Abstract

A rapid and sensitive assay was developed for detection of small numbers of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli cells in environmental water, sewage, and food samples. Water and sewage samples were filtered, and the filters were enriched overnight in a nonselective medium. The enrichment cultures were prepared for PCR by a rapid and simple procedure consisting of centrifugation, proteinase K treatment, and boiling. A seminested PCR based on specific amplification of the intergenic sequence between the two Campylobacter flagellin genes, flaA and flaB, was performed, and the PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. The assay allowed us to detect 3 to 15 CFU of C. jejuni per 100 ml in water samples containing a background flora consisting of up to 8,700 heterotrophic organisms per ml and 10,000 CFU of coliform bacteria per 100 ml. Dilution of the enriched cultures 1:10 with sterile broth prior to the PCR was sometimes necessary to obtain positive results. The assay was also conducted with food samples analyzed with or without overnight enrichment. As few as ≤3 CFU per g of food could be detected with samples subjected to overnight enrichment, while variable results were obtained for samples analyzed without prior enrichment. This rapid and sensitive nested PCR assay provides a useful tool for specific detection of C. jejuni or C. coli in drinking water, as well as environmental water, sewage, and food samples containing high levels of background organisms.

Campylobacter jejuni was isolated from human stools for the first time in 1972 (11). Since then, the development of selective stool culture media has revealed that thermophilic Campylobacter species, particularly C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli, are common causes of diarrhea in most parts of the world (2). It is estimated that in the United States, Campylobacter strains cause more than two million cases of diarrhea annually, which is similar to the number of cases of Salmonella enteritis (49).

The natural habitats of most Campylobacter species are the intestines of birds and other warm-blooded animals, including seagulls and several other wild birds (22). In most cases the host is a carrier that does not exhibit symptoms, but it may have acquired immunity through an earlier Campylobacter infection (41). Campylobacter cells may enter the environment, including drinking water, through the feces of animals, birds, or infected humans. These organisms are not able to grow but may survive in the environment for several weeks at temperatures around 4°C (8, 9). Different kinds of poultry, especially broiler chickens, are some of the most important sources of Campylobacter infection in humans, and the water supply has been shown to be a prominent factor in colonization of chickens on broiler farms (23, 42). In addition, contaminated drinking water has been the cause of several large outbreaks of campylobacter enteritis (9, 51). Eleven of 57 reported outbreaks of Campylobacter infection in the United States between 1978 and 1986 were waterborne (53), and all of these outbreaks were related to drinking unboiled surface water, contamination of groundwater with surface water, inadequate disinfection, or contamination by avian wildlife feces.

The infective dose of Campylobacter cells is very small; it has been estimated that ca. 500 cells of C. jejuni can cause human illness (7, 44). This means that even very small numbers of Campylobacter cells in water or food may be a potential health hazard. Moreover, the presence of Campylobacter cells is not correlated with the level of microorganisms that are indicators of fecal contamination of water (10). Thus, sensitive methods are needed to detect Campylobacter cells in environmental and drinking water sources.

There are several problems concerning detection of Campylobacter cells in water, including the small numbers and slow growth rates of the organisms. The traditional methods currently used are time-consuming and laborious, requiring prolonged incubation, selective enrichment to reduce the growth of the background flora, and biochemical identification. Campylobacter cells may also enter a viable but nonculturable state due to starvation and physical stress, which may explain the failure of the culture techniques to isolate the organisms from contaminated water samples implicated in outbreaks of infection (21, 45).

The PCR is an extensively used genetic approach for detecting infectious agents (13, 50), and a number of PCR assays for detecting Campylobacter cells have been developed during the past few years. These assays have been used to detect Campylobacter cells in poultry (12, 15–17, 29, 31, 61), feces (28, 37, 39, 43, 57), dairy products (1, 12, 20, 60), sewage (27), and water (18, 20, 26, 38).

In this paper, we describe a nonselective enrichment procedure followed by a rapid and simple DNA preparation step and a seminested PCR assay for detection of C. jejuni and C. coli in water and food samples. We found that the seminested PCR assay, which was described previously by Wegmüller et al. (60), specifically amplifies the intragenic flaA-flaB sequence from C. jejuni and C. coli. The sensitivity of the procedure was determined by using artificially seeded water and sewage samples collected from natural sources with different background floras. Artificially contaminated meat samples were also analyzed by the PCR assay with and without prior enrichment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 41 Campylobacter strains and 20 strains belonging to other bacterial genera were included in this study (Table 1). C. jejuni NIPH 3218/94 (biotype 1) was used for sensitivity tests and for inoculating water and food samples. This strain was originally isolated from a human patient with acute gastroenteritis.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains examined

| Microorganism | Sourcea | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|

| Actinomyces pyogenes | NCVM | 1 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | NCVM | 1 |

| Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida | NCVM | 1 |

| Campylobacter coli | NIPH | 9 |

| Campylobacter coli | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter concisus | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter fetus subsp. venerealis | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter jejuni biotype 1 | NIPH | 6 |

| Campylobacter jejuni biotype 1 | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter jejuni biotype 2 | NIPH | 5 |

| Campylobacter lari | NIPH | 9 |

| Campylobacter lari | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter mucosalis | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter sputorum biovar bubulus | CCUG | 2 |

| Campylobacter sputorum biovar fecalis | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter sputorum biovar sputorum | CCUG | 1 |

| Campylobacter upsaliensis | CCUG | 1 |

| Citrobacter sp. | NCVM | 1 |

| Citrobacter freundii | NIPH | 1 |

| Clostridium perfringens | NCVM | 1 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | NCVM | 1 |

| Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | NCVM | 1 |

| Escherichia coli | NCVM | 1 |

| Escherichia coli | NIPH | 1 |

| Klebsiella sp. | NCVM | 1 |

| Proteus sp. | NCVM | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NCVM | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NIPH | 1 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | NIPH | 1 |

| Rhodococcus equi | NCVM | 1 |

| Salmonella saintpaul | NIPH | 1 |

| Vibrio anguillarum | NCVM | 1 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | NIPH | 1 |

| Yersinia intermedia | NIPH | 1 |

NCVM, Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine, Oslo, Norway; NIPH, Salmonella Reference Laboratory, National Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway; CCUG, Culture Collection, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden.

