Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of germline findings in cancers lacking hereditary testing guidelines?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study including records from 34 642 patients, approximately 7% of patients with cancer harbored pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants. The prevalence of pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline findings was highest in bladder and lung cancers.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that paired tumor/normal sequencing has the potential added benefit of identifying germline findings, especially in cancer types, such as bladder and lung, in which germline testing may not be indicated without a suspicious family history of cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Germline testing guidelines are suggested for specific disease types or a family history of cancer, yet alterations are found in cancer types in which germline testing is not routinely indicated. The clinical role of identifying germline variants in these populations is valuable to patients and their at-risk relatives.

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence of germline findings in patients undergoing tumor/normal matched sequencing among cancer types lacking guidelines.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cross-sectional study took place on August 18, 2021, and included data from deidentified records of patients tested, using the Tempus xT tumor/normal matched approach from November 2017 to August 2021. Records included in this study were from 34 642 patients treated in geographically diverse oncology practices in the US with a diagnosis of any of the following cancers: bladder, brain, lung, esophagus, cholangiocarcinoma, head and neck, breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, endometrial, and colorectal.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The rate of germline findings (ie, single-nucleotide variants and small insertions or deletions) detected in 50 reportable hereditary cancer genes was calculated for cancer types lacking guidelines for germline testing (bladder, brain, lung, esophagus, cholangiocarcinoma, and head and neck) and cancer types for which germline testing is frequently performed (breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, endometrial, and colorectal). Same-gene second somatic hits were assessed to provide a comprehensive assessment on genomic drivers.

Results

Of 34 642 patients, 18 888 were female (54.5%); of 27 498 patients whose age at diagnosis was known, mean (SD) age was 62.23 (3.36) years. A total of 2534 of 34 642 patients (7.3%) harbored pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants. Within the tumor types lacking testing guidelines, germline mutations were at 6.6% (79/1188) in bladder cancer and 5.8% (448/7668) in lung cancer.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study may present the largest retrospective analysis to date of deidentified real-world data from patients diagnosed with advanced cancer with tumor/normal matched sequencing data and the prevalence of pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants in cancer types lacking hereditary cancer testing guidelines. The findings suggest there may be clinical implications for patients and their at-risk family members in cancers for which germline assessment primarily based on the cancer diagnosis is rarely obtained.

This cross-sectional study examines the prevalence of germline findings in patients undergoing tumor/normal matched sequencing among cancer types lacking guidelines.

Introduction

Tumor molecular profiling via next-generation sequencing to identify genomic drivers is now commonly used in guiding treatment selection in clinical practice for patients with advanced cancer.1,2,3 Numerous studies have demonstrated the benefit of biomarker-based personalized cancer treatment strategies.4,5,6,7 Many of the sequencing platforms available today run tumor-only sequencing, which can result in variant miscategorization in 28% of the cases.8 In contrast, a tumor/normal (T/N) matched next-generation sequencing approach uses both tumor tissue and the patient’s own blood or saliva for an accurate and enhanced variant categorization, including the ability to differentiate somatic and germline findings. Although historically inherited germline alterations were detected on large next-generation sequencing panels, the need to distinguish between somatic vs germline variants did not impact therapy selection.

This status changed in 2014 when the US Food and Drug Administration approved the poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib for patients harboring germline BRCA1/2 variants.9 Since then, PARP inhibitor therapies have been approved in other tumor types in association with other heritable variants in germline genes along the homologous recombination repair pathway, and several other DNA damage response modulators have gone into clinical development. Studies have also now been opened to somatic variants for the assessment of PARP inhibitors. The importance of germline findings has increased in recent years as a number of germline alterations have become associated with therapeutic implications in patients with different cancers.10,11 This increase has affected the management of treatment in patients in different aspects, including the development of novel therapeutics that target different germline alterations, type of surgery or chemotherapy, and eligibility for clinical trials.12,13

Although germline testing for patients with ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, breast, colorectal, and endometrial cancer has been recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, guideline recommendations in many other cancer types are lacking.14,15,16 Several studies have evaluated the prevalence of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) germline alterations in patients with cancer lacking guideline recommendations.12,17,18,19 These reports can vary based on the size of the next-generation sequencing gene panel used and cancer types included. One such study reported that 1 in 8 patients with cancer may have a P/LP germline variant and approximately 50% of these patients could be missed by a guideline-based approach where genetic testing is offered based on suggestive family histories and other factors defined in the guidelines.12 Therefore, a T/N matched sequencing approach may be beneficial compared with a tumor-only approach to identify P/LP germline variants. A T/N sequencing approach may have clinical implications for both the patient and their at-risk family members, resulting in the opportunity for a more comprehensive germline test, genetic counseling, and risk-stratified intervention.

