Abstract

Objectives

We estimate the causal impact of intensive caregiving, defined as providing at least 80 h of care per month, and work on the mental health of caregivers while considering possible sources of endogeneity in these relationships.

Methods

We use 2 linked data sources from the United States by matching caregivers in the National Study of Caregiving with corresponding care recipients in the National Health and Aging Trends Study for years 2011–2017. We address possible sources of endogeneity in the relationships between caregiving, work, and mental health by using instrumental variables methodology, instrumenting for both caregiving and work behavior. We examine 2 measures used to screen for depression (PHQ-2, psychodiagnostic test) and anxiety (GAD-2, generalized anxiety disorders screening instrument), a composite measure that combines these measures (PHQ-4), and positive well-being variables to ascertain possible gains from caregiving.

Results

Providing at least 80 h of care per month to a parent compared to less intensive caregiving increases the PHQ-4 scale for anxiety and depression disorders. This is driven by the screening score for anxiety and not psychodiagnostic test scores for depression. Relationship quality decreases substantially for intensive caregivers, and intensive caregiving leads to less satisfaction that the care recipient is well-cared for. We do not find offsetting mental health gains for intensive caregivers compared to nonintensive caregivers. Work does not independently affect the mental health of caregivers.

Discussion

Caregiver interventions that reduce objective demands or support intensive caregivers could reduce or prevent well-being losses and improve the caregiver’s relationship with the recipient.

Keywords: Caregiving, Instrumental variables, Intergenerational relations, Mental health, Work-related issues

Over 26 million family and other unpaid caregivers in the United States actively care for an adult with physical limitations (Freedman & Wolff, 2020), and this number is growing. Half of these caregivers are providing care to their parents or parent-in-law. The demographic characteristics of these caregivers, however, remain largely unchanged; 61% are women, with a median age of 51 years, and 61% are employed.

While providing care to a parent can be a rewarding task, it can be psychologically and physically demanding; potentially even more so if a caregiver is working and providing care at the same time. It has been well documented that caregivers have worse health than noncaregivers on a variety of measures. This correlation has been getting stronger in recent years. Caregivers today rate their health worse than caregivers in 2015, while self-rated health among noncaregivers has remained unchanged (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020). This correlation could be due to selection—those with worse health characteristics become caregivers—or due to caregiving itself. Almost one quarter of caregivers perceive the caregiving itself being detrimental to their health (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020). Research has largely supported this perception, finding that caregiving contributes to lower mental health (Bauer & Sousa-Poza, 2015; Bom et al., 2019; Brenna & Di Novi, 2016; Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; de Zwart et al., 2017; Heger, 2017; Lavela & Ather, 2010; Pruchno & Resch, 1989; Schmitz & Westphal, 2015; van den Berg et al., 2014). Several studies have found a larger mental health detriment due to caregiving among women (Bauer & Sousa-Poza, 2015; Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Heger, 2017) and among those caring for a spouse (Bom et al., 2019; Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Heger, 2017; Penning & Wu, 2015).

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016) mention “caregiving rewards or benefits, appreciation of life, personal growth, enhanced self-efficacy, competence or mastery, self-esteem, and closer relationships” as the most common positive psychological effects of caregiving used in the literature. However, although rewards are of growing interest (Brown & Brown, 2014; Quinn & Toms, 2018; Roth et al., 2015), there is much less quantitative literature on the gains or rewards to caregiver mental health from caregiving (Kramer, 1997; López et al., 2005), which should be considered for well-designed policy action when targeting caregivers of older adults. The literature consists mainly of exploratory and cross-sectional studies and suggests positive experiences from care recipients’ progress, strengthened relationships, appreciation, and self-esteem (Mackenzie & Greenwood, 2012). Correlational evidence suggests that, especially male spousal and adult children caregivers experience more rewards from caregiving, in the sense that caregiving made them feel good about themselves and helped them to appreciate life more (Lin et al., 2012; Raschick & Ingersoll-Dayton, 2004). Freedman et al. (2014) find that for women, spousal care is associated with increased happiness while completing the care activity.

Most research to date does not examine how the intensity of caregiving is related to mental health, largely due to data limitations. Among the studies that have been able to examine this relationship, Doebler et al. (2017) and Bom and Stöckel (2021) found a strong relationship between intensive caregiving, measured as providing more than 19 h a week, and mental ill-health. Cannuscio et al. (2004) also found that more time spent weekly on caregiving for a spouse or parent was associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms for women, irrespective of employment status. While the mental and physical health effects of caregiving could be more pronounced among caregivers providing more hours of care, a potential reverse effect is also possible. Individuals struggling with their mental health may scale down their caregiving intensity, and unobserved factors (e.g., resiliency) could influence both caregiving intensity and mental health.

It is well documented that caregivers work less than noncaregivers, but this too could be due to selection, age (spousal caregivers are more likely to have reached typical retirement age), or the caregiving responsibilities themselves. The literature has yet to establish a clear pattern on the causal relationship of care intensity and the role of work behavior in mental health outcomes. While some have found that working a few hours in combination with providing care is positively associated with mental health (Eberl et al., 2017), others found that individuals experience double duties of informal care provision and working and are more likely to use antidepressant drugs and tranquilizers (Schmitz & Stroka, 2013). While ongoing work has not found effects of caregiving on work productivity (Coe et al., 2021), consistent work performance along with caregiving duties could come at the expense of the caregivers’ own mental health.

In this study, we estimate the causal impact of intensive caregiving on mental health of caregivers while also considering the work status of the caregiver. The caregiving and work choices may be very interconnected for adult children. Although a healthier child is more likely to assume the caregiver role because they may be more resilient, it is also possible that a less healthy or less productive family member may assume the role instead of participating in work or while reducing work (Do et al., 2015). We address possible sources of endogeneity in these relationships by using instrumental variables methodology, instrumenting for both intensive caregiving and work behavior. Addressing endogeneity is important because nonrandom selection into work and caregiving would bias the estimates of how intensive caregiving affects mental health. We rely on theoretically strong and defensible instrumental variables from the literature for work and caregiving.

Conceptual Model

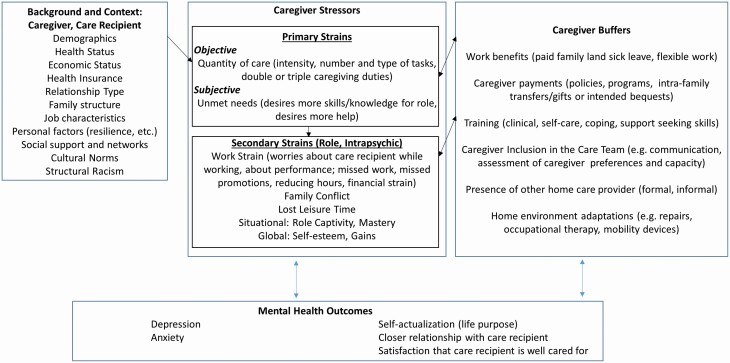

To explore the question of how intensive caregiving (at least 80 h per month), compared to providing less care to a parent, affects mental health, we adapt the Pearlin Model of caregiving (Pearlin et al., 1990), which has been widely used to answer care-related questions on caregiver stress and strain. The Pearlin Model builds on theories on stress and coping factors that increase caregiver stress and analyzes primary and secondary mechanisms by which stress affects health outcomes (Robison et al., 2020). Whereas the original model considers physical and mental health outcomes, in this article, we focus primarily on mental health outcomes. We extend the model to incorporate considerations from the caregiving labor economics literature and caregiver support policy literature—for example, caregiver supports are a form of caregiver buffers (Bolin et al., 2008; Coe et al., 2021; Jacobs et al., 2014, 2017; Kolodziej et al., 2018; Leigh, 2010; Skira, 2015; Van Houtven et al., 2013). The two-headed arrows (Figure 1) illustrate the endogeneity threats described above that need to be accounted for in the empirical approach to allow for estimation of causal effects of intensive caregiving on outcomes.

