Abstract

Nurses, as front-line care providers, strive to offer adequate care to their clients. They have acquired valuable experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic that enhance the nursing profession. This study aimed to explore nurses' caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a qualitative meta-aggregative systematic review. Electronic databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, CINHAL) in English were searched to find out the meaningful subjective data on the COVID-19 pandemic. The inclusion criteria were studies published in English related to nurses' caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic. Seventeen qualitative studies with several approaches were included. Three key themes were identified from the studies: Weaknesses and strengths of nursing at the beginning of the pandemic, Nursing beyond challenges related to the pandemic, and Family and career challenges.

Nurses face different challenges in caring for patients with COVID-19 that benefit the health and nursing professions. Governments, policymakers, and managers have to support nurses during and after the pandemic. Without enough support, nurses are likely to experience significant psychological issues that can lead to burnout and frustration.

Keywords: Nursing care, Qualitative synthesis, Nurse, Experiences, COVID-19, Pandemics

1. Introduction

COVID-19 was first diagnosed in December 2019 in people with pneumonia in Wuhan, China [1]. COVID-19 began with a variety of symptoms, including respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, and symptoms ranged from mild to severe dyspnea, septic shock, and even defects in various organs of the body [2]. The disease was unknown, until March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the disease as the COVID-19 pandemic. As of May 15, 2022, more than 520 million people in the world have been infected with this disease, and the death toll has exceeded 6 million people [3]. WHO estimates that between 80 and 180 thousand, with a medium of 115.5 thousand, health care providers have died from COVID-19 in the period between January 2020 to May 2021[4].

COVID-19 pandemic has severely shocked the health care systems in most countries. Nurses, as the front line in the fight against CVID-19, are involved in issues such as screening, collaboration in treatment, and care of patients with this disease. Nurses have encountered a lack of knowledge, a load of work, no leisure time, and many psychological and familial burdens [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]].

Other issues, such as lack of personal protective equipment, artificial ventilators, oxygen generators, medicines, and vaccines overshadow the performance of nurses and other health professionals [10,11]. In pandemics, the health systems attempt to manage the issues and offer extensive services to people [12]. Despite nurses’ crucial role in public health in critical situations such as pandemics, they face certain obstacles to manage the events when there are no predefined specific guidelines or protocols [13,14]. Nevertheless, it is not clear enough to prepare the frontline nurses for unpredictable events such as pandemics of contagious diseases [15]. In the pandemic COVID-19, nurses have many experiences that could be fundamental for the nursing profession. Therefore, this literature review seeks to explore the nurses’ caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Research question

What are the nurses' caring experiences for patients in the COVID-19 pandemic?

2. Methodology

2.1. Design

In this qualitative meta-aggregative review, we polled, compared, and then summarized nurses caring experiences in COVID-19. The steps were conducted as follows: developing the research question as “What are the nurses' experiences in caring for patients in the COVID-19 pandemic?”, searching the literature for the evidence systematically, doing a critical appraisal of included studies, aggregating the findings, developing categories, and further synthesizing the themes [16].

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Qualitative studies were addressing nurses’ caring experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. No limits were placed on the year of publication. Only English publications were included. The article's title was on nurses' caring experience for patients with the COVID-19 pandemic. The nurses who participated in the reviewed studies were registered nurses at the front line of the COVID-19 pandemic, caring for COVID-19 patients for more than one month, and voluntarily participating in the studies.

2.3. Excluded criteria

Systematic reviews and quantitative as well as qualitative studies addressing the experiences of other health care professionals were excluded from the study.

2.4. Searching

In this systematic review, the eligible qualitative studies addressing nurses’ caring experiences in COVID-19 in English were selected only. It was decided to review the studies of nurses’ caring experiences published on reputable databases such as Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, and CINHAL. The article search was conducted from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 to the end of 2021. To maximize the search universality, the search was conducted for Latin and MeSH keywords including “coronavirus”, “qualitative research”, “nursing*”, “experience*”, “SARS-COV-2”, “COVID-19”, “caring”, and all possible combinations of words made by and/or operators in the introduced databases. The abstracts of studies were reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the full texts were evaluated. After the search was carried out, all resultant studies were reviewed in the screening and selection process. In the next step, studies were processed considering the aim of the research. Search strings used in PubMed:

(COVID-19) [MeSH Terms] AND nursing* [MeSH Terms] [All Fields]) OR (COVID-19) [MeSH Terms] AND qualitative research [subheading] [All Fields]) OR (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MeSH Terms] AND caring [Subheading] [All Fields]) OR (SARS-COV-2) [MeSH Terms] AND experience* [Subheadings] [All Fields]).

