Abstract

Introduction

COMBAT is a prospective, multicentre cohort study that enrolled consecutive adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis (CABM) in 69 participating centres in France between February 2013 and July 2015 and followed them for 1 year.

Methods

Patients aged at least 18 years old, hospitalised with CABM were followed during their hospitalisation and then contacted by phone 12 months after enrolment. Here we present the prevalence of sequelae at 12 months in a subgroup of patients with meningococcal meningitis.

Results

Five of the 111 patients with meningococcal meningitis died during initial hospitalisation and two died between discharge and 12 months, leaving 104 patients alive 1 year after enrolment, 71 of whom provided 12-month follow-up data. The median age was 30.0 years and 54.1% of the patients had no identified risk factor for meningitis. More than 30% reported persistent headache, more than 40% were not satisfied with their sleep and 10% had concentration difficulties. Hearing loss was present in about 15% of the patients and more than 30% had depressive symptoms. About 13% of the patients with a previous professional activity had not resumed work. On the SF-12 Health Survey, almost 50% and 30% had physical component or mental component scores lower than the 25th percentile of the score distribution in the French general population. There was a non-significant improvement in the patients’ disability scores from hospital discharge to 12 months (p = 0.16), but about 10% of the patients had residual disability.

Conclusions

Although most patients in our cohort survive meningococcal meningitis, the long-term burden is substantial and therefore it is important to ensure a prolonged follow-up of survivors and to promote preventive strategies, including vaccination.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrial.Gov identification number NCT01730690.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-022-02149-7.

Keywords: Community-acquired bacterial meningitis, France, Long-term follow-up, Meningococcal meningitis

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Little is known about the long-term sequelae in patients hospitalised with meningococcal meningitis |

| We assessed the sequelae at 12 months in a subgroup of patients from the COMBAT study who were hospitalised with meningococcal meningitis |

| Hospital and 1-year outcomes were assessed using the modified Rankin and Glasgow outcome scale scores; depressive symptoms were assessed at 12 months using the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale; hearing loss was assessed using the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly–screening version (HHIE-S); and health-related quality of life (HQRL) was assessed using the SF-12 Health Survey |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The frequency of disabilities in adult survivors of meningococcal meningitis was high with a substantial impact on patients’ quality of life |

| Although most patients survive meningococcal meningitis, the long-term burden is substantial and therefore survivors should be offered long-term follow-up |

| Preventive strategies, including vaccination, should be promoted to avoid community-acquired bacterial meningitis |

Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease is a severe infectious diseases caused by Neisseria meningitides, a Gram-negative diplococcus. Its presentation includes mainly community-acquired bacterial meningitis (CABM), and purpura fulminans (i.e. fulminant meningococcemia). Its incidence is between 0.11 and 1.76 cases/100,000 inhabitants in Europe [1]. Meningococcal CABM is a serious bacterial infection that affects the meninges and the cerebrospinal fluid and can cause severe brain damage. It is fatal in up to 50% of cases if untreated but the overall mortality rate can be as high as 10%, despite antibiotic treatment [2–4]. N. meningitidis is the second most common cause of CABM. It is carried in the nasopharynx and is transmitted from person to person through droplets of respiratory or throat secretions from carriers. The estimated carriage rate is the general population is about 10% but varies according to the age group; in infants it is 4.5% and increases to a peak of about 24% in 19-year-olds and then decreases to about 8% in 50-year-olds [5]. Meningococcal meningitis affects mainly children and young adults, but it can occur at any age [6, 7]. Although the in-hospital mortality rate for patients with meningococcal meningitis is low and its prognosis is better than that for CABM caused by other bacteria, after-effects such as brain damage, hearing loss or physical disability have been reported in 10–20% of survivors [8].

Invasive meningococcal diseases are analysed in France through a national reference centre that receives mandatory notification data, including some clinical data, from clinicians and bacterial strains from microbiologists. This epidemiological and microbiological surveillance enables disease outbreaks to be detected and evolution of the disease to be followed over time [9]. However, it is not possible to follow up the patients beyond hospitalisation or to assess long-term disability through this surveillance system. COMBAT was a prospective, multicentre cohort study of CABM in France that identified risk factors associated with death or long-term disability in adults with CABM caused by any bacteria [10]. As little is known specifically about the long-term disability of patients hospitalised with meningococcal meningitis, we performed analyses on the subgroup of patients with meningococcal meningitis in the COMBAT study to assess the prevalence of sequelae and the quality of life after 1-year follow-up.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The COMBAT study design and methods have been described elsewhere [10]. In summary, patients aged at least 18 years old and hospitalised with a CABM were enrolled between February 2013 and July 2015 in France. Clinical and microbiological data were collected prospectively during their hospital stay and the patients were subsequently contacted by telephone 12 months after enrolment. In this post hoc analysis, we included data for patients who had been diagnosed with meningococcal meningitis with or without purpura fulminans. The vital status of patients lost-to-follow-up was obtained from the French Epidemiology Centre for Medical Causes of Death (CepiDc: Centre d’épidémiologie sur les causes médicales de Décès) national database [11].

