SUMMARY

Background:

Early microbiota perturbations are associated with disorders that involve immunological underpinnings. Cesarean section (CS)-born babies show altered microbiota development in relation to babies born vaginally. Here we present the first statistically powered longitudinal study to determine the effect of restoring exposure to maternal vaginal fluids after CS birth.

Methods:

Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we followed the microbial trajectories of multiple body sites in 177 babies over the first year of life; 98 were born vaginally and 79 were born by CS, of which 30 were swabbed with a maternal vaginal gauze right after birth.

Findings:

Compositional tensor factorization analysis confirmed that microbiota trajectories of exposed CS-born babies aligned closer to that of vaginally born babies. Interestingly, the majority of amplicon sequence variants from maternal vaginal microbiomes on the day of birth were shared with other maternal sites, in contrast to non-pregnant women from the HMP study.

Conclusions:

The results of this observational study prompt the urgent need of randomized clinical trials to test whether microbial restoration reduces the increased disease risk associated with CS birth, and the underlying mechanisms. Also, it provides evidence for the pluripotential nature of maternal vaginal fluids to provide pioneer bacterial colonizers for the newborn body sites. This is the first study showing long term naturalization of the microbiota of CS-born infants by restoring microbial exposure at birth.

Funding:

C&D, Emch Fund, CIFAR, Chilean CONICYT and SOCHIPE, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the Emerald Foundation, NIH, National Institute of Justice, Janssen.

eTOC blurb

C-section alters the maturation of the infant microbiota. Song et al. show that restoring maternal microbes immediately after birth in Cesarean-born infants naturalizes their microbiota developmental trajectory. Perinatally, the maternal vaginal fluids appear pluripotential to provide pioneer bacterial colonizers for the newborn body sites.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, we have learned a great deal about the multitude of ways that microbiota affect the development of their hosts. Studies on model organisms show that fetal development can be modulated by microbial products from the pregnant mother’s microbiota, and early colonization is critical for immune system development1,2.

Natural transmission and colonization of maternal microbes is impaired by delivery via Cesarean section (CS)3–7. Furthermore, CS birth is associated with reduced levels of various cytokines and their receptors8, increased risk of opportunistic neonatal infections6, immune diseases9 10 and obesity11,12. These associations have been shown to be causal in mouse models for conditions such as obesity13,14, and immune disorders15,16. Neuroendocrine abnormalities including cognitive and behavioral disorders have also been associated with early microbiome perturbations17,18. Understanding the contribution of microbionts to healthy development remains a crucial challenge to address the current epidemic of immune and metabolic diseases in urban societies.

Although used without medical indication in many countries, CS delivery is often medically necessary and a life-saving procedure, and thus, restoration may be one solution to help reduce the risk of associated disorders related to the microbiome. Two proof of concept studies have demonstrated the principle of engraftment of maternal bacteria on CS born babies after deliberate microbial exposure: the first one by Dominguez-Bello et al. using maternal vaginal gauze as a source19, and the second recent pilot study by Korpela et al. using maternal feces20. Here we present the first large observational study of the long-term effect of maternal vaginal seeding after CS delivery to restore microbial development during the first year of life.

RESULTS

Vaginal seeding of CS born infants

A total of 177 infants born to 174 mothers were studied (Figure S1a), of which 101 were born in USA, 50 in Chile, 6 in Bolivia, and 20 in Spain (Table 1). 98 infants were born vaginally and 79 were delivered by CS, of which 30, who complied with inclusion criteria (see Star Methods), were swabbed with a maternal vaginal gauze at birth (vaginal seeding19). The microbiota development was followed during the first year of life. A total of 8,104 samples from stool, mouth, and skin of infants and their mothers were obtained, with additional nasal and vaginal samples from mothers (Figure S1a–c). None of the seeded infants had any complications, and all children developed normally during the 12 months of the study.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of families included in this study for analysis.

| Vaginal | Cesarean | Cesarean-Seeded | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Families | 97 | 49 | 28 | |

| Number of Babies | Total | 98 | 49 | 30 |

| USA | 62 | 23 | 16 | |

| Spain | 7 | 5 | 8 | |

| Chile | 26 | 18 | 6 | |

| Bolivia | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Baby female sex (%) | 52.0 | 38.8 | 46.7 | |

| Mean baby follow-up, months (standard deviation) | 6.2 (5.1) | 8.8 (4.7) | 7.1(5.2) | |

| Baby antibiotics use within the Study Period (after week 1) | ||||

| Any (%) | 18.4 | 20.4 | 16.7 | |

| 1 dose (%) | 7.1 | 14.3 | 3.3 | |

| >1 doses (%) | 11.3 | 6.1 | 13.4 | |

| Breast Feeding Dominant within first 4 month1(%) | 75.5 | 69.4 | 53.3 | |

| Mother tested positive to Group B Streptococcus (%) | 8.9 | 11.1 | 0 | |

| Use of Perinatal Antibiotics in Mother2(%) | 13.3 | 95.6 | 95.8 | |

| Any Use of Antibiotics during Pregnancy (%) | 20 | 26.7 | 16.7 | |

Breast feeding dominant is defined as the mothers who reported breastfeeding exclusively or >50% of breastfeeding in at least 60% of follow-up visits.

Use of perinatal antibiotics is part of the standard-of-care for women underwent Cesarean birth.

Vaginal seeding partly normalizes microbiome trajectories in C-section-delivered infants

Across the different body sites, the samples yielded good overall sequencing depth (mean depth of 63,035 paired-end reads per sample), with a low probability of sample contamination as indicated by a survey of negative controls (Figure S1d). Analysis of the vaginal gauzes stored in the vagina for an hour before the CS procedure with which the neonates were swabbed showed that ~76% of bacterial amplicon sequence variants (ASVs, see Star Methods) contained in maternal vaginal swabs were also present in the gauzes (Figure S2a).

Some studies have reported decreased alpha diversity in CS born versus vaginally-born infants21https://paperpile.com/c/vcRyUI/OTkm. Yet, others have reported no differences by birth mode4,5. Using a linear mixed-effects model, we found inconsistent results depending on the body site and alpha-diversity metric (Supplementary Methods S1). One possibility for this inconsistency is that the dynamic nature of the developing microbiome can be highly non-linear, and often times, data collected longitudinally vary in frequency and timing across individuals. To account for these potential irregularities we applied a novel method called Bayesian Sparse Functional Principal Components Analysis (SFPCA; Jiang et al.22 to estimate individual trajectories (see STAR Methods). Using SFPCA, we found that alpha diversity trajectories did not differ among birth modes when measured as Shannon diversity (Figure S3), or when accounting for phylogenetic relatedness (SFPCA on Faith’s PD, data not shown).