2.5. Quality assessment, data extraction, and synthesis

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist was employed to assess the quality of qualitative studies. This 10-item instrument checks the results, validity, and usefulness of qualitative studies (Table 1 ) [17].

Table 1.

Summary of studies and reported study results

| Author (year) Country | Purpose/Aim/Research Question | Methodology/Data collection/Data analysis | Sampling andparticipants | Main results/Themes | CASP scoring |

| Gao et al/ 2020/ China | To explore nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns while providing front-line care for COVID-19 patients in isolation wards | Phenomenological research method/ semi-structured interview/ Colaizzi's analysis method | Purposive sampling / 40 nurses | assess the competency of nurses to assignnursing work scientifically and reasonably, reorganize nursing workflow to optimizeshift patterns, communicate between managers and front-line nurses to humanizeshift patterns, and nurses’ various feelings and views on shift patterns | 9 |

| Wahyuningsih et al/ 2020/ Indonesia | to dig on the deep meaning on the nurses’ practice during treating the COVID-19’s patients | qualitative research/ semi-structured / content analysis | Purposive sampling / 5 nurses | the challenge of being a COVID-19 nurse in the emergency room, ICU and Covid care room, second, the resilience and resilience of nurses, third, the professionalism of nurses | 8 |

| Liu et al/ 2020 /China | describe the experiences of these health-care providers in the early stages of the outbreak | phenomenological qualitative study/ semi-structured interview/ Colaizzi's phenomenological method | purposive and snowball sampling / nine nurses and four physicians | “Being fully responsible for patients’ wellbeing— ‘this is my duty’”, “challenges of working on COVID-19 wards”, “resilience amid challenges”. | 9 |

| Catania et al/ 2020/ Italia | To explore nursing management issues within COVID-19 narratives of Italian front-line nurses | qualitative study/ semi-structured interview / thematic analysis | purposefully sampling/ 23 nurses | organizational and logistic change; leadershipmodels adopted to manage the emergency; changes in nursing approaches; personal protective equipment issues; physical and psychological impact on nurses; and team value/spirit | 9 |

| Karimi et al/ 2020/Iran | explore the lived experiences of nurses caring for patientswith COVID-19 in Iran | phenomenology qualitative study/ semi-structured interviews / Colaizzi's method | purposefully sampling/ 12 nurses | “Mental condition”, “emotional condition”, “care context” | 9 |

| Kackin et al /2020/Turkey | determine the experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey | phenomenology qualitative study/ semi-structured interviews / Colaizzi's method | purposive sampling/ 10 nurses | “Effects of the outbreak”,” short-term coping strategies” and “needs” | 9 |

| Galehdar et al/2020/Iran | explore nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19 | qualitative research/ semi-structured indepth telephone interviews/content analysis | purposive sampling/ 20 nurses | death anxiety, anxiety due to the nature of the disease, anxiety caused by corpse burial, fear of infecting the family, distress about time wasting, emotional distress of delivering bad news, fear of being contaminated, the emergence of obsessive thoughts, the bad feeling of wearing personal protective equipment, conflict between fear and conscience, and the public ignorance of preventive measures | 8 |

| Pazokia et al 2021/ Iran | investigate nurses who have experienced COVID-19 patient care. | qualitative study/ semi-structured interviews/content analysis | purposive sampling/ 18 nurses | Organizational Structure Challenges with five subcategories (high workload, deficiency in management, lack of facilities and equipment, irregularity and financial motivation) and care difficulty with four subcategories (psychological concern, recovery and treatment, insufficient care training programs and personal self-protection) | 8 |

| LoGiudice and Bartos/2021/US | To understand nurses’ lived experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak and to examine their resiliency | mixed methods design/ semi-structured interviews/ Colaizzi's phenomenological method was used for qualitative analysis/ | purposive sampling/ 43 nurses | “What's the protocol today? And were,oh where, is the research?”/Family ties broken: How nurses bridge the gap/The never-ending “sanitize cycle”/Restorative self-care/ “Proud to be a nurse” | 10 |

