Abstract

Despite many programs for educating social skills to adolescents with autism, insufficient attention has been paid to examine the optimal conditions and strategies that are important for improvement and generalization of the learned skills. So after reviewing and searching for three PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases, 20 studies were finally analyzed and shared conditions were extracted. The results showed that the most important condition is parental involvement. The rehearsal and practice of social skills, attention to developmental trajectories, strengths and weaknesses of the individual and use of quantitative and qualitative tools are the other circumstances. In conclusion, taking into account these conditions for improvement, generalization and durability of the skills can be helpful.

Keywords: Social skills, autism spectrum disorders, high-functioning, evidence-based practices

Introduction

High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder (HFASD) is characterized by problems with social communication, restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests along with normal cognitive and linguistic abilities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). When people with high-functioning autism reach adolescence, they experience problems such as depression and anxiety, resulting in greater isolation due to awareness of their differences with peers, loneliness and rejection. As a result of isolation and withdrawal from social situations, the weakness in social skills in this group is getting worse and requires intervention (Bifulco et al. 2014, Flynn and Healy 2012)

The literature of social skills interventions backs over 20 years, but the emphasis on assessment and evaluation of these programs is a relatively new area of interest that researchers are trying to explore interventions and extract their conditions and criteria (Fulton 2014). Most of these studies show that the effectiveness of these interventions is low-to-moderate and, for cases that lead to desirable social behavior during or after treatment, it is unclear what techniques, approaches, theories, and specifically what conditions lead to these results (Bellini et al. 2007, Lerner and Mikami 2012).

Investigating the limitation of these interventions, researchers pointed to the lack of appropriate outcome measures (Liu et al. 2018), age-appropriate therapeutic strategies (Choque Olsson et al. 2017) and small sample size (Chung et al. 2016). Also, the generalization of the learned skills to the natural environment and other people except for therapists and the maintenance of these effects is rarely examined and, if examined, the results were not significant (Radley et al. 2017); therefore, researchers are seeking to investigate effective interventions and finding the conditions for the effectiveness of such programs (Seymour 2017).

Many researchers have provided suggestions for increasing the effectiveness of interventions; for example, increasing the number of sample groups to make significant statistical analyses that measure effectiveness (Stichter et al. 2010), considering specific needs of each individual (White et al. 2009), using of evidence-based strategies and interventions (Murphy et al. 2018), and attention to cognitive basics instead of focusing solely on social skills training (Brunsdon and Happé 2014). For example decapitalized that most studies have studied children so far, Hotton and Coles (2016) investigated the recent 20 years studies to improve the social skills of adolescents and adults with autism. The results showed that group social skills training has generally been reported as effective in improving social skills, but the transfer of these effects to the outside world of the treatment environment is not often occurred and different protocols of social skills training must be compared in the real environment of everyday life and the effective mechanisms be recognized (Hotton and Coles 2016).

According to what was said, various studies have emphasized different conditions and each of them has considered certain conditions in the study and examined their role in improving social skills (Laugeson et al. 2012, McMahon et al. 2013), but there is not a systematic review about comparing the conditions of these interventions and investigating optimal conditions for the implementation of social interventions for adolescents with autism, so it is necessary to study what conditions and competencies must exist to achieve most effective interventions? What are the inputs in effective interventions in comparison with low-effective or ineffective programs?

Methods

Scope and inclusion criteria

The current systematic review includes all published studies that focus on social skills interventions on high functioning adolescents with autism and are limited in time from 2000 to 2018. The inclusion criteria for studies were as follows: (1) Articles printed in Persian or English, (2) Articles aimed at improving one or more of the social and communication skills of adolescents in the field of autism either directly or indirectly, (3) The sample group has no other comorbid disorder, (4) The sample group is not pseudo autism or autism spectrum condition (ASC) and (5) The articles in which the research method, the sampling conditions and the characteristics of the sample group are fully specified and can be extracted this data from the text.

Search strategies

To search for studies, internet searches were conducted through PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases. In each of these databases, through the advanced search guide presented in the website of them, the search terms were obtained and interred in the advanced search box. Then the articles were extracted from March 8 to September 2018. Two authors independently extracted data from the Abstract, Methods and Results sections based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was achieved or resolved by a third individual.