The study received ethics approval from the Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France CPP 4 (IRB 00003835) (2012-16NI), and the French Data Protection Authority (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés) (EGY/FLR/AR128794). Although the use of the CepiDc national database does not require ethics committee approval, it use for this study was approved by the ethics committee.

Objectives

The primary objective of this post hoc analysis was to describe the prevalence of sequelae in a subgroup of adults in the COMBAT study with meningococcal meningitis after 1-year follow-up. The secondary objectives were to describe the prevalence of sequelae by meningococcal serogroup (B, C, Y), and to describe the evolution of modified Rankin scores, Glasgow outcome scale scores and physical handicap from hospital discharge to the 1-year assessment.

Measurements

Risk factors for CABM were recorded. The hospital discharge and 1-year outcomes were graded using the modified Rankin scale [12, 13]. In survivors, an unfavourable outcome was defined as a score of 2 to 5 (i.e., mild to severe disability). Glasgow outcome scale scores were also assessed at discharge and at 12 months.

Depressive symptoms were assessed at 12 months using the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, and hearing loss using the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly–screening version (HHIE-S) [10]. Health-related quality of life (HQRL) was evaluated using the SF-12 Health Survey, using the derived composite physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) HRQL scores. Impaired physical or mental HRQL was defined as a PCS or MCS score lower than the 25th percentile of the score distribution in the French general population with the same age and gender [14, 15].

Statistical Methods

Categorical variables were summarized as counts (percentages) and continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). The McNemar test for paired samples was used for comparisons between data at hospital discharge and at the 12-month follow-up visit. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

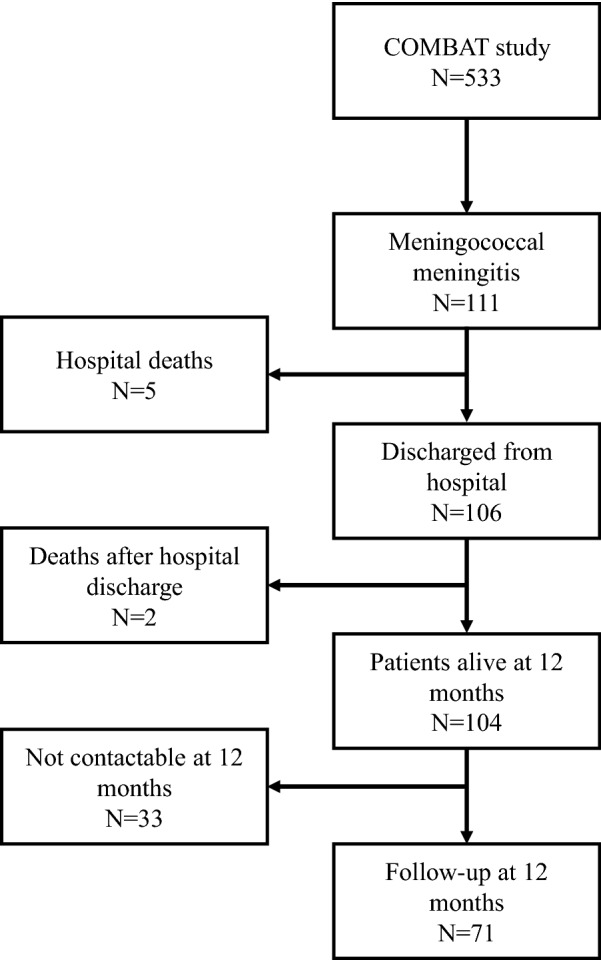

Among the 533 patients in the COMBAT study cohort, 111 were diagnosed with meningococcal meningitis (Fig. 1). The median age of these patients was 30 years [interquartile range (IQR) 21.4–56.0] (Table 1). Almost half (45.9%) had at least one risk factor for meningitis. The majority of the patients had headache and neck stiffness and had been admitted to an intensive care unit. Distribution of N. meningitidis serogroups is presented in Table 2. An in-hospital unfavourable outcome, defined as a modified Rankin score of 2–6, was reported for 19 patients, including 5 (4.5%) patients who died in hospital. Another two patients died between hospital discharge and the 12-month follow-up visit. At 12 months, 71 of the 104 patients alive at 12 months were contacted and provided information about their health.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 111 patients with meningococcal meningitis included in the COMBAT cohort