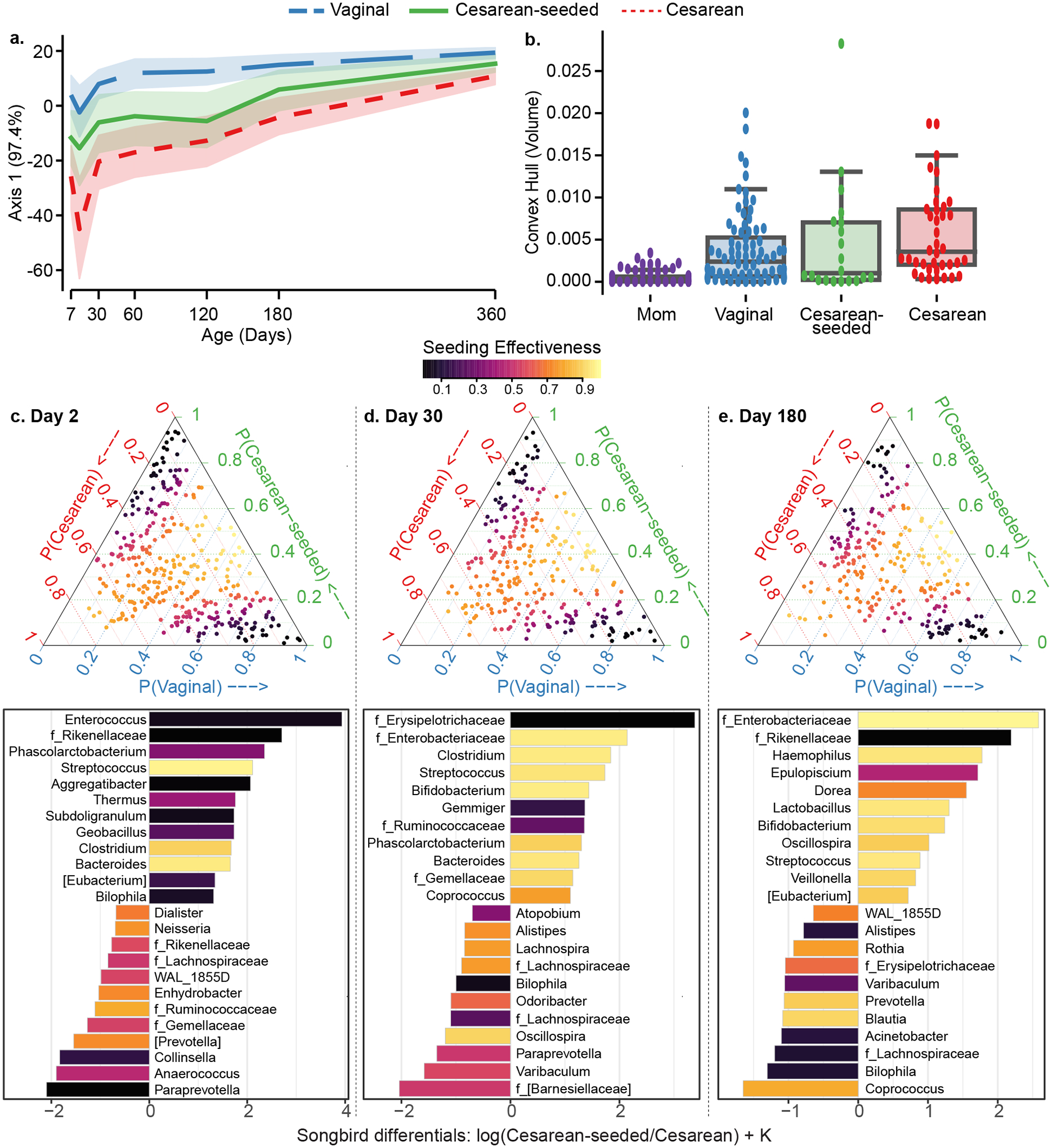

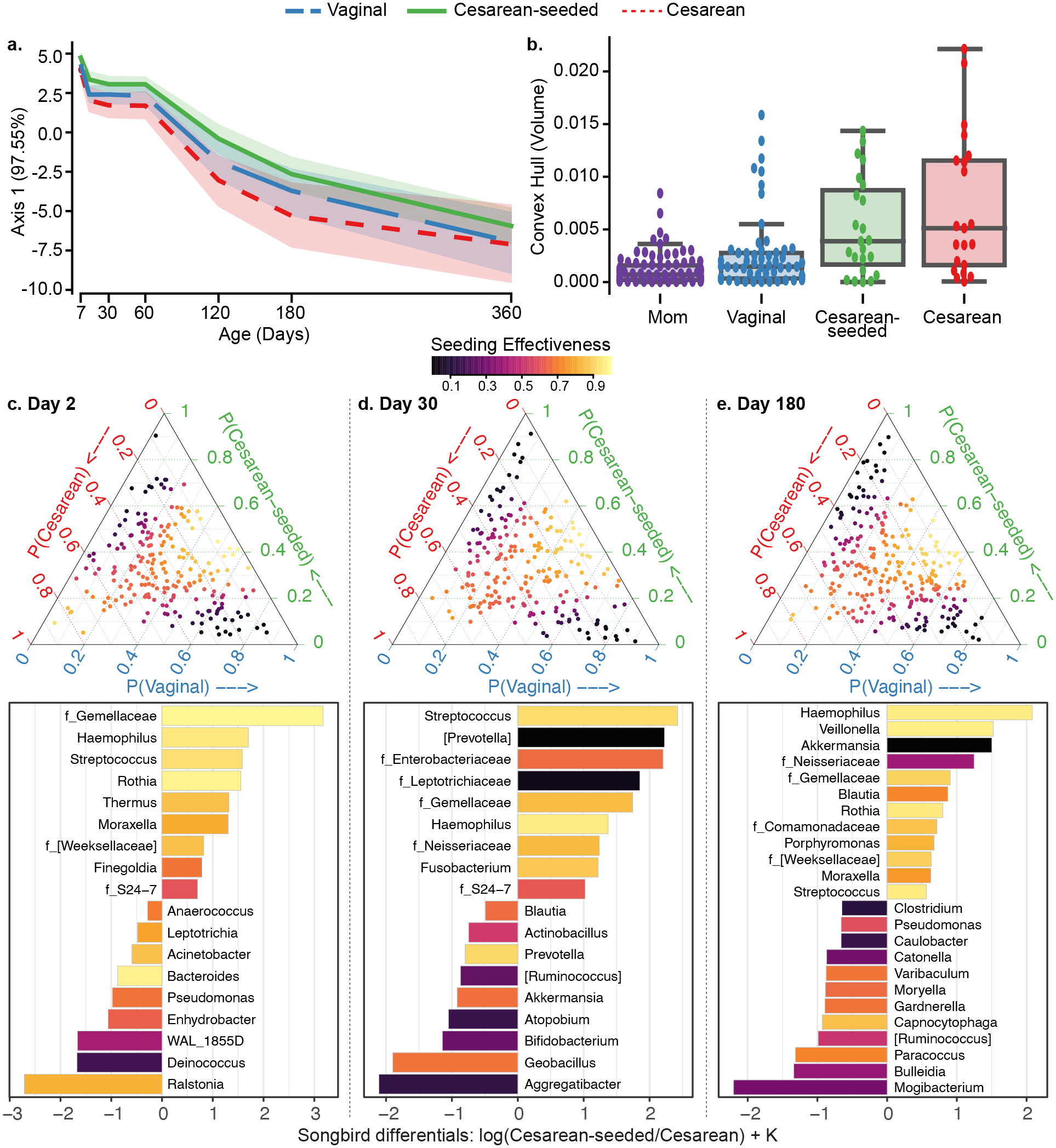

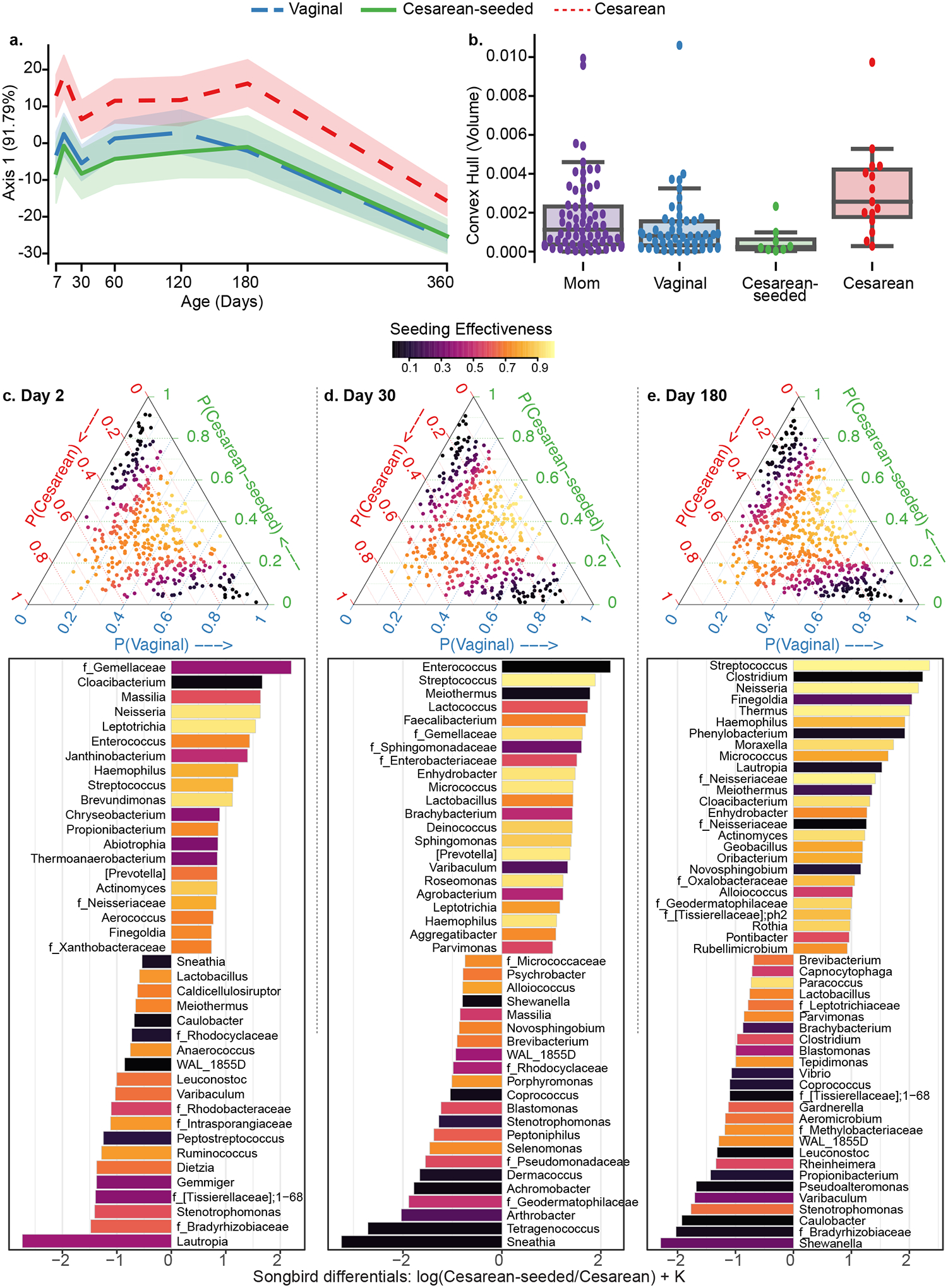

However, significant birth group differences were found in beta diversity when using an unsupervised dimensionality reduction method called Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF)23. CTF accounts for the repeated measurements allowing comparisons of beta-diversity over time (‘trajectory’) while accounting for the sparse, compositional nature of next-generation microbiome sequencing data24,25. The trajectory of gut microbiota development in CS born infants diverged from that of vaginally born infants through the entire first year of life (Figure 1). These results are consistent with findings from previous studies that used more traditional analysis approaches4,5. CTF also detected measurable differences in the microbial development of the mouth (Figure 2) and skin (Figure 3), underscoring the importance of birth mode in affecting multiple microbial niches during human development.

Figure 1. Fecal microbiota development during the first year of life in babies discordant to birth mode/exposure.

