, the center received a 1.5 (five meetings were held in both years). Attendance at the conference planning committee meeting received a score of 1.5. Attendance at the conference received a score of 4.5. Attendance at the professional development seminar received a score of 3.5. These numbers were summed to generate an overall score that reflected how many hours each center participated in Consortium activities each year.

Results

(1). Did ECE directors and teacher members of the Early Childhood Consortium form SOC?

In Table 4 director and teacher mean ratings for the SOC Total and subscale items appear for Years 1 and 2. A score of 16 marked the neutral point for the total score (32), and four, the neutral point for each of the two-item subscales (8 total each). Scores significantly greater than neutral indicated that respondents agreed as a group that they experienced a sense of community.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations (SD) for Sense of Community (SOC) Ratings for Directors and Teachers

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director | Teacher | Significant Difference1 | Director | Teacher | Significant Difference1 | |||

| M(SD) | M(SD) | t (df) | p-value | M(SD) | M (SD) | t (df) | p-value | |

| SOC NF | 7.13 (.83) | 6.28 (1.33) | −2.33 (59) | .023 | 6.80 (1.21) | 6.11 (1.85) | −1.33 (50) | .189 |

| SOC MS | 7.33 (.82) | 5.89 (1.64) | 3.26 (58) | .0001 | 6.73 (1.44) | 5.49 (1.84) | −2.35 (50) | .023 |

| SOC IN | 7.07 (1.10) | 5.62 (1.42) | −3.59 (58) | .001 | 6.00 (1.93) | 5.28 (1.95) | −2.18 (50) | .034 |

| SOC EC | 6.87 (1.24) | 5.64 (1.65) | −2.60 (58) | .001 | 6.33 (1.11) | 5.27 (1.74) | −1.21 (49) | .233 |

| SOC Total | 28.40 (3.27) | 23.07 (5.92) | −3.32 (59) | .002 | 25.87 (5.19) | 22.00 (6.87) | −1.96 (50) | .056 |

Note: SOC NF = Sense of Community Needs Fulfillment, SOC MS = Sense of Community Membership, SOC IN = Sense of Community Influence, SOC EC = Sense of Community Emotional Connection

p-values are provided for t-tests between Director and Teacher Total and subscale mean SOC ratings

In Years 1 and 2, the SOC Total score was significantly higher than neutral for directors [t (14) = 14.69, t (14) = 7.36, ps < .001, respectively] and teachers [t (45) = 8.10, t (36) = 5.31, ps < .001, respectively). All subscale scores were significantly higher than neutral in each of the two years for directors and teachers as well (t-scores ranged from 4.02 to 8.98 in Year 1 and 6.67 to 15.81 in Year 2; all p-values <.001). In addition, director ratings were higher than those of teachers, except for two Year 2 subscales as shown in Table 4. Overall, directors did rate SOC higher than teachers.

(2). Did Consortium information trust and center workplace characteristics correlate with SOC for directors, teachers, or both?

Consortium information trust.

In Year 1, all of the directors agreed (20%) or strongly agreed (80%) that they trusted the information from the Consortium. Most teachers also agreed (37%) or strongly agreed (60.9%). In Year 2 93.3% of directors strongly agreed with the trust item and 27% of teachers agreed and 59.5% strongly agreed. The difference in trust between directors and teachers was not significant (.10 < p < .20) in Year 1, but was in Year 2, X2(1, n = 52) = 5.75, p < .05. In Table 5 correlations between Consortium information trust and SOC ratings appear for directors and teachers for Years 1 and 2. For directors and teachers, trust in the information the Consortium provided was positively and either significantly or marginally significantly related to the SOC total score and most of the subscales either in Year 1 or Year 2 or both.

Table 5.