Figure 1.

Caregiver stress process model and mental health outcomes. Note: Model adapted from the Robison et al. (2020) version of the Pearlin Stress Process Coping Model and extended using Coe et al. (2021), Van Houtven et al. (2011, 2020), Shepherd-Banigan et al. (2020), Szanton et al. (2011), and NASEM (2016).

The model components stem from four domains: (a) the background and context of stress can be caregiver or care recipient factors, such as demographics, health status, health insurance and other economic factors, the relationship type, and cultural norms surrounding caregiving (Coe et al., 2021; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Robison et al., 2020; Shepherd-Banigan et al., 2020; Szanton et al., 2011; Van Houtven, Lippmann et al., 2020; Van Houtven et al., 2011). Relationship type could indicate shared households, and thereby how closely linked caregiver and care recipient health insurance and economic status may be. Family structure can also be an important background factor that determines who becomes a caregiver and the intensity of their caregiving role. Additionally, one’s job characteristics may affect how caregivers can juggle work and caregiving, such as through flexibility (Coe et al., 2021) or by job requirements. Finally, structural racism may affect mental health differently for Black and brown caregivers because experiences of racism negatively affect stress (Williams et al., 2019). The next component of the model (b) is stress proliferation, affected by primary stressors. Objective primary stressors include the intensity of caregiving provided, which can be measured as hours or number of tasks or types of tasks. Intensity also could be measured as number of care recipients a single caregiver helps, for example, double or triple-caregiving duties (Van Houtven, DePasquale et al., 2020). Subjective primary stressors broadly include role strain and role captivity. These could be measured as the extent of unmet needs, such as caregivers desiring more training, caregivers desiring more assistance from others, or more skills in clinical care or self-care tasks. In addition to primary stressors, (c) secondary strains (role and intrapsychic) and mediators of stress are the third set of factors in stress proliferation, and these are factors not directly related to the caregiving role, such as dynamic work factors (reducing hours, reducing pay, worrying about caregiving while at work) or the stress that arises from constricted leisure time. Additionally, (d) caregiver buffers can ameliorate and reduce stress proliferation, increase gains, reduce depressive symptoms, and increase access to mental health care (Smith et al., 2019; Van Houtven et al., 2019). Whereas the model explicitly includes tangible caregiver supports and services, such as direct stipend programs and tax credits that have been found to significantly affect caregiver outcomes broadly, not all of these programs have been shown explicitly to improve caregiver mental health and well-being outcomes (Smith et al., 2019). Other listed buffers are hypothesized to ameliorate caregiver stress and strain but have not yet been tested directly for caregiver mental health effects (Sperber et al., 2019; Szanton et al., 2011; Van Houtven, Lippmann et al., 2020).

The outcomes in the model show how proliferation of stress manifests itself in affecting mental health outcomes, considering ameliorating impacts of caregiver buffers and supports. An important addition to the Robison et al. (2020) version of the model is the explicit recognition of positive gains from caregiving, such as self-actualization, relationship quality, and satisfaction from caregiving.

Data and Outcomes

We use two cohesive data sources from the United States for our analysis by matching caregivers that provide information in the National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) with their corresponding care recipients (parents) from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS; also see Kasper & Freedman, 2018 and Freedman et al., 2019). These data provide extensive information on both caregiver and care recipient. We use three waves of NSOC (2011, 2015, and 2017) and information from the corresponding NHATS (Waves 1, 5, and 7), limiting the sample to adult children providing care to their parents. Limiting the sample to adult children reduces the number of observations by 1,884. Five hundred and thirty-four observations are dropped due to missing data on independent or dependent variables. Our final sample includes 3,039 caregiver observations of which 970 are providing intensive care.

Mental Health Outcomes

We consider several measures of mental health from NSOC that describe caregiver depressive symptoms, caregiver anxiety, and measures of positive rewards from caregiving.

PHQ-4

Anxiety and depression often co-occur and should be assessed together. For this, Kroenke et al. (2009) introduce a four-item composite measure for depression and anxiety (PHQ-4) that combines screening instruments for generalized anxiety disorders (GAD-2) and major depression (PHQ-2) and runs from 0 to 12. While anxiety has an independent effect on functioning, the effect is more pronounced when it occurs together with depression, which is why it is advised to screen for both (Kroenke et al., 2009).

GAD-2

The GAD-2 is a screening instrument for the detection of generalized anxiety disorders. We use the scale that runs from 0 to 6 and its cutoff value of 3 as an indicator for pathological anxiety levels. The two-item screener for anxiety is seen to be able to enhance detection of anxiety disorders for the four most common anxiety disorders that are generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Kroenke et al., 2007). GAD-2 consists of the first two items of the GAD-7, which represent core anxiety symptoms that the respondent felt over the last month: (a) feeling nervous, anxious, or on the edge and (b) not being able to stop or control worrying. The response options for each question are “not at all” which is scored as 0, “several days” scored as 1, “more than half the days” scored as 2, and “nearly every day” scored as 3. The scores to both questions are summed up giving the GAD-2 a score between 0 and 6. A cut-point of 3 or greater is used to detect anxiety disorder (Kroenke et al., 2007).

PHQ-2

Like the GAD-2, we use the PHQ-2 psychodiagnostic test scale that runs from 0 to 6 and is used to screen for a major depression. The questions ask the respondent how often he or she (a) had little interest or pleasure in doing things and (b) felt down, depressed, or hopeless over the last month. As for the GAD-2, the answers to the questions are scored between 0 (“not at all”) and 3 (“nearly every day”) and are summed up, leading to a scale that runs from 0 to 6. The cut-point of 3 or more points on the depression screener has high sensitivity to detect major depressive disorder (Kroenke, 2003; Kroenke et al., 2009).

Positive well-being

We consider caregiver self-actualization as two separate components: (a) life purpose and (b) growth. Caregivers are asked to value the statements (a) My life has meaning and purpose and (b) I gave up trying to improve my life a long time ago. We construct dummy variables that categorize the answers from (a) into “Agree strongly or somewhat (1) versus disagree somewhat or strongly (0)” and (b) “Disagree strongly or somewhat (1) versus agree somewhat or strongly (0)”. For each, a value of 1 indicates rewards (Polenick et al., 2017).

Positive direct experiences from helping the care recipient describe (a) the relationship and (b) satisfaction from helping. Respondents are asked to value the statement (a) Helping [the care recipient] has brought you closer to [him/her] and (b) Helping [the care recipient] gives you satisfaction that [he/she] is well cared for. The answers in both cases are recoded as a dummy variable that categorizes the answers into “very much or somewhat (1)” versus “not so much (0)”.

Treatment Variable of Primary Interest: Intensive Caregiving

The primary variable of interest is an indicator variable of whether a caregiver provided intensive care, defined as at least 20 h a week in the past month, or at least 80 h of care in the past month. A 20 h a week threshold has similarly been used in other literature, where nonintensive caregiving is less than 20 h a week over the past month (Jacobs et al., 2017, 2019). We also present descriptively the average hours of care in the past month, and the average hours in the past month caregivers provide personal care tasks, defined as eating, showering or bathing, dressing or grooming, or using the toilet.

