Abstract

The debate on the pros and cons of employee attachment to social networking sites (SNS) has led to social media policy paralysis in many organizations, and often a prohibition on employee use of SNS. This paper examines corporate users’ attachment to SNS. An analysis of 316 survey responses showed that corporate users’ socialization in large public SNS was steeped in perceived work-related benefits, which in turn nourished their SNS attachment. Social use outperformed informational use in generating perceived work-related benefits from SNS. Weak ties in large heterogeneous networks resulted in strategic and operational benefits, whereas the effects of strong bonding in homogenous networks were limited to operational benefits. The paper contributes to research on SNS use by corporate users and the debate on the effect of SNS use for work. The findings will benefit SNS strategists of organizations and policymakers to exploit the benefit potential of public SNS.

Keywords: Attachment theory, Corporate user, Perceived benefits, Social capital theory, Social networking sites, Uses and gratifications theory

Introduction

In the new millennium, social networking sites (SNS) have greatly impacted human life and the study of SNS has received research attention globally. As per a published report, there were 4.2 billion active users of SNS in 2020, indicating a global penetration rate of 49 percent (Statista, 2021a). SNS users have developed a feeling of attachment towards SNS, replete with comfort-seeking behavior and separation anxiety (Lee, 2013). It has led users worldwide to spend as much as 145 min per day on average on SNS in 2020 (Statista, 2021b). This change in human behavior has baffled the scientific community. Extant research has shown that from the user perspective, a combination of hedonic and utilitarian benefit perception has motivated the use of SNS (Wu & Lu, 2013). Corporate users have formed a significant segment of SNS users. Yet, SNS use, its impact in the workplace, and the nature of SNS attachment for corporate users have remained an under-researched topic (Ali-hassan et al., 2015).

The pros and cons of employee access and use of public SNS at the workplace have been a matter of debate among organizational policymakers and academic researchers (Bizzi, 2018). SNS attachment for employees of organizations has drawn criticism due to unwarranted information leaks, and loss of productivity (Houghton et al., 2020). In the past, scholars have studied employees spending unproductive time on SNS, a phenomenon referred to as cyber-loafing (Glassman et al., 2015). Studies have reported a loss of productivity due to employee engagement on SNS at work (Priyadarshini et al., 2020). Many organizations have blocked employee access to public SNS sites as a part of corporate policy (Glassman et al., 2015). Such policies have obstructed corporate users from using public SNS at work. Figure 1(a) depicts a range of news snippets on the organizational dilemma in allowing employee access to SNS.

Fig. 1.

(a) Sample news snippets, (b) Sample posts from Facebook

As a counterargument, past research has shown that the information systems employed in workplace settings have multiple benefits, such as knowledge integration and innovation (Ngai et al., 2013; Wu & Lu, 2013). Some organizations have implemented enterprise social networks to facilitate employee socialization (Leidner et al., 2018), but most organizations have not invested in enterprise SNS. Corporate users have engaged on public SNS such as Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, irrespective of organizational investment in enterprise SNS. This paper uses the term SNS to denote public SNS. Users of SNS share and obtain information from the sites (Heimbach & Hinz, 2018). Information flow in the online network of relationships allows access to technological know-how. SNS such as Facebook and Twitter offer entertainment as well as purposive value (James et al., 2017). Figure 1(b) depicts a range of posts collected from Facebook that contain information relevant to the job functions of corporate users. This demonstrates the value of Facebook for corporate users. According to a study, 60 percent of employees reported that information found on SNS helped them in decision-making (Bizzi, 2018). The corporate users’ benefit perception from SNS invigorated our academic interest in this area.

Corporate users have employed public SNS for socialization and realization of team goals (Song et al., 2019). In the non-profit sector, users’ functional dependence on SNS determined SNS attachment (Wan et al., 2017). SNS attachment is defined as the degree of users’ loyalty and commitment to SNS. This paper focuses on the work-related benefits from public SNS. Many extant studies on the topic have focused on the firm perspective (Lam et al., 2016; Schniederjans et al., 2013). This paper studies the phenomenon from the corporate user perspective. It explores the corporate users’ views and benefit perception from public SNS and its influence on their SNS attachment. This leads to the first research question (RQ1).

RQ1: Does benefit perception from SNS influence SNS attachment for corporate users?

The social capital theory builds on harnessing the social networks and investing in social relations to derive returns from the marketplace. SNS, being an amalgamation of social networking and internet-based communication, is poised to offer rich social capital benefits. Extant research has shown a positive association between SNS use and the generation of social capital (Zhao et al., 2012). Social capital is a harbinger of strategic benefits derived from the use of technology (Lam et al., 2016). Higher social capital in a stakeholder network has reduced production cycle time, improved quality, and facilitated faster response to regulatory changes (Rottman, 2008). Employees’ social capital generated on SNS has positively influenced firms’ knowledge creation that improved organizational performance (X. Cao, et al., 2015). The higher knowledge management capability has helped firms cope with the competitive challenges in the market (Chuang et al., 2016; Kwayu et al., 2018). This led us to question the role of social capital in generating SNS attachment for corporate users.

RQ2: Does social capital formed on SNS play a determining role in corporate users’ SNS attachment?

A large number of studies on SNS have focused on usage, motivations, and gratification for adoption and usage continuance (J. Cao, et al., 2015; Plume & Slade, 2018). Users have used public SNS for a variety of reasons. Extant information systems research has shown that extrinsic motivations play an important role in determining the usage of utilitarian systems, while intrinsic motivations play a more important role in determining the usage of hedonic systems (Wu & Lu, 2013). SNS allow users to maintain their connections with existing friends and form new connections to increase reach. The technological features of SNS ease the maintenance of a wider social network (Suh et al., 2011). SNS allow faster and more effective information exchange (Hughes et al., 2012) and wider reach as well as increase in communication richness and the quality of information exchange (Ellison et al., 2007). The corporate users’ attitudes and behavior towards systems and information sharing are distinct from general users, and their utilitarian behavioral goals are expected to reflect their usage of public SNS (Thakur & AlSaleh, 2018). This leads to the third research question (RQ3).

RQ3: Is the corporate users’ SNS attachment a function of SNS usage?

A survey of information systems literature on SNS has shown a need to explore corporate users’ social capital generated on SNS and its impact on perceived work-related benefits (Ali-hassan et al., 2015). To address this gap, we designed this study to assess whether corporate users’ SNS attachment emanated from the perceived benefits from SNS. We theorized the relationship between SNS usage, social capital, perceived benefits, and SNS attachment based on attachment theory, social capital theory, and uses and gratifications theory. An analysis of 316 survey responses offered interesting insights about the influence of social capital and perceived benefits on SNS attachment for corporate users. While most organizations employed SNS for informational purposes, our results indicated that the social use outplayed the informational use of SNS as a predictor of social capital and perceived benefits. Extant literature stressed the need to build bonding social capital within a team (Newell et al., 2004). Our analysis showed that the social use of SNS played a predominant role in generating social capital, and bridging social capital showed a stronger effect on perceived benefits compared to bonding social capital. The social capital factors and the perceived work-related benefits largely explained the corporate users’ SNS attachment. This paper contributed these novel findings to academic research on SNS. The practitioners would also find the results useful in defining corporate SNS strategy.

We present the literature review in Sect. 2, the conceptual model and our research hypotheses in Sect. 3, the research methodology in Sect. 4, and the analysis and findings in Sect. 5. The discussion, contributions to theory and practice, and the directions for future research are described in Sect. 6, and our concluding remarks appear in Sect. 7. A summary of related literature is presented in Appendix A.