Results

Study selection

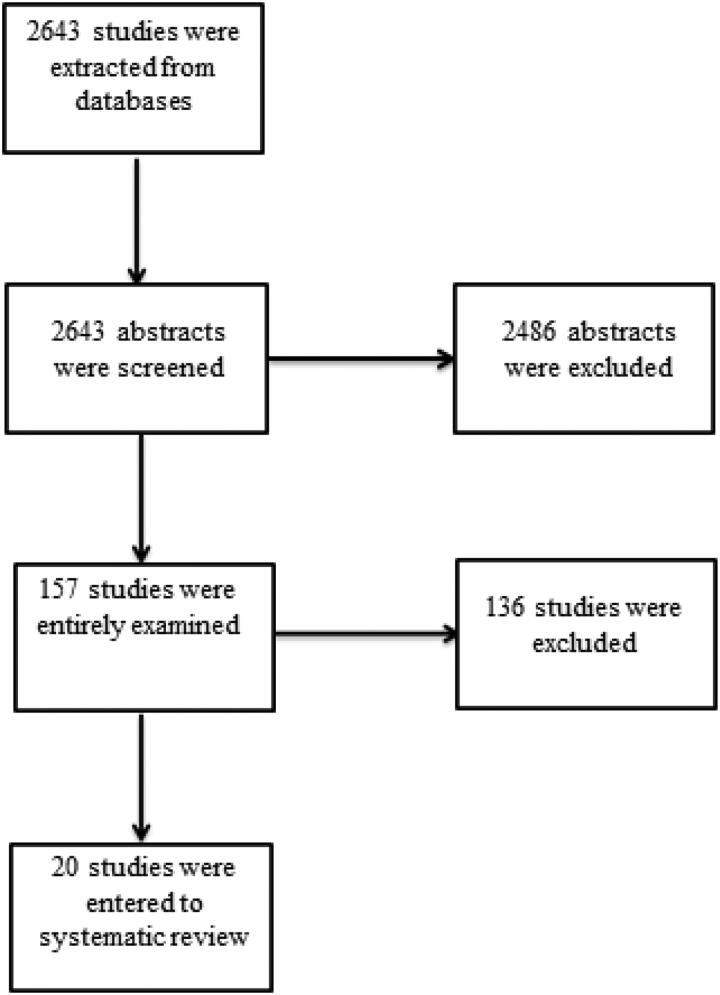

According to the search of databases and other mentioned methods, a collection of 2643 articles was extracted. Their title and abstract were studied and 157 studies seemed appropriate for further investigation. Based on the full text of the study, 20 studies were finally analyzed (Table 1). The steps to select the studies by following Liberati et al. (2009) have been shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining the effects of training social skills to adolescents with high-functioning autism.

| Author(s). (year) | Research approach | Sample size, age range, IQ | Sessions (number and total duration) | Parents involvement | Source of information | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Webb et al. (2004) | Quantitative | 10 boys 12–17 74–126 |

10 weeks 2 sessions per week 13 hrs |

No | Parents | SCORE |

| Tse et al. (2007) | Quantitative | 21 boys and 25 girls (46) 13–18 Above 70 |

12 weeks 12–18 hrs | No | Parents | Behavioral (role play) |

| White et al. (2009) | Quantitative | 2 boys and 2 girls, 12–14 117 |

17 weeks 17 hrs | Yes | Parents | Multi-Component Integrated Treatment (MCIT) |

| Herbrecht et al. (2009) | Quantitative | 15 boys and 2 girls (17) 13–19 93 |

17 sessions, 36 hrs | No | Experts, parents, teachers and double-blind video | KONTAKT1 |

| Laugeson et al. (2009), | Quantitative | 28 boys and 5 girls (33) 13–17 96 |

12 weeks 18 hrs | Yes | Parents | PEERS |

| Stichter et al. (2010) | Quantitative | 29 boys 11–14 77–142 |

10 weeks, twice a week, 20 hrs |

No | Parents | Group-based Social Competence Intervention (SCI) |

| White et al. (2010) | Quantitative | 14 boys and 1 girl (15) 11–14 93 |

16 weeks, 20 hrs | No | Parents, teachers | Social Development Program |

| Lerner et al. (2011) | Quantitative | 8 boys and 1 girl (9) 11–17 Above 70 |

6 weeks, 5hrs weekly,145 hrs | No | Parent, self-report | SDARI2 |

| Lerner and Mikami (2012) | Quantitative | 13 boys 10–12 Above 70 |

4 weeks, 6 hrs | No | Parents, teachers, expert, peers | SDARI |

| Laugeson et al. (2012) | Quantitative | 23 boys and 5 girls (28) 12–17 94 |

14 weeks, 21 hrs | Yes | Parents, teachers | PEERS |

| White et al. (2013) | Quantitative | 23 boys and 7 girls (30) 12–17 100 |

14 weeks, 35 hrs | Yes | Parents | Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skills Intervention (MASSI) |