(a) Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) first principal component (Y-axis) of infant samples over age in days (X-axis). (b) Convex hull volume (Y-axis) on the first three Principal Coordinates (unweighted UniFrac distances) in mothers (purple) and infants by birth mode or exposure (X-axis). Infants show highest volumes in Cesarean born and lowest in Vaginally born, with Cesarean-seeded babies showing intermediate volumes; all pairwise comparisons are significant using Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni corrections at 0.05 level (Table S3). (c-e) Songbird differentials shown for day 2, 30, and 180 after birth; ternary plots of the inverse additive log-ratio transform (inverse-ALR) of Songbird differentials give the estimated probability of a microbe being observed in Cesarean (left-axes; red), Vaginal (bottom-axes; blue), or Cesarean-seeded (right-axes; green). The color of the dots depicts the seeding effectiveness, with yellow color indicating effectively seeded/suppressed and black indicating not effectively seeded. Below each triangle, bar plots of top and bottom 20% Songbird differentials summarized at genus-level taxa between Cesarean-seeded and Cesarean born babies; a positive value indicates higher association with the Cesarean-seeded group, a negative value indicates higher with Cesarean. Bars are colored by the ASVs’ seeding effectiveness. The majority of taxa discordant overrepresented in the Cesarean-seeded group over the Cesarean group are yellow-orange, indicating ASVs effectively seeded in the Cesarean seeded group, and these are observed at all ages.

See also Figure S4, Supplementary Methods S2–S7.

Figure 2. Oral microbiota development during the first year of life in babies discordant to birth mode/exposure.

(a) Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) first principal component (Y-axis) of infant samples over age in days (X-axis). (b) Convex hull volume (Y-axis) on the first three Principal Coordinates (unweighted UniFrac distances) in mothers (purple) and infants by birth mode or exposure (X-axis). Infants show highest volumes in Cesarean born and lowest in Vaginally born, with Cesarean-seeded babies showing intermediate volumes; all pairwise comparisons are significant using Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni corrections at 0.05 level (Table S3). (c-e) Songbird differentials shown for day 2, 30, and 180 after birth; ternary plots of the inverse additive log-ratio transform (inverse-ALR) of Songbird differentials give the estimated probability of a microbe being observed in Cesarean (left-axes; red), Vaginal (bottom-axes; blue), or Cesarean-seeded (right-axes; green). The color of the dots depicts the seeding effectiveness, with yellow color indicating effectively seeded/suppressed and black indicating not effectively seeded. Below each triangle, bar plots of top and bottom 20% Songbird differentials summarized at genus-level taxa between Cesarean-seeded and Cesarean born babies; a positive value indicates higher association with the Cesarean-seeded group, a negative value indicates higher with Cesarean. Bars are colored by the ASVs’ seeding effectiveness. The majority of taxa discordant overrepresented in the Cesarean-seeded group over the Cesarean group are yellow–orange, indicating ASVs effectively seeded in the Cesarean seeded group, and these are observed at all ages. See also Figure S4, Supplementary Methods S2–S7.

Figure 3. Skin microbiota development during the first year of life in babies discordant to birth mode/exposure.

(a) Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) first principal component (Y-axis) of infant samples over age in days (X-axis). (b) Convex hull volume (Y-axis) on the first three Principal Coordinates (unweighted UniFrac distances) in mothers (purple) and infants by birth mode or exposure (X-axis). Infants show highest volumes in Cesarean born and lowest in Vaginally born, with Cesarean-seeded babies showing intermediate volumes; all but one pairwise comparison are significant using Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni corrections at 0.05 level (Table S3). (c-e) Songbird differentials shown for day 2, 30, and 180 after birth; ternary plots of the inverse additive log-ratio transform (inverse-ALR) of Songbird differentials give the estimated probability of a microbe being observed in Cesarean (left-axes; red), Vaginal (bottom-axes; blue), or Cesarean-seeded (right-axes; green). The color of the dots depicts the seeding effectiveness, with yellow color indicating effectively seeded/suppressed and black indicating not effectively seeded. Below each triangle, bar plots of top and bottom 20% Songbird differentials summarized at genus-level taxa between Cesarean-seeded and Cesarean born babies; a positive value indicates higher association with the Cesarean-seeded group, a negative value indicates higher with Cesarean. Bars are colored by the ASVs’ seeding effectiveness. The majority of taxa discordant overrepresented in the Cesarean-seeded group over the Cesarean group are yellow–orange, indicating ASVs effectively seeded in the Cesarean seeded group, and these are observed at all ages. See also Figure S4, Supplementary Methods S2–S7.

Seeding CS-born infants led to a developmental trajectory that more closely resembled that of vaginally-born infants most prominently in feces (Figure 1, S4a,b) and skin (Figure 3, S4a,b); this trend held when considering only the 101 babies born in the US (Figure S4c), while other countries lacked sufficient sample size for individual analysis. Furthermore, a stepwise redundancy analysis based on the first three principal components of CTF ordination26 confirmed that birth mode significantly contributed to differences in microbial community structures in the gut and on skin, but not in the mouth, with effect sizes of 0.17 (R2) in fecal samples and 0.09 in skin samples (Supplementary Methods S2). Analyzing these data using more conventional tools for comparing beta diversity that do not account for interindividual variation in repeated measure studies (Supplementary Methods S3–S4), evaluated through PERMANOVA (on unweighted Unifrac distance) or RDA (on PCoA PCs), expectedly reveals individuals as the primary driver of variation (PERMANOVA F-statistic = 5.45, P-value <= 0.001; RDA adjusted R2 = 0.113, Supplementary Methods S5). High interindividual variation obscured the ability to detect differences due to more muted factors such as birth mode using these methods. Together, these findings reveal that birth mode affects the development of microbial communities, and that this effect may be undetected upon analyses with traditional bioinformatic tools.

Differences in microbial composition stability have been used to differentiate phenotypes in longitudinal studies27,28. Accordingly, we next compared variability across samples over time within a given individual. To leverage the dense sampling design, we calculated the volume of the shape determined by an individual’s samples in the first 3 principal coordinates of unweighted UniFrac space using a convex hull analysis (see STAR Methods). As expected, the average variability of the microbiome over an infant’s first year of life was much greater than the variability in the mother’s microbiome (Figure 1b, 2b, 3b). CS born infants had significantly greater microbial variability than vaginally born infants, and the variability of seeded infants was intermediate (Figure 1b, 2b, 3b, Supplementary Methods S6). This finding held true for fecal, oral and skin samples, suggesting that vaginal seeding may also help stabilize microbiome development. This trend can also be observed using data within the first 6 months (Supplementary Methods S7). Possible confounders such as antibiotic consumption (which was similar between baby groups; Table 1) were discarded; in the CS born and restored babies, stepwise RDA did not recognize antibiotic consumption as a factor altering seeding efficiency. In summary, these results indicate that vaginal seeding resulted in partial recovery of the microbiome in CS-delivered infants.

Bacterial taxa associated with effective seeding

To determine whether specific microbial taxonomies were being seeded well or the overall seeding across all microbes was partial, we first identified which taxa were most associated with a vaginal birth compared to a CS birth using Songbird25, and then calculated a seeding-effectiveness score for those taxa (see STAR Methods; zero indicates poor seeding and one indicates effective seeding or effectively suppressed). Effectively seeded microbes are those shared by vaginal and CS-seeded infants. Effectively suppressed microbes are those highly associated only with unseeded CS infants, indicating that seeding excludes that microbe. Many taxa highly associated with CS-seeded infants had a seeding effectiveness score greater than 0.8, indicating that the vaginal seeding method was able to establish microbes missing in CS born babies (Figure 1, 2, 3, c–e). Notably, in the infant gut, ASVs from common gut-associated genera such as Bacteroides, Streptococcus, and Clostridium were identified to be enriched in CS-seeded infants and have high seeding effectiveness scores in early time points (Figure 1 c–e, Supplementary Methods S8–S9). Especially of note, Bacteroides was consistently identified as being associated with vaginal seeding (Supplementary Methods S10) using other algorithms such as ANCOM (Supplementary Methods S11), MaAsLin2 (Supplementary Methods S12) and LEfSe (Supplementary Methods S13). In the mouth, bacteria with high seeding effectiveness scores included ASVs from Gemellaceae, Haemophilus, and Streptococcus (Figure 2 c–e). In the skin, taxa included ASVs from Streptococcus, Neisseria, Thermus, and Neisseriaceae (Figure 3 c–e). However, across all three body sites, most of the taxa associated with CS had a moderate to low seeding effectiveness score, indicating that this method was not effective at attenuating the presence of microbes typically depleted in vaginally born babies.