In the present study, we report on the prevalence of germline alterations in a cohort of 34 642 real-world, T/N-matched patients with cancer; to our knowledge, this is the largest study to date. We specifically included cancer types that currently lack germline testing guidelines, including bladder, brain, lung, esophagus, cholangiocarcinoma, and head and neck cancers, as well as cancer types that frequently undergo germline testing based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment guidelines,15 including breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, endometrial, and colorectal cancers. In addition, we examined same-gene second somatic hits to provide a comprehensive view of the potential genomic drivers in the tumor. We evaluated whether paired T/N sequencing has the potential added benefit of identifying germline findings, especially in cancer types where germline testing guidelines are lacking.

Methods

This report followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies. All analyses were performed using deidentified data; the study was approved by a central institutional review board (Advarra Inc), which determined that the project was exempt from institutional review board oversight and the requirement for informed consent owing to the deidentified nature of the data.

Tissue Assay

This targeted 648 gene next-generation sequencing panel is a laboratory developed test (LDT) that detects single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), indels, and copy number variants, as well as chromosomal rearrangements in 22 genes with high sensitivity and specificity.20 Germline findings were limited to SNVs and small insertions or deletions. The incidental germline panel used (Tempus xT, Tempus Inc) is not a validated germline panel.

Cohort Selection

We retrospectively analyzed next-generation sequencing data from deidentified records of 34 642 patients clinically tested with the Tempus xT T/N-matched LDT assay. Demographic characteristics, including sex, age, and race and ethnicity, were collected. Reporting of race was not required. Race and ethnicity data are routinely collected on the requisition forms for clinical testing; this is a free-response text box that is further categorized during data abstraction of the requisition forms.

Samples for sequencing were derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue and normal matched specimens (blood or saliva).8,20,21 Analyses took place August 18, 2021, and included patient records sequenced from November 2017 to August 2021.

Statistical Analysis

Deidentified records from patients with primary cancer sites of bladder, brain, cholangiocarcinoma, esophageal, lung, head and neck, breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, endometrial, or colorectal cancer were retrospectively identified from the Tempus Inc clinicogenomic database. Records were included if the patient had data for at least 1 Tempus xT T/N-matched assay, and all available Tempus xT T/N-matched assays per patient were included in analyses.

Detection of any P/LP germline findings (ie, SNVs and small insertions and deletions) in 50 hereditary cancer genes (eTable 1 in the Supplement) was queried across all available Tempus xT T/N-matched LDT assays per patient. The gene list included 50 genes related to hereditary cancer syndromes and was based on recommendations for the reporting of secondary findings by the American College of Medical Genetics, genes included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment guidelines, and other literature16,22 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The prevalence of germline findings among the 50 genes was reported for each cancer type, as well as across the cancer types with and lacking germline testing guidelines. Using the same Tempus xT T/N-matched LDT assays per patient, second somatic hits were reported as any P/LP somatic findings (ie, SNVs and small insertions/deletions) and/or copy number losses (CNLs) within the same genes as P/LP germline findings for a given individual. Demographic and clinical characteristics are reported as number (percentage). Analyses were performed in R, version 4.0.4.23