Cultivation and enumeration of bacteria.

Campylobacter strains were grown in stationary cultures in 5 ml of Rosef broth without antibiotics (46) for 24 or 48 h in a microaerobic atmosphere created by using BBL GasPak Plus anaerobic system envelopes without the palladium catalyst (Becton Dickinson and Co., Cockeysville, Md.). Rosef broth contains (per liter) 10 g of peptone (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, England), 8 g of LabLemco (Oxoid), 1 g of yeast extract powder (Oxoid), 5 g of sodium chloride, and 1.6 ml of a rezasurin solution (0.025%, wt/vol). Most strains were cultivated at 42°C; the exceptions were the Campylobacter concisus, Campylobacter fetus subsp. veneralis, Campylobacter mucosalis, and Campylobacter sputorum biovar fecalis strains, which were cultivated at 37°C. Non-Campylobacter strains were cultivated on a roller drum in 5 ml of tryptic soy broth containing 0.6% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Aeromonas, Yersinia, and Vibrio anguillarum strains were cultivated in tryptic soy broth containing 0.6% yeast extract at room temperature, while strains of the other species were grown at 37°C. Clostridium perfringens was grown in a stationary culture in an anaerobic atmosphere. The bacteria used to examine primer specificity were grown as described above and subsequently diluted in sterile Rosef broth (Campylobacter strains) or sterile saline (strains of other species) to concentrations of 106 to 108 CFU per ml, roughly determined by measuring optical density at 650 nm (optical density at 650 nm, 0.05 to 0.1). Portions (100 μl) of each dilution were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and boiled for 10 to 15 min to lyse the bacteria, and 1 to 2 μl of each lysate was examined by the PCR.

C. jejuni NIPH 3218/94, which was used to spike water and food samples and to determine the sensitivity of the nested PCR assay, was grown in Rosef broth overnight and diluted to a concentration of approximately 108 CFU per ml as described above (optical density at 650 nm, 0.1). Appropriate bacterial concentrations were obtained by preparing serial 10-fold dilutions in Rosef broth. To enumerate the bacteria, 80-μl aliquots were spread onto four horse blood agar plates (which had been dried for 45 to 60 min at 37°C to prevent bacterial swarming) and incubated at 42°C for 48 h. The bacterial concentration was estimated by calculating the average colony count for the four agar plates.

Water and sewage samples.

A sewage sample was collected at the Bekkelaget sewage treatment plant in Oslo, Norway, while water samples were collected from the following eight sources (Table 2): Lake Maridalsvannet, the drinking water supply for Oslo (Oset water treatment plant; raw water collected at a depth of 36 m) (site a); the Akerselva River, which runs from the water supply (four locations downstream with different levels of fecal contamination) (sites b through e); Nilserudkleiva Stream, which is a small brook with a high level of fecal contamination (site f); Sognsvannsbekken Stream, a medium-sized stream with some fecal contamination (site g); and a small pond in Enebakk County outside Oslo, which contains water that has a high level of humus but a low level of fecal contamination (site h). The samples were collected in sterile 1-liter bottles, transported to the laboratory at the ambient temperature, and stored at 4°C before they were analyzed within 24 h. Samples were collected, total and fecal coliform bacteria were enumerated by the most-probable-number method, and heterotrophic organisms were enumerated by the plate count procedure by using Norwegian national standards (Table 2) (34–36).

TABLE 2.

Results of nested PCR performed with spiked water and sewage samples

| Sample | Water sourceb | No. of hetero-trophic organisms (CFU/ml) | No. of total coliform bacteria (CFU/100 ml) | No. of thermo-tolerant coli-form bacteria (CFU/100 ml) | No. of Campylo-bacter cells added (CFU/100 ml) | PCR results

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiked aliquotsc

|

Unspiked aliquots

|

||||||||

| Undiluted broth | Broth diluted 1:10d | Undiluted broth | Broth diluted 1:10d | ||||||

| 1 | Oset water treatment plant (site a) | 39 | 2 | 2 | 4.4 | +,+ | +,+ | − | − |

| 44 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 2 | Akerselva River (site b) | 300 | 60 | 47 | 13 | +,+ | +,+ | − | − |

| 126 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 3 | Pond in Enebakk County (site h) | 210 | 2 | <2 | 3 | +,+ | +,+ | − | − |

| 30 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 4a | Akerselva River (site c) | 2,700 | 1,300 | 1,800 | 2.5 | +,− | −,− | − | − |

| 25 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 5a | Akerselva River (site c) | 2,000 | 10,000 | 75 | 7 | +,+ | −,− | − | − |

| 66 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 6 | Akerselva River (site c) | 1,200 | 5,000 | 2,000 | 4.4 | +,+ | +,+ | + | − |

| 44 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 7a | Akerselva River (site d) | 2,800 | 1,400 | 150 | 2.5 | +,(+)e | +,− | (+) | − |

| 25 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 8a | Akerselva River (site e) | 3,300 | 2,700 | 120 | 7 | −,+ | −,− | − | − |

| 66 | +,− | −,+ | |||||||

| 9 | Sognsvannsbekken Stream (site g) | 2,500 | 800 | 240 | 15 | +,+ | +,+ | + | + |

| 150 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 10 | Nilserudkleiva Stream (site f) | 8,700 | 2,400 | 1,900 | 15 | −,+ | +,+ | − | − |

| 150 | +,+ | +,+ | |||||||

| 11 | Bekkelaget sewage treatment plant | 49,000 | 160,000 | 40,000 | 13 | +,+ | +,+ | + | + |

| 126 | +,+ | +,− | |||||||

Samples were analyzed with a primer concentration of 0.25 μM during both PCR steps. For the remaining samples, primer concentrations of 0.2 and 0.25 μM were used for the first and second PCR steps, respectively.