Theoretical Background

Uses of SNS

The uses and gratifications theory seeks to explain the causes of user engagement with specific media. Information systems scholars have studied the factors influencing the acceptance, impact, and success of information systems with the help of the uses and gratifications theory (James et al., 2017). Past studies have reported that social and information gratifications drive internet usage (Ji & Fu, 2013). SNS are an implementation of social networks on the internet. Social network theory explains human behavior in the form of social relationships and actions in the context of the network (Wellman, 1988). The technological affordances of SNS extend the scope of social networking explained by the social network theory (Lam et al., 2016). The homophily principle suggests that nodes having similar characteristics have a higher propensity of connecting. Users traverse the online network through the referral chain to locate and connect with nodes displaying similar goals or desirable characteristics and join common interest groups. SNS allow users to maintain connections with friends and acquaintances. Consequently, users display a higher degree of connections in SNS compared to offline social networks. The extended opportunities for socialization motivate users to use SNS (Leidner et al., 2018).

SNS provide users an opportunity for self-presentation, and content creation, allow a wider reach of the user-generated content, promote information sharing, exploring, and problem-solving (Chen et al., 2014; Palekar & Sedera, 2015). SNS allow the exchange of enriched content in an asynchronous, omnipresent communication channel to foster trust and contain risk in virtual teams of geographically dispersed organizations (Trier & Richter, 2015). The ability to diffuse information faster and wider dissipating organizational, geographical, socio-cultural, and ethnic boundaries, boost users’ engagement with SNS (Ihm, 2015). Users’ information disclosure behavior on SNS is complemented with their information-seeking behavior (Wu, 2013). SNS allow users to maintain connections with friends from the past and form new friends. The opportunities to socialize with a large network of friends improves the network heterogeneity and widen the opportunity to access a varied set of skills, knowledge, and resources. Extant researchers have reported that SNS serve as a platform for information exchange and community intelligence for day-to-day operations such as logistics and coordination in times of crisis (Huang et al., 2019). Information sharing on SNS for transportation has helped reduce the carbon footprint to improve environmental sustainability (Piramuthu & Zhou, 2016). Network externality, social interaction, and information exchange have contributed to users’ attachment to SNS (Chung et al., 2016). Network externality explores the influence of the purchase behavior of other users in the network on a user. SNS users depend on the network for information on purchase decisions and experiences, and product-related feedback. SNS allow social interactions with like-minded users as well as subject matter experts. The engaging and enriching information exchanges and interactions stimulate a feeling of dependence on SNS. Users get attached to SNS and continue to engage more over time.

SNS enable frequent communication with close friends and associates. The social homogeneity of closed networks improves the bonhomie and facilitates a communication rhythm in the network. The creativity in content generation and the game-like environment contribute to the increase of users’ attachment to SNS (Park et al., 2019). The pleasurable user experiences of SNS motivate higher levels of networking on SNS compared to offline social networks (Suh et al., 2011). Studies have reported that social and informational gratifications were key drivers of user behavior on SNS (Ali-hassan et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2012).

Social Capital on SNS

The social capital theory is widely used in information systems research to study SNS (Ngai et al., 2015). The social capital concept alludes to the potential mobilization of resources based on goodwill knit in the social network fabric (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Access to resources in the social network is a key function of the social capital theory. Individuals leverage social capital to draw on resources from other members of the network (Ellison et al., 2007). Social capital increases users’ sharing and exchange of information and knowledge. Sharing organizational visions and values and understanding common goals contribute to the formation of social capital for the corporate user, which is conducive to the formation and functioning of strategic alliances and buyer–supplier networks (Koka & Prescott, 2002). It eases knowledge capture and its flow in large multilocation and multinational organizations having business functions meshed in global networks of suppliers and other stakeholders (Rottman, 2008). It affects the identification and extraction of tacit knowledge in organizational stakeholders and aids the promotion of corporate citizenship with global outreach and online community commitment (Jeong et al., 2021; Steinfield et al., 2009).

Social capital is typically measured by tie strength, which leads to the bonding and bridging social capital typologies (Williams, 2006). Bonding social capital overlaps with the idea of strong ties. It exists in homogenous networks where people share similar interests and characteristics (Durst et al., 2013). Bridging social capital overlaps with the idea of weak ties. It exists in heterogeneous networks connecting people across social groups and provides access to sets of nonredundant resources. A large number of weak but inclusive ties in a network connecting people from different life situations leads to bridging social capital. Close-knit networks with strong ties, steeped in trust and solidarity, as seen between close friends and family members, lead to bonding social capital. Typically, weak network ties overlap with the idea of bridging social capital, and strong network ties overlap with the idea of bonding social capital (Durst et al., 2013). Both bridging and bonding social capital contribute to organizational performance. Bridging social capital nurtures information and resource exchange, new knowledge, and niche skills (Williams, 2006). It improves affiliations between socially distant heterogeneous sets of people and allows access to scarce knowledge and nurtures innovation (Chuang et al., 2016). On the other hand, bonding social capital nurtures team building, brand loyalty, and access to resources.

Adler and Kwon (2002) have described social capital as a manifestation of the underlying social network. Social capital owns symbiotic relations with social networks. Social networking on SNS nurtures social capital. SNS facilitates the meeting of like-minded people forming communities of common interest and shared goals, often solving each other’s problems (Zhou et al., 2014). This improved interaction generates social capital (Hofer & Aubert, 2013). The formation of new ties and maintenance of a large network of weak ties engenders bridging social capital on SNS. Frequent interactions on diverse topics in a network of strong ties nurture bonding social capital on SNS (Ellison et al., 2007).

Social capital formed on SNS fosters team coordination, and teamwork, and alleviates creativity, leadership, collective learning, and trust to benefit corporate users (Steinfield et al., 2009). Social capital influences employee job performance by mobilizing resources (Ali-hassan et al., 2015). The social capital promotes companionship at work and garners social and informational support (Huang et al., 2019). It prompts knowledge exchange, knowledge integration, and innovation (X. Cao, et al., 2015). It fosters a sense of belonging to the network that harbors knowledge sharing and knowledge acquisition intentions (Zhao et al., 2012), It enhances collective learning and absorptive capacity that yields competitive advantage (Chuang et al., 2016).

Perceived Benefits from SNS

Users’ benefit perception from SNS play a key role in determining users’ intention to use SNS (French et al., 2017). SNS improve firms’ interaction with customers and partners and nourish internal and external collaboration (Lam et al., 2016). Social and cognitive uses of technology have a positive influence on job performance (Ali-hassan et al., 2015). Extant research has shown the benefit perception of corporate users from information systems along strategic and operational dimensions (Lederer et al., 1997). The social ties and information exchange capabilities of SNS serve as a catalyst to enhance success at the workplace and in society (Khan & Krishnan, 2020). Employee use of SNS has been linked to the sustainability of fluid organizations as well as maintenance of team relationships in a virtual environment (Chen & Wei, 2020).

The use of SNS for work may emanate from organizational needs or individual preferences. Several organizations have used SNS for marketing, consumer acculturation, brand building, and strategic positioning (Aswani et al., 2018; Chae & Ko, 2016). Creative advertising on SNS increases customer engagement, and improves purchase intention. Scholars have taken interest in information propagation and knowledge sharing on SNS for competitiveness (Chuang et al., 2016). The faster information dissemination and knowledge-building capabilities of SNS results in operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and access to skills (Lam et al., 2016). Open and informal communication on SNS improves trust and relationship in a stakeholder network, that eases operations, and reduces risks. Free flow of ideas in a diverse network followed by interactive discussions leads to exploration of new ideas and innovation. Common interest groups and online communities in distributed networks mobilizes high-quality knowledge, expertise, and experience to fructify innovation (Moser & Deichmann, 2020). Faster information exchange on SNS facilitates disaster relief operations (Ghosh et al., 2018; Liu & Xu, 2018). The social capital formed on SNS reinforces the knowledge benefits from SNS. Users frequently share knowledge on social networks of weak ties, and the knowledge exchange strengthens the ties (Pan et al., 2015). The information on services, product recommendations, and user reviews on SNS facilitate corporate decision-making for strategic gains (Sadovykh et al., 2015a, b). The flow of information and knowledge spanning organizational boundaries in the public SNS support operational benefits (Osch & Steinfield, 2018).