Correlations between Sense of Community (SOC) Ratings, Trust, and Workplace Characteristics

| Trust | Workplace Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours Per Week | Perceived Support | ||||||

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||

| Directors | SOC NF | .50+ | .64** | --- | .48 | .27 | .44 |

| SOC MS | .21 | .72** | --- | .37 | .03 | .19 | |

| SOC IN | .50+ | .33 | --- | −.17 | .20 | .56* | |

| SOC EC | .36 | .57* | --- | .36 | −.01 | .43 | |

| SOC Total | .49+ | .63* | --- | .33 | .14 | .37 | |

| Teachers | SOC NF | .60** | .82** | −.20 | .35* | .34* | .19 |

| SOC MS | .31* | .72** | −.00 | .34* | .48** | .38* | |

| SOC IN | .42** | .61** | −.22 | .43* | .35* | .28+ | |

| SOC EC | .42** | .75** | −.10 | .42* | .45** | .22 | |

| SOC Total | .50** | .76** | −.14 | .41* | .41** | .30+ | |

Note:

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

SOC NF = Sense of Community Needs Fulfillment, SOC MS = Sense of Community Membership, SOC IN = Sense of Community Influence, SOC EC = Sense of Community Emotional Connection

Workplace Characteristics.

Correlations between SOC ratings and perceived support and hours worked also appear in Table 5. For Year 2 directors, support was significantly correlated with IN (influence); no other associations emerged. For teachers in Year 1 SOC Total and all subscale scores were positively related to support, but not hours worked. In Year 2, SOC was positively and significantly correlated with both perceived support and hours worked for most SOC subscales.

(3). Was SOC related to Consortium professional agency?

Knowledge exchange—Knowledge sharing and knowledge adoption.

In Year 1, all of the directors agreed or strongly agreed that they would learn from other members (knowledge adoption) in contrast to 82.7% of teachers. All of the directors and 91.1% of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that they would share their knowledge (knowledge sharing). In Year 2, the results were almost identical for knowledge adoption: All of the directors and 81.0% of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that they would learn from one another; however, the findings differed for knowledge sharing. All of the directors agreed or strongly agreed that they would share their knowledge, but only 78.3% of teachers so agreed.

In Table 6 correlations between SOC ratings and the responses to the knowledge exchange statements (knowledge adoption, knowledge sharing) are presented. For Year 1 directors, SOC Total, NF (needs fulfillment), and IN (influence) were significantly correlated with knowledge adoption (“gladly learn”) and knowledge sharing (“gladly share”). For teachers all SOC ratings were positively and significantly related to both knowledge exchange statements. In Year 2, the same pattern occurred for teachers, and for directors Membership was now also significantly and positively correlated with knowledge adoption, and marginally with knowledge sharing. For teachers SOC was positively and significantly correlated with both knowledge measures both years.

Table 6.

Correlations between Sense of Community (SOC) Ratings, Knowledge Exchange Statements (Adoption and Sharing), and Center-wide Engagement

| Year 1 | Year 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Adoption |

Knowledge Sharing |

Center-wide Engagement |

Knowledge Adoption |

Knowledge Sharing |

Center-wide Engagement |

||

| Directors | SOC NF | .66** | .66** | .16 | .56* | .50+ | .17 |

| SOC MS | .26 | .26 | .45+ | .53* | .47+ | .41++ 1 | |

| SOC IN | .61* | .61* | .09 | .63* | .70** | .11 | |

| SOC EC | .43 | .43 | .35 | .44 | .36 | .28 | |

| SOC Total | .60** | .60** | .31 | .57** | .53* | .28 | |

| Teachers | SOC NF | .45** | .35* | −.05 | .83** | .77** | .24 |

| SOC MS | .51** | .61** | −.03 | .75** | .76** | .39* | |

| SOC IN | .65** | .38** | −.24 | .72** | .64** | .22 | |

| SOC EC | .61** | .63** | −.13 | .71** | .76** | .20 | |

| SOC Total | .51** | .46** | −.09 | .80** | .76** | .28 | |

Note:

p < .10 one-tailed

p < .10 two-tailed

p < .05 two-tailed

p < .01 two-tailed

Note: SOC NF = Sense of Community Needs Fulfillment, SOC MS = Sense of Community Membership, SOC IN = Sense of Community Influence, SOC EC = Sense of Community Emotional Connection

When director and teacher scores are combined, the correlation between SOC and center engagement is significant, r = .328, p < .05

Consortium involvement.