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Background characteristics | |

| Age, median [IQR] | 30.0 [21.4–56.0] |

| Male/female ratio | 1:1.2 |

| ≥ 1 risk factor for meningitis | 51/111 (45.9) |

| Alcoholism | 8/111 (7.2) |

| History of cancer (< 5 years) | 5/111 (4.5) |

| Diabetes | 4/111 (3.6) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | 1/111 (0.9) |

| Chronic renal failure | 1/110 (0.9) |

| Immunosuppressant drug use | 1/111 (0.9) |

| HIV | 6/111 (5.4) |

| Cardiac failure | 0/111 (0) |

| Splenectomy | 0/111 (0) |

| Episode of influenza-like-illness in previous 15 days | 56/108 (51.9) |

| Pre-treatment with antibiotics | 37/110 (33.6) |

| Initial clinical presentation (from symptom onset to 48 h after inclusion) | |

| Body temperature, °C (median [IQR]) | 38.2 [37.1–39.0] |

| Headache | 93/109 (85.3) |

| Neck stiffness | 75/107 (70.1) |

| Nausea | 65/108 (60.2) |

| Altered mental status | 52/111 (46.8) |

| Purpura fulminansa | 41/111 (36.9) |

| Localized neurological signs | 25/111 (22.5) |

| Seizures before hospitalisation | 3/110 (2.7) |

| Distant foci of infection (pneumoniae, arthritis, pericarditis) | 7/111 (6.3) |

| Admission to intensive care unit | 90/111 (81.1) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid findings at inclusion | |

| White cell count, cells per mm3 (median [IQR]) | 2237.5 [315–6450] |

| Protein, g/L (median [IQR]) | 4.1 [1.6–6.3] |

| Glucose mmol/L (median [IQR]) | 0.8 [0.1–2.3] |

| Smear detection | 73/107 (68.2) |

| Clinical course | |

| ≥ 1 complication | 90/111 (81.1) |

| Assisted ventilation | 33/108 (30.6) |

| Coma (Glasgow outcome scale score < 8) | 14/110 (12.7) |

| Increased fever | 13/107 (12.1) |

| Seizures | 5/110 (4.5) |

| Ventriculitis | 4/110 (3.6) |

| In-hospital outcome (modified Rankin score) | |

| Death (6) | 5/111 (4.5) |

| Major disability (5) | 2/100 (2.0) |

| Moderately severe disability (4) | 0/100 (0.0) |

| Moderate disability (3) | 4/100 (4.0) |

| Mild disability (2) | 8/100 (8.0) |

| Low disability (1) | 29/100 (29.0) |

| No disability (0) | 57/100 (57.0) |

| Unfavourable outcome (modified Rankin score of 2–6) | 19/105 (18.1) |

The data shown are n/N and percentages, unless otherwise indicated

aMeningitis was not biologically confirmed for patient who had a contraindication to lumbar puncture

Table 2.

Sequelae, modified Rankin score and Glasgow outcome scale score at 12 months in surviving patients, overall and by N. meningitidis serogroup

| Variable | All patients with follow-up at 12 months (N = 71) |

Patients with known serogroup and follow-up at 12 months (N = 69) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/C/Y (N = 69) | B (N = 36) | C (N = 27) | Y (N = 6) | ||

| Persistent headache | |||||

| Yes | 23/70 (32.9%) | 23/68 (33.8%) | 13/36 (36.1%) | 9/26 (34.6%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| MCS (SF 12) | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 50.8 [39.6–55.5] | 50.9 [40.5–55.7] | 51.3 [42.0–57.2] | 49.7 [39.6–55.0] | 53.0 [35.1–55.0] |

| PCS (SF12) | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 53.4 [44.3–55.5] | 54.1 [42.0–55.5] | 52.2 [44.2–55.0] | 53.5 [52.6–60.1] | 54.1 [42.0–55.5] |

| Difficulties to concentrate (WHOQOL-BREF) | |||||

| Not at all able to concentrate | 7/70 (10.0%) | 7/68 (10.3%) | 5/35 (14.3%) | 2/27 (7.4%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| A little to extremely well | 63/70 (90.0%) | 61/68 (89.7%) | 30/35 (85.7%) | 25/27 (92.6%) | 5/6 (83.3%) |

| Satisfied with sleep (WHOQOL-BREF) | |||||

| Dissatisfied or very dissatisfied | 30/70 (42.9%) | 29/68 (42.6%) | 15/35 (42.9%) | 13/27 (48.2%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 11/70 (15.7%) | 11/68 (16.2%) | 5/35 (14.3%) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| Satisfied or very satisfied | 29/70 (41.4%) | 28/68 (41.2%) | 15/35 (42.9%) | 9/27 (33.3%) | 4/6 (66.7%) |

| Resumed professional activity (among those working at baseline) | |||||

| Yes | 48/55 (87.3%) | 46/53 (86.8%) | 22/26 (84.6%) | 21/23 (91.3%) | 3/4 (75.0%) |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | |||||

| Yes | 24/70 (34.3%) | 22/68 (32.4%) | 12/35 (34.3%) | 9/27 (33.3%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| Hearing loss (HHI) | |||||

| Yes* | 11/71 (15.5%) | 11/69 (15.9%) | 2/36 (5.6%) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 4/6 (66.7%) |

| Modified Rankin score | |||||

| Score 0 or 1 (no or low disability) | 67/71 (94.4%) | 65/69 (94.2%) | 35/36 (97.2%) | 25/27 (92.6%) | 5/6 (83.3%) |

| Glasgow outcome scale | |||||

| Good recovery | 63/69 (91.3%) | 61/67 (91.0%) | 32/34 (94.1%) | 24/27 (88.9%) | 5/6 (83.3%) |