SNS Attachment

The attachment theory, proposed by Bowlby and Ainsworth, has its roots in a child’s attachment to her parents and caregivers (Bretherton, 1992). In the context of technology, the attachment theory explains human motivations to intentionally and determinedly linger on a technology platform (Friedrich, 2016). An attachment is characterized by separation anxiety, coping, and comfort-seeking in distress (fright, fatigue, or sickness) (Bowlby, 1982). Extant research has reported a sense of belongingness, separation anxiety, and comfort-seeking intention for users of SNS. Users connect people, communities, organizations, and brands on SNS. Extant studies have shown that SNS users tend to display symptoms of anxiety when separated from the sites and networks they are attached to (VanMeter et al., 2015). Users’ perceived compatibility and complementarity with the network exert a positive influence on their identification with the network, reinforce the users’ attachment with SNS, and impact the users’ loyalty to the network.

Information systems researchers have studied users’ attachment to SNS and its consequences using the attachment theory (Park et al., 2019). Scholars have found that the uses and gratifications of technology affected the users’ attachment to the technology (Ji & Fu, 2013). Researchers have studied the influence of SNS interactions and networking attributes (Chung et al., 2016; Palekar & Sedera, 2018), the effect of user attitude on SNS stickiness and SNS attachment (Thakur & AlSaleh, 2018). SNS attachment has played the role of a mediator in the association between social capital and knowledge exchange (Zhao et al., 2012).

VanMeter et al. (2015) have identified a set of social networking factors of SNS attachment and studied the influence of SNS attachment on marketing-related behavior. Wan et al. (2017) have studied the influence of users’ emotional attachment to the content creator on donation behavior using attachment theory. Chung et al. (2016) have studied the effect of different forms of SNS attachment on information sharing behavior in virtual groups. Lee (2013) has studied the influence of attachment-related anxiety on social capital. Scholars have examined SNS attachment-related factors such as belongingness, separation anxiety, and comfort-seeking intentions (James et al., 2017).

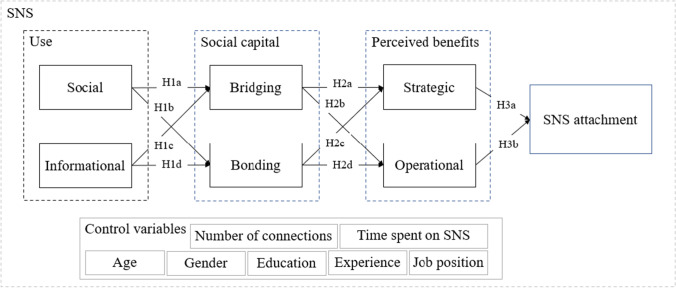

Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

SNS users form connections, join common interest groups, and exchange information on the network. The common interests and pursuits in virtual communities and focus groups on SNS create a sense of participation, relatedness, and belongingness to the network (Khan & Krishnan, 2017; Zhao et al., 2012). The network ties, interactions, exchange of resources, and information contribute to the formation of social capital (Huang et al., 2019). Shared information, opinions, and views on SNS nourish cognitive expectations and build relations, that redefine the social network structure on SNS (Chung et al., 2016). The sharing behavior in an expansive network promotes a large number of weak and distant ties nurturing bridging social capital. It fosters a feeling of trust in strong ties on SNS, thereby building bonding social capital (Lee, 2013). Therefore, the use of SNS influences the formation of social capital (Cummings & Dennis, 2018). Social capital translates to work-related benefits such as information and resource exchange, new knowledge, and niche skills (Steinfield et al., 2009). The social capital and the perception of benefits on SNS induce a sense of gratification and reinforce users’ attachment to it (Chen et al., 2016). The sense of attachment and belongingness on SNS instills affective commitment towards the network (Huang et al., 2019). Based on the theoretical discussions, we formulated the conceptual model for this study as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model

The technological capabilities of SNS foster the formation of new ties, and maintenance of relationships with old acquaintances (Ellison et al., 2007, 2014). It allows users to stay connected with larger social networks to gratify their social aspirations. The weak ties in the large networks engender bridging social capital. The light but frequent communications on SNS strengthen ties between close friends, and foster trust. Direct one on one communication on public SNS contributes to strengthening ties. The stronger ties in the network engender bonding social capital. Some scholars argue that the trust factor dissipates on online networks (Uslaner, 2000). Yet, past studies have reported the positive influence of SNS use on formation of social capital (Jin, 2013). Ellison et al. (2007) have found a strong influence of Facebook use on bridging and bonding social capital. The corporate users connect and build a relationship with knowledge networks, special interest groups, and members corporate bodies and associations to generate bridging social capital. They reach out to customers to build loyal customer networks on SNS (Risius & Beck, 2015). Corporate users leverage SNS to improve relationship and trust with collocated and virtual team members and colleagues to generate bonding social capital (Suh et al., 2011). This leads us to hypotheses H1a and H1b.

H1a: Social use of SNS positively influences the formation of bridging social capital on SNS for corporate users.

H1b: Social use of SNS positively influences the formation of bonding social capital on SNS for corporate users.

Firms have used SNS for marketing, brand building, and strategic positioning of products and services. SNS serve as a platform for fast information diffusion to a large audience to aid marketing campaigns (Risius & Beck, 2015). Customers scan SNS for relevant information on brands and products (Yi et al., 2017). SNS serve as a platform for information sharing and knowledge integration for corporate use (X. Cao, et al., 2015). Users of SNS display information seeking and information sharing behaviors (Chung et al., 2016). The information seekers connect and build a relationship with information providers and vice versa leading to bridging social capital. Open information-sharing facilitates the perception of transparency and promotes trust in the network (Song & Lee, 2016). The trust strengthens the ties in the network. This leads us to hypotheses H1c and H1d.

H1c: Informational use of SNS positively influences the formation of bridging social capital on SNS for corporate users.

H1d: Informational use of SNS positively influences the formation of bonding social capital on SNS for corporate users.

People with strong ties are likely to interact in the same social circle. On the other hand, connections with weak ties are likely to move in varied social circles and be privy to a wide variety of information. The weak ties and the resultant social capital are harbingers of improved performance (Burt, 2000; Granovetter, 1983). Extant research has shown that information from relatively less acquainted but diverse groups of people benefit corporate users (Constant et al., 1996). Information gain from the online social network of weak ties spanning political, religious, gender, ethnic, and age boundaries yield strategic benefits for workers and organizations (Williams, 2006). Common interest groups and online communities mobilize high-quality knowledge, expertise, experience and promote innovation (Moser & Deichmann, 2020). The large networks of weak ties and the corresponding bridging social capital facilitates the flow of knowledge and ideas that promote open innovation. The information flow in such networks eases operations (Koka & Prescott, 2002). SNS provide organizations with higher visibility of people, content, and interactions (Osch & Steinfield, 2018). The increased visibility facilitates impression management that significant impacts firm performance (Schniederjans et al., 2013). This leads us to hypotheses H2a and H2b.

H2a: Bridging social capital on SNS positively influences perceived strategic benefits for corporate users.

H2b: Bridging social capital on SNS positively influences perceived operational benefits for corporate users.

SNS nurture bonding social capital by allowing higher levels of rich interactions that strengthen the trust and bonding between the members. The usefulness of bonding social capital in social and economic contexts is debatable. Bonding social capital can have detrimental effects, especially when the bonding is with weaker members in the network (Durst et al., 2013). Strong ties, lack of diversity, and network homogeneity can influence a behavioral pattern complying with the network, and limit openness to learning and innovation. On the other hand, bonding social capital involves trust and reciprocity in homogenous groups. It involves strong connections and emotional support. It mobilizes substantive support and access to scarce resources (Granovetter, 1983; Williams, 2006). The faster information flow, support, and access to scarce resources bring in operational gains. A stronger connection facilitates the transfer of sophisticated and specialized knowledge. Extant research has shown a positive influence of bonding social capital in the context of business (Horng & Wu, 2020). Strong ties in buyer–supplier networks ease the formation of strategic alliances (Rottman, 2008). This leads us to hypotheses H2c and H2d.

