Abstract

Introduction

Evidence is lacking on second-line and later treatments for patients with RAS wild-type colorectal cancer (CRC) who receive first-line anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody therapy. In this study, we explored the real-world treatment sequences, treatment duration, and factors associated with treatment sequences and durations in Japanese patients with CRC.

Methods

This retrospective observational cohort study used a Japanese administrative claims database (April 2008 to July 2021). Patients with confirmed CRC (presumed RAS wild-type) who received first-line FOLFOX (leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin) plus anti-EGFR therapy in or after May 2016, followed by second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus an antiangiogenic drug, were included. Treatment durations were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Cox regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with treatment duration.

Results

Analysis populations consisted of 1163 (first-line and second-line) and 645 (third-line) patients. At the start of first-line therapy, 67.8% of patients were male, the mean age was 64 years, 83.4% had left-sided CRC, and 84.3% were prescribed FOLFOX plus panitumumab. For second-line therapy, patients were prescribed bevacizumab (63%), ramucirumab (27%), or aflibercept beta (10%). Median (95% CI) treatment durations from the start of second-line therapy to the end of antitumor drug therapies were similar for bevacizumab (12.5 months [11.2, 14.0]), ramucirumab (12.5 months [11.2, 14.8]), and aflibercept beta (14.0 months [10.4, 17.0]). Treatment duration from second-line was positively associated with first-line treatment duration of 6 months or more, CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, and liver surgery during first-line therapy, and was negatively associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before second-line therapy.

Conclusion

Real-world data revealed that all three antiangiogenic drugs were used as second-line therapy after first-line anti-EGFR antibodies and showed similar treatment durations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-022-02122-4.

Keywords: Aflibercept; Angiogenesis inhibitors; Bevacizumab; Carcinoma, colorectal; Irinotecan; Observational study; Ramucirumab

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Second-line antiangiogenic drugs in combination with chemotherapy are recommended for patients with RAS wild-type colorectal cancer (CRC) who have previously received first-line anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody therapy, but little evidence is available on the most appropriate second- and third-line treatment sequences for these patients. |

| This study assessed real-world treatment sequences, treatment duration, and clinical characteristics of Japanese patients who received first-line FOLFOX in combination with anti-EGFR antibody therapy, followed by second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy in combination with antiangiogenic drugs, and explored the factors associated with treatment sequences and durations from second-line therapy. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Treatment durations from second-line therapy after first-line anti-EGFR therapy were similar for patients who had received each second-line antiangiogenic drug (bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept beta). |

| Factors positively associated with treatment duration from second-line therapy were duration of first-line therapy, CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, and liver surgery during first-line therapy; negative factors associated with treatment duration were related to patient health status. |

| This study provides real-world evidence on the use of antiangiogenic drugs, including the newer drugs ramucirumab and aflibercept beta for patients with RAS wild-type CRC following first-line treatment with an anti-EGFR antibody. |

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers globally, is associated with high rates of cancer-related mortality [1–3]. Although new treatment options have become available for patients with CRC in recent years, CRC-related deaths in Japan have not decreased [2, 4, 5]. Previously, we showed that treatment patterns of advanced CRC in real-world clinical practice in Japan are consistent with international and Japanese guidelines (Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum [JSCCR]) [6]. For patients with left-sided RAS wild-type metastatic CRC (mCRC), the standard first-line treatment is chemotherapy with an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody [5, 7]. However, because of the potential for post-progression therapy to contribute to prolonged survival in patients with cancer, including in those with CRC [8–10], more information is needed on the treatment options available for patients with CRC who receive second and later lines of therapy.

Although there is consensus that second-line antiangiogenic drugs in combination with chemotherapy should be considered for patients with RAS wild-type CRC who have previously received first-line anti-EGFR therapy [5, 11], there is very little evidence from clinical trials to guide clinicians on the most appropriate second- and third-line treatment sequences for these patients [11]. In Japan, bevacizumab became available for use in combination with various chemotherapy regimens for patients with CRC in April 2007, followed by ramucirumab (in May 2016) and aflibercept beta (in March 2017) for combination with second-line FOLFIRI (leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil [5-FU] + irinotecan) [5, 6]. However, use of ramucirumab and aflibercept beta is largely informed on the basis of clinical trials that did not include patients who received first-line anti-EGFR therapy [12, 13]. Consistent with treatment recommendations [5], findings from our previous analysis that described treatment patterns for patients with advanced CRC (the overall population, cutoff September 2019) using a Japanese hospital-based administrative database showed that FOLFOX (leucovorin + 5-FU + oxaliplatin) with anti-EGFR antibodies was the most commonly prescribed first-line treatment for Japanese patients with presumed RAS wild-type CRC, followed by second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy [6]. In the current study, we used more recent information from this database (cutoff July 2021) to further extend our understanding of the real-world use of prescription medication in Japan, focusing on patients who received first-line anti-EGFR therapy only. This analysis is expected to help inform clinical treatment strategies for post-progression therapy.

The primary objective of this study was to describe the real-world treatment sequences and treatment durations, as well as the demographics and clinical background, of patients with presumed RAS wild-type CRC who received first-line FOLFOX in combination with anti-EGFR therapy, followed by second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy in combination with an antiangiogenic drug. Secondary objectives were to describe the treatment patterns and characteristics of patients by each of the main second- and third-line treatment regimens and to explore the factors associated with treatment sequences and treatment durations.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed data from a large hospital-based administrative database from April 1, 2008 to July 31, 2021 (Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. [MDV]) in Japan [14]. The MDV database, which, as of September 2021, included information from approximately 26% of acute phase hospitals (37.4 million patients) in Japan, comprises administrative claims and Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) data from patient hospitalizations and outpatient visits from DPC hospitals [14]. The DPC system entails a per-day flat-sum payment to hospitals that is based on national averages for acute inpatient care, and DPC hospitals provide both acute medical care and other medical care [15, 16].

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Because all data in this study were de-identified and collected retrospectively, ethical review and informed consent were not required.