The locations from which the samples were collected are shown in parentheses.

For each dilution, the results obtained for two parallel aliquots are shown.

Enriched broth was diluted 1:10 with sterile Rosef broth prior to PCR.

Results in parentheses were difficult to interpret (see text).

Food samples.

Seven food samples, including samples of minced beef, chicken, and pork, were purchased from local stores, transported to the laboratory at the ambient temperature, and kept frozen at −20°C (Table 3). Before examination, they were thawed overnight at 4°C. Standard plate count procedures were used to enumerate total and fecal coliform bacteria and to determine total aerobic organism counts (32, 33).

TABLE 3.

Food samples examined

| Sample | Food type | Plate counts (CFU/g)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Coliform bacteria | Thermotolerant coliform bacteria | ||

| 1 | Minced beef | 5.9 × 107 | 3.3 × 104 | <10 |

| 2 | Minced beef | 3.2 × 106 | 2.8 × 105 | <10 |

| 3 | Minced beef | 3.0 × 107 | 4.1 × 104 | <10 |

| 4 | Minced beef | 6.3 × 106 | 4.7 × 102 | <10 |

| 5 | Chicken | 2.8 × 107 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.5 × 102 |

| 6 | Spiced, marinated chicken | NDa | ND | ND |

| 7 | Pork | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not done.

Preparation of water and sewage samples prior to PCR.

Four 100-ml aliquots of each sample were spiked with C. jejuni and filtered through 47-mm-diameter, 0.45-μm-pore-size standard membrane filters (Gelman Sciences Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich.) by using a vacuum pump (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.). Two aliquots were seeded with approximately 102 campylobacter cells, and two aliquots were seeded with approximately 10 campylobacter cells. As a negative control, a nonspiked 100-ml aliquot was processed by the procedure used for the spiked aliquots. The filters were transferred to petri dishes containing 10 ml of Rosef broth and were incubated in a microaerobic atmosphere at 37°C for 4 h and then at 42°C for approximately 14 h. The following sample preparation procedures were performed by using the method described by Kapperud et al. (24), with a few modifications. From each overnight culture, 100 μl of undiluted broth and 100 μl of broth diluted 1:10 with sterile Rosef broth were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 10 min. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of PCR buffer (see below) containing 0.2 mg of proteinase K per ml. After incubation at 37 to 50°C for 1 h, the bacteria were lysed by boiling the preparations for 10 min. The samples were then stored at −20°C prior to the PCR. After each preparation was thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 5 min, PCR reagents were added to 50 μl of the supernatant so that the final volume was 100 μl, and a seminested PCR was performed as described below.

Preparation of food samples prior to PCR.

Food samples were prepared by using the method described by Kapperud et al. (24), with a few modifications. The analysis was performed with and without overnight enrichment. Three 25-g aliquots of each food sample were spiked with C. jejuni. Two of these aliquots were analyzed after a short sedimentation procedure, while the third aliquot was subjected to overnight enrichment.

(i) Analysis without enrichment.

Two 25-g aliquots of each sample were mixed 1:10 with Rosef broth in a Colworth 80 stomacher for 1 min. One of the mixtures was then spiked with approximately 102 campylobacter cells per g of food, and the other was spiked with approximately 10 campylobacter cells per g of food, and then the mixtures were sedimented passively for 45 to 60 min at 4°C to remove the coarse particles and solidified fat. Two 1-ml aliquots of the dilution containing 102 campylobacter cells per g of food and two 100-μl aliquots of the same dilution were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 10 min. Two 1-ml aliquots of the supernatant from the dilution containing 10 campylobacter cells per g were removed and treated in the same way. The pellets were resuspended in PCR buffer containing proteinase K, boiled, and prepared for PCR analysis as described above for the water and sewage samples.

(ii) Analysis with overnight enrichment.

One 25-g aliquot was mixed 1:10 with Rosef broth in a stomacher for 1 min and inoculated with approximately 1 CFU of C. jejuni per g of food. The mixture was incubated in a microaerobic atmosphere at 37°C for 4 h and then for an additional 14 h at 42°C. To remove the coarse particles and solidified fat, the mixture was sedimented passively at 4°C for 45 to 60 min. Two 100-μl aliquots of undiluted supernatant and one 100-μl aliquot of supernatant diluted 1:10 with sterile Rosef broth were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 10 min. Additional preparation procedures and a seminested PCR were performed as described above. As for the water and sewage samples, unspiked food samples were always included as negative controls.

Selection and synthesis of primers.

Oligonucleotide primers CF02, CF03, and CF04 (60) from the C. jejuni flaA and flaB sequences were used in the seminested PCR assay. The sequences of the primers were as follows: CF03, 5′-GCT CAA AGT GGT TCT TAT GCN ATG G-3′; CF04, 5′-GCT GCG GAG TTC ATT CTA AGA CC-3′; and CF02, 5′-AAG CAA GAA GTG TTC CAA GTT T-3′. The first PCR step, performed with primers CF03 and CF04, amplified a fragment having an estimated size of 340 to 380 bp, while the size of the final PCR product obtained with primers CF03 and CF02 was 180 to 220 bp. The primers were synthesized by Kebo Lab (Stockholm, Sweden) or DNA Technology ApS (Aarhus, Denmark) with automatic DNA synthesizers.

Seminested PCR.