H2c: Bonding social capital on SNS positively influences perceived strategic benefits for corporate users.

H2d: Bonding social capital on SNS positively influences perceived operational benefits for corporate users.

In the digital era, humans have developed an attachment to the technology (Friedrich, 2016). Information and knowledge exchange on SNS boosts employee performance (X. Chen & Wei, 2020). An employee’s image on SNS may promote the employee to brand ambassadorship (Sakka & Ahammad, 2020). Information exchange and bonding on SNS help achieve marketing goals, innovation, and strategic alliances (Wu, 2013) and improve internal operations (Culnan et al., 2010). The perceived usefulness energizes and invigorates users’ sharing behavior (Shang et al., 2017), that represents the users’attachment to SNS (Chen et al., 2019). The common interests and the collective work goals in the online network generate a sense of community (Jeong et al., 2021) and motivate users to intentionally and determinedly stay on SNS. Perceived values and benefits from SNS use generate a sense of satisfaction and belonging to SNS (Turel, 2015). This leads us to hypotheses H3a and H3b.

H3a: Perceived strategic benefits from SNS positively influence SNS attachment for corporate users.

H3b: Perceived operational benefits from SNS positively influence SNS attachment for corporate users.

Figure 3 depicts the hypothesized relationship and the research model.

Fig. 3.

Research model

In this research, characteristics of SNS use (e.g., number of connections on SNS, time spent on SNS) and the corporate users’ demographic attributes (e.g., age, gender, education, experience, and job position) are considered to be control variables.

Research Methodology

We conducted a survey to collect data from corporate users of public SNS. Table 1 presents the operational definition of the research constructs. Following the approach adopted by scholars in the past, our focus is on public SNS rather than on any specific platforms (such as Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.). (VanMeter et al., 2015). We provided examples of SNS (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, WhatsApp, WeChat, and Instagram,) in the questionnaire to make the term clear and succinct.

Table 1.

Operational definition of constructs

| Construct | Definition | Related study |

|---|---|---|

| Social use | The social use of SNS focuses on establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships | (Hu et al., 2017; Hughes et al., 2012) |

| Informational use | The informational use of SNS focuses on accessing timely and relevant information in solving specific problems | (Hu et al., 2017; Hughes et al., 2012) |

| Bonding social capital | The form of social capital that ensues when strongly tied members in the social network provide emotional or substantive support for one another | (Williams, 2006) |

| Bridging social capital | The form of social capital that ensues from weak ties in the social network and contributes to broadening social horizons, world views, and enhancing opportunities for information and resources | (Williams, 2006) |

| Perceived strategic benefit | Organizational ability to outperform competitors gained through unique products, attributes, and resources | (Lederer et al., 1997; Piris et al., 2004) |

| Perceived operational benefit | Organizational ability to perform activities better than competitors and cost-effectively deliver products or services ensuring high-quality adherence | (Lederer et al., 1997; Piris et al., 2004) |

| SNS attachment | A measure of the user’s perception of his/ her degree of attachment with SNS | (Ellison et al., 2007; Friedrich, 2016) |

Research Instrument

The instruments for testing the research hypotheses and model were developed by modifying existing validated scales to fit the research context. The research instrument contained Likert scale items, encoded into numeric integers 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 corresponding to ‘strongly agree’. The research instrument was pilot tested on a small group of respondents before the actual survey. It was independently reviewed by three experts. Interrater reliability (kappa = 0.82) was found to be high (Landis & Koch, 1977). The scale items “I use SNS to keep in touch with friends”, and “I use SNS primarily for socializing” measured the users’ intention of establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships on SNS. The items “I use SNS to find and spread information”, and “I use SNS to keep abreast of current events” captured the users’ intention of using SNS for information diffusion and information foraging. Bridging social capital is inclusive as it involves weak ties with a large network (Putnam, 2000; Williams, 2006). The scale items “Interacting with people on SNS makes me feel like part of a larger community”, and “Interacting with people on SNS gives me new people to talk to” captured the inclusiveness and expansive aspects of the network associated with bridging social capital. Bonding social capital engenders emotional support, access to scarce or limited resources, and ability to mobilize solidarity (Williams, 2006). The scale items “The people I interact with on SNS would put their reputation on the line for me” and “The people I interact with on SNS would share their last rupee with me” were aligned to the solidarity and access to scarce resources attributes of bonding social capital. The item “At work, SNS helps me to provide new products or services to customers” span competition, competitiveness, and product differentiation which are the essentials tenets of strategic benefit (Lederer et al., 1997; Piris et al., 2004). The faster information dissemination and knowledge-building capabilities of SNS results in operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness (e.g., reduce cost of travel due to online interactions), and access to skills (optimize utilization of workforce). It eases operations and reduces risk (Lam et al., 2016; Lederer et al., 1997; Piris et al., 2004). The items “At work, SNS helps me to enhance employee productivity or business efficiency” and “At work, SNS helps me to provide greater data or software security” represent the productivity, quality, and security aspects of operational benefits. As per attachment theory, attachment is characterized by belongingness, separation anxiety, coping, and comfort-seeking in distress (e.g., fright, fatigue, or sickness) (Bowlby, 1982). Emotional attachment to SNS induces a feeling of pride and identification with the network (Dekker, 2007). SNS attachment items in the scale are related to a sense of pride and identification with SNS (“I am proud to tell people I'm on SNS.”), belonging (“I feel I am part of SNS community.”), and separation anxiety (“I would be sorry if SNS shut down.”) tenets of the attachment theory (Bretherton, 1992).

The uses and gratifications from SNS vary by user demography. Extant research has shown differences in SNS use based on age, gender, educational qualification, work experience, and job position, (Chen & Wei, 2020; Liu et al., 2020). The questionnaire collected the above demographic information from corporate users. Extant research has shown that SNS usage patterns such as the extent of usage, and the number of connections affected SNS behavior and gratifications (Chen & Wei, 2020; Lee et al., 2018). The questionnaire collected data on the number of connections on SNS and the duration of SNS use from the respondents. Age, gender, education, work experience, job position, number of connections, and time spent on SNS were used as control variables in the analysis.

Sample

The research focused on the organizational outcome from SNS. The target population was SNS users who were working professionals. An individual user of public SNS sites and employed in an Indian firm formed the sampling unit. The survey questionnaire was administered to 1615 working professionals through Google forms. Participation in the survey was optional. 346 participants responded. 30 responses were discarded due to incompleteness and other anomalies. 316 responses were used for the analysis. Survey respondents were located across Indian metro cities and some non-metro cities covering most major business hubs in India. The sample spanned multiple industry sectors (information technology, banking and financial, manufacturing, retail, and others) and job functions (information technology, engineering, human resources, marketing, finance and accounting, operations). Table 2 presents the profile of the respondents. T-tests were conducted to compare the early responses with the late responses. No significant difference between the early and late responses were observed and this eliminated the presence of non-response bias (Armstrong & Overton, 1977).

Table 2.