Study Populations and Study Protocol

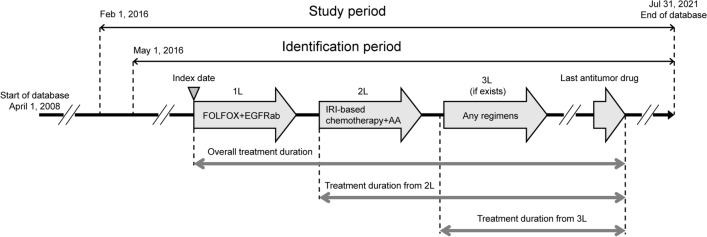

Antitumor drugs (cytotoxic agents, antiangiogenic drugs, anti-EGFR antibodies, other targeted treatments) recommended by the JSCCR guidelines for systemic treatment of patients with advanced CRC [5] were included in this analysis (Table S1 in the supplementary material). For this analysis, the study population comprised patients (1) with a confirmed diagnosis of CRC (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision [ICD-10] codes C18–20) from February 1, 2016 to July 31, 2021; (2) who started first-line FOLFOX plus an anti-EGFR antibody (cetuximab or panitumumab) during the identification period (May 1, 2016 to July 31, 2021); and (3) who subsequently were prescribed second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus an antiangiogenic drug (bevacizumab, ramucirumab, or aflibercept beta) (Table S1 in the supplementary material, Fig. 1). Anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab or panitumumab) are only approved for use in Japan for those patients with CRC who have RAS wild-type alleles. Therefore, although the MDV database does not include gene testing results, patients with CRC in this study were presumed to have the RAS wild-type genotype.

Fig. 1.

Study design. 1L/2L/3L first-line/second-line/third-line, AA antiangiogenic, EGFRab epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody, FOLFOX leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin, IRI irinotecan

Patients were included if they were aged 20 years or older at the start of first-line therapy (index date). Patients were excluded if they had participated in a clinical trial after the index date or who presumably had an early recurrence (i.e., started adjuvant chemotherapy within 3 months of CRC surgery and had switched to second-line therapy within 6 months from the last dose of adjuvant therapy) or had a biological drug prescription (Table S1 in the supplementary material) before the index date.

Patients were followed from the start of first-line therapy (index date) to the end of available data for their antitumor treatments, clinical outcomes, and concomitant therapies (Fig. 1).

Baseline Characteristics and Treatment Patterns

Patient characteristics were analyzed at baseline, which was defined as the 60 days before the start of each line of therapy. Functional independence was measured using the 10-item Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) index [17], which has good concordance with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [18]. Independent ADL was defined as all 10 items recorded as independent, and dependent ADL was defined as any items recorded as not independent. For patients with any ADL items missing, ADL was defined as “missing”. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height information. Both ADL and BMI were limited to patients with hospitalizations within each baseline period because this information was only available from the discharge summary in the MDV database. Treatment regimens were defined as the combination of drugs prescribed within the first 28 days after the start of each line of therapy, except for all biological drugs (but not pembrolizumab), which could be added to chemotherapy regimens even after the first 28 days. The end of each line of therapy occurred when patients had terminated all CRC drugs in the regimen for at least 180 days or started a new CRC drug not in the regimen. The four fluoropyrimidine drugs (Table S1 in the supplementary material) were considered interchangeable. The end date was the date of the last prescription plus the number of days of supply minus 1 day. If new CRC drugs were introduced earlier (causing the regimen/line to advance), the line ended on the day before the introduction of the new CRC drug(s).

Statistical Analysis

Treatment durations (median, 95% confidence interval [CI]) from the start of first-, second-, and third-line therapy were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were censored at the estimated date of the last dose of antitumor therapy, when the time between the estimated final dose date and the final date of the data provided from the hospital was 60 days or less. Analysis of the factors associated with treatment duration from the start of second-line therapy to the estimated date of the last dose of antitumor drugs was conducted using a Cox regression model. Covariates were selected from the following: patient characteristics, clinical information, antitumor therapies, and other drug prescriptions and procedures before the start of second-line therapy. For the Cox regression model, associations with a p value of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. Because patients with left-sided RAS wild-type tumors are known to benefit from anti-EGFR-based chemotherapy compared with those with right-sided tumors [19, 20], we also conducted an exploratory analysis of the subgroup of patients with left-sided tumors. Descriptive statistics are presented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables. The Instant Health Data (IHD) platform (Panalgo, Boston, MA, USA) was used for sample selection and creation of analytic variables. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Overall Study Population: Patient Selection and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