| Danielis et al/2021/Italia | To describe the experiences of Italian nurses who have been urgently and compulsorily allocated to a newly established COVID-19 sub-intensive care unit. | qualitative descriptive study/ focus groups /Thematic analysis | Purposive sampling/ 24 nurse | ‘Becoming a frontline nurse’, ‘living a double-faced professional experience’ and ‘advancing in nursing practice’ | 9 |

| Robinson and Stinson/ 2021/ US | this study was to understand the experiences of registerednurses working with hospitalized COVID-19 patients | hermeneutic phenomenology design/ Semi structured interviews/ Colaizzi's method | Purposive sampling/ 24 nurse | “The human connection,” “the nursing burden,” and “coping.” | 8 |

| Andersson et al/ 2021/ Sweden | the study was to deductively study person-centered care, based on critical carenurses’ experiences during the first phase of the covid-19 pandemic | qualitative design/ individual interviews/ content analysis | 6 Nurse | four domains of person-centered practice: the prerequisites, the care environment, person-centered processes and person-centered outcomes. | 8 |

| Specht et al/ 2021/ Denmark | To explore how nurses experienced working in a newly organized COVID-19ward with high-riskpatients during a new and unknown pandemic. | phenomenological-hermeneutic approach/ Semi-structured individual telephone interviews/ PaulRicoeur's theory | Purposive sampling/ 23 nurse | four themes were generated: (a) Challenging and uncertain situation, but also a positive experience (b) Professional and personal development (c) Lack of nurses' rights during a pandemic (d) Reward in itself or a desire for financial reward. | 9 |

| Bergman et al/ 2021/ Sweden | To describe Swedish registered nurses' experiences of caringfor patients with COVID-19 in ICUs during the pandemic | Mixed method/ Questionnaire and Facebook page/ content analysis and descriptive statistics | 474 nurses | three categories: tumbling into chaos, diminished nursing care, and transition into pandemic ICU care | 7 |

| Fernández-Castillo et al/ 2021/ Spain | to explore and describe the experiences and perceptions of nurses working in an ICU during the COVID-19 global pandemic | Qualitative research/ semi-structured videocall interviews/ / content analysis | homogeneous purposivesampling/17 nurses | 4 main themes: “providing nursingcare,” “resources management and safety,” “psychosocial aspects andemotional lability,” and “professional relationships and fellowship.” | 9 |

| Liang et al/ 2021/ Taiwan | to explore in-depth nurses’ experiences of providing care in the time of the COVID-19 global pandemic | qualitative study/ Semi-structured face-to-face interviews/ Colaizzi's seven-step method | purposivesampling/16 nurses | three themes: (i) facing the emerging challenge, (ii) struggling with uncertainty, fear, stigma,and workload, and (iii) adapting to changes in the environment: learning and innovation | 8 |

| White/ 2021/ US | to understand nurses’ caring experiences during the recent pandemic in theUnited States | interpretive phenomenological approach/ unstructured interview / Smith et al. (2009) approach to qualitative analysis | purposivesampling/15 participants | Five major themes were interpreted: If not us, then who?; Accepting uncertainty; It was never enough; Finding self and our voices in a new role; and Believing it was worth it | 8 |

Information was extracted and compared by two of the authors. Data were technically extracted and observational characteristics were included research question, sampling and recruitment, observed population, statistics collection, and data analysis. We used a thematic evaluation technique to synthesize the qualitative statistics [18]. Thematic qualitative statistics were coded from the studies' findings, including costs from contributors and observing the authors’ interpretations. The issues were inductively prepared under the headings for reporting. Data extraction, coding, and synthesis were achieved by two reviewers. MAXQDA was used for statistical control.

2.6. Risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias using criteria developed by Hawker and colleagues [19], which have been used in a range of reviews. Their critical appraisal tool allows for the methodological rigor of each empirical study to be assessed through assigning ratings (very poor, poor, fair, good) across nine categories: abstract and title, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, findings/results, transferability/generalizability, implications and usefulness [19]. The Hawker Tool was included in a full-text practice review by three authors. They discussed and resolved any disagreement about usage, performed the quality assessment on all included studies, and together clarified minor uncertainties at the end of the process.