*Hearing loss was the only statistically significant difference between serogroups (Fisher exact test, p = 0.002)

At 12 months, 24 of the 70 patients (34.3%) with an available CES-D score had depressive symptoms (Table 2). Persistent headache was reported by 23 (32.9%) patients and hearing loss by 11 (15.5%). The PCS and MCS HRQL scores for 34/70 (48.6%) and 20/70 (28.6%) of the patients, respectively, were lower than the 25th percentile of the score distribution in the French general population but only the decrease in physical HRQL was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). These results were similar, irrespective of the serogroup, with the exception of hearing loss that was more frequent in patients with serogroup Y meningitis (p = 0.002) (Table 2).

The modified Rankin score was at least 2 for 8/69 (11.6%) of the patients at the time of hospital discharge and in 4/71 (5.6%) at 12 months (p (McNemmar) = 0.16). Similar results were observed for the Glasgow outcome scale.

Discussion

Most patients who had been hospitalised with meningococcal meningitis reported a good outcome at 12 months, but about 10% of the patients reported a poor outcome, irrespective of the serogroups. The patients in this study were young (median 30 years old) with low (4.5%) in-hospital mortality. There was a non-significant improvement in the patients’ disability scores from hospital discharge to 12 months, as measured by the modified Rankin score and the Glasgow outcome scale.

Most of the previously published studies have analysed the sequelae of invasive meningococcal infections in children and report hearing impairment, learning or concentration difficulties or mental retardation [16–27]. The few studies devoted to adults report only neurological or auditory complications, essentially from an economic perspective [28–32]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the sequelae of invasive meningococcal infections in adults and their consequences on depression and quality of life in a prospective cohort in France, although it has been evaluated retrospectively using an administrative health insurance database [8].

Our study highlights the high frequency of disabilities in adult survivors of meningococcal meningitis and the substantial impact of the disabilities on patients’ quality of life. More than 30% of the patients reported persistent headache, more than 40% sleep disturbances, 10% concentration difficulties and more than 30% depressive symptoms. Hearing loss was reported in about 15% of the patients, which is consistent with previous reports [31]. In addition, among the patients who worked prior to their meningococcal meningitis, about 13% had not resumed work at 12 months. These results could explain why the PCS HRQL score was lower than the 25th percentile of the score distribution in the French general population for almost half of the patients and the MCS HRQL score lower than the 25th percentile for almost 30% of them.

Risk factors for developing meningococcal meningitis have been identified using a case control study; however, one in two patients did not have any risk factor for meningitis in our population, making the identification of patients at risk and the prevention of this disease difficult [33]. To add to the difficulty, many patients presented with an influenza-like illness which was followed by febrile neurological symptoms due to the meningococcal meningitis, as has been previously reported [34–36]. The non-specific clinical presentation of meningococcal meningitis in some patients could have led to a delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The major strength of this study is the length of the follow-up, since previous studies have rarely reported 12-month follow-up. We were able to show that about 10% of the patients had poor disability scores even 12 months after hospital discharge and sequelae, such as hearing loss, and depression, which could compromise their ability to return to work. This emphasizes the importance of extended multidisciplinary follow-up for patients that are hospitalised for meningococcal meningitis.

We acknowledge three main limitations to this study. The first is the lack of 12-month data for 33 (32%) of the 104 surviving patients. We were able to determine that these 33 patients were alive 12 months after hospital discharge using the French CepiDc database, but we cannot extrapolate the results from those patients in this analysis to the whole population, given the differences in baseline characteristics [10]. The second is the distribution of meningococcal serogroups with 40% of serogroup C which may not be extrapolated to all countries; vaccination against serogroup C was introduced in France in 2010 and the initial vaccine strategy did not induce enough immunity to protect unvaccinated infants and adults, as has been observed in other countries [9]. Finally, as not all French hospitals participated in the study, we did not include all cases of meningococcal meningitis that occurred in France during this period. Although management and treatment of patients with meningococcal meningitis have improved and in-hospital mortality is relatively low, the important impact on patients’ health status at 1 year persists, making it is important to take preventive measures such as vaccination. This is important because, despite the introduction of meningococcal C vaccination in France in 2010 for children aged 12 months in the immunization schedule, the vaccination coverage was below 40% for those aged 10 years or older, 32% for those aged 10–14 years, 23% for those aged 15–19 years and 7% in those aged 20–24 years in 2015 [9], emphasising the need to improve efforts to increase vaccination uptake with available meningococcal vaccines.