The PCR was carried out by performing three kinds of experiments. First, boiled cultures of strains of Campylobacter species and other bacterial species were amplified to test the specificity of the PCR primers. Second, the sensitivity of the seminested PCR assay was determined by amplifying a serially diluted culture of C. jejuni. And finally, the sensitivity for detecting Campylobacter cells in spiked water, sewage, or food samples was determined as described above. PCR amplification of the target sequence was performed with a GeneAmp kit with Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Foster City, Calif.) and a DNA thermal cycler (model 480; Perkin-Elmer). The reaction mixtures used for both PCR steps contained 1× PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 4.0 mM MgCl2, 0.001% [wt/vol] gelatin), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, each primer at a concentration of 0.25 μM, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase per 50 μl of reaction mixture. Each reaction mixture was overlaid with 2 drops of mineral oil. The first PCR step was performed by using a total volume of 50 μl for the sensitivity and specificity assays and a total volume of 100 μl for examining water and food samples. The following conditions were used: heat denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 40 cycles consisting of heat denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, primer annealing at 53°C for 30 s, and DNA extension at 72°C for 40 s. After the last cycle, the samples were kept at 72°C for 10 min to complete synthesis of all strands. The second PCR step was performed by using a total volume of 50 μl. A 1-μl aliquot of the first PCR product was used as the template. The cycle profile consisted of the same heat denaturation, primer annealing, and DNA extension conditions as those used for the first PCR step, but the number of cycles was reduced to 20.

Electrophoretic detection of PCR products.

PCR products were visualized by gel electrophoresis. Samples (10 μl) of final PCR products were loaded onto a 1.0% agarose gel and subjected to electrophoresis in 1× TBE buffer (47) for 1 to 2 h at 120 V. When more accurate determinations of the sizes of PCR products were desired, a 2.0% MetaPhor agarose gel (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) was used, and electrophoresis was performed for 4 h at 100 V. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light transillumination. A 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Ghent, Belgium) was included on each gel as a molecular size standard.

RESULTS

Specificity of PCR primers.

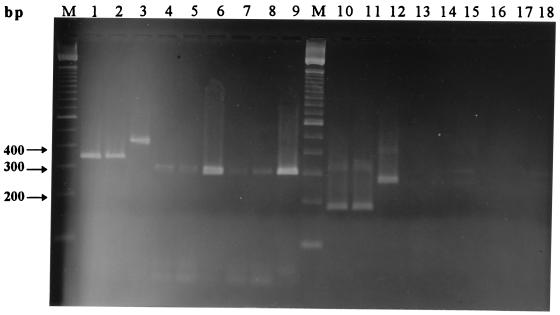

Amplification of DNA from all 12 C. jejuni strains examined and all 10 C. coli strains examined (Table 1) resulted in fragments of the predicted sizes, 340 to 380 bp in the first PCR step and 180 to 220 bp in the second PCR step (Fig. 1, lanes 1, 2, 10, and 11).

FIG. 1.

Gel electrophoresis patterns of PCR products obtained by examination of lysed bacterial cultures by seminested PCR. Lanes 1 through 9 and 10 through 18 show the results obtained after the first PCR step and the second PCR step, respectively. Lanes 1 and 10, C. jejuni NIPH 3218/94; lanes 2 and 11, C. coli NIPH 1505/94; lanes 3 and 12, C. lari NIPH 834/94; lanes 4 and 13, C. lari NIPH 4219/92; lanes 5 and 14, C. lari NIPH 268/94; lanes 6 and 15, C. lari NIPH 1054/94; lanes 7 and 16, C. lari NIPH 1089/94; lanes 8 and 17, C. lari NIPH 2138/94; lanes 9 and 18, C. lari CCUG 10773. Lanes M contained the 100-bp DNA ladder.

Amplification of DNA from 7 of the 10 strains of Campylobacter lari tested resulted in detectable products during first PCR step. Six of these strains produced a band at ca. 300 bp (Fig. 1, lanes 4 through 9) but failed to generate any product during the second round of PCR (Fig. 1, lanes 13 through 18). The seventh C. lari strain produced a band at ca. 450 bp, which was further amplified to a ca. 280-bp product during the second PCR step (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 12). The three remaining C. lari strains were negative in both PCR steps.

Amplification of DNA from nine strains belonging to eight additional Campylobacter species, including Campylobacter upsaliensis, did not result in any PCR products in the size range of the products generated by C. jejuni, C. coli, or C. lari, although some strains produced nonspecific fragments. These amplicons were much larger than the PCR products expected for C. jejuni or C. coli.

Seminested amplification of DNA from 20 strains belonging to other bacterial genera produced a number of nonspecific products when a primer concentration of 0.25 μM was used during the first PCR step. Some of these products were within or close to the size range for Campylobacter PCR products, making differentiation based on product length difficult. Reducing the primer concentration to 0.2 μM during the first PCR step decreased this problem to a minimum and did not influence the sensitivity of the assay. Nonspecific products having lengths similar to those of products obtained from Campylobacter strains were eliminated, and the remaining nonspecific products were easily distinguished from C. jejuni and C. coli amplicons on the gels.

Sensitivity of seminested PCR with pure cultures.

To determine the minimum number of Campylobacter cells that could be amplified, serial dilutions of boiled lysates containing known numbers of bacterial cells were examined. As few as 3 CFU of C. jejuni NIPH 3218/94 could be detected with ethidium bromide-stained gels, independent of whether a primer concentration of 0.25 or 0.2 μM was used during the first PCR step (results not shown).

Examination of spiked water and sewage samples.