3. Results

3.1. Specifications of papers

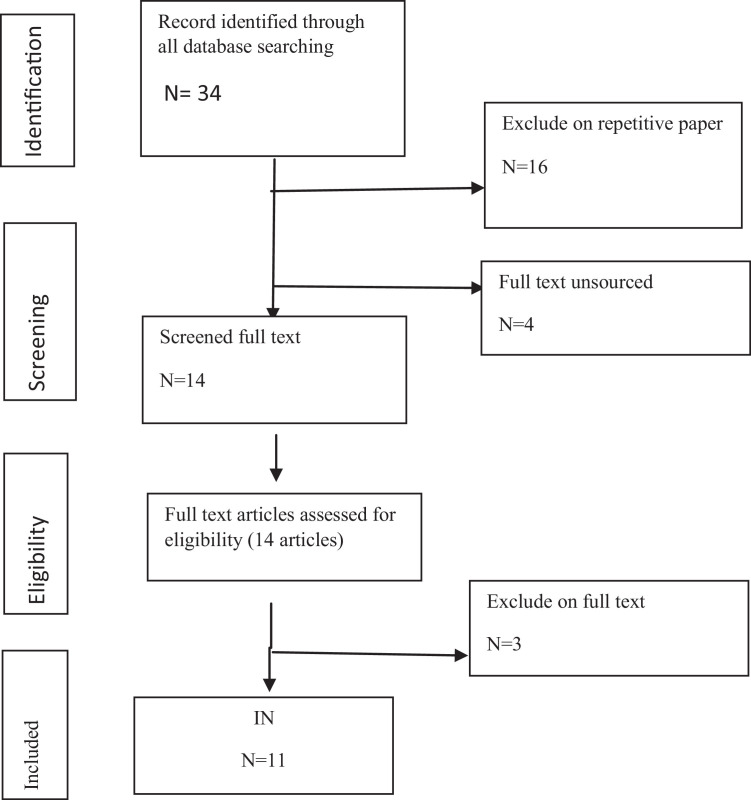

Of 156 extracted papers from databases, 10 were redundant. After two research team members conducted the initial review, 120 papers were deleted because their titles and/or abstracts did not meet the inclusion criteria. In the second screening step, 17 of 26 full-text publications met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 ).

Fig 1.

Flow of literature through the review

The demographic characteristics of participants such as age, gender, and the number of participants (353 participants in all papers) varied from 5 to 43 participants. All articles were qualitative, mixed-method, and phenomenological, which applied content or thematic approach. The purposive sampling technique was used in all studies. The publications' data were collected through semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using the content and thematic analyses, and Colaizzi's method (Table 1).

3.2. Results of data synthesis

Thirty findings were obtained from the eligible studies. All findings were checked in terms of validity or invalidity. Due to the similarities mentioned by citations in papers, 3 findings were categorized as 13 classes. Finally, three synthesized findings were obtained: Weaknesses and strengths of nursing at the beginning of the pandemic, nursing beyond challenges related to the pandemic, and Family and career challenges (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Synthesized findings

| Synthesized Findings | Categories | Gao et al. 2020 | Wahyuningsih et al. 2020 | Galehdar et al.2020 | Catania et al. 2020 | Pazokia et al. 2021 | Liu et al 2020 | Karimi et al. 2020 | Kackin et al 2020 | LoGiudice and Bartos. 2021 | Danielis et al. 2021 | Robinson and Stinson. 2021 |

| Weakness and strengths of nursing at the beginning of the epidemic | Unknown disease for nurses | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Anxious nurse and patient | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Surprise nurses at work | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Nursing team development | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Nursing as an influential profession | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Real care | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Nursing and beyond challenges related of epidemics | Shortage medical facilities and staff | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Excessive expectation of nursing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Nursing in treatment Frontline | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Family and career challenges | over pressure on Nursing | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Nurses' life threats | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Family Threats for Nurses | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Creating Career Problems for Nurses | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Care with angst | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

The studies were carried out in Asian countries with approximately the same history in socioeconomic, cultural, and health. Asia is the biggest continent with half of the world's population resides. The incidence of COVID-19 was very high in some less developed countries, leading to many deaths.

Weaknesses and strengths of nursing at the beginning of the pandemic included the following subcategories: An unknown disease for nurses [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]], anxious nurse and patient [20–24,28,29], surprised nurses at work [20–27,[30], [31], [32], [33]], nursing team development [21,22,27,29,34,35], nursing as an influential profession [20,25,30–35] and real care [20–22,29–31,35].

The subcategories for nursing beyond challenge's theme included the shortages of medical services and staffing [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25],28,31–33], an excessive expectation of nursing [24,26,27,28,31], and nursing treatment frontline [20–24,27,28,31,35].