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Matched T/N records were analyzed from a total of 34 642 patients, including 18 888 females (54.5%) and 15 678 males (45.3%). Of 27 498 patients whose age at diagnosis was known, mean (SD) age was 62.23 (3.36) years (Table 1). More females were expected in the cohort with germline testing guidelines (12 807 of 20 604 [62.2%]) than the cohort lacking guidelines (6081 of 14 038 [43.3%]), because tumor types with guidelines included ovarian, endometrial, and breast. In all tumor types, most diagnoses were made when patients were older than 50 years (23 122 [66.7%]). However, individuals with tumor types with germline testing guidelines were more likely to receive a diagnosis before age 50 years (2825 [14.2%]) in comparison with those lacking guidelines (1551 [11.0%]) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Self-reported race and ethnicity distribution included American Indian or Alaska Native (84 [0.2%]), Asian (816 [2.4%]), Black or African American (2664 [7.7%]), Hispanic or Latino (1546 [4.5%]), Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (25 [<1%]), and White (17 422 [50.3%]). Tumor types were grouped into either lacking guidelines or guidelines available categories. The lacking guidelines group included cancer types for which germline testing may not be indicated without a suspicious family history of cancer, including bladder, brain, lung, esophagus, cholangiocarcinoma, and head and neck cancers. The guidelines available group included cancer types that frequently undergo germline testing, including breast, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, endometrial, and colorectal cancers.

Table 1. Cohort Distribution of Race and Ethnicity, Sex, Age, and Tumor Type.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 34 642) | Lacking guidelines (n = 14 038) | Guidelines available (n = 20 604) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 888 (54.5) | 6081 (43.3) | 12 807 (62) |

| Male | 15 678 (45.3) | 7934 (56.5) | 7744 (37.6) |

| Unknown | 76 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) | 53 (0.3) |

| Racea | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 84 (0.2) | 23 (0.2) | 61 (0.3) |

| Asian | 816 (2.4) | 335 (2.4) | 481 (2.3) |

| Black or African American | 2664 (7.7) | 924 (6.6) | 1740 (8.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 25 (<0.1) | 9 (<0.1) | 16 (<0.1) |

| White | 17 422 (50.3) | 7488 (53.3) | 9934 (48.2) |

| Other | 774 (2.2) | 279 (2.0) | 495 (2.4) |

| Unknown | 12 857 (37.1) | 4980 (35.5) | 7877 (38.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1546 (4.5) | 485 (3.5) | 1061 (5.1) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 9360 (27.0) | 4196 (29.9) | 5164 (25.1) |

| Unknown | 23 736 (68.5) | 9357 (66.7) | 14 379 (69.8) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| <50 | 4376 (12.6) | 1551 (11.0) | 2825 (14.2) |

| ≥50 | 23 122 (66.7) | 10 274 (73.2) | 12 848 (62.4) |

| Unknown | 7144 (20.6) | 2213 (15.8) | 4931 (23.9) |

| Tumor type | |||

| Breast | 4581 (13.2) | NA | 4581 (22.2) |

| Colorectal | 5303 (15.3) | NA | 5303 (25.7) |

| Endometrial | 1542 (4.5) | NA | 1542 (7.5) |

| Ovarian | 2756 (8.0) | NA | 2756 (13.4) |

| Pancreas | 3535 (10.2) | NA | 3535 (17.2) |

| Prostate | 2887 (8.3) | NA | 2887 (14.0) |

| Esophagus | 747 (2.2) | 747 (5.3) | NA |

| Head and Neck | 1218 (3.5) | 1218 (8.7) | NA |

| Lung | 7668 (22.1) | 7668 (54.6) | NA |

| Bladder | 1188 (3.4) | 1188 (8.5) | NA |

| Brain | 2377 (6.9) | 2377 (16.9) | NA |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 840 (2.4) | 840 (6.0) | NA |

| P/LP germline variant | 2534 (7.3) | 759 (5.4) | 1775 (8.6) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; P/LP, pathogenic/likely pathogenic.

Race and ethnicity are a free response text box that is further categorized during data abstraction of requisition forms.

Variants Detected

Among the 34 642 patients in this analysis, 2534 (7.3%) harbored P/LP germline variants. Within this subset of patients, 759 (5.4%) with tumor types lacking testing guidelines and 1775 (8.6%) with tumor types with testing guidelines had P/LP germline variants. Of the cancer types lacking guidelines, the highest prevalence of P/LP germline variants was noted with bladder (79 of 1188 [6.6%]) and lung (448 of 7668 [5.8%]) cancers. In comparison, the prevalence of P/LP germline variants that have established germline testing guidelines was 10.8% (494 of 4581) for breast cancer and 13.8% (380 of 2756) for ovarian cancers.