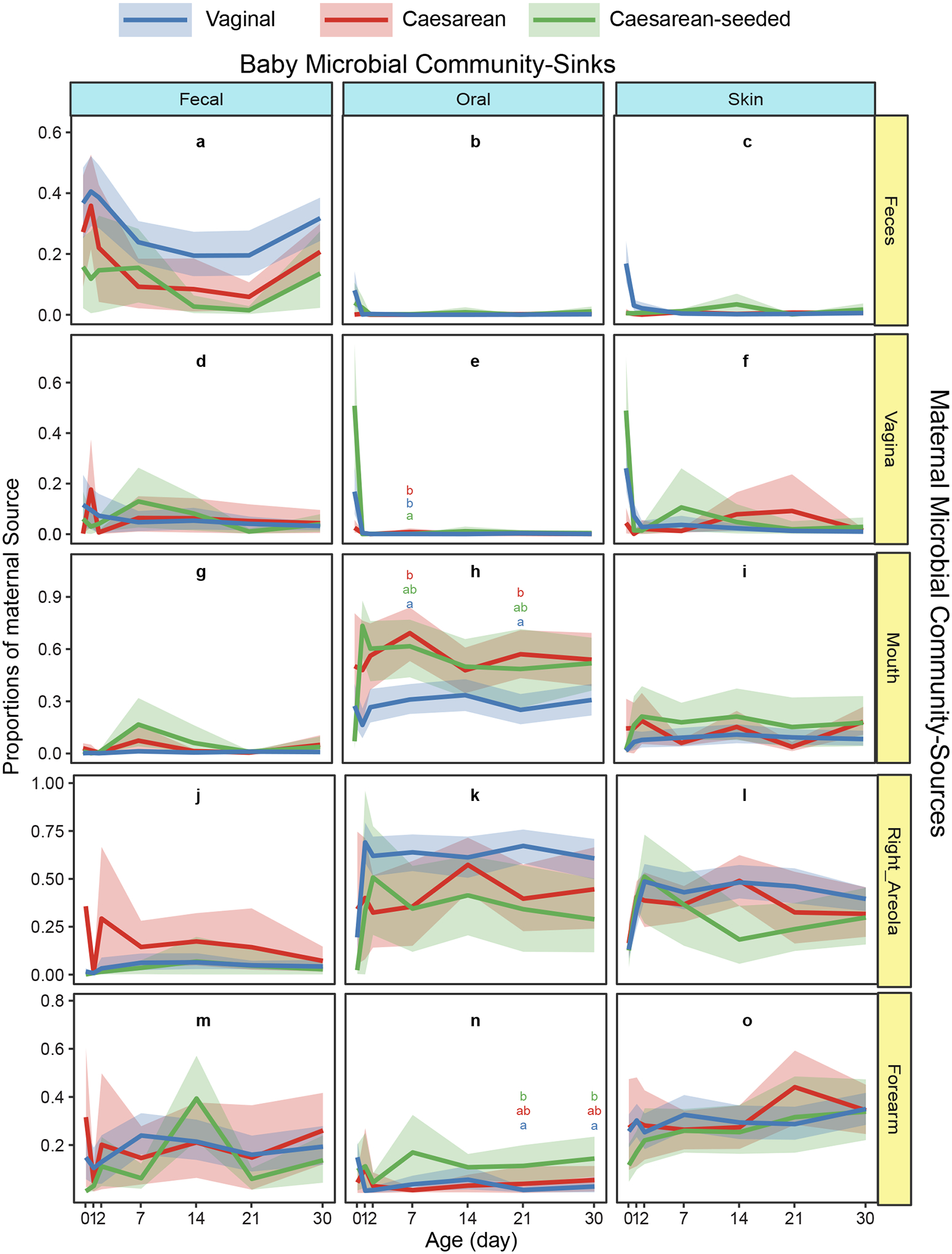

Maternal sites contribute to the infant microbiota

In order to determine which body sites from the mother were most likely to have the highest contributions towards shaping the infant microbiome, we also used the source-tracking tool FEAST29. The first 2 days of life showed a prominent maternal vaginal source in the oral and skin sites of infants exposed to vaginal fluids; however, within the first few days, a large proportion of the microbiota colonizing the infants’ sites was shared with the corresponding maternal site, regardless of birth mode or seeding status (Figure 4). Selection by the specific body site was evidenced by the lack of overrepresentation of Lactobacillus, a dominant member of the mother’s vagina, among infants born vaginally or exposed to the vaginal gauze when compared to CS-born babies. Unsurprisingly, we found that the infant oral microbiota most resembled that of the mother’s mouth and areola (Figure 4 h, k), and that the infant skin microbiota resembled that of the mother’s skin (Figure 4 o), consistent with exposure patterns and differential selection exerted by different body sites in the baby.

Figure 4. Microbial source tracking of the neonate microbiome (first month) through fast expectation-maximization microbial source tracking (FEAST).

Contributions (y-axes) of various maternal sources (rows) to the infant microbial community (columns) are estimated across age in days (x-axes) for the first month of life, in 15 mother-baby pairs. Error bars show 95% confidence interval of the mean calculated by bootstrapping; Dunn test based on Kruskal-Wallis were performed on each time points by each maternal source for each baby sink, significant differences are marked by different letters in each panel. The vaginal source -prominent in day “0” for oral and skin in babies exposed to vaginal fluids (vaginal and CS-seeded; panel e, f)- as not prominent later in any baby site. Baby site specific communities resemble the corresponding maternal site (panels a, h, o), consistent with specific site selection of bacteria. The maternal right areola appears as a source for baby oral bacteria (panel k), which likely means that baby oral bacteria is transmitted to the mother’s areola during lactation.

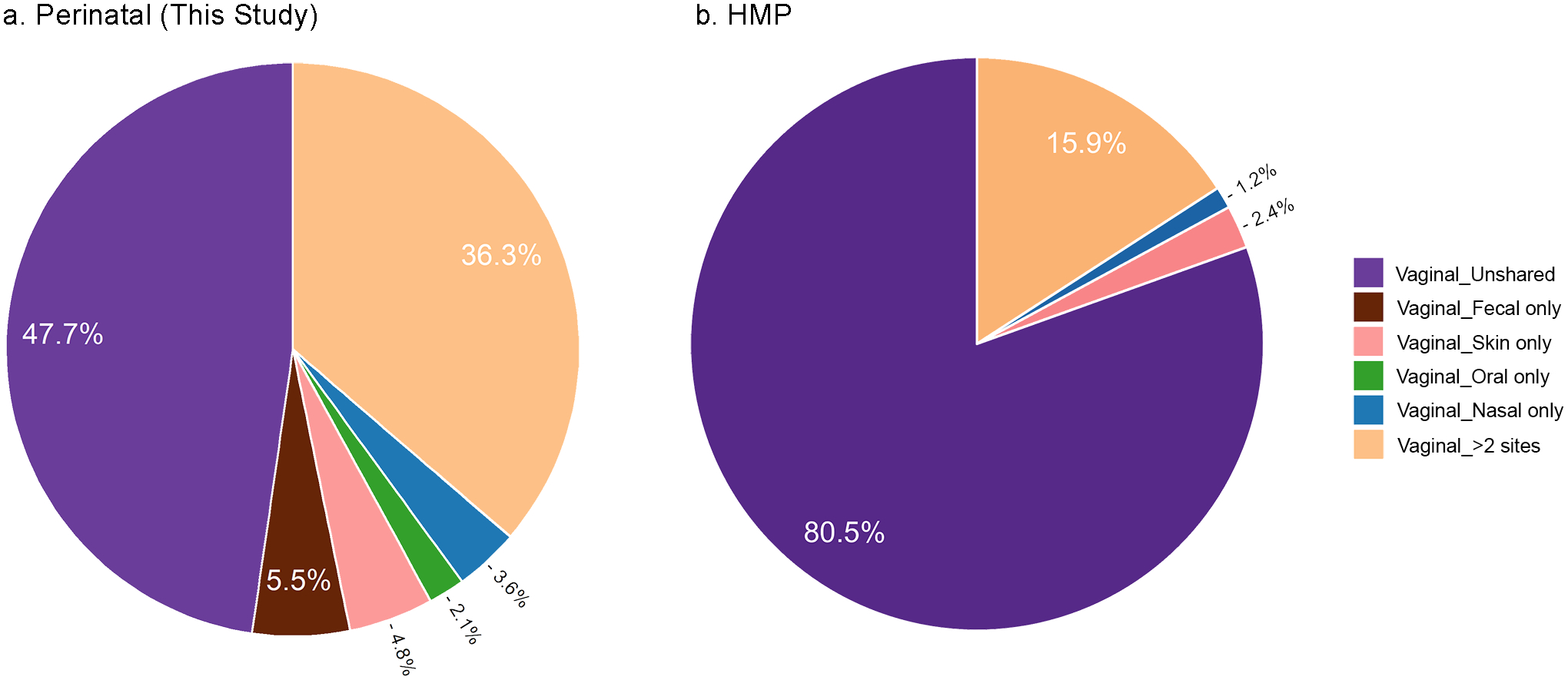

Interestingly, we observed a notable taxonomic overlap between the maternal vagina and other maternal body sites, especially feces, on the day of giving birth: nearly 30% of the bacterial ASVs in vaginal samples were shared with feces (5.5% with feces alone, and 24.5% with feces and some other body sites), and 22.3% with more distant body sites such as arm skin, mouth, and nose (Figure 5 a, Supplementary Methods S14). These trends showing the pluripotent nature of the perinatal vaginal microbiome held true when examining the mothers in different countries from this study, despite variations in specific proportions (Figure S2b,c, Supplementary Methods S15). In contrast, women who are not pregnant -from the HMP study- shared less than 20% of vaginal ASVs with other body sites, predominantly with skin, and none with fecal samples (Figure 5 b). Together, these results point to the importance of maternal sources of microbes on the developing infant consortium.

Figure 5. Proportions of bacterial vaginal ASVs shared with other body sites in the mothers of the current study, at the day of delivery (a) and in non-pregnant women (b).

(a) V4 sequences from vaginal swabs and gauzes obtained from 97 parturient mothers form this study at the day of birth. Current study data were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq and processed by QIIME2 using the same pipeline as for the HMP data. (b) HMP V4 data from vaginal swabs obtained from 105 non-pregnant women; ASVs included in the analyses were present in at least 10% of the samples in the respective body site. Roche 454 V3V5 sequences were trimmed to obtain the V4 region. See also Figure S2 b–c, Supplementary Methods S13–S14.