| McMahon et al. (2013) | Quantitative | 9 boys and 5 girls (14) 10–16 103 |

22 weeks, every two weeks 33 hrs |

No | Parents | Behavioral (Social Skills Training Program) |

| Chen et al. (2015) | Quantitative | 2 boys and 1 girl (3) 10–13 100–101 |

7 weeks, 9 hrs | No | Parents, expert | Augmented reality-based self-facial modeling |

| Chung et al. (2016) | Quantitative | 17 boys and 3 girls (20) 80 |

6 weeks, thrice a week, 18 hrs | No | Parents, experts(fMRI) | Prosocial online game-CBT and offline-CBT |

| Pouretemad et al. (2016) | Quantitative | 12 11–16 Above 70 |

10 weeks, 15 hrs | No | Parents | Behavioral |

| Hood et al. (2017) | Qualitative | 1 boy and 1 girl (2) 15–16 Above 70 |

10 weeks, 15 hrs | No | Self-reports, parents | Behavioral |

| Murphy et al. (2018) | Qualitative | 4 boys 11–15 Above 70 |

9 weeks, 8 hrs | No | Expert observation | Superheroes social skills program |

| Choque Olsson et al. (2017) | Quantitative | 208 boys and 88 girls (296) 8–17 97 |

12 weeks, 18 hrs | Yes | Parents, teachers | KONTAKT |

| Liu et al. (2018) | Quantitative | 43 boys and 6 girls (49) 6–18 Above 70 |

10 weeks, 15 hrs | No | Parents, self-reports | Theory of mind performance training |

| Bambara et al. (2018) | Quantitative | 3 boys and 1 girl (4) 14–20 Above 70 |

12–16 weeks, 3–4 sessions in per week, 15 hrs | No | Teachers, experts | Multicomponent peer-mediated intervention |

Figure 1.

Selection process of studies.

Research characteristics

Effectiveness of interventions

Case 1: Effectiveness, generalization and maintenance

Studies of White et al. (2009), Lerner et al. (2011), Laugeson et al. (2012), Chen et al. (2015) and Hood et al. (2017) showed an improvement, generalization, and maintenance. However In the study of Laugeson et al. (2012), no results were found on the maintenance of the social cognition scale.

White et al. (2009) conducted their study with the hypothesis that reduction of anxiety and then social skills training lead to the improvement of communication skills in autistic adolescents. For this, they first started individual treatment based on the specific needs of subjects, and then, at the same time as the closing sessions, group meetings and parental training began. Of the most important strengths of their intervention can be point to: being standardized, specially developed for adolescents aged 12–17 years, considering evidence-based techniques for improving social skills (modeling, feedback, social reinforcement, etc.) and anxiety treatment (exposure, cognitive challenges, training), including three parts of individual therapy, parenting and group therapy, being a short-term and flexible program that focuses on the needs of each individual.

Lerner et al. (2011) conducted their study aimed to improve the theory of mind, emotion recognition and demonstration, and social skills. Their intervention, SDARI, included the social performance-based program (play and display), emphasis on child-child and child-personnel communication, and the use of other age-appropriate factors such as video games and non-competitive physical activity. They noted that the strength of their study is the use of different tools, different informants and evidence-based strategies such as modeling. Researchers in this study suggested that variables such as drugs and demographic factors must be taken into consideration.

Laugeson et al. (2012) designed PEERS (The Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills) for improving friendship and peer-relationship skills in adolescents. The program includes fourteen 90-minute sessions that are based on peer-peer communication and parent education too. Researchers consider the use of evidence-based strategies, parental involvement, and the presence of healthy peers as benefits of this study, and argue that the reason for the maintenance of post-treatment outcomes is the education of parents to work with their teenager at home.

In their introduction, Chen et al. (2015) stated that the basis for learning social skills is the understanding and demonstrating of facial emotions. First, one needs to identify facial emotions and then other social skills can be taught to him. People will also learn better through video modeling than fixed pictures. Therefore, evidence-based methods such as modeling and practicing were used to comprehend and interpret emotions individually.

The targeted behaviors in Hood et al. (2017) were to improve social skills like entry and greetings. They state in the introduction of their article that it is not clear in the PEERS program how much each person’s performance improves and that the intervention is not based on the deficits of each individual and is predetermined. Therefore, it does not meet adequate flexibility and requires the skills to be repeated during the session and outside of the setting. Furthermore, this is necessary to be sure that the interests of the subjects considered and use them as reinforcements. In this research, healthy peers were participated to practice behavioral skills and strategies such as immediate reinforcement and feedback were used.