The subcategories of family and career challenges were Overpressure on nursing [20–25,28–31,35], Nurses’ life threats [20–24,28,30,34,35], family threats for nurses [20–24,34], Creating career problems for nurses [21–26,34], and care with the angst [20–22,29,33–35].

4. Discussion

This systematic review of qualitative studies explores nurses’ caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic. There are three synthesized findings on nurses’ caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic as follow: Weaknesses and strengths of nursing at the beginning of the pandemic, nursing beyond the challenges of the pandemic, and family and career challenges.

During the pandemic, nurses experience many issues such as changes in the workplace for offering care to the clients, therefore, nursing weaknesses and strengths emerge, and their medical care attempts for patients are affected by governmental policies. In other words, the importance of nursing care is highlighted during the pandemic.

Nursing weaknesses and strengths emerge during the pandemic outbreak and nurses' intervention until the stabilization of work conditions. Nurses have experienced a knowledge deficit, a lack of preparedness to manage the pandemic, and shortages of staff, facilities, and equipment. Besides, people admire nursing services during the pandemic and realize the nursing profession is valuable to humanity. Moreover, positive aspects of nurses’ work such as teamwork, compassion, and sacrificing themselves to save patients' lives are prominent in health systems. Considering the findings of a study consistent with the results of this study, nurses' lack of knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic, shortages of personal protective equipment, and lack of managing protocols directly affect nurses’ roles and result in problems in providing proper care [36]. Nurses mainly face challenges such as the risk of infection transmission, shortage of resources, workplace change, lack of knowledge, doubt, and fear which leads to low performance and quality of care services [37]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses’ responsibilities changed due to the increasing number of patients need intensive medical care. The shortage of nurses has prolonged working shifts and has increased nurses’ duties [38]. In normal conditions, nurses experience workload and in a deadly pandemic, they are likely to face even more uncertain conditions is higher and the nursing profession is more highlighted than before [39].

Nursing beyond challenges related to the pandemic includes the following subcategories: The shortage of medical facilities and staffing, excessive expectation of nursing, and nursing in the treatment frontline. The COVID-19 pandemic places nurses on the treatment frontline and increases their managers' expectations. The managers and caregivers expect standard care from nurses despite shortages of safety equipment. Therefore, nurses have to stay a long time in the hospital to cover personnel shortages and save the existing protective equipment to compensate for further shortages. Protecting and maintaining the health of staff during the COVID-19 pandemic is crucial for health care institutions, particularly in Intensive Care Units, where high-qualified nurses and staff cannot effectively supplant [40].

Given suitable conditions for nurses to work in the pandemic, one of the critical assignments of health policymakers is to control the infection chain. The staff's contamination and death seriously influence nurses' workload and the health care system [41]. Health care systems cannot fulfill the clients' needs unless enough facilities and staff are available [42]. Besides, during the pandemic, nurses experience workload, fear, high pressure, anxiety, helplessness [43], sleep disorders, depression [44], and many potential or actual problems [45]. The pandemic causes dangerous work environments for the medical staff, puts too much pressure on nurses, and threatens them. Nurses are a potential source of infection. Considering the high pressure, nurses experience psychological problems. The shortage of staff prolongs their working hours. As a result, they experience physical complications and occupational burnout. They also feel fearful and anxious when they take care of patients because of the risks of the disease. Nurses have experienced posttraumatic stress disorder [46,47], emotional fatigue, burnout, muscle aches, and mental problems after COVID-19 [48].

4.2. Strengths and limitations

There were a few limitations in the interpretation of the current systematic review findings. First, probably, the main experiences or results might interpret incorrectly when qualitative data are synthesized from different sources. To minimize this possible error, a regular method was followed. Second, it is probable that the search strategy cannot identify all of the relevant papers because more results might be extracted by selecting other keywords. In addition, searching a larger number of more specialized databases can help find more relevant papers. Searching in other languages rather than English can also result in finding new papers.

The strength of this study is the specialty of the research team in qualitative studies. The extracted themes resulted from their intellectual integration, presumably including different areas of nursing, patients, and healthcare systems. The reviewed research results were aggregated into these areas.

Considering the COVID-19 pandemic conditions, the results of this systematic review can help increase our knowledge and provide authorities with information on nurses’ experiences in other pandemics to benefit from the results in the current conditions.

This study also shows appreciation to the nurses who are always serving those who need help on the frontline of crises, wars, and pandemics through sacrifice and bravery.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review of qualitative studies was conducted in different countries by providing an aggregated outlook of nurses' caring experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic. This study helps nurses provide better healthcare services and comply with safety instructions.