For Consortium Involvement we first examined individual participation. No significant correlations emerged in Years 1 or 2 for directors or teachers between the individual participation scores and the SOC ratings or the knowledge exchange statements. For the center-wide engagement measure a different pattern occurred. In Table 6 the correlations between SOC and center-wide Consortium involvement appear. For directors in both Years 1 and 2, there was a marginally significant association between center-wide engagement and SOC MB (membership). For teachers, there was a statistically significant association between center-wide engagement and membership in Year 2. When Year 2 teacher and director scores were combined the correlation involving directors was also significant, r = .328, p < .05.

Discussion

Sense of Community

Director and teacher members of an urban ECE consortium clearly formed a sense of community with one another that extended beyond the boundaries of the centers in which they worked. Shared location may facilitate community building (Admiraal and Lockhorst, 2012), but proximity was unnecessary to do so here, similar to what occurs in virtual interactions (e.g., Baba, Gluesing, Ratner, & Wagner, 2004). Directors, in particular, appeared to benefit from the interconnections the Consortium created. This finding is significant because ECE center directors do not always collaborate and sometimes compete with one another (Ratner et al., 2018). Collaboration is associated with quality programming in ECE centers (Levere, Del Grosso, Thomas, Madigan, & Fortunato, 2019), so opportunities for successful collaboration that CoPs like the Consortium provide have the potential to contribute to opportunities for resource sharing and professional support across member centers.

Teacher members also endorsed a sense of community, but the finding that directors’ perception of SOC was greater than that of teachers indicated that type of participation and engagement contributed to building Consortium SOC (Liu, 2016; Nistor, et al., 2015). Directors were the central focus of the Consortium and had more opportunities to participate in and direct Consortium activities than teachers so it is not surprising that differences in SOC occurred. Still, for both directors and teachers, a critical aspect of Consortium participation seemed to be the resources the Consortium provided. Teachers in the first year and both directors and teachers in the second year rated the needs fulfillment subscale higher than the others. Financial and informational resources are central to early childhood center directors (Ratner et al., 2018; Forry, Simkin, Wessel, & Rodrigues, 2012) and these resources may have in turn helped bring about perceptions of community connections (Owens & Johnson, 2009).

Role of Consortium Trust and Workplace Characteristics in Sense of Community

Given that directors and teachers did endorse a sense of community within the Consortium what factors might have been associated with this perception? We examined two possibilities, trust in the information shared among members within the Consortium and characteristics of the center workplaces outside of the Consortium. Within the workplace we examined the support, both instrumental and relational, that directors and teachers perceived within their centers and the amount of time they worked together. Both information trust and workplace characteristics were positively related to SOC and differences between directors and teachers provided some hints about how each may have contributed to the SOC that emerged within the Consortium.

First, trust in the information provided within the Consortium was high for both directors and teachers, but directors, at least in Year 2, said they trusted the information more than teachers. This contrast might have occurred because of the different amounts and types of participation that directors and teachers had within the Consortium. Access to more diverse experiences within a CoP provides greater information “benefits,” such as more overall information and more positive experiences (Burt, 1992). If this occurred for Consortium directors, then greater trust among group members and in the information provided, as suggested by Evans and Wensley (2009), may have resulted and then promoted a greater sense of community (McMillan, 1996).

Workplace characteristics too were associated with SOC for both directors and teachers but once more we found differences consistent with the idea that the different roles each played within the Consortium and their centers was associated with the formation of SOC within the Consortium. For directors only the SOC influence subscale was positively correlated with center support indicating that directors who felt more supported within their centers thought they had more influence within the Consortium. Perhaps this perception of greater influence occurred because directors believed their perspectives and practices within the center were more accepted or successful among their staff, and, as a result, they might have been more confident in their expertise and willing to share their ideas. Interestingly, McMillan (1996), in a reinterpretation of the original McMillan & Chavis (1986) SOC model, noted that the salient element of influence is trust. We do not persuade others or allow ourselves to be persuaded unless we trust one another in the exchange of information.