Method

Instrumental Variables

We instrument for work behavior and intensive caregiving to address potential endogeneity bias in our main treatment variable of interest, intensive caregiving’s effect on caregiver mental health. First, for work behavior, we employ an instrumental variable that provides exogenous variation in job retention to rule out potentially confounding effects from mental health on work. Drawing from studies about retirement’s effects on cognition (Bonsang et al., 2012; Coe et al., 2012), we use the eligibility age for Social Security benefits, sometimes called the early retirement age (≥62). The earliest eligibility age for retirement benefits is highly predictive of retirement behavior, and these policy variables are plausibly independent of a caregiver’s individual health status.

Second, to account for nonrandom selection into caregiving, we use family structure as an instrumental variable, as has been done in the cross-sectional (Jacobs et al., 2017) and longitudinal literature (Van Houtven et al., 2013). Which aspects of family structure work best to predict intensive caregiving is an empirical question. Previous studies have used the total number of siblings a caregiver has, the number of daughters, and the gender combined with the birth order, such as having a daughter as the oldest child (Bolin et al., 2008; Ettner, 1995; Kolodziej et al., 2018; Van Houtven & Norton, 2004). Preliminary analysis suggested the number of adult children of the care recipient was the best IV for our application (e.g., highest F-statistic). To be valid, the number of adult children in a family must be independent of the mental health outcomes of the caregiver; however, number of children is allowed to affect mental health through its effect on caregiving. There is no evidence that family structure, for example, size, birth order, and gender mix, systematically affects the mental health of adult children (the prospective caregivers) directly. As such, it is plausible that family structure drives the decision to intensively provide care, and through that decision, caregiving affects mental health gains and losses. In addition, a valid instrument must causally and strongly affect treatment assignment, that is, intensive caregiving (Angrist & Krueger, 2001; Lousdal, 2018). The temporal nature of a parent’s fertility decisions, which precede by decades the need for care, and the fact that children are the ones making decisions about intensity of caregiving, means that it is plausible that the instrument causes the treatment decision, hours of caregiving provided. In addition, it is important that careful inference is made in an instrumental variables approach, to not overinterpret findings to the full sample (e.g., to limit to compliers). Specifically, an instrumental variables approach allows us to estimate the effect of intensive caregiving on mental health of caregivers among the subgroup of caregivers invoked to change caregiving intensity due to family structure. This limit to generalizability is worth increasing internal validity (e.g., minimizing bias on the estimated effect of interest, intensive caregiving).

The first-stage equations are as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

with

The vector X2 includes marital status, ethnicity (White, Black, Other, and Hispanic), age in years, age squared, gender, and indicators on care recipient level that include the number of self-care or mobility limitations (difficulties getting dressed, walking, bathing or showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, using the toilet, preparing a meal, shopping for groceries, using the telephone, taking medications, doing laundry, and managing money), whether a proxy answered the NHATS questions, widowhood, past and current chronic health conditions (heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, dementia, and cancer), whether the care recipient lives in an assisted living facility that entails independent living, assisted living, special care, memory care or Alzheimer’s unit, nursing home, and other facility, as well as indicators for NSOC rounds I, II, and III.

The instrument for caregiving intensity (number of adult children) should not affect work behavior, and the instrument for work behavior (early retirement age) should not affect caregiving intensity. We study this required absence of significance after adjusting for the corresponding instrument in the respective equation. Other potential instruments (widowhood, share of daughters, presence of a daughter) yielded weak instruments or problems with exclusion restriction violations. Based on F-statistic, magnitude, and significance in the first stage, we chose the number of adult children of the care recipient as our preferred instrument. We further test the sensitivity of the results for changes in age specification which might be a concern given our instrument for working and find that our results robust to these changes.

The main outcome equation then is estimated using

| (3) |

with

MH = Mental Health (PHQ-4, PHQ-2, GAD-2, Purpose, Growth, Closer, Satisfaction)

We use two-stage least squares for all of our modeling; hence, the interpretation of the estimated effects of care intensity on outcomes is a change in the score’s points for the continuous outcomes from switching from nonintensive to intensive caregiving (losses) and a change in percent for discrete outcomes from switching from nonintensive to intensive caregiving (gains). We pool the cross-sectional samples from Rounds I, II, and III and cluster standard errors at the caregiver level as the main specification, to control for the fact that caregiver behavior may be correlated over time. We also check the robustness of the results when we cluster on care recipient level to account for cases where one care recipient has multiple adult children caregivers (Supplementary Appendix Tables 1 and 2). The results are even stronger in this specification, but we think clustering on the caregiver level is most appropriate given we are examining caregiver mental health outcomes.

Results

Descriptive

On average, caregivers report having 1.09 symptoms of anxiety, and 13% report two or more symptoms. Similarly, caregivers report having 1.00 symptoms of depression using the PHQ-2 depression scale (Table 1). 13% report having two or more symptoms of depression. Caregivers’ assessment of positive well-being and rewards (gains) is generally high: 96% of caregivers agree that their life has meaning and purpose, while 86% do not agree with the statement that they gave up trying to improve their life a long time ago. About 91% of caregivers state that helping the care recipient has brought them closer to him or her and almost all (99%) state that helping the care recipient gives them satisfaction that he or she is well cared for.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adult Children Caregivers and Their Parent Care Recipients (caregiver-wave observations)

| Mean | Obs | |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver health | ||

| PHQ-4: Anxiety/depression composite measure (0–12) | 2.09 | 3,039 |

| GAD-2: Anxiety scale (0–6) | 1.09 | 3,039 |

| GAD-2: Indicator min. two symptoms of anxiety (0, 1 if screen positive) | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| PHQ-2: Depression scale (0–6) | 1.00 | 3,039 |

| PHQ-2: Indicator min. two symptoms of depression (0, 1 if screen positive) | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| Purpose (0, 1 if agrees with statement) | 0.96 | 3,039 |

| Growth (0, 1 if agrees with statement) | 0.86 | 3,039 |

| Closer (0, 1 if agrees with statement) | 0.91 | 3,039 |

| Satisfaction (0, 1 if agrees with statement) | 0.99 | 3,039 |

| Caregiving | ||

| Any type of care: Hours per month | 84.20 | 2,945 |

| Personal care: Hours per month | 38.69 | 2,303 |

| Intensive caregiving (min. 80 h a month) | 0.32 | 3,039 |

| Work | ||

| Work for pay in the last week or month | 0.55 | 3,039 |

| Hours per week usually worked among workers | 19.82 | 2,877 |

| Working full-time among workers | 0.72 | 1,607 |

| Working part-time among workers | 0.28 | 1,607 |

| Reported having flexible work hours among workers | 0.60 | 1,665 |

| White-collar worker | 0.38 | 3,039 |

| Service worker | 0.10 | 3,039 |

| Blue-collar worker | 0.07 | 3,039 |

| Caregiving and work | ||

| Intensive care, no work | 0.18 | 3,039 |

| No intensive care, work | 0.41 | 3,039 |

| Intensive care, work | 0.14 | 3,039 |

| No intensive care, no work | 0.27 | 3,039 |

| Relationship | ||

| Daughter | 0.70 | 3,039 |

| Son | 0.30 | 3,039 |

| Demographics | ||

| Married | 0.53 | 3,039 |

| Race | ||

| White | 0.60 | 3,039 |

| Black | 0.29 | 3,039 |

| Other | 0.04 | 3,039 |

| Hispanic | 0.06 | 3,039 |

| Reached early retirement age | 0.31 | 3,039 |

| Age in years | ||

| 30–39 | 0.03 | 3,039 |

| 40–49 | 0.16 | 3,039 |

| 50–59 | 0.40 | 3,039 |

| 60–69 | 0.34 | 3,039 |

| 70–79 | 0.06 | 3,039 |

| Male | 0.30 | 3,039 |

| Education | ||

| 9th to 12th grade or less | 0.07 | 3,039 |

| High school graduate | 0.24 | 3,039 |

| Associate’s degree or less (beyond high school) | 0.35 | 3,039 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.20 | 3,039 |