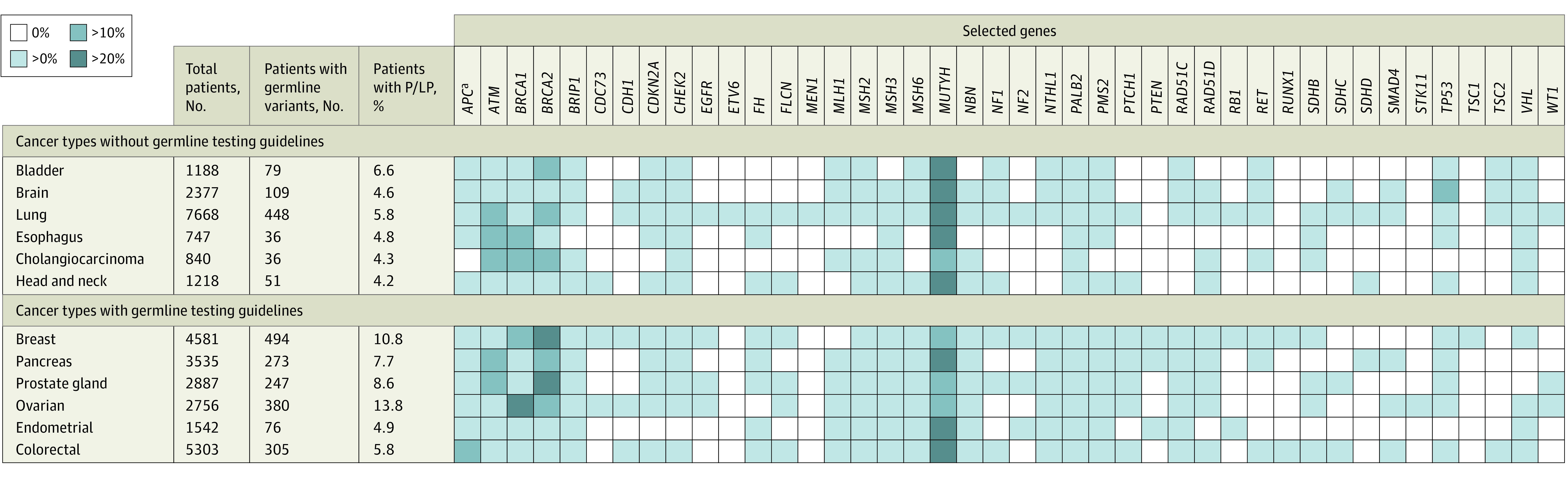

Figure 1 represents the percentage of patients with P/LP germline variants in 50 genes for each tumor type. Genes without variants across all cancer types were excluded. Patients with at least 1 P/LP germline variant in MUTYH, MSH3, and NTHL1 were included in the analysis (4 patients carried 2 P/LP germline variants in MUTYH and 1 patient carried 2 P/LP variants in MSH3). Monoallelic MUTYH was the most common germline finding across most tumor types. Only resistance alterations in EGFR (p.T790M, p.L792H, p.C797G, p.C797S) are reported. The Ashkenazi Jewish founder variant p.I1307K was the most frequent alteration in APC.

Figure 1. Percentage of Patients With Germline Variants of the Total Patients With Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic (P/LP) Germline Variants.

Heat map of the percentage of patients with P/LP germline variants for all tumor types, excluding genes without variants. Monoallelic carriers of MUTYH, MSH3, and NTHL1 were included (4 patients carried 2 P/LP germline variants in MUTYH and 1 patient carried 2 P/LP variants in MSH3). Only resistance alterations in EGFR are reported.

aAshkenazi Jewish founder variant p.I1307K was the most frequent variant in APC.

Among all tumor types, genes involved in DNA repair (ATM and BRCA1/2) were the most prevalent genes with clinically actionable germline variants detected. BRCA1/2 variants were anticipated in breast, ovarian, pancreas, and prostate tumors. The ATM P/LP germline variants were detected in lung, esophageal, and cholangiocarcinoma cancers. Excluding MUTYH, ATM exhibited the highest prevalence among all genes in this analysis. Ovarian cancer harbored BRCA1 variants most frequently (142 [37.4%]), followed by breast (92 [18.6%]) and esophageal (5 [13.9%]) cancer in more than 10% of patients with any P/LP germline alterations. Patients with bladder and lung cancer were found to carry BRCA2 variants. In cholangiocarcinoma, both BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants were detected in more than 10% of patients with P/LP germline alterations. In brain tumors, TP53 was highly prevalent.