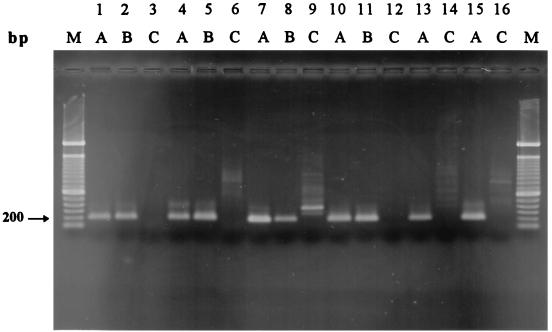

A total of 10 surface water samples from eight sources and one sewage sample were examined. Four 100-ml aliquots of each sample were inoculated with C. jejuni, filtered, enriched in Rosef broth overnight, and prepared for PCR with and without further dilution. Table 2 shows the PCR results obtained for the various samples, and Fig. 2 shows the results obtained for samples 1, 3, 4, and 10 after analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis. The unspiked sample 7 aliquot produced a faint band that was slightly larger than the product produced by C. jejuni NIPH 3218/94, and this band was most likely a result of nonspecific amplification of DNA from background organisms. However, the size difference was too small to rule out the possibility that the product was a result of amplification of naturally contaminating Campylobacter cells, and consequently, sample 7 was excluded from the sensitivity evaluation. Samples 6, 9, and 11 were also excluded due to the clearly positive results obtained with the unspiked control aliquots. No attempts were made to isolate Campylobacter cells from these samples by traditional culturing methods. The results obtained for the remaining seven samples showed that the seminested PCR assay was capable of detecting 3 to 15 Campylobacter CFU per 100 ml of water when the background flora contained up to 8,700 heterotrophic organisms per ml and 10,000 CFU of coliform bacteria per 100 ml. Two aliquots spiked with 2.5 and 7 CFU per 100 ml gave negative results when both undiluted and diluted broth preparations were analyzed (samples 4 and 8). However, parallel aliquots obtained from samples 4 and 8 gave positive results when undiluted broth preparations were analyzed, while the diluted broth preparations were negative.

FIG. 2.

Gel electrophoresis patterns of PCR products obtained by examination of spiked water and food products by seminested PCR. Lanes 1 through 12 show the results for the following water samples (Table 2): sample 1 spiked with 4.4 CFU per 100 ml (lanes 1 through 3), sample 3 spiked with 3 CFU per 100 ml (lanes 4 through 6), sample 4 spiked with 2.5 CFU per 100 ml (lanes 7 through 9), and sample 10 spiked with 15 CFU per 100 ml (lanes 10 through 12). Lanes 13 through 16 show the results for the following food samples (Table 4): sample 4 spiked with <1 CFU per g (lanes 13 and 14) and sample 6 spiked with 0.5 CFU per g (lanes 15 and 16). Lanes A contained undiluted broth media, lanes B contained broth media diluted 1:10, and lanes C contained unspiked aliquots. Lanes M contained the 100-bp DNA ladder.

Examination of spiked food samples.

A total of seven food samples were homogenized, spiked with C. jejuni, and examined with and without overnight enrichment. Table 4 shows the results obtained for the various samples.

TABLE 4.

Results of nested PCR performed with spiked food samples with and without enrichment

| Sample | Food sample | No. of Campylo-bacter cells added (CFU/g) | PCR resultsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiked aliquots without enrichment at zero time

|

Spiked aliquots with enrichment on day 1

|

Unspiked aliquot with enrichment on day 1 (100 μl of undiluted broth)

|

|||||

| Analysis of 1 mlb | Analysis of 100 μlb | 100 μl of undiluted brothb | 100 μl of broth diluted 1:10c | ||||

| 1 | Minced beef | 78 | +,+ | +,+ | NDd | ND | − |

| 8 | +,+ | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 0.5 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 2 | Minced beef | 130 | +,+ | +,+ | ND | ND | − |

| 13 | +,+ | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 1 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 3 | Minced beef | >500 | +,+ | +,+ | ND | ND | − |

| >50 | −,− | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 3 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 4 | Minced beef | 120 | +,+ | +,− | ND | ND | − |

| 12 | +,− | ND | ND | ND | |||

| <1 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 5 | Chicken | 130 | +,(+)e | +,− | ND | ND | (+) |

| 13 | +,(+) | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 1 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 6 | Spiced chicken | 80 | (+),− | +,− | ND | ND | − |

| 8 | −,− | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 0.5 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

| 7 | Pork | 180 | +,− | −,− | ND | ND | − |

| 18 | −,− | ND | ND | ND | |||

| 1 | ND | ND | +,+ | + | |||

PCR were performed with 0.25 μM primer during both PCR steps.

For each dilution, the results obtained for two parallel aliquots are shown.

Enriched broth was diluted 1:10 with sterile Rosef broth prior to PCR.

ND, not done.

Results in parentheses were difficult to interpret (see text).

(i) Analysis without enrichment.

The results obtained for samples analyzed without enrichment varied. Positive results were obtained for all minced beef samples inoculated with ≥78 CFU per g when 1 ml of broth was analyzed. When 100-μl portions of broth from these samples were analyzed, positive results were obtained in most cases; the only exception was one aliquot spiked with 120 CFU per g (sample 4). The parallel aliquot obtained from this sample was positive. The seminested PCR method detected as few as 8 CFU per g in one minced beef sample (sample 1) but yielded negative results for both portions of another minced meat sample inoculated with >50 CFU per g (sample 3). Positive results were obtained for a chicken sample spiked with 13 CFU per g (sample 5); however, this sample had to be excluded from the sensitivity evaluation due to the possible positive PCR results obtained for the unspiked control aliquot, which was analyzed only after overnight enrichment. As described above for one water sample, background organisms in the chicken samples generated nonspecific products whose sizes were similar to the size of the C. jejuni product and occasionally made interpretation of the PCR results difficult. Variable results were obtained during analysis of a spiced chicken sample (sample 6) and a pork sample (sample 7), and most results were negative.

(ii) Analysis with overnight enrichment.

Positive PCR results were obtained for all samples after overnight enrichment regardless of whether the overnight broth was diluted in sterile broth before it was prepared for the PCR analysis. The seminested PCR method detected fewer than 3 CFU per g after overnight enrichment of all samples. With three of the samples, positive results were obtained with an inoculation dose of ≤1 CFU per g. Most uninoculated control samples were negative; the only exception was one chicken product, as described above. No attempt was made to isolate Campylobacter cells from this product by conventional procedures.