There are similarities and differences in nurses’ caring experiences during the pandemic in countries. Nurses face many challenges and advantages in providing nursing services during the pandemic. At the same time, they try to take care of patients better by following healthcare protocols in addition to complying with safety and protection instructions.

This review extends the perception of nurses' experiences and can lay the foundations for expanding knowledge and developing the nursing profession by determining more research areas in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Governments, policymakers, and nursing managers are called upon to take an active part in supporting nurses, both during and after the pandemic. Without this, nurses are likely to experience significant psychological issues that can lead to burnout and loss of the nursing workforce.

Funding source

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors dedicate this manuscript to all of the health care workers who have died while fighting COVID-19.

References

- 1.H. Tandon, P. Ranjan, T. Chakraborty, V. Suhag, Coronavirus (COVID-19): ARIMA based time-series analysis to forecast near future, arXiv. Preprint. arXiv. 2004 (2020) 07859.

- 2.Adhikari S.P., Meng S., Wu Y.J., Mao Y.P., Ye R.X., Wang Q.Z., et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic [Internet]. American Library Association. (2022) Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 4.World Health Organization. (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on health and care workers: a closer look at deaths. World Health Organization. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345300

- 5.Mascha E.J., Schober P., Schefold J.C., Stueber F., Luedi M.M. Staffing with disease-based epidemiologic indices may reduce shortage of intensive care unit staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth. Analg. 2020;131:24. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Carmen Giménez-Espert M., Prado-Gascó V., Soto-Rubio A. Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.566896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nogee D., Tomassoni A.J. Covid-19 and the N95 respirator shortage: closing the gap. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020;41:958. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrestha G.S. COVID-19 pandemic: shortage of personal protective equipment, use of improvised surrogates, and the safety of health care workers. J. Nepal Health Res. Council. 2020;18 doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i1.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi M., Abdollahimohammad A., Firouzkouhi M., Shivanpour M. Challenges of prehospital emergency staff in the COVID-19 pandemic: a phenomenological research. J. Emerg. Pract. Trauma. 2021;8:1–5. doi: 10.34172/jept.2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hetzmann M.S., Mojtahedzadeh N., Nienhaus A., Harth V., Mache S. Occupational health and safety measures in German outpatient care services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:2987. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firouzkouhi M., Kako M., Alimohammadi N., Arbabi-Sarjou A., Nouraei T., Abdollahimohammad A. Lived experiences of COVID-19 patients with pulmonary involvement: a hermeneutic phenomenology. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022;31:747–757. doi: 10.1177/10547738221078898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy B.P., Molinari N.A.M., LeBlanc T.T., Vagi S.J., Avchen R.N. Progress in public health emergency preparedness—United States, 2001–2016. Am. J. Public Health. 2017;107(S2):S180–S185. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304038. 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zottele C., Magnago T.S., Dullius A.I., Kolankiewicz A.C., Ongaro J.D. Hand hygiene compliance of healthcare professionals in an emergency department. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP. 2017:e03242. doi: 10.1590/s1980-220x2016027303242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdollahimohammad A., Firouzkouhi M. Future perspectives of nurses with COVID 19. J. Patient Exp. 2020;7:640–641. doi: 10.1177/2374373520952626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baack S., Alfred D. Nurses’ preparedness and perceived competence in managing disasters. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2013;45:281–287. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannes K., Pearson A. Wiley Blackwell; 2012. Obstacles to the Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice in Belgium: A Worked Example of Meta-Aggregation Synthesizing Qualitative Research; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munn Z., Moola S., Riitano D., Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawker S., Payne S., Kerr C., Hardey M., Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002;12:1284–1299. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q., Luo D., Haase J.E., Guo Q., Wang X.Q., Liu S., et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e790–e798. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimi Z., Fereidouni Z., Behnammoghadam M., Alimohammadi N., Mousavizadeh A., Salehi T., et al. The lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Iran: a phenomenological study. Risk. Manag. Healthc. Policy. 2020;13:1271–1278. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S258785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kackin O., Ciydem E., Aci O.S., Kutlu F.Y. Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: a qualitative study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2021;67:158–167. doi: 10.1177/0020764020942788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galehdar N., Kamran A., Toulabi T., Heydari H. Exploring nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMC psychiatry. 