Profile of survey respondents

| Characteristic | Class | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 + | 2 | 0.6 |

| 50 to 60 | 8 | 2.5 | |

| 40 to 50 | 76 | 24.1 | |

| 30 to 40 | 124 | 39.2 | |

| 20 to 30 | 106 | 33.5 | |

| Gender | Male | 265 | 83.9 |

| Female | 51 | 16.1 | |

| Educational qualification | Doctoral degree | 6 | 1.9 |

| Post-graduation | 181 | 57.3 | |

| 4-year college | 124 | 39.2 | |

| 2-year college | 4 | 1.3 | |

| High school | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Job position | Board Member | 9 | 2.8 |

| Senior Management | 44 | 13.9 | |

| Middle Management | 116 | 36.7 | |

| Junior Management | 59 | 18.7 | |

| Others | 88 | 27.8 | |

| Work experience | More than 20 years | 48 | 15.2 |

| 12—20 years | 83 | 26.3 | |

| 8—12 years | 66 | 20.9 | |

| 4—8 years | 65 | 20.6 | |

| Less than 4 years | 54 | 17.1 |

Analysis

The raw data showed an average of 457 connections on SNS per user with 23 percent of the survey respondents reporting more than 500 connections. On average, the users spent 41 min on SNS every day. We used the technique of structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze the data for both the measurement model and the path model. The SEM is a multivariate statistical technique that is commonly used to measure associations between constructs, and is well suited to simulate real-world processes involving complex mathematical modeling (Gefen et al., 2000). It performs simultaneous maximum likelihood estimation of the relationships between constructs and the measured variables and among latent constructs (Hair et al., 2013).

Scale Validation

We conducted the principal component analysis (PCA) followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the data to examine the factorial validity of the scale. Table 3 presents the results of the PCA.

Table 3.

Results of principal component analysis

| Item code | Item | Social use | Informational use | Bonding social capital | Bridging social capital | Perceived strategic benefit | Perceived operational benefit | SNS attachment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SocUse1 | I use SNS to keep in touch with friends | 0.575 | ||||||

| SocUse2 | I use SNS because my friends do | 0.910 | ||||||

| SocUse3 | I use SNS primarily for socializing | 0.491 | ||||||

| InfUse1 | SNS is primarily for information | 0.731 | ||||||

| InfUse2 | I use SNS to find and spread information | 0.700 | ||||||

| InfUse3 | I use SNS to keep abreast of current events | 0.644 | ||||||

| BoSC1 | If I needed an emergency loan of Rs. 5000, I know someone on SNS I can turn to | 0.825 | ||||||

| BoSC2 | The people I interact with on SNS would put their reputation on the line for me | 0.749 | ||||||

| BoSC3 | The people I interact with on SNS would share their last rupee with me | 0.787 | ||||||

| BrSC1 | Interacting with people on SNS makes me feel like part of a larger community | 0.560 | ||||||

| BrSC2 | Interacting with people on SNS makes me feel connected to the bigger picture | 0.600 | ||||||

| BrSC3 | Interacting with people on SNS reminds me that everyone in the world is connected | 0.690 | ||||||

| BrSC4 | Interacting with people on SNS gives me new people to talk to | 0.713 | ||||||

| PStrBen1 | At work, SNS help me to provide new products or services to customers | 0.784 | ||||||

| PStrBen2 | At work, SNS help me to enhance competitiveness or create strategic advantage | 0.804 | ||||||

| PStrBen3 | At work, SNS help me to enable the organization to catch up with competitors | 0.784 | ||||||

| POpBen1 | At work, SNS help me to improve the information for operational control | 0.609 | ||||||

| POpBen2 | At work, SNS help me to save money by avoiding the need to increase the workforce | 0.819 | ||||||

| POpBen3 | At work, SNS help me to save money by reducing travel costs | 0.859 | ||||||

| POpBen4 | At work, SNS help me to allow previously infeasible applications to be implemented | 0.805 | ||||||

| POpBen5 | At work, SNS help me to enhance employee productivity or business efficiency | 0.721 | ||||||

| POpBen6 | At work, SNS help me to provide greater data or software security | 0.626 | ||||||

| SNSAtt1 | SNS is part of my everyday activity | 0.868 | ||||||

| SNSAtt2 | I am proud to tell people I'm on SNS | 0.748 | ||||||

| SNSAtt3 | SNS has become part of my daily routine | 0.859 | ||||||

| SNSAtt4 | I feel out of touch when I haven't logged onto SNS for a while | 0.516 | ||||||

| SNSAtt5 | I feel I am part of SNS community | 0.588 | ||||||

| SNSAtt6 | I would be sorry if SNS shut down | 0.804 | ||||||

| KMO = 0.917, Bartlett test of sphericity Sig. < 0.001, Total variance explained = 72.502% | ||||||||

The PCA yielded seven factors with eigenvalues above 1, and these factors explained 72.502% of the variance. The item loadings supported factors in the original scale and were significant (Hair et al., 2013). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity produced a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic of 0.917 that was significant at the 0.001 level, indicating the appropriateness of using the PCA for adequacy of data. The results of the factorial validity examined by CFA are shown in Table 4. Factor loadings for the items were significant and above the recommended factor loading of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013), except for one factor which was above the 0.4 level. The CFA model fit indices demonstrated a good fit between the model and the data (χ2/df = 1.854; root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) = 0.052; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.949; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.887; normed fit index (NFI) = 0.896; and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.939).

Table 4.

Scale properties

| Construct | Item code | CFA loading | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social use | SocUse1 | 0.817*** | 0.726 | 0.751 | 0.686 |

| SocUse2 | 0.417*** | ||||

| SocUse3 | 0.709*** | ||||

| Informational use | InfUse1 | 0.687*** | 0.804 | 0.780 | 0.902 |

| InfUse2 | 0.784*** | ||||

| InfUse3 | 0.806*** | ||||

| Bonding social capital | BoSC1 | 0.764*** | 0.764 | 0.768 | 0.808 |

| BoSC2 | 0.671*** | ||||

| BoSC3 | 0.743*** | ||||

| Bridging social capital | BrSC1 | 0.739*** | 0.854 | 0.829 | 0.947 |

| BrSC2 | 0.814*** | ||||

| BrSC3 | 0.761*** | ||||

| BrSC4 | 0.775*** | ||||

| Perceived strategic benefit | PStrBen1 | 0.817*** | 0.907 | 0.761 | 0.928 |

| PStrBen2 | 0.919*** | ||||

| PStrBen3 | 0.890*** | ||||

| Perceived operational benefit | POpBen1 | 0.833*** | 0.895 | 0.867 | 0.825 |

| POpBen2 | 0.723*** | ||||

| POpBen3 | 0.673*** | ||||

| POpBen4 | 0.761*** | ||||

| POpBen5 | 0.816*** | ||||

| POpBen6 | 0.731*** | ||||

| SNS attachment | SNSAtt1 | 0.797*** | 0.895 | 0.877 | 0.896 |

| SNSAtt2 | 0.778*** | ||||

| SNSAtt3 | 0.783*** | ||||

| SNSAtt4 | 0.689*** | ||||

| SNSAtt5 | 0.826*** | ||||

| SNSAtt6 | 0.621*** |

Note: *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

Cronbach’s alpha (a measure of reliability) for the constructs were above the required value of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2013) for all constructs in the model. Composite reliability (a measure of internal consistency) of all constructs was above the required value of 0.7 (Hair et al., 2013). The average variance extracted (AVE) for the constructs were above the threshold value of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2013) and satisfied the requirement for convergence validity. Table 5 presents the discriminant validity. The square root of AVE was larger than any correlation among the latent constructs, which satisfied the Fornell–Larcker criterion for discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 5 showed that the correlations were significant and, in the direction, consistent with the theory, which established the nomological validity for the constructs in this study. The study adopted procedural measures to avoid common method bias. The order of items in the questionnaire was intermixed to reduce item context effects (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The personally identifiable question (email id) was kept optional, to help reduce participant apprehension. Harman’s single-factor test showed that a single factor explained 36.89% of the variability, which was less than 50%. This eliminated the possibility of common method bias.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity

| Construct | Social use | Informational use | Bonding social capital | Bridging social capital | Perceived strategic benefit | Perceived operational benefit | SNS attachment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social use | 0.828 | ||||||

| Informational use | 0.676 | 0.950 | |||||

| Bonding social capital | 0.207 | 0.112 | 0.899 | ||||

| Bridging social capital | 0.863 | 0.754 | 0.389 | 0.973 | |||

| Perceived strategic benefit | 0.376 | 0.591 | 0.160 | 0.476 | 0.963 | ||

| Perceived operational benefit | 0.382 | 0.501 | 0.293 | 0.497 | 0.762 | 0.908 | |

| SNS attachment | 0.769 | 0.62 | 0.261 | 0.762 | 0.451 | 0.427 | 0.947 |

Note: Non-diagonal cells depict correlation, diagonal cells depict square-root of AVE