DISCUSSION

This intervention study expands the findings of previous smaller studies, further demonstrating that microbial differences associated with delivery mode can be reduced by exposure to a vaginal microbial source at birth. The study only included scheduled C-sections on healthy mothers (mostly due to multiple previous C-sections and to malposition presentations), since infants born by emergency C-section after rupture of the chorioamniotic membrane are likely exposed the maternal microbes, given enough time before the C-section procedure30.

Using advanced and longitudinally-aware methods, we found that birth mode significantly differentiated infant gut and skin microbiome development, and that seeding worked to adjust the trajectory of CS-delivered infants through partial restoration of microbiome features associated with a vaginal delivery. For example, differential abundance analyses confirmed previous findings that in the gut, Bacteroides and Parabacteroides-- both common gut-associated taxa--are highly associated with vaginally born infants. Our study further shows that seeding works to effectively restore these and other taxa associated with a vaginal birth. However, there are several other taxa that do not appear to establish well in the seeded infants (e.g. Bilophila). Also of interest, while we observed a significant association of Enterococcus with CS-born infants (which in previous studies has been noted as a potential opportunistic pathogen), we did not see a weakened association of this taxon, or most other CS-associated taxa, with seeded babies. Further research is needed to determine why certain gut taxa may show a higher effectiveness for seeding while other taxa may exhibit more resilience after a seeding procedure, and what roles these microbes may play in the developing infant microbiome.

An interesting facet of our study is the finding that vaginal seeding led to converging microbial compositions in the infant gut, despite the exposure coming from a vaginal source. The same pattern was observed in the skin environment. Our results clearly indicate that from very early timepoints, the microbiota of an infant largely resembles the same maternal site, supporting the idea of strong site selection occurring from very early ages (i.e. that different body sites will select for specific microbes out of a diverse population). This is further supported by the finding that Lactobacillaceae, the most dominant member of the mother’s vagina, was not identified as one of the most differentially abundant taxa among infants at any of the three body sites observed. Site selection is also consistent with the recent evidence of successful engraftment after fecal microbiota transplant from the mother to CS neonates31, and with previous evidence of fecal bacteria in the infant gut32,33. Indeed, bacterial transfer from homologous sites from the mother and other family members surely occur after birth. However, this may only be a part of the story. Our results show that unlike in non-pregnant women, more ASVs from the vaginal microbiome from parturient women overlap with those in other body sites, mostly the proximal rectum (which in mammals is next to the reproductive canal), but also more distant sites. This strongly suggests a pluripotent capacity of vaginal fluids to seed different sites of the baby’s body. Transmission and colonization by these pioneer species may then modulate the succession that proceeds, influencing engraftment of later colonizers to each body site34. Major changes in the vaginal microbiota during pregnancy have been described35, although the changes in the last semester have not been deeply characterized. This begs the question of whether the vaginal microbiome becomes specifically primed during pregnancy to deliver key pioneer colonizers tailored towards multiple body sites of the infant. This hypothesis is supported by previous work demonstrating the by-phasic dynamics in gestational changes in which after decreasing diversity in the first two thirds of gestation, in the last gestational trimester diversity increases at the expense of Lactobacillus from week 24 of pregnancy until birth36; increase in vaginal diversity continues in the postpartum vaginal tract for up to 1 year following birth37.

This study provides solid evidence that deliberate, early microbial seeding can help naturalize the microbiome developmental trajectory of CS born infants. While overall trajectories do appear to head towards convergence over time, studies show that early perturbations during the crucial developmental window of very early life seem to have irreversible consequences38–41. Restoring natural exposures at birth may thus be one way to reduce the risk of CS-associated diseases such as obesity, asthma, allergies, and immune disfunctions. However, randomized clinical trials on large cohorts are needed to gain conclusive evidence for microbial restoration at birth improving health outcomes42. Moreover, in light of recent research showing that oral administration of maternal fecal microbes is also effective in restoring the microbiome in CS-delivered infants20, future research investigating the effects of exposure to both sources explicitly compared to either single source will help determine the best routes to restoring the neonate microbiome. In this study we exposed infants to freshly collected maternal vaginal/perineal microbes, but it is unknown how storage would alter the microbiota composition. More research is needed to determine whether it is optimum that they receive their own mother’s microbiome or achieve defined universal cocktails that can be used to restore neonates.

Limitations of study

This study is limited by the cohort size, particularly in countries outside of the United States, the follow up time of the first year of life, since any longer-term consequences of seeding were not assessed, and by the 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing, which excludes functional characterizations as well as fungi and viruses. Future studies capturing longer timeframes, larger and broader cultural and geographic representations, and additional data types are needed to gain a more understanding of how seeding affects the microbiome and ultimately the health of CS-delivered infants.

STAR * METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Dr. Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, mg.dominguez-bello@rutgers.edu

Materials Availability

DNA or samples that are available upon request, as collaboration, subject to availability.

Data and Code Availability

Sequence data have been deposited at European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) under study accession number ERP120105, ERP016173 and ERP120109. Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper. Source codes, tests and notebooks to generate the figures are available at https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human subjects

The study recruitment was conducted in the period 2017 to 2019, at participating centers in the mainland US, Puerto Rico, Chile, Spain, and Bolivia. Physician-assessed healthy mothers who were set to deliver vaginally or by scheduled CS were offered to participate in this study during a physician’s visit. Inclusion criteria included healthy, non-obese mothers with no pregnancy complications. Mothers delivering vaginally included GBS positive subjects who received antibiotics during labor. Mothers scheduled to have a CS were divided into two groups based on their willingness to have their newborns swabbed with the gauze: seeded CS (CS-seeded) and unseeded CS (CS). The mothers in the CS groups had intact amniotic membranes at the time of delivery. For the CS-seeded group, mothers had to have negative results for standard-of-care tests for Group B Streptococcus (GBS, standard test at 36 weeks by culturing) and STDs (including HIV and Chlamydia), no signs of vaginosis or viral infections as determined by their obstetrician, and a vaginal pH<4.5 at 1–2 h preceding the procedure. The infants from this group received swabbing of a gauze soaked with maternal vaginal fluids for microbial restoration at birth. No mock gauze was applied to the unseeded CS babies. All mothers received standard-of-care treatment, including preventive perinatal antibiotics (Beta lactams: mostly Cephalosporins or Penicillin) for mothers who underwent CS section or for vaginally delivering GBS positive mothers (Table 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards from New York University School of Medicine (S14–00377), University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras (1011–107) campus, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (180814027), and Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Spain (2015/0024), Universidad Mayor, Real y Pontificia de San Francisco Xavier de Chuquisaca, Bolivia (02/2014). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This research did not require authorization from the FDA or an equivalent regulatory organization.

METHOD DETAILS

Microbial restoration procedure

Restoration procedures were the same in all participating centers. Within the hour prior to the procedure, maternal vaginal pH was measured using a sterile swab and a paper pH strip (Fisher). Once the pH was confirmed to be <4.5, an 8×8 cm four-layered gauze (Fisherbrand Cat # 22028558) was folded like a fan, and then in half, inserted in a tampon applicator and wet with sterile saline solution using a sterile Pasteur pipette. The gauze was inserted in the maternal vagina for one hour. Immediately before the CS surgery started, the gauze was extracted and placed in a sterile collector and kept at room temperature. As soon as the baby was brought to the neonate lamp and within 1 minute after delivery, the infant was swabbed with the gauze, starting on the lips, followed by the face, thorax, arms, legs, genitals and anal region, and finally the back. The swabbing took approximately 15 seconds. The neonatologist then proceeded to perform the standard detailed examination of the newborn.

Sample collection and processing

Sampling with sterile swabs in different body sites took place within the first hours after birth in all babies (including the vaginal gauze exposed CS group, who were sampled after the gauze swabbing procedure), then at day 1–3, weekly for the first month and monthly up to the first year. Sampled body sites included oral mucosa, right arm region and feces of the baby, and the same sites of the mother plus nasal, right areola, vaginal swabs. All samples were transported to the laboratory with ice packs within two hours of collection and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Gauze samples for microbiota determination were obtained from one cm2 from the center of the gauze. Together with swabs and gauzes, 399 control blanks and 249 reagent blanks were included and processed.

Sequencing and data processing

DNA extraction, amplicon generation, and sequencing were performed as described in the protocols for the Earth Microbiome Project43,44. Briefly, DNA was from samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil HTP 96 Kit (http://www.earthmicrobiome.org/emp-standard-protocols/dna-extraction-protocol/), and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the 515f/806r primers and prepared for sequencing (http://press.igsb.anl.gov/earthmicrobiome/protocols-and-standards/16s/). Sequencing was performed at the University of Colorado Biofrontiers Sequencing Facility, New York University Genome Technology Center, or UC San Diego Institute for Genomic Medicine Genomics Facility using the Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq sequencing instrument. Raw reads were de-multiplexed and quality filtered using QIIME2 v2019.10 with default parameters45. Quality-filtered reads were clustered into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using deblur v1.1.046. A phylogenetic tree was constructed through insertion47 with the Greengenes v13_8 as a reference backbone48.

Data used from the human microbiome project (HMP) included 16S rRNA gene sequence data from 105 women (Supplementary Methods S14) identified based on metadata provided in the HMP16SData R package49. Sequences, which spanned the of V3-V5 region of 16S rRNA gene, were downloaded, trimmed to the corresponding 100nt of the V4 region generated in the current study, and processed as described above.