Comparison of studies that showed an improvement, generalization, and maintenance indicates that the use of evidence-based strategies such as modeling, parental involvement, the presence of healthy peers, the use of different tools and different reporting providers, and the qualitative evaluation of the skills, repetition, and practice of skills in the natural environment, paying attention to the specific and unique needs and interests of each individual, and also determining the specific target skills, are the requirements for the effectiveness, generalization, and maintenance of treatment plans.

Case 2: Effectiveness and generalization without maintenance

Improvement and generalization of the target skills were seen in the study of Tse et al. (2007), Stichter et al. (2010) and Bambara et al. (2018). However, the maintenance of these studies was not investigated.

Targeted skills in the research of Tse et al. (2007) were awareness of feelings and expression of them, making eye contact, recognizing non-verbal communication, being polite, introducing self to others, starting a conversation, maintaining conversation, ending a conversation, and eating food. They expressed their research strengths as exercising in the natural environment, focusing on the specific needs of the sample group and the high motivation of individuals.

Stichter et al. (2010) designed and implemented a program with the hypothesis that the three structures of social competency, which are specific to autism, are the theory of mind, emotional recognition, and the executive function. When training this group, all three should be considered together, and the cognitive ability is one of the determinants of the outcome of interventions. After the implementation of the intervention, they noted that the reason for improvement and generalization is to pay attention to the individual’s specific deficits and to consider the skills developmentally based on the strengths and weaknesses of the subjects. They suggested that parental involvement should be considered and the quantitative and qualitative data must be collected. A remarkable point in this study was that some parents were trained in this type of intervention.

Bambara et al. (2018) conducted a case study aimed at improving self-assertiveness and initiating and continuing the conversation with others. The researchers stated the strengths of their research as the possibility to use this method for any particular social skill, and the ability to run in any kind of natural environment that requires conversation. They considered the use of live models as the reason for this effectiveness.

Comparison of studies that showed improvement and generalization, but maintenance was not studied or did not exist, concluded that the conditions of effectiveness are similar to case 1, which include: Attention to the needs and specific deficiencies of each individual, considering the training of skills developmentally (milestones), the collection of quantitative and qualitative data, parents participation and training, exercising in the natural environment, using evidence-based strategies such as modeling and involving healthy peers. But the major milestone of these interventions is the lack of examination of the persistence of follow-up outcomes suggesting that future researches should be considered.

Case 3. Effectiveness without generalization and maintenance

The studies by Laugeson et al. (2009), Lerner and Mikami (2012), White et al. (2013), Choque Olsson et al. (2017) and Liu et al. (2018 showed the improvement of social skills, but generalization and maintenance of learned skills were not observed.

Laugeson et al. (2009) conducted the PEERS program. The program emphasizes the presence of healthy peers as models, parental education and exercise in the natural environment. Researchers find their study strengths as following the intervention guidelines, doing pilot before the main implementation of the program, the reduction of anxiety, and attention to the dynamics of the group and the monitoring of the implementation of the program by the assistants. But the generalization and survival of the results were not examined and their program was re-evaluated in 2012 to evaluate the generalization and maintenance of outcomes.

Lerner and Mikami (2012) conducted a study aimed at improving the theory of mind, diagnosis of emotional manifestations and social skills. They used strategies based on behavioral principles, exposure and response situations, interaction with peers, and modeling and teaching of emotional manifestations. The strength of this study was to consider all the qualitative indicators of the clinic, such as randomness, the same conditions at the onset of interventions, methodological necessities, group matching in terms of duration and goals of treatment, personnel training and information acquisition from several sources including adolescents, therapist, teacher, parents, peers and observers. Researchers consider the low number of sessions as the cause of the lack of generalization. But the fact is that this study lasted only 4 sessions, while the stated goals are very wide and this number of meetings cannot be addressed in all aspects.

White et al. (2013) conducted their research aimed at improving social skills and reducing anxiety. The strategies included treating comorbid disorders, teaching emotional manifestations and problem-solving through cognitive-behavioral approaches and modeling were used. These researchers consider the cause of effectiveness as reducing anxiety and using effective strategies, which of course they report the amount of this effectiveness about 16 percent, according to parents. Also, the follow-up session revealed that the improvement in targeted social skills has not remained. They mentioned that this type of intervention wasn’t effective for all group members due to the failure to do homework by adolescents and small sample sizes. It is also suggested that appropriate tools should be used to check the effectiveness of these interventions in small groups.