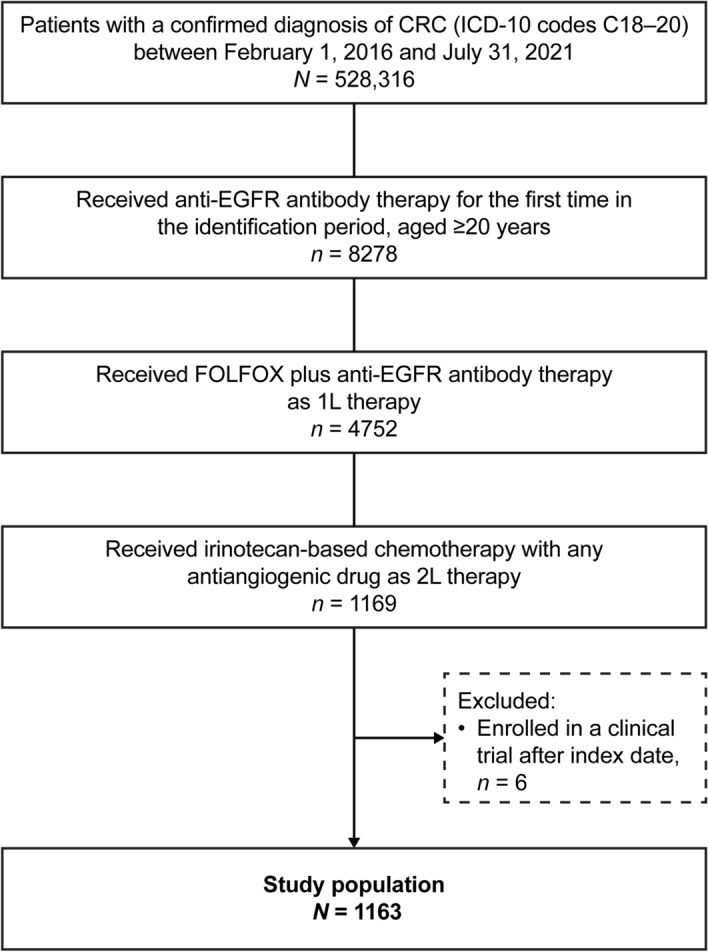

In this analysis, 4752 patients started first-line FOLFOX plus anti-EGFR antibody therapy during the identification period. Of these, 1163 patients subsequently received irinotecan-based chemotherapy in combination with antiangiogenic drugs and met the criteria for inclusion in the study (Fig. 2). These 1163 patients were included in the first- and second-line analysis populations, and 645 patients further received third-line therapy and were included in the third-line analysis population (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 2.

Patient flow diagram. 1L/2L first-line/second-line, CRC colorectal cancer, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, FOLFOX leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin, ICD-10 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision

At the start of first-line therapy, patients had a mean age of 64.2 years and 67.8% (789/1163) were male (Table 1). Most patients had left-sided CRC (83.4%, 970/1163) and liver metastasis (59.2%, 688/1163), and the most commonly recorded concomitant diseases or conditions were hypertension (31.4%, 365/1163), diabetes (24.6%, 286/1163), and dry skin/itching (26.7%, 310/1163). Among the patients with data for ADL, 93.3% (906/971) had independent ADL.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with CRC who started 1L FOLFOX plus an anti-EGFR antibody, followed by 2L irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus any antiangiogenic drug

| Variable | Start of 1L therapy (N = 1163) | Start of 2L therapy (N = 1163) | Start of 2L therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (n = 736) | Ramucirumab (n = 314) | Aflibercept beta (n = 113) | |||

| Number of hospital beds | |||||

| < 200 beds | 45 (3.9) | 30 (4.1) | 13 (4.1) | 2 (1.8) | |

| 200–499 beds | 641 (55.1) | 394 (53.5) | 192 (61.1) | 55 (48.7) | |

| ≥ 500 beds | 477 (41.0) | 312 (42.4) | 109 (34.7) | 56 (49.6) | |

| Designated cancer hospital | 907 (78.0) | 563 (76.5) | 246 (78.3) | 98 (86.7) | |

| Demographics/disease characteristics | |||||

| Sex: male | 789 (67.8) | 492 (66.8) | 216 (68.8) | 81 (71.7) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 64.2 (10.5) | 65.0 (10.5)a | 65.1 (10.4)a | 64.7 (10.3)a | 64.6 (11.2)a |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD)b | 22.1 (3.4)c | 21.9 (3.7)d | 22.1 (3.8)e | 21.7 (3.2)f | 21.4 (3.8)g |

| BMI ≤ 18.5 kg/m2 b | 124 (12.6)c | 97 (18.0)d | 55 (15.7)e | 29 (21.3)f | 13 (25.0)g |

| ADL – independentb | 906 (93.3)h | 474 (89.3)i | 303 (88.6)j | 124 (91.9)k | 47 (87.0)l |

| ADL – dependentb | 65 (6.7)h | 57 (10.7)i | 39 (11.4)j | 11 (8.1)k | 7 (13.0)l |

| Left-sided CRCm | 970 (83.4) | 605 (82.2) | 269 (85.7) | 96 (85.0) | |

| Right-sided CRCm | 125 (10.7) | 81 (11.0) | 34 (10.8) | 10 (8.8) | |

| Antitumor therapies | |||||

| CRC surgery before index date | 493 (42.4) | – | 295 (40.1) | 146 (46.5) | 52 (46.0) |

| CRC conversion surgery during 1L therapy | – | 111 (9.5) | 72 (9.8) | 25 (8.0) | 14 (12.4) |

| Liver surgery during 1L therapy | – | 69 (5.9) | 36 (4.9) | 25 (8.0) | 8 (7.1) |

| Lung surgery during 1L therapy | – | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) |

| Duration of 1L therapy, mean, months (SD) | – | 9.57 (6.94) | 9.48 (7.01) | 9.58 (6.92) | 10.11 (6.55) |

| Sites of metastasisb | |||||

| Liver | 688 (59.2) | 719 (61.8) | 456 (62.0) | 187 (59.6) | 76 (67.3) |

| Lung | 191 (16.4) | 237 (20.4) | 139 (18.9) | 78 (24.8) | 20 (17.7) |

| Bone | 47 (4.0) | 77 (6.6) | 51 (6.9) | 21 (6.7) | 5 (4.4) |

| Brain | 7 (0.6) | 9 (0.8) | 8 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Comorbiditiesb | |||||

| Hypertension | 365 (31.4) | 446 (38.3) | 277 (37.6) | 120 (38.2) | 49 (43.4) |

| Diabetes | 286 (24.6) | 316 (27.2) | 192 (26.1) | 90 (28.7) | 34 (30.1) |

| Liver disease | 200 (17.2) | 284 (24.4) | 169 (23.0) | 83 (26.4) | 32 (28.3) |

| Renal disease | 97 (8.3) | 113 (9.7) | 63 (8.6) | 38 (12.1) | 12 (10.6) |

| Dry skin/itching | 310 (26.7) | 924 (79.4) | 581 (78.9) | 248 (79.0) | 95 (84.1) |

| Rash/acne | 77 (6.6) | 383 (33.0) | 247 (33.6) | 106 (33.8) | 30 (26.6) |

| Paronychia | 4 (0.3) | 94 (8.1) | 58 (7.9) | 28 (8.9) | 8 (7.1) |

| Neuropathy | 56 (4.8) | 227 (19.5) | 139 (18.9) | 60 (19.1) | 28 (24.8) |

All values are n (%) unless indicated otherwise

1L/2L first-line/second-line, ADL activities of daily living, BMI body mass index, CRC colorectal cancer, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, FOLFOX leucovorin + 5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin, SD standard deviation