| Master’s, professional, or doctorate | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| Education missing indicator | 0.01 | 3,039 |

| Household income last year (thousands) | 62.96 | 2,231 |

| NHATS respondent information (older parent) | ||

| Married | 0.22 | 3,039 |

| Male | 0.21 | 3,039 |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 | 0.12 | 3,039 |

| 75–79 | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| 80–84 | 0.22 | 3,039 |

| 85–89 | 0.24 | 3,039 |

| 90 and older | 0.28 | 3,039 |

| Number of self-care or mobility limitations | 5.39 | 3,039 |

| Chronic conditions (ever had) | ||

| Heart attack | 0.11 | 3,039 |

| Heart disease | 0.32 | 3,039 |

| High blood pressure | 0.80 | 3,039 |

| Arthritis | 0.77 | 3,039 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.36 | 3,039 |

| Diabetes | 0.35 | 3,039 |

| Lung disease | 0.25 | 3,039 |

| Stroke | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| Dementia | 0.25 | 3,039 |

| Cancer | 0.15 | 3,039 |

| Lives in an assisted living facility | 0.13 | 3,039 |

| NSOC Round I | 0.31 | 3,039 |

| NSOC Round II | 0.33 | 3,039 |

| NSOC Round III | 0.36 | 3,039 |

Notes: NHATS = National Health and Aging Trends Study; NSOC = National Study of Caregiving. Characteristics are shown for our main sample that only includes individuals with no missing values on the outcomes or any of the covariates. Number of observations for characteristics that are not included in the estimations can be lower than in the final sample. Descriptive statistics for NSOC participants: caregivers of NHATS participants. Individuals with missing information on type of occupation but who state to be working are included in the regressions in the base category together with white-collar workers. Chronic conditions include past and current chronic conditions; the question asks whether a doctor ever told the NHATS participant that he/she had a condition. Residential care setting entails independent living, assisted living, special care, memory care or Alzheimer’s unit, nursing home, and other facility.

NSOC caregivers provide an average of 84 h of care per month, of which 39 h is personal care on average. More than half (55%) of the caregivers work for pay. Among workers, more than two thirds work full-time, and slightly less than one third work part-time. Almost two thirds of working caregivers report having flexible work hours and almost half are white-collar or service workers. While 18% provide intensive care and do not work, almost as many (14%) do both. 41% work but do not provide intensive care and 27% do not work nor provide intensive care. While most caregivers are older than 50 years, almost one fifth are between 30 and 49 years. The largest age group is 50–59 (40%), 34% are between 60 and 69 years, and only 6% of caregivers are between 70 and 79 years. Almost one third of caregivers had reached the early retirement age (age 62).

About half of the caregivers are married, 70% are female and 60% are White. Nearly one third are Black (29%), 6% are Hispanic, and 4% are of other ethnicities. 35% of caregivers have an associate’s degree or less and one third have a bachelor’s degree or other higher education. The average annual household income of the caregiver is $63,000. Most caregivers provide care to a female, unmarried older adult who needs assistance with 5.4 self-care or mobility limitations on average. The care recipients are among the oldest old, with three quarters 80 years or older. One third of caregivers are caring for a parent who has a heart disease, 80% have high blood pressure, and almost as many (77%) have arthritis. 13% of the parents live in a residential care setting.

First Stage

The first-stage results show that our instruments are working as hypothesized (Table 2). If the parent has one (more) adult child, it decreases the probability of intensive caregiving for the caregiver by 1.2 percentage points. If the caregiver has reached the early retirement age (the instrument for employment), it does not affect caregiving intensity. On the other hand, having reached the early retirement age affects working behavior: if the caregiver is 62 or older, this decreases the probability of working by about 14.1 percentage points. The number of adult children of the care recipient does not affect employment. The instruments are strongly correlated with intensive caregiving and work, as indicated by the F-statistics. We use the Sanderson–Windmeijer F-Statistic of weak identification of individual endogenous regressors (Sanderson & Windmeijer, 2016). Number of children has an F-statistic of 10.7 and early retirement age has an F-statistic of 20, therefore both exceed the magnitude threshold of 10 (Table 2).

Table 2.

First-Stage Results

| (1) Intensive caregiving (min. 80 h a month) | (2) Work for pay in the last week or month | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of children (SP) | −0.012 (0.004)** | 0.003 (0.004) |

| Reached early retirement age (≥62 years) | −0.018 (0.029) | −0.141 (0.032)*** |

| Widowed (SP) | 0.092 (0.018)*** | −0.081 (0.021)*** |

| Married | −0.131 (0.018)*** | 0.057 (0.020)** |

| Black | 0.154 (0.023)*** | −0.051 (0.025)* |

| Other | 0.079 (0.047) | −0.024 (0.052) |

| Hispanic | 0.190 (0.038)*** | −0.053 (0.037) |

| Age in years | −0.015 (0.008) | 0.016 (0.008)* |

| Age in years squared/100 | 0.012 (0.008) | −0.024 (0.007)** |

| Male | −0.098 (0.018)*** | 0.032 (0.020) |

| Number of self-care or mobility limitations (SP) | 0.028 (0.003)*** | −0.001 (0.003) |

| Proxy answ. NHATS questions (SP) | 0.034 (0.031) | −0.014 (0.032) |

| Heart attack (SP) | 0.021 (0.028) | −0.014 (0.029) |

| Heart disease (SP) | −0.011 (0.019) | −0.003 (0.021) |

| High blood pressure (SP) | −0.001 (0.022) | −0.025 (0.024) |

| Arthritis (SP) | −0.012 (0.020) | 0.004 (0.023) |

| Osteoporosis (SP) | −0.005 (0.018) | −0.021 (0.020) |

| Diabetes (SP) | −0.003 (0.019) | −0.006 (0.021) |

| Lung disease (SP) | 0.046 (0.021)* | −0.055 (0.023)* |

| Stroke (SP) | 0.032 (0.026) | −0.058 (0.026)* |

| Dementia (SP) | 0.035 (0.026) | −0.023 (0.027) |

| Cancer (SP) | 0.023 (0.023) | 0.021 (0.026) |

| Lives in an assisted living facility (SP) | −0.198 (0.019)*** | 0.058 (0.029)* |

| NSOC Round II | −0.014 (0.020) | −0.011 (0.021) |

| NSOC Round III | −0.006 (0.021) | 0.006 (0.022) |

| Constant | 0.651 (0.220)** | 0.578 (0.210)** |

| F-Statistic | 10.70 | 20.06 |

| Number of observations | 3,039 | 3,039 |

Notes: NHATS = National Health and Aging Trends Study; NSOC = National Study of Caregiving. SP represents NHATS survey person and denotes care recipient information. All other variables are on caregiver level. Standard errors in parentheses. Cluster robust standard errors on caregiver individual level (number of clusters: 2,440). We estimate regressions for individuals who provide information on all outcomes to better compare results. F-Statistic is the Sanderson–Windmeijer first-stage F statistic of weak identification of individual endogenous regressors (Sanderson & Windmeijer, 2016).