For teachers, both perceived support and the number of hours worked within the center were consistently related to SOC (McGinty et al., 2008). Relationships at work require continuity and emerge over time (Blatt & Camden, 2007), so spending more hours at work may have strengthened feelings of support within the center which then extended to the Consortium. These findings also have implications for the role of directors as leaders and their ability to make direct and indirect connections between the Consortium and their centers. Directors play an important role in establishing the workplace environment (Talan et al., 2014) and the relation between SOC in the Consortium and characteristics of the workplace potentially highlight this role. For instance, spending more hours at a center may have provided teachers greater opportunities to learn about the Consortium, leading teachers to endorse stronger Consortium community beliefs (direct effect). Direct effects would reflect specific connections the director might have drawn between Consortium and center activities. Spending more time with colleagues and with the director, especially if teachers felt supported, may also have provided more opportunity for collaboration and developing SOC within the center that extended to the Consortium (indirect effect). Indirect effects would be those director actions that create supportive work environments that positively frame individual expectations or experiences teachers might have within the CoP that could contribute to SOC. A related idea is that greater support and less stress might have freed up cognitive and/or emotional resources for teachers that made it possible for them to be more open to the experiences of the Consortium (Zaheer, McEvily, & Perrone, 1998). Regardless of possible mechanisms, perceptions of community may have reflected not only what happened within the CoP but also the workplace expectations and experiences that people brought with them to the CoP.

Professional Agency: Knowledge Exchange and Consortium Involvement

Higher SOC was associated strongly and consistently with greater willingness to share and adopt knowledge with other CoP members, and more modestly with Consortium involvement. We argued that both of these were important aspects of professional agency (Etalapelto et al., 2013) and potential inputs to changes in practice. Directors and teachers who perceived greater SOC were more likely to say during both years assessed that they would learn from and share knowledge with one another. One of the main reasons teachers say they participate in peer-to-peer professional development networks is to share and seek knowledge (Trust, 2017), but Runhaar and Sanders (2016) note that knowledge sharing can be seen as risky: Sharing what you know might be perceived to reduce a person’s unique value, could lead to being taken advantage of, or could increase negative feedback. Group members who feel part of a community, however, may trust others in the group and believe that knowledge sharing poses fewer risks. If so, SOC may be a gateway to supporting knowledge exchange, which ultimately may contribute to change and improvements in practice and program quality (Gorodetsky & Barak, 2008; Kuh, 2012; Linder 2012).

The one exception to the observed pattern between SOC and knowledge exchange involved directors and emotional connections. Endorsement of stronger relationships within the Consortium was unrelated to director perception of either knowledge sharing or adoption. This is consistent with the idea that professional agency extends beyond feelings of connection to include actions that promote instructional quality and changes in practice (Edwards, 2017; Guo et al., 2011). This isn’t to say that emotional connections or collegiality were not present or that they weren’t important in forming community, but rather that learning and changes in practice that depend on learning require additional intentions and actions. Within organizations, the investments placed in professional development are effective only to the extent that learning occurs and what is learned is put into practice (Sankey & Machin, 2013). SOC that emerged within the Consortium may have been important in leveraging this investment.

SOC membership, or sense of belonging, also was associated with Consortium involvement for both directors and teachers (van Lankveld, Schoonenboom, Kusurkar, Beishuizen, Croiset, & Volman, 2016). Key elements of belonging include faith that one belongs within a group and is accepted by it (McMillan, 1996). This is potentially important because sense of belonging is central to transformation in early childhood educational practice (Tillett & Wong, 2018). Moreover, it was center-wide engagement rather than individual participation that seemed to underlie Consortium participation. Director and teacher SOC ratings predicted center-wide engagement for the group as a whole rather than just their own participation. The primary difference between the center engagement and individual participation measures for the directors was the attendance of teachers at the annual Consortium conference. Perhaps director perceptions of Consortium belonging contributed to direct effects of promoting teacher interest and participation. This interpretation is consistent with the finding that SOC was higher among teachers who spent more hours at their center interacting with one another and the director. Not only do management and employee support predict increased participation in non-mandatory professional development (Sankey & Machin, 2013), but also “social contagion” resulting from others’ motivations can influence participation in organizational activities (Scarapicchia, Sabiston, Andersen & Bengoechea, 2013).