aAssessed at the start of second-line therapy

bAssessed within 60 days before the index date for first-line therapy and within 60 days before starting second-line therapy for second-line therapy

cN = 986

dN = 538

eN = 350

fN = 136

gN = 52

hN = 971

iN = 531

jN = 342

kN = 135

lN = 54

mAssessed within 60 days before the index date for first-line therapy

First-Line Therapy: Treatment Patterns

Of the patients who started first-line FOLFOX with anti-EGFR therapy, most (84.3%, 980/1163) were prescribed panitumumab as the anti-EGFR antibody (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The median (95% CI) duration of first-line therapy was 8.1 (7.8, 8.5) months, and the median (95% CI) overall duration from first-line therapy until the last antitumor drug prescription was 25.6 (24.2, 26.5) months. Overall median treatment duration was numerically longer for patients with left-sided CRC than right-sided CRC (26.3 months vs. 18.8 months) and for those who had undergone surgery for CRC before starting first-line therapy compared with those who had not (29.3 months vs. 23.0 months) (Fig. S2 in the supplementary material). Concomitant procedures and medications prescribed at baseline and during each line of therapy are shown in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Second-Line Therapy: Patient Characteristics and Treatment Patterns by Antiangiogenic Therapy

Most clinical characteristics were similar for the first- and second-line study populations and between each of the second-line therapy antiangiogenic drugs (Table 1). At the start of second-line therapy, 79.4% (924/1163) of patients were recorded as having dry skin/itching, 33.0% (383/1163) had rash/acne, and 19.5% (227/1163) had neuropathy.

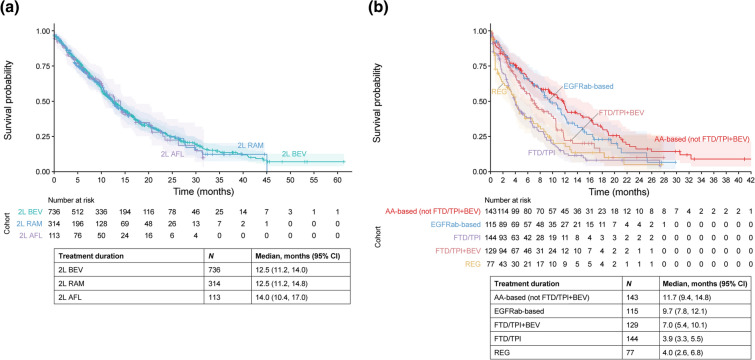

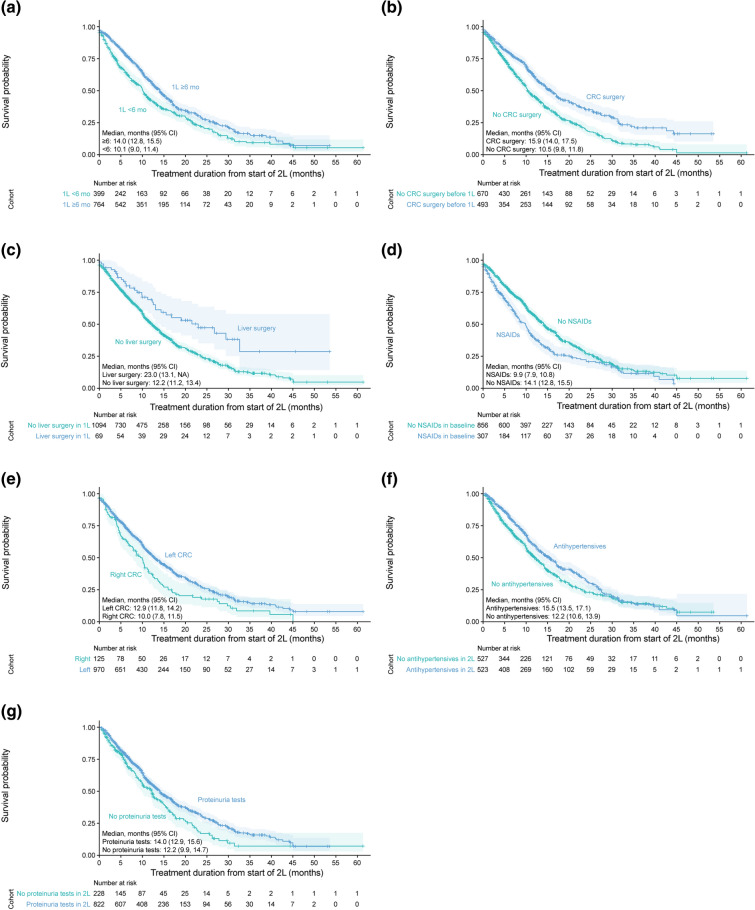

Of those who started second-line irinotecan-based therapy plus an antiangiogenic drug, most were prescribed FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab (52.2%, 607/1163), followed by ramucirumab (27.0%, 314/1163) then aflibercept beta (9.7%, 113/1163) (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). The total percentage of patients prescribed bevacizumab in any combination second-line irinotecan-based therapy was 63.3% (736/1136). The median (95% CI) treatment duration from second-line therapy until the last antitumor drug prescription was 12.5 (11.5, 13.9) months. Treatment durations among the antiangiogenic drugs prescribed were similar; the median (95% CI) treatment durations from second-line therapy were 12.5 (11.2, 14.0) months for bevacizumab, 12.5 (11.2, 14.8) months for ramucirumab, and 14.0 (10.4, 17.0) months for aflibercept beta (Fig. 3a). The median (95% CI) treatment duration from second-line therapy was numerically longer for patients who did than did not receive proteinuria tests (14.0 [12.9, 15.6] and 12.2 [9.9, 14.7] months, respectively) or antihypertensives (15.5 [13.5, 17.1] and 12.2 [10.6, 13.9] months, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Treatment duration from the start of 2L irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus any antiangiogenic drug (a) and from the start of 3L therapy (b) by treatment regimens. 2L/3L second-line/third-line, AA antiangiogenic, AFL aflibercept beta, BEV bevacizumab, CI confidence interval, EGFRab epidermal growth factor receptor antibody, FTD/TPI trifluridine/tipiracil, RAM ramucirumab, REG regorafenib

Fig. 4.