Target skills in the study of Choque Olsson et al. (2017) were improvement in the understanding of social rules and relationships, the start of social relationships, conversational skills, the recognition and interpretation of verbal and non-verbal social clues, conflict management and the improvement of social communication strategies. The results indicated a low to moderate effectiveness (limited to those who were aware of the conditions of the intervention) that required further study. Also, the two variables of age and sex influenced effectiveness, so that the amount of effectiveness in the groups of teens and girls was more than that of the children and boys, and the reason for this difference was longer education, more motivation, doing homework, neural maturation and better cognitive functions in adolescents. Therefore, they suggest that the educational content must be tailored according to the developmental stages, the number of sessions is over 12, and the provision of feedback, strategies to train and maintain motivation and to continue the program after the end of the course by parents and the individual must be considered.

Objective behavior in the study of Liu et al. (2018) was bullying control by adolescents with autism. To this end, they compared two interventions based on social skills education and the theory of mind training. The results showed that in both groups, bullying was reduced based on self-reports, but according to parents, only in the theory of mind group bullying was significantly decreased. The researchers say that this kind of improvement in the theory of mind group was due to increased understanding and interpretation of social cues and the perception that mental states of individuals differ from each other. Note that this skill is fundamental in learning social skills.

Comparison of studies that showed improvement but not generalization and maintenance showed that as studies that showed improvement and generalization, the absence of parental involvement in the treatment process, the lack of motivation in adolescents resulting in failure to perform assigned homework and lack of practice of skills in the natural environment can reduce the effectiveness and generalization of learned skills.

Case 4: Lack of effectiveness

In studies by Webb et al. (2004), Herbrecht et al. (2009), White et al. (2010), McMahon et al. (2013), Pouretemad et al. (2016), Chung et al. (2016) and Murphy et al. (2018), results showed that social skills training is not effective or in some cases despite the improvement of target skills, the results aren’t statistically significant.

Target skills in the Webb et al. (2004) research were sharing thoughts with others, offering help or admiring others, criticizing in the right way, and exercising self-control. To this end, the SCORE [Share ideas, Compliment others, Offer help or encouragement, Recommend changes nicely, and Exercise self-control] program was implemented with the hypothesis that age-appropriate education, video modeling, role-playing, and constructive feedback play a positive role in intervention. The program has been essentially designed for people with learning disabilities; however, it uses many of the instructional components that have been noted as effective for teaching social skills to adolescents with autism: modeling, guided practice, independent practice, teaching to mastery, and positive feedback. The results were not statistically significant. They noted that the number of sessions must be increased and parental education should be considered to generalization.

In Herbrecht et al. (2009), the results were not statistically significant. They stated the strengths of their research as the use of different people, such as parents, teachers, specialists and double-blind coders to assess the impact of the intervention, and control of drug and other interventions during treatment. They also suggest that individual problems and continuing education based on developmental milestones should be considered.

In White et al. (2010), target behaviors included the diagnosis and expression of emotional manifestations and the learning of the principles and rules of conversation. They used strategies such as pay attention to individual needs, teaching emotional manifestations, modeling, interacting with healthy peers, and using behavioral and cognitive-behavioral principles. The researchers suggested that textual and moderator variables must are considered; different social performance domains, not the entire set, should be investigated, individual differences be taken into account, and parents should be taught to work with their teenagers outside the treatment environment.

In the study by McMahon et al. (2013), the researchers conducted a research with the aim of improving conversational skills, joking and making friends. Strategies such as exposure and response situations, peer interaction, parent education, and practice in the natural environment were used. Unlike Herbrecht et al. (2009), they argue that verbal intelligence does not correlate with a better result of interventions. Researchers stated the weaknesses of their research as follows: not determining that does the responses of participants to peers was relevant and significant? Whether the improvement was due to familiarity with the group or it was the result of the intervention? The coders were aware of the conditions of the intervention, lack of adequate training of coders, lack of differentiation between parallel play and being alone, the uncertainty of the diagnosis of high-functioning autism adolescents, small sample groups, lack of control of participation in other interventions, lack of observational evaluation and the non-standard unstructured playtime. They suggest that, if possible, social skills training should be carried out according to developmental patterns and quantitative and qualitative measures should be considered together.

Pouretemad et al. (2016) used modeling strategies, self-monitoring, self-regulation, and behavioral principles for educating communication, play and collaboration with others and problem-solving. Researchers find that reasons for lack of effectiveness include short time intervention, inappropriate tools, lack of parental involvement and lack of practicing skills. And suggest that sample size must be increased for greater effectiveness; intervention time should be increased, and pivotal cognitive abilities also are addressed.