Bacterial source tracking

To estimate the sources of the microbial communities observed in each of the three infant groups at different body sites and time points, we used FEAST29, based on expectation-maximization (EM) estimation, for bacterial source tracking. Samples from each body site in the infants were designated as sinks, and samples collected within the first month after birth from the vagina, stool, skin, mouth and nose of the corresponding mother were tagged as sources. The analysis was performed on rarified count tables with 5000 reads per sample with 1000 EM iterations.

Alpha Diversity

Shannon Diversity was calculated on rarified count tables with 5000 reads/sample using QIIME2 v2019.1045. The birth mode effect over time in Shannon diversity was analyzed initially using a linear mixed-effect model and then using a novel longitudinal method, Bayesian Sparse Functional Principal Components Analysis (SFPCA)22. Generally, a functional principal components analysis is used to investigate longitudinal data with highly non-linear temporal trends50, and Bayesian SFPCA performs dimensionality reduction on longitudinal alpha diversity measurements to reveal changes in microbial diversity over time, estimating both mean trajectories, as well as subject-level variation around this mean. Bayesian SFPCA expresses repeated measurements from each baby in the form of a smooth function that represents the entire time course as a single observation, and then uses a reduced rank mixed-effects framework to handle scenarios where datapoints are collected at irregular and sparse time points. The final inference on birth mode effect is done based on the estimated weights that each baby receives on the first principal component function, which captures the different growth rates in alpha diversity among babies with different birth modes.

Beta Diversity and Convex Hull

The infant microbiome variability over time of infants for each birth mode were compared to the mothers through a calculation of the per subject convex hull volume from Principal Coordinates derived from unweighted UniFrac distances51. The convex hull is the volume produced by considering a set of points to define the outer surface of a shape (like stretching wrapping paper around those points), so a larger convex hull volume indicates greater variability across the set of samples around which the convex hull is built. The unweighted UniFrac distance was calculated on rarefied tables with 1000 reads/sample and dimensionality reduction on the distances was performed through Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) for each body site. Per subject convex hull volume from the individuals’ data points in each ordination using scipy v1.3.152. The resulting volumes were assessed by body-site pairwise for statistical significance between mothers and infants of different birth modes with a Bonferroni corrected Mann-Whitney rank test using scipy v1.3.152.

Dimensionality reduction

We used compositional tensor factorization (CTF) to produce a dimensionality reduction aware of the repeated measure structure of the longitudinal experimental design and the compositional nature of microbiome data23. To reduce sparsity data was split into two time periods being days 0–2 and 7–360 of life and subjects with more than two missing timepoints were removed. CTF was run on the filtered data through gemelli v0.0.6 (https://github.com/biocore/gemelli) on default parameters. The resulting ordinations first principal component (i.e. Axis 1) was plotted for each sample type across time. To evaluate the statistical significance, a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA)53 was performed on the CTF based Aitchison distances54 separately for each time point and sample type using scikit-bio v0.5.5. Bonferroni p-value correction was applied to each comparison with PERMANOVA to correct for multiple comparisons.

Effect Size Analysis

In order to calculate the relative effect size of all recorded metadata within the CTF ordinations, a stepwise redundancy analysis was performed (stepwise RDA). The stepwise analysis was performed on the first three principal components of the CTF sample ordination through the ordistep function in vegan v2.4–255. The ordiR2step function was run with 5000 permutation steps, with a permutation p-values limit of 0.1 and otherwise following the procedure of Falony et al.26.

Differential Abundance and Effectiveness Score

Differential abundance analysis was performed through Songbird at days 2, 30, and 180 on each infant body site (i.e. feces, mouth, and skin)25. Optimized model parameters were determined for each model with respect to the main factor of birth mode and the covariate of country by the cross-validation (CV) minimization. The models were then compared by a Q2-value defined as 1 – model CV / baseline CV. A positive Q2-value was observed for all models indicating good predictive accuracy (Supplementary Methods S16). Differentials were obtained with the reference class as vaginal and contrast variables as CS and CS-seeded, producing the columns log(CS/Vaginal) and log(CS-seeded/Vaginal). The differentials from Songbird in this contrast setup can give a rank of how much each ASV is associated with a contrast variable relative to the reference variable. For example, for log(CS/Vaginal), positive valued ASVs are more associated with a CS birth and negative values with vaginal birth. However, in order to describe the probability of association of a given ASV relative to all three groups (vaginal, CS, CS-seeded), the inverse additive log-ratio (alr) transformation56 was applied to the songbird differentials. We then defined a score for each microbe’s “seeding effectiveness” as a measure of efficacy of seeding. We defined the score as

where the score can range from zero to one, with zero indicating the least effective seeding and one indicating the most effective seeding. Effectively seeded microbes would be those shared by vaginal and CS-seeded infants. Effectively seeded microbes can also be associated with only Caesarean infants, indicating that seeded infants no longer contained that microbe after seeding. Poorly seeded microbes would be those shared between CS and CS-seeded infants. Poorly seeded microbes can also be associated only with Vaginal birth indicating that seeding did not graft that microbe effectively.

The class probabilities were plotted as a ternary plot and colored by their ‘seeding effectiveness’ score (Figure 1, 2, 3 c–e). The differentials for Vaginal vs. Caesarean born infants were plotted at the genus taxonomic level for the top and bottom 20% of ASVs based on the centered songbird differentials and colored by the mean ‘seeding effectiveness’ score (Figure 1, 2, 3 c–e).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Details on statistical tests, n numbers can be found in the figure legends and further details can be found in the method details for specific measurement.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Longitudinal sampling of mother-infant pairs, Related to STAR Methods. (a) Number of families, infants and samples from the current study. (b) Longitudinal sampling of infant samples by birth modes and body sites. Sampling with sterile swabs in different body sites took place within the first hour after birth in all babies, (including the vaginal gauze used to expose CS-born neonates) who were sampled within the hour after birth (after gauze swabbing of the CS-seeded babies), then at day 1–3, weekly for the first month, and monthly for up to the first year. Each row along y-axis is an individual baby. Each point represent a sample for one baby. The points are colored by birth modes, vaginal (blue), cesarean-seeded (green), and cesarean (red). On average, each baby contributed 18, 17, and 21 samples (across three body sites and multiple time points for the first year) for vaginal, cesarean, and cesarean-seed groups. (c) Longitudinal sampling of maternal samples by body sites within the first month after delivery. Each row along y-axis is an individual mom. On average each mom contributed 17 samples (across six body sites and multiple time points for the first month). (d) Distribution of number of reads per sample by different body sites in moms or babies Reagent blanks (blue), and field blanks (green) presentation were overplayed on each panel, and show much lower depth than the samples, indicating good overall quality of the sequences and lack of contamination. Dashed line marked the 5000 reads per sample position.

Figure S2. Pluripotential nature of perinatal vaginal microbiome, Related to Figure 5, Supplementary Methods S13–S14. (a) Number of ASVs shared between vaginal swabs and vaginal gauzes. Gauzes show higher ASVs richness than vaginal swabs. Proportions of bacterial vaginal ASVs shared with other body sites. (b) in HMP data of non-pregnant women (105 women), (c) in parturient mothers at the day of delivery from USA (53 mothers), Spain (24 mothers) and Chile (20 mothers). HMP data was reprocessed by extracting V4 sequences and analyzed using the same pipeline.

Figure S3. Bayesian Sparce Functional PCA (SFPCA) analyses on Shannon alpha diversity from 1 to 12 months of age, Related to STAR Methods. Bayesian Sparse Functional Principal Components Analysis (SFPCA) performed on Shannon alpha diversity across time did not differ by birth mode using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The rate of growth of the Shannon diversity after day 30 (y-axes) is shown across birth modes (x-axis) for fecal (left), oral (middle), and skin (right) samples.

Figure S4. Compositional Tensor Factorization identifies the partial restoration of microbiome among cesarean-seeded babies, Related to Figure 1,2, 3. PERMANOVA of Aitchison distances from Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) during the first year of life. (a) PERMANOVA test statistics and (b) Bonferroni corrected p-values are plotted across age in days (x-axes). PERMANOVA plots are colored by compared pairs, Caesarean vs. Vaginal, Caesarean-seeded vs. Vaginal, and Caesarean-seeded vs. Caesarean. (c) Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) in the USA cohort. CTF ordination plot as in Figure 1a but only with the 101 US infants shows the same trends as the whole dataset, with vaginally born and seeded babies clustering together and separately from Cesarean-born infants. Comparison of Vaginal (blue; n=62), Cesarean (red; n=23), Cesarean-seeded (green; n=16) with CTF first principal component (y-axes) of infant samples over age in days (x-axes); error bars show the standard error of the mean. There were not enough sequences after filtering the samples in the skin of Cesarean-seeded babies.

Supplementary Methods S1–S16

KEY RESOURCE TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Samples | ||

| Stool, mouth, and skin specimen from infants | This Study | |

| Stool, mouth, skin, vagina, nasal specimen from mothers | This Study | |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| DNeasy PowerSoil HTP 96 Kit | Qiagen | 12955-4 |

| illumine MiSeq/HiSeq sequencing PE150 | New York University Genome Technology Center, or UC San Diego Institute for Genomic Medicine Genomics Facility | - |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw sequencing data | European Bioinformatics Institute | ERP120105, ERP016173 and ERP120109 |

| Raw sequencing data and processed data | Qiita | Study 10894, 10249, and 1718 |

| Source codes, tests and notebooks to generate the figures | This study | https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 515f forward primer: GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA | EMP protocol | |

| 806r reverse primer: GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT | EMP protocol | |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Qiime2-2019.8 | Bolyen et al. (2019) | |

| FEAST | Shenhav et al. (2019) | https://github.com/ETaSky/FEAST.gitbranch:removewritingfiles |

| BayestTime | Jiang et al. (2020) | https://github.com/biocore/bayestime |

| Gemelli | Martino et al. (2020) | https://github.com/biocore/gemelli |

| stepwise-rda.R | This study | https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study |

| Songbird | Morton et al. (2019) | https://github.com/biocore/songbird |

Highlights.