Evaluation Limitations and Future Directions

Although our findings were consistent with established models of SOC and professional agency, it is important to note limitations that render our results descriptive. First, our findings are correlational and an evaluation of one particular community of practice with a small number of members. We provided an illustration of a possible set of relations among the factors explored and possible reasons for the correlations observed, but inferences about cause and effect or direction of relation cannot be drawn. We also were unable to test the relation between SOC and changes in practice or possible outcomes for children. SOC predicts both (Guo et al., 2011); however, we cannot say that this would have occurred here. Another drawback was that those who agreed to be part of the evaluation by definition were Consortium participators. We collected most of the information at Consortium events so we do not have information from non-attendees, which may have led to biases in the sample. Moreover, we collected information over a two-year period. Differences occurred in who participated in each year, but overlap occurred as well. Finally, our evaluation included only the collection of quantitative data, which limits our understanding of the process by which SOC developed. That is, our results offer limited insight into how members came to trust Consortium information or specific mechanisms linking centers characteristics to SOC. Future work should incorporate qualitative and observational measures to better understand these processes.

Summary and Implications

Consistent with the goals of the Consortium, Consortium members reported generally high rates of SOC with directors reporting the highest SOC. SOC differences between director and teacher members of the Consortium speak to the role of collaboration, decision-making and information trust in perceptions about this CoP. At the same time, our findings indicated that experiences within centers may also have contributed. Moreover, SOC appeared important in promoting professional agency within the Consortium that may have extended back to the member centers, leading directors and teachers to influence and reinforce each other’s willingness to participate and learn, consistent with Tabak and LeBron (2017).

These findings have implications not only for the Consortium members but also its leaders. In addition to being intentional in building SOC within the CoP, leaders need to guide directors to create SOC within their own centers and bring the teachings of the CoP “home” to their individual programs, emphasizing both direct and indirect effects of their role within the center. In addition, directors should be encouraged to use within their centers the same practices that promote SOC and authentic learning within the CoP. Intentional promotion of this parallel process (Kuh, 2012) has the potential to increase significantly the effectiveness of professional development if the engagement is authentic. Pre-service teacher training might also include more information about the role of SOC in promoting quality within early childhood programs.

Ultimately, for center programs to implement changes in practice teachers must participate fully in the transformations (Conner, 2015). Consequently, the value of a director CoP like the Consortium may lie not only in providing support and professional development for the directors themselves but also in engaging their teachers (Zinsser, Denham, Curby, & Chazan-Cohen, 2016). Mutual engagement of an entire center may be more likely to lead to changes in practice than individual participation alone (Hadar & Brody, 2010).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Kresge Foundation (R-1607-262370), the PNC Foundation (Grant Codes 25PMW, 25T941), and Dr. McGoron's time was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH110600).

References

- Admiraal W, & Lockhorst D (2012). The Sense of Community in School Scale (SCSS). Journal of Workplace Learning, 24(4), 245–255. doi: 10.1108/13665621211223360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F & Karim M (2019). Impacts of knowledge sharing: a review and directions for future research. Journal of Workplace Learning, 31(3), 207–230. doi: 10.1108/JWL/07/2018/0096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen L, & Kelly BB (Eds.) (2015). Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. Report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC). Washington DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/19401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M, Gluesing J, Ratner H, & Wagner K (2004). The contexts of knowing: natural history of a globally distributed team. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 1–41. doi.org/ 10.1002/job.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black F (2019). Collaborative inquiry as an authentic form of professional development for preschool practitioners. Educational Action Research, 27(2), 227–247. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2018.1452770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt R, & Camden C (2007). Positive relationships and cultivating community. In Dutton JE, & Ragins BR (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation. (pp. 243–264). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Horn R, & King G (2018). The effective implementation of professional learning communities. Alabama Journal of Educational Leadership, 5, 53–59. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ1194725. [Google Scholar]

- Browning P (2014). Why trust the head? Key practices for transformational school leaders to build a purposeful relationship of trust. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 17(4), 388–409. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2013.844275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chou C-H, Wang Y-S, & Tang T-I (2015). Exploring the determinants of knowledge adoption in virtual communities: A social influence perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 35(3), 364–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2015.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb P, & McClain K (2001). An approach for supporting teachers’ learning in social context. In Lin FL & Cooney T (Eds.), Making sense of mathematics teacher education (pp. 207–231). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Conner T (2015). Relationships and authentic collaboration: Perceptions of building a leadership team. Leadership and Research in Education, 2(1), 12–24. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ1088557 [Google Scholar]