Table 6 provides the descriptive statistics for the constructs of the model.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics

| Construct | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Social use | 3.363 | 0.865 |

| Informational use | 3.552 | 0.904 |

| Bonding social capital | 3.392 | 0.947 |

| Bridging social capital | 2.159 | 0.810 |

| Perceived strategic benefit | 3.313 | 0.997 |

| Perceived operational benefit | 3.009 | 0.878 |

| SNS attachment | 3.368 | 0.933 |

Model Testing

The path model was created with a Maximum Likelihood estimate, a bootstrap sample of 5000, and a bootstrap confidence interval of 95 percent. The model was over-fitted (degrees of freedom > 0). Figure 4 depicts the results of the path analysis. The path model showed a good fit χ2/DF = 2.407, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.913, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.067, and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.900. These values satisfied the requirements for acceptance of the model (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Fig. 4.

Results of the SEM analysis. Note: *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

The path analysis showed a significantly positive influence of social use of SNS on bridging social capital (H1a: β = 0.794; p-value < 0.001) and bonding social capital (H1b: β = 0.595; p-value < 0.001). It indicated that socialization on SNS engendered social capital for the corporate user. From the organizational perspective SNS could be used to improve the relationship between stakeholders and foster team spirit, especially in distributed and virtual team settings. The informational use of SNS showed a significantly positive influence on bridging social capital (H1c: β = 0.214; p-value < 0.05), but significantly negative influence on bonding social capital (H1d: β = -0.291; p-value < 0.05). Information exchange on SNS too generated bridging social capital for the corporate user.

The bridging social capital formed on SNS showed a significantly positive influence on perceived strategic benefit (H2a: β = 0.493; p-value < 0.001) and perceived operational benefit (H2b: β = 0.450; p-value < 0.001). SNS harbored weak ties and organizations could leverage the corporate users’ network of weak ties for strategic and operational benefits. The bonding social capital formed on SNS showed a significantly positive influence on perceived operational benefit (H2d: β = 0.135; p-value < 0.05) but its influence on perceived strategic benefit (H2c: β = -0.018 n.s.) was not significant. Organizations could utilize corporate users’ strong ties maintained on SNS for operational benefits, but these ties could be detrimental for achieving strategic goals. Both perceived strategic benefit (H3a: β = 0.217; p-value < 0.05) and perceived operational benefit (H3b: β = 0.185; p-value < 0.05) showed significant positive influence on SNS attachment. This indicated that the perceived work-related benefits positively influenced corporate users’ attachment to public SNS. Organizations could use this finding in updating their policy on the use of public SNS at work.

The path analysis showed significantly positive indirect effect of social use on perceived strategic benefit (indirect effect = 0.438; p-value < 0.05), perceived operational benefit (indirect effect = 0.381; p-value < 0.05), and SNS attachment (indirect effect = 0.164; p-value < 0.05). Bridging social capital showed significantly positive effect (indirect effect = 0.190; p-value < 0.05) on SNS attachment. The model explained 90.3% variability in bridging social capital, 18.0% variability in bonding social capital, 30.5% variability in perceived strategic benefit, 31.1% variability in perceived operational benefit, and 46.1% variability in SNS attachment.

The control variables in the model, namely, characteristics of SNS use (e.g., number of connections on SNS, and time spent on SNS) and the corporate users’ demographic attributes (e.g., age, gender, education, experience, and job position) did not show significant influence on the model constructs, though there were a handful of exceptions. The number of connections was positively associated with perceived strategic benefit (β = 0.190; p-value < 0.001) and perceived operational benefit (β = 0.185; p-value < 0.01) from SNS. Time spent on SNS was positively associated with SNS attachment (β = 0.491; p-value < 0.001). Gender was positively associated with SNS attachment (β = 0.128; p-value < 0.01). The data showed significant difference in the perceived benefits (both strategic and operational) for different age groups. The perceived benefits from SNS for the younger age group were significantly higher than the older age group. The multigroup analysis showed that SNS attachment for the younger age group was influenced by perceived strategic benefit and not by perceived operational benefit. For the older age group, the observation was opposite. The older age group did not perceive bonding social capital from socialization on SNS, nor did they perceive significant positive operational benefit from bonding social capital formed on SNS. The more frequent users of SNS perceived higher benefits from SNS (both strategic and operational), higher bridging social capital and higher SNS attachment compared to the less frequent users. The analysis also showed that SNS attachment for less frequent users of SNS was not influenced by the perception of benefit.

The analysis shows work goals as a significant motivation towards SNS attachment for corporate users. The results show that the social and informational use of SNS contributed to SNS attachment for corporate users mediated by social capital and perceived benefits. The social and informational use of SNS contributed to social capital formation, albeit differently. The social use of SNS had a strong positive effect on the formation of bridging and bonding social capital. Hence, hypotheses H1a and H1b were supported. The informational use of SNS showed a weaker positive effect on bridging social capital and a significant but negative effect on bonding social capital. Hence, hypothesis H1c was supported but hypothesis H1d was not supported. Users indulge in information-seeking behavior from new network nodes in a heterogeneous SNS network. User activity on SNS is less geared towards building trust and solidarity that are related to formation of bonding social capital (Steinfield et al., 2009). This justifies the significant and negative effect of informational use of SNS on generation of bonding social capital. The social and informational use of SNS contributed largely to the formation of social capital on SNS for corporate users. The social and informational use of SNS showed a higher effect on the formation of bridging social capital compared to bonding social capital. The difference in the formation of bridging and bonding social capital on SNS matched the findings of past studies (French et al., 2017).

The analysis showed different perceived outcomes from bridging and bonding social capital formed on SNS. The bridging social capital showed strong positive and significant influence on strategic and operational benefits perceived by the corporate users. Hence, hypotheses H2a and H2b were supported. Bonding social capital showed a significant and positive effect on perceived operational benefit, but its effect on perceived strategic benefit was negative, though not significant. Hence, hypothesis H2c was not supported but hypothesis H2d was supported. Scholars have shown that bonding social capital can have detrimental effects (on health), especially when the bonding is with disadvantageous nodes in the network (Durst et al., 2013). Our study indicated weaker effects of bonding social capital on perceived work-related benefits for corporate users. This confirmed that social capital formed on SNS played a determining role in corporate users’ benefit perception from SNS.

Extant studies have shown that a firm’s SNS initiatives yielded innovation capability and operational benefits (Lam et al., 2016). In our analysis, SNS use showed a stronger association with perceived strategic benefit compared to perceived operational benefit mediated by social capital. It indicated that the corporate users’ usage of SNS was related to the benefit perception from SNS. The perceived strategic and operational benefits showed a significant and positive influence on SNS attachment. Hence, hypotheses H3a and H3b were supported. It confirmed that the benefit perception from SNS influenced SNS attachment for corporate users. The perceived strategic benefit showed a stronger influence on SNS attachment compared to the perceived operational benefit.

In summary, the results brought to light several novel insights about the use of public SNS at work. The corporate users perceived the social networking capability (social use) as a powerful motivation for SNS use. The corporate users found that the socialization with new acquaintances and weak connections (bridging social capital) steeped in network heterogeneity on SNS as more useful than strong bonding in closed networks (bonding social capital). The bridging social capital formed on public SNS (beyond the organizational boundary) showed strong work-related benefits along the strategic and operational dimensions. Finally, the corporate users associated their SNS attachment with work-goals, which indicated a predominantly utilitarian usage goal.