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Main Outcomes

Intensive caregiving increases the PHQ-4 score by 4.6 points (Table 3, column 1). The subscales show that this result is driven by anxiety. Providing intensive care to a dependent parent increases the GAD-2 screening score by 3.2 (Table 3, column 2). On the other hand, we do not find a significant increase in psychodiagnostic test scores (PHQ-2) among intensive caregivers (Table 3, column 3). In sensitivity analysis, we find that the effects do not change probability of major depression but increase probability of anxiety diagnosis (mean value of 0.128) by 56 percentage points (i.e., having two or more symptoms of depression or anxiety, respectively). Employment has no effect on mental health of caregivers across all specifications.

Table 3.

Main Results

| (1) PHQ-4 | (2) GAD-2 | (3) PHQ-2 | (4) Purpose | (5) Growth | (6) Closer | (7) Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive caregiving | 4.632 (2.201)* | 3.211 (1.346)* | 1.420 (1.051) | −0.037 (0.138) | 0.355 (0.263) | −0.528 (0.253)* | −0.164 (0.082)* |

| Work for pay | 0.866 (1.355) | 0.275 (0.857) | 0.591 (0.642) | 0.187 (0.098) | 0.039 (0.171) | −0.040 (0.182) | −0.062 (0.066) |

| Widowed (SP) | −0.141 (0.258) | −0.194 (0.161) | 0.053 (0.123) | −0.003 (0.016) | −0.020 (0.031) | 0.028 (0.030) | 0.010 (0.010) |

| Married | −0.103 (0.323) | 0.175 (0.198) | −0.278 (0.155) | 0.008 (0.020) | 0.097 (0.040)* | −0.081 (0.037)* | −0.019 (0.011) |

| Black | −1.005 (0.356)** | −0.785 (0.222)*** | −0.219 (0.169) | 0.019 (0.024) | −0.021 (0.042) | 0.132 (0.043)** | 0.036 (0.013)** |

| Other | −0.597 (0.376) | −0.380 (0.228) | −0.217 (0.177) | 0.006 (0.025) | −0.051 (0.047) | 0.057 (0.040) | 0.012 (0.017) |

| Hispanic | −1.083 (0.468)* | −0.725 (0.296)* | −0.358 (0.219) | −0.022 (0.035) | −0.107 (0.058) | 0.135 (0.054)* | 0.039 (0.017)* |

| Age in years | 0.098 (0.077) | 0.058 (0.047) | 0.040 (0.038) | −0.010 (0.004)* | −0.002 (0.009) | 0.001 (0.010) | −0.001 (0.003) |

| Age in years squared/100 | −0.089 (0.082) | −0.056 (0.050) | −0.032 (0.040) | 0.012 (0.005)* | 0.003 (0.010) | −0.002 (0.011) | −9E−5 (0.003) |

| Male | 0.043 (0.243) | −0.009 (0.151) | 0.052 (0.116) | −0.012 (0.016) | 0.034 (0.029) | −0.064 (0.030)* | −0.025 (0.011)* |

| Number of self-care or mobility limitations (SP) | −0.051 (0.062) | −0.054 (0.039) | 0.003 (0.029) | 0.3E−4 (0.004) | −0.015 (0.008) | 0.015 (0.007)* | 0.005 (0.002)* |

| Proxy answ. NHATS questions (SP) | −0.451 (0.233) | −0.256 (0.147) | −0.195 (0.110) | −0.007 (0.016) | 0.031 (0.029) | 0.031 (0.029) | 0.013 (0.010) |

| Heart attack (SP) | −0.096 (0.194) | −0.061 (0.124) | −0.035 (0.091) | 0.022 (0.011)* | −0.061 (0.027)* | 0.046 (0.022)* | 0.008 (0.006) |

| Heart disease (SP) | 0.308 (0.131)* | 0.173 (0.083)* | 0.134 (0.063)* | 0.011 (0.008) | 0.023 (0.017) | −0.024 (0.017) | 0.003 (0.005) |

| High blood pressure (SP) | 0.055 (0.152) | 0.044 (0.095) | 0.011 (0.072) | −0.3E−4 (0.010) | −0.010 (0.019) | 0.002 (0.020) | −0.008 (0.006) |

| Arthritis (SP) | 0.096 (0.140) | 0.024 (0.085) | 0.073 (0.070) | 0.1E−4 (0.009) | −0.005 (0.018) | −0.008 (0.018) | −0.015 (0.006)** |

| Osteoporosis (SP) | −0.117 (0.123) | −0.003 (0.078) | −0.113 (0.060) | −0.2E−4 (0.009) | 0.020 (0.016) | 0.011 (0.016) | 0.005 (0.006) |

| Diabetes (SP) | 0.076 (0.132) | 0.011 (0.082) | 0.066 (0.064) | −0.2E−4 (0.009) | 0.005 (0.016) | −0.011 (0.016) | −0.007 (0.006) |

| Lung disease (SP) | −0.018 (0.188) | −0.055 (0.118) | 0.037 (0.088) | 0.013 (0.012) | −0.053 (0.023)* | 0.026 (0.022) | 0.013 (0.008) |

| Stroke (SP) | 0.127 (0.204) | 0.074 (0.129) | 0.053 (0.097) | −0.014 (0.014) | −0.011 (0.027) | 0.006 (0.026) | 0.009 (0.007) |

| Dementia (SP) | 0.111 (0.197) | 0.033 (0.124) | 0.078 (0.094) | 0.017 (0.012) | −0.044 (0.026) | −0.011 (0.025) | 0.002 (0.010) |

| Cancer (SP) | 0.052 (0.172) | −0.002 (0.106) | 0.054 (0.085) | −0.012 (0.011) | −0.012 (0.022) | −0.004 (0.022) | −0.4E−4 (0.008) |

| Lives in an assisted living facility (SP) | 0.698 (0.473) | 0.542 (0.291) | 0.156 (0.225) | −0.006 (0.028) | 0.116 (0.056)* | −0.113 (0.054)* | −0.024 (0.018) |

| NSOC Round II | −0.127 (0.139) | −0.048 (0.089) | −0.079 (0.067) | 0.004 (0.009) | 0.008 (0.019) | 0.002 (0.017) | −0.007 (0.006) |

| NSOC Round III | −0.051 (0.144) | 0.044 (0.091) | −0.094 (0.070) | −0.009 (0.010) | 0.012 (0.019) | 0.010 (0.018) | −0.012 (0.006) |

| Constant | −1.901 (2.095) | −1.091 (1.277) | −0.810 (1.024) | 1.045 (0.120)*** | 0.805 (0.250)** | 1.050 (0.230)*** | 1.131 (0.086)*** |

| Outcome is binary | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 3,039 | 3,039 | 3,039 | 3,039 | 3,039 | 3,039 | 3,039 |

Notes: NHATS = National Health and Aging Trends Study; NSOC = National Study of Caregiving. SP represents NHATS survey person and denotes care recipient information. All other variables are on caregiver level. Standard errors in parentheses. Cluster robust standard errors on caregiver individual level (number of clusters: 2,456). We estimate regressions for individuals who provide information on all outcomes to better compare results. Intensive caregiving denotes helping a minimum of 80 h a month. Work for pay denotes working in the last week or month. We show unadjusted associations and results from OLS estimation in Supplementary Appendix Tables A3–A4.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Other covariates that affect mental health include marital status, race, and health conditions. Black and Hispanic caregivers have a significantly lower PHQ-4 score compared to Whites and non-Hispanics, which is driven by the GAD-2 score. Heart disease of the care recipient is positively associated with the GAD-2 score and the PHQ-2 score.