Median treatment duration from 2L irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus antiangiogenic drugs by duration of 1L therapy (a), CRC surgery before the index date (b), liver surgery during 1L therapy (c), NSAID prescription before starting 2L therapy (d), CRC sidedness (e), antihypertensive prescription during 2L therapy (f), and proteinuria tests during 2L therapy (g). For f and g, only patients who received two or more 2L prescriptions for antiangiogenic drugs were included in the analyses in order to evaluate the use of these concomitant therapies during 2L therapy. 1L/2L first-line/second-line, CI confidence interval, CRC colorectal cancer, mo months, NA not applicable, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

The median (95% CI) duration of second-line therapy was 5.4 (5.0, 5.8) months. The percentage of patients who required an antiangiogenic drug dose reduction was 10.7% (124/1163). There were numerically higher percentages of patients with dose reductions for ramucirumab (13.1%, 41/314) and aflibercept beta (18.6%, 21/113) than bevacizumab (8.4%, 62/736). Concomitant medications and procedures during second-line therapy are shown in Table 2. The percentage of patients prescribed antihypertensive drugs during second-line therapy and the change from baseline before starting second-line were numerically higher for second-line ramucirumab (54.1% in second-line and 32.5% in baseline, 21.7% increase) and aflibercept beta (66.4% in second-line and 25.7% in baseline, 40.7% increase) than bevacizumab (44.2% in second-line and 27.9% in baseline, 16.3% increase).

Table 2.

Concomitant procedures and medications prescribed during 2L with any antiangiogenic drug and by 2L antiangiogenic drug

| Variable, n (%) | 2L therapy (n = 1163) | 2L antiangiogenic drug | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (n = 736) | Ramucirumab (n = 314) | Aflibercept beta (n = 113) | ||

| Proteinuria tests | 876 (75.3) | 547 (74.3) | 236 (75.2) | 93 (82.3) |

| Anti-infectives | 562 (48.3) | 358 (48.6) | 148 (47.1) | 56 (49.6) |

| NSAIDs | 446 (38.3) | 291 (39.5) | 107 (34.1) | 48 (42.5) |

| Antihypertensives | 570 (49.0) | 325 (44.2) | 170 (54.1) | 75 (66.4) |

| CRC conversion surgery during second-line therapy | 22 (1.9) | 13 (1.8) | 7 (2.2) | 2 (1.8) |

| Liver surgery during second-line therapy | 17 (1.5) | 12 (1.6) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.8) |

| Lung surgery during second-line therapy | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.9) |

2L second-line, CRC colorectal cancer, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Cox regression analysis was undertaken to investigate the factors associated with treatment duration from second-line therapy (Table 3). The factors significantly associated with longer treatment duration were at least 6 months’ duration of first-line therapy, CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, and liver surgery during first-line therapy (Table 3). The factor significantly associated with shorter treatment durations was use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the baseline period, before starting second-line therapy. In the subgroup of patients for whom total ADL independence and BMI were available, the factors significantly associated with longer treatment duration were CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, at least 6 months’ duration of first-line therapy, and total ADL independence (Table S3 in the supplementary material). No factors were negatively associated with treatment duration in this subgroup analysis.

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis of the factors associated with treatment duration from the start of 2L irinotecan-based chemotherapy plus any antiangiogenic drug (n = 1163)

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and disease characteristics | |||

| ≥ 70 years at start of 2L therapya | 1.10 | 0.94, 1.29 | 0.25 |

| Sex: male | 1.13 | 0.96, 1.33 | 0.15 |

| Left-sided CRC | 0.86 | 0.70, 1.05 | 0.14 |

| Metastases/comorbidities before starting 2L therapyb | |||

| Liver metastases | 1.11 | 0.94, 1.30 | 0.21 |

| Lung metastases | 0.90 | 0.74, 1.09 | 0.29 |

| Diabetes | 1.06 | 0.89, 1.26 | 0.51 |

| Renal disease | 1.16 | 0.90, 1.49 | 0.26 |

| Liver disease | 0.99 | 0.83, 1.18 | 0.91 |

| Supportive medications before starting 2L therapyb | |||

| NSAIDsa | 1.31 | 1.10, 1.55 | < 0.01 |

| Antihypertensivesa | 1.11 | 0.94, 1.32 | 0.22 |

| Prior antitumor therapies | |||

| CRC surgery before index date | 0.66 | 0.56, 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| CRC conversion surgery during 1L therapy | 1.01 | 0.78, 1.32 | 0.93 |

| Liver surgery during 1L therapy | 0.62 | 0.43, 0.90 | 0.01 |

| Duration of 1L therapy ≥ 6 monthsa | 0.78 | 0.66, 0.91 | < 0.01 |

1L/2L first-line/second-line, CI confidence interval, CRC colorectal cancer, HR hazard ratio, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

aWithin 60 days before starting 2L therapy, 37.9% (441/1163) of patients were ≥ 70 years of age, 26.4% (307/1163) of patients were prescribed NSAIDs, 28.9% (336/1163) were prescribed antihypertensives, and 65.7% (764/1163) had duration of 1L therapy ≥ 6 months

bWithin 60 days before starting 2L therapy

Findings from the Kaplan–Meier analysis for subgroups of interest were consistent with the Cox regression analysis (Fig. 4). The median (95% CI) treatment duration from second-line therapy was longer in patients with at least 6 months’ duration of first-line therapy than those with less than 6 months’ duration (14.0 [12.8, 15.5] vs. 10.1 [9.0, 11.4] months), and in patients who underwent CRC surgery before the index date (15.9 [14.0, 17.5] vs. 10.5 [9.8, 11.8] months) or liver surgery during first-line therapy (23.0 [13.1, NA] vs. 12.2 [11.2, 13.4] months) compared with those who did not. In addition, median treatment duration from second-line therapy was significantly shorter for patients with prior use of NSAIDs (9.9 [7.9, 10.8] vs. 14.1 [12.8, 15.5] months) than for those without prior use. The median (95% CI) treatment duration appeared to be numerically longer for those with left-sided CRC than for those with right-sided CRC (12.9 [11.8, 14.2] vs. 10.0 [7.8, 11.5] months).