Implications of the Study

Academic Implications

Information systems scholars have emphasized the need to study the impact of SNS on organizations. The literature review (Appendix A) has shown a gap in the study of the use of public SNS by corporate users and its perceived benefits in the workplace. This paper contributes to the scant literature on corporate users’ SNS usage behavior, and benefit perception from SNS. This paper proposed and empirically tested a set of theoretically grounded hypotheses involving social capital and perceived benefit from SNS use, and its influence on SNS attachment for corporate users. The results indicated that the uses of public SNS and the gratifications derived by corporate users are related to the work-goals. SNS attachment is influenced by gratifications from work-related benefits.

Most studies on social capital formation on SNS have focused on a specific platform, such as Facebook, Twitter, or enterprise SNS. In this paper, we studied social capital formation on public SNS as a whole. Extant research on corporate use of SNS have focused largely on information and knowledge exchanges (Cummings & Dennis, 2018; Wan et al., 2017). Our findings indicated a stronger effect of social use of SNS on social capital formation for corporate users compared to informational use. The social use of SNS showed a significant and positive indirect effect on perceived benefit and SNS attachment. The indirect effects of informational use on perceived benefit and SNS attachment were positive but not significant. The importance of social use of public SNS for corporate users is a major contribution of this paper to academic literature.

Our analysis showed that bridging and bonding social capital formed online worked differently for corporate users. SNS use was strongly associated with the formation of bridging social capital, and the bridging social capital on SNS showed a strong influence on perceived benefit in terms of work goals. This supported the theory of the strength of weak ties on SNS. The social and informational use of SNS showed a weaker (not significant for informational use) effect on the formation of bonding social capital. Further, the bonding social capital showed relatively weaker influence on perceived benefit and SNS attachment compared to bridging social capital. This supported findings from similar studies on bonding social capital (Kim et al., 2016). Extant research has emphasized the need to create strong bonds internally within teams for effective knowledge integration (Newell et al., 2004). Our findings indicated that strong ties in homogenous groups, formed by close associates and within teams in the case of corporate users, constrained information and knowledge needed for strategic benefit, and produced lower operational benefit compared to bridging social capital.

Previous studies on SNS attachment often treated it as a predictor variable (Chen et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2017). In this study, we modeled SNS attachment as an outcome of SNS use, social capital formed on SNS, and the perceived strategic and operational benefit. Our findings indicated that the social capital and the perceived work-related benefit motivated the corporate users of public SNS to intentionally and determinedly linger on them. The public SNS allowed the corporate users to reach out to an audience beyond the organizational boundaries to access information, knowledge, and resources to enable them to innovate products and services and achieve operational goals. The opportunities to socialize with a large network of present and past friends improved the network heterogeneity and widened the opportunity to access a variety of ideas and resources. We theorized that this utilitarian view of SNS reinforced the corporate users’ sense of belonging to SNS, and introduced separation anxiety. This is a unique contribution of this paper.

Practical Implications

While extant literature largely discussed the informational benefit of public SNS for firms, our analysis indicated that social use had a stronger influence on benefit perception from SNS. It indicated that corporate users of public SNS perceived work-related benefit from SNS. The benefit perception emanated from social use as well as informational use. Further, the corporate users' SNS attachment resulted from the benefit perception. Socializing with heterogeneous groups increased corporate users’ access to diverse sets of ideas, information, and knowledge. There is a general belief that hedonic motivations drive SNS use and user attachment to SNS and that SNS use decreases productivity (Turel, 2015; Wu & Lu, 2013). Most organizations block employee access to public SNS from the organizational device and network. The analysis provided a different perspective about the organizational benefit of SNS use for corporate users to organizational policymakers. It could influence their policymaking about employee access to public SNS.

Researchers have stressed the need to develop bonding social capital in project teams for operational gains (Newell et al., 2004). Our analysis showed that the corporate users perceived a stronger effect of bridging social capital on operational benefit. The bridging social capital showed a strong effect on perceived strategic benefit too. Managers engaged in team-building activities to improve bonding with the team for better productivity. Human resource managers and line managers needed to encourage team members to socialize with heterogeneous groups and form bridging social capital. Usually, the enterprise social networks that allow access to employees only, are more homogenous and are bounded by similar work environment, project, information, resources, objectives, and goals (Leidner et al., 2018). Practitioners involved in implementing enterprise SNS should design policies so that it allowed employees to socialize with heterogeneous groups and build bridging social capital.

Organizational SNS strategists frequently employed SNS for external-facing activities such as branding, consumer acculturation, and marketing activities (Chae & Ko, 2016; Kizgin et al., 2018). Our analysis showed that the corporate users perceived significant positive benefit from SNS. SNS strategists and managers could use the insight to improvise the use of SNS for strategic and operational benefits such as information, cost, productivity, and innovation. The analysis indicated that the corporate users formed a user group with predominantly utilitarian usage goals, with their attachment to public SNS trenched in work-related benefit perception. Companies should formulate clear SNS access and usage policies to channel and leverage employees’ online networking activities on public SNS gainfully, for knowledge integration, innovation, team building, and employee productivity.

Limitations and Future Research

SNS have become pervasive. SNS users can access the sites from their smartphones and wearable devices using the mobile network. This has blurred the device, network, location, and time boundaries of SNS access. This paper did not consider whether the user accessed the public SNS from a company-owned device, from the organizational network, or whether they accessed SNS from the workplace during work hours. The survey was conducted on all SNS users who were working professionals. It did not consider the organizational policy, and the work environment of the respondent. Further studies are needed to explore the impact of different organizational culture and SNS policies on respondents’ perception. We controlled the analysis for the number of connections on SNS and duration of SNS use, and several demographic variables. Further research is needed to test the model for a variety of industrial sectors, geographic locations, and ethnic groups.

This research contributes to the gap that exists in research on corporate users of SNS. The study reports some unique findings about the factors influencing corporate users’ attachment to SNS. In future, more research is required on the topic. There is a need to compare corporate users’ social capital formation in online and offline social networks and their relative influence on perceived benefit as well as the drift in the influence over time. The use of SNS has seen a sharp rise during the COVID-19 pandemic (Najmul Islam et al., 2022). Users’ familiarity with the technology as well as the advances in digital technologies are likely to affect users’ attitude towards SNS. The changes in relationships between the model constructs due to changes in corporate users’ attitude towards SNS and habits related to SNS need attention as well.

Conclusion

This research assessed the perceived work-related benefit from SNS for corporate users – a phenomenon that has lacked research attention in the past. The study derived a set of theoretically grounded constructs and hypotheses, and empirically tested the relationships between them. It made several unique contributions to SNS research. These included the study of the antecedents for the formation of social capital on SNS, determination of the mediating role of social capital in the association between SNS use and perceived strategic and operational benefit from SNS, the conceptualization of SNS attachment construct, and the determinants of corporate users’ SNS attachment. The analysis showed that corporate users perceived positive contribution from SNS use in generating operational and strategic benefit. The social use of SNS showed a stronger influence on social capital formation on SNS than informational use. The bridging social capital formed on SNS played a pivotal role in generating perceived benefit. The analysis showed that social capital and perceived benefit positively influenced SNS attachment for corporate users. The academic researchers would find SNS constructs, the overarching effect of social use, and the pivotal role of bridging social capital for corporate users interesting for further exploration in future. The results indicated that the corporate users largely attributed their SNS attachment to work-related benefit perception. The practitioners would find the findings and discussions of this paper useful in defining corporate SNS strategy to better leverage employees’ online networking activities on public SNS.

Biographies

Suparna Dhar

is a Professor of Computing & Analytics at the NSHM Knowledge Campus Kolkata. She has completed her Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and Masters of Statistics from Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata. Her research interests are in machine learning and AI, social networking, blockchainfintech, and cybersecurity. Her research has been published in journals like Decision Support Systems, and Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce as well as those of conferences like ICIS and Workshop on e-Business (pre-ICIS).