DISCUSSION

When ingested with food or water, Campylobacter cells enter the host intestine via the stomach and colonize the distal ileum and colon (25). Production of flagella, which are the best-characterized virulence determinants of Campylobacter spp., is necessary for adhesion and colonization (25). A seminested PCR technique based on amplification of the intergenic sequence between the two Campylobacter flagellin genes, flaA and flaB, was used in combination with a enrichment step and a rapid and simple DNA preparation procedure to detect small numbers of C. jejuni cells in environmental water samples having different microbiological qualities, as well as in various meat samples. The oligonucleotide primers CF03, CF04, and CF02 previously described by Wegmüller et al. (60) were used because of their specificity for detecting C. jejuni and C. coli. The seminested approach increased the sensitivity of the assay and also increased the specificity. Any nonspecific amplicons produced during the first PCR step should not have functioned as target DNA during the second PCR step due to a lack of complementarity with the inner primer sequence, thus making confirmation of the product by a hybridization procedure unnecessary (3). Seminested PCR performed with primers CF03, CF04, and CF02 has been used previously to detect C. jejuni and C. coli in artificially and naturally contaminated milk and dairy products (1, 60) and in spiked distilled water samples (26).

Specificity testing of 41 Campylobacter strains and 20 strains belonging to other bacterial genera was performed due to modifications of the cycle numbers compared to the assay described by Wegmüller et al. (60). All of the C. jejuni and C. coli strains examined produced bands at the expected positions after both PCR steps. We examined 10 strains of C. lari, which is also a thermophilic pathogen and is the species that is most closely related to C. jejuni and C. coli (52, 54), and 7 of these strains generated products in the first PCR step. However, the sizes of the products were different from the sizes of the C. jejuni or C. coli amplicons. Amplification during the second PCR step was detected with only one strain, which generated an approximately 280-bp product. Wegmüller et al. reported that the two C. lari strains tested in their study produced a product which was about the same size as the C. jejuni and C. coli products obtained during the first PCR step but that the second PCR step did not amplify this product further; thus, the assay could be used to discriminate between C. lari and the C. jejuni-C. coli group. Our results indicate that some strains of C. lari may also produce a CF03-CF02 product; however, this product can be distinguished from the C. jejuni-C. coli product on the basis of different band positions.

The remaining eight Campylobacter strains and 20 strains belonging to other bacterial genera were negative in the tests. However, reducing the primer concentration from 0.25 to 0.2 μM during the first PCR step was sometimes necessary to reduce the number of nonspecific amplicons.

The sensitivity obtained for boiled C. jejuni lysate was 3 CFU, which corresponds to the sensitivity obtained by Wegmüller et al. (60) and to the sensitivity reported for other Campylobacter PCR assays (14, 31, 39, 56, 58).

Methods which could directly detect Campylobacter cells in environmental water samples without an enrichment step would be preferable, especially when viable but nonculturable cells are present. The major obstacle to the development of such methods is the presence of PCR inhibitors, such as humic substances. The insoluble fractions of these substances are concentrated along with bacteria on membrane filters, and extensive extraction procedures may be needed to eliminate the inhibitors prior to PCR (4). Such extraction procedures are often time-consuming and laborious, and there is a risk of losing target DNA in each purification step. Assays based on direct detection of bacterial cells in environmental water and sewage samples by filtration and PCR without an enrichment procedure have been developed during the past few years (5, 6, 30, 38, 40, 48, 55, 59). A disadvantage of such methods, however, is that they may detect dead bacteria as well as viable bacteria. Not only does an enrichment procedure dilute any inhibitors present, but dead bacteria are diluted as well, thus reducing the probability of detecting them by the subsequent PCR assay.

In this study, an enrichment procedure was combined with a rapid and simple lysis step prior to the PCR. Since antimicrobial agents could prevent growth of viable but nonculturable cells, a nonselective enrichment medium was used. According to Humphrey (19), damaged Campylobacter cells may be able to recover if they are incubated in a nonstressful nutrient medium. A preincubation step consisting of incubation at 37°C for 4 h was included prior to enrichment at 42°C, since this technique is known to increase the recovery of C. jejuni from naturally contaminated water samples by traditional isolation procedures (19).

Collection of bacterial cells from the enrichment broth by centrifugation followed by incubation with proteinase K and subsequent boiling to lyse the bacteria is a simple and rapid method for preparing DNA for PCR and does not involve any extraction or precipitation steps. As shown in Table 2, this technique combined with the seminested PCR method described above could detect as few as 3 to 15 CFU of C. jejuni per 100 ml in environmental water samples despite large numbers of background organisms. For water samples with high levels of background flora, dilution of the enriched broth media prior to centrifugation and lysis was sometimes necessary to obtain positive results, most likely because of inhibition due to the high levels of DNA in the samples. In addition to dilution of inhibitory substances, target organisms were diluted as well, which increased the risk of obtaining false-negative results when small numbers of Campylobacter cells were present. Our data show, however, that in all cases positive results were obtained for either concentrated broth or diluted broth or both. Analysis of both undiluted and diluted aliquots is thus recommended. Duplicate analyses are also preferable, since false-negative results may occasionally occur when the number of Campylobacter cells approaches the detection limit of the assay.

A water sample rich in humic matter was also included in this study (Table 2, sample 3). The seminested PCR assay detected as few as 3 CFU per 100 ml, indicating that the inhibitory substances did not interfere with the PCR when the protocol described above was used. It should be noted, however, that the bacteria used to spike the samples were freshly grown. Detection of sublethally damaged Campylobacter cells in naturally contaminated water with this assay should depend initially on the ability of the bacteria to recover from injury and enter the growth phase and subsequently on their capacity to compete with the background flora. PCR analysis of unspiked control aliquots of three of the water samples and the sewage sample, all containing high levels of background flora, gave positive results, indicating that the assay can detect Campylobacter cells in naturally contaminated water. The numbers and condition of the Campylobacter cells present in the samples are, however, not known.