Conclusion

Although most patients survive meningococcal meningitis, the long-term burden is substantial and therefore survivors should be offered long-term follow-up. Preventive strategies, including vaccination, should be promoted to avoid community-acquired bacterial meningitis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

COMBAT study group: Principal Investigator: Xavier Duval. Steering Committee: Bruno Hoen, Bruno Mourvillier, Marie-Cécile Ploy, Sarah Tubiana, Emmanuelle Varon. Scientific Committee: Steering committee members and François Caron, Pierre-Edouard Bollaert, Olivier Gaillot, Muhamed-Kheir Taha, Claire Poyart, Stephane Bonacorsi, François Vandenesch, Emmanuelle Cambau, Marc Lecuit, Alain Gravet, Bruno Frachet, Thomas De Broucker, Daniel Levy Bruhl, François Raffi, Marie Preau. COMBAT Clinical Centres: Nadia Anguel, Laurent Argaud, Sophie Arista, Laurence Armand-Lefevre, Stéphanie Balavoine, Régine Baraduc, Guilène Barnaud, Guillaume Beraud, Louis Bernard, Georges Bernars, Dominique Bertei, Emilie Bessede, Typhaine Billard Pomares, Charlotte Biron, Stéphane Bland, Julien Boileau, Patrice Boubeau, Sandra Bourdon, Aurore Bousquet, Sophie Boyer, Alexis Bozorg-Grayeli, Laurent Bret, Cédric Bretonniere, François Bricaire, Elsa Brocas, Michel Brun, Jennifer Buret, Christophe Burucoa, Jean Cabalion, Mathieu Cabon, Emmanuelle Cambau, Guillaume Camuset, Christophe Canevet, François Caron, Anne Carricajo, Bernard Castan, Eric Caumes, Charles Cazanave, Amélie Chabrol, Thibaut Challan-Belval, Vanessa Chanteperdrix-Marillier, Chantal Chaplain, Caroline Charlier-Woerther, Hélène Chaussade, Catherine Chirouze, Bernard Clair, Julien Colot, Jean-Marie Conil, Hugues Cordel, Philippe Cormier, Joël Cousson, Pierrick Cronier, Eric Cua, Anne Dao-Dubremetz, Sylvie Dargere, Nicolas Degand, Sophie Dekeyser, Deborah Delaune, Eric Denes, Pierre-Francois Dequin, Diane Descamps, Elodie Descloux, Jean-Luc Desmaretz, Jean-Luc Diehl, Jérôme Dimet, Aurélien Dinh, Xavier Duval, Lelia Escaut, Claude Fabe, Frédéric Faibis, Clara Flateau, Nathalie Fonsale, Emmanuel Forestier, Nicolas Fortineau, Amandine Gagneux-Brunon, Caroline Garandeau, Magali Garcia, Denis Garot, Stéphane Gaudry, François Goehringer, Alain Gravet, Valérie Gregoire-Faucher, Marine Grosset, Camélia Gubavu, Isabelle Gueit, Dominique Guelon, Thomas Guimard, Jérôme Guinard, Tahar Hadou, Jean-Pierre Helene, Sandrine Henard, Benoit Henry, Anne-Cécile Hochart, Bruno Hoen, Gabriela Illes, Sylvain Jaffuel, Irène Jarrin, Françoise Jaureguy, Cédric Joseph, Marie-Emmanuelle Juvin, Samer Kayal, Solen Kerneis, Flore Lacassin, Isabelle Lamaury, Philippe Lanotte, Etienne Laurens, Henri Laurichesse, Cécile Le Brun, Vincent Le Moing, Paul Le Turnier, Hervé Lecuyer, Sylvie Ledru, Céline Legrix, Adrien Lemaignen, Chantal Lemble, Ludovic Lemee, Olivier Lesens, Marion Levast, Claire Lhommet, Silvija Males, Edith Malpote, Guillaume Martin-Blondel, Matthieu Marx, Raphael Masson, Olivier Matray, Aurore Mbadi, Frédéric Mechai, Guillaume Mellon, Audrey Merens, Marie Caroline Meyohas, Adrien Michon, Joy Mootien Yoganaden, David Morquin, Stéphane Mouly, Natacha Mrozek, Sophie Nguyen, Yohan Nguyen, Maja Ogielska, Eric Oziol, Bernard Page, Solène Patrat-Delon, Isabelle Patry, André Pechinot, Sandrine Picot, Denys Pierrejean, Lionel Piroth, Claire Plassart, Patrice Plessis, Marie-Cécile Ploy, Laurent Portel, Patrice Poubeau, Marie Poupard, Claire Poyart, Thierry Prazuck, Luc Quaesaet, François Raffi, Adriatsiferana Ramanantsoa, Christophe Rapp, Laurent Raskine, Josette Raymond, Matthieu Revest, Agnès Riche, Stéphanie Robaday-Voisin, Frédéric Robin, Jean-Pierre Romaszko, Florence Rousseau, Anne-Laure Roux, Cécile Royer, Matthieu Saada, Dominique Salmon, Carlo Saroufim, Jean Luc Schmit, Manuela Sebire, Christine Segonds, Valérie Sivadon-Tardy, Nathalie Soismier, Olivia Son, Simon Sunder, Florence Suy, Didier Tande, Jacques Tankovic, Nadia Valin, Nicolas Van Grunderbeeck, François Vandenesch, Emmanuelle Varon, Renaud Verdon, Michel Vergnaud, Véronique Vernet-Garnier, Magali Vidal, Virginie Vitrat, Daniel Vittecoq, Fanny Vuotto. Coordination and Statistical Analyses (Clinical trial unit, Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris Nord Val de Seine, AP-HP, Paris): Isabelle Gorenne, Cédric Laouenan, Pauline Manchon, Estelle Marcault, France Mentre, Blandine Pasquet, Carine Roy, Sarah Tubiana. Scientific Partnership: SPLIF, CMIT, SRLF, SFM, REIVAC, SFORL, APNET, SPF Partners: ORP (Marie-Cécile Ploy), GPIP/ACTIV (Corinne Levy).