Clinical Implications

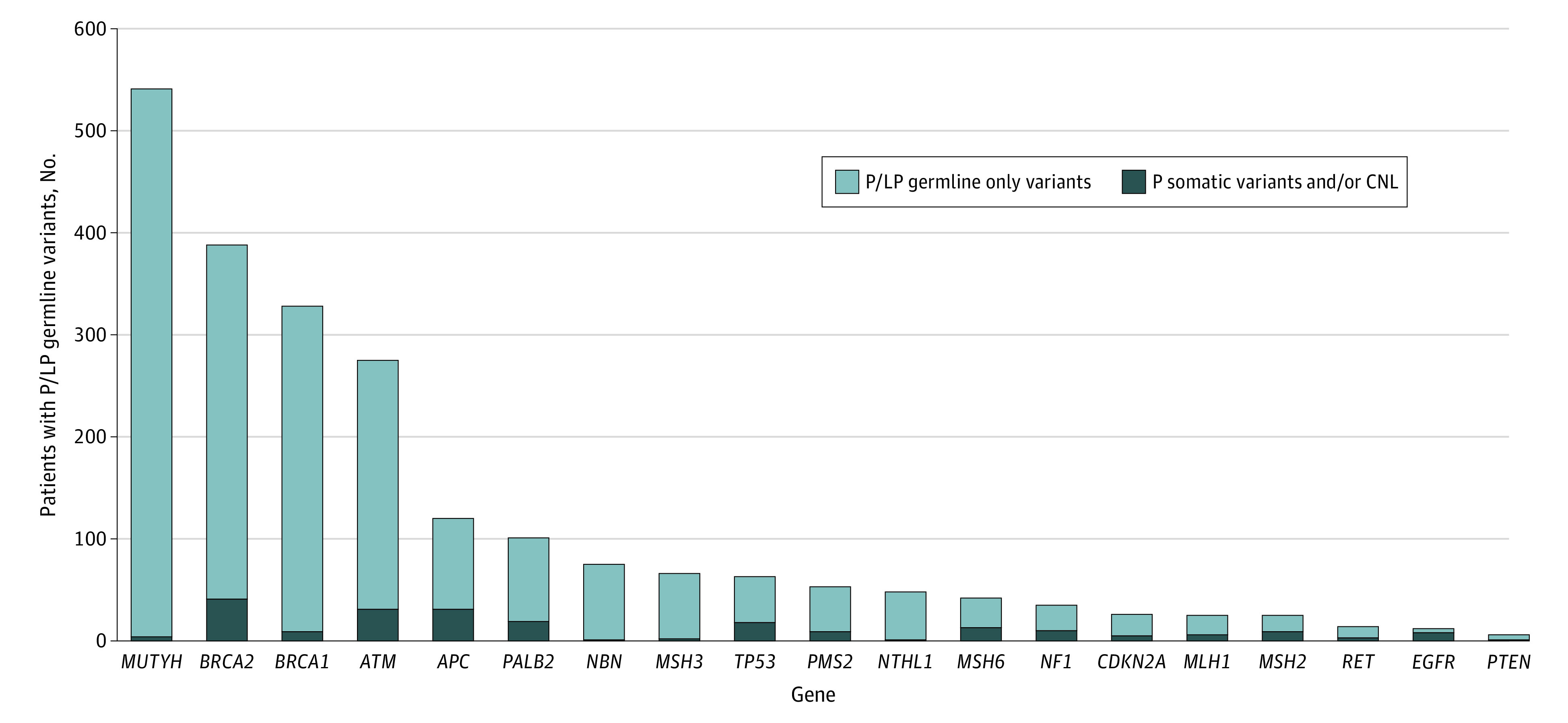

Figure 2 depicts the number of patients with a P/LP germline variant and any pathogenic somatic variant and/or CNL, referred to as a second somatic hit, in the same gene across all cancer types. A total of 220 patients had a pathogenic somatic variant and/or CNL in addition to a P/LP germline variant in the same gene across all cancer types, representing 8.7% (220 of 2534) of cases with a P/LP germline variant also harboring a somatic alteration of any type in the same gene.