2021;20:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02898-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pazokian M., Mehralian Q., Khalandi F. Experiences of nurses caring of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Evid. Based Care. 2021;10:17–24. doi: 10.22038/ebcj.2021.54131.2423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Specht K., Primdahl J., Jensen H.I., Elkjaer M., Hoffmann E., Boye L.K., et al. Frontline nurses’ experiences of working in a COVID-19 ward-a qualitative study. Nurs. Open. 2021;8:3006–3015. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang H.F., Wu Y.C., Wu C.Y. Nurses’ experiences of providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan: a qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021;30:1684–1692. doi: 10.1111/inm.12921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White J.H. It was never enough": the meaning of nurses’ experiences caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Issues Ment. Health. Nurs. 2021;42:1084–1094. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2021.1931586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao X., Jiang L., Hu Y., Li L., Hou L. Nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns in isolation wards during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29:4270–4280. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernández-Castillo R.J., González-Caro M.D., Fernández-García E., Porcel-Gálvez A.M., Garnacho-Montero J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2021;26:397–406. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahyuningsih I.S., Janitra F.E., Hapsari R., Sarinti S., Mahfud M., Wibisono F. The Nurses’ experience during the caring of coronavirus (COVID-19) patients: a descriptive qualitative study. J. Keperawatan Padjadjaran. 2020;8:262–270. doi: 10.24198/jkp.v8i3.1559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson R., Stinson C.K. The lived experiences of nurses working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;40:156–163. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson M., Nordin A., Engström Å. Critical care nurses’ experiences of working during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic - applying the person-centred practice framework. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022;69 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamanzadeh V., Valizadeh L., Khajehgoodari M., Bagheriyeh F. Nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:198. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00722-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LoGiudice J.A., Bartos S. Experiences of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study AACN. Adv. Crit. Care. 2021;32:14–26. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2021816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danielis M., Peressoni L., Piani T., Colaetta T., Mesaglio M., Mattiussi E., et al. Nurses’ experiences of being recruited and transferred to a new sub-intensive care unit devoted to COVID-19 patients. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021;29:1149–1158. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lockett J.C.M., Nelson K., Hales C. Pre COVID-19 emergency department nurses’ perspectives of the preparedness to safely manage influenza pandemics: a descriptive exploratory qualitative study. Australas. Emerg. Care. 2021;24:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrowsmith V., Lauf Walker M., Norman I., Maben J. Nurses' perceptions and experiences of work role transitions: a mixed methods systematic review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016;72:1735–1750. doi: 10.1111/jan.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Q., Li T., Su Y., Luan Y. Instructive messages and lessons from chinese countermarching nurses of caring for COVID-19 patients: a qualitative study. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2021;32:96–102. doi: 10.1177/1043659620950447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.González-Gil M.T., González-Blázquez C., Parro-Moreno A.I., Pedraz-Marcos A., Palmar-Santos A., Otero-García L., et al. Nurses’ perceptions and demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;62 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mascha E.J., Schober P., Schefold J.C., Stueber F., Luedi M.M. Staffing with disease-based epidemiologic indices may reduce shortage of intensive care unit staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth. Analg. 2020;131:24–30. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu H., Intrator O., Bowblis J.R. Shortages of staff in nursing homes during COVID-19 pandemic: what are the driving factors? J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020;21:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liberati E., Richards N., Willars J., Scott D., Boydell N., Parker J., et al. A qualitative study of experiences of NHS mental healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:1–2. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagesh S., Chakraborty S. Saving the frontline health workforce amidst the COVID-19 crisis: challenges and recommendations. J. Glob. Health. 2020;10 doi: 10.7189/jogh-10-010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tu Z.H., He J.W., Zhou N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. J. Med. 2020;99:1–5. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X., Jiang Z., Yuan X., Wang Y., Huang D., Hu R., et al. Nurses reports of actual work hours and preferred work hours per shift among frontline nurses during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic: a cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moon DJ, Han MA, Park J, Ryu SY. Post-traumatic stress and related factors among hospital nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Psychiatr. Q. 2021 Dec;92(4):1381–1391. doi: 10.1007/s11126-021-09915-w. Epub 2021 Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.d'Ettorre G., Ceccarelli G., Santinelli L., Vassalini P., Innocenti G.P., Alessandri F., et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:601. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rathnayake S., Dasanayake D., Maithreepala S.D., Ekanayake R., Basnayake P.L. Nurses’ perspectives of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a phenomenological study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]