Indranil Bose

is Distinguished Professor of Management Information Systems at the NEOMA Business School. He acts as Head of the Area of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, and Business. He holds a BTech from the Indian Institute of Technology, MS from the University of Iowa, and MS and PhD from Purdue University. His research interests are in business analytics, digital transformation, information security, and management of emerging technologies. His publications have appeared in MIS Quarterly, Journal of the MIS, Communications of the ACM, Communications of the AIS, Computers and Operations Research, Decision Support Systems, Electronic Markets, European Journal of Operational Research, Information & Management, International Journal of Production Economics, Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Operations Research Letters, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, etc. He serves as Senior Editor of Decision Support Systems and Pacific Asia Journal of the AIS, and as Associate Editor of Communications of the AIS, Information & Management, and Journal of the AIS.

Appendix A: Literature Review

Table 7

Table 7.

A summary of the related literature

| Study | The premise of the study | |

|---|---|---|

| SNS use | (James et al., 2017) | Studied the use of SNS for social support and companionship |

| (Chen et al., 2014) | Studied the influence of commitment on SNS behavior | |

| (Ihm, 2015) | Studied the influence of communication and community formation on SNS engagement | |

| (Wu, 2013) | Studied the effect of employee’s network position on work outcomes | |

| Social capital | (Lee, 2013) | High levels of Facebook use were associated with high levels of bridging social capital |

| (Hofer & Aubert, 2013) | Investigated the influence of Twitter use on social capital | |

| (Ellison et al., 2007) | Investigated the influence of Facebook use on social capital | |

| (Steinfield et al., 2009) | Investigated the association between social capital and the use of organizational SNS | |

| (Huang et al., 2019) | Examined the association between social capital, and informational and emotional support | |

| (Cummings & Dennis, 2018) | Examined the influence of information sharing on enterprise SNS on impression formation and perception of social capital | |

| (Chen et al., 2016) | Studied the influence of relational social capital on continued use of SNS | |

| (Ellison et al., 2014) | Studied the relationship between Facebook behavior and bridging social capital | |

| (Jin, 2013) | Investigated the role of the technology readiness and acceptance model in building social capital | |

| (Horng & Wu, 2020) | Explored SNS behavior and social capital antecedents to social commerce intention | |

| (Zhao et al., 2012) | Examined the role of social capital and users’ sense of belonging towards sharing of experiences and knowledge on SNS | |

| (Cao, et al., 2015) | Investigated the role of SNS in supporting knowledge integration from a social capital perspective | |

| (Ali-hassan et al., 2015) | Investigated the effect of social media use on job performance mediated by social capital | |

| Perceived benefit | (Lam et al., 2016) | Studied the impact of the firm’s SNS initiatives on operational efficiency and innovation |

| (Moser & Deichmann, 2020) | Examined the effect of social capital and cultural factors on knowledge sharing on SNS | |

| (Pan et al., 2015) | Studied the dyadic knowledge exchanges in virtual communities of practice | |

| (French et al., 2017) | Examined the effect of perceived value from SNS in influencing continued use of SNS | |

| (Chen & Wei, 2020) | Studied the impact of SNS use for communication and social exchange relationships on employee performance | |

| (Schniederjans et al., 2013) | Studied the effect of a firm’s SNS activities on impression and financial performance | |

| (Li et al., 2020) | Studied the effect of perceived benefit from SNS on adoption intention | |

| SNS attachment | (Lee, 2013) | Studied the impact of anxiety and avoidance tenets of attachment on social capital formation on SNS |

| (Wan et al., 2017) | Examined how users’ donation intention is determined by the emotional attachment to the content creator and social factors and information factors | |

| (VanMeter et al., 2015) | Studied the effect of attachment to social media on the social media activities of consumers | |

| (Chung et al., 2016) | Studied SNS interactions for different types of bond-based and identity-based SNS attachment | |

| (Chen et al., 2019) | Studied the influence of anxiety and avoidance tenets of attachment on self-disclosure behavior on SNS | |

| (Kim et al., 2016) | Studied the effect of social capital of SNS attachment and loyalty |

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suparna Dhar, Email: suparnadhar@gmail.com.

Indranil Bose, Email: indranil_bose@yahoo.com.

References

- Adler PS, Kwon SW. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review. 2002;27(1):17–40. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2002.5922314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali-hassan H, Nevo D, Wade M. Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. Journal of Strategic Information Systems. 2015;24(2):65–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsis.2015.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JS, Overton TS. Nonresponse bias in mail accounting surveys. Journal of Marketing Research. 1977;14:396–402. doi: 10.1016/0890-8389(88)90036-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aswani R, Kar AK, Vigneswara Ilavarasan P. Detection of spammers in Twitter marketing: A hybrid approach using social media analytics and bio inspired computing. Information Systems Frontiers. 2018;20(3):515–530. doi: 10.1007/s10796-017-9805-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzi, L. (2018). Employees who use social media for work are more engaged — but also more likely to leave their jobs. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/05/employees-who-use-social-media-for-work-are-more-engaged-but-also-more-likely-to-leave-their-jobs. Accessed 24 Sep 2021

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52(4):664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28(5):759–775. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS. The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2000;22:345–423. doi: 10.1016/s0191-3085(00)22009-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Guo X, Liu H, Gu J. The role of social media in supporting knowledge integration: A social capital analysis. Information Systems Frontiers. 2015;17(2):351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10796-013-9473-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Basoglu KA, Sheng H, Lowry PB. A systematic review of social networks research in information systems: Building a foundation for exciting future research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2015;36:727–758. doi: 10.17705/1cais.03637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H, Ko E. Customer social participation in the social networking services and its impact upon the customer equity of global fashion brands. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(9):3804–3812. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wei S. The impact of social media use for communication and social exchange relationship on employee performance. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2020;24(6):1289–1314. doi: 10.1108/JKM-04-2019-0167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Lu Y, Chau PYK, Gupta S. Classifying, measuring, and predicting users’ overall active behavior on social networking sites. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2014;31(3):213–253. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2014.995557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Sharma SK, Rao HR. Members’ site use continuance on Facebook: Examining the role of relational capital. Decision Support Systems. 2016;90:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Hu N, Shu C, Chen X. Adult attachment and self-disclosure on social networking site: A content analysis of Sina Weibo. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;138(September 2019):96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang MY, Chen CJ, Lin MJ. The impact of social capital on competitive advantage: The mediating effects of collective learning and absorptive capacity. Management Decision. 2016;54(6):1443–1463. doi: 10.1108/MD-11-2015-0485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung N, Nam K, Koo C. Examining information sharing in social networking communities: Applying theories of social capital and attachment. Telematics and Informatics. 2016;33(1):77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2015.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Constant D, Sproull L, Kiesler S. The kindness of strangers: The usefulness of electronic weak ties for technical advice. Organization Science. 1996;7(2):119–135. doi: 10.1287/orsc.7.2.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culnan, M. J., McHugh, P. J., & Zubillaga, J. I. (2010). How large U.S. companies can use Twitter and other social media to gain business value. MIS Quarterly Executive, 9(4), 243–259. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol9/iss4/6. Accessed 18 Oct 2019

- Cummings J, Dennis AR. Virtual first impressions matter: The effect of enterprise social networking sites on impression formation in virtual teams. MIS Quarterly. 2018;42(3):697–718. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2018/13202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, K. (2007). Social capital, neighbourhood attachment and participation in distressed urban areas. A case study in The Hague and Utrecht, the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 22(3), 355–379. 10.1080/02673030701254103

- Durst C, Viol J, Wickramasinghe N. Online social networks, social capital and health-related behaviors: A state-of-the-art analysis. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2013;32(1):134–158. doi: 10.17705/1cais.03205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]