- Curbow B, Spratt K Ungaretti A, McDonnell K & Breckler S (2000). Development of the child care worker job stress inventory. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(4), 515–536. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(01)00068-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A (2017). Using and refining the relational concepts. In Edwards A (Ed.), Working relationally in and across practices: A cultural-historical approach to collaboration (pp. 299–310). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Etelapelto A,Vähäsantanen K, Hökkä P, & Paloniemi S (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eun B (2008). Making connections: Grounding professional development in the developmental theories of Vygotsky. The Teacher Educator, 43(2), 134–155. doi: 10.1080/08878730701838934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M, & Wensley A (2009). Predicting the influence of network structure on trust in knowledge communities: Addressing the interconnectedness of four network principles and trust. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(1), 41–53. Retrieved from www.ejkm.com [Google Scholar]

- Forry N, Simkin S, Wessel J, & Rodrigues K (2012). Providing high quality care in low-income areas of Maryland: Definitions, Resources, and challenges from parents and child care providers' perspectives. Child Trends Publication #2012-45. Washington, DC: Child Trends. Retrieved from ERIC, ED538381. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AS, Howes C, Lara-Cinisomo S, & Karoly L (2009). Diverse pathways in early childhood professional development: An exploration of early educators in public preschools, private preschools, and family child care homes. Early Education and Development, 20(3), 507–526. doi: 10.1080/10409280902783483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Rothrauff TC, Thornburg KR, & Mauzy D (2007). Cash incentives and turnover in center-based child care staff. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 363–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorodetsky M, & Barak J (2008). The educational-cultural edge: A participative learning environment for co-emergence of personal and institutional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kadervaek J, Prasta S, Justice L, & McGinty A (2011). Preschool teachers' sense of community, instructional quality, and children's language and literacy gains. Early Education and Development, 22(2), 206–233. doi: 10.1080/10409281003641257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadar H & Brody D (2010). From isolation to symphonic harmony: Building a professional development community among teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(8). 1641–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves A, & Dawe R (1990). Paths of professional development: Contrived collegiality, collaborative culture, and the case of peer coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(3), 227–241. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(90)90015-W [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop D (2013), Knowledge management in organizations: A critical introduction, Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Pianta R, Bryant D, Hamre B, Downer J, & Soliday-Hong S (2008). Ensuring effective teaching in early childhood education through linked professional development systems, quality rating systems and state competencies: The role of research in an evidence-driven system. National Center for Research in Early Childhood Education White Paper. Retrieved from ncrece.org [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M (1993). Teachers' workload and associated stress. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Council for Research in Education. Retrieved from ERIC, ED368716. [Google Scholar]

- Kim M (2013). Constructing occupational identities: How female preschool teachers develop professionalism. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 1(4), 309–317. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ1053969 [Google Scholar]

- Kuh LP (2012). Promoting communities of practice and parallel process in early childhood settings. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33, 19–37. doi: 10.1080/10901027.2011.650787 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsyuruba B, & Walker K (2015). The lifecycle of trust in educational leadership: An ecological perspective. International Journal of Leadership, 18(1), 106–121. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2014.915061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lave J & Wenger E (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levere M, Del Grosso P, Thomas J, Madigan A, & Fortunato C (2019). Approaches to collaboration: Experiences of the early Head Start-child care partnership. Early Education and Development, 30(8), 975–989. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2019.1656319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limlingan M (2011). On the right track: Measuring early childhood development program quality internationally. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 14, 38–47. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ965646. [Google Scholar]

- Linder S (2012). Building content and communities: Developing a shared sense of early childhood mathematics pedagogy. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33(2), 109–126. doi: 10.1080/10901027.2012.675837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S-H (2016). The perceptions of participation in a mobile collaborative learning among pre-service teachers. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(1), 87–94. doi: 10.5539/jel.v5n1p87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail A, Patton K, Parker M, & Tannehill D (2014). Leading by example: Teacher educators' professional learning through communities of practice. Quest, 66(1), 39–56. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2013.826139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madill R, Blasberg A, Halle T, Zaslow M, & Epstein D (2016). Describing the preparation and ongoing professional development of the infant/toddler workforce: An analysis of the National Survey for Early Care and Education data. OPRE Report #2016-16, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/index.html [Google Scholar]