Chung et al. (2016) examined the results of their research aimed to improve the perception of facial demonstrations. Two groups of online and offline cognitive-behavioral games were examined for the effects of these interventions, and they observed that both groups showed improvement in understanding facial manifestations. In explaining the results, researchers say that the reason for this improvement probably is only the effects of repetition and practice, and the generalization and durability of the results have not been studied. So the results are not reliable.

The study of Murphy et al. (2018) was conducted aimed at expressing requests and needs and learning emotional manifestations. This research was carried out qualitatively and used strategies such as interacting with peers, practicing in the natural environment, and modeling and teaching emotional manifestations. Due to the evaluating effectiveness only in one classroom and the bad experience of dealing with peers and the short time of intervention, Qualitative outcomes were not significant. They suggest that perhaps the reason for not generalization is the education in a different environment.

A comparison of interventions that did not improve social skills and in some cases resulted in partial or inconsistency improvement showed that lack of effectiveness could be due to the lack of attention to the components that are considered effective in interventions. Conclusion of the reasons for these interventions indicates the importance of considering the following components for the improvement and generalization of skills:

Educating parents and participation of them, taking into account the individual’s specific needs, aligning the intervention with strengths and weaknesses of the sample, practicing the required skills outside the treatment environment, using evidence-based strategies for any specific skill, and training with attention to the developmental order of skills.

In most of the studies mentioned above, the importance of sample size, the number of sessions and some other variables have been emphasized. Therefore, to investigate their relationship with the result of the interventions, the correlation between these variables has been presented in Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of correlation between sample and intervention characteristics and the effectiveness, generalization and, maintenance of results.

| The effect type | 1 (Bi) | 2(Bi) | 3 (Bi) | 4(Bi) | 5(Bi) | 6(Bi) | 7(Chi) | 8(Bi) | 9(Bi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| E & G | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.14 | 0.24 | −0.03 | −0.23 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.27 |

| E & G & M | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.2 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0 |

Bi = bi-serial; E = effectiveness; G = generalization; M = maintenance; 1 = number of groups; 2 = total sample size; 3 = Age range; 4 = IQ; 5 = Number of sessions; 6 = duration of intervention; 7 = Parental involvement; 8 = Repeatability of sessions in a week; 9 = Sample size in per group.

As the results of correlation show, parental involvement is very important for effectiveness, but the total number and in per group of the sample, the number of groups, age, IQ, number of sessions, duration of the intervention, and the number of sessions per week have not considerable importance in results of intervention.

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of the present study was to systematically review the effectiveness of social skills training for high- functioning adolescents with autism and emphasizing the analysis of the conditions for implementing the programs. Twenty studies met the criteria for entry into the survey and were analyzed. Of these, 5 studies showed effectiveness, generalization and maintenance in training social skills. Common conditions in these studies were the use of evidence-based strategies such as modeling, parental participation, the presence of healthy peers, the use of different tools and reporters, and the qualitative assessment of the required skills to examine the effectiveness of interventions, repetition and practice of skills in the natural environment, attention to the specific interests and needs of each individual, as well as to the determination of the specific target skills. On the other hand, the limitations and factors that the ineffective programs point out to them that need to be considered are consistent with these components. Therefore, in line with the studies by Mandelberg et al. (2014), Brunsdon and Happé (2014) and Watkins et al. (2017), for conducting every social skills training it is necessary to consider the common effective components of effective social intervention programs. Also the results of previous reviews such as Jonsson et al. (2016) show that the generalizability of interventions in this area is not clear but accurate information about the population is needed. A homogeneous population increases internal validity, but highly selective eligibility criteria can also considerably reduce the applicability of the trial results. The eligibility criteria reported in the included trials mainly concerned age, IQ, aggressive behavior, and severe mental health problems provided that the intervention primarily is intended for high-functioning school-aged children and adolescents. Nevertheless, the study populations might still be highly selective, not representing clinical reality. On the other hand according to Warren et al. (2011) there is not yet adequate evidence to pinpoint specific behavioral intervention approaches that are the most effective for individuals with ASDs. The results of this study showed that it is important to properly define different subtypes of autism to identify specific therapeutic factors. Those with high-functioning autism, for example, people with comorbid disorders should be placed in a separate group. Also, comparing studies that used common programs but with different results showed that despite Herbrecht et al. (2009) and Choque Olsson et al. (2017) both used the KONTAKT program, the Herbrecht et al. (2009) study is superior to Choque Olsson et al. (2017) in terms of the total duration of the intervention (one year) and the use of comprehensive information acquisition resources including experts, parents, teachers, and coaches, the main differences between these two types of interventions are the parental involvement as an active member in adolescent education, and in the second place, the use of evidence-based strategies so that in the study of Choque Olsson et al. (2017), the cognitive and cognitive-behavioral strategies have been used, while the strategies used in the study by Herbrecht et al. (2009) are generally behavioral. Also, the individual difference in the Choque Olsson et al. (2017) study have been considered, and the total of these factors leads to more effectiveness in the study of them. This kind of differences in the implementation of the MASSI intervention by White et al. (2009) and White et al. (2013) is also seen, which the major differences namely the use of effective strategies and parental involvement led to different results.