Third-Line Therapy: Patient Characteristics and Treatment Patterns by Treatment Regimen

For third-line therapy, 42.3% (273/645) of patients were prescribed trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI) with (20.0%,129/645) or without (22.3%,144/645) bevacizumab; 22.1% (143/645) were prescribed other antiangiogenic-based therapy; 17.8% (115/645) were rechallenged with anti-EGFR antibody therapy; 11.9% (77/645) were prescribed regorafenib; and 5.7% (37/645) were prescribed other treatments (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). Overall, the third-line antiangiogenic-based and anti-EGFR antibody-based treatment regimens were highly heterogenous (Table S4 in the supplementary material). The median (95% CI) duration of therapy from third-line therapy until the last antitumor drug prescription was 7.0 (6.3, 8.5) months and varied widely across the different third-line regimens (Fig. 3b).

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients among the third-line treatment groups are shown in Table S5 in the supplementary material. Patients who received regorafenib and FTD/TPI with and without bevacizumab were more ADL dependent than in the other treatment groups (approx. 15–26% vs. approx. 4–11%), although the number of patients with data for ADL was very small. The health status such as presence of comorbidities of patients at the start of third-line therapy was worse than it was at the start of first-line therapy (Table 1, Table S5 in the supplementary material). In particular, the percentage of patients with dependent ADL had increased more than two-fold (from ca. 7% to 14%).

Subgroup Analysis of Patients with Left-Sided CRC

Patient characteristics (Table S6 in the supplementary material), treatment patterns (Fig. S3 in the supplementary material), treatment durations (Fig. S4 in the supplementary material), and the factors associated with treatment duration from second-line (Table S7 in the supplementary material) in patients with left-sided CRC were consistent with the findings for the entire study population.

Discussion

This study showed that treatment duration from second-line therapy did not appear to differ among patients with a prescription for bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept beta in patients with presumed RAS wild-type CRC who had received first-line anti-EGFR antibody therapy. This is the first study to provide real-world clinical insights from a large-scale administrative database into second-line treatment sequences for bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept beta in this patient population. First-line treatment duration of 6 months or more, CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, and liver surgery during first-line therapy were positively associated with duration from second-line treatment, and use of NSAIDs in the baseline period before starting second-line therapy was negatively associated. The findings provide clinically relevant evidence for physicians when considering treatment options for these patients and suggest that the appropriate use and management of patient health status were important for treatment continuation.

Increased survival has been demonstrated in clinical trials for second-line use of bevacizumab [21], ramucirumab [13], and aflibercept beta [12, 22], and these antiangiogenic drugs are currently recommended in second-line therapy for patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent CRC [5, 7]. Consistent with these recommendations, our previous study, with a September 2019 cutoff, showed that these antiangiogenic drugs were used commonly as second-line therapy for patients with advanced CRC, regardless of first-line treatment choices [5, 6]. Despite this, information on the optimal treatment sequences for these patients, especially after first-line anti-EGFR therapy, is lacking. Each of the antiangiogenic drugs has specific molecular targets and mechanisms of action [23]; therefore, it is relevant to assess the differences in outcomes of therapy with these drugs. In this real-world study in Japanese patients with advanced CRC, median treatment duration from second-line chemotherapy with an antiangiogenic drug was 12.5 months, and there appeared to be no differences in treatment duration by antiangiogenic drugs. These findings are similar to previous reports that studied the effectiveness of antiangiogenic drugs after first-line anti-EGFR antibody therapy [24–27]. However, results from retrospective studies need to be interpreted with caution and should be understood primarily as a sole description of real-world clinical practice because important clinical information for treatment decisions may not be available, and therefore comparative effectiveness evaluation of superiority among therapy choices with appropriate background adjustment is often difficult, especially in administrative database studies [28, 29].

The proportions of patients with a prescription for concomitant medications or procedures during second-line therapy were similar across each of the antiangiogenic drug groups, except for antihypertensive drugs, which were prescribed more frequently to patients receiving second-line ramucirumab and aflibercept beta than bevacizumab. This trend is similar to the higher incidence of hypertension with ramucirumab and aflibercept beta compared with bevacizumab in clinical trials [13, 22, 30], potentially leading to the differences in the frequency of antihypertensive drugs between the antiangiogenic treatment groups.

In the Cox regression analysis, we showed that duration of first-line therapy of 6 months or more, CRC surgery before starting first-line therapy, and liver surgery during first-line therapy were positively associated with treatment duration from second-line therapy. A retrospective study in Japan and a phase III RAISE trial of ramucirumab reported the prognostic role of progression-free survival (PFS) and time to progression, respectively, of first-line therapy for second-line irinotecan-based chemotherapy in patients with mCRC [31, 32]. As for CRC surgery before first-line therapy, an integrated analysis of eight randomized clinical trials reported that primary tumor resection for patients with synchronous mCRC was associated with better prognosis [33]. Also, the prognosis of patients with metachronous (recurrent) mCRC was better than for patients with unresected synchronous mCRC. These are in alignment with our results because our study population with CRC surgery before first-line therapy was likely to include patients with both resected synchronous and metachronous disease. However, a recent randomized clinical trial in Japan in patients with synchronous mCRC did not show benefit with primary tumor resection, and therefore the prognostic role of primary tumor resection is still under debate [34]. In the current study, 59.2% of patients had liver metastases and 5.9% had undergone liver resection during first-line therapy. The significant association of liver surgery with treatment duration is consistent with clinical practice (where approximately two-thirds of recurrent CRC involves the liver) and a study reporting that liver resection is associated with long-term survival [35]. However, the potential benefits of liver resection in this study need to be interpreted carefully because of the small sample size. In contrast, use of NSAIDs was a consistent negative factor in this study. This conflicts with a previous study reporting that appropriate use of NSAIDs improved the prognosis of patients with CRC [36]. A potential reason for this difference may be because the limited clinical information in our administrative database can lead to confounding (i.e., the use of NSAIDs for treatment of pain). Therefore, our results may suggest that conditions such as pain requiring NSAID treatment had an adverse impact on treatment continuation. ADL independence was another factor associated with treatment duration in our subgroup analysis, indicating the importance of the health status for treatment continuation. We also observed that patients’ health status, as indicated by comorbidities and ADL, deteriorated as patients progressed from before first-line to before third-line therapy. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of maintaining good health status among patients as they transition to subsequent lines of therapy.