For positive well-being, we do not find significant effects on self-actualization (Table 3, columns 4 and 5), but we find significant negative effects of intensive caregiving on indicators that are directly related to caregiving. Providing intensive parent care significantly decreases the probability of stating that helping the care recipient has brought them closer (Table 3, column 6), by 52.8 percentage points, and decreases the probability to be satisfied that the care recipient is well-cared for by 16.4 percentage points (Table 3, column 7). In robustness checks, we redefined the categorization of the rewards variables in a more stringent way, where answers for life purpose are split into the categories “agree strongly” (1) versus “agree somewhat or disagree somewhat or strongly” (0), for growth the redefined categories are “disagree strongly” (1) versus “disagree somewhat or agree somewhat or strongly” (0), and for relationship (closer) and satisfaction the categories are “very much” (1) versus “somewhat or not so much” (0). Using these categories, we similarly find significant negative effects of intensive caregiving on relationship (−1.14, p = .03) and satisfaction (−0.56, p = .03). Results available on request. Other variables are associated with positive well-being and rewards. Specifically, a heart attack of the care recipient increases the probability of reporting having a purpose in life by 2 percentage points. We find a negative association between history of a heart attack (6 percentage points) and lung disease (5 percentage points) with self-improvement (growth). Being married is positively associated with self-improvement (10 percentage points), and care recipient residence in a living facility increases self-improvement by 11.6 percentage points.

We find several significant associations between other covariates and well-being measures tied to helping the care recipient. While helping the care recipient has brought Black and Hispanic caregivers closer to the care recipient (13 percentage points), as well as those that care for someone who has had a heart attack (5 percentage points), married and male caregivers feel less close (8 and 6 percentage points, respectively). Similarly, if the care recipient lives in an assisted living facility, the relationship between care recipient and caregiver is not closer than before caregiving (11 percentage points), but a higher number of self-care or mobility limitations brings caregivers closer to the care recipient (2 percentage points). Additionally, for Black and Hispanic caregivers, caregiving leads to greater satisfaction that the care recipient is well cared for (4 percentage points) compared to White and non-Hispanic caregivers, respectively, while male caregivers have a lower probability to experience this compared to females (3 percentage points) as well as people who care for someone with arthritis (2 percentage points). A higher number of self-care or mobility limitations leads to less satisfaction that the care recipient is well cared for (1 percentage point).

Discussion and Conclusion

Previous research has found that caregiving contributes to lower mental health of the caregiver (Coe & Van Houtven, 2009; Heger, 2017). However, few studies have addressed the double duties of informal care provision and work (Schmitz & Stroka, 2013) nor examined how intensity of caregiving affects positive and negative mental health outcomes. Prior studies have found a strong relationship between intensive caregiving and mental ill-health (Bom & Stöckel, 2021; Doebler et al., 2017), and this finding persists regardless of employment status (Cannuscio et al., 2004).

Using a U.S. data set of caregivers, we find that providing at least 80 h of care per month to a parent, compared to less intensive caregiving, increases the PHQ-4 scale for anxiety and depression disorders. Focusing on the individual items of the PHQ-4 shows that, while providing intensive care does make caregivers feel more nervous, anxious, on edge, and unable to control or stop worrying, depression symptoms are not significantly affected. These findings may suggest that a better understanding of caregivers’ anxiety could help them better to cope with the stress that is associated with intensive caregiving hours. As increasing symptom severity on the PHQ-4 scales is further associated with self-reported disability days (Kroenke et al., 2009), lowering the stress levels of caregivers may also have a positive spillover effect on reducing work absence. While previous studies find a positive association between informal care and depressive symptoms, these approaches did not infer causality in the associations of their findings (Cannuscio et al., 2004). In addition, we are considering intensive as opposed to nonintensive caregiving which might be different from correlational studies that examine higher weekly time commitment to informal care as compared to less caregiving. For these reasons combined, we would expect different results from Cannuscio, and our main contribution is that we carefully try to estimate a causal effect of intensive caregiving on mental health.

The majority of past studies have examined only negative effects to mental health, often due to data limitations, which prevents a more balanced inquiry into caregiving’s full impacts on well-being. Qualitative research describes multiple positive gains from caregiving (Broyles et al., 2016; López et al., 2005). Qualitative findings on gains should be juxtaposed against quantitatively driven quasi-experimental methods that estimate causal effects of intensive caregiving on caregiver well-being. NHATS/NSOC is one of the few surveys that collects information on caregiver well-being and rewards, filling an important data gap. At least among adult children caregivers of older adults, we find a decrease in rewards from caregiving for intensive caregivers, in that they are less likely to have high relationship quality with the care recipient and are less likely to report satisfaction from caregiving. However, self-actualization was no different by intensity. It is important to keep in mind that this is measured based on the hours of care, that is, comparing those with 80 or more hours per month to those with fewer caregiving hours as the reference group. It may be that examining the extensive margin, or comparing caregivers to those who do not provide care, may show differences in other reward domains. We find no evidence that working affects mental health for the caregivers in our sample. While working can have a protective, usually short-term effect on overall health, cognitive functioning (Coe & Zamarro, 2011), and mental health (Kolodziej & García-Gomez, 2019), previous studies usually concentrate on exiting the labor force through retirement, examining an older population but did not focus on caregivers. We are unable to directly compare our findings to the retirement literature that examines cognition and mental health outcomes; however, we are not able to differentiate between working status of caregivers and noncaregivers with the data. Thus, our inference is limited to caregiver effects by intensity.

Our study has several limitations. To identify causal effects, the results have to be interpreted as local average treatment effects (LATE), meaning that the findings affect the compliers; individuals whose caregiving hours are altered by the number of children the parent care recipient has. Caregiving within a family is a decidedly complex decision (Checkovich & Stern, 2002; Engers & Stern, 2002; Lin & Wolf, 2020), and there may be individuals in the sample for which the monotonicity assumption of the IV approach does not hold. For these “defiers,” having one more sibling would not make them less likely to be an intensive caregiver. In that case, our estimates should be interpreted not as a LATE, but an average treatment effect. Furthermore, while existing studies in developed countries suggest there is no direct relationship between the total number of children and mental health (Lawson & Mace, 2010), it is possible that family structure affects mental health directly and not only through the caregiving decision; if this is true, our system of equations would be underidentified. In addition, we treat NSOC as a convenience sample to infer causal relationship in intensive caregiving, work, and mental health outcomes of caregivers. While we do not infer that our results are nationally representative, our results hold in robustness checks, when we include care recipient’s age, race/ethnicity, and the strata variable that considers geographic clustering in the regression to account for the survey design (Solon et al., 2015) and are less precise when we treat NSOC as nationally representative using cross-sectional weights (Supplementary Appendix Tables 5–10). Additionally, we focus on intensive compared to nonintensive caregivers, whereas it would be helpful to examine noncaregivers for more generalizability across all adult children with disabled parents. Future work should identify long-term mental health effects and whether mental health is regained after a caregiving episode, which would require additional data that follow caregivers after a caregiving episode has ended.