In the study of Laugeson et al. (2009) and Laugeson et al. (2012) about examining the PEERS program, although the results were different, this difference was in the generalization and sustainability level that was not studied in the study of Laugeson et al. (2009) and do not refers to the actual difference.

In the study of Lerner et al. (2011) and Lerner and Mikami (2012), both of which used the SDARI program, the results showed that in the study of Lerner et al. (2011), educational goals were defined and studied according to the developmental stages and in proportion to the group characteristics; but in the study by Lerner and Mikami (2012), researchers included long-term goals in only four sessions that this period was very short.

In explaining the above findings, it can be stated that once parents participate as active members, they practice at home with their teenagers, as well as the apprentices who need to practice their learned skills, and thus the generalization and maintenance of skills will have occurred. On the other hand, all interventions in the best condition include only a small portion of adolescent life while the adolescent lives at home and with his parents and needs to use the learned skills in the real-life and outside the treatment environment. Therefore, the trial and error occurs outside of the treatment environment, and if the training ends in a positive outcome, the parents must surely practice it in the natural environment of life. This natural environment, as seen in the study of Laugeson et al. (2009, 2012), varies according to the target skill. In this type of training, the target skills are focused on the peer group, so it is necessary to practice in the natural environment with peer groups. Also, children with high-functioning autism do not differ much from their peers in terms of social skills, but when they reach adolescence and don’t show age-appropriate social skills their parents are looking for solutions. In this case, therapists and educators need to first examine the developmental deficiencies through clinical examinations and appropriate scales and teach the social skills step by step based on the order that they don’t acquisition them. Therefore, when a person has not yet learned to make the proper eye contact or cannot recognize a person’s emotions, learning to enter the conversation and understanding the nonverbal demonstrations of the behavior of others are futile and does not yield to favorable results because they have not learned basic skills.

This research has been limited in scope, including the lack of access to some articles and the lack of review of the other review articles in this regard. Similarly, studies vary in terms of the number of details mentioned in the text. For example, some of the researches refer to their exact score on the IQ level; while others only have stated that their sample was high functioning autism adolescents or that the sample group IQ was over 70. While this level of intelligence can be more than 100 that at this level, the person IQ is equal to the average intelligence, but can be only 78, which then has different cognitive characteristics. Therefore, the effects of coders’ and researchers’ judge and mentality on each step affect the extraction of data. In the present research, in different studies, different target skills were mentioned as social skills, but the fact is that the learning of each social skill requires its knowledge and abilities and the amount of required cognitive ability is different for each skill. It is suggested that the researchers, in addition to considering the general conditions for the implementation of the intervention, discussed in the conclusion, also consider the specific conditions for each type of target skill separately. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of examination of the proper conditions for intervention in low-functioning, and with specific disability autistic groups. It is suggested that future researches study the appropriate conditions for low-functioning groups. Also, with randomized controlled trials, assess the role of conditions extracted in this study in combination with each other to improve the social skills of high-functioning adolescents with autism. In the present study, only published studies that have been peer-reviewed were reviewed, suggesting that similar studies should be considered with unpublished studies and other sources of information to obtain less biased results.