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the Assistance Publique Hopitaux de Paris, the French Society of Infectious Diseases, Pfizer and Sanofi. The rapid service and open access fees were funded by Sanofi.

Medical Writing Assistance

The authors would like to acknowledge medical writing and editorial services provided by Margaret Haugh, MediCom Consult, Villeurbanne, France. Support for these services and publication charges were funded by Sanofi.

Authorship

All named authors meeting the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Xavier Duval, Sarah Tubiana, and Bruno Hoen were involved in the design of the study, data analysis, critical revision of the manuscript, and validation of the final draft. Muhamed-Kheir Taha, Isabelle Lamaury, Lélia Escaut, and Isabelle Gueit were involved in the interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript, and validation of the final draft.

Disclosures

Xavier Duval reports contract work for Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris funded by Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur outside of this work. Muhamed-Kheir Taha reports contract works for the Institut Pasteur funded by GSK, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur outside of this work and reports a patent 630133 for the 4CMenB vaccine and serogroup X with GSK. Isabelle Lamaury, Lélia Escaut, Isabelle Gueit, Sarah Tubiana, and Bruno Hoen have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study received ethics approval from the Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France CPP 4 (IRB 00003835) (2012-16NI), and the French Data Protection Authority (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés) (EGY/FLR/AR128794). Although the use of the CepiDc national database does not require ethics committee approval, it use for this study was approved by the ethics committee.

Data Availability

The datasets (aggregated and anonymised), analysed for this specific analysis, are available (on reasonable request) from the corresponding author.

Footnotes

The COMBAT study group Collaborators members are listed in the Acknowledgement section.

Contributor Information

Xavier Duval, Email: xavier.duval@aphp.fr.

Muhamed-Kheir Taha, Email: muhamed-kheir.taha@pasteur.fr.

Isabelle Lamaury, Email: isabelle.lamaury@chu-guadeloupe.fr.

Lélia Escaut, Email: lelia.escaut@aphp.fr.

Isabelle Gueit, Email: isabelle.gueit@chu-rouen.fr.

Pauline Manchon, Email: pauline.manchon@aphp.fr.

Sarah Tubiana, Email: sarah.tubiana@aphp.fr.

Bruno Hoen, Email: bruno@hoen.pro.

the COMBAT study group:

Xavier Duval, Bruno Hoen, Bruno Mourvillier, Marie-Cécile Ploy, Sarah Tubiana, Emmanuelle Varon, François Caron, Pierre-Edouard Bollaert, Olivier Gaillot, Muhamed-Kheir Taha, Claire Poyart, Stephane Bonacorsi, François Vandenesch, Emmanuelle Cambau, Marc Lecuit, Alain Gravet, Bruno Frachet, Thomas De Broucker, Daniel Levy Bruhl, François Raffi, Marie Preau, Nadia Anguel, Laurent Argaud, Sophie Arista, Laurence Armand-Lefevre, Stéphanie Balavoine, Régine Baraduc, Guilène Barnaud, Guillaume Beraud, Louis Bernard, Georges Bernars, Dominique Bertei, Emilie Bessede, Typhaine Billard Pomares, Charlotte Biron, Stéphane Bland, Julien Boileau, Patrice Boubeau, Sandra Bourdon, Aurore Bousquet, Sophie Boyer, Alexis Bozorg-Grayeli, Laurent Bret, Cédric Bretonniere, François Bricaire, Elsa Brocas, Michel Brun, Jennifer Buret, Christophe Burucoa, Jean Cabalion, Mathieu Cabon, Emmanuelle Cambau, Guillaume Camuset, Christophe Canevet, François Caron, Anne Carricajo, Bernard Castan, Eric Caumes, Charles Cazanave, Amélie Chabrol, Thibaut Challan-Belval, Vanessa Chanteperdrix-Marillier, Chantal Chaplain, Caroline Charlier-Woerther, Hélène Chaussade, Catherine Chirouze, Bernard Clair, Julien Colot, Jean-Marie Conil, Hugues Cordel, Philippe Cormier, Joël Cousson, Pierrick Cronier, Eric Cua, Anne Dao-Dubremetz, Sylvie Dargere, Nicolas Degand, Sophie Dekeyser, Deborah Delaune, Eric Denes, Pierre-Francois Dequin, Diane Descamps, Elodie Descloux, Jean-Luc Desmaretz, Jean-Luc Diehl, Jérôme Dimet, Aurélien Dinh Xavier Duval, Lelia Escaut, Claude Fabe, Frédéric Faibis, Clara Flateau, Nathalie Fonsale, Emmanuel Forestier, Nicolas Fortineau, Amandine Gagneux-Brunon, Caroline Garandeau, Magali Garcia, Denis Garot, Stéphane Gaudry, François Goehringer, Alain Gravet, Valérie Gregoire-Faucher, Marine Grosset, Camélia Gubavu, Isabelle Gueit, Dominique Guelon, Thomas Guimard, Jérôme Guinard, Tahar Hadou, Jean-Pierre Helene, Sandrine Henard, Benoit Henry, Anne-Cécile Hochart, Bruno Hoen, Gabriela Illes, Sylvain Jaffuel, Irène Jarrin, Françoise Jaureguy, Cédric Joseph, Marie-Emmanuelle Juvin, Samer Kayal, Solen Kerneis, Flore Lacassin, Isabelle Lamaury, Philippe Lanotte, Etienne Laurens, Henri Laurichesse, Cécile Le Brun, Vincent Le Moing, Paul Le Turnier, Hervé Lecuyer, Sylvie Ledru, Céline Legrix, Adrien Lemaignen, Chantal Lemble, Ludovic Lemee, Olivier Lesens, Marion Levast, Claire Lhommet, Silvija Males, Edith Malpote, Guillaume Martin-Blondel, Matthieu Marx, Raphael Masson, Olivier Matray, Aurore Mbadi, Frédéric Mechai, Guillaume Mellon, Audrey Merens, Marie Caroline Meyohas, Adrien Michon, Joy Mootien Yoganaden, David Morquin, Stéphane Mouly, Natacha Mrozek, Sophie Nguyen, Yohan Nguyen, Maja Ogielska, Eric Oziol, Bernard Page, Solène Patrat-Delon, Isabelle Patry, André Pechinot, Sandrine Picot, Denys Pierrejean, Lionel Piroth, Claire Plassart, Patrice Plessis, Marie-Cécile Ploy, Laurent Portel, Patrice Poubeau, Marie Poupard, Claire Poyart, Thierry Prazuck, Luc Quaesaet, François Raffi, Adriatsiferana Ramanantsoa, Christophe Rapp, Laurent Raskine, Josette Raymond, Matthieu Revest, Agnès Riche, Stéphanie Robaday-Voisin, Frédéric Robin, Jean-Pierre Romaszko, Florence Rousseau, Anne-Laure Roux, Cécile Royer, Matthieu Saada, Dominique Salmon, Carlo Saroufim, Jean Luc Schmit, Manuela Sebire, Christine Segonds, Valérie Sivadon-Tardy, Nathalie Soismier, Olivia Son, Simon Sunder, Florence Suy, Didier Tande, Jacques Tankovic, Nadia Valin, Nicolas Van Grunderbeeck, François Vandenesch, Emmanuelle Varon, Renaud Verdon, Michel Vergnaud, Véronique Vernet-Garnier, Magali Vidal, Virginie Vitrat, Daniel Vittecoq, Fanny Vuotto, Isabelle Gorenne, Cédric Laouenan, Pauline Manchon, Estelle Marcault, France Mentre, Blandine Pasquet, Carine Roy, and Sarah Tubiana

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of invasive bacterial diseases in Europe, 2012. 2015. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-invasive-bacterial-diseases-europe-2012. Accessed 3 Dec 2021.

- 2.Bijlsma MW, Brouwer MC, Kasanmoentalib ES, et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults in the Netherlands, 2006–14: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(3):467–492. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00070-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Epidemiology of community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31(1):78–84. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen H, May M, Bowen L, Hickman M, Trotter CL. Meningococcal carriage by age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):853–861. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, et al. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(Rr-2):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Meningococcal meningitis. 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningococcal-meningitis. Accessed 26 May 2021.