Figure 2. Patients With a Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic (P/LP) Germline Variant and Any Pathogenic (P) Somatic Variant and/or Copy Number Loss (CNL) in the Same Gene Across All Cancer Types.

As the y-axis is the number of patients with any germline finding, the top of the bar represents the total number of patients with a germline finding in the respective gene. Light and dark blue bars are mutually exclusive.

Across all tumor types, the highest proportion of second somatic hits was observed in the following genes: EGFR, 66.7% (8 of 12); MSH2, 36.0% (9 of 25); MSH6, 31.0% (13 of 42); NF1, 28.6% (10 of 35); and TP53, 28.6% (18 of 63). Table 2 reports the percentage of patients with a pathogenic somatic variant and a P/LP germline variant and/or CNL in the same gene. In lung cancer, TP53 was the most prevalent gene harboring P/LP germline variants with a second somatic hit; 37.5% (3 of 8) had a P/LP germline variant in TP53 with a second somatic variant (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Second somatic hits in TP53 were also found in bladder and esophageal cancer types, at 67% (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). In addition, bladder cancers harbored MSH2 second somatic hits at 66.7% (2 of 3). Within cholangiocarcinoma cases, 33.3% (2 of 6) of patients with BRCA2 P/LP germline variants also had second somatic hits (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Within brain cancer cases, 42.9% (3 of 7) of patients with NF1 P/LP germline variants had a second somatic hit (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene Across All Tumor Types.

| Gene | Patients with any P/LP germline variant | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with any second somatic hita | Patients with any pathogenic somatic variant | Patients with any second somatic copy number loss | ||

| APC | 120 | 31 (25.8) | 28 (23.3) | 5 (4.2) |

| ATM | 275 | 31 (11.3) | 29 (10.5) | 2 (0.7) |

| BRCA1 | 328 | 9 (2.7) | 8 (2.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| BRCA2 | 388 | 41 (10.6) | 33 (8.5) | 8 (2.1) |

| CDKN2A | 26 | 5 (19.2) | 0 | 5 (19.2) |

| EGFR | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 8 (66.7) | 0 |

| MLH1 | 25 | 6 (24.0) | 6 (24.0) | 0 |

| MSH2 | 25 | 9 (36.0) | 9 (36.0) | 0 |

| MSH3 | 66 | 2 (3.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) |

| MSH6 | 42 | 13 (31.0) | 12 (28.6) | 1 (2.4) |

| MUTYH | 541 | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) |

| NBN | 75 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 |

| NF1 | 35 | 10 (28.6) | 10 (28.6) | 0 |

| NTHL1 | 48 | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (2.1) |

| PALB2 | 101 | 19 (18.8) | 18 (17.8) | 1 (1.0) |

| PMS2 | 53 | 9 (17.0) | 5 (9.4) | 4 (7.5) |

| PTEN | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| RET | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 0 | 3 (21.4) |

| TP53 | 63 | 18 (28.6) | 18 (28.6) | 0 |

Abbreviation: P/LP, pathogenic/likely pathogenic.

Second somatic hit indicates pathogenic somatic variant and/or somatic copy number loss.