Notes

The Frankfurt Social Skills Training

Socio-Dramatic Affective-Relational Intervention

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bambara, L. M., Cole, C. L., Chovanes, J., Telesford, A., Thomas, A., Tsai, S.-C., Ayad, E. and Bilgili, I.. 2018. Improving the assertive conversational skills of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in a natural context. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 48, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, S., Peters, J. K., Benner, L. and Hopf, A.. 2007. A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 28, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco, A., Schimmenti, A., Jacobs, C., Bunn, A. and Rusu, A. C.. 2014. Risk factors and psychological outcomes of bullying victimization: a community-based study. Child Indicators Research, 7, 633–648. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsdon, V. E. and Happé, F.. 2014. Exploring the ‘fractionation’ of autism at the cognitive level. Autism, 18, 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. H., Lee, I. J. and Lin, L. Y.. 2015. Augmented reality-based self-facial modeling to promote the emotional expression and social skills of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choque Olsson, N., Flygare, O., Coco, C., Görling, A., Råde, A., Chen, Q., Lindstedt, K., Berggren, S., Serlachius, E., Jonsson, U., Tammimies, K., Kjellin, L. and Bölte, S.. 2017. Social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, U. S., Han, D. H., Shin, Y. J. and Renshaw, P. F.. 2016. A prosocial online game for social cognition training in adolescents with high-functioning autism: an fMRI study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, L. and Healy, O.. 2012. A review of treatments for deficits in social skills and self-help skills in autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, J. A. 2014. Evidence based social skills interventions for young children with Asperger’s syndrome and the Montessori educational method: an integrative review. Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Herbrecht, E., Poustka, F., Birnkammer, S., Duketis, E., Schlitt, S., Schmötzer, G. and Bölte, S.. 2009. Pilot evaluation of the Frankfurt Social Skills Training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 18, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, S. A., Luczynski, K. C. and Mitteer, D. R.. 2017. Toward meaningful outcomes in teaching conversation and greeting skills with individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50, 459–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotton, M. and Coles, S.. 2016. The effectiveness of social skills training groups for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 3, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, U., Choque Olsson, N. and Bölte, S.. 2016. Can findings from randomized controlled trials of social skills training in autism spectrum disorder be generalized? The neglected dimension of external validity. Autism, 20, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Mogil, C. and Dillon, A. R.. 2009. Parent-assisted social skills training to improve friendships in teens with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeson, E. A., Frankel, F., Gantman, A., Dillon, A. R. and Mogil, C.. 2012. Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: the UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, M. D. and Mikami, A. Y.. 2012. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of two social skills interventions for youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 27, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, M. D., Mikami, A. Y. and Levine, K.. 2011. Socio-dramatic affective-relational intervention for adolescents with Asperger syndrome & high functioning autism: pilot study. Autism, 15, 21–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ionnidis, J. P. A. and Moher, D.. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, W65–W94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.-J., Ma, L.-Y., Chou, W.-J., Chen, Y.-M., Liu, T.-L., Hsiao, R. C., Hu, H.-F. and Yen, C.-F.. 2018. Effects of theory of mind performance training on reducing bullying involvement in children and adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One, 13, e0191271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelberg, J., Laugeson, E. A., Cunningham, T. D., Ellingsen, R., Bates, S. and Frankel, F.. 2014. Long-term treatment outcomes for parent-assisted social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: the UCLA PEERS program. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 7, 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, C. M., Vismara, L. A. and Solomon, M.. 2013. Measuring changes in social behavior during a social skills intervention for higher-functioning children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1843–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A. N., Radley, K. C. and Helbig, K. A.. 2018. Use of superheroes social skills with middle school‐age students with autism spectrum disorder. Psychology in the Schools, 55, 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Pouretemad, H. R., Fathabadi, J., Sadeghi, S. and Shalani, B.. 2016. The effectiveness of social skills training on autism spectrum disorder symptoms in adolescents: a quasi experimental study. Journal of Research in Rehabilitation Sciences, 12, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Radley, K. C., McHugh, M. B., Taber, T., Battaglia, A. A. and Ford, W. B.. 2017. School-based social skills training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 32, 256–268. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, O. P. 2017. Say it again: a case study on improving communication in an autistic adolescent. Linguistics Senior Research Projects. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Stichter, J. P., Herzog, M. J., Visovsky, K., Schmidt, C., Randolph, J., Schultz, T. and Gage, N.. 2010. Social competence intervention for youth with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: an initial investigation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1067–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse, J., Strulovitch, J., Tagalakis, V., Meng, L. and Fombonne, E.. 2007. Social skills training for adolescents with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1960–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Z., McPheeters, M. L., Sathe, N., Foss-Feig, J. H., Glasser, A. and Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.. 2011. A systematic review of early intensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 127, e1303–e1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, L., O’Reilly, M., Ledbetter-Cho, K., Lang, R., Sigafoos, J., Kuhn, M., Lim, N., Gevarter, C. and Caldwell, N.. 2017. A meta-analysis of school-based social interaction interventions for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4, 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, B. J., Miller, S. P., Pierce, T. B., Strawser, S. and Jones, W. P.. 2004. Effects of social skill instruction for high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- White, S. W., Koenig, K. and Scahill, L.. 2010. Group social skills instruction for adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Scahill, L., Oswald, D. and Albano, A. M.. 2009. Preliminary efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment program for anxious youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1652–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Albano, A. M., Oswald, D., Johnson, C., Southam-Gerow, M. A., Kim, I. and Scahill, L.. 2013. Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 382–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]