Caregiver buffers, highlighted in the conceptual model, could be expanded and targeted to ameliorate the mental health losses for intensive caregivers. Currently, most of these buffers are available to only those within the VA or the Medicaid program. Some programs, such as direct stipend programs, state tax credits, and the CAPABLE program, which pairs an occupational therapist with a handyman, have been found to significantly affect caregiver outcomes broadly (Smith et al., 2019; Sperber et al., 2019; Szanton et al., 2011; Van Houtven et al., 2019; Van Houtven, Lippmann et al., 2020). However, less than 10% of caregivers nationally report receiving training for their role (Burgdorf et al., 2020; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016), and few caregivers receive direct payments from government programs such as found in the VA health care system and in over half of states’ Medicaid Waiver programs (115C). Receipt of other formal care in the home is a more common support for family caregivers, with almost 37% of caregivers of persons with two or more limitations in self-care or mobility activities receiving formal home care in 2016 (Coe et al., 2020). Additionally, job supports such as paid family and paid sick leave can buffer the strains of caregivers who juggle work and caregiving duties (Coe et al., 2021; Hill, 2013). Caregivers may willingly provide care, but the mental health effects of intensive caregivers suggest that caregiver buffers that reduce the objective demands (e.g., time) spent caregiving, or that supported intensive working caregivers (e.g., work flexibility), could reduce or even prevent well-being losses, improve the caregiver’s relationship with the care recipient, and potentially create other positive spillovers that we did not quantify, such as the quality and duration of caregiving provided.

Our article contributes to previous findings of how caregiving affects mental health, specifically by considering the endogeneity of work and caregiving on mental health outcomes. We further add to the empirical literature on gains from caregiving, extending the mainly exploratory and correlational evidence by considering causal effects. Differences in the effects on the scales as opposed to the cutoff point of having two or more symptoms suggest that a more detailed look at the scores and the distribution of the scores might help to paint a more complete picture. With nearly two thirds of caregivers employed, considering both, effects of caregiving and work are essential when considering mental health effects and when designing treatments and interventions to address poor mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Megan Shepherd-Banigan and Kate Miller for their input on the conceptual model and Douglas A. Wolff as well as participants of the NHATS 10th Anniversary Conference for valuable feedback on the paper. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the NHATS 10th Anniversary Virtual Conference, May 26–27, 2021. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent those of their employers or the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Ingo W K Kolodziej, RWI — Leibniz Institute for Economic Research, Essen, Germany; Fresenius University of Applied Sciences, Idstein, Germany.

Norma B Coe, Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Courtney H Van Houtven, Department of Population Health Sciences and Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Duke VA HCS, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT), Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institute on Aging (P30AG012846 and U01AG032947). Coe was supported by the National Institute on Aging (P30AG012836). Dr. Van Houtven was supported by the Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation at the Durham VA Health Care System (Grant No. CIN 13-410) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Research Career Scientist Program (RCS-21-137). This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored by the University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health with support from the National Institute on Aging (U01AG032947 and P30AG012846).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

All authors planned the study, I. W. K. Kolodziej performed all data construction of the analytical data set and performed statistical analysis, all authors reviewed results and suggested revisions to analysis, and all authors contributed to writing of the manuscript, revision, and final review.

References

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (2001). Instrumental variables and the search for identification: From supply and demand to natural experiments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 69–85. doi: 10.1257/jep.15.4.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, J. M., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2015). Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. Journal of Population Ageing, 8(3), 113–145. doi: 10.1007/s12062-015-9116-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, B., Fiebig, D. G., & Hall, J. (2014). Well-being losses due to care-giving. Journal of Health Economics, 35(100), 123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, K., Lindgren, B., & Lundborg, P. (2008). Your next of kin or your own career? Caring and working among the 50+ of Europe. Journal of Health Economics, 27(3), 718–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bom, J., Bakx, P., Schut, F., & van Doorslaer, E. (2019). Health effects of caring for and about parents and spouses. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 14, 100196. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2019.100196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bom, J., & Stöckel, J. (2021). Is the grass greener on the other side? The health impact of providing informal care in the UK and the Netherlands. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 269, 113562. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsang, E., Adam, S., & Perelman, S. (2012). Does retirement affect cognitive functioning?. Journal of Health Economics, 31(3), 490–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenna, E., & Di Novi, C. (2016). Is caring for older parents detrimental to women’s mental health? The role of the European North–South gradient. Review of Economics of the Household, 14(4), 745–778. doi: 10.1007/s11150-015-9296-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. M., & Brown, S. L. (2014). Informal caregiving: A reappraisal of effects on caregivers. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 74–102. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles, I. H., Sperber, N. R., Voils, C. I., Konetzka, R. T., Coe, N. B., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2016). Understanding the context for long-term care planning. Medical Care Research and Review, 73(3), 349–368. doi: 10.1177/1077558715614480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf, J. G., Arbaje, A. I., & Wolff, J. L. (2020). Training needs among family caregivers assisting during home health, as identified by home health clinicians. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(12), 1914–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannuscio, C. C., Colditz, G. A., Rimm, E. B., Berkman, L. F., Jones, C. P., & Kawachi, I. (2004). Employment status, social ties, and caregivers’ mental health. Social Science and Medicine (1982), 58(7), 1247–1256. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00317-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkovich, T. J. & Stern, S. (2002). Shared caregiving responsibilities of adult siblings with elderly parents. The Journal of Human Resources, 37(3), 441–478. doi: 10.2307/3069678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coe, N. B., Kolodziej, I. W. K., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2021). Does informal care impact work intensity and productivity? mimeo. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, N. B., Taggert, E., Konetzka, R. T., & van Houtven, C. H. (2020). Informal and formal home care for older adults with disabilities increased, 2004–16. Health Affairs, 39(8), 1297–1301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe, N. B., von Gaudecker, H. M., Lindeboom, M., & Maurer, J. (2012). The effect of retirement on cognitive functioning. Health Economics, 21(8), 913–927. doi: 10.1002/hec.1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe, N. B., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2009). Caring for mom and neglecting yourself? The health effects of caring for an elderly parent. Health Economics, 18(9), 991–1010. doi: 10.1002/hec.1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe N. B. & Zamarro, G. (2011). Retirement effects on health in Europe. Journal of health Economics, 30(1), 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do, Y. K., Norton, E. C., Stearns, S. C., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2015). Informal care and caregiver’s health. Health Economics, 24(2), 224–237. doi: 10.1002/hec.3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebler, S., Ryan, A., Shortall, S., & Maguire, A. (2017). Informal care-giving and mental ill-health—Differential relationships by workload, gender, age and area-remoteness in a UK region. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 987–999. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, A., Lang, S., & Seebaß, K. (2017). The impact of informal care and employment on the mental health of the caregiver. Sozialer Fortschritt, 66(1), 77–96. doi: 10.3790/sfo.66.1.77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engers, M., & Stern, S. (2002). Long-term care and family bargaining. International Economic Review, 43, 73–114. doi: 10.1111/1468-2354.t01-1-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner, S. L. (1995). The impact of “parent care” on female labor supply decisions. Demography, 32(1), 63–80. doi: 10.2307/2061897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., Cornman, J. C., & Carr, D. (2014). Is spousal caregiving associated with enhanced well-being? New evidence from the panel study of income dynamics. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(6), 861–869. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V., Skehan, M., Wolff, J., & Kasper, J. (2019). National study of caregiving I–III user guide. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. www.nhats.org. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., & Wolff, J. L. (2020). The changing landscape of family caregiving in the United States. In Sawhill I. V. & Stevenson B. (Eds.), Paid leave for caregiving. AEI/Brookings. [Google Scholar]