MSH6 frequently contained second somatic hits in tumor types with germline testing guidelines, such as colorectal (5 of 7 [71.4%]) and endometrial (4 of 4 [100%]) cancers (eTable 8 and eTable 9 in the Supplement). In colorectal cancer, APC was the most prevalent gene, with a second somatic hit and/or CNL at 80.6% (25 of 31). A total of 6.5% (2 of 31) patients had CNL and 80.6% (25 of 31) patients had a pathogenic somatic variant. In addition, PALB2 was found to have a second somatic hit within breast (14 of 34 [41.2%]) and prostate (2 of 9 [2.2%]) cancer types (eTable 10 and eTable 11 in the Supplement). A total of 3.1% (1 of 32) of breast cancer cases with a PALB2 P/LP germline variant had PALB2 CNL. Pancreatic cancers were observed to have second somatic hits with high prevalences in the TP53 (3 of 5 [60.0%]), MSH2 (1 of 2 [50.0%]), MSH6 (1 of 4 [25.0%]), RET (1 of 3 [33.0%]) and ATM (12 of 53 [22.6%]) genes (eTable 12 in the Supplement).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study presents the largest retrospective analysis of deidentified real-world data from patients diagnosed with various cancer types who underwent T/N-matched genomic sequencing. Our analysis reveals the prevalence of P/LP germline variants in cancer types lacking hereditary cancer testing guidelines. Within the cohort, the highest prevalence of P/LP germline variants was found in bladder (79 of 1188 [6.6%]) and lung (448 of 7668 [5.8%]) cancers. Within tumor types with guidelines recommending hereditary cancer testing, the highest prevalences were found in breast (494 of 4581 [10.8%]) and ovarian (380 of 2756 [13.8%]) cancers. When we combine all cancer types in our study, the overall prevalence of P/LP germline variants was 7.3% (2534 of 34 642). For comparison, studies performed at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center found that 17.5% (182 of 1040) of their cohort harbored clinically actionable variants, yet 9.7% of these patients (n = 101) would not have their variants detected under current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline recommendations.17 Other studies have reported lower prevalences that vary from 3% to 12.6%.19,24,25,26,27,28,29 Our analysis included a 50-gene panel; however, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center study included a larger (76 genes) panel, which may explain the higher reported prevalence.

Our work supports the high prevalence of P/LP germline variants in certain cancer types, such as bladder, brain, lung, esophagus, cholangiocarcinoma, and head and neck tumor types observed in previous studies.12,17 Determining the percentage of patients with advanced cancer that would be missed by confining germline testing to a guidelines-based approach is complex and beyond the scope of the analysis presented herein. However, we can speculate, as Samadder et al12 noted, that universal multigene T/N panel testing can increase detection of P/LP germline variants over guideline-based testing. In addition, Lincoln et al18 found that a proportion of patients qualified for follow-up germline testing, with 8.1% of pathogenic germline variants being missed by tumor-only sequencing. The additional value of a T/N-matched panel includes the ability to detect both somatic and germline variants in the same gene,30 potentially revealing genomic drivers that clarify what biomarkers can be exploited as clinically targetable pathways. Using our large T/N real-world data set, we were able to examine the genes that were frequently associated with somatic second hits in the selected cancer types. For most cancer types, P/LP germline findings were enriched primarily by ATM, APC, and BRCA1/2 (excluding MUTYH). This finding has important therapeutic implications given the approval of the PARP inhibitor olaparib in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer with homologous recombination repair alterations31; in addition, recent clinical studies have shown promising antitumor activity of mutated ataxia telangiectasia and rad3-related inhibitors in patients with ATM and BRCA1/2 variant tumors.32,33 The top 3 genes with the highest number of second somatic hits were EGFR (8 of 12 [66.7%]), MSH2 (9 of 25 [36.0%]), and MSH6 (13 of 42 [31.0%]). A T/N-matched panel can provide comprehensive somatic and germline (limited to SNVs and small indels) findings that can identify potential targeted treatment options, as well as uncover P/LP germline variants that may be missed without a suspicious family history of cancer.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our T/N-matched LDT assay only reports SNVs and indels and does not detect large deletions and duplications. The Tempus xT incidental germline panel is not a validated germline panel, and therefore additional germline panel testing may be indicated for patients based on their personal and/or family histories. Our methods do not routinely collect information about Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, and we were therefore unable to determine whether the germline alterations identified contribute to the patient’s diagnosis.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest our approach may improve accurate categorization of variants and, through germline subtraction methods, provide a better understanding of the genetic factors that may be genomic drivers in a patient’s tumor.8 The identification of such findings may have clinical implications for the patient and their at-risk family members, resulting in the opportunity for genetic counseling and risk-stratified intervention, as well as potentially widening therapeutic options for patients with cancers that do not traditionally necessitate germline assessment.