The detection sensitivity of our assay is comparable to the sensitivity reported for a method described by Hernandez et al. (18) for detection of C. jejuni in artificially contaminated estuarine water with a background flora consisting of 900 total coliform bacteria per 100 ml and 2,000 CFU of heterotrophic bacteria per ml. In the study of Hernandez et al., prior to DNA extraction and PCR, filters were incubated in Preston broth for 24 and 48 h, and the detection limits were <30 and 3 CFU per 100 ml of water, respectively. Preston broth is a selective enrichment medium, and injured cells in naturally contaminated samples are thus not likely to grow, as discussed above. The incubation time necessary to obtain a sensitivity of 3 CFU/100 ml was also considerably longer than the incubation time for the assay described in this paper. Moreover, the PCR method of Hernandez et al. consisted of only one step and thus required a hybridization procedure to confirm the product specificity, and no primer specificity data were provided.

The sensitivity of the seminested PCR assay was also determined with various meat samples inoculated with known amounts of C. jejuni (Table 4). Less than 3 CFU per g of meat could be detected with all samples subjected to the overnight enrichment procedure, and with three of the samples a detection limit of <1 CFU per g was obtained. These results show that our assay can be applied to foods with high levels of background flora and can detect low levels of Campylobacter cells. The unspiked aliquot of one chicken sample was positive, indicating that it was naturally contaminated with Campylobacter cells. The results obtained for food samples analyzed at zero time without enrichment varied considerably, pointing out the need for an enrichment step in order to obtain reproducible results and a high degree of sensitivity.