Vaginal seeding of Cesarean born babies naturalizes their microbiota

Bacteria from multiple body sites compose the perinatal maternal vaginal microbiome

Bacteria typical in vaginal birth engraft different sites of Cesarean born babies

Context and Significance paragraph.

Cesarean birth alters the infant microbiota and is associated with increased risk of immune and metabolic disorders. We restored the natural microbial exposure of babies to their mothers’ birth canal fluids right after Cesarean birth, and found that perinatally, the maternal birth canal contains very high proportions of bacteria typical of other body sites, and engraftment of these maternal bacteria normalizes microbiota development in different infant sites. In the context of risks and benefits of Cesarean procedures, normalizing the infant microbiota from birth might mitigate the collateral effects of missing colonization by important early bacteria, and reduce the increased risk to immune and metabolic diseases associated with Cesarean birth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the C&D Research Fund, Emch Fund for human microbiome studies, and CIFAR FS20-078 #125869 (M.G.D.B), the Chilean CONICYT PIA/ANILLO Grant ACT172097, the Chilean SOCHIPE Project 022019 (P.H.), the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2019-0350), the Emerald Foundation, the NIH Pioneer award (1DP1AT010885), the National Institute of Justice (2016-DN-BX-4194), the San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center (NIDDK 1P30DK120515), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (20175015), and by in-kind donations from Illumina, MoBio/QIAGEN, and the Center for Microbiome Innovation at UC San Diego (R.K.). We acknowledge the contribution of students, technicians and MDs who participated in obtaining the samples and preparing the metadata: Sukhleen Bedi, Allison Horan, and Yi Cai from NYUSM; Noraliz Garcia, Hebe Rosado, Selena Marie Rodriguez, and Keimari Mendez from UPR; Maricruz Mojica, Magaly Magariños and Myriam Corrales from Universidad Real y Pontificia San Francisco Javier de Chuquisaca, and the University Hospital in Sucre, Bolivia; Mauricio Sandoval, Marlene Ortiz, Carolina Serrano from the PUC. We thank Gail Ackermann for her help curating the metadata and uploading sequences to Qiita, and James T. Morton for providing advice in the use of Songbird differentials.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

New York University has a U.S. patent (number 10357521) on behalf of M.G.D.B., related to methods for restoring the microbiota of newborns.

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY STATEMENT

We worked to ensure that the study questionnaires were prepared in an inclusive way. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as an underrepresented ethnic minority in science. The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/xxx

DATA AVAILABILITY

Accession codes. European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI): sequence data have been deposited under study accession number ERP120105, ERP016173 and ERP120109.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper. Source codes, tests and notebooks to generate the figures are available at https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study

REFERENCES

- 1.Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL, and Blumberg RS (2016). How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science (New York, N.Y.) 352, 539–544. 10.1126/science.aad9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Nabhani Z, and Eberl G (2020). Imprinting of the immune system by the microbiota early in life. Mucosal Immunol 13, 183–189. 10.1038/s41385-020-0257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, and Knight R (2010). Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 11971–11975. 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, A DL, Wu F, Perez-Perez GI, Chen Y, et al. (2016). Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med 8, 343ra382. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yassour M, Vatanen T, Siljander H, Hamalainen AM, Harkonen T, Ryhanen SJ, Franzosa EA, Vlamakis H, Huttenhower C, Gevers D, et al. (2016). Natural history of the infant gut microbiome and impact of antibiotic treatment on bacterial strain diversity and stability. Sci Transl Med 8, 343ra381. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shao Y, Forster SC, Tsaliki E, Vervier K, Strang A, Simpson N, Kumar N, Stares MD, Rodger A, Brocklehurst P, et al. (2019). Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature 574, 117–121. 10.1038/s41586-019-1560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, Hutchinson DS, Smith DP, Wong MC, Ross MC, Lloyd RE, Doddapaneni H, Metcalf GA, et al. (2018). Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 562, 583–588. 10.1038/s41586-018-0617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Protonotariou E, Boutsikou T, Makrakis E, Sarandakou A, and Creatsas G (2005). The influence of the mode of delivery on circulating cytokine concentrations in the perinatal period. Early Hum Dev 81, 387–392. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokholm J, Blaser MJ, Thorsen J, Rasmussen MA, Waage J, Vinding RK, Schoos AM, Kunoe A, Fink NR, Chawes BL, et al. (2018). Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of asthma in childhood. Nat Commun 9, 141. 10.1038/s41467-017-02573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen V, Moller S, Jensen PB, Moller FT, and Green A (2020). Caesarean Delivery and Risk of Chronic Inflammatory Diseases (Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Coeliac Disease, and Diabetes Mellitus): A Population Based Registry Study of 2,699,479 Births in Denmark During 1973–2016. Clin Epidemiol 12, 287–293. 10.2147/CLEP.S229056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blustein J, Attina T, Liu M, Ryan AM, Cox LM, Blaser MJ, and Trasande L (2013). Association of caesarean delivery with child adiposity from age 6 weeks to 15 years. Int J Obes (Lond) 37, 900–906. 10.1038/ijo.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ardic C, Usta O, Omar E, Yildiz C, and Memis E (2020). Caesarean delivery increases the risk of overweight or obesity in 2-year-old children. J Obstet Gynaecol, 1–6. 10.1080/01443615.2020.1803236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, et al. (2014). Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 158, 705–721. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez KA 2nd, Devlin JC, Lacher CR, Yin Y, Cai Y, Wang J, and Dominguez-Bello MG (2017). Increased weight gain by C-section: Functional significance of the primordial microbiome. Sci Adv 3, eaao1874. 10.1126/sciadv.aao1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, Glickman JN, Siebert R, Baron RM, Kasper DL, and Blumberg RS (2012). Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science 336, 489–493. 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livanos AE, Greiner TU, Vangay P, Pathmasiri W, Stewart D, McRitchie S, Li H, Chung J, Sohn J, Kim S, et al. (2016). Antibiotic-mediated gut microbiome perturbation accelerates development of type 1 diabetes in mice. Nat Microbiol 1, 16140. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moya-Perez A, Luczynski P, Renes IB, Wang S, Borre Y, Anthony Ryan C, Knol J, Stanton C, Dinan TG, and Cryan JF (2017). Intervention strategies for cesarean section-induced alterations in the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Nutr Rev 75, 225–240. 10.1093/nutrit/nuw069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braniste V, Al-Asmakh M, Kowal C, Anuar F, Abbaspour A, Toth M, Korecka A, Bakocevic N, Ng LG, Kundu P, et al. (2014). The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med 6, 263ra158. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominguez-Bello MG, De Jesus-Laboy KM, Shen N, Cox LM, Amir A, Gonzalez A, Bokulich NA, Song SJ, Hoashi M, Rivera-Vinas JI, et al. (2016). Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nat Med 22, 250–253. 10.1038/nm.4039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korpela K, Helve O, Kolho KL, Saisto T, Skogberg K, Dikareva E, Stefanovic V, Salonen A, Andersson S, and de Vos WM (2020). Maternal Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Cesarean-Born Infants Rapidly Restores Normal Gut Microbial Development: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Cell 183, 324–334 e325. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakobsson HE, Abrahamsson TR, Jenmalm MC, Harris K, Quince C, Jernberg C, Bjorksten B, Engstrand L, and Andersson AF (2014). Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut 63, 559–566. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang L, Zhong Y, Elrod C, Natarajan L, Knight R, and Thompson WK (2020). BayesTime: Bayesian Functional Principal Components for Sparse Longitudinal Data. Arxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martino C, Shenhav L, Marotz CA, Armstrong G, McDonald D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Morton JT, Jiang L, Dominguez-Bello MG, Swafford AD, et al. (2020). Context-aware dimensionality reduction deconvolutes gut microbial community dynamics. Nature Biotechnology, 1–4. 10.1038/s41587-020-0660-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gloor GB, Macklaim JM, Pawlowsky-Glahn V, and Egozcue JJ (2017). Microbiome Datasets Are Compositional: And This Is Not Optional. Front Microbiol 8, 2224. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morton JT, Marotz C, Washburne A, Silverman J, Zaramela LS, Edlund A, Zengler K, and Knight R (2019). Establishing microbial composition measurement standards with reference frames. Nat Commun 10, 2719. 10.1038/s41467-019-10656-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Darzi Y, Faust K, Kurilshikov A, Bonder MJ, Valles-Colomer M, Vandeputte D, et al. (2016). Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 352, 560–564. 10.1126/science.aad3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halfvarson J, Brislawn CJ, Lamendella R, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Walters WA, Bramer LM, D’Amato M, Bonfiglio F, McDonald D, Gonzalez A, et al. (2017). Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 2, 17004. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaneveld JR, McMinds R, and Vega Thurber R (2017). Stress and stability: applying the Anna Karenina principle to animal microbiomes. Nat Microbiol 2, 17121. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenhav L, Thompson M, Joseph TA, Briscoe L, Furman O, Bogumil D, Mizrahi I, Pe’er I, and Halperin E (2019). FEAST: fast expectation-maximization for microbial source tracking. Nat Methods 16, 627–632. 10.1038/s41592-019-0431-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azad MB, Konya T, Maughan H, Guttman DS, Field CJ, Chari RS, Sears MR, Becker AB, Scott JA, Kozyrskyj AL, and Investigators CS (2013). Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ 185, 385–394. 10.1503/cmaj.121189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korpela K, Costea P, Coelho LP, Kandels-Lewis S, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, Segata N, and Bork P (2018). Selective maternal seeding and environment shape the human gut microbiome. Genome Res 28, 561–568. 10.1101/gr.233940.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, Asnicar F, Gorfer V, Fedi S, Armanini F, Truong DT, Manara S, Zolfo M, et al. (2018). Mother-to-Infant Microbial Transmission from Different Body Sites Shapes the Developing Infant Gut Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 24, 133–145 e135. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helve O, Korpela K, Kolho K-L, Saisto T, Skogberg K, Dikareva E, Stefanovic V, Salonen A, de Vos WM, and Andersson S (2019). 2843. Maternal Fecal Transplantation to Infants Born by Cesarean Section: Safety and Feasibility. Open Forum Infect Dis 6, S68–S68. 10.1093/ofid/ofz359.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez I, Maldonado-Gomez MX, Gomes-Neto JC, Kittana H, Ding H, Schmaltz R, Joglekar P, Cardona RJ, Marsteller NL, Kembel SW, et al. (2018). Experimental evaluation of the importance of colonization history in early-life gut microbiota assembly. Elife 7. 10.7554/eLife.36521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stout MJ, Zhou Y, Wylie KM, Tarr PI, Macones GA, and Tuuli MG (2017). Early pregnancy vaginal microbiome trends and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217, 356 e351–356 e318. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasmussen MA, Thorsen J, Dominguez-Bello MG, Blaser MJ, Mortensen MS, Brejnrod AD, Shah SA, Hjelmsø MH, Lehtimäki J, Trivedi U, et al. (2020). Ecological succession in the vaginal microbiota during pregnancy and birth. The ISME Journal 14, 2325–2335. 10.1038/s41396-020-0686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, Sun CL, Goltsman DSA, Wong RJ, Shaw G, et al. (2015). Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 11060. 10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Zera CA, Edwards JW, Oken E, Weiss ST, and Gillman MW (2012). Delivery by caesarean section and risk of obesity in preschool age children: a prospective cohort study. Arch Dis Child 97, 610–616. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pistiner M, Gold DR, Abdulkerim H, Hoffman E, and Celedon JC (2008). Birth by cesarean section, allergic rhinitis, and allergic sensitization among children with a parental history of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122, 274–279. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sevelsted A, Stokholm J, Bonnelykke K, and Bisgaard H (2015). Cesarean section and chronic immune disorders. Pediatrics 135, e92–98. 10.1542/peds.2014-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thavagnanam S, Fleming J, Bromley A, Shields MD, and Cardwell CR (2008). A meta-analysis of the association between Caesarean section and childhood asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 38, 629–633. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mueller NT, Dominguez-Bello MG, Appel LJ, and Hourigan SK (2019). ‘Vaginal seeding’ after a caesarean section provides benefits to newborn children: FOR: Does exposing caesarean-delivered newborns to the vaginal microbiome affect their chronic disease risk? The critical need for trials of ‘vaginal seeding’ during caesarean section. BJOG. 10.1111/1471-0528.15979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, et al. (2012). Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 6, 1621–1624. 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson LR, Sanders JG, McDonald D, Amir A, Ladau J, Locey KJ, Prill RJ, Tripathi A, Gibbons SM, Ackermann G, et al. (2017). A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463. 10.1038/nature24621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, Alexander H, Alm EJ, Arumugam M, Asnicar F, et al. (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37, 852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amir A, McDonald D, Navas-Molina JA, Kopylova E, Morton JT, Zech Xu Z, Kightley EP, Thompson LR, Hyde ER, Gonzalez A, and Knight R (2017). Deblur Rapidly Resolves Single-Nucleotide Community Sequence Patterns. mSystems 2. 10.1128/mSystems.00191-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen S, McDonald D, Gonzalez A, Navas-Molina JA, Jiang L, Xu ZZ, Winker K, Kado DM, Orwoll E, Manary M, et al. (2018). Phylogenetic Placement of Exact Amplicon Sequences Improves Associations with Clinical Information. mSystems 3. 10.1128/mSystems.00021-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, Andersen GL, Knight R, and Hugenholtz P (2012). An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J 6, 610–618. 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiffer L, Azhar R, Shepherd L, Ramos M, Geistlinger L, Huttenhower C, Dowd JB, Segata N, and Waldron L (2019). HMP16SData: Efficient Access to the Human Microbiome Project Through Bioconductor. Am J Epidemiol 188, 1023–1026. 10.1093/aje/kwz006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James GM, Hastie TJ, and Sugar CA (2000). Principal component models for sparse functional data. Biometrika 87, 587–602. DOI 10.1093/biomet/87.3.587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lozupone C, and Knight R (2005). UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 8228–8235. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Virtanen P, Gommers R, Oliphant TE, Haberland M, Reddy T, Cournapeau D, Burovski E, Peterson P, Weckesser W, Bright J, et al. (2020). SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 17, 261–272. 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson MJ (2017). Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA). In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, pp. 1–15. 10.1002/9781118445112.stat07841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aitchison J (1983). Principal Component Analysis of Compositional Data. Biometrika 70, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jari O, Blanchet FG, Michael F, Roeland K, Pierre L, Dan M, Peter RM, Hara RBO, Gavin LS, Peter S, et al. (2019). vegan: Community Ecology Package.