- Heger, D. (2017). The mental health of children providing care to their elderly parent. Health Economics, 26(12), 1617–1629. doi: 10.1002/hec.3457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, H. (2013). Paid sick leave and job stability. Work and Occupations, 40(2), 143–173. doi: 10.1177/0730888413480893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. C., Laporte, A., Van Houtven, C. H., & Coyte, P. C. (2014). Caregiving intensity and retirement status in Canada. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 102, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J., Van Houtven, C. H., Laporte, A., & Coyte, P. (2017). The impact of informal caregiving intensity on women’s retirement in the United States. Journal of Population Ageing, 10, 159–180. doi: 10.1007/s12062-016-9154-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. C., Van Houtven, C. H., Tanielian, T., & Ramchand, R. (2019). Economic spillover effects of intensive unpaid caregiving. PharmacoEconomics, 37(4), 553–562. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00784-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. D. & Freedman, V. A. (2018). National Health and Aging Trends Study User Guide: Rounds 1–7 Final Release. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej, I. W., & García-Gómez, P. (2019). Saved by retirement: Beyond the mean effect on mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 225, 85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej, I. W. K., Reichert, A. R., & Schmitz, H. (2018). New evidence on employment effects of informal care provision in Europe. Health Services Research, 53(4), 2027–2046. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, B. J. (1997). Gain in the caregiving experience: Where are we? What next?. The Gerontologist, 37(2), 218–232. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K. (2003). The interface between physical and psychological symptoms. Primary care companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. https://www.psychiatrist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/24910_interface-between-physical-psychological-symptoms.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavela, S. L., & Ather, N. (2010). Psychological health in older adult spousal caregivers of older adults. Chronic Illness, 6(1), 67–80. doi: 10.1177/1742395309356943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D. W., & Mace, R. (2010). Siblings and childhood mental health: Evidence for a later-born advantage. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 70(12), 2061–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, A. (2010). Informal care and labor market participation. Labour Economics, 17(1), 140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2009.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I. F., Fee, H. R., & Wu, H. S. (2012). Negative and positive caregiving experiences: A closer look at the intersection of gender and relationships. Family Relations, 61(2), 343–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00692.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, I. F., & Wolf, D. A. (2020). Division of parent care among adult children. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(10), 2230–2239. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López, J., López-Arrieta, J., & Crespo, M. (2005). Factors associated with the positive impact of caring for elderly and dependent relatives. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 41(1), 81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lousdal, M. L. (2018). An introduction to instrumental variable assumptions, validation and estimation. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 15(1), 1. doi: 10.1186/s12982-018-0069-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, A., & Greenwood, N. (2012). Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(17), 1413–1422. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.650307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an Aging America. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. (2020). Caregiving in the U.S.https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states-01-21.pdf

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning, M. J., & Wu, Z. (2015). Caregiver stress and mental health: Impact of caregiving relationship and gender. The Gerontologist, 56(6), 1102–1113. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick, C. A., Kales, H. C., & Birditt, K. S. (2017). Perceptions of purpose in life within spousal care dyads: Associations with emotional and physical caregiving difficulties. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(1), 77–87. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno, R. A., & Resch, N. L. (1989). Mental health of caregiving spouses: Coping as mediator, moderator, or main effect?. Psychology and Aging, 4(4), 454–463. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.4.454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, C., & Toms, G. (2018). Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers’ well-being: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e584–e596. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschick, M., & Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (2004). The costs and rewards of caregiving among aging spouses and adult children. Family Relations, 53(3), 317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.0008.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robison, J. T., Shugrue, N. A., Fortinsky, R. H., Fabius, C. D., Baker, K., Porter, M., & Grady, J. J. (2020). A new stage of the caregiving career: Informal caregiving after long-term institutionalization. The Gerontologist, 61(8), 1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D. L., Fredman, L., & Haley, W. E. (2015). Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. The Gerontologist, 55(2), 309–319. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, E., & Windmeijer, F. (2016). A weak instrument [Formula: see text]-test in linear IV models with multiple endogenous variables. Journal of Econometrics, 190(2), 212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, H., & Stroka, M. A. (2013). Health and the double burden of full-time work and informal care provision—Evidence from administrative data. Labour Economics, 24, 305–322. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2013.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, H., & Westphal, M. (2015). Short- and medium-term effects of informal care provision on female caregivers’ health. Journal of Health Economics, 42, 174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd-Banigan, M., Sperber, N., McKenna, K., Pogoda, T. K., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2020). Leveraging institutional support for family caregivers to meet the health and vocational needs of persons with disabilities. Nursing Outlook, 68(2), 184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skira, M. (2015). Dynamic wage and employment effects of elder parent care. International Economic Review, 56(1), 63–93. doi: 10.1111/iere.12095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. A., Lindquist, J., Miller, K. E. M., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Olsen, M., Campbell-Kotler, M., Henius, J., Kabat, M., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2019). Comprehensive family caregiver support and caregiver well-being: Preliminary evidence from a pre-post-survey study with a non-equivalent control group. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 122. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solon, G., Haider, S. J., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). What are we weighting for? Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 301–316. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/581177 [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, N. R., Boucher, N. A., Delgado, R., Shepherd-Banigan, M. E., McKenna, K., Moore, M., Barrett, R., Kabat, M., & Van Houtven, C. H. (2019). Including family caregivers in seriously ill veterans’ care: A mixed-methods study. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 38(6), 957–963. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanton, S. L., Thorpe, R. J., Boyd, C., Tanner, E. K., Leff, B., Agree, E., Xue, Q. L., Allen, J. K., Seplaki, C. L., Weiss, C. O., Guralnik, J. M., & Gitlin, L. N. (2011). Community aging in place, advancing better living for elders: A bio-behavioral–environmental intervention to improve function and health-related quality of life in disabled older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(12), 2314–2320. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03698.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., DePasquale, N., & Coe, N. B. (2020). Essential long-term care workers commonly hold second jobs and double- or triple-duty caregiving roles. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1657–1660. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., Lippmann, S. J., Bélanger, E., Smith, V. A., James, H. J., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Jutkowitz, E., O’Brien, E., Wolff, J. L., Burke, J. R., & Plassman, B. L. (2020). Measurement properties of the CAPACITY instrument to assess perceived communication with the health care team among care partners of patients with cognitive impairment. Medical Care, 58(9), 842–849. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., & Norton, E. C. (2004). Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics, 23(6), 1159–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., Smith, V. A., Stechuchak, K. M., Shepherd-Banigan, M., Hastings, S. N., Maciejewski, M. L., Wieland, G. D., Olsen, M. K., Miller, K. E. M., Kabat, M., Henius, J., Campbell-Kotler, M., & Oddone, E. Z. (2019). Comprehensive support for family caregivers: Impact on veteran health care utilization and costs. Medical Care Research and Review, 76(1), 89–114. doi: 10.1177/1077558717697015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven, C. H., Voils, C. I., & Weinberger, M. (2011). An organizing framework for informal caregiver interventions: Detailing caregiving activities and caregiver and care recipient outcomes to optimize evaluation efforts. BMC Geriatrics, 11, 77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., & Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwart, P. L., Bakx, P., & van Doorslaer, E. K. A. (2017). Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m 64? The health impact of caregiving to one’s spouse. Health Economics, 26(Suppl. 2), 127–138. doi: 10.1002/hec.3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.