eTable 1. Hereditary Cancer Genes Included in Analysis

eTable 2. Median Age at Diagnosis in Each Tumor Type

eTable 3. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Lung Cancer

eTable 4. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Bladder Cancer

eTable 5. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Esophageal Cancer

eTable 6. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Cholangiocarcinoma

eTable 7. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Brain Cancer

eTable 8. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Colorectal Cancer

eTable 9. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Endometrial Cancer

eTable 10. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Breast Cancer

eTable 11. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Prostate Cancer

eTable 12. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Pancreatic Cancer

References

- 1.Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobain EF, Wu Y-M, Vats P, et al. Assessment of clinical benefit of integrative genomic profiling in advanced solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):525-533. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao SJ, Sireci AN, Pendrick D, et al. Clinical utilization, utility, and reimbursement for expanded genomic panel testing in adult oncology. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4(4):1038-1048. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massard C, Michiels S, Ferté C, et al. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 Trial. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(6):586-595. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sicklick JK, Kato S, Okamura R, et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat Med. 2019;25(5):744-750. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0407-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsimberidou A-M, Iskander NG, Hong DS, et al. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: the MD Anderson Cancer Center initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6373-6383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radovich M, Kiel PJ, Nance SM, et al. Clinical benefit of a precision medicine based approach for guiding treatment of refractory cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56491-56500. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaubier N, Bontrager M, Huether R, et al. Integrated genomic profiling expands clinical options for patients with cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(11):1351-1360. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0259-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, et al. FDA approval summary: olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more lines of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4257-4261. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stadler ZK, Maio A, Chakravarty D, et al. Therapeutic implications of germline testing in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(24):2698-2709. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, et al. ; Olympia Clinical Trial Steering Committee and Investigators . Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutated breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394-2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naumann RW, Morris JC, Tait DL, et al. Patients with BRCA mutations have superior outcomes after intraperitoneal chemotherapy in optimally resected high grade ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151(3):477-480. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Treatment by cancer type. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

- 15.Gupta S, Provenzale D, Llor X, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(9):1032-1041. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=2&id=1503

- 17.Mandelker D, Zhang L, Kemel Y, et al. Mutation detection in patients with advanced cancer by universal sequencing of cancer-related genes in tumor and normal DNA vs guideline-based germline testing. JAMA. 2017;318(9):825-835. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln SE, Nussbaum RL, Kurian AW, et al. Yield and utility of germline testing following tumor sequencing in patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019452. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Daniels M, et al. Incidental germline variants in 1000 advanced cancers on a prospective somatic genomic profiling protocol. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):795-800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beaubier N, Tell R, Lau D, et al. Clinical validation of the Tempus xT next-generation targeted oncology sequencing assay. Oncotarget. 2019;10(24):2384-2396. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beaubier N, Tell R, Huether R, et al. Clinical validation of the Tempus xO assay. Oncotarget. 2018;9(40):25826-25832. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19(2):249-255. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.r-project.org/

- 24.Schrader KA, Cheng DT, Joseph V, et al. Germline variants in targeted tumor sequencing using matched normal DNA. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):104-111. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert BA, O’Daniel JM, Amin K, et al. Germline analysis from tumor-germline sequencing dyads to identify clinically actionable secondary findings. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(16):4087-4094. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones S, Anagnostou V, Lytle K, et al. Personalized genomic analyses for cancer mutation discovery and interpretation. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(283):283ra53. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons DW, Roy A, Yang Y, et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):616-624. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mody RJ, Wu Y-M, Lonigro RJ, et al. Integrative clinical sequencing in the management of refractory or relapsed cancer in youth. JAMA. 2015;314(9):913-925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(24):2336-2346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knudson AG Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68(4):820-823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1697-1708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yap TA, Tan DSP, Terbuch A, et al. First-in-human trial of the oral ataxia telangiectasia and RAD3-related (ATR) inhibitor BAY 1895344 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(1):80-91. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yap TA, O’Carrigan B, Penney MS, et al. Phase I trial of first-in-class ATR inhibitor M6620 (VX-970) as monotherapy or in combination with carboplatin in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(27):3195-3204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Hereditary Cancer Genes Included in Analysis

eTable 2. Median Age at Diagnosis in Each Tumor Type

eTable 3. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Lung Cancer

eTable 4. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Bladder Cancer

eTable 5. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Esophageal Cancer

eTable 6. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Cholangiocarcinoma

eTable 7. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Brain Cancer

eTable 8. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Colorectal Cancer

eTable 9. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Endometrial Cancer

eTable 10. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Breast Cancer

eTable 11. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Prostate Cancer

eTable 12. Second Somatic Hits in Germline Variants Within the Same Gene in Pancreatic Cancer