- 8.Weil-Olivier C, Taha MK, Emery C, et al. Healthcare resource consumption and cost of invasive meningococcal disease in France: a study of the national health insurance Database. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(3):1607–1623. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00468-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parent-du-Chatelet I, Deghmane AE, Antona D, et al. Characteristics and changes in invasive meningococcal disease epidemiology in France, 2006–2015. J Infect. 2017;74(6):564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tubiana S, Varon E, Biron C, et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults: in-hospital prognosis, long-term disability and determinants of outcome in a multicentre prospective cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(9):1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.INSERM CepiDc. [The CepiDc]. 2016. https://www.cepidc.inserm.fr/qui-sommes-nous/le-cepidc. Accessed 26 May 2021.

- 12.Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60: II. prognosis. Scott Med J. 1957;2(5):200–215. doi: 10.1177/003693305700200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: implications for stroke clinical trials. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1091–1096. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrieri P, Spire B, Duran S, et al. Health-related quality of life after 1 year of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(1):38–47. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200301010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the SF-36 in eleven countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bargui F, D’Agostino I, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, et al. Factors influencing neurological outcome of children with bacterial meningitis at the emergency department. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(9):1365–1371. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1733-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borg J, Christie D, Coen PG, Booy R, Viner RM. Outcomes of meningococcal disease in adolescence: prospective, matched-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e502–e509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briand C, Levy C, Baumie F, et al. Outcomes of bacterial meningitis in children. Med Mal Infect. 2016;46(4):177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buysse CM, Oranje AP, Zuidema E, et al. Long-term skin scarring and orthopaedic sequelae in survivors of meningococcal septic shock. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(5):381–386. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.131862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse CM, Raat H, Hazelzet JA, Hop WC, Maliepaard M, Joosten KF. Surviving meningococcal septic shock: health consequences and quality of life in children and their parents up to 2 years after pediatric intensive care unit discharge. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(2):596–602. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000299740.65484.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse CM, Vermunt LC, Raat H, et al. Surviving meningococcal septic shock in childhood: long-term overall outcome and the effect on health-related quality of life. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R124. doi: 10.1186/cc9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng L, Barton B, Lorenzo J, Rashid H, Dastouri F, Booy R. Longer term outcomes following serogroup B invasive meningococcal disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57:894–902. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fellick JM, Sills JA, Marzouk O, Hart CA, Cooke RW, Thomson AP. Neurodevelopmental outcome in meningococcal disease: a case-control study. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(1):6–11. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottfredsson M, Reynisson IK, Ingvarsson RF, et al. Comparative long-term adverse effects elicited by invasive group B and C meningococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):e117–e124. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pace D, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal disease: clinical presentation and sequelae. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 2):B3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein-Zamir C, Shoob H, Sokolov I, Kunbar A, Abramson N, Zimmerman D. The clinical features and long-term sequelae of invasive meningococcal disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(7):777–779. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Beek D, Schmand B, de Gans J, et al. Cognitive impairment in adults with good recovery after bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(7):1047–1052. doi: 10.1086/344229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edge C, Waight P, Ribeiro S, Borrow R, Ramsay M, Ladhani S. Clinical diagnoses and outcomes of 4619 hospitalised cases of laboratory-confirmed invasive meningococcal disease in England: linkage analysis of multiple national databases. J Infect. 2016;73(5):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustafsson N, Stallknecht SE, Skovdal M, Poulsen PB, Østergaard L. Societal costs due to meningococcal disease: a national registry-based study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:563–572. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S175835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heckenberg SGB, de Gans J, Brouwer MC, et al. Clinical features, outcome, and meningococcal genotype in 258 adults with meningococcal meningitis: a prospective cohort study. Med (Baltim) 2008;87(4):185–192. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318180a6b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L, Heuer OD, Janßen S, Häckl D, Schmedt N. Clinical and economic burden of invasive meningococcal disease: evidence from a large German claims database. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0228020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loenenbach AD, van der Ende A, de Melker HE, Sanders EAM, Knol MJ. The clinical picture and severity of invasive meningococcal disease serogroup W compared with other serogroups in the Netherlands, 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(10):2036–2044. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taha M-K, Weil-Olivier C, Bouée S, et al. Risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease: a retrospective analysis of the French national public health insurance database. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(6):1858–1866. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1849518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anon G. Bacterial meningitis after influenza. Lancet. 1982;1(8275):804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison LH, Armstrong CW, Jenkins SR, et al. A cluster of meningococcal disease on a school bus following epidemic influenza. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(5):1005–1009. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400050141028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs JH, Viboud C, Tchetgen ET, et al. The association of meningococcal disease with influenza in the United States, 1989–2009. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e107486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets (aggregated and anonymised), analysed for this specific analysis, are available (on reasonable request) from the corresponding author.