Several other factors were identified in subgroup Kaplan–Meier analyses that may be associated with longer treatment durations. First, patients with left-sided tumors showed numerically longer treatment duration from second line than those with right-sided tumors. Primary tumor location is an established prognostic factor for treatment benefit in patients with CRC [7], and patients with left-sided RAS wild-type tumors in particular benefit from chemotherapy with anti-EGFR therapy [19, 20]. Also, a retrospective analysis of the FIRE-3 phase III trial reported numerically longer PFS and overall survival (OS) in patients with left-sided tumors for the second-line anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy after first-line cetuximab [37]. Second, treatment duration from second-line therapy was numerically longer in those who had used antihypertensives or proteinuria tests than in those who had not. As proteinuria and hypertension are known adverse events associated with the antiangiogenic drug class [38–40], this suggests that patient management and monitoring for known adverse events during second-line therapy may contribute to improved outcomes. Furthermore, findings from a retrospective study showed that hypertension may be associated with the effectiveness of antiangiogenic therapies [41]. However, a causal relationship between prescription of antihypertensives or proteinuria tests and treatment duration cannot be confirmed because it is also possible that patients who remained in second-line therapy longer were more likely to have received an antihypertensive prescription or proteinuria test.

The current standard third-line therapy for patients with mCRC in Japan is limited to FTD/TPI monotherapy and the small-molecule drug, regorafenib [5]. In this study, treatment choices for third-line therapy were highly heterogenous. The durations of treatment for patients receiving third-line FTD/TPI monotherapy or regorafenib were numerically lower compared with third-line antiangiogenic- and anti-EGFR-based treatments. Patients receiving third-line FTD/TPI monotherapy or regorafenib appeared to be slightly older and have worse ADL status; therefore, it is possible that these therapies were chosen for more vulnerable patients, leading to shorter therapy continuation as a result. However, these findings are considered exploratory only because the availability of ADL data was limited to a small number of patients.

The main strength of this study is the use of a large-scale administrative claims database, which can provide evidence on the real-world use of prescription medication, monitoring procedures, and treatment patterns for patients receiving drug combinations that are not typically studied in clinical trials.

However, although administrative claims databases typically provide clinically relevant information on large numbers of patients, data are not collected for research purposes. Important clinical information on disease characteristics (e.g., cancer stage, performance status), effectiveness outcomes (e.g., OS, PFS, overall response rate), and reasons for discontinuation of therapies (e.g., death, tumor progression, toxicity) are not available or are incomplete in the MDV database, while others, such as some patient characteristics (e.g., ADL, BMI), can only be obtained from hospitalization records and may not be available for all patients. In addition, because diagnosis information in this database is from healthcare claims, it is possible that some claims records are left over from past diagnoses from which patients have recovered. Although information on RAS mutation status is not available in the MDV database, all patients included in this study were presumed to have RAS wild-type advanced CRC because anti-EGFR antibody therapy is only indicated for patients with this genotype [5, 42, 43]. In addition, because information that is essential for decision-making in clinical practice is incomplete in the MDV database, it is not feasible to adjust analyses for clinical characteristics or to conduct statistical comparisons of treatment outcomes between the treatment groups. Further, because the database only includes prescription information, the use of specific medications and care/monitoring concomitant therapies and procedures (e.g., proteinuria tests, antihypertensives) is inferred only, and treatment lines were defined using prespecified definitions of treatment sequences. Because a patient cannot be tracked between hospitals, patients may be lost or counted multiple times if they received treatment at more than one MDV hospital. Finally, any causal relationships between the identified factors and treatment outcome cannot be confirmed because of the small numbers of patients in some subgroups and because of the limitations of retrospective database analyses [44].

Conclusion

This is the first study to provide real-world clinical insights into second-line treatment sequences for bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept beta in patients with advanced CRC after first-line treatment with an anti-EGFR antibody. All three antiangiogenic drugs were used as second-line therapy after first-line anti-EGFR antibodies and showed similar treatment durations. This information will contribute to improved decision-making by physicians when assessing the optimal total treatment strategy for these patients.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. (Kobe, Japan), manufacturer/licensee of ramucirumab, which was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. The journal Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Serina Stretton, PhD, CMPP, and Prudence Stanford, PhD, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and the study investigation. Yoshinori Tanizawa conducted the formal analyses and prepared the figures for the study. Yoshinori Tanizawa and Long Jin were responsible for funding acquisition and project administration, Yoshinori Tanizawa, Long Jin, and Zhihong Cai were responsible for the methodology, Long Jin and Akitaka Makiyama supervised the study, and Zhihong Cai was responsible for validating the study results. The first draft was prepared by Yoshinori Tanizawa, Long Jin, and Zhihong Cai in consultation with all authors, all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Hironaga Satake has received research funding from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and honoraria from Bayer Holding Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Merck Biopharma Co., Ltd, MSD K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Sanofi K.K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.

Yoshinori Kagawa has received honoraria from Bayer Holding Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, and Merck Biopharma Co., Ltd.

Eiji Shinozaki has received honoraria from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Merck Biopharma Co., Ltd, Sanofi K.K., and Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.