- 56.Aitchison J (1982). The Statistical-Analysis of Compositional Data. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 44, 139–177. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Longitudinal sampling of mother-infant pairs, Related to STAR Methods. (a) Number of families, infants and samples from the current study. (b) Longitudinal sampling of infant samples by birth modes and body sites. Sampling with sterile swabs in different body sites took place within the first hour after birth in all babies, (including the vaginal gauze used to expose CS-born neonates) who were sampled within the hour after birth (after gauze swabbing of the CS-seeded babies), then at day 1–3, weekly for the first month, and monthly for up to the first year. Each row along y-axis is an individual baby. Each point represent a sample for one baby. The points are colored by birth modes, vaginal (blue), cesarean-seeded (green), and cesarean (red). On average, each baby contributed 18, 17, and 21 samples (across three body sites and multiple time points for the first year) for vaginal, cesarean, and cesarean-seed groups. (c) Longitudinal sampling of maternal samples by body sites within the first month after delivery. Each row along y-axis is an individual mom. On average each mom contributed 17 samples (across six body sites and multiple time points for the first month). (d) Distribution of number of reads per sample by different body sites in moms or babies Reagent blanks (blue), and field blanks (green) presentation were overplayed on each panel, and show much lower depth than the samples, indicating good overall quality of the sequences and lack of contamination. Dashed line marked the 5000 reads per sample position.

Figure S2. Pluripotential nature of perinatal vaginal microbiome, Related to Figure 5, Supplementary Methods S13–S14. (a) Number of ASVs shared between vaginal swabs and vaginal gauzes. Gauzes show higher ASVs richness than vaginal swabs. Proportions of bacterial vaginal ASVs shared with other body sites. (b) in HMP data of non-pregnant women (105 women), (c) in parturient mothers at the day of delivery from USA (53 mothers), Spain (24 mothers) and Chile (20 mothers). HMP data was reprocessed by extracting V4 sequences and analyzed using the same pipeline.

Figure S3. Bayesian Sparce Functional PCA (SFPCA) analyses on Shannon alpha diversity from 1 to 12 months of age, Related to STAR Methods. Bayesian Sparse Functional Principal Components Analysis (SFPCA) performed on Shannon alpha diversity across time did not differ by birth mode using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The rate of growth of the Shannon diversity after day 30 (y-axes) is shown across birth modes (x-axis) for fecal (left), oral (middle), and skin (right) samples.

Figure S4. Compositional Tensor Factorization identifies the partial restoration of microbiome among cesarean-seeded babies, Related to Figure 1,2, 3. PERMANOVA of Aitchison distances from Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) during the first year of life. (a) PERMANOVA test statistics and (b) Bonferroni corrected p-values are plotted across age in days (x-axes). PERMANOVA plots are colored by compared pairs, Caesarean vs. Vaginal, Caesarean-seeded vs. Vaginal, and Caesarean-seeded vs. Caesarean. (c) Compositional Tensor Factorization (CTF) in the USA cohort. CTF ordination plot as in Figure 1a but only with the 101 US infants shows the same trends as the whole dataset, with vaginally born and seeded babies clustering together and separately from Cesarean-born infants. Comparison of Vaginal (blue; n=62), Cesarean (red; n=23), Cesarean-seeded (green; n=16) with CTF first principal component (y-axes) of infant samples over age in days (x-axes); error bars show the standard error of the mean. There were not enough sequences after filtering the samples in the skin of Cesarean-seeded babies.

Supplementary Methods S1–S16

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data have been deposited at European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) under study accession number ERP120105, ERP016173 and ERP120109. Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper. Source codes, tests and notebooks to generate the figures are available at https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study.

Accession codes. European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI): sequence data have been deposited under study accession number ERP120105, ERP016173 and ERP120109.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper. Source codes, tests and notebooks to generate the figures are available at https://github.com/knightlab-analyses/seeding-study