In conclusion, the method described in this paper is specific for detection of C. jejuni and C. coli and can be used for environmental water samples having high levels of microbiological contamination or humic matter, as well as for food samples containing high levels of background flora. The assay can detect very small numbers of C. jejuni cells in highly contaminated samples when preparations are incubated in a nonselective enrichment medium prior to bacterial lysis and PCR. The analysis can be completed in 2 to 3 days, which is a considerably shorter period of time than is needed for traditional culturing and subsequent bacterial identification. Further analysis of naturally contaminated samples and comparisons with traditional culturing methods are needed to evaluate the applicability of the method for detection of Campylobacter cells exposed to an extraintestinal environment for a period of time. However, the positive PCR results obtained for the unspiked water, sewage, and chicken samples indicate that the method is capable of detecting such bacteria. The method described here should be a significant tool in monitoring environmental water and drinking water sources, including sources suspected to be involved in outbreaks of Campylobacter enteritis, for the presence of Campylobacter cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Norwegian Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allmann M, Höfelein C, Köppel E, Lüthy J, Meyer R, Niederhauser C, Wegmüller B, Candrian U. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of pathogenic microorganisms in bacteriological monitoring of dairy products. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:85–97. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allos B M, Blaser M J. Campylobacter jejuni and the expanding spectrum of related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1092–1101. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnheim N, Ehrlich H. Polymerase chain reaction strategy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:131–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bej A K, Mahbubani M H. Applications of the polymerase chain reaction in environmental microbiology. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;1:151–159. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.3.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bej A K, Mahbubani M H, Dicesare J L, Atlas R M. Polymerase chain reaction-gene probe detection of microorganisms by using filter-concentrated samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3529–3534. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3529-3534.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bej A K, McCarty S C, Atlas R M. Detection of coliform bacteria and Escherichia coli by multiplex polymerase chain reaction: comparison with defined substrate and plating methods for water quality monitoring. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2429–2432. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.8.2429-2432.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black R E, Levine M M, Clements M L, Hughes T P, Blaser M J. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:472–479. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaser M J, Hardesty H L, Powers B, Wang W-L L. Survival of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni in biological milieus. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:309–313. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.4.309-313.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaser M J, Taylor D N, Feldman R A. Epidemiology of Campylobacter infections. In: Butzler J-P, editor. Campylobacter infection in man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1984. pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter A M, Pacha R E, Clark G W, Williams E A. Seasonal occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in surface waters and their correlation with standard indicator bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:523–526. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.523-526.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekeyser P, Gossuin-Detrain M, Butzler J P, Sternon J. Acute enteritis due to related vibrio: first positive stool cultures. J Infect Dis. 1972;125:390–392. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Docherty L, Adams M R, Patel P, McFadden J. The magnetic immuno-polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Campylobacter in milk and poultry. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:288–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenstein B I. The polymerase chain reaction: a new method of using molecular genetics for medical diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:178–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001183220307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyers M, Chapelle S, Van Camp G, Goossens H, De Wachter R. Discrimination among thermophilic Campylobacter species by polymerase chain reaction amplification of 23S rRNA gene fragments. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3340–3343. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3340-3343.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giesendorf B A J, Quint W G V. Detection and identification of Campylobacter spp. using the polymerase chain reaction. Cell Mol Biol. 1995;41:625–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giesendorf B A J, Quint W G V, Henkens M H C, Stegeman H, Huf F A, Niesters H G M. Rapid and sensitive detection of Campylobacter spp. in chicken products by using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3804–3808. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3804-3808.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazeleger W, Arkesteijn C, Toorop-Bouma A, Beumer R. Detection of the coccoid form of Campylobacter jejuni in chicken products with the use of the polymerase chain reaction. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;24:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez J, Alonso J L, Fayos A, Amoros I, Owen R J. Development of a PCR assay combined with a short enrichment culture for detection of Campylobacter jejuni in estuarine surface waters. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey T J. Techniques for the optimum recovery of cold injured Campylobacter jejuni from milk or water. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;61:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb04265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson C J, Fox A J, Jones D M. A novel polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection and speciation of thermophilic Campylobacter spp. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones D M, Sutcliffe E M, Curry A. Recovery of viable but non-culturable Campylobacter jejuni. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2477–2482. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-10-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapperud G, Rosef O. Avian wildlife reservoir of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni, Yersinia spp., and Salmonella spp. in Norway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:375–380. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.375-380.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapperud G, Skjerve E, Vik L, Hauge K, Lysaker A, Aalmen I, Ostroff S M, Potter M. Epidemiological investigation of risk factors for campylobacter colonization in Norwegian broiler flocks. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:245–255. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapperud G, Vardund T, Skjerve E, Hornes E, Michaelsen T E. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica in foods and water by immunomagnetic separation, nested polymerase chain reactions, and colorimetric detection of amplified DNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2938–2944. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.2938-2944.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ketley J M. Virulence of Campylobacter species: a molecular genetic approach. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:312–327. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-5-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirk R, Rowe M T. A PCR assay for the detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in water. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;19:301–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenraad P M F J, Giesendorf B A J, Henkens M H C, Beumer R R, Quint W G V. Methods for the detection of Campylobacter in sewage: evaluation of efficacy of enrichment and isolation media, applicability of polymerase chain reaction and latex agglutination assay. J Microbiol Methods. 1995;23:309–320. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linton D, Lawson A J, Owen R J, Stanley J. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2568–2572. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2568-2572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzano M, Pipan C, Botta G, Comi G. Polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in poultry meat. Zentbl Hyg Umweltmed. 1995;197:370–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald I R, Kenna E M, Murrell J C. Detection of methanotrophic bacteria in environmental samples with the PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:116–121. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.116-121.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng L-K, Kingombe C I B, Yan W, Taylor D E, Hiratsuka K, Malik N, Garcia M M. Specific detection and confirmation of Campylobacter jejuni by DNA hybridization and PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4558–4563. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4558-4563.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordic Committee on Food Analysis. Coliform bacteria. Determination in foods. Method no. 44. 2nd ed. Esbo, Finland: Nordic Committee on Food Analysis; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nordic Committee on Food Analysis. Aerobic microorganisms. Enumeration at 30°C in meat and meat products. Method no. 86. 2nd ed. Esbo, Finland: Nordic Committee on Food Analysis; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norwegian Standards Association. Water analysis. Techniques for quantitative determination of microorganisms in water, sediments and sewage sludge (NS 4790). Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Standards Association; 1989. . (In Norwegian.) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norwegian Standards Association. Water analysis. Coliform bacteria, thermotolerant coliform bacteria, and presumptive E. coli. MPN method (NS 4714). Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Standards Association; 1990. . (In Norwegian.) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norwegian Standards Association. Water analysis. Heterotrophic plate count. Pour plate technique (NS 4791). Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Standards Association; 1990. . (In Norwegian.) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oyofo B A, Abd El Salam S M, Churilla A M, Wasfy M O. Rapid and sensitive detection of Campylobacter spp. from chicken using the polymerase chain reaction. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1997;285:480–485. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(97)80108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyofo B A, Rollins D M. Efficacy of filter types for detecting Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in environmental water samples by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4090–4095. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4090-4095.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oyofo B A, Thornton S A, Burr D H, Trust T J, Pavlovskis O R, Guerry P. Specific detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli by using polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2613–2619. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2613-2619.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmer C J, Tsai Y-L, Paszko-Kolva C, Mayer C, Sangermano L R. Detection of Legionella species in sewage and ocean water by polymerase chain reaction, direct fluorescent-antibody, and plate culture methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3618–3624. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3618-3624.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park R W A, Griffiths P L, Moreno G S. Sources and survival of campylobacters: relevance to enteritis and the food industry. J Appl Bacteriol Symp Suppl. 1991;70:97S–106S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson A D, Greenwood M, Healing T D, Rollins D, Shahamat M, Donaldson J, Colwell R R. Colonization of broiler chickens by waterborne Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:987–996. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.987-996.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasmussen H N, Olsen J E, Jørgensen K, Rasmussen O F. Detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Camp. coli in chicken faecal samples by PCR. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson D A. Infective dose of Campylobacter jejuni in milk. Br Med J. 1981;282:1584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6276.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rollins D M, Colwell R R. Viable but nonculturable stage of Campylobacter jejuni and its role in survival in the natural aquatic environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:531–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.3.531-538.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosef O. Isolation of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni from the gall bladder of normal slaughter pigs, using an enrichment procedure. Acta Vet Scand. 1981;22:149–151. doi: 10.1186/BF03547219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinigalliano C D, Kuhn D N, Jones R D. Amplification of the amoA gene from diverse species of ammonium-oxidizing bacteria and from an indigenous bacterial population from seawater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2702–2706. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2702-2706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skirrow M B, Blaser M J. Clinical and epidemiologic considerations. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L S, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steffan R J, Atlas R M. Polymerase chain reaction: applications in environmental microbiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stern N J. Reservoirs for Campylobacter jejuni and approaches for intervention in poultry. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stern N J, Kazmi S U. Campylobacter jejuni. In: Doyle M P, editor. Foodborne bacterial pathogens. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. pp. 71–110. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tauxe R V. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, Tompkins L, editors. Campylobacter jejuni: current status and future trends. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tauxe R V, Patton C M, Edmonds P, Barrett T J, Brenner D J, Blake P A. Illness associated with Campylobacter laridis, a newly recognized Campylobacter species. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:222–225. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.2.222-225.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai Y-L, Palmer C J, Sangermano L R. Detection of Escherichia coli in sewage and sludge by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:353–357. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.353-357.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Camp G, Fierens H, Vandamme P, Goossens H, Huyghebaert A, De Wachter R. Identification of enteropathogenic Campylobacter species by oligonucleotide probes and polymerase chain reaction based on 16S rRNA genes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waegel A, Nachamkin I. Detection and molecular typing of Campylobacter jejuni in fecal samples by polymerase chain reaction. Mol Cell Probes. 1996;10:75–80. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1996.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang R-F, Slavik M F, Cao W-W. A rapid PCR method for direct detection of low numbers of Campylobacter jejuni. J Rapid Methods Autom Microbiol. 1992;1:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Way J S, Josephson K L, Pillai S D, Abbaszadegan M, Gerba C P, Pepper I L. Specific detection of Salmonella spp. by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1473–1479. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1473-1479.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wegmüller B, Lüthy J, Candrian U. Direct polymerase chain reaction detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in raw milk and dairy products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2161–2165. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2161-2165.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winters D K, Slavik M F. Evaluation of a PCR based assay for specific detection of Campylobacter jejuni in chicken washes. Mol Cell Probes. 1995;9:307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0890-8508(95)91556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]