Akitaka Makiyama has received honoraria from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Yoshinori Tanizawa, Long Jin, and Zhihong Cai are employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly Japan K.K.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This observational study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. Because all data in this study were from an administrative database, and were de-identified and collected retrospectively, ethical review and informed consent were not required.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data in this study were commercially obtained from Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. and were used under licence. Data can be made available from Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. upon request.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. Cancer Registry and Statistics. Vital Statistics of Japan. Page last updated July 28, 2021. https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html#mortality. Accessed 23 Nov 2021.

- 3.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the National Cancer Registry. 2016. www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000468976.pdf. Accessed 23 Nov 2021.

- 4.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Cancer Registry and Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan. Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ). Page last updated July 28, 2021. https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html#incidence4pref. Accessed 23 Nov 2021.

- 5.Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1–42. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01485-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shinozaki E, Makiyama A, Kagawa Y, et al. Treatment sequences of patients with advanced colorectal cancer and use of second-line FOLFIRI with antiangiogenic drugs in Japan: a retrospective observational study using an administrative database. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0246160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–1422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iizumi S, Takashima A, Sakamaki K, Morita S, Boku N. Survival impact of post-progression chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;81:981–989. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imai H, Kaira K, Minato K. Clinical significance of post-progression survival in lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2017;8:379–386. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrelli F, Barni S. Correlation of progression-free and post-progression survival with overall survival in advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:186–192. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vera R, Salgado M, Safont MJ, et al. Controversies in the treatment of RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23:827–839. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denda T, Sakai D, Hamaguchi T, et al. Phase II trial of aflibercept with FOLFIRI as a second-line treatment for Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1032–1043. doi: 10.1111/cas.13943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:499–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura M. Utilization of MDV data and data quality control. Jpn J Pharmacoepidemiol. 2016;21:23–25. doi: 10.3820/jjpe.21.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasunaga H, Matsui H, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Matsuda S. Clinical epidemiology and health services research using the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database in Japan. Asian Pac J Dis Manag. 2015;7:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda S, Fujimori K, Fushimi K. Development of casemix based evaluation system in Japan. Asian Pac J Dis Manag. 2010;4:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:64–67. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández-Quiles C, Bernabeu-Wittel M, Pérez-Belmonte LM, et al. Concordance of Barthel Index, ECOG-PS, and Palliative Performance Scale in the assessment of functional status in patients with advanced medical diseases. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7:300–307. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, et al. Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194–201. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin J, Cohen R, Jin Z, et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of primary tumor sidedness for previously untreated advanced colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horita Y, Yamada Y, Kato K, et al. Phase II clinical trial of second-line FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: AVASIRI trial. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:604–609. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3499–3506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JJ, Chu E. Sequencing of antiangiogenic agents in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2014;13:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parisi A, Cortellini A, Cannita K, et al. Evaluation of second-line anti-VEGF after first-line anti-EGFR based therapy in RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: the multicenter “SLAVE” study. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1259. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vera R, Mata E, González E, et al. Is aflibercept an optimal treatment for wt RAS mCRC patients after progression to first line containing anti-EGFR? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki T, Shinozaki E, Osumi H, et al. Second-line FOLFIRI plus ramucirumab with or without prior bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;84:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03855-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa H, Taniguchi H, Mitani S, et al. Efficacy of second-line bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer following first-line treatment with an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Oncology. 2017;92:205–212. doi: 10.1159/000453336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon AD, MacDonald TM. Design issues for drug epidemiology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50:419–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petri H, Urquhart J. Channeling bias in the interpretation of drug effects. Stat Med. 1991;10:577–581. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obermannová R, Van Cutsem E, Yoshino T, et al. Subgroup analysis in RAISE: a randomized, double-blind phase III study of irinotecan, folinic acid, and 5-fluorouracil (FOLFIRI) plus ramucirumab or placebo in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma progression. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2082–2089. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shitara K, Matsuo K, Yokota T, et al. Prognostic factors for metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2011;4:168–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Rooijen KL, Shi Q, Goey KKH, et al. Prognostic value of primary tumour resection in synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer: individual patient data analysis of first-line randomised trials from the ARCAD database. Eur J Cancer. 2018;91:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanemitsu Y, Shitara K, Mizusawa J, et al. Primary tumor resection plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for colorectal cancer patients with asymptomatic, synchronous unresectable metastases (JCOG1007; iPACS): a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1098–1107. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hua X, Phipps AI, Burnett-Hartman AN, et al. Timing of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among patients with colorectal cancer in relation to tumor markers and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2806–2813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modest DP, Stintzing S, von Weikersthal LF, et al. Exploring the effect of primary tumor sidedness on therapeutic efficacy across treatment lines in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of FIRE-3 (AIOKRK0306) Oncotarget. 2017;8:105749–105760. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Izzedine H, Massard C, Spano JP, Goldwasser F, Khayat D, Soria JC. VEGF signalling inhibition-induced proteinuria: mechanisms, significance and management. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafayette RA, McCall B, Li N, et al. Incidence and relevance of proteinuria in bevacizumab-treated patients: pooled analysis from randomized controlled trials. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40:75–83. doi: 10.1159/000365156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamnvik OPR, Choueiri TK, Turchin A, et al. Clinical risk factors for the development of hypertension in patients treated with inhibitors of the VEGF signaling pathway. Cancer. 2015;121:311–319. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osumi H, Shinozaki E, Ooki A, et al. Early hypertension and neutropenia are predictors of treatment efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients administered FOLFIRI and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors as second-line chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2021;10:615–625. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erbitux® (cetuximab) injection 100mg [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Merck BioPharma Co., Ltd.; 2021.

- 43.Vectibix® (panitumumab) intravenous infusion 400 mg [package insert]. Osaka, Japan: Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; 2019.

- 44.Boyko EJ. Observational research—opportunities and limitations. J Diabetes Complicat. 2013;27:642–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data in this study were commercially obtained from Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. and were used under licence. Data can be made available from Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. upon request.