- McGinty AS, Justice L, & Rimm-Kaufman S (2008). Sense of school community for preschool teachers serving at-risk children. Early Education and Development, 19(2), 361–384. doi: 10.1080/10409280801964036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW (1996). Sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 315–325. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW (2011). Sense of community, a theory not a value: A response to Nowell and Boyd. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 507–519. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW, & Chavis DM (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nistor N, Daxecker I, Stanciu D, & Diekamp O (2015). Sense of community in academic contexts of practice: Predictors and effects. Higher Education, 69, 257–273. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9773-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MA, & Johnson BL (2009). From calculation through courtship to contribution: Cultivating trust among urban youth in an academic intervention program. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(2), 312–347. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08330570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AN, Speer PW, & McMillan DW (2008). Validation of a Brief Sense of Community Scale: Confirmation of the principle theory of Sense of Community. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1). 61–73. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner HH, Bocknek EL, Miller AG, Elliott S, & Weathington B (2018). Creating community: A consortium model for early childhood educators. Teacher Development, 22(3), 427–446. doi: 10.80/13664530.2017.1367718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Royal M & Rossi R (1996). Individual-level correlates of sense of community: Findings from workplace and school. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 395–416. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S, & Whitebook M (2012). More than teachers: The early care and education workforce. In Pianta RC, Barnett WS, Justice LM, & Sheridan S (Eds.), Handbook of Early Childhood Education (pp. 92–110). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Runhaar P & Sanders K (2016). Promoting teachers’ knowledge sharing. The fostering roles of occupational self-efficacy and human resources management. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 44(5), 794–813. doi: 10.1177/1741143214564773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sankey KS, & Machin MA (2013). Employee participation in non-mandatory professional development – the role of core proactive motivation processes. International Journal of Training and Development, 18(4), 241–255. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarapicchia T, Sabiston C, Andersen R, & Bengoechea E (2013). The motivational effects of social contagion on exercise participation in young female adults. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35, 563–575. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.748404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremmel AJ, Benson MJ, & Powell DR (1993). Communication, satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion among child care center staff: directors, teachers, and assistant teachers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8(2), 221–233. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80092-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak F, & Lebron M (2017). Learning by doing in leadership education: Experiencing followership and effective leadership communication through role-play. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(2), 199–212. doi: 10.12806/V16/I2/A1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talan T, Bloom P, & Kelton R (2014). Building the leadership capacity of early childhood directors: An evaluation of a leadership development model. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 16(1), 1–10. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ1045231 [Google Scholar]

- Tillett V & Wong S (2018). An investigative case study into early childhood educators' understanding about “belonging”. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(1), 37–49. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2018.1412016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toom A, Pietarinen J, Soini T, & Pyhalto K (2017). How does the learning environment in teacher education cultivate first year student teachers' sense of professional agency in the professional community? Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trust T (2017). Using cultural historical activity theory to examine how teachers seek and share knowledge in a peer-to-peer professional development network. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(1), 98–113. Retrieved from ERIC, EJ1139014. [Google Scholar]

- van Lankveld T, Schoonenboom J, Kusurkar R, Beishuizen J, Croiset G, & Volman M (2016). Informal teacher communities enhancing the professional development of medical teachers: a qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 16, 109. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0632-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger E (1999). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511803932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitebook M, King E, Philipp G, & Sakai L (2016). Teachers' voices: Work environment conditions that impact teacher practice and program quality. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved from ERIC, ED574335. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer A, McEvily B, & Perrone V (1998). Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of inter-organizational and inter-personal trust on performance. Organization Science, 9(2), 141–159. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.2.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zinsser KM, Denham SA, Curby TW, & Chazan-Cohen R (2016). Early childhood directors as socializers of emotional climate. Learning Environments Research, 19(2), 267–290. doi: 10.1007/s10984-016-9208-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]